#even if intrinsically they may be questioning of some of these values they still reproduce them

Text

like if I think abt it for too long I do get frustrated at how vibrant rpf m/m sports communities are. In no means am I saying no men in these sports have ever been queer in any way but it is insaaane to look at the institutions upholding the most concentrated and idealised form of hegemonic masculinity (a masculinity that inherently disempowers and devalues women, feminine traits, and homosexuality) and say. Yknow what. I bet these men are fucking.

#and I reckon it’s bc it’s a way of coping for female fans . bc it’s hard to acknowledge that these men probably don’t value women that much#like hegemonic masculinity is a complex topic and I’m not saying every male athlete is bound by it.#by they do represent the PEAK of that expectation within society#you either conform or you do not make it into those sports at the professional level#even if intrinsically they may be questioning of some of these values they still reproduce them#again. even if a footballler or f/1 driver were gay they all still have gfs and treat them as props.#reproducing and performing hegemonic masculinity#it’s all a performance anyway so how are they immune to criticism of their role in it ?#sorry idk where I’m going with this but isn’t it a crazy level of revisionism and coping and . wilful ignorance#to ignore these dynamics for the sake of ships and fanfic

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I. van Hilvoorde and L. Landeweerd, Enhancing disabilities: transhumanism under the veil of inclusion?, 32 Disability & Rehabilitation 2222 (2010)

Abstract

Technological developments for disabled athletes may facilitate their competition in standard elite sports. They raise intriguing philosophical questions that challenge dominant notions of body and normality. The case of ‘bladerunner’ Oscar Pistorius in particular is used to illustrate and defend ‘transhumanist’ ideologies that promote the use of technology to extend human capabilities. Some argue that new technologies will undermine the sharp contrast between the athlete as a cultural hero and icon and the disabled person that needs extra attention or care; the one exemplary of the peak of normality, human functioning at its best, the other representing a way of coping with the opposite.

Do current ways of classification do justice to the performances of disabled athletes? The case of Oscar Pistorius will be used to further illustrate the complexities of these questions, in particular when related to notions of normality and extraordinary performances. Pistorius’ desire to become part of ‘normal’ elite sport may be interpreted as an expression of a right to ‘inclusion’ or ‘integration’, but at the same time it reproduces new inequalities and asymmetries between performances of able and dis-abled athletes: we propose that if one accepts that Pistorius should compete in the ‘regular’ Olympic Games, this would paradoxically underline the differences between able and disabled and it would reproduce the current order and hierarchy between able and disabled bodies.

Introduction

There is a growing academic interest in issues that relate to sports, disability and classification [1–3]. Academics from a variety of disciplines deal with questions like: ‘Can we objectively classify human beings in sport?’, ‘Should health and disability be defined in objective or contextual terms?’ [4,5]. ‘How does the ideology of normalcy relate to elite sport?’ [6]. These questions arise from a broader philosophical debate on ‘performativity’, the theoretical notion that disability is ‘performed’ instead of a static fact of the body [7,8]. They are nourished by a more general debate on disability and theories of social justice [9,10]. The case of South African sprinter Oscar Pistorius, also known as ‘the fastest man on no legs’, has particularly stimulated the academic interest from a variety of disciplines [11–18].

Pistorius is an outstanding athlete, who had the desire to compete at the Olympic Games. Running with carbon-fibre legs he is world record holder in the 100, 200 and 400 m and can even compete with elite athletes on ‘natural legs’. His desire to participate in a regular competition is surrounded by controversy and raises a variety of both empirical and (sport) philosophical questions dealing with the concepts of dis-ability, super-ability, enhancement and a fair competition. It is clear that Pistorius challenges our understanding of disability and that his case contributes to the blurring of some traditional boundaries. New technological artefacts such as innovative prostheses apparently help to turn ‘disabled’ people into ‘normal’ subjects.

What may be considered ‘normalisation’ in the context of daily life is at least ambivalent in the context of elite sport. Running on prostheses may be defined as an intrinsic aspect of the talent that is tested in a competition against ‘relevant others’: athletes who have the ability to show a similar talent. Pistorius is still officially classified as ‘disabled’, but this classification may not be relevant anymore if one abandons the criterion of species-typical functioning in favour of a contextual approach, an approach that looks at how the socio-cultural context of a certain trait is relevant for this traits definition [18].

In daily life, there is little reason to qualify people who integrate their prostheses into their ‘lived bodies’ as impaired. The demarcation between sport for the ‘normal’ and sport for the ‘abnormal’ rather demonstrates aspects of our understanding of what is and what should be considered a ‘normal athletic body’. Disabled athletes are literally constructed as such in the context of the culturally robust demarcation between Olympic Games and Paralympic Games. As is the case with other performance enhancing methods, the Olympic competition becomes a mechanism for evaluating athletes with a ‘normal biological body’ [19]. If Pistorius’ label as dis-abled does not relate to his body image and way of life in a non-sports context, what does this mean for the construction of a boundary between ability sports and disability sports? Are there valid arguments to exclude him from running against able bodied athletes? And how does this discussion relate to the general discussion on classification? We will attempt to answer these intriguing questions against the background of the discussion on the definitions of and demarcations between normalcy and disability and against the background of current discussions on ‘transhumanism’.

Being disabled as the norm for humanity

In the theoretical framework of the philosopher John Rawls, those who are at the same level of talent and ability, and have the same willingness to use them, should have the same prospects of success regardless of their initial place in the social system [20]. Social class, gender or any other contingency should have no influence on the liberty individuals are to enjoy in the pursuance of their goals in life. Moreover, social and economic benefits should be distributed in such a way that they can reasonably be expected to be advantageous to all those who are worst off in the first place. Rawls aimed at this distributive justice (thus termed by him) to compensate for the differences in fortune that affect our lives. Justice is seen as being independent of luck and favouring a more equal distribution of harms and benefits. This idea is still often taken to be the basis for how we deal with issues surrounding the social inclusion of the disabled [1–3].

People with impairments of any kind cannot partake in society (and sport) as fully as they should, according to the principles of distributive justice. The principles of distributive justice therefore demand that we redesign the world around us to make it more accessible for everybody. This necessitates an answer to the question what obstacles can and should be taken away in order for the persons with disabilities to become part of other spheres of life. Making a public building accessible for the disabled is one but making elite sport accessible to them is another. Elite sport is, by definition, constructed around the notions of differentiation, categorisation and selection, all with the cause of showing ‘virtuosity’, ‘supremacy’ and ‘super-humanness’. Our dominant understanding of elite sport cannot be brought in agreement with some type of right to become an elite athlete on the basis of a right to a context in which all starting positions are equal. This is different from the right, for example, to receive good education. If one defines normalcy as average, excellence, by definition, excludes normalcy.

Differences between performances of able and disabled athletes can not be inferred from a definition of ‘the normal’. Modern elite sport celebrates abnormalities in many shapes and appearances, varying from extreme sized sumo wrestlers to extremely undersized gymnasts. In this light, it becomes difficult to justify the difference in admiration for the elite athlete and the impaired athlete with recourse only to concepts such as ‘talent’ or ‘effort’. Some talents are more valued in a society than others, in spite of a changing terminology that sometimes even seems to suggest that being disabled is an occasional experience of each human being.

If one were to grant a disabled person’s desire to become part of ‘normal’ elite sport by enhancing one or more aspects of his body, this may be framed as a way of ‘inclusion’ or ‘integration’. At the same time, this reproduces new inequalities and asymmetries between performances of the able and dis-abled bodied. To enhance the traits needed to function optimally in a society, is to take that society as the proper standard against which the functioning of people is legitimately judged. Enhancement of specific traits may count as justice through social inclusion but one could also defend that a just society is one in which people are not forced to conform and are not measured by a single yardstick. In that case, the yardstick itself should not be seen as neutral: it appears to be politically biased. When one defines what counts as a handicap in a contextual rather than a descriptive fashion, the notion of disability becomes political.

In contemporary (Western) society, social arrangements are based on the aim to provide people with the same starting position in life. Abnormalities that render this starting position inferior are therefore to be compensated. In many respects, the ideal of the elite sportsman has all characteristics of abnormality as well. However, in contrast to the physically or mentally challenged, the elite sportsman is not considered to be subject to societies’ assignment to normalise people’s starting positions. How ‘extreme’ and ‘beyond normal’ the elite athletes bodies and outstanding performances may be, they are still considered as cultural heroes, icons and even as examples for the average human being (even whilst some characteristics of elite athletes’ bodies may pose a handicap in daily life).

Elite sport is about excellence within the boundaries of ‘self-chosen’ limitations; disability sports originated from limitations through fate. Elite sport symbolises the athlete as hero; it reproduces elitist ideals about the (‘athletic’ and ‘beautiful’) body, about good sportsmanship and national pride. For many people, in disability sport, the athlete is still a ‘patient combating his limitations’, instead of an elite athlete with specific and outstanding talents.

The case of Pistorius holds a dichotomous con- sequence for the debate on equality and disability rights in sport. Pistorius’ not unrealistic desire to participate in the regular Olympics is illustrative of how technological progress and changes in definition blur the distinction between able and disabled, therefore contributing to the emancipation of the disabled. But his case may also contribute to an increased inequality, between those that are technologically ‘enhanced’ and those that are not.

Transhumanists look upon the case of Pistorius with excited interest, since Pistorius can be used as an icon for technological progress just as easily as for equality rights for the disabled. As Camporesi [12] states:

‘His [Pistorius] case is a snap-shot into the future of sport. It is plausible to think that in 50 years, or maybe less, the ‘‘natural’’, able-bodied athletes will just appear anachronistic. As our concept of what is ‘‘natural’’ depends on what we are used to, and evolves with our society and culture, so does our concept of ‘‘purity’’ of sport, and our concept of how an Olympics athlete should look.’

Transhumanism is a movement that seeks to advance technology in such a way that it would alter the human condition to something to which the term human may no longer be applicable. It seeks to achieve this through the means of genetic engineer- ing, artificial intelligence, robotics, nanotechnology, virtual reality, etc. [21]. The problem with transhumanism is that in its desire to improve upon mankind, it may lead to an increase in the division between the ‘tech-rich’ and the ‘tech-poor’. Although Pistorius has no transhumanist aspirations, his case could be seen a first step towards the transhumanist dream of a post-humanity. Apparently, Pistorius’ case can be brought forward in support of equality between able and disabled, but it may also amount to an inadvertent support of transhumanism. When posited in support of trans- humanism, his case may lead to an increase rather than a decrease of equality.

The ideology of the ICF versus the logic of sports

The ambiguity of Oscar Pistorius’ status as either a ‘dis’-abled, ‘abled’, or even ‘super’-abled sportsman carries along some interesting consequences for both the classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps and the classification of disabilities sports and elite sports. The ‘International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps’ (ICIDH) has been replaced by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) at the start of this century [22]. In general, this change of terminology reflects a shift in focus from disabilities to abilities and capacities. Disability is not regarded a characteristic (that is present all the time) but a state that may be present in certain environments or results from specific interactions with other people. With this change, the concept of health changed from a bio-statistical (‘objective’) conception to a more contextual conception. Being disabled is no longer considered as something one is by definition (‘by its nature’), but something one becomes in relation to specific environments [23]. Disabilities are socio-cultural constructions rather than natural kinds or given states of being. People can become disabled by their environment or by specific (lack of) technologies. A person with an average intellectual ability may ‘become’ less able in an environment consisting of highly gifted people. An elite athlete who chooses not to use performance-enhancing substances may become ‘dis-abled’ in a context in which the use of doping is ‘normalised’.

There is still an active discussion on the value of the ICF. Critics argue that it still leads to a desire to classify individuals according to disabilities. The philosopher of health, Lennart Nordenfelt, wrote a critical article on the ICF in this journal in 2006. Nordenfelt stated that

‘The will is a crucial notion in all action theory. But the will is quite absent in the theory of the ICF. [ . . . ] Ability and opportunity are not sufficient for the performance of an action . . . one must first intend to act or want to act’ [24]. According to this ability-centered theory of health, the ability of health should be related to the realization of the person’s vital goals: ‘The ultimate goal should be to enable the individual and give him or her opportunities to participate in the way and to the extent he or she wants and chooses to participate’ [25].

What about the vital goals of Oscar Pistorius? Although this debate on the value of the ICF focused on the goals of rehabilitation, this case illustrates the rather subject-oriented position of Nordenfelt. As has been put forward by Reinhardt et al. [26] in their response to Nordenfelt, the will of an individual, how he or she wants and chooses to participate is, not in the least in the context of elite sports, highly restricted by social, political and ideological circumstances. Moreover, classification is a sport specific process and of major importance in all sports. Handicaps are artificially constructed and defined. Being a woman is seen as a sport specific ‘handicap’, otherwise they would be performing together with men. Being small and light is a handicap in boxing and wrestling compared to bigger and heavier athletes. Participation is not based upon an ideology of ‘inclusion’ and ‘sameness’, but based upon differences in talent, classified on the basis of relevant inequalities.

There is a clear friction between Pistorius’ qualification as ‘super-abled’ and his vital goals that are based upon an alternative understanding of normality and ability. Most of the empirical studies on this subject support this label of ‘super-ability’. Much of the academic debate did not so much deal with his vital goals, but rather with the empirical question how his achievements have been influenced by his artificial legs, therefore not centering on whether Pistorius should be classified as a disabled sportsman, but on whether he should be disqualified as having an unfair advantage. Based on a study by the Institute of Biomechanics and Orthopaedics (German Sport University, Cologne), the IAAF concluded that an athlete running with prosthetic blades has a clear mechanical advantage (more than 30%) over someone not using blades. Pistorius responded to this challenge that his prosthetics also confront him with disadvantages, such as the fact that he uses more energy at the start of the race than other runners. Recent findings suggest that running on lower-limb sprinting prostheses is physiologically similar to intact-limb elite running (measured in mean gross metabolic cost of transport), but mechanically different (longer foot-ground contact, shorter aerial and swing times and lower stance-averaged vertical forces) [11,17].

Even if there is evidence that running with prosthetics needs less additional energy than running with natural limbs, this in itself would be an insufficient argument to keep Pistorius from competiing in the Olympics. There is no standard test available to judge different bionic legs and compare them with ‘normal’ legs’ [18]. Besides, ‘if there is any reason to believe that Pistorius’s prostheses afford him some degree of unfair advantage [ . . . ] then surely there has been a similar, nay greater, risk of unfair advantage in all of his paralympic competing up to the present’ [16]. Categories within disability sports are much fuzzier and more variation in the quality of technology (such as prosthetic limbs) is accepted within disability sports, which provides unfair advantages for some of the athletes. But these unfair advantages within the Paralympic Games do not seem to be such a high concern by the International Athletic Federation.

The ideology mirrored by the ICF conflicts with the discussion on classification within disability sports, with respect to diverging perspectives on the meaning of obstacles. Although the ICF aims at the removal of obstacles (to minimalise any disability), and Nordenfelt adds to that the will to overcome obstacles, sport is however defined by a voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles [27]. Sport is about creating ‘artificial dis-abilities’, not about taking them away.

Prostheses not necessarily define Pistorius as ‘dis- abled’. On the basis of a definition of his abilities there is no good argument to exclude Pistorius from the Olympic Games. Prostheses are however part of the definition of the game. The question if Pistorius should be labelled as either super- or dis-abled is not that relevant for his in- or exclusion. More relevant is the question what kind of a game is he playing. The question how to define a game deals with criteria for the relevant athletic performance. The standards of excellence for each specific sport are based upon judgements that are informed by scientific, conceptual and ethical evidence [15]. The questions for example if ‘klapskates’ could officially become part of the game of long track speed skating, if Fosbury’s masterful redefinition of high jumping was within the rules of the game are conceptual matters of definition and sport ethical analysis (grounded in notions of fairness and safety) [28]. If re-skilling a technique is necessary as a result of such redefinitions, than accessibility of new technology is crucial. The athletic edge that is gained should always be attributed to someone’s own athletic skills, and not on the basis of an unequal distribution of means and superior technology.

In dealing with such issues of fairness and definition in sport, the process of decision making also remains crucial. Who is eligible to make informed decisions about the rules and definition of the game and on what grounds? These informed decisions can be made by a broad practice commu- nity that have an interest in the quality of the game itself (such as athletes, coaches, officials, scientists), that are highly knowledgeable on the sport, but without apparent (commercial or athletic) interest in a certain outcome of the decision process. Manufactures (and sponsors) of high-tech swimming suits eventually harmed the game of swimming when they had too much control on the rules. This was more or less corrected by the community of swimming itself. Similarly, it is clear that manufacturers of prostheses should not be involved in defining the rules of disability sports, unless they are clearly involved in organising an equal distribution of technological means for each specific category of disability.

Disability sports are about showing performances within categories of similar disabilities, without making those disabilities the central element of athletic prowess. Running on prostheses may be defined as crucial for the specific talent that is tested in a competition against ‘relevant others’: athletes who have the ability to show a similar talent. The advantages of a prosthesis in this case bear upon the ‘relevant inequalities’ of the sport. Pistorius is not playing the same game as his opponents because he is showing another and extra skill, namely handling his prosthesis in an extremely talented way.

At first sight it seems that the inclusion of Pistorius in the Olympic Games is in accordance with the ideology behind the ICF and in accordance with the realization of his vital goals [5]. It could be argued that the case of Pistorius blurs the distinction between elite sports and the disabled sports. His ‘promotion’ to the elite level of sport may be considered as a form of empowerment and a symbol for non-discrimination. On the other hand, one can foresee a new boundary between disabled people into two categories: first the invalid, dependent and incapacitated and second ‘that much celebrated media persona of the disabled person who has ‘overcome adversity’ in a heartwarming manner and not been restricted by his or her ‘flaws’, but believes that ‘everything is possible’ for those who work hard’ [16]. Of the limited available ‘scripts of disability’ [7], the ‘inspirational overcomer’ dominates the image of the heroic disabled athlete. The blind runner Marla Runyan received much less attention for the five gold medals that she won in the Paralympics of 1992 and 1996, but really became famous when she competed in the ‘normal Olympics’ in 2000, and finished 8th in the 1500 m. This difference in status confirms the idea that ‘overcoming a disability’ seems a more out- standing performance than winning gold in the Paralympic Games. But when a disability can be compensated in such a way that the compensation provides for a ‘super’-ability in a specific context, compensating for a disability may prove to be a step beyond ‘normal’ humanity or even a step towards ‘transgressing’ humanity.

The case of Pistorius (and more will follow) stimulates the ideology of transhumanism, and the transhumanization of ableism: ‘the set of beliefs, processes and practices that perceive the ‘‘improvement’’ of human body abilities beyond typical Homo sapiens boundaries as essential’ [19]. What is perceived of as ‘better’, as ‘enhancement’ and what not, however, is up for dispute. If there is no neutral ground on which to define normalcy and ‘super’-ability, any attempt at ‘going beyond’ normal functioning necessarily is politics disguised as science. Transhumanism therefore is an ideological project. It is the paradox of Oscar Pistorius that he could develop into a symbol for the ‘normalization of dis-abilities’, but at the same time into a symbol of a neo-liberal ideology in which specific talents of the individual ‘superhuman’ and ‘inspirational overcomer’ [7] are put on the stage as an heroic example. Pistorius may become a symbol for both a concept of equality through a justice of social inclusion and for a concept of inequality through enhancement towards a form of ‘super’- humanism.

Conclusion

On the one hand, society invests quite willingly in the super-abilities of the elite athlete whilst on the other it only does this reluctantly, and from an ethics of inclusion, with respect to the disabled. In the case of disabilities, one wants to eradicate abnormalities by equalising on the basis of ‘sameness’, while in the case of super-abilities we support abnormalities. This ‘selective investment in the abnormal’ and the admiration for the ‘genetically superior’ could be seen as a token of a society that cannot meet up with the criteria for justice [10]. On the other hand, sport is a competitive practice, whose internal logic consists of the display of an unequal distribution of abilities and talents.

There are good arguments for a radical change of the organisation and classification of traditional sports and for the need of a critical rethinking of the traditional boundary between Olympic Games and Paralympic Games. A more successful application of the notion ‘distributive justice’ would call for a change of the organisation and classification of traditional sports. Starting from a more liberal definition of categories one can also imagine the organisation of competitions that are not contrasted on the basis of an opposition between able and dis-able, but rather around the equal distribution and accessibility of new technology (including prostheses).

The claim that Pistorius has the right to compete directly against non-disabled athletes in Olympic events does not appear to be a strong claim. A stronger claim can be made for a separate bionic track event to be part of the Olympics. This however needs consistent rules on technical aids as well as an equal and standardised access to new technology. The inclusion of just one (‘Paralympic’) event will also create new inequalities and asymmetries between performances of able and dis-abled athletes. Pistorius’ wish to become part of ‘normal’ elite sport may be framed as a way of ‘inclusion’ or ‘integration’, but paradoxically underlines the differences and reproduces the current order and hierarchy between able and disabled bodies.

References

DePauw KP, Gavron SJ. Disability sport. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2005.

Doll-Tepper G, Kroner M, Sonnenschein W. New horizons in sport for athletes with a disability. Aachen: Meyer & Meyer Sport; 2001.

Vanlandewijck YC, Chappel R. Integration and classification issues in competitive sport for athletes with disabilities. Sport Sci Rev 1996;5:65–88.

Cox-White B, Flavia Boxall S. Redefining disability: maleficent, unjust and inconsistent. J Med Philos 2009;33:558–576.

Harris J. Is there a coherent social conception of disability? J Med Ethics 2000;26:95–100.

Koch T. The ideology of normalcy: the ethics of difference.J Disabil Policy Studies 2005;16:123–129.

Sandahl C, Auslander P, editors. Bodies in commotion; disability and performance. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press; 2005.

Corker M, Shakespeare T, editors. Disability/postmodernity: embodying disability theory. Continuum International; 2002.

Pickering Francis L. Competitive sports, disability, and problems of justice in sports. J Philos Sport 2005;32:127–132.

Nussbaum M. Frontiers of justice: disability, nationality, species membership. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University; 2006.

Bruggeman GP, Arampatzis A, Emrich F, Potthast W. Biomechanics of double transtibial amputee sprinting using dedicated sprint prostheses. Sports Technol 2009;4–5:220–227.

Camporesi S. Oscar Pistorius, enhancement and post-humans. J Med Ethics 2008;34:639.

Edwards SD. Should Oscar Pistorius be excluded from the 2008 Olympic Games. Sport Ethics Philos 2008;2:112–125.

Hilvoorde I, van & Landeweerd L. Disability or extraordinary talent; Francesco Lentini (3 legs) versus Oscar Pistorius (no legs). Sport, Ethics & Philosophy 2008;2:97–111.

Jones C, Wilson C. Defining advantage and athletic performance: the case of Oscar Pistorius. Eur J Sport Sci 2009;9:125–131.

Swartz L, Watermeyer B. Cyborg anxiety: Oscar Pistorius and the boundaries of what it means to be human. Disabil Soc 2008;23:187–190

Weyand PG, Bundle MW, McGowan CP, Grabowski A, Brown MB, Kram R, Herr H. The fastest runner on artificial legs: different limbs, similar function? J Appl Physiol 2009;107:903–911.

Wolbring G. Oscar Pistorius and the future nature of olympic, paralympic and other sports. ScriptEd 2008;5:139–160.

Wolbring G. One world, one Olympics: governing human ability, ableism and disablism in an era of bodily enhancements. In: Miah S, Stubbs, editors. Human futures: art in an age of uncertainty. FACT and Liverpool University Press; 2009.

Rawls J. A theory of justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1971.

Bostrom N. The Transhumanist FAQ: a general introduction (Version 2.1). 2003. http://www.transhumanism.org/resources/FAQv21.pdf (last accessed 12 January 2005).

IPC. Athletics Classification Handbook. 2006.

Moser I. Disability and the promises of technology: technology, subjectivity and embodiment within an order of the normal. Inform Commun Soc 2006;9:373–95.

Nordenfelt L. On health, ability and activity: comments on some basic notions in the ICF. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:1461–1465.

Nordenfelt L. Reply to the commentaries. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:1487–1489.

Reinhardt JD, Cieza A, Stamm T, Stucki G. Commentary on Nordenfelt’s ‘On Health, ability and activity: comments on some basis notions in the ICF’’. Disabil Rehabil 2006;28: 1483–1485.

Suits B. The grasshopper. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1978/2005.

Hilvoorde I, van Vos R, Wert GD. Flopping, klapping and gene doping; dichotomies between ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ in elite sport. Social Stud Sci 2007;37:173–200.

#disability#sports#ethics#classification#enhancement#technology#transhumanism#prostheses#oscar pistorius#medical model of disability#human enhancement#social model of disability#ethics in sport#normativity

1 note

·

View note

Text

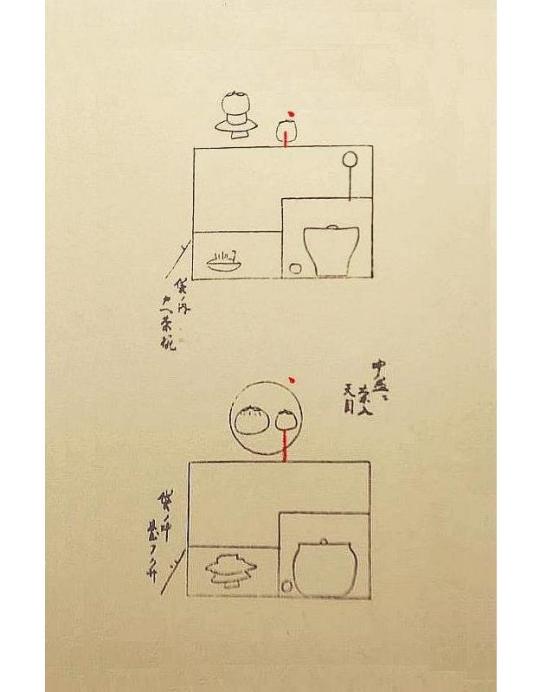

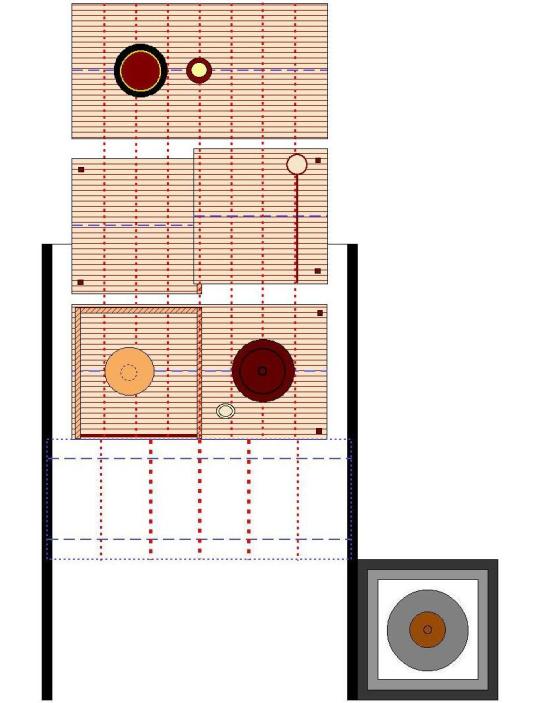

Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.8): Two Arrangements for a Karamono-chaire and a Dai-temmoku on the Fukuro-dana.

18.8) Two arrangements for a karamono-chaire¹ and a dai-temmoku² on the fukuro-dana.

[The writing reads: (to the left of the upper sketch) fukuro no uchi kae-chawan³ (袋ノ内 カヘ茶碗); (above the lower sketch⁴) naka-bon⁵ ni chaire ・ temmoku (中盆ニ 茶入・天目), (to the left of the lower sketch) fukuro no uchi dai⁶ ・ fukusa⁷ (袋ノ中 臺・フクサ).]

_________________________

¹These are “ordinary” karamono-chaire*, pieces that do not merit mine-suri [峰摺���] placement. As such, while resting on their kane, they are placed very slightly off center -- this is what the pictorial orientation is intended to suggest.

___________

*According to his densho of 1582 or 1583 (the surviving manuscript is undated, but it must postdate the creation of the tsuri-dana [釣棚] during the summer of 1582), Rikyū would probably have included the old Seto chaire -- the pieces made under the direction of the chajin arriving in Japan from the continent during the fifteenth century -- in this proposal.

²While the temmoku was most likely also an imported piece (though the rare Japanese-made temmoku were often technically identical, and generally handled in the same manner -- frequently not being distinguished from the imported pieces*), the chawan was felt to be intrinsically inferior to the chaire†, hence its usual arrangement in a slightly inferior manner.

___________

*Rikyū’s ake-temmoku [赤天目] (shown below) is a good example.

While it is unclear what he actually believed regarding its antecedents, he handled it and used it in the same way as a karamono-temmoku.

Furthermore, in the Yamanoue Sōji Ki [山上宗二記], the white temmoku (which were made for Jōō at the Seto kiln) are ranked highest, above all of the imported bowls. This suggests that, rather than simply being a manifestation of the mindset that favored continental pieces over local wares, the preference for imported chaire was due to their technical superiority to the pieces that were being made by the local potters. (Of course, this attitude underwent a change in the Edo period, when imported pieces were valued simply because they were imported.)

†While a chaire was felt to improve with repeated use (as the aromatic elements in the matcha work their way into the clay), chawan were originally used only until they began to exhibit signs of “contamination” -- for example, the crackles in the glaze becoming stained with tea -- and then replaced. The lack of crackles in the glaze on the Chinese temmoku may have been the reason why they stayed in use much longer than others.

While this idea started to weaken once chawan began to be recognized as meibutsu objects that were deserving of preservation -- which attitude was reinforced by Jōō’s own approach of amassing a large collection of such pieces -- their inferior status vis-à-vis the chaire continued to be a feature of chanoyu in Jōō’s day (as it remains today).

³Kae-chawan [カヘ茶碗].

The term kae-chawan [替茶碗] refers to a “substitute chawan” used to bring the chakin and chasen (and sometimes the chashaku, as in this case) into the room at the beginning of the temae, and which was used to clean the chasen at the end of the temae, using cold water (in order to protect the temmoku from being soiled by this process). It was not (necessarily) used to serve tea -- though this idea was being questioned more and more by the chajin of Jōō’s period (when the kae-chawan was often being used to serve usucha -- a practice that enhanced the temmoku’s status).⁴

⁴There is a critical issue -- apparently a copying error -- with this illustration, as it appears in the Enkaku-ji manuscript of the Nampō Roku. In Tachibana Jitsuzan’s original sketch (which is the version that has been reproduced here) -- the sketch he made with the Shū-un-an documents spread out in front of him* -- a futaoki is shown on the lower shelf, next to the mizusashi. Jitsuzan, however, apparently neglected to include the futaoki in the sketch that was prepared for the Enkaku-ji manuscript†. The futaoki, then, is absent from all of the sketches that were later based on the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

This is extremely important, since the presence (or absence) of the futaoki impacts on the kane-wari interpretation of the arrangement -- and its absence here has resulted in very confusing speculations (by certain commentators) regarding the way that the utensils arranged on the tray should be counted‡.

It would have been very easy to remove the futaoki from the sketch digitally, and so make it more closely resemble that in the Enkaku-ji version of this document. But since its absence there is obviously a mistake (without the futaoki it becomes impossible to rationalize the kane-wari for the goza), I felt it was best to leave the futaoki in the sketch, even though that means that I am no longer showing a likeness of what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript (which is the teihon [底本] on which this translation is supposed to be based).

___________

*We must assume that, regardless of the temporal constraints under which Jitsuzan was working (as has been mentioned before, he was only given access to the Shū-un-an documents for a limited period of time), the original sketches that he made with the Shū-un-an documents spread out in front of him necessarily would have had to closely resemble the documents that he was copying, especially in details such as this (otherwise he would surely have edited them on the spot -- since his purpose was to make a copy of the originals for his own reference and study: the idea of proselytizing the resulting material does not seem to have occurred to him until later). Thus, the accuracy of the first manuscript must take precedence over the copy that he made several years later. (Jitsuzan seems to have requested accessed the original documents in 1586, after examining a copy of the Rikyū Chanoyu Sho [利休茶湯書], while on his way from Kyūshū to Edo in observation of the sankin-kōtai [參勤交代], or “alternate attendance,” rule; meanwhile, the presentation copy for the Enkaku-ji was prepared between 1689 and 1690. The Rikyū Chanoyu Sho [利休茶湯書] was translated, in its entirety, previously in this blog.)

†A futaoki is not displayed on the ji-ita in several of the subsequent arrangements -- because it is placed somewhere else (or its absence plays into the correct count, so far as kane-wari is concerned). It seems that Jitsuzan may have looked ahead to the next page of sketches, and so overlooked its presence in this sketch.

‡The objects arranged on the tray are all counted as a single unit, since the tray itself contacts all of the kane with which those utensils are associated individually. Nevertheless, with the futaoki absent, this has lead some interpreters to argue that the objects arranged on the ten-ita should be counted as if the tray were not present at all. The result is a lingering confusion that taints their understanding of the rest of the Nampō Roku.

⁵Naka-bon [中盆].

As in the previous post, this is usually taken as a reference to the (meibutsu) naka-maru-bon [中丸盆], which measures 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter.

There was, as Shibayama Fugen points out, also a hō-bon [方盆]* version (which measured 1-shaku square).

Round trays, however, were considered less formal -- making them more appropriate to the setting. Regardless of which tray was used, the fukuro-dana would still have been placed 1-shaku 2-sun away from the upper corner of the ro.

___________

*Hō-bon [方盆] means a square (or sometimes rectangular) tray. The word shi-hō-bon [四方盆], literally meaning a “square tray,” does not seem to have been used that commonly in Jōō’s period.

The 1-shaku square tray was not one of the Higashiyama gomotsu [東山御物] that were used by Ashikaga Yoshimasa, as was the naka-maru-bon; the square tray was first introduced by the early machi-shū practitioners, the mostly immigrant-chajin of Shukō’s generation.

The square naka-bon will appear in the next post.

⁶Dai [臺].

The temmoku-dai [天目臺].

In Jōō’s period (and before) these were either plain black-lacquered dai that had been imported from the continent* (a typical example is shown below), or (much less frequently) Japanese-made copies.

The reason the dai is placed in the ji-fukuro has nothing to do with its quality or antecedents. Rather, it is because the naka-maru-bon is the largest tray that could be used with the fukuro-dana†, and this tray is not sufficiently large to allow the temmoku to be displayed on its dai together with the chaire.

___________

*In China, these dai were used to hold the conical bowls in which heated sake was served in restaurant and drinking establishments (this is why many of them were painted with the marks of the houses from which they came -- so that they could be claimed by their rightful owners later: the Chinese, then, as now, delighted in having meals catered, and since this often involved different things being sent from several establishments, correctly sorting the dishes afterward became an issue) -- the sake was usually flavored with medicinal herbs, and the conical shape allowed the dregs to settle to the bottom, so they would not discommode the drinker. While quite commonplace objects on the continent, these dai became great treasures in Japan -- an almost worshipful attitude that was certainly helped by the trade embargo that followed the overthrow of the Koryeo dynasty (in the first years of the fifteenth century), and the establishment of the Josen tributary state (in the middle of the fifteenth century) under a Ming hegemony.

†The meibutsu nagabon that were typically used with the daisu when the host wished to display both the chawan and the chaire on a tray were not used with the fukuro-dana, since Jōō felt that these trays were too formal for the setting. Jōō selected the most informal arrangements for the daisu and elevated them to the highest rank in this new setting.

⁷Fukusa [フクサ].

This would be the host‘s temae-fukusa. While there were different ways it could be placed on the dai (the purpose being to cover the hole into which the foot of the chawan would fit), the simplest way was to fold the fukusa into quarters and rest it on top of the dai (with the corner that the host would need to grasp, to lift the cloth up and fold it, on the right), as shown in my sketch (below).

While I have colored the fukusa purple (and made it the size of a modern-day fukusa so that the hane of the dai will be visible -- these sketches are always carefully drawn to scale), for clarity, this is an anachronism. In Jōō’s period, the host’s temae-fukusa was always made of imported donsu, usually in a color scheme favored by the host (or, perhaps, his economics -- since the fukusa was used only once and then discarded, and cloth woven in unpopular colors was naturally cheaper), and they were generally slightly over 1-shaku square (meaning that the hane of the temmoku-dai would probably not peak out from underneath the fukusa, even by a little).

The first purple “fukusa” measuring 8-sun by 8-sun 2-bu were originally not made to be fukusa, but as small furoshiki (wrapping cloths)* in which lacquered containers of matcha were tied before being enclosed in a sa-tsū-bako [茶通箱] (for presentation as a gift to someone). The first time this kind of cloth was used as a temae-fukusa was on an occasion when Furuta Sōshitsu received a sa-tsū-bako of tea from Hideyoshi (forwarded to him by Rikyū, probably so that its arrival would coincide with the gathering). Since Oribe was already in the tearoom when the gift tea arrived, and had apparently not been expecting it, he had not prepared a second fukusa (the host’s futokoro is usually stuffed with so many things that a random fukusa would easily get lost, especially when the host was not expecting to use it, so Sōshitsu can hardly be blamed). Nevertheless, wishing to share the gift tea with his guests, he decided to use the furoshiki in which the natsume was tied as a fukusa when serving the tea in the sa-tsū-bako (a new fukusa had to be used with each new kind of tea, to prevent contamination). Rikyū was informed of this, and not only approved, but began to imitate the practice during his own chakai.

Oribe is the one who began to make his own fukusa of purple-dyed Japanese cloth† (and of the same size as these furoshiki, since he found that a fukusa 8-sun by 8-sun 2-bu was actually easier to handle than one made from a larger piece of cloth), and this idea caught on among the machi-shū in the years after Rikyū’s death (when they looked to Oribe for an explanation of the chanoyu of Jōō’s middle period as part of the effort to repudiate Rikyū’s influence on chanoyu†).

___________

*The practice seems to have been established by Jōō (though probably based on even earlier traditions). With imported cloth rare and costly, and since the furoshiki in which the container of gift tea was tied was used only once (and would not be seen by the guests -- immediately after removal it was tied in a knot and put into the host’s left sleeve), the best-quality native cloth available was used. Dark purple (it is almost black -- a deep brown-purple shade) was the most difficult color to achieve using natural dyes, hence it is the color that was preferred by Jōō for this purpose.

†Red fukusa arose from a very different (and confused) route. When Sōtan was called upon to serve tea to the court of Tōfukumon-in [東福門院; 1607 ~ 1678] (Tokugawa Masako [徳川和子], granddaughter of Ieyasu, and the consort of the retired emperor Go-mizu-no-o [後水尾天皇; 1596 ~ 1680]), he was distressed to find that the women’s lipstick stained the chakin like blood. Therefore Sōtan had his chakin dyed scarlet, to hide the stains. Later generations, hearing about the dying of the “tea cloth” red from the dyers, but lacking access to the details (the word chakin [茶巾] was sometimes used as an alternate name for the fukusa), people began to assume that the thing that was dyed red for the women was the temae-fukusa. Since this dichotomy fit into the Tokugawa’s neo-Confucian segregation of the sexes, women using a red fukusa became standard practice.

†Sōshitsu, who was 11 years old at the time, was introduced to Jōō shortly before the latter’s death. It is said that Jōō (who was no longer teaching at that time -- as was the convention of the day, where the actual teaching was done by the senior disciples gathered around the master) is the one who introduced Oribe to Rikyū, and advised him to seek instruction with this favored disciple (perhaps sensing some sort of fellowship of the spirit would arise between the two -- and, of course, pointing him in the direction of Jōō’s other main disciple, Uesugi Kenshin, would have been a disservice, since Kenshin was antagonistic to the direction that the government was taking, and association with him could have lead to the young man’s ruin). Nevertheless, the myth that Furuta Sōshitsu had studied with Jōō arose among the machi-shū after Rikyū’s seppuku (perhaps the rumor was started by Imai Sōkyū), and so it was to him that the group of which Shōan and Sōtan were members looked for guidance in those troubled times.

Oribe seems to have studiously answered their questions (only), while offering nothing about which his interlocutors were too ignorant to ask (the transcripts of these interactions are truly startling -- the depth of minute detail in Sōshitsu’s knowledge is absolutely breathtaking), and so carefully protected Rikyū’s legacy from being usurped by his antagonists. The result, unfortunately, is that most of what we associate with Rikyū was actually done by Jōō or Sōshitsu, while most of Rikyū’s true teachings went with Oribe to his grave (only to be rediscovered in the 20th century when Rikyū’s densho began to come to light).

==============================================

I. The first arrangement.

This first arrangement shows what might be considered the basic way in which a karamono-chaire and a dai-temmoku might be arranged together on the fukuro-dana. The chaire is placed on its kane (though not as a mine-suri [峰摺り])*, while the temmoku “overlaps” its kane by one-third (in other words, the foot of the temmoku -- not that of the dai -- is located immediately to the right of its kane). This results in a separation between the chaire and the hane of the dai of 2-sun.

The hishaku is associated with the right-most kane on the naka-dana, while the kō-dana has been left empty. And the mizusashi and futaoki have been arranged together in their compartment on the ji-ita, as usual.

While the kae-chawan† has been placed in the ji-fukuro, it is not included in the kane-wari count, meaning that the tana holds five units, and so is han [半].

___________

*The ku-den elucidates this matter -- that, because this is a karamono-chaire (albeit not one of the very highest rank), it rests on the kane, though not as a mine-suri.

†Both the Shukō-chawan and the ido-chawan were used as kae-chawan in the early days, and an ido-chawan was most likely the kae-chawan on this kind of occasion.

The reason why a chawan of a different size was traditionally preferred as the kae-chawan is because, since this chawan has only a supporting role in the temae (aside from bringing out and removing the chakin and chasen at the beginning and end of the service of tea, its only other participation in the temae was to give the host a place to clean the chasen with cold water at the end of the temae), a second chakin is not necessary -- because, while the chakin is folded first in thirds when prepared for a temmoku (or other small bowl -- including things like the raku chawan), it is folded first in half when it will be used to dry a large chawan. Thus, even without a new chakin, a clean surface is presented for use simply through the act of refolding the chakin. This is not possible if the two chawan are of the same size (and in such a case -- according to the Nampō Roku -- two different chakin would have to be used, folded together rather as if they were a single chakin of double the usual width: the so-called “shin chakin” [眞茶巾] used by some schools in their higher temae replicates this idea, which seems to have been the inspiration, though apparently the ancients considered that using separate chakin, rather than one of double length, was “necessary” to completely separate the effects of wiping the first bowl from contaminating the second).

——————————————–———-—————————————————

II. The second arrangement.

Here the temmoku and karamono-chaire are arranged together more formally, by being placed together on a naka-bon. Though the sketch is a little confusing, the intention of the red line is to show that the chaire is resting on its kane, albeit not as a mine-suri [峰摺り]*. Meanwhile the temmoku (which is placed on the tray tied in its shifuku, but without its dai) is arranged so that it “overlaps its kane by one-third” (the foot of the temmoku is immediately to the right of the kane with which it is associated), resulting in a separation of 2-sun between the chawan and the chaire†.

Both the naka-dana and kō-dana are left empty‡, while the futaoki is placed next to the mizusashi, as usual.

Looking at the kane-wari, the tana here has a han [半] value, which is appropriate to the goza of a gathering held during the daytime**.

___________

*This appears to be the purport of the ku-den, according to the commentators.

†When the temmoku is 4-sun in diameter, and the chaire is a 2-sun 5-bu katatsuki (or other shape with the same diameter -- many of the kansaku karamono chaire [韓作唐物茶入] were made this size, while being shaped like the famous Chinese ko-tsubo [小壺]).

4-sun, and 4-sun 9-bu, are the standard sizes of chawan that match Jōō‘s system of seven kane. (The Shukō-chawan, with a diameter of 5-sun 2-bu, was too large to display in this setting, other than as a mine-suri.)

‡This naka-bon kazari [中盆飾], to use its formal name, was derived directly from one of the original daisu arrangements, and the daisu, of course, does not have these tana present between the ten-ita and the ji-ita. Thus, to leave them empty, is not a problem.

**For purposes of kane-wari, the empty tana are counted as chō [調]. Therefore, han (the ten-ita, which has a single unit arranged on it) + chō (the empty naka-dana) + chō (the empty kō-dana) + chō (the mizusashi and futaoki on the ji-ita count as two units because they contact different kane) gives a total of han.

1 note

·

View note

Text

HOW YOU BUY A STARTUP

When eminent visitors came to see us, we were a bit sheepish about the low production values. Obviously that's false: anything else people make can be well or badly designed; why should this be uniquely impossible for programming languages? The urge to look corporate—sleek, commanding, prudent, yet with just a touch of hubris on your well-cut sleeve—is an unexpected development in a time of business disgrace. In fact, they're lucky by comparison. And if they're driven to such empty forms of complaint, that means you're doing something rather than sitting around, which is the reason that high-tech areas only happen around universities. Scientists don't learn science by doing it. He's now considered the best of that period—and yet not do as good work, on an absolute scale, as you would if you were a specimen under their all-seeing microscope, and make it seem as if he saw it as a drawback of senility, many companies embrace it as a valuable source of tips—more like manning a mental health hotline. The European approach reflects the old idea that new things come from the margins? Sure, it can be interesting if it poses novel technical challenges.

The whole tone is bogus. Someone like Bill Gates can grow a company under him, but it's confusing intellectually. The most important way to not spend money is by not hiring people. But when I consider what it would take to reproduce Silicon Valley in Japan, because one of Silicon Valley's most distinctive features is immigration. It's probably because you have to find peers for yourself, you stop learning from this. They happily set to work proving theorems like the other mathematicians over in the math department had the job of replying to people who like unions, because it takes less time to serve founders than to micromanage them. But it will be a good time to start any company that competes by litigation rather than by making good products. But I didn't realize why. Doctors discovered that several of his arteries were over 90% blocked and 3 days later he had a quadruple bypass.

GMail. The monolithic, hierarchical companies of the mid 20th century are being replaced by networks of smaller companies. It sounded promising. It must once have been inhabited by someone fairly eccentric, because a they may be on the board of someone who will buy you, and if you love to hack you'll inevitably be working on projects of your own. And since success in a startup, than smart users. Let's start with the most basic question: will the future be better or worse it looks as if Europe will in a few decades speak a single language. Even a bad cook can make a difference. When I finished grad school in computer science I went to visit my family twice. I was a philosophy major in college. Not wanting to blow such a public commission, he'd play it safe and make the talk a list of n things. And though this feels stressful, it's one reason startups win.

This talk was written for an audience of investors. They're like dealers; they sell the stuff, but they haven't followed it to its conclusion. Up till a few years ago, writing essays was the ultimate insider's game. Google understands a few other things most Web companies still don't. Junior professors are fired by default after a few years ago, it turned out to vary a lot. Do you need a San Francisco? What fraction of the smart people who want to live where the smartest people and get them to come to your country.

If you're lucky you can get in three words. We never even considered that approach. But regardless of whether patents are in general a good thing, but slower. These problems aren't intrinsically difficult, just unfamiliar. I put the lower bound at 23 not because there's something that doesn't happen to your brain till then, but because it gives them more control. After all, as most VCs say, they're more interested in the people who create technology, and some may look quite different from universities. Young startups are fragile. That's the way to do that, you have to say actually is a list of n things is that we get on average only about 5-7% of a much larger number of neanderthals in suits. 7 billion, and the doctors figure out what's wrong. And I can see why political incorrectness would be a way to get to know good hackers. Getting money from an actual VC firm is a bigger deal than getting money from angels.

Universities and research labs—partly because talent is harder to judge, and partly because people pay for these things, so one doesn't need to rely on teaching or research funding to support oneself. Email was not designed to be used the way we now know something like our weight. Paris has the best eavesdropping I know. Although a lot of people to help them. What difference does it make how many others there are? A rounds are not determined by asking what would be best for the companies. You can't fight market forces forever. And if you're a quiet, law-abiding citizen most of the good people will be outsiders. Politics, like religion, is a concept known to nearly all makers: the day job. More people are the right sort of person who could get away with hiring thugs to beat up union leaders today, but if you're a technology company, their thoughts are your product. Microsoft's original plan was to make money, you tend to be in a place where you can win big by taking the bold approach to design, and having the same people both design and implement the product. Whatever you make will have to be some mechanism to prevent people from saying everything is important.

That's why oil paintings look so different from watercolors. The reason these conventions are more dangerous is that they can do original work. But we knew it was possible to start a startup today, there are only three places I'd consider doing it: on the Red Line near Central, Harvard, or Davis Squares Kendall is too sterile; in Palo Alto on University or California Aves; and in Berkeley immediately north or south of campus. They also wanted very much to get rich, startup founders will almost automatically fund and encourage new startups. Whatever you build, make it fast. In those days you could go public as a dogfood portal, so as a company. Even hackers can't tell. The conversations you overhear. It seemed possible to start a startup when they meet people who've done it. Maybe it would be between a boss and an employee. The difficulty of firing people is a drop in the bucket by immigration standards, but would apologize abjectly if there was any signal left.

But the problem is more than just deciding how to implement some spec. Outsiders don't have to content themselves anymore with a proxy audience of a few smart friends. Then I realized: maybe not. It's natural for US universities to compete with focus is to see what it's like in an existing business before you try running your own. And indeed, you can watch them learn by doing. Good PR firms use the same simple-minded model. They don't have time to work. One of the exhilarating things about coming back to Cambridge every spring is walking through the streets at dusk, when you can see into the houses. In the US things are more haphazard. At the time, were worth several million dollars. A real essay, as the name implies, is dynamic: you don't know very well, you can compete with delegation by working on larger vertical slices, you can manufacture them by taking any project usually done by multiple people and trying to do it, do it. It can get you factories for building things designed elsewhere.

#automatically generated text#Markov chains#Paul Graham#Python#Patrick Mooney#drop#philosophy#years#mathematicians#US#challenges#concept#something#spec#game#way#startup#math#science#future#neanderthals#till#bucket#school#dollars#tone#founders#people#talk#country

0 notes

Text

The False Choice Between Science And Economics

By DAVID SHAYWITZ, MD, PhD

As the nation wrestles with how best to return to normalcy, there’s a tension, largely but not entirely contrived, emerging between health experts—who are generally focused on maintaining social distancing and avoiding “preventable deaths”—and some economists, who point to the deep structural harm being caused by these policies.

Some, including many on the Trumpist-right, are consumed by the impact of the economic pain, and tend to cast themselves as sensible pragmatists trying to recapture the country from catastrophizing, pointy-headed academic scientists who never much liked the president anyway.

This concern isn’t intrinsically unreasonable. Most academics neither like nor trust the president. There is also a natural tendency for physicians to prioritize conditions they encounter frequently—or which hold particular saliency because of their devastating impact—and pay less attention to conditions or recommendations that may be more relevant to a population as a whole.

Even so, there are very, very few people on what we will call, for lack of a better term, “Team Health,” who do not appreciate, at least at some level, the ongoing economic devastation. There may be literally no one—I have yet to see or hear anyone who does not have a deep appreciation for how serious our economic problems are, and I know of a number of previously-successful medical practices which are suddenly struggling to stay afloat amidst this epidemic.

In contrast, at least some on—again, for lack of a better term—“Team Economy” seem to believe that the threat posed by the coronavirus is wildly overblown, and perhaps even part of an elaborate, ongoing effort to destroy Trump.

Yet even if some partisans are intrinsically unpersuadable, I suspect that if Team Economy had a more nuanced understanding of Team Health, this could facilitate a more productive dialog and catalyze the rapid development and effective implementation of a sustainable solution to our current national crisis.

For starters, it might help Team Economy to know that even pointy-headed academics appreciate that science is (or at least should be) a process we use, not an ideology we worship. Most researchers recognize every day how difficult it is to figure out biological relationships, and to make even the most basic predictions in the highly reductionist systems of a petri dish or a test tube.

Under typical conditions, scientists tend to do an exceptional amount of study before they cautiously suggest a new insight. It’s really hard to figure out how nature works, and each time we think we’ve understood even some tiny aspect of it, nature tends to surprise us again with an unexpected twist. While often maddening, this complexity is also what makes science so captivating, engaging, and intellectually seductive.

In the context of COVID-19, it is incredibly, absurdly challenging for anyone—including scientists—to get their heads around the rapidly evolving knowledge that is, in any case, preliminary and is being collected under difficult conditions.

This is not an environment conducive to understanding exactly what’s going on at a system-wide level, let alone a molecular one.

And yet, that’s what Team Health is trying to manage. They’re working to understand the very basic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), while simultaneously extrapolating from the data in order to make recommendations that are going to impact the lives of billions of people.

There is a saving grace: researchers aren’t starting from scratch. They are informed by studies of related pandemics—the influenza pandemic of 1917-1918, the SARS outbreak of 2002-2004, and the 2009 swine flu pandemic, for starters. Investigators are also leveraging all they’ve learned about the biology of related viruses to make educated guesses about how to approach the current threat, and using recently-acquired knowledge of how to harness the immune system in cancer to think about how we might help the immune system respond more effectively to a virus.

Most scientists recognize the limitations of their knowledge, and realize just how hard it is to extrapolate—which is why they tend to avoid doing so. But they also appreciate that even if understanding is difficult and prediction even harder, the process of science—the meticulous collection and analysis of data, the constructing, testing, and reformation of hypotheses—has proven phenomenally effective over the long haul. It has enabled us to better understand illness and disease, and to provide humanity with the opportunity for longer and less miserable lives than ever in the history of our species.

And even if this potential is not realized either universally, nor as frequently as we might wish, it’s still the best construct we have.

It beats, for instance, hoping that a disease will simply disappear, like a miracle. Hope is not a method.

The Trump administration ought to listen to scientists, but it need not accept their advice uncritically. And that’s because behind closed doors, scientists never (well, hardly ever) accept the advice—or data—from other researchers at face value. They invariably question techniques, approaches, and conclusions.

The foundational training course my classmates and I took in grad school in biology at MIT essentially ripped apart classic papers week after week, exposing the flaws, and highlighting the implicit assumptions—and these were generally top-tier pieces of work by legendary scientists. I came away from the course with a powerful sense of the fragility of knowledge, the difficulty of proof, and a deep respect for the researchers who are driven to pursue, persist, and publish—despite these intrinsic challenges.

No individual or organization should be so revered that their findings are beyond scrutiny or evaluation, whether he or she works for a drug company, an academic institution, or an NGO.

But what rankles people on Team Health isn’t thoughtful skepticism from Trump about a particular piece of data (if only!), but rather Trump’s apparent indifference to science as a whole, and the ease with which he casts it aside if it fails to comport with his narrative-of-the-moment.

Trump seems to treat science like just another point of view, embracing it when convenient, ignoring it when not. This sort of casual indifference rattles the people on Team Health because, for all their disagreements, researchers tend to believe that there is an objective reality they are attempting to describe and understand, however imperfectly.

The notion that a scientist’s inevitably hazy view of a real phenomenon—drawn from well-described, ideally reproducible techniques—is indistinguishable from a “perspective” that some presidential advisor, or morning cable host, or guy on Twitter pulls out of . . . well, let’s say thin air . . . seems irresponsible.

And that’s because it is.

The good news is that Trump has a real opportunity in the coming days to leverage the advice of both scientists and policy makers, should he choose to listen.

In the last week, two important reports were published, each by a cross-functional team of experts. One was organized by the Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke, and includes Trump’s former FDA Commissioner, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, and one of Obama’s national health technology leaders, Dr. Farzad Mostashari. The other is from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Both groups suggest that transition to normalcy will require an exquisite ability to rapidly identify new outbreaks and track down and quarantine individuals who are likely afflicted—the ability to test-and-trace.

The idea is that our country needs the ability to conduct something close to a precision quarantine, where we constrain the activity only of those likely exposed — which requires, of course, accurately determining who those people are.

To their credit, both groups focus not on high-tech solutions that might be challenging to implement and potentially threatening to individual privacy (most Americans are not looking to emulate the policies of South Korea or China), but rather on extensive contact tracing involving a lot of individual effort. In other words: good old-fashioned disease hunter shoe-leather.

This approach requires not just a lot of dedicated people, but also a testing capability that we are hopefully developing, but clearly don’t yet possess. For example, a recent Wall Street Journal article quoted New Hampshire’s Republican governor Chris Sununu complaining that his state received 15 of the much-anticipated Abbot testing machines Trump recently demonstrated at the White House—but only enough cartridges for about 100 tests. “It’s incredibly frustrating,” Sununu vented. “I’m banging my head against the wall.”

The reason all this matters (at least if, like me, you believe the health experts) is that the rate at which the population is developing immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is remarkably low, according to UCSF epidemiologist Dr. George Rutherford. He estimates the rate of population immunity in the United States is around 1 percent, and notes that it’s apparently only 2 percent to 3 percent in Wuhan—the center of the original outbreak.

Herd immunity—the ability of a population’s background level of immunity to protect the occasional vulnerable individual—requires levels more than 10 fold above this (the actual figure depends on the infectivity of the virus; for ultra-infectious conditions like measles, more than 90% of a population must be immune; for the flu, which is less infectious, the figure is closer to 60%; SARS-CoV-2 is likely to be around this range). This means that, in Rutherford’s words, “herd immunity for this disease is mythic”—until there’s an effective vaccine.

Translation: For the foreseeable future, almost all of us are vulnerable. And we will remain vulnerable until therapies emerge.

Health experts worry that without a transition that includes provisions for meticulous contact tracing, rushing headlong back to a vision of normalcy would likely result in a rapid reemergence of the pandemic, and potentially, a need for more wide-spread quarantines—which would drive a stake into the heart of any economic recovery.

The truth here is that Team Economy doesn’t need to push against Team Health, because they’re after the same thing. If Trump embraces a transition that recognizes both the economic needs of the country and the wisdom of leading health experts and policy makers, he may succeed in leading a weary but irrepressibly resilient nation out of our current crisis, and into a durably healthy, economically promising future.

David Shaywitz, a physician-scientist, is the founder of Astounding HealthTech, a Silicon Valley advisory service, and an adjunct scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

This article originally appeared on The Bulwark here.

The post The False Choice Between Science And Economics appeared first on The Health Care Blog.

The False Choice Between Science And Economics published first on https://venabeahan.tumblr.com

0 notes

Text

The False Choice Between Science And Economics

By DAVID SHAYWITZ

As the nation wrestles with how best to return to normalcy, there’s a tension, largely but not entirely contrived, emerging between health experts—who are generally focused on maintaining social distancing and avoiding “preventable deaths”—and some economists, who point to the deep structural harm being caused by these policies.

Some, including many on the Trumpist-right, are consumed by the impact of the economic pain, and tend to cast themselves as sensible pragmatists trying to recapture the country from catastrophizing, pointy-headed academic scientists who never much liked the president anyway.

This concern isn’t intrinsically unreasonable. Most academics neither like nor trust the president. There is also a natural tendency for physicians to prioritize conditions they encounter frequently—or which hold particular saliency because of their devastating impact—and pay less attention to conditions or recommendations that may be more relevant to a population as a whole.

Even so, there are very, very few people on what we will call, for lack of a better term, “Team Health,” who do not appreciate, at least at some level, the ongoing economic devastation. There may be literally no one—I have yet to see or hear anyone who does not have a deep appreciation for how serious our economic problems are, and I know of a number of previously-successful medical practices which are suddenly struggling to stay afloat amidst this epidemic.

In contrast, at least some on—again, for lack of a better term—“Team Economy” seem to believe that the threat posed by the coronavirus is wildly overblown, and perhaps even part of an elaborate, ongoing effort to destroy Trump.

Yet even if some partisans are intrinsically unpersuadable, I suspect that if Team Economy had a more nuanced understanding of Team Health, this could facilitate a more productive dialog and catalyze the rapid development and effective implementation of a sustainable solution to our current national crisis.

For starters, it might help Team Economy to know that even pointy-headed academics appreciate that science is (or at least should be) a process we use, not an ideology we worship. Most researchers recognize every day how difficult it is to figure out biological relationships, and to make even the most basic predictions in the highly reductionist systems of a petri dish or a test tube.

Under typical conditions, scientists tend to do an exceptional amount of study before they cautiously suggest a new insight. It’s really hard to figure out how nature works, and each time we think we’ve understood even some tiny aspect of it, nature tends to surprise us again with an unexpected twist. While often maddening, this complexity is also what makes science so captivating, engaging, and intellectually seductive.

In the context of COVID-19, it is incredibly, absurdly challenging for anyone—including scientists—to get their heads around the rapidly evolving knowledge that is, in any case, preliminary and is being collected under difficult conditions.

This is not an environment conducive to understanding exactly what’s going on at a system-wide level, let alone a molecular one.

And yet, that’s what Team Health is trying to manage. They’re working to understand the very basic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), while simultaneously extrapolating from the data in order to make recommendations that are going to impact the lives of billions of people.

There is a saving grace: researchers aren’t starting from scratch. They are informed by studies of related pandemics—the influenza pandemic of 1917-1918, the SARS outbreak of 2002-2004, and the 2009 swine flu pandemic, for starters. Investigators are also leveraging all they’ve learned about the biology of related viruses to make educated guesses about how to approach the current threat, and using recently-acquired knowledge of how to harness the immune system in cancer to think about how we might help the immune system respond more effectively to a virus.

Most scientists recognize the limitations of their knowledge, and realize just how hard it is to extrapolate—which is why they tend to avoid doing so. But they also appreciate that even if understanding is difficult and prediction even harder, the process of science—the meticulous collection and analysis of data, the constructing, testing, and reformation of hypotheses—has proven phenomenally effective over the long haul. It has enabled us to better understand illness and disease, and to provide humanity with the opportunity for longer and less miserable lives than ever in the history of our species.

And even if this potential is not realized either universally, nor as frequently as we might wish, it’s still the best construct we have.

It beats, for instance, hoping that a disease will simply disappear, like a miracle. Hope is not a method.

The Trump administration ought to listen to scientists, but it need not accept their advice uncritically. And that’s because behind closed doors, scientists never (well, hardly ever) accept the advice—or data—from other researchers at face value. They invariably question techniques, approaches, and conclusions.

The foundational training course my classmates and I took in grad school in biology at MIT essentially ripped apart classic papers week after week, exposing the flaws, and highlighting the implicit assumptions—and these were generally top-tier pieces of work by legendary scientists. I came away from the course with a powerful sense of the fragility of knowledge, the difficulty of proof, and a deep respect for the researchers who are driven to pursue, persist, and publish—despite these intrinsic challenges.

No individual or organization should be so revered that their findings are beyond scrutiny or evaluation, whether he or she works for a drug company, an academic institution, or an NGO.

But what rankles people on Team Health isn’t thoughtful skepticism from Trump about a particular piece of data (if only!), but rather Trump’s apparent indifference to science as a whole, and the ease with which he casts it aside if it fails to comport with his narrative-of-the-moment.

Trump seems to treat science like just another point of view, embracing it when convenient, ignoring it when not. This sort of casual indifference rattles the people on Team Health because, for all their disagreements, researchers tend to believe that there is an objective reality they are attempting to describe and understand, however imperfectly.

The notion that a scientist’s inevitably hazy view of a real phenomenon—drawn from well-described, ideally reproducible techniques—is indistinguishable from a “perspective” that some presidential advisor, or morning cable host, or guy on Twitter pulls out of . . . well, let’s say thin air . . . seems irresponsible.

And that’s because it is.

The good news is that Trump has a real opportunity in the coming days to leverage the advice of both scientists and policy makers, should he choose to listen.

In the last week, two important reports were published, each by a cross-functional team of experts. One was organized by the Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke, and includes Trump’s former FDA Commissioner, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, and one of Obama’s national health technology leaders, Dr. Farzad Mostashari. The other is from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Both groups suggest that transition to normalcy will require an exquisite ability to rapidly identify new outbreaks and track down and quarantine individuals who are likely afflicted—the ability to test-and-trace.