#clotilda

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

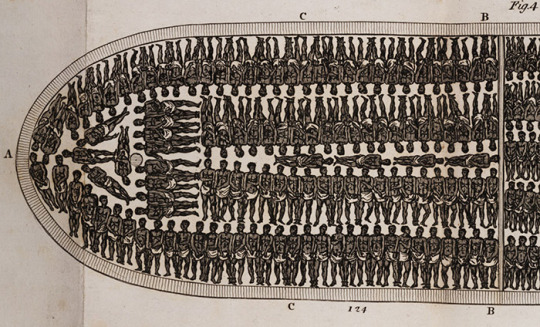

What happened to slave ships?

After the transatlantic slave trade was outlawed, most slave ships were either scrapped or deliberately sunk to hide evidence of their illegal activity, with some notable examples like the "Clotilda" being scuttled and burned upon reaching the United States to avoid prosecution; today, researchers are working to locate and study the wrecks of these ships to understand the history of the slave trade further

Key points about slave ships after the trade was banned:

Legal repercussions:Once the slave trade was outlawed, any ship caught transporting enslaved people was considered a pirate vessel and subject to capture by naval forces like the British Royal Navy or the U.S. Navy.

Hiding evidence:To avoid legal consequences, many slave ship captains would deliberately sink their vessels after unloading their human cargo, often burning them to destroy evidence of their illegal activity.

The "Clotilda" example:The most famous example of a slave ship that was deliberately sunk is the "Clotilda," which was the last known slave ship to enter the United States and was later discovered submerged in the Mobile River in Alabama.

Modern efforts to study shipwrecks:Today, maritime archaeologists are actively searching for and studying the wreckage of slave ships to learn more about the history of the transatlantic slave trade.

#slave ships#ships#atlantic slave trade#slave trade#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brown skin#afrakans#brownskin#amistad#clotida#Clotilda#La Amistad#elizabeth#Meermin#Beeckestijn#Marie Séraphique#Friendship#Jesus of Lübeck#Whydah Gally#USS Nightingale#Trouvadore#Tecora

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Last Ship to Bring Enslaved Africans to America Arrived in 1860 - the Clotilda

#The Last Ship to Bring Enslaved Africans to America Arrived in 1860#clotilda#slavery in america#alabama#mobile#Africatown#Codjo lewis#baracoon#Youtube

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hi! Local archaeologist here!

This story involves a place just north of Mobile, Alabama, called Africatown, so named by the above mentioned Cudjo Lewis (also known as Kossola before he took an American name) and the other survivors of the Clotilda, the last slave ship to ferry enslaved Africans into the United States. The Clotilda was smuggled in to Mobile Bay one night in 1860 (already illegal in the U.S. at the time), where it's cargo of 110 West Africans from Dahomey and the surrounding region was offloaded in secret and divided amongst the wealthy white slave-owners that commissioned and ran the voyage, namely Timothy Meaher and William Foster. With Emancipation in 1863 and the end of the Civil War (Mobile briefly being occupied with Union troops) in 1865/66, the Clotilda survivors found themselves free people. They joined together and saved up $1000 to charter voyage back to West Africa before being told by their former masters that a voyage back would be much more expensive and not at all profitable. So instead, Cudjo and the others used that money and more to purchase land, establishing their community of Africatown, where they could speak their own language, live under their own local government, farm and have children, and eventually become americanized.

Africatown still exists today, but it has had a very tragic history of environmental and racial injustice. It is overwhelmed with industry (chemical refineries, asphalt plants, pipe and metal manufacturers, paper mills, and more), which has caused a serious health and cancer epidemic. MUCH OF THE LAND HERE IS STILL OWNED BY DESCENDANTS OF THE MEAHER FAMILY. Yet, the town is revitalizing its own culture history with the rediscovery of the Clotilda's remains, including the construction of a new heritage center and archaeological work. If you're at all interested in this story, then read the book published from Zora Neale Hurston's work called Barracoon or Nick Tabor's Africatown: America's Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created. Consider visiting these sites and others to lend your support.

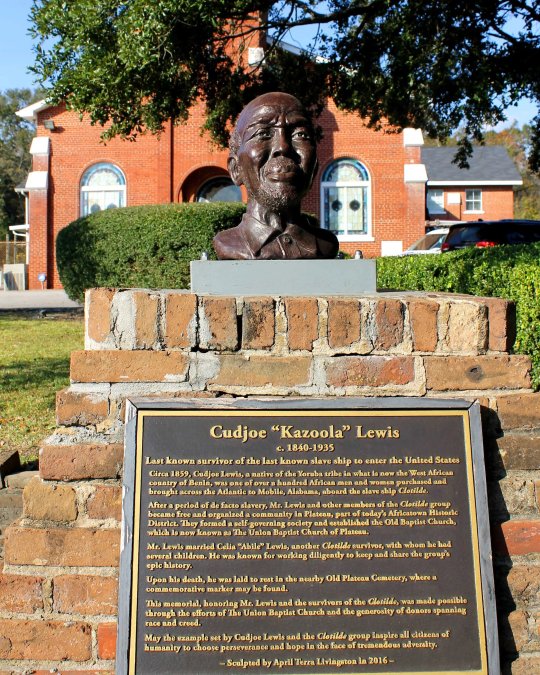

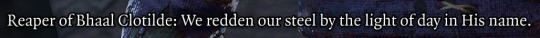

Cudjo Lewis, the last surviving captive of the last slave ship to bring Africans to the U.S.

https://www.history.com/news/zora-neale-hurston-barracoon-slave-clotilda-survivor?utm_campaign=Echobox&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter#link_time=1525373347

156K notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 8, 1860, more than 50 years after Congress banned the trafficking of enslaved Africans into the U.S., the ship Clotilda arrived in Mobile, Alabama, carrying more than 100 enslaved people from West Africa. Captain William Foster commanded the boat and was later said to be working for Timothy Meaher, a white Mobile shipyard owner who built the Clotilda.

Captain Foster evaded capture by federal authorities by transferring the enslaved Africans to a riverboat and burning and then sinking the Clotilda. The smuggled Africans were subsequently distributed as enslaved property amongst the group of white men who had financed the voyage. Mr. Meaher kept more than 30 of the Africans on Magazine Point, his property north of Mobile. One of those Africans was a man who came to be known as Cudjo Lewis.

In 1861, Mr. Meaher and his partners were prosecuted for illegally trafficking the Africans into the country, but a federal court dismissed the case as the Civil War began. No investigation or remedy ever involved the actual African men and women central to the case; while the federal case was pending, the Africans Mr. Meaher had claimed remained on his property left to fend for themselves and were offered no means of returning to Ghana.

In 1865, after the Civil War ended and slavery was widely abolished, the Clotilda survivors once held by Mr. Meaher were free—but still trapped in a foreign land far from their home. They settled along the outskirts of Mr. Meaher’s property, at a site that came to be known as “Africatown,” and developed a community modeled after the traditions and government they had been forced to leave behind. Unlike the vast majority of newly freed Black people in the country, who had either been born in the U.S. or seized from Africa many decades before, the people of Africatown had a direct, recent connection to their African roots and vivid memories of their culture, language, and customs. Well into the 1950s, descendants of the Clotilda passengers living in Africatown maintained a distinct language and unique community of survival.

Cudjo Lewis lived to be the last surviving Clotilda passenger in Africatown. In 1927, Black anthropologist and writer Zora Neale Hurston traveled to Alabama to interview Mr. Lewis about his life and produced a manuscript documenting his story. The book was not published in her lifetime, but in 2018, the story was released as Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo. Today, many descendants of the Africans trafficked on the Clotilda continue to live in northern Mobile, and in December 2012, the National Park Service added the Africatown Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places.

#history#white history#us history#am yisrael chai#jumblr#republicans#black history#democrats#Captain William Foster#Timothy Meaher#Clotilda#Civil War

0 notes

Text

St. Clotilda. Unknown artist.

#royaume de france#mérovingiens#merovingian#merovingians#st clotilda#saints#catholicism#christianity#Clotilde de Burgondie#Reine des Francs#vive la reine#royaume des Burgondes#sainte clotilde#épouse de Clovis Ier#orthodox church#orthodox christianity#royalty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love how in the Empty Prayers AU banites just straight up pack things and leave.

I'd thought of giving Gortash a Big Confrontation with his cult and his god, but I've decided it's actually worse if he's just simply left behind. Left on Read. Given the Ultimate Silent Treatment.

He has failed Bane, so he isn't even worth the god's single thought now. Of course he will be punished upon death, but in life the worst punishment he can get is being treated like nothing. Like he isn't even here, like he never existed in the first place.

I'm sure I'd drive him mad to be completely ignored by the god he followed and the cult he lead. Lord Gortash who? Idk him

#lord enver gortash#enver gortash#empty prayers au#bg3#the only banite staying in bg is polandulus and its bc he has his personal reasons and is Straying off Lord Bane's path#bc of Clotilda obv#bane: so this Battle is lost. quickly pack your staff and move to amn. we were never here#some black hand: and what about lord Gortash?#bane: who?#banite: ...your chosen? lord enver gortash#bane: never heard of him. ANYWAY#banites: ....ok what did he do#some banite: idk but i bet it's about this murder hobo of Bhaal's former chosen. idc what was his name

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally tried sourdough (almost 2 months after my friend gave me some starter to use oops) and now I feel so powerful

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Survivors of the Clotilda: The Lost Stories of the Last Captives of the American Slave Trade

By Hannah Durkin.

Design by Mike McQuade.

1 note

·

View note

Text

George Spencer Watson - Clotilda of Derp (Mrs Sakharoff), 1912

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It's crazy to think they would have sailed right past here," Darron Patterson said, pulling his car onto a scrap of grass overlooking the murky Mobile River. As president of the Clotilda Descendants Association, Patterson is well versed in talking about the voyage of the Clotilda – the last known slave ship to reach America. His great-great-grandfather was Kupollee, later renamed Pollee Allen; one of the 110 men, women and children cruelly stolen from Benin in West Africa and brought to the US onboard the notorious ship.

The story of how Patterson's relative arrived in America aboard an illegal slaver started as a shockingly flippant bet. Fifty-two years after the US banned the importation of enslaved people, in 1860, a wealthy Alabama business owner named Timothy Meaher wagered that he could orchestrate for a haul of kidnapped Africans to sail under the noses of federal officers and evade capture.

With the assistance of Captain William Foster at the helm of an 80ft, two-mast schooner, and following a gruelling six-week transatlantic passage, he succeeded. The ship sneaked into Mobile Bay on 9 July under a veil of darkness. To conceal evidence of the crime, the distinctive-looking schooner – made from white oak frames and southern yellow pine planking – was set ablaze and scuttled to the depths of the swampy Mobile River, where it lay concealed beneath the water, its existence relegated to lore.

That is until almost 160 years later, when during a freakishly low tide, a local reporter named Ben Raines discovered a hefty chunk of shipwreck in the Mobile River, initially thought to belong to the Clotilda. It turned out to be a false alarm, but the discovery reignited interest and led to an extensive search involving multiple parties, including the Alabama Historical Commission, National Geographic Society, Search Inc and the Slave Wrecks Project. Following their exhaustive effort, in May 2019 it was finally announced that the elusive Clotilda had at long last been discovered.

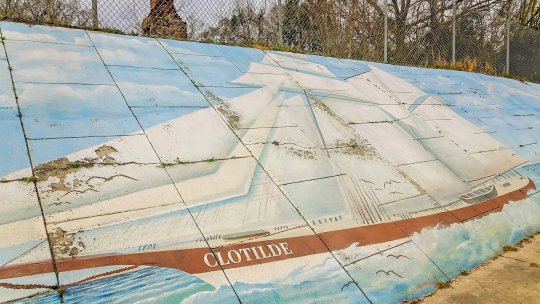

A mural of the Clotilda slave ship runs alongside the freeway separating the two sides of Africatown (Credit: Carmen K Sisson/Alamy)

Three years later, the city of Mobile found itself standing on the brink of a tourism boom, as interest in the story of the Clotilda, and the lives of its resilient captives, built.

Patterson had agreed to drive me around Africatown, an area where many of the ship's captives finally settled and where Patterson himself was raised. We began the tour at this scrap of land by the Mobile River, beneath a soaring interstate bridge where a group of Clotilda slave ship descendants meet annually for their Under the Bridge festival, to "talk about how our ancestors got here and to have some food and dance," Patterson said. There was no festival that day though and the atmosphere was muted; just one woman and her grandson played by the marshy water's edge below the steady hum of traffic.

Walking back to his car, Patterson, a former sportswriter now in his 60s, recalled that growing up, Africatown was a thriving, self-sufficient place, where "the only time we needed to leave the community was to pay a utility bill" as everything needed was close to hand, aside from a post office.

Located three miles north of downtown Mobile, Africatown was founded by 32 of the original Clotilda survivors following emancipation at the end of the Civil War, in 1865. Longing for the homeland they'd been brutally ripped from, the residents set up their own close-knit community to blend their African traditions with American folkways, raising cattle and farming the land. One of the first towns established and controlled by African Americans in the US, Africatown had its own churches, barbershops, stores (one of which was owned by Patterson's uncle); and the Mobile County Training School, a public school that became the backbone of the community.

However, this once-vibrant neighbourhood fell on hard times when a freeway was constructed in the heart of it in 1991, and industrial pollution meant that many of the remaining residents eventually packed up and left. "We couldn't even hang out our washing to dry because it would get covered in ash [a product of the oil storage tanks and factories on the outskirts of Africatown]," said Patterson. With the high-profile closure of the corrugated box factory, International Paper, in 2000, and an ensuing public health lawsuit brought about by residents, Africatown's community that had swelled to 12,000 people in the 1960s plummeted to around 2,000, where it stands today.

Cudjoe Kazoola Lewis, one of the Clotilda survivors and founders of Africatown, died in 1935 (Credit: Zoey Goto)

The exodus, poverty and environmental scars were visible as Patterson drove further into Africatown. The roadside was littered with abandoned factories. The quiet, residential streets were peppered with empty lots and vacant homes, some in such disrepair that their decaying walls had surrendered entirely to the creeping vines engulfing them.

But Africatown is changing, once again. With the discovery of the ship's remnants came the interest necessary to rebuild and preserve this historical place; an influx of attention and funds that is affecting everything from personal relationships to history to the fortune of the neighbourhood. Because, though the story of the Clotilda was known – and the lives of the original passengers were so well documented that photos, interviews and even film footage existed – without evidence of the vessel, the history was buried and it was not in the interest of the white population to acknowledge the truth of how they had arrived. Finding the vessel allowed their story to be affirmed and truth to be restored after decades of denial.

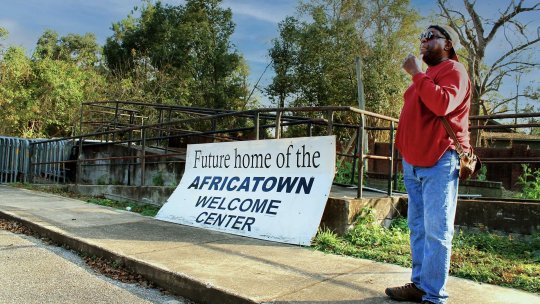

In the years since the Clotilda was discovered, the wreck has undergone extensive archaeological exploration to determine the likelihood of raising it safely. The ripple effect of media and public interest has meant a slew of government, community and private funding for Africatown's revitalisation, including The Africatown Redevelopment Corporation, which is using grants to restore homes in disrepair and demolishing and rebuilding derelict lots. Added to this is a $3.6 million payout from a BP oil spill settlement that has been earmarked for the long-awaited rebuilding of the Africatown Welcome Center, which was swept away in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina.

Patterson drove me to his grandmother's house and pulled over to chat with an elderly neighbour on her porch ("no photos, mind", she requested politely). Unlike some of the other descendent families, he told me, growing up he was told little of his ancestry. "I think my folks may have been embarrassed," he reflected, recalling that the smuggled captives had faced many humiliations, including being stripped naked for the voyage. "That must have just broke their will," Patterson said.

Africatown was one of the first towns established and controlled by African Americans in the US (Credit: Zoey Goto)

The 2019 announcement of the ship's discovery galvanised Patterson's curiosity, and he started to piece together his heritage, at which point his "whole life changed". He's since become hands-on in ensuring the story is told accurately, including an onscreen role in the film Descendant premiering at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival and as co-producer of the second installment of the forthcoming documentary The 110: The Last Enslaved Africans Brought to America about the Clotilda's passengers.

For Patterson, the discovery of the infamous ship brings fresh hope that Africatown is on the eve of a renaissance. Following years of denial, "the ship's very existence has finally been affirmed, so a burden has been lifted," said Mobile County Commissioner Merceria Ludgood. "That's every bit as important to the ethos of Africatown as the housing revitalisation currently happening."

Although there's a lack of restaurants and tourism facilities, that could be all set to change as well, said Ludgood, who is helping to set up the Africatown Heritage House, a permanent museum created in collaboration with the History Museum of Mobile to chart the history of Africatown. "Hopefully cottage industries will spring up, owned by people who live in the community," she said, noting that the discovery of the Clotilda has given Africatown's community a boost, resonating far beyond economics.

Next on Patterson's tour was the Africatown Heritage House, situated in the hub of the neighbourhood, overlooked by a row of modest, well-kept bungalows on a palm-lined avenue. Under construction at the time of my visit, the museum was due to open in early summer 2022 and will include a gallery of West African artefacts as well as salvaged sections of the Clotilda shipwreck, presented in preservation tanks.

“This is actually the best documented Middle Passage story we have as a nation”

It promises a unique insight, given the relatively recent timing of the Clotilda voyage in relation to the history of slavery. "This is actually the best documented Middle Passage story we have as a nation," explained Meg McCrummen Fowler, director of the History Museum of Mobile. "There's just an abundance of sources, mostly because it occurred so late. Several of the people on the ship lived well into the 20th Century, so instead of silence there's diaries, there's ship records."

Work has started on the Africatown Heritage House, a $1.3 million exhibit about the 110 enslaved West Africans and the Clotilda vessel (Credit: Zoey Goto)

Further regeneration projects on the horizon include a footbridge connecting the two areas of Africatown currently divided by the freeway. Water tours taking visitors close to the shipwreck site are scheduled to launch in spring 2022, and a few local residents ahead of the curve are offering walking tours of Africatown.

While tourists have yet to arrive in serious numbers, Africatown faces a familiar set of challenges to other US neighbourhoods experiencing rapid revitalisation, including ensuring the whole community supports change and that residents don't fall through the cracks. But Patterson said that the Africatown community is united in its mission.

"We're all on board with this," he said.

The final stop on our tour was the cemetery where many of the Clotilda's enslaved have been laid to rest. As we walked, Patterson told me that with the light currently shinning on this troubling chapter of history, he has hopes that there will be enough sustained interest to generate the funds needed to raise the schooner from the water.

Though the true impact of this fabled ship's discovery is yet to be seen, for Patterson, it presents an opportunity to lift up the Africatown community and honour the struggles of its founders. "This is about more than bricks and mortar, it's ultimately about the growth of our souls," he said, looking out over their crumbling gravestones, all facing east towards their motherland. "Finding the ship has finally validated our truth."

Unlike some of the other descendent families, Darron Patterson was told little of his ancestry (Credit: Zoey Goto)

#Africatown#clotilda#Cudjo#The Last Known Ship of the US Slave Trade#alabama#mobile#Black History Matters

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

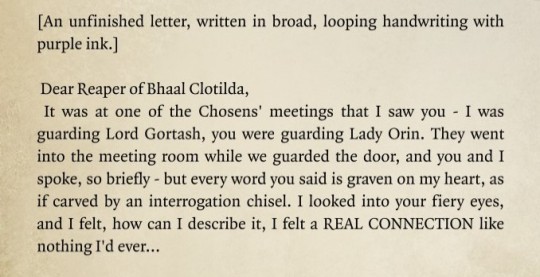

Now that I've finished my thorough playthrough I'm thinking about them:

Polandulus is the Banite who wrote this, and he's in the Steelwatch Foundry, and I'd assumed you could find Clotilda somewhere in-game... But there's no Clotilda? (I made a list of every Bhaalist and Banite I came across as I went, so I think I can state this pretty confidently.)

There's Reaper of Bhaal Clotilde, who leads the ambush in Bloomridge Park:

Is this a typo and the names are meant to match?

Are we to assume Polandulus is pining away, never brave enough to talk to his object of desire enough to even get their name right?

Was there a Clotilda, who's now dead? (questions! I have questions!)

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abake was captured from the Kingdom of Dahomey, in year 1859. Imprisoned on the last US slave ship Foster’s Clotilda. Importation of slaves in the US ended in 1808 espite slavery being legal until after the Civil War. Foster. Abake's mother and three sisters were separated at auction.

Then Abake died January 13, 1940 at age 85.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Clotilda von Derp (Frau Sakharoff) (1912)

George Spencer Watson (English, 1869 – 1934)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today We Honor Oluale Kossola, Renamed Cudjo Lewis

Zora Neale Hurston tells the story of Cudjo Lewis, who was born Oluale Kossola in what is now the West African country of Benin in her book “Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.”

A member of the Yoruba people, he was only 19 years old when members of the neighboring Dahomian tribe invaded his village, captured him along with others, and marched them to the coast.

There, he and about 120 others were sold into slavery, after the “Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves" took effect in 1808 slavery was abolished, and crammed onto the Clotilda, the “last” slave ship to reach the continental United States.

The Clotilda brought its captives to Alabama in 1860, just a year before the outbreak of the Civil War. Even though slavery was legal at that time in the U.S., the international slave trade was not, and hadn’t been for over 50 years. Along with many European nations, the U.S. had outlawed the practice in 1808.

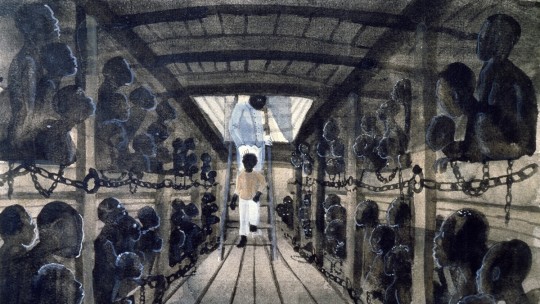

After being abducted from his home, Lewis was forced onto a ship with strangers. The abductees spent several months together during the treacherous passage to the United States, but were then separated in Alabama to go to different owners.

“We very sorry to be parted from one ’nother,” Lewis told Hurston. “We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now dey part us from one ’nother.”

“Derefore we cry. Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama.”

“We doan know why we be bring ’way from our country to work lak dis,” he told Hurston. “Everybody lookee at us strange. We want to talk wid de udder colored folkses but dey doan know whut we say.”

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered in April 1865, Lewis says that a group of Union soldiers stopped by a boat on which he and other enslaved people were working and told them they were free.

He and a group of 31 other freepeople saved up money to buy land near Mobile, which they called Africatown.

CARTER™️ Magazine

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#Instagram

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

On a cold December morning in 1931, a short, elderly Black woman set out on a 24km (15-mile) walk from her homestead in Alabama, United States, on a quest for justice. The long trek to the court in Selma was no small undertaking for a person in her mid-70s. But Matilda McCrear was determined to go and make her legal claim for compensation for the horrors that she and her family had been through.

Until her death 85 years ago on January 13, 1940, Matilda was the last surviving passenger on the last-ever slave ship bound from the West African coast to North America in late 1859...

Her story began many decades before and thousands of miles away from that sharecropping homestead. Originally named Abake – “born to be loved by all” – the girl later renamed Matilda by her American “owner” came into the world circa 1857, among the Tarkar people of the West African interior.

In 1859, at the age of two, little Abake was captured along with her mother (later renamed Grace), her three older sisters and some other relatives, by troops of the Kingdom of Dahomey, located in what is now Benin. Torn away from the rest of their family, they were victims of an age-old regional warfare which underpinned an equally ancient but persistent trade in slavery reaching across North and East Africa, the Ottoman Empire and eventually the Americas...

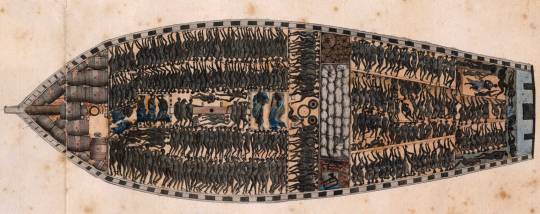

...Foster’s ship, Clotilda – a two-masted schooner, 26 metres (86 feet) in length – is now infamous as the last ship known to have carried slaves across the Atlantic to North America. By this time it was an illegal journey, for while slavery continued across the southeast of the US (and in parts of South America), the importation of slaves had been prohibited since 1808. The Clotilda set sail from Ouidah late in the year, purportedly carrying lumber – the 11-man crew being promised double their normal wage to keep quiet about the true contents, as per an entry in Foster’s journal.

Their route across the Atlantic was known as the “Middle Passage”, making up the second part of a triangular trade route connecting Europe, Africa and the Americas. Ships carried weapons and manufactured goods from Europe to the “slave coast” of West Africa on the first part of the round trip; in the Middle Passage, that cargo was traded for enslaved Africans who were transported to the US and South America, where they were usually sold by auction; and on the final course, the vessels returned to Europe usually laden with cotton, tobacco and sugarcane...

...Foster navigated the Clotilda, now carrying 108 slaves, into the port of Mobile, Alabama under cover of darkness in early 1860. He had it towed up the Mobile River to Twelvemile Island, where the captive Africans were transferred to a river steamboat. Foster wrote in his journal that the Clotilda was then burned to destroy any evidence...

...At Twelvemile Island, Abake, her mother and her 10-year-old sister were handed over by Foster to one of the financial backers of Clotilda, a wealthy plantation owner by the name of Memorable Creagh.

In another heartbreaking separation, Abake’s two other sisters (whose names are unknown) were sent elsewhere, never to be seen again – a typically brutal fate for so many of those regarded as a mere commodity...

...Matilda was still a small child when the Civil War broke out in the US in April 1861. Alabama, along with Virginia, North and South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Tennessee, seceded from the US and formed the Confederate States of America – on the grounds that the institution of slavery, the lifeblood of southern economies, was threatened by the federal government in Washington

President Abraham Lincoln made his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, declaring that all enslaved people in the Confederate states were free. This had no immediate effect on Matilda and her family, as the Civil War continued to rage. But when the Confederates were defeated on June 19, 1865, Matilda and her family were liberated...

...But after 1865, freed slaves did not find themselves in a friendly world. Many white Americans reacted with indignant fury to the idea of Black people being their equals. In a harsh and unwelcoming world, there were few options for uneducated ex-slaves other than to remain on the plantations as “sharecroppers” – a system whereby a tenant farmed a portion of land in exchange for a share of the crop. Sharecropping often involved contracts that trapped tenants in debt and poverty and which in practice was not far removed from actual slavery.

Upon her emancipation, Matilda and her family thus became supposedly free people. But, as Martin Luther King Jr pointed out in a 1968 sermon, “Emancipation for the Negro was only a proclamation. It was not a fact. The Negro still lives in chains: the chains of economic slavery, the chains of social segregation, the chains of political disenfranchisement.”

During the post-Civil War period of “Reconstruction”, many new federal laws promoting racial equality were quickly met by local state measures designed to keep Black people “in their place” and ensure that white people remained ascendant. This is seen in the reaction, at the state level, to the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the US Constitution.

The 13th Amendment of 1865 officially ended slavery in all US states and territories. Formerly enslaved people were legally freed, while the Freedmen’s Bureau was established to aid freed slaves through the provision of food, housing, medical aid, schooling and legal support.

To counter this, southern states, including Matilda’s home of Alabama, enacted the so-called “Black Codes”, curtailing the right of African Americans to own property, conduct business, buy and lease land or move freely in public spaces. The Black Codes forced many Black people into newly exploitative labour arrangements such as sharecropping.

A central element of the Black Codes was “vagrancy” laws. Through a system known as “convict leasing”, many African-American boys and men were arrested for minor offences such as vagrancy, imprisoned, and then leased out to work for private businesses. This created a new system of forced labour which again was little more than slavery. Convict leasing was legally rooted in the so-called “exception clause” of the 13th Amendment which states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.”

Convict leasing is prevalent in the US to this very day, with most working prisoners – still overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic – being paid only a few cents per hour. And even upon their release, ex-convicts have always faced immense hurdles to finding employment, getting credit, doing business or buying property due to their prison records...

...Matilda later entered a common-law partnership with a German-born man called Jacob Schuler and had a total of 14 children, 10 of whom survived into adulthood. What befell the other four is unknown. Whether she was prevented from marrying her partner by the ban on interracial marriage, or chose that arrangement, is also not known. In any case, Matilda appears not to have benefitted financially from the relationship, as she remained a sharecropper, living in the vicinity of Selma, Alabama, for most of her working life. At some point, she changed her surname from Creagh to McCrear, perhaps to distance herself from her enslaver and as an assertion of her own identity. Over the generations, the family surname has seen a number of further variations, including Crear, Creah, Creagher and McCreer...

...The Selma Times-Journal news story provides a vivid description of Matilda: “She walks with a vigorous stride. Her kinky hair is almost white and is plaited in small tufts and with bright-coloured string … Her voice is low and husky, but clear. Age shows most in her eyes … yet her … skin is firm and smooth.”

The article went on to relate that “Tildy has vigor and spirit in spite of her years … endurance and a natural aptitude for agriculture inherited from the Tarkar tribe, made [her] a thrifty farmer.”

Durkin writes that Matilda’s story is particularly remarkable “because she resisted what was expected of a Black woman in the US South in the years after emancipation. She did not get married. Instead, she had a decades-long common-law marriage … Even though she left West Africa when she was a toddler, she appears throughout her life to have worn her hair in a traditional Yoruba style, a style presumably taught to her by her mother.”...

...John Crear, a retired hospital administrator and community leader now in his late 80s, was born in the house Matilda resided in, and her funeral is one of his earliest memories. His grandmother’s strong character apparently passed into family lore. “I was told she was quite rambunctious”, he said.

He discovered more about Matilda when he and his wife carried out some research of their own into the family history. “I had no idea she’d been on the Clotilda”, he said. “It came as a real surprise. Her story gives me mixed emotions because if she hadn’t been brought here, I wouldn’t be here. But it’s hard to read about what she experienced.”

Matilda waited all her life for some form of justice and it would be another 14 years before the civil rights movement began to challenge the systemic racism she faced. Iconic leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X pointed out the hypocritical gap between the ideals of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments and the actual lived reality of African Americans.

In a 1964 speech, Malcolm X demanded: “… our right on this earth … to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society … which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.”

Although Matilda missed out on witnessing any of this, her grandson was active in the civil rights movement. “You can read about slavery and be detached from it,” he told National Geographic. “But when it’s your family that is involved, it becomes up close and very real.” During the Civil Rights movement, he was arrested and imprisoned on charges of assault and battery – for the offence of stopping a white man who attempted to stuff a live snake down his throat.

Indeed, many civil rights campaigners faced extreme violence from the police and the National Guard, leaving many injured, imprisoned or even dead, as in the case of both Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X.

But their sacrifices were not in vain. By the mid-1960s, the entire plethora of Jim Crow statutes had been taken down. Segregation in public schools was deemed unconstitutional in the 1954 case of Brown v Board of Education; discriminatory electoral practices such as literacy tests and grandfather clauses were banned by the Voting Rights Act of 1965; and all other forms of segregation and employment discrimination were outlawed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

These were statutory measures aiming to eradicate prejudice in the official sphere. However positive their effect, deeper-rooted racism at the societal level remains a feature of US life.

...

This is just excerpts from the article. I want everyone to read it in whole. The last surviving (official) chattel slave in the United States only died in nineteen forty. My grandmother--who's still alive--was a teenager at the time. This isn't ancient history, this is all too fresh and lingering.

#Matilda McCrear#Abake#slavery#chattel slavery#American history#American south#sharecroppers#prison labor#penal slavery#Civil Rights#today in history#i cried my eyes out reading this

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

the Toye family pt 2 1/2: the John edition.

So John Toye was also a pretty busy man in the early zeroes. Unlike his brother, he took his job as principal pretty seriously and by the time it was 1903 he was in the Mansfield Alumni Association.

and here he is a year later

In 1905, things get a bit exciting for John. why? Because he's getting married!

to one Mary McCanna. John is good friends with Frances McCanna. Mary's brother.

Now, Peter is noticeably absent from the wedding, as he is for any other family gatherings. but there is a Malarkey present!😉 (my personal theory is that the brothers had a falling out after Peter got fired, because Mary and John seem pretty close. they do a lot of things together. Like going on holiday)

A month after the wedding, Frances McCanna and John Toye chase a chipmunk and stumble across 200 pounds worth of stolen goods.

nothing much else happens in 1905 except another Mansfield Alumni meeting. (without Peter Toye once more)

In 1906, Mary falls ill, but recovers. (My guess, Mary has always been a bit frail. because in 1915, she passes away after an short illness)

a year later she gives birth to their first child. a daughter, her name is Clotilda Mary Toye. (they later also have a second child, a boy named John Toye)

here's one of Mary's death announcements.

now let's go back to peter, shall we?

5 notes

·

View notes