#french marxism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

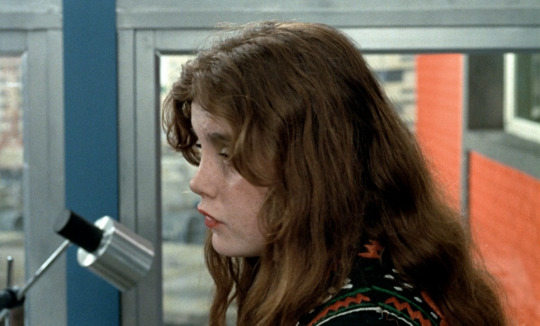

Lizzy Mercier Descloux

#lizzy mercier descloux#new wave#france#punk#post-punk#no wave#disco#dance#aesthetic#hammer and sickle#communism#marxism#french marxism#french music#dance punk#photography#jean luc godard#la chinoise

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mail day. Got these from a friend in Kansas. I already own a copy of Everything is a Game, so I'll probably give that one away.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are many - They are few.

#revolt#revolution#resistance#antifascist#1936#marxism#anti capitalism#general strike#class war#rage against the machine#the international#working class#french revolution#resist#oligarchy#late stage capitalism#class struggle#anti trump

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

The French revolution abolished many privileges, and raised up many of the oppressed; but all it did was replace one class in power by another. Yet it did teach us one great lesson: social privileges and differences, being products of society and not of nature, can be overcome.

Antonio Gramsci, "Oppressed and Oppressors," 1911.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Chinoise - 1967

#la chinoise#1960s#jean luc godard#french new wave#cinema#china#revolution#60s#film#marxist#marxism leninism#movies#poster#mao zedong

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

la chinoise!(1967)

#photography#visual archive#design#art#history#aesthetic#histoire#french#60s#1960s#francais#french film#film photography#film stills#politics#marxism#marxism leninism#socialism#film#la chinoise

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

“He [Napoleon] remained deeply attached to the refusal of the Ancien Régime, to the refusal of national degradation in the face of the Bourbons and aristocratic Europe. It is from this refusal that he will draw the strength to think and set up this powerful resistance movement which will be the return from the island of Elba in March 1815. This is why the forces of the Holy Alliance reject him, ostracizing him from humanity as an ‘anarchist’. He was in his time ‘the revolutionary emperor’ because his conquest was transformative for the social order.”

— Antoine Casanova, Vive la Révolution: 1789-1989: Réflexions autour du bicentenaire

#Antoine Casanova#Casanova#Vive la Révolution: 1789-1989: Réflexions autour du bicentenaire#Vive la Révolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#french empire#history#france#french revolution#La Révolution française#Révolution française#19th century#the hundred days#hundred days#french history#revolution#Marxist history#Marxism

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tout Va Bien (Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Pierre Gorin, 1972)

"I'm not denying that our society has drawbacks. The hard work and aggressiveness that accompany the drive for efficiency risk dehumanizing everyone and destroying the weaker among us. The desire for possessions can lead to frustration, and too much pleasure can make you nauseous. You have to find a balance, and most people find it - or will find it. They have a natural tendency to find balance and adapt because of their need to streamline all aspects of their lives and surroundings."

#jane fonda#yves montand#jean luc godard#jean-pierre gorin#marxism#working class#french cinema#tout va bien

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sans Soleil (1983, Chris Marker)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#feminist history#women in history#radical feminst#socialism#workingclass#marxism#illustration#digital art#french#Pauleminck#communedeparis#lacommunedeparis#communarde#anarchiste

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lenin said, without a theory of revolution it is not possible to have a revolutionary movement. I say, theory and practice are one in the same comrades!

#marxism#communism#socialism#history#marxism leninism#political#american politics#karl says#politics#funny#lenin#vladimir lenin#famous quotes#inspiring quotes#quoteoftheday#quotes#john lennon#lennon#americana#proletariat#bourgeoisieses#socialist revolution#french revolution#revolutionary girl utena#revolutionary sabo#revolver ocelot#american revolution

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

Seriously, just read it if you haven't already. It's available online for free, and it's not even that long!

Not only will you gain a greater understanding of Marx's understanding of history, that viewpoint we call "Historical Materialism", but it's also just a really fun read with some excellent turns of phrase. So go on, read it.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

La France Insoumise

#art#artists on tumblr#digital art#vintage#expiremental#socialism#marxism#communism#design#marxism leninism#france#french socialism#french socialist#french#la france insoumise#jean luc melenchon#Jean-Luc Mélenchon#nupes#New Ecological and Social People's Union#Nouvelle Union populaire écologique et sociale#Parti socialiste#Parti communiste français#communiste#français#socialist art#anti imperialism#anti capitalism#agitprop#gilet jaunes#Nouveau Front populaire

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hell Without Poetry

I started reading Proletarian Nights by Jacques Rancière, about contradictory aspirations held by artisanal workers in early 19th century France. One of the most interesting points so far are the fact that some workers had a culture of emulating bourgeoise fashion and not saving money, both to differentiate themselves from the domestic servants they felt they were superior to, and to signal that they deserved the same privileges as the bourgeoisie but rejected capitalist ethics of accumulating in order to exploit others.

I’ve just gotten into the famous Gauny section, where Rancière goes off an a tangent about this philosophical joiner (someone who makes wooden building components). The first of his books I read was The Ignorant Schoolmaster, which similarly takes up a single historical figure in order to develop their ideas into a universal, ahistorical frame by blending his voice with theirs. I find the idea really interesting, and it makes me wonder if I could do the same for the people I interviewed for my dissertation. I like how it deconstructs the boundary between historical actor and theorist, emphasising that all people are both, but it only works of course if the people you’re quoting are doing a substantial amount of philosophising. I also don’t want to lose marks for a stylistic gambit.

One of Gauny’s ideas is that work is work, always demeaning no matter what its content is. Rancière points out that this is similar to the philosophy of a preacher at the time, who valorised work for its essential self-sacrifice (Max Weber pricks up his ears), because it allows our body to fulfil its debt created by the wage given by the employer. This is obviously ideologically beneficial to the status quo because valuing just particular aspects of work rather than work it and of itself would suggest that those parts should be expanded i.e. that work can be better or worse and might be improved.

However, Gauny twists the message by separating the effect it has on the body from the effect on the soul. He admits that there is a pleasure to physical self-sacrifice - even though hard work of the sort he was doing can have awful long-term consequences, there’s pleasure in the oblivion you can reach in the arduous routine of it - but he emphasises that it kills the soul by not giving you breathing time to sit and contemplate, discuss ideas, and make art. There’s a beautiful section where Gauny says

“Ah, Dante, you old devil, you never traveled to the real hell, the hell without poetry!”

This speaks to the ideas at the heart of Rancière’s entire project: that everyone aspires to critically engage in the arts, and that the extent to which do is not overdetermined by class position. His project in this book in particular is to demonstrate that there is no pure working class - there is frequent infighting within and between professions and genders, and their morality is often inspired by the bourgeoisie.

In fact, one of the most interesting parts is that many of the workers start seriously questioning the status quo only after they’re visited by bourgeois do-gooders, but rather than take on the ideas of these champagne socialists uncritically, they use them to inspire new ideas. Rather than expecting a new world to come from one place, we should recognise that novelty is always a result of the melding of difference. It actually makes me think of the fact that so many of the progressive ideas developed in Europe, from Rousseau to Marx, were inspired by Native American philosophies (David Graeber & David Wengrow’s book, The Dawn of Everything, has a great section on the possible influence on Rousseau).

The aspirations of people like Gauny to write poetry, to come up with new ideas based on a variety of sources, was largely unrecognised or dismissed when Rancière wrote this in the ‘80s. He was frustrated that not only did capitalists view working people as beneath of that sort of thought, but Marxists saw it as counter-revolutionary and therefore unbecoming. Rancière was disillusioned with Althusser, who’s structuralist Marxism he saw as not leaving any space for people to resist their circumstances, instead being overdetermined by class. I don’t know Rancière’s stance on free will, but as a rather dogmatic determinist even I find that frustrating, as if we aren’t influenced by so much else which can give rise to disruptive convergences. Basically, people are more complicated than that! Any supposedly emancipatory philosophy with a single vision of what the working-class should be is doomed to failure, as Rancière well knew from witnessing the dismissal of the student protests of ‘68 be dismissed as “not real revolution”.

Rancière saw in Gauny a way out of this structuralist trap, where by taking on the high-minded ideas of the more romantic bourgeoisie and reinterpreting them with a personal need to act against the system, new ideas could be created and used to disrupt the distribution of the sensible, or the matrix of acceptable ideas - most important of which was the idea of who is capable of having such ideas. This concept is actually where my name comes from!

I wonder if we’re losing this time to contemplate even more today, with the spectacle invading so much of our lives - social media being the quintessential example. This is not such a danger if we’re using it to chat to people, but if we’re just scrolling… there’s not much thinking going on there. 😅 Guy Debord, in the ‘50s, was already talking about capital colonising our everyday life, and this stealing of attention, our time to think and talk and create and have ideas, seems to be the worst consequence of it.

#jacques rancière#marxism#karl marx#david graeber#capitalism#alienation#philosophy#social theory#sociology#history#france#french history#poetry#dante#work#equality#social media#guy debord#spectacle#society of the spectacle

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mentions of Napoleon in Vive la Révolution: 1789-1989: Réflexions autour du bicentenaire, by the Marxist historians Antoine Casanova and Claude Mazauric

The Austrian Chancellor Metternich said: “Bonaparte is Robespierre on horseback.” And we know that Bonaparte deeply admired Robespierre. There are obviously important differences between the two men, between the times and conditions of their exercise of power. When it comes to democracy, the figure of Robespierre challenges us and tells us deeper things today. Coming after Thermidor and the Directory, Bonaparte certainly governed without hesitating to also use the most cynical forms of power, from schemes to compromises of all kinds, usual practices of the European courts which he reinvested even in the dynastic illusion.

But at the same time he remained deeply attached to the refusal of the Ancien Régime, to the refusal of national degradation in the face of the Bourbons and aristocratic Europe. It is from this refusal that he will draw the strength to think and set up this powerful resistance movement which will be the return from the island of Elba in March 1815. This is why the forces of the Holy Alliance reject him, ostracizing him from humanity as an “anarchist”. He was in his time “the revolutionary emperor” because his conquest was transformative for the social order. Marx saw this clearly by emphasizing the immense difference thus existing between Bonaparte and Napoleon III.

We must add this: the campaign which devalues Bonaparte today is the same one that denies Robespierre recognition of his central role in the Revolution. Why is this? Because in the context of the single European market, it’s very important to forget what lies at the root of the very notion of a legitimate state in France, namely the national sovereignty born of the Revolution these men made.

— Antoine Casanova

Sieyès, the “inventor” of the Third Estate, then became the leader of a campaign to “revise” the Institutions. He advocates a strong executive, the government of elites supported by a very broad national consensus expressed by plebiscite or referendum, a government which would thus have the freedom to act. Bonaparte will spearhead this constitutional revision during the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire (November 9, 1799). It will be institutionalized by the Consulate and the Constitution of Year VIII.

Is it still the Republic? It is, to say the least, the survival of the republican idea. The Republic remains as a name but ceases to be a regime in which representation takes place directly, from the body of citizens recognized as such by census suffrage, to the Assembly, which directs and sets the essential directions. From now on, the regime is plebiscitary, that is to say that the consensus of citizens gives power to someone who exercises it freely. The republican myth has been transformed, but what has remained from the Revolution is the idea that all authority can only be legitimately exercised on the basis of a national consensus, the principle of sovereignty from below not being called into question. This is an irreversible achievement.

— Claude Mazauric

This is why, among other things, the comparison between Bonaparte and Hitler is nonsense. Hitler tried to set up a reactionary and conservative Europe against all the ideas of the French Revolution, precisely. Bonaparte did exactly the opposite. His march across Europe, the conquest, even the oppression of the peoples who lived there, were not intended to lock them into the feudal regime, but of getting them out of it. He was “an armed missionary” as Robespierre said. Bonaparte contributed to the birth of democratic nations and states where they did not exist, such as in Poland, Italy, and Germany. He forced the transformation, albeit against his will, of ultra-reactionary states such as Prussia, in such a way that the vast coalition movement that was to prevail was in some ways his child.

— Antoine Casanova

Our ancestors began to act and, as we have seen, for the first time in a conscious and organized way. Napoleon said of the peasant masses that they were “ignorant but intelligent”. We must understand the reasons for such a paroxysm in the social and political struggles, in the civil and foreign war.

— Antoine Casanova

Sans-Culottes in the cities and countryside discovered the contradictions of a society where the figure of the “citizen” was now fading behind that of the “bourgeois”. But royalist upheavals, seen as an intolerable concession to the Ancien Régime, were treated with equal vigor. The army was called in, and in particular Bonaparte, nicknamed “General Vendémiaire” at the time, to put down the royalist uprising of October 5, 1795. Two years later, part of the Directory did not hesitate to resort to a coup d'état to eliminate the monarchist right.

— Claude Mazauric

[The Civil Code] establishes, in all areas of human life, a spirit of law which is that of the new society. The careful study of the long preparatory sessions leading up to the drafting of the law would illuminatingly show through the debates and discussions that went into the process of defining the relationships between people in all areas, in terms of a contract. I will only give a brief example here. It is the discussion between Portalis and Bonaparte on divorce, one hostile to this new procedure, the other favorable to “mutual consent”.

“Marriage is not a social pact but a fact,” says Portalis. “It is the result of nature which destines men to live in society.” To which Bonaparte responds, masterfully: “Marriage takes its form from the morals, customs, religion of each people. It is for this reason that it is not the same everywhere. There are countries where wives and concubines live under the same roof, where slaves are treated like children. The organization of families therefore does not derive from natural law...”

This transformation of morals and the resulting refinement of sensitivities lead to a new conception of the human being seen henceforth as an individual existing concretely in society.

— Antoine Casanova

From year V (1797), a revival began to occur on new foundations. Despite the war, it continued until 1809. This was the first phase in France's industrialization, anticipating that which would begin in 1825. It was a real start.

Admittedly, the production levels of 1789 were not reached, mainly because sectors that had been held at arm’s length in 1793 and 1794 were abandoned, but the rate of growth in productivity and industrial establishment corresponded to the expectations of the bourgeoisie since the start of the Revolution. This was the period when the ci-devant Comte de Saint-Simon, who would later become the great thinker we know, launched a public transport company in Paris “by horse-drawn omnibuses”. The press also began to advertise goods in a modern way. The countryside was also equipped. With the abolition of feudal rights, the head of a peasant family now has an additional ten to fifteen percent of gross income, taxes paid. Farm plots expanded, as did communal areas. Better use is made of more efficient tools. Wages improve. A great deal of construction is taking place. Many of the fine homes still dotting the French countryside date from this Directory and Consulate era. In short, overall, and especially among the “haves”, life was better.

The continuation of the war, the defeat of 1814-1815 and the return to power of the landowners brought this development to a temporary halt. But the new momentum of the first years of the 19th century is undeniable.

— Claude Mazauric

But it nonetheless remains true that this era is that of a compromise which, against the aristocracy, ensures the hegemony of a republican bourgeoisie governing with the consensus of owners small and large and therefore of a very broad part of the popular strata. We can clearly see the transformations brought about by the Revolution. Certainly, there were splits, political oscillations and perpetual instability, which meant that this period was experienced as “the time of coups d'état”. But this did not mean that France was dictated to by a minority.

Ultimately, the military will play a big role in maintaining this compromise. An army that should not be seen in the image of what it will become in the following century. Its soldiers and cadres, who came from it, saved the Revolution. They bore the brunt of the struggle against the aristocracy. It is from her that “the good sword” will emerge, as Sieyès said, the man capable of putting an end to the dangerous political instability of the post-Thermidor period, with the agreement of the notables and the popular masses. And this man, on 18 Brumaire, was Bonaparte, a Bonaparte who always knew how to distinguish, as he put it, “between the ideology of the Revolution and the deep interests of this Revolution” and who proclaimed: “Citizens! The Revolution is fixed on the principles which began it. It is finished!”

— Antoine Casanova

#Claude Mazauric#Antoine Casanova#Vive la Révolution: 1789-1989: Réflexions autour du bicentenaire#Vive la Révolution: 1789-1989#history#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#19th century#france#Marxist historians#marxisms#Mazauric#Casanova#french revolution#french history#writers and Napoleon

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

We need to actually take action against the ruling class sitting idly by while they actively take advantage and run the oligarchy they’ve created changes nothing

#punk#fuck the republikkkans#I actually hate the ruling class so much#our current wealth gap is larger than during the French Revolution#we need action#marxism#im tweaking#im personally an anarcho-syndiclist

39K notes

·

View notes