#cartesian system

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

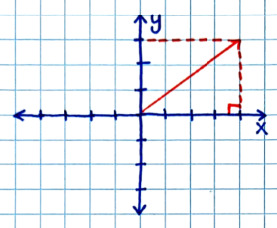

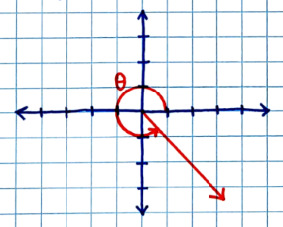

Coordinate Systems

-- Cartesian System = used for linear motion

-- Polar System = used for angles

.

Patreon

#studyblr#notes#math#maths#mathblr#math notes#maths notes#mathematics#geometry#coordinate systems#coordinates#geometry notes#algebra#algebra notes#basic math#basic math notes#basics of math#cartesian system#polar system#angles#graphing#graphing angles#graphing coordinates

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the professor says the answers aren't meant to be long shortly after you write a full page for half a problem on an exam

#im pretty sure i got that half of the problem right but im extremely unsure if he meant for us to do all that or what#i did not get the second part of the question. im still very confused about it#idk. the exam didnt go well exactly but im pretty sure it went better than exam I. but exam I went pretty badly so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯#i dont understand why he asked us to convert a system from cartesian to polar. like. this is grad DEs#sure thats a useful thing to be able to do but i feel like its weird as an exam question? maybe he meant for it to be easy??#but i couldnt make it work quickly enough and gave up. there was also a second part to the question#so i had to just described what i would do based on similar problems weve done in the past#seven stories#DEs

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Screenshot is a post with username cropped out which reads:

goodnight to people who are unable to run

goodnight to people who used to be known for 'running/skipping' everywhere until it

became far too painful and dangerous

goodnight to people who have a walking gait that shows deformity and 'disturbs others'

goodnight to people who have limbs that 'move wrong'

goodnight to people who walk with a limp

goodnight to people who stumble and fall

goodnight to people who use a mobility aid

goodnight to people who use elevators

goodnight to people who use shower-chairs

goodnight to people who use ramps

#cripple punk #cpunk #physically disabled #chronic illness #chronic pain

#disabled positivity #this is about physical illnesses and such please do not derail

#do not derail

Oooh what a nice positivity post, I can't walk because of a condition generally considered neurological (it's under-studied so that's just what we currently understand of it) and also severe executive dysfunction that can leave me catatonic or nearly s-

Oh it's not for people who are in these categories for the "wrong" arbitrary reasons. If your illness is not considered "physical" even if it impairs or completely gets rid of your ability to walk get fucked I guess? /s

Like of course these kinds of people are always like "oh but if it physically disabled you then it's a physical illness" but if you say "okay, my schizophrenia severely disables me to the point of being unable to move" they always say "no it doesn't you attention seeking abled faker!!!"

Like, even setting aside that all neurological conditions are considered neurodivergence, including migraines, seizures, chiari malformations, traumatic brain injuries, depression, PTSD, and so on (neither being permanent nor being something you're born with are requirements for something being neurodivergent, just that they make your neurology different from the norm)...

There is no even divide between physical and psychiatric/neurological conditions.

Schizophrenic catatonia can cause people to literally be completely able to move for YEARS to the point they need a full time carer (I'm lucky that my episodes tend to only last less than an hour/not always be full body and tend to be triggered more when sleep deprived, but I have still nearly LITERALLY DROWNED in the bath because of them, and have had lesser episodes that resulted in me soiling myself because I could not move).

ALS is a degenerative neuron disease, one that affected Stephen Hawking and was the reason he needed a wheelchair and AAC device over time.

Potentially deadly heart conditions are extremely commonly comorbid with anxiety.

Conditions like IBS, which have an extremely high mortality rate when untreated, are highly comorbid with... well, half the DSM, so to speak.

Trauma is suspected to be a possible catalyst for or driver of multiple multisystemic chronic illnesses, including mast cell disorders.

Many common "mental illnesses" can cause tremors, heart palpitations and chronic tachycardia, gut dysbiosis, and more.

Many physical chronic illnesses directly have neurological symptoms, including severe cognitive impairment/dysfunction, and mood swings/emotional dysregulation, to the point where cognitive impairment is part of the diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome that can be used even in the absence of orthostatic intolerance (which is a symptom understood to be typically neurological, as well, though not neuropsychological).

Even ADHD can severely physically disable you, because it essentially shuts down your bodily control center's ability to send commands and run physical tasks. I know so many people think ADHD cannot be that disabling and that it either must be something else or people are just lying, but it turns out that ADHD isn't just not being able to find your keys where you last set them down and being a bit late to scheduled events!

No good night for me, because my physical and psychological symptoms can't be neatly sorted out into simple palatable little boxes. Yeah, I've heard all the "but if you have physical disabilities that counts!! If you have physically disabling symptoms of a condition, that makes it a physical disability!!"

Those same exact people called my housebound, sometimes bedbound, semi-ambulatory wheelchair-using, incontinence-product-needing, caregiver-reliant ass a liar, a faker, attention-seeking, abled, drug-addicted (in a derogatory way, we don't fucking shame addicts here), crazy, delusional, "schizo" freak who just wanted to feel special and talk over "real" disabled people.

The people who said "hey, the brain is a physical organ and part of your nervous system, psychiatric conditions are a result of biochemical and physiological processes in that organ, and often because your brain controls your body and has a lot of interaction with every other system, symptoms and conditions don't neatly fit into one category or another" were the ones who believed me about my experiences with disability, interpersonal and systemic ableism, my mental illness causing actual literal physical inaccessibility in the same way a lack of a ramp for my wheelchair does, that ADHD is my most disabling condition including over ones that could cause me to go into actual organ failure, and so on.

So I'll make a positivity post for people with mobility and gait issues who use mobility aids and such, that doesn't shut out anyone with neuro and psych issues causing those things, that doesn't draw a smug and quite frankly unnecessary line in the sand just to stick it to people they don't consider to be "really" disabled or ever as disabled as "physically disabled" people (something that these kinds of people have directly admitted to my face, that they don't believe neurodisability can ever be as severely disabling or dangerous as physical disability, or even really significantly disabling, while also accusing me of tokenizing myself and other low functioning high support needs neurodisabled people).

I mean, this is the flip side of the coin of making posts about universal or (category-transcending) general ableism or disability experiences and claiming they're physical-disability-exclusive. It's making a post about symptoms that clearly manifest physically, then saying "don't derail and make this about NON-PHYSICAL stuff," with the unspoken threat that any mention of a diagnosis or symptom mechanism they refuse to believe CAN cause significant physical issues will be considered derailing.

I know because it's happened to me a thousand times already.

I honestly hope no one like that sees this, but if they do, be honest with yourself.

What would you do if the 87 percent of autistic people with gait issues talked about their experiences with those things overlapping? What would you do if I talked about how I had to go to occupational therapy as a toddler to change the mobility issues caused by the trauma of infant CSA (with no actual physical injury or trauma related to it)? What would you do if schizophrenic people talked about how catatonia causes them to need mobility aids? What would you do if someone talked about how OCD or delusions or uncontrollable stimming or Tourette's causes their limbs to "move wrong" and "disturbs" other people? What would you do if someone uses a mobility aid, physical accommodations, or has mobility issues for the "wrong" reasons; because of a "mental" illness.

Don't immediately react. Don't jump in to defend yourself about how "oh you'd accept that because it's a physical symptom and therefore a physical disability". Don't tell me, because the majority of you have already SHOWN me what you'd really do. I'm not talking about a small amount of people.

I'm talking about thousands of people who have admitted, either directly or in other posts of theirs, that they actively deny the experiences of, fakeclaim, and speak over people who are physically disabled AND neurodisabled, especially those of us who cannot divide our conditions and symptoms neatly like that.

I'm talking hundreds of examples of blatant sanism and neuroableism, from calling me and people like me crazy and stupid and dangerous and saying we should be institutionalized and have our autonomy stripped from us and even directly using my trauma from exactly that to try and trigger me into a meltdown or self-harming.

I'm talking telling me to prove autistic meltdowns could be dangerous by going and giving myself the brain damage I pointed out self-injurious behaviors during meltdowns can cause. I'm talking people telling me that my suicide attempts should have been successful and that they hoped I'd face actual ableism, often on the same days I was in the ER as a direct result of ableist medical neglect.

Saying "oh but we'll be nice (if we choose to believe you) if you say you're physically disabled" for optics, so you can look like the reasonable tolerant victim of those meanie able-bodied barely disabled neurodivergent disabled people (who are most often also profoundly physically disabled) when they point out your actual behavior towards them 99 percent of the time" isn't going to fly.

Because saying your post is about physical illnesses isn't actually about derailing. If it was, you'd say it's about mobility aids and issues. Because I guarantee it's not about every other physical illness, from sensory impairment to non-mobility-related gut and organ dysfunction and failure to allergenic disorders.

But it is about exclusion. It's about controlling the narrative. It's about a shibboleth to denote that only other people who agree that neurodisabled people are stinky mean invaders in the disability community who make everything about them, while making posts claiming shared experiences are exclusive are all about you and your disability. It's deflecting accountability by giving yourself the out of "oh but see this isn't about anyone with these issues and if you think it is maybe you're the meanie able-bodied ableists we write it for" and weaponizing your own neurodivergence to claim you're not neuroableist in the same post you claim someone is lying about how disabling their neurodivergence is because in your own words yours doesn't disable you that much.

So no, it's not actually open to all physical disabilities, even assuming generously that that's what you mean when you specify physical illnesses (which would generally imply that nonphysical illnesses with physical symptoms don't count to most fluent english speakers).

It's not open to those of us who have messy complex disabilities and who acknowledge that all of emotions and intelligence and cognition and identity is caused by electric currents and chemicals being sent through a slab of meat wrapped in bone (and even that we barely understand, with scientists discovering that a lot of those things might actually be partially caused or driven by processes elsewhere in the body, even leaving aside that the brain itself is also just the CPU of the whole machine and that CPU issues do in fact affect not just the whole operating system but can even cause or lead to hardware issues themselves.

It's not for any of the people who experience or understand these things the "wrong" way.

It's for your little clique to be able to say "you can't sit at our table" and then put on convincing crocodile tears and play victim for your followers when someone dares to call you out for being a petty bully punching sideways at MOST at the severely disabled people you're claiming are your oppressors.

Yeah no, honey. I've seen it in a dozen marginalized communities and every time it's the most vulnerable members that get fucked over by it. I'm not playing your games or engaging with your pathetic power grab.

If anyone is actually interested in how you can create spaces tailored for specific needs and experiences, we're going to shamelessly plug our own medium article about Selective Inclusion. (We probably need to redraft it honestly, but it's got the point at least.) For a brief explanation, selective inclusion is about choosing to focus a space around a need, experience, or identity, and then letting anyone in who believes they share it.

Now, that sounds like what "oh but if you have physical symptoms that counts" covers, but even if that weren't a pretty falsehood, selectively inclusive spaces around an identity focus on the identity itself, without claiming shared experiences are exclusive or that shared needs should only be met for people who use the right label. It is a space explicitly intended to be safe and comfortable for people who are "[identity] AND" - som a space that allows neurodivergent physically disabled people (and people with only "neurodivergent diagnoses" who have physically disabling symptoms) room to talk about how their identities intersect and affect each other and how sometimes they cause seemingly contradictory effects and experiences.

That is not what cripplepunk spaces, which co-opted a word that has historically been used against all of us*, and claimed its reclamation is exclusive only to some of us because a person not fully aware of its history (because I choose to believe it was not maliciously coined) defined the rest of us out of our own history.

*Despite people denying not just disability history but direct evidence of it, the term "mental cripple" appears in a number of actual scientific papers and was in fact the official term for a time, and was used specifically in the context of the institutionalization and brutalization of neurodisabled people in asylums. People were tortured and even lobotomized for daring to be a cripple whose "deformity" (another historically used term for neurodivergent people) was in the brain. But of course, historical revisionism and claims that it's an "outdated" usage despite lived experiences of neurodisabled people contradicting that are "counterevidence" to this.

Anyway usual disclaimer if you're just here to insult me, ignore everything I've said and try to argue with things I either didn't say or that aren't true, fakeclaim me, or all the usual stuff, just block me. You will be filtered and blocked by my comment screener before I ever see it anyway.

People who want to ask good faith questions or discuss personal experiences (including with neuroableism and corpoableism in the disabled community), as long as you don't act as if ableism is stored in the (physical or neuro) disability, you are welcome to interact. I am usually pretty good about assuming good faith and giving the benefit of the doubt as long as there is any to give, and I think it is really important to have conversations about lateral ableism that the majority of us are absolutely capable (hm, maybe an ironic word here, but I think still accurate?) of perpetuating.

#the tags on that post are honestly a good example of how this shit has become a dogwhistle#like fits the definition to a T. it tells ableist exclusionists that they are welcome#and tells neurodivergent disabled people who won't act like mental illness is a corruption of the metaphysical mindsoul that they're not#like sorry not sorry that I think cartesian dualism is bullshit#and that the separation of 'mental' and 'physical' illness is deeply rooted in culturally christian ideas about impurity of spirit and shit#like perhaps actually a huge part of systemic ableism is the compartmentalization of symptoms over like#actual integrative health which looks at the whole picture#and is the reason so many of us spend years getting shunted around to various specialists even when we have fairly common conditions#like perhaps actually actual medical science has been stunted by the fact that multisystemic conditions in particular are studied piecemeal#like you know that's not a good thing right?#anyway at this point I am about to block the whole tag#when your tag is no longer safe for clear members of the very group you claim it's for#you have in fact undercut your own explicitly stated purpose#which means that either that was never your actual purpose#or that gatekeeping and exclusion is more important to you than community solidarity and justice#neither of those are good

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In pursuit of what John Stankey called more hours a day, the technology metes out its steady stream of tiny pleasures as the reward for your sustained attention. Touch the screen—respond to the offered stimuli like a rat in an experiment—and receive what some are now calling a dopamine rush. What follows from this engagement with the devices is an education, in which the system absorbs our responses and begins to shape them. The fetishizing modality of the human unconscious, until now ever-elusive, is given ordinal form as the technology channels the nebulous pull of our proverbial id with Cartesian clarity, our deepest currents of desire rerouted toward the system’s mercantile ends. This careful, unceasing, inhumanly methodical curation of our pleasure principle becomes a larger force in our psyches, as the devices drip-feed us incremental stimulation, which in turn becomes coextensive with the native ground of our very cognition.

Ayad Akhtar, The Singularity Is Here

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Had an idea for a conlang in which instead of pronouns having the standard person/number setup (basically the cartesian product of {1, 2, 3} and {SG, PL}), it uses only the persons of the referents, not caring about how many there are (basically the powerset of {1, 2, 3}).

For example with this you would get a second person pronoun I'll gloss as just 2, but all it means is that the referents are a subset of the audience, independent of whether there are one or many people in that audience. However you'd also get another “second person” pronoun 2.3 which just means the referents include the audience but also people elsewhere (this is definitionally plural).

You'd end up with one third person pronoun (3, can be either plural or singular), two second person pronouns (see above), and four first person pronouns (1 – just singular, 1.3 – exclusive plural, 1.2 – partially inclusive plural, and 1.2.3 – inclusive plural). Additionally you'd also get an empty pronoun ∅, which could be used as an indefinite or impersonal pronoun like “one” or the dummy “it” (perhaps adding an animacy distinction to the system could help here).

It's interesting that the only thing you lose in this system compared to English at least is equivalents to the non-epicene third person singular pronouns “he/she/it”; because both “you” and “they” can refer to singular and plural they map directly to equivalents here. In first and second person you're purely gaining distinctions.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are some fun / amusing / potentially-interesting facts about the process of writing and plotting Almost Nowhere, if anyone's curious.

Major spoilers for the whole of Almost Nowhere under the cut.

(There's really no way to spoiler-censor this material without rendering it incomprehensible. If you haven't read the book, do that first before reading this post.)

(1)

A large fraction of the book's eventual plot emerged from my attempts to patch a single, in-some-sense trivial continuity error I made while writing the very first chapter.

The Mooncrash section of that chapter ends with this sentence (emphasis added):

All parties were used to stillness, now, for the Mooncrash was nearly four years old.

And a few paragraphs later, in the opening of the Academy section, we get this (emphasis added again):

For (as everyone knows) the Shroud is upon us and while it tolerates the Academy — as it presently is, as it has been for the last eight years, a chrysalis, preparing itself step by minuscule step [...]

So: The Mooncrash is 4 years old. The Academy crash is at least 8 years old, and indeed older.

Yet the Mooncrash is also as old as the crash system itself! It was made by humans, during the period between the discovery of the anomalings and the mass-crashing of the human race. (This is only shown in the second chapter, but I had it in mind before then.)

How long has the human race been crashed, then? At most 4 years, and at least 8 years? How could that possibly be?

It would have been easy enough to just edit the chapter, but that's not how I do things. Restrictions, famously, breed creativity. I enjoy attempting to solve puzzles I have inadvertently created for myself, and many of my best ideas have been produced through this process.

It would also have been simple and easy to merely say: "OK, I guess time elapses at different subjective rates, in different crashes."

Amusingly, I ended up doing that anyway! But for some reason, this avenue didn't occur to me at first. By the time I started asking myself whether to include this kind of effect, I already had a different solution in mind.

I spent a lot of time beating my head against the figurative wall, trying to resolve the 4-vs-8-year issue. The early parts of my AN notes are full of this stuff.

----

At some early point, I came up with the idea that the anomalings/shades would deal with troublesome crashes by "rebasing" them, rewriting their histories.

I didn't intend, initially, for this idea to take over the plot as much as it eventually did. It was just a fun idea that underscored the huge power differential between the anomalings and their captives, and felt in line with the Cartesian/Wachowskian themes of transcending a "fake"/illusory world, radically doubting one's own perceptions and memories, etc.

But, having stipulated that "rebases" were a thing, I hit upon the idea that they could be used to modify the total quantity of past (subjective) time inside a crash -- turning 8 years into 4, or vice versa, or whatever.

So, I could fix the problem by stipulating that one -- or both -- of the problematic crashes had already been rebased, in this way.

But why? And by whom?

----

Now, at this early stage, I also had the idea in mind that the character "Anne" would eventually escape from her crash, and that she would have a hand in various major events in the story -- including some events that had already occurred, relative to the "present" of the textual PoV.

But I didn't know, yet, what these interventions actually were.

(I put "Anne" in quotes, here, because in the very early stages I casually assumed that only the PoV Anne introduced in Chapter 1 would be a major character, and that her sisters were merely background material for her personal narrative, like the tower itself. Of course, in the process of thinking through the details of things, I realized that this assumption was needless and indeed counterproductive.)

As often happens when I'm plotting a story, I found that two unknowns slotted neatly into one another, each one providing a potential solution to the problem posed by the other.

We need something for "Anne" to do in the past. Something consequential, something that shows off her newfound agency -- but also something that obscures her role from view. Ideally, something kind of weird, esoteric, "advanced"; something that feels buried inside the deep, dark center of the backstory, which the reader will only "excavate" at the end of a long, strange journey.

And we need someone to rebase the Mooncrash.

That answers the "who?" question. But again -- why?

Well, it was already in the plan that Azad would join forces with Michael, when Michael went in search of his lost Anne. That Anne would meet Azad, as a result, and that it would be Azad who persuades her to return to Michael's crash.

I didn't, at the time, have much else planned for the Anne-Azad connection.

As originally conceived, the "Azad convinces Anne to return" scene was about Azad's uncertain loyalties, and about Anne's lack of exposure to other human beings (and to the power of words, as deployed by human beings with access to real human culture). That is, it merely served specific, separate purposes in the sub-stories of these two characters. There was no intent to set up, or develop, a thread connecting these sub-stories, making Azad a major character in Anne's arc and vice versa.

But that seems like kind of a shame, doesn't it? Why go to the trouble of preparing these characters, and bringing them into contact, if I didn't have anything for them to do together?

Anne and Azad.

We need someone to rebase the Mooncrash.

We need Anne to learn about real human culture, somehow, before she leaves. I knew that, already, though I didn't have a mechanism in mind.

(I also knew, by this point, that causing Azad's appointment as translator was another one of "Anne's" consequential moves. I had conceived of this, at first, as a relatively impersonal act, done only for its historical significance. Indeed, that would have been enough -- but the more the merrier, theme/motivation-wise.)

Problems paired up, interlocked, and became each others' solutions.

(1b)

As is obvious from the above, I didn't have the scenario planned out in very much detail when I wrote the first chapter.

At the time, the story had been gestating in my head for a while, but only as a bunch of vague inklings and intentions.

The proximate cause of writing-the-first-chapter was a sudden and unexpected burst of inspiration. I was riding the bus to a social event, and suddenly my mind was awash with crisp, never-before-glimpsed details about Anne and her tower, the Mooncrash, the Academy, Cordelia's blue dress -- all the stuff of Chapter 1. It felt like a crucial message was being beamed into my brain, VALIS-style, from the Muse / Higher Power.

I had an urge to bail on the social event, turn around, ride back home, and start writing immediately -- what if the magic went away, as suddenly as it had arrived? I resisted that urge and made a perfunctory appearance at the event, but then went back home and wrote as much as I could before falling asleep.

So, when I was writing that chapter, stuff like "four years" and "eight years" wasn't based on any single coherent picture, just vibes and vague inklings.

(I think 4 years probably sounded like the right amount of time for G&A to have been in the Mooncrash, character-wise. Meanwhile, Hector's ascension from the Academy had to be long enough ago that there would be no direct overlap between Hector and any of the current students. The "Bad Old Days" had to feel like something you'd only hear about in rumors, or from authority figures who probably weren't telling the full story.)

(2)

Like TNC before it, Almost Nowhere was originally conceived as relatively simple and straightforward story, only to become something much weirder and more complicated as I fleshed out the details.

As I said above, I only had a very vague "plan" at the outset of the writing process. But I kinda knew where I was going with it, in very broad strokes.

The original arc, insofar as it existed at all, was something like:

The bilateral / anomaling tension is introduced.

The bilateral PoV characters come to an understanding of their situation.

Many of the bilateral PoV characters join up with Hector Stein, who is already trying to defeat the anomalings and free humanity from the crashes.

Azad temporarily sides with the anomalings, and Anne temporarily returns to her captive state. But both them "come around" eventually.

Anne eventually triumphs over Michael, delivers a dramatic monologue castigating him for imprisoning her (etc.), and mounts a successful escape.

Shortly after Anne's escape, some (TBD!) resolution to the main conflict is achieved. Whatever it is, it is proposed/spearheaded by the bilateral faction (and specifically Anne herself), and it somehow exemplifies "the bilateral way of thinking/being."

The humbled anomalings conclude that "the bilateral way of thinking/being" has its advantages, both practically and morally.

So the story, as originally conceived, was much more straightforwardly about the "good" PoV humans fighting back against aliens.

It unabashedly took the bilateral side in the conflict, and it ended with a "beauty of our weapons" sort of moment in which the bilaterals are both victorious and righteous, and in which these two kinds of success are closely linked and almost merged.

I have to imagine that, even in counterfactual worlds where some things went differently, I never would have stuck to this version of the story all the way through.

Because, one way or the other, I would have eventually realized that.. like... this version of the story kind of sucks, right?

I mean, why go to the trouble of introducing these aliens, and trying to make them interesting, only to say "nah, actually these guys were just wrong, it's us and our existing 'ordinary' pre-conceptions that are right, and that's what the story was about all along"?

It would have been "inventing a guy to be mad at," as the saying goes.

Not a great foundation for a story. And the least interesting possible direction to go in, given this kind of setup.

It also presents a seemingly unresolvable tension, for the writer, about how to portray the distinctively "bilateral" nature of the bilateral side in the conflict.

If "bilateral" is as broad a category as the anomalings say it is -- if you and I and all of us, whatever other qualities we possess, participate equally in this sin -- then it's hard to strike a note of emotional triumph around the quality of "bilaterality" that doesn't feel wrong, vacuous, or bloodlessly abstract.

"Woo, yeah, humans are great!" I mean, are they? All of them? You don't get to say "well, only the good ones," here, or "in their ideals if not always their acts," or anything like that. Everyone is included in the relevant category, except for the guys-who-aren't that were invented for this specific story.

It's difficult to make this land properly, in the same way it would be difficult to write a story that inspires "carbon-based life pride" or "having-DNA pride" or the like in its reader.

So this version of the story was dead on arrival. And indeed, by the time I was thinking through the stuff chronicled in (1) above, this version of the story felt like a provisional placeholder, at best, in my mind.

Nonetheless, there are various echoes of it in the story I eventually landed on.

For example, in the original version of "Anne's" escape -- conceived in a much more straightforwardly positive way -- I had Anne reading "real" books in secret, drawing moral strength from them, and then including a bunch of literary quotes in her big dramatic monologue to Michael. (I took inspiration, here, from John the Savage reading Shakespeare in Brave New World.)

And I had the idea that "Anne," being an autodidact, would read omnivorously without making culture-bound distinctions familiar to you and me; that her selection of quotes, in the monologue, would put low culture alongside high culture, infamous books alongside famous ones, etc.; and as a particular case, that it'd be fun if -- before going on to quote Shakespeare and co. -- she began the whole thing by quoting Ayn Rand.

And that one idea stuck, even if the rest of it didn't.

(Or, consider how the idea of "a powerful move in the conflict that exemplifies the bilateral way of thinking/being" actually crops up multiple times in the finished story, right up to its last scenes. One can see traces of it in the "trick" that obsesses Michael, in the use of autobiographical writing to build up nostalgium, and in Annabel's improved crash design.)

(3)

I came up with the Mirzakhani Mechanism relatively late, in between writing Chapter 13 and writing Chapters 14-15 (in which the MM is introduced).

The MM was a product of looking back at the sci-fi elements that already existed in the story, like crashes and rebases, and trying to invent some single underlying explanation that covered all of them in a relatively parsimonious way.

This basically "worked," I think -- it certainly worked better than I had been expecting, after playing the dangerous game of "write a bunch of weird stuff and hope you'll be able to explain it all later." (I remember talking to one reader who was shocked that I hadn't had the MM in mind from the very beginning, which was flattering.)

It also had unintended consequences that kinda took over the story, but largely in a good way.

Earlier, I had planned to have the post-rebase crash timelines "screened off" from the outside world somehow, so that rebasing a crash wouldn't mess up the timeline of the outside world. But, once I'd fixed the idea that "rebasing is an MM event" in place, I realized that this wasn't consistent with the way MM events were meant to work. Instead, the exposition in Ch. 15 directly implies the stuff about rebases that Grant realizes much later in Ch. 41.

Once I'd noticed this, it was obvious that it was extremely important, and I re-incorporated it into the broader plot.

On a related note, I eventually decided that the account of the anomalings "going backward in time to our era" in Ch. 15 didn't really make sense. This meant I needed a different, more viable way anomalings and bilaterals to exist at the same point in time.

This line of thought, along with several others (like "what happened to all the nonhuman organisms?" and "which parts of the MM multiverse are real?"), eventually led me to invent Everywhere-Heaven and the beasts.

That happened right at the start of 2022, between Chapters 21 and 22.

It quickly became clear that the E-H/beasts stuff could be put to a lot of valuable use in story's third act, which was largely a worrying blank space in my head (even at this point!). From thereon out, I worked on fleshing out the third act behind the scenes while writing the second.

Not coincidentally, Chapter 22 contains a ton of E-H-related foreshadowing, and also some hints that human scientists (like Aidan in Ch. 15) had never fully understood the anomalings.

The use of Maryam Mirzakhani, a real (and recently deceased) mathematician, was a weird choice and arguably one in poor taste. All I can really say in defense of it is that it came to me suddenly, and had a number of properties that fit the vibe of the part of the story in which it appeared, and I have a policy of "going with my gut" when it suggests such things to me.

I felt similarly about this choice and another thing introduced in Ch. 15, the nuclear attack intended to kill scientists. Both of these things underscored the fact that the story took place in an alternate reality. And both felt sort of "edgy," "too dark," "too close to the real world" compared to the tone of the story so far. But I wanted to take the story to new places in the coming acts -- "darker," "more real" places -- and something felt right about introducing these elements at this exact point, as signposts providing an indication of where things were headed.

(4)

The phrase "NOWHERE TO HIDE" was originally "NO MERCY," in my notes.

And the abbreviation "NM" for "NO MERCY" was used throughout my notes for Nowhere-To-Hide related stuff, e.g. "NM Annes."

This wasn't the product of much thought, just the first thing that came to mind that had roughly the correct vibe. I almost immediately concluded that I'd have to replace "NO MERCY" with something else in the work itself, since it would seem like an Undertale reference that I didn't intend to make.

"Moon" was originally just a placeholder name -- a shorthand for "the 'NM Anne' who rebased the Mooncrash." But I liked the idea of actually using it, once it had occurred to me.

The corresponding placeholder name for A11 was "Ling," as in "linguist" (but also an actual name).

(5)

I went through 3 different outlines of the third act.

Really, there was a first outline, which was really bad, and then there were two slightly-different versions of a very different outline that mostly corresponds to the finished draft.

The first, bad outline was amusingly titled "notes-satisfying-ending.txt", because I explicitly used this post about "satisfying endings" as a guideline while writing it.

(To be clear, I don't think the linked post was to blame for the badness of that first outline. I didn't ultimately find the post very helpful as writing advice, but the "satisfying ending" outline wasn't even a "satisfying ending" in the post's own terms, and was also bad in unrelated ways.)

I don't want to go into much detail about the bad outline. It was really bad, and also really different from what eventually occurred. It's honestly a pretty embarrassing document.

A lot of the key ideas were there (E-H, etc.), and the very end of the story was roughly the same. But it had a ton of needless flaws that I later corrected. Various existing character arcs and motivations were dropped and never picked up, or suddenly diverted in some new and unfruitful direction; way too much time was spent on getting characters and objects from point A to point B, or otherwise sort of rambling about in a way that didn't matter in the end; it included a lot of whimsical "fun ideas" that weren't necessary and would have added clutter to an already very full canvas; etc.

I never got to the point of building a chapter-by-chapter version of this outline, but I'm sure it would have much longer than the existing third act, also.

The existing third act is pretty long, but it was actually the result of an aggressive pruning and tightening process.

If the "satisfying-ending" outline had a single greatest flaw, it was terrible pacing. Lots of slack, lots of empty space, and when big things did happen, they came out of nowhere, not really prompted by what came immediately before them.

The next draft of the ending resulted from taking the raw materials of "satisfying-ending," purging all the dross, re-thinking all the obviously flawed stuff, and then trying to rearrange the pieces in front of me in a way that was maximally "tight" and interconnected, with questions and tensions introduced and then resolved in a rapid-fire manner, and without any major thread "sitting around in the background" long enough to feel stale, or get forgotten.

That outline was in a file called "notes-good-end.txt."

Much later, I tightened up the plan even further, merging some things that were originally in separate chapters. This was in a file called "notes-true-end.txt", and -- true to its name -- was the version reflected in the book itself.

So there was "satisfying-ending," which sucked; "good-end," which was good; and "true-end," which was slightly better.

(I realize the multiplicity of the ending, and the account of deliberate "tightening" etc., is in apparent tension with my recent account of working by direct inspiration.

There are a few things I can say about this tension.

For one, it really is true that the third act of AN was more deliberately reasoned-out, and less directly-inspired, than some of the earlier stuff. This is kind of inevitable: you don't get to do anything after an ending, that's what an ending is, and so you have to deliberately try to make the final act of a story fully work as a thing unto itself, rather than writing checks in the hope of cashing them at some later point.

And separately, I do think the final version of the ending feels "more real," "more true to the work" than the satisfying-ending draft.

I think I was aware, even while composing "satisfying-ending," that it felt off and wrong in some ways. But it was only after going through the exercise of creating a complete ending -- some sort of complete ending -- that I was able to look back and say "OK, this fits, but this doesn't fit," and distill something that actually felt right.)

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triangle Tuesday 7: the joy of coordinates, railroads, and you didn't see that coming

"There is no royal road to geometry," Euclid supposedly said to Ptolomey, and this is true. There is, however, a commuter rail line called analytic methods, and that's what I want to talk about today.

Everything I have discussed in this series so far falls under the heading of synthetic geometry -- that is, geometry done only using axioms such as Euclid's, without recourse to numerical formulas or coordinate systems. This is in contrast to analytic geometry, which most people are familiar with from the cartesian coordinate system of the plane.

Today, we're doing a different coordinate system, but the cartesian system provides a familiar jumping-off point. In the cartesian plane, we specify a point relative to two reference axes. The coordinates represent the perpendicular distances from the axes, and these distances are positive or negative depending on which side of the axes the point lies.

We are going to do something like that, but rather than orthogonal axes, we will take the sidelines of a triangle as our reference. This will give us three coordinates for only two dimensions, which seems redundant, but hold on and it will make sense in a bit.

First we'll look at the basics of this system, then I'll go through and find the coordinates for each of the triangle centers we've looked at so far, and we'll end with a bit of a surprise.

Coordinates for triangles

Why do I call this a commuter rail line? Because unlike a royal road, anyone can use it, and it can be a faster way to get to certain places. On the other hand, it doesn't always go exactly where you want, and we have to build some infrastructure before it becomes useful.

Let's work our way there by first adding some notation to our triangle. It's conventional in triangle geometry to use the uppercase letters A, B, and C for both the vertices and the size of the angles at the vertices, and lowercase letters a, b, and c for both the sides opposite the corresponding vertices and also the length of those segments.

This may seem liable to confusion in theory, but in practice context makes clear which sense is intended. If B or b appear in a drawing, they refer to points and lines. If they appear in a numerical expression, they refer to angle sizes or lengths.

Now let's look at a point P. We will label its feet on sides a, b, and c as Pa, Pb, and Pc, and the segments joining P to the feet as p1, p2, and p3. I don't know of any standard term for these segments. I'm just going to go with the obvious and call them legs.

And because we are all comfortable now with using the same symbol for a line segment and the length of that segment, I will also use p1, p2, and p3 as the signed distances from P to the sidelines of the reference triangle. The distance will be positive when P is on the same side of the sideline as the triangle, negative when P is on the other side, and zero when P is on a side line.

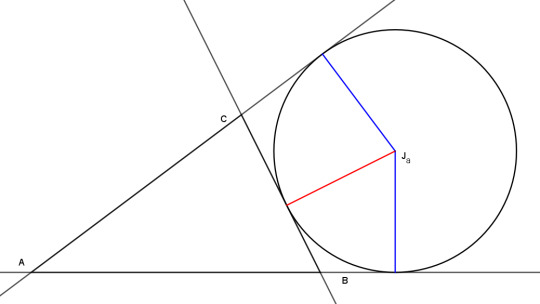

Here's P lying outside the reference triangle, with a negative p1 (in red) because it lies on the opposite side of line a from the triangle, a zero p2 because it is on line b, and a positive p3 (in blue) because it is on the same side of line c as the triangle.

Okay, so far so good. This is not too different from cartesian coordinates, except our axes aren't perpendicular and we have a seemingly unnecessary third coordinate. Two signed distances ought to uniquely identify a point, right?

Here's the difference that makes the third coordinate necessary: we are going to ignore absolute distances and only consider ratios between the coordinates. If we have a point with legs measuring p1, p2, and p3, we will consider any three numbers k*p1, k*p2, k*p3 to be the same coordinates (as long as k is not zero). We'll write this triple ratio as p1 : p2 : p3 in order to distinguish these coordinates from triples of cartesian coordinates in R^3.

This coordinate system is called homogeneous trilinear coordinates. (The homogeneous part comes from abandoning absolute distances and considering only ratios. If we kept to absolute distances, we would have exact trilinear coordinates. Hereafter I will just refer to the homogeneous version as trilinear coordinates, or trilinears.)

Why is this useful? Various reasons. One of them is that with one exception, any three real numbers specify a point. No point can lie on the outer side of all three side lines, so with exact coordinates, three negative numbers don't correspond to any point. But with homogeneous coordinates, we can multiply any coordinate triple by any nonzero real number k and it still represents the same point. Letting k = -1, we have x : y : z = -x : -y : -z. No problem with negatives.

But the main advantage of trilinears is that we can give a nice representation to important points of the triangle, and that lets us easily use analytic methods on them. The vertex A, for instance, has zero distance from sidelines b and c, so its trilinears are 1 : 0 : 0 (or equivalently any other nonzero real number for the first coordinate, but using 1 is simplest). Similarly vertex B is 0 : 1 : 0 and vertex C is 0 : 0: 1 . No point can lie on all three lines of the triangle at once, so 0 : 0 : 0 is the single coordinate that does not correspond to any point.

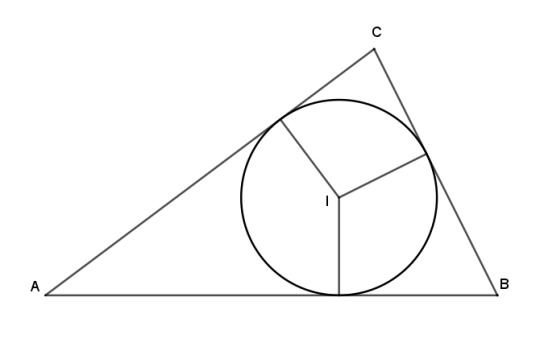

The incenter

Let's see how this works using the incenter as an example. The incenter is inside the triangle and equally distant from the three sides. With the three legs being equal, its trilinear coordinates are as simple as they can be:

The trilinears of the incenter are I = 1 : 1 : 1.

That's a very nice and neat expression, but not actually very informative. We already knew this about the legs of the incenters, because they are all radii of a common circle. Furthermore it's easier to understand "the incenter is the point that is equidistant from the sides" than "the incenter is the point with trilinear coordinates 1 : 1 : 1." So far our coordinate system hasn't shown us anything new or made anything clearer. Well, we're still building our commuter rail line. It will pay off after we complete more ground work.

But while we are at this stop, we might as well take note of the excenters. Here is excenter Ja, equidistant from the sidelines of the triangle, but on the negative side of line a and on the positive sides of lines b and c. So its trilinears are -1 : 1 : 1, and similarly for the other two excenters.

The centroid

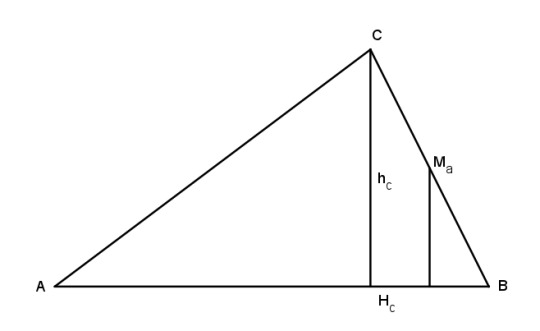

The centoid is defined as the intersection of the medians, and the medians are defined as the lines that join the vertices and midpoints of the opposite sides. So let's start by finding the coordinates of the midpoints. The midpoint of side a, Ma, has first coordinate 0, so we just need to figure out the ratio of distances to the other two sides. To do that, we'll first take a look at the altitudes of the triangle.

Let hc be the altitude from C to c, and let △ be the area of triangle ABC. Then by the standard formula for area of a triangle,

△ = 1/2 * c * hc

hc = 2 △ / c.

Now look at the midpoint of side a. By similar triangles, the length of its leg to side c is half the length of hc, or △/c. By the same logic, the leg extending to side b has length △/b. That gives us the ratio we were looking for, so the trilinears are 0 : △/b : △/c. Since this is a ratio, se we can divide through by △ to get 0 : 1/b : 1/c, which is nice and clean.

Repeating this for the other two sides, we get trilinears for the midpoints of the sides as:

Ma = 0 : 1/b : 1/c

Mb = 1/a : 0 : 1/c

Mc = 1/a : 1/b : 0

Now, in general, when we have two points, we can find an equation for the line that runs through them, and given two lines, we can find their point of intersection. The first method uses the fact that three points P, Q, and R with trilinears p1, p2, p3, etc. are colinear when this determinant is zero:

And by letting one of the points be variable x : y : z, we get this determinant

which gives us the general form of an equation for a line:

d x + e y + f z = 0.

Don't know what a determinant is? Don't worry! We don't need to use this method. I'm just mentioning it out of a sense of duty to completeness. In this case we're working with a median, which is a cevian, which makes things very convenient. Recall that a cevian is a line that runs through one of the vertices.

We worked out that for the point Ma, the legs to the b and c sides are in the ratio 1/b : 1/c. By similar triangles, any point P on this cevian will have legs to those sides in the same ratio. In other words, a point on the c-median must have triinears of the form u : 1/b : 1/c for some u.

The centroid G is one such point. It's also on the b-median, so it must also have trilinears of the form 1/a : v : 1/c. It's also on the c-median, so it must also have trilinears of the form 1/a : 1/b: w. So instead of working with the equations for the medians, we can get the trilinears directly from points known to lie on the medians. Therefore,

The trilinears of the centroid are G = 1/a : 1/b : 1/c.

For more completeness, here are equations for the medians:

y/b - z/c = 0

x/a - z/c = 0

x/a - y/b = 0

To find the intersection of two lines m and n with coefficients m1, m2, m3, etc., take this determinant:

The trilinears are then equal to the minor determinants:

If you are familiar with linear algebra and enjoy finding determinants, go ahead and calculate it using the coefficients above and you will get 1/a : 1/b : 1/c. Otherwise, don't worry about it.

The symmedian point

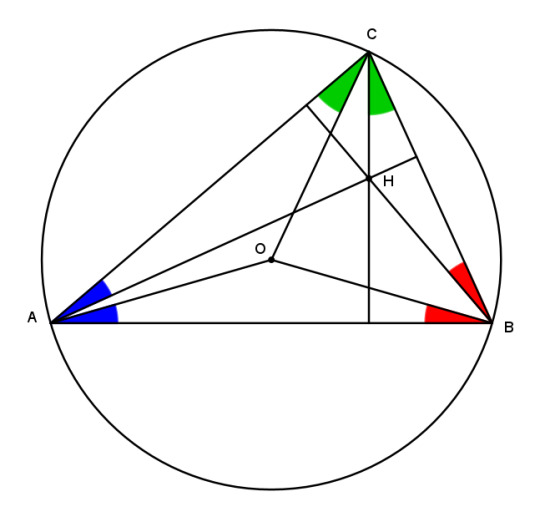

Let's now look at the symmedian point, which is the isogonal conjugate of the centroid. Recall that when P and Q are isogonal conjugates, the cevians of P are the reflections of the cevians of Q across the angle bisectors, and vice versa. In other words, at each vertex the cevians of P and Q make the same angle (in red) with the angle bisector (dashed line). Equivalently, they make the same angle (in blue) with the sides adjacent to the vertex. And that sets us up for our next shortcut:

Theorem: If a point P has trilinear coordinates p1 : p2 : p3, then its isogonal conjugate has coordinates 1/p1 : 1/p2 : 1/p3.

Proof: as the two green triangles are similar and the two blue triangles are similar, we have CP/PPa = CQ/QQb and CP/PPb = CQ/QQa. Then

PPa/QQb = CP/CQ = PPb/QQa

PPa/PPb = QQb/QQa.

Then given a ratio d : e : f, the ratio 1/d : 1/e : 1/f gives the desired reciprocal ratio between any corresponding pair.

With that result, and knowing that the centroid is 1/a : 1/b : 1/c, finding the coordinates of the symmedian point is simple:

The trilinears of the symmedian point are K = a : b : c.

Before moving on, we should take note of two things about our theorem on isogonal conjugates. First, the formula is undefined for any point with a zero coordinate, so points on the sidelines of the triangle don't have isogonal conjugates. Also, the incenter is its own isogonal conjugate, as are the three excenters, and they are the only points with this property.

The orthocenter

To find the coordinates of the orthocenter, let's go back and look at that altitude again.

Let h be the altitude from C to Hc. Draw leg hc1 from Hc to side a. Then the triangles to the right of h are similar and the two angles marked in red are equal. The length of segment hc1 is therefore h * cos B. In the same way, the blue angles are equal and hc2 = h * cos A. Thus the trilinears of Hc are cos B : cos A : 0.

This is an inconvenient form, though, because the first coordinate is in terms of B and the second in terms of A, which is the reverse of what we want. So we'll divide through by the factor cos A * cos B:

cos B / (cos A * cos B) : cos A / (cos A * cos B) : 0

= 1/ cos A : 1/cos B : 0

= sec A : sec B : 0.

That's the c-altitude. By symmetry, the a- and b- altitudes are:

0 : sec B : sec C

sec A : 0 : sec C

And conveniently, altitudes are also cevians, so we can use the same shortcut here that we used for the cetroid, and get the trilinears directly from these points.

The trilinears of the orthocenter are H = sec A : sec B : sec C.

If you want to play around with the determinant formula, you can go ahead and find the equations for the altitudes. I found it a little more convenient to use the forms cos B : cos A : 0, etc..

The circumcenter

Cevians are nice to work with, but not useful for the circumcenter, which isn't defined by cevians. It's defined by perpendiculars, and while there is a formula for perpendicular lines in trilinear coordinates, it's awful and I'd rather not use it. Sometimes the commuter rail line doesn't run where you want and it's easier to go a different way.

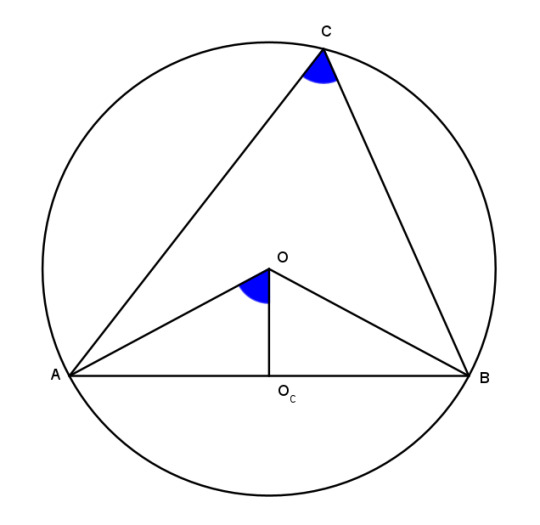

So we'll fall back on synthetic methods. The circumcenter O is the intersection of perpendicular bisectors of the sides, and is the center of the circumcircle. In particular, note that the segments OA, OB, and OC are radii of the circumcircle and equal.

Now consider angle ACB. It subtends the segment AB and has measure C. By our old friend the inscribed angle theorem, angle AOB = 2C. Segment OOc, one of the legs of O, bisects AB perpendicularly, so angle AOOc is half of AOB, equal to C.

Now by the definition of cosine,

cos AOOc = OOc/AO = cos C

OOc = AO cos C.

Similarly we can establish lengths of the other legs:

OOa = BO cos A

OOb = CO cos B.

Therefore the trilinears of O are BO cos A : CO cos B : AO cos C. But AO, BO, and CO are all radii of the circumcircle and equal, so

The trilinears of the circumcenter are O = cos A : cos B : cos C.

But look back at the orthocenter! The secant is the reciprocal of the cosine. And what did we just learn about reciprocal coodinates? Doesn't that mean -- yes, yes it does!

The circumcenter and the orthocenter are isogonal conjugates.

They've been conjugating away right under your nose this whole time and you never even noticed!

And this, finally, brings us a result that is much easier to establish with trilinears than with synthetic methods. There probably is a clever synthetic proof that O and H are isogonal conjugates, or even many proofs, but I would have to stare at a bunch of lines for a long time before I could come up with one. Using trilinear coordinates, we can establish this relationship at a glance. And that sort of quick trip that anyone can take is the reason we use the commuter railroad of analytic methods.

If you found this interesting, please try drawing some of this stuff for yourself! You can use a compass and straightedge, or software such as Geogebra, which I used to make all my drawings. You can try it on the web here or download apps to run on your own computer here.

An index of all posts in this series is available here.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

been slowing down on thinking about phil of math so before i forget too much, notes towards my perspective. i'm sure i'll come back to this at some point

as the sage once said, "always historicize". an account of the nature & subject matter of mathematics must be compatible with its history. it doesn't need to fully explain it — if it could, it'd just be overfitting a theory to the contingencies and ambiguities of history — but it should be capable of interfacing with the history of mathematics and also with historical views of the nature of mathematics. (this doesn't rule out all platonisms but it does kill the "ontologically minimal" ones.)

mathematics is a broad category of human activity and we should strive to understand all of it instead of declaring that some subcategory is the true essence. the framing of models (which can be v useful!) as "reductions" of one field to another, the philosophical exaltation of formalized proof at the expense of the informal, the neglect of the real process of coming to definitions and proofs: all mistakes.

the ontological question is overemphasized. however, every answer to the question has to account for human thought about mathematics which means going through a sort of psychologism or intuitionism even if it's a derived phenomenon and not a foundation; this is where every actual consequence of the ontology will manifest, so it should be more of a focus. traditional intuitionism is too restricted & built on a shaky foundation. also, platonism is silly but hard to talk around.

per above: i think mathematics consists of a process of mentally abstracting consistent structures — from real things or other abstractions — and applying various practices to understand them and keep our thoughts about them consistent. (semi)formal proof is one of the most crucial of these practices but not the only one

connections between fields of mathematics occur where the structures they study overlap or coincide. neither side has to be "primary" or "foundational" — rather, a connection opens up the use of practices developed for the study of one field to the study of another, and sometimes both. cartesian geometry allows both the use of algebraic techniques to construct and study geometric objects and the use of geometric interpretations & techniques to study systems of numbers (calculus, phase space, and so on)

the striking similarities between independent historical developments of mathematics are because the same abstract structures (numbers, geometry, polynomials, etc) are useful enough to appear in these different contexts. a conclusion about what's true of a structure is not contingent on anything but the structure; but which structures are studied, and which statements about them are considered relevant, is purely contingent on the world, historically variable, and sometimes ambiguous. (contingent on which elements of the world?)

the use cases which originate a field are often not the ones which drive it internally

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

my semester ended last week, so here's a list of strange/unhinged things my precalc teacher said throughout the course

you guys are the bread sandwiches of sandwiches! that's how classy you are.

it's like reading greek, in english...

we got a new president of america... maybe we'll have a new president of canada.... maybe it'll be the same person. it'd be tremendous.

we could have guns, and live free!

you can keep your quizzes, put them on the fridge. .. or put them IN the fridge, keep 'em fresh!

don't be cooked— be cooking!!

you know, my uncle invented the cartesian coordinate system.

you know that guy who eats cacti for a living? my uncle did that once.

do you call them quills on a cactus, or only for porcupines? because my uncle eats porcupines for a living too.

you're ruining this family, max (about a character in a word problem, not a real person)

they're all bad people. especially carl, and not just because he's bad at math (also about a word problem character)

I don't even want to think about carl. he's a disappointment not only to himself, but to his family and his community (same as above)

we're gonna talk to your dad, we're gonna tell him about how much shame you should be feeling.

I'm not lying to you. I do lie quite a bit, but I'm not lying now

we've already established that I enjoy lying.

"last year was 1963." correct!!

I'm just buying one extra so I look like I have loved ones. one for me, and one for my imaginary loved ones

you can change the question! you can do that in university, too. I changed so many questions on my physics tests.

stick a fork in it, cause this baby's done!

graphing comes from the same two places. it comes from the heart! ...and it comes from a table of values.

if you've gotten rid of snap, and you've replaced it with desmos graphing app, then you're on your way to becoming a good person.

counting is hard, guys.

I hate to— actually, no. I don't hate to be mean, I actually enjoy it! I thrive on it, it warms my heart up.

after the exam, we're gonna share our hopes and dreams with the class. and if they're not good enough, you fail! so think about your hopes and dreams!

I'm probably the most ninja-like teacher you know.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Consciousness, Subconsciousness, and Unconsciousness

The study of consciousness, subconsciousness, and unconsciousness is central to philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience. Philosophers and scientists have long debated the nature of the mind, self-awareness, and the layers of mental activity that influence behavior, perception, and cognition. Here's an overview of the three concepts:

1. Consciousness

Definition: Consciousness refers to the state of being aware of and able to think about one’s environment, existence, thoughts, and sensations. It is the subjective experience of the mind, or what is often called "phenomenal experience"—what it feels like to be you at any given moment.

Philosophical Theories:

Dualism (René Descartes): Descartes famously proposed that the mind and body are two fundamentally different substances. According to Cartesian dualism, the mind is immaterial, and consciousness is a non-physical property of the mind. The body, on the other hand, operates like a machine.

Materialism/Physicalism: Materialists argue that consciousness arises from the brain's physical processes. According to this view, consciousness is a product of neuronal activity, and there is no separate, immaterial mind. Contemporary neuroscientific approaches align with this view, seeking to explain how brain activity correlates with conscious experience.

Phenomenology (Edmund Husserl, Maurice Merleau-Ponty): Phenomenologists focus on the first-person experience of consciousness. For them, consciousness is always consciousness "of" something (intentionality), and they explore how the mind structures experience.

Hard Problem of Consciousness (David Chalmers): Chalmers distinguishes between the "easy" problems of consciousness (understanding brain functions) and the hard problem, which is explaining why and how physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experiences, such as the sensation of color or pain.

Panpsychism: This is the view that consciousness is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of the universe, meaning that all matter has some degree of conscious experience, not just humans or animals.

2. Subconsciousness

Definition: The subconscious refers to mental processes that occur just below the level of conscious awareness. These processes influence thoughts, behaviors, and perceptions without being actively noticed by the individual.

Philosophical Perspectives:

Freudian Subconscious: Sigmund Freud introduced the concept of the subconscious (often used interchangeably with "preconscious" and "unconscious" in his early work). For Freud, the subconscious includes thoughts and desires that are not currently in conscious awareness but can become conscious when triggered (e.g., through memory or slips of the tongue).

Dual-Process Theories: Modern cognitive psychology divides thought into two systems: System 1 (fast, automatic, subconscious thinking) and System 2 (slow, deliberate, conscious thinking). Subconsciousness is often associated with System 1, where many decisions and impressions are made without conscious deliberation.

Carl Jung’s Collective Subconscious: Jung expanded on Freud's idea of the subconscious with the collective unconscious, a layer of the unconscious mind shared by all humans, filled with archetypes and universal symbols.

3. Unconsciousness

Definition: The unconscious refers to mental processes, desires, and memories that are entirely outside of conscious awareness and typically inaccessible to introspection. In psychological theory, the unconscious is thought to hold repressed feelings, unresolved conflicts, and primitive desires.

Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives:

Freudian Unconscious: Freud proposed that the unconscious mind is a repository for desires, fears, and memories that are too painful or socially unacceptable to acknowledge consciously. These repressed elements of the mind influence behavior in subtle and sometimes disruptive ways.

Id, Ego, and Superego: In Freud's structural model of the psyche, the id represents unconscious primal desires, the ego navigates reality, and the superego represents moral standards. The unconscious mind contains both the id and parts of the superego.

Jungian Unconscious: For Carl Jung, the unconscious mind is divided into two parts: the personal unconscious, which is unique to the individual, and the collective unconscious, a shared repository of human experience. The collective unconscious holds archetypes, symbols, and motifs that recur across cultures and history.

Philosophical Issues with the Unconscious: Some philosophers question whether it makes sense to speak of unconscious mental states. If a thought or desire is not accessible to conscious awareness, can it truly be said to be "mental"? This challenges traditional notions of mind and cognition.

Key Questions in the Philosophy of Consciousness, Subconsciousness, and Unconsciousness:

What Is the Nature of Conscious Experience? Philosophers debate whether consciousness can be fully explained through physical processes or whether something irreducible remains. The hard problem of consciousness remains one of the most pressing and unsolved issues in philosophy.

To What Extent Do Subconscious and Unconscious Processes Influence Behavior? How much of our decisions and perceptions are shaped by thoughts and feelings outside of our awareness? Psychological experiments have demonstrated that subconscious cues can powerfully affect behavior, challenging the belief in fully rational decision-making.

Is the Unconscious Real? Philosophical skepticism exists about whether unconscious thoughts and desires are truly "thoughts" if they cannot be directly experienced or known. Others argue that the unconscious is a necessary concept for understanding repressed feelings and psychological disorders.

Relationship Between the Three:

Consciousness represents active awareness, decision-making, and self-reflection.

Subconsciousness includes processes just below the level of awareness, such as habits, reflexes, or memories that can be brought into consciousness.

Unconsciousness involves deeper, hidden aspects of the mind, inaccessible to conscious introspection but influential in shaping desires, emotions, and behaviors.

The philosophy of consciousness explores self-awareness, subjectivity, and the mind-body problem. Subconsciousness refers to mental processes that influence behavior outside of immediate awareness. Unconsciousness deals with repressed desires and memories that operate beyond conscious thought. Each concept has rich philosophical implications for understanding the mind, free will, identity, and the nature of human experience.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ontology#metaphysics#psychology#Consciousness#Subconscious#Unconscious Mind#Epistemology#Philosophy of Mind#Freud#Carl Jung#Hard Problem of Consciousness#Phenomenology#Cognitive Psychology

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

No. 5 - D2, Shrine of the Kuo-Toa (August 1978)

Author(s): Gary Gygax Artist(s): David C. Sutherland III (Cover), David A. Trampier Level range: Average of 10, preferrably party size 7+ players Theme: Underground exploration Major re-releases: D1-2 Descent into the Depths of the Earth, GDQ1-7 Queen of the Spiders

I'm almost speechless. This is the most 1e module cover to ever have 1e'd. It is perfection. The way the combat is perfectly perpendicular to the step pyramid. The bondage gear fishman who has a complete fishhead so you 100% understand he's a fishman. Lobster mommy saluting the troops. It's just….it's what dreams are made of.

So I'm already in love with this module, deeply and irrationally in love with it, before breaking the cover. If you're BORING you might prefer the later Jim Roslof cover art that's got lame things like technical proficiency. Ugh. The shit I have to put up with.

Anyway, there's a lot to talk about with D2! It's a lot of firsts for an official TSR product, and critically it's a lot of GOOD firsts.

It's the debut of the Kuo-Toa, one of the most fun groups of people in D&D! It's the first module that doesn't presume the enemy will be inherently aggressive! It's got a lot of negotiation and learning! The only good type of gnomes debuts with the Svirfneblin! This model of "alien settlement where you are not instantly attacked but you gotta learn the social rules and play along" is just the best. This will be done again in U2 and I adore U2. Yeah it's how it feels to go to a different country, especially one that doesn't speak your language, and just have everything be a little "off" compared to what you're used to, but. To me, it will always be The Autistic Experience. How well and quickly can you learn these bizarro social rules you can't intuit and what's the fewest number of whacks to the head it takes to get there? How long can you swallow your complaints when you see stuff that's obviously cruel, but the people around you don't perceive it as cruel anymore because it's The Way Things Are and they will actively defend the cruelty of it?

Ok, ok, back to your regularly scheduled program.

Gary starts off this week's festivities by telling you to be toxic to your players:

Sometimes it feels like there's three Garys in a trenchcoat and they take turns writing the modules.

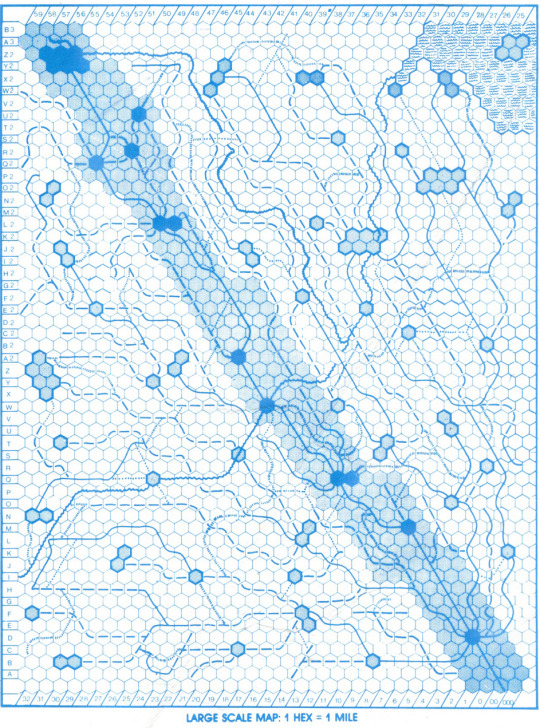

So D2 starts in the cave at the immediate end of D1 and, let me derail already by saying that I really, really hate old-style hex maps. I cannot follow them -- I don't mean I don't understand how you're supposed to follow them, I mean it's nearly impossible for me to follow the diagonal to the destination. Your coordinate here is R20. Here is your map. Follow the 20 axis diagonally upward and rightward until you intersect with the R row. Can you do it?

Personally, I can't. My eye cannot follow that straight line, it will get lost in the mix of blank identical hexes and occasional interest objects. I sat here trying to follow it for 5 minutes and I couldn't do it. I need a straightedge to do it. The correct answer is that if you follow the light blue area from the bottom right towards the top left, it's the hex up and left of the fourth fully black hex you run into -- the leftmost of the two touching black hexes. I tested this against a few guinea pigs and no-one else could mange it either. Later we will admit defeat and that this axial coordinate system for hexmaps is, uh, really fucking bad, and replace it with offset coordinates (or even better, double coordinates) which more closely resemble normal cartesian coordinates, and by extension are not Eye Strain Central. They have the downside of different eyestrain (tiny font) and that you literally cannot fit as many hexes on the page, but the point of a graphic is to communicate information and the axial coordinate hexmap is bad at that unless you're playing on a huge table with like, two DM screens.

Yes this rant should've gone in D1, mea culpa. In my defense, D1-2 is, basically one module in two parts, they're not really separable.

Here's the coordinate lined out for you, since I imagine many of you have the same issue:

So, now that I have a headache trying to read, we can get to the actual text of the adventure again. Now keep in mind that max movement rate is 1 hex per 1 inch of movement for the slowest member of the party (so like, your guy wearing platemail has 60ft of movement, 10ft to the inch: 6 hexes per day). This means you could hypothetically arrive at the final location as quickly as 22/6=4 days of gameplay, 3 if no one including hirelings wore plate. That is, if you beelined to D2 by sheer luck, never got lost, never got distracted, never got slowed down, never had to take a rest day. Which is good because the food in The Depths seems questionable.

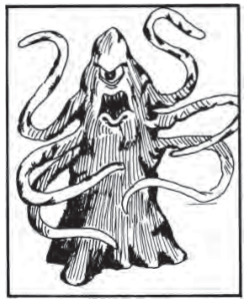

The first segment of the adventure is mostly reprinted from D1 -- random tables and maps and the like. We do get the addition of everyone's favorite early DND trope: a slavery table! And also happilly we get some goopy guys to move your eyes away from that shit:

Which, is a lot more my speed. More goopy guys. It's a roper, actually, although I frankly didn't recognize it. It looks more like the monster from Dexter's Lab? Apparently Ropers have changed a lot in the last 50 years.

So it's all random tables teasing that we're going to end up arriving at a shrine soon. There is a special entry in the back for the new Kuo-Toa and Svirfneblin, and oddly the Svirfneblin don't get a header? We don't learn much. We know that they're natural elemental summoners, that they're "natural fighters", and that they live at some unstated cave somewhere. They like their stun gas darts, they "communicate with racial empathy" (which I guess means body language?) outside their own domains, deep gnomish at home, and underworld cant when they're trading, plus earth elemental-ese. So they learn a lot as kids. They love them some traps, too, basically they're the gnomish Rambos and I love them for it.

Meanwhile, our titular Kuo-Toa get a pretty standard write-up. Driven underground, human sacrifice, raiders, like their war parties. Their priests like their mancatchers, which are based on lobster claws, they spawn in pools, they can spontaneously generate lightning by holding hands (???), are too slippery to grab, can see both infrared AND ultraviolent, can see you moving through basically any magical means, immune to poison, paralysis, charming, sleep, and are resistant to magic missile and lightning. This is, very very weird. They are wildly powerful compared to their later versions, and the only upshot is that they're readily blinded by light spells. Apparently they go insane with such regularity that they have a dedicated social role to controlling or killing the crazed? Yeah these people are a piece of work.

We get a little setpiece moment here where, essentially, there's a rogue kuo-toa who will offer you a trip across the river for 10g. He only speaks kuo-toa and he'll sicc his giant fish on you if you don't say yes fast enough. In fact, a lot of ink is spilled on this little moment, which in all likelihood will be a brief conversation and some passing of money.

Before you get into the shrine proper, some svirfneblin offer to help you in the shrine if you go halfsies on treasure (with almost that exact wordchoice).

Finally, we end up in the shrine proper, which is keyed so let us enter Keyed Mode ™️

The whole area is lit by glow-in-the-dark lichens, which is a spooky way to reveal the lobster lady idol up on the pyramid

While the party can choose to politely integrate into the crowd and play along, there's lots of little things to harass them into nonconformity. Leeches, horrifying offerings, offerings of increasing amount, having to correctly pronounce nonsense names (Blibdoolpoolp????????), holding a live lobster, it's a good bit.

You can, in fact, visit the goddess, who will give you a boon (if you give an offering) or a geas (if you don't), which also grants you kuo-toa speech and also a mark of loyalty, which is neat. You can also encounter her if you fuck around in the prince's treasure room, so the odds of meeting her are actually pretty good! Note that this is pre-"Kuo-Toa believe their gods into existence" so in this case they are worshipping a (hypothetically) permanent, naturally-occurring deity. Being that this is 1e and she is a she, she is Extremely Naked. She is later called The Mother of Lusts, which is one hell of a title.

If you fail to get the priest-prince when you meet him, he actually has a pretty rock-solid escape plan and will come back with an army. So, probably whack him if possible. I really like when antagonists have the sense to piss off and come back armed, rather than pridefully stand and die. You get the sense that Va-Guulgh is priest-prince because he plans contingencies like this, whereas other Kuo-Toa simply vibe. That being said, the Kuo-Toa are apparently not equipped for a search, so it's pretty easy to ditch them.

Sigh.

We do not have a dramatic declaration of THE END anymore, which is a terrible shame. We instead get a more reasonable "This is the end of the section."

The magic of D2 is more in the play and less in the overview. Like, look at this map: