#andean region

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Combeima Canyon (2) (3) (4) by Panegyrics of Granovetter

0 notes

Text

Cuenca, Ecuador: Cuenca, officially Santa Ana de los Ríos de Cuenca, is an Ecuadorian city, head of the canton of the same name and capital of the province of Azuay, as well as its largest and most populated city. It is crossed by the Tomebamba, Tarqui, Yanuncay and Machángara rivers, in the south-central inter-Andean region of Ecuador, in the Paute river basin, at an altitude of 2,538 meters above sea level. Wikipedia

#Cuenca#Province of Azuay#inter-Andean region of Ecuador#Cuenca Canton#Ecuador#south america#south american continent

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I was in school I went to a friend's house to work on a project on a Friday afternoon. At about 6 or 6:30 when the sun was about to set her mom called us over to the livingroom. She lit two candles with my friend and then they proceeded to put the lit candles inside of a little cupboard so no one could see them. Me, a young jewish teenager asked her, my catholic friend, why they did that and she shrugged, said it was a family tradition to bring peace and prosperity, that the women of the family did it every friday evening and then hid the candles. They were very catholic, so I bit my tongue and we went back to her room to study.

This is just one of many, many, crypto jewish traditions that still exist in my hometown of Medellín, Colombia and I want to share a little bit about them with you.

Medellín is the capital city of a region called Antioquia and it is currently the second biggest city in my country. Now the weird thing about my region and my city more specifically is that it is in the middle of fucking nowhere, like we are in a valley in the middle of the andean mountains and it would take over two weeks by river, horse and river, and dunkey and mule to even get here before the invention of cars or trains.

Now Medellín was founded over 400 years ago, and families had been coming to the region for way before then, so that means that for centuries getting to my city from the sea or from the other big cities in the country was incredibly hard. This was by design, because Medellín itself was founded by about 28 families and we know for a fact that alteast half of them were crypto jews hidding from the Spanish Inquisition, and both before and the foundation more and more jewish families arrived to the region.

This is a known fact, the DNA of the people from the region has a lot of sepharadic jewish mixed in there. Early Colombian literature dating up to the 1845 would call the people of my region the Neogranadine Jews or the Colombian Jews. But because they were crypto jews the religion and most of the traditions were lost during the 400 years that have passed, now over 90% of the population is catholic and don't really know about their origins.

But some things stuck. And I want to tell you about them.

On the 7th night of December there is this pre-christmas festival called "El día de las velitas" or the little candle night that started and was unique to Antioquia. It's supposed to commemorate the candles that people had in the streets and the windows on the night Jesus was born and that helped Mary and Joseph to find their way. Do you know how this unique festival is celebrated in my city? People take to the streets to light candles, small colorful candles that they put in wooden planks or directly on the streets, it's the night that people decorate and turn on the christmas lights and it is so important and popular that we have an actual day off on the 8th of december.

Let me show you a few pictures

I don't think I need to explain this one. Even most goyim will know about Hannukah. But it is the weirdest thing when the dates coincide and we are all lighting candles together.

My dad was in the Jewish community board and we needed to rent a place to put our jewish daycare. They found this beautiful old house that had belonged to a family in colonial times but needed a little TLC. We had them remove some wooden floors because they were too old and rotting and found a huge Magen David made out stones in the center of the floor. The house also happened to have two separate kitchens and a mikveh or immersion bath in one of the rooms. These a very traditional things that colonial houses have in my region.

My grandmother converted to Judaism so I have a side from my family that is 100% from here and didn't arrive during the 20th century. I had the pleasure to meet both of my great grandparents from that side though they died when I was young. My grandma tells me that my greatgrandmother used to have one of these immersion baths in her house when she was growing up. Women were supposed to bathe in them after their periods had ended, my catholic great grandmother respected the mikveh traddition more than I ever have.

(I wish I had photos from that specific house but this happened over ten years ago, I'll show you some immersion baths from a different colonial houses that are also in my city)

Now how about we talk about traditional clothes. I'm sure most of you have heard of Ponchos, which are traditional in the Andean region, well the one from Antioquia is a little different and it's always supposed to be worn with a hat. Let's see if you can spot what I mean.

A few years ago Spain decided to grant citizenship to the descendants of the Jewish people that they had exiled in 1492. To get it you had to prove through family trees that your family had been Jewish. My city got the most ammount of passports out of everyone in the world, more than Israel. I could have applied from both my family that came from Egypt in the 20th century (we still have the keys to our house in Spain) or through my catholic side, as both of my grandmother's last names applied. I didn't but I could have.

I don't really know why I decided to finally write this post. I have so many more stories. I just think it's both incredibly sad that so much Jewish culture and people were lost but also it's a little heartwarming to see what survived even centuries down the line.

#it took me years to decide to finally write this because i didn't want to put where i live out on the internet#but fuck it#i still don't know how i feel about this#it's a bit of mourning what could've been and a bit of look a this isn't it neat#there is so much more to say about this topic but the post is too long#like how a lot of jews changed their last name to “Rojas” which spelled backwards means “lizcor” or to remember and they still forgot#or how there is a movement of reclaiming the jewish roots we have three re-emerging jewish communities in our city#one of which already converted fully and they are WAY more obvservant than my regular traditional community#crypto jews#conversos#jumblr#jewish#jews#judaism#jewish history#colombia#medellin#lationamerica#latin america#south america

650 notes

·

View notes

Text

500-year-old Snake Figure from Peru (Incan Empire), c. 1450-1532 CE: this fiber craft snake was made from cotton and camelid hair, and it has a total length of 86.4cm (about 34in)

This piece was crafted by shaping a cotton core into the basic form of a snake and then wrapping it in structural cords. Colorful threads were then used to create the surface pattern, producing a zig-zag design that covers most of the snake's body. Some of its facial features were also decorated with embroidery.

A double-braided rope is attached to the distal end of the snake's body, near the tip of its tail, and another rope is attached along the ventral side, where it forms a small loop just behind the snake's lower jaw. Similar features have been found in other serpentine figures from the same region/time period, suggesting that these objects may have been designed for a common purpose.

Very little is known about the original function and significance of these artifacts; they may have been created as decorative elements, costume elements, ceremonial props, toys, gifts, grave goods, or simply as pieces of artwork.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art argues that this figure might have been used as a prop during a particular Andean tradition:

In a ritual combat known as ayllar, snakes made of wool were used as projectiles. This effigy snake may have been worn around the neck—a powerful personal adornment of the paramount Inca and his allies—until it was needed as a weapon. The wearer would then grab the cord, swing the snake, and hurl it in the direction of the opponent. The heavy head would propel the figure forward. The simultaneous release of many would produce a scenario of “flying snakes” thrown at enemies.

The same custom is described in an account from a Spanish chronicler named Cristóbal de Albornoz, who referred to the tradition as "the game of the ayllus and the Amaru" ("El juego de los ayllus y el Amaru").

The image below depicts a very similar artifact from the same region/time period.

Why Indigenous Artifacts Should be Returned to Indigenous Communities.

Sources & More Info:

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Snake Ornament

Serpent Symbology: Representations of Snakes in Art

Journal de la Société des Américanistes: El Juego de los ayllus y el Amaru

Yale University Art Gallery: Votive Fiber Sculpture of an Anaconda

#artifacts#archaeology#inca#peru#anthropology#fiber crafts#americas#pre-columbian#andes#south america#art#snake#effigy#textiles#textile art#embroidery#history#stem stitch#serpent#amaru#mythology#andean lore#fiber art#incan empire#indigenous art#repatriation#middle ages#flying snakes tho

921 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Curiosities

The Sacred City of Caral-Supe, one of the most important and little-known cultures of the American continent, is located in the province of Barranca, Lima Region, Peru.

“It constitutes the oldest manifestation of civilization in Peru and on the American continent due to its 5,000 years of age. It is made up of 32 monumental buildings, included in a complex system of settlements that show a strong religious ideology, among which are distinguished ceremonial buildings, residential sectors for people of different social rank, a set of minor temples and production workshops. Caral led a settlement system that brought together 17 similar, although smaller, sites located in the Supe Valley.

“It expresses the complexity and development of an early socio-political and economic organization model during the Late Archaic Period (5000-3800 BP) originated independently by the Andean societies that inhabited this small fertile valley on the central Peruvian coast.”

Information:

World Heritage Sites of Peru. Culture Ministry.

501 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dream and George dancing el Sanjuanero 🇨🇴👨❤️💋👨

El Sanjuanero is a traditional dance and subgenre of Bambuco with Joropo influences. It's an important dance in colombian folklore and especially in the andean region because of the holidays in late June.

The dance represents the story of a relationship, It begins with flirting and courtship, goes through falling in love and ends with the symbol of marriage. 💚💙

Thank you Nov @suenitos for hosting the collab this was so fun seeing everyone's cultures :3

#glitch.jpg#my art#dreamwastaken#georgenotfound#dream fanart#georgenotfound fanart#dnf fanart#dreamnotfound#dteamworldwide collab#🇨🇴

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word List: Fashion History

to try to include in your poem/story (pt. 3/3)

Pelete Bite - a fabric created by the Kalabari Ijo peoples of the Niger Delta region by cutting threads out of imported cloth to create motifs

Pelisse - a woman’s long coat with long sleeves and a front opening, used throughout the 19th century; can also refer to men’s military jackets and women’s sleeved mantles

Peplos - a draped, outer garment made of a single piece of cloth that was worn by women in ancient Greece; loose-fitting and held up with pins at the shoulder, its top edge was folded over to create a flap and it was often worn belted

Pillow/Bobbin Lace - textile lace made by braiding and twisting thread on a pillow

Pinafore - a decorative, apron-like garment pinned to the front of dresses for both function and style

Poke Bonnet - a nineteenth-century women’s hat that featured a large brim which extended beyond the wearer’s face

Polonaise - a style of dress popular in the 1770s-80s, with a bodice cut all in one and often with the skirts looped up; it also came back into fashion during the 1870s

Pomander - a small metal ball filled with perfumed items worn in the 16th & 17th centuries to create a pleasant aroma

Poulaine - a shoe or boot with an extremely elongated, pointed toe, worn in the 14th and 15th centuries

Raffia Cloth - a type of textile woven from palm leaves and used for garments, bags and mats

Rebato - a large standing lace collar supported by wire, worn by both men and women in the late 16th and early 17th century

Robe à L’anglaise - the 18th-century robe à l’anglaise consisted of a fitted bodice cut in one piece with an overskirt that was often parted in front to reveal the petticoat

Robe à la Française - an elite 18th-century gown consisting of a decorative stomacher, petticoat, and two wide box pleats falling from shoulders to the floor

Robe en Chemise - a dress fashionable in the 1780s, constructed out of muslin with a straight cut gathered with a sash or drawstring

Robe Volante - a dress originating in 18th-century France which was pleated at the shoulder and hung loose down, worn over hoops

Roses / Rosettes - a decorative rose element usually found on shoes in the 17th century as fashion statement

Ruff - decorative removable pleated collar popular during the mid to late 16th and 17th century

Schenti - an ancient Egyptian wrap skirt worn by men

Shirtwaist - also known as waist; a woman’s blouse that resembles a man’s shirt

Skeleton Suit - late 18th & early 19th-century play wear for boys that consists of two pieces–a fitted jacket and trousers–that button together

Slashing - a decorative technique of cutting slits in the outer layer of a garment or accessory in order to expose the fabric underneath

Spanish Cape - an outer wrap often cut in a three-quarter circle originating from Spain

Spanish Farthingale - a skirt made with a series of hoops that widened toward the feet to create a triangular or conical silhouette, created in the late 15th century

Spencer Jacket - a short waist- or bust-length jacket worn in the late 18th and early 19th centuries

Stomacher - a decorated triangular-shaped panel that fills in the front opening of a women’s gown or bodice during the late 15th century to the late 18th century

Tablion - a rectangular panel, often ornamented with embroidery or jewels, attached to the front of a cloak; worn as a sign of status by Byzantine emperors and other important officials

Toga - the large draped garment of white, undyed cloth worn by Roman men as a sign of citizenship

Toga Picta - a type of toga worn by an elite few in Ancient Rome and the Byzantine Empire that was richly embroidered, patterned and dyed solid purple

Tricorne Hat - a 3-cornered hat with a standing brim, which was popular in 18th century

Tupu - a long pin used to secure a garment worn across the shoulders. It was typically worn by Andean women in South America

Vest/Waistcoat - a close-fitting inner garment, usually worn between jacket and shirt

Wampum - are shell beads strung together by American Indians to create images and patterns on accessories such as headbands and belts that can also be used as currency for trading

Wellington Boot - a popular and practical knee- or calf-length boot worn in the 19th century

If any of these words make their way into your next poem/story, please tag me, or leave a link in the replies. I would love to read them!

More: Fashion History ⚜ Word Lists

#word list#fashion history#writeblr#dark academia#terminology#spilled ink#writing prompt#writers on tumblr#poets on tumblr#poetry#literature#light academia#fashion#lit#studyblr#langblr#words#linguistics#history#culture#creative writing#worldbuilding#writing reference#writing resources

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo

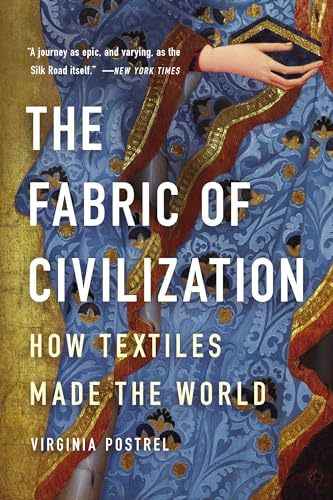

The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World

In "The Fabric of Civilization," Virginia Postrel explores how the history of textiles is akin to the story of civilization as we know it. As evidenced throughout her book, Postrel treats each chapter as a standalone story of its production and journey, all the while masterfully weaving it together to show the story of human ingenuity. While academic in nature due to its incredibly well-researched methodology, the general reader will enjoy the book's unique style and approach to world history.

In The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World, Virginia Postrel expertly demonstrates how the history of textiles is the story of human progress. Although textiles have shaped society in many ways, their central role in the development of technology and impact on socio-economics have been exceedingly overlooked. Attempting to remedy this issue, Postrel organizes her book into two distinct sections: one focusing on the different stages of textile production (fiber, thread, cloth, and dye) and the other on the consumers, traders, and future innovators of said textiles. To strengthen her argument, Postrel pulls from different primary sources across many regions and cultures, such as the works of people like entomologist Agostino Bassi and the accounts of disgruntled Assyrian merchants. However, Postrel goes beyond relying solely on books and peer-reviewed articles; she personally interviewed textile historians, scientists, businesspeople, and artisans who offered their own insight regarding the importance of textiles in the world. To help the reader envision the intricacies of textile manufacturing, the book is riddled with images that range from ancient spindle whorls and Andean textile patterns to nineteenth-century pamphlets raging over improved cotton seeds. It is quite a laborious task to explain the history of textiles, but Postrel’s way of organizing her chapters and style of writing does an excellent job of conveying her argument.

In Chapter One, Postrel illustrates the many uses of fibers and how their multipurpose functionality served its role in world economies. From the domestication of cotton in the Americas to sericulture in ancient China, such fibers left an indelible mark on trade and technology. Chapter Two looks at the use of thread's connection with social and gender roles as Postrel argues that dismissing fabric as feminine domesticity ignores its integral role in the social innovations that products like clothing and sails provided. Chapter Three connects mathematics with weaving through handwoven textiles by Andean artisans and in the notations written down in Marx Ziegler’s manual, The Weaver’s Art and Tie-Up Book (1677). Chapter Four explains how dyes not only contributed to the distinction between social classes, such as the use of Tyrian purple by Roman emperors but also the ingenuity of humans to ascribe meaning and beauty to a variety of colors. Furthermore, the increasing and competitive trading of dyes in the 16th and 17th centuries would eventually contribute to the discovery of synthetic dyes.

Textile traders and consumers also helped to foster cultural exchanges. Postrel then highlights how traders often also served as innovators. The implementation of the Fibonacci sequence in European trading not only helped traders with bookkeeping but also gave a new perspective to the practicality of learning math by helping traders understand profits and calculate prices. Readers explore in Chapter Six how the Mongol Empire expanded across many different lands for their desire for valuable woven textiles. Under the Pax Mongolica, the textile trade flourished as the Mongols protected the Silk Road, resulting in cross-cultural and technological exchange between Europe and Asia. Lastly, in Chapter Seven, Postrel introduces synthetic polymers like nylon and polyester, where the efforts made by scientists like Wallace Carothers, Rex Whinfield, and James Dickson have revolutionized the use of textiles. Companies like Under Armour use polyester to create water-repellent clothing. Despite synthetic polymers currently being used innovatively, many still seek to look into the future of textiles. As Postrel explains, imagine your pockets can charge your phone or your hat could give you directions. The future of textiles is incredibly exciting.

As an avid writer of socio-economics, Postrel expertly showcases her knowledge of the subject. Postrel’s previous books, such as The Future and its Enemies (1998) and The Power of Glamour: Longing and the Art of Visual Persuasion (2013), cover the interconnectedness between culture, technology, and the economy. Postrel has also worked as a columnist for several news sites, is the contributing editor for the magazine Works in Progress, and was a visiting fellow at the Smith Institute for Political Economy and Philosophy at Chapman University. This book is a wonderful intellectual contribution that feels like a documentary series, perfectly threading the reader through cultures and regions like a needle through fabric.

Continue reading...

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the border of Peru and Bolivia, the Waru Waru—an indigenous Quechua word that means ridge—are once again protecting potato and quinoa crops as they did in the region 2,000 years ago. "It is an agricultural system that lets us face climate change, which has changed the seasons of the year. It is very beneficial in times of drought and frost," farmer Cesar Cutipa, 42, told AFP. Puno lies on Lake Titicaca about 3,812 meters (12,507 feet) above sea level. Farmers have made six Waru Waru nearby in flood-prone fields. Furrows form a rectangular platform, where planting is done. Surrounded by water, the planting beds are up to 100 meters long, between four and 10 meters wide and one meter high. The water around the plants creates a microclimate, absorbing heat from the sun during the day and radiating it back at night to ward off frost in sub-zero temperatures. "The Waru Waru cannot flood during the rainy season because they have an intelligent drainage system that reaches the river. They have many advantages," agronomist Gaston Quispe told AFP. In 2023, when Puno suffered one of the largest periods of drought in almost six decades, Waru Waru helped farmers cope with lack of water and avoid food shortages. The area is home to mostly indigenous farming communities, mostly Quechua in Peru—and up the Andes—and both Quechua and Aymara in Bolivia. "We are able to live here peacefully because we have our potatoes, our quinoa and barley. We can be in peace without going to the city," said 22-year-old farmer Valeria Nahua.

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rocks recently exposed to the sky after being covered with prehistoric ice show that tropical glaciers have shrunk to their smallest size in more than 11,700 years, revealing the tropics have already warmed past limits last seen earlier in the Holocene age, researchers from Boston College report in the journal Science. Scientists have predicted glaciers would melt, or retreat, as temperatures warm in the tropics—those regions bordering the Earth's equator. But the study's analysis of rock samples adjacent to four glaciers in the Andes Mountains shows that glacial retreat has happened far faster and already passed an alarming cross-epoch benchmark, said Boston College Associate Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences Jeremy Shakun

Continue Reading.

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I wonder if you have seen difference between brujeria in certain regions and countries, like would Mexican brujeria be different then Salvadoran brujeria.

Que Dios de bendiga

The different paths of Brujeria

There are many distinct branches of Brujeria. In my opinion, I simply see the term as the Spanish word for "witchcraft". Therefore, there are many types of it. I've coined the term 'Brujeria de frontera' for my practice -- I am a border witch. I live in a place where the cultures of the southwestern USA and Mexico blend into a unique branch of Brujeria on its own. It is not entirely the same as Mexican Brujeria, but it is also not entirely "American". There are distinctions between what I practice than that of my Bruja friends from Mexico.

Sure, I do believe there is a general theme to all Brujeria, that being regaining our own power; regaining control over our spirituality. However, I do think each unique region of Central and South America provides a different backdrop for their spirituality. For example, there may be plants that grow better in Chile than in Mexico, so that plant is more likely to be used in Chilean Brujeria than in Mexican Brujeria. A good analogy would be that of the different branches of Voodoo. There are clear differences from Haitian Vodou compared to Louisiana Voodoo. These differences can come from a variety of sources, such as the different colonial powers, the different tools and ingredients available to practitioners, or the different origins of the enslaved peoples who's religion combined to form Voodoo. Thus, they are distinct branches of a religion.

Another example could be that of the different Christian denominations, such as the differences between Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, however I will not delve into too much detail here as there are many sources out there for information on this.

So, for example, the Maya people practiced a religion that was hidden and intertwined into Folk Catholicism and Brujeria due to the Spanish colonization of Mexico, creating a unique religion that is different than say, that of the Andean peoples. Another thing to note is that branches of Brujeria often share more common threads, such as Spanish colonizers, the Spanish language, and Catholicism. These lead to them to develop similarities, such as the use of saints as a concealment for praying to the original pantheon. So, while different cultures blend differently with Catholicism, many of them used Catholicism as a way to keep their spirituality in a way that the colonizers approved of.

While my Abuelita may do a limpia different than my Puerto Rican friend's, they still share many common threads that unite us as practitioners of the folk religions, and of Brujeria. This is my stance on the idea of different branches of Brujeria and how distinct or connected they all really are.

#brujeria#new mexico#witchblr#witchcraft#folk magic#folklore#green witch#grimoire#polytheist#witchcore#voodoo#black spirituality#spirits#esotericism#closed practices#spiritual cleansing#spiritualgrowth#spirituality#reclaiming spirituality#brujería#magic#witch#witches#limpiar#energía limpia

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

LLama, Libertador, O'Higgins Region, Chile: The llama is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a meat & pack animal by Andean cultures since the pre-Columbian era. Llamas are social animals and live with others as a herd...The Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins Region, often shortened to O'Higgins Region, is one of Chile's 16 first order administrative divisions. Wikipedia

#LLama#Libertador Bernardo O'Higgins Region#Chile#Pichilemu#O'Higgins Region#south america#south american continent

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

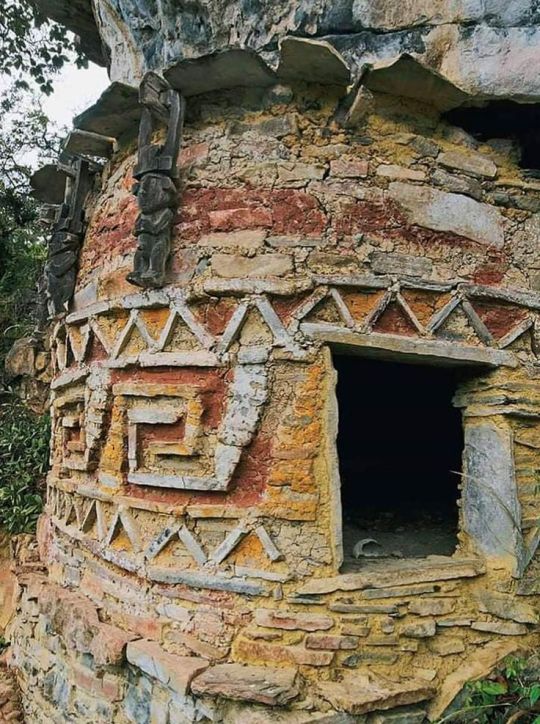

☀ Chachapoyas culture (Peru)

-The Chachapoyas, also called the "Warriors of the Clouds", was a culture of the Andes living in the cloud forests of the southern part of the Department of Amazonas of present-day Peru.

☀ Gran Pajaten

- Gran Pajatén is an archaeological site located in the Andean cloud forests of Peru, on the border of the La Libertad region and the San Martín region, between the Marañon and Huallaga rivers

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Amaru or Katari (Aymara) a majestic twin headed serpent like creature depicted across Andean Civilizations, Originally said to have been capable of transcending spiritual and otherworldly boundaries for the world was Separated into the realm of the gods and birds, Hanan Pacha or the world above; the world where mankind resides the Kay Pacha or world of the present; and finally the underground realm of the dead or the Ukhu Pacha, the world below. where its said the Amaru would move the world by its shear size and force of will, creating many of the mountainous outcroppings seen in the region, or creating devastating earthquakes. This would gain the great beasts the ire of the of gods and leading to cataclysmic and deadly conflict's the great serpents deaths would create vast mountain ranges.

The revered creatures lore and depictions would be altered to suit changing society's and foreign colonial influence trying and suppress Indigenous beliefs and values, some Incan rulers even tried to harness this power by adopting name for themselves to try and cement their political gain . Eventually this lead to depictions that suited a more chimeric monstrous for, reflecting its old world counter parts, adopting traits from many other creature, to now be defeated by mere humans.

some cultures preserved and even re incorporated these new aspects with the old, creating hybrid depictions and gaining very broad symbolism such as the economy of water, and tending to the land, and even more cosmological aspects of space or wisdom, or simple fundamentals of the creativity of the peoples, sometimes these new Amaru could be seen clashing with each other. representing the more destructive side of nature, devastating the peoples and the lands, too only be stopped by the storms themselves or through the intervention of their old rivals, now taking a new cast of god's. once again through death creating the Mantaro valley returning to their earthly roots.

#amaru#dragon#serpent#creaturedesign#digital art#monster#inca empire#Andean civilization#mythology#south american#chimera#illustration

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moche Earthenware Stirrup-spouted Cat Jugs

The Moche civilization, also known as Early Chimu or Mochica, flourished from approximately 100 to 800 CE in the Northern coastal regions of Peru.

Andean Mountain Cat (Leopardus jacobita)

Pampas cat (Leopardus colocola)

Also known as the Peruvian desert cat, this small feline is native to South America and can be found in Peru. The Peruvian pampas cat lives on high plateaus and can be up to 5000 meters above sea level.

#peruvian#moche#early chimu#mochica#precolumbian#prehispanic#ceramics#earthenware#cats#wildcats#wildlife

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

T'anta wawa ("bread baby", from Aymara and Quechua t'anta "bread" and wawa "child, baby") is a type of sweet roll shaped and decorated in the form of a small child or infant. They are generally made of wheat and sometimes contain a sweet filling. They are made and eaten as part of ancestral rites in Andean regions of Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru, the south of Colombia, and the north of Argentina, mainly on All Souls' Day, but also as part of agricultural festivals, carnivals, and Christmas. T'anta wawa are consumed on November 2 all over the Andean region. They are eaten with colada morada. They are made by families and exchanged among groups of family and friends and given to godchildren. In rural cemeteries and indigenous communities, such as Tungurahua Province, they are used as offerings as part of a ceremony of encounter with one's ancestors.

src.: Radio San Gabriel, "Instituto Radiofonico de Promoción Aymara" (IRPA) 1993, Republicado por Instituto de las Lenguas y Literaturas Andinas-Amazónicas (ILLLA-A) 2011, Transcripción del Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, P. Ludovico Bertonio 1612 (Spanish-Aymara-Aymara-Spanish dictionary), Teofilo Laime Ajacopa (2007). Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha [Quechua-Spanish dictionary]. La Paz, Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua [Quechua-Spanish dictionary]. Cusco: Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco. 2005, Wikipedia

10 notes

·

View notes