#Grzegorz Kwiatkowski

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Best Of 2024 - Albumy Polska

Właściwie kompletnie nic się w tej kwestii nie zmieniło jeżeli chodzi o moje coroczne podsumowania roku. Pierwsze moje oficjalne podsumowanie roku wśród polskich albumów miało miejsce w 2013 r. Od początku wprowadziłem pewne filary, podstawy i zasady, którymi się kieruję i nic się w tej kwestii nie zmieniło i nie zmieni. Aczkolwiek kosmetyczne, subtelne zmiany zastosowałem już rok wcześniej. Bo…

#Ada Nasiadka#Anna Rusowicz#Baranovski#Barnim#Bios#Bogdan Kondracki#Brodka#Błażej Król#Chłodno#Coals#Dawid Kwiatkowski#Dominika Płonka#Ewelina Flinta#Grzegorz Hyzy#Jakub Skorupa#Jaśmin#Julia Pietrucha#Kaśka Sochacka#Kilka Czułości#Klaudia Szafrańska#Knedlove#Krzysztof Zalewski#Lanberry#Livka#Marta Zalewska#Małgorzata Ostrowska#Michał Rudaś#Music#Natalia Kukulska#Natalia Szroeder

1 note

·

View note

Text

Meduza's The Beet: The artist, the shoes, and the death camp

Hello, and welcome back to The Beet!

I’m Eilish Hart, the editor of this weekly dispatch from Meduza that brings you long-form journalism from across Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. As it happens, our newsletter’s audience is just 275 subscribers shy of its next round number — and I’d love to reach that milestone before the year ends. So, please take a moment to subscribe to The Beet or, if you’re already a loyal subscriber, forward this email to a friend. Our newsletter is free, but Meduza’s reporting relies on support from readers like you, so spreading the word is a big help!

After last week’s conversation with Ukrainian Nobel Peace Prize laureate Oleksandra Matviichuk, we’re returning to our usual format with a report from Poland, courtesy of journalist James Jackson. As you may recall, James last wrote for The Beet on the eve of this fall’s Polish parliamentary election, which saw opposition parties collectively win more votes than the far-right Law and Justice Party (PiS). Having fallen far short of a parliamentary majority after eight years in power (in an election with record turnout, no less), the PiS cobbled together a doomed government that lasted all of two weeks before succumbing to a no-confidence vote on Monday. This paved the way for a new government under returning Prime Minister Donald Tusk, which had its swearing-in just yesterday.

In the brief interregnum on Tuesday, another, far gloomier event in the Polish parliament grabbed headlines: Just before the vote of confidence in Tusk’s new government, lawmaker Grzegorz Braun — the hard-right, pro-Kremlin leader of a fringe monarchist party — disrupted the proceedings by taking a fire extinguisher to the candles on a menorah lit for Hanukkah. Braun’s fellow lawmakers roundly condemned the stunt, handing him a maximum financial penalty. The parliament’s speaker, who suspended Braun from the day’s session, also promised to report him to prosecutors. In the end, the incident only served to speed things along, as lawmakers withdrew their lingering questions for Tusk and got on with the vote. Meanwhile, a rabbi relit the menorah’s candles.

All of this occurred while I was in the midst of the final edits for this week’s story, which is about none other than Grzegorz Kwiatkowski, a Polish poet and musician who has dedicated himself to raising awareness about his country’s Jewish history. Hailing from the northern port city of Gdańsk, Kwiatkowski has become known for his sharp criticism of Poland’s memory politics, particularly concerning the Holocaust and the thorny topic of Polish complicity. On his blog, Kwiatkowski said Tuesday’s incident in parliament was like a “big dark cloud” over Poland’s collective memory. And it’s precisely this type of cloud — one formed by hatred — that he’s been so actively working to sweep away. So, without further ado, over to James.

Grzegorz Kwiatkowski at the site of the former Jewish ghetto in Gdańsk

BARTOSZ BAŃKA FOR THE BEET

The artist, the shoes, and the death camp

By James Jackson

one of my forefathers must have had the gift of foresight:

I’ve only ever seen my closest in the animal light of their needs

which probably explains my isolation and loneliness

my last birthday observed in a rented bedsit

on the former Adolf Hitler Strasse in the Langhfur district

that day I took my life by turning on the gas taps

— Extract from on a hill by Grzegorz Kwiatkowski

Trudging through the soft earth of an autumnal forest, Grzegorz Kwiatkowski stops in a clearing. His trademark black jeans with gold ringmaster trim contrast against the greens and browns of the trees that rustle like the sounds of the Polish language in the wind.

Kwiatkowski is a man of many hats. He is a poet, the frontman of the post-rock band Trupa Trupa, and a critic of Poland’s memory politics.

For Kwiatkowski, this deserted spot just outside the grounds of the former Stutthof concentration camp encapsulates Poland’s complex and traumatized relationship with its past. Scattered on the forest floor and partially turned to mulch are the remains of hundreds of thousands of shoes taken from Nazi German death camps like Auschwitz.

Though Poland was a battleground for much of its history, today, the battleground is history itself. Debates about the extent of Polish collaboration in the German occupation and the Holocaust led the Law and Justice Party, which governed for the last eight years, to accuse critical historians of a “pedagogy of shame.” The courts even went so far as to prosecute scholars like Barbara Engelking and Jan Grabowski for defamation and order them to apologize for a factual inaccuracy about a long-dead mayor accused of handing over Jews to the Nazis. (The apology was later overturned on appeal.)

In 2022, the Law and Justice government demanded the equivalent of $1.3 trillion in reparations from Germany for damage done during World War II, when Poland lost 17 percent of its population — the highest proportion of any country — and saw cities like Warsaw bombed to rubble, with 85 percent of the capital destroyed.

Destruction in Gdańsk after World War II, 1945

ERICH ENGEL / ULLSTEIN BILD / GETTY IMAGES

Kwiatkowski explains that Stutthof, less than an hour’s drive from Gdańsk, was the leather repair center for all of Nazi Germany’s concentration camps in Europe. The shoes were stolen from their mostly Jewish owners — men, women, and children — and taken here to be converted into leather goods. When the Red Army liberated Stutthof in 1945, they found half a million shoes piled into mountains. These stood neglected until the 1960s, Kwiatkowski says, as Poland’s Soviet-backed communist regime suppressed much of the horror of the Holocaust from popular memory.

Established in 1962, the museum features an exhibit at the entrance with one pile of the shoes, but the rest were given a shallow burial in the forest and left to rot. “It’s the insanity of human beings,” Kwiatkowski says. He and a friend came across the decaying soles in 2015 and later told the story to the international press. After The Guardian and CBC reported on it, nothing changed. But when reporters from the German radio station Deutschlandfunk gave notice that they were coming, the museum staff reportedly panicked and had these artifacts of genocide dug up.

The barracks at the Stutthof camp, photographed after the liberation

FLHC 20214 / ALAMY / VIDA PRESS

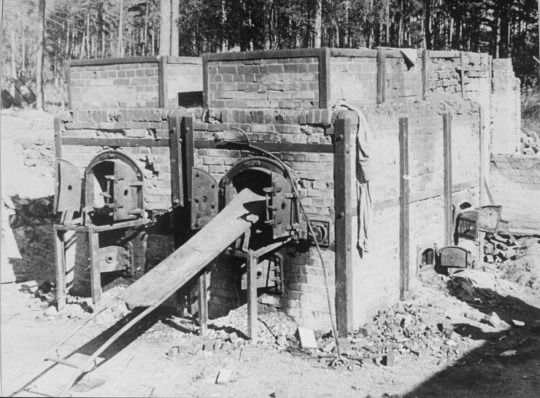

Two cremators at Stutthof, photographed after the liberation

COLLECTION OF THE UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM

“The museum workers were frightened and ashamed because the Germans would see it — it’s so paradoxical,” Kwiatkowski tells me, frustrated at this apparent attempt to brush history under the carpet. Unlike the museum curators, he sees confronting the crimes and neglect of history as his duty. “It’s a privilege to be a curator of this bloody past,” he says. “You can make an anti-hatred message from it: No killing, respect others.”

Later, a chance encounter at a car repair shop led him to doubt the local government’s claims that these artifacts had been disposed of respectfully. Allegedly, the local garbage dump turned away a truck carrying some of the shoes, so they burned the macabre cargo in a field next to the mechanic’s workshop. “I was very nervous and started to ask questions, but I was too curious, and then he [the mechanic] didn’t want to say more,” Kwiatkowski recounts as we drive away from Stutthof. “This is the story of Polish history.”

The shoes on display at the Stutthof Museum

BRUCE ADAMS / GETTY IMAGES

The mounds of shoes Grzegorz Kwiatkowski found in the forest near the former Stutthof camp

GRZEGORZ KWIATKOWSKI’S PERSONAL ARCHIVE

Victims and perpetrators

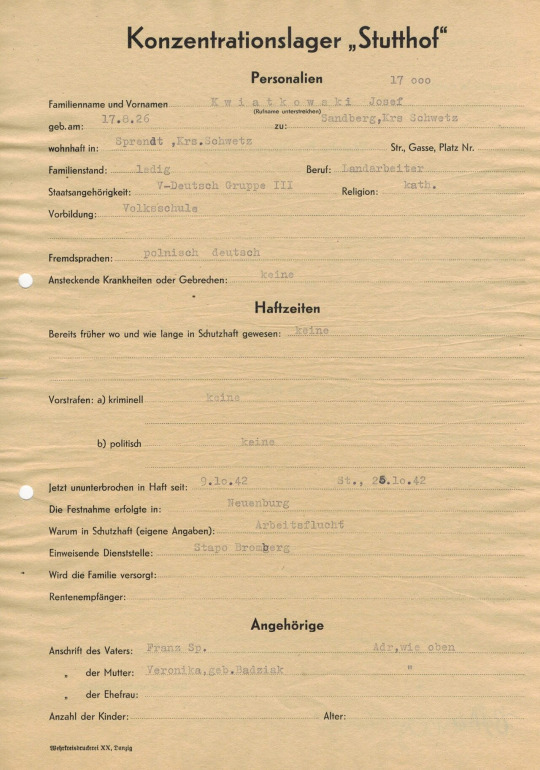

The Stutthof camp isn’t just abstract for Kwiatkowski; it’s intimate. At age 16, his grandfather Józef was imprisoned there for the crime of secretly learning Polish, or for refusing to work as a forced laborer for the Germans, according to conflicting accounts from Kwiatkowski’s family members. Józef’s work was unimaginable, carting dead bodies from the camp hospital to the crematorium, a grim task he would later have to repeat while working as a forced laborer in Hamburg after Allied bombing raids.

One of Józef Kwiatkowski’s documents from the Stutthof camp

GRZEGORZ KWIATKOWSKI’S PERSONAL ARCHIVE

In the interim, he was forcibly conscripted into the Wehrmacht for a short stint, a common experience for men living near what was then the German city of Danzig.

Years later, when visiting the Stutthof museum with his grandson, Józef “started crying and screaming,” Kwiatkowski recalls. “He was [reliving] the trauma,” the poet explains. “He affected my life in the biggest way because he was a broken, calm person.”

Kwiatkowski’s wife’s family suffered terribly, too. Many years into the couple’s marriage, his wife’s grandmother let slip that they had spent the war hiding in the forest. Initially, Kwiatkowski was confused — the German occupation was awful, but this wasn’t normal for ethnic Poles. Eventually, his wife admitted that her family was Jewish, but she had been raised to keep this quiet. “Will it help us here? No,” Kwiatkowski recalls her saying matter-of-factly, though he adds that she’s been more open about her Jewish identity in recent years.

A banner hung on a large synagogue in Danzig (Gdańsk) that reads “Come, beloved May and make us free from the Jews.” June 1939.

AUGUST DARWELL / PICTURE POST / HULTON ARCHIVE / GETTY IMAGES

Even after World War II, anti-Jewish violence in Poland continued to claim lives. In the town of Kielce in 1946, an angry mob, together with Polish soldiers and police, killed 42 Jewish refugees after a child falsely accused them of kidnapping. The massacre triggered a mass exodus of Poland’s surviving Jews, marking the first of four emigration waves during the communist era. The final outflow came as a result of an antisemitic campaign the communist authorities initiated in 1968.

But it’s hard to talk about memory in Poland without running into contradictions, Kwiatkowski finds. “Poland has a victim complex,” he says, and the country was indeed a victim of aggression at the hands of both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. “It’s very complicated because Poland was devastated in a huge way, but on the other hand, [Law and Justice’s] historical narrative is that of a country that is only a victim and innocent.”

Nazi police and soldiers attack a Jewish man in Gdańsk after the German occupation of Poland in 1939

UNIVERSAL HISTORY ARCHIVE / UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP / GETTY IMAGES

Kwiatkowski mentions the recently beatified Ulma family as an example. Nazi German occupiers and local police summarily executed Józef Ulma, his pregnant wife Wiktoria, and their six small children in 1944, along with the eight Jews hidden in their home. “The point of the Ulma family is they were killed because [their] Polish neighbors told the Germans that they were hiding Jews,” he explains — an inconvenient fact often left out of this story of Polish Catholic heroism.

“Jewish people were shocked because the Poles were their neighbors. Many say the Poles were worse than the Germans. [Hearing this] shocked me — but they felt betrayed,” Kwiatkowski says.

At the same time, he maintains that the main perpetrators shouldn’t be forgotten. “Germany and Austria are great at whitewashing history,” Kwiatkowski maintains, referring to the praise the two countries have received for their handling of Holocaust memory. “They did it as a nation, and they should feel bad.”

Beating the system

On top of being an outspoken critic of Poland’s nationalist memory politics, Kwiatkowski and his band Trupa Trupa provided music for director Agnieszka Holland’s award-winning film Green Border, which President Andrzej Duda and other leading government figures attacked for its depiction of Polish border guards mistreating refugees. But Kwiatkowski doesn’t want to be put in a box politically and says he supports the Law and Justice-backed demands for reparations from Germany.

Granary Island, located on the Motława river in Gdańsk, is where the city’s Jewish ghetto once stood

BARTOSZ BAŃKA FOR THE BEET

“I don’t care about the left side or right side,” Kwiatkowski says, “The Polish political class is very corrupt, from left to right. In the 1990s, they were in one party,” he continues. “Polarization helps them. It’s a cynical game that benefits them.”

During the highly-charged campaign season for this fall’s parliamentary election, the brains behind the nationalist government, Law and Justice leader Jarosław Kaczyński, made increasingly wild statements, describing his arch-rival Donald Tusk of the center-right Civic Platform as the personification of “pure evil.” He even accused the opposition of harboring secret plans to ban Poles from mushroom picking.

After the Civic Platform-led coalition won the elections, however, the musician’s tune changed. “I didn’t realize it would make me so happy,” Kwiatkowski tells me, praising the fact that his country had rejected nationalism and its accompanying rewriting of history. “The atmosphere after the elections is really great,” he continues. “If the new government wants to change positively and ethically and talk about [history] openly, I can use their positive attitude and build beautiful ethical works [of art].”

Of all Poland’s politicians, Kwiatkowski remains an admirer of Gdańsk’s most famous son: former dock worker and union leader Lech Wałęsa, who led the Solidarność movement to defeat communism and became Poland’s first president elected by popular vote. In recent years, Wałęsa has been mocked for his down-to-earth manner, celebrating his 80th birthday with a cake made of breaded pork cutlet and taking baths in beer. “He’s like a clown. He’s like Don Quixote,” Kwiatkowski says. “From his perspective, he was a nobody, and then he beat the communist system in Europe. It’s amazing.”

Even though he’s a father of two and now approaching his forties, there’s something similarly boyish about Kwiatkowski’s fascination with the history of his hometown, which produced such notable figures as writer Günter Grass and the country’s new prime minister, Donald Tusk.

The Jewish cemetery in Gdańsk

BARTOSZ BAŃKA FOR THE BEET

The Red Mouse Granary building, which served as a ghetto for Gdańsk Jews

THE TIMES OF ISRAEL

The new memorial plaque on Granary Island

BARTOSZ BAŃKA FOR THE BEET

Back in Gdańsk, Kwiatkowski takes me on a tour of Jewish cemeteries that the local council demolished after the antisemitic purge in 1968; long grass has grown over what was once holy ground. A small community group now funds the maintenance of these ruins, which antisemites desecrate with tragic regularity.

As well as cheering on the change in government, Kwiatkowski is currently celebrating a rare victory in memorializing the past: Alongside local journalist Dorota Karaś, he successfully campaigned for the site of the former Red Mouse Granary — where the Nazis imprisoned local Jews before transporting them to concentration camps — to be officially commemorated. The local authorities have now installed a plaque marking the spot where “the German Nazis created a ghetto for Gdańsk Jews,” written in Hebrew, Polish, German, and English.

But for every victory, there’s a new controversy, it seems. On Tuesday, far-right lawmaker Grzegorz Braun doused a menorah in Poland’s parliament building, lit with candles for Hanukkah, with a fire extinguisher — to near-universal condemnation. Kwiatkowski called for action in response to Braun’s antisemitic attack and promptly received an invite from Gdańsk’s mayor to take part in a Hanukkah candle-lighting ceremony at city hall alongside representatives of the local Jewish community.

Grzegorz Kwiatkowski at the site of the former Jewish ghetto in Gdańsk

BARTOSZ BAŃKA FOR THE BEET

Primo Levi and Theodor Adorno disagreed about whether there could be poetry after Auschwitz. Perhaps it takes not just poets but also musicians, historians, and even quixotic jesters to preserve the memory of the Holocaust in the lands where it was committed. As Kwiatkowski wrote on social media after the ceremony at city hall, Gdańsk is a city that remembers.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Polish post-punk band Trupa Trupa, the atrocities of the past aren’t in the past

In 2018, Trupa Trupa was 15 minutes from taking the stage at the venerable South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas, when singer and guitarist Grzegorz Kwiatkowski’s amp burned out. His frantic search for a replacement ate up 10 minutes of the psychedelic post-punk band’s 30-minute slot. Most bands would have sighed and shaved a few numbers off their setlist. Trupa Trupa? They blasted through…

0 notes

Text

2024 olympics Poland roster

Archery

Wioleta Myszor (Gmina Czernichów)

Athletics

Daniel Sołtysiak (Pomorska)

Oliwer Wdowik (Rzeszów)

Albert Komański (Rzeszów)

Mateusz Borkowski (Starachowice)

Filip Rak (Opole)

Maciej Wyderka (Piekary Śląskie)

Damian Czykier (Białystok)

Krzysztof Kiljan (Łomianki)

Jakub Szymański (Warsaw)

Maher Ben Hlima (Warsaw)

Artur Brzozowski (Nisko)

Kajetan Duszyński (Siemianowice Śląskie)

Maksymilian Szwed (Łódź)

Karol Zalewski (Reszel)

Piotr Lisek (Szamotuły Srabtwo)

Robert Sobera (Wrocław)

Konrad Bukowiecki (Szczytno)

Michał Haratyk (Cieszyn)

Paweł Fajdek (Świebodzice)

Wojciech Nowicki (Białystok)

Marcin Krukowski (Warsaw)

Cyprian Mrzygłód (Gmina Domaniewice)

Dawid Wegner (Nakło Nad Notecią)

Magdalena Niemczyk (Versailles, France)

Aleksandra Formella (Gdynia)

Magdalena Stefanowicz (Bytom)

Ewa Swoboda (Żory)

Martyna Kotwiła (Radom)

Krystsina Tsimanouskaya (Warsaw)

Natalia Kaczmarek (Drezdenko)

Justyna Święty-Ersetic (Racibórz)

Anna Wielgosz (Nisko)

Klaudia Kazimierska (Włocławek)

Weronika Lizakowska (Kościerzyna)

Aleksandra Płocińska (Piaseczno)

Pia Skrzyszowska (Warsaw)

Alicja Konieczek (Zbąszyń)

Aneta Konieczek (Zbąszyń)

Kinga Królik (Pabianice)

Anastazja Kuś (Olsztyn)

Alicja Wrona-Kutrzepa (Lublin)

Aleksandra Lisowska (Braniewo)

Angelika Mach (Warsaw)

Katarzyna Zdziebło (Mielec)

Marika Popowicz-Drapała (Gniezno)

Olga Chojecka (Siedlce)

Mariya Zhodzik (Baranavichy, Belarus)

Nikola Horowska (Gmina Wolsztyn)

Klaudia Kardasz (Białystok)

Daria Zabawska (Białystok)

Malwina Kopron (Puławy)

Anita Włodarczyk (Rawicz)

Maria Andrejczyk (Suwałki)

Adrianna Sułek-Schubert (Bydgoszcz)

Basketball

Adrian Bogucki (Leszno)

Filip Matczak (Zielona Góra)

Michał Sokołowski (Warsaw)

Przemysław Zamojski (Elbląg)

Boxing

Mateusz Bereźnicki (Szczecin)

Damian Durkacz (Knurów)

Julia Szeremeta (Chełm)

Aneta Rygielska (Toruń)

Elżbieta Wójcik (Karlino)

Canoeing

Mateusz Polaczyk (Limanowa)

Grzegorz Hedwig (Nowy Sącz)

Wiktor Głazunow (Gorzów Wielkopolski)

Przemysław Korsak (Gorzów Wilkopolski)

Jakub Stepun (Trzcianka)

Katarzyna Szperkiewicz (Olsztyn)

Klaudia Zwolińska (Nowy Sącz)

Dorota Borowska (Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki)

Sylwia Szczerbińska (Białystok)

Dominika Putto (Mrągowo)

Martyna Klatt (Poznań)

Helena Wiśniewska (Bydgoszcz)

Karolina Naja (Tychy)

Anna Puławska (Mrągowo)

Adrianna Kąkol (Kraków)

Climbing

Aleksandra Kałucka (Tarnów)

Aleksandra Mirosław (Lublin)

Cycling

Stanisław Aniołkowski (Warsaw)

Michał Kwiatkowski (Chełmża)

Mateusz Rudyk (Oława)

Alan Banaszek (Warsaw)

Krzysztof Łukasik (Warsaw)

Marta Lach (Gmina Osiek)

Kata Niewiadoma (Limanowa)

Agnieszka Skalniak-Sójka (Krynica-Zdrój)

Marlena Karwacka (Sławno)

Nikola Sibiak (Darłowo)

Urszula Łoś (Pruszków)

Daria Pikulik (Darłowo)

Wiktoria Pikulik (Darłowo)

Paula Gorycka (Kraków)

Diving

Robert Łukaszewicz (Rzeszów)

Equestrian

Jan Kamiński (Milanówek)

Adam Grzegorzewski (Łódź)

Dawid Kubiak (Tomaszów Mazowiecki)

Maksymilian Wechta (Poznań)

Kata Milczarek-Jasińska (Warsaw)

Aleksandra Szulc (Łódź)

Sandra Sysojeva (Warsaw)

Gorza Korycka (Warsaw)

Robert Powała (Trzebiatów)

Wiktoria Knap (Zielona Góra)

Fencing

Jan Jurkiewicz (Toruń)

Michał Siess (Gdańsk)

Adrian Wojtkowiak (Poznań)

Andrzej Rządkowski (Wrocław)

Alicja Klasik (Rybnik)

Renata Knapik-Miazga (Tarnów)

Martyna Swatowska-Wenglarczyk (Szczecin)

Aleksandra Jarecka (Kraków)

Martyna Jelińska (Toruń)

Hanna Łyczbińska (Toruń)

Julia Walczyk-Klimaszyk (Warsaw)

Martyna Synoradzka (Poznań)

Golf

Adrian Meronk (Wrocław)

Judo

Adam Stodolski (Warsaw)

Piotr Kuczera (Rybnik)

Angelika Szymańska (Włocławek)

Beata Pacut-Kłoczko (Warsaw)

Pentathlon

Kamil Kasperczak (Warsaw)

Łukasz Gutkowski (Warsaw)

Natalia Dominiak (Warsaw)

Anna Maliszewska (Zielowna Góra)

Rowing

Fabian Barański (Włocławek)

Mateusz Biskup (Gdańsk)

Dominik Czaja (Kraków)

Mirosław Ziętarski (Golub-Dobrzyń Powiat)

Martyna Radosz (Bydgoszcz)

Katarzyna Wełna (Stanisławice)

Sailing

Maks Żakowski (Koszalin)

Michał Krasodomski (Warsaw)

Szymon Wierzbicki (Poznań)

Paweł Tarnowski (Gdynia)

Dominik Buksak (Gdynia)

Agata Barwińska (Iława)

Maja Dziarnowska (Gdańsk)

Julia Damasiewicz (Poznań)

Sandra Jankowiak (Szamotuły)

Aleksandra Melzacka (Gdynia)

Shooting

Tomasz Bartnik (Warsaw)

Maciej Kowalewicz (Olsztyn)

Aleksandra Pietruk (Białystok)

Julia Piotrowska (Gdynia)

Natalia Kochańska (Zielona Góra)

Aneta Stankiewicz (Bydgoszcz)

Klaudia Breś (Bydgoszcz)

Swimming

Piotr Woźniak (Olsztin)

Adrian Jaśkiewicz (Warsaw)

Piotr Ludwiczak (Kolobrzeg)

Jakub Majerski (Katowice)

Krzysztof Chmielewski (Warsaw)

Michał Chmielewski (Warsaw)

Ksawery Masiuk (Tarnów)

Jan Kałusowski (Łódź)

Mateusz Chowaniec (Katowice)

Dominik Dudys (Gmina Lipowa)

Bartosz Piszczorowicz (Kalisz)

Kamil Siederadzki (Siemianowice Śląskie)

Kacper Stokowski (Warsaw)

Kata Wasick (Kraków)

Kornelia Fiedkiewicz (Legnica)

Adela Piskorska (Oleśnica)

Laura Bernat (Lublin)

Dominika Sztandera (Dzierżoniów)

Zuzanna Famulok (Katowice)

Julia Maik (Kalisz)

Paulina Peda (Chorzów)

Table tennis

Miłosz Redzimski (Warsaw)

Katarzyna Węgrzyn (Warsaw)

Anna Węgrzyn (Warsaw)

Zuzanna Wielgos (Warsaw)

Natalia Bajor (Warsaw)

Tennis

Magdalena Fręch (Łódź)

Magda Linette (Poznań)

Iga Świątek (Raszyn)

Alicja Rosolska (Warsaw)

Triathlon

Roksana Słupek (Bydgoszcz)

Volleyball

Michał Bryl (Łódź)

Bartosz Łosiak (Jastrzębie-Zdrój)

Łukasz Kaczmarek (Krotoszyn)

Bartosz Kurek (Wałbrzych)

Wilfredo León (Lublin)

Aleksander Śliwka (Jawor)

Grzegorz Łomacz (Ostrołęka)

Jakub Kochanowski (Giżycko)

Kamil Semeniuk (Kędzierzyn-Koźle)

Paweł Zatorski (Łódź)

Marcin Janusz (Nowy Sącz)

Tomasz Fornal (Kraków)

Bartłomiej Bołądź (Krzyż Wielkopolski)

Norbert Huber (Brzozów)

Maria Stenzel (Kościan)

Klaudia Alagierska (Milanówek)

Agnieszka Korneluk (Poznań)

Magdalena Stysiak (Gmina Wieluń)

Martyna Łukasik (Gdańsk)

Aleksandra Szczygłowska (Elbląg)

Joanna Wołosz (Elbląg)

Martyna Czyrniańska (Krynica-Zdrój)

Malwina Smarzek (Łask)

Katarzyna Wenerska (Świecie)

Natalia Mędrzyk (Lębork)

Magdalena Jurczyk (Dukla)

Weightlifting

Weronika Zielińska-Stubińska (Biała Podlaska)

Wrestling

Zbigniew Baranowski (Białogard)

Robert Baran (Jarocin)

Arkadiusz Kułynycz (Miastko)

Anhelina Lysak (Warsaw)

Wiktoria Chołuj (Białogard)

#Sports#National Teams#Poland#Celebrities#Races#France#Belarus#Basketball#Fights#Boxing#Boats#Animals#Golf#Tennis

0 notes

Text

The vastness of Peter Constantine’s personal linguistic range is almost unimaginable to most of us. He moves with ease between German, Modern Greek, Italian, Russian, Afrikaans, French, Ancient Greek—and those are just the languages I happen to know about. It’s no surprise that the Times asked Constantine to review Michael Erard’s book about hyperpolyglots, Babel No More—only that Erard didn’t feature him in it.

Peter is also a terminal speaker of Arvanitika, a severely endangered language of Greece related to Medieval Albanian. That has led him to engage with endangered languages in Europe and across the world. Primarily known as a literary translator, Constantine generally translates into English, but has also recently published a Greek translation of works by Polish poet Grzegorz Kwiatkowski.

Lately he’s been channeling his talents in new directions. He is Professor of Translation Studies at the University of Connecticut, and director of the Program in Literary Translation there, which he founded several years ago. He is also the publisher of the new press World Poetry Books, which exclusively publishes foreign language poetry in English translation.

This April Constantine’s kaleidoscopic debut novel, The Purchased Bride came out from Deep Vellum. The central figure in its shifting perspectives is Maria, a young Greek peasant forced to flee with her family across the mountains of the Ottoman borderlands in eastern Turkey when her village is invaded and ransacked in the spring of 1909.

A precise and visceral study of what imperial heteropatriarchy does to children who have no hope whatsoever of escape, the novel has all the vivid, telling detail of a war documentary, while the empathetic love that suffuses its portrait of Maria makes it unexpectedly buoyant. We know from the beginning that she will survive no matter what she faces.

In celebration of The Purchased Bride’s publication, I asked Peter a few questions about the throughlines between life, fiction, and translation.

*

Esther Allen: What’s it like to live in such a magnificently expansive linguistic universe?

Peter Constantine: Growing up with many languages was a helter-skelter sort of experience. I was born in England but spent my childhood in Austria and Greece—mainly Greece. We were a large family, and my parents and grandparents all spoke different languages, each insisting that I only speak their language to them. Battling this was my father, who was a passionate naturalized Brit of Turkish origin. (His Turkish background was a family secret never to be mentioned in public.)

He insisted that I speak only English. He had been a British major in World War II, and the fact that my Austrian mother and I spoke exclusively in German irked him no end. He hadn’t fought Rommel at El-Alamein only to have to hear the language of the enemy spoken at his dinner table. My parents’ marriage was one long battle, and my mother’s campaign tactics were to speak exclusively in German and to turn his household into a Germanic one, with German parties, German books, German friends, a German priest.

Dad was not pleased that I spoke Greek either. He felt that every word of Greek or German I knew would trounce an English one, banishing it from my vocabulary, compromising my prospects of growing up to be a British gentleman: a man of leisure in a Savile Row suit driving a Jaguar and sporting an Etonian British accent. In fact, he had me registered at Eton minutes after I was born, which in the 1960s was still the done thing among the British upper classes from which his Turkish background categorically excluded him.

EA: So it was your family’s extreme linguistic intransigence that inadvertently trained you in hyper-versatility? Did you end up attending Eton? I can’t imagine they were any less intransigent there….

PC: I never thought of it that way, but you are right! My family was utterly inflexible when it came to language. Not to mention, none of them would tolerate any foreign words bobbing up in anything I might say to them. As for Eton, that was not to be. I passed the exams and was accepted, but my father went bankrupt and left home rather suddenly at just about that time, when I was ten years old.

We had lived all those years in a British and Germanic expat bubble in Kolonaki, a privileged and beautifully manicured Athenian neighborhood, and then my mother and I ended up as illegal aliens in one of the shanty towns outside Athens. It was a worrying but very exciting new way of life: one was never sure if there would be enough food to eat, and though we had a tap, there was only water for one or two hours a day. The shanty town was a wild, unzoned area of red mud and olive trees and open fields with shacks and Romani tents.

There, the true language adventure began. Since time out of mind the area had been an Arvanitic region, and so Arvanitika, one of the non-Greek languages of Greece, was still spoken there, as was Romani whenever the large Roma families would arrive with their orange Datsun pickup trucks and pitch up their tents for a month or two.

EA: How long did you and your mother live in the shanty towns?

PC: All in all, about ten years. But two of those I spent in England, from eleven to thirteen where Dad had moved after the divorce. The plan was still that I would somehow go to a good boarding school like Eton, but since Dad had gone bankrupt I ended up in an inner-city school in London instead.

I arrived there like little Lord Fauntleroy, impeccably dressed and with a posh British accent, since I’d gone to the British Embassy school in Athens. It was a Catholic school, but boys were throwing switchblades at the blackboard, and girls—eleven and twelve years old—would head to the train station during recess to make some pocket money.

Two things happened immediately: I exchanged my posh accent for that of a rough Londoner, and I started saving pennies, one at a time, till I had 24 pounds, which was enough for a bus ticket back to Athens. My father, now in his mid-sixties, had married a nineteen-year-old Iranian girl. I was about to say “woman,” but she was a teenager, and people assumed that she was my fifteen- or sixteen-year-old sister. The marriage was a disaster, and she escaped to France, my father in hot pursuit.

Since by then I had gathered my twenty-four pounds, I used the opportunity to escape to Greece. It is remarkable in retrospect that back in the mid-seventies, with the bus crossing all those European borders on its four-day journey to Athens, none of the passengers or border guards wondered why a thirteen-year-old was traveling unaccompanied.

EA: Was that when you learned Arvanitika, after you got back to your mother in Athens, in the shanty towns? And did you learn Romani, as well?

PC: We lived along a dirt track just off the old road to Mount Pendelikon, which is where the marble for the ancient temples of Athens came from. The mountain has gaping holes from millennia of excavations. Greek was the main language spoken there, but also Arvanitika. Our landlord was a man in his late thirties, and I was surprised that he had trouble speaking Greek.

By then, in the mid-seventies, almost everyone was bilingual, and Arvanitika was beginning to fade. I had been exposed to Arvanitika from an early age, since in the 1960s my parents had bought a house in an old Arvanitic village near Lake Stymphalia, where Hercules had fought the murderous Stymphalian birds.

In the shanty town, there was a lot of Romani in the air, but the Roma remained within their communities and just pitched their tents for several weeks at a time. There was something like a seasonal flow of different Roma groups staying for a while and then moving on. At my school we had a choice between Ancient Greek and Sanskrit, and I chose Sanskrit.

I was very surprised to come across familiar Romani words in class. When the Roma, for instance, say “Dzhanas Romanes?”—”Do you know Romani”—the Sanskrit word for “you know” is dzhanasi. It’s the same word. It was news to me that the Roma might have come from India—in fact the Roma didn’t know that either. But there were so many words in common.

EA: You did have formal schooling during this period, then. In Greek?

PC: I didn’t have a Greek education. I ended up going to Campion, one of the international schools of Athens. The headmaster was a fascinating figure, Jack Meyer. Very British, and very eccentric. He had teachers from all over the world. His first suggestion was that I take Vietnamese classes, that the school would see to it that I could “pass for Vietnamese” by the time I graduated. I was intrigued, but hesitated. His ultimatum was that I must choose Vietnamese or Russian.

I chose Russian. There was an interesting mix of students. My best friend Natasha’s grandparents had fled Russia during the Bolshevik revolution; she spoke an elegant and aristocratic Russian at home. Among our classmates were also the children of Eastern Bloc diplomats. Natasha’s mother, Lily, was a fascinating figure. We were very close, and she introduced me to the Russian classics.

EA: The narrator says on the first page of your novel that the main character, Maria, is his or her (we never find out much about that narrator) grandmother. It’s a work of fiction, clearly, but this seems to indicate, perhaps, some sort of autobiographical inception. What sort of connection did you have with your own grandmother?

PC: The Purchased Bride is indeed a novel and not a memoir; but it is based on my grandmother’s story and that of other women of my Turkish family. My father, who read the first draft, felt that it was very accurate, which surprised me, as I had changed names and places, and had invented characters and situations.

He in fact considered it a sort of biography. I never understood whether what he actually meant was that I had captured the vital essence of my grandmother’s story. I felt that it had to be that. But either way, he recognized the portraits of his mother and his father.

The first glimmers of The Purchased Bride came some twenty years ago, a good two decades after I had left Greece. I was translating the Complete Works of Isaac Babel at the time. It was not that my work on Babel triggered the novel in any way, but that period was when I first wanted to reach back into my family’s Turkish background. It had to be in a fictional way, as my father—and my aunts in the UK—had turned their backs on their Turkish past and would never admit to it.

One aunt had even married a Greek man, who throughout their many decades of marriage never knew she was Turkish. I always found that most puzzling. I wondered what had happened in the 1920s and 1930s to have caused this complete rupture, and their extreme attempts to reinvent themselves as Europeans. As a young man my father kept changing his name—to Turkish names at first, and then Greek ones. He also kept changing his age: he was born in 1920, but also in 1919, and 1915. He had paperwork and passports to prove it. Finally, he confessed that he was born in 1914.

All this in an attempt to escape the past that I touched on in the novel. I tried to research my father’s past, looking through archives and records, but he had managed, quite remarkably, to make any official paperwork that pointed to his birth, or provenance, or schooling disappear. His sisters had done the same. The first sign of my father was as a modern European man, Major Constantine of the British army in Egypt.

As for my grandmother, she died in 1976 in Cyprus, as a result of the violent ethnic cleansing that forcibly moved Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot populations into the Greek or Turkish sectors of the island. The irony is that though my grandmother was old and infirm and originally Greek, she was considered Turkish because of her marriage, and so was expelled by force from the Greek part of the island.

I never met her, as she was part of the Turkish past that my father did his utmost to avoid. And to think that we lived in Athens all those years, a two-hour flight from Cyprus.

EA: You began looking into your family history while translating Babel—but that was not what triggered your interest. What role do you think your career as a translator did have in the writing of this novel?

PC: Gregory Rabassa, a great mentor to a whole generation of translators, famously said that translation is the purest form of writing. It is one of the joys of translation that you can put all your energy into writing: the translator of a novel need not focus on the nuts and bolts of creating characters or developing narrative structures. The main creative focus can remain on how something is said or narrated.

After translating the works of Isaac Babel, I signed a three-book deal to translate a contemporary German author I greatly admire; but as I put pen to paper I found to my dismay that I was having trouble connecting with his style and with the plot movements of the novel. It turned out that we were not an ideal fit. Translating these books was a struggle, and I had a great urge to change the directions of the plot, to take charge of what the characters might do or say.

I successfully resisted, but this urge inspired me to work on my own novel, where I would be free to make my characters say and do what I wanted. I haven’t been similarly tempted since, but that was a great inspiration for my own work.

EA: Hmmm…. I think I know which books you are talking about. Fantastic that translating novels you had serious quibbles with was the catalyst for writing one of your own. Novelists, beware: your translators are learning from you and may outdo you…

Beneath the polished, finely crafted surface of The Purchased Bride is a complicated and intricate criss-cross of languages and cultures. Almost every figure we meet speaks a different group of languages, and the novel beautifully and with great subtlety represents the way its characters are constantly confronting linguistic difference and doing their best to communicate across it. And of course you wrote it in a language none of its characters speak. Were you very conscious of that as you were working on it?

PC: I didn’t consciously give my characters each their own language—but it was very much the way things were in those turbulent borderlands of Asia Minor. Turkey is linguistically quite diverse, and the Ottoman Empire was even more so. Maria, the protagonist, was expected to become Turkish and Moslem, and to shed her old identity, and never speak Greek again.

There was a trend among Ottoman gentlemen of a certain class to have wives who were not Turkish. One of the underlying fears was that Turkish girls were already formed, and might have meddling families, while foreign girls could be molded to fit a husband’s or master’s taste. For centuries Caucasian, Russian, or Greek girls in their early teens would be purchased and cultivated to be ideal Ottoman wives, or concubines, or servants.

The worry that a girl might seem unattractive and suspect if she knows Turkish or any Turkic language is a recurring theme in the novel. Maria, who speaks Tatar relatively well—a Turkic language that is perhaps as similar to Turkish as Dutch is to German—has to keep pretending that she knows only Greek. But through her knowledge of Tatar she can often follow what is being said in Turkish throughout all the transactions that lead to her being purchased.

EA: Did it feel natural to write it in English? Or did you feel the other languages you speak, Greek and Turkish, particularly, tugging at you, annoyed with you for not consecrating your talents to them?

PC: It did feel natural. Throughout the years I have mainly written in English and translated into English. Though I consider Greek to be one of my native languages, I know very little Turkish. In a strange way I hear the language and feel it, but I don’t speak it.

Yet my peculiar connection to Turkish does manifest itself in the novel in oblique ways. I had fun translating some of the newspaper articles of the day spinning out conflicting information about the rumors and scandals that fascinated and delighted Ottoman society of 1909. For instance, the story of the glamorous Madame Claudius Bey who had been murdered “on the high seas” for her priceless pearl necklace.

After years of striving to be meticulous in my translations I now went at these texts with total abandon, understanding some of the phrases, guessing at others, looking up this and that word, recreating the confusion and excitement of an early-twentieth-century reality show.

EA: Your portrayal of Maria skillfully captures what it is to be a valuable piece of human merchandise. She’s a full and complex human being to the reader, but to the people around her, including her own family, her beauty is basically her entire worth. Aside from her luck in the DNA lottery, the other physical asset that confers value on her is her virginity, something we know she has no control over whatsoever.

PC: My father always felt that his father had shown great kindness to my grandmother in marrying her: a sophisticated middle-aged man condescending to show interest in an insignificant little girl. My grandmother was actually thirteen, not fifteen, as Maria is in the novel. It is perhaps a harsh thing to describe my father’s attitude to his mother in this way, but it was entirely a cultural matter.

Beauty and virginity were the only two important elements. If either of those had been missing, my grandmother would not have been acceptable. Wit, to some extent, was important too, a worthwhile quality if it could amuse, but unacceptable if it was to be used to challenge the husband or master.

On reflection, I believe I wrote The Purchased Bride as an antidote to this unyielding patriarchal mindset, which though it belonged to an obsolete, if colorful and intriguing, late-Ottoman society, seemed still so prevalent in the southern European cultures that I grew up in. As a first-generation American literary translator, editor and writer, I felt far enough removed from my European, Greek, and Turkish past, for me to reach back and write a novel that in some ways was connected to that life.

0 notes

Text

Trasa „Lata z Radiem i Telewizją Polską” – przystanek piąty: Park Śląski!

Wakacyjna Trasa „Lata z Radiem i Telewizją Polską” przekroczyła półmetek! Już w najbliższą sobotę 10 sierpnia w Parku Śląskim przy Stadionie Śląskim odbędzie się piąty z serii koncertów organizowanych wspólnie przez TVP i Polskie Radio. Wystąpią: zespół Piersi, Dawid Kwiatkowski, Golden Life, Tatiana Okupnik, Big Cyc, Patrycja Markowska, Jacek Stachursky, Grzegorz Hyży, Józefina i Skubas.…

0 notes

Text

Grzyb e Kwiatkowski con MS Munaretto nel terzo round del campionato polacco

🔴 🔴 Grzyb e Kwiatkowski con MS Munaretto nel terzo round del campionato polacco

Dopo un ottimo avvio di Campionato, con il pluricampione Grzegorz Grzyb che ha saputo cogliere l’argento al Rajd Świdnicki ed il successo assoluto al successivo Rajd Nadwiślański, ora la squadra scledense punta a ben figurare anche nel terzo appuntamento, il 4°Valvoline Rajd Małopolski, in programma nel secondo weekend di Giugno a Wadowice, nel sud della Polonia, al seguito di due equipaggi.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

With the experience I wrote about in my new book, of the death of my first daughter, there is a moment when I realized that I did not want to die, to obliviate myself from this world, and that was a foundational realization for me because I genuinely didn’t know that about myself before. And to be clear, I don’t believe that you have to move past terrible things, or get “better,” or learn from them somehow. That kind of prescription is never my intention. I just mean that it took something cataclysmically overwhelming for me to realize my own desire to live.

Niina Pollari, from Q&A with Niina Pollari and Grzegorz Kwiatkowski

#the offing#q&a#interview#author interview#author conversation#niina pollari#grzegorz kwiatkowski#poet#poetry#writing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lonely Hearts Club Band: an interview with Trupa Trupa's Grzegorz Kwiatkowski

Trupa Trupa by Michal Szlaga. From left: Rafał Wojczal, Wojtek Juchniewicz, Tomek Pawluczuk, Grzegorz Kwiatkowski

Ilia Rogatchevski catches up with the Polish quartet’s front man to discuss Gdansk’s tumultuous history, the films of Werner Herzog and the importance of boredom to the creative process

Trupa Trupa are an art rock band from Gdansk. Fusing elements of post-hardcore, no wave and psychedelia, the four-piece exude a restless energy that bears the hallmarks of Fugazi’s uncompromising punk ethos. Fronted by the poet Grzegorz Kwiatkowski, the band weave absurd lyrics through liquifying guitar riffs, angular bass lines and concise percussion. Repetition plays a key role in their work, as is evidenced by their playful band name, which roughly translates to a troupe of corpses.

Trupa Trupa released their first two albums Headache and Jolly New Songs, through independent labels Blue Tapes and ici d'ailleurs. Both records received international praise. In his Quietus review of the band’s debut, Wire contributor Tristan Bath called Headache ”their first moment of true greatness”.

On the 26 February the band announced that they had signed to Sub Pop, whose label head Jonathan Poneman revealed that he thinks of the band “as a thunderstorm with big gusts, explosions and torrential downpours”. He made the decision to sign them three years ago, but, he says, “it took me a long time to get it done”. Coinciding with the news, Trupa Trupa released the brand new track “Dream About”, with an accompanying video by Norwegian artist Benjamin Finger.

Ilia Rogatchevski: Congratulations on signing to Sub Pop. How did it happen?

Grzegorz Kwiatkowski: Jonathan Poneman, the boss of Sub Pop, was at our gig at OFF Festival in Katowice. He enjoyed the gig and suggested that he would like to work with us. That was six years ago. Through the years we were working hard, but we weren’t working for Sub Pop or anyone else. Of course, we were curious. We knew that it could happen.

The breaking point was when we played SXSW in 2018. The gig was in a small Irish pub. David Fricke from Rolling Stone was there and Robin Hilton from NPR. All these important people came and my amp broke. I asked the stage manager if he had something else, but he didn’t. Suddenly, one person from the audience said: “I’ve got an amp I can give you.”

In 20 minutes we played songs which should be played in 35. The fastest concert ever. We were so angry. Everything was going wrong. The bass player’s guitar stopped working. We kept on playing, but he was shouting with his guitar over his head. These journalists thought: Woah, man! What a band. They are crazy. We are lucky to have strange accidents working on our side.

Is the band a conduit for accidents, then?

We are really open to mistakes. We love absurdity and paradoxes. The band seem a bit dark, but we love to act like clowns. We just wrote many songs with our producer (Michał Kupicz), but we really don’t know if they will be accessible. Let’s see.

youtube

“Dream About”

Benjamin Finger directed the music video for your new song “Dream About”. How did that collaboration come about?

We played with him at a great gig in Cafe Oto in London and became friends. The video looks like hipster stuff from the internet, but it’s his own tapes. We love this kind of atmosphere. It’s very important for us that we are not pretending to be a professional rock band, which makes a professional video. We were afraid that Sub Pop would tell us what to do. Of course, we were wrong. They are totally open to this kind of DIY art.

In a previous interview you suggested that the “spiritual strategy of DIY” is important to the band. Can you define what you mean by that?

You can feel it inside the music that it’s not a PR project. The important thing about Trupa Trupa is that [our] albums are a bit boring. I like to be bored. Our new songs remind me of the atmosphere from Samuel Beckett. Samuel Beckett’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The time is running. We are waiting. We are observing. It’s a meditative, pessimistic thing.

Samuel Beckett’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I like that. In the past you’ve cited The Beatles as a core influence. They were very forward thinking for their time, but are now so canonised that we no longer consider them to be experimental. With that in mind, what sets you apart from other guitar bands working today?

Bands as we are, they don’t exist, because they break up after one or two years. But we exist and are more established than ever. Quite unique, I think, is that we are very democratic in our vision. Every one of us has a strong personality. One is a painter, the second one is a graphic designer, the third a poet, the fourth a reporter and a photographer. Every one of us is trying to put his view inside of the band. It’s kind of a competition. We don’t want to [exist] for the audience. The most important thing is ourselves. I know that sounds narcissistic, but we are friends and this music comes from our friendship.

You guys are based in Gdansk. Have you always been there?

We all live in Gdansk, but not all of us were born here. Tomek Pawluczuk [drums] and Wojciech Juchniewicz [bass] came here from Białystok and Skarżysko-Kamienna, respectively, for studies at the Academy of Fine Arts. Me and Rafał Wojczal [keyboard, guitar] are friends from the same neighbourhood. This is our city and I think that it’s got some impact on us, even if we don’t want it. It’s a very special place, for sure.

What aspects of it seep into your work?

It is the history. Gdansk is connected to the Second World War, to the movement of Solidarity. For me, the place called Westerplatte – the place where the war started – was the dream place for a child. It was like a video game.

There is a mixture of many things in the air still. It’s a really horrifying place, even. For example, a few weeks ago our mayor [Paweł Adamowicz] was murdered. The whole of Poland is in big shock. Gdansk is the city of transgression. Big things are still happening here.

There is also big, great nature around us. We love these landscapes. All of us love Werner Herzog movies, for example. It’s a bit connected to the German aesthetic, I guess. On the other hand, we have our inner landscapes and stories, which are not so connected to the city.

It’s interesting that you mention Herzog. In a previous interview you said that “Jolly New Songs” was a Fitzcarraldo moment for you: the band building an opera house in the middle of the rainforest.

Brian Fitzgerald, the main character of Fitzcarraldo, is a hero for me in the same way as Don Quixote. I’d like to be someone and achieve something, but after all I’m a loser. Every day I wake up and think I will be a better man. It’s not that I would like to be the Übermensch. I would like to be a good man, but I would also like to be a good artist who is constructing his strange ideas and objects.

Listening to “Dream About”, I would compare it to another Herzog film: Lesson Of Darkness (1992), which documents the burning of the oil fields in Kuwait after the Gulf War. It’s contemplative and mellow, but very dark as well.

I think you’re right with this example. For me, the new material is the same. It’s pessimistic, naive and slow. You can hear in this song [“Dream About”] that it’s a bit broken. It’s resigned, calm. Almost every [one of our] songs pretends to be a regular song, but they’re really mantras about nothingness. They really are songs of nowhere.

Trupa Trupa will perform three dates at SXSW 2019 on 14, 15 & 16 March, as well Poznań on 26 April and Sharpe Festival, Bratislava, on 27 April.

Ilia Rogatchevski Originally published by the Wire, 26 February 2019

0 notes

Photo

Grzegorz Kwiatkowski

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

HYPER SCAPE from Platige Image on Vimeo.

We are pleased to present you animation which introduces an entirely new Hyper Scape universe created by Ubisoft. The animation reveals an almost 3-minute vision of the real and virtual worlds from the year 2054. Our artists have been involved in this cinematic trailer project since the very beginning, from the work on the script to setting up dynamic animation in line with the high-octane pace of the in-game action. One big focus was the creation of the hyper-realistic model for the main characters.

Client: Ubisoft Montreal Director: Bartłomiej Kik Executive Producers: Piotr Prokop Producer: Agata Bereś CG Supervisor: Bartosz Skrzypiec Art. Director: Karol Klonowski Head of CG: Bartłomiej Witulski Head of Production: Magdalena Machalica Character art director: Rafał Kidziński Production assistant: Patrycja Romanowska, Marina Sawicka, Anna Zdrojewska Department Manager: Tomasz Wróbel Team Producer: Paweł Gajda, Piotr Gochnio, Ariana Jeż, Klaudia Sordyl Production Coordinator: Dominika Gwardyńska, Marta Krasoń, Maja Kuriata, Anna Stańczak, Adrianna Użycka Storyboard: Michał Murawski Stillomatic: Katarzyna Bobel Lead Enviroment Artist: Paweł Adamajtis Sequence Lead Enviroment Artist: Robert Filipowicz Enviroment Artists: Mariusz Zastawny , Przemysław Sacharczuk, Robert Kudera , Michał Rudkowski , Nauzet Naranjo , Miguel Fonseca , Piotr Nowacki, Daniel Kłos , Oguzhan Kar, Andrzej Augustyniak, Tomasz Kawecki, Adrian Jaśkiewicz, Michał Horba, Adam Jakimiuk, Marcin Białecki, Piotr Mróz, Jarosław Mróz, Marek Mróz, Adam Zimirski, Michał Olechno, Anna Dąbrowska, Kuba Dąbrowski, Paweł Mierzyński, Jarosław Kościański, Ireneusz Jaworski Modeler: Artur Woźniak Hair Grooming Artist: Mirosław Pączkowski, Marcin Kłusek, Chris Debski, Michał Skrzypiec, Rafał Kidziński Lead Character Artist: Sebastian Lautsch Character Artists: Szymon Kaszuba, Artur Owśnicki, Klaudiusz Wesołowski, Maciek Hrynyszyn, Agnieszka Strzęp, Łukasz Kamiński, Paweł Brudniak, Artem Gansior, Filip Adamiak, Artur Woźniak Lead Asset Look Dev Artist: Piotr Nowacki Asset Look Dev Artists: Piotr Orliński, Filip Adamiak, Sebastian Deredas, Żaneta Szabat, Arya Sowti, Łukasz Lesiak, Artem Gansior, Paweł Brudniak Shot Look Dev Artists: Paweł Szklarski, Mateusz Sroka, Character FX Artists: Bartosz Miraś, Kacper Żuliński, Jakub Tyszka, Oleksandr Gorodyskyi Lead Character TD: Bartłomiej Przybylski Character TD: Olga Bieńko, Robert Chrzanowski, Mateusz Matejczyk, Rafael Vitoratti Lead Lighting Artist: Przemysław Patyk Lighting Artists: Michał Pancerz, Krzysztof Olszewski, Marcin Jóźwiak, Michał Witek Lead Compositing Artist: Łukasz Przybytek Compositing Artists: Mateusz Węglarz, Adrian Bałtowski, Dmytro Kolisnyk, Agata Wacławiak-Pączkowska, Witold Płużański, Rafał Szyc, Selim Sykut, Michał Skrzypiec, Andrzej Przydatek, Tomasz Przydatek, Seweryn Czarnecki Lead Previz Artist: Dominik Wawrzyniak Previz Artists: Zuzanna Suska, Jan Sojka, Filip Gracki, Grzegorz Mazur, Michał Kaleniecki, Anna Szustak-Borowska, Amelia Baj, Marta Wadecka, Tomasz Czubak Lead Animation Artist Sequence: Krzysztof Faliński Lead Animation Artist Sequence: Bartosz Jerczyński Animation Artists: Filip Pachucki, Robert Urban, Adam Zienowicz, Franciszek Rzepka, Błażej Andrzejewski, Oleh Ridzel, Olga Szablewicz - Psiuk Lead FX Artist: Michał Firek FX Artists: Michał Grądziel, Rafał Rumiński, Agata Cichosz, Filip Tarczewski, Michał Śledź, Jarosław Armata Lead Matte Paint Artist: Maciej Biniek Matte Paint Artists: Waldemar van Deurse, Igor Firkowski, Adam Trędowski On Line: Michał Własiuk, Karol Klonowski On Line consultant: Hubert Zegardło Grading: Piotr Sasim Conforming: Michał Własiuk CTO: Tomasz Kruszona Lead Pipeline TD: Jarosław Zawiśliński Pipeline TD: Łukasz Dąbała, Witold Duraj, Adrian Krupa, Tomasz Kurgan, Maksim Kuzubov, Sergii Nazarenko Lead Render Wrangler: Rafał Wójcikowski Render Wranglers: Kamil Boryczko, Łukasz Derda, Marcin Jóźwiak, Mateusz Mazur Head of IT: Piotr Getka IT: Jakub Dąbrowski, Krzysztof Konig, Marcin Maciejewski, Łukasz Olewniczak Audio/Video Technique - DI Support: Maciej Żak, Kamil Steć, Cezary Musiał, Piotr Dudkiewicz Motion Capture TD: Aleksander Szymkuć, Grzegorz Mazur Motion Capture Performers: Maria Ruddick, Monika Mińska, Maciej Kwiatkowski, Sławomir Kurek, Jakub Grossman Concept Artist: Krzysztof Rejek, Marcin Kowalski Motion Designer: Adam Blumert Production baby: Antonii Baja

1 note

·

View note

Text

Co się dzisiaj działo? #39 8.2.2022

Turniej ITF w Canberze: Weronika Falkowska-Naiktha Bains 6:4 4:6 4:6

Weronika Falkowska/Olivia Gadecki-Naiktha Bains/Paige Mary Hourigan 6:0 6:2

Kobiece Ashes: Australia (164/2, Meg Lanning 57, Annabel Sutherland 4/31) pokonała Anglię(163, Tammy Beaumont 50, Sophie Ecclestone 1/18) 8 wicketami

NCAA: Virgina Tech Hokies-Pittsburgh Panthers 74:47

Turniej WTA w Sankt Petersburgu: Magda Linette-Aliaksandra Sasnowicz 5:7 6:4 4:6

ICC Cricket League 2: Oman zremisował z ZEA

Turniej ITF w Grenoble: Michał Dembek/Miguel Damas-Gabriel Debru/Arthur Gea 7:5 6:7(0) 5-10

Turniej ITF w Porto: Maja Chwalińska-Quirine Lemoine 6:0 0:6 6:3

Turniej ATP w Rotterdamie: Hubert Hurkacz/Felix Auger Aliassime-Ivan Dodig/Marcelo Melo 6:4 2:6 10-7

FIFA Club World Cup: Palmeiras-Al Ahly 2:0

CEV Liga Mistrzów: OK Maribor-ZAKSA Kędzierzyn-Koźle 0:3

League Two: Carlisle-Port Vale 1:3

Igrzyska Olimpijskie w Pekinie, Dzień 4

Snowboard, slalomy równoległe:

panie

1. Ester Ledecka (CZE)

2. Daniela Ulbing (AUT)

3. Gloria Kotnik (SLO)

5. Aleksandra Król

22. Weronika Biela-Nowaczyk

24. Aleksandra Michalik

panowie

1. Benjamin Karl (AUT)

2. Tim Mastnak (SLO)

3. Victor Wild (RUS)

5. Oskar Kwiatkowski

9. Michał Nowaczyk

Biathlon, bieg indywidualny mężczyzn:

1. Quentin Fillon Maillet (FRA)

2. Anton Smolski (BLR)

3. Johannes Thignes Boe (NOR)

Grzegorz Guzik

Narciarstwo klasyczne, sprinty

panie

1. Jonna Sundling (SWE)

2. Maja Dahlqvist (SWE)

3. Jessica Diggins (USA)

39. Izabela Marcisz

50. Weronika Kaleta

panowie

1. Johannes Klaebo (NOR)

2. Federico Pellegrino (ITA)

3. Alexander Terentev (RUS)

19. Maciej Staręga

58. Kamil Bury

Saneczkarstwo, jedynki kobiet:

1. Natalie Geisenberger (GER)

2. Anna Bereiter (GER)

3. Tatyana Ivanova (RUS)

27. Klaudia Domaradzka

Hokej na lodzie kobiet:

USA-Kanada 2:4

Japonia-Czechy 3:2 po karnych

Finlandia-Rosja 5:0

Szwecja-Dania 3:1

Curling, turniej par mieszanych:

mecz o brązowy medal:

Szwecja-Wielka Brytania 9:3

mecz o złoty medal:

Włochy-Norwegia 8:5

Pozostałe konkurencje medalowe:

Narciarstwo dowolne, big air kobiet:

1. Gu Ailing Eileen (CHN)

2. Tess Ledeux (FRA)

3. Mathilde Gremaud (SUI)

Super Gigant mężczyzn:

1. Matthias Mayer (AUT)

2. Ryan Cochran-Siegle (USA)

3. Alexander Aamodt Kilde (NOR)

Łyżwiarstwo szybkie, 1500m mężczyzn:

1. Kjeld Nuis (NED)

2. Thomas Krol (NED)

3. Kim Minseok (KOR)

0 notes

Photo

Uroczyste poświęcenie cerkwi Zwiastowania w Monasterze Supraskim

W dniu modlitewnego wspomnienia Wszystkich Świętych, w niedzielę, 27 czerwca, w Monasterze Zwiastowania Bogurodzicy w Supraślu odbyła się wyjątkowa uroczystość. Po niemal czterdziestoletniej odbudowie poświęcona została główna świątynia monasteru – cerkiew Zwiastowania Bogurodzicy.

Uroczystościom przewodniczył Jego Eminencja Wielce Błogosławiony Sawa, metropolita warszawski i całej Polski.

Towarzyszyli mu hierarchowie z zagranicy: metropolita włodzimierzo-wołyński i kowelski Włodzimierz (Ukraina), biskup Margweti i Ubisi Melchizedek (Gruzja), i z kraju: arcybiskup białostocki i gdański Jakub, arcybiskup wrocławski i szczeciński Jerzy, arcybiskup bielski Grzegorz, biskup łódzki i poznański Atanazy, biskup hajnowski Paweł, biskup supraski Andrzej, biskup siemiatycki Warsonofiusz, a także licznie przybyli duchowni z całej Polski.

W podniosłym wydarzeniu uczestniczyli przedstawiciele władz centralnych i lokalnych: sekretarz stanu w Kancelarii Prezydenta RP Adam Kwiatkowski reprezentujący Prezydenta RP Andrzeja Dudę, poseł do parlamentu europejskiego Krzysztof Jurgiel, poseł na Sejm RP Eugeniusz Czykwin, wojewoda podlaski Bohdan Paszkowski, marszałek województwa podlaskiego Artur Kosicki, przewodniczący Sejmiku Województwa Podlaskiego Bogusław Dębski, burmistrz Supraśla Radosław Dobrowolski, Podlaski Wojewódzki Konserwator Zabytków Małgorzata Dajnowicz, Rektor Politechniki Białostockiej prof. dr hab. Maria Kosior-Kazberuk, Rektor-Komendant Akademii Marynarki Wojennej w Gdyni komandor prof. dr hab. Tomasz Szubrycht, Dyrektor Muzeum Podlaskiego Waldemar Wilczyński, zastępca Dyrektora Regionalnej Dyrekcji Lasów Państwowych Dawid Iwaniuk, proboszcz supraskiej parafii rzymskokatolickiej ks. Andrzej Chutkowski i wielu innych przedstawicieli władz lokalnych, służb mundurowych, Lasów Państwowych, nadzoru budowlanego, świata kultury i nauki.

Już od godzin porannych wierni gromadzili się w cerkwi Zwiastowania i na monasterskim dziedzińcu, na którym ustawiony był telebim.

Wielu z nich przybyło z różnych części kraju, dzięki zorganizowanym pielgrzymkom autokarowym. W ten sposób pielgrzymowali m.in.. wierni z Warszawy, Krakowa, Wrocławia, Poznania, Lublina i wielu miejscowości Podlasia.

O godzinie 9. nastąpiło powitanie metropolity Sawy i przybyłych biskupów. Hierarchów witały dzieci i młodzież, starosta z radą parafialną, ojcowie i bracia monasteru.

Następnie głos zabrał ordynariusz diecezji białostocko-gdańskiej, Jego Ekscelencja Arcybiskup Jakub, który powitał zaproszonych gości i wszystkich wiernych. Hierarcha w krótkim słowie dziękował wszystkim zaangażowanym w odbudowę świątyni, a szczególne podziękowania za podjęcie decyzji o odbudowie świątyni i opiekę nad tym niezwykłym przedsięwzięciem skierował do Jego Eminencji Metropolity Sawy.

Po Arcybiskupie Jakubie do zebranych z arcypasterskim słowem zwrócił się Zwierzchnik Polskiego Autokefalicznego Kościoła Prawosławnego Jego Eminencja Metropolita Sawa.

– Długo czekaliśmy na tę historyczną chwilę – mówił w swoim przemówieniu Hierarcha – Głęboko wierzę, że dziś nikt nie pozostaje obojętny wobec wydarzenia, które stało się świętem naszej Cerkwi, Której pełnia uczestniczy w dzisiejszej uroczystości. O ile każda świątynia oddziałuje na społeczeństwo, jest potrzebna i wznosimy ją z radością, o tyle w tej kryje się historia i dusza Prawosławia. Odbudujemy ją ku pokrzepieniu serc i jako pomnik dla przyszłości i jako świadectwo przeszłości naszych ojców, matek, braci i sióstr. Dlatego też od pierwszych dni swojej służby arcypasterskiej w diecezji białostocko – gdańskiej zwróciłem uwagę na konieczność odbudowy świątyni Zwiastowania Najświętszej Marii Panny, uzmysłowiając niepowetowaną szkodę jaką był brak tej świątyni.

Eminencja szczegółowo wspominał dzieje odbudowy cerkwi od roku 1981, kiedy to został arcybiskupem białostockim i gdańskim. Podkreślił: – Monaster supraski przez całą swoją działalność zasłużył się nie tylko dla Prawosławia, ale i dla kultury narodowej. W latach największego rozkwitu stał się posiadaczem cennych rękopisów, pamiątek kultury i sztuki słowiańskiej. Był miejscem pobytu i pracy wielu wybitnych ikonografów, architektów i pisarzy.

Swoje słowo metropolita Sawa zakończył podziękowaniami skierowanymi do osób, które przyczyniły się do odbudowania głównej świątyni Bogurodzicy.

Po przemówieniach hierarchów, rozpoczął się obrzęd poświęcenia cerkwi, którego główna część sprawowana była w części ołtarzowej.

Na zakończenie z pobliskiej świątyni św. Jana Teologa do nowo poświęconego ołtarza przyniesiona została cząstka świętych relikwii, po czym sprawowana była pierwsza Święta Liturgia.

W jej trakcie zanoszono modlitwy za żyjących i zmarłych budowniczych i ofiarodawców głównej cerkwi supraskiego monasteru.

Minister Adam Kwiatkowski odczytał następnie list Prezydenta RP Andrzeja Dudy skierowany do uczestników uroczystości.

Prezydent napisał: – Z radością przyjąłem wiadomość o tym, że Ławra Supraska odzyskuje swój centralny, najważniejszy obiekt, czyli historyczną cerkiew główną. (...) Siedemdziesiąt siedem lat temu miał miejsce szczególnie dramatyczny epizod w ponad pięćsetletniej historii klasztoru. Wycofujące się wojska niemieckie, wypędziwszy mnichów wysadziły w powietrze świątynię, której piękno, okazałość oraz czczone tutaj ikony zaliczane przez wieki do prawdziwych skarbów polskiego prawosławia. (...) Dzisiaj jednak wpisany w naszą chrześcijańską wiarę triumf życia nad śmiercią i dobra nad złem staje się, ustępując żalowi i cierpieniu, źródłem radości i wdzięczności. Uroczystość ta ma bowiem istotny wymiar symboliczny. Jest świadectwem duchowego odrodzenia i materialnego wzrostu Polskiego Autokefalicznego Kościoła Prawosławnego – chrześcijańskiej wspólnoty wiary i wartości, której liczni wierni wspaniale służyli i nadal służą Rzeczypospolitej, budując jej pomyślną przyszłość oraz powiększając jej dobra duchowe.

Minister Kwiatkowski przekazał w imieniu Prezydenta RP w darze Monasterowi Supraskiemu łampadę.

Następnie głos zabrali: wojewoda podlaski Bohdan Paszkowski, marszałek województwa podlaskiego Artur Kosicki, poseł do parlamentu europejskiego Krzysztof Jurgiel, burmistrz Supraśla Radosław Dobrowolski oraz zastępca Dyrektora Regionalnej Dyrekcji Lasów Państwowych w Białymstoku Dawid Iwaniuk.

Wszyscy niemal jednogłośnie podkreślali wagę wydarzenia jakim jest ukończenie odbudowy i poświęcenie cerkwi Zwiastowania Bogurodzicy. Gratulowali wszystkim, którzy przyczynili się do tego dzieła. Burmistrz Supraśla przekazał w darze pokaźnych rozmiarów reprodukcję Supraskiej Ikony Bogurodzicy.

Do zgromadzonych zwrócili się także hierarchowie przybyli z zagranicy. Podkreślali oni swoją wielkość radość z możliwości uczestnictwa w tak ważnym dla polskiego prawosławia wydarzeniu.

Na zakończenie, głos zabrał namiestnik Monasteru Supraskiego, biskup Andrzej, który podziękował metropolicie, przybyłym hierarchom i gościom za udział w uroczystościach. Zaznaczył, że odbudowa cerkwi jest cudem, który świadczy o uwielbieniu przez Boga pobożności wiernych trwających w świętej wierze prawosławnej. Na ręce metropolity Sawy przekazał w darze insygnia zwierzchnika Cerkwi – dwa enkolpiony (panagije) i krzyż.

Uroczystości w Supraskiej Ławrze, zakończył posiłek przygotowany przez braci monasteru przy współpracy z siestryczestwem i bractwem młodzieży.

Cerkiew Zwiastowania to obiekt szczególny z punktu widzenia duchowego i artystycznego. To ewenement w historii architektury. Ogniskuje się w nim dorobek dziejowy wielu narodów słowiańskich, zbiega się wiele tradycji i wpływów. Oryginalność architektury cerkwi Zwiastowania polega na połączeniu w budownictwie cerkiewnym gotyckiego i bizantyjskiego stylu. Konstrukcja cerkwi przypomina świątynie obronne Mądrości Bożej w Połocku, Synkowiczach i Małomożejkowie. Powstała w latach 1503-1511. Jej ściany pokryły freski autorstwa mnicha Nektariusza z Serbii. Świątynia została wysadzona przez wojska hitlerowskie w 1944 r. Od roku 1984 trwała jej wieloletnia odbudowa zakończona w roku bieżącym.

Tekst. ihumen Pantelejmon (Karczewski), Michał Gołub Fot. hieromnich Serafim, Sławomir Kiryluk, Aleksandra Jarosławska, Wojciech Stasiewicz

0 notes

Text

Trudna sytuacja przed środowym meczem - dwóch piłkarzy reprezentacji Polski ma koronawirusa!

Trudna sytuacja przed środowym meczem – dwóch piłkarzy reprezentacji Polski ma koronawirusa!

Dwóch piłkarzy reprezentacji Polski – Grzegorz Krychowiak i Kamil Piątkowski są zakażeni koronawirusem. Członkowie sztabu szkoleniowego z wyjątkiem Kwiatkowskiego uzyskali negatywne wyniki. We wtorek rano Jakub Kwiatkowski poinformował o pozytywnych wynikach testu dwóch piłkarzy reprezentacji Polski: Grzegorza Krychowiaka i Kamila Piątkowskiego. Jednocześnie rzecznik kadry dodał, że on sam…

View On WordPress

#GRZEGORZ KRYCHOWIAK#KAMIL PIĄTKOWSKI#MECZ PIŁKI NOŻNEJ#Mistrzostwa Świata#Piłka nożna#reprezentacja Polski

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Tiny Desk is working from home for the foreseeable future. Introducing NPR Music's Tiny Desk (home) concerts, bringing you performances from across the country and the world. It's the same spirit — stripped-down sets, an intimate setting — just a different space. SET LIST "Another Day" "Dream About" "None of Us" MUSICIANS Grzegorz Kwiatkowski: vocals, guitar; Wociech Juchniewicz: vocals, bass, guitar; Tomasz Pawluczuk: drums; Rafał Wojczal: keys, guitar, ondes Martenot CREDITS Audio by: Michał Kupicz; Producer: Bob Boilen; Audio Mastering Engineer: Josh Rogosin; Video Producer: Morgan Noelle Smith; Associate Producer: Bobby Carter; Executive Producer: Lauren Onkey; Senior VP, Programming: Anya Grundmann

0 notes

Quote

I am writing about something which is too big for me — too complicated, too cruel, and too full of moral obscenities. In some way by writing, I am facing something I shouldn’t face. For me, writing about history is writing about family, and writing about family is writing about myself. Why am I this kind of person who is very optimistic and full of joy, and on the other hand afraid of human beings because of their hatred and murder potential? I don’t want to create a false theatrical stage in which I am a good observer and the world is bad — I think that this evil potential is in all of us. But when we find out about it, then it’s our moment to wake up.

Grzegorz Kwiatkowski on poetry and political psych-rock, from Q&A with Niina Pollari and Grzegorz Kwiatkowski

#the offing#q&a#author interview#author conversation#niina pollari#grzegorz kwiatkowski#poets#writing#history#family#politics#music#psych rock

4 notes

·

View notes