#Zika and Dengue Virus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#Dengue Fever Symptoms#Dengue Virus#Dengue Fever Treatment#How to Prevent Dengue#Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever#Dengue Fever Vaccine#Dengue Transmission#Dengue Mosquito#Dengue Outbreak#Dengue Fever in Children#Dengue Fever Prevention Tips#Dengue Fever Causes#Signs of Dengue Fever#Dengue Fever in Pregnancy#Dengue Control Measures#Zika and Dengue Virus#Global Dengue Statistics#Dengue Fever Risk Areas#Dengue Fever Diagnosis#Dengue Fever Treatment Guidelines#health & fitness

1 note

·

View note

Text

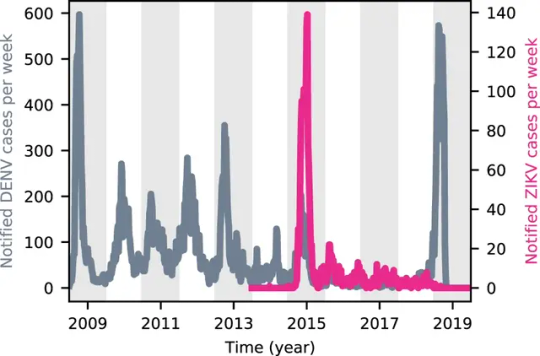

Shifting patterns of dengue three years after Zika virus emergence in Brazil

In 2015, the Zika virus (ZIKV) emerged in Brazil, leading to widespread outbreaks in Latin America. Following this, many countries in these regions reported a significant drop in the circulation of dengue virus (DENV), which resurged in 2018-2019. We examine age-specific incidence data to investigate changes in DENV epidemiology before and after the emergence of ZIKV. We observe that incidence of DENV was concentrated in younger individuals during resurgence compared to 2013-2015. This trend was more pronounced in Brazilian states that had experienced larger ZIKV outbreaks. Using a mathematical model, we show that ZIKV-induced cross-protection alone, often invoked to explain DENV decline across Latin America, cannot explain the observed age-shift without also assuming some form of disease enhancement. Our results suggest that a sudden accumulation of population-level immunity to ZIKV could suppress DENV and reduce the mean age of DENV incidence via both protective and disease-enhancing interactions.

Read the paper.

#brazil#dengue#zika virus#science#politics#brazilian politics#epidemiology#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#399#biologia#sociedade#pseudociencia#repelente#dengue#zika#chikungunya#aedes aegypti#vírus#virus#pseudociência#aedes

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grad priprema mjere protiv tigrastih komaraca

#azijski tigrasti komarac#borba protiv komaraca#chikungunya virus europa#dengue groznica njemačka#higijena dvorišta#klimatske promjene i komarci#komarci prijenosnici bolesti#münchen zdravlje#mjere protiv komaraca#mueckenatlas identifikacija#muenchen.de tigermuecke#opasni komarci njemačka#prevencija komaraca#stajaća voda i komarci#suzbijanje komaraca#tigrasti komarac münchen#zaštita od komaraca#zaštita okoliša münchen#zdravlje građana münchen#zika virus münchen

0 notes

Text

Natural Mosquito Repellents: Do They Really Work?

Looking for natural mosquito repellents that actually work? In our “Budget Slow Travel in Retirement” Facebook group, we recently had a buzzing debate about natural mosquito repellents, and we’re here to share the sting-free solutions (and maybe a few laughs along the way). Photo by Luis klink on Pexels.com Table of Contents The Mosquito Conundrum: A Bite Out of Your Travel Bliss Natural vs.…

#Avon Skin So Soft#DEET#dengue fever#essential oils#malaria#mosquito-borne illnesses#Mosquitoes#natural mosquito repellents#Picaridin#travel tips#Zika virus

0 notes

Text

FDA approves first vaccine against chikungunya

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced on Thursday the approval of Ixchiq, the first vaccine against the chikungunya virus. This disease, transmitted mainly by infected mosquitoes, has been recognized as an emerging threat to global health, with more than 5 million cases reported in the last 15 years.

The approval focuses on individuals over 18 years of age with a higher risk of exposure to the virus, especially in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Southeast Asia and parts of the Americas, where carrier mosquitoes are endemic. Read more

#lifestyle#motivation#fitness#health#healthylifestyle#wellness#healthy#fit#healthcare#healthyliving#selfcare#life#mentalhealth#chikungunya#dengue#zika#mosquito#malaria#vaccine#virus#FDA

0 notes

Text

Pairing frogs and toads together might conjure memories of Arnold Lobel’s beloved characters — dressed to the nines in caramel coats and polyester — biking off toward adventure.

But in the animal world, frogs and toads on nearly every continent are facing a much more harrowing adventure: a decades-long fight against a mysterious fungal virus that has afflicted over 500 amphibian species.

Since the 1990s, scientists estimate that the chytridiomycosis disease caused by the fungal pathogen Bd (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) has led to the extinction of 90 amphibians. One of the lost species includes the Panamanian golden frog, which hasn’t been spotted in the wild since 2009.

Fortunately, a new research study has finally pinpointed the virus that has been infecting fungal genomes for decades.

“Bd is a generalist pathogen and is associated with the decline of over 500 amphibian species…here, we describe the discovery of a novel DNA mycovirus of Bd,” wrote Mark Yacoub — the lead author of the study and a microbiology doctoral student at the University of California, Riverside.

In an interview with UC Riverside News, Yacoub said that he and microbiology professor Jason Stajich observed the viral genome while studying the broader population genetics of mycovirus (viruses of fungi).

The discovery will undoubtedly have monumental impacts on future amphibian conservation efforts. This includes the possible launching of new research studies into fungal species strains, the practice of cloning and observing spores, and engineering a solution to the virus.

But Yacoub cautioned that this is only the beginning.

“We don’t know how the virus infects the fungus, how it gets into the cells,” Yacoub said. “If we’re going to engineer the virus to help amphibians, we need answers to questions like these.”

Still, as scientists strengthen conservation efforts to save frogs and toads (and salamanders too!) they also appear to be saving themselves. Yacoub pointed out several amphibian species around the world have begun exhibiting resistance to Bd.

“Like with COVID, there is a slow buildup of immunity,” Yacoub explained. “We are hoping to assist nature in taking its course.”

Pictured: A Golden poison frog — one of the many species endangered by chytridiomycosis — in captivity.

Why are frogs and toads so important?

From the get go, every amphibian species plays an important role in their local ecosystem. Not only are they prey for a slew of animals like lizards, snakes, otters, birds, and more, but in an eat-or-be-eaten world, frogs and toads benefit the food chain by doing both.

Even freshly hatched tadpoles — no bigger than a button — can reduce contamination in their surrounding pond water by nibbling on algae blooms.

As they grow bigger (and leggier), amphibians snack on whatever insect comes their way, greatly reducing the population of harmful pests and making a considerable dent in the transmission malaria, dengue, and Zika fever by eating mosquito larvae.

“Frogs control bad insects, crop pests, and mosquitoes,” Yacoub said. “If their populations all over the world collapse, it could be devastating.”

Yacoub also pointed out that amphibians are the “canary in the coal mine of climate change,” because they are an indicator species. Frogs and toads have permeable skin, making them sensitive to changes in their environment, and they also rely on freshwater.

When amphibians vanish from an ecosystem, it’s a symptom of greater environmental issues...

Herpetologist Maureen Donnelly echoed Yacoub’s sentiments in an interview with Phys Org, noting that when it comes to food chains, biodiversity, and environmental impact, the role of frogs and toads should not be overlooked.

“Conservation must be a global team effort,” Donnelly said. “We are the stewards of the planet and are responsible for all living creatures.”

-via GoodGoodGood, April 22, 2024

#frog#frogs#toads#frogs and toads#conservation#biodiversity#herpetology#mycology#fungi#endangered species#extinction#ecosystems#climate change#environment#biology#environmental science#ecology#good news#hope#frogblr#frog blogging

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

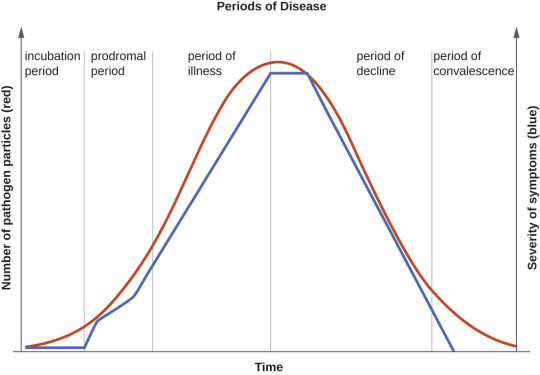

Incubation Periods List

Hi all!

The following is a list of incubation periods for various infectious diseases for all your writing needs. An incubation period is the amount of time between exposure to an infectious agent (bacteria, virus, protozoa or prion) and the person having the first symptoms of the resulting illness. Knowing this is helpful in creating a timeline for your story.

Anthrax: Incubation period of 1-60 days

Avian Flu: Incubation period 3-9 days

Botulism: Incubation period 12-72 hours

Chikungunya: Incubation period 3-7 days

Chlamydia: incubation period 7-21 days

COVID-19: Incubation period 5-10 days

Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease: Incubation period 10-20 years

Dengue: Incubation period 5-7 days

Diphtheria: Incubation period 2-5 days

Ebola: Incubation period 2-21 days

Hantavirus: incubation period 1-8 weeks

Hepatitis A: incubation period about 28 days

Herpes: Incubation period 2-12 days

Herpes Zoster/Varicella (Chickenpox): Incubation period 14-16 days

Herpes Zoster (Shingles): Incubation period- technically none, as this is a reactivation of the virus that causes chickenpox

HIB: Incubation period 2-10 days

HIV: Incubation period 1-6 weeks to prodrome, approximately 10 years to AIDS

Influenza: Incubation period 1-4 days

Legionnaires Disease: Incubation period 5-6 days

Leprosy: Incubation period 9 months to 20 years

Lyme Disease: Incubation period 3-30 days

Malaria: Incubation period 7-30 days

Measles: Incubation period 10-12 days

Meningitis, Bacterial: Incubation period 2-10 days

Meningitis, Viral: Incubation period 3-10 days

Monkeypox: Incubation period 1-2 weeks

Mumps: Incubation period 16-18 days

Norovirus: Incubation period 12-48 hours

Pertussis: Incubation period 7-10 days

Plague: Incubation period 2-8 days

Pneumococcal Pneumonia: Incubation period 1-3 days

Polio: Incubation period 7-10 days

Q-Fever: Incubation period 2-3 weeks

Rabies: Incubation period 20-90 days

RSV: Incubation period 4-6 days

Smallpox: Incubation period 7-17 days

Syphilis: Incubation period 10-90 days

Tetanus: Incubation period 3-21 days

Tuberculosis: Incubation period 2-10 days

Typhoid: Incubation period 6-30 days

Typhus: Incubation period 1-2 weeks

West Nile Virus: Incubation period 2-6 days

Yellow Fever: Incubation period 3-6 days

Zika: Incubation period 3-14 days

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

VERRÀ LA MORTE E BERRÀ IL TUO SANGUE

(Prima parte di una serie divulgativa sulla prossima apocalisse pandemica)

Buongiorno, bambini! Chi mi sa dire qual è l'animale più pericoloso sul pianeta terra?

Il leone! Lo squalo! L'orca sassina! La tigre! Il gorilla! Il rinoceronte! I fascisti di forza nuova!

Gigino ricordami di non lasciarti tutto il giorno con zio Stanislao, comunque, no bambini... l'animale che ha ucciso più esseri umani nei nostri secoli di storia è...

... la zanzara!

Repubblica.it dice che ha sterminato 50 miliardi di persone nei nostri 300.000 anni di storia ma siccome sarò anche vostro papà però anche un castoro senza pollice opponibile non ho possibilità di verificare le fonti in modo approfondito.

Diciamo, però, che le zanzare sono praticamente ovunque, tranne in Islanda e ai poli, e nei millenni di convivenza con l'uomo sono diventate un vettore preferenziale per molti virus che si sono mutati per replicarsi all'interno delle loro ghiandole saliv...

Anche il raffreddore?

No, Genoveffa, solo alcuni patogen...

Anche l'aids dei finocchi?

No, Balilla... e ricordami di non lasciarti tutto il giorno con zio Benito. Ecco, vi ho appena inviato sui vostri tablet la lista di virus, batteri e parassiti trasmissibili dalla famiglia delle Culicidae (che sarebbero le zanzare).

Malaria Chikungunya Filariasi Dirofilariasi Dengue Zika West Nile Virus Febbre gialla Febbre della Rift Valley Encefalite giapponese Encefalite di Saint Louis Encefalite LaCrosse Encefalite equina orientale Encefalite equina occidentale Encefalite equina venezuelana Febbre di Ross River Febbre da Barmah Forest

Naturalmente non tutte le 3540 specie di zanzara trasmettono tutte queste malattie sia perché non tutti i patogeni sono adatti a replicarsi in ogni ghiandola salivare sia perché molte malattie sono tipiche di un paese specifico con un certo tipo di zanzara che sopravvive solo con un certo clima.

A tale proposito, mi premeva farvi notare come quando io ero giovane non solo saltavo i fossi per il lungo e invece voi vi fate venire la tendinite da smartphone ma d'inverno venivano quattro metri di neve e l'estate si poteva stare a torso nudo senza morire di ustioni attiniche di 4° grado e questo è colpa de...

Delle scie chimiche massoniche dei poteri forti!

No, Giustino… e ricordami di non lasciarti tutto il giorno con zio Beppe.

È colpa del cambiamento climatico che ha portato a una tropicalizzazione di latitudini dove normalmente le zanzare tropicali vettrici di tali virus non sarebbero sopravvissute.

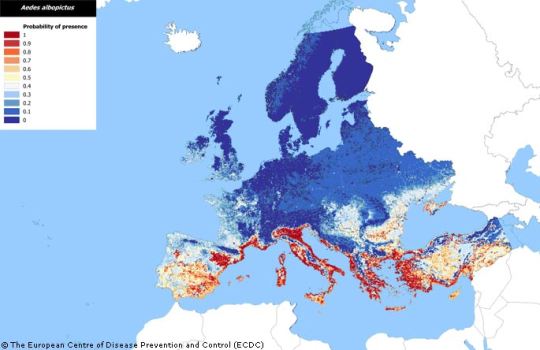

Siccome, a dispetto di quanto gli italiani credano, noi castori siamo una specie che fino al 1540 ha popolato per secoli lo stivale (salvo poi diventare tutti copricapi), ho le carte di cittadinanza in regola per parlare di tale paese e pubblicare questa mappa:

con cui nel 2008 si registrava l'iniziale presenza della zanzara Aedes albopictus, la cosiddetta Zanzara Tigre, che ha quasi completamente soppiantato la meno feroce Culex pipiens, la nostra 'vecchia' zanzara monocolore che pungeva solo di notte

(albo+pictus, pitturata di bianco... anche se a me sembrano pallini e non le presunte strisce di una tigre)

e di seguito una vecchia proiezione statistica - oggi realtà - su come si sarebbe riprodotta ed espansa

Voglio dirvi però, piccoli castorini, che le quattro malattie che puntualmente gli italiani si ritrovano a scoprirsi addosso ogni estate (Zika, Dengue, Chikungunya e Febbre da West Nile Virus) in realtà hanno modalità di incubazione e trasmissione che le rendono meno pericolose di quanto sembra, perché ci devono essere parecchi fattori concomitanti per la comparsa:

PRIMA DI TUTTO CI VUOLE UNA ZANZARA INFETTA

Graziarca' mi direte voi ma considerate che una zanzara può replicare il virus nelle proprie ghiandole salivari solo se punge una persona infetta in fase attiva, quindi non nei prima 4-7 giorni della comparsa dei sintomi e non dopo 15 giorni.

La zanzara può infettare solo dopo 7-10 giorni (tempo di replicazione nelle ghiandole) e dal momento che una zanzara ne vive solo 30, il tempo utile è poco (il virus non si trasmette da zanzara a zanzara o alle uova).

Oltretutto non è detto che la carica virale dell'umano infetto sia sufficiente alla replicazione nella zanzara o che la puntura della zanzara abbia sufficiente carica virale da infettare.

Quegli R0 e Rt esponenziali che abbiamo visto con il Covid scordateli, insomma.

Infatti, tranne l'ultimo caso di Dengue del 70enne lodigiano che è sempre rimasto in Italia, tutte le infezioni sono state contratte all'estero e 'portate' senza grosse conseguenze in Italia.

La mia è un'intuizione e quindi vale solo per fare apocalisse zombie su tumblr ma credo che se si cominciasse a fare titolazioni anticorpali tra la popolazione, sono quasi sicuro che verrebbero fuori MOLTE persone positive a vecchie infezioni causate da questi virus.

Perché i sintomi comuni a tutte queste infezioni sono spossatezza, mal di testa, dolori articolari e difficoltà alla concentrazione...

Praticamente io sono ammalato di Dengue ogni Lunedì.

Seguiranno approfondimenti su modalità di manifestazione e trattamento.

Grazie dell'attenzione e dell'eventuale gentile reblog di condivisione.

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unhinged vaccine fetishist implies that microbiology is on a political timetable.

John Leake

Dec 05, 2024

On January 11, 2017, Dr. Anthony Fauci gave a talk on pandemic preparedness at Georgetown University in which he stated:

‘No doubt’ Trump will face surprise infectious disease outbreak.

I was reminded of Dr. Fauci’s amazing prescience, less than ten days before Trump was sworn in for his first term, when I saw Dr. Peter Hotez making an unhinged rant in a Dec. 4, 2024 interview with MSNBC’s Nicolle Wallace.

“We have some big picture stuff coming down the pike starting on January 21st,” Hotez proclaimed, and then let us us know all of the emerging infectious diseases that he implied are on a political timetable.

Bird flu

New Coronavirus

SARS

Mosquito-transmitted viruses

Dengue

Zika

Oropouche virus

Yellow fever

Pertussis/Whooping cough

Measles

Polio

As Freud famously remarked, people often reveal their subconscious wishes and fantasies in their word choice. I don’t think I’m speculating too much in drawing the conclusion that Dr. Hotez can’t wait for the U.S. to be afflicted by another plague.

His explicit characterization of January 21 as marking the Advent of various plagues reminds me of the Revelation of John, who imagined that the Roman Empire under Nero, with its tyranny and depravity, would face an ultimate reckoning that would appear in the form of Four Horseman representing Deception, War, Famine, and Pestilence—the final being represented as a pale rider on a white horse.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canada recently issued a travel advisory following the emergence of the Oropouche virus, also known as the 'sloth virus', transmitted through flying insect bites, causing outbreaks in Cuba and South America. Below is an explanation of what the virus is and how it spreads.

Written by Cameron Webb, University of Sydney and Andrew van den Hurk, The University of Queensland

International authorities are issuing warnings about “sloth fever”. Despite the name, it’s not contracted via contact with sloths. Rather, you should avoid contact with mosquitoes and biting midges.

So how can Canadians protect themselves from sloth fever when travelling to South and Central America? And how does “sloth fever” compare with other mosquito-borne diseases, such as Zika?

What is ‘sloth fever’?

Sloth fever is caused by Oropouche virus and is formally known as Oropouche virus disease or Oropouche fever.

The virus is an orthobunyavirus. So it’s from a different family of viruses to the flaviviruses (which includes dengue, Japanese encephalitis and Murray Valley encephalitis viruses) and alphaviruses (chikungunya, Ross River and Barmah Forest viruses).

Oropouche virus was first identified in 1955. It takes its name from a village in Trinidad and Tobago, where the person who it was first isolated from lived.

Symptoms include fever, severe headache, chills, muscle aches, joint pain, nausea, vomiting and a rash. This makes it difficult to distinguish it from other viral infections. Around 60% of people infected with the virus become ill.

There is no specific treatment and most people recover in less than one month.

However, serious symptoms, including encephalitis and meningitis (inflammation of the brain and membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord) have occasionally been reported.

What’s happening with this latest outbreak?

In July, the Pan American Health Organization issued a warning after two women from northeastern Brazil died following infection with Oropouche virus, the first fatalities linked to this virus.

There has also been one fetal death, one miscarriage and four cases of newborns with microcephaly, a condition characterized by an abnormally small head, where infection during pregnancy occurred. The situation is reminiscent of the Zika outbreak in 2015–16.

Oropouche had historically been a significant concern in the Americas. However, the illness had slipped in importance following successive outbreaks of chikungunya and Zika from 2013 to 2016, and more recently, dengue.

How is Oropouche virus spread?

Oropouche virus has not been well studied compared to other insect-borne pathogens. We still don’t fully understand how the virus spreads.

The virus is primarily transmitted by blood-feeding insects, particularly biting midges (especially Culicoides paraensis) and mosquitoes (potentially a number of Aedes, Coquillettidia, and Culex species).

We think the virus circulates in forested areas with non-human primates, sloths and birds as the main suspected hosts. During urban outbreaks, humans are carrying the virus and blood-feeding insects then go on to infect other people.

The involvement of biting midges (blood sucking insects mistakenly known as “sandflies”) makes the transmission cycle of Oropouche virus a little different to those only spread by mosquitoes. The types of insects spreading the virus may also differ between forested and urban areas.

Why is Oropouche virus on the rise?

The United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently issued a warning about rising cases of Oropouche in the Americas. Cases are rising outside areas where it was previously found, such as the Amazon basin, which has authorities concerned.

More than 8,000 cases of disease have been reported from countries including Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Cuba (as of August 21, 2024).

Cases of travellers acquiring infection in Cuba and Brazil have been reported on return to Europe and North America, respectively. On September 3, the Government of Canada issued a health advisory for international travellers after several travel-related cases of Oropouche were reported internationally, the majority of which were in travellers returning from Cuba.

While a changing climate, deforestation and increased movement of people may partly explain the increase and geographic spread of the virus, something more may be at play.

Oropouche virus appears to have a greater potential for genomic reassortment. This means the evolution of the virus may happen faster than other viruses, potentially leading to more significant disease or increased transmissibility.

Areas in South America with reported cases of Oropouche as of September 4, 2024 (Source: CDC)

What can travellers do to protect themselves?

There are no vaccines or specific treatments available for Oropouche virus.

If you’re travelling to countries in South and Central America, take steps to avoid mosquito and biting midge bites.

Mosquito repellents containing diethytoluamide (DEET), picaridin and oil of lemon eucalyptus have been shown to be effective in reducing mosquito bites, and are expected to work against biting midge bites too.

Wearing long-sleeved shirts, long pants and covered shoes will further reduce the risk.

Sleeping and resting under insecticide-treated mosquito bed nets will help, but much finer mesh nets are required as biting midges are much smaller than mosquitoes.

Although no specific warnings have been issued by Canadian authorities, the CDC and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control have warned that pregnant travellers should discuss travel plans and potential risks with their health-care professional.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Charlatan’ Vaccine Promoter Dr. Peter Hotez Says Multiple Viruses Will be Unleashed on America the Day After Trump Takes Office

‘Charlatan’ vaccine promoter Dr. Peter Hotez said multiple viruses will be unleashed on America one day after Trump is inaugurated next month.

“We have some big picture stuff coming down the pike starting on January 21st,” Hotez said to MSNBC’s Nicolle Wallace before rattling off a list of viruses:

Bird flu

New Coronavirus

SARS

Mosquito-transmitted viruses

Dengue

Zika

Oropouche virus

Yellow fever

Pertussis/Whooping cough

Measles

Polio

Of course, Dr. Hotez failed to mention the measles outbreaks and Polio cases are primarily a problem with the illegal migrants invading the US.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The virus behind an outbreak in Brazil can spread from mother to fetus

Transmission of Oropouche to the womb means it has a feature in common with Zika and dengue

A virus that caused a large outbreak in Brazil this year can spread from a pregnant woman to the fetus. The confirmation of several cases of transmission to the womb means that the virus, called Oropouche, has a feature in common with two other insect-borne viruses, Zika and dengue.

A 40-year-old woman’s stillbirth this summer in Brazil was linked to transmission of the virus from the woman to the fetus, researchers report October 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine. (The World Health Organization defines a stillbirth as the death of a fetus after 28 weeks of pregnancy.) The Brazilian Ministry of Health has also confirmed two other deaths due to the spread of Oropouche virus to the womb: a stillbirth to a 28-year-old woman and a baby born with congenital anomalies who died after 47 days. There are other potential cases of transmission to the womb being investigated.

As of mid-October, Brazil has reported more than 8,000 cases of Oropouche fever since the beginning of the year. It’s the largest outbreak in the Americas this year; some of the other countries with cases include Peru, with more than 900, and Cuba, with more than 500. Infections can cause fever, chills, joint pain and severe headaches, among other symptoms. The virus is spread mainly by the bite of Culicoides paraensis midges, which are very small flies, and sometimes by mosquitoes. As with Zika, there aren’t any medicines to treat Oropouche fever or vaccines that target the virus.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#science#medicine#biology#oropouche#image description in alt#mod nise da silveira

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘼-𝙕 𝙇𝙄𝙎𝙏 𝙊𝙁 𝘿𝙄𝙎𝙀𝘼𝙎𝙀𝙎/𝙄𝙇𝙇𝙉𝙀𝙎𝙎𝙀𝙎 𝙁𝙊𝙍 𝙎𝙄𝘾𝙆𝙁𝙄𝘾/𝙒𝙃𝙐𝙈𝙋

— A

Anemia.

Adenomyosis.

Asthma.

Arterial thrombosis.

Allergies.

Anxiety.

Angel toxicosis ( fictional ).

Acne.

Anorexia nervosa.

Anthrax.

Atma virus ( fictional ).

ADHD.

Agoraphobia.

Astrocytoma.

AIDS.

— B

Breast cancer.

Bunions.

Borderline personality disorder.

Botulism.

Barrett's esophagus.

Bowel polyps.

Brucellosis.

Bipolar disorder.

Bronchitis.

Bacterial vaginosis.

Binge eating disorder.

— C

Crohn's disease.

Conjunctivitis.

Coronavirus disease.

Coeliac disease.

Chronic migranes.

Coup.

Cushing syndrome.

Cystic fibrosis.

Cellulitis.

Coma.

Cooties ( fictional ).

COPD.

Chickenpox.

Cholera.

Cerebral palsy.

Chlamydia.

Constipation.

Cancer.

Common cold.

Chronic pain.

— D

Diabetes.

Dyslexia.

Dissociative identify disorder.

Dengue fever.

Delirium.

Deep vein thrombosis.

Dementia.

Dysthimia.

Diphtheria.

Diarrhoea.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

Dyspraxia.

Dehydration.

— E

Ebola.

Endometriosis.

Epilepsy.

E-coli.

Ectopic pregnancy.

Enuresis.

Erectile dysfunction.

Exzema.

— F

Fusobacterium infection.

Filariasis.

Fibromyalgia.

Fascioliasis.

Fever.

Food poisoning.

Fatal familial insomnia.

— G

Gonorrhoea.

Ganser syndrome.

Gas gangrene.

Giardiasis.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Gall stones.

Glandular fever.

Greyscale ( fictional ).

Glanders.

— H

Hookworm infection.

Hand, foot and mouth disease.

Hypoglycaemia.

Herpes.

Headache.

Hanahaki disease ( fictional ).

Hyperhidrosis.

Heat stroke.

Heat exhaustion.

Heart failure.

High blood pressure.

Human papillomavirus infection.

Hypersomnia.

HIV.

Heart failure.

Hay fever.

Hepatitis.

Hemorrhoids.

— I

Influenza.

Iron deficiency anemia.

Indigestion.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Insomnia.

Irritable bowel syndrome.

Intercranial hypertension.

Impetigo.

— K

Keratitis.

Kidney stones.

Kidney infection.

Kawasaki disease.

Kaposi's sarcoma.

— L

Lyme disease.

Lassa fever.

Low blood pressure.

Lupus.

Lactose intolerance.

Lymphatic filariasis.

Leprosy.

— M

Measles.

Mad cow disease.

Mumps.

Major depressive disorder.

Malaria.

Malnutrition.

Motor neurone disease.

Mutism.

Mouth ulcer.

Monkeypox.

Multiple sclerosis.

Meningitis.

Menopause.

Mycetoma.

— N

Norovirus.

Nipah virus infection.

Narcolepsy.

Nosebleed.

Nocardiosis.

— O

Obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Osteoporosis.

Ovarian cyst.

Overactive thyroid.

Oral thrush.

Otitis externa.

— P

Pancreatic cancer.

Pneumonia.

Pelvic inflammatory disease.

PICA.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Psoriasis.

Parkinson's disease.

Panic disorder.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Plague.

Postpartum depression.

Pediculosis capitis.

Psychosis.

Post-traumatic stress disorder.

— Q

Q fever.

Quintan fever.

— R

Rubella.

Rabbit fever.

Rotavirus infection.

Ringworm.

Restless legs syndrome.

Rhinovirus infection.

Rosacea.

Relapsing fever.

Rheumatoid arthritis.

Rabies.

— S

Shingles.

Sore throat.

Stutter.

Separation anxiety disorder.

Smallpox.

Scoliosis.

Septic shock.

Shigellosis.

Sepsis.

Social anxiety disorder.

Stroke.

Scarlet fever.

Schizophrenia.

Sleep apnea.

Sun burn.

Syphilis.

Sickle cell disease.

Scabies.

Selective mutism.

Salmonella.

Sensory processing disorder.

— T

Thyroid cancer.

Tuberculosis.

Thirst.

Trichuriasis.

Tinea pedis.

Tourette's syndrome.

Trachoma.

Tetanus.

Toxic shock syndrome.

Tinnitus.

Thyroid disease.

Typhus fever.

Tonsillitis.

Thrush.

— U

Urinary tract infection.

Underactive thyroid.

�� V

Valley fever.

Vertigo.

Vomiting.

— W

White piedra.

Withdrawal.

Whooping cough.

West nile fever.

— X

Xerophthalmia.

— Y

Yersiniosis.

Yellow fever.

— Z

Zygomycosis.

Zika fever.

Zeaspora.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un poco acerca de algunos animales que nos rodean

Oscar Lepe, Alejandro Várguez, Javier Guadarrama, Ferrán Rosas.

Descubramos las Razas de Gatos que Viven Más Tiempo

¿Sabías que algunos gatos pueden vivir mucho más tiempo que otros? En este artículo, exploraremos las cinco razas de gatos que destacan por su longevidad. Según PetMD, el promedio de vida de un gato oscila entre los 13 y 17 años, pero estas razas tienen la capacidad de superar esa expectativa. Desde los elegantes siameses hasta los tranquilos burmeses, estas razas ofrecen compañía felina durante muchos años. Esta investigación nos hace conocer cinco razas extraordinarias y sus cuidados, dirigido a dueños de mascotas interesados en la salud y bienestar de sus gatos.

Ahora te pregunto, ¿Qué aspectos consideras más importantes al elegir una raza de gato, la longevidad o características específicas de personalidad y apariencia?

Tipo de texto científico de divulgación.

El facinante mundo de los Anfibios: Facinante

Los anfibios desempeñan un papel crucial en la regulación de poblaciones de insectos como mosquitos, ayudando a prevenir enfermedades como el virus del dengue, zika y chikungunya. Sin embargo, el crecimiento urbano ha llevado a la disminución de los anfibios, privándonos de este beneficio. Recientemente, se descubrió que la piel de la rana leopardo contiene sustancias que podrían tratar el virus del zika y posiblemente el dengue. Además, la Rana Incubadora Gástrica, que incubaba sus huevos en su estómago para proteger a su progenie, inspiró el desarrollo de la ranitidina, un medicamento para úlcera y reflujo. Lamentablemente, esta especie se extinguió en 2002 debido a la quitridiomicosis, una enfermedad fúngica que afecta a los anfibios.

¿Interesante no? ¿Conoces algo especial de algún anfibio o te interesaría conocer más acerca de ellos?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Researchers say mosquito-borne illnesses are on the rise across the U.S., Central and South America and Europe, thanks to warming temperatures and other factors. And while West Nile virus remains the most common in the U.S., many other mosquito-borne illnesses – including Zika, malaria and dengue – are also a concern.

3 notes

·

View notes