#egypt 1798

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Just a quick update as I found the dates for the two letters seized by the Brits, as cited by Frédéric Masson in "Joséphine répudiée":

Eugène informs his mother on 6 Thermidor, from Giseh (outside of Cairo) - this would be 24 July 1798 - that he has overheard Julien, Junot and Berthier talking to Napoleon about Josephine and Hippolyte Charles. One day later Napoleon writes to Joseph that "the veil is completely torn away".

Eugène's letter in its entirety (or at least as much as is quoted by Masson):

Bonaparte has seemed very sad for the last five days, and this is the result of a conversation he had with Julien, Junot and even Berthier; he was more affected than I thought he would be by these conversations. All the words I have heard come back to the fact that Charles came in your carriage as far as three posts from Paris, that you saw him in Paris, that you went to the Italians with him in the fourth box, that he gave you your little dog, that even at the moment he is close to you; that, in jumbled words, is all I have been able to hear. You can be sure, Mama, that I don't believe this, but what is certain is that the General is very upset. However, he is redoubling his kindness to me. By his actions, he seems to be saying that children are not responsible for their mother's faults. But your son likes to believe all this gossip invented by your enemies. He loves you no less and wants to kiss you no less. I hope that when you come, all will be forgotten.

The end of the letter is only quoted in a footnote, so there might be something missing:

We've had a lot to endure. We have crossed deserts. We have suffered thirst, hunger and heat, but fortunately we have arrived in Cairo victorious. For six weeks there has been no news, no letters from you, from my sister, from anyone. You mustn't forget us, Mama, you must think of your children. Adieu, believe that your son would sacrifice his happiness for yours a thousand times over. E. Beauharnais

So, according to Eugène it was Julien, Junot and Berthier who had talked to Napoleon. But as Eugène mentions things happening "at the moment", this seems to refer to events after the army had left for Egypt? How did they know? Who had informed them? I always figured there was little to no contact between the French in Egypt and France? But Eugène's disappointment at not receiving any letters from mother and sister also seems to indicate that there would have been a way for them to write.

And if Napoleon already learned about Josephine's affair in July 1798, why was he so shocked in February 1799, during the march into Syria (date according to Bourrienne)?

Wondering about how Eugène may have felt about Junot, I ended with another question and thought maybe you would know: How did Junot feel about Napoleon's marriage to Josephine? As he was quite possessive about Napoleon, were there any signs of jealousy? If I remember correctly, Junot was the one who claimed that Josephine had slept with Hippolyte Charles during the trip to Milan in 1796?

Hi! Thanks for the ask! That's a very interesting question! One which is hard to answer because we don't have any indication of Junot's own personal feelings towards Josephine.

The lack of information does steer me towards ambivalence perhaps? Junot was simply fine with Josephine because Napoleon loved her so he respected her all the same. However, it could be that Junot was good at hiding his contempt behind a polite facade. For all his explosive emotions and lack of secrecy involving his own indiscretions, Junot could play the part of a flatterer. Marbot alludes to this during the third invasion of Portugal in 1810 when Junot was gracious towards Masséna's mistress. Later on, Junot (and the other generals) would complain about this woman and Marbot would ask why the about face? Junot laughed, replying:

Because an old hussar like me has his games sometimes, that is no reason for Masséna to imitate them. Besides, I must stand by my colleagues.

So perhaps Junot wasn't particularly fond of Josephine and was just able to not express it in front of people.

Another point is that Laure Junot talks about how Junot had seduced one of Josephine's ladies in waiting while accompanying her to join Napoleon in Milan during the first Italian campaign of 1796. Her name was Louise (no surname mentioned) and Junot, no surprises there, was not discreet:

Madame Bonaparte from that moment [of the trip] evinced some degree of ill-humor toward Junot, and complained with singular warmth of the want of respect which he had shown her, in making love to her femme de chambre before her face.

Parentheses by me.

So perhaps it's not that Junot disliked Josephine from the onset but it was Junot's own behaviour that caused Josephine to not have a high opinion of Junot, and her complaints did not encourage him to be too nice to her from then on.

Junot was pretty upfront with the people he disliked. He hated Clarke and wasn't overly fond of Fouché. However, Junot was someone who could laugh and play along at even the most absurd of things so actually there may be a bit of both in the truth -- he outwardly respected Josephine as the wife of his dear General Bonaparte but he wasn't overly magnanimous towards her because of her dislike over something he did.

The main source of the story of Junot telling Napoleon about Josephine's infidelities comes from Bourrienne who apparently on the 11th February 1799, decided to come out and tell him about the affair with Hippolyte Charles, accompanied with written evidence too! Bourrienne also says to have witnessed this meeting in person.

However, correspondence puts Junot at the Suez at the time so it was probably likely that Napoleon heard the rumours from someone else (we don't know who) and Junot had to reluctantly corroborate the information. Why reluctantly? Well, Laure completely denies that Junot would ever talk about this, and given the reliability of her accounts, there may be an inkling of truth but we can't say for sure. It's possible that Junot didn't outright say anything but he did confirm what he knew, albeit with reluctance. That's probably how the idea that Junot directly told Napoleon about the affair came about.

Ultimately, this is one of those times in Junot's life that would be totally shrouded in speculation unless we unearth more evidence. I will say though, that maybe looking at Marmont's own musings (with hindsight though) on Josephine's effect on Napoleon at the time of their wedding could give a bit of a clue to how Junot also felt about Josephine:

It was, it seems, his first love, and he experienced it with all the intensity of his nature...What is incredibly, and yet, absolutely true, is that Bonaparte's vanity was flattered.

A woman who knew how to make a man feel like the king of the world. Too far-fetched of an analysis, perhaps? But they were very good friends and might have had similar opinions. It's probably the closest we will get to an impression.

duchesse d’Abrantès, Laure Junot. Memoirs Of The Emperor Napoleon – From Ajaccio To Waterloo, As Soldier, Emperor And Husband – Vol. I (p. 312). Wagram Press.

de Marbot, Général de Division, Baron Jean Baptiste Antoine Marcelin. The Memoirs of Baron de Marbot - late Lieutenant General in the French Army. Vol. II. Wagram Press.

#on a sidenote#i hate masson's judgemental tone#with a passion#yes between his mum and a stepfather eugene would probably choose to be loyal to his mother#josephine bonaparte#eugene de beauharnais#egypt 1798#hippolyte charles

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 History Lessons Through Souvenir Items from the Trip: Discover Egypt

On a transit through the man-made Suez Canal of Egypt, we had a mini-bazaar of souvenir items brought by the Suez Canal crew. It was a good opportunity for us to buy souvenirs and some tools that we could use for the journey. From refrigerator magnets, table mementos, papyrus wall arts and fishing paraphernalia, the mini-bazaar came with everything Egyptian. This post is about the history…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

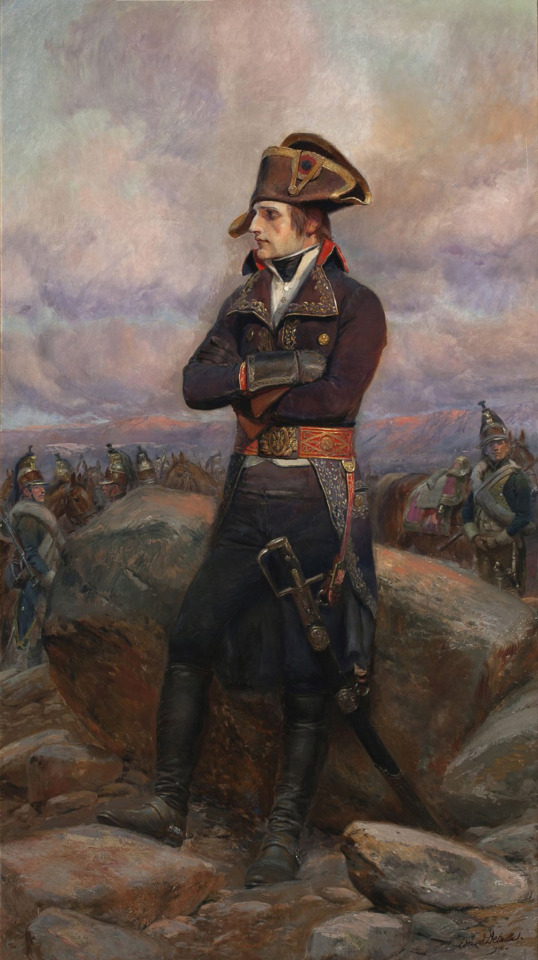

Bonaparte in Egypt, 1798 by Édouard Detaille

#napoléon#napoleon#egypt#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#art#portrait#édouard detaille#egyptian campaign#france#french#french revolutionary wars#napoleonic#history#bonaparte#europe#european#egyptian#campaign

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Combat of the Giaour and Hassan

Artist: Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798–1863)

Date: 1826

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

Description

This colorful scene was inspired by a poem from Lord Byron’s “Oriental tales,” a popular series of romances. Both the poem and the painting are examples of 19th-century Europeans’ interest in fantastical and often violent depictions of Middle Eastern, North African, and Asian cultures, which reinforced colonialist aims. Although Eugène Delacroix did not visit North Africa until 1832, he began painting Orientalist subjects early on in his career. The artist’s French audience would have been receptive to his choice of jewel-like colors to describe the shimmering, gold-braided vest and billowing robes of the central figures. Far from accurately representing the attire of the 17th-century combatants of Byron’s poem, Delacroix drew upon styles worn by the Turko-Egyptian Mameluke warriors during Napoleon Bonaparte’s military campaign in Egypt in 1798–99.

#painting#literary scene#lord byron's oriental tales#landscape#orientalism#oil on canvas#artwork#fine art#oil painting#turkish costume#battle scene#narrative art#horses#art and literature#poetry#french culture#french art#eugene delacroix#french painter#european art#19th century painting#art institute of chicago

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

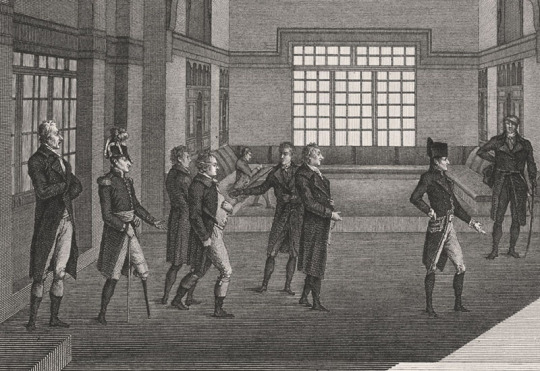

Napoleon's Campaign in Egypt and Syria

The French Expedition to Egypt and Syria (1798-1801), led by Napoleon Bonaparte, aimed to establish a French colony in Egypt and to threaten British possessions in India. Despite initial French victories, the campaign ultimately ended in failure, and Egypt remained under Ottoman control. The expedition also led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and the birth of modern Egyptology.

Continue reading...

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

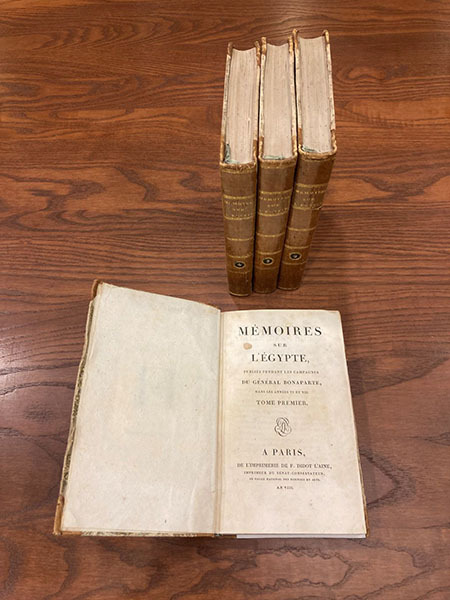

The Institute of Egypt – Scientist of the Day

When Napoleon invaded Egypt in July of 1798 with 54,000 soldiers and sailors, his immediate problem was gaining control of Cairo, which he effectively did with the Battle of the Pyramids on July 21.

read more...

#Institute of Egypt#Napoleon#histsci#histSTM#18th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

French 'Sabre a l'Orientale' cavalry officers' sword

The 'Sabre a l'Orientale' (often called mameluke swords in English) gained popularity with fashionable officers during the French campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798 to 1801).

Initially, these swords would have been acquired in battle either as a trophy, from being given as a token of respect by allies, or from a surrendering foe.

However, as the fashion spread throughout Europe, local sword makers and cutlers began to produce their own interpretations of the style, such as the regulation dress sabres of British Lancers.

This sword style remains in service today as the British 1831 Pattern General Officers sword and US Marine Corps Officer dress sword.

My sword likely dates from 1810 to 1830 and caught my interest because it features an Eastern-produced shamshir blade mounted in a European-made mameluke-style hilt with cow or buffalo horn grip scales. The sword is plain and functional without the ornamentation typically found on swords belonging to senior officers. Going by the style of scabbard drag, this sword originally belonged to a French cavalry officer.

Stats: Overall Length - 950 mm Blade Length - 805 mm Curve - 75 mm Point of Balance - 1730 mm Grip Length - 125 mm Inside Grip Length - 94 mm Weight - 920 grams

#sabre#sword#sabres#swords#antiques#military antiques#French swords#Mameluke#napoleonic wars#mamaluke sabre#Sabre a l'orientale

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egypte, Le Caire, les pyramides, 21/07/1798, 3029 morts. © Jacques Sierpinski

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie known as Thomas-Alexandre Dumas; 25 March 1762 – 26 February 1806) was a French general, from the French colony of Saint-Domingue, in Revolutionary France.

Along with his French contemporary Joseph Serrant and other notable brothers in arms in the French Army Toussaint Louverture from Saint-Domingue, Abram Petrovich Gannibal from Imperial Russia and Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski from Poland, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas is notable as a man of African descent (in Dumas's case, through his mother) leading European troops as a general officer. All four commanded as officers in the French Army and apart from Gannibal, who was only captain and engineer-sapper in the Army of Louis XV during his formative years, they all gained their general ranks in the French Army, about four decades after Gannibal had done the same in Russia. Yet Dumas was the first person of color in the French military to become brigadier general, divisional general, and general-in-chief of a French army.

Born in Saint-Domingue, Thomas-Alexandre was the son of Marquis Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie, a French nobleman, and of Marie-Cessette Dumas, an enslaved woman of African descent. He was born into slavery because of his mother's status, but his father took him to France in 1776 and had him educated. Slavery had been illegal in metropolitan France since 1315 and thus any slave would be freed de facto by being in France. His father helped him enter the French military.

Dumas played a large role in the French Revolutionary Wars. Having entered the military in 1786 at age 24 as a private, by age 31 he commanded 53,000 troops as the General-in-Chief of the French Army of the Alps. Dumas's victory in opening the high Alpine passes in 1794 enabled the French to initiate their Second Italian Campaign against the Austrian Empire. During the battles in Italy, Austrian troops nicknamed Dumas the Schwarzer Teufel ("African Devil", Diable Noir in French) in 1797. The French—notably Napoleon—nicknamed him "the Horatius Cocles of the Tyrol" (after a hero who had saved ancient Rome) for defeating a squadron of enemy troops at a bridge over the Eisack River in Clausen (today Klausen, or Chiusa, Italy) in March 1797.

Dumas participated in the French attempt to conquer Egypt and the Levant during the Expédition d’Égypte of 1798-1801 when he was a commander of the French cavalry forces. On the march from Alexandria to Cairo, he clashed verbally with the Expedition's supreme commander Napoleon Bonaparte, under whom he had served in the Italian campaigns. In March 1799, Dumas left Egypt on an unsound vessel, which was forced to run aground in the southern Italian Kingdom of Naples, where he was taken prisoner and thrown into a dungeon. He languished there until the spring of 1801.

Returning to France after his release, he and his wife had a son, Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), who would become one of France's most widely-read authors. The son's most famous literary characters were inspired by his father

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#brownskin#thomas alexandre dumas#french

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

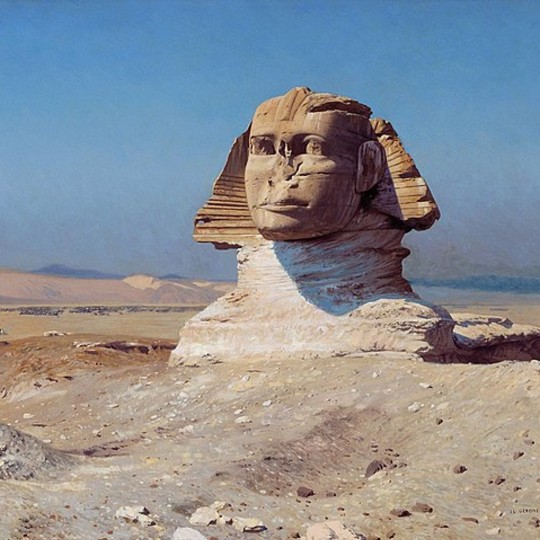

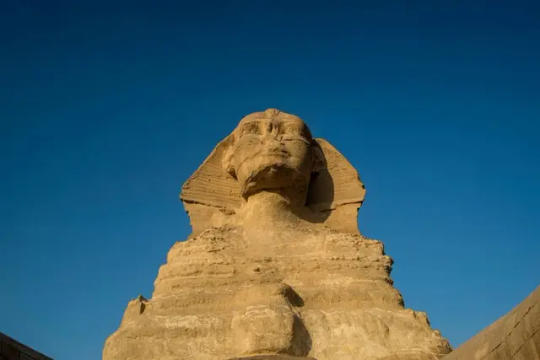

The Hunt: What Happened to the Great Sphinx’s Nose?

The mystery of the Egyptian statue's missing nose has fascinated people for centuries.

Much like the desert winds that perhaps helped shape it, conspiracy theories swirl around the Great Sphinx guarding the Giza plateau—especially regarding how the winged lion’s human head lost its nose. One enduring hypothesis blames Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops for blowing the snout off during target practice. While that conspiracy’s long-debunked, it persists in popular culture. Director Ridley Scott knowingly depicted the myth in last year’s Napoleon biopic, without sacrificing any of his film’s critical acclaim. However, Egypt’s Dr. Zahi Hawass told Britannica, “We have, really, to say to everyone that Napoleon Bonaparte has nothing to do with destroying the Sphinx’s nose.”

Napoleon’s 1798 battle didn’t even take place on the Giza plateau, but 10 miles north at Imbabah. Some theories have posited that storms and earthquakes shook the Sphinx’s nose from its face. Others squabble over which regional conflict (if not Napoleon’s Battle of the Pyramids) led to the nose’s destruction. In 1990, J.P. Lepre noted that “the figure was used as a target for the guns of the Mamluks,” who were actually Napoleon’s opponents.

The French emperor did, however, lay eyes on the Sphinx’s face when he arrived in Giza, with many soldiers, painters, and engravers in tow. “Thousands of years of history are looking down upon us,” he reportedly exclaimed beneath the monument’s gaze. Napoleon didn’t respect borders, but he did respect history. The Waterloo Association called the lingering accusations against him “particularly unjust because the French general brought with him a large group of ‘savants’ to conduct the first scientific study of Egypt and its antiquities.” The resulting Orientalist survey ignited an Egyptian fervor back in Europe.

Primary materials prove the nose removal predated Napoleon, too. Danish naval captain Frederic Louis Norden’s sketch from 1738 depicts the Sphinx without its central facial feature. What’s more, French naturalist Dr. Pierre Belon visited the Sphinx in 1546, writing that it had sustained damage and “no longer [had] the stamp of grace and beauty so admired by Abdel Latif in 1200”.

Medieval Arab scholars such as al-Maqrīzī pin the damage on Muhammed Sa’im al-Dahr, a 12th-century Sufi Muslim from a respected Cairo convent, who was allegedly angry that peasants used the Sphinx to entreat Abul Hol (the Arabic name for the sphinx) into helping their harvests. Removing an idol’s nose was an accepted method to suffocate spirits inside. Still, the details remain up for debate. Hawass believes that al-Dahr acted alone. Others claim he hired men to desecrate the Sphinx. Most experts, however, agree the great statue’s nose came off with a chisel. It is also generally accepted that al-Darhr’s actions got him killed by angry villagers. Sadly, the nose itself has likely crumbled into the desert.

By Vittoria Benzine.

#the sphinx#The Hunt: What Happened to the Great Sphinx’s Nose?#Giza Plateau#sculpture#statue#pharaoh Khafre#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian gods#egyptian pharaoh#egyptian mythology#egyptian art#ancient art

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonaparte in Egypt, 21st July, 1798 'Soldiers! Fifty centuries look down upon you from the summit of the pyramids'

by Richard Caton Woodville Jr.

#napoléon bonaparte#napoleon bonaparte#art#richard caton woodville jr.#pyramids#egypt#egyptian campaign#france#french#battle of the pyramids#french republic#french revolutionary wars#napoleonic#napoleon#bonaparte#soldiers#europe#history#european#egyptian#campaign#ancient egypt#pyramid#desert#mamluks#ottoman empire#louis desaix#jacques menou#napoléon

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leeches were largely popular in the medical field during the Victorian era both in Europe (primarily England and France) and America. The 19th century saw progression of the academic study of leeches as used in medicine that was conducted prior and laid basis for the modern application of anticoagulant in medical practice.

At the time, many famous Englishmen found leeches fascinating: zoologist Arthur Everett Shipley, for instance, wrote papers marveling at the beauty and functionality of a leech. This fascination often grew personal. Lord Thomas Erskine, a lawyer, underwent a successful bloodletting, afterwards taking with him two leeches; later naming them Home and Clina. According to the memoirs of Sir Sam Romilly, Erskine's friend, he took great care of making sure the leeches "knew him".

In France, the obsession with leeches took drastic turns as well. François-Joseph-Victor Broussais, a notable surgeon of Napoleon's army, was known to possess a certain infatuation with leeches.

Leeches were in growingly high demand in the 19th century Europe. France imported leeches in terrific quantities equating up to dozens of millions a year.

Overall, bloodletting for medicinal purposes is not strictly unique to the 19th century Europe. Like many other medical methods, it has its roots in Ancient Egypt and Greece where bloodletting via cutting veins was often practiced by the followers of the method described in the Hippocratic collection of the 5th century BC. The medicinal use of leeches dates back to 1500 BC and is not a recent invention. However, it is only in 1884 that Haycraft learned why leeches are so efficient in bloodletting: their saliva contains an anticoagulant hirudin (hence hirudotherapy). These observations are listed in Haycraft's work, On the Action of a Secretion Obtained from the Medicinal Leech on the Coagulation of the Blood. For this property, leeches are still in high medicinal demand.

During the Victorian era, leeches were used for all kinds of medical treatment: from headaches to hemorrhoids, from fatigue to nymphomania. Sir William Henry, for example, writes that bloodletting is far beyond any other medical treatment in helping many diseases.

Albeit, the effectiveness of such treatment is a matter of much questioning as often leeching only weakened the fragile state of those being treated. Some patients were, unsurprisingly, allergic to the treatment and either suffered reactions to leeches, larger loss of blood than intended, or even died during treatment.

Leeches and bloodletting were studied with much attention: physicians wrote books on the physiology and medical benefits of leech usage, and a very detailed description of leeches was added in the 1880 edition of Johnson's Universal Cyclopaedia.

The curiosity for leeches found its way into much earlier publications as well. For example, J. R. Johnson released multiple medical studies on leeches in the very beginning of the 19th century. His A Treatise on the Medicinal Leech (1816) and Further Observations in the Medicinal Leech (1825) dwelled on the precise details of leech usage and preservation.

From Johnson's studies mentioned above, we learn that he worked with cocoons of different sizes which he received from other leech enthusiasts. He recorded that leeches are to be kept in an enclosure with a stream of fresh water coming in and turf placed conveniently so that the leeches could "retire in a shady spot". He also studied leeches' detailed anatomical structure.

Such academic interest centered around leeches in England roots within earlier academic research done by the scientists of the 18th century - for example, an apothecary by the name George Horn who published his An Entirely New Treatise on Leeches: Wherein the Nature, Properties and Use in 1798. Interestingly, even this early into the studying of leeches, he mentions the dangers of infections if leeches were to be attracted by walking bare-legged into a river (as was done in India, according to him). Instead, he promotes the English method of agitating the leech-infested waters until the animals come up to the surface to then be caught by the nets. Overall, prior to Horn's manual not many spoke in favor of leeching: William Buchan in his study from 1769 speaks on leeches as unreliable and inefficient as it's unclear how much blood is taken per use.

Horn describes four species of leech (two of which are found in England) and dwells on their peculiar anatomy:

no eyes but a teeth-filled mouth

lips to catch blood from escaping

lack of a proper stomach

presence of the so-called "bags" across their body that "get saturated when leeches receive nourishment"

Based on the gathered information, one can claim leeches were awakening more and more scientific curiosity among the English apothecaries and physicians even at the end of the 18th century.

The medical treatment of patients with the use of leeches is described by Horn as well, though he tends to recommend additional treatment - usually mixtures of milk and syrup with herbs - to be given to the patient alongside bloodletting. This as well as other studies of the late 18th century certainly became the basis of medicinal usage of leeches in the upcoming 19th century and far into the 1910s.

It is impossible to speak of leech therapy of the early 19th century in England and beyond without mentioning the influence of François-Joseph-Victor Broussais, a surgeon of immense medical fascination with leeches who employed them vastly in his treatment of Napoleon's soldiers. Broussais used around fifty leeches a time per patient and was thus called "the vampire of medicine" for his fascination with bloodletting. He claimed, among other things, that all "fevers" had the precisely same origin: inflammation. Letting out "bad blood" was thus a plausible solution to the issue.

Women wore embroidery in colors inspired by leeches' dim, soft shades. A whole sort of fashion - à la Broussais - was born out of this unusual fascination. The notable traits of this fashion, according to Michel Valentin who wrote a large biography of Broussais, were purple garnitures - embroidery, trimming - and top coats that resembled leeches' colors.

This conclusion was, of course, the result of the "humoral theory", which was widely supported in Europe. Rooting from Greece, it centered around the idea that the human body held inside four types of liquids: two kinds of bile, phlegm, and blood. Each humor was associated with two qualities, either hot or cold, and either wet or dry. Having one of the liquids "in excess" was associated with certain conditions (for blood, it was any that caused redness, for example), hence bloodletting was a naturally sought out practice.

The leeches were placed “inside the nostrils, on the inside of the lower lip, on the chest, and on the side, sometimes by four at a time.” Leeches could access otherwise inaccessible parts of one's body (such as perineum) and were often used for treatment conditions that were believed to be connected to genitalia - for example, "nymphomaniac" states. To apply a leech, one would hold a small leech-containing vessel filled with water to the desired spot, wait until it bites, and then gently remove the container; tubes could be used as well.

A whole industry related to leeches was established in the 19th century: propagating leeches rose to the state level of importance and leech keeping became a popular activity. Leeches were, in fact, nearly hunted to extinction in some European countries in the 19th century, including England. Containing leeches started to become complicated: leeches only needed meals once every six months (and thus were not suitable for frequent use) and required specific conditions of containment. Thus, the mechanical leech quickly became a popular invention. The first prototype of 1817, called bdellomètre, is credited to French doctor Jean-Baptiste Sarlandière.

Transactions of the Pharmaceutical Meetings (1855) notes some statistical numbers regarding the "leech hunt" of the 19th century: in imports alone England received 8 million leeches annually, besides the large numbers collected within the country. The practice of using mechanical leeches (two types for different purposes) is mentioned as "ingenious" and discussed as a great opportunity to keep the natural leech healthy. The book tracks down purchases of various vessels for fresh water used as leech enclosures.

Actual preservation and propagation of leeches are described in various books of the time, though the peak of such publications in England comes around in the 1850s. In 1855, Specification of Nathaniel Johnston: Breeding, Rearing and Carrying Leeches is published. Johnston, whilst in Paris, invented an apparatus for keeping and breeding medicinal leeches: a complicated water vessel to keep leeches at the perfect temperature and humidity for the breeder - the inventor titled these containers hirudinieres. A similar invention was marked by another author in Specification of George Lifford Smartt: Vessels for Preserving Leeches and Fish Alive.

There was a lot of thought and effort put into keeping leeches healthy and vital - either for medicinal purposes or out of personal fascination.

#༺☆༻ 𝕮𝔞𝔫𝔦𝔰 𝕸𝔞𝔧𝔬𝔯 ༺☆༻#historyblr#english history#french history#victorian history#medical history#victorian era#victorian#18th century#19th century

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

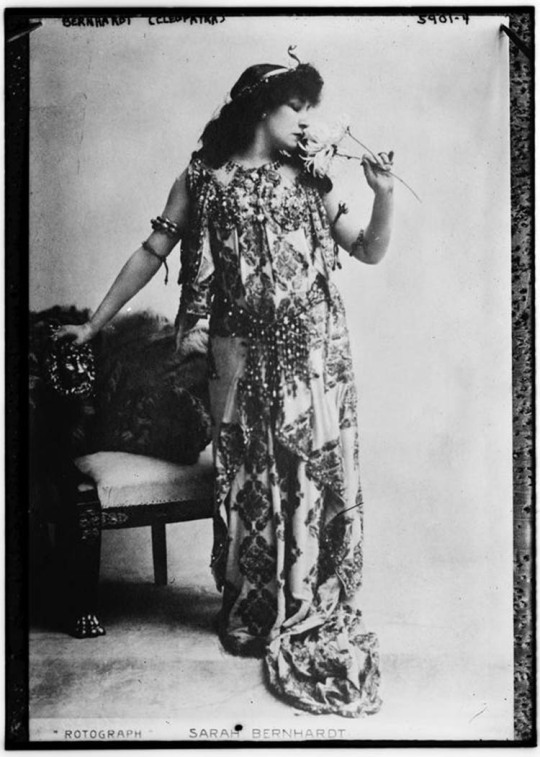

Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923) as Cleopatra, about 1891.

Egyptomania is a unique phenomenon in Western art, it sprung from the fascination for Pharaoh's Egypt culture and history. During the French campaign in Egypt (1798-1801) the art of the pharaohs begins to fascinate artists and collectors.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

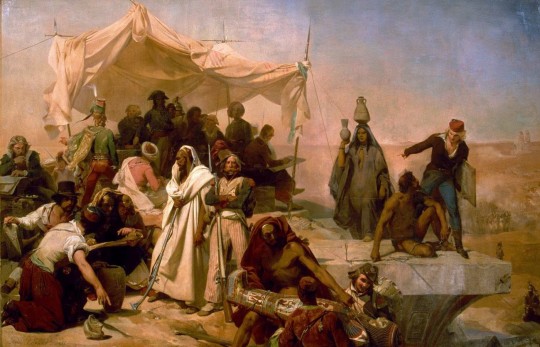

The 1798 Expedition to Egypt under the Command of Bonaparte, Léon Cogniet, 1835

#art#art history#Leon Cogniet#historical painting#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleonic Wars#Napoleonic era#Orientalism#Orientalist art#Academicism#Academic art#French art#19th century art#oil on canvas#Louvre#Louvre Museum#Musee du Louvre

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

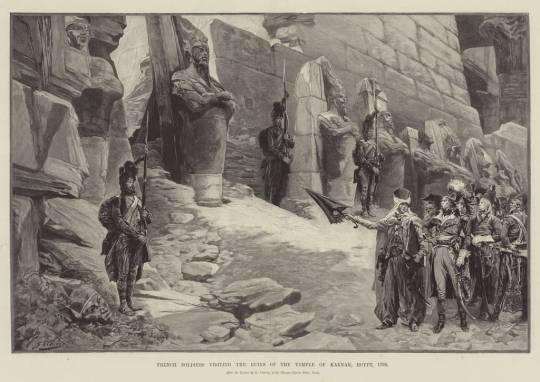

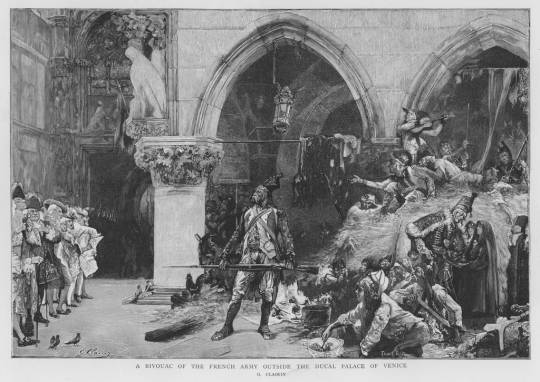

[Top] French Soldiers visiting the Ruins of the Temple of Karnak, Egypt, 1798.

A bivouac of the French army outside the ducal palace of Venice.

by Georges Clairin, 1890s

meisterdruck

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Architecture and Monuments: Great Sphinx of Giza - Egypt

The Great Sphinx of Giza is a limestonestatue of a reclining sphinx, a mythical creature with the head of a human and the body of a lion. Facing directly from west to east, it stands on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile in Giza, Egypt.

The Sphinx is the oldest known monumental sculpture in Egypt and one of the most recognizable statues in the world. The archaeological evidence suggests that it was created by ancient Egyptians of the Old Kingdom during the reign of Khafre (c. 2558–2532 BC).

A special feature of the Sphinx is its actual lack of a nose. The circumstances surrounding it about being broken off are uncertain, but close inspection suggests a deliberate act using rods or chisels. Contrary to a popular myth, it was not broken off by cannonfire from Napoleon's troops during his 1798 Egyptian campaign. Its absence is in fact depicted in artwork predating Napoleon and referred to in descriptions by the 15th-century historian al-Maqrīzī.

It is unknown how the name of the Sphinx came to be, due to propably multiples origins, for example of its creator of the Old Kingdom, as the Sphinx temple, enclosure, and possibly the Sphinx itself was not completed at the time, and thus cultural material was limited. In the New Kingdom, the Sphinx was revered as the solar deity Hor-em-akhet (English: "Horus of the Horizon"; Hellenized: Harmachis)

The commonly used name "Sphinx" was given to it in classical antiquity, about 2,000 years after the commonly accepted date of its construction by reference to a Greek mythological beast with the head of a woman, a falcon, a cat, or a sheep and the body of a lion with the wings of an eagle (although, like most Egyptian sphinxes, the Great Sphinx has a man's head and no wings). The English word sphinx comes from the ancient Greek "Σφίγξ" (transliterated: sphinx) apparently from the verb σφίγγω (transliterated: sphingo / English: to squeeze), after the Greek sphinx who strangled anyone who failed to answer her riddle.

Over the centuries, writers and scholars have recorded their impressions and reactions upon seeing the Sphinx. The vast majority were concerned with a general description, often including a mixture of science, romance and mystique.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, European observers described the Sphinx having the face, neck and breast of a woman. Examples included Johannes Helferich (1579), George Sandys (1615), Johann Michael Vansleb (1677), and some others following it. Most early Western images were book illustrations in print form, elaborated by a professional engraver from either previous images available or some original drawing or sketch supplied by an author, and usually now lost. Seven years after visiting Giza, André Thévet (Cosmographie de Levant, 1556) described the Sphinx as "the head of a colossus, caused to be made by Isis, daughter of Inachus, then so beloved of Jupiter". He, or his artist and engraver, pictured it as a curly-haired monster with a grassy dog collar. Athanasius Kircher, however, depicted the Sphinx as a Roman statue

#super wings#super wings cultural#ancient monument#historical architecture#cultural monument#cultural history

11 notes

·

View notes