#frev writing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Light in the Storm, Part 3

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 |

(Based on a prompt by @givethispromptatry , although I had to find a synonym to the word “stuck” to avoid potential anachronisms.

Dedicated to the French Revolution community and the Napoleonic community on Tumblr. Special thanks to @amypihcs @josefavomjaaga and @maggiec70 for helping me out with improving this chapter through their suggestions and constructive feedback.

I’m very sorry for such a long chapter and for the long wait.)

Tw: Non-graphic descriptions of injuries, mentions of death, mentions of blood and gore, war.

June 15, 1800

Caroline found herself standing in the shade of an oak tree, almost identical to the one that had become her grandmother’s resting place. Surrounding said tree were the vast and serene wheat fields of Marengo. A breeze caressed the dark leaves of the oak, which produced a quiet and calming rustle.

Caroline’s heart was no longer aching, which could only mean one thing: all of this was but a dream. In reality, her pain would have never vanished this quickly. Not after healing such a severe injury.

“Caro, my dear, turn around.” A familiar voice called her name.

Caroline obeyed, gasping when she saw the source of the voice.

Standing in front of her was her grandmother, wearing a simple white dress and holding a tiny bouquet of forget-me-nots, their blue colour matching her and Caroline’s eyes. The older woman’s head was adorned with a wreath of bluebells.

Lucie MacBride was smiling in the same sincere and warm manner as she used to do when she was alive. There was no trace of weakness nor illness in her physique any longer, as earthly ills could not affect the dead.

Her posture was straight, her voice clear, her gaze gleaming with youthful energy without losing the indescribable aura of wisdom that she had had in life.

“GRANDMOTHER!” Caroline sprinted towards Lucie MacBride and gave her a tight embrace.

Her grandmother returned the gesture, patting Caroline on the back and wiping the tears off of her freckled rosy cheeks.

“Hush, my Caro. I missed you too, but know that I am always by your side. In fact, I am visiting you because I have important things to tell you. Things that can’t wait.”

“What is it?” Caroline immediately looked up at her grandmother.

“I’m proud of you. Proud of the choice you made today and how you stayed true to your morals despite how hard it was.” Lucie MacBride caressed her granddaughter’s head. “You saved the life of your patient and stayed with him up until help arrived in spite of your fear. You acted the way a true doctor should and it was not in vain.”

A hopeful glimmer appeared in the girl’s eyes.

“So General Desaix is–?”

Lucie MacBride nodded.

“Alive, in no small part due to your and Lebrun’s aid. However, he is not out of the woods yet. He needs care and time to make a full recovery. Fortunately, he is young and healthy so the worst part of the ordeal has already passed.”

Caroline sighed in relief and her smile widened almost from ear to ear. Dimples appeared on her cheeks and she felt as if someone had lifted a lot of weight off of her chest.

“I’m glad to know that both our family and my patient survived this Hell, Grandmother.”

The older woman nodded with a smile. However, a mere seconds later her expression became very serious.

“I am glad as well. Not only is everyone in our family safe, but you also did the right thing and saved a life even though you were afraid. You saved Desaix when you could have chosen to leave him behind. I knew some people who would have abandoned him were they in your position, especially if nobody would ever know.”

Caroline’s smile faded and she frowned, as if the fact that only saving herself had been an option the entire time came as a surprise to her.

As hard as it was to admit it, she knew that some people would indeed flee and some would even loot Desaix’s corpse after the battle. The MacBride family had met such scoundrels on the way to Marengo all those years ago.

But Caroline was no scoundrel.

“I would know.” She replied with no hesitation. “I would know of my choice, Grandmother. You know I could not have acted differently.

Lucie MacBride smiled again, her expression filled with pride.

“I knew you would make the right choice, Caro, but your trials and tribulations are far from over. There is more to come. Please, try to prepare yourself, for they shall not be easy.”

Caroline nodded, remembering the last part of her premonition.

Although she still wasn’t quite sure what would cause her to leave, seeing as Marengo wasn’t a war zone any longer, she was slowly accepting the fact that things were changing and that perhaps she would truly have to leave.

“I understand and I shall do my best to prepare, Grandmother. Is there anything else you would like to tell me?”

The girl’s grandmother nodded.

“Remember, my dear: he knows.” She tightened her caring embrace.

“He knows?” Caroline echoed, looking at her grandmother in search for more information. “Who are you talking about? The general?”

“That you shall see.” her grandmother suddenly let go of the girl. “But now you must go, for there are urgent matters to attend to in the world of the living. I shall continue to watch over the family and I hope we can meet in your dreams again. Remember, I shall always be there for you, even in death.”

Caroline could only nod.

There was no point in trying to linger in the world of dreams, for reality was waiting and there would be urgent matters indeed - the young healer knew that her ordeal was far from over.

The girl managed to embrace her grandmother one more time before everything around her faded away and her dream ended just as abruptly as it had begun.

***

Caroline woke up to Adèle shaking her. It was far less gentle than usual and her oldest sister wasn’t humming any songs under her breath like she normally would.

“Caro, wake up! Wake up!”

“What happened?” The girl yawned and opened her eyes. “What is the matter? You look pale. Something is wrong with our animals?”

“Worse! There are two soldiers downstairs and they say they’re here to bring you to the First Consul and I don’t know why! They want to see you immediately!”

The girl jolted awake upon hearing those words, realising that things were indeed urgent and even more so than she had hoped.

“General Desaix…” Caroline muttered, knowing that it was the likeliest reason for the unexpected visit. “Please, Adèle, help me get ready. I don’t think I’m fully recovered yet…”

Adèle nodded and began helping her youngest sister with the task, all while humming old Irish lullabies under her breath - a self-soothing tactic she would often use, Caroline knew that she was bound to be questioned about the identity of that “General Desaix” she mentioned, but now was not the time for questioning.

After Caroline was finally dressed up properly, her oldest sister led her downstairs, all while still humming tunes in an attempt to stay calm. Meanwhile, the young healer, who had to lean on Adèle for support, knew that her entire family must have been worried sick and incredibly confused as to why soldiers would know their youngest and need to bring her to the First Consul.

Of course, when the girl came downstairs, she saw just how scared and confused her family was. Their faces were pale, almost ghostly white in the dim light of a candle her mother was holding. Their eyes were wide and their gaze kept rapidly switching from Caroline and Adèle to the open front door.

Standing right outside were two soldiers. Much to Caroline’s relief, one of them turned out to be Maurice, the soldier who had helped her get back home. The other soldier, an older and fatter man with a thick moustache and an eyepatch on his right eye, was a stranger the girl had never seen before.

While it made perfect sense for Napoleon Bonaparte to send two soldiers instead of one from a standpoint of safety, the older soldier’s grumpy expression and hawklike gaze made Caroline gulp, for he resembled a brigand from a fairy story.

The older soldier stepped forward, looked at young healer and inquired in a raspy voice:

“Are you Caroline MacBride, Citoyenne?”

Caroline could only nod and gulp again as a painful knot appeared in her stomach, making her feel queasy.

“Good. I am Lieutenant Rémi Brasseur. This is Second Lieutenant Maurice Calvez, but you already know him. The First Consul is waiting. Please follow us.”

Before the girl could do so, her mother, Nicole MacBride, looked directly at the senior soldier, her fear having seemingly evaporated from her short, muscular form.

“May I come too?” More a demand than a question. “Our girl is far too young to be in the midst of those grimy soldiers all by herself!”

The colour drained from Maurice’s rosy cheeks, but he did not lose composure. His superior’s stern expression remained unchanged.

“I’m sorry, Citoyenne, but the First Consul gave us explicit orders to only bring Caroline.”

“Worry not, your daughter will be under our protection at all times.” Maurice added, trying not to stutter.

Nicole sighed.

“And nothing can be done about it?”

“I’m afraid no, Citoyenne. However, you have my word that your daughter will be safe under our supervision.”

“Very well.” The woman sighed. “But you better keep your word unless you wish to face a mother’s wrath.”

Sensing the threat in his wife’s voice, Gilbert MacBride approached her from behind, firmly putting his hand on her shoulder.

“Nicole, please calm down.” He sighed before looking at the soldiers. “I beg you to keep our youngest safe, Citizens. That will be in… everyone’s best interest.”

The older soldier frowned, but a barely visible twinkle appeared in his good eye, as if the threats had amused him.

“Father, Mother, please do not anger them.” Caroline sighed. “If speaking to me is the Consul’s wish, then I have no choice but to go. I would rather not test his patience.”

With that, she let go of Adèle’s elbow and stumbled towards the men, still somewhat dizzy and weakened. Noticing this, Maurice graciously offered her to lean on him, but the girl refused. She bit her lip, glanced at her terrified family and then turned back to face the men.

“I think I can walk without assistance now, but thank you. Please lead the way.”

***

The First Consul of France, General Napoleon Bonaparte, was pacing back and forth inside his tent, ignoring the drunken noises of celebration outside.

In a few hours, he would have to meet with the defeated Austrian officers in the nearby city of Alessandria to sign an official armistice. In all likelihood, the upcoming peace treaty would be signed on France’s terms.

They were the winners of that grueling godforsaken campaign. The battle of Marengo had been the decisive factor behind that victory. And to think that he would have lost if not for Desaix’s decision to rejoin him and order a counter attack while the Austrians were prematurely savouring their initial success!

“Desaix…” Napoleon muttered as new tears swelled in his red and puffy eyes.

General Louis Desaix had been shot in the chest and was now resting in the field hospital after his injuries got tended to by surgeons. According to them, Desaix’s survival was nothing short of magic, as the entry and the exit wound were right on the general’s heart. Said heart was still beating, however, even though the musket ball should have shattered it into smithereens, guaranteeing an instant death. And yet Desaix was somehow still alive, although one of the surgeons, Doctor Modeste Pujol, warned the First Consul that the patient was not completely out of danger just yet.

In fact, Desaix had only regained consciousness for a few minutes while the consul was by his bedside. But in those few minutes, he managed to request one single thing: “Find that girl”.

Napoleon stopped in his tracks and glanced at his pocket watch, impatiently tapping his foot. What was taking those soldiers so long to find one civilian girl when one of them already knew her name and the location of her family’s farm?!

Luckily, he would not have to wait for much longer. Soon, the soldiers sent to fetch the girl returned with her in tow.

To say that Napoleon was surprised was an understatement. Said girl was nothing like the old or seductive witches he had heard about as a child.

Standing in front of him was a short muscular peasant girl with long braided copper red hair, bright blue eyes and tan skin common for people of her status. Her rough hands were covered in calluses but were just a bit softer than Napoleon had expected.

The girl was standing as straight as possible but was so far silent, waiting for the First Consul to speak first. Drops of cold sweat on her forehead were clearly visible in the flickering lantern light and her entire body was trembling. She felt somewhat nauseated due to fear.

Napoleon examined the girl with his eyes, looking at her from head to toe, like a stern teacher would look at a misbehaving pupil. It was in this tense atmosphere that the questions began.

“Your name.” he demanded in French, speaking with an Italian accent that he never completely got rid of.

“Carolina Liberté MacBride, Citizen First Consul.” She responded in Italian, sensing that perhaps the man would find it somewhat easier to communicate in his native tongue.

Napoleon stopped in his tracks, but his expression betrayed no emotion aside from his eyes still being somewhat red and puffy.

“Your age, Citoyenne MacBride.” This time the demand was made in Italian.

“Sixteen, though I shall be seventeen in July–Pardon, Messidor.” She corrected herself, remembering that France probably still used the new calendar that had been introduced during the Revolution.

“How long have you been living in Marengo? Is your family Scottish?”

“Irish, Citizen First Consul. We… left France when I was ten years old.” The girl was positively shaking now, praying that the man would not pry about the reason for her family’s flight.

The First Consul nodded and began to pace back and forth, now seemingly lost in his own thoughts and forgetting that the girl was still standing there.

As for Caroline herself, her gaze was following the intriguing man who was now pacing in front of her and she dared not remind him of her existence first, for angering such a man was the last thing she wanted to achieve.

Finally, Napoleon stopped pacing, looked the girl right in the eyes again and continued to pile more and more questions onto her. The questions were still rather generic at first, such as asking who Caroline was by trade and whether she was literate or not.

However, the First Consul eventually began to ask the young healer far more personal questions.

“You say your family left France… six years ago? Is that correct?” His eyebrows lowered in a frown.

Caroline nodded, trying to control her shaking body and rapid breathing. Her nausea was growing stronger, yet she was trying her best not to vomit.

“And why did you flee? Most émigrés had done so in the prior several years. Why wait until after that faithful Thermidor?

The girl felt a pit form in her stomach and her nausea grew even worse. She knew she had to respond in a way that would not expose her family and still be truthful.

“We kept hoping we would be able to remain.” She sighed. “It is not easy to uproot one’s entire life and move to a different country all of a sudden. But after everything that happened… things got much more chaotic than they had been up to that point. We simply had to escape a new wave of terror and violence.”

The First Consul responded with a nod, as if satisfied with the response, at least for the time being.

“Very well, Citoyenne MacBride. Now, tell me what you were doing on the field of battle. A civilian, especially a young woman, should not go anywhere near such a place.”

Caroline sighed and explained everything as best as she could. She did not omit her status as a local folk healer either, deciding that it was better for her to tell Napoleon Bonaparte who she was than for the locals to feed him lies about her abilities.

The First Consul, who was once again pacing back and forth, did not appear to be listening to the girl’s explanation at first, until she mentioned her peculiar line of work.

“A folk healer, Citoyenne?” He raised his thin eyebrows. “An herbalist?”

“No, Citizen First Consul. Not an herbalist. I heal with my hands by placing them on the body of the patient. My… late grandmother…” Caroline’s voice trembled before she managed to collect herself.

“She had that ability too?” Now the First Consul seemed completely shocked, his eyes as wide as plates.

“Indeed. In Ireland, they say that a twice seventh son or a twice seventh daughter is born with abilities to heal any illness and to foretell the future.”

Napoleon Bonaparte listened attentively, his mouth slowly curling into a small grin, as if he was planning to do something with that new information.

“Well,” he cleared his throat. “Your story of seventh offspring and magic sounds… intriguing. However, I am long past the age of believing in old wives’ tales. Prove it!”

Caroline felt as if she was definitely going to vomit very soon. Just what would happen if she was to be exposed to the French army as a witch?

“P-prove m-my magic?” she stuttered, her fists clenched and her face completely drained of colour save for a greenish tinge typical of nausea.

“Yes, Citoyenne. I need proof that what you just told me is true.”

Caroline exhaled, trying to steady her breath and calm her nausea. It would not do her any good to vomit or faint in front of the First Consul. It was only natural for him to want proof, and at least he was not reaching for holy objects or hurling profanities at her under his breath.

Besides, as a healer, Caroline could never refuse a patient.

“Very well, Citizen First Consul. I shall do my best.”

“Very good. Guards!” Napoleon called out, peeking out of the tent. “Summon General Berthier this instant!”

***

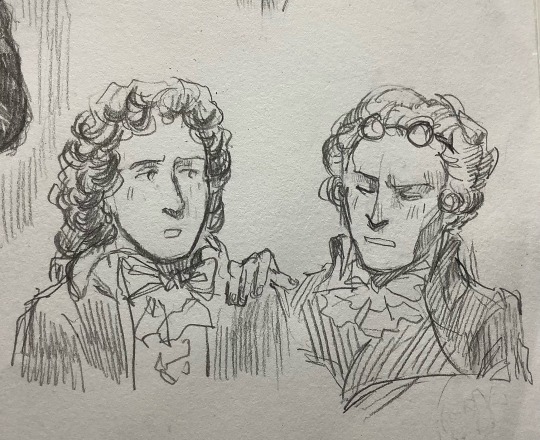

General Louis Alexandre Berthier turned out to be a jovial and plump man in his mid forties, whose wide kind face was already showing laugh lines and wrinkles. The ink staining his hands was a clear indication that he had been busy working on some correspondence prior to being summoned by his commander.

General Berthier’s stiff posture, too stiff even for the army, betrayed a noble upbringing, perhaps at the royal court in Versailles.

Caroline quickly made a clumsy attempt to curtsy, not being sure how else to greet such a man. She then noticed that one of General Berthier’s arms was bandaged and a stain of blood had formed on the fabric. The wound was clearly fresh.

“Berthier,” Napoleon Bonaparte spoke to his subordinate. “This young citoyenne claims to be a witch. I want proof that her abilities are true. Will you let her try and… heal your arm?”

Caroline winced ever so slightly at the term the First Consul had just used to describe her. After all, witches were usually evil worshippers of the Devil who would cause harm to people and animals, while Caroline and her late grandmother were devout Christians who had dedicated their lives to helping others.

However, the girl dared not correct Napoleon. That would not have been prudent in her circumstances.

Instead, she carefully placed her hands on General Berthier’s arm with the latter’s permission.

“You may feel a tingling sensation and perhaps some heat, Citizen General Berthier.” The young healer warned. “But this is common and a good sign.”

Berthier nodded, smiling at the girl in a kind yet skeptical manner. Suddenly, he felt a strange sensation of pins and needles in the wounded area, then strange warmth and a bit of a tickle.

Caroline, for her part, hissed in visible pain and bit her lower lip, as if trying to suppress a scream.

Soon, the pain in Berthier’s arm vanished completely, while the girl let out an anguished yelp and gripped one of her arms, searing pain radiating from that arm and throughout her entire body. She stumbled backward, her face somehow even paler than before.

“CITOYENNE!” General Berthier and Napoleon called out, catching Caroline and helping her sit down on a chair.

“I-I am alright…” Caroline made a weak attempt to reassure the men. “I just… In exchange for healing, I… take on the pain…” she hissed, tightening her grip on her hurting arm.

The First Consul and Berthier quickly exchanged shocked looks before the former ordered one of the guards to bring some wine while the latter stayed with the girl, trying to keep her conscious.

***

After a sip of wine, Caroline’s face did regain some healthy colour at last, and Napoleon, wisely deciding to end the interrogation and the tests that instant.

He summoned Brasseur and Maurice with an order to make sure that Citoyenne Caroline Liberté MacBride is returned safe and sound to her family.

Just as Brasseur, who was carrying the completely exhausted girl in his rough arms, and his subordinate left the camp, Napoleon dismissed Berthier and sat down at his desk, his eyebrows furrowed in thought.

While he still could hardly believe it, the proof was undeniable. Magic was real. His thoughts immediately switched to his beloved wife, Josephine, and to their struggles with conceiving a child to continue Napoleon’s legacy.

They had already tried many methods to remedy the issue, and yet none had succeeded this far. And while only one healer could hardly be of use to his giant army, perhaps, just perhaps, that young girl was his and his wife’s last hope.

Although the chances were slim, Napoleon knew that he had to take that risk. And, with Piedmont now guaranteed to be his territory, inviting Caroline MacBride to Paris would not be much of an issue.

Satisfied with this plan, the First Consul rose from his desk and left his tent to visit General Louis Desaix at the hospital.

“I’m proud of you. I’m proud of the choice you made today and how you stuck to your morals despite how hard it was.“

#french revolutionary wars#french revolution#frev#history#frev art#a light in the storm#frev writing#frev wip#battle of marengo#marengo#louis charles antoine desaix#napoleon bonaparte#historical fiction#short story#writing#my writing#sentence prompt#story prompt#not my prompt#louis alexandre berthier#josephine bonaparte

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anxiety and paranoia following an assassination attempt.

#french revolution#frev#frev art#frevblr#frev community#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#no signature art#someone write a gen fanfic ab this and tag me please

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Frev comic gained traction on Instagram. Earlier today I was so happy, and I thought

"Yay! Now I can correct some myths about Robespierre to more people!"

Then I got these comments:

And now I'm like "Oh...I have to correct some myths to more people..."

I was trying so hard to keep my cool and just recommend books as I read this comment lmao

#frev#french revolution#frev community#cant handle this at this time of night lol#Just want to reply 'Its so much more complicated then that!' but also dont want to waste time writing essays to strangers on the Internet

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi

this is just a quick thing i made im gonna get around to things soon

#dupsmoulins?#caplessis???#what???#leafdiarist#Leafdiarist???#leafdiarist it is#if you have better ship name suggestions please lmk.#update as I am writing this as a draft...#my friend said that caplessis sounds like a scientific process.#I cannot stop thinking abt this now omaig#they also said dupsmoulins sounds funky 😭...#idrc if you guys use these names go fuck around with it if you would like#lucile desmoulins#camille desmoulins#frev#frev shitposting#frevblr#jumps and backflips and jumps again#antoine with a triple e's art or sumn

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

Idk if you still have requests open but if yes can you draw Prieur wearing a choker with a π shaped charm (like this: https://www.amazon.com/necklace-mathematics-jewelry-math-teacher/dp/B01FLW687U) ? 🥺

sorry for the long reply! finally made it to your request :]

it seems that Prieur likes it!!

#my art#french revolution#frev#claude antoine prieur#that reminds me – i often go by π-rie on social media... but π got there because of ancient greek :_D#for anyone who sees this: requests are... semi open??? i see your requests but it might take me a long time to finish all of them ^_^#like you can write your requests just be prepared to be patient with me ok :_DD

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Click for better quality

Help me, my dear friend!

Sooooooo

Because these two have literally been occupying my mind the moment I found out about simonne's existence, I decided to draw them!!!!!!! As one does.

These two together, specifically Simonne, ARE SO UNDERAPPRECIATED

AGHJJHH I WISH WE KNEW MORE ABOUT HER AND MARAT'S LIFE TOGETHER

Well. We know quite a handful of information about them but IT'S NOT ENOUGH FOR ME

Whyyyyyy aren't there more people talking about simonne. She is so awesome. She's extremely politically active, attending the cordeliers club even after marat died, literally funding the publication of his newspapers that would change the hypothetical political tides of France during the revolution and cause big changes for the better, HER DEDICATION TO MARAT IN GENERAL, TO THE POINT OF PROTECTING MARAT'S LIFE FROM LAFAYETTE'S AGENTS MULTIPLE TIMES OVER THE COURSE OF TIME THEY KNEW EACH OTHER, because she truly saw something in him that most people, even to this day, don't see. They understood each other, and not a lot of people can say they understand marat. How she stood by him, even when his chronic illness got worse, and more people were out to get him, their entire relationship is just..... It's just so special to me.

I kind of hate myself more and more by the day because of my chronic illness, aaaand I feel like I'm not worth any dedication from anyone. Because. I feel like i'm just too much to deal with. Too much to take care of. My back pains, constant low energy, and just!!!!!! Never as good as I could be!!!! Aaaahhhh!!!!!! Hahahaha

But the existence of these two. Like. It might sound silly but I feel hopeful knowing they existed. That despite everything horrible that was sent towards marat, despite his illness becoming worse and worse... He was going to be okay at the end, because he had simonne, who was never going to give up on him!!!! Because he was worth the hard work!!!!! And she loved him!!!!!! And he loved her!!!!!! And I won't ever allow anyone to forget them!!!!!! You hear me?!??? Now who wants to be my simonne?!?!!!!?!

#simonne evrard#simone evrard#why are there 2 ways of writing her name????? lmao#marat#jean paul marat#frev#frev community#oh my god i love them so much#MY SWEETIES#THEY ARE DEFINITELY ONE OF MY FAVORITES#tea art 🎨#oklo makes a post

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frev Halloween I. 🦇

As we are getting into the spooky season, I remembered @robespapier 's great idea to do a Frev Community Halloween event .

I thought the concept was super fun, so I wrote a little something. French Revolution meets Mary Shelley's Frankenstein in a way, just with more blood and less electricity. It's only a start, but I'll do my best to keep at it.

Hope you enjoy & I wish everyone a great start of the Halloween season!

#frev#frevblr#frev community#french revolution#frev art#frev halloween event 2024#frev halloween#halloween#halloween challenge#history#1700s#18th century#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#charlotte robespierre#ao3#fanfiction#fanfic#short story#spilled ink#horror#mary shelley#frankenstein#ish#Lin writes

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anxious Maxime

I bring you short text, inspired by this picture by @octavodecimo:

Steps on the stairs. Is that door really locked? What if they got all the way to the house and are going to finish what they couldn't before? They won't let them in. Reliable people, your friends, are watching outside. Friends? I don't have friends. Really? I think you are wrong. Antoine is not in Paris. Couthon is ill… Your family won't protect you? Augustine, the Duplays… could those killers hurt them instead of me? Maybe… if you hide in the dark like a rat. Didn't you say you welcome death? That you would be willing to undergo it when the time comes? Sure, but my time hasn't come yet…there's still so much to do. You're right, there's always plenty of time to die. That is the talk of cowards. You spoke differently in the club. Who will follow you if you don't face your fear? That's not… Isn't it fear? Who do you want to lie to? You're shaking - look at your hands. Okay, I'm really scared. I'm scared that everything will end with me. The Revolution will lose direction, the republic will collapse or be destroyed. Because everything depends on you? Do you embody the Revolution? Aren't you a bit conceited? Don't laugh. That's not conceit, that's reality. Only I have the good of people at heart. I want to lead it to something better, higher, more ideal. But I am surrounded by so many enemies of virtue, so many conspirators and murderers. Perhaps you would succeed better as a martyr to the Revolution. They would honor your name, celebrate your sacrifice. While this way… While this way what? You know how it all ends, don't you? And you really don't know? Can't you feel it? The hatred, jealousy, deceit and betrayal… I feel… every day, every hour… they gather around me like wolves. But that's why I still have to live to defeat them. Otherwise, everything we've built will crumble. And what if you fail? Then I will die with honor. But that won't happen today. So why don't you go down? They're calling you, can't you hear? I'm afraid…

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joyeux anniversaire, Ami du Peuple!

I know it's been a long time since I've been here. I'm doing my best to come back, but in the meantime I'll leave you with a video I've prepared especially for this occasion - Marat's birthday. This is a short compilation of clips showing some of Jean-Paul's portrayals in media. And yes, I chose this song! All the clips that appear in the video can be seen in full here.

Vive MARAT !

#marat#jean paul marat#happy marat day! 🦦#frev#french revolution#my posts#the region where i live is facing severe weather crises and that's why i've been away from tumblr#the scenario is practically apocalyptic here but fortunately i'm fine!#i've missed writing and posting about marat#hope y'all are doing ok :)

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

You think I’m joking, pal. I’ve just ordered a used copy of an out-of-print 600-pages book on the cultural impact of French Revolution on the world of theatre, art, and literature just to do research for the non-romance subplots of a Frev dating sim that I’ll maybe write one day, and you think I’m joking.

@theorahsart

#writeblr#writers of tumblr#amwriting#writers on tumblr#writeblr community#writing community#writing#frev#robespierre#saint just#camille desmoulins

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

How close Desmoulins and Fréron were? And what did they think of each other? I'm asking because I discovered they managed a journal together, La Tribune des Patriotes.

The seventeen year old Fréron was enrolled as a paying boarder at the college of Louis-le-Grand on September 30 1771, and just a day later, the eleven year old Camille was as well. I have however not been able to discover any evidence indicating the two were friends back then, or even an instance of one referring to the other as ”college comrade,” something which Camille otherwise is proven to have done with a whole lot of other fellow students. Perhaps this should be read as a sign the two did not know each other back then, six years after all being a rather big age difference for kids. They also don’t exactly appear to have been the same type of student, Desmoulins winning a total of four prizes during his time at the college and Fréron zero, and their teacher abbé Proyart admitting (despite his massive hostility) that student Camille had ”some success,” while Fréron ”showed few talents” and ”was cited as a rare example when speaking of laziness and indolence.” (for more info on the school days of them and other Louis-le-Grand students, see this post).

Fréron graduated from the college in 1779, Camille five years later. I have not been able to find anything suggesting they had anything to do with each other in the 1780s either. But on 23 June 1790, one year into the revolution, we find the following letter from Fréron to Camille, showing that the two by this point have forged a friendship. Judging by the content of the letter, said friendship was probably much grounded in their joint status as freshly baked patriotic journalists (Desmoulins had founded his Révolutions de France et de Brabant in November 1789, Fréron his l’Orateur du Peuple in May 1790):

I beg you (tu), my dear Camille, to insert in your first number the enclosed letter, which has so far only appeared in the journal of M. Gorsas; its publicity is all the more interesting to me as I have just, I am assured, been denounced to the commune as one of the authors of l’Ami du Roi. It is a horror that I must push back with all the energy I can. If you cannot insert it in full, in petit-romain, at the end of your first number, at least make it known by extract; you would be doing me a real service. It’s been a thousand years since I last saw you; I have had a raging fever for more than a fortnight which has prevented me from returning to Rue Saint-André; but I will go there next Saturday. Ch. de La Poype came to your house with a letter from M. Brissot de Warville, but he was unable to enter. It was to talk to you about a matter that you no doubt know about. If patriotic journalists don't line up, then goodbye freedom of the press. A thousand bonjours, my dear Camille I am very democratically your friend, Stanislas Fréron.

l’Orateur du Peuple has unfortunately not gotten digitalized yet, so we can’t check if Fréron wrote anything about Desmoulins there that could tell us more about their relationship. But in Révolutions de France et de Brabant we find Camille listing Fréron among ”journalists who are friends of truth” (number 37, August 9 1790), calling him a patriot (number 33, July 12 1790), protesting when national guards were sent to seize the journals of Fréron and Tournon (number 63, February 7 1791) and when the numbers of Fréron and Marat got plundered (number 83, July 4 1791), as well as republishing parts of the journal he finds inspiring (number 83, number 85 (July 18 1791). In both number 1 (November 28 1789) and number 65 (February 21 1791) Camille republished a poem he had written in 1783 that mocked Fréron’s father, the famous philosopher Élie Fréron, as well as his maternal uncle Thomas-Marie Royou, him too a member of the counter-enlightenment (and who, as a sidenote, had also been one of their teachers at Louis-le-Grand). Given Fréron’s open hostility towards both his father and uncle, it does however seem unlikely for this to have had any negative effect on their relationship.

Just a few days after the letter from Fréron to Desmoulins had been penned down, we find the two about to enter into partnership. On July 4 1790 the following contract was signed between Camille, Fréron and the printer Laffrey (cited in Camille Desmoulins and his wife: passages from the history of the dantonists (1874) by Jules Claretie), establishing that from number 33 of Révolutions de France et de Brabant and onwards, Fréron will be in charge of half the pages of the journal, while he from number 39 and forward will be in charge of an additional sheet particulary devoted to news:

We, the undersigned, Camille Desmoulins and Stanislas Fréron, the former living on Rue du Théâtre Français, the latter on Rue de la Lune, Porte St. Denys, of the one part; and Jean-Jacques Laffrey, living on Rue du Théâtre Français, of the other part, have agreed to the following: . 1. I, Camille Desmoulins, engage to delegate to Stanislas Fréron the sum of three thousand livres, out of the sum of ten thousand livres, which Jean-Jacques Laffrey has bound himself, by a bond between us, to pay me annually as the price of the editing of my journal, entitled Révolutions de France et de Brabant, of three printed sheets, under the express condition that said Stanislas Fréron shall furnish one sheet and a half to each number, and that during the whole term of my agreement with said Laffrey. 2. I, Stanislas Fréron, engage to furnish for each number of said journal of Révolutions de France et de Brabant, composed of three sheets, one sheet and a half, under the direction of the said Camille Desmoulins, with the understanding that this sheet and a half shall form one half of the three sheets of which each number is composed. I engage to deliver a portion of the copy of this said sheet and a half on the Wednesday of each week , and the rest during the day on Thursday, and this counting inclusively from the thirty-third number until the close of the agreement between Camille Desmoulins and Jean-Lacques Laffrey. 3. I, Jean-Jacques Laffrey, accept the delegation made by Camille Desmoulins of the sum of three thousand livres, payable, in equal payments, at the issue of each number, to Stanislas Fréron, to the clauses and conditions hereinunder; and I engage, besides, to pay to said Stanislas Fréron the sum of one thousand livres, also payable in equal payments, on the publication of each number, which thousand livres shall be over and above the said salary of three thousand livres on condition that the said Stanislas Fréron shall furnish to the journal an additional sheet per week which shall be devoted to news to begin from the thirty-ninth number, which commences the approaching quarter. And I, Stanislas Fréron, engage to furnish , at the stipulated periods the said sheet over and above, in consideration of the sum of one thousand livres, in addition to the three thousand livres delegated by Camille Desmoulins. Done, in triplicate, between us, in Paris, July 4, 1790. Stanislas Fréron, Laffrey, C. Desmoulins.

According to Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018) by Hervé Leuwers, nothing did however come about from this contract, Révolutions de France et de Brabant continuing to rest under the authority of Camille only, while Fréron instead kept going with his l’Orateur du Peuple. Why this project never saw the light of day one can only speculate in…

When Camille and Lucile got married in December 1790, Fréron neither signed the wedding contract on the 27th, nor attended the wedding ceremony on the 29th. Following the marriage they did however become neighbors, the couple moving to Rue du Théâtre 1 (today Rue de l’Odeon 28), and into the very same building where Fréron had gone to live a few months earlier.

In number 82 (June 27 1791) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant, Camille writes that he a week earlier, the same night the royal family fled Paris, he left the Jacobins at eleven o’clock in the evening together with ”Danton and other patriots.” The Paris night comes off as so calm Camille can’t stop himself from commenting on it, whereupon ”one of us, who had in his pocket a letter of which I will speak, that warned that the king would take flight this night, wanted to go observe the castle; he saw M. Lafayette enter at eleven o’clock.” According to Hervé Leuwers’ biography, this person was Fréron, though I don’t understand exactly how he can see this…

A little less than a month later, July 17 1791, Fréron and Camille find themselves at Danton’s house together with several other people discussing the lynching of two men at the Champ-de-Mars the same morning. At nine o’clock, Legendre arrives and tells the group that two men had come home to him and said: We are charged with warning you to get out of Paris, bring Danton, Camille and Fréron, let them not be seen in the city all day, it is Alexandre Lameth who engages this. Camille, Danton and Fréron follow this advice and leave, and were therefore most likely absent from the demonstration and shootings on the Champ-de-Mars the very same day (this information was given more than forty years after the fact by Sergent-Marceau, one of the people present, in volume 5 of the journal Revue rétrospective, ou Bibliothèque historique : contenant des mémoires et documens authentiques, inédits et originaux, pour servir à l'histoire proprement dite, à la biographie, à l'histoire de la littérature et des arts (1834)).

In the aftermath of the massacre on Champ de Mars, arrest warrants were issued against those deemed guilty for them. On July 22, the Moniteur reports that the journalists Suleau and Verrières have been arrested, and that the authorities have also fruitlessly gone looking for Fréron, Legendre, Desmoulins and Danton, the latter three having already left Paris. Both Fréron and Camille hid out at Lucile’s parents’ country house in Bourg-la-Reine, as revealed by Camille in number 6 (January 30 1794) of the Vieux Cordelier. The two could resurface in Paris again by September.

On April 20 1792, the same day France declared war on Austria, Camille and Fréron again put their hopes to the idea of a partnership from two years earlier. That day, the two, along with booksellers Patris and Momoro, signed a contract for a new journal, La Tribune des Patriotes, whose first number appeared on May 7 (they had tried to get Marat to join in on the project as well, but he had said no). In the contract, Fréron undertook to each week bring 2/3 of the sheets, Camille the rest. According to Leuwers, Camille did nevertheless end up writing most of it anyway. The journal did however fail to catch an audience and ran for only four numbers.

On June 23 1792 Lucile starts keeping a diary. It doesn’t take more than a day before the first mention of Fréron, in the diary most often known as just ”F,” appears — ”June 24 - F(réron) is scary. Poor simpleton, you have so little to think about. I’m going to write to Maman.” One month and one day later Camille tells Lucile, who is currently resting up at Bourg-la-Reine after giving birth, that ”I was brought to Chaville this morning by Panis, together with Danton, Fréron, Brune, at Santerre’s” (letter cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république). Lucile returned to Paris on August 8. In a diary entry written by her four months later it is revealed that both Fréron and the couple were at Danton’s house on the eve of the insurrection of August 10 — ”F(réron) looked like he was determined to perish. "I'm weary of life," he said, "I just want to die." Every patriot that came I thought I was seeing for the last time.” She doesn’t however, and can in the same entry instead report the following regarding the period that immediately followed the successful insurrection:

After eight days (August 20) D(anton) went to stay at the Chabcellerie, madame R(obert) and I went there in our turn. I really liked it there, but only one thing bothered me, it was Fréron. Every day I saw new progress and didn't know what to do about it. I consulted Maman, she approved of my plan to banter and joke about it, and that was the wisest course. Because what else to do? Forbid him to come? He and C(amille) dealt with each other everyday, we would meet. To tell him to be more circumspect was to confess that I knew everything and that I did not disapprove of him; an explanation would have been needed. I therefore thought myself very prudent to receive him with friendship and reserve as usual, and I see now that I have done well. Soon he left to go on a mission. (to Metz, he was given this mission on August 29 1792) I was very happy with it, I thought it would change him. […] F(réron) returned, he seems to be still the same but I don't care! Let him go crazy if he wants!…My poor C(amille), go, don’t be afraid…

Following Fréron’s return from his mission, he hung out with the couple quite frequently. On January 7 1793 we find the following letter from him to Lucile:

I beg Madame Desmoulins to be pleased to accept the homage of my respect. I have the honour to inform her that my destination is changed, that I shall not go to the National Assembly because I am setting out for the countryside with MM Danton and Saturne (Duplain). Will she have the goodness to present herself at the assembly, before ten o’clock, in the hall of deputations; she is to send for M. La Source, the secretary, who will come to her, and she will find a place for her by means of the commissary of the tribunes. I renew the assurence of my respectful devotion to Madame Desmoulins. Stanislas Fréron. Kindest regards to Camille.

Two weeks later, January 20, Lucile writes ”F(réron), La P(oype) came in the evening.” The day after that Fréron writes her the following note: ”I beg the chaste Diana to accept the homage of a quarter of a deer killed in her domains. Adieu. Stanislas Lapin.” This is the first known apperance of Fréron’s nickname within the inner circle — Lapin (Bunny). In Correspondance inédite de Camille Desmoulins(1834), Marcellin Matton, friend of Lucile’s mother and sister, writes that it was Lucile who had come up with this nickname, and that it stemmed from the fact Fréron often visited the country house of Lucile’s parents at Bourg-la-Reine and played with the bunnies they had there each time. In her diary entry from the same day, Lucile has written: ”F(réron) sent us venison.” The very next day she writes the following, showing that Fréron, as she already put it in December, ”appears to still be the same”:

Ricord came to see me. He is always the same, very brusque and coarse, truly mad, giddy, insane. I went to Robert’s. Danton came there. His jokes are as boorish as he is. Despite this, he is a good devil. Madame Ro(bert) seemed jealous of how he teased me… F(réron) came. That one always seems to sigh, but his manners are bearish! Poor devil, what hope do you hold? Extinguish a senseless r [sic] in your heart! What can I do for you? I feel sorry for you... No, no, my friend, my dear C(amille), this friendship, this love so pure, will never exist for anyone other than you! And those I see will only be dear to me through the friendship they have for you.

One day later, January 23, Lucile writes: ”F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite happy and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire.” The day after that she has written the following, and while it’s far from confirmed Fréron is the one she’s alluding to here, it would fit rather well with the previous entries:

What does this statement mean? Why do I need to be praised so much? What do I care if I please? Do you think I’ll be proud of a few attractions? No, no, I know how to appreciate myself, and will never be dazed by praise. To you, you’re crazy, and I’ll make you feel like you need to be smarter.

Lucile’s diary entries abruptly end on February 13 1793, and a month later, March 9, Fréron was tasked with going on yet another mission by the Committee of Public Safety. This time, it would be a whole year before he was back in Paris again. It is probably during this period the following two undated letters from Fréron’s little sister Jeanne-Thérèse, wife of the military leader Jean François La Poype, were penned down and sent off to Lucile (both cited within Camille Desmoulins and his wife… (1874) by Jules Claretie. I also found a mention of a third, unpublished letter with the same sender and receiver):

Coubertin, this Monday morning. How good you are, my dear Lucile, to take such pains to answer so punctually, and to relieve my anxiety! I rely upon your kindness to let me know any good news when you know it yourself. Neither my husband nor my brother has written to me; but, according to what you tell me, M. De la Poype will be with you immediately. Scold him well, I beg, my dear Lucile, and beat him even, if you think it necessary; I give him over to you. Goodbye, dear aunt; I embrace you with all my heart. Do tell me about your pretty boy; is he well? We shall, I hope, see him at some time together. Be the first to tell me of my husband's arrival ; it will be so sweet to owe my happiness to you! Fanny is perfectly well. I received most tenderly the kiss she gave me from you. My compliments to your husband. Fréron de la Poype.

Here I come again, beautiful and kind Lucile, to plague you with my complaints, and the frightful uneasiness by which I am tormented. The letter your husband had the kindness to write to me does not allay my grief; he tells me that my brother has given him news of my husband, but he had not heard from him before his departure. He has not been absent long enough to have had time to give us news of himself since he set out. I do not hide from you, dear Lucile, state; for pity's sake, try to restore composure to my heart; let me owe tranquillity to you. They say the enemy is within forty leagues of Paris; if this is so, the country will not be safe. Will you promise to warn me of danger, and to receive me into your house? I count upon the friendship you have always been willing to show me, and I shall throw myself into your arms with the greatest confidence. I beg you to give my compliments to your dear husband. Fréron de La Poype. Coubertin, near Chevreuse. The 5th. Madame Desmoulins.

On October 18 1793, Fréron too picks up his pen again and writes the following two letters, one to Camille and one to Lucile. He is at the time in Marseille preparing for the siege of Toulon, a subject which he spends the majority of the ink on discussing, but also blends this with nostalgic remarks. Fréron addresses Camille with tutoiement, but Lucile with vouvoiement. The parts in italics got censored when the letters for the first time got published in Correspondance de Camille Desmoulins(1834):

Marseille, October 18 1793, year 2 of the republic one and indivisible Bonjour, Camille, Ricord will tell you about a lot of things. Our business in front of Toulon is going badly. We have lost precious time and if Carteaux had left La Poype to his own devices, the latter would have been master of the place more than fifteen days ago, but instead, we have to hold a regular siege and our enemies grow stronger every day by the way of the sea. It is time for the Committee of Public Safety to know the truth. I am going to write to Robespierre to inform him about everything. You may not know everything that has happened to me; I have upheld my reputation as an old Cordelier, for I am like you from the first batch; and although very lazy by nature (I say my fault), I found in the great crises a greater activity than I would have believed. But it was a question of saving the south and the army of Italy; because I am not talking about my skin; for a long time [unreadable word for me] have been an object of [unreadable word] for the counter-revolutionaries without [unreadable word]. I will prevent Toulon from forming its sections and consequently from opening its port to the English and from dragging us, at the onset of winter, into the lengths of a murderous siege. La Poype commands a division of the army in front of Toulon; you have no idea how Carteaux makes him swallow snakes: he had seized the heights of Faron, a mountain which dominates a very important fort from which one can strike down and reduce Toulon. Well! Carteaux left him at this post without reinforcement, and he was obliged to evacuate it. Carteaux would rather have the capture of Toulon delayed and missed twenty times than allow another to have the glory. Speak, thunder, burst. La Poype did not contradict himself for a single moment; you know him, he has not changed. I am perhaps a little suspicious: that is why I abstain from writing on his account; but ask all those who come from here and they will tell you what the patriots think. Did you learn from Father Huguenin that I had printed in Monaco six thousand copies of your Histoire des Brissotins which I distributed profusely in Nice and in the department of Var? You did not think you would receive the honors of printing in Italy. You see it's good to have friends everywhere. I have been very worried about Danton. The papers announced that he was ill. Let me know if he’s recovered. Tell him and give him a thousand regards from me. I look forward to seeing you again, but this after the capture of Toulon; I dream only of Toulon; it’s my nec plus ultra. I will either perish or see its ruins. Is Patagon (Brune) in Paris? Remind me of him. Farewell, my dear Camille, tell me the story of Duplain Lunettes. Is it true that he is in prison? Attacking Chaplain! ah! he is such a good man! Tell me the reasons for his detention. Has he really changed? This is inconceivable. We are doing a lot of work here; we are impatiently awaiting the troops which were in front of Lyon and the siege artillery which we lack; without that the only thing we would make in Toulon would be clear water. Answer me in grace; Ricord will give you my address. I embrace you. Fréron. PS. You have known for a long time that I love your wife madly; I write to her about it, it is indeed the least consolation that can be obtained for an unhappy bunny, absent since eight months. As there is a fairly detailed article on La Poype, I invite you to read it. Adieu, both of you, think sometimes of the best of your friends; answer me as well as Rouleau (Lucile).

Marseille, October 18 1793, year 2 of the republic one and indivisible How lucky Ricord is! So he is going to see you again, Lucile, and I, for a century, have been in exile. Communications between the southern departments with Paris have been closed for more than three months. Ever since they’ve been restored, I have wanted to write to you. A hundred times I have picked up the pen, and a hundred times it has fallen from my hand. He is leaving, this fortunate mortal, and I finally venture to give him this letter for you, the content of which he is unaware about. May it convince you, Lucile, that you have always been in my thoughts! Let Camille murmur about it, let him say all he wants about it, in that he will only act like all proprietor; but certainly he cannot do you the insult of thinking that he is the only one in the world who finds you lovable and has the right to tell you so. He knows it, that wretch of Bouli-Boula, because said in your presence: "I love Bunny because he loves Rouleau."

This poor bunny has had a great deal of adventures; he has traversed furious burrows and he has stored up ample stories for his old age. He has often missed the wild thyme which your pretty hands in small strokes enjoyed feeding him in your garden in Bourg de l’Egalité. Besides, he was not below his mission, exposing his life several times to save the republic. In seeking the glory of a good deed, do you know what sustained him, what he always had before his eyes? First, the homeland, then, you. He only wanted and he only wants to be worthy of the both of you. You will find this romantic bunny and he is not bad at it. He remembers your idylls, your willows, your shrines and your bursts of laughter. He sees you trotting around your room, running over the floor, sitting down for a minute at your piano, spending whole hours in your armchair, dreaming, letting your imagination travel; then he sees you making coffee at the roadside, scrambling like an elf and cussing like a cat, showing your teeth. He enters your bedroom; he stealthily casts a longing eye on a certain blue bed, he watches you, he listens to you, and he keeps quiet. Isn’t that you! Isn’t that me! When will these happy moments return? I don’t know, I am now pressing the execrable Toulon, I am determined to either perish on its ramparts or to scale them, flame in hand. Death will be sweet and glorious to me as long as you reserve a tear for me.

My heart is torn, my mind devoted to a thousand cares, My sister and my niece, little Fanny, are locked up in Toulon in the hospital like unfortunates; I can't give them any relief and they may lack everything. La Poype, who adores her, but still more his homeland, besieges and presses this infamous city; he cannons and bombards it without reserve, and, as the price of such admirable devotion, he is calumniated, he is hampered, his efforts are paralyzed, he is left devoid of arms, cartridges, and artillery; they water him with bitterness, they cast doubts on his civism; and while Carteaux, to whom Albitte has made a colossal reputation, but who is in a condition to take Toulon no more than I am the moon, seeks, through the lowest jealousy, to lose him in the mind of the soldier, sometimes by passing him off as a counter-revolutionary, sometimes by spreading the rumor that he has emigrated and fled to Toulon. He alone attempts daring blows, and having made himself master of a fort which dominates Toulon, he would have taken that town in a week, if Carteaux had sent him the reinforcements he in vain asked for. One thing that must not be forgotten is that in the army of Italy, the traitor Brunet, the federalist Brunet, made La Poype pass for a Maratist and an outraged montagnard. Why? Because the staff of which he was the chief, had been composed by him only of Marseillois from the 10th of August and of Cordeliers. This is the truth. Make it known to your husband. Prevent from being oppressed the most patriotic general officer perhaps of all the armies, who has never contradicted himself; who has sacrificed his wife and child to the homeland; who began by besieging the Bastille with Barras and me; who since has not varied; who has worked for a long time with l’Orateur du Peuple; who was decreed in the affair of the Champ-de-Mars, etc, etc. I leave it to your so persuasive mouth to assert these titles.

I embrace you, divine Rouleau, dearer than all the rouleaux of gold and crowns that could be offered to me. I embrace you in hope, and I will date my happiness only from the day when I shall see you again. Remind me of your dear maman and of citizen Duplessis. Will you answer me? "Oh! no, Stanislas!” Please answer me, if only because of La Poype. Show my letter to Camille, for I do not wish to make a mystery of anything.

Lucile wrote a response to Fréron that has since gone missing, but it was clearly satisfying for him judging by his next letter, dated December 11 (incorrectly September 11 in the published correspondance) 1793 and addressed to Lucile:

No, my answer will not be delayed by eight months as you put it; the day before yesterday I received, read, reread and devoured your letter; and the pen does not fall from my hands when it comes to acknowledge receipt. What pleasure it gave me !... Pleasure all the more vivid than I dared to hope! You think, then, of that poor bunny, who, exiled far from your heaths, your cabbage, your wild thyme and the paternal dwelling, is consumed with grief at seeing the most constant efforts for the glory and the strengthening of the republic lost... They denounce me, they calumniate me, when all of the South proclaims that without our measures, as active as they are wise and energetic, all this country would be lost and given over to Lyon, Bordeaux and the Vendée. I did not deign to answer Hébert (Fréron (and La Poype) had been denounced at the Jacobins on November 8 by Hébert, who said he ”was nothing more than an aristocrat, a muscadin”). I thank your wolf for having defended me, but he, in his turn, is denounced. They want to take us one after the other, saving Robespierre for last. I invite your wolf to see Raphaël Leroy, commissioner of war for the Army of Italy, who saw me in the most stormy circumstances and the most critical situation in which a representative of the people has ever been. He will say if I am a muscadin, a dictator and an aristocrat. This Leroy is one of the first Cordeliers. Camille knows him; no one is in a better position to make the truth about La Poype and me triumph.

I dare say that never has a republican behaved with more self-sacrifice than your bunny. The fact that La Poype is my brother-in-law was enough for me to make it a rule to keep him away from all command-in-chief, albeit his rank and his seniority, but even more his foolproof patriotism called him there. From then on I foresaw everything that malevolence would not fail to spread. I’d rather be unjust towards La Poype, and make obvious privileges, than I’d give arms to slander, and make people suspect even that the most vicious motives of ambition or of particular interest were involved in my conduct for some reason. When Brunet was dismissed, what better opportunity to advance La Poype? He came to command naturally and by rank. He was the oldest officer-general of the army of Italy. Well! I dismissed him and we named the oldest member of the same army, a man who had only been a general of division for a fortnight, and yet La Poype wanted to sacrifice his wife and his child, saving the national representation, with the certainty that both were going to be delivered to the Toulonnais, which did indeed happen. And these are the men that the most execrable system of defamation pursues! Vulgar souls, muddy souls, you have lent us your baseness; you could not believe, still less reach the height of our sentiments; but the truth will destroy your infernal machinations; we will do our duty through all obstacles and disgusts; we will continue to be useful to the republic, to devote ourselves to its salvation; we will sacrifice our wives and our sisters to it; we will make to our fellow citizens the faithful presentation of our actions, our labors and our most secret thoughts, and we will say to our denouncers: have you produced more titles than us to the public esteem?

Dear Lucile, tell your wolf a thousand things from me; make sure he puts forward these reasons based on notorious facts. Pay him my compliment on his proud reply to Barnave; it is worthy of Brutus, our eternal model; I am like you; a gloomy uneasiness agitates me; I see a vast conspiracy about to break out within the republic; I see discord shake its torches among the patriots; I see ambitious people who want to seize the government, and who, to achieve this, do everything in the world to blacken and dismiss the purest men, men of means and character. I am proof of that. Robespierre is my compass; I perceive, in all the speeches he holds at the Jacobins, the truth of what I am saying here. I don't know if Camille thinks like me; but it seems to me that one wants to push the popular societies beyond their goal, and make them carry out, without them suspecting it, counter-revolution, by ultra-revolutionary measures. What has just happened in Marseille is proof of this. The municipals who had dared to give the order to two battalions of sans-culottes whom we had required to march on Toulon, not to obey the representatives of the people, and who, for this audacious and criminal act, were dismissed by us, were embraced and applauded in the popular society of Marseilles, as the victims of patriotism. Fortunately we have stifled any counter-revolutionary movement; the largest and most imposing measures were taken on the spot. Many intriguers who only saw in the revolution a means of making a fortune, or of satisfying revenge or particular hatreds, dominated and led society astray, all the more easily because they are interesting in the eyes of the people through the persecutions of the sections and a few months in prison. Do you believe that there were secret committees where the motion was made to arrest the representatives of the people? Within twenty-four hours, we have mixed up all these plots: Marseille is saved. It must be observed that this new conspiracy broke out the very day when the English pushed three columns upon our army before Toulon, and seized the battery of the convention, from which they were repulsed with a terrible loss on their side.

It is not useless to notice again that the aristocrats, the emissaries of Pitt, the false patriots, the patriots of money who see their small hopes destroyed by these acts of vigor, repeat with affectation what has been said about me by Hébert at the rostrum of the Jacobins. But the vast majority of true republicans do me justice. This is the harm produced by vague denunciations, made by a patriot against patriots. I see it well; Pitt and the people of Toulon, who doubt our energy because they have tested it on more than one occasion, want, by all possible means, to keep us away from the siege of Toulon, because it is known that we are going to strike the great blows. Well! let us be reminded; we are ready. The national representation did not cross our heads like so many others. Don't come here, lovable and dear Lucile, it's a terrible country, whatever people say, a barbaric country, when you've lived in Paris. I have no caves (cavernes) to offer you, but many cypresses. They grow here naturally. Tell your glutton of a husband that the snipes and thrushes here are better than the inhabitants. If it weren't so far from here in Paris, I would send him some, but you will receive some olives and oil. Farewell, dear Lucile, I am leaving immediately for the army. The general attack is about to begin; it will have taken place when you receive this letter. We are counting on great successes and to force all the posts and redoubts of the enemy with the bayonets. My sister is still locked up in Toulon. This consideration will not stop us: if she perishes, we will give tears to her ashes; but we will have returned Toulon to the republic. I thank you for your charming memory; La Poype, whom I do not see, because he is in his division, will be very sensitive to it. Farewell once again, madwoman, a hundred times mad, darling rouleau, bouli-boula of my heart; this is a very long letter; but I gave myself up to the pleasure of chatting with you, and I took the night for it. Tell loup-loup to write to me; he's a sloth. With regard to your reply to this one, it will probably take a year to arrive. What does it matter to me! On the contrary. It's clear as day. I remember those unintelligible sentences; I remember that piano, those melodies, that melancholy tone, abruptly interrupted by great bursts of laughter. Indefinable being!... Farewell. I embrace the whole warren and you, Lucile, with tenderness and with all my soul. Stanislas.

PS - Don't forget me to the baby bunny (Horace) and his pretty grandmother Melpomène. I would also like to hear from Patagon (Brune), Saturn (Duplain) and Marius (Danton). The latter must have received a letter from me. I will write to him again. Make sure Camille communicates the parts of this letter regarding La Poype, and that his eloquent voice pleads the cause of a friend always worthy of him, always worthy of the Cordeliers. Remind us of his memory, for we love him and are attached to him for life. Consternation is in Toulon. We have killed the English, at the last incident, all their grenadiers. The Spaniards are assassinating them with their stilettos. They have already stabbed thirty of them. It’s now or never to attack. So I am leaving; the cannonade will begin as soon as we will have arrived. We are going to win laurels or willows. Prepare, Lucile, what it is you intend for me.

In the fifth number of the Vieux Cordelier, released January 5 1794, Camille did like Fréron had asked and defended both him and la Poype, clearly using Fréron’s letter as a source:

Note here that four weeks ago, Hebert presented to the Jacobins a soldier who came to heap pretentious praise on Carteaux and to discredit our two Cordeliers Fréron and La Poype who nevertheless had come close to taking Toulon in spite of envy and slander; because Hebert called Freron, just as he called me, a ci-devant patriot, a muscadin, a Sardanapalus, a viédasse. Take note citizens that Hebert has continued to insult Fréron and Barras for two months, to demand their recall to the Committee of Public Safety and to commend Carteaux, without whom General La Poype would perhaps have retaken Toulon six weeks ago, when he had already seized Fort Pharon. Take note that when Hébert saw that he could not influence Robespierre on the subject of Fréron because Robespierre knows the Old Cordeliers, because he knows Freron just as he knows me; note that it was then that this forged letter signed by Fréron and Barras arrived at the Committee for Public Safety, from where no one knows; this letter which so strongly resembled one which managed to arrive two days ago at the Quinze Vingts, which made out that d’Eglantine, Bourdon de l’Oise, Philippeaux and myself wanted to whip up the sections. Oh! My dear Fréron, it is by these crude artifices that the patriots of August 10 are undermining the pillars of the old district of the Cordeliers. You wrote ten days ago to my wife ”I only dream of Toulon, I will either perish there or return it to the republic, I’m leaving. The cannonade will begin as soon as I arrive; we are going to win a laurel or a willow: prepare one or the other for me.” Oh! My brave Fréron, we both wept with joy when we learned this morning of the victory of the republic, and that it was with laurels that we would go to meet you, and not with willows to meet your ash. It was in the assault with Salicetti and the worthy brother of Robespierre, that you responded to the calumnies of Hébert. Things are therefore the same both in Paris and Marseille! I will quote your words, because those of a conqueror will carry more weight than mine. You write to us in this same letter: I don't know if Camille thinks like me; but it seems to me that one wants to push the popular societies beyond their goal, and make them carry out, without them suspecting it, counter-revolution, by ultra-revolutionary measures. What has just happened in Marseille is proof of this. Oh well! My poor Martin (this could be a reference to the the drawing ”Martin Fréron mobbed by Voltaire” which depicts Fréron’s father Élie Fréron as a donkey called ”Martin F.”), were you therefore pursued by the Père Duchesnes of both Paris and Bouches-du-Rhône? And without knowing it, by that instinct which never misleads true republicans, two hundred leagues apart, I with my writing desk, you with your sonorous voice, we are waging war against the same enemies! But it is necessary to break with you this colloquium, and return to my justification.

The very same day, Fréron wrote a third letter to Lucile. Again, the parts in italics were censored when the letter was first published in 1836:

You did not answer me, dearest Lucile, and my punctuality has so dumbfounded you that your astonishment still lasts. You had deferred my answer to eight months; you see if you are a good prophetess. I inform you with a sensitive pleasure (which you will share, I am sure) that my sister and my niece did not perish; that they found a way to wear themselves out in the dreadful night which preceded the surrender of Toulon. She is about to give birth. I informed her of the interest you took in her sad fate; she was very sensitive and asks me to show you her gratitude. Answer me then, lazy that you are, and ungrateful, which is worse. One breaks the silence after a year, after centuries, and one gets, as thank you, a few words written in distraction, Bouli-Boula, what does it do to me? The bunny is desolute; he thinks of you constantly; he thought about you amid bombs and bullets, and he would have gladly said like that old gallant: Ah! if my lady saw me! I realize with sorrow that you are upset, since Camille has been denounced by the same men who have pursued me at the Jacobins. I hope he will triumph over these attacks; I recognized his original touch in a few passages from his new journal; and I too am one of the old Cordeliers. Farewell, Lucile, wicked devil, enemy of bunnies. Has your wild thyme been harvested? I shall not delay, despite all my insults, to implore the favor of nibbling some from your hand. I asked for a month's leave to recover a bit; for I am exhausted with fatigue; afterwards I fly back into the bosom of the Convention, and I stealthily amaze myself on the grass with Martin on the paths of Bourg d’Égalité, under the eyes of la grande lapin? and in spite of your pots of water. You'll have neither olives nor oil if I don't get a response from you. You can tell me whatever you like but I love you and embrace you, right under the nose of your jealous loup-loup. Goodbye once more. Do not forget me to our shared friends. What has become of citoyenne Robert? A thousand things to your old loup-loup; I wanted to write to him, but time is short and the mail rushes me. Tell him to keep his imagination in check a little with respect to a committee of clemency. It would be a triumph for the counter-revolutionaries. Let not his philanthropy blind him; but let him make an all-out war on all industrial patriots. Goodbye again, loveliest of rouleux. My respects to your good and beautiful maman. Give my regards to the baby bunny (Horace). The letter reached Lucile within a week, but it’s with a tone less playful than Fréron’s that she answered it with on January 13 (cited in Camille Desmoulins and his wife (1874) by Jules Claretie):

Come back, Fréron, come back quickly. You have no time to lose; bring with you all the old Cordeliers you can meet up with; we have the greatest need of them. If it had pleased Heaven not to have ever dispersed them! You cannot have an idea of what is going on here! You are ignorant of everything, you only see a feeble glimmering in the distance, which can give you but a faint idea of our situation. Indeed, I am not surprised that you reproach Camille for his Committee of Clemency. He cannot be judged from Toulon. You are happy where you are; all has gone according to the wish of your heart; but we, calumniated, persecuted by the ignorant, the intriguing, and even by patriots; Robespière (sic) your compass, has denounced Camille at the Jacobins; he has had numbers 3 and 4 read, and has demanded that they should be burnt; he who had read them in manuscript. Can you conceive such a thing? For two consecutive sittings he has thundered, or rather shrieked, against Camille. At the third sitting Camille's name was struck off. Oddly enough, he made inconceivable efforts to have the cancelling reported; it was reported; but he saw that when he did not think or act according to their the will of a certain number of individuals, he was not all powerful. Marius (Danton) is not listened to any more, he is losing courage and vigour. D'Eglantine is arrested, and in the Luxembourg, under very grave charges. So he was not a patriot! he who had been one until now! A patriot the less is a misfortune the more. The monsters have dared to reproach Camille with having married a rich woman. Ah! let them never speak of me; let them ignore my existence, let me live in the midst of a desert. I ask nothing from them, I will give up to them all I possess, provided I do not breathe the same air as they! Could I but forget them, and all the evils they cause us! I see nothing but misfortune around me. I confess, I am too weak to bear so sad a sight. Life has become a heavy burden. I cannot even think - thinking, once such a pure and sweet pleasure alas! I am deprived of it… My eyes fill with tears… I shut up this terrible sorrow in my heart; I meet Camille with a serene look, I affect courage that he may not lose his keep up his. You do not seem to me to have read his five numbers. Yet you are a subscriber. Yes, the wild thyme is gathered, quite ready. I plucked it amid many cares. I laugh no more; I never act the cat; I never play my piano; I dream no more, I am nothing but a machine now. I see no one, I never go out. It is a long time since I have seen the Roberts. They have gotten into difficulties through their own fault. They are trying to be forgotten. Farewell, bunny, you will call me mad again. I am not, however, quite yet; I have still enough reason left to suffer. I cannot express to you my joy on learning that your dear sister had met with no accident; I have been quite uneasy since I heard Toulon was taken. I wondered incessantly what would be their fate. Speak to them sometimes of me. Embrace them both for me. I beg them to do the same to you, for me. Do you hear! my wolf cries out: Martin, my dear Martin, here, thou art come that I may embrace thee; come back very soon. Come back, come back very soon; we are awaiting you impatiently.

In number 6 of the Vieux Cordelier, released January 30 1794, Camille responds to Fréron’s critique regarding a committee of clemency while informing him that his father-in-law has gotten arrested:

Beware, Fréron, that I was not writing my number 4 in Toulon, but here, where I assure you that everyone is in order, and where there is no need for the spur of Père Duchesne, but rather of the Vieux Cordelier's bridle; and I will prove it to you without leaving my house and by a domestic example. You know my father-in-law, Citizen Duplessis, a good commoner and son of a peasant, blacksmith of the village. Well! The day before yesterday, two commissioners from Mutius Scaevola's section (Vincent's section, that will tell you everything) came up to his house; they find law books in the library; and notwithstanding the decree that no one will touch Domat, nor Charles Dumoulin, although they deal with feudal matters, they raid half the library, and charge two pickers with the paternal books. […] An old clerk's wallet, which had been discarded, forgotten above a cupboard in a heap of dust, and which he had not touched or even thought about for perhaps ten years, and on which they managed discovered the imprint of a few fleur-de-lis, under two fingers of filth, completed the proof that citizen Duplessis was suspect, and thus he was locked up until the peace, and seals put on all the gates of this countryhouse where you remember, my dear Fréron, that we both found an asylum which the tyrant dared not violate after we were both ordered to be seized after the massacre of the Champ-de-Mars.