#and strongly references to patriarchy etc.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I don't know but I am so going to get a bad grade on tomorrow's literature test. I'm looking at previous tests and their "example answers" and I'm like .... what.

RIP.

#personal#analyze this and analyze that#there was an excerpt of some man's book where he's describing stuff about farming and growing fruit and so on#and how some fruits go rotten and people go hungry#and in the example answer you were supposed to highlight how this text was in fact critical towards capitalism#and strongly references to patriarchy etc.#whereas i was looking at that text and thinking '... this guy's just talking about growing fruit lmao'#like. what do you guys smoke to get all deep and analytical like that#cause i'm gonna need that same stuff for tomorrow's exam asap#i don't even have the energy to read analysis posts on tumblr#not to mention write a 4000 character novel/poetry analysis#about stuff that i don't even see there#jeez#i'm so fucked

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

friendlinghood: a proposal

skip to "terminology" if you don't want the long explanation

QPRs are really difficult to talk about because of the way the modern queer community has kinda framed it as like "dating but without romantic attraction"

when that's not entirely true

I mean, you COULD say that's a kind of QPR but it'd be a mistake to frame all of it that way. this is in large part to internet misinformation and shit as well as amatonormativity from which a lot of relationship discourse is framed against

queerplatonicism, from my pov refers to what is essentially the natural byproduct of queer and neurodivergent people having close friends

the queer community has been aware for a while that its members would have close friendships that in some way violated traditional social norms for behavior outside romantic relationships or family, etc.

when you sit outside the neurotypical and patriarchal norm, the conventional social understanding of what relationships are kinda breaks down for you

you display levels of closeness and intimacy and affection that are "inappropriate" for neurotypical and patriarchal society. in most cases they're not formal relationships, but natural evolutions of friendships between queer and neurodivergent folks

cishet people actually do have variants on this like the concept of "blood brothers" where two men who love each other basically make a pact to always have each other's backs and be their support and they do the whole movie thing where they mix blood to bind them together (it's a very cinematic thing, but the point is it exists in the popular consciousness)

"romance" and "friendship" each refer to a set of social norms and expectations. there's like a whole narrative constructed around those concepts and people internalize and have their own versions of them

a lot of people probably have friends they want to fuck or kiss or cuddle or declare their undying affection for but it'd just be "weird" within the social boundaries of acceptability and so people pigeonhole their relationships into either friend or romantic partner.

queerplatonicism (from my pov) is essentially accepting or practicing relationships which are neither platonic or romantic or even strictly familial. many queer people have them with other queer people they're close to. if you know queer folks then you probably know what I'm talking about - the friends they have that they're not dating but seem intensely attached and close to. they usually have weird names for each other that go beyond friendship like they'll jokingly call each other wives and husbands and siblings and partners... but it doesn't feel quite entirely joking. they'll express a lot of physical affection in the casual way you might typically ascribe to romantic partners. they'll prioritize time with those people as much as any romantic partner they may have etc.

straight and cis people and neurotypical people obviously experience them to some extent, it's just that patriarchy was built around cishet neurotypicals in particular, so it tends to cling to their mindsets more strongly, and once you're already outside of the "bounds of normalcy" by being queer, ND, etc. then it's a lot easier to feel like it's okay for you to be in relationships that aren't "normal".

because like the idea of loving someone with your entire fucking being... it's so tied up in these cultural ideas on how to behave about those feelings and it never made sense to me, because if you just let yourself feel those emotions you start to realize there are people in your life that maybe you love so much more than friends. but "more than friends" is so washed up in romance that you force those feelings down and think "this is fine, I'm happy with being just friends, what else can we be?"

maybe I don't want to have sex or hold hands on a ferris wheel or get. married or kiss or any of that. maybe I just want to exist in the same room as that person know that that person is in my life and know that person cares about me just as much as I do them.

terminology

I've started to use the term "friendling" in my day to day life, now. the term is a portmanteau of "friend" and "sibling" and "loveling" (the english cognate of the German word "lieblings" which can mean "favorite", but is also a term of endearment).

to me, it's probably the most accurate way to describe the Everything All At Once feelings that are simultaneously your weird friends that are your found family and also "romantic" but twisted beyond recognition where the term stops meaning anything.

I'm just throwing this word and explanation out there for anyone who feels like me and wants to use it too. not exclusive to queer people or neurodivergence or anything, I just think it's often easier to be cognisant of those feelings when you are queer and neurodivergent.

that being said, I do NOT want this to be folded into another "attraction label". this is, as far as I can tell, not a unique form of attraction but quite literally the opposite. it's an abstraction of the core impulses of attraction that ALL humans experience without the labels or social structures built around it. I do not want the language that I've spent so long trying to find for my experiences losing all of its value and being reapporpriated into the amatonormative, allonormative, and cisheteropatriarchal framework.

"friendlinghood" - is what I see as an attribute of relationships and the extent to which they deviate from socially conventional definitions of a relationship.

"friendlingship" - used grammatically like friendship. referring to any complex relationship acategorically.

"friendling" - used grammatically similar to friend. referring to those involved in any complex relationship acategorically.

all of this shit is nebulous and doesn't really mean anything beyond what meaning you choose to give it. I think any relationship can have some amount of friendlinghood and I don't think there's a clear line between friendlingship and friendship or romance or family, because it's not a type of relationship in the first place. it's just silly words I made that helped me.

language and labels

so the biggest problem with terminology like this is you can end up creating labels. my point was to create personal terms for myself and my relationships because that's what helped me personally process my own feelings.

that's not to say everyone needs or benefits from them. you can just vibe and do whatever you want and many people are happy with that.

I don't think words like this being codified and standardized really helps anyone. it's unavoidable that we as humans like articulating feelings, but the entire point of my interactions with friendlinghood is about certain things defying labels and language. language in this sense is just a tool, it's a hammer for a nail. it's not embodying the concept itself, it's just useful shorthand.

I will still freely refer to friendlings as close friends, best friends, found family, and other words. as long as I know the intention behind it is all that matters. I just needed that initial bit of language to articulate the feelings before the other words felt right to me.

#romance#relationships#healthy relationships#friendship#neurodivergence#actually neurodivergent#actually autistic#lgbtqplus#lgbtq community#lgbtqia#aromantic#aromanticism#acespec#aspec pride#asexuality#aroace#queerplatonic#queerplatonic relationships#queer

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know I feel similarly. I think a big problem is that there’s a big disparity between how much people know about and like Artemis compared to Apollo. It’s very noticeable to me (as an Artemis enthusiast) when people reference Apollo’s myths, domains, and traits but next to nothing of Artemis’s when it’s supposed to be about both of them.

A good portion of people base their personalities off of how they were in Percy Jackson. Inside and Outside the Percy Jackson fandom. So the base dynamic is already Artemis-serious, smart, tough—-Apollo—-laidback, goofy, playful. (Riordan loved this goofy guy-tough girl dynamic.). Like you said, it’s questionable if this fits their mythological characters. And may be indicative of modern gender stereotypes more than anything. (Why isn’t Apollo as the god of knowledge “the smart one”?)

The lack of knowledge about Artemis means that people fill in the blanks in their own ways. Generally there are two ways this goes. Badass woman—and/or opposite of Apollo.

Badass woman: everyone has their own idea of what a badass women looks like. So this type of Artemis comes in lots of variations. Maybe she’s violent, curses like a sailor, stoic, smashes the patriarchy, snarky, rude, etc etc.

Opposite of Apollo: Artemis’s personality is the exact opposite of Apollo’s. However he acts, she acts the reverse. Whatever Apollo likes/is good at Artemis can’t do or dislikes.

Both are flawed in that they don’t factor Artemis’s own mythology and history into her personality. Artemis is more complex than a 2 dimensional stereotype or a mirror of her brother. Artemis and Apollo actually had quite a lot in common. I wonder if people realize that letting them get along well and be in sync is an option.

Because this is getting long I’ll wrap up by saying I strongly agree that Artemis should be allowed to be silly and to have different sides to her. In the myths Artemis cries, she picks flowers, she sings and dances with the nymphs. She’s a daddy’s girl. She’s fickle. She has a short temper. She shows affection to her friends. I wish people knew about this Artemis.

Every time I read a fanfic about Artemis and Apollo, I'm just. Left disappointed. Bc no one thinks of them the way I do and it's sad

#apollo#artemis#greek mythology#greek gods#rrverse#riordanverse#pjo apollo#pjo Artemis#I didn’t have time to get into how Artemis sometimes gets treated like Apollo’s accessory#Being smart seems like a good thing but sometimes with fandom it just means that they’re the straight man for the interesting characters to#bounce their jokes and hijinks off of#don’t get me started on the toa fandom’s need to make Apollo better at everything and more liked than Artemis

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

re: Éowyn, I think the OTHER problem is that patriarchy is inconsistent in Tolkien’s universe.

Númenor seems to have developed it as an institutional force independently (LaCE’s whole section about Noldorin gender roles indicates that even if the author is a bit sexist the elves don’t seem to be, even down to an absence of a requirement that marriage be heterosexual*, and Haleth and Andreth respond to some gendered pressures but they don’t seem to be systemic) but challenges it through the legalization of absolute primogeniture. Despite this, Gondor and Rohan have their own versions of patriarchal norms, in contrast to Harad and potentially to Umbar. The Shire is written as a land of benevolent sexism, and yet Merry never questions Éowyn’s capacity to murder things with a sword when he realizes he’s been riding with a woman. So we’re left with this nebulous thing that obviously exists and impacts the life of one of the most significant female characters in the text, but that also clearly exists in a way that’s different from our own modern conceptions of patriarchy as all-encompassing and global even as the author isn’t thinking too hard. I wonder if a more feminist LotR written with, say, input from Joy Davidman, would have featured the non-Gondorian Aragorn calling out the patriarchy, but that’s simply because Tolkien tends to do those sorts of things in response to criticism (see Gimli).

* LaCE-compliant elvish marriage being queer-friendly is sort of my personal soapbox, I apologize

ok, so ill admit we're starting to edge out of my area of (if you can call it that) expertise since ive done the most research on the real-world mythological/literary connections within the Men (celts and anglo-saxons specifically, lord above ive read so many eye-splitting middle english poems in the last few months), but i would love to hear more about the stuff with gimli, which i havent heard about before!

also for the sake of transparency im about 2/3 of the way through the silmarillion until my local library's hold comes in so im a bit new here

so something ive done a lot of reading/writing on myself is that patriarchy in rohan/gondor is very closely tied to war and "warrior culture," i.e. this concept that glory via violence should be celebrated above all else and the association of this idea with masculinity. this is more prevalent in rohan than gondor, but tolkien writes that that the presence of a budding warrior culture in gondor is some sort of "fall" from a more peaceful (and implicitly wiser) culture of the past, which very well could be a reference to a more Elvish, numenorean culture (if im reading your ask correctly in assuming that numenor's culture isnt quite as patriarchal as we see in later ages)

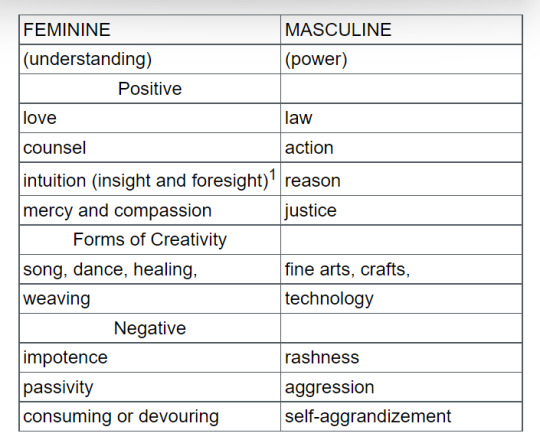

so the thing that gets complicated is that these ideals of peace, wisdom, the arts, intellectualism, etc over war are strongly gendered. in The Feminine Principle in Tolkien, Menalie Rawls (who also saved my ass on that paper god bless her) suggests that a lot of the aforementioned traits associated with this "better" (i.e. aligning more with tolkien's internal moral compass for the book) numenorean-refugee culture are strongly in the feminine category, while the warrior culture stuff sits in the masculine category

so that leads to a bit of a weird point. i think a lot of patriarchy as we see it in lotr is related to this idea of the descendants of numenor falling away from their roots and becoming more hypermasculine (the thesis of Rawls's paper is essentially that tolkien's heroes are either expected to have an internal balance of gendered traits or an external one where they balance their gender expression with strong opposing forces to become their most heroic self, i.e. legolas and gimli, eowyn and faramir, varda and manwe, beren and luthien, etc) as opposed to their more balanced, and therefore, in the eyes of the book, "better" past. essentially, like the warrior-worship, patriarchy seems to be an adverse effect that centuries of war can have on a culture

the weird part of it is that i dont know if the whole fall from a golden age thing was supposed to include patriarchy as a symptom of societal decline or just had it coincidentally because tolkien personally associated femininity with peace. it feels like a bit of a chicken or the egg situation honestly

but, like most of tolkien scholarship, this all completely falls to pieces when you try to apply it to the hobbits. i would hazard a guess that the hobbits do a lot of weird shit that doesnt click with the rest of the world (i.e. golf, wristwatches, a mailman) because they're supposed to be the closest thing tolkien has to a normal english human reader in his worlds, so they probably dont have any views/cultural norms outside what someone in the rural england of his childhood would have. best i've got is a reason, but not an explanation

in certain pockets of the world, i think the culture of patriarchy is pretty well justified. however, i agree that there are some major inconsistencies. the hobbits, as per usual, break any theory you try to apply universally across the text. the crowning of aragorn, which is meant to represent gondor's rebuilding to its former glory, has very little to do with how women are treated (which does make me lean more towards the "patriarchy just came along with tolkien liking peace and not warrior culture while also gendering those two concepts" theory now that i think of it). if anything, femininity is treated better after aragorn's crowning (i.e. focus on healing, very gender-balanced king, rewarding small heroes, marrying an Elf, rewarding faramir, tree blooming again, so much celtic symbolism stuff i dont have time to get into but they were considered effeminate as well, etc). but that's how the concept of femininity is treated which is. yknow. different than actual living breathing women

so point is, 1) there's some insight onto why gender concepts look different among different cultures, especially with Men 2) hobbits confuse me

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

Wait are radfems bad? ( I guess does this mean in reference to terfs or just all radical feminists ? ) Idk personally I'm pretty proud to consider myself a radical feminist and like actively working to dismantle patriarchy systems etc but if the word has other connotations I guess I should find a new word to identify with vs radical feminist...? Like def not supporting the trans exclusionary part but the bra burning/smashing gender roles radfem part seems good idk what are the kids out there saying these days?

i don't want to misspeak so, as anticlimactic an answer as it is, i strongly encourage you to do your own research. from what i understand radfems and terfs often run in the same circles and i find them tough to distinguish, but a lot of radfem ideas are transphobic and can even intersect into racism (who gets to be perceived as feminine/a woman in our society?) . you can be a radical feminist in the plainest no-subtext sense of the two words together, but the people who use the term Radical Feminist or radfem are people you don't want to be associating with.

#ask#anon#whats a personal tag anyways#smarter ppl feel free to correct me#or add on#i can only speak as an afab american here

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demonising Femininity

🤍 Disclaimer- In this article, we are mostly talking about femininity in the aspect of make-up, fashion, etc. Stereotypically feminine and masculine things are a social construct, and it is okay for anyone of any gender to engage in their preferred form of expression.

“You run like a girl.”

“Man up.”

These two sentences both talk about behaving like a certain gender, yet one is uplifting, while the other is an insult. It’s not hard to guess which is which.

We know that misogyny exists, and being a woman in itself comes with a lot of challenges. But it’s even worse when one is traditionally feminine.

So, what is femininity?

The concept of femininity varies across cultures, but it is generally the various characteristics and traits that are attributed to women. However, as these are personality traits, they can be exhibited by anybody regardless of gender. According to popular belief, it includes sensitivity, tenderness, kindness, passiveness, etc. In the modern world, it is also equated with the combination of wearing make-up, being concerned about their physical appearance, and ambition. But there isn’t a real definition of femininity as it is pretty much a spectrum encompassing certain traits. These certain personality traits and characteristics got gendered because society had a specific role for each gender, and they evolved these traits to better adapt to those particular roles. While both masculine and feminine traits can be found in everyone in various combinations, society expects men to show more masculinity, and women to show more femininity.

When and how did it get demonised?

Misogyny can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece, with the myth of Pandora’s box, where Pandora opened the box and unleashed misery upon mankind. Therefore the blame for all of man’s problems was placed upon the shoulders of a woman, and it all went downhill from there. As the original colonizers, the Greek spread this tale into the places they conquered, and misogyny took root in all the cultures around. This idea of women being inferior was also propagated by the tale of Adam and Eve in the Old Testament, where Eve made Adam eat the forbidden apple, which led to the downfall of man.

In the 1950s in the USA, women who had taken up civilian jobs during world war 2, were now expected to go back to being housewives, or taking up more ‘feminine’ jobs which would ultimately pay less. Due to this, in the second wave of feminism that started in the early 1960s, women rioted and started dressing and acting more ‘masculine’ in the hopes of being taken seriously by their male counterparts, and getting the jobs they needed. This meant that they denounced make-up and high heels and other such ‘feminine’ things.

So presenting as more masculine in that era was unfortunately required for women to empower themselves. But why do we still look down on those who present themselves in a feminine fashion today? We see it everyday; women who wear more make-up are considered shallow, women who like to dress in pink and have blonde hair are considered to be stupid and childish, and those who conform to this kind of femininity and are ambitious are chalked up to be mean and selfish, especially in the media.

In common teenage coming-of-age movies, and young adult fiction, the antagonist is generally a stereotypically feminine and preppy girl, while the protagonist is more of a tomboy and an outcast. The antagonist is made to be a villain with only their own motives in mind, with no other personality traits whatsoever. Though this does not embody what femininity means, it still depicts the appearance of hyper femininity as something that should be shunned. This is common even in movies targeted towards other audiences, such as Dreamworks' 'Shark Tale', where one female fish is strongly ambitious, while being concerned about her physical appearance. However, she is given the role of the villain, while the female love interest is, to be frank, bland and more passive, with her whole personality being just the love interest.

This kind of stereotyping women into two very strict boxes damages us more than we think. People knowingly or unknowingly absorb a lot of concepts from the media, and when we are presented with the idea that being ambitious and rocking a pink outfit = bad, while being passive and dressing down makes them more interesting, we apply this in our day to day life as well. But this narrative is absolutely wrong, because women cannot be pushed into such strong stereotypes. People are complex beings, and with each person's personality being so drastically different, it goes without saying that the same applies to women.

Studies have found that women who wear more make-up in their workplace are less likely to be given a promotion, solely because of their make-up. It is commonly viewed that women who wear heavy make-up are considered to be less competent than the other female workers. But this is a misconception, as the productivity of a person is in no way related to the amount of make-up they wear, or the way they choose to dress.

Another way this is expressed is that parents allow their daughters to play with ‘boy’s’ toys and games, but the same is not applicable the other way around. Sons are rarely given dolls and Barbies to play with, for the reason that it will somehow make them less masculine. What scares people so much about femininity?

Demonising femininity affects the mentality of almost everyone. It pits women against women, and pushes back the feminism movement as well. In the end, only the patriarchy benefits from this. Femininity being labelled as something that is evil has given rise to the ‘not like other girls’ and ‘pick-me girls’ trope.

The ‘not like other girls’ trope is basically when a girl, typically a pre-teen or teenager, believes that she is different from other girls because she is not into mainstream pop music, or doesn’t wear make-up and dresses.

Okay, she believes that she’s different. What’s wrong with that?

The problem is that when this phrase is used, it’s usually in the context that the girl being referred to is better than other girls just because she doesn’t wear make-up. The phrase puts down the entire gender, while trying to compliment one girl in a back-handed way. Dressing in a different way isn’t a reason to put a person on a pedestal, and it builds up a superiority complex for something that is pretty much inane. The phrase doesn’t even bring into consideration the personality of the girl in question as well as the personalities of the other girls.

This also results in internalised misogyny, since the girl believes she is better than other girls because she is being as masculine as possible, hence leading to the conclusion that being a girl in itself is bad. Internalised sexism, according to Wikipedia, is when an individual enacts sexist actions and attitudes towards themselves and people of their own sex. They further propagate the ideals and behaviour imposed upon them by their oppressors. This causes a bigger divide within women, as they subconsciously put down other women who do not conform to the patriarchy, and they tend to believe gender biases in favour of men.

This kind of mentality is hard to shake out, and it is damaging in both the short and the long run. Embracing your ‘feminine’ side is something that’s not only fun to do, but it also makes us human. Being feminine is not something to be ashamed of, or something to be demonized. The whole idea plays into the patriarchy. The ideology of ‘live and let live’ is very important in this aspect. We shouldn’t put down women just because of the way they dress. Many aspects of femininity help make us better people, and that is something we should celebrate.

We should no longer have to be apologetic or embarrassed for our femininity. We deserve to be respected for all our femaleness.

#we r back!!#blog#blogging#personal blog#bloggers#feminine#feminism#misogyny#women deserve to get good rep whilst being feminine#the media rep for women and poc and lgbtqia+ sucks man#feminist#the media needs to stop demonising femininity esp ultra femininity

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

YMMV but Lily was a stand in for Rowling. It's why the relationship with James is uncomfortable to read.

(I hope I guessed the meaning of stand in well because I am not totally sure)

In reference to this post about Gryffindor's (and JKR's) belief in their moral superiority.

Ah, yes op. I do think JKR wrote Lily as this, in her eyes, symbol of perfection for Harry, this symbol of goodness and kindness. I'm sure she saw her behaviour toward Severus as completely okay and positive, I'm sure she never questioned her writing of this apparently flawless character even during The Prince's Tale. But the fact she wrote Lily as flawless (more of a symbol than a character, honestly) doesn't mean she is actually flawless and we now know how problematic JKR's work can be.

I think, and this is a personal opinion, that JKR wrote Lily according to her standards of what a good person is like. Standards she also applies to herself, because she, as an author, and Lily, as her stand in character, have many similarities in the way they view the world and behave toward others. I am of course not comparing a real person and fictional character, but trying to show how one can influence the writing of a character - and what this person thinks of this character, which can be reflected through the narrative and main character's POV. Then, by extension, all of this strongly influences our own views on the character as readers, especially when reading the books for the first time. Some things that are disturbing to us and not understood by Rowling:

Strong belief in your own moral integrity: JKR seems to use her books as a weapon against those who point out her narrow-mindness, constantly reminding us she wrote them as a message of love and acceptance, "including" diversity in her world. She never questions her own behavior. She wrote Lily as morally flawless also because she is a Gryffindor and muggle-born: Lily, if you follow her narrative, is in her right to condemn and be critical of Severus' friends and choices, and to highlight her Gryffindor classmates moral superiority (ie they don't use dark magic) to justify the fact she grants herself the right to judge her friend and condemn his friends without addressing bullying. Because she knows better, and is moraly superior. Just as the narrative never really adressed the fact bullying by Gryffondors on a Slytherin isn't justified because they are "on the good side". JKR considers herself to be part of the Good People™, for many reasons, thus doesn't see any problem is writing blog posts explaining to some people why they are a threat to her own feminist fight or how they should behave. Of course I make NO comparison between her transphobia and a fictional character's behaviour; I'm just trying to show there is a similar pattern of behaviour which is, if I have to sum it up: I have moral integrity because [...] ➡️ So this moral superiority cannot be questioned ➡️ So this gives me the right to judge you/tell you how to behave without sweeping my own backyard.

Quick to condemn, unable to understand: This moral superiority (let's face it, Gryffindor are always portrayed as moraly superior in the books which nearly always justifies for discrimination against Slytherin) JKR thinks she has for reasons said above has for consequence the fact she gives herself the right to point out people's supposed flaws and "dangerous" behaviour without ever giving them time to explain, or listening to them. She sees what she wants to see, and so does Lily as she wrote her: the narrative makes of the fact she never gives Snape the opportunity to explain himself a normal thing, because we already know he is in the wrong; she already knows it and decided it, so why would she even ask?

Belief in your own right to judge and change people: for all the reasons I wrote above. You can question behaviours, you can point out flaws and issues: but you, as a person, cannot grand yourself the right to say "I know better than you do because this, this and this, so please change for me or I'll stop being kind to you." To JKR, this is perfectly acceptable behaviour (for example, "she knows and love trans people" but to the condition they remain silent and do not threaten her fragile views on feminism. If they do, she'll consider them a threat.) She writes Lily with a similar kind of behaviour regarding Slytherins: "without trying to understand who you are and why you are the person I see standing in front of me, without educating myself on your motives or asking for you pov, I ask you to change to match my own standards, no matter what it costs you."

Use of minorities, etc to serve personal aims and display your moral integrity: We have a whole history of JKR using sexual orientations or racial minorities to promote her work's open-mindness without ever giving them a voice or listening to them, trying to understand them. She writes Lily as a character who has such a good heart she is friends with Slytherin, dark arts affiliated Severus Snape and who knows it: "My friends (moraly superior Gryffindors) don't even know why I still hang out with you". ie "you should be grateful and their opinions have more values than yours to me." She points out her own benevolence at still accepting Severus as a friend, but never tries to understand Severus' own bravery and struggle at still being friend with her while having to survive in Slytherin house as a half blood (which was obviously more difficult). While reading this particular extract from the text, I cannot unsee the fact she (or JK) seems to think she does Severus a favor for being his friend (in context it's perhaps understandable), but it's very telling JKR would write this - we get the message as readers. The conclusion being, Lily had to be this moraly perfect girl as she had a Slytherin friend. I cannot say it's not implied by the narrative or it's not what JKR thought (she has lesbian and trans friends, so what she says cannot be discriminating/are justified by her supposed openness). Another disturbing and wrong way of thinking.

Belief that your belonging to one oppressed minority prevents you from oppressing others: JKR uses her identity as a woman in a patriarcal society, her statues as a woman who suffered from this patriarchy, to justify her transphobia and point out the fact she, as part of a group which is oppressed, do not oppress others (her blog post on "Why I'm not transphobic" is very telling). My feelings when I read Lily's character (but this may be interpretations from my part) is that her statues as muggle-born also automatically grants her moral integrity or at least a moral compass (narrative-wise) to be judgemental over Severus' relations and to decide whether or not the Marauder's actions toward him were serious: there is a kind of disturbing hierarchy that is created with Slytherin using dark arts and having prejudices against muggle borns (according to her) vs the Marauders and their pranks (not serious at all especially in comparison for her, and anyways they are Gryffindors). As if the fact she is the victim of oppressors means she doesn't have responsibilities or all she does is somehow justified or cannot mean ill (for example, turning her back on Severus while he is being sexually assaulted after he insulted her. She had a duty to perform as a prefect, which she wasn't even doing well before he said anything). The problem isn't her, she has reasons to act the way she does and flaws like all human beings. The problem is that the narrative (thus JKR) sides with her and never have us readers question her behaviour as well. It matches her inner belief that some people's moral integrity cannot be questioned for certain reasons. We are never offered another pov, we are never shown another perspective (of course Lily as a character isn't the one supposed to be this meta): for example, we could have been shown how easy it is to fall into radicalisation especially when you're an abused and neglected child from a poor social background and a minority. (Again I'm not saying it was up to Lily as a character to understand this. She had no obligation toward Severus and isn't all mighty and a Saint. The "problem" is that the narrative is trying to portray her as such because the author truly believes this is how a good person behaves and should be looked at.)

All of this of course being unconsciously accepted, but never put in question. Lily's behavior being of course viewed more positively because no matter how flawed it was, it served honorable aims: fighting against the disgusting blood purity ideology. Her values are honorable. So to me, of course JKR was convinced of Lily's human perfection and inherent goodness because I think she wrote her according to her own views and beliefs on the matter. Which is why, if we grant importance to the narrative, her marrying someone as crual as James Potter is disturbing according of what is said of her:

"Not only was she a singularly gifted witch, she was also an uncommonly kind woman. She had a way of seeing the beauty in others even, and perhaps most especially, when that person couldn't see it in themselves."

But, when you take a step back, you realise that her marriage with James is a consequence of JKR's internalised sexism, as she heavenly implied macho and possessive behaviour such as displayed by James were attractive to girls in the end, and, if you take another step back, you realize JK never understood the seriousness of the bullying she wrote so it didn't look so appealing to her that Lily would date James as it is to us.

Then, if we really think of the characters themselves and not JKR's intentions, I think James and Lily were a good match for various reasons, not all negative.

I'm afraid this is a little clumsy and I just really want to say, I'm not blaming Lily for her behavior even if we must acknowledge the fact she wasn't a very good friend and was very far from being perfect; I'm not making a comparison between real life issues and fictional ones, or between author and fictional character: I'm trying to show why Lily appeared as such a model of goodness into JKR's eyes, which shines through the way she tells the story, because she was written according to the writer's standards - some standards and positions we cry about every day when we open twitter. It's not really about her transphobia or use of minorities, but the reasons why she thinks she has a right to give judgemental opinions and ask people to change, her own system of thinking. Her - phobia are a consequence of this but I have to talk about them to show how it seems to me JKR thinks of herself and of others.

This is not anti Lily Potter, she still was a good person and lived in a particular context which also explains certain aspects of her behavior; this has nothing to do with making Snape look better or finding him excuses.

It has everything to do with the way the author viewed her characters and certainly failed to understand the seriousness and complexity of all subjects she chose to address. With the way she sees things and how her characters behave sometimes accordingly.

(Like, for example, not making any comparison, I'm sure she really thought it was positive when she created the house elves, slaves that are happy to be slaves and making fun of those who are disturbed by their conditions and having the only free elf die; I'm sure she thought the message was good when it clearly reeks of colonialist fantasy, thus her own opinions and views as a white British in the 90s [not generalising this to anyone else!], certainly internalised.)

PLEASE MAKE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN "SHE WRITES LILY THIS WAY" AND JUST "LILY".

#I hope you understand what I want to say#Cause it's quite hard#I'm afraid the way I say things can make the fictional and the real can be mistaken for one another#But it's not what I want#JKR#JK Rowling#Rowling#jk rowling is a terf#Harry Potter#Lily Evans#Lily Potter#Lily and James#Severus snape#Pro Snape#Snapedom#Snape community#Potter#Anti Lily Evans#Anti Lily Potter#Anti James Potter#Very long post#Long post#long post

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native Tongue and the Power of Language

I recently read the book Native Tongue by Suzette Haden Elgin and found that its themes strongly resonate with what is currently going on in gender debates. Most notably, the book deals with the power of language to shape our perceptions and reality. The past few years have seen a push towards more gender-neutral language, to the point of completely changing or stripping some words of all meaning. These issues can be examined in light of Elgin’s message on the power of language, which serves as both a warning and a beacon of hope.

Native Tongue, published in 1984, is set in a highly patriarchal society 200 years from now. All progress made by women in the twentieth century has been lost, and men hold absolute power. The Earth’s economy in the twenty-second century relies on trade with various interstellar nations, and linguists are needed to learn alien languages in order to conduct trade negotiations. The novel principally focuses on Nazareth Chornyak Adiness, a linguist born to one of the 13 Linguist Lines. In the Lines, women are bred until they become barren, at which point they are sent to the Barren House for the rest of their lives. This is where the women are secretly developing their own language, Láadan, to express their own reality and regain their autonomy.

Elgin, having received a PhD in linguistics, subscribed to the controversial linguistic theory known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. In its “weak” form (which is more accepted than the “strong” form), it says that our language constrains and structures our perception of reality. In other words, people who speak different languages see the world in different ways. Moreover, the way we perceive the world depends on the word choice as well as the metaphors encoded in the language. These ideas have also been brought up by feminist thinkers outside of linguistics, such as Hélène Cixous and Luce Irigaray, who examined how language reinforces gender relations and stereotypes. In The Laugh of the Medusa, Cixous writes: “It is by writing, from and toward women, and by taking up the challenge of speech which has been governed by the phallus, that women will confirm women in a place other than that which is reserved in and by the symbolic, that is, in a place other than silence” (881). Thus, Elgin’s position that changing language can change society complements feminist writings of the time.

The book’s fictional woman’s language, Láadan, is the result of the belief that language can change reality. The creation of Láadan is primarily based on Encodings, which are “the making of a name for a chunk of the world that so far as we know has never been chosen for naming before in any human language, and that has not just suddenly been made or found or dumped upon your culture. We mean naming a chunk that has been around a long time but has never before impressed anyone as sufficiently important to deserve its own name” (Elgin 22). The appendix of the book gives some examples of words in Láadan. One of these is “doóledosh”, which means “pain or loss which comes as a relief by virtue of ending the anticipation of its coming” (332). In this way, Láadan can express the true perception of women by redefining what is significant or not.

There is a shift in perception happening today, as gender activists push for more gender neutral and inclusive language. However, this comes at the cost of denying biological reality and erasing women as a class. The most glaring example is probably the trend of replacing “woman” with “uterus-bearer”, “ovary-haver”, “menstruator”, etc. This reduces women to their body parts and is quite telling of the misogynist viewpoint these terms stem from. Indeed, since language acts as a lens through which we see the world, this change reflects the view that women are only good as child-bearers and sex partners. Moreover, the spread of this kind of language also perpetuates this ideology under the guise of “inclusive language”. As Láadan was created to show, the lack of female-centered language helps support the patriarchy.

However, Native Tongue also provides hope for the efficacy of woman-centered language. Elgin believed language could shape reality and showed it in her book. After the women of the Barren House decide to start using Láadan and teaching it to the girls, the men note: “Women, they tell me, do not nag anymore. Do not whine. Do not complain. Do not demand things. Do not make idiot objections to everything a man proposes. Do not argue. Do not get sick […] No more headaches, no more monthlies, no more hysterics… or if there are still such things, at least they are never mentioned” (303). The Linguist men, unsettled by this new dynamic, decide to make all of their women live in a separate residence, thereby inadvertently giving the women something they want. This shows how the new language altered relations between Linguist men and women and as a result brought a change to their lives. The change need not be so drastic, however, as simply using a language that expresses their views and values makes the women more cheerful and cooperative when dealing with the men. They finally have the freedom that only a language of their own can provide.

Elgin’s book is more relevant than ever at a time where feminists are fighting against the erasure of female-specific terms. The power of language is that it can oppress, like reinforcing gender stereotypes, but also liberate, as Láadan does for the Linguist women. The latter provides hope in the current battle against female erasure. We need language and writing by women, for women. As language is turned against us, so can we use it to fight back and create our own, more just, reality.

Notes:

· This essay is partly inspired by the afterword to the 2019 edition (Encoding a Woman’s Language by Susan M. Squier and Julie Vedder).

· The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has been largely abandoned in favor of biolinguistics, the linguistic school that holds that the principles underpinning the structure of language are biologically preset in the human mind and hence genetically inherited, pioneered by Noam Chomsky. Since Elgin wrote Native Tongue in light of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, this essay does not question the validity of the theory.

· For more about Láadan: https://laadanlanguage.wordpress.com/

· Native Tongue has many more themes to explore, such as the balance of power between the sexes, which I chose not to go into. I highly recommend this book, and I will definitely be reading the other two books in the trilogy.

References:

Cixous, Hélène, et al. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875–893. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3173239. Accessed 6 July 2020.

Elgin, S. H., Zumas, L., Squier, S. M., & Vedder, J. (2019). Native tongue. New York: Feminist Press at the City University of New York.

#feminism#radical feminism#radfem#linguistics#native tongue#suzette haden elgin#helene cixous#laadan

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently made a post saying I'm radfem now. So I thought perhaps I should adress that in a bit more detail. I'll try to not make this post several years long, but it's unavoidably gonna be a big post. This is to give a rough overview of my opinions, for anyone interested in knowing that.

The points I bring up, in the following order: - Patriarchy/oppression of women and girls - Gender/sex - Transgender - Femininity - Sexuality - Female only spaces - Porn industry - Prostitution - BDSM - Reproductive rights and women's rights in general - End notes/wrap up

Patriarchy/oppression of women and girls So I used to be an anti-feminist MRA and thus I didn't believe patriarchy was a thing. It took me a long while and lots of research and observing to see the fault in my ways. Admittedly, I was wrong, and now I know better. Also worth mentioning is the reason I found my way into radfem was because with my detransition I became increasingly gender critical, so if I focus extra on gender/sex opinions that's why.

Gender/sex Women and girls are oppressed in the world because of their sex, and it has nothing to do with "gender identity" and you can't opt out of oppression by transitioning or calling yourself another gender. Gender is a social construct and is just masculinity and femininity, including personality traits that can be called such. Anyone can be masculine or feminine and it doesn't make them the opposite sex or "not real" men/women. Male/female brains is not a thing. You are the sex you were born as. Woman just means adult human female and man just means adult human male.

Transgender Having dysphoria often tells people who have it that them wanting for their bodies to be of the opposite sex is what makes them, on some psychological level, of that sex. Conforming to the gender roles of the opposite sex often alleviates dysphoria cause it helps with passing, but few trans people think that the gender roles is what makes them men/women. It's just a tool to deal with dysphoria. Trans people should absolutely get the medical treatments available for their dysphoria for those who want that. Out of politeness and caring about their dysphoria, I usually refer to trans men as men and use he/him pronouns, etc, and vice versa for trans women. And on occasion I use the word "cis" to refer to people who are not trans but I don't agree with the term. I only ever use it for simplicity and in its simple meaning "not transgender" but I try to avoid it.

Femininity My stance on this might differ from other radfems but what I do definitely agree on here is that it should NOT be forced upon women/girls in society like it clearly is. I appall that and it should not happen. I also see there are lots of harmful stuff about modern femininity that also should be scrutinised. However, I think that femininity at its core can be good if you just know what you're doing, and I think especially femme lesbians seem to have a pretty good grip on that, not just myself. I think very critically about it and do encourage others to do too. I want to eradicate the forcing of femininity and its harmful aspects - but not the femininity itself. And that's actually NOT because I love being femme: it's because I was coerced to be masculine as a child, and that not only harmed me, but also made me realise and understand that femininity is a genuine and essential form of expression for my artistic mind. So, I think I do have pretty good reasons for having the views that I have on that point.

Sexuality Sexual attraction/orientation is sex-based not gender-based. Lesbians are not attracted to males/penis and gay men are not attracted to females/vagina. It's important that definition does not get changed by the trans movement and anyone thinking it's "no big deal" or think that it should be changed is a homophobe. Any male trying to force dick upon lesbians is a horribly gross lesbophobe and no it doesn't make it any better if it's a trans woman. It's very much like just another form of conversion therapy and should not be tolerated. I'm a lesbian, so it matters to me a lot. And on that point I also stand in solidarity with gay men who get to face the same crap from females/trans men. However, I'm half-okay with trans women just calling themselves lesbians as long as they can behave themselves and know they're not actual homosexual females, and vice versa for male-attracted trans men calling themselves gay. Again only because of their dysphoria, and only if they're not acting like homophobes. I'm however NOT okay with trans women invading lesbian spaces, but I'll get back to that point in a bit.

Also I'm really strongly against trans people not disclosing being trans to sex partners. Doesn't matter if they're pre- or post-op or how well they're passing. Trans feeling DON'T get to override "cis" feelings. That might not be a super specific radfem point but I notice transmeds vehemently disagree with me on that point, and it just comes across as very entitled, so yeah.

Female only spaces Are and should be for biological females only. Although I'm slightly lenient on trans women using women's bathrooms because in my own country it doesn't seem to be an issue of men abusing that loophole, but I'm NOT fine with any males using women's locker rooms, abuse victims' support groups, abuse shelters, lesbian spaces, etc. Women need our own spaces away from the male oppressors. And as a survivor or sexual assault and rape who's kinda scared of men, I do very much understand that need. Even though I look too ambiguous due to my ftm transition to get any sort of access to women only spaces, aside from bathrooms, apparently. That's my own fault though, isn't it?

Porn industry Absolutely disgusting, what the hell is going on there?! Kind of. Women and girls are being badly hurt there and it needs to stop. I don't care if that means no one ever gets to ever have porn to watch, people's safety is more important than other people just wanting something sexy to watch. Men's violence on women (in general) is being perpetuated by porn teaching them that women are objects and only there for men's sexual pleasure. And I'm pretty sure it even exacerbated my own internalised misogyny in the past when I was watching a lot of porn and searched for the worst of it. I no longer want to support the porn industry in any way. I made the decision, few weeks ago, to stop watching porn completely and so far so good, although I was close to giving into it a few days ago but didn't. I've got this.

Prostitution I used to want to become a prostitute, actually. Before I came to my senses on that point and realised it was just my traumas speaking for me again. I no longer want that at all, and it makes me feel sick to just think of it. But I read up on it a lot back then. I understand that the entire "sex industry" is directly harmful to the women in it and indirectly harmful to women not in it. I'm all for doing whatever we can to stop it. However, since I read up on it in the past, I'm kinda skeptical that the Nordic Model would be a good solution. It has a lot of issues. As I'm living in a country that has that model implemented (Sweden) and I know that there is a lot of hidden trafficking going on here that cannot be spotted or caught due to the faults of the Nordic Model. According to my own (possibly flawed) research the Australian Model seems to be better at both catching trafficking and making prostitution in general less dangerous for those involved, but by no means is that a perfect model either. I need to learn more about this perhaps, but at the end of the day I'm 100% against any form of prostitution existing.

BDSM I used to be into bdsm and didn't want to see that it's harmful, and basically just a "socially accepted" form of abuse. I used to be into "rapeplay" and a lot of humiliating kinks as the submissive because it let me "repeat" my past traumas. Along with my realisation that I'm a lesbian, I also finally understood the true depth of my traumas and no longer want to engage in anything bdsm or kinks. That has no place in my life anymore. It just kept damaging me more when I needed to heal. That made me understand that there's still abuse involved in bdsm even though it's "consensual" cause how can you make an informed consent to something you don't understand is gonna harm you?

Reproductive rights and women's rights in general I guess this covers the whole "bodily autonomy" thing and I include anything from being able to get birth control and abortions to stopping fgm and child marriages, and much more, in this category. I dunno really what to say here other than of course women and young girls being treated as cattle, abused, mutilated, raped, forced to give birth, forced to marry, etc are very important issues that need to be fixed and that asap. I'd even say such things matter the most to me when it comes to women's rights: having the right to one's own body from the moment that any female human is born. But also, reading up on those really heavy topics gets to me so bad I can't manage it. I get really bad panic attacks and just start sobbing uncontrollably. So for the sake of my own mental health, that's why I don't reblog much of that. But please believe me that is still very important stuff to highlight, talk about and get to the bottom of.

End notes/wrap up All of this and more really stems from the systematic oppression that women are constantly kept under, and I see that "red thread" connecting all these issues to that root. We need to get to the core of those problems (and many more that I didn't bring up here) which is men in general oppressing women in general. So that got me back to where I started, patriarchy. That's a nice wrap up, I think. I tried hard to not make this into a gigantic post, so that's why I left out a lot of details, explanations, my own personal experiences that led me to my opinions, etc. And yes, it's absolutely fine to ask me about my opinions on any of these things, and call me out (preferably with an explanation) if you think it's horse shit and I'll look into it.

#personal#my radfem views#i know its not super comprehensive but i aint got all night#still new to this#and still learning#im a get shit for my views on trans i think but im too fucked up to care anymore

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Radfems/Gender Criticals!

I used to strongly dislike you all. That doesn't mean I ever sent death threats or insulting DMs, this is my first time talking about this on social media. I deeply judge everyone on any side who thinks violence is the answer or acceptable simply because you do not agree with someone.

I only watched content parodising you and saw your hateful side. However, I took my time to actually read your points and concerns. I am a trans man, I have been out for 4 years. I will not insult any of you in this writing or say vile things, I ask you to do the same if you decide to interact with me. I will not say TERF, as I am aware you don't like being referred to that way, but I ask you to not call me a TIF in return in the possible comments. I will not answer. Respect should go both ways.

I will first tell you what I see now that I completely missed before, then what I think you are all missing. Not because I think you aren't educated enough, but I think some of you might have made the same mistake as I did: refuse to be open-minded and only cared about clear hate speech. I also wanna be clear that I in no way agree with you on everything, and the language some of you are using is unacceptable (same on the trans side, obviously).

I refused to think of myself as someone who used to be a woman, and didn't associate myself with womanhood at all. I still believe I was born a boy, but I cannot erase the past, I was raised a girl and experienced the world as such. And it was traumatic. I don't like to think about it. I am sure I don't have to elaborate more. I understand your hurt and suspicion of men- both trans man and people who used to live as men but now are women. I often feel guilty nowadays for not being a feminist enough when I lived as a girl. I try my best now. I know most of you think of course, not all men, but enough men, and you don't wanna risk it. I understand and feel your pain. I am still uncomfortable around a cis man I don't know in the room alone, even though I have been passing for years now.

But I feel like you are mistaking the enemy. It's rapist men, the patriarchy, sexism, etc. Any intelligent trans person would be on your side, if some of you wouldn't misgender us on purpose or paint us as traitors (trans men) and people who wanna violate you (trans women). The same men who wanna hurt you wanna hurt us just as much. A man who would hurt you would hurt a trans man, and would hate crime a trans woman. In their eyes femininity is a weakness- and since trans women are feminine, trans men used to be feminine, they hate us all and put us in the same category. We wanna fight for feminism, we have every reason to.

You cannot base your opinion on a couple shitty trans people, just like I don't base my opinion on a couple shitty radfems. I know some of you are highly intelligent, well-read people. And we do not agree on everything, there is no "Trans viewpoint" we share.

Do you think trans people wanna erase the definition of women? We sure as Hell don't. Or at least I don't. But is it really menstrusting that makes you one? I don't think so. And I think you do not all think that either. A lot of women don't menstruate (even cis women), I know more than one who don't because of medical reasons. Being a woman means you are constantly fighting against a system that oppresses you and that you feel a sisterhood with those people, you feel that strong sense of womanhood you all talk about.

Do you think all trans men like the word "mensturator" and "vagina-haver"? I don't. I never met a trans boy who does. Maybe some do, I'm not saying that. But yes, reducing women to menstruators is dehumanising. It's a weird term. It triggers my dysophoria, if I see a post about women's health, I understand it's about me without specifying it's not only women.

(Some of) you think trans men do not wanna be women because of internalised misogny. I would get a lot of hate for this from a trans platform, but I admit, a few AFAB trans people probably suffer from this. But not all. I believe almost all AFAB people have internalised misogny. It's impossible not to. I did have a lot more than I do now, and I am working on it at that very moment too. I considered that I might be a girl who was taught being masculine is only for boys- but that just isn't the case. As I grew older and became more feminist, I now see women in a completely new light. I think being a woman is a beatiful, painful, admirable yet hard life. It just isn't for me. I cherish women, the reason I hate being called one isn't because I look them down because that's how I was conditioned. It's just not who I am. Trust me, I wish I could be one. Not because it's easier to be a woman than a man, but because being a trans man is way more struggle than living like a cis girl. I experience both transphobia and sexism. I am aware I could be a masculine presenting, non-gender conforming woman. Most trans men know that. We aren't trans to escape sexism, I surely am not. I didn't stop fighting against sexism when I started transitioning, I am with you in this still everyday. I call out sexists every chance I can. It's my duty to do so. But to say all trans men just hate womanhood is simply a lie. I don't. I love you all. I think you are all brave as fuck.

We aren't the same. Do not generalise.

And now, onto trans women. I admit there are some terrible ones- but there are some terrible cis women, trans men, cis men. No statistics show that trans women are more violent. Do you think a man would undergo surgeries, hormone treatment, a lot of transphobia and a constant battle just to harass you? If a man wants to rape someone in the bathroom, he will. He won't go through years of hormone therapy to do so. It's irrealistic. Transition is not as easy as you think. Trans women wanna be your allies, just because some shitheads posted they wanna rape women, it's not a representitive.

As soon as trans women start passing, they will get the same harassment as you do. And even higher amount of violence. They will get catcalled just like you, talked down to, belittled, etc. Since they identify with womanhood, they will also internalise the messages society sends about women.

Are you annoyed they think makeup is what womanhood is about? I don't think they do, but even if you do, have kind discourse with them. Tell them how to be a good feminist, I'm sure a good portion will listen. They want equal treatment like you. I know you think they will never be fully women, but they will experience the same opression you fight against. Have them fight with you. Isn't that the goal? Why not have more supporters?

People will answer hate with hate. If you do not give us respect, they won't give you any either. Is that wrong? Of course it is. Both parties should be mindful.

But my point is; we want the same thing. We have the same enemy. Let's fight together, not against each other.

0 notes

Note

Ok I don't think 'all men are trash' but this usually comes from people who have been abused by men. Of course not all men are trash, everyone knows that! Not all men abuse but most women have been abused or had an uncomfortable moment with a man. That person talking about 'new fake feminism' and 'victimization of women' knows nothing about feminism!, Also, you can't be sexist toward men cause of historical context patriarchy etc Discrimination and sexism are very different things. This site->

Is hell!! Most ppl don't know what they are talking about here. So if you want to learn about feminism there are some amazing theorists/intersectional feminists out there, don't play attention to people on Tumblr. Feminism (even the 'modern' one) is not about hating men, is about dismantling patriarchy. Sorry i'm writing this to you but there were many wrong things about that post that can confuse people about feminism and sexism and I really like you-

I could write a lot but i dont want to annoy you and my english sucks!

Hello anon, first of all, as long as your messages are this well put and interesting you don’t have to worry about annoying me, secondly I’m not a native speaker myself so don’t worry about your english skills either (which seem very good to me, btw)let me tell you that I understand where you come from and I even agree, at least on some points, but I also feel the need to respond to a few points:

“This usually comes from people who have been abused by men [...] most women have been abused or had an uncomfortable moment with a man” okay but there’s a huge difference between feeling skittish/uncomfortable around men and or being able to trust them and saying and believing that any cis man is scum and deserves to be killed. because this was the point of the post, it was aimed to those people (and there’s a lot of those on this site) that believe this is feminism. it’s not. I’ve been a victim myself, for years, and I still have my share of issues with men, this doesn’t give me the right to be a shitty, hateful person.

“That person talking about 'new fake feminism' and 'victimization of women' knows nothing about feminism!“ I’m pretty sure she was referring to the same people I talked about ^

“you can't be sexist toward men“ I strongly disagree; if you discriminate someone purely because of their gender you’re being sexist. it works both ways, that’s what’s great about equality.

believe me when I say that I know that true feminism is not what you experience on this site, but that’s exactly why that post is so important! because it’s on tumblr! it was not aimed towards feminism but people being mean just because this world sucks and since being a woman is hard this gives them the right to do so. I’m sorry but I won’t stand for this.

tl;dr: people can be mean regardless their gender and people can be trustworthy regardless of their gender, don’t let people on tumblr tell you that it’s right to hate on an entire category of people just because it’s widely accepted here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TJ Demos – Against the Anthropocene. The Many Names of Resistance

vimeo

T.J. Demos | Against the Anthropocene from Kaaitheater on Vimeo.

How do we critically reflect on climate change through the arts? TJ Demos’ previous books include “Decolonising Nature” and his latest book “Against the Anthropocene”. His latest book has a more activist stance. The term Anthropocene coined in the early 2000s. The term supported a strongly technical and scientific sense, with not much in the way of political discussions. This proved problematic for TJ Demos, hence his polemical work “Against the Anthropocene”.

There is no such thing as discrete human subjectivities, we are connected to nature and enmeshed with it. Anna Sing’s book “Multispecies Salon” argues this. The term Anthropocene looks more at humans only, and in general as being responsible for climate change. However it is not all humans, but particular ones that are responsible for climate change. Some have been more adversely affected depending on wealth, poverty, class, gender, race etc. There is a disproportionate impact of climate change depending on who and where you are.

“Climate change represents the burning of Africa.” - TJ Demos

Political conference delegates agree on 1.5 degrees celcius warming, but this would be catastrophic for people in coastal regions in Bangladesh for example. There is a suggestion that geoengineering may be a necessary response to climate change. Technofixes for climate change deals with the symptoms but not the causes. Economic growth is seen to be compatible with climate solutions, but is this belief true? The Capitalocene these argues that climate change has been going on for 500 years, but if we are to address it properly we need to address this capitalist history.

The dates of the Anthropocene are proposed to have begun in the 1950s by geologists. This is when nuclear power was globalised. The book “Anthropocene or Capitalocene” edited by Jason W. Moore, rejects technoscientific empiricism in favour of looking at the cause from a political, colonial perspective. Capitalocene emphasises environmental violence and injustice against oppressed people and nature. Intersectionalist discussions look at the racial and colonial injustice that has accompanied the environmental transformation.

Forensic Architechture has also looked at the Capitalocene. Eyal Wiseman suggests that environmental transformation or climate change is not an unintended accident, but rather an intended aim of colonialism from the start. TJ Demos helped set up the Centre for Creative Ecologies to encourage this research and discourse. There is a risk of environmentalism becoming a privileged domain. In his view it needs to be linked to social justice domains. Environmentalism must not become a white domain, it needs to be intersectionalist and support social justice.

The Cthulucene: a term coined by Donna Haraway, from her book “Staying with the Trouble”. Linked to HP Lovecraft’s Cthulu, without the sexist undertones. Diverse mythological constructions such as naga, pachamama, or mother earth. Cthulucene is the era of multiscpecies being. Visualisations of the Cthulucene have been created by artists such as the Crochet Coral Reef. They sometimes show them as bleached to emphasise their destruction. Also shown are Navajo weaving and Pigeon Ring.

We need many names. A “Manifesto for the Gynecene” was an idea by artists Alexandra Pirici and Raluca Voinea in 2015. They proposed that patriarchy should be excluded in all its violent expressions such as colonialism, profit etc. Practices such as pachamana and rights of mother earth come out of indigenous traditions which are an example of the Gynacene. Defend Our Mother was an example of a poster by Fabiana Rodriguez, Gynacene aesthetics. Standing Rock against Dakota Access pipeline: “Water is life” proposing a different ontology based within a non-capitalist, non-commoditised understanding of environmental issues. Geontology is seeing the conditions of being as rift zones where different world views come into a clashing relationship.

Mountain top removal mining is when companies blow up mountain tops to get at coal underneath. Plantationocene is where agriculture has been turned into a science of colonialism. Anna Sing shows how divisions between genders and races are regimented into Capitalist labour systems, within a monocrop area. Plasticene is about the spread of plastics and micropolymers throughout the world. This is only going to grow in the future. We are plasticising the planet. Plastic as a material of Capitalism. The Pyrocene relates to the spread of wildfires such as in California.

"A World at War" is an article in New Republic. Our only hope is to mobilise like we did in world war 2. They want to decrease the CO2 in the air to under 300 parts per million. But they are looking at it from only a technoscientific viewpoint, and not looking at the 500 year history of Capitalism and its effects on climate change. Communities of colour are more endangered by incinerators than others, their lives are seen as less important somehow. We must decolonise environmentalism. Avoid the ecologies of affluence of white environmentalism. Ecological struggles are really the struggle for universal emancipation.

Artistic project “Forest Law”, 2014, investigates decades of oil exploitation in the Equadorian Amazon by oil companies, drilling for oil and leaving oil by-products on the floor. Artists building solidarities and connections with social movements is crucial. “The Party of Others”, a political party that is non-anthropocentric and includes animals and others so they can have a political voice. Rosa Braidotti calls it developing a zoe-centred (animal or non-human) egalitarianism. “The Climate Games” included Inflatables to activate participants, creating space between activists and police. There is a history of the use of cobblestones in revolutions in France. Non-violent civil shutting down of coal mines, “we are nature defending itself”, avoiding the anthropocentrism of the nature/culture binarism. In New York “not an alternative” wrote a letter to museums to detach from fossil fuel funding. David Koch, a fossil fuel corporate figure, got kicked off the board of the American Natural History Museum. Liberate Tate have been doing performance interventions showing the cost of petrocapitalism, and got Tate to stop its association with BP: institutional liberation. Non-reformist reform, welcomes small steps but also recognises it is inadequate.

Discussion after the talk:

Sustainability as an empty signifier. It supports not ecological sustainability but economical sustainability. Post-representational system in which language is dead. Evidence doesn’t necessarily change minds, people become sensitive and embedded in their positions. Create art based within the affect of social justice. What is Art in the post-representational present?

Billionaires buying escape silos in case of catastrophic futures. Others cannot do this. “Breakthrough Institute” (setup by people such as Bill Gates and other corporate leaders) don’t talk about racism or economic inequality, they talk about saving humanity and humanism through geoengineering and saving humanity with all its inequalities intact.

Reference:

Demos, T.J.; "Against the Anthropocene"; Sternberg Press, 2017.

0 notes

Text

Setting Fire to Social Justice

Call-out culture refers to the tendency among progressives, radicals, activists, and community organizers to publicly name instances or patterns of oppressive behaviour and language use by others. People can be called out for statements and actions that are sexist, racist, ableist, and the list goes on. Because call-outs tend to be public, they can enable a particularly armchair and academic brand of activism: one in which the act of calling out is seen as an end in itself.

What makes call-out culture so toxic is not necessarily its frequency so much as the nature and performance of the call-out itself. Especially in online venues like Twitter and Facebook, calling someone out isn’t just a private interaction between two individuals: it’s a public performance where people can demonstrate their wit or how pure their politics are. Indeed, sometimes it can feel like the performance itself is more significant than the content of the call- out. This is why “calling in” has been proposed as an alternative to calling out: calling in means speaking privately with an individual who has done some wrong, in order to address the behaviour without making a spectacle of the address itself.

In the context of call-out culture, it is easy to forget that the individual we are calling out is a human being, and that different human beings in different social locations will be receptive to different strategies for learning and growing. For instance, most call-outs I have witnessed immediately render anyone who has committed a perceived wrong as an outsider to the community. One action becomes a reason to pass judgment on someone’s entire being, as if there is no difference between a community member or friend and a random stranger walking down the street (who is of course also someone’s friend). Call-out culture can end up mirroring what the prison industrial complex teaches us about crime and punishment: to banish and dispose of individuals rather than to engage with them as people with complicated stories and histories.

It isn’t an exaggeration to say that there is a mild totalitarian undercurrent not just in call-out culture but also in how progressive communities police and define the bounds of who’s in and who’s out. More often than not, this boundary is constructed through the use of appropriate language and terminology – a language and terminology that are forever shifting and almost impossible to keep up with. In such a context, it is impossible not to fail at least some of the time. And what happens when someone has mastered proficiency in languages of accountability and then learned to justify all of their actions by falling back on that language? How do we hold people to account who are experts at using anti-oppressive language to justify oppressive behaviour? We don’t have a word to describe this kind of perverse exercise of power, despite the fact that it occurs on an almost daily basis in progressive circles. Perhaps we could call it Anti-Oppressiveness.

Humour often plays a role in call-out culture and by drawing attention to this I am not saying that wit has no place in undermining oppression; humour can be one of the most useful tools available to oppressed people. But when people are reduced to their identities of privilege (as white, cisgender, male, etc.) and mocked as such, it means we’re treating each other as if our individual social locations stand in for the total systems those parts of our identities represent. Individuals become synonymous with systems of oppression, and this can turn systemic analysis into moral judgment. Too often, when it comes to being called out, narrow definitions of a person’s identity count for everything.

No matter the wrong we are naming, there are ways to call people out that do not reduce individuals to agents of social advantage. There are ways of calling people out that are compassionate and creative, and that recognize the whole individual instead of viewing them simply as representations of the systems from which they benefit. Paying attention to these other contexts will mean refusing to unleash all of our very real trauma onto the psyches of those we imagine to only represent the systems that oppress us. Given the nature of online social networks, call-outs are not going away any time soon. But reminding ourselves of what a call-out is meant to accomplish will go a long way toward creating the kinds of substantial, material changes in people’s behaviour – and in community dynamics – that we envision and need.