#american museum history.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"At the time of bombing, a woman was 17, and she suffered a severe thigh bone fracture. So she was unable to walk. She spent her whole life in a wheelchair, and when she turned 76, she quickly developed severe anemia, and she became very weak. "We examined her blood and found that acute leukemia was quickly growing inside her body. Then she said to me, ‘I have long believed the atomic bomb was living, surviving inside.’ Maybe she had a feeling that the atomic bomb had entered her body. She didn’t use ‘radiation’ — a special term, ‘radiation.’ But she said, ‘The atomic bomb entered me and survived until now.’”

The Last Survivors Speak. It’s Time to Listen.

By Kathleen Kingsbury, W.J. Hennigan and Spencer Cohen Photographs by Kentaro Takahashi Aug. 6, 2024

The waiting room of the Red Cross hospital in downtown Hiroshima is always crowded. Nearly every available seat is occupied, often by elderly people waiting for their names to be called. Many of these men and women don’t have typical medical histories, however. They are the surviving victims of the American atomic bomb attack 79 years ago.

Not many Americans have Aug. 6 circled on their calendars, but it’s a day that the Japanese can’t forget. Even now, the hospital continues to treat, on average, 180 survivors — known as hibakusha — of the blasts each day.

When the United States dropped an atomic weapon on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, the entire citizenries of both countries were working feverishly to win World War II. For most Americans, the bomb represented a path to victory after nearly four relentless years of battle and a technological advance that would cement the nation as a geopolitical superpower for generations. Our textbooks talk about the world’s first use of a nuclear weapon.

Many today in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where the United States detonated a bomb just three days later, talk about how those horrible events must be the last uses of nuclear weapons.

The bombs killed an estimated 200,000 men, women and children and maimed countless more. In Hiroshima 50,000 of the city’s 76,000 buildings were completely destroyed. In Nagasaki nearly all homes within a mile and a half of the blast were wiped out. In both cities the bombs wrecked hospitals and schools. Urban infrastructure collapsed.

Americans didn’t dwell on the devastation. Here the bombings were hailed as necessary and heroic acts that brought the war to an end. In the days immediately after the nuclear blasts, the polling firm Gallup found that 85 percent of Americans approved of the decision to drop atomic bombs over Japan. Even decades later the narrative of military might — and American sacrifice — continued to reign.

For the 50th anniversary of the war’s end, the Smithsonian buckled to pressure from veterans and their families and scaled back a planned exhibition that would have offered a more nuanced portrait of the conflict, including questioning the morality of the bomb. The Senate even passed a resolution calling the Smithsonian exhibition “revisionist and offensive” and declared it must “avoid impugning the memory of those who gave their lives for freedom.”

In Japan, however, the hibakusha and their offspring have formed the backbone of atomic memory. Many see their life’s work as informing the wider world about what it’s like to carry the trauma, stigma and survivor’s guilt caused by the bombs, so that nuclear weapons may never be used again. Their urgency to do so has only increased in recent years. With an average age of 85, the hibakusha are dying by the hundreds each month — just as the world is entering a new nuclear age.

Countries like the United States, China and Russia are spending trillions of dollars to modernize their stockpiles. Many of the safeguards that once lowered nuclear risk are unraveling, and the diplomacy needed to restore them is not happening. The threat of another blast can’t be relegated to history.

And so, as another anniversary of Aug. 6 passes, it is necessary for Americans — and the globe, really — to listen to the stories of the few human beings who can still speak to the horror nuclear weapons can inflict before this approach is taken again.

Chieko Kiriake was on a break from her job at a tobacco factory in Hiroshima. She was 15 years old.

"Everything was burned. People were walking around with their clothes burned off, their hair singed and standing on end. Their faces were swollen, so much so that you couldn’t tell who was who. Their lips were swollen too, too swollen to speak. Their skin would fall right off and hang off their hands at the fingernails, like an inside-out glove, all black from the mud and ash. It was almost like they had black seaweed hanging from their hands.

"But I was thankful that some of my classmates were alive, that they were able to make their way back.

"Swarms of flies came and laid eggs in the burns, which would hatch, and the larvae would start squirming inside the skin. They couldn’t stand the pain. They’d cry and plead, ‘Get these maggots out of my skin.’

"The maggots would feast on the blood and pus and get so plump and squirm. I didn’t dare use my bare hands, so I brought my chopsticks and picked them out one by one. But they kept hatching inside the skin. I spent hours picking those maggots out of my classmates.”

Hiroe Kawashimo’s mother was at homein Hiroshima. She was born eight months later.

On Aug. 6, 1945, Hiroe Kawashimo wasn’t yet born. She was in utero; her mother was around 1 kilometer from ground zero when she was exposed to the bomb’s radiation in Hiroshima. Ms. Kawashimo was born several months later, weighing 500 grams, according to her mother — apparently so small, she could fit in a rice bowl. She was one of numerous children exposed to the bomb while in utero and diagnosed with microcephaly, a smaller head.

Seiji Takato was at home with his mother in Hiroshima. He was 4 years old.

"I remember the burnt smell. I was 4 years old. And I don’t really remember the immediate symptoms. But some years later, I had boils on my legs, and they didn’t heal for a long time. That made me really hate going to school. Later the lymph nodes in my armpits and legs swelled up, and I had to have them cut open three times.”

Seiichiro Mise was at home in Nagasaki playing the organ, mimicking the sounds of B-29 bombers. He was 10 years old.

"I got married in 1964. At the time, people would say that if you married an atomic bomb survivor, any kids you had would be deformed.

"Two years later, I got a call from the hospital saying my baby had been born. But on my way, my heart was troubled. I’m an atomic bomb victim. I experienced that black rain. So I felt anguished. Usually new parents simply ask the doctor, ‘Is it a boy or girl?’ I didn’t even ask that. Instead, I asked, ‘Does my baby have 10 fingers and 10 toes?’

The doctor looked unsettled. But then he smiled and said it was a healthy boy. I was relieved.”

Kunihiko Sakuma was at home with his mother in Hiroshima. He was 9 months old.

"There are people today who still find it difficult to talk about what they experienced. It could be their advanced age, or they don’t feel up to it physically. Often they just don’t feel well, even though they don’t know why.

"So I’d ask them, ‘By the way, where were you during the bombing?’ People died or got sick not just right after the bombing. The reality is, their symptoms are emerging even today, 79 years later.

"I thought all this was in the past. But as I started talking to survivors, I realized their suffering was still ongoing.

"The atomic bomb is such an inhumane weapon, and the effects of radiation stay with survivors for a very long time. That’s why they need our continued support.”

Minoru Hataguchi’s mother was at home. His father was at work next to Hiroshima Station and never came home. He was born seven months later.

"For the first time, at 21, I was officially recognized as an atomic bomb survivor.

"But I hated that. Why should I be labeled a survivor, when I was born the year after the bomb, 20 kilometers away from the epicenter?

"I hated even looking at the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Health Handbook, and I quickly put it away in my desk drawer. I didn’t want the discrimination, and I didn’t want the pity. Until I was in my 50s, I didn’t tell anyone that I was a survivor.”

Now a doctor, Masao Tomonaga was asleep on the second floor of his home in Nagasaki at the time of the bombing. He was 2 years old.

"At the time of bombing, a woman was 17, and she suffered a severe thigh bone fracture. So she was unable to walk. She spent her whole life in a wheelchair, and when she turned 76, she quickly developed severe anemia, and she became very weak.

"We examined her blood and found that acute leukemia was quickly growing inside her body. Then she said to me, ‘I have long believed the atomic bomb was living, surviving inside.’ Maybe she had a feeling that the atomic bomb had entered her body. She didn’t use ‘radiation’ — a special term, ‘radiation.’ But she said, ‘The atomic bomb entered me and survived until now.’”

Shigeaki Mori was crossing a bridge on his way to school in Hiroshima. His wife, Kayoko, is also a survivor. He was 8 years old; she was 3 years old.

"People still don’t get it. The atomic bomb isn’t a simple weapon. I speak as someone who suffers until this day: The world needs to stop nuclear war from ever happening again. But when I turn on the news, I see politicians talk about deploying more weapons, more tanks. How could they? I wish for the day they stop that.”

Keiko Ogura was standing on a road near her home in Hiroshima. She was 8 years old.

"As survivors, we cannot do anything but tell our story. ‘For we shall not repeat the evil’ — this is the pledge of survivors. Until we die, we want to tell our story, because it’s difficult to imagine.

"Now what survivors worry about is to die and meet our family in heaven. I heard many survivors say, ‘What shall I do? On this planet there are still many many nuclear weapons, and then I’ll meet my daughter I couldn’t save. I’ll be asked: Mom, what did you do to abolish nuclear weapons?’

"There is no answer I can tell them.”

A small pink booklet fits squarely in Shigeaki Mori’s breast pocket — a cherished possession that over the years has become more closely tied to his self-identity. The Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Health Handbook grants him access to free medical checkups and treatment, which at age 87 is critical. Flip open the first page to see his distance from the bomb when it detonated that bright August morning and flip another page to begin tracing years of his health history, written in neat rows of Japanese script.

Barack Obama was the first sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima, in 2016 — in sharp contrast to the regular visits of American leaders to Europe to commemorate major battles there. Mr. Mori was one of two survivors who spoke briefly with Mr. Obama after his remarks, leading to an emotional embrace between the two men.

On his living room wall, Mr. Mori proudly displays a photograph of that moment, alongside dozens of other mementos — including a photo with the pope — from his work over decades to remind the world of what happened in Hiroshima. Many Japanese hoped Mr. Obama’s visit would bring an official apology for the bombings; it did not. The president, however, did not shy away from recognizing the destruction of that day.

The camphor trees at Sanno Shrine in Nagasaki survived the bombing and continue to grow.

“We stand here, in the middle of this city, and force ourselves to imagine the moment the bomb fell. We force ourselves to feel the dread of children confused by what they see. We listen to a silent cry,” Mr. Obama said. “Mere words cannot give voice to such suffering, but we have a shared responsibility to look directly into the eye of history and ask what we must do differently to curb such suffering again.”

He recognized that voices like Mr. Mori’s are fleeting. “Someday the voices of the hibakusha will no longer be with us to bear witness,” Mr. Obama said. “But the memory of the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, must never fade. That memory allows us to fight complacency. It fuels our moral imagination. It allows us to change.”

The Smithsonian is in the midst of planning an exhibition on World War II, with a spotlight on the two bombed cities. It’s time for the next generation to bear witness and demand change.

#wwii#history#transcript under the cut but i would highly recommend clicking the link#there are photographs and formatting that i couldn't capture#also. drive-by reference to the enola gay air and space museum exhibit controversy truly one of the most insane things to ever happen in#american museum history.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

the other side by dean cornwell (1918)

#vintage#art#painting#oil painting#vintage aesthetic#aesthetic#oil on canvas#history#artwork#romantic academia#1900s#fine art#dark academia#canvas#artist#beauty#early 1900s#old art#old paintings#classic art#19th century art#oil on wood#culture#art history#vintage art#history aesthetic#classical art#museum#american art

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Night and Her Daughter Sleep, Mary L. Macomber, 1902

#art#art history#Mary L. Macomber#female artists#allegory#allegorical art#American art#20th century art#oil on canvas#Smithsonian American Art Museum

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

By Charles Holloway (american, 1859-1941)

"A man and a woman in the forest"

#charles holloway#odilon redon#Art#Artist#Art history#Artwork#History#Painting#Painter#Oil painting#Pastel#Symbolist#Symbolism#art nouveau#art nude#Classical art#traditional art#figurative#illustration#traditional painting#american art#Symbolist art#Symbolist painting#19th century#19th century art#museum#1900s#1900s art#mythical#mythology

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

This spectacular Stegosaurus…

🦴 measures 11.5 ft (3.5 m) tall and 27 ft (8.2 m) long. 🦴 is mounted in a defensive pose, with its spiked tail raised in the air. 🦴 lived 150 million years ago in what’s now the western U.S.

Thought to be the largest and one of the most complete Stegosaurus specimens ever uncovered, Apex is now on view in the Museum’s Kenneth C. Griffin Exploration Atrium. This exhibit is included with any admission.

#science#amnh#museum#fossil#nature#natural history#animals#dinosaur#fact of the day#did you know#paleontology#stegosaurus#research#museum of natural history#natural history museum#american museum of natural history

946 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Shiryn Ghermezian

US President Joe Biden signed into law on Wednesday a bill that would make it possible for the nation’s only museum dedicated exclusively to the American Jewish experience to join the Smithsonian Institution, which would help support its existence for years to come.

Bill H.R. 7764 establishes a commission that will examine if the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia can join the Smithsonian Institution. The commission of eight people must submit a report with its findings to Congress and the president within two years of its first meeting. The bill was sponsored by Jewish US Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) and introduced in March. It was passed by the House of Representatives in September and the Senate did the same earlier this month. Both votes were unanimous.

Before the bill was passed to Biden’s desk, Wasserman Schultz said in a Facebook post that signing it into law “would help reject harmful prejudices by educating people about the many contributions of Jewish Americans.”

The Smithsonian Institution is the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, which includes 21 museums, 14 education and research centers, and the National Zoo. If the Weitzman museum, located on Independence Mall in Philadelphia, was to join the Smithsonian Institution, it would become one of the Smithsonian museums in the US dedicated to minority groups such as the African American History and Culture Museum, the American Indian Museum, and National Museum of Asian Art. Museums under the umbrella of the Smithsonian Institution also receive federal government support.

Established in 1976, the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History houses one of the largest collections of Jewish American artifacts in the nation, with more than 30,000 objects.

#joe biden#weitzman national museum of american jewish history#debbie wasserman schultz#smithsonian institution

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

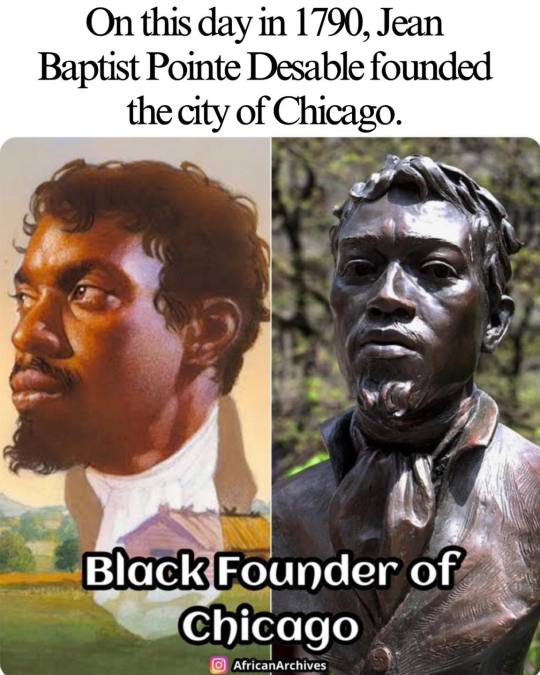

Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable was born in Saint-Domingue, Haiti (French colony) during the Haitian Revolution. At some point he settled in the part of North America that is now known as the city of Chicago and was described in historical documents as "a handsome negro" He married a Native American woman, Kitiwaha, and they had two children. In 1779, during the American Revolutionary War, he was arrested by the British on suspicion of being an American Patriot sympathizer. In the early 1780s he worked for the British lieutenant-governor of Michilimackinac on an estate at what is now the city of St. Clair, Michigan north of Detroit. In the late 1700's, Jean-Baptiste was the first person to establish an extensive and prosperous trading settlement in what would become the city of Chicago. Historic documents confirm that his property was right at the mouth of the Chicago River. Many people, however, believe that John Kinzie (a white trader) and his family were the first to settle in the area that is now known as Chicago, and it is true that the Kinzie family were Chicago's first "permanent" European settlers. But the truth is that the Kinzie family purchased their property from a French trader who had purchased it from Jean-Baptiste. He died in August 1818, and because he was a Black man, many people tried to white wash the story of Chicago's founding. But in 1912, after the Great Migration, a plaque commemorating Jean-Baptiste appeared in downtown Chicago on the site of his former home. Later in 1913, a white historian named Dr. Milo Milton Quaife also recognized Jean-Baptiste as the founder of Chicago. And as the years went by, more and more Black notables such as Carter G. Woodson and Langston Hughes began to include Jean-Baptiste in their writings as "the brownskin pioneer who founded the Windy City." In 2009, a bronze bust of Jean-Baptiste was designed and placed in Pioneer Square in Chicago along the Magnificent Mile. There is also a popular museum in Chicago named after him called the DuSable Museum of African American History.

x

#Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable#Haitian Revolution#Chicago history#founder of Chicago#black history#Native American wife#Kitiwaha#American Revolutionary War#British arrest#Michilimackinac#St. Clair Michigan#trading settlement#Chicago River#John Kinzie#European settlers#Great Migration#Carter G. Woodson#Langston Hughes#Windy City#bronze bust#Pioneer Square#Magnificent Mile#DuSable Museum#African American history

588 notes

·

View notes

Text

What's up MASHblr I went to the National Museum of American History last week and they had the signpost on display and I was sooo normal about it I swear

#i didn't know it was there so I had a Moment when I turned and saw it#mash#m*a*s*h#mashblr#national museum of american history#smithsonian#also the group photo on the side. precious#i promise I am capable of being average#personal

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Young woman in a black and green bonnet, looking down (c. 1890). By Mary Cassatt. Princeton University Art Museum.

#mary cassatt#princeton art museum#impressionism#art#pastel on paper#pastel#princeton university#art history#painting#artwork#19th century art#female portrait#europe#1890s#circa 1890#1890s fashion#1890s dress#1890s art#historical fashion#fashion history#late 19th century#19th century#19th century fashion#19th century dress#belle epoque#paris#women in art#female painters#a#american painter

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC

photo: David Castenson

#national museum of african american history and culture#black and white photography#architecture#washington dc#photographers on tumblr

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afternoon Dress. American. 1865.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#art#culture#history#american history#the metropolitan#the metropolitan museum of art#the met#civil war#the civil war#modern history#dress#women’s history

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

For #Caturday:

Ceramic bottle modeled in the form of a standing feline, decorated with resist-painted motif. Gallinazo style (aka Virú culture), NW Peru, Early Intermediate Period, c. 200 BCE - 600 CE. Spotted at the American Museum of Natural History NYC.

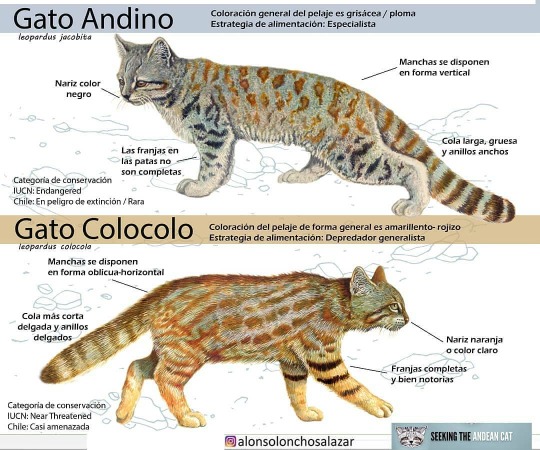

PS: this vessel may depict the Peruvian subspecies of Pampas Cat aka Northern Colocolo (Leopardus colocola garleppi). The Andean Mountain Cat (Leopardus jacobita) is also often suggested, but their range is more southern and higher elevation than where the Virú were? Also note the stripier legs on the Colocolo similar to the ceramic:

#cat#cats in art#feline#ceramics#effigy vessel#pre-conquest#Peruvian att#South American art#Indigenous art#Gallinazo#Virú#American Museum of Natural History#museum visit#Caturday#animals in art#Pampas Cat#Colocolo#Andean Mountain Cat#wild cats#mammalogy#zoology#species ID#ID#infographic#Peruvian art

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Ethan Porter (1847-1923) "Untitled (Cracked Watermelon)" (c. 1890) Oil on canvas Located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York, United States

Porter was among the first African American artists to exhibit his work nationally and the only one to specialize in still lifes. The painting's subject—originally an African gourd brought to the New World by seventeenth-century Spaniards and cultivated by colonists—is significant. Porter chose to paint a watermelon, an earlier symbol of American abundance—and during the Civil War period one particularly associated with free Blacks—when it was increasingly defined by virulent stereotyping. By reclaiming the subject in artistic terms, Porter challenged a contemporary racist trope.

#paintings#art#artwork#still life painting#watermelon#charles ethan porter#oil on canvas#fine art#the metropolitan museum of art#the met#museum#art gallery#american artist#african amerian artist#black artists#history#art analysis#freedom#fruit#fruits#food#1890s#late 1800s#late 19th century

964 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Winthrop Chanler (Mrs. John Jay Chapman), John Singer Sargent, 1893

#art#art history#John Singer Sargent#portrait#portrait painting#Gilded Age#American art#19th century art#oil on canvas#Smithsonian American Art Museum

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Say hello to my little friend, Ray de Lucia (foto Alex J. Rota)

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s a festive Throwback Thursday photo from 1969! On this Thanksgiving, the world-famous parade passed the Museum’s 77th Street turret with a very special float: a sauropod dinosaur. This inflatable Apatosaurus measured an impressive 60 ft (18.3 m) long! The giant green dinosaur featured big eyes, a wide grin, and a 20-ft (6-m) tail. The original Apatosaurus balloon made its first parade debut in 1963 and was retired from service in 1976.

Photo: Image no. 62158_21a, © AMNH Library

#amnh#museum#natural history#dinosaur#fact of the day#did you know#american museum of natural history#tbt#throwback#thanksgiving#macys thanksgiving day parade

823 notes

·

View notes