#age of revolutions in Atlantic World

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Idk if you’ve already answered this but how much English did Lafayette know before he came to the colonies? Did he practice English when he came to the colonies outside of being surrounded by English speakers? Did he speak French while he was in the colonies?

Dear Anon,

thank you for the question!

La Fayette spoke very little English before he came to America. At this point in time and in his circles of society French was the universal and cosmopolitan language and therefor the need never arose for him to learn English, unlike for many of us today. He certainly met British officers in France, and he also spent a few weeks with his uncle-by-marriage in London – said uncle was the French ambassador to Great Britan. It is reasonable to assume that La Fayette caught on to some expressions and phrases but nothing that could be called a substantial understanding of the English language.

He was however determined to learn English as soon as he decided to embark for America – as he told Washington, he came to learn and not to teach and understanding English was vital for getting along with the locals, the troops he hoped to command and his fellow officers – it was also a sign of respect since many French officers who came to America never bothered to learn English.

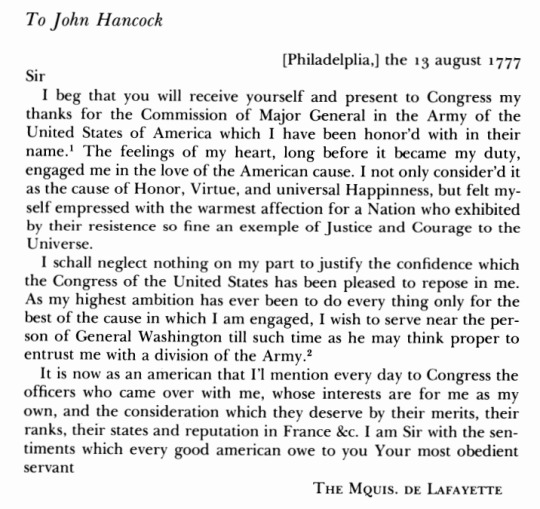

It took approximately six weeks (depending on weather, the type of ship, etc.) to cross the Atlantic Ocean at that time and La Fayette (after his seasickness abated) used the time to learn English. Therefore, when he finally arrived in America, his English was still very much a work in progress, but he could hold simple conversations. He and his party arrived in America on June 13th 1777, and this is an example of his English skills on August 13th:

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, p. 103.

This is the earliest known letter that La Fayette wrote in English, and it is believed that he had help in writing it. For comparison, here is an excerpt from his first letter known to George Washington from October 14th:

Give me leave, dear general, to Speack to you about my own ⟨business⟩ with all the confidence of a son, of a friend, as you favoured me with those two so precious titles—my respect, my affection for you, answer to my own heart that I deserve them on that side as well as possible—Since our last great conversation I would not tell any thing to your excellency, for my taking a division of the army—you were in too important occupations to be disturbed—for the Congress he was in a great hurry, and in such a time I take my only right of fighting; I forget the others—now that the honorable Congress is settled quiete, and making promotions, that some changements are ready to happen in the divisions, and that I endeavoured myself the 11 september to be acquainted with a part of the army and Known by them, advise me, dear general, for what I am to do—it is not in my character to examine if they have had, if they can have never some obligations to me, I am not usued to tell what I am, I wo’nt Make no more any petition to Congress because I can now refuse, but not ask from them, therefore, dear general, I’l conduct myself by your advices. consider, if you please, that europe and particularly france is looking upon me—That I want to do some thing by myself, and justify that love of glory which I left be known to the world in making those sacrifices which have appeard so surprising, some say so foolish[.] do not you think that this want is right? in the begining I refused a division because I was diffident of my being able to conduct it without Knowing the character of the men who would be under me. now that I am better acquainted no difficulty comes from me—therefore I am ready to do all what your excellency will think proper—you Know I hope with what pleasure and satisfaction I live in your family: be certain that I schall be very happy if you judge that I can Stay in america without any particular employement when Strangers come to take divisions of the army, and when myself by the only right of my birth should get in my country without any difficulty a body of troops as numerous as is here a division

“To George Washington from Major General Lafayette, 14 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-11-02-0515. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 505–508.] (01/02/2025)

You can read the letter just fine and understand what he wanted to say but there are still mistakes and especially when compared to his letter to Hancock.

I could imagen that La Fayette used his convalescence after the Battle of Brandywine to further study English, but I have no hard proof to that. With Washington’s aide-de-camps, particularly John Laurens and Alexander Hamilton, he was surrounded by people who knew both French and English and were willing to help him and translate for him if need be. But by all accounts, being surrounded by English speaking people and very eager to learn (and having a talent for languages in general) La Fayette fairly quickly got the hang of it.

While in America, he also spoke French. He spoke French with some of the Frenchmen there (other officers, soldiers, his own staff) and famously translated for General Washington and General Rochambeau during the Conference at Hartford in September of 1780. He also still wrote some letters in French – there are for example a number of letters to Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson written in French even though the majority of La Fayette’s correspondence with these and other people was in English.

I hope that answered your question and I hope you have/had a lovely day!

#ask me anything#anon#first ask of 2025 lets gooo!#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#lafayette#french history#american history#american revolution#history#letter#1777#1780#george washington#john hancock#alexander hamilton#john laurens#thomas jefferson#general rochembeau

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

imperialism and science reading list

edited: by popular demand, now with much longer list of books

Of course Katherine McKittrick and Kathryn Yusoff.

People like Achille Mbembe, Pratik Chakrabarti, Rohan Deb Roy, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, and Elizabeth Povinelli have written some “classics” and they track the history/historiography of US/European scientific institutions and their origins in extraction, plantations, race/slavery, etc.

Two articles I’d recommend as a summary/primer:

Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. May 2016.

Kathryn Yusoff. “The Inhumanities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020.

Then probably:

Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. “Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times.” Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives. 2023.

Sharae Deckard. “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden.” 2010. (Chornological overview of development of knowledge/institutions in relationship with race, slavery, profit as European empires encountered new lands and peoples.)

Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017, (Interesting case study. US corporations were building fruit plantations in Latin America and rubber plantations in West Africa during the 1920s. Medical doctors, researchers, and academics made a strong alliance these corporations to advance their careers and solidify their institutions. By 1914, the director of Harvard’s Department of Tropical Medicine was also simultaneously the director of the Laboratories of the Hospitals of the United Fruit Company, which infamously and brutally occupied Central America. This same Harvard doctor was also a shareholder in rubber plantations, and had a close personal relationship with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which occupied West Africa.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties.” 2008. (Case study of how British wealth and industrial development built on botany. Examines Joseph Banks; Kew Gardens; breadfruit; British fear of labor revolts; and the simultaneous colonizing of the Caribbean and the South Pacific.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” 2014. (Indigenous knowledge systems; “nuclear colonialism”; US empire in the Pacific; space/satellites; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.)

Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal #115, February 2021. (”Pest control”; termites; mosquitoes; fear of malaria and other diseases during German colonization of Africa and US occupations of Panama and the wider Caribbean; origins of some US institutions and the evolution of these institutions into colonial, nationalist, and then NGO forms over twentieth century.)

Some of the earlier generalist classic books that explicitly looked at science as a weapon of empires:

Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World; Delbourgo’s and Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World; the anthology Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World; Canzares-Esquerra’s Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World.

One of the quintessential case studies of science in the service of empire is the British pursuit of quinine and the inoculation of their soldiers and colonial administrators to safeguard against malaria in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia at the height of their power. But there are so many other exemplary cases: Britain trying to domesticate and transplant breadfruit from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to feed laborers to prevent slave uprisings during the age of the Haitian Revolution. British colonial administrators smuggling knowledge of tea cultivation out of China in order to set up tea plantations in Assam. Eugenics, race science, biological essentialism, etc. in the early twentieth century. With my interests, my little corner of exposure/experience has to do mostly with conceptions of space/place; interspecies/multispecies relationships; borderlands and frontiers; Caribbean; Latin America; islands. So, a lot of these recs are focused there. But someone else would have better recs, especially depending on your interests. For example, Chakrabarti writes about history of medicine/healthcare. Paravisini-Gebert about extinction and Caribbean relationship to animals/landscape. Deb Roy focuses on insects and colonial administration in South Asia. Some scholars focus on the historiography and chronological trajectory of “modernity” or “botany” or “universities/academia,”, while some focus on Early Modern Spain or Victorian Britain or twentieth-century United States by region. With so much to cover, that’s why I’d recommend the articles above, since they’re kinda like overviews.Generally I read more from articles, essays, and anthologies, rather than full-length books.

Some other nice articles:

(On my blog, I’ve got excerpts from all of these articles/essays, if you want to search for or read them.)

Katherine McKittrick. “Dear April: The Aesthetics of Black Miscellanea.” Antipode. First published September 2021.

Katherine McKittrick. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe. 2013.

Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” A chapter in: Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. 2004.

Kathleen Susan Murphy. “A Slaving Surgeon’s Collection: The Pursuit of Natural History through the British Slave Trade to Spanish America.” 2019. And also: “The Slave Trade and Natural Science.” In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History. 2016.

Timothy J. Yamamura. “Fictions of Science, American Orientalism, and the Alien/Asian of Percival Lowell.” 2017.

Elizabeth Bentley. “Between Extinction and Dispossession: A Rhetorical Historiography of the Last Palestinian Crocodile (1870-1935).” 2021.

Pratik Chakrabarti. “Gondwana and the Politics of Deep Past.” Past & Present 242:1. 2019.

Jonathan Saha. “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017.

Zoe Chadwick. “Perilous plants, botanical monsters, and (reverse) imperialism in fin-de-siecle literature.” The Victorianist: BAVS Postgraduates. 2017.

Dante Furioso: “Sanitary Imperialism.” Jeremy Lee Wolin: “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.” Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” Andrew Herscher and Ana Maria Leon. “At the Border of Decolonization.” All from e-flux.

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. 2 October 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “Introduction: Nonhuman Empires.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (1). May 2015.

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017).

Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner. “Monster as Medium: Experiments in Perception in Early Modern Science and Film.” e-flux. March 2021.

Lesley Green. “The Changing of the Gods of Reason: Cecil John Rhodes, Karoo Fracking, and the Decolonizing of the Anthropocene.” e-flux Journal Issue #65. May 2015.

Martin Mahony. “The Enemy is Nature: Military Machines and Technological Bricolage in Britain’s ‘Great Agricultural Experiment.’“ Environment and Society Portal, Arcadia. Spring 2021.

Anna Boswell. “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” 2018. And; “Climates of Change: A Tuatara’s-Eye View.”2020. And: “Settler Sanctuaries and the Stoat-Free State." 2017.

Katherine Arnold. “Hydnora Africana: The ‘Hieroglyphic Key’ to Plant Parasitism.” Journal of the History of Ideas - JHI Blog - Dispatches from the Archives. 21 July 2021.

Helen F. Wilson. “Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes.” Environment and Planning. July 2019.

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Kirsten Greer. “Zoogeography and imperial defence: Tracing the contours of the Neactic region in the temperate North Atlantic, 1838-1880s.” Geoforum Volume 65. October 2015. And: “Geopolitics and the Avian Imperial Archive: The Zoogeography of Region-Making in the Nineteenth-Century British Mediterranean.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2013,

Marco Chivalan Carrillo and Silvia Posocco. “Against Extraction in Guatemala: Multispecies Strategies in Vampiric Times.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. April 2020.

Laura Rademaker. “60,000 years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

Paulo Tavares. “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazon’s Deep History.” Architecture in the Anthropocene. Edited by Etienne Turpin. 2013.

Kathryn Yusoff. “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time.” Social Text. 2019. And: “The Anthropocene and Geographies of Geopower.” Handbook on the Geographies of Power. 2018. And: “Climates of sight: Mistaken visbilities, mirages and ‘seeing beyond’ in Antarctica.” In: High Places: Cultural Geographies of Mountains, Ice and Science. 2008. And:“Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene.” 2017. And: “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” 2017.

Mara Dicenta. “The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego.” Arcadia. Spring 2020.

And then here are some books:

Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500-1850 (Cameron B. Strang); Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Londa Schiebinger, 2004);

Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Helen Tilley, 2011); Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (Jonathan Saha); Fluid Geographies: Water, Science and Settler Colonialism in New Mexico (K. Maria D. Lane, 2024); Geopolitics, Culture, and the Scientific Imaginary in Latin America (Edited by del Pilar Blanco and Page, 2020)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten A. Greer); The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity (Hawthorne and Lewis, 2022); Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (Britt Rusert, 2017)

The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge (Arndt Brendecke, 2016); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013); Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands (Andrew Stuhl)

Anglo-European Science and the Rhetoric of Empire: Malaria, Opium, and British Rule in India, 1756-1895 (Paul Winther); Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); Practical Matter: Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687-1851 (Margaret Jacob and Larry Stewart)

Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2014); Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884-1905 (Matthew Unangst, 2022);

The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa (Bernhard Gissibl, 2019); Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century (Edited by Adriana Craciun and Mary Terrall, 2019)

The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022); Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Allison Bigelow, 2020); The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods); American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Megan Raby, 2017); Producing Mayaland: Colonial Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism (Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, 2023); Unnsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

Domingos Alvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (James Sweet, 2011); A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Anya Zilberstein, 2016); Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines (Sarah Steinbock-Pratt, 2019); Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea, 1800-1970 (Edited by Anderson, Rozwadowski, et al, 2016)

Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Maile Arvin); Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (Janet Dorothy Larkin, 2018); A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (Michael A. Verney, 2022)

Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Daniela Cleichmar, 2012); Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India (Arnab Dey, 2022); Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopoeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Edited by Crawford and Gabriel, 2019)

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment (Hi’ilei Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart, 2022); In Asian Waters: Oceanic Worlds from Yemen to Yokkohama (Eric Tagliacozzo); Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017); Turning Land into Capital: Development and Dispossession in the Mekong Region (Edited by Hirsch, et al, 2022); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski); Colonial Fantasies, Imperial Realities: Race Science and the Making of Polishness on the Fringes of the German Empire, 1840-1920 (Lenny A. Urena Valerio); Against the Map: The Politics of Geography in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Adam Sills, 2021)

Under Osman’s Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail, 2017); Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Jim Endersby); Proving Grounds: Militarized Landscapes, Weapons Testing, and the Environmental Impact of U.S. Bases (Edited by Edwin Martini, 2015)

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Multiple authors, 2007); Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Peter Redfield); Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Andrew Togert, 2015); Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of ‘Green’ Capitalism (Hannah Holleman, 2016); Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and the Reordering of Biodiversity Governance (Katja Grotzner Neves, 2019)

Botanical Entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England (Anna K. Sagal, 2022); The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Harriet Ritvo); Rubber and the Making of Vietnam: An Ecological History, 1897-1975 (Michitake Aso); A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Kathryn Yusoff, 2018); Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt (Jessica Barnes, 2023); No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers); Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1768-1941 (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017); Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia (Douglas C. Harris, 2001); Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep Time (Edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Jakelin Troy)

Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Joyce Chaplin, 2001); Mapping the Amazon: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 (Jeremy Zallen); Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Erik Linstrum, 2016); Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Water (James Pettifer and Mirancda Vickers, 2021); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti); Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea (David Fedman)

Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Julie Cruikshank); The Fishmeal Revolution: The Industrialization of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem (Kristin A. Wintersteen, 2021); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); An Imperial Disaster: The Bengal Cyclone of 1876 (Benjamin Kingsbury, 2018); Geographies of City Science: Urban Life and Origin Debates in Late Victorian Dublin (Tanya O’Sullivan, 2019)

American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (John Krige, 2006); Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Ann Laura Stoler, 2002); Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire (Faisal H. Husain, 2021)

The Sanitation of Brazil: Nation, State, and Public Health, 1889-1930 (Gilberto Hochman, 2016); The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia (James Hevia); Japan’s Empire of Birds: Aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and Transwar Ornithology (Annika A. Culver, 2022)

Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation (Jose E. Martinez, 2021); Sound Relations: Native Ways of Doing Music History in Alaska (Jessica Bissette Perea, 2021); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Andrew Zimmerman, 2001)

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Multiple authors, 2016); The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (Katherine Johnston, 2022); Seeking the American Tropics: South Florida’s Early Naturalists (James A. Kushlan, 2020)

The Colonial Life of Pharmaceuticals: Medicines and Modernity in Vietnam (Laurence Monnais); Quinoa: Food Politics and Agrarian Life in the Andean Highlands (Linda J. Seligmann, 2023) ; Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, 2017); Spawning Modern Fish: Transnational Comparison in the Making of Japanese Salmon (Heather Ann Swanson, 2022); Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Mark Bassin, 2000); The Usufructuary Ethos: Power, Politics, and Environment in the Long Eighteenth Century (Erin Drew, 2022)

Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures (Anita Mannur, 2022); On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, 1830-1890 (Philip Gooding, 2022); All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation Through Species Acclimitization, from Colonial Australia to the World (Pete Minard, 2019)

Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Setller Colonialism (Jarrod Hore, 2022); Timber and Forestry in Qing China: Sustaining the Market (Meng Zhang, 2021); The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (David A. Chang);

Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (Christine Keiner); Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire (Mauro Jose Caraccioli); Two Years below the Horn: Operation Tabarin, Field Science, and Antarctic Sovereignty, 1944-1946 (Andrew Taylor, 2017); Mapping Water in Dominica: Enslavement and Environment under Colonialism (Mark W. Hauser, 2021)

To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire (Jason Smith, 2018); Fir and Empire: The Transformation of Forests in Early Modern China (Ian Matthew Miller, 2020); Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500-1950 (Sandra Swart and Greg Bankoff, 2007)

Science on the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya (Lachlan Fleetwood, 2022); Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i (John Ryan Fisher, 2017); Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

An Ecology of Knowledges: Fear, Love, and Technoscience in Guatemalan Forest Conservation (Micha Rahder, 2020); Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Debjani Bhattacharyya, 2018); Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka); Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity (Ann Elias, 2019); Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (Angela Thompsell, 2015)

#multispecies#ecologies#tidalectics#geographic imaginaries#book recommendations#reading recommendations#reading list#my writing i guess

426 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, Mr. Haitch

You mentioned before in one of your answers that "climate and social justice are inextricably linked." Do you mind saying how so?

Thank you!

Our current geological age - the Anthropocene - is inextricably linked to the history of capitalism, no matter how you date it. The three main theories are that it began in 1945 at the close of the second world war and the international trade agreements and advent of nuclear testing; that it began with the industrial revolution; or (and this is the theory I subscribe to) it began between 1492 and 1610 with European colonialism in the Americas.

The anthropocene is defined as an age of globalised human control and impact on the earth's environment, ranging from climate change to biodiversity, and the early history of Europe's colonisation of the Americas fits the bill pretty well. Beginning in 1492 the indigenous population of the Americas collapsed by 95% (population estimates run from 60 million to 120+, the loss represents about a 10% global population loss), along with vast amounts of infrastructure including cities, towns, trading outposts, road networks, irrigation systems, and so on - all in an area (especially equatorial America) where the local flora grows rapidly. The deaths of so many with so few colonisers to replace them saw a rapacious period of reforestation, creating a massive carbon sink which drew down an estimated 13 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, ushering in The Little Ice Age. Global temperatures fell for the first time since the agricultural revolution, and put huge stress on an already fracturing feudal system. Over the course of 200 years Europe went through fits of social and political revolution, where the aristocracy were (sometimes violently) deposed by an ascendant merchant class ushering in our current age of liberal democracy, the enshrining of private property, and fixation on trade and prosperity.

The population collapse also provided a rationale for the Atlantic slave trade, as the enslaved workforce the Europeans had been using up until then were pretty much all dead.

With me so far?

Since the industrial revolution our economic system has been reliant on exponential growth, leading to an ever increasing appetite for raw materials, land, and cheap (or free) labour. The environmental and human costs have increased in lock step with one another - both crises borne of the same root. We cannot address one without addressing the other.

This is a very condensed version of the argument and I'm glossing over a lot here. If you're interested I'd recommend tracking down the following texts (usually available at libraries, particularly University ones):

The American Holocaust, David Stannard

The Human Planet, Lewis and Maslin

The Problem of Nature, David Arnold

The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert

History and Human Nature, RC Solomon

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

France, America and the Love for 'Liberté'

Warning: wall of text. This post is nearly 5000 words long.

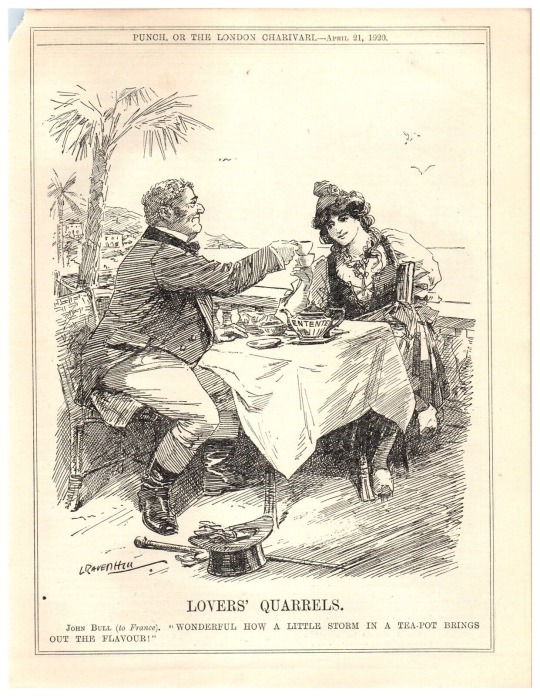

TL; DR: France contributed to the formation of America. Why did Himaruya design France like that? Some relevant information about the relationship between France - UK and France - US.

Part 1: The Love for 'Liberté'

I've talked about this a lot, but now I'll summarize it a bit. Basically, it's not without reason that I assume that France played a huge role in giving birth to America.

The reason the French supported America in the war for independence from Britain included 2 reasons:

1. Competition with England. This is too obvious.

2. The French Enlightenment caused the French to risk their lives in North America. Their help to Americans is to realize their dreams and ideals of liberty and republican government. (Museum of the American Revolution, unknown)

Helping America is not only the French monarchy, but also the French people. The Americans' determination to make a revolution created a great wave throughout France (Office of the Historian, unknown). It can be said that America was born from the French Enlightenment movement. Americans were directly taught by the French about ideas about human equality. At the heart of every American uprising is Enlightenment thought. In addition, precisely because Enlightenment ideas were transmitted directly from France to America, it was from America that this idea was spread across the Atlantic (Marks, 2018).

We can mention some typical French figures who participated in the American Revolution and some Americans who were influenced by France. The most famous Frenchman of the American Revolution was the Marquis de Lafayette. He joined this war at the age of 19, with the belief that he would bring glory and justice to America, even rising to the rank of major general in American army (Shaw, unknown). Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the designer of Washington DC, was French (Museum of the American Revolution, unknown). Thomas Jefferson, America's founding father, a native of England, was a true francophile. He was one of the first US ambassadors extraordinary and plenipotentiary to France, and is extremely passionate about the French lifestyle (The French Life, unknown). Benjamin Franklin was the main factor why the French were inspired and fervently supported the American Revolution (Office of the Historian, unknown). “Give me liberty or give me death!”, Patrick Henry's declaration at the Second Virginia Convention (1775) was influenced by the saying "Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” by French writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Mcgee, 2020)

The American Revolution is called the Second Hundred Years' War between France and England by some historians (Shaw, unknown). From 1775 to 1777, France secretly supported America by providing weapons and money to America (The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, unknown). When the Franco-American Alliance was signed in 1778, France openly supported the United States, and "brought its full military might against Britain" (Shaw, unknown). In terms of the treaty, “peace could be arrived at only by mutual French and U.S. consent" (The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, unknown). The British attempted to divide the French-American alliance and failed, and only when Britain and France resolved their differences could the Americans sign the treaty of Paris (Mcgee, 2020). French support played an important role in the British surrender at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781 (Office of the Historian, unknown). In the Siege of Yorktown painting hung in the US Capitol, the Bourbon flag and the American flag are placed parallel to each other. Admiring the French was even considered “a patriotic duty” for American colonists (Kaplan, 1956, p.34).

In order for America to be independent, the French army at that time gathered troops to fight the British army in colonies around the world. Because Britain had to spread human resources and resources across battles in other colonies, America became a secondary problem, meaning that if Britain did not let go of the 13 colonies in North America, the entire British empire would collapse. (Shaw, unknown). In 1776, France transferred to the United States about 300,000 pounds of gunpowder, 30,000 muskets, 3,000 tents, more than 200 cannons and clothes for 30,000 soldiers (Museum at Yorktown, unknown). If only before 1777, the amount of money that France provided to America was 1.3 billion livres, the American army was completely dependent on France. It was the 1778 treaty between America and France that gave the Americans legitimacy, thereby receiving additional support from other European powers. After that, 12,000 French soldiers, 22,000 naval personnel and over 63 warships participated in the war (Mcgee, 2020). In an unofficial source, meaning I read from a group of American friends, the statistics show that more French people died because of the American war of independence than Americans died because of their homeland (I haven't found an official source for this detail yet, so don't take it as fact. I would appreciate it if someone could fill me in on this detail). The costs were poured into North America causing France's economy to collapse and the French Revolution to occur, ending the French monarchy (Shaw, unknown). My opinion that France is a mother who sacrificed her life to give birth to her American child is not without basis.

After the defeat at Yorktown, when the British surrendered, they simply marched back toward the French, thereby denying the efforts and role of the Americans in this war of independence. French Major General de Lafayette was very angry, so he ordered his team to play Doodle Yankee (a song composed by the British to mock the French). Immediately, the British turned around and looked at the Americans. (Fleming, 2013)

At this point I will stop talking about the American Revolution, let's talk about other factors throughout the diplomatic history between America and France:

- The relationship between these two countries is not always smooth, even quite contradictory, but it is a fact that France is the first and oldest ally of America and these two countries have never really conflict with each other.

- French historian Édouard de Laboulaye proposed the idea of gifting the Statue of Liberty to the United States in 1865 to commemorate 100 years of American independence from England (1865 was the year the United States abolished slavery). Then, sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi designed this statue. Journalist Joseph Pulitzer wrote: “It is not a gift from the millionaires of France to the millionaires of America, but a gift of the whole people of France to the whole people of America.” (Little, 2021)

- Many times America and France almost became enemies, but fate did not let these two countries stand on two different front lines. The most spectacular case of reversal is about New Orleans. After Thomas Jefferson became president, he wrote: “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three eighths of our territory must pass to market.” (Worsham, 2002). That is France, the country that controls all of Louisiana including New Orleans. However, no one expected that the United States only needed to buy the entire Louisiana region from France in 1803 and the problem would be solved. Sold by France to Louisiana, America doubled in size, giving America access to the world's largest inland waterways. Tim Marshall wrote that, thanks to this purchase, “the roadmap to American greatness flowed.” (Marshall, 2016) (I read this in Vietnamese translation, and I translated it into English. Therefore, the quote may not be very accurate. Reading this gave me goosebumps)

- In 1964-1966, conflicts between America and France increased. During these years, France has continuously made statements and policies contrary to US policies, causing America to continuously promote anti-French media. Regarding this move, the French president at that time said: "It is in the United States' interest to have by their side not a satellite, but an independent ally, always by their side in times of danger." (Journoud, 2011) (I read this in Vietnamese translation, and I translated it into English. Therefore, the quote may not be very accurate). In 1966, France withdrew from the NATO military command structure. The French President demanded that all NATO bases leave French territory. NATO headquarters has been moved from Paris to Brussels. (CVCE.eu, unknown)

Keep in mind that most of the sources I read are American and British. There is only one source I got from the French. This means there is no French agenda here.

Part 2: Why, Himaruya?

I will add a little information about the cold period between France and America. I will no longer talk about France and America from Hetalia's perspective, but about France and America in reality. The purpose of part 2 is to answer the question: why did Himaruya design France like that? In this section, I only speak about the knowledge I have gathered without citing sources. I'm too lazy to find the source for this knowledge. So it could be wrong. You can read to learn more for yourself.

Some information I summarized from the book "De Gaulle et le Vietnam" by Pierre Journoud, some information I collected from other articles (which I did not save). The book "De Gaulle et le Vietnam" is a massive work, and an attempt at reconciliation between France and Vietnam, which describes the process of French President de Gaulle from a colonialist to a supporter of Vietnam's independence. This is a book sponsored and published by the French Embassy in Vietnam and recommended by scholars in Vietnam.

Okay, now let's get to the main story:

In official Hetalia, author Himaruya tends to "deny" the character France. The reason is because this person is an international student in New York, so he is greatly influenced by the American perspective on France. A large portion of Americans think of France as a promiscuous, sex-addicted b*tch. Why? This has an unfortunate history. There are 3 factors:

1. World War II. Allied troops landed in France... you know, during wartime, hunger, there will inevitably be prostitution with soldiers to get food. At that time, prostitution was widespread and terrible. I read an article that said this: Anglo-American troops saw the liberation of Paris not only as a symbol of Europe's freedom from Germany, but also as "their entertainment playground". When American troops arrived at France's Petit Palais, the authorities also gave free condoms to American soldiers so they could go with prostitutes there. The impression of such a place of debauchery and prostitution left a very deep impression in the minds of the British and Americans about the image of France being associated with debauchery and prostitution.

But the fact that the Allied troops came to France and brought back to their country such a bad impression of women was not the end. That myth should have disappeared in 1 or 2 generations. Everything continues to the second problem I will talk about later.

2. Indochina War.

That's right, my country is involved. During the First Indochina War, France returned to Vietnam, but after the battle of Dien Bien Phu, it was defeated and withdrew. America jumped in with the anti-communist flag, with the goal of not letting communism encroach on even one inch of land in the world, because they think that if Vietnam becomes a socialist country, the domino effect will turn the entire Pacific Ocean into a communist ocean.

What is worth mentioning here is that, after the French were defeated in Vietnam, they learned from the experience that the Vietnamese people needed independence more than anything and that Vietnamese nationalism was very strong, so the war Indochina was fundamentally wrong from the start. After France had completely accepted that it had lost and was wrong in Vietnam, they saw America jumping into Vietnam as nothing more than a new form of colonialism, and the Republic of Vietnam as nothing more than an American puppet. So at that time, France looked down on the Republic of Vietnam very much, and even that look increased when Ngo Dinh Diem died. President de Gaulle, after France's defeat in Vietnam, began to be more aware of the so-called Vietnamese nationalism and sympathized with the government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. He has repeatedly advised American presidents that with this situation they will be completely defeated in Vietnam and they should withdraw soon. Kennedy listened but did not withdraw, Johnson showed open hostility towards de Gaulle, Nixon escalated the war to a terrible intensity.

Let's go back to the world war a bit. World War II N4zi Germany occupied France and established the French Vichy government. General de Gaulle could not accept the French Vichy government, so he went to England to gather French forces abroad and in the colonies to establish the France Libre government in exile. Winston Churchill absolutely liked Charles de Gaulle and supported France Libre a lot (Churchill himself was a Francophile), but Roosevelt hated de Gaulle very much, made things difficult for France Libre and even recognized the Vichy government, because Roosevelt felt de Gaulle's nationalism was too strong, and under de Gaulle's influence, France would not "listen to" America after the war ends (and indeed he was not wrong). Britain needed America to fight N4zi Germany, and always advocated peace with America, so Churchill was torn between Roosevelt and de Gaulle. De Gaulle was a proud man, so even though he sought refuge in England as an exile, de Gaulle did not accept Britain's excessive demands about future post-war France for aid in the present. As a result, Churchill and de Gaulle argued a lot, hurled the harshest words at each other, and even almost considered each other enemies even though the two sides were allies and France was more or less relying on Britain.

On one occasion, de Gaulle and Churchill argued with each other. When de Gaulle went back, people asked de Gaulle what he and Churchill had argued about, and de Gaulle said: I asked him, "who did you choose in the end?", then he replied, “between Europe and the ocean, I will always choose the ocean”, I had nothing more to say. When people asked Churchill, Churchill only sadly said that de Gaulle was just losing his temper and needed to cool his head.

America's attitude of rejecting France Libre continued until the communist movement in France grew strong (at that time, France was the place of the largest communist party in Europe) and attempted to overthrow France Vichy. America did not want communists to take power in France, so they reluctantly nodded and supported de Gaulle's France Libre. However, everything was still extremely forced, because the head of France Libre, de Gaulle, was only informed about the D-Day landings two days before. De Gaulle was extremely angry but could do nothing.

Through it all, de Gaulle seemed always to be wary of Anglo-Saxon circles. Since France gained independence, the policy of French president had always been to try not to depend on any country. He advocated for France to independently develop nuclear weapons, withdrew France from command of NATO, forced allied troops to withdraw from French soil, made peace with the Soviet Union, established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China and vetoed Britain's entry into the EU. America knew de Gaulle did not want to depend on America and this was a friction dating back to the World War.

Returning to the Indochina war and France's opposition to US intervention in Indochina. Through the experience of France's failure, de Gaulle saw very clearly that America would soon be bogged down and defeated in Vietnam. De Gaulle himself did not like the government of the Republic of Vietnam because the Republic of Vietnam was too dependent on the United States. At that time, France bluntly made statements that France did not support US intervention in Indochina, that everything was wrong (something very few capitalist governments dared to do at that time. And according to what I read, at that time about 60-80% of the overseas Vietnamese people there did not like the government of the Republic of Vietnam), and even withdrew France from SEATO, acting as an intermediary diplomatic channel with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. With de Gaulle's "separation" moves, America lost all patience. To America, France is like a crazy person who never listens to America's wishes. And America believed that France's actions were because France was bitter towards them because they had taken France's place in Indochina, and America also brought up the old story of de Gaulle and Rooselvelt during the World War, claiming that de Gaulle was really a exploitative and ungrateful for America's help, that Roosevelt did not misjudge back then.

America believed that France was a fool, out of date but always liked to criticize America, but America could not take any tough measures or boycott France. France is the gateway to Europe. At that time communism was strong, America could not take such risks. So America used the media. During Johnson's entire period, the media and news always smeared and ridiculed France (The "white flag" meme is one of them). The Republic of Vietnam at that time also had a case of young men attacking the French embassy and destroying the works left by France.

Of course, among the media measures back then was the myth of prostitutes from World War II. America had dug up the prostitution narrative (which I mentioned in part 1), promoting that sexualized agenda in our showbiz world (“Voulez vous coucher avec moi ce soir?” actually from an American movie, not French). Since then, this myth has spread throughout the world and is especially prevalent in Anglo-American and Anglo-Saxon circles.

3. There is one more factor but I haven't learned much about this case. That is a big part of what makes up this stereotype France = b*tch, which also comes from the feudal period of France. At that time, the case of nobility couples getting married but both having affairs and debauchery and luxury started from the French palace of Versailles. King Louis XIV was the reason for this. Louis XIV believed that when he promoted adultery among the nobility, everyone would turn to "fight" with each other, thus no longer having the mind to overthrow him, and his position would be more secure. And the consequences of that debauchery were very horrifying, it gave birth to a series of generations of philosophers and literati who were sick, dissatisfied, and immersed in pleasure, lasting from the feudal period, to the period of Enlightenment philosophy, the French Revolution, flared up again in the 70s and 80s and that disorder and sickness still affects France to this day.

Part 3: Some related information and personal opinions

I would like to add a little more of my thoughts: During World War 2, America was in a position to help France. Because if America had not jumped into the war, instead of the Allies liberating France, it would have been the French Communist Party that would have overthrown the f4scists. France was one of the European countries most sympathetic to the red wave, so much so that at that time the French Communist Party was the largest Communist Party in Europe. There were many famous French philosophers who are Marxist.

Roosevelt clearly considered ignoring France Libre to recognize the Vichy government if the French red wave was not so strong. So at that time, I think, sooner or later France would be able to overthrow the f4scists, but the problem was which side to overthrow, America jumping in was also partly to competed with the French Communist Party. Imagine America jumping in without time and the Communist Party taking power in France, I don't know how much the world situation would change after that.

General de Gaulle was almost obsessed with the saying "between Europe and the ocean, I will always choose the ocean". After he received that answer from Churchill, his attitude towards Britain almost completely changed.

Later, France turned to join hands with its old enemy aka Germany to establish the European Coal and Steel Community mainly to counterbalance the influence of Britain and America, even France was a direct veto country when Britain applied to enter the EEC. This was like a slap in the face of Britain. The British are still very tormented about this case, saying "I saved you from them, I emptied the treasury for you, but in the end you would rather go with them than with me.". But in fact, the fact that France established the EEC with Germany in the first place was due to Britain's previous answer. It's just that the British and American media, when mentioning the EEC and calling France ungrateful, often don't mention Churchill's quote.

When General de Gaulle came to England in exile, the reason General de Gaulle did not compromise with Britain's demands was because France was "too weak to bow" at that time. This sentence makes me think that France is too proud to be submissive or bow its head, when even in exile, France was still determined not to bow to England, and later they did not bow to America the way Britain had bowed to America for nearly a century. Thanks to that, compared to other European countries, France now has a certain independence and is not too dependent on the US, and for the US, France is a relatively "difficult" ally. This is an "ally", not a "junior" labeled an ally, not the type that obediently listens to the US. America was very bitter about this and cursed France for being ungrateful, France only replied: "It is in the United States' interest to have by their side not a satellite, but an independent ally, always by their side in times of danger."

To talk about Churchill's answer, in fact, Britain becoming dependent on America was a rather bitter process for the British empire.

After the end of WW2, it was America that broke Britain's imperial position. If you read about West Asia (also known as the Middle East), a large part of the West Asian conflict took place because the US took over all of Britain's interests in the oil issue in West Asia.

A little background: The essence of the British empire and colonial system was market protection. That means the market between the mother country and the colony is a closed market, the goods of the mother country and the colony will be exported and consumed with each other, but will not export or import additional goods from a third country.

There is a saying that in WW2, the Allies won thanks to "Russian blood, British intelligence and American steel". That means World War II was won thanks to a large amount of weapons produced in the US. During World War II, America gradually realized their production potential, they themselves did not expect they had such great production power. The problem was that after the war ended, they lost their trading market. Their production capacity was still so strong, but they did not know where to export their goods. So they turned their attention to the British colonies: at that time Britain was accounting for 25% of the world market.

25% of that market was monopolized by the UK. So how can the UK released 25% of that market? American answer: Breaking Britain's imperial position, breaking Britain's monopoly on exporting goods to the colonies. At that time, Britain was in debt of more than 200% of GDP, the treasury was completely exhausted, the country was in ruins and British colonies began to rebel. The UK was in a desperate situation. In the end, Britain had to bow to America, aka, from the empire on which the sun never sets came to the Commonwealth. Britain withdrew from that 25% market share, and the former British colonies were now encroached by the United States to gain market share. That's why Britain was so bitter when France created the ESEC/EEC. Because the position from an independent empire to becoming a subordinate of America was something the British were forced to do, not wanted.

Part of the reason why Britain can somewhat accept a junior partnership with the US is because America's leaders are all of British descent. During the American Revolution, even after the revolution was successful, Americans still honored their old "motherland". Why is that, because in fact the leaders of the uprising were all white people from England. England has a characteristic that in any colony that has white British people, the people of British descent in that place are treated well by the mother country. When Churchill told de Gaulle that he would rather choose the ocean than choose Europe, perhaps he himself had the thought that Britain would decline, but would rather be America's subordinate - where there are England's own white British descendants (so somehow England continues its glory) rather than being equals with European countries.

In Charles de Gaulle's War Memoirs, the author said this: before WW2, Berlin was getting stronger and the risk of Germany going to war was in sight, but London ignored Berlin because London wanted that when France and Germany went to war, France would depend on Britain.

That's why when WW2 happened, de Gaulle argued with Churchill a lot and refused to compromise because de Gaulle did not want to fall into the same situation as London thought before, which meant becoming a France dependent on Britain. This has led to the UK moving towards the US, aka a "globalized" UK, while France forms the ESEC/EEC with Germany so that Europe can counter the Anglo-Saxon world. And another point in current French politics is that now there is a large part of the French demanding Frexit, because French agriculture has been severely damaged by the EU.

In general, the more I read about the Anglo-French relationship, the more complicated it became. French assumed that WW2 happened partly because Britain deliberately made France dependent on Britain (I'm not saying that England actually thought that way. I mean that from the French perspective, they felt that way). Then, when things really happened like that, Britain exhausted its national treasury in WW2 (for France and for themselves). However, when questioned by de Gaulle, Churchill replied that Britain would always look to the ocean instead of choosing Europe. Because of receiving such an answer, France would rather establish an EEC with Germany than be pro-British after WW2. Then the British became angry with the EEC. Then Britain asked to join the EEC. France vetoed Britain many times. Britain joined the EU for a while then wanted to leave. Now some French people want to leave as well.

-

Oh, what a long story. I wonder how many people read this entire post. I'm from a country that's not France, England or America, so except for a bit of patriotism that I expressed in part 2, I think this is a perspective that isn't too biased towards either side. Personally, I love America very much, America is strong and brave, that's the truth. America's flaws are obvious, but its strengths are equally beautiful and shining. This is a country with many defects and advantages like any other country. So I don't agree with the way everyone antagonizes America as a villain.

Because more than half of this article is not properly sourced, but is written based on my memory and opinion, I welcome your additional comments and polite corrections. I would like to emphasize again, you should not refer to this post as "fact", always fact check everything in this post.

Thus, the relationship between America and France is more complicated than most people think. Not only England, France also contributed greatly to the birth and shaping of America. Through the above events, we can conclude that the American spirit of Liberty was completely inherited from France. France is the country that America (even if he wanted to) could never hate (and vice versa). Even if you don't look at it from the perspective of France being America's mother, it can at least be affirmed that France is America's "tutor". Without France, there would be no America today. America's existence is a continuation of England's ambition and an honoring dignity of France.

To conclude the post, I would like to mention that I once saw a Japanese artist post a tweet like this:

"I found out that Frank means 'free man'

So, from ancient times until now, he hasn't changed at all."

References:

CVCE.eu (unknown). France and NATO. 31/12/2023: https://www.cvce.eu/en/recherche/unit-content/-/unit/02bb76df-d066-4c08-a58a-d4686a3e68ff/c4bbe3c4-b6d7-406d-bb2b-607dbdf37207

Fleming, T. (2013). A short history of "Yankee Doodle". 31/12/2023: https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/12/short-history-yankee-doodle/

Journoud, P. (2011). De Gaulle et Vietnam. Éditions Tallandier.

Kaplan, L. S. (1956). The philosophes and the American Revolution. Social Science, 31(1), pp. 31-35. https://doi.org/10.2307/41884421

Little, B. (2021). Why the Statue of Liberty Almost Didn't Get Built. 31/12/2023: https://www.history.com/news/statue-of-liberty-funding-pulitzer

Marks, J. (2018). How Did the American Revolution Influence the French Revolution?. 31/12/2023: https://www.history.com/news/how-did-the-american-revolution-influence-the-french-revolution

Marshall, T. (2016). Prisoners of Geography. Elliott & Thompson.

Mcgee, S. (2020). 5 Ways the French Helped Win the American Revolution. 31/12/2023: https://www.history.com/news/american-revolution-french-role-help

Museum at Yorktown (unknown). How did the French Alliance help win American Independence?. 31/12/2023: https://www.jyfmuseums.org/learn/research-and-collections/essays/how-did-the-french-alliance-help-win-american-independence

Museum of the American Revolution (unknown). France and the American Revolution. 31/12/2023: https://www.amrevmuseum.org/france-and-the-american-revolution

Office of the Historian (unknown). French Alliance, French Assistance, and European Diplomacy during the American Revolution, 1778–1782. 31/12/2023: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/french-alliance#:~:text=Between%201778%20and%201782%20the,protected%20Washington's%20forces%20in%20Virginia

Shaw, T. (unknown). France in the American Revolution. 31/12/2023: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/france-american-revolution

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (unknown). Franco-American Alliance. 31/12/2023: https://www.britannica.com/event/Franco-American-Alliance

The French Life (unknown). Thomas Jefferson: Founding Father & Francophile. 31/12/2023: https://www.thefrenchlife.org/2017/10/11/famousfrancophile/

Worsham, J. (2002). Jefferson Looks Westward. 31/12/2023: https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/winter/jefferson-message.html

#fruk#aph france#aph fruk#aph england#hws fruk#hws france#hws england#ukfr#aph ukfr#hws ukfr#aph america#hws america

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last week, WABC AM 77 in New York announced that disgraced shock-jock relic and gushing Nazi fan Anthony Cumia had returned to the radio in our nation’s most cosmopolitan city. Two months into this second Trump administration, it was just the latest example of media corporations across the board scrambling to placate the president and assure his unappeasable, permanently aggrieved supporters that they are seen, loved, and appreciated. The Cumia news came alongside a Netflix announcement that it had signed a three-special deal with comic Tony Hinchcliffe, most famous for his gig at the Trump Madison Square Garden rally where he called Puerto Rico a “floating island of garbage.” The week before that, Shane Gillis hosted Saturday Night Live; in 2019, he’d been hired and fired by SNL’s producer Lorne Michaels before he’d even appeared in a sketch, as old podcasts surfaced where Gillis threw terms like “fucking chinks” and “white faggots” around. There’s nothing new in this embrace of right-wing troll comedy; it’s a throwback to the shock radio world where Trump began his media career 30 years ago. In those heady days of “just kidding” racism, Don Imus’s radio show was even simulcast on liberal MSNBC. Back then, Imus could call reporter Howard Kurtz a “boner-nosed…beanie-wearing Jew boy,” and sum up PBS’s White House correspondent Gwen Ifill’s gig thusly: “They let the cleaning lady cover the White House,” and still book Bill Clinton or John McCain. Howard Stern, meanwhile, platformed Klan members and played a racist holiday song called “N——- Claus.” Then as now, Trump used that kind of humor to advance his interests. As his Atlantic City casino empire collapsed, Trump went on Imus’s show to blame his failure on Native American–owned casinos, saying, “They don’t look like Indians to me.” Three decades later, he stopped his State of the Union address to call Senator Elizabeth Warren “Pocahontas.” The resurgence of troll comedy reflects the postelection trend of chasing MAGA followers as the pop-cult demographic du jour. Despite Trump’s nonexistent mandate and razor-thin popular-vote victory, The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times radically altered their editorial pages to avoid our vindictive president’s wrath and court his supporters—resulting in large-scale defections of subscribers. As the administration scours the halls of our federal government to remove any visible sign of diversity, MSNBC cleansed its prime-time lineup of non-white hosts—drawing outraged pushback from star anchor Rachel Maddow. The saddest grab for this imaginary MAGA cultural revolution has to be Amazon Prime promoting reruns of The Apprentice. Bezos and company have bet that the American people, after seeing the president all day on the news and reading his daily Truth Social micro-manifestos, will want to relax at day’s end binge-watching his old “reality-TV” show late into the night. So far, the marketing strategy of pandering to Trump and his liberal-media-hating base has not helped said liberal media much. It’s cost them subscribers and traffic, and left the erstwhile resistance-branded team at MSNBC starved for ratings. All of these media decision-makers have misread Trump’s 312–226 Electoral College win as a national vibe shift rather than the meager popular win that it was. The audience hasn’t changed—there’s no red wave remaking the basic contours of media programming. Nevertheless, MAGA appeasement lumbers on. California Governor Gavin Newsom fell for it, launching a new podcast this month with hardcore MAGA guests like Charlie Kirk and Steve Bannon. It blew up on him—not in terms of ratings, mind you, more in the fashion of a Musk-designed SpaceX launch.

continue reading

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haitian Immigration : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Many Haitians moved to Louisiana during and after the Haitian Revolution, which began in 1791 and lasted for 13 years:

The long, interwoven history of Haiti and the United States began on the last day of 1698, when French explorer Sieur d'Iberville set out from the island of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) to establish a settlement at Biloxi, on the Gulf Coast of France's Louisiana possession.

For most of the eighteenth century, however, only a few African migrants settled there. But between the 1790s and 1809, large numbers of Haitians of African descent migrated to Louisiana. By 1791 the Haitian Revolution was under way. It would continue for thirteen years, result in the independence of the first African republic in the Western Hemisphere, and reverberate throughout the Atlantic world. Its impact would be particularly felt in Louisiana, the destination of thousands of refugees from the island's turmoil. Their activism had profound repercussions on the politics, the culture, the religion, and the racial climate of the state.

From Saint Domingue to Louisiana

Louisiana and her Caribbean parent colony developed intimate links during the eighteenth century, centered on maritime trade, the exchange of capital and information, and the migration of colonists. From such beginnings, Haitians exerted a profound influence on Louisiana's politics, people, religion, and culture. The colony's officials, responding to anti-slavery plots and uprisings on the island, banned the entry of enslaved Saint Domingans in 1763. Their rebellious actions would continue to impact upon Louisiana's slave trade and immigration policies throughout the age of the American and French revolutions.

These two democratic struggles struck fear in the hearts of the Spaniards, who governed Louisiana from 1763 to 1800. They suppressed what they saw as seditious activities and banned subversive materials in a futile attempt to isolate their colony from the spread of democratic revolution. In May 1790 a royal decree prohibited the entry of blacks - enslaved and free - from the French West Indies. A year later, the Haitian Revolution started.

The revolution in Saint Domingue unleashed a massive multiracial exodus: the French fled with the bondspeople they managed to keep; so did numerous free people of color, some of whom were slaveholders themselves. In addition, in 1793, a catastrophic fire destroyed two-thirds of the principal city, Cap Français (present-day Cap Haïtien), and nearly ten thousand people left the island for good. In the ensuing decades of revolution, foreign invasion, and civil war, thousands more fled the turmoil. Many moved eastward to Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) or to nearby Caribbean islands. Large numbers of immigrants, black and white, found shelter in North America, notably in New York, Baltimore (fifty-three ships landed there in July 1793), Philadelphia, Norfolk, Charleston, and Savannah, as well as in Spanish Florida. Nowhere on the continent, however, did the refugee movement exert as profound an influence as in southern Louisiana.

Between 1791 and 1803, thirteen hundred refugees arrived in New Orleans. The authorities were concerned that some had come with "seditious" ideas. In the spring of 1795, Pointe Coupée was the scene of an attempted insurrection during which planters' homes were burned down. Following the incident, a free émigré from Saint Domingue, Louis Benoit, accused of being "very imbued with the revolutionary maxims which have devastated the said colony" was banished. The failed uprising caused planter Joseph Pontalba to take "heed of the dreadful calamities of Saint Domingue, and of the germ of revolt only too widespread among our slaves." Continued unrest in Pointe Coupée and on the German Coast contributed to a decision to shut down the entire slave trade in the spring of 1796.

In 1800 Louisiana officials debated reopening it, but they agreed that Saint Domingue blacks would be barred from entry. They also noted the presence of black and white insurgents from the French West Indies who were "propagating dangerous doctrines among our Negroes." Their slaves seemed more "insolent," "ungovernable," and "insubordinate" than they had just five years before.

That same year, Spain ceded Louisiana back to France, and planters continued to live in fear of revolts. After future emperor Napoleon Bonaparte sold the colony to the United States in 1803 because his disastrous expedition against Saint Domingue had stretched his finances and military too thin, events in the island loomed even larger in Louisiana.

The Black Republic and Louisiana

In January 1804, an event of enormous importance shook the world of the enslaved and their owners. The black revolutionaries, who had been fighting for a dozen years, crushed Napoleon's 60,000 men-army - which counted mercenaries from all over Europe - and proclaimed the nation of Haiti (the original Indian name of the island), the second independent nation in the Western Hemisphere and the world's first black-led republic. The impact of this victory of unarmed slaves against their oppressors was felt throughout the slave societies. In Louisiana, it sparked a confrontation at Bayou La Fourche. According to white residents, twelve Haitians from a passing vessel threatened them "with many insulting and menacing expressions" and "spoke of eating human flesh and in general demonstrated great Savageness of character, boasting of what they had seen and done in the horrors of St. Domingo [Saint Domingue]."

The slaveholders' anxieties increased and inspired a new series of statutes to isolate Louisiana from the spread of revolution. The ban on West Indian bondspeople continued and in June 1806 the territorial legislature barred the entry from the French Caribbean of free black males over the age of fourteen. A year later, the prohibition was extended: all free black adult males were excluded, regardless of their nationality. Severe punishments, including enslavement, accompanied the new laws.

However, American efforts to prevent the entry of Haitian immigrants proved even less successful than those of the French and the Spanish. Indeed, the number of immigrants skyrocketed between May 1809 and June 1810, when Spanish authorities expelled thousands of Haitians from Cuba, where they had taken refuge several years earlier. In the wake of this action, New Orleans' Creole whites overcame their chronic fears and clamored for the entry of the white refugees and their slaves. Their objective was to strengthen Louisiana's declining French-speaking community and offset Anglo-American influence. The white Creoles felt that the increasing American presence posed a greater threat to their interests than a potentially dangerous class of enslaved West Indians.

American officials bowed to their pressure and reluctantly allowed white émigrés to enter the city with their slaves. At the same time, however, they attempted to halt the migration of free black refugees. Louisiana's territorial governor, William C. C. Claiborne, firmly enforced the ban on free black males. He advised the American consul in Santiago de Cuba:

Males above the age of fifteen, have . . . been ordered to depart. - I must request you, Sir, to make known this circumstance and also to discourage free people of colour of every description from emigrating to the Territory of Orleans; We have already a much greater proportion of that population than comports with the general Interest.

Claiborne and other officials labored in vain; the population of Afro-Creoles grew larger and even more assertive after the entry of the Haitian émigrés from Cuba, nearly 90 percent of whom settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population. Sixty-three percent of Crescent City inhabitants were now black. Among the nation's major cities only Charleston, with a 53 percent black majority, was comparable.

The multiracial refugee population settled in the French Quarter and the neighboring Faubourg Marigny district, and revitalized Creole culture and institutions. New Orleans acquired a reputation as the nation's "Creole Capital."

The rapid growth of the city's population of free persons of color strengthened the "three-caste" society - white, mixed, black - that had developed during the years of French and Spanish rule. This was quite different from the racial order prevailing in the rest of the United States, where attempts were made to confine all persons of African descent to a separate and inferior racial caste - a situation brought about by political reality in the South that promoted white unity across class lines and the immersion of all blacks into a single and subservient social caste.

In Louisiana, as lawmakers moved to suppress manumission and undermine the free black presence, the refugees dealt a serious blow to their efforts. In 1810 the city's French-speaking Creoles of African descent, reinforced by thousands of Haitian refugees, formed the basis for the emergence of one of the most advanced black communities in North America.

Soldiers, Rebels, and Pirates

Many Haitian black males eluded immigration authorities by slipping into the territory through Barataria, a coastal settlement just west of the Mississippi River. Some became allies of the notorious pirates Jean and Pierre Lafitte, white refugees of the Haitian Revolution. Surrounded by marshland and a maze of waterways, Barataria was an effective staging area for attacks on Gulf shipping. The interracial band of adventurers dominated the settlement's thriving black-market economy.

But pirates and smugglers did not make up the whole of Barataria's fugitive residents. Some two hundred free black veterans of the Haitian Revolution, including Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Savary, a former French republican officer, were among them. In 1799 seven hundred soldiers, opposed to Toussaint L'Ouverture fled to Cuba and later migrated to Louisiana. By 1810 this movement of Haitian soldiers from Cuba had created a black military presence in Louisiana that seriously worried Governor Claiborne. He anxiously requested reinforcements. The number of free black men "in and near New Orleans, capable of carrying arms," he wrote, "cannot be less than eight hundred."

Colonel Savary and other republican veterans of the Haitian Revolution remained committed to the French revolution's ideals of liberté, egalité, fraternité (freedom, equality, fraternity.) They regrouped to aid insurgents attempting to establish independent republics in Latin America. In November 1813 Savary offered to send five hundred Haitian soldiers to fight with Mexican revolutionaries. When their effort to establish a Mexican government in Texas failed, Savary and his men returned to New Orleans. Within the year, however, the colonel and other Haitian veterans would be rallying against the forces of the British crown.

As British forces threatened to invade New Orleans in 1814, American authorities sought to win the loyalty of battle-hardened black soldiers like Colonel Savary. They were also well aware of the prominent role that free men had played in slave rebellions. With the English approaching, pacifying them would be strategically sound.

General Andrew Jackson arrived in New Orleans in December 1814 and immediately mustered 350 native-born black veterans of the Spanish militia into the United States Army. Colonel Savary raised a second black unit of 250 of Haiti's refugee soldiers. Jackson recognized Savary's considerable influence and knew of his reputation as "a man of great courage." On Jackson's orders, Savary became the first African-American soldier to achieve the rank of second major.

The Haitians in Barataria also fought in the battle of New Orleans. In September 1814 federal troops invaded their community and dispersed the Lafittes and their followers. Hundreds of refugees poured into the city. Andrew Jackson offered them pardons in return for their support in defending the city. After the victory, he commended the two battalions of six hundred African-American and Haitian soldiers whose presence in a force of three thousand men had proved decisive. He praised the "privateers and gentlemen" of Barataria who "through their loyalty and courage, redeemed [their] pledge . . . to defend the country."