#enslavement and globalisation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Guardian: ‘We are all mixed’: Henry Louis Gates Jr on race, being arrested and working towards America’s redemption

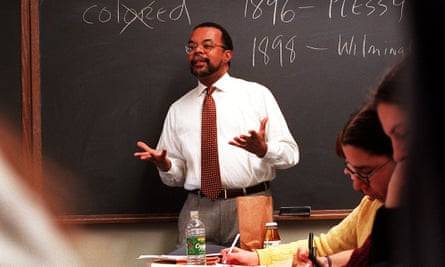

The first time I met Henry Louis Gates Jr raised more questions than it answered. It was the year 2000, I was still a teenager, and he – already a distinguished Harvard professor – was hosting a launch for his new BBC and PBS series Wonders of the African World.

I remember the occasion as a series of firsts – my first TV launch party, first documentary series I’d seen on African civilisations, first encounter with a real-life Harvard professor. I remember wondering whether the circumstances were normal. The venue was the British Museum, an institution that harbours a practically unprecedented quantity of colonial plunder. Was it, I wondered, a deliberately ironic choice? Were all Harvard professors as friendly and personable as Gates, whom everyone calls “Skip”, and was charmingly informal and kind? And perhaps most pressingly, was it normal for Harvard professor TV presenters to dress as Gates so memorably had, in shorts, socks, and a ranger’s hat?

Gates, whom I am meeting again for the first time since that day 24 years ago, remembers it for entirely different reasons. “I got in a lot of trouble for that show,” he says, cheerfully. “I was the first black film-maker to talk about African involvement in the slave trade.” And, he adds, with undeniable pride: “It was the first internet controversy involving black folks!”

The documentary, which followed Gates as he examined ancient civilisations from Axum to Nubia and Great Zimbabwe to Timbuktu, was indeed controversial. Alongside the African cultures he visited, he demonstrated great interest in African complicity in the transatlantic slave trade, an interest that managed to alienate almost everyone who was black.

African scholars complained that Gates revealed an approach to African culture through a western-centric, American lens. African-American scholars claimed his emphasis on black involvement “got the white man off the hook for the Atlantic slave trade”.

I’m speaking to Gates over Zoom. I’m in uncharacteristically rainy Los Angeles, he’s in sunny Miami. As we speak, he turns his laptop screen around, attempting to goad me – successfully – into jealousy at the sight of blue sky and serene ocean from his seaside condo. He is in Florida for a family wedding, and our call is periodically interrupted by good-natured family members coming in and out, as people mill around preparing for the big day. Family is important to Gates. His new book, The Black Box: Writing the Race, opens with the story of his grandchild Ellie, who inspired the book’s title.

Born recently to Gates’s daughter, who is mixed race, and his son-in-law, who is white, Ellie “will test about 87.5% European when she spits in the test tube,” Gates writes, adding that she “looks like an adorable little white girl”. And yet when Ellie was born, Gates’s priority, he reveals, was to make sure her parents registered her as a black child, ticking the “black” box on the form stating her race at birth. “And because of that arbitrary practice, a brilliant, beautiful little white-presenting female will be destined, throughout her life, to face the challenge of ‘proving’ that she is ‘black’,” Gates writes.

Any discomfort flowing from this – both Gates’s decision and his perception of it – is deliberately intended as a commentary on the discomfort of race itself. How can race not be contradictory, Gates suggests, when it was constructed in service of racism, and yet has been alchemised into a cultural identity celebrated by those most oppressed by it?

The Black Box applies this analysis to the lives of famous African Americans. The poet Phillis Wheatly, an enslaved young woman who was required to “prove” to white observers that she was capable of writing the poetry she so eloquently composed. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who constructed parental relationships – the reality being that he knew little of either his mother or father – to refute ideas, prevalent at the time, that if a black person was intellectual, that was because of white parentage. The history of what black Americans have both been called and called themselves, encompassing a fascinating and ongoing debate about the usage of “negro”, “coloured”, “African American”, and “black”.

That work began far away from Harvard, in a working-class black family in the hills of West Virginia. Gates’s father had two jobs, one at a paper mill and another as a janitor, and his mother was a home-keeper, and later a cleaner for a white family. After attending the local public school, Gates obtained an undergraduate place at Yale in 1969.

Although proudly black, the family vaguely knew it had white ancestry, particularly through Gates’s paternal grandfather. “My grandfather looked so white, we called him Casper, after Casper the Friendly Ghost,” Gates laughs. “I mean his skin was translucent!” Gates had thought one ancestor – his paternal great, great-grandfather – had been white. But when he tested his DNA, he discovered a different picture.

“Imagine my surprise when I received my first DNA results, and I’m 49% white!” he exclaims. “What that means is that half of my ancestors on my family tree for the last 500 years were white, and the other half were black, and that was an amazing lesson to me. So, what does that mean about identity? It means that I was socially constructed as a negro American when I was born in 1950. But my heritage, genetically, is enormously complicated.”

This discovery set Gates on a path that has become perhaps the dominant part of his legacy, as the host of a popular PBS show Finding Your Roots, in which he leads other prominent Americans of all racial backgrounds – figures including Oprah, Julia Roberts, Kerry Washington and Quincy Jones – on a similar journey, through DNA testing and genealogy, in which they trace their family tree.

“I have never tested an African American who didn’t have white ancestry,” Gates says. “And that’s quite remarkable to me.”

“Paradoxically these DNA tests deconstruct the racial essentialism we’ve inherited from the Enlightenment, because they show that we are all mixed,” he continues. “It’s a mode of calling those categories into question, showing scientifically that they were fictions, and freeing us from the discourse that sought to imprison us in the black box, the white box, the Native American box.”

The tightrope Gates walks lies in rejecting blackness as a racial category, while embracing it as a cultural tradition. His most recent PBS documentary series, Gospel, which relays the origin story of gospel music, is perhaps my favourite work of his, celebrating both the heartbreaking beauty of black spiritual tradition in America, and its seismic impact on global culture.

When I share my emotion at the series, Gates is unable to resist subverting the theme. He bursts into a rendition of Can the Circle Be Unbroken?, a 1930s country number by the white gospel group the Carter Family.

“[On a cold and] cloudy day/ when I saw the hearse come rollin’/ for to carry my mother away/ Will that circle be unbroken/ By and by, Lord, by and by,” he sings, in a surprisingly rich tenor.“White people wrote that song, black people love that song!” he exclaims.

The current climate, in which political tribes are more polarised than ever, has only deepened his resolve to push back against the idea that black people should all agree. In this, he sometimes comes across as a man from another age – a more charming one, real or imagined – in which everyone could sit down together and work it all out.

“I grew up in a working-class town. People are goodhearted. They want what everybody else wants: to make enough money to live comfortably, to send their kids to college, to be able to go on vacation, to have leisure time, to have some joy in their life and not just be punished by drudgery, not have economic anxiety,” he says.

Gates’s stance on reparations is a case in point. The murder of George Floyd in 2020, and the current threat to black history studies from rightwing Republicans – some of Gates’s own work has been banned from schools in Florida under Governor Ron DeSantis – have only accelerated calls for restorative justice for enslavement.

Gates acknowledges the wrongs but disagrees with the solution. “Affirmative action plans go a long way… I think that’s a form of reparation,” he says. “But I just could not imagine any group of Americans deciding to dip into their pockets and pay a cash settlement for all that our enslaved ancestors suffered. I don’t think that’s realistic.”

When I disagree – citing examples of other societies that have paid reparations, Gates is firm. He even describes calls for reparations as “racial bullying”. “The bottom line is, you can’t bully people with calls for reparations because of the legacy of slavery,” he insists. “So we need leaders who are thoughtful and nuanced and sensitive. I should know. I’ve been in America for 73 years.”

Gates’s optimistic view of American decency was famously pushed to breaking point in 2009, when he – already a famous professor and TV personality – achieved unwelcome notoriety. Returning home from filming in China, he was struggling with the lock on his door, as he entered his own property. A call from a neighbour – who reported a suspicious black male attempting to enter a house – led to the arrival of police. Gates was initially suspected of breaking into his own home. When it was established that he lived at the property, he was arrested anyway for disorderly conduct. Widespread coverage – which made international news – pictured an angry Gates, handcuffed, being led away from his own front porch.

Gates was released after Harvard sent its lawyers over. Further controversy ensued when President Barack Obama commented on the debacle, calling the police’s decision to arrest Gates “stupid”. The entire affair was resolved in a meeting at the White House in which Gates sat down for a beer with the officer who arrested him, the president, and vice-president Joe Biden.

The “beer summit”, as it became known, sparked wider conversations about racial discrimination in policing. Gates took a conciliatory line. “My heart went out to the officer when he told me he was just scared,” Gates says. “He had just wanted to go home that night to his wife. We shook hands and he gave me the handcuffs he had used to arrest me. And they’re now in an exhibit in the Smithsonian,” he adds, with a weary air of triumphalism.

Beers with a well-intentioned black president and messages of racial conciliation seem a lifetime away in the current political climate. Yet Gates says his own teaching practice remains unthreatened by fears of censorship or backlash. “Fortunately, I have the freedom to teach, whatever way that I want and whatever content that I want,” he says.

Gates has been protected, perhaps, by his refusal to conform to the norms of either academic or celebrity life. He is one of the few people to have achieved fame as an academic, thanks to his long TV career. He credits that not to American broadcasters, but to his time in Britain, early on in his career. “My time in the UK was fundamental,” he says.

“One time we went to this Indian restaurant in Cambridge,” Gates recounts. “And Soyinka brings his own chilli. I mean, this Nigerian chilli he would make and carry with him – it was engine oil! And they said to me: we are from your future. We brought you here to tell you you’re not going to be a doctor. You are meant to be a professor. You’re going to be a scholar of African and African-American studies, and you’re going to make a difference.”

The prophetic nature of those remarks must have become obvious when Gates’s first book, The Signifying Monkey, was published in 1988, applying post-structuralist analysis to African-American vernacular and literary traditions. Since then, Gates has made a name for himself as a leading voice of African-American literary and cultural history. Yet it is his TV career that put him on a steady path to becoming an American national treasure. It was the British producer Jane Root, Gates tells me, who recruited him to present an episode of the long-running BBC series Great Railway Journeys in 1996, travelling with his two daughters through southern Africa.

“The whole conceit was this professor of African-American studies taking his mixed-race daughters to Africa to find their roots, only for them to say: ‘Our roots are in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’ve got nothing left in Africa, I want a Big Mac,’” Gates laughs. “The Guardian called it National Lampoon Goes to Africa, and that was just so honest and fresh. I would be giving my daughters this pompous lectures about Livingstone and, you know, they’d be rolling their eyes. And it was great.”

The success of that episode led to Gates hosting an entire series, Wonders of the African World, the show where I first met him all those years ago. “My whole life as a film-maker, I owe it to Jane Root, and to the BBC,” he says.

The concept so central to Wonders,of the descendants of the enslaved reconnecting with Africa, is as old as the enslavement that displaced them. Yet its modern iteration has exploded in recent years. Ghana, the west African nation that has long positioned itself as a hub for the “return”, now regularly records hundreds of thousands of additional visitors from the black diaspora, with festivals celebrating global blackness and ancestral connection. “I love it!” Gates says, of this growing phenomenon. “I think all African Americans should do two things. Take a DNA test to see where in Africa they’re from. And I think they should visit the continent.”

The return is a joyful movement in which black people seek to heal the bonds severed by enslavement and globalisation. Yet if underneath it lies a pessimism – that racism makes western nations unliveable – it is not one that Gates shares.

He acknowledges that America is broken. “I remember under John Kennedy and certainly with Bobby Kennedy, and with Martin Luther King, we thought poverty was a disease that could be cured. No one thinks that today,” he laments. But rather than offering a way out, he believes in the country’s redemption, and hopes he and his work will play a role. “We have to fix it,” he says. “And we have to fix it together.”

In typical contrary fashion, Gates turns to histories rooted in the darkest side of America’s racial capitalism to find inspiration for believing in America’s potential. At the turn of the 20th century, when black women faced racist characterisation as “thieves and prostitutes”, they retaliated by forming “coloured women’s clubs”, to improve their image, foster racial pride, and advocate civil rights.

“I think of that movement,” Gates says. “Their motto was ‘lifting as we climb’. And I think that should be the motto of American capitalism. We lift, as we climb.”

The Black Box: Writing the Race by Henry Louis Gates Jris published by Penguin (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

#american racism#Black and white#Henry Louis Gates Jr#‘We are all mixed’: Henry Louis Gates Jr on race#being arrested and working towards America’s redemption#white supremacy#white lies#biracially american#america is biracial#biracial#Their motto was ‘lifting as we climb.#enslavement and globalisation#racism

0 notes

Text

👹👹👹

#smart cities#smart cars#smart TV#silly people#lockdowns#tracking system#facial recognition#enslavement of humanity#end of privacy#communist regime#one world order#globalisation#one world government#you will own nothing#speak up#standup#speaktruth#fight for justice#crimes against humanity#wwg1wga#please share

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, Mr. Haitch

You mentioned before in one of your answers that "climate and social justice are inextricably linked." Do you mind saying how so?

Thank you!

Our current geological age - the Anthropocene - is inextricably linked to the history of capitalism, no matter how you date it. The three main theories are that it began in 1945 at the close of the second world war and the international trade agreements and advent of nuclear testing; that it began with the industrial revolution; or (and this is the theory I subscribe to) it began between 1492 and 1610 with European colonialism in the Americas.

The anthropocene is defined as an age of globalised human control and impact on the earth's environment, ranging from climate change to biodiversity, and the early history of Europe's colonisation of the Americas fits the bill pretty well. Beginning in 1492 the indigenous population of the Americas collapsed by 95% (population estimates run from 60 million to 120+, the loss represents about a 10% global population loss), along with vast amounts of infrastructure including cities, towns, trading outposts, road networks, irrigation systems, and so on - all in an area (especially equatorial America) where the local flora grows rapidly. The deaths of so many with so few colonisers to replace them saw a rapacious period of reforestation, creating a massive carbon sink which drew down an estimated 13 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, ushering in The Little Ice Age. Global temperatures fell for the first time since the agricultural revolution, and put huge stress on an already fracturing feudal system. Over the course of 200 years Europe went through fits of social and political revolution, where the aristocracy were (sometimes violently) deposed by an ascendant merchant class ushering in our current age of liberal democracy, the enshrining of private property, and fixation on trade and prosperity.

The population collapse also provided a rationale for the Atlantic slave trade, as the enslaved workforce the Europeans had been using up until then were pretty much all dead.

With me so far?

Since the industrial revolution our economic system has been reliant on exponential growth, leading to an ever increasing appetite for raw materials, land, and cheap (or free) labour. The environmental and human costs have increased in lock step with one another - both crises borne of the same root. We cannot address one without addressing the other.

This is a very condensed version of the argument and I'm glossing over a lot here. If you're interested I'd recommend tracking down the following texts (usually available at libraries, particularly University ones):

The American Holocaust, David Stannard

The Human Planet, Lewis and Maslin

The Problem of Nature, David Arnold

The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert

History and Human Nature, RC Solomon

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes: Intersectionality is an inappropriate term in this context, and the use of it in this context divorces the word from Crenshaw's work to an extent. As her work is explicitly rooted in Critical Race Theory and arises out of the 1960s civil rights movement. The contexts aren't comparable, and probably Deluze's Assemblage is more appropriate in this context, especially when you consider that Crenshaw is critiquing structural inequality and discrimination as it pertains to civil rights and the obscuring of black women under rmultiple axis' of power in the context of chattel enslavement and reconstruction etc.

If the dornish are facets of GRRM's colonial ruminations on the 'orient' then possibly it would be better to liken the relationship between Criston and Westeros as one rooted in Edward Said's Orientalism and his analysis on the west's perception of this nebulous concept of the 'orient' and the exoticism clasism of such a perception. However, divorcing black intellectual property from its context and reducing the nuance to make it a catch all term is in line with contemporary movements to divorce black women in particular from the inventions use to critique and engage with their existence.

Hmmmmm, will return to this thought probably and the cop opting of Critical frameworks and language and the sloppy way people use academic language and terms that reduce their effectiveness and obscures the work non-white academics have done in providing nuance in analysis with capitalism, colonialism and oppression. Also, there's probably a good essay here on examining the way in which fandom interacts with academic knowledge production to perpetuate certain ideological frameworks and fandom specific ways of using works for social critique. Tbh its not just fandom and the likes of twitter etc are to blame in part because people pick up language with no knowledge of the context and in greater globalisation whiteness does obscure as it is the lense people use for analysis. Ergo, if something isn't in a white framework of reference it has to be adapted until it can be or should be. Also, pigmentocracy is important to note her as a feature of these unconscious movements.

made a post a while ago about the implications of hotd criston being dornish and got some angry he was raised in the stormlands he’s not culturally dornish anons. if he’s visibly ethnically dornish enough that alicent comments on it immediately after seeing him that would obviously still affect his life in a pre-dornish-conquest westeros

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

STATE OF THE FIELD: MATERIAL CULTURE

Historians of material culture routinely begin introductory classes on the subject with a very similar set of activities. Often, they will ask students to draw their attention to an object they have with them (a pen, an item of clothing, the chair they are sitting on) and ask them to reflect upon it. What does it mean to them? How and by whom was it made? Where and why did they acquire it? Is it comfortable and does it promote particular emotional or sensory reactions? The responses to these exercises reveal powerful stories, centred on topics including prevalent consumer cultures, emotional investment and invisible labour. This task illustrates the pervasive ubiquity of material culture in human life, irrespective of, and yet shaped by, time, place and culture. Objects are omnipresent, and act as a uniquely sympathetic point of connection between humans, past and present. As Leonie Hannan and Sarah Longair have stated, ‘as long as humans have made material things, material things have shaped human history’. The time-defying nature of objects, the fact that you can touch silk once worn by Henry VIII or hold and feel the weight of the shackles that once bound an enslaved person, is part of their immense power as historical beacons. However, the mystic and elusive veneer of this connection through time has also presented an obstacle to the legitimization of material culture as a methodology by history as a discipline. [...]

To hold an object not only connects us to the emotional echoes of its past, but also to the sensory experiences it evokes. When we are lucky enough to unsheathe our hands from nitrile gloves in the museum store, the sensorial richness of haptic interaction with an object becomes apparent. Victorian velvet does not feel like the velvet found in modern fabric stores and an eighteenth-century teapot has a different weight and tactility from one from Ikea in the twenty-first century. Even the materiality of specific object types, as understood by their names and functions, evolves over time, and objects were handled and manoeuvred differently in the past. As with emotions, we should not imagine that we feel, smell, hear, taste, or even see in the same way as our ancestors. How we, as humans, process our responses to sensory stimuli is moulded by our social and cultural upbringings. Yet the sensory landscapes produced by and through objects, and the sensory strategies developed to navigate the material world, proffer rich veins for research. Kate Smith, for example, has demonstrated the importance of touch as part of the browsing practices of eighteenth-century consumers. Haptics, along with smell and taste for consumables, were key markers of quality, suitability and desirability in an ever-expanding world of goods.

Any reflection upon how objects are deciphered and comprehended through our senses calls us to consider the materiality of those objects. Artefacts (that is objects constructed by human hands) are themselves assemblages of different materials, processed and manufactured into something new. Literacy in materiality and making was present in rhetoric around material culture both in the pre-industrial age, and as industry and mass manufacture developed. How things were made, what they were made from, and how they were traded: this knowledge permeated society and shaped how people navigated their interactions with objects. Children learnt to differentiate flax from wool through play, and adults continued to engage in a world of making as both producers and consumers of material goods throughout the life cycle. Consumers could visit potteries and manufactories, and the wealthy might even invite industrialists into their homes to explain their inventions. Similar to the performative display of artisanal craft today, making was demonstrated and enacted, even in elite consumption. Mass manufacture and globalised production networks have generated a lacuna between production in distant factories and consumption in shops sanitised of manual labour. It is vital that historians, who are often part of a twenty-first-century culture which is disengaged with the practices of making, do not project this gulf back upon their readings of material interactions in the past.

—Serena Dyer, The Journal of the Historical Association (Volume 106, Issue 370)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prophecy, Paulina Penc

Shining bright is a series of paintings exploring the essence of popculture and aspects significant to modern times, accentuating the phenomenon of the future. The title itself refers to a famous song Diamonds, performed by Rihanna – one of the biggest pop stars nowadays. The reoccuring theme of the series is a shining material – gold and silver foils, tinware, crystals; everything you can find in cheap shops, store chains and popular videoclips. An inexpensive fabric, but at least it is nice and shiny. It diverts attention away from all the unwanted imperfections and all possible defects. The paintings, which are seemingly trivial and superficial, carry non-essentialism that reveals […] how unsuccessful was the traditional and globalising tendency of aesthetics […] and they gain a specific meaning in the context of modern popculture. The figurative scenes are entwined with images showing deformed objects of no practical use, devoid of worth and suggesting false show, aesthetically elevated to the status of artwork. In the painting Exploration of Ms Tulp, in reference to Rembrandt’s artwork, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp, the position of a doctor is taken by a woman studying the anatomy of contemporaneity, where a human body has been idealized to the level of ridicule. The silver man becomes a symbol of the perfect human – the protagonist of the computer game , the avatar on social media. Gender roles are only seemingly reversed. The silver man seems to be objectified, but as we face changing times, human nature stays the same: the protagonist of the painting as an ideal of masculinity, desires Ms Tulp – he wants to possess and enslave her, while Ms Tulp, being a typical woman, will not protest against it. There is a strong antagonism of nature versus nurture. As a self-portrait painter, I am placing myself at the very heart of a social dilemma concering the division of gender roles in the context of atavistic needs. The silver man symbolises an eternal dialogue between the past, the present and the future; he is Greek ideal of an ancient beauty and at the same time, an avatar of future where there is no space and/or time for body contact, and the body itself is a humbug, unreal creation: a baroque emblem of vanitas. A gold Celtic shield, a sign of eternity, becomes an alternative atribute in the context of the urge to stay forever young and beautiful. Just like a court jester disguised as prohpetical bard, I am fortelling a shining and fast-fading future, as I wink at my audience. Irony and distance are the easiest forms of human communication in the modern times, while indifference becomes a leading attitude, in which I find myself perfectly.

https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Painting-Prophecy/871567/2912991/view

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Dialectic of Violence

It’s perfectly clear that the original facts and concepts of today have changed completely and deliberately due to several powerful factors, the most important of which are: authority and media.

Right has become wrong, and wrong has become right, so you see whoever defends his honor and dignity is accused of transgression and criminality, and whoever defends his illegal occupied homeland is called a terrorist, and whoever urges adherence to true and authentic intellectual constants is called a retard and late-minded in the face of globalisation and development wheel.

For years Thinkers had talked about the origin of violence and they ascribed it to biological, cultural and social factors, whereas the political theorist Hannah Arendt in her work (thinking and judging), she criticised every trend they came up with as conclusive evidence which claims “violence is an innate instinct for X group of people” to confirm that man is not inherently evil, and that violence is not linked to the biological origin in any shape or form.

The kicker: The theory is nothing but racist political agenda to accuse a certain group of people -without evidence- of barbarism, while violence is a phenomenon we can find it throughout history and all the time, and in all societies, whether the nomadic or the urban.

Violence does not arise from a human nature, rather it arises due to oppression, control and exploitation, especially on the part of totalitarian regimes, including bourgeois and authoritarian power and the bad social and economic conditions they have perpetuated.

That is why we find thinkers distinguish between legitimate violence and unlawful violence. There are many forms for the use of force and violence that are considered “legitimate acts”, such as: the use of violent force to defend the homeland, as well as the use of violence against tyrannical regimes, and revolutions that change the course of society to what is better and eliminate corruption in it. Whereas unlawful violence is if it is from or against a regime and a state for the sake of domination, enslavement and tyranny, whether against itself or others. Therefore, if we want to understand the reality of the dialectic of violence between legality and unlawfulness, we must put it into reality without falling into unrealistic, irrational and unjustified theoretical judgments, and to understand how this violence is used by any party. Therefore, we must differentiate between constructive violence and destructive violence. Violence by dictators is different from violence by persecutors, in contrast to Anarchism that views violence only from one angle as always negative.

According to the German philosopher Herbert Marcuse, the violence that is for the sake of liberation or revolutionary violence, that is: violence that demands freedom and justice, is justified and legitimate violence. As for anarchic violence, it is the destructive violence and the violence of despots, and it is unlawful, whatever its justification. Violence, as mentioned earlier, is an ancient and existential phenomenon, it has existed with the existence of man since the beginning of history and since the first event of the conflict between human beings, which is the dispute between Cain and Abel. This conflict is not linked at all with the innate aspect that Hannah Arendt denied in her book "On Violence". Rather, it returns to many intertwined aspects, and it multiplies to encompass all aspects of life. Violence is a complex phenomenon that has its political, economic, social, cultural and psychological aspects in the first place.

It is not surprising when we live in an era of the phenomenon of violence, which is largely noticeable in all its dimensions, such as terrorism, wars, murder, aggression, tyranny and oppression. As it is said “each phenomenon has a cause.”

We must educate ourselves more and not rely on the media, politicians, artists and others to understand the facts of history, all of this has been formulated once again -including religion-to correspond to the whims and interests of the corrupt authorities and governments and those who are affiliated with secret governments whose aim is to destroy and change the features of the world and more.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Great Power Democracy Con: Promising the Moon to Destroy Humanity The United Kingdom is rightly proud of its National Health Service. When London hosted the Olympics in 2012, the opening ceremony included a little tableaux about the NHS, which was presented as one of the finest achievements of the host nation. However for over 40 years, whenever some public figure says “NHS” the next word is “reform”. Politicians are constantly saying there is something wrong with the NHS, and it needs reforming, though they differ widely on what its problems are, and what should be done about them. The slogan “NHS reform” has been so successful that few have realised its use is a very clever tactic. Whenever anyone raises an issue with something in the NHS, they are told they are talking about reform. Invariably this means structural reform – either more along the same lines, or reversing an existing reform. In most cases, the people who complain about the NHS aren’t talking about structural reform at all. They don’t like the behaviour of certain staff, or the waiting times, or the refusal to apologise for obvious misconduct. But the responses to these complaints are always about what sort of reform has taken place, or should, rather than the issue itself. So no one will ever discuss these serious issues, or admit that they exist. The only issue is reform – and of course this protects all those who might be misbehaving, or at least so they think. Does this sound familiar to residents of countries, who have had no experience of the NHS? It should. We’ve all heard so much about “reform” that the term long ceased to have any positive meaning, for exactly the same reason. It’s the same with “democracy” and “human rights” – the things we expect civilized societies to have. Few of those who espouse these things really want to see them in place. These words are used to protect this or that interest group from any consequences – and when we know who, we see exactly who our friends are. Cars without engines Take “economic reform”, which was imposed upon all the former Soviet and Eastern Bloc states after they freed themselves of their oppressive and corrupt systems. No longer would everything be run by an ultimately unaccountable state. The principles of capitalism, which had served rich countries well, would transform these newly-liberated states into progressive and prosperous members of the family of free nations. Have they? It’s been thirty years now. Still the former Soviet states are second-tier nations – what would be called the Rust Belt if part of a Western country. Reforming their economies hasn’t produced the dividends the same economic systems have produced in the countries which impose those systems upon them. Nor was economic reform the inevitable consequence of political change, the tool fit for the new national purpose. When the virulently anti-Communist Zviad Gamsakhurdia, an admirer of Ronald Reagan, declared Georgia independent he continued with a policy of Soviet-style state capitalism, because it had worked better in Georgia than in most places, and there was no point is dismantling everything over night when independence had already removed all the public services/goods previously provided by the Soviet Union. This gave Western countries a choice: stick with their political fellow traveller who followed a different economic path, or bring in a more compliant government which would. Strangely enough, this resulted in the former Communist leader Eduard Shevardnadze being installed after a coup conducted by criminal gangs, everything the West doesn’t agree with in theory, in order to get the economic reform which has left Georgia so poor that scavenging dogs have more prospects than the people. The only thing that mattered was economic reform. Why? Because in its name you could do anything. As the Saakashvili years proved, you have complete immunity both domestically and internationally if you say everything is being driven by economic reform and encouraged by the West. Economic reform means somebody else tells you what to do, and is given a blank cheque to do it. There is no instance in which countries which seek to reform their economies are allowed to do so themselves, as every IMF an World Bank rescue package, which involves more foreign influence and investment rather than less, demonstrates. Economic reform is like globalisation, it has so many meanings, it is devoid of any meaning. Economic reform is never conducted by locals who have advocated such policies for years. It is the province of foreign advisors, top down, who work under foreign rules, invented by those the advisors have to satisfy rather than the advisors themselves. Seldom is it need driven and based on principles of participatory development. Who is protected by this? Look at what the plum diplomatic postings are. Everyone wants to work in the developed countries, which don’t think they need economic reform. The countries which others say need help are where no one wants to go – so who is sent there? If you do something wrong, or are not up to the job, you are suddenly an economic reformer. It is often remarked that the EU is a dumping ground for politicians who have failed, even if once successful, in their home countries. Economically reforming countries get those too dubious for the EU. If people in developing countries complain they can’t live on their earnings, they are told that they are talking about economic reform. A lot of people in rich Western countries can also no longer live on their earnings, and no longer have much social safety net either. But if they complain, they are never told that they are talking about economic reform, only prospering more in the existing system. Who is protected by this? Mostly amongst those who are failures at home, but [suddenly] become experts, visiting firemen, as soon as they get off the plane in the reforming countries. They are those who want to make the shadiest deals with the shadiest people, on the grounds that this is “reform”. Ultimately, it is those who can be blackmailed as well as kept out of the way – who can be used to introduce the drugs that didn’t pass inspection, the high tar cigarettes banned where they are made, the labour exploitation outlawed at home and the network of public facilities sustained by arms and drug smuggling, all in the name of economic reform, when that is not the solution to the problems being presented. One man, one problem Ilham Aliev is fond saying that everyone has their own definition of democracy, so Azerbaijan must be a democracy because his definition is as good as anyone else’s. No leader of a mature democracy would publicly support such a position. The problem is, they know he is right, and they know they themselves have made it that way. In the name of democracy, elected leaders are removed because people who couldn’t vote for them think they aren’t democratic enough. Salvador Allende was a famous example, even though he did not dismantle Chile’s democracy by orienting the country towards the Marxist world, and General Pinochet and his pro-Western dictatorship did. But if people in developing countries complain about their governments not doing what they want, they are told they are crying for democracy. Like the demonstrators in Maidan Square in 2014 who wanted the Yanukovych government to grant them their legal rights, their problems and voices are hijacked for purposes they never intended, by actors they never wanted to side with. Every developed democracy has defects. In some countries the electoral system is so crude that governments are elected with a small minority of the votes, the United Kingdom and Canada being examples of this. In others there may be electoral equity but no accountability – the choice is so meaningless that the same political class stays in power and ignores the public, which has no levers to influence them, as the Marc Dutroux child abuse scandal in Belgium laid bare to a horrified world. Nevertheless, most people want democracy, and to say they live in one. So in its name, anything can be done by those who are introducing, improving or guaranteeing that democracy, even when those things have nothing to do with democracy itself. “Democracy” is taken to mean greater alignment with the Western world, rather than rule by the people through their freely and fairly elected representatives. Whatever the problem, that is the solution, and as long as the label “democracy” is attached to something, it can be part of that solution. Democratic reform means accepting development from some sources, considered democratic, over others. China is no democracy, but as long as democratic countries encourage its state companies to invest in the democratically developing country, it can take over all that country’s resources. If Russian tries the same, it is forbidden on the grounds that Russia is not democratic, though its system ticks far more boxes of the definition than China’s—and even by Western standards. Democracy means getting the right result and at the right time. If the people vote for the wrong person, as when they initially re-elected the Communists in Bulgaria, the democratic process must have been subverted by anti-democratic forces. If the right person subsequently takes power, even if through a coup or other non-democratic means, this is a triumph of democracy and an expression of the popular will, meaning foreigners who can’t vote there can introduce more changes to bolster, or rather enslave the right person. Shooting an elephant People are told they want democracy by those who want those people to have as little say as possible in the form and direction of their country. Who does this protect? But are those who don’t want their actions subject to any public scrutiny? Everything must be alright if it is done by a democracy in the name of democracy, and often out of an sense of obligation, to show who is in control. Go to any state which was once the colony of a greater power, and ask what was done there in the name of democracy, and you will see how little any elector could do about the crimes which scar those countries’ collective psyches to this day. Inhuman rights Supposedly The Boer War was fought between Transvaal and the British Empire over the rights of the uitlanders, foreign workers who were treated as second class citizens, or worse, by the Transvaal government. In order to safeguard the human rights of these workers, the British herded non-combatant South African civilians into concentration camps, the institutions for which the phrase “methods of barbarism” was coined. However, it was really about gold, as we know even from Nazi propaganda movies, such as Uncle Kruger. It’s the same everywhere. Human rights only apply to your own side. War crimes trials only involve losers. Genocide is only committed by those you don’t like, as Armenians are fond of saying about the global response to the events of 1917, and the Kurds say about all their neighbours, to be met with total indifference even when the world is complaining about the regimes of those same neighbours. Franklin D. Roosevelt often drew the distinction between “freedom to” and “freedom from”, his thesis being that you can’t have one without the other – you can’t give people freedom to own property if they don’t have freedom from poverty and exploitation. But when people complain they are victims of social and economic discrimination, they are not necessarily calling for human rights but relief from their problems. Why are people being told that they are calling for human rights? Because these rights have to be guaranteed by particular people, and more often than not the same ones who are denying them. Who is protected by saying everything is about human rights? Those who place ideology above all – who want to put their ideas above criticism, rather than the interests, and ideas, of those they claim to be advocating for. Soviet citizens remember when every man had the right to a job – so the state could do whatever it liked to them, and suppress their own views, justifying this by ideology. Israel can violate the rights of Palestinians with impunity so the ideology of Zionism can supersede human need, universal human rights, including the needs of Israelis. Human rights don’t protect the human but the inhuman. The one human right no activist will grant is the right of those they claim to be protecting to have different views and wants. When states intervene to guarantee human rights, it is only the rights of those who want to tear down the values of their own state which they are protecting, to get them out of the way. Reform, democracy and human rights are real. People really want them. But when people are talking about something else, but then told they are asking for these things, alarm bells should start ringing. That doesn’t happen because those in power have silenced the bells. Why? So if their scams are found out, they will be replaced by the only option their behaviour has left available – another generation of reformers, democracy promoters and selective human rights activists.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo was founded between approx. 1350-1375, and nominally survived until 1914. Its former lands now lie in northern Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Republic of Congo, and southern Gabon.

How do we know about the Kingdom of Kongo?

The first written record of Kongo was in 1483, after the Portuguese sailor Diogo Cao first visited the kingdom. The conversion of the kingdom to Christianity, its diplomatic contacts with Portugal, the Netherlands, Belgium, and the Vatican, as well as mercantile/trading links with everywhere from England to Brazil to Ming China means there are extensive written and artistic sources regarding the lives of Kongolese people and the politics, economy and diplomacy of the kingdom. Preserved oral history and traditional memory is another important source for post-1483 Kongolese history, and also provides information for the origins of the kingdom.

Why is the Kingdom of Kongo important?

The lives and experiences of millions of people

Between 1650-1700, the Kingdom of Kongo contained roughly 500,000 men, women and children - and some historians estimate that this reached up to 2 million. As of 2020, over 118 million people live in countries which held parts of the former Kingdom of Kongo (Gabon, DRC, Angola, Republic of the Congo) and whose history and politics have been shaped by it.

Urban history

The Kingdom of Kongo’s cities are super interesting/relevant for anyone into urban history, the history of urbanism and anyone who wants to know what happens when you cram thousands of people into tiny spaces!! Mbanza Kongo/Sao Salvador was the capital, abandoned during the civil war and now holding 145,000 people - and there are archaeological remains of several coastal cities that existed from the 16th century!

African archaeology

Its kind of difficult to access many Central African archaeological sites due to politics, conflict, funding etc etc. The Kingdom of Kongo has many archaeological remains - from cities to cemeteries to old churches, and with that we can uncover the remains of clothing, jewellery, crucifixes, food and even Ming pottery!

Global history

The Kingdom of Kongo participated in a globalising early modern and modern world. It probably began with the expansionist Nimi a Nzima (ruler of Mpemba Kasi) who conquered much of the south shore of the Congo River between 1350-1400. It did not just engage with the world through conquest of course. From 1483, the Kingdom of Kongo actively participated in the world of European trade and politics - sending ambassadors to Portugal, the Vatican and Brazil. It sent its princes to study in Lisbon, and merchants crossed back and forth into Portuguese (and briefly Dutch) Angola. Dutch Calvinists, Italian Capuchin missionaries and French colonists all met Kongolese kings, priests, nobles and traders. Archaeology shows its cities held Chinese, English, Dutch, Scandinavian and Portuguese pottery and jewellery. Kongolese people went out beyond the kingdom as diplomats, priests, merchants and slaves - and transformed the Atlantic world in Brazil, the USA and Haiti.

Global Christianity

The history of Christianity in Africa is not just a) Ethiopia and b) colonisation. The Kingdom of Kongo converted to Christianity through the form of a royal cult, willingly. Kongolese Christianity was dynamic and independent, drawing on indigenous, Portuguese and Italian influences to build something entirely new. Kongolese people resisted royal religious determination, producing movements such as Antonianism under strong female leaders such as Kimpa Vita. And Kongolese Christianity may have affected Afro-Brazilian and Haitian Christianity too.

Amazing art and sculpture

The Kingdom of Kongo produced super interesting art and sculpture, from brass crucifixes and religious imagery to stunning coin and regal designs, to beautiful architecture. We have Kongolese art from the 15th century right until its end, and the Kingdom of Kongo’s legacy is still relevant to Angolan and Congolese art through modern meditations on its past!

The slave trade and resistance to slavery

No one knows how many Kongolese people were enslaved in the Atlantic slave trade - nor the many more people who passed through the Kingdom of Kongo to the coast. At least 30,000 people were shipped to the Americas in the aftermath of the civil war. Kongolese Catholicism and politics seems to have influenced the 1739 Stono Revolt in the USA - which was fought by people born and raised in the Kongo. And Kongolese religion and politics seems to have influenced the Haitian Revolt - the only revolt that led to the birth of a free country by an enslaved people.

Colonialism and imperialism

The Kingdom of Kongo is no more. The reason for this is a combination of internal weakness due to a series of civil wars and a decline in the royal cult, and colonialism. In 1859, Pedro V became a formal vassal to Portugal in return for their military support in his battle for the throne. In 1914, Portugal finally “abolished” the Kingdom of Kongo. Parts of the Kingdom of Kongo came under French and Belgian imperial control too. How can a national identity and tradition get “abolished?” How could a kingdom get split up into different colonies and countries?

Central African politics

The last two questions are exactly what some people are asking. Bundu dia Kongo is a Kongo nationalist religious and political group founded in 1986 to unite the “Kongo people” into a Central African federation, and they draw on the history of the Kingdom of Kongo. Violent clashes with the DRC police have led to the deaths of several hundred people and they are banned in the country. Moreover some historians are arguing the importance of Kongo/Kongolese nationalism to DRC independence.

#black history#african history#kongo#congo#drc#angola#republic of congo#congolese#kikongo#central africa#west africa#africa#kingdom of kongo#history#early modern history#medieval history#world history#global history#19thcentury#art history#18th century#culture#archaeology#royal#academia#gabon#slavery#haiti#brazil#afro-brazilian

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Environmental History in US and Capitalism

This week, we read about the environmental history and movements in the United States. In addition, I discuss the interesting connection between economic profits with environmental progress and how we are shaped into the system we currently have.

The United States is split into four major eras of environmental movements. The first includes the Tribal era, where Native Americans occupied North America sustainably for over 10,000 years. The second is the frontier era between 1670 and 1870. This era includes the displacement of Native Americans by European settlers and clearing land for settlement. The US government then redistributes public land to private control, including timber companies, schools, railroads, and more. In the next era, Early Conservationists, from 1870 to 1930, citizens had already become alarmed at the astounding depletion of natural resources around them. However, little was done to improve the environment until Theodore Roosevelt became president. He designated many public and federal land to protect land and natural monuments. By the 1930s, the Great Depression hit, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to implement policies to recover our eroded soil. By the 1960s, Rachel Carson published The Silent Spring, which documents widespread pollution across the water, air, and wildlife. This ignited the beginning of an environmental movement in the US. Awareness and activism continued to spread about environmental protection, and we began to hear many familiar names. The US government created the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Energy was created to help grow independence from coal. Throughout the 1980s to the present, opposition began to grow amongst leaders of the coal, timber, oil industries, and more. Money was funded to destabilise support for environmental protection in which we saw Congress cut funding for various clean energy researches (Buren).

Interestingly, by 1870, groups of people in the US had already begun to see an alarming change in the country. I previously thought that the environmental movement was a relatively recent and new phenomenon. Despite being such a long movement, emissions are still reaching record levels, and global temperatures continue to rise, which is extremely pessimistic to see. However, environmental awareness is widespread, which is also a reason for optimism.

The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene, written by Simon L. Lewis and Mark A. Maslin, wrote partly about the beginning of the UK and globalisation in the modern age. The authors mention the profit-driven system initially started by the European colonists. They included an interesting excerpt about abolishing slavery in the western world. There was indeed moral outrage about the treatment of enslaved people; however, there was also an economic aspect to it. It became clear for plantation owners that paying workers at a low wage was cheaper than paying an upfront payment for an enslaved person. The owners would not need to provide food or a living place (Lewis and Maslin, 201-202). This is interesting in understanding how profits affected the past and how it affects us. It still rings true that industries continue to exploit scarce resources because it is more profitable for them. Renewable energy and other forms of environmental regulations cut their profits and they continue to exploit without worrying about the environment's future. A capitalist mode of our society will continue to clash with ethics and the planet's sustainability.

In addition, the authors mention how the complex adaptive system is closely related to a capitalist mode of living. In modern society, the environment adapts to the human changes to the system. For one, the negative feedback loop is when the increased output of a system hinders the further production by the system, while a positive feedback loop leads to an increase of a reaction. The positive feedback loop is self-reinforcing. Interestingly, the author mentions the switch from hunter-gatherers to an agricultural way of living is also a positive feedback loop because it increases the energy for humans. More people can live off a piece of land, and it becomes so widespread that it is the only way of living. Later, the switch from public land to private interests led to a capitalist society. People needed to lease land to feed themselves and produce food for the money. The tenants got rich from renting out lots of lands, and tenants had the incentive to increase productivity. This positive feedback loop leads to increases in scientific innovations and increased productivity for tenants. The authors mention how this first required a profit-driven mentality (Lewis and Maslin, 335-345). This is a fascinating take on the connection between the complex adaptive system and capitalist society. Indeed, the profit-driven mentality is a massive factor in the development of society. The change in design has also resulted in the positive feedback loop of our current environment. The release of carbon emissions leads to warming temperatures. The warming globe melts permafrost, releasing trapped carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Discussion Question: Will we ever be able to make drastic environmental regulations to industries without regard to economics? Rediscussing renewable energy, industries have begun widespread using clean energy when it has become profitable. It makes me wonder if we will always have to wait until certain policies become profitable for industries.

Word Count: 863

References:

Buren, John Van. Chapter : Supplements : Supplement 3: Environmental History of the United States. learn-us-east-1-prod-fleet02-xythos.content.blackboardcdn.com/5fd3b7d419aac/8077468?X-Blackboard-Expiration=1644894000000&X-Blackboard-Signature=NSATNviJLn%2F2IRVS4Nrnr20B2xZ7fG%2BUJ5%2BJyfERRS4%3D&X-Blackboard-Client-Id=100403&response-cache-control=private%2C%20max-age%3D21600&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%2A%3DUTF-8%27%27US%2520Evironmental%2520History%25201.pdf&response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2luX2VjEFAaCXVzLWVhc3QtMSJHMEUCIFlwswPsO%2BJHUzd9URPXmbT4oMOXvkQh8QKhVuUrClpbAiEApwy7vtcBGzZp5YtAkLGYfdWYMdaa%2B%2BqNj1jt5HtTZDQqgwQImP%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2F%2FARACGgw2MzU1Njc5MjQxODMiDPQo6MRwgm528xOgEirXAyzOELrs9IaWipOhABg%2FgN0Q%2F1%2BRIKtirn03SX1i9WXvRTz8rk%2Bk7XWygM1%2BKnP6MWhg8HBkE3Gt8aFucRy9d9YwseLFqc4%2BUU%2BS1VLfI8OO9sNLqE8rBnkfD4Kxjrz3VNrSpRtYv%2FK7RTM3pBHlKKCwCBjsXK1LG%2B7zkUb2n3dHdquZj6%2F23Io%2B96ALx6cxYFMhYekVdPj%2FC7IpO0%2Fwm0lXJ1rznaV3Az6CiMzpDvbvFz9lyfusfcHHc3AHRQpEkgTVhIaaTmVNejAlKpZak3yhXpTVaP3XHKs5tiKD25c8TZPTBk%2F4V0azBot02s%2FvFxcKfPyNpMy8oHQMX5Ba%2FOLX1qrhmBt84Fy2nL%2FsgpbtEY4OUBiwRNkpBH13i1R6fZcc8QJ8KH368bcP8PfoCkVpQ5F6cdlgkLaCzdGeFiTOsfEvottz6XA80gJWIyn7egi%2B%2FcAvX%2FtlrIx6JwhPMx3bg%2BfjhomUAnM6rAsdAAQ05XUSQGMqaguNW4SnbRapcWeF7YpKFF2%2FGUJeoSHDvhoNK%2B9ipCWzYjBvTKtgNesocJ1Utl6N6a69PGVz8%2FgAKqU%2BlujDHWCGAxxoZy2tRv%2BydTs7KHxXfo1PIfUdFVQ%2BJpXZK%2ByAZjCAxauQBjqlAT9tYNfZSCIMmFDwL8xpspBU4dS4tDDo4N%2BIHlDXvhCjgdHfG7pA%2FDmIscREz33by8oFYQN9qoiDp%2B6v5%2BZgdQXGst3jIAI%2FdV%2B8%2FU5J9lhQ9nf2oj%2F%2FHoddg2HJIHzWBjVfObW0LWPvp5HIFh%2FDSp6P%2Fk7Ew6vihUTn3z4MEezcVArZrg3Il2EmO4kB6KtWdqGy7WhdOo5Db%2BC573ktT%2FOUoK%2Fu%2FA%3D%3D&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Date=20220214T210000Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=21600&X-Amz-Credential=ASIAZH6WM4PL37AP6J4Y%2F20220214%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Signature=ef0a4d9c87eb2446b73a59199c8ca4dd1b16424323905e8d75ebb64028f2c3f8.

Lewis, Simon L, and Mark A. Maslin. HUMAN PLANET : How We Created the Anthropocene. S.L., Yale University Press, 2022, p. 201-202, 335-345.

0 notes

Text

“Whatever remains of the old Catholic nationalist regime will soon be gone completely but our intellectual conformism and deference to the one that has replaced it remains. Ireland now enters a phase in which the restrictions and social taboos of our parents and grandparents generation have been lifted but access to the basic material necessities of life such as housing and stable employment will likely decline.

The “shared space” that represents our having transcended the bad old days of nationalism is also perfectly conducive to our new role as obedient colonial subjects to be ruled from Silicon Valley rather than Westminster. The guiding force behind our economic inequality is no longer parish-pump parochialism, the church or nationalism but a system based on a globalised, financialised and speculative economic order.

For those who want neither a return to the past offered by the right or the liberal individualism offered by the permitted American model of the left, a feat of the imagination will be required to offer an alternative vision. Ireland could instead, for example, draw from our own unique radical traditions to fight for the rights of those who do not own property. Instead of lazily adopting the liberal cosmopolitanism of Silicon Valley, we could look out to the great cultures of the world for inspiration, to those elements that have withstood the marketisation and Americanisation of everything.”

Angela Nagle - How liberalism is enslaving Ireland as a colony of Silicon Valley

I thought this was an interesting piece, although not without its problems. An issue I had with Kill All Normies - one of the theses of which I might state as being that the post-’68 left emphasis on ‘transgression’ as a political value has backfired, creating a new reactionary force - is that it seemed to hold to the idea of a materialist left that could dispense with radical questions about identity, or at least adopt some ‘common-sense’ position of feminism and race and then get on with the important business of building socialism. This piece, with its similar needling of liberals - “Ireland is busy collectively retweeting itself for enthusiastically coming into line with long-standing progressive norms elsewhere in Europe” - echoes that idea for me. Nevermind that most of the people on the left in Ireland I see vocally campaigning for social issues like abortion and gender equality are equally as vocal about material issues like housing and employment.

That said, their rhetorical equality, and even equal prominence of campaigning efforts, doesn’t necessarily solve a contradication that exists between the welcome broader mainstream support of socially liberal individualism, and the dire effects of economic individualism on the environment and human society. Straw-manning a particular side doesn’t help either, but there is a problem that needs to be addressed.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

LUBAINA HIMID – LOST THREADS British Textile Biennial 1-31 October 2021, Gawthorpe Hall, Padiham

“Cascading through the structure of Gawthorpe Hall’s Great Barn, 400 metres of Dutch Wax fabric reflect the movement of oceans and rivers that have been used to transport cotton across the planet and over centuries. Waterways historically carried raw cotton, spun yarn, and woven textiles from continent to continent, as well as enslaved people from Africa to pick raw cotton in the southern states of America or workers who migrated from South Asia to operate looms here in East Lancashire.

In this major new installation, Turner-prize winning artist, Lubaina Himid, continues her life-long exploration into the making of clothing and histories of colonisation, female labour, migration and globalisation. Although recognised as ‘African’ cloth, these textiles have a complex lineage and identity that reflects an historic and continuing flow of labour, trade and money.

The vibrantly coloured and intricately patterned fabric in the installation dominates West African markets and is now globally recognised as quintessentially “African” although the cloth was originally forged by Dutch colonial companies attempting to mechanically reproduce handmade Javanese batik cloth in Holland. When this failed to take off in Southeast Asia, Dutch traders began to sell the cloth in West African markets. The patterns were modified to fit local tastes and quickly became popular, ultimately becoming an essential everyday consumer good. However, today the majority of Dutch designs available on African markets are low-cost reproductions made in China, such as the fabric used in Lost Threads which exposes the role of colonisation in the formation of cultural stereotypes.”

0 notes

Text

Episode 7 - Tsing part 2

Episode link; https://open.spotify.com/episode/6pzJixj6sJpBufwtzzvYe6?si=a6ff2fe3534e4643

“I’m not proposing a return to the Stone Age. My intent is not reactionary, nor even conservative, but simply subversive. It seems that the utopian imagination is trapped, like capitalism and industrialism and the human population, in a one-way future consisting only of growth. All I'm trying to do is figure out how to put a pig on the tracks.”

John

We are in the US, in the forests which hem the sides of the Cascade mountains. It’s here where those mushrooms I bought in Tokyo grew, or some of them at least. And where you’ll find their pickers. I headed to the forest services “big camp” for mushroom pickers but it was deserted, they must all be out foraging. So I've set up my desk on the edge of the camp looking into the forest. I must say it’s not how I imagined, the ground is dry and rocky, nothing is growing except thin sticks of Longpole pine. There are hardly any plants growing near the ground, not even grass and when I reached down to touch the earth, you know to connect with the forest, sharp pumice shards cut my fingers. I figured maybe it was best just to sit at my desk and wait it out until someone arrives. I sort of hoped I’d be able to sell my mushroom back to someone here, you know, recoup some of my money but looks like that won’t work out…

So let’s go over a little history shall we;

In the mid seventies Lao and Vietnamese communist soldiers captured Long Tieng in the Highlands of Laos. This had been the site of a CIA supported Hmong army which had been fighting the communists for fifteen years. In the wake of the capture thousands of Hmong fled on foot across the Mekong river into Thailand. In the mid to late 80s following pressure from the Thai government, the US increased its yearly resettlement quota to 8000 and attracted by the promise of American freedom or just tired of living in a refugee camp many took up the offer. However, many Hmong were disappointed. Far from the freedom they imagined they were crowded into tiny urban apartments.

In the early 90s some of these refugees returned to the forests attempting to recreate the freedom of their collective memories. At that time pickers had camped wherever they pleased but after complaints from white pickers the forest service built this camp-site. These campsites came to mimic the structure of those refugee camps in Thailand where many of the pickers had spent more than a decade before their arrival in the US.

Pickers segregated themselves into ethnic groups: On one end, Mien and Hmong; half a mile away, Lao and then beyond them Khmer; in an isolated hollow, way back, were a few white pickers.

Tsing comments that sitting in the camp “eating the food, listening to the music, and observing the material culture, I thought I was in the hills of south east asia, not the forest of Oregon.”

What they created here in the forest was a kind of hybrid only possible in the globalised world we’ve created. East Asian refugees, of a war supported by the CIA, recreating a Thai camp, in the mountain forests of Oregan to remind them of the highlands Laos, picking mushrooms for sale on the Japanese market.

There is a lot of excitement about globalism, and rightly so - in some ways. The world is smaller than it’s ever been and we can experience so much more than our ancestors could imagine. Look at this podcast, we’ve flown all over the world in a matter of weeks. But, Tsing points out that in the idealised form of Globalism, the ability to overcome boundaries and restrictions will benefit everyone equally.

The idea is this; If supply chains can make cheaper products, like we discussed last time, that means cheaper products for everyone! Right?

Well, we already kinda know the answer to that one right? As we’ve seen, there are downsides to supply chains and globalism which can lead to worse material conditions for people all along the chain. We talked about some of the people exploited by this system last episode, like enslaved people or sweat-shop workers. We touched on other versions of work exploitation too, like zero hours contracts. But what Tsing saw in the forests of Oregon was people who had fallen through the cracks of this system entirely.

The Hmong refugees are one example. But in a peculiar twist, another group who live alongside the Hmong in Oregon’s forests are Vietnam veterans. Returning from the war with PTSD and limited social safety nets several veterans retreated to the forest, where they could escape urban life and it’s multitude triggers. However, living alongside refugees from the same war does not mean that there is harmony in the forest. White pickers tend to keep their distance. In describing one such veteran Tsing writes that “Geoff had serves a long and difficult tour in Vietnam. Once, his group had jumped from a helicopter into an ambush. Many of the men were killed, and Geoff was shot through the neck but miraculously survived.” But the war still haunted Geoff. One day whilst picking he had been surprised by a group of Cambodian mushroom pickers, Geoff opened fire.

Another picker Tsing met was Lao-Su who worked in a Wal-Mart warehouse before moving to the forest and picking mushrooms. At Walmart he made 11.50 an hour. To get that rate he had to forgo medical benefits. So when he injured his back and could not afford medical costs he handed in his notice. Despite only being in season two months out of the year, he still earned more from mushrooms than he did at Walmart.

So huddled in the forest we have refugees, war veterans and people who have fallen out of wage work. Tsing says they are “haunted by labour.” But maybe it’s more accurate to say they are all haunted by globalism.

Okay - okay it’s getting a little complicated. I’m going to go for a little walk in the woods. That’s participant observation right? Maybe I'll find a mushroom, or a picker? Or Anna Tsing and she can explain what the fuck she means.

One cold October night in the late 1990s, three Hmong American matsutake pickers huddled in their tent. Shivering, they brought their gas cooking stove inside to provide a little warmth. They went to sleep with the stove on. It went out the next morning all three were dead, asphyxiated by the fumes. Their deaths left the camp ground vulnerable, haunted by their ghosts. Ghosts can paralyze you, taking away your ability to move or speak. The Hmong pickers moved away, and the others soon moved too.

The U.S. Forest service did not know about the ghosts. They wanted to rationalize the pickers camping area, to make it accessible to police and emergency services, and easier for the campground hosts to enforce rules and fees.

The forest Service’s idea about emergency access did not work out as imagined. A few years later, someone called emergency services on behalf of a critically wounded picker. Regulations aimed only at the mushroom camp required the ambulance to wait for police escort before entering. The ambulance waited for hours. When the police finally showed up, the man was dead. Emergency access had not been limited by terrain but by discrimination.

This man, too, left a dangerous ghost, and no one slept near his campsite except Oscar, a white man and one of the few local residents to seek out southeast asians, who did it once, drunk, on a dare. Oscar’s success in getting through the night led him to try picking mushrooms on a nearby mountain, sacred to local Native Americans and the home of their ghosts. But the Southeast Asians I knew stated away from the mountain. They knew about ghosts.

“Open ticket is haunted by many ghosts: Not only the “green” ghosts of pickers who died untimely deaths; not only the Native American communities removed by U.S. laws and armies; not only the stumps of great trees cut down by reckless loggers, never to be replaced; not only the haunting memories of war that will not seem to go away; but also the ghostly appearance of forms of power.

Matsutake picking is not the city, although haunted by it. Picking is not labour-or even “work.” One picker explained “work” means obeying your boss, doing what he tells you to do. In contrast, matsutake picking is “searching.” It is looking for your fortune, not doing your job.”

So I said, in the last episode, that Tsing saw a parallel between matsutake mushrooms and the people who picked them in the forests of Oregon. If you remember Matsutake tends to grow on the sites of capitalist ruin, like the site of a nuclear explosion or deforestation. They survive by creating fruitful relationships with their surroundings. Likewise, Matsutake pickers are victims of capitalist ruins whether it be war or just crappy jobs. But they have survived by creating a fruitful relationship with the forest and the mushrooms which grow there.

Part of this survival, as Tsing alludes to at the end of the extract we just heard, is the rejection of labour. Picking mushrooms is not work, mushrooms, in the hands of these pickers are not commodities, they are trophies. A demonstration of their skill and ability to navigate the forest. Tsing describes it as a performance which doesn’t aim to exorcise the ghosts but to navigate them with defiance and flair.

Okay - but here is a problem. Is that Freedom not reliant on capitalist systems to survive? These mushrooms end up in the capitalist system right? We can buy them in a market in Japan for a price set by market forces. Tsing calls this “salvage accumulation.” Basically, imagine you steal a truck full of DVD players like in Fast and Furious then you need to sell them. So you use a "fence", basically an intermediary, to sell them to umm lets call them Ballmart so I don’t get sued. (except it's not ball, it's wall with one less L)

Ballmart, slap a barcode on it and it becomes inventory. They're happy because they get cheap DVD players. And in turn expunge their history. "What? These DVD players?" Ballmart says. “We bought them from a third party who we outsource to for our DVD player purchases.” Hey look, it's those pesky supply chains again.

The stated aims of Dominic Toretto and co. is family, freedom and ice cold Coronas. They have rejected capitalist wage labour in favour of being Fast, Furious and Free.

But Ballmart has "translated" their freedom into capitalist logic using supply chains and barcodes. Ballmart profits within the system, Supply chains mean they can claim ignorance of the DVD player theft. Whilst Dom and co risk prison. SO are Dom and his crew REALLY outside capitalism? Are they really free? Or is the system just profiting off them and exploiting them?

I’m so sorry to the listeners who haven’t seen fast and furious that analogy is useless to you. This isn’t just a hypothetical. Tsing says that Ballmart, and similar companies do this all the time.

It happens here in Oregon too. Pickers sell their mushrooms in a kind of reverse auction process. On any given evening the price of matsutake may easily shift by $10 per pound or more. Over the years the price is even more volatile, between 2004 and 2008 prices shifted from between $2 per pound and 60. Because of these wild shifts, pickers and buyers use a system called “Open Ticket.” In this system a picker may return to the buyer for the difference between the original price paid and a higher price offered on the same night.

This creates just ridiculous scenes at sales. Here is Tsing describing it. Every buyer “surveys the buying field like a general on an old-fashioned battlefield, his phone, like a field radio, constantly at his ear. He sends out spies. He must react quickly. If he raises the price at the right time, his buyers will get the best mushrooms. Better yet, he might push a competitor to raise the price too high, forcing him to buy too many mushrooms, and if it goes really right, to shut down for a few days.There will be rude laughter for days, fuel for another round of calling each other liars - and yet no one goes out of business despite all these efforts. This is the performance of competition - not a necessity of business. The point is the drama.” Even just sorting the mushrooms here is a performance, an eye-catching, rapid fire dance of the arms with legs held still. The original TikTok dancers.

Then something weird happens. The mushrooms are sorted again. This is particularly odd because buyers in Oregon are master sorters. Sorting creates the prowess of buyers; it is an expression of their deep connection with the mushrooms. Stranger yet, the new sorters are casual labourers with no interest in mushrooms at all. These are workers in the classic sense of the term: alienated labour without interest in the product. It is precisely because they have no knowledge or interest in how the mushrooms got there that they are able to purify them as inventory. The freedom that brought those mushrooms into the warehouse is erased in this new assessment exercise. Now the mushrooms are only goods, sorted by maturity or size.

The same way, Ballmart erased Dominic Torreto’s sick heist with a barcode which transformed the DVD players from the fruits of an exciting car based crime. The freedom of pickers is reliant on globalism, on capitalism. So are they really free? Or are they just performing freedom? After all that performance, the mushrooms still just become a commodity and Japanese importers sort of just put up with this idiosyncratic behaviour, saying “if this is what brings in the goods, it should be encouraged.”

And this sort of defiance of but reliance on capitalism is also present in Matsutake themselves right? They flourish only because capitalist extraction destroys the landscape. They thrive in a “value” sense because of capitalistic structures.

Tsing says capitalism is often described as a giant bulldozer flattening the earth to its specifications. Yet much of the world economy takes place on the fringes of the economy, like with these mushroom pickers in a forest, or women in sweatshops, or gangs, or made by enslaved people. She says these people “work the edge.”