#edisonade

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

TWENTY YEARS TO MIDNIGHT

The Venture Brothers starts out as a show that makes fun of the past, but lasted long enough to be one that truly understands it.

So I rewatched The Venture Brothers in one big splurge over the course of two weeks, from Turtle Bay to Baboon Heart.

One of the most charming things about the show is a product of its lengthy creation process and the fact that it was written almost entirely by just two people. The story nearly has a tight continuity, so if you take it at its word then all the events of the story take place over a period of two and a half years, while the actual show was made over a period of twenty years.

The outcome of this curious time dilation is that we follow the Venture Brothers, Hank and Dean, through those difficult years between 16 and 18, but we also follow the writers, Jackson Publick and Doc Hammer, through the difficult years between their twenties and their forties. The show begins irreverent, contrarian and cruel and changes, cell by cell, into something wiser and more profound.

The treatment of Rusty Venture, former boy adventurer and long-suffering heir to the poisonous Venture legacy, is a fascinating thread to follow. In the very first episode he steals his son's kidneys like a ghoul, and his various addictions and neuroses are firmly treated as quirky objects of pity. I don't know much about the personal lives of the writers, but I imagine a certain amount of tragedy would have found them over the course of twenty years. A certain empathy for Rusty's position kicks in around the second season and develops strongly throughout the years. By the time the writers have reached the age that Rusty is when he is introduced, there are delicate attempts to reach out to the poor man, to understand and maybe counteract some of his own personal tragedy, though careful not to smother the comedy that such a character brings to the table.

But the thread I enjoyed following the most was that trailing behind Action Johnny. If you have ever heard of The Venture Brothers, you already know that the show began as a parody and deconstruction of the 1960s Hanna Barbara cartoon Jonny Quest, which was itself an attempted relaunch of the Edisonade craze of the 1910s, riding on the coattails of the far more successful and popular Tintin and Uncle Scrooge comics.

Jonny Quest was the son of a world famous scientist and adventurer, Doctor Quest, who led an extraordinary jet setting life where he accompanied his father to exotic places to experience exciting, often racist, science-themed thrills instead of going to school. He was watched over by his lantern-jawed bodyguard, Race Bannon, and joined with his adopted brother, Hadji.

The Venture Brothers stole this set-up entirely, and Rusty's backstory is a carbon copy of Jonny's. We are first told that this is something more than a swipe early on in the first season of The Venture Brothers when Race Bannon appears, as himself, as a secret agent belonging to the same organisation as the Venture family bodyguard, Brock Samson. It's a clever shorthand for saying that boy adventurers are not singular in this world, they are a type, one which occupies a distinct social strata along with their bodyguards, enemies and other supporting cast members.

The way that we are told this fact, in the seventh episode of the first season, is peak 2004 adult swim: beloved cartoon character Rave Bannon drops out of the sky, lands in front of one of our characters, dies, then shits himself. This was vaguely subversive at the time, but twenty years of Robot Chicken and the like have rendered it a tired, hoary gag. Venture Brothers itself has proved that this moment is at least a wasted opportunity. There was undoubtedly more comedy and interest to be mined from having Race Bannon around as an older counterpart to Brock Samson. But there was fun to be had with squandering opportunities and biting the hand that feeds for writers in their twenties in 2004.

When Jonny Quest himself appears in 2006's season two episode, Twenty Years to Midnight, things aren't much different. Jonny is found haunting the bathyscaphe from the cartoon, injecting heroin, waving an antique pistol and ranting about his father. He has a teardrop tattoo and missing teeth. He is discovered by Rusty's brother, the overachieving but naïve Jonas Junior. It's a much better gag in execution than the Race Bannon one, despite being essentially the same beat, but there is some pathos thanks to Brendan Small's delivery. Jonny is left alive, unlike Race, but the capper to this scene is somehow more humilating and tragic than when Race's corpse shat himself: Jonny is brought on side by Jonas Junior who, pressed for time and not as accustomed to being threatened and menaced as Rusty is, is unable to apply superscience to this situation and simply offers Jonny a supply of heroin.

The entertainment industry's relationship to its back catalogue of intellectual property has changed a lot in the last two decades. Characters like Jonny and Race were embarrassing curios in Ted Turner's garage in 2006. Why not dust them off and kill them in a cartoon to make college kids giggle? Why not give them a crippling drug habit and have them collapse to their knees, bellowing, "I'm in real pain!" But within ten years the media behemoths realised they could spin their old straw into gold, and instead of selling sheink rays at a yard sale, so to speak, they were putting the Flintstones in ads for Halifax bank.

So the Venture Brothers show renamed their tragic, adult Jonny Quest to 'Action Johnny' and in doing so was forced to consider him as a character rather than a skit. And the colossal strength at the heart of the Venture Brothers is in taking ridiculous things like boy adventurers seriously. Jonny Quest was allowed to become a valuable (?) piece of IP, forever a child, forever innocent and marketable, while Action Johnny could live his life unfettered by the parent company's fears.

Action Johnny appears two years later in Season 3, sober but shaky, doing a favour to Rusty by running a seminar for his ill-fated summer camp. He undercuts the spirit of the event by warning the children of the long term effects of adventures on the psyche and unravels into rants about his father. It's a solid bit by itself, especially when contrasted with a neighbouring table from the Pirate Captain (who, despite being an important recurring character, the show refuses to give a name) about the joys of being part of the 'rubber mask set.' Though the world of the Venture Brothers is nominally organised through a bureaucracy of licenced 'protagonists' and 'antagonists,' the biggest tension on screen is between the characters who chose the life, like the Pirate Captain, and those who had the life forced upon them, like Action Johnny. It just so happens that the former tend to end up as tortured, resentful good guys and the latter wind up as joyful, carefree villains.

Bringing that point home in the same episode is the appearance of Doctor Z as the summer camp's headliner. Doctor Z is the final borrowed character Jonny Quest, and one who the writers clearly take the brightest shine to, probably because he has the funniest voice to imitate. Doctor Z also represents the goals of show's resplendent second half - having deconstructed the boy adventurer genre in the early seasons, the Venture Bros very carefully puts the pieces back together into something wholly new.

And so Doctor Zin, the generic yellow peril villain of Jonny Quest, becomes Doctor Z, the retired and contented former archfiend of the Venture Bros. Doctor Z is treated by the other characters as something like a national treasure, a beloved old star who made the game his own. The joke of Doctor Z is that he seems genuinely bemused that his lifetime of villainy seems to have had a lasting negative effect on people. When he appears at Rusty's summer camp, all theatre and terror, he is delighted to meet his old foe Action Johnny, while Johnny is thrown into a whirlwind of trauma at the sight of Z, one that will drag him down into further troubles.

Doctor Z will become more of a feature than Action Johnny over the following years as the show becomes more interested in its older cast members - the ones whose personalities shaped the world, and who have sunny memories of the days that were so painful to Rusty and Johnny. He is part of a larger rehabilitation arc on the meta level, where characters with reprehensible aspects to them are held up for the audience to inspect so that they may find some empathy with them. Sargent Hatred is the poster child of this era, who is a repentant paedophile who joins the main cast as the Venture Brothers' new bodyguard. He's a whole other topic, but Doctor Z has the same function as Hatred, but on a metatextual level. His ancestor, Doctor Zin, is a hideous racial stereotype of the sort that makes modern revivals of the adventure genre so unpalatable. In its first deconstructionist half, the Venture Brothers show would simply wave Doctor Z around as shock tactic - 'look how racist Jonny Quest was, and by extension the company that made it and, logically, its audience!' and then maybe give him a violent and undignified death to wash their hands of the whole matter. But the reconstructivist Venture Brothers show embraces Doctor Z, and takes him beyond his tawdry origins to become an integral part of its story.

In 2009, Action Johnny helps Rusty to articulate this in the episode 'Self-Medication' from Season 4. Johnny and Rusty are in the same therapy group for former boy adventurers, a premise that would later be stolen wholesale by the She-Hulk show. A trail of tenuous clues leads the group to Doctor Z's house in the middle of the night. Johnny forces a confrontation with Z, accusing him of murdering their therapist to perpetuate the spiral he has been in since he saw Z take the stage back at Rusty's day camp. Doctor Z immediately groks the situation and invites the former boy adventurers into his home for tea with his beloved wife, who proudly proclaims herself to be his beard. Doctor Z is proud of what he has done in life, and so has the ability to put the past behind him. Sat between Z and Johhny, who is unable to move on, Rusty realises that he has more in common with the antagonist in the room than the protagonist. Rusty has many such insights throughout the length of the show and they lead him to an interesting end point where he seizes the nettle and becomes a parental figure to the whole weird superscience community.

The final encounter between Action Johnny and Doctor Z takes place nine years (!) later in our timeline - 2018's 'The Terminus Mandate.' Doctor Z is retiring from active villany and, according to the ceremony-obsessed fraternity of organised supervillans, that means he must menace his archenemy one last time. Action Johnny's father is long gone, so Johnny inherits that dubious honour.

It's the first time that we see Doctor Z not being fully committed to the bit. Johnny is resident at a posh rehab clinic and Doctor Z is conflicted between genuinely wanting to see Johnny again but unsure of how to interact with him in a way that doesn't cause actual, lasting harm. Doctor Z even brings a prop from a Jonny Quest cartoon as a gift, in a sequence lovingly reanimated to translate Jonny Quest's vocabulary into the Venture Brothers' language. The sequence chosen is virulently racist, almost too racist to be believed: a mask of the god Anubis lands on top of Johnny's dog, and Doctor Z's Egyptian henchmen suddenly believe that the mask is a vengeful god come to punish them and so abandon the young Doctor, giving the advantage to Johnny's team. In the lobby of the rehab centre, in the late to evening, Doctor Z struggles to articulate why the Anubis mask means so much to him and Johnny cringes at the memory while enjoying the act of reminiscing. He offers to go and run and hide, so that Z can find him, and they both discover they are delighted by the idea.

It's a touching, uncomfortable and deeply weird scene that, to me, is the pinnacle of The Venture Brothers as a creative endeavour. Behind it is a group of people who have been mulling over the implications of Jonny Quest as a short-lived but impactful cultural phenomenon for most of their adult lives. They have been mining the absurdity, the legacy, the implications, the pathos and the bathos of those 26 half-hours of cartoon and found incredible treasures. It starts with finding a silly old thing in the attic that you want to ridicule and it ends, twenty years later, with you acknowledging the attachment one has formed to that silly old thing, and how it has informed your life, for better or worse, in ways you can't deny.

#venture bros#rusty venture#jonny quest#hank venture#dean venture#action johnny#hanna barbera#jackson publick#doc hammer#adult swim

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

The impetus of older stories live on in their successors. Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers live on in Star Wars and Star Trek. Iron Man inherited the conceptual space of the Edisonade. And the empire-building, white-mans-burden masturbatory power fantasies of Edgar Rice Burroughs find their successor in spacebattles self insert fiction

118 notes

·

View notes

Photo

G. Y. KAUFMAN - MARTIAN GIANTS CONSTRUCTING THE SPHINX, ILLUSTRATION FOR EDISON’S CONQUEST OF MARS BY GARRETT P. SERVISS

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science Fiction Subgenres from A to N

So, to start this blog off with something fun, I thought I’d do a series of big ol’ masterlists covering sci-fi and fantasy subgenres! There is a heckin’ large amount of them, so I’ve split it up into four sections with about five or six posts- this one right here is for, you guessed it, science fiction, from A to N. *cue distant cheering*

First up, a little recap:

Science Fiction: This can be considered a difficult genre to define, simply because it can encompass nearly anything- but the best definition I’ve heard is that it’s “the literature of change”, particularly in areas of scientific advancement and technological growth. According to Wikipedia, this is a genre of speculative fiction “typically dealing with imaginative concepts such as futuristic science and technology, space travel, time travel, faster than light travel, parallel universes, and extraterrestrial life.” (x) Science fiction generally encompasses imaginary worlds and universes bound to laws of physics (although not necessarily the laws we know of or follow) that are advanced in some way by science and technology, and experiencing some form of change because of that. To put it very simply, science fiction can be viewed as fiction based upon science. Science fiction tends to evoke thoughts of aliens, spaceships, robots, AI, new planets, futuristic cities, flying cars, high-tech things made of shiny metals, lightsabers and phasers, environmental sustainability, and far-future social themes. Examples include Dune (Dune series) by Frank Herbert, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, Lagoon by Nnedi Okorafor, The Stars Are Legion by Kameron Hurley, 1984 by George Orwell, Leviathan Wakes (The Expanse series) by James A. Corey, Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee, and Parable of the Sower (Parable series) by Octavia E. Butler.

With that refresher in mind, let’s begin! (I’d apologize for the word count, but we’re all nerdy writers here.)

Apocalyptic Sci-Fi: Ah, one of the favorites for anybody who enjoys good ol’ destruction and chaos in their books. This subgenre is characterized by a cataclysmic event occurring that wipes out the vast majority of the human population, often with extensive destruction across the globe.

Common tropes for this include alien invasions, environmental disasters (oooh, one of my favorites- things such as catastrophic climate change), plagues or viruses (bioweapons and bioengineering, including the “zombie” virus as one of the current most popular- who doesn’t love zombies), the technological singularity or failure (the “robot uprising” vs. a worldwide EMP), astronomical events such as meteors, super-flares, or radiation bursts, supernatural events (demonic war, the Four Horsemen on Earth, vampires or other monsters), etc.

Apocalyptic sci-fi goes hand in hand with post-apocalyptic sci-fi, but the former can be set apart from its counterpart in that it takes place during the exact time of the “apocalyptic” event- however, keep in mind that most books, even if they show the apocalyptic event in the beginning, tend to shift towards post-apocalyptic as the characters learn to survive in the aftermath. Finding something that is solely an apocalyptic sci-fi novel is rare, and I will admit I had some trouble with it.

This subgenre is often used to show human nature in chaotic times (how people panic, the “sheep” effect, mass hysteria, how individuals respond to their impending demise), as well as portray extreme destruction of cities and civilization, exemplify survival tactics, and use the setting as a source of action, drama, suspense, plot twists, and personal growth for characters as they act and react to their rapidly changing and dangerous world.

Examples: Life As We Knew It by Susan Beth Pfeffer (astronomical event, meteor strikes moon), The Stand by Stephen King (bioengineered virus and supernatural events), Seveneves by Neal Stephenson (astronomical event, moon is destroyed), Robopocalypse by Daniel H. Wilson (technological singularity, robot uprising), Ashfall by Mike Mullin (environmental disaster, supervolcanic eruption), The 5th Wave by Rick Yancey (alien invasion, environmental disaster, technological failure, and a deadly plague, for all your apocalyptic needs)

Note: Although not books, I also like to include the movies 2012, The Day After Tomorrow, World War Z, and Independence Day.

“Dying Earth”: If I’m being honest, this is probably the most depressing science fiction subgenre- probably even more so than the related-but-not-quite-the-same apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic subgenres- so thank goodness it’s fairly small. Given the name from the series of works (aptly titled “The Dying Earth”) by Jack Vance which portrayed our Earth, millennia from now, as an exhausted, dying world orbiting an equally exhausted, dying star, the “Dying Earth” subgenre embodies themes of bone-deep exhaustion, depletion of planetary resources, innocence and idealism and (potentially) the loss of both, and The End of Time/Earth/The Universe.

Common tropes include Earth or other planets physically dying (from the aforementioned resource depletion, going sterile, the sun burning out, being too old), stars burning out/going supernova and dying, laws of the universe failing as it dies, and species falling to extinction (from their planet/sun dying, out of apathy or exhaustion or physical/emotional/spiritual weariness, etc). The subgenre as a whole can pretty much be summed up as “melancholic”.

Although it also shows an end-of-the-world scenario, this subgenre differs from simple “apocalyptic events” and the related subgenres by virtue of not having anything so dramatic- instead, it simply shows the world as it winds down into a slow death.

But wait- perhaps it’s not entirely depressing! Some works in this subgenre also employ themes of hope and renewal, and the “Dying Earth” subgenre is often used to show optimism in the face of death, human endurance, looking forward to the unknown, and future promise. Thankfully, it’s not all about the “entropic exhaustion of the Earth” and the fading of “the current comprehensible state of the universe”- talk about a bummer.

Examples: The Dying Earth (series) by Jack Vance (the books that gave the subgenre its name), The Time Machine by H. G. Wells, City at the End of Time by Greg Bear, Dying of the Light by George R. R. Martin, certain stories in Sunfall (anthology) by C. J. Cherryh, Earthchild by Doris Piserchia (interestingly enough, I haven’t found anything in this subgenre over the past 10 years or so)

Note: Outside of books, the comic series Low by Rick Remender and the video game Dark Souls can be included in the subgenre. Movies such as Reign of Fire, I Am Legend, The World, the Flesh, and the Devil, and The Quiet Earth could be considered vaguely “Dying Earth”, although they really don’t capture the melancholic, tired aspects that the subgenre embodies, and the endings distinctly lead away from the subgenre.

“Edisonade”: This one’s kind of short, because not only is it really small and generally unheard of, it’s also pretty old- old enough to be primarily from the time of “all sci-fi writers were men” and everything was written to appeal to the male gaze. Basically, it’s a subgenre that includes stories about a character who is “a brilliant young inventor” in the ways of Thomas Edison, as they use their invention(s) to save their nation, save their love interest, defeat the villain, and presumably get rich and live prosperously as a quirky inventor forevermore.

Although it is, at its core, something that could be very interesting to write and read- who doesn’t want to write about brilliant inventors?- the fact of the matter is that all the books in this subgenre tend towards a teenage/young man being the inventor, and saving the girl, and defeating the villain (normally foreigners, evil scientists, or aliens). At the time that stories in this subgenre were written, a lot of them (not all!) reflected nationalistic, misogynistic, and generally racist views and tended to feature things like widespread colonization, exploration of parts of the world with “untamed lands and peoples”, and self-insert characters for boys to relate with on the premise of superiority and “saving the day”.

The good part? The “Edisonade” subgenre tends to be progressive in the ways of science, technology, and engineering, and it can be somewhat related to steampunk. Other than that...the subgenre itself needs a bit of a reboot, so to speak. Any takers?

Examples: The Steam Man of the Prairies by Edward S. Ellis, Tom Edison, Jr.(series) by Philip Reade, Tom Swift (series) by Victor Appleton

Hard Sci-Fi: And so we come to one of the ongoing debates amongst sci-fi communities- “hard” science fiction versus “soft” science fiction. Hard sci-fi can be defined in a number of ways, and that has caused quite some controversy over the years- but the general consensus is that hard sci-fi is generally a subgenre of science fiction that depends upon more science, as well as greater scientific accuracy and explanation in its novels.

Novels in this subgenre are generally characterized by a large amount of science to go with the fiction- the “science and technology parts of science fiction are featured front and center, the scientific concepts are founded upon legitimacy, research, and lots of explanation, and the stories are more realistic and heavy.

Here’s where some controversy comes in- sometimes a novel is “science-y” like that, but it’s primarily left in the background of the story, so it could be considered “soft” sci-fi.

Also, many “hard” sci-fi works tend to focus on STEM-like areas (engineering, math, formal sciences like physics), or assume that the natural sciences (biology, environmental science, geology, etc) make a sci-fi story inherently “soft”.

Sometimes, technology is left almost entirely in the background of a sci-fi story, with those natural sciences featuring more.

Other times, the science that the novel is based upon proves to be faulty, or something is incorrect, or some of it is just plain implausible. See the dilemmas?

Anyways, here I am simply defining “hard sci-fi” as science fiction writing that focuses more on the scientific and technological aspects of a story, with an emphasis on legitimate scientific concepts, research, theories, and fact, and that incorporates much of those ideals into the writing and story itself (as plots, background, etc).

Common tropes in this subgenre include hypothetical, explained logistics for futuristic technologies (faster-than-light travel, terraforming, spaceships, space habitats, etc), more realistic-looking tech, sometimes at the expense of being “less pretty” (spaceships that aren’t made of shiny stuff and still cause pollution, for instance, or spacesuits that look more like spacesuits rather than trendy plastic-wrap), and sometimes a lot of lengthy explanations within the story that you have to read a few times to really understand or some words you have to look up (keep a dictionary with you for some of these books, I mean, wow).

This subgenre is often meant to show how the future could be soon, to show science fiction in a less out-there, more relatable light, appeal to more literal-minded people who desire scientific fact in their fiction or plots based upon legitimacy, explain the fundamentals of a story without “hand-waving”, and to explore far-future ideals, sciences, and technologies while remaining within the realms of current possibility.

When done without a certain sense of grace, timing, and ability for relating lengthy expositions of science to plot, character, and setting, “hard” sci-fi can be difficult and overwhelming to read, occasionally preachy if the author tries to explain too much, and generally drag on. However, when done well, “hard” sci-fi is a wonderful creation, something that teaches its readers, explores the world through the lenses of science, and portrays science as a general positive thing (something we all need in this world).

Examples: Leviathan Wakes (The Expanse series) by James S. A. Corey, Ancillary Justice (Imperial Radch series) by Ann Leckie, The Martian by Andy Weir, Ringworld (series) by Larry Niven, vN by Madeline Ashby, Up Against It by M. J. Locke, Diaspora by Greg Egan, Remnant Population by Elizabeth Moon, A Door Into Ocean (Elysium series) by Joan Slonczewski, Downbelow Station (The Company Wars series) by C. J. Cherryh, The Bohr Maker (the Nanotech Succession series) by Linda Nagata, Lilith’s Brood (Xenogenesis Trilogy: Dawn, Adulthood Rites, Imago) by Octavia E. Butler

“Lost Worlds”: A lesser known subgenre, “Lost Worlds” is characterized by the discovery of a new “world” (i.e, planet, galaxy, continent) that is “out of time, place, or both”- meaning that the world is generally untouched by anything other than native flora and fauna, or that the civilizations there have never been seen before and were isolated from everyone else, or that the remnants of a civilization have been found there. This subgenre came into popularity when people started finding actual remnants of previous civilizations- the Mayan temples, Egyptian tombs, etc- and began speculating about it and using it for fictional purposes.

Common tropes in this subgenre include, unfortunately, things like references to colonization and “a more advanced civilization meets a less advanced civilization”, in terms of technology/science/weapons. On the positive side, tropes can also include exploration and travel throughout the world, survival tactics while within inhospitable lands, archaeological intrigue and findings, and good anthropological ideals where newcomers are curious and respectful of their cultures they come across, science fiction mixed with social sciences (anthropological science fiction is a subgenre that will come up in a later post!), and sometimes some pretty Star Trek-like stuff.

Examples: Dinotopia (series) by James Gurney, The Lost World by Arthur Conan Doyle, Journey to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne, Pym by Mat Johnson

Military Sci-Fi: This sci-fi subgenre is pretty self-explanatory- military sci-fi is characterized by a militarized setting, generally with characters within a military organization/army. The sci-fi part tends to come along with the futuristic technologies being applied to weaponry, battleships, and military tech, and in that the settings of these battles, wars, or general military outposts tend to be in space (on a spaceship) or on a different planet. Oftentimes the battle being waged is against alien species, or if it’s far enough in the future, it might be against other humans that are on a different planet/colony/outpost.

Common tropes in this subgenre include political maneuverings amongst the higher-ups of this military or the people causing the war, characters that are soldiers and/or act out of interest in this war, (have military training, follow military orders, carry out missions, etc), war, fighting, and weaponry tactics discussed in the writing, traditional personality traits for military personnel (such as self-sacrifice, deep loyalty between soldiers, obedience and duty, bravery, and respect as well as disobeying orders to act in the interest of others), and spaceships taking the place of tanks, planes, or battleships of today.

Military sci-fi can often overlap with the “space opera” genre- it speculates about the future and future wars, uses futuristic weaponry and ships, and is often large-scale in terms of the battle layouts and how/where the battle affects people and places.

This subgenre is often used to show the political dynamics of a world or the future, how humans might react to meeting alien species (hopefully hostile, otherwise this subgenre would get pretty ugly), and how the military and corporations, government, and agendas expand into space.

Examples: Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee, Mechanical Failure (Epic Failure series) by Joe Zieja, Valor’s Choice (Confederation series) by Tanya Huff, Vatta’s War (series) by Elizabeth Moon, Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card, Starship Troopers by Robert A. Heinlein, The Red by Linda Nagata, Unbreakable by W. C. Bauers, Terms of Enlistment (series) by Marko Kloos, War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells, Fortune’s Pawn by Rachel Bach

Mundane Sci-Fi: This subgenre can be a bit iffy, depending on how you view it. Generally, it’s described as sci-fi that doesn’t use “high claims” such as faster-than-light travel or aliens, but rather focuses on down-to-Earth (literally) works that use only believable technology and science from the modern day. Therefore, it’s considered an extension of hard sci-fi, but even more legitimized than that- where hard sci-fi can hypothesize about “high claims” of worm holes and interstellar travel while using a strong basis in science, mundane sci-fi drops that altogether and sticks only to what is known to be plausible.

Common tropes in this subgenre include hard sci-fi principles, technologies and science based upon proven fact and areas of study existing today, and no speculative technologies.

This subgenre is, to me, something to be viewed both positively and negatively. On one hand, mundane science fiction promotes the idea of focusing only on current science/technology, rather than speculating about things such as warp drives and spaceships and intergalactic communities, because thinking about such ideas leads to negligence of the current issues we- and the planet- already face. That’s not a bad thing- focusing on current issues are definitely something that should be done, and ignoring them won’t help anyone- but the mundane sci-fi community also claims, in some areas, that science fiction as a whole should abandon the ideas of space travel and a lot of the typical themes because it’s wrong to speculate on such ideals and it’s “running away from the problem”. Take that as you will- there’s been a bit of an argument, so to speak, on the matter.

Overall, the subgenre of mundane sci-fi is meant to show current science and technology through a fictional lens, the effects of current events such as climate change, biotechnology, global politics, and advancing robotics, how the world is changing in the now, “reawaken” the sense of wonder people feel towards sci-fi in the context of Earth alone, and bring in high levels of characterization and plot that are inherently realistic.

Examples: Air by Geoff Ryman, Schismatrix by Bruce Sterling, The Beast with Nine Billion Feet by Anil Menon, The Hacker and the Ants by Rudy Rucker, Red Mars by Kim Stanley Robinson, Arctic Rising by Tobias S. Buckell

New Wave Sci-Fi: Also a social and cultural movement as well as a literary one, “new wave sci-fi” doesn’t have as much bearing today in terms of being written as often (in the same way as it was then, at the very least). This subgenre came about in the 60′s and 70′s, and it’s characterized as being “advant-garde” and “experimental” in the context of literature and art- it was more focused on being new and exciting and unique rather than purely accurate, scientifically speaking. However, this period of time is also what saw a large increase in science fiction in mainstream culture, as well as more writers and readers- the subject itself shifted to become more aware of things such as language, politics, subject matter, writing techniques, and futuristic ideals. There’s quite a large historical movement there, which I could get into later, but for now I’m gonna stick with the literary stuff.

Common tropes in this subgenre (there are lots) include rejection of classic sci-fi ideals (the Antihero, for instance, came about in sci-fi as a rejection of the typical “science hero”), deconstruction of regular themes, rejection of typical plots and “happy” endings, blurred boundaries between science fiction and fantasy (science fantasy is a subgenre I’ll also get into later!), and high amounts of progressive ideals (this was in the 60′s and 70′s- free-love, equality, and inclusiveness was, and is, a major part of the writing in this subgenre.

Much of what science fiction is now is owed, at least in part, to the new wave literary movement for science fiction. The genre was more open for women and minorities (to an extent), the stories more all-encompassing, the themes more substantial, dynamic, and fluid- overall, it helped set the course for a lot of what sci-fi is now.

Examples: Dhalgren by Samuel R. Delaney, The Forever War by Joe Haldeman, The Elric Saga (series) by Michael Moorcock, Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut, And Chaos Died by Joanna Russ, The Hieros Gamos of Sam and An Smith by Josephine Saxton, The Lathe of Heaven by Ursula K. Le Guin

And that’s about it! The next installment, “Science Fiction Subgenres from P to Z”, should be up in a day or two- after that, I’ll be moving onto Fantasy Subgenres (the Part 2 of the series). I’ll start adding links as I write them- in the meantime, feel free to send me questions or thoughts about these subgenres and anything else!

Parting thoughts- are any of these subgenres completely new to you? Can you think of any other novels in any of them? Does your writing fall under any of these subgenres?

#ugh this took forever#apocalyptic sci-fi#dying earth#edisonade#hard sci-fi#lost worlds#military sci-fi#mundane sci-fi#new wave sci-fi#science fiction#sci-fi#writing#book recommendations#subgenres#sci-fi subgenres#from a to n#masterlist#writing help#tropes

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I dunno about the likelihood of that last bit as I’m naturally not familiar with California zoning laws circa 1985, but I do know that in the Texas town I just moved away from there’s a really stubborn one story cottage on the main drag that’s otherwise entirely business zoned that refuses to sell so Doc’s converted garage may not have had to register as a fake business to remain where his family mansion was if Cali zoning laws were similar in the 80s.

I think, and this admitted does only work when you take what was established in the sequels into account, Doc was probably trying to be like the science heroes of Verne and the various Edisonades and other 19th/early 20th century scifi stories he grew up on and he probably established that business either around the time of or even before the 1955 events of the first movie and just realized over the years that that’s not really a thing and also just because you were a Manhattan Project researcher does not mean you can just do Science™️ which led to the business probably being a combination money laundering front and genuine random repair service

u know what we don't talk about enough

this. what does this mean?? '24 HR scientific services'?? what services? is he just for hire? is he a scientist for hire? what in the world do people hire their local disgraced nuclear physicist to do??

15K notes

·

View notes

Photo

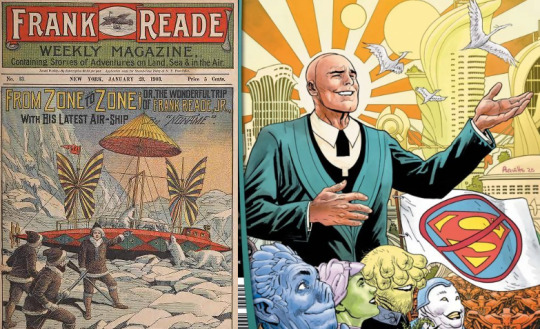

A quick sketch. This is an extrapolation of the Edisonade subgenre of early science fiction. The term Edisonade was coined in the 1990s and is defined like thus:

"a paradigm kind of science fiction in which a brave young inventor creates a tool or a weapon (or both) that enables him to save the girl and his nation (America) and the world from some menace, whether it be foreigners or evil scientists or aliens; and gets the girl; and gets rich."

The first of this type of story was The Steam Man of the Prairies, in which hunchbacked boy genius Johnny Brainerd invents a mechanical man to pull his cart across America where he and his friends fight Native Americans and such (did I mention this subgenre tended to be very xenophobic?). The Steam Man is described like thus:

"It was about ten feet in height, measuring to the top of the 'stove-pipe hat,' which was fashioned after the common order of felt coverings, with a broad brim, all painted a shiny black. The face was made of iron, painted a black color, with a pair of fearful eves, and a tremendous grinning mouth. A whistle-like contrivance was trade to answer for the nose. The steam chest proper and boiler, were where the chest in a human being is generally supposed to be, extending also into a large knapsack arrangement over the shoulders and back. A pair of arms, like projections, held the shafts, and the broad flat feet were covered with sharp spikes, as though he were the monarch of base-ball players. The legs were quite long, and the step was natural, except when running, at which time, the bolt uprightness in the figure showed different from a human being."

Subsequent Edisonades feature characters like Frank Reade, Tom Edison Jr, Jack Wright, Electric Bob, and Tom Swift, and features inventions such as steam-powered horses, giant ostriches, fishlike submarines, and the electric rifle (which the taser was named after, it being an acronym for Tomas A. Swift's Electric Rifle).

The Edisonade was largely confined to the Victorian era and the early 20th century, so I thought I'd take that and see how it would have advanced into World War One, with steam being replaced by diesel power.

After the Americans enter the war in its last year, they bring with them good ole' American ingenuity (and its capacity for destruction). The Diesel Men quickly supplanted tanks in the war, and subsequent American wars (WW2, Korea, The Soatseran Mars War, and the War of Olympus Mons, among others). Unlike the original Steam Man, which merely pulled a cart at high speed, the Diesel Men are fully functional vehicles and battle-suits with cockpits in the torso.

If I find the time, I might take this design out of the Dieselpunk era and take it into different eras like 50s/60s Atompunk and so on.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Read your post on "disruptors", loved it, and made me wonder why so many have a cult of personality spring up around them. Were there similar cults of personality for the mega wealthy in the past; like was Rockefeller worshiped the way so many worship Musk? Or is it a more modern trend fuelled by our constant connectivity and consumption of media? Thanks!

You raise an interesting question.

It was certainly true that the robber barons of the 19th century - Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Carnegie, Morgan, Gould, Frick, etc. - were larger-than-life figures in the media (especially the part of the media that covered high society). It is also true that with a lot of these figures, there was this popular myth of the self-made man that sought to turn them into quintessential rags-to-riches, up-by-your-bootstraps American sucess stories.

But for the most part, the robber barons of the Gilded Age were hated for their monopolistic behavior and their use of violence to suppress the working class - and these magnates often had to go to great lengths to repair their reputations. Andre Carnegie's library-building campaign, for example, was very much a PR move meant to soften his image after the Homestead Strike. In fact, my great-grandfather Humphrey Attewell helped to organize opposition to the construction of a Carnegie library in Northampton, because he and other working-class people felt that the funds for the library were blood money distributed by a murderer. Likewise, it's not an accident that John D. Rockefeller founded the Rockefeller Foundation right around the same time that the Ludlow Massacre turned him into a monster in the eyes of the American public.

I would argue that we start to see more of a cult of personality around the mega-wealthy a bit later - say, 1900s-1930s - and the major turning point was the career of Thomas Edison. While Edison was every bit as ruthless and grasping as the robber barons before him - hence the war of the currents, his penchant for patent theft and/or stealing credit for inventions, the very existence of Hollywood - the fact that he was an inventor with so many world-changing patents to his name made Edison into a very different kind of media figure. Thomas Edison became a star of pulp fiction and dime novels, a sort of proto-superhero Science Hero - in addition to Edison's Conquest of Mars (an unauthorized sequel to the War of the Worlds in which Thomas Edison gets revenge for the Martian invasion of Earth by launching a counter-invasion of the red planet with his superior technology), there was a whole genre of Edisonades all about young inventor geniuses who use their inventions to save the day and/or explore the "savage frontier."

I think you can draw a line from the cult of personality around Edison to the cult of personality that formed around Henry Ford in the 20s and 30s as not just a car manufacturer but a visionary who had created a new age of modernity, and from there to the legend of the Packard garage, and from there to contemporary Silicon Valley.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

really wanna make an animatic for characters I haven't even finished designing yet haha kill me

#a family can be a kid edisonade his nb guardian/robotics engineer and their 3 robot dogs#(edisonade is a mad scientist w/out the evil or mental illness steeotype)#which always bothered me abt the trope#i like this word more

0 notes

Text

This week, I have been mostly reading ‘The Massacre of Mankind’ by Stephen Baxter, published in 2017.

There have been many unauthorized/unofficial sequels to HG Wells’ War of the Worlds. One of the earliest, Edison’s Conquest of Mars, was published less than a year after Wells story. Its notable for being an early example of space opera, and ‘Edisonade’ has become the subgenre of sci-fi in which an inventor creates something that saves the world (I’m surprised Elon Musk isn’t paying more people to write him as the hero… actually shut up – don’t give him ideas). Anyway, Baxter’s novel I believe is the only sequel approved by Wells’ estate.

To get you caught up; toward the end of the 19th century, explosions were seen on the surface of Mars. This it transpires was a fleet being launched to invade Earth – well, actually just the south of the England. I guess it's that Dr Who thing of aliens calculating that all human resistance will crumble if they first make an example of Woking. Which the Martians do, then knock over a few other small towns and villages on their way into London while kicking the butt of the army and navy (one thing I do like in the original story is that the Martians aren’t invulnerable – they just have slightly better tech than the humans, and when one of their machines is destroyed they regroup to come back with a new weapon, allowing the humans to have hope before dashing them). Then the Martians all catch flu and die.

Baxter’s story starts 14 years after the original invasion and the Martians are back, but this time they’re vaccinated. Humans have looted and reverse engineered some Martian technology making for a slightly more even fight, but its still the Martians that have the edge. This is sci-fi, but the science is still rooted in late 19th / early 20th century understanding of the cosmos. I guess its in fact steampunk. In any case, the conflict does go global this time and there are some good bits showing people across the world reacting to the invaders. Baxter also does a good job imitating the period style as well, and there are indeed little references to the aforementioned Edison’s Conquest of Mars, and the infamous Orson Welles radio adaptation of the original story, and more. Can’t say I cared much for the ending though. Like the original, humans never actually defeat the invaders – it takes some other intervention. I don’t want to spoil it – I just thought there were a few holes in what happened.

#science fiction#sci-fi#steampunk#hg wells#stephen baxter#the war of the worlds#the massacre of mankind#am reading

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Might I please jump in with the suggestion that, while making Superman a Pulp Hero can be a little tricky, making LEX LUTHOR a Pulp Hero would be peculiarly easy? (In fact making him a Pulp Hero without making major alterations to his fundamental character might be far more difficult - given how much of a self centred jerk the man is).

Funny you mention that because, while I haven't read the comic enough to really speak much of it, that kinda seems to be the basic premise of Chris Roberson's Edison Rex, a comic about a supervillain who has to step in as Earth's protector after defeating his superhero enemy, with the titular character being a Lex Luthor-analogue who looks like Doc Savage with Thomas Edison's haircut.

In fact, the idea of Thomas Edison as a protagonist is not even a unique one, not when one of the earliest examples of dime novel sci-fi was named after him. Just as popular in it's heyday and irredeemably reprehensible as the man itself even. If you want to imagine how Lex Luthor looks like as a pulp hero, all you need is to look at the genre called "Edisonade", starting in the 1870s, and you'll see why you wouldn't even need to make that many substantial changes to Luthor's fundamental character if you were to try to pass him off as a dime novel sci-fi protagonist. Not just because pulp supervillains already starred in stories and magazines as is, but because Edisonade as a genre is already built to accomodate characters like him.

The term "edisonade" or "Edisonade" – which is derived from Thomas Alva Edison in the same way that "Robinsonade" is derived from the hero of Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe – can be understood to describe any story dating from the late nineteenth century onward and featuring a young US male inventor hero who ingeniously extricates himself from tight spots and who, by so doing, saves himself from defeat and corruption, and his friends and nation from foreign oppressors.

The Invention by which he typically accomplishes this feat is not, however, simply a Weapon, though it will almost certainly prove to be invincible against the foe, and may also make the hero's fortune; it is also a means of Transportation – for the edisonade is not only about saving the country (or planet) through personal spunk and native wit, it is also about lighting out for the Territory.

Afterwards, once the hero has penetrated that virgin strand, he will find yet a further use for his invention: it will serve as a certificate of ownership, for the new Territory will probably be "empty" except for "natives". Magically, the barefoot boy with cheek of tan will discover that he has been made CEO of a compliant world; for a a revelatory set of maxims can be discerned fuelling the entrepreneurial engine of the edisonade: the conviction that to fix is to patent: that to exploit is to own - Sci-Fi Encyclopedia's entry on Edisonade

The Edisonade, coined by critic John Clute after the Robinsonade, can be defined simply enough: it is a story in which a young American male invents a form of transportation and uses it to travel to uncivilized parts of America or the world, enriches himself, and punishes the enemies of the United States, whether domestic (Native Americans) or foreign.

The Edisonades were almost entirely an American creation and appeared in dime novels as serials and as complete novels. They were the single largest category of dime novel science fiction and were the direct ancestors not only of 20th century boys’ fiction characters like Tom Swift but also one of the fathers of early 20th century science fiction, especially in the pulps. And the Edisonades were among the most morally reprehensible works of fiction of the 19th century, on a par with the dime novels the Confederacy published to glorify slavery - Jess Nevins's article on Tom Edison Jr

Fun for the whole family!

Granted (and thankfully), Edisonades as a specific genre died down in popularity following the end of dime novel, although you can very easily see how their influence lingered on much of sci-fi as we know it. It makes for a rather interesting coincidence even that, in the turn of the century, as the dime novels and the Edisonades died down in popularity and the pulp magazines proper started to take their place in American culture, the Mad Scientist began to arise in popularity as a stock villain to the point you can make a drinking game out of reading pulp novels where the kind professor with a weird invention turns out to be a cut-throat master villain.

The Mad Scientist as an archetype, which is what Luthor started as, actually seems pretty much non-existant prior to the 1890s (the term seems to have only caught on somewhere after 1893 following the World's Fair Columbian Exposition) and only really started taking shape in the 1900/1910s following the influence of German Expressionism villains and characters like Fu Manchu (far from the first yellow peril mad scientist, but definitely the most popular) and the myriad of pulp villain, even pulp villain magazines, named after some form of "Doctor" (Doctor Death, Doctor Satan, Doctor X, etc)

I'm not particularly fond of Arch-Capitalist Luthor and I'm not gonna be the billionth guy online to talk about the relevance of that take on Luthor, because my preferred take on Luthor is more on the Emperor Scientist / Ubermensch Arch-Asshole, the kind that's not so much a stock villain archetype because he doesn't have to be, because "Lex Luthor" has practically become it's own archetype, you know it when you see it. I would prefer to emphasize a Luthor who's got more in common with pulp sci-fi supervillains who starred in their own stories, but the stories themselves had no delusions about what the characters were. And I think Luthor can make one hell of a protagonist in this regard.

In another place, under different circumstances, this man might have been a Caesar, a Napoleon, a Hitler, or an Archimedes, a Michelangelo, a da Vinci. A Gautama, a Hammurabi, Gandhi. But in this place, at this time, he was more. Superman made him more.

As an artist saw objects as an amalgam of shapes, as a writer looked upon life as a series of incidents from which plots and characters could be constructed, Lex Luthor's mind divided the Universe into a finite number of mathematical units.

The time he had spent in jail so far this year was three months of thirty days each, three weeks, six days, two hours, and sixteen minutes. This included four weeks, one day, and three hours in solitary confinement during which time he could do nothing more useful than count seconds and scrupulously retain his sanity.

There were other super-criminal geniuses in the world; he had met some of them, dealt with them on occasion. They were chairmen of great corporations, grand masters of martial arts disciplines, heads of departments in executive branches of governments, princes, presidents, prelates, and a saint or two. Unlike Luthor, these men and women chose to retain their respectability. They had trouble coping with honesty.

Luthor was not motivated by a desire for money, or power, or beautiful women, or even freedom. In solitary Luthor decided that his motivation was beyond even the love or hate or whatever it was he had for humanity. It was consuming desire for godhood, fired by the unreasonable conviction that such a thing was somehow possible.

He began by being an honest man. He was a criminal and said so. - The Last Son of Krypton, Chapter 12

#replies tag#dc comics#lex luthor#superman#elliot s maggin#last son of krypton#tarrano the conqueror#pulp supervillains

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

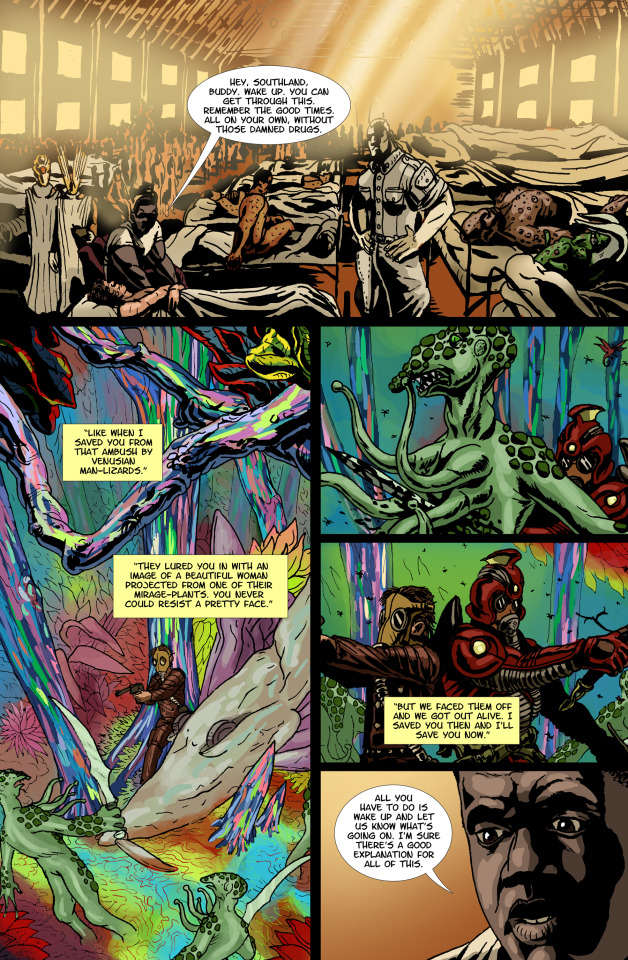

The Apex Society #21 Page 3.

http://apexsociety.thecomicseries.com/

A new episode of my podcast is out! We discuss The Steam Man of the Prairies and the Edisonade subgenre it inspired. Clean cut boy-inventors using new-fangled technology to conquer the frontier for white--er, American interests. Yeah, that's the ticket.

http://neversleepsnetwork.com/podcast/chapter-sixty-manifest-ingenuity/

#art#webcomic#webcomics#comics#make comics#pulp#scifi#pulp scifi#sword and planet#mars#barsoom#venus#creature design#creature#lovecraft#lovecraft mythos

1 note

·

View note

Text

It's set in a universe where all the mass-produced random-house-style pulp-kids-lit books and newbury-award-bait paperbacks, or expies thereof, are true; moreover, to the the protagonist of such a series is a metaphysical state, something that arrests your aging and your personal development for as long as your series remains in the zeitgeist. The protagonist is a quote-unquote ordinary girl whose best friend is the star of a goosebumps-pastiche who (at the time of the series publication in the early oughts) had just very recently within the last ten years had her aging arrested and hadn't noticed yet; her other friend is the protagonist of an edisonade serial from the 40s who's stepford-smiling through his total disconnect from contemporary culture. The protagonist herself has the damocles sword of succumbing to a similar apotheosis through continuing to hang out with these people long enough that she also becomes "interesting." There's the real world and there's the unreal borderland world where the interesting kids-lit genrethings happen and they're kind of superimposed on top of each other, and these people have a foot in each world and it's not quite clear if that's a good or bad thing on net. Fascinating series, I should reread them

No series of children's books had the same long-term impact on my aesthetic sensibilities vis a vis genre fiction, as well as my overall sense of humor, as M.T. Anderson's Pals in Peril series (formerly M.T. Anderson's Thrilling Tales). Anyone remember those things

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

//So an idea that's been suddenly striking me, grown out of what I was trying to do for that heroism/game conference, is looking at depictions of Robots/Androids in media and how that's changed over time/media presentation. Aka, the first depiction would likely be in a novel or play somewhere, though i'm not entirely sure what would be a good start, R.U.R., Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, and a few old Edisonade genre/themed stories come to mind, then the second could be Star Trek The Next Generation's Data, given how well known and popular he is/became (so much so that he was in Picard!), and then the third could be a recent famous video game Detroit: Become Human.

//I want specifically to be able to look at their capability for choices I think, and how that makes them more or less 'human' in their stories and compared to other human characters, but i've also thought about how the change in media presentation allows for more give and take between the characters/stories and the viewers/consumers too, with novels being mostly completed and then presented to people, tv shows sometimes changing plot points based on high viewer reactions, and games (especially this one) being VERY focused on the player's actions, so much so that the whole game changes depending on what the player does.

//idk if this make sense but I haven’t been this excited just to have an IDEA in ages and oh it feels good!

#//ooc#//academics#//i just had to share with you guys because i'm so HAPPY!#//you guys have helped me find my spark for writing again and I could cry tears of joy#//THANK YOU ALL YOU BEAUTIFUL NERDS

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Huge Hunter, or, The Steam Man of the Prairie | Nickels and Dimes | Northern Illinois University Digital Library

This novel by Edward S. Ellis is one of the earliest examples of the Edisonade genre, or stories about boy inventors and adventurers. It’s also one of the earliest novels to feature a mechanical man, likely inspired by the inventions of Zadoc Dederick. Like later examples of the genre, the boy inventor in this story--Johnny Brainerd--uses his mechanical creation to subjugate and terrorize Native Americans. But unlike later examples, this boy inventor is also a dwarf.

Ellis’ novel was very popular, re-issued several times in various series by Beadle and Adams. Editions of this story in Beadle’s American Novels, Beadle’s Half Dime Library, and Beadle’s Pocket Library will be digitized soon as part of the Albert Johannsen project, funded through a Hidden Collections grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources.

Posted by Matthew Short, Metadata Librarian

#dime novels#Beadle's Dime Novels#Albert Johannsen#Albert Johannsen Project#Edward S. Ellis#Steam Man of the Prairie#NIUDL#Edisonades

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

At the ancient site of Hatnub, a quarry in the eastern Egyptian desert not far from Faiyum, archaeologists have recently discovered a sled ramp system used to transport alabaster blocks. Post holes and a ramp with stairs on either side indicate that the contraption allowed Egyptian builders to move heavy blocks up and down steep slopes. Inscriptions have now helped archaeologists from the Institut français d’archéologie orientale and the University of Liverpool to date this groundbreaking technology to at least the reign of Khufu, who ruled from 2589–2566 BCE. Khufu is known as the pharaoh who likely commissioned the building of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Discovery and reconstruction of the ramp allows us to better understand ancient construction techniques. It also chips away at the long-held but fringe theory that the blocks were so heavy and the distances they would have to travel so lengthy that aliens must have built the pyramids.

Where did the theory of aliens building the pyramids actually come from? Since the late 19th century, science fiction writers have imagined Martians and other alien lifeforms engaged in great feats of terrestrial engineering. Earlier alien theories surrounding Atlantis may have spawned fantasies about alien building. The most substantial evidence for non-earthly creatures arrived in the wake of H.G. Wells’s success.

Capitalizing on the fervor surrounding Wells’s The War of the Worlds, astronomer and science fiction writer Garrett P. Serviss penned a quasi-sequel titled Edison’s Conquest of Mars in 1898. Serviss posited that “giants of Mars” had moved large blocks and built the Great Pyramid. He even noted that the Sphinx had Martian features. Edison’s Conquest was part of a number of science fiction works published as books or serialized in newspapers in the late 19th century which imagined alien invasions fought off by great inventors of the time. Thomas Edison was a favored hero in these science fiction fantasies much later collectively called Edisonades.

Continue reading

#the great pyramids#classics#tagamemnon#tagitus#history#ancient history#egyptology#ancient architecture#archaeology#archaeologists#archaeological sites#hatnub#nscriptions#Institut français d’archéologie orientale#University of Liverpool#khufu#pharoah#Great Pyramid at Giza#giza#science fiction#extraterrestrial theories#extraterrestrial#civilisations#ancient civilisations#colonialism#pseudoscientific myths#social issues

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HG Wells’ 1897 story War of the Worlds has gone down in history as a prime example of using science fiction in order to make social critique. Here the socialist, anti-imperialist Wells used the then common genre of “Invasion Fiction“ to demonstrate why colonialism and Social Darwinism are bad, by demonstrating what it might be like to be on the receiving end of it.

Unfortunately, the lesson was kind of lost on some people, leading to American astronomer and writer Garrett P. Serviss to write an unauthorised sequel to the book in 1898, titled Edison’s Conquest of Mars. There the pretense of allegory is dropped in favour of a tale where Thomas Edison back-engineers the Martian’s technology (with Serviss himself appearing to consult him), with the inventor then travelling to Mars to exterminate the Martians and wipe out all traces of their culture.

This warping of the lesson present in Wells’ original story should perhaps be unsurprising, due to the popularity of stories that would later become known as “Edisonades”. These were proto-pulp novels which featured a young inventor (either Edison or someone based on him), who would create some fancy machine and, more often than not, use it to murder indigenous people.

Sadly not everyone was down with the idea of using science fiction to tell stories meant to subtly inform people they were being jerks, and instead would rather write works where steam powered robots and mecha-ostriches are used to oppress people in other countries instead. It’s unsurprising, I guess, but still disappointing.

114 notes

·

View notes