#coast of Crimea

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

20th August 1980: Yalta, Crimea, Ukraine.

#ukrainian history#vintage ukraine#august#soviet union#ussr#yalta#crimea#black and white#20th century#1980#1980s#ukraine#black sea#coast#on this day#vintage photo#vintage

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

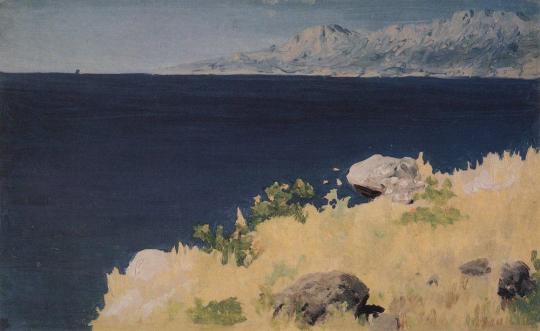

A Moonlit Night on the Crimean Coast by Ivan Aivazovsky

#ivan aivazovsky#art#crimea#crimean#coast#sea#night#moonlit#moonlight#full moon#moon#europe#european#eastern europe

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sickness gripped China's east coast in 1345, and the next year a Mongol army brought the plague to Caffa in Crimea,* the very city from which Marco Polo's uncles had departed for Beijing nearly a century before.

*The chronicler Gabriele de' Mussi (who was in Italy at the time) insisted that the Mongols used catapults to hurl plague-ridden corpses into Caffa. Most historians suspect – more prosaically – that rats carried plague-bearing fleas from the besiegers' camp into the city.

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quotes#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#sickness#china#chinese history#east coast#14th century#mongolian#army#black plague#bubonic plague#caffa#crimea#marco polo#beijing#13th century#gabriele de' mussi

0 notes

Text

I want to make it clear. There is one united, sovereign Ukraine.

This is what the Trump admin is marketing as their “peace plan.” In reality, it’s a defeatist, pathetic, weak, and disgusting betrayal of Ukraine and her sovereignty. Handing Putin eastern Ukraine for no other reason than because Putin took it with force is not only illegal under international law according to the Budapest Memorandum where the West guaranteed Ukraine’s security and territorial integrity. It’s also retroactively legitimizing Russia’s settler colonial policies in Crimea and Donetsk and Luhansk.

This is explicitly and directly offering a reward and incentive for Putin to invade, conquer, and rape more and more of Europe. Do you think he will stop with Ukraine? Russian aggression extends to ALL OF EUROPE.

Russia has cyberattacked Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian digital infrastructure. Russia occupies much of Georgia. Russia interferes in Finnish and Swedish and Romanian elections. Russia blew up a munitions factory in Czechia. Russia shot down a Dutch civilian airliner flying from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur. The Russians poisoned Russian dissidents on British soil, including two British nationals. Russia conducted training for a nuclear bombing of Lisbon… off the coast of Portugal!

To sell out Ukraine is to sell out Europe. All of the EU is threatened by Russian expansionism which will only be *rewarded* by the defeatist vatniks who currently control the U.S. government. Germany was partitioned as punishment for a war they started. This would be partitioning Ukraine for defending themselves in a war they didn’t start. There is only one, undivided, sovereign Ukrainian nation-state.

Stand up for Ukraine!

#ukraine#russia#europe#stop russia#fuck russia#russian war on ukraine#ukraine war#putin#politics#world events#jumblr#world politics#current events#eu#NATO#zelensky

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skiing along the Black Sea coast in Gurzuf, Crimea (1987)

183 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Elon Musk’s company SpaceX is a U.S. defense contractor, with billions of dollars in Pentagon contracts. That makes his intervention to thwart Ukrainian military operations a U.S. national security concern, not only because America supports Ukraine’s self-defense against Russia’s invasion, but also because it suggests the U.S. military may have left itself open to similar disruptions. Excerpts from biographer Walter Isaacson’s book, Elon Musk, show Musk denying Ukraine Starlink internet access off the coast of Crimea in Sept. 2022, causing Ukrainian sea drones to stop functioning. A private citizen thwarting an in-progress military operation like this is unprecedented. [...] Congress should exercise its oversight powers and look into both SpaceX’s actions in Ukraine and the extent of American dependence on Musk’s company. At minimum, it’s an information security risk. Isaacson says Musk texted him about the Ukrainian sea drones headed to Crimea as he was trying to decide what to do. No one should be telling journalists about secret military operations as they’re happening. Elon Musk especially shouldn’t be in position to, given his direct contact with foreign officials, and his apparent affinity for online trolls, including contributors to Russian state media outlet RT. He’s free to associate with whomever he wants, and to express his opinions about the war (even if he doesn’t know what he’s talking about and has vast means to spread his thoughts widely). But a defense contractor controlled by one volatile personality, who is at best ignorant of international power politics and susceptible to Russian propaganda, and does not respect that national security decisions are up to governments rather than him personally, is not someone the United States should consider a reliable business partner.

U.S. Government Can’t Allow Elon Musk the Power to Intervene in Wars

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

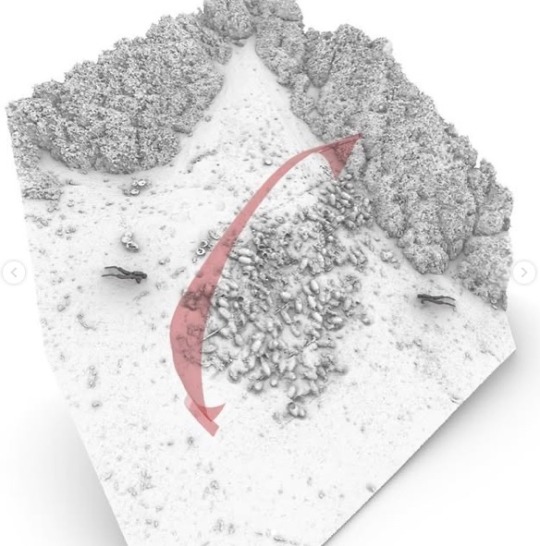

Dozens of Amphorae Recovered From Ancient Byzantine Shipwreck in Greece

Excavations of an ancient Byzantine shipwreck off the coast of Fournoi near Samos, Greece are bringing new finds onto the surface.

The wreck has been systematically excavated since 2021 and has been selected for intensive investigation due to the extremely interesting cargo it carries.

The amphorae found recently in the sand near the wreck, along with the wooden skeleton of the ship itself, were in remarkably good condition. Experts believe that the ship’s wooden framing survived throughout the centuries because it was crushed under the rest of the ship and oxygen couldn’t reach it, stalling the process of decay.

So far eight different amphora types have been recorded, originating from Crimea, Sinope of the Pontus region in the Black Sea, as well as from the Aegean islands and the Phocaean region of Asia Minor.

Pottery recovered at the ancient Byzantine shipwreck

The Ministry of Culture said that 170 group dives were carried out during the latest excavations. Archaeologists worked throughout the period to clear sand and debris from the wreck to provide access for experts to conduct studies of the site.

The scattering of the finds on the seabed seems to indicate a partial loss of cargo before the ship sank.

The recovered pottery was particularly enlightening, in terms of the more precise chronological inclusion of the wreck, which can now be safely dated between 480 and 520 AD, probably during the years of Emperor Anastasios I (491 – 518 AD), said a press release by the Greek Ministry of Culture.

Byzantine Emperor Anastasios I is known for his fiscal and monetary reforms, which strengthened the Empire’s coffers and enabled the expansionist policy of the emperors of the 6th century.

In parallel with the excavation of the wreck, findings from three more wrecks at the Fournoi archipelago were recovered, which are intended to be exhibited at the local archeological museum. Among these finds are a giant archaic anchor obelisk and amphorae from shipwrecks of the 6th to 8th centuries AD.

Countless ancient shipwrecks off Greece

There are many ancient shipwrecks across the Greek seas, and archaeologists have found countless historic treasures in these sunken archaeological sites.

In March 2024, the Ministry of Culture announced that scientists have discovered several shipwrecks and other important ancient finds in the underwater, near Greece’s island of Kasos.

These date back indicatively from prehistory (3000 BC), the Classical period (460 BC), the Hellenistic (100 BC to 100 AD), and the Roman years (200 BC – 300 AD) to the medieval and Ottoman periods.

Four stunning ancient shipwrecks filled with artifacts from antiquity and the Roman and Byzantine eras off central Greece can now be explored by amateur divers.

“We plan to highlight our marine cultural heritage,” Culture Minister Lina Mendoni said.

“We have responded to this great challenge by opening to the public a total of four underwater archaeological sites in the prefecture of Magnesia, which will allow Greece to join the world map of diving tourism.”

By Tasos Kokkinidis.

#Dozens of Amphorae Recovered From Ancient Byzantine Shipwreck in Greece#coast of Fournoi#ancient shipwreck#ancient amphorae#ancient artifacts#archeology#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#byzantine history#byzantine empire

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

-Sailing off the coast of the Crimea in the moonlit night-

373 notes

·

View notes

Text

Partenit. Southern coast of Crimea. 1910s. by Serhii Vasylkivskyi (1854–1917).

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman the Magnificent (aka Süleyman I or Suleiman I, r. 1520-1566) was the tenth and longest-reigning sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Hailed as a skilled military commander, a just ruler, and a divinely anointed monarch during his lifetime, his realm extended from Hungary to Iran, and from Crimea to North Africa and the Indian Ocean. As he engaged in bitter rivalries with the Catholic Habsburgs and the Shiite Safavids, he presided over a multilingual and multireligious empire that promised peace and prosperity to its subjects.

Early Life

Suleiman was born in 1494 or 1495 in Trabzon, on the Black Sea coast. His father Selim served there as provincial governor, and his mother Hafsa was a concubine in his father's harem. Suleiman grew up in a multiethnic, multireligious town. While he led a privileged life, he also lived in a district where contagious diseases and food scarcity were rampant, even for the upper classes. He received an elite education under the supervision of tutors, including a strong poetic formation. He also received martial training, and he remained an avid and skilled horseman and hunter to the end of his life.

Suleiman's adolescence and youth were spent under the shadow of his father Selim, a violent, overbearing man. As he reached puberty, like other Ottoman princes, he became eligible for service as district governor. Following a tense negotiation between his father and the palace, he was appointed to Caffa, in the Crimean Peninsula. His father Selim subsequently used Caffa as a center of operations in his bid to replace the ruling sultan, Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512). After becoming sultan in 1512, Selim I (r. 1512-1520) killed his brothers and nephews, stopped the advance of the millenarian Safavid movement into the Ottoman territories by defeating its leader Ismail in 1514, and occupied the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt in 1516-17.

After his father Selim came to the throne, Suleiman was given another district governorship in western Anatolia. The resources at his disposal increased considerably, as he came to preside over a crowded household as the heir apparent. During Selim's campaigns, he acted as his father's proxy by relocating to Edirne, the gateway to the Balkan provinces, where he became acquainted with the management of the empire at the highest level.

These were the years during which Suleiman began stepping into the limelight of Ottoman political and cultural life. He began writing poetry, a sign of intellectual maturity as well cultural refinement. He also began having children with his concubines, securing the reproduction of the Ottoman dynasty, and transitioning from adolescence into fatherhood.

Author Promotion

Continue reading...

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

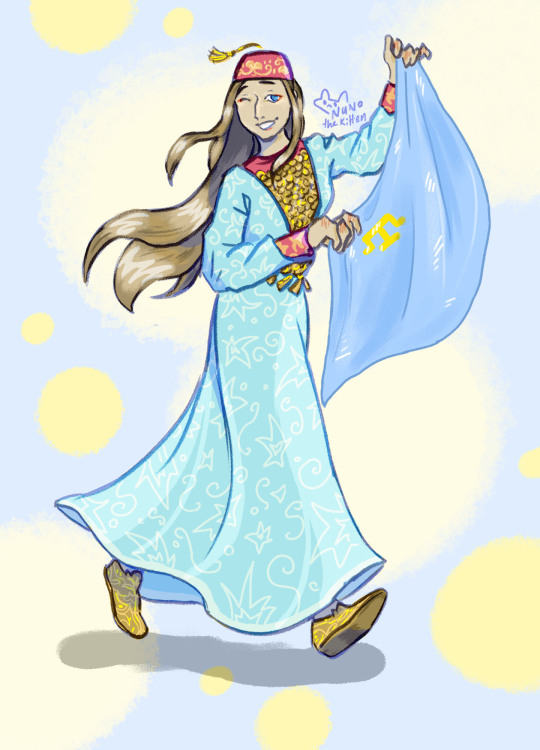

Prompts used: • Respecting indigenous peoples • Clothing and accessories • History @yourcubitoyourculture

Presenting Pearlescentmoon in Crimean Tatar national costume and with their flag!

Crimea is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov.

After Ukrainian independence in 1991, the central government and the Republic of Crimea clashed, with the region being granted more autonomy. In 2014, the peninsula was occupied by Russian forces and annexed by Russia, but most countries recognise Crimea as Ukrainian territory.

Throughout history, Crimean Tatars suffered from Russia, one of the largest tragedies being Deportation of Crimean Tatars 1944, when the majority of Crimean population were forecully deported from their homeland to the Uzbek SSR.

Crimean Tatar singer Jamala told the world about it in Eurovision 2016, two years after Russia occupied Crimea once again, with the song named "1944". (watch her performance here)

Crimean Tatar language is on the verge of being forgotten, and less people know about Crimean Tatars even existing, so please, educate yourself, tell others about it, share, talk, don't let all the people who fought agains their opressors die for nothing.

#nuno draws#your cubito your culture 2024#your cubito your culture#hermitcraft#hermitcraft fanart#pearl hermitcraft#pearlecentmoon fanart#pearlescentmoon fanart#pearlescentmoon#hermitblr#mcyt#mcyt fanart#crimea#crimean tatars#qirim

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

11th March: Cats and fishing boats. 2010 in Balaklava, Crimea, Ukraine. X

#cats#crimea#ukraine#coast#fishing boats#black sea#eastern europe#balaklava#march#on this day#crimea is ukraine#boats

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm trying to write these earlier in the day.

I used to put off writing until I finished the smaller, more tractable tasks I set for myself. But by the time I finished the little things, I had no energy for writing.

Now, though, I find I don't have the energy for the little things if I start writing too late in the day. If I start writing late enough, I don't have the energy to exercise.

It's 10:15 a.m. Let's see if I can't finish this with energy to spare.

I.

I write to you from San Francisco, a small town on the Pacific Coast of California, servicing a patchwork of commuter suburbs around what we call the "San Francisco Bay Area."

Back in the 1950s, they called the City "Baghdad by the Bay," after its profound ethnic and religious divides, low-intensity urban warfare, and decrepit public infrastructure.

It's awful. Even here in the Green Zone.

II.

Americans like to say that San Francisco has a "Mediterranean" climate. And it's true that it has a K��ppen climate classification of Csb, which we call a "warm-summer Mediterranean climate."

Köppen is a three-tier classification scheme. It designates climates by three-letter labels, with each letter dividing the world into finer and finer categories.

The first Köppen letter divides the world into five parts, each designated by the first five letters of the alphabet: tropical A; arid B; temperate C; cold D; and polar E.

Four of the five letters separate the world into mutually-exclusive categories by mean temperatures in the hottest and coldest months, making for a neat algorithm.

If it's above 10ºC in the coldest month, it's tropical A, else:

If it's above 0ºC in the coldest month, it's temperate C, else:

If it's above 10ºC in the hottest month, it's cold D, else:

If it's below 10ºC in the hottest month, it's polar E.

Arid B is an irregularity. It's based on a precipitation threshold, not mean monthly temperatures. It's also hard to characterize in a single phrase, since it varies with the seasonality of the precipitation. It's higher if the precipitation comes in warm months.

But never mind that. It's not arid in San Francisco. That's part of the problem.

In San Francisco's Csb, C stands for temperate, s for dry summer, and b for warm summer.

Temperate means it averages above 10ºC in the hottest month and between 0ºC and 18ºC in its coldest; dry summer means it gets less than 40 mm of precipitation in its driest month; and warm summer means it averages below 22ºC in the hottest month, but above 10ºC for more than four months each year.

Now, is that Mediterranean? It's not obvious to me that it is. Let's go to the map.

III.

Here's beautiful California, in all its climatic variation, courtesy of our friends at the Köppen-Geiger Explorer:

Let's start in the Los Angeles basin, along the borderlands between the yellow and sienna towards the bottom of the map.

Los Angeles divides into three primary climate regions, which provide a useful key to the California experience.

The coast of western Los Angeles, from Santa Monica down to Palos Verdes, and continuing along the coast of Orange County to the south, is a cold, semi-arid steppe, or Bsk.

It's a climate it shares with Colorado Springs, the Texas panhandle, and a swathe of the Eurasian steppe lands, from Crimea to Volgograd to Inner Mongolia.

South and central Los Angeles, south of the 10, but extending northeast to a frontier in Culver City, Mid-Wilshire, and Koreatown, and south through Anaheim and Garden Grove to Irvine, is a hot, semi-arid steppe, or Bsh.

It's a climate it shares with Gaza, the West Bank of the Jordan, Mosul, the Zagros foothills of Khuzestan, Amritsar, and the northern, or Turkish, part of Cyprus.

North of that, extending from downtown across the mountains into the San Fernando Valley, and east across the river to El Monte, Pomona, and Rancho Cucamonga, is the last part of Los Angeles, the hot-summer Mediterranean, or Csa.

This climate, the climate of Glendale and Pasadena, of Burbank and Sherman Oaks, of Van Nuys, Encino, and Calabasas, is what I think of as the actual Mediterranean climate.

Because it's the climate of the actual Mediterranean.

It's a climate it shares with Athens and Rome, Syracuse and Tunis, Jerusalem and Jaffa, Florence and Naples, but not, significantly, a climate it shares with San Francisco.

Because it's too warm for the city by the Bay.

IV.

Now let's look north, to the Golden Gate.

Here you can see that the Bay Area is, as you might have guessed, a homogeneous and indistinct stain on the map of California.

Does it have semiarid steppe lands? No. Does it have hot summers? No. From the South Bay to the Valley, from the West Side to the East Side, everyone has the same climate, and nobody's very happy.

San Francisco shares a climate with Oakland which shares a climate with Mountain View which shares a climate with Sausalito which shares a climate with San Jose which shares a climate with Berkeley and Richmond. It's a climate that stretches, like an open sore, down to Santa Cruz and Monterey.

It's all the same fucking climate.

It's called, as you may recall, the warm-summer Mediterranean climate, or Csb. Not hot summer. Not the summer of Glendale or Pasadena. No. A warm summer.

How warm is a warm summer? Is that a Mediterranean kind of summer? Is that the kind of summer you get in the south of France or the Greek islands? Well, no.

You know who else has a warm summer?

Fucking Galicia, that's who. The Parnassus Mountains. Mount fucking Lebanon.

You know who else has this fucking climate?

The Pacific fucking Northwest. Because it's cold and wet there. Just like San Francisco.

VI.

San Francisco: It's cold and damp!

I fucking hate it.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

-Sea coast, Crimea-

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Excerpt from this story from The Revelator:

On Dec. 15, 2024, in a raging storm, two Russian oil tankers carrying more than 9,000 tons of heavy oil collided off the coast of Port Taman in the Kerch Strait in the Black Sea. A video posted to Telegram allegedly depicting the crash shows one of the tankers, with a broken bow, sinking into the sea. The second vessel reportedly ran aground closer to the port.

The crash spilled thousands of tons of toxic heavy fuel oil and has harmed thousands of birds, dozens of dolphins, and other animals, and resulted in a state of emergency in Crimea. By mid-January the fuel had spread far enough that it could be seen from space. Satellite images studied by Greenpeace show coastal contamination stretching from Novorossiysk in the Krasnodar Krai to Ozero Donuzlav in the western coast of Russian-occupied Crimea. Even Russian president Vladimir Putin called the disaster “one of the most serious environmental challenges we have faced in recent years.”

For a region accustomed to rough seas and choppy weather, this accident, while unfortunate, was not uncommon. Experts have raised alarms about Russian tankers in the region for years, following previous accidents that caused smaller but still significant spills.

With this new crash continuing to cause damage, experts and activists warn that the region remains heavily militarized and under the control of the corrupt, autocratic Russian government, making response to the oil spill increasingly challenging.

This has left a vacuum in disaster response, filled sparingly by local volunteers who’ve worked for three months to mitigate the damage.

The problems facing volunteers are not just logistical. The nature of the fuel they’re attempting to clear is itself problematic.

“Fuel oil is quite heavy, so it sinks,” Anna explained. “But if the temperature rises or there are storms, it rises in the water and hits the shorelines again.”

The vessels carried mazut, a type of low-quality heavy fuel oil that can be very difficult to clean in a spill.

“Heavy fuel oil, also known as residual fuel, is what’s left at the end of the refining process,” explained Sian Prior, a marine science expert and lead adviser to the Clean Arctic Alliance, an organization that has advocated for tighter rules on fossil-fuel shipments in the region. “It’s used by a lot of ships in many different parts of the world. Most of the heavy fuels also have very high sulfur levels, which when burned releases sulfur oxides, which is bad for health and the environment.”

In 2020 the International Maritime Organization, which regulates global commercial shipping, introduced a limit on the amount of sulfur allowed in the fuel.

But the fuel industry responded by blending fuels, mixing lighter fuels with heavy fuel to create a product that has low sulfur but still has a lot of heavy residual fuel, Prior said.

The resulting mix poses several challenges after spills. “It’s very difficult to clean up, because it’s very viscous and emulsifies when it mixes with water, so its volumes actually increase,” she said. “Once this fuel is spilled … it’s virtually impossible to clean it up adequately.”

The effects of a mazut spill could be worse than regular oil spills, which in themselves are disastrous.

“The lighter fuels, distillate fuels, will break up much more quickly in the environment,” Prior explains.

11 notes

·

View notes