#charles brabant

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

~ 🤍 Royal Parallels 🤍 ~

5/6 Young Royal Heirs of Sweden, Norway, Denmark, The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg celebrate Princess Ingrid Alexandra’s 18th Birthday Gala and Prince Christian’s 18th Birthday Gala, 2022 vs 2023 ✨

#awww 😍🥹#They are all grown up 😭❤️🩹#prince christian#danish royal family#princess estelle#swedish royal family#princess ingrid alexandra#norwegian royal family#princess catharina amalia#dutch royal family#princess Elisabeth#duchess of brabant#belgian royal family#prince charles#luxembourg grand ducal family#Royal parallels#parallels#my parallels

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

ROYAL NEWS!!!

King Philippe, Queen Mathilde and Princess Elisabeth, The Duchess of Brabant will be attending the celebrations for King Charles’s Coronation next month.

Princess Elisabeth, The Duchess of Brabant will just attend the Reception on May 5th.

While King Philippe and Queen Mathilde will attend the coronation ceremony on May 6th.

#royaltyedit#theroyalsandi#king philippe#queen mathilde#crown princess elisabeth#princess elisabeth#duchess of brabant#belgian royal family#royal news#charles coronation#coronation 2023#my edit

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Léopold Philippe Charles Albert Meinrad Hubert Marie Michel of Belgium, Duke of Brabant, later King Leopold III

Belgian vintage postcard

#hubert#philippe#leopold#sepia#king#marie#photography#léopold philippe#charles#vintage#charles albert meinrad hubert marie michel#michel#brabant#postkaart#meinrad#leopold iii belgian#later#prince#ansichtskarte#ephemera#carte postale#postcard#postal#briefkaart#belgian#duke#photo#belgium#lopold#tarjeta

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇬🇧 King Charles III and The Princess of Wales

🇧🇪 King Philippe and Princess Elisabeth, The Duchess of Brabant

🇳🇱 Princess Catharine-Amalia, Princess of Orange

Friday, May 5, 2023

#british royal family#dutch royal family#belgian royal family#king charles iii#king philippe#princess elisabeth#duchess of brabant#princess catharina amalia#princess of orange#kciii coronation#carlitosbigday

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

#heiliges römisches reich#karl v.#carlos I de españa#haus habsburg#erzherzog#könig von spanien#kingdom of belgium#count of flanders#duke of brabant#holy roman emperor#holy roman empire#charles v#charles I#king of spain#monarquía española#casa de austria#house of habsburg#full length portrait#in armour#full-length portrait#chocolate card#kaiser#der deutschen kaiser#kaisersaal

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

New : On May 5th 2023, King Philippe of Belgium and Crown Princess Elisabeth of Belgium, Duchess of Brabant will attend the reception ahead of King Charles III and Queen Camilla's Coronation Ceremony, at Buckingham Palace in London, England -April 17th 2023.

#king philippe#crown princess elisabeth#duchess of brabant#belgian royal family#belgium#2023#april 2023#king charles iii and queen camilla's coronation#king charles iii's coronation#coronation#royal children#my edit

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles V by Albrecht de Vriendt.

#kingdom of belgium#duchy of brabant#haus habsburg#full length portrait#county of flanders#charles v#holy roman emperor#heiliges römisches reich#holy roman empire#austria#maison de habsbourg#albrecht de vriendt

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three generations portraits of former, current and future European monarchs:

♔ Belgium: former King Albert II, King Philippe and Princess Elisabeth, the Duchess of Brabant

♔ Denmark: Queen Margrethe II, Crown Prince Frederik and Prince Christian

♔ Luxembourg: Grand Duke Henri, Hereditary Grand Duke Guillaume and Prince Charles

♔ The Netherlands: former Queen Beatrix, King Willem-Alexander and Princess Catharina-Amalia, the Princess of Orange

♔ Norway: King Harald V, Crown Prince Haakon and Princess Ingrid-Alexandra

♔ Spain: former King Juan Carlos II, King Felipe XI and Leonor, the Princess of Asturias

♔ Sweden: King Carl XI Gustaf, Crown Princess Victoria and Princess Estelle

♔ England: King Charles III, William, the Prince of Wales and Prince George of Wales

#this has been sitting in my drafts for AGES#figure it was time to post#belrf#king albert#king philippe#princess elisabeth#drf#queen margrethe#crown prince frederik#prince christian#lgdf#grand duke henri#hereditary grand duke guillaume#prince charles#durf#princess beatrix#king willem alexander#princess catharina amalia#nrf#king harald#crown prince haakon#princess ingrid alexandra#srf#king juan carlos#king felipe#princess leonor#swrf#king carl gustaf#crown princess victoria#princess estelle

420 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille Desmoulins and Antoine-François Momoro

Antoine-François Momoro Camille Desmoulins

I couldn't say exactly how, but I have the impression that the printer-bookseller Antoine-François Momoro and the pamphleteer Camille Desmoulins had very opposite paths and were very different despite having similarities, if you know what I mean. Camille Desmoulins was a republican from the start, while Momoro was cautious on the matter and hesitated to publish Desmoulins' pamphlet "La France Libre" in June 1789, only releasing it on July 17, 1789. However, Momoro increasingly engaged in the revolution, eventually becoming one of its key figures and a regular at the Cordeliers Club. He was arrested after the Flight to Varennes, having signed the Champ de Mars petition. Desmoulins, on the other hand, had to go into exile. In this regard, they shared the common ground of being among the harshest critics of the monarchy, although Desmoulins had been vocal much earlier, opposing the property-based suffrage in 1789 and circulating 3,000 copies of his journal "Les Révolutions de France et de Brabant." During the Varennes episode, Momoro ensured that many issues of the Cordeliers Club Journal, which became virulent towards the king due to his escape, were distributed.

Both Camille Desmoulins and Momoro participated in the events of August 10, 1792. While Desmoulins left his mark as a key figure of July 14, 1789, Momoro, alongside Mayor Pache, inscribed the words "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" on public buildings in the summer of 1793. Both played roles in the expulsion of the Girondins. Desmoulins was elected to the Convention, whereas Momoro, though not elected, played a significant role in the Paris Commune, overseeing supplies and soldier morale, among other tasks. He recruited volunteers from various departments and regions and was sent to Vendée alongside Charles Philippe Ronsin. Both men remained actively involved in what was considered a faction until the end, in contrast to their leaders Danton and Hébert, who were less ardent or coherent (although there were no real leaders, if you understand my point).

Their wives played more significant political roles alongside their companions than often portrayed in films. Lucile Desmoulins' journal shows her as a fervent critic of the monarchy, writing dark texts about Marie-Antoinette, approving the King's execution, and defending Camille when the future Marshal Brune asked him to temper his critiques in "Le Vieux Cordelier." Sophie Fournier, Momoro's wife, played a crucial role in her husband's dechristianization campaign, representing the Goddess of Reason armed with a pike at each ceremony (when you consider the struggle of the women of the Revolution to bear arms, in my opinion, it only demonstrates her great determination ). Both Momoro and Desmoulins had only one son from their marriages, and their wives were subject to sexist attacks, similar to Manon Roland, Louise Gély, Marie Françoise Goupil, and even Marie-Antoinette.

However, their paths diverged significantly. Initially cautious, Momoro became increasingly revolutionary, ultimately considered an ultra-revolutionary, while Desmoulins became more moderate. Momoro began to advocate for property rights redistribution, a stance not shared by Desmoulins or many Montagnards, who were moderate on this issue. Momoro supported de-Christianization, while Desmoulins opposed it. Momoro called for harsher measures against counter-revolutionary suspects, whereas Desmoulins, in "Le Vieux Cordelier," called for leniency (except for approve the mock trial of the Hébertists) and advocated for the mass release of counter-revolutionary suspects, many of whom were innocent. During the harsh winter of 1793-1794, Momoro prioritized the suffering of the Parisian masses, a concern Desmoulins did not share.

Despite this, Momoro and many considered Hébertists were sent to the guillotine. It is said that Momoro died bravely, like most of his colleagues except Hébert (his bravery was remarkable given that his wife Sophie was arrested ten days after him, and he knew she could die, yet he refused to show fear in public). Desmoulins, calm when preparing for death, panicked when Lucile was arrested (as unjustly as the arrests of the Hébert and Momoro wives) and expressed his despair all the way to the scaffold. The most horrifying part is that Desmoulins and Momoro learned of their wives' arrests the day before their execution.

My personal reflections: Honestly, I believe there is a golden legend about Camille Desmoulins, which he does not deserve, and a black legend about Momoro's faction, which is also undeserved . As I mentioned in this post https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/744960791081631744/the-difference-in-treatment-between-the-indulgents?source=share, in my eyes, Camille Desmoulins is highly overrated. While I do not deny his talents, I do not think he was fit for great responsibilities, unlike men he mocked, like Ronsin, Saint-Just, or Momoro, who worked tirelessly during the revolution's most challenging period. I must say in my eyes that once Desmoulins became a Convention deputy, he seemed to rest more than other revolutionaries. Consider Sonthonax, labeled a Girondin, who accepted a mission to Saint Domingue to better fight against colonizers who denied equal rights between people of color and whites, or Condorcet, who worked with Carnot on women's education with Pastoret and Guilloud, or Charles Philippe Ronsin. Many members of the Committee of Public Safety had grueling schedules in addition to their missions. Other Convention deputies, unlike Desmoulins, were sent on missions, such as Charles Gilbert Romme (and many others). While Desmoulins advocated leniency in "Le Vieux Cordelier," he approves the mock trial that led to the Hébertists' guillotining and said nothing about their wives' arrests (perhaps he planned to call for their release to be fair, but I don't know). Besides being partly responsible for the fall of the Brissotins, he remained silent on the illegal harassment Jacques Roux faced, leading to his suicide, and once said he understood the need to curb liberty for the people's salvation. Nonetheless, Camille Desmoulins should never have been arrested, let alone executed, as he only wrote articles.

In comparison, Momoro, a victim of a black legend, was clearly more honest about following a consistent line. Initially more cautious than Desmoulins in 1789, he ultimately advocated for more social rights. Despite not being elected to the Convention, he played a significant role in the Paris Commune, carrying out various missions during the revolution's most challenging period, from late 1792 to early 1794. During the Convention's invasions, he was among those who demanded vital laws for the revolution, such as the maximum or the revolutionary army's levy. His attempted insurrection was mainly due to the severe suffering of the Parisian masses in the winter of 1793-1794 and the frequent attacks on the Hébertists by the Convention (the arrests of Ronsin and Vincent in 1793), while dubious characters like Danton were free. Momoro was never rehabilitated, unlike Desmoulins, who was falsely accused of sabotaging supplies and destroying his reputation by accumulating 190,000 livres in cash, although he always refused to elevate himself, leaving behind only 26 livres and 400 livres in assignats. As Mathiez Albert, a historian harsh on Robespierre's opponents, said, "One of the main leaders of this Hébertist party, who first tried to translate and represent the popular aspirations against the wealthy bourgeois of the Convention [...] He died poor, as he had lived."

However, Momoro also had his faults, and Desmoulins was right on some points. Nothing is entirely black or white, especially among revolutionaries. The dechristianization campaigns often caused problems for the French Revolution. I understand the anger of incorruptible revolutionaries like Momoro, given the religious intolerance of that time, but intolerance cannot be fought with more intolerance. These campaigns also alienated many French people.

Moreover, if Desmoulins had dubious political allies in Danton, Momoro could be worst. He counted as an ally the horrible Nantes drowner, Carrier (Momoro didn't drown people by the way, but still a bad point for him...). Many French Revolution characters made alliances with dubious figures (like Robespierre, who knew the criticisms against Danton were well-founded but largely allied with him until a certain point), but it's still a big no for me for the alliance with Carrier. Not with one of the most hateful characters of the French Revolution. His last insurrection attempt, which led to his guillotining, was understandable, but the Convention was at a critical point and could not afford a new insurrection. Unlike Hanriot and Chaumette, he was not lucid enough on this point. He should have been more lenient with the suspect laws. Plus let's not forget that the faction call hebertist who after denunce the faction call enragés took them petition.

Even if I am harsh on Camille Desmoulins, I must acknowledge his great courage and contributions to the French Revolution, and like Momoro, he never betrayed his principles. Moreover, I fully agree with him on press freedom and often highlight his reasoning on freedom of expression. It's worth noting that Camille Desmoulins' father died shortly after his son's execution, heartbroken by his loss, just as Momoro's mother, a servant in Besançon, died a week or two after her son's death. Regardless of what one might say, both revolutionaries earned the right to be considered important figures in the 1789-1794 period.

I would like to end with two phrases these two revolutionaries reportedly said shortly before their deaths:

Momoro, during his condemnation: "I am accused, I who gave everything for the Revolution!"

Camille Desmoulins in jail : "I had dreamed of a republic that everyone would have adored."

P.S.: I have searched everywhere for a biography of Sophie Fournier, Momoro's wife. I found it in PDF and French, but I don't know its value.

Here is the link : https://www.sh6e.com/images/publications/Lettre_d_information/2023_05_Lettre_info_Sh6.pdf

#frev#french revolution#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#momoro#sophie momoro née Fournier#cordeliers#hébertistes#indulgents

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

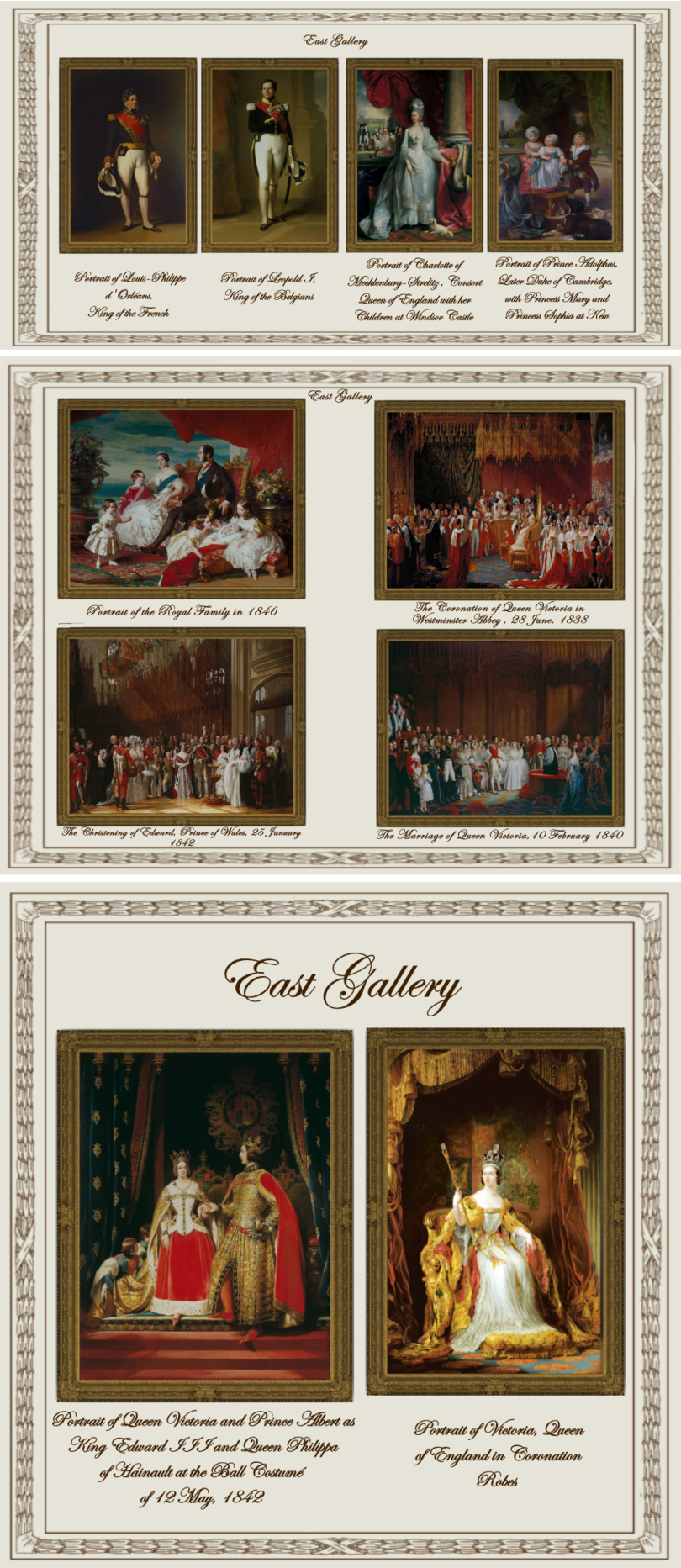

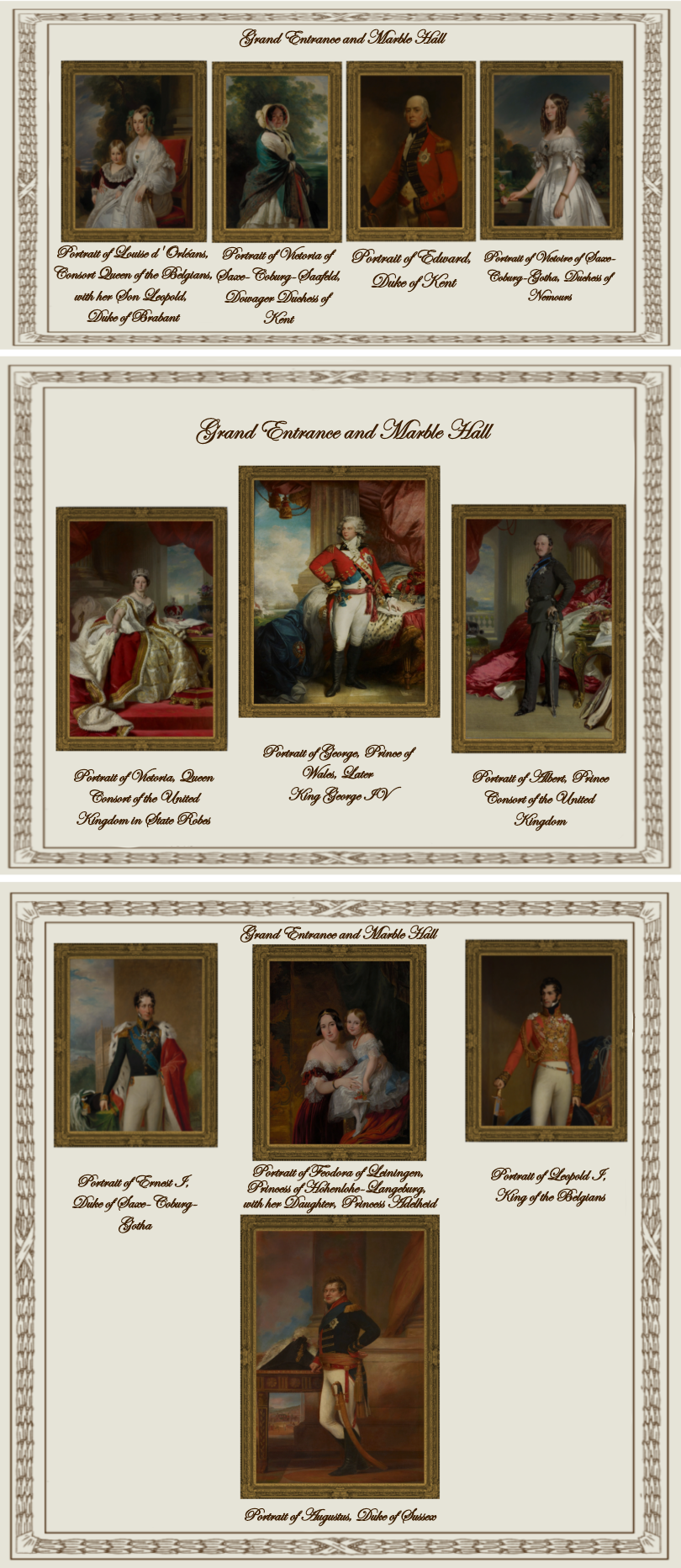

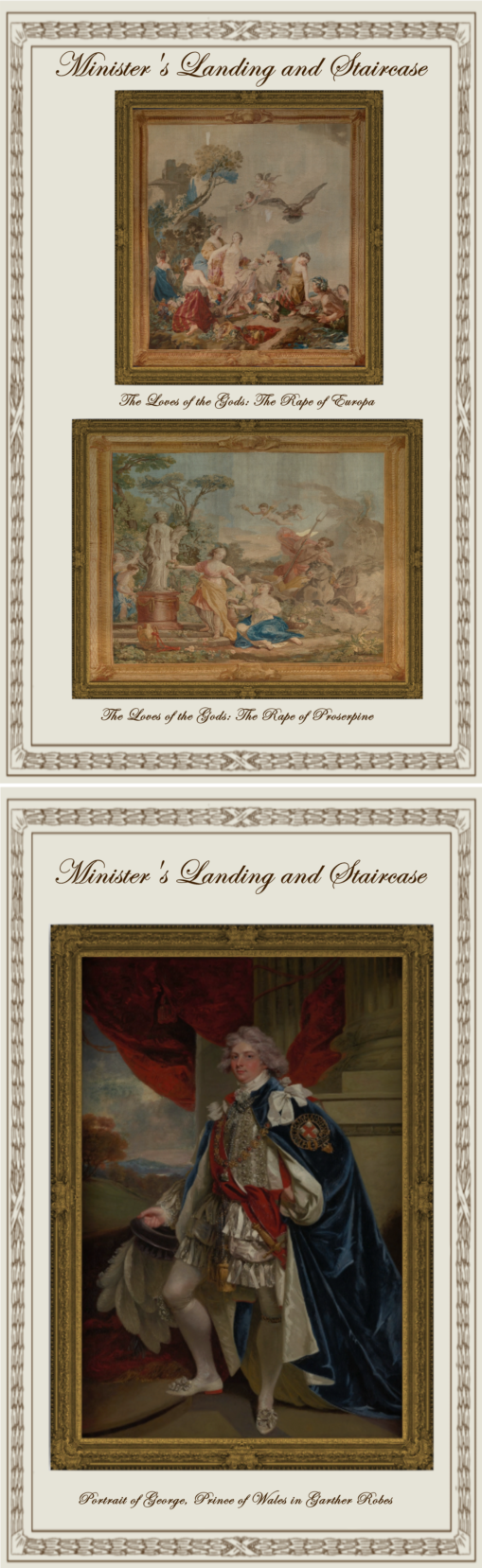

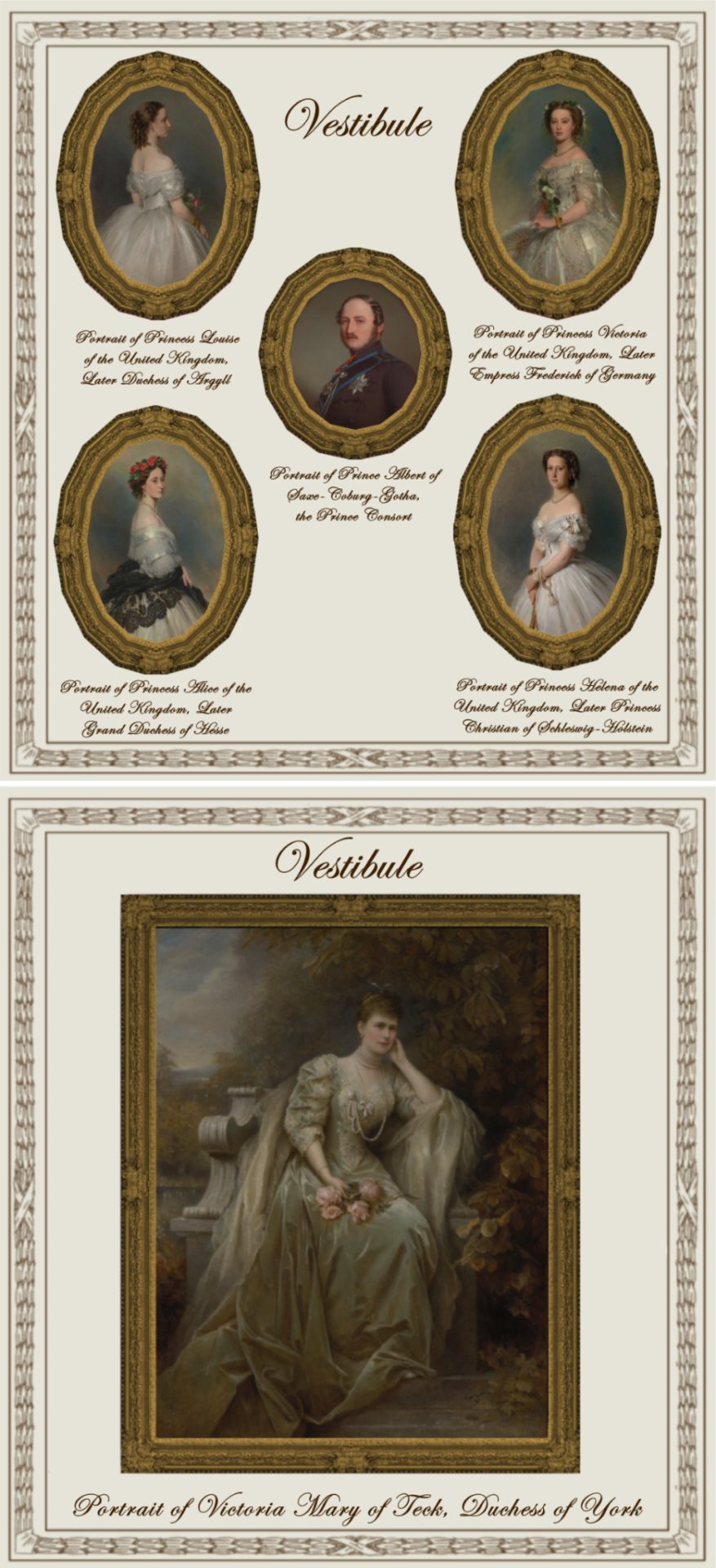

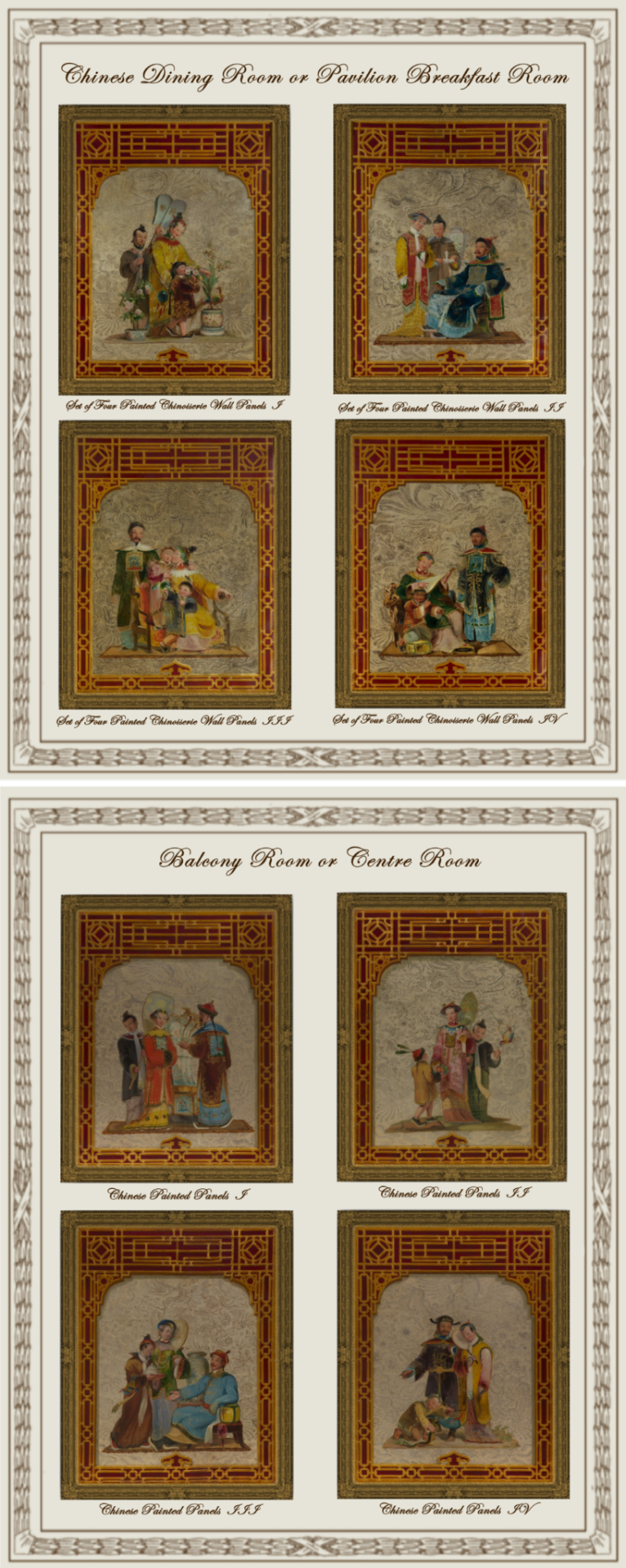

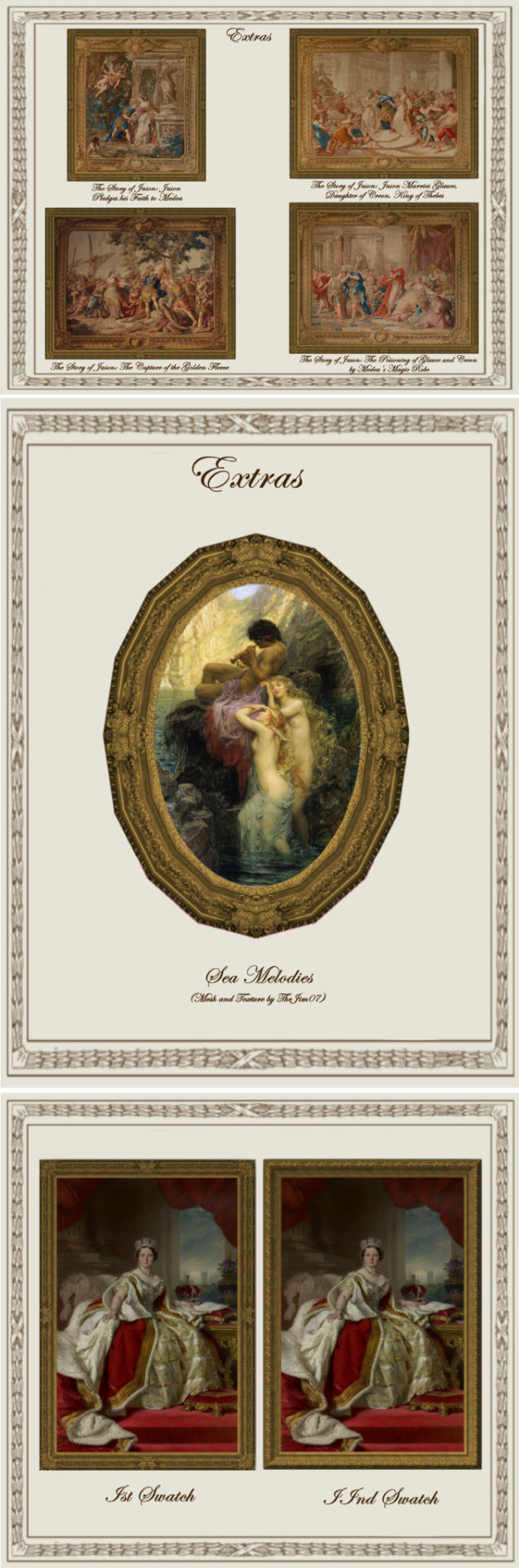

Paintings from Buckingham Palace: part II

A retexture by La Comtesse Zouboff — Original Mesh by @thejim07

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the Royal Collection Trust. The British monarch owns some of the collection in right of the Crown and some as a private individual. It is made up of over one million objects, including 7,000 paintings, over 150,000 works on paper, this including 30,000 watercolours and drawings, and about 450,000 photographs, as well as around 700,000 works of art, including tapestries, furniture, ceramics, textiles, carriages, weapons, armour, jewellery, clocks, musical instruments, tableware, plants, manuscripts, books, and sculptures.

Some of the buildings which house the collection, such as Hampton Court Palace, are open to the public and not lived in by the Royal Family, whilst others, such as Windsor Castle, Kensington Palace and the most remarkable of them, Buckingham Palace are both residences and open to the public.

About 3,000 objects are on loan to museums throughout the world, and many others are lent on a temporary basis to exhibitions.

-------------------------------------------------------

The second part includes paintings displayed in the Ball Supper Room, the Ballroom, the Ballroom Annexe, the Bow Room, the East Gallery, the Grand Entrance and Marble Hall, the Minister's Landing & Staircase, the Vestibule, the Chinese Dining Room and the Balcony Room.

This set contains 57 paintings and tapestries with the original frame swatches, fully recolourable. They are:

Ball Supper Room (BSR):

Portrait of King George III of the United Kingdom (Benjamin West)

Ballroom (BR):

The Story of Jason: The Battle of the Soldiers born of The Serpent's Teeth (the Gobelins)

The Story of Jason: Medea Departs for Athens after Setting Fire to Corinth (the Gobelins)

Ballroom Annexe (BAX):

The Apotheosis of Prince Octavius (Benjamin West)

Bow Room (BWR):

Portrait of Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge (William Corden the Younger)

Portrait of Princess Augusta of Cambridge, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Alexander Melville)

Portrait or George, Duke of Cambridge (William Corden the Younger)

Portrait of Frederick William, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Augusta of Saxe-Weimar, Princess of Prussia, later Queen of Prussia and German Empress (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Prince Leopold, Later Duke of Albany (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Ernest, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langeburg (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Ferdinand of Savoy, Duke of Genoa (Eliseo Sala)

Portrait of Marie Alexandrina of Saxe-Altenburg, Queen Consort of Hanover (Carl Ferdinand Sohn)

Portrait of Leopold, Duke of Brabant, Later Leopold II, King of the Belgians (Nicaise de Keyser)

Portrait of Marie Henriette, Archduchess of Austria and Duchess of Brabant, Later Queen of the Belgians (Nicaise de Keyser)

East Gallery (EG):

Portrait of Leopold I, King of the Belgians (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Victoria, Queen of England in Coronation Robes (Sir George Hayter)

Portrait of Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, King of the French (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Consort Queen of England with her Children at Windsor Castle (Benjamin West)

Portrait of Prince Adolphus, later Duke of Cambridge, With Princess Mary and Princess Sophia at Kew (Benjamin West)

The Coronation of Queen Victoria in Westminster Abbey, 28 June, 1838. (Sir George Hayter)

The Christening of Edward, Prince of Wales 25 January, 1842 (Sir George Hayter)

The Marriage of Queen Victoria, 10 February, 1840 (Sir George Hayter)

Portrait of the Royal Family in 1846 (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as King Edward III and Queen Philippa of Hainault at the Ball Costumé of 12 May, 1842 (Sir Edwin Landseer)

Grand Entrance and Marble Hall (GEMH):

Portrait of Edward, Duke of Kent (John Hoppner)

Portrait of Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (George Dawe)

Portrait of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafeld, Dowager Duchess of Kent (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Albert, Prince Consort of the United Kingdom (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Victoria, Queen Consort of the United Kingdom in State Robes (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Louise d'Orléans, Consort Queen of the Belgians, with her Son Leopold, Duke of Brabant (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Feodora of Leiningen, Princess of Hohenlohe-Langeburg, with her Daughter, Princess Adelheid (Sir George Hayter)

Portrait of George, Prince of Wales, Later King George IV (Mather Byles Brown)

Portrait of Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Duchess of Nemours (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Augustus, Duke of Sussex (Domenico Pellegrini)

Portrait of Leopold I, King of the Belgians (William Corden the Younger)

Minister's Landing and Staircase (MLS):

Portrait of George, Prince of Wales in Garther Robes (John Hoppner)

The Loves of the Gods: The Rape of Europa (the Gobelins)

The Loves of the Gods: The Rape of Proserpine (The Gobelins)

Vestibule (VL):

Portrait of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, the Prince Consort (Unknown Artist from the German School)

Portrait of Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, Later Grand Duchess of Hesse (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Princess Helena of the United Kingdom, Later Princess Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Princess Louise of the United Kingdom, Later Duchess of Argyll (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Princess Victoria of the United Kingdom, Later Empress Frederick of Germany (Franz Xaver Winterhalter)

Portrait of Victoria Mary of Teck, Duchess of York (Edward Hughes)

Chinese Dining Room or Pavilion Breakfast Room(CDR):

Set of Four Painted Chinoiserie Wall panels I (Robert Jones)

Set of Four Painted Chinoiserie Wall panels II (Robert Jones)

Set of Four Painted Chinoiserie Wall panels III (Robert Jones)

Set of Four Painted Chinoiserie Wall panels IV (Robert Jones)

Balcony Room or Centre Room (BR):

Chinoiserie Painted Panel I (Robert Jones)

Chinoiserie Painted Panel II (Robert Jones)

Chinoiserie Painted Panel III (Robert Jones)

Chinoiserie Painted Panel IV (Robert Jones)

EXTRAS! (E):

I decided to add the rest of the tapestries from the story of Jason (wich hangs in the Grand Reception Room at Windsor Castle) and (with Jim's permission) added the original mesh for paintings number 2,3,4 & 5 from the Vestibule (seen here and here) wich was never published. These items are:

The Story of Jason: Jason Pledges his Faith to Medea (the Gobelins)

The Story of Jason: Jason Marries Glauce, Daughter of Creon, King of Thebes (the Gobelins)

The Story of Jason: The Capture of the Golden Fleece (the Gobelins)

The Story of Jason: The Poisoning of Glauce and Creon by Medea's Magic Robe (the Gobelins)

Sea Melodies (Herbert James Draper) (made by TheJim07)

-------------------------------------------------------

Found under decor > paintings for:

500§ (BWR: 1,2,3,4,5,6, & 8 |VL: 1)

570§ (VL: 2,3,4 & 5 |E: 5)

1850§ (GEMH: 1 & 3)

2090§ (GEMH: 2,6,7, 9 & 11)

3560§ (GEMH: 4,5 & 10 |BSR: 1 |EG: 1,2,3,4 & 5 |MLS: 1 |BAX: 1)

3900§ (CDR: 1,2,3 & 4 |BR: 1,2,3 & 4 |EG: 10 |VL: 6 |GEMH: 8)

4470§ (MLS: 2 |E: 1)

6520§ (BR 1 & 2| MLS: 3 |EG: 6,7,8 & 9 |BR: 1 & 2 |E: 2,3 & 4)

Retextured from:

"Saint Mary Magdalene" (BWR: 1,2,3,4,5,6, & 8 |VL: 1) found here.

"Sea Melodies" (VL: 2,3,4 & 5 |E: 5)

"The virgin of the Rosary" (GEMH: 1 & 3) found here.

"Length Portrait of Mrs.D" (GEMH: 4,5 & 10 |BSR: 1 |EG: 1,2,3,4 & 5 |MLS: 1 |BAX: 1) found here

"Portrait of Maria Theresa of Austria and her Son, le Grand Dauphin" (CDR: 1,2,3 & 4 |BR: 1,2,3 & 4 |EG: 10 |VL: 6 |GEMH: 8) found here

"Sacrifice to Jupiter" (MLS: 2 |E: 1) found here

"Vulcan's Forge" (BR 1 & 2| MLS: 3 |EG: 6,7,8 & 9 |BR: 1 & 2 |E: 2,3 & 4) found here

(you can just search for "Buckingham Palace" using the catalog search mod to find the entire set much easier!)

Disclaimer!

Some paintings in the previews look blurry but in the game they're very high definition, it's just because I had to add multiple preview pictures in one picture to be able to upload them all! Also sizes shown in previews are not accurate to the objects' actual sizes in most cases.

Drive

(Sims3pack | Package)

(Useful tags below)

@joojconverts @ts3history @ts3historicalccfinds @deniisu-sims @katsujiiccfinds @gifappels-stuff

-------------------------------------------------------

#the sims 3#ts3#sims 3#s3cc#sims 3 cc#sims 3 download#sims 3 decor#edwardian#victorian#regency#georgian#buckingham#buckingham palace#wall decor#sims 3 free cc#large pack#this was exhausting

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi there!! i was wondering you knew anything about the relationship between robespierre and marat? ive been seeing some information that robespierre wasnt fond (or at least less fond??) of marat than marat was of robespierre, but havent found any other information about it unfortunately. thanks :)!

In total, Marat mentions Robespierre around 90 times in his journals from his debut in September 1789 up until his death in July four years later. The first time he does so (which also happens to be the first connection I’ve been able to find between the two) is already in the second number of l’Ami du Peuple(released September 13 1789) where he writes about a certain ”Robertpierre.” Then one day later, in number 4, he instead mentions a ”Robers-Pierre.” In both these instances, Marat does however appear to just give the exact same summary as three other journals, and there’s value put into it whatsoever.

It would appear Marat never got a hold on how to spell Robespierre’s name properly, as he throughout the rest of his career as a journalist inconsistently shifts between calling him ”Robespierre,” ”Roberspierre” and, in some rare instances, ”Robertspierre.” The next time he mentions him is in number 81 (December 29 1789). The following three times Robespierre is brought up in l’Ami du Peuple are the very first instances of Marat showing his own thoughts on him instead of just giving a neutral summary of things he’s said at the National Assembly:

M. de Robespierre and especially Mr. Charles de Lameth energetically fought against the inconsiderate proposal to give praise to officers, whose conduct has harmed the liberty and security of citizens. l’Ami du Peuple, number 101 (January 18 1790)

M. de Robespierre supports the motion of Mr. de la Salcette, with more or less solid arguments. l’Ami du Peuple, number 104 (January 21 1790)

…to remove from the fatherland its most zealous defenders, [the Municipal Research Committee] pushed its audacity to the point of directing its pursuits against Barnavre, Péthion [sic] de Villeneuve, the Lameths, d'Aiguillon, Roberspierre [sic]..., cherished names of the free France, to which it had added those of La Fayette and Mirabeau. l’Ami du Peuple, number 108 (May 20 1790)

This praising of Robespierre is something Marat would consistently keep up throughout the rest of his journalistic career. Only throughout the rest of 1790, we find him calling him ”the wise Robespierre” (number 156 (July 7), ”the loyal Robespierre” (number 210 (September 3), an orator with ”great principles” and ”excellent views […] [that] we have no doubt he will develop in a way that will cause a sensation.” (number 265 (October 29) and ”[a man] who’s heart always appears to be animated with the purest of civism” (number 320 (December 24), listing him among deputies he considers ”patriotic” (number 156 (July 7), number 188 (August 11), number 210 (September 3), number 277 (November 11), number 288 (November 22), number 292 (November 28) and at one point even playing him on a higher level than so, calling him ”the only deputy who is educated in great principles, and perhaps the only true patriot who sits in the Assembly” (number 263, October 27).

February 2 1791 is the first instance where Robespierre in his turn is recorded to have mentioned Marat’s name. He does so defending the journalist at the Jacobins after an arrest warrant has been issued against him for an article recently published in his paper. Desmoulins’ Révolutions de France et de Brabant, the journal giving the most detailed description of the defence, summarizes it in the following way:

At the same session at the Jacobins, Robespierre, the only member of the National Assembly to whom the severe Marat would not have given the black ball, also took up his defense. He made us aware of the absurdity of the crime that the president of research attributed to the Friend of the People, of getting along with the English. Marat had never ceased to deplore the trade treaty of 1786 with the English, and to vociferate against Pitt, and against the intelligence of the cabinet of S. James, with the Austrian committee of the Tuileries. In favor of Marat was also this thing which militates so strongly for all patriotic writers: if the Friend of the People is extreme and angry, at least it is in the direction of the revolution. On what front did the research committee sign this order against him, under the ridiculous pretext of intelligence with the English, while it at the same time leaves Durosoi, as extreme, as bloodthirsty as Marat, in peace, and so many other friends of the king, the nobility and the clergy, who did not even hide their understanding with the Austrians, with all our enemies, and every day invite them with loud cries to come and slaughter the patriots. There is no reply to this reasoning; so Voidel, who saw his condemnation in everyone's eyes, recognized his sin, and promised to withdraw the order and remove the sentence.

In a speech regarding liberty on the press held on May 11 1791, Robespierre also says that ”if it is true that the courage of writers devoted to the cause of justice and humanity is the terror of the intrigue and ambition of men in authority; the laws against the press must become in the hands of the latter a terrible weapon against liberty,” which according to the by publisher inserted footnote is an allusion to the situation of the journalists Desmoulins and, especially, Marat.

Marat in his turn continued his praising of Robespierre throughout the same year. Besides grouping him together with other men considered patriotic (number 342 (January 16), number 371 (February 14), number 382 (February 25), number 392 (March 7), number 455 (May 11), number 519 (July 15), number 526 (August 1), number 562 (September 30) and calling him things such as ”the loyal Robespierre ”(number 367 (February 8), number 478, number 443 (April 29), number 458 (May 14), (June 3), number 488 (June 13), number 520 (July 16), number 521 (July 17) ”the just Robespierre” (number 409 (March 24) and ”the virtuous Robespierre” number 438 (April 21) he also goes further in placing Robespierre on a higher level than his fellow representatives, frequently going so far as to call him ”the only pure member of the Assembly” (number 414 (March 29), number 462 (May 18), number 472 (28 maj), number 475, May 31, number 504 (June 28), number 510 (July 4), number 511 (July 5). He also starts to frequently refer to Robespierre as ”the Incorruptible”number 458 (May 14), (number 462 (May 18), number 504 (June 28), number 514 (July 8), number 513 (July 13), number 545(September 4), number 551 (September 10) In his Robespierre biography (2014), Hervé Leuwers writesthat, if it was Fréron who coined the nickname, Marat nevertheless did a lot to popularize it. Finally, his number 515 (July 9) Marat dedicates entirely to the ”superb speech” held by Robespierre regarding the flight to Varennes two weeks earlier. His admiration did not go unnoticed by other journalists besides Desmoulins, such as those behind Les Sabbats jacobites, who on April 10 1791 called Robespierre ”the hero of Marat” and those behind Journal générale de France who called him ”the god of Marat, Garat, Carra, Corsas and Marte” on June 13 the same year.

Once Robespierre on September 30 ceases to be a member of the National Assembly, the apperences of his name in l’Ami du peuple do however rapidly decrease, only appearing two more times (number 603 (November 19), number 618, December 6) until Marat temporarily puts it down on December 15.

The first actual meeting between Marat and Robespierre didn’t take place until January 1792, as revealed by the latter ten months later. By then, the two almost lived neighbors since about a month back, Marat having gone to live with the Evrard sisters on 243 rue Saint-Honoré in Decenber, not far from the Duplay house on number 366 on the same street.

One of the most terrible reproaches that people have aimed against me, I do not hide it, is the name of Marat. I will therefore begin by telling you frankly what my contacts with him have looked like. I could even make my profession of faith on his behalf, but without saying more good or more bad than I think, because I do not know how to translate my thoughts to appeal to general opinion. In January 1792, Marat came to see me. Until then, I had not had any kind of either direct or indirect relationship with him. The conversation turned to public affairs, about which he spoke to me with despair. I told him everything that the patriots, even the most ardent ones, thought of him; namely that he himself had put up an obstacle to the good that could be produced by the useful truths developed in his writings, by persisting in eternally returning to extraordinary and violent proposals (such as that of making five to six hundred guilty heads fall), which revolted the friends of liberty as much as the supporters of the aristocracy. He defended his opinion; I persisted in mine, and I must admit that he found my political views so narrow that some time later, when he had resumed his journal, which had been abandoned by him for some time, reporting on the conversation of which I have just described speaking, he wrote in full that he had left me, perfectly convinced that I had neither the views nor the audacity of a statesman; and if Marat's criticisms could be titles of favor, I could still place before your eyes some of his sheets, published six weeks before the last revolution, in which he accused me of feuillantism, because I, in a periodical work, did not say out loud that the constitution had to be overthrown. After this first and only visit from Marat, I found him again at the National Assembly.

In number 648 (May 18) of l’Ami du Peuple, Marat gives his own version of this meeting:

I therefore declare that not only does Roberspierre [sic] not have my pen at his disposal, although it has often served to do him justice; but I protest that I have never had any note from him, that I have never had any direct or indirect relationship with him, that I have never even met him but once; also in this instance, our interview served to give rise to ideas and to manifest feelings diametrically opposed to those that Guadet and his clique attribute to me. The first word that Robespierre addressed to me was the reproach of having myself partly destroyed the prodigious influence that my paper had on the revolution by dipping my pen in the blood of the enemies of liberty, by speaking of rope, of daggers, no doubt against my heart, because he liked to convince himself that these were just empty words dictated by circumstances. Learn, I replied to him immediately, that the influence that my paper had on the revolution was not due, as you believe, to these close discussions in which the vices of the fatal decrees prepared by the Constituent Assembly are methodically developed, but to the terrible scandal that it spread among the public, when I unceremoniously tore the veil which covered the eternal plots hatched against public liberty by the enemies of the fatherland, people conspiring with the monarch, the legislators and the main custodians of authority; but to the audacity with which I trampled underfoot every detracting prejudice; but to the outpouring of my soul, to the impulses of my heart; to my violent protests against oppression, to my impetuous outings against the oppressors; to my painful accents; to my cries of indignation, fury and despair against the scoundrels who abused the trust and power of the people to deceive them, rob them, load them with chains and precipitate them into the abyss. Learn that there has never been a decree attacking liberty and that never an official has allowed himself an attack against the weak and the oppressed, without me having hastened to raise the people against these unworthy prevaricators. The cries of alarm and fury that you take for empty words were the naive expression with which my heart was agitated; learn that if I had been able to count on the people of the capital after the horrible decree against the garrison of Nancy, I would have decimated the barbaric deputies who had issued it. Learn that after the investigation of the Châtelet on the events of October 5 and 6, I would have had the unfair judges of this infamous tribunal perished at the stake. Learn that after the massacre on the Champ-de-Mars, had I found two thousand men animated by the feelings which tore me apart, I would have gone at their head to stab the general in the middle of his battalions of brigands, to burn the despot in his palace and impale our atrocious representatives on their seats as I declared to them at the time. Robespierre listened to me with fear, he turned pale, and remained silent for some time. This interview confirmed for me the opinion that I had always had [sic] of him: that he combined with the knowledge of a wise senator the integrity of a truly good man and the zeal of a true patriot, but that he also lacked the views and audacity of a true statesman.

In 1793, Jacques Roux also claimed to have gone home to Marat the year before and there have received ”a letter for Robespierre and for Chabot, the goal of which was to interest the Jacobin club to propagate an edition of your works.” I can however find no letter from Marat to Robespierre in the latter’s correspondence, nor even a letter to or from Robespierre that so much as mentions Marat (and the same thing goes for Marat’s correspondence). So did Robespierre actually receive this letter, we might assume he didn’t think all that much about it.

Despite Robespierre’s frosty attitude, Marat continued to hold admiration for him when he started up his journal again on April 12 1792, dedicating almost all of number 648 (May 3) and number 660 (May 29) with defending him against girondin attacks, a struggle which he describes as existing ”between the traitor Brissot and the Incorruptible Robespierre” (number 643 April 28 1792).

On September 9, Robespierre held a speech which he ended by recommending voting for Marat and Legendre for the National Convention (he did however deny that be had singled out Marat ”any more particularly than the courageous writers who had fought or suffered for the cause of the revolution” two months later). On September 21 1792, the day after the opening of said Convention, the last number of l’Ami du peuple appears, and a few days later Marat starts a new journal — Journal de la République française (it changed name to Le Publiciste de la République française in March 1793) that would run up until his death in July the following year. In total, Robespierre’s name gets mentioned around 35 times in this journal. As far as I can see, Marat does however appear to have cooled down a bit with his praising, mostly mentioning Robespierre in the context of reciting something he’s said or at tops mentioning him alongside other ”patriotic” deputies. In number 239, released the day before his death, Marat inserts a letter to Robespierre from a certain Labenette, ”orator of the people.”

The fact that Robespierre and Marat didn’t have any contacts with one another was not something that was believed by all contemporaries. Already in 1791, the journal Le Défenseur du Peuple had describedthe former as ”the friend of Marat, who he pretends to doesn’t know.” These allegations got a lot more serious in the fall of 1792, with the two plus Danton being accused of wanting to form a triumvirate, or having arranged the September Massacres together. On September 25 Marat openly denied that any of these allegations aligned with reality, that he had discussed the idea if a dictatorship or triumvirate with Danton and Robespierre, but that both had rejected it:

Certain members of the Paris deputation are accused of aspiring to dictatorship, to triumvirate, to tribunate; This absurd indictment can only find supporters because I am part of this deputation: well! monsieurs, I owe it to justice to declare that my colleagues, notably Danton and Robespierre, constantly rejected any idea of dictatorship, triumvirate and tribunate, when I put it forward; I even had to break several lances with them on this subject.

The very same day, Robespierre made allusions to Marat when regretfully declaring ”it was then that the thoughtless phrases of an exaggerated patriot or the signs of confidence he gave to men whose incorruptibility he had experienced for three years were attributed to us as crimes.”

On October 19 appeared the first number of Lettres de Maximilien Robespierre, membre de la Convention nationale de France, à ses commettants. In number 6, when discussing Marat getting interupted when laying out some own theories on the battalions of Mauconseil to the point that the Jacobins have to move with the agenda due to the tumult, Robespierre writes: ”Whatever the deviations of Marat's imagination, good citizens nonetheless groaned to see personal sentiments make the interests of immocence and oppressed patriotism forgotten, and hateful passions banished from the sanctuary of the laws. dignity, calm and love of humanity.” In number 9 he also writes that ”in his wanderings, Marat often encountered the truth.”

Robespierre also mentioned Marat when the Lettres in January 1793 got renewed for a second edition, starting already in number 1, where he for long defended himself against the girondin Gensonné linking him and Marat together:

What obstinacy to want me to be someone other than myself? It doesn't even matter to you that everyone believes that I named Marat: having been unable to succeed, you have decided to repeat my name so often with his, that I was at least taken for an accessory of this great character, so celebrated in your pages; as if I had not had an existence of my own, several years before you had decided to strip me of it; as if my constituents and my fellow citizens had not been able to judge me by my own actions; while Marat wrote underground, and Brissot still obscurely intrigued, with the henchmen of the old police, his colleagues, and crawled in the antechambers of the men in power. In the past, I still remember, Brissot and a few others had entered into I don't know what conspiracy to make my name almost synonymous with that of Jérôme Pétion; they took so much trouble to put them together. I don't know if it was for love of me or of Pétion: but they seemed to have plotted to send me to immortality, in company with the great Jérôme. I have been ungrateful; and, to punish me, they said: since you don't want to be Pétion, you will be Marat. Well, I declare to you, monsieurs, that I want to be neither. I have the right, I think, to be consulted on this, and you will perhaps not dispose of my being in spite of myself.

It's not that I want to deny Marat the justice that is due to him. In his papers, which are not always models of style or wisdom, he nevertheless stated useful truths, and waged open war against all powerful conspirators, although he may have been wrong about a few individuals. I know that he did not spare you yourselves: but this merit has not erased in my eyes, these extravagant sentences which he sometimes mixed with the healthiest ideas, as if to give to you and to your likes, the pretext of slandering liberty. It was said a long time ago that, in this respect, Marat was the father of the moderates and the feuillans; we could say for the same reason that he is also your boss; and we would be tempted to believe that he only punishes you because he loves you. I bet you love him too, although you pretend to shout very loudly at the slightest correction he gives you. Indeed, what would you be without him? What would become of all your newspapers and all your harangues if he had not written these two or three absurd and bloodthirsty sentences, which you constantly strive to repeat and comment on? You would have perhaps been reduced to becoming patriots, if he had not provided you with the pretext of disguising patriotism as maratism, in order to give to incivism, feuillantism, royalism and rascality, I don't know what air of wisdom and moderation.

It is so convenient for the enemies of liberty to simply appear to be the adversaries of Marat, and to confuse the cause of liberty with the person of an individual, in order to be excused from respecting it. Such was the policy of the first aristocrats, and of the heroes of the intrigue, whose disgraces you will share, after having imitated their exploits. Like them, you want to persuade all of Europe that the Republicans of France, that the partisans of the principles of equality, are only one faction, and that this faction is Marat himself. Thus, thanks to the gift of metamorphoses with which you are eminently endowed, Paris, the Jacobins, the members of the Convention, who do not bend to the views of the intriguers, and Marat are precisely the same thing. All the energetic friends of liberty are, at most, only satellites drawn into the whirlwind of this new star. With this magical name, you claim to overthrow the entire work of our revolution. It is to carry out this great work that you write, that you print, that you speak, that you plot tirelessly: but the revolution will triumph over the name of Marat, as well as over your intrigues; we will do justice to you and to him, by disproving his deviations and by disconcerting your plots. A journalist's sentences have never made a guilty head roll; but the plots of ambition that you seem to forget have caused torrents of human blood to flow. The crimes of tyranny cost humanity more disasters than the most heroic periods of the most atrocious writer. Only you, gentlemen, can give importance to an exaggerated man, much less through your declamations than through your conduct. It would not even be noticed under a wise government. It is only oppression that forces the people to pay less attention to faults that they themselves do not believe, than to the courage of those who unmask their enemies.

He defends himself against the charge of him and Marat being the leaders of a coalition, ”when these deputies, too independent to form a coalition, even with a view to the public good, see every day the coalition of factions.” again in number 3. In number 9, the second to last number, he rhetorically asks whether ”giving ridiculous importance to some inconsistent and bizarre journalist, to charge him with all the iniquities of Israel, and to identify with him all the defenders of freedom?” really is such a good way to ensure tranquility.

Between December 1792 up until the death of Marat, we find him and Robespierre taking part in the same debates at both the Convention and the Jacobin club, sometimes agreeing (December 26, February 21) and sometimes disagreeing (December 16, March 3, June 18) with each another.

On January 4 Robespierre complains that a speech made by Barère regarding the fate of Louis XVI ”contains the most violent diatribes against the patriots” for having stated ”If anything could have made me change my mind [on an appeal to the people], it would be to see the same opinion shared by a man whom I cannot bring myself to name (Marat), but who is known for his bloodthirsty opinions...” A month later, February 11, Marat and Robespierre together calmed down a group of petitioners, disgruntled over not having received a hearing at the Convention. When a representative on February 26 asked ”that Marat be temporarily expelled from the Assembly and be locked up so that it could be examined whether he was crazy” and another one ordered the referral of the denunciation to the ordinary courts, ”Robespierre approaches the president, and there he announces that if the decree passes, Paris will be burning today.”

On 12 April Robespierre spoke against the arrest order issued against Marat the very same day — ”One has requested a decree of accusation be drawn up against the warmest patriots […] Marat spoke with force, precision, and at the same time with moderation. He painted the crimes of our enemies with colors capable of making any man who has any sense of modesty blush.…”

When the indictment against Marat was presented on April 13, Robespierre took to the floor a total of three times to speak against it:

To the question that agitates us, we will not disagree that the man in question excites very strong passions; you are asked if you will decree a representative of the people immediately, or if you will postpone until Wednesday; there is no respect there for the principles, and for what we owe to the character of representative of the people: what, you would send a slanderous report, when nothing is proven, and is it not barbaric to put a representative under accusation without examination; this report is the fruit of passions and liberticidal conspiracies. […]

Yes, it will be proven that this man, whom I have always seen as patriotic, was only attacked to prove that all the Republicans in this Assembly are exaggerated and must suffer the same fate.

…As I see in this whole affair only the developed spirit of the Feuillants, the moderates and all the cowardly assassins of liberty, only a vile intrigue hatched to dishonor patriotism, the departments infested for a long time with the liberticidal writings of royalists, I reject with contempt the proposed decree of accusation.

Marat was acquitted on April 24, and four days later, a motion proposed by him with an amendment from Robespierre was passed at the Jacobin Club.

One day after the murder of Marat, July 14 1793, Robespierre spoke against the idea of granting him a state funeral, arguing that there were much more urgent things that needed to be taken care of before that could happen:

Robespierre: I have little to say to the Society. I would not even have asked to speak had the right to do so not somehow devolved to me at this moment; if I did not foresee that the honors of the dagger are also reserved for me, that priority has only been determined by chance, and that my fall is fast approaching. When a man, deeply sensitive and imbued with a love of the public good, sees his enemies raise their heads with impunity, and already share the spoils of the State, and his friends, on the contrary, frightened by oppression, flee a murderous soil and abandon it to fate, he becomes insensitive to everything, and no longer sees in the tomb anything other than a safe and precious asylum reserved by Providence for virtue. I believed that a session which followed the murder of one of the most zealous defenders of the fatherland, would be entirely occupied with the means of avenging him by serving said fatherland better than before. We haven't talked about it, and what are you occupying yourselves with in this precious time, for the use of which we are accountable? We are dealing with outrageous hyperboles, ridiculous and meaningless figures, which do not provide a remedy to the thing at hand and prevent it from being found. For example, you are seriously asked to discuss the fortune of Marat. Well! What does the fortune of one of its founders matter to the Republic? Is it a memoir that we are going to occupy ourselves with, when it is still a question of fighting for it? One is speaking of the honors of the Pantheon. And what are these honors? Who are those who lie there? With the exception of Le Peletier, I can’t see a single virtuous man there. Is it next to Mirabeau we will place Marat? Next to this intriguing man whose means were always criminal; this man who only earned his reputation through profound villainy? Here we have are the honors requested for the Friend of the People.

Bentabole: Yes, and he will obtain them in spite of those who are jealous of him.

Robespierre: Let us occupy ourselves with the measures which can still save our fatherland; let's make the effect of Pitt's guineas null. Let's bring the Cobourg and the Brunswick back to their territories. It is not today that we must show the people the spectacle of a funeral ceremony, but when finally victorious, the strengthened Republic will allow us to take care of its defenders; all of France will then ask for it and you will undoubtedly grant Marat the honors that his virtue deserves, that his memory demands. Do you know what impression the spectacle of funeral ceremonies attaches to the human heart! They make the people believe that the friends of liberty are thereby compensating themselves for the loss they have caused, and that from then on they are no longer required to avenge it; satisfied with having honored the virtuous man, this desire to avenge him dies in their hearts, and indifference succeeds enthusiasm and his memory runs the risk of oblivion. Let us not stop seeing what can still save us. The assassins of Marat and Peletier must come and atone on the Place de la Révolution for the atrocious crime of which they are guilty. It is necessary that the perpetrators of tyranny, the unfaithful representatives of the people, those who display the banner of revolt, who are convinced that they are sharpening the daggers on their heads every day, of having murdered the fatherland and a few of its members; it is necessary, I say, that the blood of these monsters responds to us and avenges us for that of our brothers which flowed for liberty, and which they shed with such barbarity. We must share the most painful burdens of the State; one must instruct all the people and gently lead them back to their duties; the other must render them exact justice: one must make food flow everywhere; the other deals exclusively with agriculture and the means of multiplying its relations; another must make wise laws; someone else must raise a revolutionary army, exercise and harden it, and know how to guide it in battle. Each of us must, forgetting ourselves at least for a while, embrace the Republic and devote ourselves unreservedly to its interests. The municipality must rule out, for the moment, a funeral celebration, which at first seemed dear to our hearts, but whose effects, as I have demonstrated, can become disastrous.

The following day, July 15, Robespierre asked that Marat’s printing presses be obtained by the Jacobins, a request a different member had already made the day before. A week later, July 22, the club tasked Robespierre, Desmoulins, Dufourny and Le Peletier’s brother with writing an adress to the French people about the murder. Said adress was printed and read aloud at the club four days later, obviously deploring of the event and praising Marat.

On August 5, Robespierre denounced Jacques Roux and Jean Théophile Victor Leclerc as ”two men paid by the enemies of the people, two men that Marat denounced [that] have succedeed, or think they have succeeded this patriot writer.” Three days later, August 8, Simonne Evrard, ”the widow Marat” presented herself before the Convention and held a long speech defending her dead fiancé’s memory, that in her view had gotten hijacked by ”scroundel writers” and in particular the two men already denounced by Robespierre. After her speech was finished, Robespierre again took to the floor to demand that the speech be printed and ”that the Committee of General Security be required to examine the conduct of the two mercenary writers denounced to it; the memory of Marat must be defended by the Convention and by all patriots.” Indeed, Roux and Leclerc would soon thereafter find themselves imprisoned, the former in September 1793, the latter in April 1794. How much of this was Robespierre being genueinly concerned for Marat’s memory and how much it was him using said memory to rid himself of a political rival I will leave unsaid…

On November 23, when Robespierre gives clarifications regarding the CPS changing the general in charge of the taking of Toulon, he says that it was on the recommendation of Marat that the new general had been promoted to rank of brigade leader. ”Marat could have been wrong, but his recommendation was a very favorable presumption in favor of an individual; he has always justified it since.” On 10 January 1794 he exclaims that ”my dictatorship is that of Le Peletier, of Marat. Or I don’t mean that, I don't want to say that I resemble them: I'm neither Marat nor Pelletier; I am not yet a martyr of the Revolution; I have the same dictatorship as them, that is to say the daggers of tyrants.” In an undelivered speech written shortly thereafter he again describes Marat and Le Pelerier as martyrs and Leclerc and Roux as”mercenary writers, daring to usurp the name of Marat, to desecrate it.”

Finally, on 9 thermidor, we find the following two claims made against Robespierre that involves Marat. (1, 2) I will leave them as they are as it’s very hard to know if they’re legit or not:

Dubois-Crancé: I must pay tribute to the sagacity of Marat: at the time of the judgment of the tyrant Capet, he said to me, speaking of Robespierre: ”You see that rascal? That man is more dangerous for liberty than all the allied despots.”

Collot d’Herbois: I am going to cite a fact which will prove that Robespierre, who for some time spoke only of Marat, always hated this constant friend of the people. At Marat's funeral, Robespierre spoke for a long time on the platform that had been set up in front of the Luxembourg, and the name of Marat did not come out of his mouth once; Can the people believe that a person loves Marat when he angrily declares that he doesn’t want to be assimilated to him? No, although these hypocrites talked incessantly about Marat and Challier, they loved neither of the two.

Alphonse Esquiros, who tracked down Marat’s younger sister Albertine for an interview in the 1830s or 1840s, reported that it was ”with bitterness” she spoke of Robespierre. ”There was nothing in common, she added, between him and Marat. Had my brother lived, the heads of Danton and Camille Desmoulins would not have fallen.”

Robespierre’s little sister Charlotte (who Albertine despised) did in her turn write the following regarding the relationship in her memoirs (1834). This anecdote is however suspeciously similar to the meeting Marat and Robespierre describe as having happened in January 1792, in which Charlotte impossibly could have taken part, still not having gone to Paris by then:

I have often heard my brother’s name attached to that of Marat, as if the way of thinking, the sympathies, the acts of those two men were the same, as if they had acted in concert. It is thus that the portraits and busts of Voltaire and Rousseau are placed side by side, as if those two great writers had been the best friends in the world when they were alive, while in truth they found each other insufferable. I do not claim to discount Marat’s merit, nor make an attempt on the purity of his devotion and of his intentions. Some have dared to say that he was in the pay of foreigners; but have they not said that of my brother? The field of the absurd is immense and limitless. Have they not said of Maximilien Robespierre that he had asked the young daughter of Louis XVI in marriage? After such an accusation nothing should be surprising anymore; more burlesque and impossible assertions must be expected; it is the nec plus ultra of inanity. To return to Marat, I will dare to affirm that he was not an agent of foreigners, as it has pleased some to say; Marat had felt the infamies of the Ancien Régime and the poverty of the people strongly; his fiery imagination and his irascible temperament had made him an ardent, and too often even imprudent, revolutionary; but his intentions, I repeat, were good. My brother disapproved of his exaggerations and his rages, and believed, as he said many times to me, that the course adopted by Marat was more detrimental than useful to the revolution. One day Marat came to see my brother. This visit surprised us, for, usually, Marat and Robespierre had no rapport. They spoke first of affairs in general, then of the turn the revolution was taking; finally, Marat opened the chapter on revolutionary rigors, and complained of the mildness and the excessive indulgence of the government. “You are the man whom I esteem perhaps the most in the world,” Marat said to my brother, “but I would esteem you more if you were less moderate in regard to the aristocrats.” “I will reproach you with the contrary,” my brother replied; “you are compromising the revolution, you make it hated in ceaselessly calling for heads. The scaffold is a terrible means, and always a grievous one; it must be used soberly and only in the grave cases where the fatherland is leaning toward its ruin.” “I pity you,” said Marat then, “you are not at my level.” “I would be quite grieved to be at your level,” replied Robespierre. “You misunderstand me,” returned Marat, “we will never be able to work together.” “That’s possible,” said Robespierre, “and things will only go the better for it.” ”I regret that we could not come to an understanding,” added Marat, “for you are the purest man in the Convention.”

#robespierre#marat#jean paul marat#maximilen robespierre#frev#frev friendships#ask#unrelated but the relationship between marat’s little sister and fiancée really was the polar opposite to robespierre’s counter parts…

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

♚♛ EUROPEAN MONARCHS AND THEIR HEIRS ♛♚

───────────── ⋆⋅☆⋅⋆ ─────────────

♔ UNITED KINGDOM┆ King Charles III → William, The Prince of Wales → Prince George of Wales

♔ SPAIN┆King Felipe VI → Princess Leonor, The Princess of Asturias

♔ BELGIUM┆ King Philippe → Princess Elisabeth, Duchess of Brabant

♔ SWEDEN ┆ King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden → Crown Princess Victoria, Duchess of Västergötland → Princess Estelle, Duchess of Östergötland

♔ DENMARK ┆ Queen Margrethe II → Crown Prince Frederik → Prince Christian

♔ NORWAY ┆ King Harald V of Norway → Crown Prince Haakon → Princess Ingrid Alexandra

♔ LUXEMBOURG ┆ Grand Duke Henri → Hereditary Grand Duke Guillaume → Prince Charles

♔ NETHERLANDS┆ King Willem-Alexander → Princess Catharina-Amalia, Princess of Orange

♔ MONACO┆ Prince Albert II → Hereditary Prince Jacques, → Princess Gabriella, Countess of Carladès

#prince of wales#the prince of wales#prince william#prince george of wales#prince george#king charles iii#queen margrethe ii#crown prince frederik#prince christian#king harald v#crown prince haakon#princess ingrid alexandra#king carl xvi gustaf#crown princess victoria#princess estelle#king philippe#princess elisabeth#king felipe#princess leonor#grand duke henri#hereditary grand duke guillaume#prince charles of luxembourg#king willem alexander#princess catharina amalia#prince albert ii#prince jacques#princess gabriella#my gifs#my edit#european monarch and their heirs

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why George Russell's Disqualification is Really Napoleon's Fault

Alright motorsports fans, with the end of the Belgian Grand Prix (held before the summer break this year because the F1 calendar is becoming increasingly cursed year after year) F1 enters its summer break. NASCAR and Indycar are on an Olympic break thanks to both series currently being on NBC (who is the US broadcaster of the 2024 Paris Olympics), and MotoGP doesn't come back from its second summer break until next week.

So what the hell am I going to talk about in this blog.

Well, George Russell won the 2024 Belgian Grand Prix until he got disqualified for having an underweight car. Some people have theorized that Mercedes made a mistake and underfueled him, others have said that George switching to a one-stop meant he lost out of valuable pitlane speed time, using up more fuel, still others have theorized it's down to the unique procedures at Spa - where drivers turn around after turn one and drive the wrong way into pit exit - that meant Russell didn't have the chance to pick up rubber and thus increase the weight of his tyres.

I, meanwhile, have a different theory.

George Russell could only have been disqualified from the Belgian Grand Prix because of Napoleon!

Yes, really.

How, you may ask? Well, the Napoleonic Wars created the conditions that ultimately allowed for the the Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps to exist. Thus, the long lap that causes F1 cars to deliberately underfuel for the race, the unique post-race procedures due to track length, and choice of this area as the venue for the Belgian Grand Prix...none of that would've been possible with Napoleon.

Our story, as all good motor racing stories do, begins in 651 when the Benedictine Monk, Saint Remaclus of Stavelot founded the dual Abbeys of Stavelot and Malmedy (which you may recognize from corner names of the Spa-Francorchamps circuit, as these are neighboring villages).

These abbeys wound gain more territory in 747 when Carloman, the Majordomo of the Franks and uncle of Charlemagne, abdicated and became a monk himself.

They would be enlarged again in 882 by Charles the Fat, Holy Roman Emperor, in compensation for the Normans raiding and burning down both abbeys the previous year.

Thus, the Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy became one of the many mosaic pieces of the complex historical mindscrew that is the Holy Roman Empire, holding territories along what is now the Belgian-Germany border. Back then though, they were a rather significant ecclesiastical territory, holding land where Lothringia met the Low Countries.

This was the exact region where, in the late 15th and early 16th century, the Dukes of Burgundy attempted to create their own sovereign territory, using the chaos of the Hundred Years War in France to become lords over Luxembourg, Hainaut, Flanders, Brabant, and Holland. Soon enough, the Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy was one of only three independent states remaining in the region.

It was Stavelot-Malmedy, an ecclesiastical state which thus couldn't easily be absorbed into secular Burgundy.

Then the Prince-Bishopric of Liege, which again, was an ecclesiastical state which meant it would be a tricky proposition for a Catholic Duke of Burgundy to try and conquer.

And finally the Duchy of Bouillon, which was a downright weird state in that the title was a secular Duchy that was sold to the Prince-Bishopric of Liege, and in the late 17th century became a sovereign possession of the La Tour d'Auvergne, a French noble family.

In any case, upon the death of the Burgundian line, their territories were divided between France, the feudal overlord of Burgundy, and Philip the Handsome (the son of Mary the Rich, the last Duchess of Burgundy, and Maximilian von Habsburg, an Austrian Prince).

Philip the Handsome was in turn married to Joanna the Mad (we should bring back the random ass nicknames people used to get in the past btw), the Queen of Castile and Aragon. Their son, Charles, would thus inherit Spain, the Burgundian possessions in the Low Countries, and, eventually, Austria and the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Yeah.

So thanks to Charles V rolling a natural 20 in his birth dice roll, Stavelot-Malmedy was suddenly one small little ecclesiastical holding squeezed between the two halves of what would eventually become known as the Spanish Netherlands.

Then, the northern half of the Spanish Netherlands decided they didn't want to be Catholic anymore. This ushered in the Dutch Revolt of the 17th century, a bloody religious struggle concurrent with the Thirty Years War and the Portuguese War of Independence that marked the end of the golden age of Spanish power.

Come 1700 and Charles II of Spain (Charles V was Charles I in Spain, regnal numbers get weird when you rule over half of Europe), the last Habsburg King of Spain, dies an inbred and infertile mess. The Low Countries become a battleground in the War of the Spanish Succession.

On one side, France and Spain, as Charles II had declared his grandnephew, the French Prince Philip of Anjou, threatened to tip the scales of western Europe towards the Bourbon dynasty.

On the other side, a grand coalition of Austria, England, the Dutch Republic, Prussia, Portugal, and Savoy aimed to contain French power.

This was the War of the Spanish Succession, and the war would be transformative for the southern Low Countries. The Spanish Netherlands went back to Habsburg hands and became the Austrian Netherlands, meanwhile, the Duchy of Cleves, just to the east, was returned to Prussia following a French occupation.

The Dutch Republic in the north was Protestant, the Austrian Netherlands were Catholic, and Protestant Prussia was emerging on the scene as well. This would more or less lay the stage for the Napoleonic Wars, where the armies of the French Republic and later the French Empire would occupy all of this land. Gone were the Austrian Netherlands, gone was Stavelot-Malmedy, Liege, and Bouillon, and gone was Prussian Cleves.

Instead, the land surrounding Spa-Francorchamps would became part of the French Department of Ourthe, named for one of the principal rivers of the region.

However, much like the War of the Spanish Succession, numerous grand coalitions would rise up against Napoleon, the primary participants being Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, the Dutch, and Russia. In 1815, they would finally defeat Napoleon once and for all, and the Peace of Vienna would shape the new postwar Europe.

Of the old Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy, Stavelot would go to the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (the new kingdom combining the modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg), while Malmedy would go to the Kingdom of Prussia.

The border would be a minor tributary of the River Ambieve known for its reddish water. The name? Eau Rouge.

Fast forward to 1830 and the largely Catholic southern Netherlands revolt from their Protestant overlords in the north and demand the creation of a Kingdom of Belgium. Following a great power conference in London, the Belgians would get their wish, and in 1831, the Kingdom of Belgium was born, including Stavelot.

The Dutch would recognize Belgium Independence in 1839.

Eau Rouge was now the Belgian-Prussian border.

Come 1871, and Prussia becomes the German Empire.

Come 1914, and this border region is amongst the first overrun by the Germans in World War I. Spa becomes a major German field hospital from the get-go, and by 1918, Spa is the German military headquarters and the primary residence of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Upon the German surrender in 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm would abdicate and leave for the Netherlands, meanwhile, France and Belgium - the countries that wore the greatest scars from World War I - would demand harsh reparations from Germany. For Belgium, this would include Eupen-Malmedy.

Thus, the great majority of the old Princely Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy was now within Belgian borders.

Jules de Thier, owner of the La Meuse newspaper in Liege, found this new territory to be the perfect site for a high-speed triangular race track in 1921. The race would begin in old Belgium, with a run to the old border - originally they would veer right, pass through Ancienne Douane - the old customs office on the Belgian-Prussian border - then back left to rejoin the track on the other side of what is now the Eau Rouge corner - then run through the German territories.

Burnenville and Malmedy were in old Germany, then swing back at the bottom of the track, crossing back into pre-war Belgian territory in time for the Masta kink, then Stavelot, Blanchimont, and La Source would all be in pre-war Belgium as well. Cross the start-finish line after La Source (as it was back then) and then cross into former Germany again on the next lap.

Thus, the Belgian Grand Prix was born in a region that had only just been annexed from Germany.

This led to Spa again becoming a battlefield during World War II, but with the borders restored after the war, Spa would again be in Belgium and, from 1950, the Belgian Grand Prix would become a traditional staple on the Formula One calendar.

Spa-Francorchamps would be transformed a couple of times over, not assuming its current form until 2007, but it was born from the great Napoleonic shakeup in European politics.

The ancient double abbeys of Stavelot-Malmedy were separated for the first time in 1200 years, and it would take another century for them to be reunited in modern Belgium.

So yeah, if you're mad that George Russell was disqualified, blame Napoleon...or Kaiser Wilhelm II I suppose, whichever one fits your fancy.

Oh, and by the way, Lewis Hamilton takes a record-extending 105th win following his teammate's disqualification, so I suppose Mercedes still has something to be happy about.

#motorsports#racing#f1#formula 1#formula one#yeah this is just a self-indulgent blog from a history major#no one is gonna care about this blog but I had fun writing it#spa francorchamps#belgian gp 2024#belgian grand prix

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Léopold Philippe Charles Albert Meinrad Hubert Marie Michel of Belgium, Duke of Brabant, later King Leopold III

Belgian vintage postcard

#hubert#philippe#leopold#sepia#king#marie#photography#léopold philippe#charles#vintage#charles albert meinrad hubert marie michel#michel#brabant#postkaart#meinrad#leopold iii belgian#later#prince#ansichtskarte#ephemera#carte postale#postcard#postal#briefkaart#belgian#duke#photo#belgium#lopold#tarjeta

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

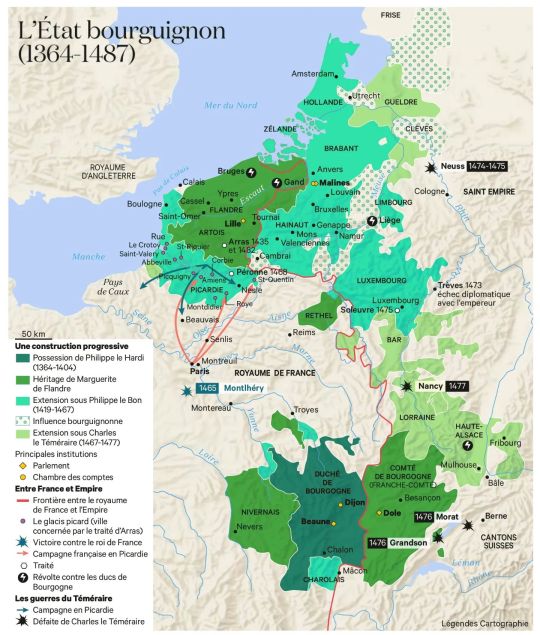

The Burgundian state, 1364-1487.

« Atlas historique mondial », Christian Grataloup, Les Arènes/L'Histoire, 2e éd., 2023

by cartesdhistoire

In 1363, the king of France, John the Good, gave Burgundy as an appanage to his son Philippe the Bold. Duke until 1404, he became master of a vast area, including Charolais, Artois, Franche-Comté, Rethel, Nevers and Brabant. His power made Flanders independent and it was a solid base for expansion in the Empire, continued by Duke Philip the Good (1419-1467): Namur, Hainaut, Holland, Zeeland and Luxembourg ( in addition to a nebula of satellites like the ecclesiastical principalities of Liège, Utrecht and even Cologne).

The Burgundian “State” is therefore made up of two blocks of territories, both shared between France and the Empire: Burgundy (France) and Franche-Comté (Empire) are governed from Dijon; from Lille then from Brussels from 1430, Flanders, Artois (France) and the Netherlands (Empire). The frequent meeting of States within the framework of each province allows regular taxation, which makes the Duke one of the richest sovereigns in the West, the bulk of his income coming from Flanders and the Netherlands. The administrative structure is close to that of the French monarchy (aids, Chambers of Accounts, states, Parliament).

Duke Charles the Bold (1467-1477) tried to reunite the two blocks, barely 60 km apart after 1441. He centralized, increased taxes and borrowed enormous sums from banks to obtain an imposing army and artillery. He then aimed for Lorraine and the archbishopric of Cologne but his ambitions united his enemies against him: Louis XI, the emperor, Lorraine, Savoy and the Swiss. In 1475, the Swiss crushed Charles's army at Grandson and Morat then the duke died in 1477, trying to retake Nancy. He is succeeded by his daughter Marie who married Maximilien, son of the emperor. She died on March 27, 1482 and on December 23, the Treaty of Arras divided her inheritance between Valois and Habsburg.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the buildings to which Paleizenplein ("palaces square") in Brussels owes its name is the Palace of the Academies, which currently houses most of Belgium's academies.

From 1828 to 1830 it was the home of Crown Prince William of Orange-Nassau and his consort Anna Paulowna, daughter of Tsar Paul and Grand Duchess of Russia whrn Belgium (or Southern Netherlands) were part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands which was created after the battle of Waterloo in 1815. Later It was also temporarily the home of Crown Prince (of Belgium which was established in 1830) Leopold, at that time titled Duke of Brabant, to which Hertogsstraat (" Duke's street") refers. The palace is a late but pure example of neoclassicism, the palace style of the Enlightenment. This architectural gem was drawn according to pure geometric proportions, Renaissance symmetry and axiality.

The neoclassical building was built between 1823 and 1828 on the site of the Park Abbey refuge house. The state architects Charles Vander Straeten and Tieleman Franciscus Suys also carried out one of the renovations of the adjacent Royal Palace of Brussels in the same period. It was financed to the amount of 1,215,000 guilders with resources from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and on behalf of William I. The palace was furnished for his son, Crown Prince Willem and his Russian wife Anna Pavlovna. On the night of September 25 to 26, 1829, the palace was broken into. The thieves stole Anna Pavlovna's jewelry from her bedroom and escaped with it.

After the Belgian Revolution, the palace came under sequestration. An army regiment were given shelter there. It would take until 1842 before a compromise was found. The building was transferred to the Belgian state and the sumptuous contents went to the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The contents were transferred to the Kneuterdijk Palace and after the death of William II to the Noordeinde Palace, where many pieces can still be admired.

From 1848 to 1852, the palace was the location of the first regiment of Jagers-Carabiniers. King Leopold II refused to move into the building that was offered to him in 1853. It was decided to use it for ceremonies and celebrations. The interior was renovated under the supervision of architect Gustave De Man. However, in 1862 the Museum of Modern Art was housed in the palace, pending the completion and furnishing of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. It would still house works of art until the Royal Academies of Belgium were allowed to settle there (royal decree of April 30, 1876).

Interior: