#Egyptian campaign

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

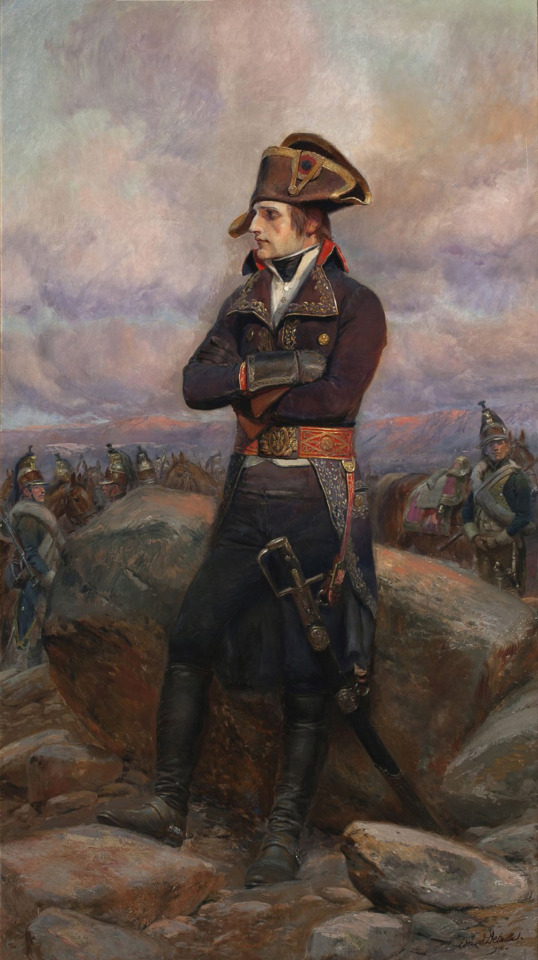

Napoleon in Egypt by Georges Scott

#napoléon#napoleon#bonaparte#egypt#art#georges scott#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#history#france#french#egyptian campaign#europe#european#egyptian#napoleonic#french revolutionary wars#french republic

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

For my time travel fic: what if the French army adjusted their clothes to the climate in egypt

So I was working on my time travel fic and while i was researching about the Egyptian campaign something just took my attention. that is the uniforms of the soldiers now we all know that those uniforms that they wore werent obviously meant for hot climates like these, I even read on the Napoleon.org that in the army alot soldiers suffered from overheating or heatstrokes.

So I decided that Leonard (my oc) in the story will make a suggestion about this issue now I dont know the protocals of uniforms getting adjusted for climate and how serious napoleon and the others would take it but im not really trying to go for a very realistic take with my story and this is more for a fun "what if" Scenario

Here are also murat and kléber in these uniforms now

The basics of these uniforms:

the basics that i use for these uniforms is that they have scarfs to protect their necks from the sun and to also offer more breathing room instead of the tight fabric they wrap around their necks

To protect the eyes i decided to add a cap that you can put over the scarf so that its secure. it is not connected to the bicorne

Also the pants are more wider like most people who live in hot climates usually have these big wide pants that leaves alot of room for the legs to breath and use lighter fabric

The most complaints that were received from soldiers is that they were constantly getting sand in their shoes so added a sort of longer legging or leg wraper that secures the boots so that no sand can come in

So this is kind of what I have at this point i know that this is alot attention to one of the issues this campaign had but im just having fun and imagining scenarios for my time travel fic ( that i really need to give name to lmao)

Also have a kléber doodle cus why not

#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#napoleon bonaparte#jean baptiste kleber#joachim murat#egyptian campaign#time travel fic

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gaspard Monge and Jean-Baptiste Kléber in a fragment of Panorama de l'Histoire du siècle 1788-1889 (1889) by Alfred Stevens and Henri Gervex, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville de Paris.

The original title of this piece is Le Panorama du siècle : Kléber et Monge, entourés de personnalités de la Révolution française.

The man behind them is the Admiral François Paul de Brueys d’Aigalliers.

Sources: 1, 2.

References for the characters’ names from Stevens, Gervex, Reinach L'Histoire du Siècle, p. 40-41.

#kleber#french revolution#gaspard monge#egyptian campaign#frev#napoleonic era#frev art#napoleonic art#art#jean baptiste kleber#jean-baptiste kléber#queue#18th century#19th century

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was supposed to be more but seems like I can't finish anything for some reason currently. Maybe later. Until then feel free to interpret anything you want into what is going on here.

#napoleon bonaparte#jean andoche junot#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#not napoleon‘s marshals 😔#wanted to draw a bit more cartoony#egyptian campaign#artists on tumblr#my art

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon proves to skeptical troops that there are really pyramids in Egypt.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugène about Duroc

I understand there's some interest in Duroc, about whom there is just not enough information out there, period. This is rather random but maybe it will be helpful to somebody. From Eugène's correspondence I already had the impression that he and Duroc had been very close. Eugène mentions Duroc in his memoirs for the first time during the Egyptian campaign.

Around this time, I began to form a friendship with Duroc which continued to grow right up to the time of his death. At that time he did me a service that I shall never forget. The day after we entered Gaza, and after a most exhausting journey, General Bonaparte gave me the order to leave at midnight to bring movement orders to General Kléber, who was a few leagues ahead, in the direction of Ramleh. In such a case, the brigadier of the post, whose duty kept him on his feet at all hours of the night, had orders to wake the aide-de-camp who was due to leave. He did so, but no sooner had he left than I fell back asleep. Those who have served at an early age know how powerful sleep can be at the age I was at the time [...].

That age being 17.

[...], it is irresistible and capable of making us forget both danger and duty. Duroc, who was older and more experienced than I, realising that I had not left, shook me forcefully and urged me to get up. I resisted, telling him that I couldn't take it any more and that it was impossible for me to move. But he only redoubled his entreaties, adding in the end, with a sort of anger, that this was not the way to serve and that I was going to dishonour myself. This word made me blush and shook me out of my grogginess. I left without an escort, as no one dared to take one unless expressly ordered to do so by the general-in-chief, and, after meandering for nearly five or six hours, I arrived at the very moment set for General Kléber to set his division in motion.

Kléber: Yeah, sorry for being late, Bonaparte. But your aide was asleep in the saddle, and it took his horse a while to find the way...

I love Eugène in this a) because he admits his own weakness and b) because he reminds me a lot of my brother who, at the same age, managed to sleep through an alarm that woke me up in my room on another floor...

#napoleon's family#eugene de beauharnais#napoleon's generals#geraud christophe michel duroc#egyptian campaign

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guys, Extra History series about Napoleon in Egypt has dropped!

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

He was so beautiful

#this actor must play napoleon more often#napoleon bonaparte#I WANT A WHOLE MOVIE OF THIS#With english subtitles too#or spanish#BUT PLEASE#HE'S SO FUCKING FINE I CAN'T TAKE IT ANYMORE#RAHHHHHHHHHHHHH#Egyptian campaign#bonparte: la campagne d'egypte

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

As Eugène's testimony (for what it's worth) is mentioned several times in the post I thought I could add a quick translation of the passage regarding Jaffa.

For context: Eugène's memoirs were only started in 1823, a year before his death, after he had had his first stroke, on the insistance of Planat de la Faye who had become Eugène's secretary, and were quickly abandoned again because Eugène felt he could not focus long enough any more (or possibly, because he felt he was dying and did not want to spend his last months confined in an office). So the fragment of Eugène's memoirs ends right after Napoleon's coronation. It was only published, as far as I know, by DuCasse during the Second Empire and forms a tiny first part of "Mémoires et Correspondence politique et militaire du Prince Eugène" (10 volumes). So the text often is very short, lacks details and may be more of a draft rather than a text ready for publication.

However, the army set off for Jaffa, and we arrived there on 4 March. After three days of preparations, the town having refused to surrender, we began to make a breach, and as soon as the breach was practicable, the general-in-chief ordered the assault. At the same time I was ordered to enter the town on the seaward side with a cavalry picket, while the infantry passed through the breach. I had great difficulty in getting there because of the obstacles of the terrain, which everywhere presented steep slopes, holes and dangerous steps for the horses. The streets of the town were so narrow that barely two riders could pass side by side. There was a fierce battle for part of the day. Our soldiers, irritated by the resistance, laid their hands on everything they came across: the massacre and pillaging lasted all night. The next day I was sent to try to restore order and put a stop to the excesses that soldiers always commit in such cases. It was the first time I ever saw a town taken by storm, and the sight struck me with horror. Almost all the inhabitants of Jaffa had had their throats cut, regardless of age or sex, the ground was strewn with their corpses, and blood was running down the streets.

I am coming to a story that has been told so often and in so many different ways that it is impossible not to mention it. I will recount what I saw and heard at the time. Our troops, fed up with the carnage, took some prisoners at Jaffa on the second day, and their numbers increased by about eight hundred men, who had thrown themselves into a small fort and surrendered the same day. The general-in-chief, after consulting the generals under his command, decided that all these prisoners should be shot.

Some colonels, including Boyer, refused to carry out such an order, which was finally carried out, no doubt very reluctantly, by Colonel d'Armagnac, commanding the 52nd regiment. This action was strongly criticised and indeed appears revolting at first sight. However, it was justified in several ways, and above all by an imperious necessity. First of all, there was no food for these prisoners; the resources that the town of Jaffa could offer had just been destroyed by looting, so that the army was on the verge of running out of food. In addition, a large number of these same prisoners came from the garrison of El-Arisch; they had been released on parole and, according to the laws of war, merited death. The lack of faith of these troops having been recognised by experience, to send back the other prisoners in the same way was to risk finding them armed against us the next day. These were the reasons given to the army to justify such a cruel measure. The honour and generosity of a Frenchman, stronger in him than prudence, resented such an action; but it is also fair to say that the general-in-chief only decided on it with great difficulty, and that our soldiers only carried it out with murmurs.

Three days after the capture of Jaffa, the army continued its march towards Saint-Jean d'Acre [...].

As to the extent Eugène consciously is repeating lies in his memoirs, I don't want to judge. While he was indeed "on the ground", he also was only a 17-year-old aide-de-camp of the general in chief, whose grasp on the situation may have been limited and who genuinely believed what he had been told by his stepfather at the time, and clung to that believe later. Plus, he in truth does not beat around the bush: the main reason he gives for the massacre is that the prisoners were in the way, plain and simple, as they would have taken valuable resources from the French army. That's what he calls the "imperious necessity". Everything else comes secondary.

Also to consider, as with all memoirs: These memoirs were considered for publication eventually. Critisizing Napoleon in them surely was not their main intention...

Thank you very much for the archived link to Cyril Drouet's post! That's an excellent compilation, and it mostly shows that the sources even by the French differ a lot (so there must be more people lying in there).

The Massacre of Jaffa: Bonaparte's Lies

This tragic episode of the Jaffa massacre will explore the events surrounding the massacre carried out by Napoleon Bonaparte, the lies he used to justify it, and how these falsehoods were later repeated by others, including Eugène de Beauharnais, to defend the executions. Although Eugène was not involved in the massacre, he consciously repeated his stepfather's lies. In this analysis, we aim to avoid both the golden legend and the black legend.

On March 7, 1799, Jaffa fell to the French army during their campaign in Syria. The city became the site of a particularly brutal massacre of prisoners, some of whom, according to testimonies, were civilians. The main figure responsible for this carnage was Napoleon Bonaparte.

The account of Jaffa’s capture has been shared in various versions, from immediate eyewitness accounts to official narratives published later. This diversity of perspectives raises important questions about how the events were perceived and reported, both by direct witnesses and by French authorities.

The siege of Jaffa was part of Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign. After capturing the city, the French encountered a determined garrison composed of soldiers from the army of Djezzar, the Pasha of Acre. The attack on Jaffa was intense and violent, leading to a massacre that targeted both soldiers and civilians.

Bonaparte justified this massacre with two lies. The first was that the prisoners had committed perjury (a complicated lie), and the second was that there was a lack of provisions (a simpler lie). Years later, Bonaparte even reduced the number of prisoners and continued to lie about the massacre, even on Saint Helena. This caused discomfort and raised further questions about the truth.

Men loyal to Bonaparte, such as Eugène de Beauharnais, also repeated these lies (although Eugène was not directly responsible for the massacre at Jaffa, he openly echoed his stepfather’s fabrications and must have known the truth, as he was present on the ground)to justify this massacre . You will see that these justifications do not hold up in the link I will share. Initially, I planned to write an article on the subject, but I found a French website containing the work of Cyril Drouet, who does an excellent job of debunking both the golden and black legends surrounding Bonaparte. His work includes testimonies and exposes the violations of wartime laws.

The golden legend justifies the massacre by relying on Bonaparte's lies, while the black legend portrays him as a man who enjoys massacring people for pleasure or executes people based on whim. Both of these views are false. I believe Bonaparte when he states that he did not take pleasure in such actions and was haunted by certain decisions (this perspective comes from someone who generally dislikes Bonaparte).

However, the Jaffa episode is revealing. Bonaparte sometimes believed that instilling fear in his enemies was the only way to deal with them, even if it meant ignoring basic rules. What happened? His opponents, who were seasoned soldiers, only intensified their resistance. These were not impressionable civilians. Bonaparte's victories, or defeats, came at such a high cost that they were often humiliating, resulting in what could be described as a Pyrrhic victory. I have the impression that Bonaparte was occasionally unable to think long-term and focused only on short-term gains.

Indeed, it has been observed that, contrary to popular belief, the victory against Delgrès in Guadeloupe was difficult. Richepanse himself acknowledged this, and for good reason: the soldiers facing him were experienced and well-trained in the art of war. Initially, Richepanse thought that the soldiers who fought against the restoration of slavery, having already faced the British, would bend under intimidation. This was an absolute mistake. Furthermore, the expected economic results never materialized. Similarly, in Saint-Domingue, the conflict ended with a victory and the proclamation of Haiti.

What is the connection to Jaffa? In a similar vein, the massacre not only strengthened the resolve of his enemies but also prompted the Ottomans to justify the execution of some French soldiers by sabre after this massacre ordered by Bonaparte. This is one of the many reasons why rules regarding the treatment of prisoners were established during wartime and should never be violated. (Interestingly, Ottoman forces, according to some testimonies, were more merciful than the French troops.) In short, Bonaparte’s attempt to intimidate the Ottomans by carrying out this horrific massacre under false pretenses failed, having the opposite effect.

I had initially planned to create a separate post, but I found an archived history forum, now closed, where a user named Cyril Drouet gathered all the testimonies and dismantled Bonaparte's and his allies' lies. It's an insightful read and provides a more analytical summary of the issue than I could. You can access it here: https://web.archive.org/web/20170629145019/http://passion-histoire.net/viewtopic.php?f=55&t=37621&sid=7f51b3c72ebbbe9534d2d163d70204fe (it’s in French, but can be translated into English).

For more information on Guadeloupe or Haiti, here are some posts I've written, which touch on the subject alongside Jaffa: More information on slave revolts in the Caribbean Louis Delgrès: Freedom Fighter Mini portraits of three revolutionary women A revolutionary and white battalion leader

The most comprehensive piece so far is about Haiti: The shocking acts by the French army

#napoleonic era#napoleon's family#eugene de beauharnais#eugene's fragmented memoirs#napoleonic wars#jaffa 1799#egyptian campaign

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonaparte in Egypt, 1798 by Édouard Detaille

#napoléon#napoleon#egypt#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#art#portrait#édouard detaille#egyptian campaign#france#french#french revolutionary wars#napoleonic#history#bonaparte#europe#european#egyptian#campaign

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

A young Napoleon getting acquainted with the Egyptian widlife.

#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#egyptian campaign#originally i wanted to draw a desert mouse from dune but it kept looking like a fat rat which wasnt really the vibe i was going for#then i learned the desert fox became sort of a symbol of orientalism in the 19th century so i guess this is more fitting anyway#my art

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love this guy. Glad you noticed and posted him.

This Napoleon was pretty cute

#egyptian campaign#strange video about the Egyptian campaign#handsome young bonaparte#I love this guy#mygifs

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting a Slave Market in Cairo” (1911) by Maurice Henri Orange who also painted Napoleon looking at a mummy.

pinterest

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugène about Kléber

This is for @gabrielferaud, translated once again from Eugène's memoirs. The passage continues right where we left off in this post. Timeline: Egyptian campaign, during the campaign into Syria 1799, siege of Acre. (I've broken the text up in two paragraphs for besser readability.)

General Kléber, as impatient as the rest of the army with the length and futility of the siege of Saint-Jean d'Acre, said one day that he did not understand why we insisted on staying in front of this shanty and that, if he were in the place of the general-in-chief, he would have left the camp a long time ago. Somebody suggested that it was a question of the glory of General Bonaparte: "Bah! bah!" he said in his German accent, "it's a nice suit with a spot of dust on it: with a flick of the wrist you can make it go away". This comment, although in essence an honourable one for the General-in-Chief, was distorted and aggravated, as were others like it, in the reports made to him, with the result that he was effectively irritated with General Kléber. But it is impossible to imagine that he was jealous of this general. His rank and military reputation placed him so far above him that this reason alone was enough to prevent him from feeling any jealousy. It is more natural to think that Kléber felt this way about a general younger than himself and whose superiority offended him. It is also fair to say that General Kléber did not lack good reasons for criticising the siege of Saint-Jean d'Acre, which was undertaken rather sloppily and without having assembled the means necessary to push it forward vigorously. Neither the engineers nor the artillery were up to the task, with the result that the bravery and talents of the officers of these two arms were spent in vain.

Now look who’s critisizing his stepdad 😋. But i feel like Eugène tries to understand both sides here. He defends Napoleon against the accusations that had been made against him, yet admits that Kléber’s criticisms were warranted.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ridley Scott: I made a film about two rival officers constantly duelling throughout and in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, and now I've actually done a film about Napoleon!

Me: Great! Could you also do a film about Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, a vital innovator in European battlefield surgery and triage, often considered the first military surgeon; who pioneered the ambulance volantes ("Flying ambulances") to quickly transport wounded men from the battlefield, effectively creating a forerunner of the modern MASH units; co-led the team that performed one of the first accurately recorded pre-anaesthetic mastectomies in Western medicine; was spotted helping wounded men while under heavy fire during the Battle of Waterloo by the Duke of Wellington who purposefully ordered for his soldiers not to fire in Larrey's direction; and when captured by the Prussians after the battle was about to be executed on the spot when he was recognised by one of the German surgeons, who pled for his life because he had saved the life of Field Marshall Blücher's son some years earlier?

Ridley Scott:

Ridley Scott: Um.

Me: Yeah. Didn't think so.

#Yeah; Baron Larrey was one of my dad's heroes#When we went to Père Lachaise Cemetery we went partly to honour his grave#ridley scott#Baron Dominique Jean Larrey#baron larrey#Dominique Jean Larrey#napoleon 2023#the duellists#the duellists 1977#check out the duellists; it's a REALLY good film!#Larrey did a lot of other stuff that I didn't mention; otherwise I'd just be vomiting the wikipedia page#He was a close favourite of Napoleon and went on the Egyptian campaign#he started a school in Cairo where he researched opthalmy (inflammation of the eye)#He made sure that all soldiers (not just French and their allies) were treated#The mastectomy was to treat suspected breast cancer#(unknown to this day if there actually was cancer but perhaps better safe than sorry)#and the patient was Frances Burney#who frankly deserves a film or tv series of her own#If you're up for it she wrote her own description of what the operation was like; which is there to read on her wikipedia page#Whether or not her breast WAS cancerous she lived another thirty years#Ironically her husband DID die of cancer#anyway#*jazz hands*

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonaparte and the Sphinx by Amédée Vignola

#napoléon#napoleon#bonaparte#egypt#sphinx#art#amédée vignola#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#egyptian campaign#france#french#history#europe#european#pyramids#egyptian#pyramid#campaign#french revolutionary wars#napoleonic#french republic

172 notes

·

View notes