#abolitionist social work

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Speaking Against Silence: Examining Social Work’s Response to Genocide

Journal article in Abolitionist Perspectives in Social Work written by Brianna Suslovic (University of Chicago), Cameron Rasmussen (Columbia University), Mimi E. Kim (California State University Long Beach), Sophia P. Sarantakos (University of Denver), Alan J. Dettlaff (University of Houston), Christina Roe (Network to Advance Abolitionist Social Work), Vivianne Guevara (Columbia University).…

View On WordPress

#abolition#abolitionist social work#genocide#liberation#oppression#Palestine#reading#social work#the palestniana exception

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’ll never forget when I was arguing with a person in favor of total prison abolition and I asked them “what about violent offenders?” And they said “Well, in a world where prisons have been abolished, we’ll have leveled the playing field and everyone will have their basic needs met, and crime won’t be as much of an issue.” And then I was like “okay. But…no. Because rich people also rape and murder, so it isn’t just a poor person thing. So what will we do about that?” And I don’t think they answered me after that. I’m ashamed to say I continued to think that the problem was that I simply didn’t understand prison abolitionists enough and that their point was right in front of me, and it would click once I finally let myself understand it. It took me a long time to realize that if something is going to make sense, it needs to make sense. If you want to turn theory into Praxis (I’m using that word right don’t correct me I’ll vomit) everyone needs to be on board, which mean it all needs to click and it needs to click fast and fucking clear. You need to turn a complex idea into something both digestible and flexible enough to be expanded upon. Every time I ask a prison abolitionist what they actually intend to do about violent crime, I get directed to a summer reading list and a BreadTuber. It’s like a sleight-of-hand trick. Where’s the answer to my question. There it is. No wait, there it is. It’s under this cup. No it isn’t. “There’s theory that can explain this better than I can.” As if most theory isn’t just a collection of essays meant to be absorbed and discussed by academics, not the average skeptic. “Read this book.” And the book won’t even answer the question. The book tells you to go ask someone else. “Oh, watch this so-and-so, she totally explains it better than me.” Why can’t you explain it at all? Why did you even bring it up if you were going to point me to someone else to give me the basics that you should probably already know? Maybe I’m just one of those crazy people who thinks that some people need to be kept away from the public for everyone’s good. Maybe that just makes me insane. Maybe not believing that pervasive systemic misogyny could be solved with a UBI and a prayer circle makes me a bad guy. But it’s not like women’s safety is a priority anyway. It’s not like there is an objective claim to be made that re-releasing violent offenders or simply not locking them up is deadly.

#I’m sorry#there are just people out here who need punishment and to be contained and rehabilitation will not work#like I’m one of the more insane people who thinks that you can rehabilitate anyone if they want to change and learn from their behavior#ANYONE#but there are people out here who do not and will not ever want it#and those people shouldn’t get a pass because you read incomplete abolitionist theory once#and now you think that a UBI would solve everything#that’s the thing about most abolitionists that I’ve noticed#once you press them on the hard shit#they go#well there are some good books on the subject#there are some other creators#okay#and what have those other books and creators said?#Tee Noir once started off a video telling people not to ask her to defend her defense of prison abolition#they should just ‘Google it’ she said (or something like that)#now I don’t watch Tee Noir#gothra#feminism#social justice#prison abolition#criminal justice#prison reform#tw vomit

939 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seriously, people who complain about any vaguely liberal idea as socialist have no idea how many of the rights they like and take for granted were won by socialists, abolitionists, suffragettes, black liberationists, and other radicals.

#politics#us politics#progressive#socialism#socialist#radicalism#radical#labor rights#worker rights#working class#conservativism#black power#black liberation#women's suffrage#abolitionist

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

can you explain family abolition in a few words?

sure. there is no one unitary 'family abolitionist' perspective so be aware that i'm explaining this as a marxist and not as an anarchist or a radical feminist.

basically, "the family" is a social construct rather than a fixed self-evident truth. the family has been created and can be shaped, altered, or--indeed--abolished. this is evinced by the broad anthropological and historical record of radical transformations in what constitutes 'the family' (cf. clans, the extended family, the nuclear family). viewing the family as such opens it up to critique and also to the concept that it could be replaced with something better (in much the same way that, for communist and anarchist, refusing to accept the timelessness / naturalization of the bourgeois state opens up new horizons of political thought outside of engagement with electoral politics.)

among these critiques of the family are:

that it is a tool of patriarchal control over women and children by creating an economic dependence upon spouses / parents

ergo, that it enables and causes 'abuse' -- that child abuse, spousal abuse, and intimate partner violence are not abberations of 'the family' but in fact a natural consequence of its base premises re: power and control

that it serves as a site of invisiblised economic labour (e.g. housework)

that it is a tool of the capitalist (formerly the feudal) economy's reproduction of inequality via e.g. inheritance laws

that it serves as a site of normalization and reproduction of hegemonic ideology--i.e. that it is the site where heteronormativity, cisnormativity, gender roles, class positionality, & more are ingrained in children

among solutions family abolitionists propose to remedy it are:

the total dissolution of any legal privilege conferred by romantic or blood relationship in favour of total freedom for any group of people to form a household and cohabitate

the recognition of housework, the work of childrearing, & the general tasks of social reproduction as 'real' labour to be distributed fairly and not according to formal or informal (feminized) hierarchies

the economic and legal freedom of children--(i.e., allowing children unconditional access to food and shelter outside 'the family', allowing children the legal right to informed consent and self-determination)

similarly, the emancipation of women from economic dependence on their partners--both of these can only really be achieved via socialism (as marx put it, 'women in the workplace' only trade patriarchal dependence upon a husband for patriarchal dependence upon an employer)

communal caretaking of children, the sick, & the elderly

yeah. i know. this is a lot of words. its not few words. sorry. it's a complex topic innit. this is a few words For Me consideri ng that i've got a long-ass google doc open where i'm writing up a whole damn essay on this exact topic.

tldr: the family is not inevitable, it is constructed & can be replaced with something better. full economic freedom from dependence on interpersonal familial relationships for everybody now. check out cuba's 2022 family code for an idea of what this could look like as practical legislation.

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

ok fine cis men aren't the bad gender it's all men and we're all exactly like that anon who admitted to having abused women even if we don't know it. are you fucking happy now? is this the solidarity you want us to feel with cis men, that we're all just as mich rapists and murderers of women as they are? you have some fucking nerve to be throwing vague jabs while calling an admitted abuser "brave"

Normally I don't platform asks like these, but I'm moved by the genuineness of your emotional reaction here. I think you're hurting, and you've been hurt, and that the belief that abuse and violence are located within one gendered group (to which you don't belong) has felt like a way of organizing your world that has helped you make sense of things, and given you guidelines for how to act and whom to trust that have helped keep you safe. I think a lot of assault survivors feel that way when they're not cis men and their attackers were cis men.

As someone who has experienced a ton of sexual predation at the hands of cis women, cis men, and even other trans people, I don't feel the same way. There is no "bad gender" I can chalk up my abuse to. I find there are no easy means of categorizing entire people as abuser or as victim either -- I have known so, so many people who have occupied both roles depending upon the power they wielded and the social context of the moment. Hell, one cis lesbian that I knew who was infamous in her community for raping trans men would always tell her victims that her acts were those of "trauma recovery," of her "reclaiming" her power after men had stolen it away.

Even she, I don't think, is irredeemable or ontologically evil.

I'm an abolitionist. That's a core value through which a lot of my political action and beliefs flow. If you're not on board with the project of abolitionism, you'll find much to object to here, and most of your objections are things I will refuse to entertain, because I do not believe human beings are disposable no matter what they do, and I don't believe that anyone should have the authority to deem another human being as disposable.

An abolitionist politics is incompatible with the idea that some people or some groups are inherently bad. It's incompatible with the belief that abuse and violence comes from evil. It's a worldview that holds that people do harm because of social structures and networks of power that must be destroyed -- systems like the patriarchy, cissexism, anti-Blackness, ableism, capitalism, and more. And I think one of the ways that we conquer such oppressive systems is by raising the consciousness of all the people trapped under it -- so that we can topple it together. I want trans men and cis men alike to realize they have some skin in the game.

You don't have to associate with the men you don't want to associate with. If, because of repeated abuses at the hands of men, you can't ever trust them, well, those are your feelings, that's your life, that is your business. But when your personal feelings of safety are used as a justification for developing and promoting a worldview with transphobic, transmisogynistic implications, I'm gonna talk shit about that on my stupid little blog. And I'm gonna continue conducting my life in the way I feel I should.

And for me, that means forging common ground between trans men and cis men, and pushing both groups to take women's concerns seriously (especially trans women's concerns) and to stop centering themselves in feminist dialogue. There's a place for both trans men and cis men in the gender revolution, but we gotta do a lot of work on ourselves to stop getting in the way. It's work I'm emotionally equipped to do and find rewarding, and it's fine if you don't. There are lots of other people who need support that you can focus your energies on -- other survivors of abuse and assault that you perhaps find it easier to relate to. That's important work too, and I wish you well in doing it. Just make sure you're not excluding trans women in that work or I'll continue to be annoying about it on my stupid little blog.

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

the liberal 'actually, it's impossible to tell whats good and bad, so you should never have any authority over anything' approach is, principally, ridiculous, but is also just incredibly weak as a defence.

whether abortion is good or actually murder is a pretty important thing to address: it's good. whether hrt is good or actually delusional self-harm is a pretty important thing to address: it's good. whether being gay is good or actually a sign of a sexual predator is a pretty important thing to address: it's good. in all these cases, going 'yeah, maybe abortion is murder, but it's my inalienable right to bodily autonomy, either way' is laughable. it wins over nobody who doesn't already think abortion isn't murder, and is based on a premise that we should already know is wrong: there are no such thing as universal human rights. all rights are socially-situated and conditional, and in fact, there are good times when 'bodily autonomy' should not be respected - I mean, for god's sake, we intend to kill people with guns.

we have to actually make value judgements and weigh the positives against the negatives for real, specific cases, not just pre-emptively refuse the question out of a solipsism and appeals to universal truths. forcing someone to give blood to save lives at a mass casualty event is more emotionally impactful, despite being identical to, mandating vaccination and handwashing. both of the latter are 'violations of bodily autonomy' that are plainly agreeable on practical grounds. the position that finds no possible way of extricating 'stopping someone from committing suicide', an act generally thanked after the fact, from the abuses that take place in capitalist psychiatric institutions, is not one based on material analysis or an attempt to mitigate harm - it is a juvenile 'abolitionist' approach that refuses to consider class character, in favour of an idealistic condemnation of entire systems and related practices in the abstract.

ultimately, there is nothing incorrect that is not also harmful. a refusal to analyse the positives and negatives of behaviours, procedures, and acts, justified by 'it's impossible to know!' and 'doing anything would be authoritarian!' is not helpful, does not bring about correct behaviour in practice, it is the opposite - it is a cover for harmful behaviours, and promoting it to avoid the hard discussions over whether a given behaviour is harmful is wrong. it fails to defend correct things - like the fact that hrt is good - and works to defend incorrect things. any view that our positions should not be based on practical, material facts is corrosive.

437 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. next time somebody wants to make fun of Foucault for saying schools are prisons just know this thread is full of teachers saying this sounds so great, they do the same kind of work and love it, or they "always wanted to work in a correctional facility" and will look into this line of work

2. slightly more sympathetically, this is a demonstration of the abolitionist argument that in a neoliberal carceral society, prisons become the only government institution that the state is willing to direct resources to, and so what should be generalized social service programs like mental health treatment or continuing education get hung on its framework like ornaments on a christmas tree. this is how you get proposals for new prisons that include things like community meeting rooms in the building, because no one will find a community center but they will fund "amenity designed to sell a prison to a community." that is 100% a big part of what these teachers are responding to: having actual resources and a system that doesn't expect them to be an entire family, community, supply closet, and institution in one human body. but like, how is your response "prison school rules!" rather than "hold the fuck up"

(of course there's some talk about learning about how the other half lives and not being so quick to judge etc etc but. come on)

171 notes

·

View notes

Note

so im going into therapy (or social work, more broadly) as a profession (in school rn). i know that not everyone in anti psych would support that, understandably, and im not under an illusion that therapy isnt tied to the whole system and process. but i want to bring a liberationist, anti-racist, pro-mad, and abolitionist ideology to help who i can

do you have any suggested resources or reading recommendations or idk any insight on how to inform the way i go about juggling anti psychiatry in a profession that is considered going hand in hand with it?

Hi anon.

I think there can be ways that people working in the psych system can leverage power and resources in a way where they're acting in solidarity with psych survivors and mad people, but in reality, this very rarely happens, even among professionals who identify as radical or as having lived experience.

Fundamentally, the psychiatric system is one that perpetuates structural violence, and in smaller and larger ways, anyone who works within the system to legitimize it contributes to and is complicit in that violence. So I think that for anyone who is planning to work within the system, you need to be upfront with yourself that there is harm occurring and that isn't something you can just ignore or act like that's something you're separate from. Even if you're not working inpatient or facilitating forced drugging of someone, there's still a lot of ways that therapists can be complicit in psychiatric violence.

One of the most obvious ways is through mandatory reporting. I believe that in order to be an ethical therapist you must break the law--mandatory reporting is a dangerous way that mad people are surveilled by the state, and therapists must work to interrupt that and prevent it. There are a lot of therapists out there already talking about practical ways to avoid mandatory reporting and how to be upfront with clients about it, and I can link some of that at the end of this post. I won't say it's always easy, but we have an obligation to each other to do everything we can to stop psych incarceration from happening.

I think there's a lot of ways that even outpatient, therapists are asked to enable other forms of psychiatric violence. Even if in your practice, you're really focusing on liberation, respecting autonomy, etc, there are ways that other psych professionals might try to get you to help them perpetuate different forms of harm. And because of your degree and licensure, there's this power imbalance between you and your client that means you do have the power to enable these kinds of harms. The degree next to your name means that you will always be believed over your client and that is a lot of power to hold. If you're working with a client with an eating disorder and their dietitian gives an ultimatum that they have to be hospitalized or they're refusing to provide care, what do you do? If your client's psychiatrist is refusing to answer questions or let them switch to other types of medications, what do you do? If your client is involved in a court case and you're getting subpoenaed for their medical records, what do you do? If your MSW program requires you to do one of your internships in an inpatient program, how do you prevent that from happening? There are a lot more examples I can think of, but these are just a few things I wanted to highlight for ways that therapy is still entangled in the larger system.

Another thing that feels important to me is to make the distinction between being a "good therapist" and helping people, because I don't think those things are the same. I see a lot of "radical" therapists get fixated on this idea that they need figure out ways to make the psych system run smoother, to improve access, to overall make the psych system better, and that this is the only way to help people. It's really important to be able to separate those ideas. For me, psych abolition is a project of building up our capacity to care for each other while destroying the systems that currently enact violence on us, and reformist ideas about expanding psychiatric systems, increasing funding, and legitimize psychiatric authority gets in the way of actually transforming care. I think in order to help people, you need to commit to being a "bad therapist" in the eyes of a capitalist healthcare system.

One recommendation I have is to read Franco Basaglia's writing and learn about his approach of the democratic psychiatry movement. As a psychiatrist, he saw his role as a way to disrupt the system and deinstitutionalize. He has this quote where he talks about how they weren't focused on eliminating problems, but rather on how deinstitutionalization would create more chaos and new problems--and how that created so much possibility for transformation. I think he's proof that there are certainly ways that psych professionals can act as accomplices who actually are in solidarity with psych survivors, but it's rare.

Last point I have is that although you gain something from professional training and licensure, there's also a lot you lose. MSW programs often don't actually teach you the skills you want to learn about how to actually support people--there's a lot you're going to have to learn from continuing education credits. From my friends who have gotten their MSW, I've heard a lot of complaints about how surface level a lot of information is, and also about how a lot of the way that information is taught reinforces hierarchal ideas and doesn't respect patient autonomy. I'll also say that gaining licensure oftentimes creates barriers for radical action--I've seen so many therapists who then become so attached to holding onto and not losing that licensure that they weigh it above mad people's lives. I've heard so many therapists say "Oh I can't speak up against restraint because I'll lose my job/I can't ignore mandatory reporting because I'll lose my license/etc etc etc." And I think that can be a really damaging mindset that harms your potential to actually help people. There are several therapists I know who are in the process of intentional de-licensure because of this, but regardless if you pursue that path or not, this is a mindset you need to be on guard against.

All that being said, I think there is a need for more abolitionist therapists who are able to help support our communities, both in terms of creating that space for individual support and on a collective level. There are ways that you can leverage your access to resources and the way you're seen as legitimate in the system to help advocate for people, get them support, and interfere with psych violence. I have a therapist comrade who keeps working in inpatient psychiatry specifically so that they can continue to sneak in banned materials to the ward, prevent illegal restraints, be involved in court proceedings as an advocate, connect people to mad liberation resources, let psych patients use their phone, document psychiatric abuse with the plan to fairly soon release that information as a whistleblower, and more that I'm not going to talk about publicly. They still grapple with the fact that they are currently perpetuating harm at the same time, but to them, it's worth it to be able to sabotage things in that way. And I think that there are ways that you can take the information you learn in your program that is actually useful and find ways to bring that directly to your communities, and that there is good you can. I just think you have to be very intentional and aware of what it takes to actually do that, rather than just staying complacent with the label of being a "radical therapist" without doing anything to make that true.

For resources--here's my psych abolition drive with a lot of different zines, books, workbooks on different psych abolition topics. I really would recommend reading Psychiatry Inside Out by Franco Basaglia as an example of successful psychiatric resistance.

I would also suggest checking out Mutual Aid/Self Social therapy--the people who created this project are trusted comrades of mine, have both gotten their MSW or LMFT, and they have a lot of helpful insight into how to navigate things like avoiding mandatory reporting, de-licensure, etc. They have a discord server and also have regular online MAST meetings to train people on what MAST is and how to set up a MAST collective.

Genuinely wishing you the best of luck through school and appreciate that you're actively thinking about these things.

#asks#psych abolition#recently i've seen a trend. mostly on instagram. of peopel who identify as radical or lived experience therapists still not getting it#or exploiting the work of mad people and acting like it's their own. or using their lived experience as a way to justify the harm that#they perpetuate. or just really not interrogating the hierachy and power imbalance. or really thinking hard enough about what is actually#going on#so this response might seem a bit frustrated but that anger is not directed straight at you anon

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

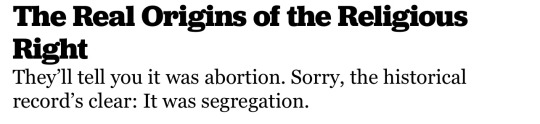

One of the most durable myths in recent history is that the religious right, the coalition of conservative evangelicals and fundamentalists, emerged as a political movement in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling legalizing abortion. The tale goes something like this: Evangelicals, who had been politically quiescent for decades, were so morally outraged by Roe that they resolved to organize in order to overturn it.

This myth of origins is oft repeated by the movement’s leaders. In his 2005 book, Jerry Falwell, the firebrand fundamentalist preacher, recounts his distress upon reading about the ruling in the Jan. 23, 1973, edition of the Lynchburg News: “I sat there staring at the Roe v. Wade story,” Falwell writes, “growing more and more fearful of the consequences of the Supreme Court’s act and wondering why so few voices had been raised against it.” Evangelicals, he decided, needed to organize.

Some of these anti- Roe crusaders even went so far as to call themselves “new abolitionists,” invoking their antebellum predecessors who had fought to eradicate slavery.

But the abortion myth quickly collapses under historical scrutiny. In fact, it wasn’t until 1979—a full six years after Roe—that evangelical leaders, at the behest of conservative activist Paul Weyrich, seized on abortion not for moral reasons, but as a rallying-cry to deny President Jimmy Carter a second term. Why? Because the anti-abortion crusade was more palatable than the religious right’s real motive: protecting segregated schools. So much for the new abolitionism.

Today, evangelicals make up the backbone of the pro-life movement, but it hasn’t always been so. Both before and for several years after Roe, evangelicals were overwhelmingly indifferent to the subject, which they considered a “Catholic issue.” In 1968, for instance, a symposium sponsored by the Christian Medical Society and Christianity Today, the flagship magazine of evangelicalism, refused to characterize abortion as sinful, citing “individual health, family welfare, and social responsibility” as justifications for ending a pregnancy. In 1971, delegates to the Southern Baptist Convention in St. Louis, Missouri, passed a resolution encouraging “Southern Baptists to work for legislation that will allow the possibility of abortion under such conditions as rape, incest, clear evidence of severe fetal deformity, and carefully ascertained evidence of the likelihood of damage to the emotional, mental, and physical health of the mother.” The convention, hardly a redoubt of liberal values, reaffirmed that position in 1974, one year after Roe, and again in 1976.

When the Roe decision was handed down, W. A. Criswell, the Southern Baptist Convention’s former president and pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas—also one of the most famous fundamentalists of the 20th century—was pleased: “I have always felt that it was only after a child was born and had a life separate from its mother that it became an individual person,” he said, “and it has always, therefore, seemed to me that what is best for the mother and for the future should be allowed.”

Although a few evangelical voices, including Christianity Today magazine, mildly criticized the ruling, the overwhelming response was silence, even approval. Baptists, in particular, applauded the decision as an appropriate articulation of the division between church and state, between personal morality and state regulation of individual behavior. “Religious liberty, human equality and justice are advanced by the Supreme Court abortion decision,” wrote W. Barry Garrett of Baptist Press.

So what then were the real origins of the religious right? It turns out that the movement can trace its political roots back to a court ruling, but not Roe v. Wade.

In May 1969, a group of African-American parents in Holmes County, Mississippi, sued the Treasury Department to prevent three new whites-only K-12 private academies from securing full tax-exempt status, arguing that their discriminatory policies prevented them from being considered “charitable” institutions. The schools had been founded in the mid-1960s in response to the desegregation of public schools set in motion by the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954. In 1969, the first year of desegregation, the number of white students enrolled in public schools in Holmes County dropped from 771 to 28; the following year, that number fell to zero.

In Green v. Kennedy (David Kennedy was secretary of the treasury at the time), decided in January 1970, the plaintiffs won a preliminary injunction, which denied the “segregation academies” tax-exempt status until further review. In the meantime, the government was solidifying its position on such schools. Later that year, President Richard Nixon ordered the Internal Revenue Service to enact a new policy denying tax exemptions to all segregated schools in the United States. Under the provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which forbade racial segregation and discrimination, discriminatory schools were not—by definition—“charitable” educational organizations, and therefore they had no claims to tax-exempt status; similarly, donations to such organizations would no longer qualify as tax-deductible contributions.

On June 30, 1971, the United States District Court for the District of Columbia issued its ruling in the case, now Green v. Connally (John Connally had replaced David Kennedy as secretary of the Treasury). The decision upheld the new IRS policy: “Under the Internal Revenue Code, properly construed, racially discriminatory private schools are not entitled to the Federal tax exemption provided for charitable, educational institutions, and persons making gifts to such schools are not entitled to the deductions provided in case of gifts to charitable, educational institutions.”

Paul Weyrich, the late religious conservative political activist and co-founder of the Heritage Foundation, saw his opening.

In the decades following World War II, evangelicals, especially white evangelicals in the North, had drifted toward the Republican Party—inclined in that direction by general Cold War anxieties, vestigial suspicions of Catholicism and well-known evangelist Billy Graham’s very public friendship with Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. Despite these predilections, though, evangelicals had largely stayed out of the political arena, at least in any organized way. If he could change that, Weyrich reasoned, their large numbers would constitute a formidable voting bloc—one that he could easily marshal behind conservative causes.

“The new political philosophy must be defined by us [conservatives] in moral terms, packaged in non-religious language, and propagated throughout the country by our new coalition,” Weyrich wrote in the mid-1970s. “When political power is achieved, the moral majority will have the opportunity to re-create this great nation.” Weyrich believed that the political possibilities of such a coalition were unlimited. “The leadership, moral philosophy, and workable vehicle are at hand just waiting to be blended and activated,” he wrote. “If the moral majority acts, results could well exceed our wildest dreams.”

But this hypothetical “moral majority” needed a catalyst—a standard around which to rally. For nearly two decades, Weyrich, by his own account, had been trying out different issues, hoping one might pique evangelical interest: pornography, prayer in schools, the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, even abortion. “I was trying to get these people interested in those issues and I utterly failed,” Weyrich recalled at a conference in 1990.

The Green v. Connally ruling provided a necessary first step: It captured the attention of evangelical leaders , especially as the IRS began sending questionnaires to church-related “segregation academies,” including Falwell’s own Lynchburg Christian School, inquiring about their racial policies. Falwell was furious. “In some states,” he famously complained, “It’s easier to open a massage parlor than a Christian school.”

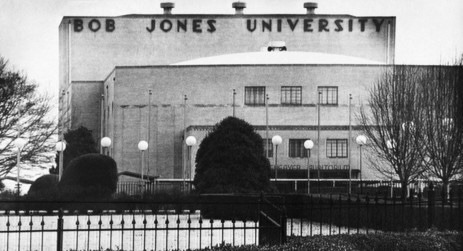

One such school, Bob Jones University—a fundamentalist college in Greenville, South Carolina—was especially obdurate. The IRS had sent its first letter to Bob Jones University in November 1970 to ascertain whether or not it discriminated on the basis of race. The school responded defiantly: It did not admit African Americans.

Although Bob Jones Jr., the school’s founder, argued that racial segregation was mandated by the Bible, Falwell and Weyrich quickly sought to shift the grounds of the debate, framing their opposition in terms of religious freedom rather than in defense of racial segregation. For decades, evangelical leaders had boasted that because their educational institutions accepted no federal money (except for, of course, not having to pay taxes) the government could not tell them how to run their shops—whom to hire or not, whom to admit or reject.

The Civil Rights Act, however, changed that calculus.

(continue reading)

#politics#republicans#paul weyrich#abortion#religious riech#bob jones university#jerry falwell#christian nationalism#white supremacy#desegregation#project 2025#roe v wade#reproductive rights#reproductive justice#healthcare#brown v board of education#heritage foundation#moral majority#religious freedom#religion

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've noticed that, in discussions of how to handle grevious harm and abuse at a community level, victims of harm who want to preserve their relationships with perpetrators to some degree are... discarded?

there's an automatic assumption in left and abolitionist circles that all victims of harm either currently hate and want to cut off the perpetrators of that harm, or are temporarily confused due to being emotionally victimized and dependent on the perpetrators but will eventually come around to wanting to cut them out of their lives.

and i do think we need to provide unilateral structural support for people who want to entirely remove perpetrators of harm from their lives--there's already many legal and financial barriers to that in the case of legally recognized family members, and many other barriers in the forms of financial and housing entanglements, and those require work and support to untangle and remove as barriers on a broad, societal level. simultaneously, though, i don't think it's necessary to discard victims with other relationships to perpetrators in the process, nor to dismiss them as not capable of having that autonomy, nor to pathologize their decisions.

i've found that often in left and abolitionist circles, if someone wants to maintain a relationship with someone who's deeply harmed them, there's suddenly just... a total lack of community support, and even a tendency to lump them in with the perpetrator of harm and implicitly frame them as not being a ~real~ victim, or at the very least one who is suspect because they must have agreed with the premise of the harm or thought it was excusable in some way. and like... socially ostracizing victims is socially ostracizing victims regardless of why you're doing it!

and there's a tendency to reach a social consensus somewhere along the lines of like... "i'll help you, but only if it doesn't help the person who harmed you/is harming you." which is all well and good until you realize that shuts down the very possibility of external supports in healing the relationship in question and preventing further harm/abuse. it implicitly places the full responsibility of supporting the perpetrator's journey to accountability and improving their actions on the victim, which i shouldn't need to say is both unhealthy and doomed to fail. furthermore, it places the victim in a vulnerable place socially--if they live with the perpetrator, can they ask for rental support or help with groceries, or will that be seen as helping the perpetrator? if the perpetrator has some sort of health crisis, can the victim reach out for support through it (housecleaning, cooking, medical bills), or are they on their own because they chose to maintain this relationship?

thinking about how many of my friends were able to reconcile with abusive parents as adults, due to the shift in power dynamics, and were actually able to hold their parents accountable for their past actions and demand change that has actually progressed and improved their relationship... and thinking about how many of them are implicitly treated like helpless idiots that cannot be trusted to make their own life decisions because of this, by people who are supposed to be in community with them and talk a big game about restorative justice and abolition.

807 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello again.

I just saw a very vaguely worded prison abolitionist post talking about how 'if you just make the system better, then the amount of people in jail would shrink' which A) feels rather reform-y for a post starting off talking about how no reform is possible, the system is a lost cause...and B) it feels that these people don't get that there are just assholes out there?

Because it goes on this long rant at the end talking about all the things in the system that would need to be fixed, like helping the homeless, having healthcare focused on the mentally ill, lifting up impoverished communities. And honestly, you know what, sure I approve of all of that...

But then the phrase "Next we tackle sexual assault" is uttered without any context or ideas of how to handle it. And I was like oh for fucks sake... Everything else in this post was like, here's the magic button on how to fix this but then SA is just dropped at the end.

I don't know why prison abolitionists lock up and get defensive when it comes to the question of "what about rapists?" but it seems as though they never fully take it seriously. And while I cannot speak to the full intricacies of the prison abolitionist movement, I'm only starting to be exposed because of someone on my dash I'm considering unfollowing, I can speak to statistics when it comes to sexual assault and incarceration.

Because the fact of the matter is that the vast majority of perpetrators of sexual assault will not go to jail. And so handwaving the idea of the few who have have in fact been incarcerated feels so incredibly dismissive of the hell that survivors have to go through to even get a perpetrator in court. It devalues the incredibly hard work done by the survivor to make sure that the perpetrator doesn't skip off into the sunset.

I don't know, it just got my hackles up. I know too well of how many pupatrators slip through the cracks and of how incredibly hard it is to even get a conviction in the first place. And yet prison abolitionists dismiss even the small percent as an afterthought not worth nuanced discussions.

Sorry for dumping this all into your askbox, it just seems to help to be able to type everything out so it's not just swirling in my head...

The constant pattern I see from prison abolitionists is that someone asks okay, so what are we going to do with the murderers? "Well, if we improve social conditions there won't be as many murderers!" Okay cool. But what are we doing with the remaining murderers? "You know, most murderers aren't even caught, so most of them aren't in jail anyway!" Okay cool. So what are we doing with the murderers we do catch? "You know, putting people in jail doesn't bring the victim back. Most murderers don't murder again!" Okay cool. So what do we do with repeat offenders? "Oh my god, I'm so sick of people constantly asking that question when I've answered it a million times!"

And I think it's because at some point you have to argue either a) you are a genuine prison abolitionist and don't believe serial murderers and rapists should be incarcerated, which is insanely unpopular and will cause 99% of people to stop listening to you, b) some murderers and rapists SHOULD be incarcerated, at which point you are arguing for prison reform and not prison abolition (and this will make you A Liberal, which is the worst thing a person can be), or c) if we solve all of society's problems, nobody will ever commit a violent crime ever again because humans are Good At Heart and only ever do bad things out of necessity or poor social conditions.

I think c) is a ridiculously naive view of the world, held by people who shape their view of reality based on their ideology instead of vice-versa, but it's the most palatable option for a lot of people. So you have to pretend that there's some fixable underlying condition that causes people to rape, because otherwise c) won't work and you're back to the other two options.

So yeah, I think a lot of abolitionists - at least the ones I've interacted with - can come off as though they don't care about victims of crime, because admitting that there are serial perpetrators that will not stop as long as they have access to victims really kind of undercuts the entire abolition argument.

#prison abolitionists who want to argue in good faith - feel free#prison abolitionists who want to yell at me for misrepresenting the movement and tell me that i would understand if I just read#this or that book - feel free to reread my first paragraph

110 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, what is "restorative justice" for repeat violent offenders, then?

I actually kind of favor transformative justice, which aims to address the root causes of these problems and change the circumstances, patterns, & larger systems that perpetuate them.

I'm not an expert on this by any means, but my understanding from what I've read and heard experts say is that addressing violent crimes through transformative justice largely involves strengthening social services/supports and improving the living conditions people are in, which reduces stress and other motivators for violence. My personal/professional perspective as an educator is that teaching folks how to connect and get what they need from their communities in healthy, safe, nonviolent ways is also important, and readily actionable... but I'm sure I have an inflated sense of how important that is in the grand scheme.

on an individual level, and as a non-expert, I think what's needed is to remove folks from the situation in which they are enacting harm, prevent them from enacting further harm, and then to move forward with rehabilitation efforts. Oftentimes this means removing the victim(s) rather than the person who is violent, if only because trying to revoke their autonomy can be a catalyst for more violence (and in longer-term situations like you're describing, revoking their access to healthy community connection can contribute to the circumstances causing that behavior in the first place) but that's not always possible or realistic.

This is how it works with kids (even physically violent and aggressive kids!) and kids aren't actually like, separate species from adults. I can tell you from experience that what works with kids generally works just fine with adults, too.

But again, I'm not an expert! I encourage you to reach out to abolitionist activists, experts, and groups working toward this future now with these kinds of questions. The curiosity is great!

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i'm a follower, & i enjoy reading your posts and essays. in your recent post about the anti-intellectualism kerfuffle on tumblr, you said, "Part of my communism means believing in the abolition of the university; this is not an ‘anti-intellectual’ position but a straightforwardly materialist one."

i haven't heard of university abolition before, and if you are willing, i would like to hear what it's about. what is the university abolitionist image of a better alternative to universities? should learning still be centralized?

thanks for your consideration. :)

University abolition, as with any other form of abolition worth its salt, understands the role played by the institution of the university under capitalism in sustaining the conditions of capitalist-imperialist hegemony, analyses the institution accordingly, and recognises that the practices that the university purports to represent (that of intellectual production, the sharing and developing of knowledge) will undergo a fundamental overhaul and reconstitution under communism. This means looking at the university not merely as an organic institution wherein we study and develop ideas, but asking what ideas are developed and legitimised, and who is afforded the opportunity to do so, and why the university exists in the first place; we are taking a materialist rather than idealist approach.

Simply put, the role of the university is to restrict access to knowledge and knowledge production, and to ensure the continuance of class divides and hierarchised labour. These restrictions come about in a vast number of ways; the most immediately obvious is the fact that one must meet a certain set of criteria in order to qualify for entrance in the first place, and this criteria tends to require compliance with the schooling system (itself another such arm of capitalist governance), a certain amount of wealth (and/or a willingness to accrue debt), and an ability to demonstrate methods of intellectual engagement compliant with the standard of the academy. Obviously, there are massive overlaps in this set of criteria; those who come from wealthier backgrounds are more likely to have had a good education and thus can better demonstrate normative intellectual engagement, those who can demonstrate that engagement have probably complied with the schooling system, and so on. The logic behind the existence of private schools is the idea that sufficient wealth can near-enough secure your child's entry into the university and therefore entry into the wealthier classes as an adult, with the most prestigious institutions overrun by students from privately educated backgrounds. Already, you can see how this is a tactic that filters out people from marginalised backgrounds; if you’re too poor, too un[der]educated, too disabled, not white enough, &c. &c., your chances of admittance into higher education grow slimmer and slimmer.

Access to the university affords access to knowledge; most literally through institutional access to books, papers, libraries, but also through participation in lectures and seminars, reading lists, first-hand contact with active academics, the opportunity to produce work and receive feedback on it, the opportunity to develop your own ideas in a socially legitimised sphere. As I explained above, who is afforded access to such knowledge is stratified and limited; the institution is hostile to anyone deemed socially disposable under capitalism. Access to the university also affords access to a university degree, with which you can continue down the research path (and thus participate in the cycle of radical knowledge-production being absorbed and defanged by the academy, and water down your own ideas to make them palatable to institutions which tend to balk at anything with serious Marxist commitments), or gain entry to better-paid, more stable, more prestigious jobs than those which people without degrees are most often relegated to. In this sense, the people who are more likely to be able to meet the access criteria for the university and then successfully participate in it are able to retain their class position (or else promulgate the myth of social mobility as a solution to mass impoverishment) and thus gain a vested interest in maintaining the conditions of hegemony. Those who gain entry into the middle class have done so after undergoing a process of stratification according to means; which is to say, class, race, [dis]ability; and tend to lose interest in defending a politic which seeks to destabilise their relatively privileged position in the pecking order.

Success in a research career, too, depends upon liberties afforded by wealth; can you afford to go to all these conferences, do low-paid and insecure teaching work in the university, churn out research, and support yourself through a postgrad degree without going insane? Not if you don’t have independent means. In the UK, the gap between undergrad and masters funding is absolutely wild—obviously there are scholarships afforded to a limited number of people (another access barrier—the whole institution runs on the myth of artificial scarcity), but broadly speaking, it’s pretty much impossible to put yourself through an MA with just the money you get from SFE unless you work a lot on the side to pay your bills (this is what I tried to do; I went insane and dropped out, lmfao) or have independent wealth. Establishing oneself as an ‘academic’ is simply easier when you have financial security. In this way, the people who make it to the very top of academia (the MAs, the PhDs) tend to be people who come from privileged backgrounds; people who are less likely to challenge hegemony, who will maintain the essential conditions by which the university sustains itself, which is to say the conditions of social stratification. These people often tend to hold reactionary positions on class—the people who are outraged at how little a stipend postgrad students get tend not to think twice about the university’s cleaners being paid minimum wage, or think of working-class jobs as shameful failstates from which their academic qualifications have allowed them to escape (how many people have you heard get absolutely aghast at the thought of ‘[person with a BA/MA/PhD] working a typically working-class job’?). Academic success tends to engender buying into the mythology of academia as a class stratifier and class stratification as indicative of one’s value, even amongst people who probably call themselves academic Marxists.

Universities are also tangible forces of counterinsurgency. I live in the UK, where universities are huge drivers of gentrification; university towns and cities will welcome mass student populations, usually from predominantly middle-class backgrounds and often coming to cities with significant working-class and immigrant communities, neighbourhoods formerly home to those communities will be effectively cleaned out so that students can live there, and the whole character of the neighbourhood changes to accommodate people from well-off backgrounds who harbour classist, racist feelings towards the locals & who will assimilate into the salaried middle-class once they graduate. More liberally-oriented universities will tend to espouse putatively progressive positions whilst making no effort to forge a relationship with grassroots movements happening on the streets of the city they’re set up in; student politics absorbs anyone with even slightly radical inclinations whilst accomplishing approximately fuck-all save for setting a few people off on the NGO track; like, the institution defangs radical potential whilst contributing to the class stratification of the city it’s set up in.

This is without even touching on the role played by the university in maintaining conditions of imperialism and neocolonialism, both through academic output regarding colonised regions (from ‘Oriental studies’ to the proliferation of white academics who specialise in ‘Africa’ to the use of the Global South as something of a playground for white Global North academics to conduct their research to the history of epistemologies such as race science as transparently fortifying and legitimating the imperialist order) and through material means of restricting access to and production of knowledge based on country of origin (universities in the Global South are significantly limited in what academic output they can access compared to those in the Global North; engagement with Global North academia relies on the ability to move freely, something that is restricted by one’s passport; language barriers and the primacy of English in the Global North academy) keeping knowledge production in the Global South dependent on the hegemony of the North. Syed Farid Alatas has termed this ‘academic dependency,’ as a corollary to dependency theory; academia in the GS is shaped by the material dependence it has on the West, which in turn restricts the kind of academic work that can be undertaken in the first place. Ultimately, all institutions under capitalism must ultimately reroute back to the conditions that favour capitalism, and the university is not an exception.

This is just a very brief overview of an expansive topic; I would recommend going away and examining in greater detail the role played by the university under capitalism, and what the institution filters out, and why. What sort of research gets funding? What sort of knowledge gains social legitimacy? What can the university absorb and what must it reject? Who is producing knowledge and to whom are they accountable? etc.

518 notes

·

View notes

Note

For unhinged and deranged ships: Voldemort/Narcissa, with the explcit purpose of making sure Lucius knows about it as one more way for Voldemort to fuck him and his family over (literally!)

thank you very much for the ask, anons!

now... here's why i declare myself a citizen of cissamort nation, a ship i actually find fascinating enough for a wee bit of it to be chilling in the wip folder...

and the reason i find it so interesting is because it enables me to indulge one of my favourite things to explore when writing voldemort - his extremely complicated relationship with wizarding social convention.

by which i mean, his blood- and magic-supremacist views are obviously sincere, he does genuinely think that being pureblood makes somebody better than having muggle ancestry [he just doesn't include himself in that category].

but he doesn't respect the social order - and its norms - which the wizarding world has invented to uphold blood-supremacy - not least because he clearly doesn't think these are sufficient to keep all the mudbloods at bay. he is singularly lacking in deference towards the class system, he shuns the expected behaviours of "polite" society, he wants to tear down the established order and make it anew...

and he has very little respect for those among his death eaters who would prefer to do otherwise.

that is... lucius and narcissa.

lucius enters such a flop era from order of the phoenix onwards because voldemort is clearly fuming about the fact that he preferred to insist he was under the imperius curse during the first war - rather than, like his brother- and sister-in-law, refusing to denounce the cause - because he didn't want to lose the comfortable, socially-prominent life he had by virtue of his name, wealth, and blood status. voldemort goes to great lengths throughout the latter books of the series to punish him for this by specifically attacking the maintenance of social norms which lucius values so highly [by squatting in the malfoys' home, refusing to behave like a guest, and humiliating his host before his peers; by constantly emasculating lucius; by treating his son and heir as expendable; and so on].

and lucius and narcissa's turn against voldemort - as much as it's connected to their love for draco [and as much as they do seem to be sincerely good parents] - is also connected to their growing realisation that, if voldemort wins, they will be made pariahs, and will never again enjoy the life at the top of the pile they've had for so long.

however, while voldemort's ire is beamed straight at lucius, his feelings towards narcissa are - it's clear in canon - rather more complicated...

because while voldemort evidently doesn't like her, he seems to dislike her predominantly as a cipher for social convention - and, specifically, for gendered social convention.

or, she becomes collateral damage in his quest to humiliate lucius by painting him as a failure of a man. voldemort spends the opening of deathly hallows insulting the conventions narcissa canonically takes pride in as an elite pureblood wife and mother... but he does so by, even if not entirely intentionally, portraying her as someone lucius should also feel ashamed of disappointing by his lack of proper masculinity.

i don't think this is because he respects the role of the pureblood woman as narcissa would understand it [the lack of opportunity afforded to elite pureblood women - all of whom seem to be married when they're barely out of school, don't work, and don't seem to be particularly socially visible - seems to me like something he would perceive as dishonouring the superiority their blood-status and magical power should afford them], and nor do i think he's some sort of "free her from her shackles" marriage abolitionist.

but i think he can be written as thinking of narcissa as someone he pities [although certainly not in a particularly kind or empathetic way] and sees as having been denied "proper" experiences because her husband's a worthless peacock-fucker, and whom he thinks would benefit from receiving the attention of someone who actually knows what he's doing...

and we have our potential setting right there on the page in order of the phoenix, as narcissa becomes central to voldemort's plans to retrieve the prophecy - with lucius circumvented throughout the plotting stage - when kreacher goes to her when sirius orders him to leave grimmauld place, and provides her with information that - it's implied - many of the rank-and-file death eaters wouldn't appreciate the importance of, but voldemort very much does.

narcissa's significance to voldemort's prophecy caper is reduced in the watsonian text by harry's grief over sirius - which associates the debacle in the department of mysteries in his mind primarily with bellatrix, and therefore ends up linking kreacher's great affection for bellatrix to his betrayal of her cousin.

but it's there.

and it must have involved narcissa spending the odd night shut up with the dark lord in her best guest bedroom.

#asks answered#asenora's opinions on ships#unhinged and deranged ships#or not as the case may be#cissamort#narcissa malfoy#tom riddle#lord voldemort

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

So in my home country there's a Fucked. Up. juvenile prison camp system/program being trialed (again. It apparently wasn't catastrophically useless and bad enough last time) and it's going terribly. Out of 10 teenagers forced into this program three months ago, one is dead, one escaped during the first one's funeral, one is already reoffending before the program is even over, and the cops were looking for two more (just found them! Carjacking people while armed with a machete.)

So I would really love to hear about prison abolition because whatever the fuck that was is not working at all, for anyone.

God, that's really fucking awful. I wish I could say I was surprised to hear about it, but I know too much about prison systems for that. Most of my work is with adults, and they break my heart bad enough.

You're absolutely right, though, that the system we have isn't making anything better, and it's almost certainly making it worse. You gotta think to yourself, we wouldn't let these kids sign a contract or make major financial decisions on their own. Kids are legally treated like property, at least here in the US where we don't have a children's bill of rights. How can you hold someone accountable for a crime when they're not allowed any sort of legal agency in their life otherwise?

A prison abolitionist approach to juvenile crime, I think, starts with the Convention on the Rights of the Child or a similar bill of rights, which must be approached in a way that doesn't lead to unnecessary or discriminatory child removal. Giving kids agency over their care means giving them the right to say who they want to live with and under what circumstances.

It involves financially investing in care networks for kids, including providing for families so that poverty doesn't become a reason a child can't stay with family. It involves a robust foster care system with a primary goal of reunification, not adoption. It involves mandatory public schooling with funding for adequate student-to-teacher ratios, nurses, and social workers who can identify and do early intervention when behavioral issues arise. It involves providing educational and career opportunities to low-income neighborhoods to make gangs a less enticing option. It means stricter gun restrictions, because a kid with anger and impulse issues is far less dangerous than a kid with anger, impulse issues, and a gun.

Basically, we need the resources and political will to look at the circumstances that are bringing youth offenders into the situations where the offenses occur, do root cause analysis, and place systemic interventions in place to reduce or prevent those circumstances from reoccurring. It's a huge project, but it has to start with allowing agency and human rights to children.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arizona State Professor Defends Sex Trafficking

The objective isn’t homosexual depravity in particular, but degeneracy in general. Why else would a college professor defend sex trafficking?

Arizona State University Professor Crystal Jackson condemned the “anti-trafficking movement” and “deviant framing” of “sex workers” during an event on campus last week.

That which liberals want to normalize, they euphemize. Just as “MAP” is their euphemism for pedophile, “sex worker” is Liberalese for prostitute.

During the “Queer X Faculty Flashtalks” event, Jackson told the students and staff in attendance that “Sex workers have been and are at the heart of queer liberation.”

She isn’t the first to notice a connection between LGBTism and other sexual manifestations of moral decay.

“We wouldn’t have the modern-day LGBTQ plus movement in the U.S. … without sex-working trans people,” she said.

Of all the lame arguments for normalizing prostitution, doing it to promote transsexual psychosis may be the least compelling.

The professor also condemned the anti-trafficking movement.

The nutty professor screeches that “moral panic” about sex trafficking — i.e., sex slavery, which often involves children — constitutes thoughtcrime:

“It’s anti-immigrant, it’s racist, it’s transphobic forms of policing, particularly around women of color.”

ASU is a state school, meaning that an extra large percentage of its funding is provided on an involuntary basis. Here’s how our money is being spent:

She told attendees her previous research includes “the tenuous feminisms of self-proclaimed queer porn mafia performers and producers who then honor the grandfather of queer porn, trans male porn performer Buck Angel.”

Her bio on ASU’s website does not shy away from her defense of sex trafficking:

Crystal A. Jackson (they/she) is a Women, Gender, & Sexualities Studies (WGSS) professor in [the School of Social Transform]. They are a sociological feminist scholar whose research underscores feminist and queer understandings of sexual labors and gender politics in the United States. … Their current research explores how the racial justice concept of ‘abolitionism’ is deployed in mainstream, institutionalized U.S. anti-sex trafficking policies and advocacies to demand actions that are in direct opposition to racial justice abolitionist aims.

Presenting Professor Crystal Jackson, accredited member of the intelligentsia:

Is she or isn't he.....who the hell knows anymore.

23 notes

·

View notes