#United Farm Workers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Much love to our Haitian brothers and sisters, who have to continue to endure this gross display of racism, ignorance, intolerance and hatred.

Sending random love and a show of support, so that you can see that not everyone is a stupid asshole.

#haitian#haitians#united farm workers#fuck trump#vote democrat#vote blue#vote harris#love your neighbor#protect the vulnerable

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Turkey Day everyone!

Today many of us will be enjoying food brought to us by the labor of migrant farm workers. If anyone would like to support the workers who have made our feasting possible I recommend donating to the United Farmworkers Association.

Do not forget the hard working people who have provided us the foods we eat every day. Even if you cannot donate, I recommend keeping these farmworkers in mind.

I also recommend following the UFW on bluesky;

520 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cesar Chavez & Joan Baez at a United Farm Workers benefit, Santa Monica, CA, December 16, 1966 © Emmon Clarke.

249 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK, I'll bite - what's the deal with the United Farm Workers? What were their strengths and weaknesses compared to other labor unions?

It is not an easy thing to talk about the UFW, in part because it wasn't just a union. At the height of its influence in the 1960s and 1970s, it was also a civil rights movement that was directly inspired by the SCLC campaigns of Martin Luther King and owed its success as much to mass marches, hunger strikes, media attention, and the mass mobilization of the public in support of boycotts that stretched across the United States and as far as Europe as it did to traditional strikes and picket lines.

It was also a social movement that blended powerful strains of Catholic faith traditions with Chicano/Latino nationalism inspired by the black power movement, that reshaped the identity of millions away from asimilation into white society and towards a fierce identification with indigeneity, and challenged the racist social hierarchy of rural California.

It was also a political movement that transformed Latino voting behavior, established political coalitions with the Kennedys, Jerry Brown, and the state legislature, that pushed through legislation and ran statewide initiative campaigns, and that would eventually launch the careers of generations of Latino politicians who would rise to the very top of California politics.

However, it was also a movement that ultimately failed in its mission to remake the brutal lives of California farmworkers, which currently has only 7,000 members when it once had more than 80,000, and which today often merely trades on the memory of its celebrated founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez rather than doing any organizing work.

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

The Origins of the UFW:

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

In the 1950s, both Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez were community organizers working for a group called the Community Service Organization (an affiliate of Saul Alinsky's Industrial Areas Foundation) that sought to aid farmworkers living in poverty. Huerta and Chavez were trained in a novel strategy of grassroots, door-to-door organizing aimed not at getting workers to sign union cards, but to agree to host a house meeting where co-workers could gather privately to discuss their problems at work free from the surveillance of their bosses. This would prove to be very useful in organizing the fields, because unlike the traditional union model where organizers relied on the NRLB's rulings to directly access the factory floors, Central California farms were remote places where white farm owners and their white overseers would fire shotguns at brown "trespassers" (union-friendly workers, organizers, picketers).

In 1962, Chavez and Huerta quit CSO to found the National Farm Workers Association, which was really more of a worker center offering support services (chiefly, health care) to independent groups of largely Mexican farmworkers. In 1965, they received a request to provide support to workers dealing with a strike against grape growers in Delano, California.

In Delano, Chavez and Huerta met Larry Itliong of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which was a more traditional labor union of migrant Filipino farmworkers who had begun the strike over sub-minimum wages. Itliong wanted Chavez and Huerta to organize Mexican farmworkers who had been brought in as potential strikebreakers and get them to honor the picket line.

The result of their collaboration was the formation of the United Farm Workers as a union of the AFL-CIO. The UFW would very much be marked by a combination of (and sometimes conflict between) AWOC's traditional union tactics - strikes, pickets, card drives, employer-based campaigns, and collective bargaining for union contracts - and NFWA's social movement strategy of marches, boycotts, hunger strikes, media campaigns, mobilization of liberal politicians, and legislative campaigns.

1965 to 1970: the Rise of the UFW:

While the strike starts with 2,000 Filipino workers and 1,200 Mexican families targeting Delano area growers, it quickly expanded to target more growers and bring more workers to the picket lines, eventually culminating in 10,000 workers striking against the whole of the table grape growers of California across the length and breadth of California.

Throughout 1966, the UFW faced extensive violence from the growers, from shotguns used as "warning shots" to hand-to-hand violence, to driving cars into pickets, to turning pesticide-spraying machines onto picketers. Local police responded to the violence by effectively siding with the growers, and would arrest UFW picketers for the crime of calling the police.

Chavez strongly emphasized a non-violent response to the growers' tactics - to the point of engaging in a Gandhian hunger strike against his own strikers in 1968 to quell discussions about retaliatory violence - but also began to employ a series of civil rights tactics that sought to break what had effectively become a stalemate on the picket line by side-stepping the picket lines altogether and attacking the growers on new fronts.

First, he sought the assistance of outside groups and individuals who would be sympathetic to the plight of the farmworker and could help bring media attention to the strike - UAW President Walter Reuther and Senator Robert Kennedy both visited Delano to express their solidarity, with Kennedy in particular holding hearings that shined a light on the issue of violence and police violations of the civil rights of UFW picketers.

Second, Chavez hit on the tactic of using boycotts as a way of exerting economic pressure on particular growers and leveraging the solidarity of other unions and consumers - the boycotts began when Chavez enlisted Dolores Huerta to follow a shipment of grapes from Schenley Industries (the first grower to be boycotted) to the Port of Oakland. There, Huerta reached out to the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and persuaded them to honor the boycott and refuse to handle non-union grapes. Schenley's grapes started to rot on the docks, cutting them off from the market, and between the effects of union solidarity and growing consumer participation in the UFW's boycotts, the growers started to come under real economic pressure as their revenue dropped despite a record harvest.

Throughout the rest of the Delano grape strike, Dolores Huerta would be the main organizer of the national and internal boycotts, travelling across the country (and eventually all the way to the UK) to mobilize unions and faith groups to form boycott committees and boycott houses in major cities that in turn could educate and mobilize ordinary consumers through a campaign of leafleting and picketing at grocery stores.

Third, the UFW organized the first of its marches, a 300-mile trek from Delano to the state capital of Sacramento aimed at drawing national attention to the grape strike and attempting to enlist the state government to pass labor legislation that would give farmworkers the right to organize. Carefully organized by Cesar Chavez to draw on Mexican faith traditions, the march would be labelled a "pilgrimage," and would be timed to begin during Lent and culminate during Easter. In addition to American flags and the UFW banner, the march would be led by "pilgrims" carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadelupe.

While this strategy was ultimately effective in its goal of influencing the broader Latino community in California to see the UFW as not just a union but a vehicle for the broader aspirations of the whole Latino community for equality and social justice, what became known in Chicano circles as La Causa, the emphasis on Mexican symbolism and Chicano identity contributed to a growing tension with the Filipino half of the UFW, who felt that they were being sidelined in a strike they had started.

Nevertheless, by the time that the UFW's pilgrimage arrived at Sacramento, news broke that they had won their first breakthrough in the strike as Schenley Industries (which had been suffering through a four-month national boycott of its products) agreed to sign the first UFW union contract, delivering a much-needed victory.

As the strike dragged on, growers were not passively standing by - in addition to doubling down on the violence by hiring strikebreakers to assault pro-UFW farmworkers, growers turned to the Teamsters Union as a way of pre-empting the UFW, either by pre-emptively signing contracts with the Teamsters or effectively backing the Teamsters in union elections.

Part of the darker legacy of the Teamsters is that, going all the back to the 1930s, they have a nasty habit of raiding other unions, and especially during their mobbed-up days would work with the bosses to sign sweetheart deals that allowed the Teamsters to siphon dues money from workers (who had not consented to be represented by the Teamsters, remember) while providing nothing in the way of wage increases or improved working conditions, usually in exchange for bribes and/or protection money from the employers. Moreover, the Teamsters had no compunction about using violence to intimidate rank-and-file workers and rival unions in order to defend their "paper locals" or win a union election. This would become even more of an issue later on, but it started up as early as 1966.

Moreover, the growers attempted to adapt to the UFW's boycott tactics by sharing labels, such that a boycotted company would sell their products under the guise of being from a different, non-boycotted company. This forced the UFW to change its boycott tactics in turn, so that instead of targeting individual growers for boycott, they now asked unions and consumers alike to boycott all table grapes from the state of California.

By 1970, however, the growing strength of the national grape boycott forced no fewer than 26 Delano grape growers to the bargaining table to sign the UFW's contracts. Practically overnight, the UFW grew from a membership of 10,000 strikers (none of whom had contracts, remember) to nearly 70,000 union members covered by collective bargaining agreements.

1970 to 1978: The UFW Confronts Internal and External Crises

Up until now, I've been telling the kind of simple narrative of gradual but inevitable social progress that U.S history textbooks like, the Hollywood story of an oppressed minority that wins a David and Goliath struggle against a violent, racist oligarchy through the kind of non-violent methods that make white allies feel comfortable and uplifted. (It's not an accident that the bulk of the 2014 film Cesar Chavez starring Michael Peña covers the Delano Grape Strike.)

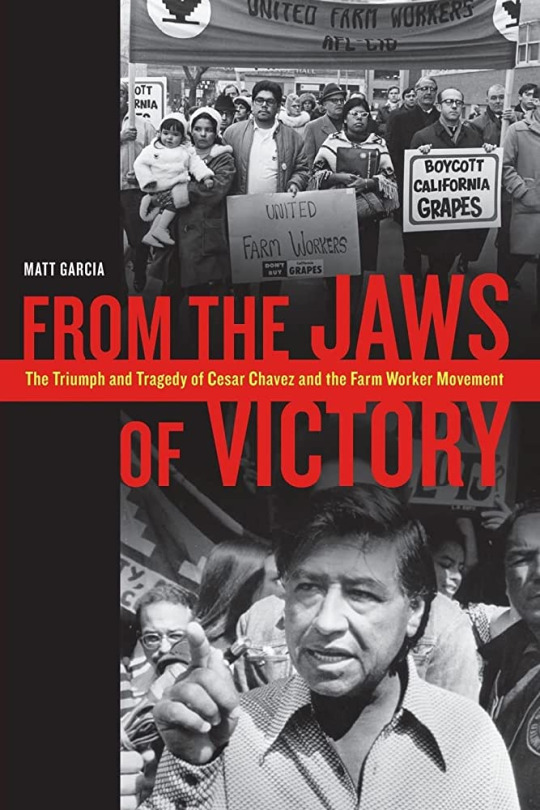

It's also the period in which the UFW's strengths as an organization that came out of the community organizing/civil rights movement were most on display. In the eight years that followed, however, the union would start to experience a series of crises that would demonstrate some of the weaknesses of that same institutional legacy. As Matt Garcia describes in From the Jaws of Victory, in the wake of his historic victory in 1970, Cesar Chavez began to inflict a series of self-inflicted injuries on the UFW that crippled the functioning of the union, divided leadership and rank-and-file alike, and ultimately distracted from the union's external crises at a time when the UFW could not afford to be distracted.

That's not to say that this period was one of unbroken decline - as we'll discuss, the UFW would win many victories in this period - but the union's forward momentum was halted and it would spend much of the 1970s trying to get back to where it was at the very start of the decade.

To begin with, we should discuss the internal contradictions of the UFW: one of the major features of the UFW's new contracts was that they replaced the shape-up with the hiring hall. This gave the union an enormous amount of power in terms of hiring, firing and management of employees, but the quid-pro-quo of this system is that it puts a significant administrative burden on the union. Not only do you have to have to set up policies that fairly decide who gets work and when, but you then have to even-handedly enforce those policies on a day-to-day basis in often fraught circumstances - and all of this is skilled white-collar labor.

This ran into a major bone of contention within the movement. When the locus of the grape strike had shifted from the fields to the urban boycotts, this had made a new constituency within the union - white college-educated hippies who could do statistical research, operate boycott houses, and handle media campaigns. These hippies had done yeoman's work for the union and wanted to keep on doing that work, but they also needed to earn enough money to pay the rent and look after their growing families, and in general shift from being temporary volunteers to being professional union staffers.

This ran head-long into a buzzsaw of racial and cultural tension. Similar to the conflicts over the role of white volunteers in CORE/SNCC during the Civil Rights Movement, there were a lot of UFW leaders and members who had come out of the grassroots efforts in the field who felt that the white college kids were making a play for control over the UFW. This was especially driven by Cesar Chavez' religiously-inflected ideas of Catholic sacrifice and self-denial, embodied politically as the idea that a salary of $5 a week (roughly $30 a week in today's money) was a sign of the purity of one's "missionary work." This worked itself out in a series of internicene purges whereby vital college-educated staff were fired for various crimes of ideological disunity.

This all would have been survivable if Chavez had shown any interest in actually making the union and its hiring halls work. However, almost from the moment of victory in 1970, Chavez showed almost no interest in running the union as a union - instead, he thought that the most important thing was relocating the UFW's headquarters to a commune in La Paz, or creating the Poor People's Union as a way to organize poor whites in the San Joaquin Valley, or leaving the union altogether to become a Catholic priest, or joining up with the Synanon cult to run criticism sessions in La Paz. In the mean-time, a lot of the UFW's victories were withering on the vine as workers in the fields got fed up with hiring halls that couldn't do their basic job of making sure they got sufficient work at the right wages.

Externally, all of this was happening during the second major round of labor conflicts out in the fields. As before, the UFW faced serious conflicts with the Teamsters, first in the so-called "Salad Bowl Strike" that lasted from 1970-1971 and was at the time the largest and most violent agricultural strike in U.S history - only then to be eclipsed in 1973 with the second grape strike. Just as with the Salinas strike, the grape growers in 1973 shifted to a strategy of signing sweetheart deals with the Teamsters - and using Teamster muscle to fight off the UFW's new grape strike and boycott. UFW pickets were shot at and killed in drive-byes by Teamster trucks, who then escalated into firebombing pickets and UFW buildings alike.

After a year of violence, reduced support from the rank-and-file, and declining resources, Chavez and the UFW felt that their backs were up against a wall - and had to adjust their tactics accordingly. With the election of Jerry Brown as governor in 1974, the UFW pivoted to a strategy of pressuring the state government to enact a California Agricultural Labor Relations Act that would give agricultural workers the right to organize, and with that all the labor protections normally enjoyed by industrial workers under the Federal National Labor Relations Act - at the cost of giving up the freedom to boycott and conduct secondary strikes which they had had as outsiders to the system.

This led to the semi-miraculous Modesto March, itself a repeat of the Delano-to-Sacramento march from the 1960s. Starting as just a couple hundred marchers in San Francisco, the March swelled to as many as 15,000-strong by the time that it reached its objective at Modesto. This caused a sudden sea-change in the grape strike, bringing the growers and the Teamsters back to the table, and getting Jerry Brown and the state legislature to back passage of California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

This proved to be the high-water mark for the UFW, which swelled to a peak of 80,000 members. The problem was that the old problems within the UFW did not go away - victory in 1975 didn't stop Chavez and his Chicano constituency feuding with more distinctively Mexican groups within the movement over undocumented immigration, nor feuding with Filipino constituencies over a meeting with Ferdinand Marcos, and nor escalating these internal conflicts into a series of leadership purges.

Conclusion: Decline and Fall

At the same time, the new alliance with the Agricultural Labor Relations Board proved to be a difficult one for the UFW. While establishment of the agency proved to be a major boon for the UFW, which won most of the free elections under CALRA (all the while continuing to neglect the critical hiring hall issue), the state legislature badly underfunded ALRB, forcing the agency to temporarily shut down. The UFW responded by sponsoring Prop 14 in the 1976 elections to try to empower ALRB, and then got very badly beaten in that election cycle - and then, when Republican George Deukmejian was elected in 1983, the ALRB was largely defunded and unable to achieve its original elective goals.

In the wake of Deukmejian, the UFW went into terminal decline. Most of its best organizers had left or been purged in internal struggles, their contracts failed to succeed over the long run due to the hiring hall problem, and the union basically stopped organizing new members after 1986.

#history#u.s history#labor history#ufw#united farm workers#cesar chavez#dolores huerta#trade unions#social history#social movements#unions

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know if the UFW comms worker who posted this knew it or not but this photo is a clear violation of workplace safety standards: that worker is in serious risk of being buried in a potentially deadly trench collapse, because that is a five-foot-some hole that is not secured at all. trench collapses kill dozens of american workers every year, mostly in construction, but ag injuries are notoriously massively underreported. farm workers routinely endure conditions which are not just difficult, but actively dangerous; some of that risk is an information problem (workers don't know they're being asked to do something incredibly risky), but it's mostly a power problem. happy cesar chavez day.

#last study i found about this was 10 years old but it estimated that fully 80% of agricultural injuries are unreported#TRENCH. BOXES.#workplace safety#united farm workers#cesar chavez day is actually 3/31 but i'm posting now please forgive#image described in alt!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christian Paz at Vox:

The first few weeks of Donald Trump’s second presidency have put Democrats in a frustrating bind. He’s thrown so much at them (and at the nation), that they’re having serious trouble figuring out what to respond to — let alone how. He’s signed dozens of executive orders; attempted serious power grabs and overhauls of the government; and signed controversial legislation. And in the process, he’s further divided his opposition, as the Democrats undergo an identity crisis that ramped up after Kamala Harris’s loss.

Immigration policy is a prime example of this struggle: Long before Harris became their nominee, the party was debating just how much to adjust to both Trump’s anti-immigrant campaign promises and to the American public’s general shift away from openness to immigration. Now that he’s in office, Democrats aren’t really lined up to resist every one of the president’s anti-immigrant moves — and some are even backing some of his stances. The party is now divided into roughly three camps: those in the Senate and House willing to back Trump on certain tough-on-immigration measures, like the recently passed Laken Riley Act; those who see their constituents supporting some of his positions but are torn over how to vote; and those progressives who are committed to resisting his every move on immigration. Today’s public opinion is one main contributor for the divide: Americans are still largely in favor of more restrictionist immigration policy. Democratic losses in November are another contributor, particularly in areas with large immigrant or nonwhite populations. But lawmakers are also confronting longer-standing historical dynamics that have divided the working class and immigrants before. Newer and undocumented immigrants can appear to pose both economic competition and threats to existing senses of identity for immigrants who have already resided in the US, or to those who have assimilated and raised new generations. Combined with a resurgent Republican Party that has capitalized on some of these feelings, these facts might be complicating the Democratic response to Trump now.

Working class and immigrant divides aren’t new

On the campaign trail last year, Trump and various other Republican politicians repeated a specific line of reasoning when making a pitch to nonwhite voters: The “border invasion” that Joe Biden and Harris were supposedly responsible for was “crushing the jobs and wages” of Black, Latino, and union workers. Trump called it “economic warfare.” This line of reasoning — that immigrants are taking away economic opportunities from those already in the US — has historically been a source of tension for both native-born Americans, and older immigrants. Much of the economics behind this has been challenged by economists, but the politics are still effective. The main claim here is that an influx in cheaper low-skilled laborers not only pushes down the cost of goods but negatively impacts preexisting American workers by lowering their wages as well. The evidence for this actually happening, however, is thin: Immigrants also create demand, by buying new items and using new services, therefore creating more jobs. Still, the idea remains popular.

Even as far back as the civil rights era, this thinking created divisions among left-wing activist movements trying to secure better labor conditions and legal protections. Take the case of the most iconic figure of the Latino labor movement, César Chávez, himself of Mexican descent. As his movement to secure better conditions for farmworkers faced challenges from nonunion, immigrant workers who could help corporate bosses break or alleviate the pressures of labor strikes, his efforts on immigration took a more radical turn. Chávez’s United Farm Workers even launched an “Illegals Campaign” in the 1970s — an attempt to rally public opposition to immigration and get government officials to crack down on illegal crossings. The UFW even subsidized vigilante patrol efforts along the southern border to try to enforce immigration restrictions when they thought the government wasn’t doing enough, and Chávez publicly accused the federal agency in charge of the border and immigration at the time of abdicating their duty to arrest undocumented immigrants who crossed the border.

Of course, Chávez’s views were nuanced — and primarily rooted in the goal of creating and strengthening a union that could represent and advocate for farmworkers and laborers left out of the labor movements earlier in the 19th and 20th centuries. But they are great examples of the deep roots that economic and identity status threats have in complicating the views of working-class and nonwhite people in the not-too-distant past. This specific opinion has stuck around. Gallup polling since the early 1990s has found that for most of the last 30 years, Americans have tended to hold the opinion that immigration “mostly hurts” the economy by “driving wages down for many Americans.” And swings in immigration sentiment tend to align with how Americans feel about the state and health of the national economy: When economic opportunity feels scarce, as during the post-pandemic inflationary period, Americans tend to pull back from more generous feelings around both legal and illegal immigration.

Democrats also face the challenge of anti-immigrant immigrants

What makes this era of immigration politics perhaps a bit more complicated on top of those existing economic reasons is the added concerns over fairness and orderliness that many nonwhite Americans, and even immigrants from previous generations, feel. US Rep. Juan Vargas, a progressive Democrat who represents San Diego and the part of California that borders Mexico, told me that there’s a sense among some of his constituents that recent immigrants, both legal and not, are cutting the line. This feeling about newcomers not paying their dues is, again, a longstanding sentiment among immigrant groups across American history, but it appears updated for the post-pandemic era. While older immigrants feel they have worked hard and waited their turn, they feel newer ones have taken advantage of the asylum system, or gone through less of a struggle than they have. Vargas told me about a conversation he had with a constituent in his district who told him she disagrees with his stance on immigration policy, even though she once “came across illegally too” and lived in the US for 15 years without documentation. “I started talking to her, and she said, ‘You know, these new immigrants, they get everything. They get here and they get everything. We didn’t get anything, and so I think they should all be deported,’” Vargas said. “I said, ‘Oh, so, because you were given a chance, you don’t think other people should get that same chance?’ She goes, ‘Well, it’s different.’ … Really, in what way? How is it different? … And she didn’t have a very good answer.” Some immigration researchers describe this as part of a “law-and-order” mindset: folding border enforcement and immigration crackdowns with a renewed desire by the public for tough-on-crime policies in the post-pandemic era.

[...] These views help explain why there’s a vocal group of Democrats, including Latino Democrats, willing to work with Trump and Republicans specifically on immigration reforms that take a tough-on-crime approach, like the Laken Riley Act, which expedites deportation for undocumented immigrants charged with certain crimes. Some 46 House Democrats and 12 Senate Democrats ended up voting for the Laken Riley Act, including perhaps the most vocal pro-enforcement Latino Democrat, Sen. Ruben Gallego of Arizona. He argued that the bill represented where the Latino mainstream is now on immigration. “People are worried about border security, but they also want some sane pathway to immigration reform. That’s who I represent. I really represent the middle view of Arizona, which is largely working class and Latino,” Gallego said after the vote. Even some Democrats in solid blue areas of the country agree, to an extent. Democratic Rep. Sylvester Turner, who represents Houston and was an outspoken supporter of immigrant rights during Trump’s first presidency, told me that his constituents back tougher immigration policies, particularly when it comes to undocumented immigrants charged with violent crimes. He himself didn’t vote for the Laken Riley Act because he disagreed with the bill’s application to those merely charged or accused of a crime (as opposed to those convicted), but he said that he feels the public’s mandate to support other kinds of proposals.

[...] They’ll fight back against Trump when he tries to undue birthright citizenship, for example, but they won’t necessarily criticize the continued construction of a border wall with Mexico, or increased deportations. They’ll point out that deportation flights using military aircraft are mostly for show, while standard ICE-chartered planes can do the job for less. Many supported the bipartisan border bill that Biden tried to pass a little less than a year ago, for example, and would theoretically support it again.

[...] And they see room to defend DREAMers, DACA recipients, and those who have benefitted from asylum protections, like temporary protected status, because they see moral value in it, and political value as well: many of those categories of immigrants are popular with Republicans, and polling backs up these nuances.

Vox has a good story on how immigrants who have been here for a long time and those assimilated are opposed to a new arrival of immigrants, and that is hurting the Democratic Party.

#Immigration#Donald Trump#Democratic Party#César Chávez#Scarcity#United Farm Workers#Kamala Harris#2024 Presidential Election#2024 Elections#Laken Riley Act#Economy#US Citizenship#Immigration Reform#Border Security#Border Crisis#US/Mexico Border#Mass Deportations#DREAMers#DACA#TPS#Birthright Citizenship

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

¡Viva La Huelga! ¡Viva Los Campesinos!

Celebrating the life and work of Cesar Chavez, 2024.

#art#artists on tumblr#digital art#vintage#expiremental#design#ufw#cesar chavez#viva la huelga#viva los campesinos#popart#pop art#graphic design#expiremental music#poster art#poster design#vintage posters#united farm workers#si se puede#dolores huerta#philip vera cruz#united farm workers union#cesar chavez day#civil rights#us politics#politics#socialism#communism#leftism#late stage capitalism

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

United Farmworkers of America mural in Modesto, California.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday Feature: Dolores Huerta – The Power of “Sí, Se Puede”

Highlighting the legacy of Dolores Huerta—an icon of resilience and justice. From advocating for farmworkers’ rights to empowering communities, her life’s work reminds us of the power in solidarity and the importance of speaking up. #haveacupofjohanny

This November, as we approach the season of gratitude, let’s take a moment to honor one of the most influential figures in American civil rights history—Dolores Huerta. Known for her tireless advocacy in labor rights, gender equality, and immigrant justice, Huerta has dedicated her life to championing the rights of those often silenced. Her story is a powerful testament to resilience, unity, and…

#civil rights movement#community empowerment#Dolores Huerta#Dolores Huerta Foundation#labor rights activism#Sí Se Puede#Social Justice#trailblazing women#United Farm Workers#women in leadership

0 notes

Text

Joan Baez performs at a benefit concert for the United Farm Workers, Santa Monica, CA, December 16, 1966 © Emmon Clarke.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ernesto is working in one of the dirtiest and lowest paying jobs in Kerman CA. He earns 34 cents for each sheet of raisin he makes and shares “I have to start at dawn to beat the heat and I barely make enough to support my family”. #WeFeedYou

— United Farm Workers (@UFWupdates) September 9, 2024

THIRTY-FOUR CENTS for each sheet of raisins?? 🙁

— Lou Cook (@DeckhandAuthor) September 9, 2024

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reading Recently (Not Necessarily Russian)

Source: “What Ukraine Has Lost,” New York Times, 3 June 2024 Memorial for actor Joachim Gottschalk. When his Jewish wife Meta and son Michael were to be deported, the whole family decided to commit suicide on November 6, 1941. The bronze figure, which was created by Theo Balden in 1967, resembles the actor. It was initially located in a park but had to be moved due to the building of the…

View On WordPress

#Andrew Ford#Austin Frerick#California Gold Rush#Cesar Chavez#childbirth#childcare#Errollyn Wallen#Frank Bardacke#genocide#hog farming#Holocast#ill#illegal immigrants#India Rakusen#Iowa#James Robb#Joachim Gottschalk#Native Americans#New Zealand politics#Te Pāti Māori#The Gated Community (band)#Tom Smouse#Ukraine#United Farm Workers#Zhenya Bruno

0 notes

Text

U.S. health officials in recent months have said the avian flu that's been detected in chickens and cows in some states poses little risk to the general population and to commercial dairy products, but as a third farmworker's diagnosis with the illness was reported Thursday, advocates said officials must do more to protect the laborers who are most at risk.

A farmworker in Michigan was the second person in the state to test positive for H5N1, the avian flu that's currently circulating, and was the first person to report respiratory symptoms. A worker in Texas was also diagnosed with the illness in March and had mild symptoms.

The person whose case was announced Thursday contracted the disease after being exposed to infected cows.

As of late last week, there were 58 cow herds known to be infected across the United States.

The Guardianreported on Wednesday that there have been "anecdotal reports" of other farmworkers exhibiting mild symptoms, and last week federal officials said an unspecified number of people are being "actively monitored" for signs of avian flu, but noted that only 40 people connected to dairy farms had been tested.

Dawn O'Connell, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told reporters on May 22 that authorities are preparing 5 million doses of a vaccine against H5N1, often referred to as bird flu. Offiicals have not yet decided whether shots will be offered to farmworkers when they're deployed later this year.

Elizabeth Strater, director of strategic campaigns for United Farm Workers (UFW), said that while vaccines are being prepared, authorities must ramp up a testing campaign to stop the spread of the virus and protect the country's 150,000 dairy farmworkers.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture unveiled a push earlier this month to encourage workers at affected dairy farms to get tested, offering them a financial incentive of $75.

But with undocumented immigrants who lack health insurance making up a large portion of the agricultural workforce, said Strater, many will likely feel they can't risk testing positive and being required to stay home from work for just $75.

"That's not even a day's lost work," Strater told The Guardian on Wednesday. "And that's a very bad gamble for someone that might miss weeks... They're unlikely to go to the emergency room for anything that isn't life-threatening. In fact, they're avoiding testing because they know they won't get any compensation if they're ordered to stop working."

1 note

·

View note

Text

DOLORES HUERTA // LABOR ACTIVIST

“She is an American labor leader and civil rights activist. She is also the co-founder of the National Farmworkers Association, which later became the United Farm Workers. By boycotting, protesting and lobbying, she worked tirelessly to improve working conditions for immigrant farmworkers and is considered one of the most influential labor activists of the 20th century.”

0 notes