#anotherhumaninthisworld

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Is it safe to let a Napoleon and a Bernadotte interact, or will that just prove awkward for my Désirée?

i just honestly think it's easiest to just shoot bernadottes on sight.

it's illegal but anything to protect your napoleon from a betrayal that he did nothing to deserve no way nuh-uh

#bernadotte#napoleon#anotherhumaninthisworld#hey i got this 23 november 2023#when i said i was digging into my queue to try and answer i was not messing with you folks!!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Information on Gabrielle Danton, anyone ? I feel like I know absolutely nothing about her , and she rarely comes up in anecdotes on here, but maybe that’s because there aren’t any… @anotherhumaninthisworld

#I’m sorry I always tag you @anotherhumaninthisworld#I feel like you are working like a slave#merci#frev#Gabrielle Danton#Danton#women in FRev

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

lol me and @anotherhumaninthisworld were discussing Pétion's 'Golden Retriever' personality, and I just ttly felt a need to draw this all day today.

#what was it you called him#'sunshine personified' LOL perfect#there there meowximilien itll allll be fine#frev#french revolution#frev art#Jérôme Pétion#maximillien robespierre#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#Pétion

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Women of the French Revolution (and even the Napoleonic Era) and Their Absence of Activism or Involvement in Films

Warning: I am currently dealing with a significant personal issue that I’ve already discussed in this post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765252498913165313/the-scars-of-a-toxic-past-are-starting-to-surface?source=share. I need to refocus on myself, get some rest, and think about what I need to do. I won’t be around on Tumblr or social media for a few days (at most, it could last a week or two, though I don’t really think it will).

But don’t worry about me—I’m not leaving Tumblr anytime soon. I just wanted to let you know so you don’t worry if you don’t see me and have seen this post.

I just wanted to finish this post, which I’d already started three-quarters of the way through.

One aspect that frustrates me in film portrayals (a significant majority, around 95%) is the way women of the Revolution or even the Napoleonic era are depicted. Generally, they are shown as either "too gentle" (if you know what I mean), merely supporting their husbands or partners in a purely romantic way. Just look at Lucile Desmoulins—she is depicted as a devoted lover in most films but passive and with little to say about politics.

Yet there’s so much to discuss regarding women during this revolutionary period. Why don’t we see mention of women's clubs in films? There were over 50 in France between 1789 and 1793. Why not mention Etta Palm d’Alders, one of the founders of the Société Patriotique et de Bienfaisance des Amies de la Vérité, who fought for the right to divorce and for girls' education? Or the cahier from the women of Les Halles, requesting that wine not be taxed in Paris?

Only once have I seen Louise Reine Audu mentioned in a film (the excellent Un peuple et son Roi), a Parisian market woman who played a leading role in the Revolution. She led the "dames des halles" and on October 5, 1789, led a procession from Paris to Versailles in this famous historical event. She was imprisoned in September 1790, amnestied a year later through the intervention of Paris mayor Pétion, and later participated in the storming of the Tuileries on August 10, 1792. Théroigne de Méricourt appears occasionally as a feminist, but her mission is often distorted. She was not a Girondin, as some claim, but a proponent of reconciliation between the Montagnards and the Girondins, believing women had a key role in this process (though she did align with Brissot on the war question). She was a hands-on revolutionary, supporting the founding of societies with Charles Gilbert-Romme and demanding the right to bear arms in her Amazon attire.

Why is there no mention in films of Pauline Léon and Claire Lacombe, two well-known women of the era? Pauline Léon was more than just a fervent supporter of Théophile Leclerc, a prominent ultra-revolutionary of the "Enragés." She was the eldest daughter of chocolatier parents, her father a philosopher whom she described as very brilliant. She was highly active in popular societies. Her mother and a neighbor joined her in protesting the king’s flight and at the Champ-de-Mars protest in July 1791, where she reportedly defended a friend against a National Guard soldier. Along with other women (and 300 signatures, including her mother’s), she petitioned for women’s rights. She participated in the August 10 uprising, attacked Dumouriez in a session of the Société fraternelle des patriotes des deux sexes, demanded the King’s execution, and called for nobles to be banned from the army at the Jacobin Club, in the name of revolutionary women. She joined her husband Leclerc in Aisne where he was stationed (see @anotherhumaninthisworld’s excellent post on Pauline Léon). Claire Lacombe was just as prominent at the time and shared her political views. She was one of those women, like Théroigne de Méricourt, who advocated taking up arms to fight the tyrant. She participated in the storming of the Tuileries in 1792 and received a civic crown, like Louise Reine Audu and Théroigne de Méricourt. She was active at the Jacobin Club before becoming secretary, then president of the Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires (Society of Revolutionary Republican Women). Contrary to popular belief, there’s no evidence she co-founded this society (confirmed by historian Godineau). Lacombe demanded the trial of Marie Antoinette, stricter measures against suspects, prosecution of Girondins by the Revolutionary Tribunal, and the application of the Constitution. She also advocated for greater social rights, as expressed in the Enragés petition, which would later be adopted by the Exagérés, who were less suspicious of delegated power and saw a role beyond the revolutionary sections.

Olympe de Gouges did not call for women to bear arms; in her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, addressed to the Queen after the royal family’s attempted escape, she demanded gender equality. She famously said, "A woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum," and denounced the monarchy when Louis XVI's betrayal became undeniable, although she sought clemency for him and remained a royalist. She could be both a patriot and a moderate (in the conservative sense; moderation then didn’t necessarily imply clemency but rather conservative views on certain matters).

Why Are Figures Like Manon Roland Hardly Mentioned in These Films?

In most films, Manon Roland is barely mentioned, or perhaps given a brief appearance, despite being a staunch republican from the start who worked toward the fall of the King and was more than just a supporter of her husband, Roland. She hosted a salon where political ideas were exchanged and was among those who contributed to the monarchy's downfall. Of course, she was one of those courageous women who, while brave, did not advocate for women’s rights. It’s essential to note that just because some women fought in the Revolution or displayed remarkable courage doesn’t mean they necessarily advocated for greater rights for women (even Olympe de Gouges, as I mentioned earlier, had her limits on gender equality, as she did not demand the right for women to bear arms).

Speaking of feminism, films could also spotlight Sophie de Grouchy, the wife and influence behind Condorcet, one of the few deputies (along with Charles Gilbert-Romme, Guyomar, Charlier, and others) who openly supported political and civic rights for women. Without her, many of Condorcet’s posthumous works wouldn’t have seen the light of day; she even encouraged him to write Esquilles and received several pages to publish, which she did. Like many women, she hosted a salon for political discussion, making her a true political thinker.

Then there’s Rosalie Jullien, a highly cultured woman and wife of Marc-Antoine Jullien, whose sons were fervent revolutionaries. She played an essential role during the Revolution, actively involving herself in public affairs, attending National Assembly sessions, staying informed of political debates and intrigues, and even sending her maid Marion to gather information on the streets. Rosalie’s courage is evident in her steadfastness, as she claimed she would "stay at her post" despite the upheaval, loyal to her patriotic and revolutionary ideals. Her letters offer invaluable insights into the Revolution. She often discussed public affairs with prominent revolutionaries like the Robespierre siblings and influential figures like Barère.

Lucile Desmoulins is another figure. She was not just the devoted lover often depicted in films; she was a fervent supporter of the French Revolution. From a young age, her journal reveals her anti-monarchist sentiments (no wonder she and Camille Desmoulins, who shared her ideals, were such a united couple). She favored the King’s execution without delay and wholeheartedly supported Camille in his publication, Le Vieux Cordelier. When Guillaume Brune urged Camille to tone down his criticism of the Year II government, Lucile famously responded, “Let him be, Brune. He must save his country; let him fulfill his mission.” She also corresponded with Fréron on the political situation, proving herself an indispensable ally to Camille. Lucile left a journal, providing historical evidence that counters the infantilization of revolutionary women. Sadly, we lack personal journals from figures like Éléonore Duplay, Sophie Momoro, or Claire Lacombe, which has allowed detractors to argue (incorrectly) that these women were entirely under others' influence.

Additionally, there were women who supported Marat, like his sister Albertine Marat and his "wife"Simone Evrard, without whom he might not have been as effective. They were politically active throughout their lives, regularly attending political clubs and sharing their political views. Simone Evrard, who inspired much admiration, was deeply committed to Marat’s work. Marat had promised her marriage, and she was warmly received by his family. She cared for Marat, hiding him in the cellar to protect him from La Fayette’s soldiers. At age 28, Simone played a vital role in Marat’s life, both as a partner and a moral supporter. At this time, Marat, who was 20 years her senior, faced increasing political isolation; his radical views and staunch opposition to the newly established constitutional monarchy had distanced him from many revolutionaries.

Despite the circumstances, Simone actively supported Marat, managing his publications. With an inheritance from her late half-sister Philiberte, Simone financed Marat’s newspaper in 1792, setting up a press in the Cordeliers cloister to ensure the continued publication of Marat’s revolutionary pamphlets. Although Marat also sought public funds, such as from minister Jean-Marie Roland, it was mainly Simone’s resources that sustained L’Ami du Peuple. Simone and Marat also planned to publish political works, including Chains of Slavery and a collection of Marat’s writings. After Marat’s assassination in July 1793, Simone continued these projects, becoming the guardian of his political legacy. Thanks to her support, Marat maintained his influence, continuing his revolutionary struggle and exposing the “political machination” he opposed.

Simone’s home on Rue des Cordeliers also served as an annex for Marat’s printing press. This setup combined their personal life with professional activities, incorporating security measures to protect Marat. Simone, her sister Catherine, and their doorkeeper, Marie-Barbe Aubain, collaborated in these efforts, overseeing the workspace and its protection.

On July 13, 1793, Jean-Paul Marat was assassinated by Charlotte Corday. Simone Evrard was present and immediately attempted to help Marat and make sure that Charlotte Corday was arrested . She provided precise details about the circumstances of the assassination, contributing significantly to the judicial file that would lead to Corday’s condemnation.

After Marat’s death, Simone was widely recognized as his companion by various revolutionaries and orators who praised her dignity, and she was introduced to the National Convention by Robespierre on August 8, 1793 when she make a speech against Theophile Leclerc,Jacques Roux, Carra, Ducos,Dulaure, Pétion... Together with Albertine Marat (who also left written speeches from this period), Simone took on the work of preserving and publishing Marat’s political writings. Her commitment to this cause led to new arrests after Robespierre's fall, exposing the continued hostility of factions opposed to Marat’s supporters, even after his death.

Moreover, Jean-Paul Marat benefited from the support of several women of the Revolution, and he would not have been as effective without them.

The Duplay sisters were much more politically active than films usually portray. Most films misleadingly present them as mere groupies (considering that their father is often incorrectly shown as a simple “yes-man” in these same, often misogynistic, films, it's no surprise the treatment of women is worse).

Élisabeth Le Bas, accompanied her husband Philippe Le Bas on a mission to Alsace, attended political sessions, and bravely resisted prison guards who urged her to marry Thermidorians, expressing her anger with great resolve. She kept her husband’s name, preserving the revolutionary legacy through her testimonies and memoirs. Similarly, Éléonore Duplay, Robespierre’s possible fiancée, voluntarily confined herself to care for her sister, suffered an arrest warrant, and endured multiple prison transfers. Despite this, they remained politically active, staying close to figures in the Babouvist movement, including Buonarroti, with whom Éléonore appeared especially close, based on references in his letters.

Henriette Le Bas, Philippe Le Bas's sister, also deserves more recognition. She remained loyal to Élisabeth and her family through difficult times, even accompanying Philippe, Saint-Just, and Élisabeth on a mission to Alsace. She was briefly engaged to Saint-Just before the engagement was quickly broken off, later marrying Claude Cattan. Together with Éléonore, she preserved Élisabeth’s belongings after her arrest. Despite her family’s misfortunes—including the detention of her father—Henriette herself was surprisingly not arrested. Could this be another coincidence when it came to the wives and sisters of revolutionaries, or perhaps I missed part of her story?

Charlotte Robespierre, too, merits more focus. She held her own political convictions, sometimes clashing with those of her brothers (perhaps often, considering her political circle was at odds with their stances). She lived independently, never marrying, and even accompanied her brother Augustin on a mission for the Convention. Tragically, she was never able to reconcile with her brothers during their lifetimes. For a long time, I believed that Charlotte’s actions—renouncing her brothers to the Thermidorians after her arrest, trying to leverage contacts to escape her predicament, accepting a pension from Bonaparte, and later a stipend under Louis XVIII—were all a matter of survival, given how difficult life was for a single woman then. I saw no shame in that (and I still don’t). The only aspect I faulted her for was embellishing reality in her memoirs, which contain some disputable claims. But I recently came across a post by @saintejustitude on Charlotte Robespierre, and honestly, it’s one of the best (and most well-informed) portrayals of her.

As for the the hébertists womens , films could cover Sophie Momoro more thoroughly, as she played the role of the Goddess of Reason in her husband’s de-Christianization campaigns, managed his workshop and printing presses in his absence accompanying Momoro on a mission on Vendée. Momoro expressed his wife's political opinion on the situation in a letter. She also drafted an appeal for assistance to the Convention in her husband’s characteristic style.

Marie Françoise Goupil, Hébert’s wife, is likewise only shown as a victim (which, of course, she was—a victim of a sham trial and an unjust execution, like Lucile Desmoulins). However, there was more to her story. Here’s an excerpt from a letter she wrote to her husband’s sister in the summer of 1792 that reveals her strong political convictions:

« You are very worried about the dangers of the fatherland. They are imminent, we cannot hide them: we are betrayed by the court, by the leaders of the armies, by a large part of the members of the assembly; many people despair; but I am far from doing so, the people are the only ones who made the revolution. It alone will support her because it alone is worthy of it. There are still incorruptible members in the assembly, who will not fear to tell it that its salvation is in their hands, then the people, so great, will still be so in their just revenge, the longer they delay in striking the more it learns to know its enemies and their number, the more, according to me, its blows will only strike with certainty and only fall on the guilty, do not be worried about the fate of my worthy husband. He and I would be sorry if the people were enslaved to survive the liberty of their fatherland, I would be inconsolable if the child I am carrying only saw the light of day with the eyes of a slave, then I would prefer to see it perish with me ».

There is also Marie Angélique Lequesne, who played a notable role while married to Ronsin (and would go on to have an important role during the Napoleonic era, which we’ll revisit later). Here’s an excerpt from Memoirs, 1760-1820 by Jean-Balthazar de Bonardi du Ménil (to be approached with caution): “Marie-Angélique Lequesne was caught up in the measures taken against the Hébertists and imprisoned on the 1st of Germinal at the Maison d'Arrêt des Anglaises, frequently engaging with ultra-revolutionary circles both before and after Ronsin’s death, even dressing as an Amazon to congratulate the Directory on a victory.” According to Généanet (to be taken with even more caution), she may have served as a canteen worker during the campaign of 1792.

On the Babouvist side, we can mention Marie Anne Babeuf, one of Gracchus Babeuf’s closest collaborators. Marie Anne was among her husband's staunchest political supporters. She printed his newspaper for a long time, and her activism led to her two-day arrest in February 1795. When her husband was arrested while she was pregnant, she made every effort possible to secure his release and never gave up on him. She walked from Paris to Vendôme to attend his trial, witnessing the proceeding that would sentence him to death. A few months after Gracchus Babeuf’s execution, she gave birth to their last son, Caius. Félix Lepeletier became a protector of the family (and apparently, Turreau also helped, supposedly adopting Camille Babeuf—one of his very few positive acts). Marie Anne supported her children through various small jobs, including as a market vendor, while never giving up her activism and remaining as combative as ever. (There’s more to her story during the Napoleonic era as well).

We must not forget the role of active women in the insurrections of Year III, against the Assembly, which had taken a more conservative turn by then. Here’s historian Mathilde Larrère’s description of their actions: “In April and May 1795, it was these women who took to the streets, beating drums across the city, mocking law enforcement, entering shops, cafes, and homes to call for revolt. In retaliation, the Assembly decreed that women were no longer allowed to attend Assembly sessions and expelled the knitters by force. Days later, a decree banned them from attending any assemblies and from gathering in groups of more than five in the streets.”

There were also women who fought as soldiers during the French Revolution, such as Marie-Thérèse Figueur, known as “Madame Sans-Gêne.” The Fernig sisters, aged 22 and 17, threw themselves into battle against Austrian soldiers, earning a reputation for their combat prowess and later becoming aides-de-camp to Dumouriez. Other fighting women included the gunners Pélagie Dulière and Catherine Pochetat.

In the overseas departments, there was Flore Bois Gaillard, a former slave who became a leader of the “Brigands” revolt on the island of Saint Lucia during the French Revolution. This group, composed of former slaves, French revolutionaries, soldiers, and English deserters, was determined to fight against English regiments using guerrilla tactics. The group won a notable victory, the Battle of Rabot in 1795, with the assistance of Governor Victor Hugues and, according to some accounts, with support from Louis Delgrès and Pelage.

On the island of Saint-Domingue, which would later become Haiti, Cécile Fatiman became one of the notable figures at the start of the Haitian Revolution, especially during the Bois-Caiman revolt on August 14, 1791.

In short, the list of influential women is long. We could also talk about figures like Félicité Brissot, Sylvie Audouin (from the Hébertist side), Marguerite David (from the Enragés side), and more. Figures like Theresia Cabarrus, who wielded influence during the Directory (especially when Tallien was still in power), or the activities of Germaine de Staël (since it’s essential to mention all influential women of the Revolution, regardless of political alignment) are also noteworthy.

Napoleonic Era

Films could have focused more on women during this era. Instead, we always see the Bonaparte sisters (with Caroline cast as an exaggerated villain, almost like a cartoon character), or Hortense Beauharnais, who’s shown solely as a victim of Louis Bonaparte and portrayed as naïve. There is so much more to say about this time, even if it was more oppressive for women.

Germaine de Staël is barely mentioned, which is unfortunate, and Marie Anne Babeuf is even more overlooked, despite her being questioned by the Napoleonic police in 1801 and raided in 1808. She also suffered the loss of two more children: Camille Babeuf, who died by suicide in 1814, and Caius, reportedly killed by a stray bullet during the 1814 invasion of Vendôme. No mention is made of Simone Evrard and Albertine Marat, who were arrested and interrogated in 1801.

An important but lesser-known event in popular culture was the deportation and imprisonment of the Jacobins, as highlighted by Lenôtre. Here’s an excerpt: “This petition reached Paris in autumn 1804 and was filed away in the ministry's records. It didn’t reach the public, who had other amusements besides the old stories of the Nivôse deportees. It was, after all, the time when the Republic, now an Empire, was preparing to receive the Pope from Rome to crown the triumphant Caesar. Yet there were people in Paris who thought constantly about the Mahé exiles—their wives, most left without support, living in extreme poverty; mothers were the hardest hit. Even if one doesn’t sympathize with the exiles themselves, one can feel pity for these unfortunate women... They implored people in their neighborhoods and local suppliers to testify on behalf of their husbands, who were wise, upstanding, good fathers, and good spouses. In most cases, these requests came too late... After an agonizing wait, the only response they received was, ‘Nothing to be done; he is gone.’” (Les Derniers Terroristes by Gérard Lenôtre). Many women were mobilized to help the Jacobins. One police report references a woman named Madame Dufour, “wife of the deportee Dufour, residing on Rue Papillon, known for her bold statements; she’s a veritable fury, constantly visiting friends and associates, loudly proclaiming the Jacobins’ imminent success. This woman once played a role in the Babeuf conspiracy; most of their meetings were held at her home…” (Unfortunately for her, her husband had already passed away.)

On the Napoleonic “allies” side, Marie Angélique, the widow of Ronsin who later married Turreau, should be more highlighted. Turreau treated her so poorly that it even outraged Washington’s political class. She was described as intelligent, modest, generous, and curious, and according to future First Lady Dolley Madison, she charmed Washington’s political circles. She played an essential role in Dolley Madison’s political formation, contributing to her reputation as an active, politically involved First Lady. Marie Angélique eventually divorced Turreau, though he refused to fund her return to France; American friends apparently helped her.

Films could also portray Marie-Jacqueline Sophie Dupont, wife of Lazare Carnot, a devoted and loving partner who even composed music for his poems. Additionally, her ties with Joséphine de Beauharnais could be explored. They were close friends, which is evident in a heartbreaking letter Lazare Carnot wrote to Joséphine on February 6, 1813, to inform her of Sophie’s death: “Until her last moment, she held onto the gratitude Your Majesty had honored her with; in her memory, I must remind Your Majesty of the care and kindness that characterize you and are so dear to every sensitive soul.”

In films, however, when Joséphine de Beauharnais’s circle is shown, Theresia Cabarrus (who appears much more in Joséphine ou la comédie des ambitions) and the Countess of Rémusat are mentioned, but Sophie Carnot is omitted, which is a pity. Sophie Carnot knew how to uphold social etiquette well, making her an ideal figure to be integrated into such stories (after all, she was the daughter of a former royal secretary).

Among women soldiers, we had Marie-Thérèse Figueur as well as figures like Maria Schellink, who also deserves greater representation. Speaking of fighters, films could further explore the stories of women who took up arms against the illegal reinstatement of slavery. In Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, many women gave their lives, including Sanité Bélair, lieutenant of Toussaint Louverture, considered the soul of the conspiracy along with her husband, Charles Bélair (Toussaint’s nephew) and a fighter against Leclerc. Captured, sentenced to death, and executed with her husband, she showed great courage at her execution. Thomas Madiou's Histoire d’Haiti describes the final moments of the Bélair couple: “When Charles Bélair was placed in front of the squad to be shot, he calmly listened to his wife exhorting him to die bravely... (...)Sanité refused to have her eyes covered and resisted the executioner’s efforts to make her bend down. The officer in charge of the squad had to order her to be shot standing.”

Dessalines, known for leading Haiti to victory against Bonaparte, had at least three influential women in his life. He had as his mentor, role modele and fighting instructor the former slave Victoria Montou, known as Aunt Toya, whom he considered a second mother. They met while they were working as slaves. They met while both were enslaved. The second was his future wife, Marie Claire Bonheur, a sort of war nurse, as described in this post, who proved instrumental in the siege of Jacmel by persuading Dessalines to open the roads so that aid, like food and medicine, could reach the city. When independence was declared, Dessalines became emperor, and Marie Claire Bonheur, empress. When Jean-Jacques Dessalines ordered the elimination of white inhabitants in Haiti, Marie Claire Bonheur opposed him, some say even kneeling before him to save the French. Alongside others, she saved those later called the “orphans of Cap,” two girls named Hortense and Augustine Javier.

Dessalines had a legitimized illegitimate daughter, Catherine Flon, who, according to legend, sewed the country’s flag on May 18, 1803. Thus, three essential women in his life contributed greatly to his cause.

In Guadeloupe, Rosalie, also known as Solitude, fought while pregnant against the re-establishment of slavery and sacrificed her life for it, as she was hanged after giving birth. Marthe Rose Toto also rose up and was hanged a few months after Louis Delgrès’s death (if they were truly a couple, it would have added a tragic touch to their story, like that of Camille and Lucile Desmoulins, which I have discussed here).

To conclude, my aim in this post is not to elevate these revolutionary, fighting, or Napoleonic-allied women above their male counterparts but simply to give them equal recognition, which, sadly, is still far from the case (though, fortunately, this is not true here on Tumblr).

I want to thank @aedesluminis for providing such valuable information about Sophie Carnot—without her, I wouldn't have known any of this. And I also want to thank all of you, as your various posts have been really helpful in guiding my research, especially @anotherhumaninthisworld, @frevandrest, @sieclesetcieux, @saintjustitude, @enlitment ,@pleasecallmealsip ,@usergreenpixel , @orpheusmori ,@lamarseillasie etc. I apologize if I forgot anyone—I’m sure I have, and I'm sorry; I'm a bit exhausted. ^^

#frev#french revolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#women in history#haitian revolution#slavery#guadeloupe#frustration

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

A rare portrait of Carnot

Well, not so rare anymore since I've now posted it.

It's a tiny 18 x 22 oil canvas kept in the Carnot family archives, reproduced on the back cover of the 1952 edition of M. Reinhard's Le Grand Carnot vol. II, of which you can see a picture I've taken with my phone camera on the left. In its special number about Lazare Carnot (1923), La Sabretache published a colored version of it (picture on the right).

I don't know much else about this portrait, not even whether Carnot had posed for it or not; what's certain is that one of his brothers didn't list it among his most accurate depictions. Still, the way Carnot is represented here matches with the physical descriptions given by La Révellière's in his mémoires.

Sources

M. Reinhard, Le Grand Carnot Vol. II (1952), p. 349-350

Centenaire de Lazare Carnot 1753-1823 notes et documents inédits publiés par La Sabretache (1923)

Mémoires de Larévellière-Lepeaux vol. I (1895), p. 341 (you can read the excerpt translated into English by @anotherhumaninthisworld here)

#yes i've known about the fact he was bald and blonde for exactly a year#imagine my utter surprise when I turned Reinhard's book and saw it. Antoine was a witness lol#lazare carnot#frev#french revolution#directory#directoire#queue#call me crazy but this man will always be handsome in my eyes

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decent Dad Contest:

in light of the already depressing recent poll and and even more depressing thread, I think it's best to do a nicer poll this time!

Thanks to @anotherhumaninthisworld for coming up with the idea and providing info about Camille's dad!

1. Jean Benoît Nicolas Desmoulins

Supportive of his son's revolutionary goals while also expressing worry about his safety (perfectly reasonable)

Seemed to have a lot of patience with his son (which is saying something, given that it's Camille we're talking about... you need all the patience you can get)

Most likely rooting for his relationship with Lucile

Ready to give his son advice

"No, my son, I am not and can never be of your enemies (...) I am and always will be your friend and your best friend"

wrote a letter to the public prosecutor to try and plea for his son's life (in which he mentioned that he's proud of him: fellow-citizen Desmoulins, who until now has held himself honoured in being the father of the foremost and most unflinching of Republicans)

2. Denis Diderot

named his daughter Angélique after his beloved sister and mother

the shared love for their daughter is assumed to be what kept Diderot's and his wife's shaky marriage together for a long time

used the money he got from working on the Encyclopédie to secure the best possible tutors for his daughter

Went again the standards of girls' education of his time (usually focused on singing and piano lessons), instead choosing to teach her to 'think logically' and secure classes in subjects such as history, geography, or musical theory

"I shall teach her, if I can, to endure [the difficulties of life] with fortitude"

there's a reasonable evidence that he believed in his daughter's 'genius' as a composer, and even had the prelude she composed printed (you can listen to it here!)

I recommend this great post and this article for further reading if you're interested!

Also take this with the grain of salt, especially the Diderot one, I should be packing for a trip and didn't have that much time to dig for sources.

Also unfortunately some not completely enlightened views on women authors by our enlightenment philosopher... but hey, at least he believed his daughter to be special, which is kind of sweet? The female question in the 1700s is complex okay...

#this is hard#vote with your heart I guess?#polls#also so glad I've discovered A's music!#frev#french revolution#frev community#frevblr#desmoulins#camille desmoulins#jean desmoulins#denis diderot#age of enlightenment#enlightenment#philosophy#philosophy memes#women's history#Angélique Diderot#history#history memes#history polls#1700s#18th century#music

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Any thoughts fellow tumblrs and Robespierristas? Not one I’ve seen before… Why the ? Did Greuze not give it a title? It’s a very odd face! But closer to the Vizille bust than many better known portraits.

@anotherhumaninthisworld ?

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I had a special liaison with Barbaroux; back at the time he wasn’t absorbed by the want to play the role, he was a good youth and loved to learn from me.” Marat, Journal de la République n.15 p. 8

On 23rd October 1792, two were dinking coffee or wine or anything in a café. They were embracing and must have been provoking curiosity, because one was Marat and the other was Barbaroux.

“All good things must come to an end.”

The scene I opened the post with is extracted from “Histoire des Montagnards” by Alphonse Esquiros. Esquiros claims that the source is Albertine herself, how possible it is for her to tell such stories must be better known by @nesiacha and @anotherhumaninthisworld than me. But the way the facts known to me are presented in this book does not inspire great confidence – the work is too theatrical, and the style reminds one of Lamartine. Still the idea, if not the form of the events, is conveyed passable enough for the quote to be used.

From “Histoire des Montagnards” pp. 455-460:

“At that time a chance for a reconciliation between Barbaroux and Montagnards appeared. Danton, Camille Desmoulins and Marat were promenading one evening along a bank of the Seine. They reached C., which was of wine merchant, and dined under the shade of the vine, right at the water’s edge. <…> Marat had become specially attached to Camille Desmoulins and Barbaroux. In Desmoulins a kind character, a spirit, a joyfulness and always good mood attracted him. Contrast is inherent to friendship as much as to love. Camille Desmoulins responded to this tenderness enthusiastically: he publicly called Marat a prophet, a guardian angel, a genius of the Revolution; he wrote about him as of divine Marat in his journal, but their mutual understanding was many times affected by the differences in their characters. <…> What is for Barbaroux, his new relationships with madame Roland and Girondins party did not fail to tear him away from Marat.

“The three: Danton, Desmoulins, Marat used to gather sometimes to their souls be calmed by the peacefulness of nature. <…> Danton ordered the dishes. They agreed not to bring up hot topics during the frugal meal but failed on the dessert. <…> The night fell on the countryside, the three continued their way to Paris. <…> The conversation turned to Barbaroux and Marat said: “Barbaroux was a friend of mine: if the 10th August had not been succeeded, we would have flown to Marseilles together. He was a good youth back then and loved to learn from me. I have the letters written by his hand in which he calls me his master and himself a disciple. If I have lost him, it’s because of Brissotins who stole him from me by their flattery.” Danton, who still cherished the hope to be a link between the Gironde and the Montagne, proposed to arrange a reconciliation. He took Marat to a small café on Rue du Paon, where Barbaroux awaited. Marat remained cold and reserved at first, but Barbaroux made first steps, and they embraced.”

That is what Barbaroux says about Marat, although he is only partly credible here.

From Barbaroux’s Memoires (p. 57):

“I’ve already said in the first part of my Memoires that in 1788 I took an optics course under Marat. I’ve appreciated him as a scholar, I must make him known as a politician.

“One of my writings about the rebellion in Arles fell into his hands, he complimented me and invited to come see him in the apartment opposite Café Richard on Rue Saint-Honoré, where he lived. I came. I recognized my optics master, but when he began to speak, I thought he had lost his mind. He was seriously telling me that the French were petty revolutionaries and only he himself could establish liberty. I wanted to approach the great man, I seemed to be eager for his instructions. He told me: “Give me two hundred Neapolitans armed with draggers and wearing a muff as a shield on the left hand; I will walk through France with them and make the revolution.” All he said after was of the same sort. He wanted to prove me that it was a very humane calculation to kill two hundred and sixty thousand men in a day. No doubt he had a special attraction to this number, because he always wanted two hundred and sixty thousand, rarely reaching three hundred thousand.”

What catches my eye here is “Je voulus pressentir le grand homme, je parus avide de ses instructions.” after the nonsense Marat had told him. After being amazed by Marat once, he once again falls under his spell. These words are sincere. And they are believable from a man who was a real dictator for a month, a role which Marat used to define as the best form of a ruler. The way Barbaroux confesses here is not rare. He also confesses in influencing the elections, simply and with no guilt. It somehow reminds me that Talleyrand’s “Yes, I loved him" about Napoleon. In Barbaroux you can also sense that “in certain circumstances all means are good” – Marat’s doctrine and the way Charlotte Corday legitimizes his murder (the linkage between their ways of thinking is stunningly traced by L. Blanc in his Histoire). Bringing back the Esquiros’ story (not believing it) and filling what is omitted in it, Barbaroux had what Desmoulins couldn’t have – understanding.

Whether it was vanity or something else that connected Barbaroux with the Girondins I will now not discuss.

From Moniteur (26 October 1792 issue):

The scene was played on 24th October. Marat requested the floor and after some bickering with the president Guadet (“Oh! You will listen to me… Against your will.) and several debates of awaiting got it to make a denunciation of Roland and Claviere. He convicted them of empowering an agent, previously spotted, according to the statements Marat brought, to search for counterfeiters. The documents related were read by a secretary, who coincidently turned out to be Barbaroux. Having finished, Barbaroux made his own denunciation.

“I demand that the minister Roland report these facts to the Assembly and I’ll add that the truly guilty one is a perverse man, an agitator who stirs the trouble and discord up in Paris, who runs to the caserns of the battalions of volunteers to deceive them, to try to corrupt them with insinuations and calumnies, to cast a bone between them and the others; and who invites several volunteers to lunch with him to get time and occasion to learn their sentiments, opinions lead them astray.

“Citizens, I will read you the report where all these facts are collected. I was written this morning by the Marseille battalion.”

Marat, firstly greeted very warmly by the volunteers, observed their lodging, listened to the descriptions how they were welcomed by the Commune and noticed, that they are disadvantaged compared to the dragoons of the first regiment consisted of “gardes-du-corps of the ancient regime, valets, coachmen, counterrevolutionaries etc”. While the volunteers admitted the dissatisfaction with their lodgings being fair, they arose against the words about the dragoons and regarded it as an attempt to sow discord between them. They then saw a will to bribe them in the invitation to the lunch and ended up being displeased with Marat.

While the previous confrontations between Barbaroux and Marat were strictly politician, Marseilles were personal. It’s hard to imagine anything that Barbaroux would take to heart more than his – in all meanings – battalions. Marat’s attempt was an act of violation (pardon me for the word), whether it was committed for the purpose described by Marseilles or not.

So, it was the end.

I’m not saying there could be a continuation if not. The very characters of them leave me no such elusion. The breakup was prepared, but it passed painfuly.

And even their shared taste in furs couldn't help

#i couldn't pass by that post about girondin-montagnard breakups yes#no really look at them their furs their cravates one turn of a head like master like disciple#frev#french revolution#girondins#barbaroux#jean paul marat#camille desmoulins#danton#george danton

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because I'm new at tumblr( I've been here for only 3 or 4 months maybe ) and I'm not an elite person ( like @anotherhumaninthisworld or @edgysaintjust or @saint-jussy .) So I ask the all elites of this glorious community ( don't ask why I speak like that just ignore) to give an answer for this good fellow out here.

Because I found it very hard to answer him properly with evidences and sources etc. And I want to give the best answer I can by asking help from you everyone.

#frev#french revolution#french history#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#please robespierre's fans don't attack him he's just asking a question.

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello @anotherhumaninthisworld! I recently got into a debate with one of my classmates during our history class. My classmate accepts that the Thermidorians committed atrocities and quote, "Killed a bunch of people but so did Robespierre so they're both horrible". My classmate also says that "Since Robespierre justified the use of terror, he was a horrible person." He also states that Robespierre and the Jacobins committed unnecessary violence, that Robespierre's actions were similar to Hitler's, Robespierre and the radicals had created a totalitarian empire, and that the beheading of Louis XVI was unnecessary violence. He also states that Robespierre's beheading was ironic considering the thousands of people he had executed. He also says that Napoleon was better than Robespierre, and that Robespierre got corrupted during the Revolution. While I know many of these are Thermidorian Propaganda and outright false information, he also has skepticism towards Tumblr or anything else that doesn't state Robespierre was a dictator for resources. He says, quote "How did you know that he didn't commit unnecessary violence and wasn't a dictator?" Are there any primary sources or any historical evidence that can justify my counterargument? I apologize for such a long ask, and thank you so much for what you do here on Tumblr. ❤️

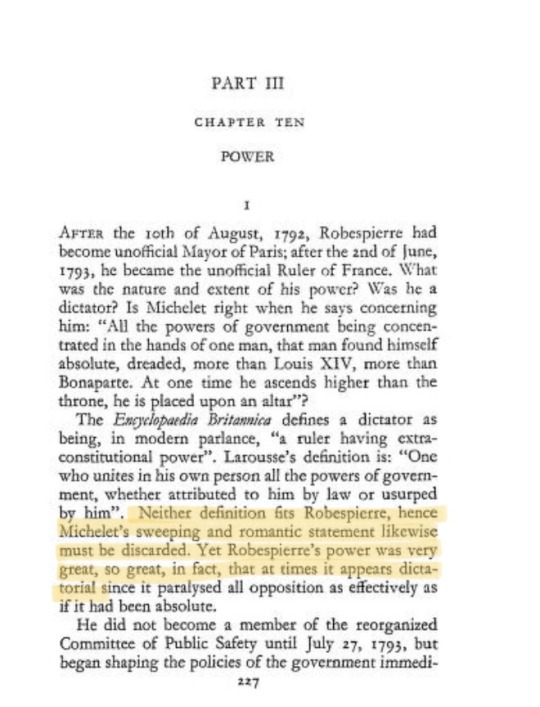

If you’re trying to debunk your classmate’s claims, then it’s a bit hard for me to offer any good primary sources/historical evidence, because most of his statements are subjective. Whether or not Robespierre was a horrible person for justifying the use of terror, Napoleon was better than him and the Jacobins committed unneccessary violence are all are based on our own personal sentiment, because there exists no way to objectively measure horribleness, goodness and usefulness. ”Robespierre’s actions were similar to Hitler’s” is in its turn a claim so vague that it’s probably true to some extent (both men killed in the name of a bigger cause?), but you could replace Hitler with almost any other leader and say the very same thing. All of this is not to say any of these statements are especially nuanced, but I don’t think they can be fully debunked as much as they can be elaborated on (is for example your friend aware that France was under the burden of not just being at war with most of Europe, but also uprisings and civil wars within its own borders by the time the jacobins used violence and Robespierre justified using terror, which, while not excusing their actions, at least contextualizes them?) The best resources for providing nuance and context I don’t think would be primary sources, which function the best when we talk about less broad questions, but instead secondary sources, AKA, books on the revolution written by historians. Which books are the most useful can of course be debated and we did discuss which ones we thought best for beginners on here in this post. Though if your classmate is automatically going to dismiss anything that doesn’t agree with his claims (even if it’s a book written by a professional) I’m afraid I don’t really know what to do here…

When it comes to the claim that Robespierre got corrupted during the Revolution, I have to ask what it is he’s referring to here. If what he means is that Robespierre got corrupted by money, then my answer would be that I, along with all historians I’ve so far looked at, have yet to find any proof of this having happened. And if that sounds like a weak counter argument, remember that the burden of proof always lies with the accuser. One does not assume that something exists until proven false, it’s the opposite way around. Do we know for sure Robespierre never took any bribes? No. Is it reasonable to assume he didn’t until proven otherwise? Yes. So maybe instead of trying to find evidence that Robespierre wasn’t corrupt (or rather absence of evidence), you should instead challange your classmate to hand you evidence that he was indeed corrupt. If what he means is that Robespierre got corrupted by power, then we’re back to the first section — this is not something that can be factually proven or disproven, because we don’t know what was going on in someone’s head 200 years ago.

As for the final question — ”How did you know that he didn't commit unnecessary violence and wasn't a dictator?" — you could bring up the fact that Robespierre never had an official dictator title, he was a member of a non-hierarchal twelve man committee that in its turn was part of a government body made up of approximately 750 people. To prove this, you could show your classmate the following decree founding said committee, dated April 6 1793, three months before Robespierre joined it:

1. There will be formed, by roll call, a Committee of Public Safety, composed of nine members of the National Convention.

2. This committee will deliberate in secret; it will be responsible for monitoring and accelerating the action of the administration entrusted to the provisional executive council, whose decrees it may even suspend when it believes them to be contrary to the national interest, on the condition of informing without delay the Convention.

3. It is authorized to take, in urgent circumstances, general external and internal defense measures; and its decrees, signed by the majority of its deliberative members, which cannot be less than two thirds, will be executed without delay by the provisional executive council. It may in no case issue arrest warrants, except against his executing agents, with the responsibility of reporting without delay to the Convention.

4. Every week it will write a general report on its operations and the situation of the Republic.

5. A register of all its deliberations will be kept.

6. The national treasury will remain independent from the committee, and subject to the immediate supervision of the Convention, following the method established by the decree.

This decree clearly shows the powers of the committee were not limitless, even if it should also be admitted said powers would be expanded upon over the following months, with the committee gaining the right to everything from issuing arrest warrants to conducting foreign policy. That said, all of its members still had to be monthly reelected by the Convention, which had the power to dismiss one if it saw fit. The committee’s work and Robespierre’s own share in it can be studied rather well through the twelve volume work Recueil des Actes du Comité de Salut Public, so that’s another primary source you could recommend for your classmate.

To your classmate’s defence, it should also be admitted that Robespierre at the time of ”the terror” was a highly (the most?) influencial politician, way more famous than the rest of his collegues, to the extent that the average Frenchman seems to have viewed Robespierre’s power as greater than it theoretically was supposed to be already before his death. It can also be proven Robespierre had people he had listed as ”good patriots” at the head of several important revolutionary institutions, something which we’re unable to do for his collegues. But power is still a tricky thing to measure so to say all these attributes add up to the powers of an unofficial dictator is still dubious. If your classmate won’t take some random tumblr user’s word for it (which I can understand), here are some historians and biographers (none of which I would call bias in Robespierre’s favor) saying the exact same thing:

Robespierre: first modern dictator (1931) by Ralph Korngold

Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution (200) by Ruth Scurr

Robespierre Dictateur ? (2014) by Guillaume Mazeau

Robespierre (2014) by Hervé Leuwers

If your classmate insists this must only be a very small minority of historians, I would once again suggest he gives you the names of those arguing that Robespierre was indeed a dictator. And if he can’t do that, perhaps ask him why then he can still be so sure over this?

For the part about committing violence, I will admit, like I already wrote here, that, through primary sources, it can be proven that Robespierre did oversee and sanction state sponsored violence, even if, strictly and linguistically speaking, he never committed it himself (he could for example not personally order for a person to be executed). Whether or not said violence was unneccesary or not does again boil down to our personal opinions. This is a subjective question and therefore, in my view, not one that is worth arguing over.

And thank you 💚

#robespierre#maximilien robespierre#ask#analyzing statements that are unscientific but also so vague you’re left saying:#”well he’s sort of right if you look at in strictly this way” sure gave me a headache…#like what did i even write here…

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Rating: Not Cute!

This is a Napoleon from those punk-ass "Blown Apart" breeding mills! They breed Napoleons to meet the demands of the consumer, ie. making the Napoleon smaller and "cuter" (here defined as 'having big eyes and looking cuddly' NOT being an animal that can live a happy and healthy life!), and angrier.

This creature lives in unending ceaseless agony, and we need to pull our resources and stop more abominations like him from being created. Unfortunately, for humanity's sake, we might need to put this one down...

#//obviously i actually think that channel is hil-ARIOUS and i have no real beef#is the napoleon cute?#not cute#napoleon#ask#anotherhumaninthisworld

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading an overly sentimental poem about Germinal at the stanza poetry festival :-)

@reggiespoon @anotherhumaninthisworld @commiecamille @saltforsalt

#frev#camille desmoulins#dantonists#indulgents#germinal#if one can be sure any historical person would want you to read sentimental poetry about their violent death on a stage#surely it’s Camille ??#Lucile Desmoulins

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incorruptible chap 3 pt 9

I like to think that when they got along, Brissot and Camille sang Revolution Songs together (they're not drunk, they're just...Brissot and Camille together in a room).

Also, the song is VERY loosely translated from this song, made in 1791. Robespierre was featured in songs as far back as that! Because the song seems to pursue rhyming over other elements, I also chose rhyming over a more direct translation.

Another also: thank you @anotherhumaninthisworld for several posts and links, which helped me figure out Brissot more easily, alongside discovering that he's like *ridiculously* short lol

#incorruptiblecomic#I figured brissot out fairly quickly#it became evident early on in reading that he had unbreakable confidence#and just went head first into things because he seemed to believe every time it would be fine lmao#I guess that sums up his war decisions? lol#frev#french revolution#brissot#camille desmoulins#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#petion#jerome petion#frev comic#frev art#history comic#french history#historical drama#historical fiction

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which friendship breakup during the French Revolution between a Girondin and a Montagnard/Jacobin broke your heart the most?

That of Brissot and Desmoulins For more details, see here: https://www.tumblr.com/anotherhumaninthisworld/775038158779875328/how-was-the-relationship-between-brissort-and?source=share

That of Pétion and Robespierre For more details, see here: https://www.tumblr.com/anotherhumaninthisworld/760041507348692992/hi-a-lot-has-already-been-written-about?source=share

Huge thanks to @anotherhumaninthisworld for these two wonderful posts!

The ones that Jean-Nicolas Pache and Gaspard Monge had with Manon Roland before their falling out with the Muse of the Gironde You’ll find some details about their relationships and the eventual rupture in the mini-biography I wrote on Pache:

Part I: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/777295133948411904/jean-nicolas-pache-the-swiss-minister-of-war?source=share

Part II: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/778721992245477376/jean-nicolas-pache-the-swiss-minister-of-war?source=share

Fact I didn’t mention in these post : In her memoirs, Manon Roland wrote that Pache’s children, Jean and Sylvie, sighed for Paris from Switzerland, as they missed the city dearly. (Even if I doubt that’s entirely true—they were still very young when they left Paris��it’s likely they missed their friends more than the city itself and it should be noted that I have noted at least one inconsistency in Manon Roland's memoirs on Pache so all the more reason not to take everything in her memoirs at face value ). Still, this would suggest that either Roland really knew the children, or, despite his famously secretive nature, Pache must have confided in her. Which just shows how close they truly were in my opinion :(

#frev#french revolution#frev friendship#then broke#pétion#maximilien robespierre#jacques pierre brissot#camille desmoulins#Gaspard Monge#roland manon#jean nicolas pache#so sad

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rules: make a poll with five of your all time favourite characters and then tag five people to do the same. see which character is everyone's favorite.

Tagged by @magicmagic09 merci!! ^_^

Tagging (no pressure!): @pleasecallmealsip @nesiacha @orpheusmori @nordleuchten @anotherhumaninthisworld @thermidorette @zaegreus @fffraw @monaldus and whoever else wants to do it.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Too 5 Lucile Moments?

Thanks for the ask! It won't be easy to narrow it down to five, seeing how Lucile is my favourite frev lady.

First things first - my eternal thanks to @anotherhumaninthisworld for compiling so many amazing resources on Lucile! Also, be warned, this will get sad.

1. Lucile trying to appeal to Robespierre after her husband's arrest

I'm specifically talking about the letter in which she tries to appeal to Robespierre after her husband's arrest. You can tell she does not hold back, desperately trying to appeal to her husband's former friend's emotions ("Do you believe that the people will bless one who cares neither for the tears of the widow nor for the death of the orphan?") and even tries to use Saint-Just as a sort of rhetorical device to further her argument. But alas, it does not work.

Then there's of course the whole supposed Luxembourg Plot, which I still need to read more on so I can get a sense of what might or might not have happened. But one thing is clear to me: she did not sit idly after The Indulgents arrest.

2. Lucile becoming friends with Françoise Hébert before their execution

Apparently, the two struck an unlikely friendship while awaiting the guillotine. They are even reported to have hugged before the execution. (Sorry, I told you, this will get sad!)

(Read more about it here!)

3. Lucile standing up for Camille and his work

There's an anecdote that Brune, one of Camille's old college friends, warned him (quite reasonably honestly) about the risks he's likely to run into if he continues to write so openly in his newspaper.

To this, Lucile is said to have replied: “Let him do it, Brune, let him do it, he must save his country; let him fulfill his mission.” (& then poured them some chocolate).

(Read more about it here, including the assessment of the sources!)

4. Lucile's super secret teenage diary

The whole thing honestly! Lucile's angst, her questioning her role in the world, thinking about what it means to be a woman, a human being -- definitely worth a read. Again, thanks so much to @anotherhumaninthisworld for taking her time to translate it.

Some of my favourite parts include:

Her suffering from writer's block: I want to finish my story, I cannot finish it! I take up the pen, I want to write, but nothing comes…

Her writing down her strange dreams (this will most likely be relatable for anyone who's ever kept a diary)

Her philosophical musings: See, my mind is wandering. Do I know what I am?… My God, I don’t know myself. What spring makes me act?

Her being worried that her mum will find (and read) her diary, which most likely already included some mentions of her fascination with Camille: Maman made me tremble last night: she came to fetch the inkwell, I was in bed, she opened my drawer to take a pen, I was afraid she would take my notebook…

Her secretly carving out Camille's name into a tree

5. Lucile and Camille briefly leaving Paris and enjoying some rest in the countryside

In 1793, the couple briefly visited Essonne and spent some time there. Some of the activities apparently included driving a boat (with Lucile noting her husband's less-than-perfect boating skills) and riding donkeys.

Taken from & more details included here!

(-> according to Google, you can picture the landscape looking a little something like this)

Bonus: Camille falling asleep on Lucile's shoulder during the night some time during the August 1792 Insurrection

Again, from Lucile's diary, as she was waiting for her husband to return from the fighting in the streets of Paris:

Alone, bathed in tears, on my knees by the window, hidden in my handkerchief, I listened to the sound of that fatal bell. In vain they came to console me, this fatal night seemed to me to be the last!

and then:

C(amille) came back at 1 o’clock, he fell asleep on my shoulder.

#thanks for the ask!#ask game#frev#french revolution#frevblr#frev community#1700s#18th century#lucile desmoulins#camille desmoulins#women's history#french history

41 notes

·

View notes