#women in FRev

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Information on Gabrielle Danton, anyone ? I feel like I know absolutely nothing about her , and she rarely comes up in anecdotes on here, but maybe that’s because there aren’t any… @anotherhumaninthisworld

#I’m sorry I always tag you @anotherhumaninthisworld#I feel like you are working like a slave#merci#frev#Gabrielle Danton#Danton#women in FRev

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

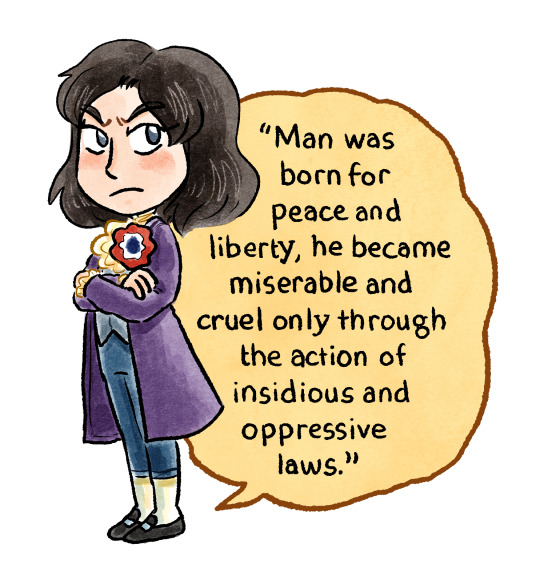

Some little doodles and inspirational quotes from Camille Desmoulins, Louis Antoine Saint-Just, and Maximilien Robespierre 💖

I've made these 3 cos I'm making some stickers for a comic convention thats very soon, and did the most 'famous' people for starters/who ppl following me might know from my comic :3

But when I have free time I'm definately gonna make some of lesser discussed but equally inspiring revolutionaries~

#It would be awesome to make some of the women and black ppl involved in Frev#I think for ppl not into Frev who are attending cons#sharing such people would be a fun inspiring insight into the history#but I want to do my research first on such people before I make stickers of them#to get their personalities right and find cool quotes~#frev#french revolution#frev art#camille desmoulins#louis antoine saint just#maximilien robespierre#saint just#robespierre

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which Underrated Woman from History are You?

Finally got around to making a uquiz featuring six of my favourite women from history! You can either get someone from the French Revolution, Roman Republic (I know, how unexpected!) or from 1700s/early 1800s.

Featuring scientists, writers, politically active icons and a few poets whose lives were intertwined with theirs, as a treat!

Enjoy and thanks everyone for sharing! ✨

#frev#french revolution#ancient rome#roman republic#history#tagamemnon#uquiz#tumblr quiz#which are you?#age of enlightenment#1700s#1800s#romantic era#18th century#19th century#émilie du châtelet#fulvia#clodia#mary shelley#ada lovelace#lord byron#literature#women's history#uquiz link#personality quiz#quiz tag#percy bysshe shelley#lucile desmoulins#camille desmoulins#catullus

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Women of the French Revolution (and even the Napoleonic Era) and Their Absence of Activism or Involvement in Films

Warning: I am currently dealing with a significant personal issue that I’ve already discussed in this post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765252498913165313/the-scars-of-a-toxic-past-are-starting-to-surface?source=share. I need to refocus on myself, get some rest, and think about what I need to do. I won’t be around on Tumblr or social media for a few days (at most, it could last a week or two, though I don’t really think it will).

But don’t worry about me—I’m not leaving Tumblr anytime soon. I just wanted to let you know so you don’t worry if you don’t see me and have seen this post.

I just wanted to finish this post, which I’d already started three-quarters of the way through.

One aspect that frustrates me in film portrayals (a significant majority, around 95%) is the way women of the Revolution or even the Napoleonic era are depicted. Generally, they are shown as either "too gentle" (if you know what I mean), merely supporting their husbands or partners in a purely romantic way. Just look at Lucile Desmoulins—she is depicted as a devoted lover in most films but passive and with little to say about politics.

Yet there’s so much to discuss regarding women during this revolutionary period. Why don’t we see mention of women's clubs in films? There were over 50 in France between 1789 and 1793. Why not mention Etta Palm d’Alders, one of the founders of the Société Patriotique et de Bienfaisance des Amies de la Vérité, who fought for the right to divorce and for girls' education? Or the cahier from the women of Les Halles, requesting that wine not be taxed in Paris?

Only once have I seen Louise Reine Audu mentioned in a film (the excellent Un peuple et son Roi), a Parisian market woman who played a leading role in the Revolution. She led the "dames des halles" and on October 5, 1789, led a procession from Paris to Versailles in this famous historical event. She was imprisoned in September 1790, amnestied a year later through the intervention of Paris mayor Pétion, and later participated in the storming of the Tuileries on August 10, 1792. Théroigne de Méricourt appears occasionally as a feminist, but her mission is often distorted. She was not a Girondin, as some claim, but a proponent of reconciliation between the Montagnards and the Girondins, believing women had a key role in this process (though she did align with Brissot on the war question). She was a hands-on revolutionary, supporting the founding of societies with Charles Gilbert-Romme and demanding the right to bear arms in her Amazon attire.

Why is there no mention in films of Pauline Léon and Claire Lacombe, two well-known women of the era? Pauline Léon was more than just a fervent supporter of Théophile Leclerc, a prominent ultra-revolutionary of the "Enragés." She was the eldest daughter of chocolatier parents, her father a philosopher whom she described as very brilliant. She was highly active in popular societies. Her mother and a neighbor joined her in protesting the king’s flight and at the Champ-de-Mars protest in July 1791, where she reportedly defended a friend against a National Guard soldier. Along with other women (and 300 signatures, including her mother’s), she petitioned for women’s rights. She participated in the August 10 uprising, attacked Dumouriez in a session of the Société fraternelle des patriotes des deux sexes, demanded the King’s execution, and called for nobles to be banned from the army at the Jacobin Club, in the name of revolutionary women. She joined her husband Leclerc in Aisne where he was stationed (see @anotherhumaninthisworld’s excellent post on Pauline Léon). Claire Lacombe was just as prominent at the time and shared her political views. She was one of those women, like Théroigne de Méricourt, who advocated taking up arms to fight the tyrant. She participated in the storming of the Tuileries in 1792 and received a civic crown, like Louise Reine Audu and Théroigne de Méricourt. She was active at the Jacobin Club before becoming secretary, then president of the Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires (Society of Revolutionary Republican Women). Contrary to popular belief, there’s no evidence she co-founded this society (confirmed by historian Godineau). Lacombe demanded the trial of Marie Antoinette, stricter measures against suspects, prosecution of Girondins by the Revolutionary Tribunal, and the application of the Constitution. She also advocated for greater social rights, as expressed in the Enragés petition, which would later be adopted by the Exagérés, who were less suspicious of delegated power and saw a role beyond the revolutionary sections.

Olympe de Gouges did not call for women to bear arms; in her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, addressed to the Queen after the royal family’s attempted escape, she demanded gender equality. She famously said, "A woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum," and denounced the monarchy when Louis XVI's betrayal became undeniable, although she sought clemency for him and remained a royalist. She could be both a patriot and a moderate (in the conservative sense; moderation then didn’t necessarily imply clemency but rather conservative views on certain matters).

Why Are Figures Like Manon Roland Hardly Mentioned in These Films?

In most films, Manon Roland is barely mentioned, or perhaps given a brief appearance, despite being a staunch republican from the start who worked toward the fall of the King and was more than just a supporter of her husband, Roland. She hosted a salon where political ideas were exchanged and was among those who contributed to the monarchy's downfall. Of course, she was one of those courageous women who, while brave, did not advocate for women’s rights. It’s essential to note that just because some women fought in the Revolution or displayed remarkable courage doesn’t mean they necessarily advocated for greater rights for women (even Olympe de Gouges, as I mentioned earlier, had her limits on gender equality, as she did not demand the right for women to bear arms).

Speaking of feminism, films could also spotlight Sophie de Grouchy, the wife and influence behind Condorcet, one of the few deputies (along with Charles Gilbert-Romme, Guyomar, Charlier, and others) who openly supported political and civic rights for women. Without her, many of Condorcet’s posthumous works wouldn’t have seen the light of day; she even encouraged him to write Esquilles and received several pages to publish, which she did. Like many women, she hosted a salon for political discussion, making her a true political thinker.

Then there’s Rosalie Jullien, a highly cultured woman and wife of Marc-Antoine Jullien, whose sons were fervent revolutionaries. She played an essential role during the Revolution, actively involving herself in public affairs, attending National Assembly sessions, staying informed of political debates and intrigues, and even sending her maid Marion to gather information on the streets. Rosalie’s courage is evident in her steadfastness, as she claimed she would "stay at her post" despite the upheaval, loyal to her patriotic and revolutionary ideals. Her letters offer invaluable insights into the Revolution. She often discussed public affairs with prominent revolutionaries like the Robespierre siblings and influential figures like Barère.

Lucile Desmoulins is another figure. She was not just the devoted lover often depicted in films; she was a fervent supporter of the French Revolution. From a young age, her journal reveals her anti-monarchist sentiments (no wonder she and Camille Desmoulins, who shared her ideals, were such a united couple). She favored the King’s execution without delay and wholeheartedly supported Camille in his publication, Le Vieux Cordelier. When Guillaume Brune urged Camille to tone down his criticism of the Year II government, Lucile famously responded, “Let him be, Brune. He must save his country; let him fulfill his mission.” She also corresponded with Fréron on the political situation, proving herself an indispensable ally to Camille. Lucile left a journal, providing historical evidence that counters the infantilization of revolutionary women. Sadly, we lack personal journals from figures like Éléonore Duplay, Sophie Momoro, or Claire Lacombe, which has allowed detractors to argue (incorrectly) that these women were entirely under others' influence.

Additionally, there were women who supported Marat, like his sister Albertine Marat and his "wife"Simone Evrard, without whom he might not have been as effective. They were politically active throughout their lives, regularly attending political clubs and sharing their political views. Simone Evrard, who inspired much admiration, was deeply committed to Marat’s work. Marat had promised her marriage, and she was warmly received by his family. She cared for Marat, hiding him in the cellar to protect him from La Fayette’s soldiers. At age 28, Simone played a vital role in Marat’s life, both as a partner and a moral supporter. At this time, Marat, who was 20 years her senior, faced increasing political isolation; his radical views and staunch opposition to the newly established constitutional monarchy had distanced him from many revolutionaries.

Despite the circumstances, Simone actively supported Marat, managing his publications. With an inheritance from her late half-sister Philiberte, Simone financed Marat’s newspaper in 1792, setting up a press in the Cordeliers cloister to ensure the continued publication of Marat’s revolutionary pamphlets. Although Marat also sought public funds, such as from minister Jean-Marie Roland, it was mainly Simone’s resources that sustained L’Ami du Peuple. Simone and Marat also planned to publish political works, including Chains of Slavery and a collection of Marat’s writings. After Marat’s assassination in July 1793, Simone continued these projects, becoming the guardian of his political legacy. Thanks to her support, Marat maintained his influence, continuing his revolutionary struggle and exposing the “political machination” he opposed.

Simone’s home on Rue des Cordeliers also served as an annex for Marat’s printing press. This setup combined their personal life with professional activities, incorporating security measures to protect Marat. Simone, her sister Catherine, and their doorkeeper, Marie-Barbe Aubain, collaborated in these efforts, overseeing the workspace and its protection.

On July 13, 1793, Jean-Paul Marat was assassinated by Charlotte Corday. Simone Evrard was present and immediately attempted to help Marat and make sure that Charlotte Corday was arrested . She provided precise details about the circumstances of the assassination, contributing significantly to the judicial file that would lead to Corday’s condemnation.

After Marat’s death, Simone was widely recognized as his companion by various revolutionaries and orators who praised her dignity, and she was introduced to the National Convention by Robespierre on August 8, 1793 when she make a speech against Theophile Leclerc,Jacques Roux, Carra, Ducos,Dulaure, Pétion... Together with Albertine Marat (who also left written speeches from this period), Simone took on the work of preserving and publishing Marat’s political writings. Her commitment to this cause led to new arrests after Robespierre's fall, exposing the continued hostility of factions opposed to Marat’s supporters, even after his death.

Moreover, Jean-Paul Marat benefited from the support of several women of the Revolution, and he would not have been as effective without them.

The Duplay sisters were much more politically active than films usually portray. Most films misleadingly present them as mere groupies (considering that their father is often incorrectly shown as a simple “yes-man” in these same, often misogynistic, films, it's no surprise the treatment of women is worse).

Élisabeth Le Bas, accompanied her husband Philippe Le Bas on a mission to Alsace, attended political sessions, and bravely resisted prison guards who urged her to marry Thermidorians, expressing her anger with great resolve. She kept her husband’s name, preserving the revolutionary legacy through her testimonies and memoirs. Similarly, Éléonore Duplay, Robespierre’s possible fiancée, voluntarily confined herself to care for her sister, suffered an arrest warrant, and endured multiple prison transfers. Despite this, they remained politically active, staying close to figures in the Babouvist movement, including Buonarroti, with whom Éléonore appeared especially close, based on references in his letters.

Henriette Le Bas, Philippe Le Bas's sister, also deserves more recognition. She remained loyal to Élisabeth and her family through difficult times, even accompanying Philippe, Saint-Just, and Élisabeth on a mission to Alsace. She was briefly engaged to Saint-Just before the engagement was quickly broken off, later marrying Claude Cattan. Together with Éléonore, she preserved Élisabeth’s belongings after her arrest. Despite her family’s misfortunes—including the detention of her father—Henriette herself was surprisingly not arrested. Could this be another coincidence when it came to the wives and sisters of revolutionaries, or perhaps I missed part of her story?

Charlotte Robespierre, too, merits more focus. She held her own political convictions, sometimes clashing with those of her brothers (perhaps often, considering her political circle was at odds with their stances). She lived independently, never marrying, and even accompanied her brother Augustin on a mission for the Convention. Tragically, she was never able to reconcile with her brothers during their lifetimes. For a long time, I believed that Charlotte’s actions—renouncing her brothers to the Thermidorians after her arrest, trying to leverage contacts to escape her predicament, accepting a pension from Bonaparte, and later a stipend under Louis XVIII—were all a matter of survival, given how difficult life was for a single woman then. I saw no shame in that (and I still don’t). The only aspect I faulted her for was embellishing reality in her memoirs, which contain some disputable claims. But I recently came across a post by @saintejustitude on Charlotte Robespierre, and honestly, it’s one of the best (and most well-informed) portrayals of her.

As for the the hébertists womens , films could cover Sophie Momoro more thoroughly, as she played the role of the Goddess of Reason in her husband’s de-Christianization campaigns, managed his workshop and printing presses in his absence accompanying Momoro on a mission on Vendée. Momoro expressed his wife's political opinion on the situation in a letter. She also drafted an appeal for assistance to the Convention in her husband’s characteristic style.

Marie Françoise Goupil, Hébert’s wife, is likewise only shown as a victim (which, of course, she was—a victim of a sham trial and an unjust execution, like Lucile Desmoulins). However, there was more to her story. Here’s an excerpt from a letter she wrote to her husband’s sister in the summer of 1792 that reveals her strong political convictions:

« You are very worried about the dangers of the fatherland. They are imminent, we cannot hide them: we are betrayed by the court, by the leaders of the armies, by a large part of the members of the assembly; many people despair; but I am far from doing so, the people are the only ones who made the revolution. It alone will support her because it alone is worthy of it. There are still incorruptible members in the assembly, who will not fear to tell it that its salvation is in their hands, then the people, so great, will still be so in their just revenge, the longer they delay in striking the more it learns to know its enemies and their number, the more, according to me, its blows will only strike with certainty and only fall on the guilty, do not be worried about the fate of my worthy husband. He and I would be sorry if the people were enslaved to survive the liberty of their fatherland, I would be inconsolable if the child I am carrying only saw the light of day with the eyes of a slave, then I would prefer to see it perish with me ».

There is also Marie Angélique Lequesne, who played a notable role while married to Ronsin (and would go on to have an important role during the Napoleonic era, which we’ll revisit later). Here’s an excerpt from Memoirs, 1760-1820 by Jean-Balthazar de Bonardi du Ménil (to be approached with caution): “Marie-Angélique Lequesne was caught up in the measures taken against the Hébertists and imprisoned on the 1st of Germinal at the Maison d'Arrêt des Anglaises, frequently engaging with ultra-revolutionary circles both before and after Ronsin’s death, even dressing as an Amazon to congratulate the Directory on a victory.” According to Généanet (to be taken with even more caution), she may have served as a canteen worker during the campaign of 1792.

On the Babouvist side, we can mention Marie Anne Babeuf, one of Gracchus Babeuf’s closest collaborators. Marie Anne was among her husband's staunchest political supporters. She printed his newspaper for a long time, and her activism led to her two-day arrest in February 1795. When her husband was arrested while she was pregnant, she made every effort possible to secure his release and never gave up on him. She walked from Paris to Vendôme to attend his trial, witnessing the proceeding that would sentence him to death. A few months after Gracchus Babeuf’s execution, she gave birth to their last son, Caius. Félix Lepeletier became a protector of the family (and apparently, Turreau also helped, supposedly adopting Camille Babeuf—one of his very few positive acts). Marie Anne supported her children through various small jobs, including as a market vendor, while never giving up her activism and remaining as combative as ever. (There’s more to her story during the Napoleonic era as well).

We must not forget the role of active women in the insurrections of Year III, against the Assembly, which had taken a more conservative turn by then. Here’s historian Mathilde Larrère’s description of their actions: “In April and May 1795, it was these women who took to the streets, beating drums across the city, mocking law enforcement, entering shops, cafes, and homes to call for revolt. In retaliation, the Assembly decreed that women were no longer allowed to attend Assembly sessions and expelled the knitters by force. Days later, a decree banned them from attending any assemblies and from gathering in groups of more than five in the streets.”

There were also women who fought as soldiers during the French Revolution, such as Marie-Thérèse Figueur, known as “Madame Sans-Gêne.” The Fernig sisters, aged 22 and 17, threw themselves into battle against Austrian soldiers, earning a reputation for their combat prowess and later becoming aides-de-camp to Dumouriez. Other fighting women included the gunners Pélagie Dulière and Catherine Pochetat.

In the overseas departments, there was Flore Bois Gaillard, a former slave who became a leader of the “Brigands” revolt on the island of Saint Lucia during the French Revolution. This group, composed of former slaves, French revolutionaries, soldiers, and English deserters, was determined to fight against English regiments using guerrilla tactics. The group won a notable victory, the Battle of Rabot in 1795, with the assistance of Governor Victor Hugues and, according to some accounts, with support from Louis Delgrès and Pelage.

On the island of Saint-Domingue, which would later become Haiti, Cécile Fatiman became one of the notable figures at the start of the Haitian Revolution, especially during the Bois-Caiman revolt on August 14, 1791.

In short, the list of influential women is long. We could also talk about figures like Félicité Brissot, Sylvie Audouin (from the Hébertist side), Marguerite David (from the Enragés side), and more. Figures like Theresia Cabarrus, who wielded influence during the Directory (especially when Tallien was still in power), or the activities of Germaine de Staël (since it’s essential to mention all influential women of the Revolution, regardless of political alignment) are also noteworthy.

Napoleonic Era

Films could have focused more on women during this era. Instead, we always see the Bonaparte sisters (with Caroline cast as an exaggerated villain, almost like a cartoon character), or Hortense Beauharnais, who’s shown solely as a victim of Louis Bonaparte and portrayed as naïve. There is so much more to say about this time, even if it was more oppressive for women.

Germaine de Staël is barely mentioned, which is unfortunate, and Marie Anne Babeuf is even more overlooked, despite her being questioned by the Napoleonic police in 1801 and raided in 1808. She also suffered the loss of two more children: Camille Babeuf, who died by suicide in 1814, and Caius, reportedly killed by a stray bullet during the 1814 invasion of Vendôme. No mention is made of Simone Evrard and Albertine Marat, who were arrested and interrogated in 1801.

An important but lesser-known event in popular culture was the deportation and imprisonment of the Jacobins, as highlighted by Lenôtre. Here’s an excerpt: “This petition reached Paris in autumn 1804 and was filed away in the ministry's records. It didn’t reach the public, who had other amusements besides the old stories of the Nivôse deportees. It was, after all, the time when the Republic, now an Empire, was preparing to receive the Pope from Rome to crown the triumphant Caesar. Yet there were people in Paris who thought constantly about the Mahé exiles—their wives, most left without support, living in extreme poverty; mothers were the hardest hit. Even if one doesn’t sympathize with the exiles themselves, one can feel pity for these unfortunate women... They implored people in their neighborhoods and local suppliers to testify on behalf of their husbands, who were wise, upstanding, good fathers, and good spouses. In most cases, these requests came too late... After an agonizing wait, the only response they received was, ‘Nothing to be done; he is gone.’” (Les Derniers Terroristes by Gérard Lenôtre). Many women were mobilized to help the Jacobins. One police report references a woman named Madame Dufour, “wife of the deportee Dufour, residing on Rue Papillon, known for her bold statements; she’s a veritable fury, constantly visiting friends and associates, loudly proclaiming the Jacobins’ imminent success. This woman once played a role in the Babeuf conspiracy; most of their meetings were held at her home…” (Unfortunately for her, her husband had already passed away.)

On the Napoleonic “allies” side, Marie Angélique, the widow of Ronsin who later married Turreau, should be more highlighted. Turreau treated her so poorly that it even outraged Washington’s political class. She was described as intelligent, modest, generous, and curious, and according to future First Lady Dolley Madison, she charmed Washington’s political circles. She played an essential role in Dolley Madison’s political formation, contributing to her reputation as an active, politically involved First Lady. Marie Angélique eventually divorced Turreau, though he refused to fund her return to France; American friends apparently helped her.

Films could also portray Marie-Jacqueline Sophie Dupont, wife of Lazare Carnot, a devoted and loving partner who even composed music for his poems. Additionally, her ties with Joséphine de Beauharnais could be explored. They were close friends, which is evident in a heartbreaking letter Lazare Carnot wrote to Joséphine on February 6, 1813, to inform her of Sophie’s death: “Until her last moment, she held onto the gratitude Your Majesty had honored her with; in her memory, I must remind Your Majesty of the care and kindness that characterize you and are so dear to every sensitive soul.”

In films, however, when Joséphine de Beauharnais’s circle is shown, Theresia Cabarrus (who appears much more in Joséphine ou la comédie des ambitions) and the Countess of Rémusat are mentioned, but Sophie Carnot is omitted, which is a pity. Sophie Carnot knew how to uphold social etiquette well, making her an ideal figure to be integrated into such stories (after all, she was the daughter of a former royal secretary).

Among women soldiers, we had Marie-Thérèse Figueur as well as figures like Maria Schellink, who also deserves greater representation. Speaking of fighters, films could further explore the stories of women who took up arms against the illegal reinstatement of slavery. In Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, many women gave their lives, including Sanité Bélair, lieutenant of Toussaint Louverture, considered the soul of the conspiracy along with her husband, Charles Bélair (Toussaint’s nephew) and a fighter against Leclerc. Captured, sentenced to death, and executed with her husband, she showed great courage at her execution. Thomas Madiou's Histoire d’Haiti describes the final moments of the Bélair couple: “When Charles Bélair was placed in front of the squad to be shot, he calmly listened to his wife exhorting him to die bravely... (...)Sanité refused to have her eyes covered and resisted the executioner’s efforts to make her bend down. The officer in charge of the squad had to order her to be shot standing.”

Dessalines, known for leading Haiti to victory against Bonaparte, had at least three influential women in his life. He had as his mentor, role modele and fighting instructor the former slave Victoria Montou, known as Aunt Toya, whom he considered a second mother. They met while they were working as slaves. They met while both were enslaved. The second was his future wife, Marie Claire Bonheur, a sort of war nurse, as described in this post, who proved instrumental in the siege of Jacmel by persuading Dessalines to open the roads so that aid, like food and medicine, could reach the city. When independence was declared, Dessalines became emperor, and Marie Claire Bonheur, empress. When Jean-Jacques Dessalines ordered the elimination of white inhabitants in Haiti, Marie Claire Bonheur opposed him, some say even kneeling before him to save the French. Alongside others, she saved those later called the “orphans of Cap,” two girls named Hortense and Augustine Javier.

Dessalines had a legitimized illegitimate daughter, Catherine Flon, who, according to legend, sewed the country’s flag on May 18, 1803. Thus, three essential women in his life contributed greatly to his cause.

In Guadeloupe, Rosalie, also known as Solitude, fought while pregnant against the re-establishment of slavery and sacrificed her life for it, as she was hanged after giving birth. Marthe Rose Toto also rose up and was hanged a few months after Louis Delgrès’s death (if they were truly a couple, it would have added a tragic touch to their story, like that of Camille and Lucile Desmoulins, which I have discussed here).

To conclude, my aim in this post is not to elevate these revolutionary, fighting, or Napoleonic-allied women above their male counterparts but simply to give them equal recognition, which, sadly, is still far from the case (though, fortunately, this is not true here on Tumblr).

I want to thank @aedesluminis for providing such valuable information about Sophie Carnot—without her, I wouldn't have known any of this. And I also want to thank all of you, as your various posts have been really helpful in guiding my research, especially @anotherhumaninthisworld, @frevandrest, @sieclesetcieux, @saintjustitude, @enlitment ,@pleasecallmealsip ,@usergreenpixel , @orpheusmori ,@lamarseillasie etc. I apologize if I forgot anyone—I’m sure I have, and I'm sorry; I'm a bit exhausted. ^^

#frev#french revolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#women in history#haitian revolution#slavery#guadeloupe#frustration

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historians having takes on frev women that make me go 😐 compilation

Sexually frustrated in her marriage to a pompous civil servant much older than herself, [Madame Roland] may have found Danton’s celebrated masculinity rather uncomfortable. Danton (1978) by Norman Hampson, page 77.

The Robespierres sent their sister to Arras because that was their hometown, the family home, where they had relatives, uncles, aunts and friends, like Buissart who they didn’t cease to remain in correspondence with, even in the middle of the Terror. There, among them, Charlotte would not be alone; she would find advice, rest, the peace necessary to heal her nervousness and animosity. Away from Mme Ricard, who she hated, away from Mme Duplay, who she detested, she would enjoy auspicious calmness. It is Le Bon that the Robespierres will charge with escorting their sister to this neccessary and soothing exile. […] If there is a damning piece in Charlotte Robespierre's case, it is this one (her interrogation, held July 31 1794). She seems to be caught in the act of accusing this Maximilien whom she rehabilitates in her Memoirs. She is therefore indeed a hypocrite, unworthy of the great name she bears, and which she dishonors the very day after the holocaust of 10 Thermidor. Charlotte Robespierre et Guffroy (1910) in Annales Révolutionnaires, volume 3 (1910) page 322, and Charlotte Robespierre et ses mémoires (1909) page 93-94, both by Hector Fleishmann.

Elisabeth, as she was popularly called, was barely past her twelfth birthday, younger even by three years than Barere’s own mother when she was given in marriage. On the following day the guests assembled again in the little church of Saint-Martin at midnight to attend the wedding ceremony of the handsome charmer and the bewildered child. Dressed in white, clasping in her arms a yellow, satin-clad doll that Bertrand had given her — so runs the tradition — she marched timidly to the altar, looking more like a maiden making her first communion than a woman celebrating a binding sacrament. Perhaps the doll, if doll there was, filled her eye, but certainly she could not fail to note how handsome her husband was. Bertrand Barere; a reluctant terrorist (1962) by Leo Gershoy, page 32.

The young nun who bore the name of Hébert did not hide her fate. She did not wish to prolong a life stifled from her childhood in the cloister, branded in the world by the name she bore, fighting between horror and love for the memory of her husband, unhappy everywhere. Histoire des Girondins (1848) by Alphonse de Lamartine, volume 8, page 60.

Lucile in prison showed more calmness than Camille. Before the tribunal, she seemed to possess neither fear nor hope, she denied having taken an active role in the prison conspiracy. What did it matter to her the answer they were trying to extract from her? They said they wanted her guilty? Very well! She would be condemned and join Camille. This was what she said again when she was told that she would suffer the same fate as her husband: ”Oh, what joy, in a few hours I’m going to see Camille again!” Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un couple dans la tourmente (1986) by Jean Paul Bertaud, page 293.

What did it matter to Lucile whether she was accused or defended? She had no longer any pretext for living in this world. She was one of those heroines of conjugal love who are more wife than mother. Besides, Horace lived, and Camille was dead. It was of the absent only that she thought. As for the child, would not Madame Duplessis act a mother's part to him? The grandmother would watch over the orphan. If Lucile had lived, she could have done nothing but weep over the cradle, thinking of Camille. Camille Desmoulins and his wife; passages from the history of the Dantonists founded upon new and hitherto unpublished documents (1876) by Jules Claretie.

Having been widowed at the age of 23 [sic] years, Élisabeth Duplay remarried a few years later to the adjutant general Le Bas, brother of her first husband, and kept the name which was her glory. She lived with dignity, and all those who have known her, still beautiful under her crown of white hair, have testified to the greatness of her sentiments and austerity of her character. She died at an old age, always loyal to the memory of the great dead she had loved and whose memory she, all the way to her final day, didn’t cease to honor and cherish. As for the lady of Thermidor, Thérézia Cabarrus, ex-marquise of Fontenay, citoyenne Tallien, then princess of Chimay, one knows the story of her three marriages, without counting the interludes. She had, as one knows, three husbands living at the same time. Now compare these two existances, these two women, and tell me which one merits more the respect and the sympathy of good men. Histoire de Robespierre et du coup d’état du 9 thermidor (1865) by Louis Ernest Hamel, volume 3, page 402.

Fel free to comment which one was your favorite! 😀

#frev#french revolution#frev compilation#hampson: if women were uncomfortable around danton it’s because they were sexually frustrated!#fleishmann: two men in their 30s can ultimately decide what’s best for their sister who’s also in her 30s#also it’s totally unreasonable for charlotte to disown her brothers after their death when her life was possibly in danger#(and even though they pretty much disowned her while they were still alive)#lamartine claretie bertaud: françoise and lucile wanted to die since there was no longer any point to their lives after the husbands died#hamel: a good way of finding out which side was bad and which side was good is to look over how slutty the women on each side were#wow are you seriously surprised the view of women held by 19th century authors isn’t exactly top modern?#…no comment#claretie should technically get a pass since he thought the journal of sanson was an authentic source#But it was so spectacular i couldn’t contain myself#also a shame i couldn’t remember where i read the interpretation that the reason simond évrard was wary of charlotte corday#was bc she might seduce marat when alone with him

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frev (and 18c?) fresco at the Bastille metro station. Thanks to @robespapier for suggesting we see it because it's everything:

#art#frev#someone drew moustache on women#but only now i see that they drew over the phrygian cap#and is that gilbert on the third one#and yes it's jj covered by the sign#and i assume camille in the last one

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

rip robespierre u would’ve been an amazing lesbian

#frev#french revolution#maximilien robespierre#this is gonna make the saintspierre ppl maddddd 😞😞😞#peace and love tho#some men would just be better if they were born women and if they were lesbians and robespierre is one of them#this is my petition to rewrite the french revolution and make maxime a woman#put me on fox news for ts

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucille Desmoulins moment (she is not ok)

#lucille Desmoulins#frev#frev community#french revolution#tea art 🎨#I LOVE WOMEN!!!!!!!! I LOVE SAD WOMEN!!!!!!!#at first i only wanted to draw a silly Lucille being melodramatic and overly depressed while writing her many iconic quotes in her diary#buuuutttt ended up making an entire freakin narrative????#please tell me this looks good#i wish this was compositioned better#WHY DOES TUMLBR MAKE MY PICTURES LIKE THAT????#oklo makes a post

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

hilarious to me when people use robespierre's recommendation to close the SRRC as proof that he was some kind of raging misogynist. my friend they were burning down buildings and killing shopkeepers.

#god forbid women do anything#but like. the reason it was closed was not bc they were women#it was bc they were causing Problems for the city#french revolution#frev#although they were sorta based about it#I get saying “we cannot let you murder and vandalize”#esp in a time of political instability#pigeon.txt

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is it often said that Louise Danton (born March 3, 1776) was 16 years old at the time of her first marriage (June 1793, so she was actually 17)?

It's a simple calculation that can be corrected, so I really wonder why the error is still prevalent as it is today.

#I guess this is mainly Michelet's fault for spreading prejudice against her (and Gabrielle)...#Seventeen is too young to get married but mistakes should be corrected (but I don't know much about age of marriage for women at that time)#and there is a lot of mystery in this marriage#anyway we need more research on the women in frev#frev#louise sébastienne gély#louise danton#danton

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Development of French Women’s Rights — according to Carla Hesse

Women’s status in relation to their husbands during the Revolutionary era:

“Legal reform, however, did not go so far as to render the civil status of married women equal to that of their husbands. This radical proposal, initiated by the legislator Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès, was definitively rejected by the Convention in 1793. So even at the revolutionary high water mark, the legal standing of married women still remained contingent to a certain extent on the will and consent of their husbands.”

Divorce and other rights in the New Regime:

“By abolishing in 1791 guild restrictions imposed by the former regime, revolutionary legislators opened all professions, including publishing and printing, to women, as long as their husbands (if they were married) consented. Prescriptive primogeniture was abolished and divorce legalized in September of 1792.”

***Divorce was legalized in September 1792, but abolished in 1816 during the Restoration after the fall of Napoleon.

Women’s status in relation to their husbands under the Old Regime:

“Under the Old Regime, in short, a married woman’s right to publish her work was contingent on her husband’s consent. She was not permitted to sign any contracts without her husband’s consent, she could not, on her own, make a legally binding arrangement with a publisher. And, if she did publish, the legal claim to her work belonged to him unless he explicitly authorized his wife to act on her own behalf.”

“Few women wrote and published under the Old Regime, and many of those who did were legally separated, unmarried, or widowed. Perhaps the two most widely read women writers of the eighteenth century, Mme de Gaffigny and Mme Riccoboni, for example, did not in fact begin their literary careers until after they were separated from their husbands.”

A conclusion from the author:

“They were denied the vote in 1789, prohibited from political mobilization during the Terror, denied civil equality within marriage.”

Source: Carla Hesse, The Other Enlightenment: How French Women Became Modern

#Carla Hesse#The Other Enlightenment: How French Women Became Modern#women#napoleon#napoleonic era#women’s history#Marcel Garaud La Révolution française et la famille#history#french history#napoleonic#french revolution#frev#France#quotes#révolution française#la révolution française

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decent Dad Contest:

in light of the already depressing recent poll and and even more depressing thread, I think it's best to do a nicer poll this time!

Thanks to @anotherhumaninthisworld for coming up with the idea and providing info about Camille's dad!

1. Jean Benoît Nicolas Desmoulins

Supportive of his son's revolutionary goals while also expressing worry about his safety (perfectly reasonable)

Seemed to have a lot of patience with his son (which is saying something, given that it's Camille we're talking about... you need all the patience you can get)

Most likely rooting for his relationship with Lucile

Ready to give his son advice

"No, my son, I am not and can never be of your enemies (...) I am and always will be your friend and your best friend"

wrote a letter to the public prosecutor to try and plea for his son's life (in which he mentioned that he's proud of him: fellow-citizen Desmoulins, who until now has held himself honoured in being the father of the foremost and most unflinching of Republicans)

2. Denis Diderot

named his daughter Angélique after his beloved sister and mother

the shared love for their daughter is assumed to be what kept Diderot's and his wife's shaky marriage together for a long time

used the money he got from working on the Encyclopédie to secure the best possible tutors for his daughter

Went again the standards of girls' education of his time (usually focused on singing and piano lessons), instead choosing to teach her to 'think logically' and secure classes in subjects such as history, geography, or musical theory

"I shall teach her, if I can, to endure [the difficulties of life] with fortitude"

there's a reasonable evidence that he believed in his daughter's 'genius' as a composer, and even had the prelude she composed printed (you can listen to it here!)

I recommend this great post and this article for further reading if you're interested!

Also take this with the grain of salt, especially the Diderot one, I should be packing for a trip and didn't have that much time to dig for sources.

Also unfortunately some not completely enlightened views on women authors by our enlightenment philosopher... but hey, at least he believed his daughter to be special, which is kind of sweet? The female question in the 1700s is complex okay...

#this is hard#vote with your heart I guess?#polls#also so glad I've discovered A's music!#frev#french revolution#frev community#frevblr#desmoulins#camille desmoulins#jean desmoulins#denis diderot#age of enlightenment#enlightenment#philosophy#philosophy memes#women's history#Angélique Diderot#history#history memes#history polls#1700s#18th century#music

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the website:

The Elbeuf Letters database provides a digital edition of the writings of the duchess of Elbeuf, a hostile witness to Revolutionary events between 1788 and 1794.

#frev#french revolution#18th century history#women in history#french history#throwing this out to the adjacent frev folks in case you all haven't seen it yet!

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you, Elisabeth Le Bas!

Thank you for these touching memoirs. Her modesty also moved me, as she is clearly one of those women behind the scenes who encouraged their revolutionary husbands, who would not have been as effective without them. She possesses an extraordinary strength of character and integrity that many men should have been inspired by instead of placing their individual interests first. The revolution could have been saved (no need to specify who I am targeting here). Although her memoirs may at first seem to portray a woman who simply supports those she loves, it is actually much deeper than that. She attended political debates with Charlotte Robespierre, showing that they were far more politically engaged than they appeared. By the way, I have a theory about Philippe Le Bas based on an excerpt from Elisabeth Le Bas:

"It was the day when Marat was borne in triumph to the Assembly that I saw my beloved Philippe Le Bas for the first time.

I found myself, that day, at the National Convention with Charlotte Robespierre. Le Bas came to greet her; he stayed with us for a long time and asked who I was. Charlotte told him that I was one of her elder brother’s host’s daughters. He asked her a few questions about my family; he asked Charlotte if we came to the Assembly often, and said that on a particular day there would be a rather interesting session. He urged her to come to it."

I haven’t found any evidence that Le Bas defended the rights of womens citizens (I hope I’m wrong because I really like him as a revolutionary, so feel free to correct me). Yet, I have no valid reason to doubt what he said to Charlotte Robespierre about encouraging these two women to attend a session of the Assembly. I get the impression that Le Bas was one of those men who valued women’s political opinions, had no problem with them attending political sessions, but didn’t see the point of them participating more actively in political life. I imagine he had no objections to discussing it privately with Elisabeth.

Philippe and Elisabeth Le Bas form such a touching couple (I almost applauded when they were finally able to marry), and I really liked that, together with Henriette Le Bas (another woman who is too unknown in the revolution, but fortunately Tumblr is here to bring them out of the shadows), she accompanied her husband and Saint-Just (she was one of the many women who accompanied the revolutionaries on their missions, like Charlotte Robespierre, Sophie Momoro, etc.).

I also really appreciated the relationship she had with Eleonore Duplay, where we also see the courage of her sister in adversity. Paradoxically, it’s in Elisabeth Le Bas’s memoirs that I began to appreciate Charlotte Robespierre. Charlotte Robespierre’s memoirs contain quite a few inaccuracies, as other Tumblr users have pointed out, and I thought to myself, it’s impossible, she’s way too “saintly,” I don’t believe it for a second (not to mention that she comes across as too apolitical, but I imagine those who helped write the memoirs didn’t want a thinking woman). Here, thanks to certain passages from Elisabeth and what we know from the Mathons, we have proof that she is certainly not a saint (no one is), but she’s not a heartless, toxic, or selfish woman as I’ve seen (not on Tumblr but on other forums, where they oddly bash Robespierre but blame Charlotte for disowning her brother; those who say these things are inconsistent, plus I’d like to see how they would have reacted if they had faced the same threat as Charlotte). She is a woman with touching qualities (like her kindness towards Elisabeth, her desire to accompany her brother on a mission, when she designated Mademoiselle Mathon as her heir, or that at the end of her life, she wanted to rehabilitate her brothers) but also with weaknesses (I would start with her completely inaccurate memoirs, I think the disagreement between Madame Duplay, Eleonore, and Charlotte involved shared faults, just like the dispute between Augustin and Charlotte, especially the letter Augustin wrote to Maximilien about Charlotte, etc.). Thanks to Elisabeth Le Bas’s memoirs, Charlotte Robespierre is neither a monster nor a too-perfect being, she is just a human being. By the way, I don’t blame her for disowning her family name and her brothers temporarily because the danger could have been real. She was a civilian who didn’t seek trouble, and in that respect, it was trouble (more precisely, the Thermidorians) that came to her. I also don’t blame her for asking Bonaparte for a pension and continuing to receive one under Louis XVIII because life for a single woman was very hard at that time. It took extraordinary strength of character to avoid doing all that, and not many people had it. Where I do criticize Charlotte Robespierre is for embellishing the reality concerning her in her memoirs.But it was very sad that she was not able to reconcile with her brothers especially Augustin before she died because none of them seem toxic to me. If France and the revolution had no longer been in danger, if they had survived, I think they would have reconciled, but I can't speak for them.

Returning to Elisabeth’s memoirs, I smiled when she idealized the revolutionaries she was close to, like the Robespierre brothers or Saint-Just, although after recognizing many of his qualities, she said he could sometimes be severe due to his great love for the country and the revolution. But it’s normal that she idealized them and defended them loyally because she was simply being loyal to the revolutionary struggles they were leading and in which she believed, even though it would have been good to see their flaws in her memoirs. Memoirs are always subjective, even from an honest person like Elisabeth Le Bas. Despite everything, she is attached to her country and is capable of making a judgment when she says in the excerpt, “Nevertheless, he needed to leave; Robespierre, who had great confidence in Le Bas because he knew his wise and prudent character well, had chosen him to accompany Saint-Just, whose burning love of the patrie sometimes led to too much severity, and who had a tendency to get carried away.” On the other hand, what troubles me about this statement is that normally, a person is not sent on a mission based on the will of just one other person; it usually requires the majority of votes within the CPS or the CSG (sometimes in the Convention). But we see that Elisabeth stays in the background yet makes a thoughtful political judgment to better safeguard the endangered French Revolution.

However, I didn’t like that Elisabeth constantly put herself down by describing herself as scatterbrained when everything indicated that she was not. I was saddened by the tragic fate of Philippe Le Bas, even though we all knew it was inevitable. At least they were able to say goodbye. At least he died before seeing the tragic outcome of the revolution. I found Madame Duplay’s death unfair. Poor Duplay family, who went through one tragedy after another but found the strength to bounce back. I admired Eleonore for helping Elisabeth during her most tragic moments in prison. I applauded when Elisabeth Le Bas showed astonishing courage in front of her adversaries from prison to her release. She never asked for anything and displayed extraordinary strength.

Even though I wouldn’t have blamed her for abandoning the revolution to survive with her son in such difficult times, she didn’t do it, whereas some “revolutionaries” greedy for their wallets destroyed the revolution, endangered France, and undermined the revolutionary people's efforts for social progress that had begun since 1789. The obligation of loyalty to the revolution that deputies like Fouché, Barras, or a general named Bonaparte should have respected was found in the daughter and wife of an authentic revolutionary (especially in the worst moments). Honor to her (and to the many men and women like Elisabeth) and shame on all those greedy ones (I must admit that my language is blunt and could be more nuanced if making a historical judgment, but I’m more in the realm of value judgment, so I feel I can allow myself some liberties, sorry for the fans of theses characters it's only my view).

On a more positive note, thank you, Elisabeth Le Bas, for fighting against this all-too-common black legend of the revolution through your memoirs.

Thank you for your journey as a fighter. If only the greedy deputies I mentioned earlier had a quarter of your integrity and courage and remembered that they were there to serve the people, as they are in their positions solely because of the people and thanks to them, the revolution would surely have lasted longer.

Thank you, Elisabeth, for all you did with so many others. May your life serve as an example and a source of strength for us.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since today is Charlotte Robespierre’s 163’th birthday, I thought I’d attempt something I’ve not seen anyone else yet do, which is to write a mini biography over her entire life. I’ve already translated a study from the 1960s which deals with Charlotte, but since it’s a bit all over the place and spends almost more time describing the people Charlotte had any sort of connections with rather than Charlotte herself, I decided to try to make some more sense of things by a more chronological approach.

Marie Marguerite Charlotte de Robespierre was born in Arras on February 5 1760, around half past two in the afternoon. Her baptism record, written three days later, goes as follows:

”Today is the eighth day of the month of February, the year 1760. We priests of the parish of Saint-Étienne of towns and Diocese of Arras, have supplemented the ceremonies of the baptism for a girl born around half past two in the afternoon in said parish in the legitimite marriage of maître Maximilien-Barthélemy-François de Robespierre, lawyer at the Provincial Council of Artois, and of demoiselle Jacqueline-Margueritte Carraut, her father and mother; she was delivered by us parish priest the day after her birth, six of the same month and year as above, with the permission of the bishopric dated the same day signed by Le Roux, vicar general, and below, by ordinance Péchena. The godfather was master Charles-Antoine de Gouve, adviser to the King and his attorney for the town and city of Arras, subdelegate of the intendant of Flanders and Artois, in the department of Arras, of the parish of Saint-Jean in Ronville, and the godmother demoiselle Marie-Dominique Poiteau, widow of Sieur François Isambart, procurator to the said provincial council of Artois, of the parish of Saint-Aubert, who gave her the name Marie-Marguerite-Charlotte, and who signed with us the parish priest, and the father here present, the same act on the day and year mentioned above. The child was born on the fifth. Marie Dominique Poiteau De Gouve Derobespibrre Willart, parish priest of Saint-Etienne.”

That Charlotte wasn’t baptisted until three days after her birth may be a sign that her parents for a moment feared for her life, considering Charlotte’s three siblings — the older Maximilien (born 1758), and younger Henriette (1761) and Augustin (1763) — all were baptised the same days they had been born.

Charlotte would later recall the memory of her mother Jacqueline (1735) with fondness. ”Oh! Who would not keep the memory of this excellent mother!” she wrote in her memoirs. ”She loved us so! Nor could Maximilien recall her without emotion: every time that, in our private interviews, we spoke of her, I heard his voice alter, and I saw his eyes soften. She was no less of a good wife than a good mother.” But they did not get to keep her for long — on July 4 1764 Jacqueline gave birth to a baby who didn’t make it past his first twenty-four hours alive, and was buried in the Saint-Nicaise cemetery without having received a name. She was not to survive him for much longer, twelve days later she died as well, a few days before her twenty-ninth birthday. The funeral held the following day was, according to the mortuary act, attended by Jacqueline’s brother Augustin and Antoine-Henri Galbaut, Knight of Saint-Louis, assistant major of the Citadel, but not by her husband. In her memoirs, Charlotte reported that Jacqueline’s death had been ”a lightning strike to the heart” for him — ”He was inconsolable. Nothing could divert him from his sorrow; he no longer pleaded, nor occupied himself with business; he was entirely consumed with chagrin. He was advised to travel for some time to distract himself; he followed this advice and left: but, alas! We never saw him again; the pitiless death took him as it had already taken our mother.”

Different documents tell us that the father actually didn’t leave Arras until December 1764, five months after Jacqueline’s death, after which he sporadically appeared in his hometown, sometimes for months at a time. The last known stay is from 1772. It is nevertheless probable that he no longer was in a state to look after his children after the death of his wife, and therefore, as Charlotte recounts in her memoirs, quickly handed them over to different relatives. Charlotte and Henriette, seperated by an age gap of less than two years, were therefore sent to live with their two unmarried paternal aunts, Henriette and Eulalie de Robespierre. According to contemporary Abbé Proyart, who knew the family, the aunts ”lived in a great reputation for piety.” Maximilien and Augustin, the latter still with his wetnurse, were in their turn taken in by their maternal grandparents. According to Charlotte, the loss of their parents had left a big mark on the former:

”He was totally changed. Before that point he had been, like all children of his age, flighty, unruly, rash; but since from this time he saw himself, in the quality of eldest, as the head of the family, he became poised, reasonable, laborious; he spoke to us with a sort of imposing gravity; if he joined in our games, it was to direct them. He loved us tenderly, and there were no caresses that he did not lavish on us […] He had been given pigeons and sparrows which he took the greatest care of, and close to which he often came to pass the moments which he did not consecrate to his studies.”

The children were reunited every Sunday, during which Maximilien would show his sisters his drawings and place his sparrows and pigeons into their cupped hands. One time, Charlotte and Henriette begged him to let them have one of his birds, and after much hesitation he gave in, much to their joy. Unfortunately, some days later the girls forgot the pigeon in the garden during a stormy night, by which it perished. When he found out about it Maximilien’s tears flowed, and he rained reproaches on Charlotte and Henriette and refused to give his birds to them when he left to study in Paris. ”It was sixty years ago,” Charlotte writes in her memoirs, ”that by a childish flightiness I was the cause of my elder brother’s chagrin and tears: and well! My heart bleeds for it still; it seems to me that I have not aged a day since the tragic end of the poor pigeon was so sensitive to Maximilien, such that I was affected by it myself.”

On December 30 1768, Charlotte was sent off to Maison des Sœurs Manarre, — “a pious foundation for poor girls, who may be admitted from the age of nine to eighteen, to be fed, brought up under some good mistress of virtue and to improve oneself in lacing and sewing or in another thing which one will judge useful; to learn to read and write until they are able to serve and earn a living,” situated just across the border in Tournai (modern-day Belgium). She was actually a few months too young to be enrolled, but an exeption was made in her favor, obtained by the influence of her godfather Charles-Antoine de Gouve. Two years later Charlotte was joined at the convent school by Henriette, who in her turn was enrolled without yet having a scolarship. Perhaps this is a sign that their relatives were struggling to provide for the four orphans and thus had to send them away as quickly as possible. On October 1769, Maximilien was enrolled at the College of Louis-le-Grand in Paris, his taste for study having awarded him with a scholarship to the prestigious school, while Augustin in his turn was sent off to the College of Duoai. The children were thus dispersed and no longer saw anything of each other, except for in the summers when they were reunited in Arras. According to Charlotte these were days of great joy that passed too quickly, even if many of these years were also ”marked by the death of something cherished.” In 1770, their paternal grandmother died, in 1775 their maternal grandmother and in 1778 their maternal grandfather. 1777 saw the death of their father, who at that point was living in Munich, but it’s unknown if Charlotte and her relatives actually found out about it or not. Finally, on March 5 1780, Henriette was buried, a little more than two months after her eighteenth birthday. According to Charlotte, the death of the sister had a big impact on Maximilien, it rendered him ”sad and melancholy” and he wrote a poem in her honor. She does not, on the other hand, report how the death affected her, Henriette undeniably being the family member she had spent the most time together with… Nevertheless, she did not get a chance to say goodbye, as the names of neither her nor her brothers feature on the mortuary act of Henriette or any of the other dead relatives.

One year after Henriette’s death, Maximilien graduated from Louis-le-Grand, nine days after his twenty-third birthday. Now a fully trained lawyer, he returned to Arras to work as such. We don’t know when Charlotte left the convent school, but she soon enough joined her older brother. Augustin, however, Charlotte continued to see very little of, as Maximilien arranged for him to take over his scholarship and started his studies at Louis-le-Grand on November 3 1781. He didn’t return until 1787.

The siblings had obtained half of the 8242 livres from when their late grandfather’s brewery was sold to their maternal uncle Augustin in 1778, but they were still in a rough financial situation. In 1768 their father had resigned from any inheritance whatsoever from his mother ”both for me and my children,” a wish he had then repeated both in 1770 and 1771. In 1766, he had also borrowed seven hundred livres from his sister Henriette which he never paid back, leading to some tension between Henriette, her husband and Maximilien in 1780.

Charlotte and Maximilien at first moved into a house on Rue du Saumon, but their stay there was short — already in late 1782 they were forced to leave the house to instead move in with aunt Henriette on Rue Teinturiers. According to the memoirs of Maurice-André Gaillard, Charlotte told him in 1794 that she and Maximilien weren’t exactly welcomed with open arms by Henriette’s husband — ”It’s strange that you didn’t often notice how much [his] brusqueness and formality made us pay dearly for the bread he gave us; but you must also have noticed that if indigence saddened us, it never degraded us and you always judged us incapable of containing money through a dubious action.”

Eventually, Charlotte and Maximilien moved again, to Rue des Jésuites, and finally, in 1787, they moved from there Rue des Rapporteurs 9. There they were soon enough joined by Augustin, by now too a qualified lawyer. According to Charlotte’s memoirs, the bond between the three siblings was strong — ”good harmony would not have ceased for a sole instant to reign among us.” While her brothers worked, Charlotte took care of the house. We know the name of one of her domestics — Catherine Calmet, who helped Charlotte out for six months. When Calmet was arrested in Lille in 1788, Maximilien wrote a letter pleading in her favour: ”[Calmet’s] conduct appeared to me faultless during the time she stayed with me; I rejoice in her slightest recovery. As for the certificate you’re speaking to me about, my sister has told me that the girl brought it with her.”

The siblings had many friends. One of them was mademoiselle Dehay, who in 1782 gave Charlotte and Maximilien a cage of canaries which they both appriciated a lot. ”My sister asks me, in particular,” Maximilien wrote to her on January 22, to show you her gratitude for the kindness you have had in giving her this present, and all the other feelings you have inspired in her.” Mademoiselle Dehay would later also do other animal related favors for the two. ”Is the puppy you are raising for my sister as sweet as the one you showed me when I passed through Béthune?” Maximilien asked her in 1788. ”Whatever it looks like, we receive it with distinction and pleasure.”

Charlotte leaves a long list of Maximilien’s closest friends in her memoirs. Of those included there, important for her story as well is her brother’s fellow lawyer Antoine Buissart, ”intensely estimable savant” and his wife Charlotte. The couple lived on rue du Coclipas, a ten minute walk from Rue des Rapporteurs, and would become close with all three siblings. Another one of Maximilien’s colleagues that would play an important role in Charlotte’s life was Armand Joseph Guffroy, who, like Charlotte, witnessed Maximilien’s uneasiness when it came to the death penalty while the two worked as judges together.

Then there was the family — maternal uncle Augustin Carraut who with his wife Catherine Sabine (1740) had had four children — Augustin Louis Joseph (1762), Antoine Philippe (1764), Jean-Baptiste Guislain (1768) and Sabine Josephe (1771). The two paternal aunts Eulalie and Henriette had married in 1776 and 1777 respectively — Henriette to Gabriel-François Durut, doctor of medicine in Arras at the College d’Oratoire, Eulalie to Robert Deshorties, merchant and royal notary in Arras. Deshorties had five children from his previous marriage — two sons and three daughters. One of the daughters had according to Charlotte been courting Maximilien since 1786 or 1787. ”She loved him and was loved back. […] Many times it had been talk of marriage, and it is very probable Maximilien would have wedded her, if the the suffrage of his fellow citizens had not removed him from the sweetness of private life and thrown him into a career in politics.” However, if such plans existed, they were soon broken up by the revolution, and the step-cousin instead got engaged to another lawyer, Léandre Leducq, who she married on August 7 1792.

Charlotte was perhaps also finding love. Joseph Fouché was a science professor from Nantes, a year older than herself, who had joined her uncle Durut at the College of Arras in 1788. ”Fouché”, Charlotte writes in her memoirs, ”was not handsome, but but he had a charming wit and was extremely amiable. He spoke to me of marriage, and I admit that I felt no repugnance for that bond, and that I was well enough disposed to accord my hand to he whom my brother had introduced to me as a pure democrat and his friend.” But somehow, this engagement too ran out into the sand, and Fouché got married to Bonne Jeanne Coiquaud in 1792.

Life changed on April 26 1789, when Maximilien was elected as a deputy for the Estates General and settled for Paris for an indefinite period of time. Letters from Augustin to the family friend Antoine Buissart reveal that the he went to visit his brother in September 1789, as well as from September 1790 to March 1791. Charlotte may not have been so fond of Augustin’s trips, ”My sister must be very cross with me,” Augustin wrote to Buissart on November 25 1790, ”but she easily forgets, that consoles me, I will try to bring her what she wants.” Charlotte herself couldn’t or wouldn’t join him — ”I did not see [Maximilien] for the duration of the Constituent Assembly,” she affirms in her memoirs. In November 1791, after the closing of said assembly, Maximilien made a visit back to Arras, Charlotte, Augustin and Charlotte Buissart meeting him at the coach depot in Bapaume. In her memoirs, Charlotte could still remember the pleasure of getting to embrace her brother after not having seen him for two years. However, Maximilien’s stay was short, and on November 27 he was back in Paris to never see his hometown again.

Maximilien, like Augustin, frequently wrote long letters to Buissart, telling him about the situation developing in the capital. He did however never ask him to say hello to his siblings in them, nor do we have any conserved letters adressed from him to them. Charlotte still affirms that ”we wrote to each other often, and [Maximilien] gave me the most emphatic testimony of friendship in his letters. “You (vous) are what I love the most after the patrie,” he told me.” According to Paul Villiers, who claimed to have been Maximilien’s secretary for seven months in 1790, the latter also sent part of his deputy’s salary to ”a sister in Arras, whom he had a lot of affection of for.”

But despite the extra money, Charlotte and Augustin were having a hard time. “We are in absolute destitution,” the latter wrote to Maximilien in 1790, ”remember our unfortunate household.” Joseph Lebon, a former priest soon to be mayor of Arras, wrote to Maximilien on August 28 1792 that “the bearer of this letter, Démouliez, has planned arrangements with your brother, to procure for him the execrable silver mark.” They also had to deal with the loss of some more loved ones, as Henriette and Eulalie, the aunts that had had the raising of Charlotte and her sister, both died in 1791.

Even if Charlotte was unable to go to Paris with her younger brother, she was still politically active on a local level. This is shown through a letter dated April 9 1790 which she sent Maximilien:

”We’ve just received a letter from you, dear brother, dated April 1, and today it is the 9th. I don’t know if this delay is the fault of the person to whom you gave it. Please send it to us directly next time. At the moment, I’ve just learned that one is happy with the patriotic contribution. M. Nonot, always a good patriot, has just told me this news with this one which he has from M. de Vralie and which greatly formalizes those who love liberty. I don't know if you know that a whip-round was made about four months ago for the relief of the poor in the town. Each citizen contributed to it according to his faculties. Today the municipal officers are of the opinion that the whip-round should continue for another three months. There are many people who no longer want to pay. They give the reason that the poor should not be fed idle, that they should be made to work demolishing the rampart of the town. The mayor, who apparently knew that one would refuse to pay, said that if one refused to pay, he would obtain authorization from the National Assembly and tax himself what must be payed. If M. Nonot is not mistaken, for the remark is so ridiculous that I cannot persuade myself that it is true, M. de Fosseux will be busy, for there are those who will refuse on purpose in order to see what that will result in. I don't know if my brother has forgotten to tell you about Madame Marchand. We fell out with her! I took the liberty of telling her what the good patriots must have thought of her paper, and what you thought of it. I reproached her for her affectation of always putting infamous notes for the people, etc. She got angry, she maintained that there were no aristocrats in Arras, that she knew all the patriots, that only the hotheads found her paper aristocratic. She says a lot of nonsense to me and since then she no longer sends us her paper. Take care, dear brother, to send what you promised me. We are still in great trouble. Farewell, dear brother, I embrace you with the greatest tenderness. If you could find a position in Paris that suits me, if you knew one for my brother, because he will never be anything in this country. I am not sending you this letter by post in order to give the person who gives it to you the opportunity of getting to know you, which he has long wanted.”

However, contrary to her prediction that Augustin ”would never be something,” her younger brother was in fact elected to the council of administration of Pas-de-Calais in 1791, and in August 1792 prosecutor-syndic of the commune of Arras and president of les Amis de la Constitution. Finally, one month later, on September 16, Augustin was elected to fill a seat in France’s new government body the National Convention.

Thus, Charlotte’s hopes of going to Paris were finally coming true, as this time she was not left behind when Augustin once again set off for the capital. The first evidence of their arrival is from October 5, when Augustin’s name is first mentioned in the debates of the Jacobin Club in Paris. However, it’s possible Charlotte went to Paris still earlier, as she in her memoirs claims to have stood witness to a conversation between her older brother and his friend Jérôme Pétion ”a few days” after the Paris prison massacres between September 2-4. Maximilien would have reproached Pétion for not having interposed his authority to stop the excesses, to which the latter dryly would have replied: ”All I can tell you is that no human power could have stopped them.” Pétion also mentioned a meeting between him and Maximilien on the subject, but in his version it was rather he who accused Maximilien of doing a lot of harm — ”your denunciations, your alarms, your hatreds, your suspicions, they agitate the people; explain yourself; do you have any facts? Do you have any proof?”

Regardless, Augustin and Charlotte settled in the front of an apartment on 366 Rue Saint-Honoré, where their brother lodged since 1791. Owner of the house was one Maurice Duplay (1738), who lived there with his wife Françoise-Éleonore (1739) and their unmarried daughters Éleonore (1767/1768), Victoire (1769) and Élisabeth (1772), son Maurice (1778) and nephew Simon (1774). According to the memoirs of the youngest daughter, Élisabeth, Maximilien had become something of an additional family member — ”He was so nice! […] He had a profound respect for my father and mother; they too regarded him as a son, and we as a brother.” The letters Maximilien wrote to Maurice while on the short trip in Arras reveal that the feelings seem to have been mutual — ”Please present the testimonies of my tender friendship to Madame Duplay, to your young ladies, and to my little friend.”

Charlotte on the other hand, soon found herself on second thoughts regarding the family, or, to be more exact, Françoise Duplay. ”I should tell the whole truth,” she writes in her memoirs, ”I have nothing but praise for the demoiselles Duplay; but I would not say the same for their mother, who did me much wrong; she looked constantly to put me in bad standing with my older brother and to monopolize him.” According to Charlotte, the family exercised an ascendancy over Maximilien — ”founded neither on wit, since Maximilien certainly had more of it than Madame Duplay, nor on great services rendered, since the family among whom my brother lived had not for some time been in a position to render them,” which her older brother was simply too kind to stand against. Before, no one had interfered with Charlotte’s management over the domestic square, but now she was subordinate to Françoise, who treated Charlotte badly — ”if I were to report everything she did to me I would fill a fat volume” — and sometimes even drove her to tears. Françoise’s daughter Élisabeth, on the contrary, wrote in her memoirs that her mother loved Charlotte a lot, never refused her anything that could please her and even treated her as a daughter of her own.

Charlotte also had a hard time getting along with Éleonore, Françoise’s oldest daughter. According to Élisabeth and Maximilien’s doctor Joseph Souberbielle, she had been ”promised,” to the latter, something which Charlotte believed to be as false as later claims of Éleonore being her brother’s mistress. ”But”, she added, ”what is certain is that Madame Duplay would have strongly desired to have my brother Maximilien for a son-in-law, and that she forget neither caresses nor seductions to make him marry her daughter. Éléonore too was very ambitious to call herself the citoyenne Robespierre, and she put into effect all that could touch Maximilien’s heart.” All of this was once again to much distress for Charlotte, and, according to her, Maximilien as well, as he had no interest whatsoever in any type of marriage.

Charlotte was however on good terms with Éleonore’s two younger sisters — Victoire and, especially, Élisabeth. ”I have nothing but praise for [Élisabeth], she was not, like like her mother and older sister, stirred up against me; many times she came to wipe away my tears, when Madame Duplay’s indignities made me cry.” Élisabeth reported back that ”I was good friends with [Charlotte], and it was a pleasure to go see her often; sometimes I even pleased myself with doing her hair and her toilette. She too seemed to have much affection for me.” Charlotte often asked Françoise for permission to bring Élisabeth with her to the Convention, something which she agreed to. It was there, on April 24 1793 that Élisabeth met her future husband Philippe Lebas, who came up and asked Charlotte who Élisabeth and her family were, after which he urged the two to come to another session. They did so, bringing sweets and oranges, Élisabeth asking Charlotte if she could offer Lebas one. During yet another session, Lebas gave Charlotte and Élisabeth a lorgnette, while Charlotte showed Lebas Élisabeth’s ring, which the latter unfortunately brought with him without returning it. Charlotte consoled Élisabeth, telling her to be calm and that she would explain to her mother of how it had happened if she was to ask. But Élisabeth didn’t get her ring back until two months later, when she and Lebas also professed their love for one another. Françoise and Maurice agreed to let them marry, however, the engagement was soon complicated by Maximilien’s old collegue Armand Joseph Guffroy.