#carthaginian empire

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Five Rare 2,300-Year-Old Gold Coins Discovered in Ancient Carthage

Researchers made the discovery during excavation works in the North African nation of Tunisia, in an area that once formed part of the territory of ancient Carthage, the country's Ministry of Cultural Affairs has announced in a statement.

Carthage was a great city of antiquity founded by the Phoenicians on the north coast of Tunisia in the first millennium B.C. The city became a thriving port and trading center, eventually developing into a significant power in the Mediterranean. Carthage became a major rival to Rome, which eventually conquered and destroyed the city in 146 B.C.

The archaeological site of ancient Carthage-added to UNESCO's World Heritage List in 1979-lies in what is now a residential suburb of modern Tunisia's capital Tunis.

Carthage had a sacred site known as a "tophet," which served as a burial ground, particularly for young children.

Thousands of urns containing the ashes of young children have previously been found at the site, which was originally dedicated to the deities Baal Hammon and Tanit.

It is here that archaeologists found the five gold coins dating back to the 3rd century B.C. in August, as well as several urns with the remains of animals, infants and premature babies.

The gold coins reflect "the richness of that historical period and [affirm] the value of the civilization of Carthage," the ministry said in a statement.

The rare gold coins measure around an inch across and have designs showing the face of Tanit-a symbol of motherhood, fertility and growth for the Carthaginians.

Archaeologists believe that the coins were left as offerings to Baal Hammon and Tanit by wealthy worshippers.

Tophets have been found at other Carthaginian sites, which were traditionally thought to house the victims of child sacrifice. Ancient Roman, Hellenistic and biblical sources attest to this, and some modern scholars agree.

However, the topic is controversial, with other experts arguing that tophets were simply children's cemeteries for individuals who died naturally, or that not all the burials were sacrifices.

The latest finds are not the only recent discovery of ancient coins. Earlier in August, a metal detectorist found two gold coins from different historical eras on the same day in a field in England.

In July, archaeologists uncovered several 500-year-old gold coins during excavations at the ruins of a medieval monastery in Germany.

Also in July, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced that a rare silver coin dated to the time of the First Jewish Revolt against the Roman Empire, between A.D. 66 and 70, had been discovered in the Judean Desert.

#Carthage#Five Rare 2300-Year-Old Gold Coins Discovered at Ancient Carthage#The Tophet of Carthage#ancient grave#ancient tomb#ancient temple#gold#gold coins#collectable coins#treasure#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#Carthaginian Empire

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Updated format for another one of my older maps: a rough overview of Carthage. Shows 3 points in time + suggestive trade range.

#maps#map#carthage#tunisia#phoenicians#punic#historical map#carthaginian empire#punic wars#europe#africa#maghreb#spain#italy#lybia#algeria#morocco

1 note

·

View note

Text

if anybody asks i am NOT using my very limited free time to git gud at 0 a.d. (a free and open-source real-time strategy video game under development by Wildfire Games. It is a historical war and economy game focusing on the years between 500 BC and 1 BC, with the years between 1 AD and 500 AD planned to be developed in the future)

#its such a fun game and the AI sometimes behaves super easy n kind and othertimes it eats u alive im having fun#kushites and carthaginians are so fun to play with too i<3 ancient northafrican empires

0 notes

Text

THE EMPIRE OF BONES is here!

It's serious Fuck It, What The Hell Hours, and so here it finally is, another of my original novels for your (hopeful) reading pleasure. This is a big fat fantasy novel filled with all the things I love:

Complex and detailed historically-inspired settings

Lots of political and magical intrigue

Explorations of war, slavery, empire, history, memory, magic, power, religion, family, and destiny

Diverse and flawed characters

Extremely sassy djinni (if you’ve read Bartimaeus by Jonathan Stroud, then you know)

IDIOT GAYS. Like, this baby can fit all kinds of moronic homosexuals. I cannot stress enough how many queers there are and how many of them are very, very stupid. Many of them cannot use their words and avoidable mishaps ensue.

Based (loosely) on my fic The Key of Solomon, so if you've read that, you'll like this.

@silverbirching has described it thus: "It's like. Everything I want in a book. Basically a queer magic political thriller set in an alternate-universe Roman Empire. Carthaginian noblewoman gets embroiled in a conspiracy against the 400-year-old immortal emperor and finds the Ring of Solomon. Gay Jewish boy makes incredibly terrible romantic decisions while pretending to be a wizard. There are two empresses and they are the worst and probably my favorite characters."

Buy it here:

Amazon: Kindle | Paperback

Lulu: Paperback | Hardcover

If you have enjoyed my many, many fics for various fandoms over the years, my political and historical writing/general internet presence, if you're on the hunt for something new to read, trust my taste in books, or just want to think about something the hell else for a while, I hope you'll consider checking it out. There is also a sequel in the works, assuming my muse ever returns to me after Hell Year, so yes.

348 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Carthaginian Army

The armies of Carthage permitted the city to forge the most powerful empire in the western Mediterranean from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE. Although by tradition a seafaring nation with a powerful navy, Carthage, by necessity, had to employ a land army to further their territorial claims and match their enemies. Adopting the weapons and tactics of the Hellenistic kingdoms, Carthage similarly employed mercenary armies from their allies and subject city-states. Military successes came in Africa, Sicily, Spain, and Italy, where armies were led by such celebrated commanders as Hamilcar Barca and Hannibal. Carthage's military dominance was, though, eventually challenged and bested by the rise of Rome and, following defeat in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), Carthage's days as a regional powerhouse were over.

The Carthaginian Empire

Carthage was founded in the 9th century BCE by settlers from the Phoenician city of Tyre, but within a century the city would go on to found colonies of its own. An empire was created which covered North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and other islands of the Mediterranean. The new territory would be a source of vast wealth and manpower. Conversely, this would also bring Carthage into direct competition not only with local tribes but also contemporary powers, notably the Greek potentates and later Rome. In turn, this created a necessity for large military forces, especially land armies.

Continue reading...

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aziraphale’s Flaming Sword

get your mind out of the gutter - seriously it’s gonna get worse

i’m sure someone has already pointed this out and some meta post have been made but I just wanted to infodump about the actual history behind this sword so yeah

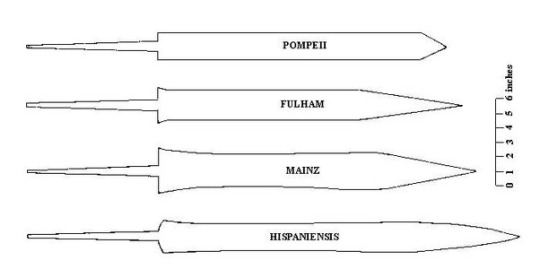

His sword is modeled after the Roman Gladius -or is it the other way around ;) - specifically the Pompeii version - so let’s just get into breaking this sword down

The Hilt

This type of sword has a three part hilt consisting of a pommel (which is used to counterweight the blade), a grooved wood grip (so your fingers fit better and thus have a stronger grip), and a guard (protects the hands from slipping onto the blade)

The Blade

For the Pompeii version of this sword it has double-edge sides that are parallel and come to a short, strong point - typically it would be made out of steel

Size

Usually ranged from 18-28 inches as it continually got smaller and smaller over the years

The History

(the most widely excepted one at least)

The Pompeii is actually one of the latest versions of the Roman Gladius so let’s go back to the beginning

The official origins of this sword have been up for debate but as for how it came under Roman influence that is credited to the Punic Wars in 3rd century B.C. (Republican Rome) - specifically to the Iberians who were allies to the Carthaginians and used a short sword that came to be called the “gladius Hispaniensis.” After the wars the Roman army (besides the cavalry) adopted these swords and began to make changes to better suit their needs.

Thus the Mainz-Fulham gladii came to be. It was their first attempts at making this devastatingly destructive sword the perfect sword for their use so they pretty much ended up retaining the shape (wasp-waisted) and only really making it shorter - mainly used to get through chainmail

Then the Pompeii version comes along with new parallel sides and a shorter tip - along with also making the whole sword smaller once again - mainly used to get through plate armor

This sword would then last the Roman legionary and auxiliary infantry until 2nd century A.D. when they are replaced with the spatha

But in the end this sword served the Roman Empire for more than three centuries, in both their Republic and Imperial times - that’s pretty damn impressive

Fighting Tactics

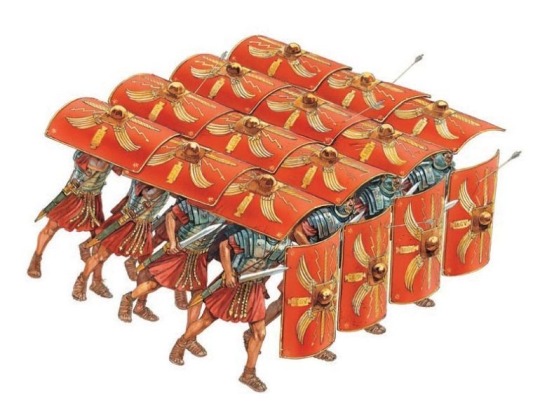

The Romans are pretty iconic for their tight formations and their Scutum shields

They also carried three different types weapons with them - couple of spears/javelins, a short sword, and a dagger. Obviously we are going to focus on the short sword

Soldiers actually wore their swords on their right side instead of their left because they were in such tight formation they didn’t have room to draw it across their body

With the exception for a Roman Centurion - who were commanders of a unit of about 100 soldiers and 60 of these guys(and their men) made up a Legion - as they wore their swords on the left

Now for what made the gladius so useful to the Romans was that it is mainly a thrusting sword - quick and efficient stabbing - which worked best with their formation but because it was also a double-edged sword it was great at cutting too if their formation ever broke

What they would do is while they were in their formations and trying to advance on the battleground they would take their sword and thrust it beside or above the shield - if they hit their target it more than likely resulted in a fatal injury. Though they weren’t above cutting their opponents at the knees - quite literally because if the opportunity arose they would lift their shields above them and slash at their knees.

It was all a very efficient way of fighting that served them well

obviously this is a very condensed version of a lot of history but it is the Human history behind Aziraphale sword

(and yes this is the type of sword the Roman soldiers have on them at Jesus’s crucifixion)

#quite literally just the history behind the sword#nothing else#good omens#good omens 2#aziraphale#aziraphale’s sword#good omens meta

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

The trope of the bigger guy being younger and shy despite looking really rugged and masculine, also very inexperienced and also the one who needs to get railed by a smaller, very feminine (hopefully trans) guy is so good.. we need more himmedoms.. my carthaginian empire whew

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Tanit

I recently posted about how people should be looking more into other gods outside of the Greco-Roman pantheons. If you follow me for quite some times, you will also have noted I posted a bunch of loose translation from the French Dictionary of literary myths (which is truly a great reference). Well, I wanted to share with you today a loose translation – well, more of an info-mining at this point – of an article about a goddess that people often ignore the existence of, despite being located right next to Ancient Greece and Rome, and being involved in the history of the Roman Empire. And this goddess is Tanit.

Written by Ildiko Lorinszky, the article is organized in two – at first it takes a look and analysis at the mythological Tanit, at who and what she likely was, how her cult was organized all that. The second part, since it is a Dictionary of LITERARY myths, takes a look at the most prominent and famous depiction of Tanit in French literature – that is to say Flaubert’s famous Salammbô. (If you recalled, a long time ago I posted about how a journalist theorized in an article how Flaubert’s Salammbô was basically an “epic fantasy” novel a la Moorcock or Tolkien long before “fantasy” was even a genre)

Part 1: Tanit in mythology and archeology

Tanit was the patron-goddess of the city of Carthage. Considered to be one of the avatars o the Phoenician goddess Astarte, Tanit’s title, as found on several Punic engravings, was “The Face of Baal” – a qualification very close to how Astarte was called in Sidon and Ugarit “The Name of Baal”. These titles seem to indicate that these two goddesses acted as mediators or intermediaries between humanity and Baal.

Tanit is as such associated with Baal, the vegetation god, but sometimes she is his wife, other times she is simply his paredra (companion/female counterpart). She seems to be the female power accompanying the personification of masculinity that is Baal, and as such their relationship can evoke the one between Isis and Osiris: the youthful sap of the lunar goddess regularly regenerates the power of the god. This “nursing” or “nourishing” function of Tanit seems to have been highlighted by the title she received during the Roman era: the Ops, or the Nutrix, the “Nurse of Saturn”. Goddess of the strengthened earth, Tanit is deeply tied to agrarian rituals: her hierogamy with Baal reproduces in heaven the birth of seeds on earth. Within the sanctuaries of Tanit, men and women devoted to the goddess practiced a sacred prostitution in order to favorize the fecundity of nature. The women tied to the temple were called “nubile girls”, while the men working there were called “dogs” to highlight how completely enslaved they were to the goddess. We know that the prostitutes of both sexes brought important incomes to the temple/

The etymology of Tanit (whose name can also be called Tannit or Tinnit) is obscure. The most probable hypothesis is that the Phoenico-Punic theonym “Tnt” is tied to the verb “tny”, which was used in the Bible to mean “lamenting”, “wailing”, “crying”. According to this interpretation, the “tannît” is originally a “crier”, a “wailer”, and the full name of Tanit means “She who cries before Baal”. As such, the Carthaginian goddess might come from a same tradition as the “Venus lugens”.

According to some mythographers, Tanit (or Astarte) was the supreme goddess of Carthage, and might have been identical to the figures of Dido and Elissa. As in, Dido was in truth the celestial goddess, considered as the founder of the city and its first queen. According to this hypothesis, the suicide of Dido on a pyre was a pure invention of Virgil, who took this motif from various celebrations hosted at Carthage. During these feasts-days, images and depictions of the goddess were burned The word Anna would simply mean “clement”, “mild”, “merciful” – the famous Anna, sister of Dido, is thought to have been another Punic goddess, whose cult was brought from Carthage to Rome, and who there was confused with the roman Anna Perenna, a goddess similar to Venus. Varro claimed that it was not Dido that burned on the pyre, but Anna, and according to this angle, Anna appears as a double of Dido – and like her, she would be another manifestation of the goddess Tanit. Anna’s very name reminds of the name “Nanaia”/”Aine”, which was a title given to Mylitta, yet another manifestation of Tanit.

The sign known as the “sign” or “symbol of Tanit” seems to be a simplified depiction of the goddess with her arms open: it is a triangle (reduced to a trapezoid as the top of the triangle is cut) with an horizontal line at its top, an a disc above the horizontal line. This symbol appears throughout the Punic world on monuments, steles, ceramics and clay figurines.

Part 2: The literary Tanit of Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert’s novel Salammbô is probably where the goddess reappears with the most splendor in literature. While her essence is shown being omnipresent throughout the Punic world, Tanit, as the soul of the city, truly dwells within the town’s sanctuary, which keeps her sacred cloak. The veil of the goddess, desired by many, stolen then regained throughout the plot, plays a key role within the structure of this very enigmatic text, which presents itself as a “veiled narrative”.

The town and its lands are filled with the soul of the “Carthaginian Venus”. The countryside, for example, is filled with an erotic subtext, sometimes seducing, sometimes frightening – reflecting the ambiguity of the goddess. The landscape is all curves, softness, roundness, evoking the shapes of a female body – and the architecture of both the city-buildings and countryside-buildings are described in carnal ways. Within Salammbô, Flaubert describes a world where the spirit and the flesh are intertwined – the female world of Carthage is oppressed by an aura mixing lust with mysticism; and through the erotic nature creeps both a frightening sacred and an attractive morbidity. For death and destruction is coming upon Carthage.

The contradictory nature of the goddess appears as early as the very first scene of the novel, when the gardens of Hamilcar are described. The novel opens on a life-filled landscape: the gardens of the palace are a true Land of Eden, with an abundant vegetation filled with fertility symbols. The plants that are listed are not mere exotic ornaments: they all bear symbolic and mythological connotations. The fig-tree, symbol of abundance and fecundity ; the sycamore, “living body of Hathor”, the tree of the Egyptian moon-goddess ; the grenade, symbol of fertility due to its multiple seeds ; the pine tree, linked to Attis the lover of Cybele ; the cypress, Artemis’ tree ; the lily, which whose perfume was said to be an aphrodisiac ; the vine-grapes and the rose… All those plants are linked to the moon, that the Carthaginian religion associated with Tanit. Most of these symbols, however, have a macabre touch reflecting the dark side of the goddess. The cypress, the “tree of life”, is also a funeral tree linked to the underworld ; the coral is said to be the same red as blood, and was supposedly born from the blood-drops of Medusa ; the lily symbolizes temptation and the unavoidable attraction of the world of the dead ; the fig-tree just like the grenade have a negative side tied to sterility… The flora of this passage, mixing benevolent and malevolent attributes, already depict a world of coexisting and yet opposed principles: fertility cannot exist without sterility, and death is always followed by a renewal. The garden’s description introduces in the text the very cycles of nature, while also bringing up the first signs of the ambivalence that dominates the story.

The same union of opposites is found within the mysterious persona of Tanit. The prayer of Salammbô (which was designed to evoke Lucius’ lamentations to Isis within Apuleius’ Metamorphosis) first describes a benevolent goddess of the moon, who fecundates the world : “How you turn, slowly, supported by the impalpable ether! It polishes itself around you, and it is the movement of your agitation that distributes the winds and the fecund dews. It is as you grow and decrease that the eyes of the cats and the spots of the panthers lengthen or shrink. The wives scream your name in the pains of labor! You inflate the sea-shells! You make the wines boil! […] And all seeds, o goddess, ferment within the dark depths of your humidity.” As a goddess presiding to the process of fermentation, Tanit is also tied to the principle of death – because it is her that makes corpses rot.

The Carthaginian Venus appears sometimes as an hermaphrodite divinity, but with a prevalence and dominance of her feminine aspect. Other times, she appears as just one of two distinct divinity, the female manifestation in couple with a male principle. Tanit synthetizes within her the main aspects of all the great moon-goddesses: Hathor, Ishtar, Isis, Astarte, Anaitis... All are supposed to have an omnipotence when it comes to the vegetal life. Mistress of the elements, Tanit can be linked to the Mother-Earth : for the character of Salammbô, the cloak of the goddess will appear as the veil of nature. The daughter of Hamilcar is linked in a quite mysterious way to Tanit – for she is both a frightened follower of the goddess, and the deity’s incarnation. Described as “pale” and “light” as the moon, she is said to be influenced by the celestial body: in the third chapter, it is explained that Salammbô weakened every time the moon waned, and that while she was languishing during the day, she strengthened herself by nightfall – with an additional mention that she almost died during an eclipse. Flaubert ties together his heroine’s traits with the very name “Salammbô”, which is a reminiscence of the funeral love of Astarte: “Astarte cries for Adonis, an immense grief weighs upon her. She searches. Salmmbô has a vague and mournful love”. According to Michelet’s explanations, “Salambo”, the “love name” of Astarte, is meant to evoke a “mad, dismal and furious flute, which was played during burials”.

As a character embodying Tanit, Salammbô is associated with the two animals that were sacred to the goddess: the holy fishes, and the python snake, also called “the house-spirit”. Upon the “day of the vengeance”, when Mâtho, the scape-goat, is charged with all the crimes of the mercenaries, she appears under the identity of Dercéto, the “fish-woman”. The very detailed costumes of Salammbô contain motifs borrowed to other goddesses that are avatars of Tanit. By using other goddesses, Flaubert widens the range of shapes the lunar goddess can appear with, while also bringing several mythical tales, whose scattered fragments infiltrate themselves within the novel. When she welcomes her father, Salammbô wears around her neck “two small quadrangular plates of gold depicting a woman between two lions ; and her costume reproduced fully the outfit of the goddess”. The goddess depicted here is Cybele, the passionate lover of Attis, the young Phrygian shepherd. This love story that ends in mutilations bears several analogies with the fatal love between Salammbô and the Lybian leader. And the motif of the mutilation is one of the key-images of the novel.

A fish-woman, like Dercéto, Salmmbô is also a dove-woman, reminding of Semiramis ; but more so, she is a snake-woman, linked mysteriously to the python. Before uniting herself with Mâtho (who is identified to Moloch), Salammbô unites herself with the snake that incarnates the lunar goddess in her hermaphroditic shape. It is the python that initiates Salammbô to the mysteries, revealing to Hamilcar’s daughter the unbreakable bond between eroticism and holiness. In the first drafts of the novel, Salammbô was a priestess of Tanit, but in the final story, Flaubert chose to have her father denying her access to the priesthood. So, she rather becomes a priestess under Mathô’s tent: using the zaïmph, she practices a sacred prostitution. The union of Hamilcar’s daughter and of the leader of the mercenaries reproduces the hierogamy of Tanit and Moloch.

Salammbô, confused with Tanit, is also victim of the jealous Rabbet. Obsessed with discovering the face of the goddess hidden under the veil, she joins the ranks of all those female characters who curiosity leads to the transgression of a divine rule (Eve, Pandora, Psyche, Semele). And, in a way, the story of Mathô and Salammbô reproduces this same story: the desire to see, the desire for knowledge, always leads to an ineluctable death.

#tanit#astarte#punic goddess#carthaginian goddess#carthage#baal#flaubert#salammbô#salammbo#french literature#punic mythology#carthaginian mythology

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

I drew a scene of my Roman Empire novel I’m working on! It’s the story of a girl named Helia who wants to take revenge on Emperor Nero for executing her father. She gets into a lot of adventures… accidentally stuck on a galley warship, sold to the Carthaginian mines, sneaking disguised into the Emperor’s palace, ends up as a gladiatrix for a while, etc…. Helia’s brother Mene, however, is an imperial guard who’s loyal to the Emperor no matter what!

I have so much stuff planned out that I’ll keep posting, look forward to to it :>

#ancient rome#roman empire#oc art#character art#character design#my ocs#oc#ocs#fanart#emperor nero#rome#gladiator au#gladiator#graphic novel#novel writing#my novel#colosseum#roman colosseum#anime art#digital art

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

A quick question flame, can MC recreates this in the future?

https://youtube.com/shorts/w67bLjsn8RI?si=i4viU-v6XETKlgmx

The ask links to a youtube short talking about the Battle of Cannae, and yes. Like literally from the day I created Kingdoms and Empires, i have wanted to recreate that battle with the MC. In fact, that old ask in regards to Aurelian being excited for battle, and MC telling him that this will be a day that shall live forever in infamy and to not be excited and take it seriously, was created with the Battle of Cannae in mind.

The two armies met near the city of Cannae in southeastern Italy on the 2nd of August, 216 BC. The battle unfolded in three stages.

In the first stage, the Roman infantry, as Hannibal predicted, charged directly at the Carthaginian center.

The hand-to-hand combat was fierce, and Hannibal encouraged his men to hold the line as long as they could.

As the Roman infantry kept pushing forward, Hannibal slowly let his line be pushed backwards, which meant that the bulging centre of the crescent gradually inverted, and the edges of the Carthaginian line were now located on the sides of the massed Roman formation.

In the second stage, while the infantry was fighting in the middle, the Carthaginian cavalry on the wings rode past the infantry and attacked the Roman cavalry that was waiting behind their troops. After a short clash, the Roman cavalry fled in defeat.

In the third stage, the Carthaginian cavalry that had driven the Roman cavalry away, returned to the centre of the battlefield and attacked the Roman soldiers from behind.

The Romans were now surrounded on all four sides: the Carthaginian infantry in front and on the flanks, and cavalry at the rear.

With no way to escape and surrounded on all sides, the battle then turned into a systematic slaughter of the trapped Roman army.

The Romans were unable to escape, and more than 44,000 men were killed. Hannibal only lost 6000 in comparison.

Among the dead was the consul, Lucius Aemilius Paulus. This was one of the most crushing defeats in Roman history.

It was so crushing, that the Carthaginian soldiers who slaughtered the Romans couldn't ungrip their weapons. Imagine how many they had to kill for the body to refuse the grip it had on the handle?

But just as badly as I want to do the Battle of Cannae, I also want our MC to recreate...THIS

Im just so much of a fucking fanboy for Hannibal Barca!!!!

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Progressing through Orson Scott Card's Ender Saga. Currently up to "Children Of The Mind", and good fucking lord these chapters with Wang-mu and 'Peter' are such an utterly fucking atrocious trainwreck.

Can anyone in the Ender's Game fandom explain this to me please??

Why are these characters in the Sixth fucking Millennium A.D. talking about "Asians", "Europeans", and "Americans"; and their identities thereof, as if those are even REMOTELY meaningful categories of culture to the peoples of a humanity that have been spreading out into and colonising outer space for over three thousand years?????

Like, right now where I'm up to, Wang-mu and 'Peter' are having their first little conversation with Ainmaina Hikari, and Wang-mu is breezily bullshitting about Ancient Egypt/China/Mesopotamia or whatever

And, like, those ancient cultures are as far-removed from me, the reader, as China/Japan/America are from Wang-mu/Hikari/'Peter'!

If you were to squint hard enough, yeah, it could be said that my distant ancestors came from the Roman Empire, but, fuck no there is no way in heaven or hell that the culture of those 3500-years-ago ancestors and their neighbourly relations with other cultures and peoples has ANY kind of bearing on my life or cultural outlooks.

Like, I'm not gunna give the side-eye to some random stranger I meet whose culture mores seem different to mine and start waxing poetic about "oh he's just like that because he's a Carthaginian. 🙄😒 You all know what Carthaginians are like amirite?? "

(I guess 'Peter' is technically an American—or a 'cloned' caricature of one, at least—so he gets a pass on this)

The Doyleist explanation is that Orson Scott Card simply didn't have the sci-fi chops to imbue his creation with coherence; he's just trying to tell a story here and doesn't have the Tolkienian level of galaxy-brain required to convincingly pull off the 3000+ years of history and sociology experienced by his humanity across its umpteen number of colony worlds, so he's just sticking to what he knew and is hand-waving away the shockingly breathtaking levels of cultural stagnation his humanity has wallowed in.

But what's the Watsonian explanation for that cultural stagnation?? Is there a Watsonian explanation??

(also, what's with Miro's latent homophobia?? Is he Like That because of Card's own intense homophobia shining through, or is it simply because Miro grew up on The Catholic Planet?)

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Warship’s Bronze Battering Ram Sunk During a Battle Between Rome and Carthage Found

Found near the Aegadian Islands, just west of Sicily, the bronze rostrum played a role in the last battle of the First Punic War, which ended in 241 B.C.E.

In 241 B.C.E., two empires faced off in a naval clash off the coast of Sicily. By then, Rome and Carthage had been fighting for more than two decades. Rome’s victory in the skirmish, officially called the Battle of the Aegates, brought an end to the First Punic War, the initial conflict in a series of wars between the two ancient powers.

Now, explorers have recovered a piece of that final battle: the bronze battering ram of an ancient warship. According to a statement from Sicily’s Superintendence of the Sea, the ram was found on the seafloor off the western coast of the Mediterranean island, at a depth of around 260 feet. To retrieve the artifact, the team used deep-water submarines from the Society for Documentation of Submerged Sites (SDSS) and the oceanographic research vessel Hercules.

The seabed off the Aegadian Islands “is always a valuable source of information to add further knowledge about the naval battle between the Roman and Carthaginian fleets,” Regional Councilor for Cultural Heritage Francesco Paolo Scarpinato tells Finestre sull’Arte. He adds that the find is yet another confirmation of the work of the late archaeologist Sebastiano Tusa, who spearheaded exploration of the seabed as the site of the 241 battle after a separate ram, also known as a rostrum, was first found there in the early 2000s. In the two decades since, researchers have recovered at least 25 rams from the seabed.

At the time of the Battle of the Aegates, Rome and Carthage had been at war for 23 years, fighting for dominance in the Mediterranean. As the Greek historian Polybius later wrote, the Romans sank 50 Carthaginian ships and captured another 70 along with their crews, taking nearly 10,000 sailors prisoner during the naval battle. Rome forced Carthage to surrender. But the fragile peace was short-lived: Over the next century, Rome would go on to fight a second and third war against the Punic people, winning each time.

“It was very costly, both in terms of human life and economically,” Francesca Oliveri, an archaeologist at the superintendence, told BBC News’ Alessia Franco and David Robson in 2022. “In the last phase, Rome even had to ask for a loan from the most well-to-do families to arm the fleet and build new boats.”

The recently discovered ram has been brought to Favignana, one of the Aegadian Islands, for further study. Though its features are difficult to make out because the object is covered in marine life, researchers have been able to discern a decoration on its front: a relief depicting a Montefortino-style Roman helmet decorated with three feathers.

The battering ram adds to the wealth of war relics found on the seabed, which also include 30 Roman soldiers’ Montefortino helmets, two swords, coins and many clay amphorae (large storage jars).

According to the SDSS, rams were the most important naval weapons of their time. They were placed on the bows of warships at water level so that sailors could crash their boats into enemy vessels, damaging and sinking them. The plethora of rams scattered on the seabed are testaments to the weapons’ effectiveness in ancient battle.

“We are finding so many things that help to illustrate a little better the world of the third century [B.C.E.],” Oliveri told BBC News in 2022. “It’s the first site of a naval battle, in the world, that has been scientifically documented like this, and it will continue to be documented—because the area of interest is very large. … It will take at least another 20 years to explore it fully.”

By Sonja Anderson.

#Ancient Warship’s Bronze Battering Ram Sunk During a Battle Between Rome and Carthage Found#roman rostrum#bronze#bronze rostrum#bronze battering ram#Battle of the Aegates#First Punic War#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do u have any headcanons about Rome or the other ancients

i do! here are some of them:

Rome is the Italybros' father, not their grandfather. Children are sometimes bittersweet omens for nations; your beginning is a harbinger of someone else's end.

When he was still a republic, the Battle of Cannae during the Punic Wars against Carthage was the moment Rome most feared dying for real. As the Carthaginian general Hannibal proclaimed; "I swear to arrest the destiny of Rome with fire and steel"—that put some real fear into young Rome's heart.

Persia (aka the Achaemenid Empire) is at least 3,000 years old—they and modern Iran are the same person. Another ye olde helltalia, like China.

Germania's real name is not Germania: he is one of the many Germanic nations that existed; as historically, Tacitus' concept of "Germania" is more of a Roman construction—they didn't see themselves as a single unified "Germanic" cultural or political entity. So, Tacitus' Germania? Much like Herodotus: father of history, father of lies, perhaps...

Yao's earliest memory is of walking along the Yellow River. It's one thing he has in common with many other ancient nations; rivers feature heavily in their earliest sense of being: Rome (the Tiber), Sumer (the Tigris and the Euphrates), Ancient Egypt (the Nile) and Olmec (the Coatzacoalcos, in modern Mexico) being some examples. Yao thinks of the Yellow River as being both life and death; the fertile silt on the banks that would be the lifeblood of his civilisation, but also the source of devastating floods throughout his history.

Yao rather respected Rome, Persia/Iran and India a lot more than his other neighbours; Rome being called da qin(大秦)or "great qin". Almost a sort of "oh, there's another empire at the opposite end of the (then) known world just like me." Bit of a difference from how at various points, Yong-soo and Kiku got much less flattering names. Today, many things have crumbled under the sword of time, but there's still Roman glassware he has from that long-gone time of the Silk Road that linked Rome and China—as well as all the other cultures in between—together.

#hetalia#hetalia headcanons#hws rome#hws china#hws carthage#hws iran#hws persia#hws germania#hws india#hws ancient egypt#hws olmec#hws sumer

139 notes

·

View notes

Photo

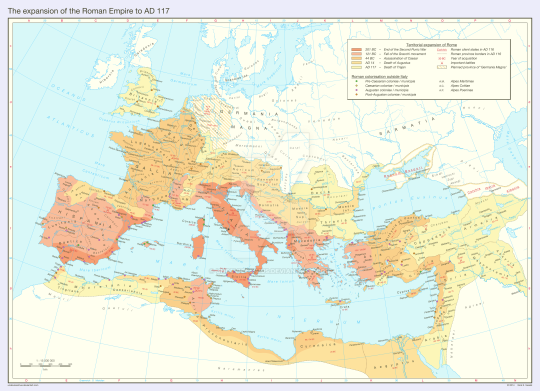

The expansion of the Roman Empire to AD 117.

by Undevicesimus

From its humble origins as a group of villages on the Tiber in the plains of Latium, Rome came to control one of the greatest empires in history, reaching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Tigris and from the North Sea to the Sahara Desert. Its extensive legacy continues to serve as a lowest common denominator not only for the nations and peoples within its erstwhile borders, but much of the modern world at large. Roman law is the foundation for present-day legal systems across the globe, the Latin language survives in the Romance languages spoken on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond, Roman settlements developed into some of Europe’s most important cities and stood model for many others, Roman architecture left some of history’s finest manmade landmarks, Christianity – the Roman state religion from AD 395 – remains the world’s dominant faith and Rome continues to feature prominently in Western popular culture… Rome rose in a geographically favourable location: on the left bank of the Tiber, not too far from the sea but far enough inland to be able to control important trade routes in central Italy: southwest from the Apennines alongside the Tiber, and from Etruria southeast into Latium and Campania. In later ages, the Romans always had much to tell about the founding and early history of their city: tales about the twin brothers Romulus and Remus being raised by a she-wolf, the founding of Rome by Romulus on 21 April 753 BC and the reign of the Seven Kings (of which Romulus was the first). According to Roman accounts, the last King of Rome – Tarquinius Superbus – was expelled in 510 BC, after which the Roman aristocracy established a republic ruled by two annually elected magistrates (Latin: pl. consulis) with the support of the Senate (Latin: senatus), a council made up of the leaders of the most prominent Roman families. Often at odds with their neighbours, the Romans considered military service one of the greatest contributions common people could make to the state and the easiest way for a consul to gain both power and prestige by protecting the republic. The Romans booked their first major triumph by conquering the Etruscan city Veii in 396 BC and went on to defeat most of the Latin cities in central Italy by 338 BC, despite the Celtic sack of Rome in 387 BC. Throughout the second half of the fourth century BC, the republic expanded in two different ways: direct annexation of enemy territory and the creation of a complex system of alliances with the peoples and cities of Italy. Shortly after 300 BC, nearly all the peoples of Italy united to stop Roman expansion once and for all – among them the Samnites, Umbrians, Etruscans and Celts. Rome obliterated the coalition in the decisive Battle of Sentinum (295 BC) and thus became the strongest power in Italy. By 264 BC, Rome controlled the Italian peninsula up to the Po Valley and was powerful enough to challenge its principal rival in the western Mediterranean: Carthage. The First Punic War began when the Italic people of Messana called for Roman help against both Carthage and the Greeks of Syracuse, a request which was accepted surprisingly quickly. The Romans allied with Syracuse, conquered most of Sicily and narrowly defeated the Carthaginian navy at Mylae in 264 BC and Ecnomus in 256 BC – the largest naval battles of Antiquity. Roman fleets gained a decisive victory off the Aegates Islands in 241 BC, ending the war and forcing the Carthaginians to abandon Sicily. Taking advantage of Carthage’s internal troubles, Rome seized Sardinia and Corsica in 238 BC. Rome’s frustration at Carthage’s resurgence and subsequent conquests in Spain sparked the Second Punic War, in which the Carthaginian commander Hannibal crossed the Alps and invaded the Italian peninsula. The Romans suffered massive defeats at the Trebia in 218 BC, Lake Trasimene in 217 BC and most famously at Cannae in 216 BC where over 50,000 Romans were slain – the largest military loss in one day in any army until the First World War. However, Hannibal failed to press his advantage and continued an increasingly pointless campaign in Italy while the Romans conquered the Carthaginian territory in Spain and ultimately brought the war to Africa. Hannibal’s army made it back home but was decisively defeated by Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, securing Rome’s hard-fought victory in arguably the most important war in Roman history. Firmly in command of much of the western Mediterranean, Rome turned its attention eastwards to Greece. Less than fifty years after the Second Punic War, Rome had crushed the Macedonian kingdom – an erstwhile ally of Hannibal – and formally annexed the Greek city-states after the destruction of Corinth in 146 BC. That very same year, the Romans finished off the helpless Carthaginians in much the same way, burning the city of Carthage to the ground and annexing its remaining territory into the new province of Africa. With Carthage, Macedon and the Greek cities out of the way, Rome was free to deal with the Hellenic kingdoms in Asia Minor and the Middle East, the remnants of Alexander the Great’s empire. In 133 BC, Attalus III of Pergamum left his realm to Rome by testament, gaining the Romans their first foothold in Asia. As the Romans expanded their borders, the unrest back in Rome and Italy increased accordingly. The wars against Carthage and the Greeks had seriously crippled the Roman peasants whom abandoned their home to campaign for years in distant lands, only to come back and find their farmland turned into a wilderness. Many peasants were thus forced to sell their land at a ridiculously low price, causing the emergence of an impoverished proletarian mass in Rome and an agricultural elite in control of vast swathes of countryside. This in turn disrupted army recruitment, which heavily relied on middle class peasants who were able to afford their own arms and armour. Two possible solutions could remove this problem: a redistribution of the land so that the peasantry remained wealthy and large enough to be able to afford their military equipment and serve in the army, or else allowing the proletarian masses to enter military service and make the army into a professional body. However, both options would threaten the position of the Roman Senate: a powerful peasantry could press calls for more political influence and a professional army would bind soldiers’ loyalty to their commander instead of the Senate. The senatorial elite thus stubbornly clung to the existing institutions which were undermining the republic they wanted to uphold. More importantly, the Senate’s attitude and increasingly shaky position, in addition to the growing internal tensions, created a perfect climate for overly ambitious commanders seeking to turn military prestige gained abroad into political power back home. Roman successes on the frontline nevertheless continued: Pergamum was turned into the province of Asia in 129 BC, Roman forces sacked the city of Numantia in Spain that same year, the Balearic Islands were conquered in 123 BC, southern Gaul became the new province of Gallia Narbonensis in 121 BC and the Berber kingdom of Numidia was dealt a defeat in the Jughurtine War (112 – 106 BC). The latter conflict provided Gaius Marius the opportunity to reform his army without senatorial approval, allowing proletarians to enlist and creating a force of professional soldiers who were loyal to him before the Senate. Marius’ legions proved their efficiency at the Battles of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC and Vercellae in 101 BC, virtually annihilating the migratory invasions of the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones. Marius subsequently used his power and prestige to secure a land distribution for his victorious forces, thus setting a precedent: any successful commander with an army behind him could now manipulate the political theatre back in Rome. Marius was succeeded as Rome’s leading commander by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who gained renown when Rome’s Italic allies – fed up with their unequal status – attempted to renounce their allegiance. Rome narrowly won the ensuing Social War (91 – 88 BC) and granted the Italic peoples full Roman citizenship. Sulla left for the east in 86 BC, where he drove back King Mithridates of Pontus, whom had sought to benefit from the Social War by invading Roman territories in Asia and Greece. Sulla marched on Rome itself in 82 BC, executed many of his political enemies in a bloody purge and passed reforms to strengthen the Senate before voluntarily stepping down in 79 BC. Sulla’s retirement and death one year later allowed his general Pompey to begin his own rise to prominence. Following his victory in the Sertorian War in 72 BC, Pompey eradicated piracy in the Mediterranean Sea in 67 BC and led a campaign against Rome’s remaining eastern enemies in 66 BC. Pompey drove Mithridates of Pontus to flight, annexed Pontic lands into the new province of Bithynia et Pontus and created the province of Cilicia in southern Asia Minor. He proceeded to destroy the crumbling Seleucid Empire and turned it into the new province of Syria in 64 BC, causing Armenia to surrender and become a vassal of Rome. Pompey’s legions then advanced south, took Jerusalem and turned the Hasmonean Kingdom in Judea into a Roman vassal as well. Upon his triumphant return to Rome in 61 BC, Pompey made the significant mistake of disbanding his army with the promise of a land distribution, which was refused by the Senate in an attempt to isolate him. Pompey then concluded a political alliance with the rich Marcus Licinius Crassus and a young, ambitious politician: Gaius Julius Caesar. The purpose of this political alliance – known in later times as the First Triumvirate – was to get Caesar elected as consul in 59 BC, so that he could arrange the land distribution for Pompey’s veterans. In return, Pompey would use his influence to make Caesar proconsul and thus give him the chance to levy his own legions and become a man of power in the Roman Republic. Crassus, the richest man in Rome, funded the election campaign and easily got Caesar elected as consul, after which Caesar secured Pompey’s land distribution. Everything went according to plan and Caesar was made proconsul of Gaul for five years, starting in 58 BC. In the following years, Caesar and his legions systematically conquered all of Gaul in a war which has been immortalised in the accounts of Caesar himself (‘Commentarii De Bello Gallico’). Despite fierce resistance and massive revolts led by the Gallic warlord Vercingetorix, the Gallic tribes proved unable to inflict a decisive defeat on the Romans and were all subdued or annihilated by 51 BC, leaving Caesar’s power and prestige at unprecedented heights. With Crassus having fallen at the Battle of Carrhae against the Parthians in 53 BC, Pompey was left to try and mediate between Caesar and the radicalised Roman proletariat on one side and the politically hard-pressed Senate on the other. However, Pompey had once been where Caesar was now – the champion of Rome – and ultimately chose to side with the Senate, realising his own greatness had become overshadowed by Caesar’s staggering military successes and popularity among the masses. When Caesar’s term as proconsul ended, the Senate demanded that he step down, disband his armies and return to Rome as a mere citizen. Though it was tradition for a Roman commander to do so, rendering Caesar theoretically immune from any senatorial prosecution, the existing political situation made such demands hard to meet. Caesar instead offered the Senate to extend his term as proconsul and leave him in command of two legions until he could be legally elected as consul again. When the Senate refused, Caesar responded by crossing the Rubicon – the northern border of Roman Italy which no Roman commander should cross with an army – and marched on Rome itself in 49 BC. Pompey and most of the senators fled to Dyrrhachium in Greece and assembled their forces while Caesar turned around and conducted a lightning campaign in Spain, defeating the legions loyal to Pompey at the Battle of Ilerda. Caesar crossed the Adriatic Sea in 48 BC, narrowly escaping defeat by Pompey at Dyrrhachium and retreating south. Pompey clumsily failed to press his advantage and his forces were in turn decisively defeated by Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus on 6 June 48 BC. Pompey fled to Egypt in hopes of being granted sanctuary by the young king Ptolemy XIII, who instead had him assassinated in an attempt at pleasing Caesar, who was in pursuit. Ptolemy XIII was driven from power in favour of his older sister Cleopatra VII, with whom Caesar had a brief romance and his only known son, Caesarion. In the spring and summer of 47 BC, another lightning campaign was launched northwards through Syria and Cappadocia into Pontus, securing Caesar’s hold on Rome’s eastern reaches and decisively defeating the forces of Pharnaces II of Pontus, who had attempted to profit from Rome’s internal strife. Caesar invaded Africa in 46 BC and cleared Pompeian forces from the region at the Battles of Ruspina and Thapsus before returning to Spain and defeating the last resistance at the Battle of Munda in 45 BC. Caesar subsequently began transforming the Roman government from a republican one meant for a city-state to an imperial one meant for an empire. Major reforms were required to achieve this, many of which would be opposed by Caesar’s political enemies. This was a problem because several of these people enjoyed significant political influence and popular support (cf. Cicero) and while none of them could really challenge Caesar individually and publicly, collectively and secretly they could be a serious threat. To render his enemies politically impotent, Caesar consolidated his popularity among the Roman masses by passing reforms beneficial to the proletariat and enlarging the Senate to ensure his supporters had the upper hand. He then manipulated the Senate into granting him a number of legislative powers, most prominently the office of dictator for ten years, soon changed to dictator perpetuus. Though widely welcomed by the masses, Caesar’s reforms and legislative powers dismayed his political opponents, whom assembled a conspiracy to murder him and ‘liberate’ Rome. The conspirators, of whom Brutus and Cassius are the most famous, were successful and Caesar was brutally stabbed to death on 15 March 44 BC. Caesar’s death left a power vacuum which plunged the Roman world into yet another civil war. In his testament, Caesar adopted as his sole heir his grandnephew Gaius Octavius, henceforth known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian, in English). Despite being only eighteen, Octavian quickly secured the support of Caesar’s legions and forced the Senate to grant him several legislative powers, including the consulship. In 43 BC, Octavian established a military dictatorship known as the Second Triumvirate with Caesar’s former generals Mark Antony and Marcus Lepidus. Caesar’s assassins had meanwhile fled to the eastern provinces, where they assembled forces of their own and subsequently moved into Greece. Octavian and Antony in turn invaded Greece in 42 BC and defeated them at the Battles of Philippi. Octavian, Antony and Lepidus then divided the Roman world between them: Octavian would rule the west, Antony the east and Lepidus the south with Italy as a joint-ruled territory. However, Octavian soon proved himself a brilliant politician and strategist by quickly consolidating his hold on both the western provinces and Italy, smashing the Sicilian Revolt of Sextus Pompey (son of) in 36 BC and ousting Lepidus from the Triumvirate that same year. Meanwhile, Antony consolidated his position in the east but made the fatal mistake of becoming the lover of Cleopatra VII. In 32 BC, Octavian manipulated the Senate into a declaration of war upon Cleopatra’s realm, correctly expecting Antony would come to her aid. The two sides battled at Actium on 2 September 31 BC, resulting in a crushing victory for Octavian, despite Antony and Cleopatra escaping back to Egypt. Octavian crossed into Asia the following year and marched through Asia Minor, Syria and Judea into Egypt, subjugating the eastern territories along the way. On 1 August 30 BC, the forces of Octavian entered Alexandria. Both Antony and Cleopatra perished by their own hand, leaving Octavian as the undisputed master of the Roman world. Octavian assumed the title of Augustus in January 27 BC and officially restored the Roman Republic, although in reality he reduced it to little more than a facade for a new imperial regime. Thus began the era of the Principate, named after the constitutional framework which made Augustus and his successors princeps (first citizen), commonly referred to as ‘emperor’, and which would last approximately two centuries. Augustus nevertheless refrained from giving himself absolute power vested in a single title, instead subtly spreading imperial authority throughout the republican constitution while simultaneously relying on pure prestige. Thus he avoided stomping any senatorial toes too hard, remembering what had happened to Julius Caesar. Augustus and his successors drew most of their power from two republican offices. The title of tribunicia potestes ensured the emperor political immunity, veto rights in the Senate and the right to call meetings in both the Senate and the concilium plebis (people’s assembly). This gave the emperor the opportunity to present himself as the guardian of the empire and the Roman people, a significant ideological boost to his prestige. Secondly, the emperor held imperium proconsulare. Imperium implied the emperor’s governorship of the so-called imperial provinces, which were typically border provinces, provinces prone to revolt and/or exceptionally rich provinces. These provinces obviously required a major military presence, thereby securing the emperor’s command of most of the Roman legions. The title was proconsulare because the emperor enjoyed imperium even without being a consul. The emperor furthermore interfered in the affairs of the (non-imperial) senatorial provinces on a regular basis and gave literally every person in the empire the theoretical right to request his personal judgement in court cases. Roman religion was also brought under the emperor’s wings by means of him becoming pontifex maximus (supreme priest), a position of major ideological importance. On top of all this, the Senate frequently granted the emperor additional rights which enhanced his power even more: supervision over coinage, the right to declare war or conclude peace treaties, the right to grant Roman citizenship, control over Roman colonisation across the Mediterranean, etc. The emperor was thus the supreme administrator, commander, priest and judge of the empire – a de facto absolute ruler, but without actually being named as such. It is worth noting that Augustus and most of his immediate successors worked hard to play along in the empire’s republican theatre, which gradually faded as the centuries passed. The most important questions nonetheless remained the same for a long time after Augustus’ death in AD 14. Could the emperor keep himself in the Senate’s good graces by preserving the republican mask? Or did he choose an open conflict with the Senate by ruling all too autocratically? Even a de facto absolute ruler required the support and acceptance of the empire’s elite class, the lack of which could prove to be a serious obstacle to any imperial policies. The relationship between the emperor and the Senate was therefore of significant importance in maintaining the political work of Augustus, particularly under his immediate successors. The first four of these were Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero – the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Tiberius was chosen by Augustus as successor on account of his impressive military service and proved to be a capable (if gloomy) ruler, continuing along the political lines of Augustus and implementing financial policies which left the imperial treasuries in decent shape at his death in AD 37 and Caligula’s accession. Despite having suffered a harsh youth full of intrigues and plotting, Caligula quickly gained the respect of the Senate, the army and the people, making a hopeful entry into the Principate. Yet continuous personal setbacks turned Caligula bitter and autocratic, not to say tyrannical, causing him to hurl his imperial power head-first into the senatorial elite and any dissenting groups (most notably the Jews). After Caligula’s assassination in AD 41, the position of emperor fell to his uncle Claudius who, despite a strained relationship with the Senate, managed to play the republican charade well enough to implement further administrative reforms and successfully invade the British Isles to establish the province of Britannia from AD 43 onward. But the Roman drive for expansion had been somewhat tempered after Augustus’ consolidating conquests in Spain, along the Danube and in the east. The Romans had practically turned the Mediterranean Sea into their own internal sea (Mare Internum or Mare Nostrum) and thus switched to territorial consolidation rather than expansion. However, the former was still often accomplished by the latter as multiple vassal states (Judea, Cappadocia, Mauretania, Thrace etc.) were gradually annexed as new Roman provinces. Actual wars of aggression nevertheless ceased to be a main item on the Roman agenda and indeed, the policies of consolidation and pacification paved the way for a long period of internal peace and stability during the first and second centuries AD – the Pax Romana. This should not be idealised, though. On the local level, violence was often one of the few stable elements in the lives of the common people across the empire. Especially among the lowest ranks of society, crimes such as murder and thievery were the order of the day but were typically either ignored by the Roman authorities or answered with brute force. Moreover, the Romans focused on safeguarding cities and places of major strategic or economic importance and often cared little about maintaining order in the vast countryside. Unpleasant encounters with brigands, deserters or marauders were therefore likely for those who travelled long distances without an armed escort. At the empire’s frontiers, the Roman legions regularly fought skirmishes with their local enemies, most notably the Germanic tribes across the Rhine-Danube frontier and the Parthians across the Euphrates. Despite all this, the big picture of the Roman world in the first and second centuries AD is indeed one of lasting stability which could not be discredited so easily. The real threat to the Pax Romana existed not so much in local violence, shady neighbourhoods or frontier skirmishes but rather in the highest ranks of the imperial court. The lack of both dynastic and elective succession mechanisms had been the Principate’s weakest point from the outset and would be the cause of major internal turmoil on several occasions. Claudius’ successor Nero succeeded in provoking both the Senate and the army to such an extent that several provincial governors rose up in open revolt. The chaos surrounding Nero’s flight from Rome and death by his own hand plunged the empire into its first major succession crisis. If the emperor lost the respect and loyalty of both the Senate and the army, he could not choose a successor, giving senators and soldiers a free hand to appoint the persons they considered suitable to be the new emperor. This being the exact situation upon Nero’s death in AD 68, the result was nothing short of a new civil war. To further add to the catastrophe, the civil war of AD 68/69 (the Year of Four Emperors) allowed for two major uprisings to get out of hand – the Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine and the First Jewish-Roman War in Judea. Both of these were ultimately crushed with significant difficulties, especially in Judea where Jewish religious-nationalist sentiments capitalised on existing political and economic unrest. Though the Romans achieved victory with the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 and the expulsion of the Jews from the city, Judea would remain a hotbed for revolts until deep into the second century AD. The fact that major uprisings arose at the first sign of trouble within the empire might cause one to wonder about the true nature of the Pax Romana. Was it truly the strong internal stability it is popularly known to be? Or was it little more than a forced peace, continuously threatened by socio-economic and political discontent among the many different peoples under the Roman yoke? Though a bit of both, the answer definitely leans towards the former hypothesis. While the Pax Romana lasted, unrest within the empire remained limited to a few hotbeds with a history of resisting foreign conquerors. Besides the obvious example of the Jewish people in Judea, whose anti-Roman sentiments largely stemmed from their unique messianic doctrines, large-scale resistance against the Romans was scarce. It is true that the incorporation and Romanisation of unique societies near the empire’s northern frontiers led to severe socio-economic problems and subsequent uprisings, most notably Boudica’s Rebellion in Britain (AD 60 – 61) and the aforementioned Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that the Pax Romana was strong enough to outlast a few pockets of rebellion and even a major succession crisis like the one of AD 68/69. The Year of the Four Emperors ultimately brought to power Vespasian, founder of the Flavian dynasty (AD 69 – 96) and architect of an intensified pacification policy throughout the empire. These policies were fruitful and strengthened the constitutional position of the emperor, not in the least owing to the fact that Vespasian’s sons and successors Titus and Domitian were as capable as their father. However, their skills did not prevent Titus and especially Domitian from bickering with the senatorial elite over the increasingly obvious monarchical powers of the emperor. In the case of the all too authoritarian Domitian, the conflict escalated again and despite his competent (if ruthless) statesmanship, Domitian was murdered in AD 96. A new civil war was prevented by diplomatic means: Nerva emerged as an acceptable emperor to both the Senate and the army, especially when he adopted the popular Trajan as his son and heir. Thus began the reign of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty (AD 96 – 192). Having succeeded Nerva in AD 98, Trajan once more steered the empire onto the path of aggressive expansion, leading the Roman legions across the Danube to crush the Dacians and establish the rich province of Dacia in AD 106. Subsequently, the Romans seized the initiative in the east, drove back the Parthians and advanced all the way to the Persian Gulf (Sinus Persicus). Trajan annexed Armenia in AD 114 and turned the conquered Parthian lands into the new provinces of Mesopotamia and Assyria in AD 116. Trajan died less than a year later on 9 August AD 117, his staggering military successes having brought the Roman Empire to its greatest extent ever…

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Watson: Wisteria Lodge

Cultural Historical Note: Syncretic Afro-Carribean religions and spiritual traditions First caveat here is that I do not have expertise. I took a class once on African diaspora culture that briefly covered the many religious traditions that inspire depictions of Voodoo in the media. This is still more than Holmes and Watson had access to in the British Museum. In brief: African, mostly west African, religions came to the Americas when their practitioners were kidnapped during the slave trade, and changed and evolved as enslaved African communities encountered Catholicism and indigenous religious practices in and surrounding the Carribean. Practices associated with Vaudou, Santeria, Hoodoo, Vodun, and other diaspora religions have a long history of being misunderstood, misreported, and used for shock value in order to demonize people of African descent, or to tell a titillating story that also reinforces suspicion of such people, as is the case here. Remember folks, racism and stereotyping does not have to be intentional to be harmful!

Case and Themes: racism, exoticism, and religious slander. Warnings: Discussions of animal sacrifice, infanticide, and a lot of slander in the historical context of conflict between religions, and as excuses for colonialism. No more graphic than any case wrap up, but I get to use my unfinished classics degree here briefly.

Allegations within The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge that the practice of Voodoo includes human sacrifice and cannibalism must, of course, be taken with a whole cellar of salt, given the long history of accusing members of minority religions of taboo violence. When we examine any author's use of non-christian religion in their work (specifically when that author comes from a background of christian majority population and historical entanglement of christian religious institutions with the government of their home country) we have to remember that demonizing practitioners of other religions is one of the oldest tricks in the book. It's used both to provide excuses for violence against other communities, and to tell a scary adventure story.

Allegations within The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge that the practice of Voodoo includes human sacrifice and cannibalism must, of course, be taken with a whole cellar of salt, given the long history of accusing members of minority religions of taboo violence.

A modern audience is probably aware of the existence of Blood Libel, or a historical pattern of accusations against Jewish people of killing or planning to kill christian children, which then serve as excuses for violence against Jewish people. This is not unique to the the history of Christianity and Judaism - a pre-christian roman empire accused Carthaginians of widespread infanticide, for one example. In turn, there is modern debate about the true prevalence of infanticide by exposure, i.e. abandoning the baby outside somewhere, within the Roman Empire. (Archaeological evidence for infanticide in the ancient world is muddled at best, given that infant mortality in pre-antibiotic, pre-vaccine eras was just high overall, and burial customs for infants can be very different than the burials of an adult or an older child. There is also the fact that many ancient writings on morality and customs are written necessarily by the privileged few in any society; neither contempt for the poor, nor contempt for the ill and disabled, which are both very key aspects in discussions of historical infanticide, are new inventions.)

When it comes to politics and war between peoples, very little causes your public to support putting their own lives on the line to go fight somebody than accusing another group of shockingly violating some kind of taboo: infanticide, human sacrifice, and cannibalism are among the big ones.

By the time of the 1890s, the British Empire has some key differences from the Roman empire or various medieval kingdoms: it has colonies all over the world and it's people are, for the most part, literate, and have been for multiple generations. There is a huge role for propaganda to play here, with centuries of European nations justifying their projects of invasion, resource extraction, and enslavement on every continent besides Antarctica with claims against indigenous, non-christian religious communities violating every taboo they can think of. Even long after the communities in question are under European control, the religious argument that everyone in the world must be Christianized remains a useful tool in the political playbook, and authors of adventure stories often reinforce this propaganda, because what is shocking sells magazine subscriptions. Xenophobia is profitable so long as people are only a little scared and a lot thrilled: the idea that there are undeniably bad things in the world but they mostly happen elsewhere can be a comforting one. This is where we find the Canon of Sherlock Holmes, not just in The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge, but as an ongoing theme: places outside of England are exciting because they are both the site of scary, sensational, romantic (in the literary sense) violence, and very far away. Colonies and former colonies, in Australia, India, Indonesia, and America are places where Englishman export themselves to, and violence is imported from. A decent chunk of crime in the Sherlock Holmes canon is either the result of foreigners arriving in England with a violent history, or of Englishmen succumbing to violent impulses while outside of England, and bringing retributive violence home with them. This is also why the criminals so often escape the country but not vengeance: even when English law has a plausible reason to hang the dictator Murillo for one of many murders, it is both more exiting and safer for the audience for the man to be murdered in Madrid.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aquileia

The ancient city of Aquileia was situated near the head of the Adriatic Sea west of the Roman province of Illyria. The strategic location of the city served a crucial role in the expansion of the Roman Republic by serving as a buffer against possible invasions from the Germanic tribes to the north. As a colony with major harbor facilities, Aquileia allowed the Romans to exploit both the neighboring gold mines as well as the region's own rich amber.

To the north of the colony was the independent territory of Noricum. It would become a Roman province in 16 BCE under Roman emperor Augustus (27 BCE to 14 CE). Although Noricum controlled a few minor routes over the Alps, its location south of the Danube and abundant iron and gold reserves were far more valuable to the Republic, allowing trade to emerge between Noricum and northeastern Italy, namely Aquileia. As a buffer and center of trade, the city would eventually become one of the largest and wealthiest cities of the Roman Empire, becoming the capital of Venetia et Istria.

A Gallic Region

Lying to the north and northeast of the Italian peninsula far to the west of Aquileia lay Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul. During the early and middle Roman Republic, the area was not considered part of Italia, which only extended to the foothills of the Apennines. Cisalpine Gaul comprised the area from the plains of the Po River to the Apennines, while Transalpine Gaul extended beyond the Alps northward. Although sources vary, Cisalpine Gaul was initially the home of the Etruscans; however, Celtic tribes from north of the Alps – the Insubres and Senones among them – gradually moved into the area, and by the end of the 4th century BCE, the Etruscans had been completely forced out – thereby enabling the Celts (Gauls) to make the occasional raid into Italian territory.

Around 390 BCE, the Celts were bold enough to push further south and sack the city of Rome. Tom Holland in his Rubicon wrote that "a barbarian horde had burst without warning across the Alps, sent a Roman army fleeing from it in panic, and swept into Rome" (234). Although sporadic raids continued into the 3rd century BCE, in 225 BCE, Rome was able to defeat the Gallic invaders at Telamon – a city located on the coast of Etruria between Rome and Pisa. Realizing the importance and potential of the region, the Romans went on a three-year campaign, capturing Mediolanum (Milan) in 223 BCE. Further attempts to move northward were foiled by the Carthaginian commander Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE) where many of the Celtic tribes sided with Hannibal. After his defeat, Rome continued their foray into the region, establishing colonies at Cremona and Placentia (Piacenza).

Continue reading...

41 notes

·

View notes