#but he is a loser. that's like the most important core aspect of his story he is a 1.81m tall beanstalk of anxiety and he's got no rizz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

finally found the time to draw beckett :^) he's one of the first (sort of) successful test subjects of arasaka's serpent projects but he doesn't go there anymore. got adopted into vulture's mercenary roster instead and is now one of her bloodhounds :^)

taglist (opt in/out)

@velocitic, @deadrlngers, @euryalex, @ordinarymaine, @mojaves;

@shellibisshe, @dickytwister, @mnwlk, @rindemption, @ncytiri;

@calenhads, @noirapocalypto, @florbelles, @radioactiveshitstorm, @strafethesesinners;

@fashionablyfyrdraaca, @radioactive-synth, @katsigian, @estevnys, @elgaravel;

@aezyrraeshh, @carlosoliveiraa, @userbatwoman

#cp2077#cyberpunk 2077#art#art:beckett#nuclearocs#nuclearart#his jaw and neck are very scarred and the cybernetic lines there are like. gaps. because he has a built-in cybernetic maw#that can open all the way down to his neck :] it's his special trick that he uses when in arasaka mode to rip people's heads off#but he is a loser. that's like the most important core aspect of his story he is a 1.81m tall beanstalk of anxiety and he's got no rizz#he lives off mushy ramen noodles and applesauce because there's not much else he can eat with the cybermaw#there's this vague smell of blood hanging around him at all times and he always looks like he can start crying every moment#but he's one of vulture's top mercenaries (called bloodhounds) and he's like. her trophy. her most specialest little boy#loyal to a fault and he will do anything for her and he is unstoppable in combat. but also like he cries during sex#not that he gets laid a lot like that doesn't happen until after he meets frankie and reunites with andrew#before that? all he's got is his hands. but he doesn't do that because what if he gets scared. he'll cry

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to go on a spiel about character design and my friends are losers who don’t validate me with heart reactions in discord.

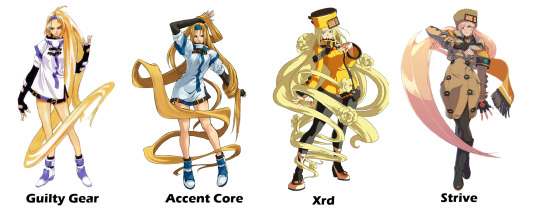

While I’m not the biggest Zato fan I do think his character design is a solid good one. And I want to talk about why I think it is good. You don’t usually get a character design static for 25 years without it being good in some capacity.

When discussing character its important to acknowledge what its made for. In the case of fighting games, subtlety is usually thrown out the window in favor of making the character design essentially a pitch for the game or that character’s story. While also emphasizing the important aspects of a characters movement to allow for readability. Zato is interesting in that he isn't the main pitch for the space he occupies in Guilty Gear, as a puppet character, he isnt the main selling point of the design or the main aspect of movement, Eddie is.

Zato has a really simple design as a result of all of that, especially by guilty gear standards. The core elements of his design are a black bodysuit that exposes the biceps with a black and red belt around tied around his head. The primary color scheme of Zato is black with red highlights, which ties him visually to his shadow monster Eddie. Which can in turn be read as a visual tie to the “shadowy nature” of his work within the assassins guild if you want to go that direction.

Starting off, the cut out of the biceps helps from a design standpoint by acting as a color break and to show off his build. Zato used to be more androgynous and that helped to excentuate that fact, and now that he is jacked it helps to imply strength and capability even without Eddie. From a gameplay perspective it also emphasizes Zato's arms as a point of interest, as his hand movements are the thing that directs Eddies' movements. So having the biceps stand out is important in that way to keep the design from being a monotone block and to improve readability in gameplay.

There are also little bits in his design, like his belt and his shoes that help the design as well. The belt he wears properly is a necessary detail because it provides a break in the shape language of the character. That keeps his torso/lower body design from being boring as a plain black bodysuit. How boring that can be for his design I think is shown well in his original design from GG1. Then, his shoes having a red tassel (or more red in their design from Xrd) helps as another point of interest that can draw the eye but not as strongly as other aspects of the design since they are accent colors here. The shoes Zato wears have red on them in most incarnation, which helps to draw attention to the floor where Eddie is when not active.

The main point of interest in Zato’s design itself is the belt he wears around his head. First, people look at faces first as a general rule, and Zato’s hair and blindfold help to draw attention even more. I think the fact Zato wears a belt and not a normal blindfold adds an extra degree of intention behind the design that a regular blindfold doesn't. While a blindfold usually symbolizes blindness of some kind. The fact he wears a belt, and the fact it’s buckled on top of that, shows a more concrete purpose in it. By using a belt instead of a blindfold, I think it’s shows that he has a greater intention and process behind why he is blinded than just ignorance that a blindfold is normally symbolic of. The intention idea I have also ties into his story of sacrificing his eyes to be able to use Eddie. The belt also acts as another color break from his skin tone that evens out the color of the design which is primarily black on bottom but has more of his skin tone in his torso and head. The red around the blindfold acts as another visual tie to Eddie who is usually shown to have a red outline to him, I also think it could be seen to imply blood as another call back to losing his eyes.

The final major component of Zato's design is his hair, which is a bright blonde that acts as a major contrast to the rest of his design. I think his hair plays an important role in tying him visually to Milia Rage, the most important character in his lore. Especially since in earlier games their outfits were more diametrically opposed with hers favoring white and blue more. I think the similarity in hair is a way of providing a visual link between them, with their opposing color schemes reflecting their Love/hate relationship.

Anyway, I'm not a huge Zato fan, he’s alright in my books. However, on my way home from work I just felt a need to talk about character design and he came to mind. Some of it is probably a stretch but it made some degree of sense to me even in those. The belt over the eyes thing really just felt like me repeating “a belt implies intention more than a blindfold” in slightly different ways and I didn’t structure this super well, but it is what it is and I don’t care that much.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

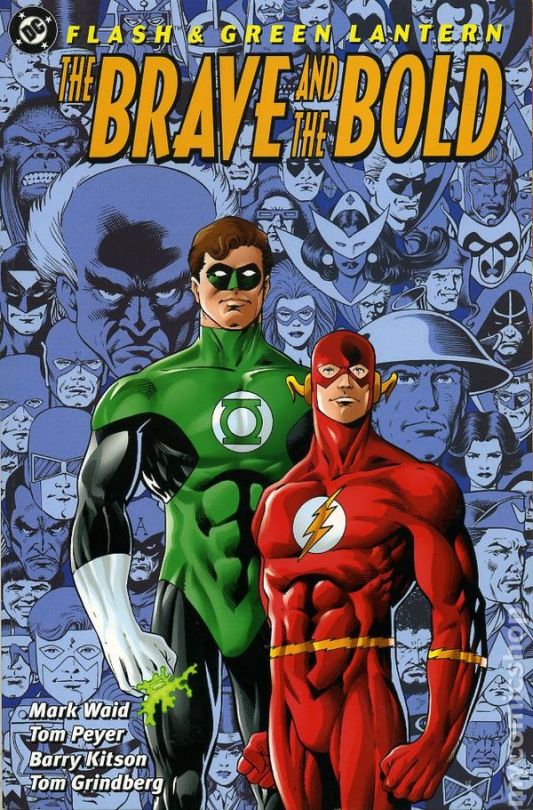

god I reread blackest night and I totally forgot how much they lean into the whole military/cop aspect of it all. It's so annoying to me bc it's like the default interpretation of the gl corps bc of Geoff Johns but I feel like it didn't have to be? Like yes the gls are intergalactic protectors or whatever but key word. Intergalactic! They don't have to be they EXACT SAME as the ones on earth. Comparing them to cops every 5 minutes even by the characters themselves is so annoying. Same thing w military backgrounds like changing john's background from architect to marine, or making it a focal point of Hal's backstory when he got dishonourably discharged after a few years and joined for the sake of flying. I remember reading a post about how once a characters original creators die the chance of having an interpretation be what they wanted gets smaller and smaller as time goes on. There really is so many ways to interpret a character or characters and even tho it is what it is now and even tho I'm probably delusional/reading too much into it I wish the gls didn't have to be this way or be like this to this extent

It's cause Geoff Johns is one of the worst writers I've ever had to suffer through. He's lazy and he's a bootlicker and it's boring.

The idea of GLs being cops is atrocious. They were more like park rangers.

Guy Gardner becoming a cop is the worst thing I've ever read and takes away every important aspect of his character and it disgusts me.

Genuinely DC comics is so fucking unbearable for me because of how blatantly stupid they are. Dude bros whine keep politics out of comics then cheer when someone is pro cop. Like dumbass you're just a right wing loser.

Anyways yeah Green Lanterns sigh the stories aren't even good. They kept nothing about the core of the Green Lantern Corps or the Lanterns themselves. It's just a shallow reading of it.

I've said this but newer comics feel like they stop when you close the book. They've decided their reader is dumb and has to be told every thing so no progression happens off panel. Every character interaction is hollow because we know they don't talk off panel or they'd have painstakingly wrote it out in a thought bubble.

So for such hollow characters where most of them are now violent brutes who fight crime to punch people it only makes sense they thought cop and military. Like it's just sad at this point. And the authors have no balls either. Like I bet you could tell Tom Taylor he's a talentless bitch and he'd piss himself.

Lol this is getting so aggressive but I genuinely hate the direction the Green Lanterns were taken in because I love them so much.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

obviously i can tell you love richie/eddie and the story and all (and i do too) but i was genuinely wondering, what's your opinion on the homophobia of the story, if you think there is any at all? do you think this still falls under bury your gays? is this good representation?

this is a very good question! i love unpacking stuff like this so thanks for sending it. but really, there’s no straightforward answer i can give you. i think there are far too many gay love stories that end in tragedy, the bury your gays trope is old and exhausting, and no, this isn’t the height of representation. this being said, you can also see those tragic stories as a frank, albeit upsetting, confrontation of the reality of homophobia, something that shouldn’t be glossed over. but in that case, is this a story catered to gay people or is it a story catered to straight people, to make homophobes understand and/or to let allies pat themselves on the back for acknowledging it? would it have been better for them to leave richie and/or eddie as purely subtextual and therefore dodge the tragic ending for the gay couple or is it good that they finally just admitted that this is a gay relationship? how about the adrian scene? should it have been left out because it’s too graphic? or is it important that it’s left in because it raises a magnifying glass on homophobia? honestly, i don’t think there’s a simple answer to any of those questions. if it were up to me, i would say the ideal way to handle it would be to keep in the adrian scene and then let eddie live in the end and have him and richie get their happy ending together in the same way ben and beverly do. it would show gay love overcoming the previously depicted homophobic violence that has been encouraged and enflamed by pennywise. because at it’s core, the story is supposed to be about the good triumphing over evil, and it’s truly is upsetting that only the straight characters get their chance at a happy ending while the gay characters have it ripped away from them. but i know that that would’ve been a huge change from the book and it was highly unlikely to get that.

all of this being said, this is a highly anticipated major motion picture based on an iconic story that people have known for over 30 years. these are characters people have grown to love over the years. this is a horror movie, which is a genre that very very rarely has gay representation and when it does, it’s not often sympathetic. this is a story that has the themes of fear, shame, bigotry, trauma, and repression. as well as self acceptance, bravery, individuality, and love. the decision to make one or more of the losers gay not only fits in perfectly with the story but adds to it. they’ve made richie’s feelings for eddie and his struggle with his sexuality a core part of the movie and it’s what makes several of the most emotional moments of the film so poignant. straight men who have been projecting on richie for his Sarcastic Vulgar Funny Guy persona are gonna have to deal with the fact that he’s gay and that his humor is a coping mechanism to avoid dealing with his insecurities rooted in his sexuality. one of the most important relationships between two of the main characters in this film is a gay love story and that was a power move that i’m sure as hell gonna be happy about even though i know there’s plenty of aspects to all of this that i can criticize. so in conclusion, is it good gay rep? hell if i know. but i’m gonna be in the theater mentally yelling GAY RIGHTS the whole time anyway.

#reddie#it chap 2 spoilers#it chapter 2 spoilers#richie x eddie#it chapter two#it films#long post#Anonymous

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Netflix’s Death Note: [Personal] Review

Director Adam Wingard's Death Note is basically a Final Destination bootleg with the manga's name. It's flat, unnecessarily gory, and incoherent. Its promising moments are completely swept under the rug of its overall disjointed narrative and out-of-character acting.

I love Death Note. It's one of my all-time favorite series. I even have merch from my weaaboo days (haha). But I've also never been a fan of manga adaptations–not even anime (to an extent; I'm looking at you, Full Metal Alchemist and Shugo Chara season 3), and especially not of Western movies. Hollywood has YET to produce a decent manga adaptation, and this one is right up there with M. Night's The Last Airbender.

I'm not sure how these directors do their research, but by and large their end products wind up looking like their "research" is pretty much just looking up the plot on Wikipedia and making what they will of that. Netflix's DN is the absolute barebones of the wonderful masterpiece that is Ohba and Obata's Death Note. It's even more disappointing if you think about the fact that Death Note's "absolute barebones" is still a good material to work with, and we STILL end up with this bastardization.

First of all, I, at least, have no problem with the setting. To begin with, Netflix did say this was an Americanized version of the original. It makes sense that they'd change the names, considering this is set in Seattle. I did appreciate that 'Mia Sutton' is not too far from 'Misa Amane' as far as the composite letter are concerned lol. My biggest problem was the characters themselves, but I'll focus on 2 to keep this from being indecently long.

Light Turner is not supposed to be Timmy Turner's older, emo brother and is an average kid whom no one understands and happens to be good at Math and doing other people's homework. The core of Light's character is his PERFECTION. He is so far above average that he's completely detached from the rest of the world. That god complex was the entire reason he even took and managed to assume a 'god' character. It's literally the core of Death Note. Light is supposed to be the perfect son, perfect student, perfect citizen. Everyone loves him and looks up to him. And HE knows that. People don't need to tell him; he knows for himself he is BETTER than others. That's how Kira came to be in the first place.

Netflix's Light Turner is a wimpy loser with absolutely no depth as a character. He is completely one dimensional. He responds to dark and violent situations with darkness and violence. He is bullied so he fights back. His mother is murdered so he kills the murderer. It's a completely overused narrative that puts the essence of Light Yagami, antihero extraordinaire, straight into the chopping block.

From the get-go, his character is completely wrong. He is introduced as a nerdy kid who earns lunch money by doing other kids' homework. He has zero charisma. He's at the bottom of the food chain. He has absolutely nothing of what it takes to become the god that is Kira. The way that Light Turner was written would never have let him become anything larger than life; it just made him a vindictive bully who happened to be able to kill.

(A very dangerous combination–but for all the wrong reasons.)

Which just obliterates the central theme of Death Note altogether, and throws out the window the very foundation of what made the original work.

Second, this film is unnecessarily gory. Sure, a certain degree of violence is expected when it comes to murder, but Wingard just made this entire movie a B-rated slasher film with his slow-motion death scenes–something he just PACKS the whole movie with and spotlights on like it's the most important aspect of the story when it's totally secondary (if not completely an afterthought) in the original.

It's not even realistic. Light sees a BULLY (not a criminal; just a run-of-the-mill playground bully) antagonizing a schoolmate, he's handed a murder weapon for a TEST RUN, and he immediately, without a shadow of a doubt, writes 'decapitation' as the method of death? He chooses something that is exceedingly difficult, unnatural, and very, very specific for the first time he's trying to kill someone? He doesn't even UNDERSTAND what's going on; he's just had a massive Poltergeist experience. How was it possible for him to suddenly have enough presence of mind to write down an oddly specific method of death for someone who isn't even evil, just mean? That doesn't bode very well for Light as a person, let alone someone who's about to play god.

Throughout the movie, Light visibly struggles with his actions. He has no certainty. He kills with the Death Note but he lacks the inherent motivation for it; he only does it because he has to. Nothing about the characterization of Light Turner remotely suggested that he has what it takes to rule the world, as what he is essentially doing when he dictates who lives or dies (or tells your story lol). But then–all of a sudden, 5 minutes to the end of the movie and he explains this elaborate scheme where he undoes Mia killing him and transfers the ownership of the notebook back to him and basically just manipulated space and time so suit his needs.

That is a completely Light YAGAMI thing to do (and something he HAS actually done numerous times in the original). Nothing about Light TURNER's character and actions suggested he was capable of that. How convenient that 2 minutes before the police gets to him, he suddenly taps into his inner high-functioning psychopath and concocts an über-complicated plan to not die but kill 3 people and destroy one theme park along the way.

Where did that inner 'HIGH FUNCTIONING' part come from? Nearly two hours to have shown that Light's brilliant mind goes beyond solving Calculus problems and thinking up oddly particular methods of dying, and you choose the last five minutes to cram that in.

How very high school.

But enough about Light. Now we go to another important character–L. Considering that these 2 are the only ones they retain from the original (excepting Ryuk, but that's another point). L is one of the most brilliant minds in the world, but instead the movie showed him as nothing more than a weirdo that throws tantrums and only needs the FLIMSIEST of proofs to say he "knows" and he's "right".

The original L does operate entirely on the gut feeling that Light is Kira, but he sets out to prove that. To him, nothing is ever damning enough and he won't settle for anything less than seeing Light actually murder someone right before L's very eyes. Movie L suddenly "just knows". Nothing about his actions suggests that he has the means to prove that Light is Kira; if anything, he's trying to make it so that things DO go with his conclusion, whether or not it's actually true. The real L is nothing like that. He backed down when his proofs didn't go with his conclusions. L believes in justice, first and foremost. He's almost childlike in his black-and-white convictions (I have a screenshot of this panel, so my receipts are in place). This L just doesn't capture that innocence.

By itself, the movie isn't THAT bad. It only becomes a terrible crapfest when you have the original to compare it with. Netflix's Death Note can stand alone as a slasher/horror/thriller film to Netflix and chill with if you are holding it to itself, but never make the mistake of reading/watching the original brilliance that is Ohba and Obata's Death Note first.

I do have a real concern with the keeping of the name "Kira". Kira is just the Japanese pronunciation of "killer". Japanese people literally were calling Light, "Killer". Why did Wingard keep the Jap pronunciation? What purpose did it serve other than that 5-second line where L says it was to mislead investigation to thinking Light was Japanese? Why is there even a need for that? Was that supposed to be a nod to the Japanese root of Death Note? It may have been a pure intention on the director's part, though, but it was unnecessary, if not even reeking of whitewashing–but I'd digress and hope for the best.

1 note

·

View note

Text

@siryamsalot ‘imagine FMA but Reigen is there to be an adult figure. how would the plot change’

listen you have no idea what you just unleashed bc since putting that post in the queue I’ve actually thought about this a LOT and the conclusion I’ve come to is that Reigen and FMA are almost entirely incompatible without changing some fundamental aspect of at least one of the two.

The thing is that at least one of Reigen’s fundamental roles in the story is incompatible with FMA. Reigen is a character who exists for two primary reasons: a) to be the mentor character for Mob, and b) to the the moral focal point for the adults in the MP100 series. While the first role could be adapted for FMA, the second one is attached to a theme that FMA does not have, and is therefore very difficult to adapt to that story.

While MP100 and FMA do share some themes, most notably the importance of trust and interpersonal relationships, they handle their child protagonists very differently in a way that makes it very hard to merge the two universes. FMA does acknowledge that Ed is a child, and it is implicitly acknowledged that him being in the military is kind of fucked up, but it doesn’t linger on those things because its focus is ultimately not on deconstructing the Shounen trope of having children fight (in the wars of) adults. It’s simply not all that interested in examining whether the adults should be fighting Ed, and how fighting adults would affect Ed’s psyche. It’s not one of FMA’s core themes.

MP100, on the other hand, has a core theme of ��adult responsibility’, which radically changes the way it treats its child protagonist and the adults around him. MP100, at its core, is about the importance of interpersonal relationships, the importance of kindness and compassion, and growing up. The ‘growing up’ part is where the theme of ‘adult responsibility’ comes in, because while MP100 essentially is a coming of age story for Mob, pretty much everyone else also has a lot of growing up to do, including the adults. But the adults who have failed to ‘grow up’ are treated a lot more harshly by the narrative, and rightly so, because if you haven’t really grown up as a kid, that’s pretty much normal and mostly harmless. However, adults have responsibilities that kids don’t and shouldn’t have, and if they fail to accept those responsibilities because they’re too stuck in their childish ways to do so, people will get hurt - children will get hurt.

One of the main things that MP100 considers to be an adult’s responsibility is the well-being of any and all children in their care, and even those that aren’t in their care, tbh. This is where Reigen comes in.

Reigen is by no means exempt from an arc where he learns to grow up, nor is he a perfect person with no issues - in fact, MP100 makes a point to show that nobody is ever really done growing, and that nobody is without their flaws, but that everyone can strive to be a good person, and that includes Reigen. So while Reigen definitely has immature habits and character flaws, one thing he is consistently good at is taking responsibility for the children in his care. Obviously, he can’t prevent all harm that comes to them, but he consistently calls adults out for fighting them, and often puts himself in the line of danger even though he has no real way of fighting the threat just because he realizes that Mob - our 14-year-old protag in Reigen’s care - shouldn’t have to. Whether he actually succeeds in this depends on the threat he faces, but he does try, and that’s really what matters in the end.

Reigen is also more mature than many of the other adults in the series in different ways; he has a job that is mostly legal (aside from whatever wage and child labour laws he’s definitely breaking by employing Mob), he has his own apartment, he maintains fire insurance for his office, and he is generally a pretty functional member of society. Again, not saying he has his shit together entirely (he’s a perpetual liar with a severe difficulty of making and maintaining personal relationships, he’s a conman, he employs/has employed a child for very little financial compensation to do like 90% of the heavy lifting in his job), but compared to most of the other adults in the series? Yeah, he’s an example of a good, functional adult.

And that’s kind of his primary role in the story; to be a contrast to and moral focal point for the other adults in the series. All the other adults are basically standard Shounen characters, and have no qualms fighting children and doing shit like trying to take over the world, but then Reigen storms onto the scene and puts into perspective just how fucking ridiculous it is. Even when he doesn’t make them see himself just how stupid they’re being, Reigen’s mere presence is enough for the audience to be reminded that all this Shounen nonsense would be incredibly dumb irl, and that any adult who buys into it is a childish loser.

This is why you have a bunch of people joking about how Reigen is basically just a normal dude who got dragged into a Shounen story; Reigen breaks the unwritten rule that you don’t point out the Shounen conventions, and you definitely don’t point out that the child protag should probably not be fighting adults, and that adults who fight children and do stuff like try to take over the world are fucking losers. And that’s one of his primary roles in the story.

So putting him in a Shounen like FMA, which mostly lets those Shounen principles go unexamined, is practically impossible bc his entire character is designed to poke holes in the things that you’re not supposed to question.

So if you plopped Reigen in FMA, you’d either have to a) change Reigen’s character to remove the ways in which he is a typical responsible adult, including his protectiveness over kids, which would reduce his likability by at least 90%, b) change FMA’s universe to include similar themes as MP100, which is gonna take some work bc it’s just really not compatible with the save-the-world plot it has or the general universe its created for that matter, or c) accept that Reigen’s presence is going to make your audience question the ethical implications of child soldiers more than FMA already will and just accept your story will be dark as shit now.

That said, I think you could make a decent MP100 FMA AU with Reigen as long as you either a) ditched FMA’s overarching plot (which would help anyway bc tbh Mob is just a much more passive protag than Ed, and Ed’s pro-active-ness was really what drove the story), or b) made Reigen an Izumi-like mentor character who isn’t present for the majority of the story, but when he IS there he’s basically doing nothing but trying to keep Mob (and Ritsu) save. But I don’t think you could make him a deutagorist to Mob in a straight FMA universe because there’s just no fucking way he’d let Mob join the fucking military if he could physically help it, and if Mob doesn’t join the military the FMA plot wouldn’t happen, so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

TL;DR Reigen would literally break FMA’s universe.

#for the record this isn't here to shut down anyone's aus and neither was the original post really#it's just that personally for me the appeal of au's is seeing how characters would change if you changed the world around them#but reigen is just one of those characters whose primary redeeming character trait is that he's a responsible adult towards children#and if you take that away from him (which you'd kinda have to do if you wanna put him in roy's role) he'd just be a fucking dickhead#i'm not saying you COULDN'T manage it i just really have no idea how you'd do it#and i definitely have no idea how you'd do it in a way that satisifies me#my posts#reigen arataka#mp100#fma

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why You Shouldn't Let An English Teacher See Movies: a reaction post of IT:Chapter 2

Okay, so I finally saw IT Chapter 2, and I have some thoughts. Some of these thoughts might rub people the wrong way, which is okay, but be warned that I'm not going to hold back here.

As a whole, let me preface by saying that I loved this movie. I will go to see it 3 more times, and I will enjoy every moment. However, objectively… this is not a film that I can recommend to people as a “great film” artistically speaking. Is it fun and Good™? Yes. Did I enjoy it immensely? Yes. Were there some very odd and disruptive writing/direction choices? Yeah. This isn’t a masterpiece, as fantastic as I personally felt it was, and honestly I do not think it topped Chapter 1 in terms of flow, total presentation, or scriptwriting.

I’m going to break down my thoughts by category:

1. Story elements

2. Visuals & Horror

3. Tone

Starting with Story Elements:

I am incredibly torn on this. I LOVED aspects of this film, and was wildly confused by others. As a whole, I think the film began strong.

The re-introductions to the characters were fantastic, though taking the “historian” thing from Mike in Chapter 1 definitely made Chapter 2 weak in regards to his characterization. He’s a hard character to get right, but it honestly feels a little like they didn’t try, and just used him to progress the story. I could continue, but that is a whole separate Mike Essay. Bev, Ben, Richie, and Eddie were all fantastic. Eddie in particular was taken in a slightly more aggressive angle than traditional for his character, but it worked very well with the way he was established in Chapter 1, thanks to Jack’s interpretation. Bill was a little bit weaker in some ways, but still at his core Bill Denbrough. I unapologetically LOVE adult Stan, and only regret that due to the story, we don’t get to experience him as much as he deserves in the film.

The return to Derry was great, and I still think that the group dynamics are what make this story shine. 90% of what I loved so much in Chapter 1 was the group dynamics, and they are here in SPADES. The group makes sense together, and the cast did a great job, though Eddie’s constant repetition of the word “fuck” seemed a little unnecessary after the second time in the restaurant scene. However, one thing I think the miniseries did better is establish them as “the lucky seven” - they’re not just the Losers Club; they’re held together by fate, and there’s definitely some supernatural elements to that which are not present in the films, weakening their group connection. This is shown most strongly in their moments of conflict in Chapter 2, especially when they want to leave, because their draw to each other doesn’t seem to be present, at least not in the same capacity. It seems weird to feel let down by this considering my next point, but it is what it is.

Some may disagree here, but… I really dislike the decision to include the ritual of Chud in the movie. I disliked it in the book as well, as I think that it unnecessarily complicates things and turns this horror story into a surreal sci-fi story in a way that doesn’t always mesh well. King does both sci-fi and horror well, but I’ve always felt the crossover in IT was off somehow. Also, the lack of connection with this to the first film makes the ritual of Chud seem even weirder in Chapter 2. Mike’s characterization with this gets… odd… and its inclusion is very confusing. I actually said “what the hell are they doing” in theaters when Mike introduces this with Bill. That’s how weird it was for me. My biggest problem was that it makes Chapter 2 a sharp departure from Chapter 1, and failing to achieve the cohesion that the miniseries had is a huge downer for me, considering that the IT reboot is an improvement to the miniseries in so many other ways.

In comparison to the book and miniseries, I think that it was a bad choice to leave out Audra, as it was good closure for the Billverly plotline. Bill and Bev even kiss in Chapter 2 - and then it is promptly forgotten. I’m not necessarily looking for conflict, but Audra was a huge motivator for Bill, and it was much less significant to have his driving force be this random kid that reminds him of Georgie. I get it, but Audra helps show how Bill has grown more strongly and pushes him forward after the final battle. I also wanted a cinematic parallel between Audra and Bev in the sewers and was really disappointed that I didn't get it. I have similar feelings about Tom - yes, Bev obviously leaves him for Ben, but Tom had a huge impact on Bev and her growth. Leaving him out weakens her personal story.

I’m not going to say much about Henry, but the scene where he pops out of the sewers is FANTASTIC. I absolutely did not expect to get that scene (I figured we’d just pop in on him in the hospital), but was glad we did. However, this lost its impact the longer we went on; he was relevant for all of one (1) stabbing of one (1) Edward Kaspbrak, and then died without even putting Mike in the hospital like he was supposed to. A waste of his character.

There are other positives. The connection Adrian and Richie’s stories are great, and I think Richie’s moments of reveal are very well handled. I just wish the Adrian/Eddie parallels had been highlighted as well. Richie and Eddie are fantastic together, and Bev and Richie are also sweet as hell. Besties for the resties, man. In general, I think Richie’s relationship with the Losers is the strongest writing in terms of group dynamics. Putting aside his feelings for Eddie - which do a fantastic job of fleshing him out and showing how multifaceted his character is - he is the one Loser who has strong ties to every other character. Bev’s relationships with Mike and Eddie are weak, Ben’s most relevant relationship is to Beverly, Bill’s most relevant relationship is Mike - you see where I’m going with this. Only Richie’s writing showed the importance of all his group relationships, though some were stronger than others.

Almost every individual scene with the Losers and Pennywise are very enjoyable. The moments where their personal motivations and fears shine are truly the best in the film. While there were some design issues that disappointed me in terms of IT terrorizing them, their stories are great - the apartment scene with Beverly is still poignant, and Bill’s revelation about the day of Georgie’s death made me a little emotional. I’ve already mentioned this in general terms, but the arcade scene with Richie is fantastic.

As a whole, there is a lot of love here, and so much to enjoy. The script writers and the director worked hard on this film, and they tried to do a lot with it - just maybe too much, which caused problems with flow and tone as a whole.

Visuals & Horror

I love horror - I could go on all day about how it’s the best genre. As such, I have a lot of feelings about the horror elements in this film.

I already mentioned how the ritual of Chud/Sci-Fi elements weaken the horror - in truth, the horror elements were already weak. As a result, sci-fi elements distract from what already has flaws. There are two major categories for this discussion: subtlety and design.

In terms of subtlety, a majority of Chapter 2 was basically hitting you over the head with a Pennywise-shaped hammer. There were jumpscares everywhere, and they were rarely impactful ones. How many times did we get a “Pennywise chomps down on somebody” moment? I was totally engrossed in Adrian’s scene at the beginning, but when Pennywise just takes a bite out of him and it ends, I was honestly disappointed. I do realize this is book canon, but there is something about the presentation in the book - the precise moving of Adrian’s arm, the bite, the smile, the cracking of his ribs - that is dulled in the movie for a lack of a better term. There is just something about this death that fails to hit home. Maybe it’s because Pennywise is more or less out in the open, or maybe because in the book, the bullies see It, too, making it a surreal moment that no one believed except those who were there.

As a whole, the movie has plenty of gore but little suspense. I think I had more interest the less I knew about how exactly people died. Eventually you get sick of the chomping - the unknown is more frightening than a monster with a predictable attack pattern. The missing kids. Betty Ripsom’s shoe and lack of explanation. Patrick’s fade to black. These things made Chapter 1 unsettling, but scenes like Victoria’s death had no other elements other than being bitten to death by Penywise, and that was predictable.

For an example of what could have been in terms of subtlety, I can honestly say that I was more creeped out by “Mrs. Kersh” slinking around in the background of Beverly’s old apartment than I was by the old woman monster. For what it's worth, the way these monsters move is INCREDIBLE, especially so the more humanoid they are. I love the body language and movements. The earliest example is the headless boy in Chapter 1; the jerking limbs really emphasize their inhumanity, and it still works in this film (Mrs. Kersh at the end of the hall, Betty Ripsom’s legs, etc). This, with the use of humans and their subtle shift to the unnatural in the films, was much stronger than the larger monsters in Chapter 2.

Another strength is the background details that you might miss. The librarian staring at Ben as he reads about the Ironworks explosion in Chapter 1 is a great example of this, as is Mrs. Kersh peeking her head out of the kitchen in Chapter 2. I would have rather had more small scares like this, rather than the reliance on jumpscares. The pomeranian monster behind the “Not Scary At All” door is essentially just that, and I was WILDLY unimpressed by it.

Returning to the focus of the film, Pennywise the clown is a great villain, but a lot of Its appeal is that It shifts into whatever scares you most. In the first film, this is done well - the painting lady, the leper, the headless boy, and even the way it shifts in the battle at the end. The strength in these forms is that you never know what to expect - and neither do the Losers. Each new nightmare looks and behaves differently. The flute dropping from the painting lady’s hands to announce her presence, the dropped eggs in the library scene… everything about the leper. Even the miniseries did this variety well (the werewolf, the shower scene with Eddie, Mrs. Kersh, etc)

Yet, in part 2, we get… two extra monsters. Which is fair - we already have plenty of material - but they both have the same style of warped features and aesthetic. I think creepy naked old Mrs. Kersh would have been a more disturbing visual than old lady monster turned out to be. Sometimes less is more. Clowns are creepy because they have almost-not-quite-human features… the same can be said of effective monsters (look at the leper, for example, or the painting lady).

Pennywise in general and Its overreliance on Its clown persona weakens the effect. Eventually, Its presence becomes “oh, there’s the clown again,” especially considering that Its attack pattern has become so predictable. Is It going to drag me into the darkness? Is It going to manipulate me into hurting my friends? Is It going to do some other scary thing to me? No, he’s going to take a bite out of me. Not awesome, but certainly not the Pennywise of the novel or even of the miniseries, whose horror came from the fact that no one knew what happened when you disappeared - or when parts of you reappeared.

There were too many instances where the horror was all about jumpscares and theatrics. Pennywise is all about theatrics, I know, but It went from eldritch horror to dramatic murder clown in this film. In the book, Pennywise is extra as hell, so I wouldn’t be angry if that was the angle taken for the films - however, that is not what was established in Chapter 1, and isn’t actually what is achieved in Chapter 2. If we are going for a more serious, darker tone for Pennywise, I would prefer the eldritch horror we saw more strongly in Chapter 1.

Tone

This is the hardest category to explain well, because a lot of this is my personal impression of the film, but I’ll do my best. As a whole, the movie does not flow well, especially connected to Chapter 1, and this is largely because of tone. Some scenes shift too abruptly or push too hard, and I feel as though the writers were trying to capture the same charm and attitude that Chapter 1 achieved with the kids, but struggled because they aren’t kids anymore. The balance between gritty horror and charm is harder with adults, but this is something the miniseries excelled at compared to Chapter 2. In the miniseries, you never feel like you’re watching a new film when it switches to the present day with the adults. In IT Chapter 2, though the movie and story are meant to be a continuation, it feels more distant, like a sequel that doesn’t quite achieve the same mood.

I’ve said that the group dynamics of the Losers really shines in these films - however, it’s also a major problem in Chapter 2, because there are several times where the writers sacrificed the integrity and tone of a scene to fit in some banter. I love the banter, okay. I’m all about it. The banter in the IT movies is my favorite banter that I’ve seen in a fictional friend group, and yes, I’m including Stranger Things and classics like The Breakfast Club or the Goonies. However, when it’s ruining an otherwise impactful scene, it feels wasteful and disruptive.

A good example is the scene with Richie and Eddie at the doors in the caves. This scene is fantastic - it’s funny without being a gag, and it showcases the brilliance of RichieandEddie. However - and this is a big however - every other Loser’s individual scene is dramatic and dark - tonally appropriate. Richie and Eddie, however, have their moment melding humor with some jumpscares, and though the scene is great on paper, it makes no damn sense compared to the tone of the rest of the damn sequence. There is no logical room for comedic relief here, and it was jarring, no matter how much I enjoyed the scene itself. Tonally, Richie’s one-liners in Chapter 1 made more sense, and the script of Chapter 1 did a much better job ensuring that those tiny breaks in tension do not disrupt the scene or atmosphere. I cannot say that about certain elements in Chapter 2.

The Losers work very well together, but they also have a tendency to get chaotic enough to break the atmosphere. In the book, there is a lot of quiet horror amongst the Losers Club that is disrupted in Chapter 2 by the multiple scenes where they just scream over each other during crucial moments (such as the scene in Jade of the Orient). The quiet fear and understanding amongst the Lucky Seven that made them such a dynamic group of protagonists just doesn't exist here. Every quiet moment is a moment for arguing or freaking out here, and it got tiring, especially when we went right back to individual reflection and exploration after. I use the term “quiet” here quite a bit, but I’m not sure how else to express the atmosphere I’m talking about. Hopefully the point gets across.

This may just be personal preference - I really enjoy subtle horror, as I’ve said. The moments where the Losers watch and take in the terror as it unfolds are important moments and are lacking in Chapter 2. I can’t empathize with the screaming and freaking out, but the dawning horror and realization of what’s happening puts me right in their shoes. Beverly’s slow realization when she’s staring at the picture of “Mrs. Kersh” and her “father” is a moment like this, to put it in context.

Even more so than the Losers’ attitudes is the lack of the “dawning horror” vibe in the film at large. It is not meant to be an action film, and yet Chapter 2 is constantly go-going. The action is in places more akin to a slasher than the slower supernatural horror this story is meant to be. Chapter 1, with its slow reveals and strengthening group dynamics, hit the intended mood better, and seems further separated from Chapter 2 as a result.

Chapter 1 did a great job with balance - it knew when it was appropriate for the funnies, and how to shift that into the horror elements seamlessly. It also did a great job throwing in Richie’s one liners without ruining the balance of the scene, but Chapter 2 had several instances where it took those quick Richie moments and turns the focus entirely on him, breaking up scenes in a jarring way. An even more disruptive example is the “Richie said it best last time” bit before they entered Neibolt. The entire scene shut down for Richie’s moment, and it ruined the suspense of what could have been a really nice parallel to Chapter 1. We didn’t need the tension broken in many of these instances, and it was difficult to go back and forth. The focus on Richie is because of the positive fan response to his character, which is well deserved in my opinion. However, this could have been done better.

Tonally, Pennywise’s script also came on too strong. The Pennywise we know and love is a lurker, manipulating humans and taking other forms rather than doing all the dirty work directly. Chapter 2 has moments of this, but more often has Pennywise as an aggressively taunting antagonist. It becomes loud and exaggerated. Part of this can be attributed to rising tension as the Losers return to finish It off, but Its dialogue is hammier than I expected. It’s become almost petty - and not to needle at the Losers, but more because It’s bitter and childish. I don’t know if it’s too much to use the term “eldritch horror” again, but I don’t know how else to describe what we were set up for with Chapter 1 and let down on in Chapter 2.

As a whole, I felt like the film was stitched together in places. After Chapter 1, I felt that I had just had an experience, but after Chapter 2, I actually looked at my best friend and said “I liked it, but I’m not sure what just happened.”

Let it be clear that I love Chapter 2, and will happily rewatch it many times in the future, but I do think that compared to Chapter 1, it is a far weaker film overall. You can watch them together for a similar experience to the miniseries, but it will be less cohesive and will feel like it fell apart a bit the longer it went on. I don’t fault the writers for this entirely, as the second half of this story is a daunting undertaking, but I think removing the sci-fi elements with the ritual of Chud and tightening down the horror aspects/tone would have made this a stronger continuation of Chapter 1.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

not to sound harsh but tsurune's seiya has always seemed kinda boring and annoying, and kaito seems to be hysterical, not like the regular characters having anger issues/being over emotional(especially after the last ep), and the anime makes absolutely no effort to explain anything behind that kind of behaviour. so i'm wondering how they were portrayed in the novel and whether they were the same ppl they're in the anime. maybe it's just me seeing them that way so sorry in advance

It's okay, Anon. And sorry for taking long to reply. This is a bit complicated to answer.

I'll be honest with you: the anime doesn't make any effort to explain their behavior because there's no reason for it. KyoAni has been showing since the beginning that they're torn between canon and their own original content. It feels like they use mostly their own visions of how the characters should be rather than depicting them for what they really are, and only drop a few hints of canon when they come to a point where they'd be changing the story far too much if they continued pushing original content onto the story. It's inconsistent and many things are left unexplained due to it. Not just about the storyline but also about the characters, who have been reduced to stereotypes of their positions in the line-up. I think this problem is especially prominent in anime!Seiya, so I'll start with Kaito.

I totally agree with you that he's being hysterical in the anime. I think this isn't even up for debate. He literally yells in every episode he appears, orders everyone around as if he's the captain and overall acts prickly in completely uncalled-for moments.

Novel!Kaito isn't like that. He's actually pretty pure-hearted, which is why he gets heated from time to time. If anything, his problem isn't what the anime is trying to sell. It's not that he doesn't care about the rest as long as the results show. Instead, he cares too much about every little detail, and this is where he becomes overbearing. He does long for teammates, yet he fears not reaching the best results with them. But he's rational and observant. He's good at grasping the true nature of people and has sound judgment and intuition, so the conflicts that have him at the center are surprisingly easy to resolve.

This bitch ain't empty; he's too full.

Kaito is also good at taking care of others. He's always doing things for Nanao basically because he's too nice at the core, and he's pretty weak to dealing with the people he acknowledges or is close to. For example, his threats are always empty when they're directed at Masaki, and he always obeys Seiya no matter what his state of mind is. This part of him is actually more important than the anime gave credit for, because of Seiya, specifically. He's always looking after everyone and wears himself out a lot worrying about Minato, and the one who looks after him is normally Kaito.

And while we're at it, I must add that he's... strangely possessive of Seiya. I say strangely because don't know if this is supposed to be a character trait of his or if it's just with Seiya, but so far, he's been the only character who has made Kaito manifest this side of him. It happens fairly often.

Other than this, Kaito is an absolute bow nerd. He's far more knowledgeable than he seems, and the way he stans Masaki is different. It's less obsession and more credibility, I'd say. Kaito is very down to Earth and takes what he learns seriously. He doesn't buy fights with Kirisaki, doesn't get fixated on bow-turning and doesn't yell at every opportunity.

As for Seiya, he's one of the most complex characters in the Tsurune novel, in my opinion. He's extremely serious and calculating, yet he ironically is always making plans for the sake of very sentimental motives. He's got this strong sense of righteousness that often seems to remind him of what's fair, so he burdens himself with things that are sometimes completely unnecessary but are what you'd expect from a person of ridiculously strong morals.

I haven't really seen the anime display this, but Seiya is a great leader. Other than clearly being the most responsible of the group, he also holds authority amongst the members. You'd normally expect this from an outgoing character, but Seiya has a strong sense of presence in the club. When he speaks, they listen.

It's not like this is written in the novel anywhere, but he also strikes me as someone who hates not having the upper hand in any situation. Not exactly that he's a sore loser, because he can stand defeat, since he's a realist who obviously knows that he is humanly imperfect. What he apparently can't handle very well is disadvantage. He can get really petty when feeling offended or devalued in any way, and his words drip with venom whenever he gets angry. The flame of rage in this little bastard burns blue and it gives nasty-ass burns. I think he only loses to Eisuke in that aspect. He lets the salt show when he argued with Minato and through his habit of declaring that he will "deliver punishment" to whoever rubs him on the wrong spot. But even more often than the aforementioned, he lets it show when sassing the hell out of Kaito whenever Kaito hits bull's-eye regarding the shit he tries so hard to hide.

As you can see, they're very different from their animated counterparts. The stereotypes about their character archetypes are sometimes maintained, sometimes turned upside-down, and that's what makes them interesting. (Also, I don't know if you were able to tell that they sort of complement each other, but the author ain't trying to hide it at all.)

I fucking love these kids.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

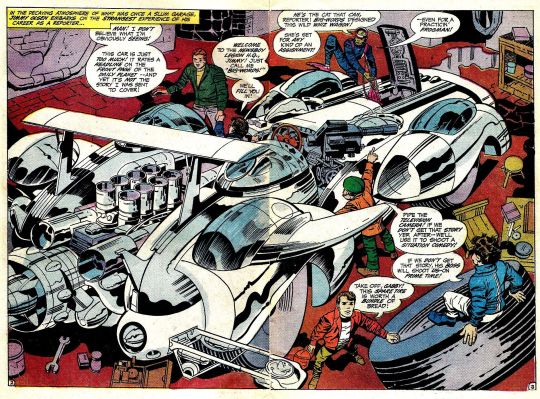

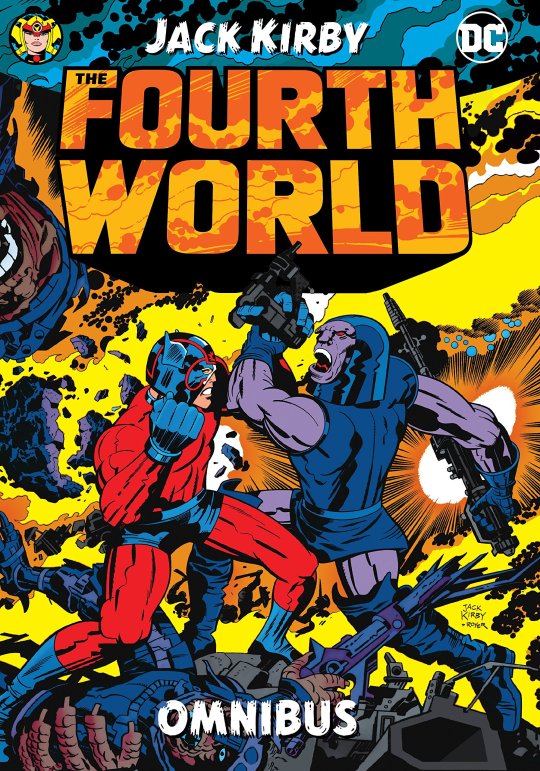

Jimmy Olsen, Superman's Pal, Brings Back the Newsboy Legion!

SUPERMAN’S PAL, JIMMY OLSEN #133 OCTOBER 1970 BY JACK KIRBY, AL PLASTINO AND VINCE COLLETTA

SYNOPSIS (FROM DC WIKIA)

Jimmy Olsen is paired with the new Newsboy Legion, the sons of the original boy heroes plus Flippa-Dippa, a newcomer, to investigate the Wild Area, a strange community outside of Metropolis.

The boys are given a super-vehicle called the Whiz Wagon for transport. When Clark Kent shows concern for Jimmy, Morgan Edge, owner of Galaxy Broadcasting and the new owner of the Daily Planet, secretly orders a criminal organization called Inter-Gang to kill him. But Kent survives the attempt, and later hooks up with Jimmy and the Newsboy Legion in the Wild Area.

The youths have met the Outsiders, a tribe of young people who live in a super-scientific commune called Habitat, and have won leadership of the Outsiders' gang of motorcyclists. Jimmy and company go off in search of a mysterious goal called the Mountain of Judgment, and warn Superman not to stop them.

THE BRONZE AGE OF COMICS

The Bronze Age retained many of the conventions of the Silver Age, with traditional superhero titles remaining the mainstay of the industry. However, a return of darker plot elements and story lines more related to relevant social issues, such as racism, drug use, alcoholism, urban poverty, and environmental pollution, began to flourish during the period, prefiguring the later Modern Age of Comic Books.

There is no one single event that can be said to herald the beginning of the Bronze Age. Instead, a number of events at the beginning of the 1970s, taken together, can be seen as a shift away from the tone of comics in the previous decade.

One such event was the April 1970 issue of Green Lantern, which added Green Arrow as a title character. The series, written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams, focused on "relevance" as Green Lantern was exposed to poverty and experienced self-doubt.

Later in 1970, Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics, ending arguably the most important creative partnership of the Silver Age (with Stan Lee). Kirby then turned to DC, where he created The Fourth World series of titles starting with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #133 in October 1970. Also in 1970 Mort Weisinger, the long term editor of the various Superman titles, retired to be replaced by Julius Schwartz. Schwartz set about toning down some of the more fanciful aspects of the Weisinger era, removing most Kryptonite from continuity and scaling back Superman's nigh-infinite—by then—powers, which was done by veteran Superman artist Curt Swan together with groundbreaking author Denny O'Neil.

The beginning of the Bronze Age coincided with the end of the careers of many of the veteran writers and artists of the time, or their promotion to management positions and retirement from regular writing or drawing, and their replacement with a younger generation of editors and creators, many of whom knew each other from their experiences in comic book fan conventions and publications. At the same time, publishers began the era by scaling back on their super-hero publications, canceling many of the weaker-selling titles, and experimenting with other genres such as horror and sword-and-sorcery.

The era also encompassed major changes in the distribution of and audience for comic books. Over time, the medium shifted from cheap mass market products sold at newsstands to a more expensive product sold at specialty comic book shops and aimed at a smaller, core audience of fans. The shift in distribution allowed many small-print publishers to enter the market, changing the medium from one dominated by a few large publishers to a more diverse and eclectic range of books.

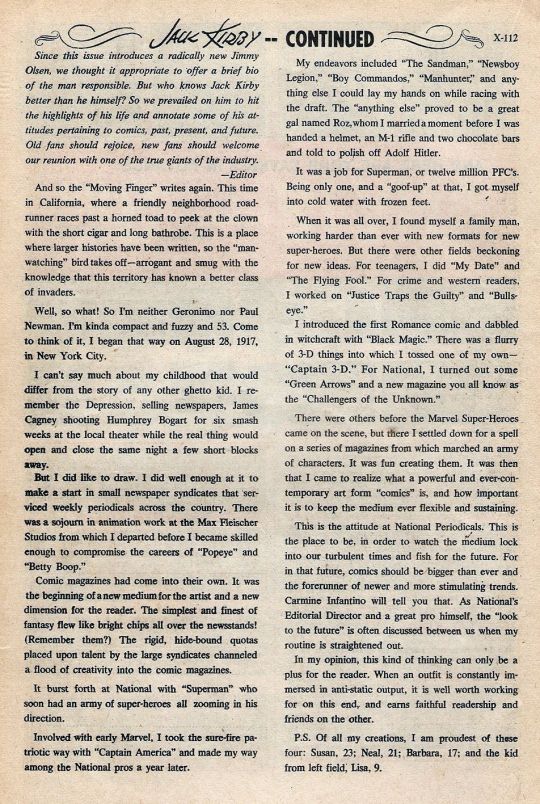

JACK KIRBY

In 1968 and 1969, Joe Simon was involved in litigation with Marvel Comics over the ownership of Captain America, initiated by Marvel after Simon registered the copyright renewal for Captain America in his own name. According to Simon, Kirby agreed to support the company in the litigation and, as part of a deal Kirby made with publisher Martin Goodman, signed over to Marvel any rights he might have had to the character.

At this same time, Kirby grew increasingly dissatisfied with working at Marvel, for reasons Kirby biographer Mark Evanier has suggested include resentment over Lee's media prominence, a lack of full creative control, anger over breaches of perceived promises by publisher Martin Goodman, and frustration over Marvel's failure to credit him specifically for his story plotting and for his character creations and co-creations. He began to both write and draw some secondary features for Marvel, such as "The Inhumans" in Amazing Adventures volume two, as well as horror stories for the anthology title Chamber of Darkness, and received full credit for doing so; but in 1970, Kirby was presented with a contract that included such unfavorable terms as a prohibition against legal retaliation. When Kirby objected, the management refused to negotiate any contract changes. Kirby, although he was earning $35,000 a year freelancing for the company, subsequently left Marvel in 1970 for rival DC Comics, under editorial director Carmine Infantino.

Kirby spent nearly two years negotiating a deal to move to DC Comics, where in late 1970 he signed a three-year contract with an option for two additional years. He produced a series of interlinked titles under the blanket sobriquet "The Fourth World", which included a trilogy of new titles — New Gods, Mister Miracle, and The Forever People — as well as the extant Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen. Kirby picked the latter book because the series was without a stable creative team and he did not want to cost anyone a job. The three books Kirby originated dealt with aspects of mythology he'd previously touched upon in Thor.

The New Gods would establish this new mythos, while in The Forever People Kirby would attempt to mythologize the lives of the young people he observed around him. The third book, Mister Miracle was more of a personal myth. The title character was an escape artist, which Mark Evanier suggests Kirby channeled his feelings of constraint into. Mister Miracle's wife was based in character on Kirby's wife Roz, and he even caricatured Stan Lee within the pages of the book as Funky Flashman. The central villain of the Fourth World series, Darkseid, and some of the Fourth World concepts, appeared in Jimmy Olsen before the launch of the other Fourth World books, giving the new titles greater exposure to potential buyers. The Superman figures and Jimmy Olsen faces drawn by Kirby were redrawn by Al Plastino, and later by Murphy Anderson.

Kirby later produced other DC series such as OMAC, Kamandi, The Demon, and Kobra, and worked on such extant features as "The Losers" in Our Fighting Forces. Together with former partner Joe Simon for one last time, he worked on a new incarnation of the Sandman. Kirby produced three issues of the 1st Issue Special anthology series and created Atlas The Great, a new Manhunter, and the Dingbats of Danger Street.

Kirby's production assistant of the time, Mark Evanier, recounted that DC's policies of the era were not in sync with Kirby's creative impulses, and that he was often forced to work on characters and projects he did not like. Meanwhile, some artists at DC did not want Kirby there, as he threatened their positions in the company; they also had bad blood from previous competition with Marvel and legal problems with him. Since he was working from California, they were able to undermine his work through redesigns in the New York office.

REVIEW

If you are a ninenties creature like me, you remember all these concepts very well, because they came back in the form of Cadmus in the superman titles of the “triangle” era. This is proof that Kirby left a big legacy on more than one company. It is sometimes hard to tell where Kirby starts and where other writers come in. It is hard to tell on his Marvel work at least (and Stan Lee would often take credit for Kirby’s work). So the Fourth World is a good place to check on the real Jack Kirby. Away from Joe Simon, away from Stan Lee.

Now, about this issue. As I said, I knew most of these things from the 90′s Superman titles (that was also the last time Jimmy Olsen mattered). But I have to imagine what it was like to new readers... Jimmy Olsen readers in particular, that a few months ago were reading about Superman trying to prevent Jimmy (an adult) from being adopted. I also have to have in mind that comic-book readers were probably very aware of who Jack Kirby was. The sixties were pretty much dominated by Marvel, and a big part of that success was because of Kirby. But, as I said before, Stan Lee would take the media and take credit for everything. So I am not sure how aware casual readers were with Jack Kirby.

If they weren’t, by this issue they probably were, as DC did a lot of fanfare about the fact that Kirby was coming to DC. Some people compared Bendis coming to DC to this period of time in particular. While there are similarities, it is too early too judge Bendis legacy at this point in time.

The story in this issue is ok. There are a lot of characters and plots being introduced. It’s the first appearance of Morgan Edge, the Wild Area, the Outsiders, the Newsboy Legion (Junior) and other concepts. It is important to remark that this Newsboy Legion is not the golden age version of that group. They are the sons of the originals (and they look pretty much the same... and dress the same). Flip is a bit weird, though. I am pretty sure he doesn’t need the scuba kit on all the time. I will be reviewing the original Newsboy Legion in the golden age reviews.

The art is better than the usual Kirby style, but as it was said above, Al Plastino redrew Superman and Jimmy’s faces. This was common practice at DC, as they didn’t want their most emblematic characters changing too much from issue to issue.

I give this issue a score of 8

#jack kirby#al plastino#fourth world#vince colletta#gaspar saladino#bronze age#dc comics#1970#jimmy olsen#superman's pal jimmy olsen#newsboy legion#comics#review

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deceit, Desire, and the 1980s

Excess, greed, and apathy are words that are equally relevant in describing America in the 1980s as well as Girardian concepts persecution and mediated desire. The application of two of Rene Girard’s books, The Scapegoat and Deceit, Desire, and the Novel with American Psycho, Wallstreet, and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, will prove that the core of these films is rooted in significantly older psychologies -- though Rene Girard would contest this term -- than the contemporary interpretations offer. My argument is that beneath the satire, exposure, and portraiture lies novelistic-mediated desire and elements of mythic persecution.

Definitives are seldom found in nature, and the same is true of a definitive categorization of mediated desire. Several of the implementations by the old masters of the novel, Dostoyevsky; Stendhal; and Cervantes, are different forms of mediated desire and contain idiosyncratic differences among them, but all are demonstrated through the structural model of the triangle (Girard 2).

Girard offers the triangle because it provides a spatial mode of thinking when comparing and contrasting elements of a story. He acknowledges on the second page of Deceit, Desire, and the Novel that all stories can be described with a straight line, from the subject (protagonist), and the object of desire. The object of desire can be anything, and often, anyone: primarily women. What Girard’s triangular model of mediated desire does is introduce a mediator that hovers over the straight line of subject and object and acts as the interpreter of desire. Only the great novelists can articulate this relation according to Girard.

Stendhalian vanity is perhaps the most easily recognizable connection to the culture of the 1980s because it is centered around a protagonist that Girard labels the vaniteux (Girard 6). Stendhal demonstrates vanity through terms like “copying” and “imitating” and it is the latter that draws the most attention. “A vaniteux will desire any object so long as he is convinced that it is already desired by another person whom he admires.” (Girard 7). This quote would suffice as a summary of Patrick Bateman’s character profile in American Psycho. The following sentence further connects Bateman as a modern vaniteux by including, “The mediator here is a rival, brought into existence as a rival by vanity, and that same vanity demands his defeat.” (Girard 7). This firmly establishes an idea for Bateman’s mediator, but that will be covered later.

Firstly, it is essential to detail the aspects of Patrick Bateman that situate him as a vaniteux, despite the description fitting so accurately. Patrick is a vessel; he states in his opening monologue that there is no Patrick Bateman, only an idea. He can only exist as a reflection of others’ perceived desire. He is capable only of wanting and imitating those around him. One of the primary objects that Patrick pursues throughout the film is a reservation at Dorsia, first for the status that comes with being able to get one and secondly because of Paul Allen’s assumed ability to get one. “Humiliation, Impotence, and Shame” are terms that can be interchanged with obstacle (Girard 178). Girard quotes from one of Denis De Rougemont’s books, Love in the Western World, and tells the reader that, “Desire should be defined as a desire of the obstacle.” Patrick desires the obstacle of obtaining the elusive reservation put in place initially by his circle of friends which mention it among their group, but Patrick’s desire is amplified when he discovers that Paul Allen supposedly frequently gets tables at Dorsia and this establishes Allen as a rival to Patrick. Allen as determined the obstacle for Patrick to pursue, it is the most serious obstruction (Girard 179). Passion intensifies throughout the film at this point, even after a modern twist to Stendhalian vanity in which the subject defeats his mediator.

Two primary forms of mediation exist among all of the novelists’ desires, and they are external and internal. These terms are used to demonstrate proximity between the subject and mediator. External mediation exists when the subject is so far removed from the mediator that their realities cannot or would be unlikely to interact. Metaphysical desire falls into this category because a good example of external mediation is the Muslim and Mohammed or any follower of religion and cult. The novelistic example used by Girard is Don Quixote by Cervantes. The opposing side of the spectrum is internal mediation in which the spiritual distance between subject and mediator is close enough for the two spheres of possibilities to “penetrate” one other (Girard 9). Internal mediation is where rivalry begins and is the type that best describes American Psycho. The entire film revolves around class symbols such as fashion, real estate, and rank; the movie embodies physicality. Patrick is only able to imitate what he sees; he is incapable of reciprocating any emotion. He doesn’t desire to be any particular person, only to possess what others have.

Girard says that the hero of internal mediation, or anti-hero in Patrick Bateman’s case, is careful not to have his imitations known, he carefully guards them (Girard 10). Patrick’s plots of murder and social climbing are never uttered to anyone; he does not even acknowledge them to himself through monologue. Girard explains why this is:

In the quarrel which puts him in opposition to his rival, the subject reverses the logical and chronological order of desires in order to hide his imitation. He asserts that his own desire is prior to that of his rival; according to him, it is the mediator who is responsible for the rivalry. (Girard 11)

Patrick kills out of hatred only in the murder of Paul Allen. He is subsequently the sole character that Patrick considers to be equal to, or worse, better than. He takes careful note of Allen’s successes and possessions: the Fisher account, the reservation at Dorsia, and his business card. These empty symbols elicit in Patrick two opposing feelings, that of “submissive reverence” and “the most intense malice” which constitute the passion of hatred (Girard 10).

American Psycho as a film fits neatly within all of Stendhalian vanity because it too works to persuade the viewer that, “the values of vanity, nobility, money, power, [and] reputation only seem concrete.” (Girard 18). Mary Harron works from the source material written by Bret Easton Elis which depicts exceptional vapidity among members of significant affluent status. Patrick Bateman is in possession of all of these things, yet he simply isn’t there. The film shows the audience the danger of a perversely inflated ego, the disassociation between the wealthy and the poor as fellow human beings. There is nothing concrete about Patrick Bateman nor among any of his friends, save for Bryce who seems to have some investment in politics and social issues. It is he who at the end of the film remarks to the group about Reagan’s ability to lie in the face of American people, he is about to make a mention of what is inside Reagan’s false exterior, and Patrick intercedes:

But it doesn’t matter. There are no more barriers to cross. All I have in common with the uncontrollable and the insane, The Vicious and The Evil, all the mayhem that I have caused and my utter indifference to it, I have now surpassed. My pain is constant and sharp, and I do not hope for a better world for anyone. In fact, I want my pain to be inflicted on others. I want no one to escape. But even after admitting this, there is no catharsis. My punishment continues to elude me, and I gain no further knowledge of myself. No new knowledge can be extracted from my telling. This confession has meant nothing.

Sadism is indubitably a large section of Patrick’s character, but the finishing monologue introduces to the audience the closest Patrick could ever come to admitting his role as the masochist. In “Masochism and Sadism,” the eighth chapter of Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, Girard discusses the mediator and subject as Master and Slave respectively (Girard 176). These terms are more in line with external mediation rather than internal, but Girard also explains how a hero of internal mediation can eventually fall into external mediation. Recall that the difference between the two is one of spiritual distance between mediator and subject, therefore, if the mediator grows closer in a story centered in external mediation, then the desire will transform to one of internal mediation and vice versa. American Psycho performs this change at the time of Paul Allen’s murder, which is undoubtedly the most important portion of the film regardless of analysis applied. It is with the death of his rival, the overcoming of the obstacle chosen by his mediator, that Patrick Bateman is able to walk among his own Gods; we will see something similar with Wallstreet later. It is here that Patrick’s mediation is further away, more abstract, and he is even more tortured as a result. “Metaphysical desire always ends in enslavement, failure, and shame.” Patrick elects to be tortured with these tools earlier in the film, he tolerates Paul Allen’s denigration of him, calling Patrick a loser and so on, because has a hero, or rather a victim, of internal mediation, these are the terms that the masochist must accept in desiring objects through a mediator so close in proximity. Patrick deifies Paul, and it is after the acknowledgment of this that Patrick acts. He becomes aware of the connection between his desire and what it truly is, that of Paul’s. Girard says that this is the defining point of the masochist, he is aware of the machinations of mediated desire and endures it (Girard 182). The difference lies in Patrick’s acting upon the structure he assigned himself to rather than the traditional Stendhalian hero who lives to serve his master.

Both the fiction of the film Wall Street and the reality that inspired it are rife with examples that fit into, “Men Become God’s in the Eyes of Each Other.” This chapter focuses on desire as articulated by Proust and Dostoyevsky with the latter’s implementation more relevant to Wall Street. To say that a connection between Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Wall Street is a dramatic understatement. Stanley Weiser, the film’s co-writer, and Oliver Stone explicitly said to each other about making, “Crime and Punishment on Wall Street.” (Lewis) It is also interesting to note Weiser’s admission that he did not read the entirety of Dostoyevsky’s book and opted for the Cliff Notes version. He says the paradigm of the book would not translate to the story of the film, but the proof is in the finished product. What this admission says is that Weiser and Oliver read the highlights of what makes Dostoyevsky’s work effective: mediated desire.

…Dostoyevsky’s hero dreams of absorbing and assimilating the mediators Being. He Imagines a perfect synthesis of his mediator’s strength with his own ‘intelligence.’ He wants to become the Other and still be himself. (Girard 54)

Bud fits into Girard’s definition of a Dostoyevskian hero nearly perfect. Bud does not covet only Gekko’s office, cars, and women; he wants to be Gekko, filtered through what he deems his own experience. He has the grand delusion that all protagonists of mediated desire have: that what is desired can be obtained. Many different explanations exist that connect the subject to the object and Girard often goes back in forth between whether the subject truly wants the object, if he wants to want, or if he wants to be humiliated. Bud appears to fit into the masochist role. Wall Street begins in external mediation as opposed to American Psycho in which the desire mutated from internal to external.

Before the discussion of Men and Gods, it is pertinent to speak of Bud’s fantasies and what his concept of self is. Girard says, “The subject must have placed his faith in a false promise from the outside.” (Girard 56) The false promise is metaphysical autonomy. Bud wants to be at the top, where he thinks that decisions are made. He desires to control the desires of other men as Gekko does unto him.

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we, murderers of all murderers, console ourselves? That which was the holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet possessed has bled to death under our knives. Who will wipe this blood off us? With what water could we purify ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we need to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we not ourselves become gods simply to be worthy of it? There has never been a greater deed; and whosoever shall be born after us - for the sake of this deed he shall be part of a higher history than all history hitherto." (Nietzsche, The Parable of the Madman)

Girard asks, “Why can men no longer alleviate their suffering by sharing it?” (Girard 57) He deems that solitude, a word that predates loneliness, is an allusion just as autonomous desire. A better question more fitting to this paper is, “Why can Bud not realize that his desire is not his own, why can’t he accept that neither he nor Gekko is in intellectual solitude? That they are master and slave?

The answer is because Bud is trapped in external or metaphysical desire. I included Nietzsche’s declaration of the death of God because it relates to Dostoevsky's work greatly and Bud and Gordon Gekko’s relationship by proxy. Jordan Peterson draws the relationship between Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky as the latter predicting the former. Peterson makes clear that Dostoyevsky was not a nihilist but instead a very astute observer of culture (Peterson 213). He takes time in his argument to speak of Dostoyevsky’s prediction of the horrors of communism and how he was in favor of religion and morals over postmodernism, etcetera; however, what interests me most about this line of thought is the connection back to Wall Street. Gekko is to Nietzsche as Bud is to Dostoyevsky.

Gekko grew up in a world abandoned by God, where his father worked himself to an early death and one where he had to become the provider of his own prayers and fill the void. Gekko is revered to by many as a God in many ways, but the best example of praise is when Bud presents to him a cigar as an offering.

…as the gods are pulled down from heaven, the sacred flows over the earth; it separates the individual from all earthly goods… (Girard 62)

Bud sacrifices any possible claim to autonomy by affirming Gekko as his God. Autonomy in the liberal sense is an illusion according to Girard, but the subject does believe it, as many do, as an actuality. Bud cannot look freedom in the face, and as a result, he subjects himself to anguish. (Girard 65)