#The Tyburn Sisters

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Rattlebag - The Tyburn Sisters

"A retelling of the supernatural murder ballad ‘Two Sisters,’ set to a traditional Swedish tune (Sörgsen Tön) and presented as part of London’s bloody history. Many miscreants danced the Tyburn Jig beside that infamous stream, buried now but still flowing. The river doesn’t forget." [x]

Two girls both young and fair of face walked by the rushing river One girl, her heart the blackest stone, had grown to hate the other And though she wore a smiling face, she’d fallen far from human grace Her sister she did murder

And by the lonely Tothill Marsh the girl did breathe her last Thrown from the twisting Tyburn's edge into the stream so fast The killer watched her sister drown, smiled as her body floated down Beneath the rushing river

The river hid its guilty face beneath the dirt of ages But hidden deep and far below the angry water rages And on this murdered daughter’s bones there grew the city’s ancient stones One death among so many

And others came to die in time upon the stones of Tyburn Hung from the twisted gallows tree to face a justice stern The blood that flowed into the ground was now the blood of London Town And of that hidden river

Death, plague and dreadful poverty are suffered by the living Still for the restless angry dead there will be no forgiving The seasons pass and bring a fool to build a house at Old King’s School Above the secret river

He dug the soil in that fell place where he had made his home And as he worked he found himself holding the whitest bone He took his blade to carve a horn and from his work a flute was born To sing the song of Tyburn

And from that time, until this day, the only song the flute would play Was of the hidden Tyburn

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think Peter and Tyburn might be my favourite friendship (frenemyship?) in the whole series

#their conversation at the end of hanging tree always brings me to tears#they have such a good time despising each other that they accidentally became friends#and I love tyburns oldest-sisterism so much#cecilia tyburn#lady ty#peter grant#rivers of london#rol

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archive/folklore friends: I am on a "the body/corpse giving evidence" kick (Tyburn sisters, Varulven, the murdered body being made into an instrument that only sings the song of the murder, the tongue telling the tale of the murder), but too depressed to figure out how to search for it properly. Sooooo if anyone has any tips, please lmk

@sanherib @bimbotheosis

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

🪡 + Anne & George Boleyn

apparently the needle sewing thread emoji is not allowed, anymore? this feels hateful, somehow...let me find :

🧵(guess that works): send me + two characters and i’ll talk about their dynamic!

they are best friends, to make no exaggeration. they have close friends, but no one else holds a candle to the closeness of this bond, at the end of the day. they're close enough as children that he thinks of that symmetry once she returns, and they've grown up, it sticks with him: thirteen blue moons apart (1513-21), thirteen steps to her door. he helps her adjust to and navigate court life once she's back, she ensures that he can marry jane (this lays a stepping stone with her future relationship with henry-- they have a formal acquaintance at most, at that juncture, but he asks what had upset jane to the extent that he saw her need to be consoled, she answers about the shortfall of the dowry her father will not accept, and he pays for the remainder...it's a generosity she doesn't easily forget)

they dream together, they joke together, they plan together.

the flip side of this coin is that they both idealize each other to such a degree that they hold each other to higher standards (in morals, success, strength and mistakes) than they do anyone else, and are harder on each other than anyone else. george becomes cruel and intractable towards anyone that he sees as having threatened her honour (and this even, and especially, includes their sister), anne becomes the same towards anyone she views as countermanding him (this is the beginning of her rift with cromwell, and to some degree, even henry).

and they are also not entirely honest with each other. anne doesn't tell him she's afraid until she literally cannot hide it anymore, he didn't tell her of tyburn until it came out in an argument (he's becoming collusive with henry in hiding things from her, and has mixed feelings about it, including guilt, ever since they hid news of the papal decree against them during her first pregnancy), she, if anyone caught it, remained silent (of sorts...) on whether or not she tried to intercede, here:

"I know you, and I know your vision, and I believe that which I had to witness was something you were against. I believe that you spoke against it to the king." Anne does not answer or gesture, other than rubbing her right temple with her first two fingers and latching her gaze onto the frieze that frames the fireplace. "So yes, I believe in you, Anne. But I do not know if I believe your influence with the king is the same as it once was." "You are wrong."

#neverwherewrites#spoilers? sort of.#for the very very last#bcus that is going to come up again; as i've plotted it#once he returns to court and confronts her over the reprieve of mary's estrangement

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Six Sentence Sunday

The first time Beverley really understood that she and her family were truly different from everyone else, was the first time she layed eyes on her niece Olivia and realised that she was utterly ordinary. When Stephen had been born, just two years before, she had been too young, in Tyburn's opinion, to be trusted with him and she’d only caught glimpses of him as he’d been passed back and forth between her older sisters. And even if she had been able to get close to him, at that age it would have been more extraordinary to her if he had been in any way special, having only heard in passing of Father Thames and his sons. Now, at five, stood on her tiptoes and peering inside Olivia’s crib, she wondered why she couldn’t feel the same thing that every other woman in her family radiated coming from the small, wrinkly infant in front of her. Later, much later, she would realise that this difference meant that while she, her mother and her sisters wouldn’t age beyond their own desires, everyone around them still did. But that would come later.

#and it's actually six sentences!#I counted them myself!#rivers of london#beverley brook#anyone shitting on Beverley is getting blocked

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINTS OCTOBER 25 "There is only one tragedy in this life, not to have been a saint."- Leon Bloy

STS. CRISPIN AND CRISPINIAN,MARTYRS

STS. CHRYSANTHUS AND DARIA, MARTYRS ON THE VIA SALARIA NUOVA

St. John Houghton, Roman Catholic Carthusian Monk and Protomartyr of the English Reformation. He refused to swear to the Oath of Supremacy, the first man to make this refusal. Dragged through the streets, he was executed at Tyburn with four companions by being hanged, drawn, and quartered. Parts of his remains were put on display in assorted spots throughout London.

St. John Roberts, Roman Catholic Benedictine Priest and English Martyr. With Blessed Thomas Somers, he was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn.

St. Ambrose Edward Barlow, Roman Catholic Benedictine Priest and English Martyr. he was taken from Lancaster Castle, drawn on a hurdle to the place of execution, hanged, dismembered, quartered, and boiled in oil. His head was afterwards exposed on a pike.

St. Daria, Roman Catholic Martyr. She was stoned and then buried alive. Feastday: October 25

St. Minias of Florence, Roman Catholic Martyred soldier of Florence, Italy, sometimes called Miniato. He was martyred for making converts in the reign of Emperor Trajanus Decius. An abbey near Florence bears his name.

St. Fructus, A hermit whose brother and sister were slain by Muslims in Spain. He and his brother, Valentine, and sister, Engratia, lived in Sepulvida, Spain. When Valentine and Engratia were slain, Fructus became a hermit. All three are patrons of Segovia. Oct 25

St. Marnock. Irish bishop, a disciple of St. Columba. He resided on Jona, Scotland, and is also called Marnan, Marnanus, or Marnoc. He died at Annandale and is revered on the Scottish border. His name was given to Kilmarnock, Scotland.

St. Tabitha, Widow of Joppa, who was mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles (9:36-42) as one who "was completely occupied with good deeds and almsgiving." She fell ill and died and was raised from the dead by St. Peter.

0 notes

Text

W.B Obbly's Obelisk Observer Society (@lyndwyrm0)

John Felton Death and Life Post 💔🗡️

John Felton, who had very kindly decided to strike a swanky pose with the knife before killing Mr Villiers. (Richard Sawyer, 15 May 1830, nearly 200 years after Felton died, so for a corpse, he's looking pretty good here) ^

Felton is a mystery man, possibly born in Suffolk in possibly 1595, but since he didn't slide out the womb with FUTURE ASSASSIN branded across his forehead, no one cares much enough to keep track.

His life continued in obscurity until the 1620s where he is on record for the Cadiz Expedition of 1625, which was backed by Villiers and went about as well as a military operation would go if you were blind folded and had your hands tied together. Plenty died from starvation and disease and the reputation of Villiers was on the decline. Which is fair enough when you consider this killed around 7000 men and lost a handful (62) shops. (Which is more ships lost than Odysseus and you do NOT want to be like Odysseus). I fucking hate Odysseus.

Felton had some in-between gigs but nothing too major until the anglo-french war in which he was rejected to join Villiers fleet. But two months later in August 1627, Villiers said something along the lines of 'yeah go for it' and Felton was off the bench and on the team, now serving as Lieutenant.

BANG CRASH DWOLLOP

it was a fucking nightmare. Not for Felton or Villiers those guys were actually fine but everyone else, not so much. At Saint Martin-De-Re in October the same year, their siege failed (due to poor, planning, poor weapons, terrible ladders, and an all around poor time) and 5000 troops were lost despite retreating. Despite surviving, Felton did not have it easy, his family describes him as a man plagued with nightmares, to quote his sister he was 'much troubled by dreams of fighting'. Which is how I describe myself when someone bids higher than me on eBay and steals the item i desire >:-(

Felton, living in delusion, requested 80 squid and the job role as captain. Having no experience (and no boyfriend who is also the king) he did not get either. This sent him into a rage and on Saturday 23 August 1628, the VILLAIN struck and stabbed Villiers in the chest, killing him.

Genuinely awful picture ^

Now you don't just kill the ex king's (died in 1625) bosom friend and live to tell about it (that's the job of angst poets and teenagers in obelisk observation societies). Though many believed that Felton's actions saved the kingdom and secured Charles Is reign (at least for a bit). But at Tyburn on 29 November 1628, Felton was hung (hanged????) And course, it's quite a bit hard to bounce back from something like that.

He was then moved to Portsmouth (wooo!) And strung in a Gibbet for all to gaze at.

I actually cannot put into words, there are no phrases no single way to explain how much I would do to see this gibbet, the see the Lisk, it's truly unreal. No eBay bidder can out bid my desire on this one.

These two men (erm ignore the malicious ghost) recreated the murder on the 5th September. It was so cool, my heart was racing. I was zazzed, not even over the moon, I was doing laps of it. Unreal. ^

Below is a report from the 1880s

"A relic has been exposed by workmen engaged in erecting the new refreshments and retiring rooms upon Southsea Pier. It is none other than a portion of the veritable gibbet on which the body of the murderer of the Duke of Buckingham was suspended in chains upon Southsea Beach. The murder occurred in 1628. The criminal was hanged at Tyburn, but it was customary to return remains to the scene of the crime. The gibbet bears the Borough arms and a date - but the latter is the day on which it was decided that the gibbet (which was then a well-known landmark) should act as one of the borough boundaries. It is also studded with leaden bullets, from which it would appear that soldiers had been in the habit of discharging their muskets at it. The relic is now lying full length on the pier, but it will be as soon as possible once more erected upon its old site by Mr. Adams, the Borough Engineer. (Later it was replaced by an obelisk)"

The Obelisk, and perhaps the heart of Felton, marked the site from 1782 onwards.

I suppose it must not be all that nice to have your life summarized into just some assassin, and one barely anyone remembers. Felton would only have been in his early thirties when he was killed. :-(

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I thought I would share some portraits/info about notable black men and women who worked and lived in Georgian Britain. This is not an extensive list by any means, and for some figures, portraits are unavailable:

1. Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797) was a writer, abolitionist and former slave. Born into what would become southern Nigeria, he was initially sold into slavery and taken to the Caribbean as a child, but would be sold at least twice more before he bought his freedom in 1766. He decided to settle in London and became involved in the British abolitionist movement in the 1780s. His first-hand account of the horrors of slavery 'The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano' was published in 1789 and it really drove home the horrors of slavery to the general British public. He also worked tirelessly to support freed slaves like himself who experienced racism and inequality living in Britain's cities. He was a leading member of the Sons of Africa, an abolitionist group, whose members were primarily freed black men (the Sons of Africa has been called the first black political organisation in British history). He married an English woman, Susannah, and when he died in 1797, he left his fortune of roughly £73,000 to his daughter, Joanna. Equiano's World is a great online resource for those interested in his life, his work, and his writings.

2. Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780) was a bit of a jack-of-all-trades (he's described as an actor, composer, writer, abolitionist, man-of-letters, and socialite - truly the perfect 18th century gentleman). He was born in the Middle Passage on a slave ship. His mother died not long after they arrived in Venezuela and his father apparently took his own life rather than become a slave. Sancho's owner gave the boy to three sisters living in London c. 1730s (presumably as a sort of pet/servant) but whilst living with them, his wit and intellect impressed the 2nd Duke of Montagu who decided to finance his education. This was the start of Sancho's literary and intellectual career and his association with the elite of London society saw him ascend. He struck up a correspondence with the writer, Laurence Sterne, in the 1760s: Sancho wrote to press Sterne to throw his intellecrual weight behind the cause of abolition. He became active in the early British abolitionist movement and be counted many well-known Georgians amongst his acquaintance. He was also the first black man known to have voted in a British election. He married a West Indian woman and in 1774, opened a grocer's shop in London, that attempted to sell goods that were not produced by slave labour. Despite his popularity in Georgian society, he still recounts many instances of racist abuse he faced on the streets of London in his diaries. He reflected that, although Britain was undoubtedly his home and he had done a lot for the country, he was 'only a lodger and hardly that' in London. His letters, which include discussions of domestic subjects as well as political issues, can be read here.

3. Francis 'Frank' Barber (1742-1801) was born a slave on a sugar plantation in Jamaica. His owner, Richard Bathurst, brought Frank to England when Frank turned 15 and decided to send him to school. The Bathursts knew the writer, Samuel Johnson, and this is how Barber and the famous writer first met (Barber briefly worked as Johnson's valet and found him an outspoken opponent of the slave trade). Richard Bathurst gave Frank his freedom when he died and Frank immediately signed up for the navy (where he apparently developed a taste for smoking pipes). In 1760, he returned permanently to England and decided to work as Samuel Johnson's servant. Johnson paid for Frank to have an expensive education and this meant Frank was able to help Johnson revise his most famous work, 'Dictionary of the English Language.' When Johnson died in 1784, he made Frank his residual heir, bequeathing him around £9000 a year (for which Johnson was criticised in the press - it was thought to be far too much), an expensive gold watch, and most of Johnson's books and papers. Johnson also encouraged Frank to move to Lichfield (where Johnson had been born) after he died: Frank duly did this and opened a draper's shop and a school with his new wife. There, he spent his time 'in fishing, cultivating a few potatoes, and a little reading' until his death in 1801. His descendants still live at a farm in Litchfield today. A biography of Frank can be purchased here. Moreover, here is a plaque erected on the railings outside of Samuel Johnson's house in Gough Square, London, to commemorate Johnson and Barber's friendship.

4. Dido Elizabeth Belle (1764-1801) was born to Maria Belle, a slave living in the West Indies. Her father was Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer. After Dido's mother's death, Sir John took Dido to England and left her in the care of his uncle, Lord Mansfield. Dido was raised by Lord Mansfield and his wife alongside her cousin, Elizabeth Murray (the two became as close as sisters) and was, more or less, a member of the family. Mansfield was unfortunately criticised for the care and love he evidently felt for his niece - she was educated in most of the accomplishments expected of a young lady at the time, and in later life, she would use this education to act as Lord Mansfield's literary assistant. Mansfield was Lord Chief Justice of England during this period and, in 1772, it was he who ruled that slavery had no precedent in common law in England and had never been authorised. This was a significant win for the abolitionists, and was brought about no doubt in part because of Mansfield's closeness with his great-niece. Before Mansfield died in 1793, he reiterated Dido's freedom (and her right to be free) in his will and made her an heiress by leaving her an annuity. Here is a link to purchase Paula Byrne's biography of Dido, as well as a link to the film about her life (starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Dido).

5. Ottobah Cugoano (1757-sometime after 1791) was born in present-day Ghana and sold into slavery at the age of thirteen. He worked on a plantation in Grenada until 1772, when he was purchased by a British merchant who took him to England, freed him, and paid for his education. Ottobah was employed as a servant by the artists Maria and Richard Cosway in 1784, and his intellect and charisma appealed to their high-society friends. Along with Olaudah Equiano, Ottobah was one of the leading members of the Sons of Africa and a staunch abolitionist. In 1786, he was able to rescue Henry Devane, a free black man living in London who had been kidnapped with the intention of being returned to slavery in the West Indies. In 1787, Ottobah wrote 'Thoughts And Sentiments On The Evil & Wicked Traffic Of The Slavery & Commerce Of The Human Species,' attacking slavery from a moral and Christian stand-point. It became a key text in the British abolition movement, and Ottobah sent a copy to many of England's most influential people. You can read the text here.

6. Ann Duck (1717-1744) was a sex worker, thief and highwaywoman. Her father, John Duck, was black and a teacher of swordmanship in Cheam, Surrey. He married a white woman, Ann Brough, in London c. 1717. One of Ann's brothers, John, was a crew-member of the ill-fated HMS Wager and was apparently sold into slavery after the ship wrecked off the coast of Chile on account of his race. Ann, meanwhile, would be arrested and brought to trial at least nineteen times over the course of her lifetime for various crimes, including petty theft and highway robbery. She was an established member of the Black Boy Alley Gang in Clerkenwell by 1742, and also quite frequently engaged in sex work. In 1744, she was given a guilty verdict at the Old Bailey after being arrested for a robbery: her trial probably wasn't fair as a man named John Forfar was paid off for assisting in her arrest and punishment. She was hanged at Tyburn in 1744. Some have argued that her race appears to have been irrelevant and she experienced no prejudice, but I am inclined to disagree. You can read the transcript of one of Ann Duck's trials (one that resulted in a Not Guilty verdict) here. Also worth noting that Ann Duck is the inspiration behind the character Violet Cross in the TV show 'Harlots.'

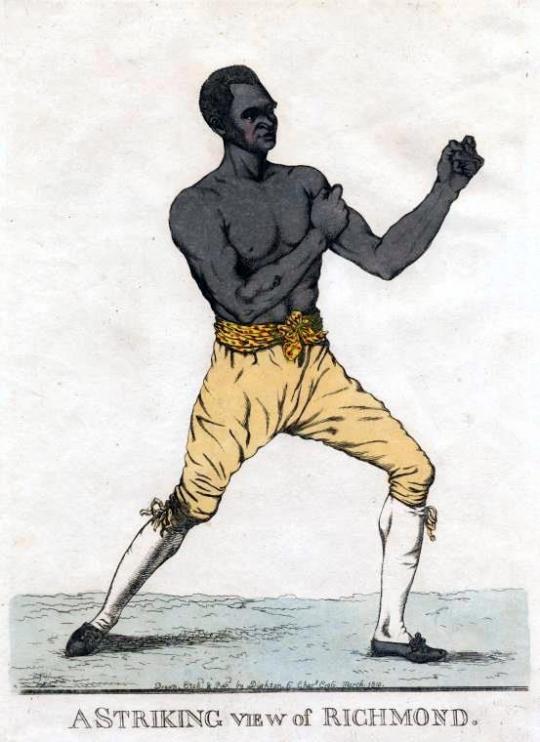

7. Bill Richmond (1763-1829) was a prize winning bare-knuckle boxer of the late 18th and early 19th century. He was born a slave in New York (then part of British America) but moved permanently to England in 1777 where he was most likely freed and received an education. His career as a boxer really took of in the early 19th century, and he took on all the prize fighters of the time, including Tom Cribb and the African American fighter, Tom Molineaux. Richmond was a sporting hero, as well as fashionable in his style and incredibly intelligent, making him something of a celebrity and a pseudo-gentleman in his time. He also opened a boxing academy and gave boxing lessons to gentlemen and aristocrats. He would ultimately settle in York to apprentice as a cabinet-maker. Unfortunately, in Yorkshire, he was subject to a lot of racism and insults based on the fact he had married a white woman. You can watch a Channel 4 documentary on Richmond here: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

8. William Davidson (1781-1820) was the illegitimate son of the Attorney General of Jamaica and a slave woman. He was sent to Glasgow in Scotland to study law at the age of 14 and from this period until 1819, he moved around Britain and had a number of careers. Following the Peterloo Massacre in 1819, Davidson began to take a serious interest in radical politics, joining several societies in order to read radical and republican texts. He also became a Spencean (radical political group) through his friendship with Arthur Thistlewood and would quickly rise to become a leading member of the group. In 1820, a government provocateur tricked Davidson and other Spenceans, into being drawn into a plot to kill the Earl of Harrowby and other government cabinet officers as they dined at Harrowby's house on the 23rd February. This plot would become known as the Cato Street Conspiracy (named thus because Davidson and the other Spenceans hid in a hayloft in Cato Street whilst they waited to launch their plan). Unfortunately, this was a government set up and eleven men, including Davidson, were arrested and charged with treason. Davidson was one of five of the conspirators to not have his sentence commuted to transportation and was instead sentenced to death. He was hanged and beheaded outside of Newgate Prison in 1820. There is a book about the Cato Street Conspiracy here.

9. Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (1705-1775) was born in the Kingdom of Bornu, now in modern day Nigeria. As the favourite grandson of the king of Zaara, he was a prince. Unfortunately, at the age of 15, he was sold into slavery, passing first to a Dutch captain, then to an American, and then finally to a Calvinist minister named Theodorus Frelinghuysen living in New Jersey. Frelinghuysen educated Gronniosaw and would eventually free him on his deathbed but Gronniosaw later recounted that when he had pleaded with Frelinghuysen to let him return to his family in Bornu, Frelinghuysen refused. Gronniosaw also remembered that he had attempted suicide in his depression. After being freed, Gronniosaw set his sights on travelling to Britain, mainly to meet others who shared his new-found Christian faith. He enlisted in the British army in the West Indies to raise money for his trip, and once he had obtained his discharge, he travelled to England, specifically Portsmouth. For most of his time in England, his financial situation was up and down and he would move from city to city depending on circumstances. He married an English weaver named Betty, and the pair were often helped out financially by Quakers. He began to write his life-story in early 1772 and it would be published later that year (under his adopted anglicised name, James Albert), the first ever work written by an African man to be published in Britain. It was an instant bestseller, no doubt contributing to a rising anti-slavery mood. He is buried in St Oswald's Church, Chester: his grave can still be visited today. His autobiography, A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself, can be read here.

10. Mary Prince (1788-sometime after 1833) was born into slavery in Bermuda. She was passed between several owners, all of whom very severely mistreated her. Her final owner, John Adams Wood, took Mary to England in 1828, after she requested to be able to travel as the family's servant. Mary knew that it was illegal to transport slaves out of England and thus refused to accompany Adams Wood and his family back to the West Indies. Her main issue, however, was that her husband was still in Antigua: if she returned, she would be back in enslavement, but if she did not, she might never see her husband again. She contacted the Anti-Slavery Society who attempted to help her in any way they could. They found her work (so she could support herself), tried tirelessly to convince Adams Wood to free her, and petitioned parliament to bring her husband to England. Mary successfully remained in England but it is not known whether she was ever reunited with her husband. In 1831, Mary published The History of Mary Prince, an autobiographical account of her experiences as a slave and the first work written by a black woman to be published in England. Unlike other slave narratives, that had been popular and successful in stoking some anti-slavery sentiment, it is believed that Mary's narrative ultimately clinched the goal of convincing the general British population of the necessity of abolishing slavery. Liverpool's Museum of Slavery credits Mary as playing a crucial role in abolition. You can read her narrative here. It is an incredibly powerful read. Mary writes that hearing slavers talk about her and other men and women at a slave market in Bermuda 'felt like cayenne pepper into the fresh wounds of our hearts.'

#18th century history#georgian britain#black history#olaudah equiano#ignatius sancho#francis barber#dido elizabeth belle#ottonah cugoano#ann duck#bill richmond#william davidson#uksawsaw gronniosaw#mary prince

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Summer reading: from missing lighthouse keepers to the healing power of trees...

50 new fiction and nonfiction books to enjoy. Plus recent paperbacks to pack and the best children’s stories!

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

What is the internet doing to our minds and hearts? The American comic memoirist’s first novel, shortlisted for the Women’s prize, begins as a savagely witty deep dive into the black hole of social media, then confronts real-life tragedy and transcendence.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

Klara, the “artificial friend” to sickly teenager Josie, is our naive guide through Ishiguro’s uneasy near-future, in which AI and genetic enhancement threaten to create a human underclass. Klara’s quest to understand the people and systems around her, and to protect Josie at all costs, illuminates what it means to love, to care – to be human.

Luster by Raven Leilani

This Dylan Thomas prize winner introduces a brilliant new voice. Edie is a young black woman in New York who starts a relationship with an older white man, and gets complicatedly close to his wife and adopted black daughter. The sentences crackle in a virtuosic skewering of race, precarious modern living and the generation gap.

That Old Country Music by Kevin Barry

The third short-story collection from a stylist to savour brings more exhilarating, darkly witty tales of oddballs yearning after love and enchantment in the wild west of Ireland.

The Lamplighters by Emma Stonex

Based on a real-life mystery, this stylishly written debut interweaves a range of voices to explore the disappearance of three Cornish lighthouse keepers in 1972. Both a slow-growing, atmospheric portrait of claustrophobic relationships and a relentless page-turner, this is a hugely satisfying read and a passionate love letter to the sea.

The Great Mistake by Jonathan Lee

A deeply enjoyable panoramic novel about gilded age New York, which explores the transformation of the city through the life and sudden death of the man who built Central Park.

Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason

This account of a life derailed by mental illness is both darkly funny and deeply touching. Martha looks back on her failed marriage to Patrick, a family friend, but the real love story in this novel, billed as “Fleabag meets Patrick Melrose”, is with her wry sister, Ingrid.

How to Kidnap the Rich by Rahul Raina

Written with enormous verve and energy, this crime caper satirising aspiration, inequality and corruption in India centres on an “examinations consultant” who fraudulently acquires qualifications for the children of the wealthy. Fast, furious and lots of fun.

Second Place by Rachel Cusk

A stranger comes to stay in this fascinating, uncomfortable exploration of creativity, the male gaze and the gendered experience of freedom. Cusk’s story of a female writer’s power struggle with a male artist is one of the first novels to take inspiration from lockdown.

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson

A young author’s tender debut about a contemporary London love affair explores race, sex and masculinity, as well as being a joyous hymn to black art and culture.

A Net for Small Fishes by Lucy Jago

Described as “the Thelma and Louise of the 17th century” and based on a real-life scandal at the court of James VI and I, this irresistibly immersive novel follows a friendship between two women that leads to Tyburn and the Tower.

Civilisations by Laurent Binet, translated by Sam Taylor

In this hugely entertaining counterfactual history of the making of the modern world, it’s the Incas who invade Europe. Binet has riotous, brainy fun in a rollicking story of the urge to power, which delights in turning received ideas upside down.

Girl A by Abigail Dean

The premise of this thriller debut – that “Girl A” is the sibling who escaped incarceration by abusive parents in a “house of horrors” – may sound overly grim, but this is a carefully judged and propulsive story of survival and redemption, as Lex comes to terms with her past.

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris

“Get Out meets The Devil Wears Prada”: in this buzzy, up-to-the-minute debut, twentysomething Nella is pleased to no longer be the only black employee in her New York publishing company when new recruit Hazel joins her desk. But then things get sinister … A twisty, darkly comic satire of office culture, identity politics and white expectations.

Light Perpetual by Francis Spufford

Spufford follows his 18th-century romp Golden Hill with a brilliantly achieved interweaving of working-class lives in postwar south London. The book’s metaphysical conceit – that the children whose stories he spins, from the blitz into the 21st century, died when a German bomb dropped on Woolworths – infuses this tale of the miracle of everyday existence with an elegiac profundity.

The Absolute Book by Elizabeth Knox

A magical book; doors between worlds; talking birds, vicious fairies and a trip to Purgatory ... Stuffed with literary allusion and mythic echoes from the Norse legends to Alan Garner, straddling dimensions and hopping genres with ease, this is a capacious, one-of-a-kind fantasy novel that’s worth getting lost in.

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

A short, sharp shock of a novel that anatomises a toxic relationship between mother and daughter. Riley’s icy style and uncanny ear for dialogue create unflinching prose that is funny and devastating by turns.

Daughters of Night by Laura Shepherd-Robinson

This intricately written and absorbing historical crime thriller spans all levels of Georgian London, as a woman with her own secrets investigates a murder in Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens.

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

Shortlisted for the Women’s prize, this follow-up to Homegoing confirms Gyasi’s blazing talent. Focusing on a family who emigrate from Ghana to the deep south in the US, it’s an investigation of science and faith, addiction and ambition, and the way trauma is passed down the generations.

In. by Will McPhail

The debut graphic novel from the New Yorker cartoonist is a beautiful, bittersweet portrait of modern life, with black and white panels bursting into sublime colour when isolated hipster Nick makes a genuine connection with others. McPhail is very funny on urban coffee-shop existence – “croissants aren’t making me happy any more” – but his tragicomedy will also make the heart swell.

Luckenbooth by Jenni Fagan

An Edinburgh tenement building is haunted by tall stories and unnerving strangers, from William Burroughs to the devil’s daughter, in this weird and wonderful gothic confection.

The Manningtree Witches by AK Blakemore

Based on documents from the time, a striking debut about the women victimised in the 17th-century Essex witch trials that is both an amazingly fresh historical novel and a timeless meditation on the male abuse of power.

A River Called Time by Courttia Newland

A speculative epic of parallel Londons, set in a world where colonialism and slavery never happened, enables a superhero story that’s thought-provoking as well as action-packed.

The Rules of Revelation by Lisa McInerney

The rollercoaster conclusion to the Women’s prize-winning “unholy trinity” of big-hearted, sharp-mouthed novels set amid Cork’s seamy underbelly. A sideways look at modern Ireland, and a comic treat.

The Passenger by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, translated by Philip Boehm

This year’s essential literary rediscovery was written as darkness descended in Nazi Germany. With the nightmarish absurdism of Kafka and the pace of a thriller, it follows a German-Jewish businessman’s attempts to flee the country: tense, terrifying and still horribly relevant today.

This One Sky Day by Leone Ross

Gloriously inventive magic realism set over a single day on a fictional Caribbean archipelago, where every inhabitant has a touch of supernatural power. Whimsy, romance, erotica and adventure collide in a literary feast for the senses.

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

A soaring epic of female adventure and wanderlust that ranges across decades and continents, from the early 20th century to the 21st, as a Hollywood star investigates the mysterious disappearance of an early aviator.

Slough House by Mick Herron

Spymaster Jackson Lamb may be getting a little cartoonish in this latest outing for the screwups and rejects of MI5, but Herron’s bone-dry farce of corruption and intrigue remains as delicious as ever.

Animal by Lisa Taddeo

Taddeo follows a nonfiction investigation of female desire, Three Women, with an excoriating debut novel that puts female rage in the spotlight. Her transgressive antiheroine, making a US road trip of revenge and self-discovery, is a wisecracking voice to relish (out on 24 June).

The Startup Wife by Tahmima Anam

In this sparky satire of startup culture and the modern search for meaning, a computer scientist who launches a social media app with her husband has to find her own voice, both in the boardroom and her marriage. Smart and funny on culture clashes, male-female dynamics and the cult of wellness.

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders

Why is fiction important and what makes a great story? The Booker winner teaches Russian literature at Syracuse University in the US and this enjoyable collection of essays channels that expertise, diving into classic short stories by Chekhov, Tolstoy and Gogol. A masterclass from a warm and engagingly enthusiastic companion.

Real Estate by Deborah Levy

The concluding book in Levy’s “living autobiography” trilogy sees her travelling between London, New York, Mumbai and Paris reflecting on creativity, security and what makes a home as she approaches her 60th birthday. Witty, honest and hypnotically allusive, this brilliantly crafted memoir interrogates women’s quest for artistic and emotional freedom.

Rememberings by Sinéad O’Connor

From childhood thieving to publicly ripping up a picture of the Pope, O’Connor is known for sticking two fingers up at authority. This unapologetic account of her rollercoaster life and career is full of heart, humour and cameos from figures such as Prince, or as she calls him “ol fluffy cuffs”.

Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain by Sathnam Sanghera

A concise, well researched and accessible primer to a history too often whitewashed or overlooked, Empireland shows how the legacy of our colonial past saturates so much of the “Britishness” that we take for granted today.

Breathtaking: Inside the NHS in a Time of Pandemic by Rachel Clarke

Written from the frontline of history – at nights, on a palliative care ward – this is a book filled with rage and compassion that should become required reading for anyone considering a career in medicine or politics.

Fall: The Mystery of Robert Maxwell by John Preston

In an entertaining account of the life and death of Robert Maxwell, the author of A Very English Scandal charts the press baron’s vast appetites, ambition and feud with Rupert Murdoch. It ends with the man Private Eye nicknamed “the bouncing Czech” emptying the Mirror pension fund before disappearing from his yacht, the Lady Ghislaine – named after the now equally infamous youngest of his nine children.

The Secret to Superhuman Strength by Alison Bechdel

If you’ve never read a deeply personal, stomach-shakingly funny, existential graphic memoir about exercise, mortality and self-improvement, start with this one by the talented artist behind Fun Home.

In the Thick of It: The Private Diaries of a Minister by Alan Duncan

Some politicians’ diaries disappoint by pulling their punches and offering little in the way of political gossip. This isn’t one of them. Duncan describes Gavin Williamson as a “venomous self-seeking little shit”, Priti Patel a “brassy monster”, and Michael Gove an “unctuous freak”. And that’s to say nothing of Boris Johnson and Brexit …

The Hard Crowd: Essays 2000-2020 by Rachel Kushner

In a collection spanning 20 years, Kushner is as sharp writing about partying as politics, cultural history or motorbike racing. To a great writer, everything is copy, and Kushner has a more interesting life to draw on than most.

The Heartbeat of Trees: Embracing Our Ancient Bond with Forests and Nature by Peter Wohlleben

A simultaneously stimulating and soothing blend of nature writing and science, this detailed examination of the consciousness of trees may disappoint readers who want to commune with the forest, but strongly encourages tree hugging for our own, human sake.

I Belong Here: A Journey Along the Backbone of Britain by Anita Sethi

After she was subjected to a racist attack on a train, Mancunian writer Sethi was left anxious, claustrophobic and longing for open spaces. This account of her pilgrimage across the Pennines explores ideas of estrangement, home and belonging.

Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen

In the darkest days of the pandemic last year came news that the former children’s laureate was seriously ill with Covid. This affecting anthology is his attempt to piece together the 47 days he spent in intensive care. Darkly funny poems sit alongside messages from his wife, Emma, and extracts from his “patient’s diary” recorded by the nurses and care workers who saved his life.

Ancestors: A Prehistory of Britain in Seven Burials by Alice Roberts

A winning combination of groundbreaking genetic science and real, human empathy, this exploration of seven burial sites explains who we are and how we came to be here.

One of Them: An Eton College Memoir by Musa Okwonga

An elegantly crafted memoir that weaves together the two strands of Okwonga’s early life takes in the rise of the far right in his mostly white, working-class hometown and his time at Eton. The result is a unique insight into race and class in Britain today.

The Sleeping Beauties: And Other Stories of the Social Life of Illness by Suzanne O’Sullivan

Some people call it mass hysteria; some grisi siknis (crazy sickness) or “mass psychogenic illness”. What neurologist O’Sullivan makes clear, in this fascinating and compassionate account, is that these illnesses are real, that they sometimes allow voiceless people to make themselves heard and that, with the right support, those people can be helped.

From Spare Oom to War Drobe: Travels in Narnia with My Nine-Year-Old Self by Katherine Langrish

A wonderful companion to CS Lewis’s Narnia novels, which captures the magic of books as a doorway into other worlds while also thoughtfully exploring Lewis’s religious didacticism.

How to Make the World Add Up: Ten Rules for Thinking Differently About Numbers by Tim Harford

As presenter of Radio 4’s More or Less, Harford is a calm voice in the often confusing and clamorous world of statistics. With its 10 simple rules for understanding numbers, this book demystifies maths and gives its power back to the people, taking away the advantage from those who would use statistics to bamboozle us.

Stronger: Changing Everything I Knew About Women’s Strength by Poorna Bell

Bell took up powerlifting after the death of her husband and can now lift more than twice her own body weight. In this defiant and reflective memoir she examines ideas around women and strength, resulting in a challenging, positive and powerful call to arms. Muscled arms.

Helgoland by Carlo Rovelli, translated by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell

Travelogue meets biography meets a masterful explanation of quantum theory in this warm and fascinating account of what happened when young Werner Heisenberg went to Helgoland in 1925.

All the Young Men: A Memoir of Love, Aids and Chosen Family in the American South by Ruth Coker Burks

A perfect real-life counterpoint to Russell T Davies’s It’s a Sin, All the Young Men recalls how Burks held hands, cooked meals and fought for care for hundreds of men stigmatised and abandoned as they died of Aids. It’s a tender and bracing reminder of all-too-recent history.

Pandora’s Jar: Women in the Greek Myths by Natalie Haynes

Pandora didn’t have a box – and that’s just one of the things you’ll learn from this funny, geeky guide to Greek myth by the standup classicist.

Explaining Humans: What Science Can Teach Us about Life, Love and Relationships by Camilla Pang

A writer with autism spectrum disorder uses scientific concepts to help her understand human behaviour – and other humans have a lot to learn from her about both.

Agent Sonya by Ben Macintyre

The stranger-than-fiction story of Ursula Kuczynski, a 20th-century secret agent whose remarkable work changed the course of history.

Thinking Again by Jan Morris

A collection of diary entries, this last book by the celebrated travel writer shows a remarkable mind, a generous spirit and an imagination undimmed.

Bessie Smith by Jackie Kay

Originally published in 1997, this richly inventive biography details the Scottish poet’s lifelong love affair with a “libidinous, raunchy, fearless blueswoman”.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

This family saga about black twins in the US, one of whom takes on a white identity, has been a critical and commercial smash.

Summer by Ali Smith

The triumphant conclusion to Smith’s seasonal quartet explores the biggest themes – war, love, family, climate, art – with wit and heart.

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

Soaked in love, agony and booze, the Booker-winning tale of a young boy and his alcoholic mother in 1980s Glasgow.

The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman

The Pointless host’s all-conquering crime debut is a cosy caper in an upmarket retirement village.

The Dangers of Smoking in Bed by Mariana Enríquez, translated by Megan McDowell

Shortlisted for the International Booker, unsettling ghost stories from the Argentinian author.

Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers

A virgin birth in postwar south London? This wry, witty tale of a stifled journalist finding new horizons as she investigates an unlikely claim is a bittersweet treat.

The Gospel of the Eels: A Father, a Son and the World’s Most Enigmatic Fish by Patrik Svensson

A gorgeously evocative blend of science, nature writing and family memoir that explores a father-son relationship – and eels.

Wild Child: A Journey Through Nature by Dara McAnulty, illustrated by Barry Falls

From the prize-winning young naturalist, this is a dreamy dive into the natural world to thrill wildlife fans of six-plus.

Good News: Why the World Is Not as Bad as You Think by Rashmi Sirdeshpande, illustrated by Adam Hayes

Learn to spot fake news and celebrate the best of humanity in this mood-lifting global overview for readers of seven and up.

Noah’s Gold by Frank Cottrell-Boyce, illustrated by Steven Lenton

What happens when a school trip leaves six kids stranded on an island – and the entire internet is turned off? A gently funny story for eight-plus, with a warm, classic feel.

The House of Serendipity by Lucy Ivison, illustrated by Catharine Collingridge

Scandalous secrets meet riotous hilarity in this glorious 1920s-set romp starring a young dressmaking duo, perfect for readers of nine to 12.

Starboard by Nicola Skinner, illustrated by Flavia Sorrentino

An escaped steamship, estranged best friends, a talking map and a fabulous voyage add up to a thrillingly original story for 10-plus.

Something I Said by Ben Bailey Smith

Smart young comedian Carmichael Taylor is on a journey of self-discovery – from trouble at school to American TV star (maybe). Witty and touching, this book is ideal for 10-plus readers who love wordplay and wild, looping tangents.

You’re the One That I Want by Simon James Green

Shy, ordinary Freddie is terrified of auditioning for Grease, but gorgeous newcomer Zach seems determined to seduce him in the props cupboard. A hilariously rude, sweetly addictive YA romance.

Ace of Spades by Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé

Only two black students attend an exclusive US high school – and now an anonymous texter is trying to destroy their reputations in this tense, compelling YA thriller that will appeal to fans of Karen McManus.

House of Hollow by Krystal Sutherland

Three sisters vanished as children and came back strangely changed. Now Grey, the eldest, has vanished again. Can she be saved once more? A gorgeous, grisly modern fairytale for 14-plus.

Bad Habits by Flynn Meaney

When rebel girl Alex sets out to stage The Vagina Monologues at her Catholic boarding school, she’s hoping to be expelled – but things don’t go according to plan. A frank, feminist and outrageously funny YA novel.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catherine Howard (c. 1523 – 13 February 1542) was queen consort of England from 1540 until 1541 as the fifth wife of Henry VIII. She was the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard and Joyce Culpeper, cousin to Anne Boleyn (the second wife of Henry VIII), and niece to Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk. Thomas Howard was a prominent politician at Henry's court, and he secured her a place in the household of Henry's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves, where she caught the King's interest. She married him on 28 July 1540 at Oatlands Palace in Surrey, just 19 days after the annulment of his marriage to Anne. He was 49, and she was still a teenager, at about 17 years old.

Catherine was one of the daughters of Lord Edmund Howard (c. 1478 – 1539) and Joyce Culpeper (c. 1480 – c. 1528). Her father's sister, Elizabeth Howard, was the mother of Anne Boleyn. Therefore, Catherine Howard was the first cousin of Anne Boleyn, and the first cousin once removed of Lady Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth I), Anne's daughter by Henry VIII. She also was the second cousin of Jane Seymour, as her grandmother Elizabeth Tilney was the sister of Seymour's grandmother Anne Say. As a granddaughter of Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk (1443–1524), Catherine had an aristocratic pedigree. Her father was not wealthy, being the third son among 21 children and disfavoured in the custom of primogeniture, by which the eldest son inherits all his father's estate.

Catherine was sent with some of her siblings to live in the care of her father's stepmother, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk. The Dowager Duchess presided over large households at Chesworth House in Horsham in Sussex, and at Norfolk House in Lambeth where dozens of attendants, along with her many wards—usually the children of aristocratic but poor relatives—resided. While sending young children to be educated and trained in aristocratic households other than their own was common for centuries among European nobles, supervision at both Chesworth House and Lambeth was apparently lax. The Dowager Duchess was often at Court and seems to have had little direct involvement in the upbringing of her wards and young female attendants.

As a result of the Dowager Duchess's lack of discipline, Catherine became influenced by some older girls who allowed men into the sleeping areas at night for entertainment. The girls were entertained with food, wine, and gifts stolen from the kitchens. Catherine was not as well educated as some of Henry's other wives, although, on its own, her ability to read and write was impressive enough at the time. Her character has often been described as vivacious, giggly and brisk, but never scholarly or devout. She displayed great interest in her dance lessons, but would often be distracted during them and make jokes. She also had a nurturing side for animals, particularly dogs.

In the Duchess's household at Horsham, in around 1536, Catherine began music lessons with two teachers, one of whom was Henry Mannox. Mannox's exact age is unknown; although it has recently been stated that he was in his late thirties, perhaps 36, at the time, this is not supported by Catherine's biographers. Evidence exists that Mannox was not yet married, which would be highly unusual for someone from his background at the time to have reached mid-thirties without being married - he married sometime in the late 1530s, perhaps 1539, and there is also some evidence that he was of an age with two other men serving in the household, including his cousin Edward Waldegrave (who was in his late teens or early twenties from 1536-8). These pieces of evidence indicate that Mannox too was in his early to mid-twenties in 1538.

Catherine's uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, found her a place at Court in the household of the King's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. As a young and attractive lady-in-waiting, Catherine quickly caught Henry's eye. The King had displayed little interest in Anne from the beginning, but on Thomas Cromwell's failure to find a new match for Henry, Norfolk saw an opportunity. The Howards may have sought to recreate the influence gained during Anne Boleyn's reign as queen consort. According to Nicholas Sander, the religiously conservative Howard family may have seen Catherine as a figurehead for their fight by expressed determination to restore Roman Catholicism to England. Catholic Bishop Stephen Gardiner entertained the couple at Winchester Palace with "feastings".

As the King's interest in Catherine grew, so did the house of Norfolk's influence. Her youth, prettiness and vivacity were captivating for the middle-aged sovereign, who claimed he had never known "the like to any woman". Within months of her arrival at court, Henry bestowed gifts of land and expensive cloth upon Catherine. Henry called her his 'very jewel of womanhood' (that he called her his 'rose without a thorn' is likely a myth). The French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, thought her "delightful". Holbein's portrait showed a young auburn-haired girl with a characteristically hooked Howard nose; Catherine was said to have a "gentle, earnest face." King Henry and Catherine were married on 28 July 1540, the same day Cromwell was executed. She was a teenager and he was 49. Catherine adopted the motto, Non autre volonté que la sienne or "No other wish but his" using the English translation from French.

Catherine may have been involved during her marriage to the King with Henry's favorite male courtier, Thomas Culpeper, a young man who "had succeeded him in the Queen's affections", according to Dereham's later testimony. She had considered marrying Culpeper during her time as a maid-of-honor to Anne of Cleves. Culpeper called Catherine "my little, sweet fool" in a love letter. It has been alleged that in the spring of 1541 the pair were meeting secretly. Their meetings were allegedly arranged by one of Catherine's older ladies-in-waiting, Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford the widow of Catherine's executed cousin, George Boleyn, Anne Boleyn's brother.

Culpeper and Dereham were arraigned at Guildhall on 1 December 1541 for high treason. They were executed at Tyburn on 10 December 1541, Culpeper being beheaded and Dereham being hanged, drawn and quartered. According to custom, their heads were placed on spikes atop London Bridge. Catherine was beheaded with a single stroke of the executioner's axe.

Lady Rochford was executed immediately thereafter on Tower Green. Both bodies were buried in an unmarked grave in the nearby chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, where the bodies of Catherine's cousins Anne and George Boleyn also lay.

*some portraits here are not of Catherine. The only one known to survive is done by Hans Holbein the younger.

#women in history#tudor portraits#tudor england#the tudors#tudors#tudor#henry tudor#anne of cleves#queen catherine#katherine howard#catherine howard#queen of england#house of horward#house of tudor#england#six wives#portrait of a woman#women fashion#women#history of women

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

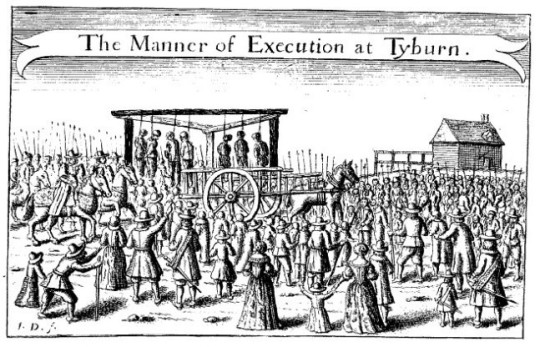

Ballads of the Hanged: Swinging from the Gallows Tree

A mixtape of execution ballads and assorted tales of guilt, wrath, terror, and defiance on the gallows, where all men are brothers.

[on spotify]

21 tracks, 1h 15min in full (spotify lacks one song)

I teased this many moons ago, and I finally finished it. No booklet in PDF form (too much hassle), but I got extensive liner notes, which you can also read here, for more pictures and a wider format. Enjoy!

LINER NOTES

1. Hans Zimmer - Hoist The Colours

Heave ho thieves and beggars never shall we die

What a heartbreaking thing to say on the scaffold. But we have to start with theatrics and a drum roll, and our introduction needs no introduction.

2007, from Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End OST lyrics: Ted Elliott & Terry Rossio music: Hans Zimmer & Gore Verbinski

2. Shirley Collins - Tyburn Tree (Since Laws Were Made)

Next stop, Tyburn: England's most notorious gallows. In The Beggar's Opera, the highwayman Macheath (later also known as Mack the Knife) observes that if they hanged rich criminals like they hang the poor ones, "'twould thin the land". Shirley Jackson subtly changed this to the better.

Since laws were made for ev'ry degree to curb vice in others as well as me, I wonder there's no better company on Tyburn Tree.

But since gold from laws can take out the sting, and if rich men like us were to swing, it would rid the land their numbers to see upon Tyburn Tree.

recorded 1966, released 2002 in Within Sound lyrics: John Gay, from The Beggar's Opera, 1728 music: traditional ("Greensleeves"), 16th century

3. Joan Baez - Long Black Veil

A country ballad about a man falsely accused of murder, who lets himself get dragged to the gallows because he won't reveal his alibi: an affair with his best friend's wife. It's been covered by a million people, here's Baez live.

The scaffold is high, eternity near, She stands in the crowd, she sheds not a tear, But sometimes at night, when the cold winds moan, In a long black veil she cries o'er my bones.

1963, from In Concert Part 2 lyrics & music: Lefty Frizzell, 1959

4. Oscar Isaac with Punch Brothers & Secret Sisters - Hang Me, Oh Hang Me

A poor boy who got "so damn hungry he could hide behind a straw", made his last stand with a rifle and a dagger, and has been all around this world, and is positively done with it.

They put the rope around my neck, they hung me up so high Last words I heard 'em say, won't be long now 'fore you die Hand me, oh hang me, and I'll be dead and gone Wouldn't mind the hanging, but the laying in the grave so long

2015, from Another Day, Another Time: Celebrating the Music of "Inside Llewyn Davis", after Oscar Isaac's rendition in Inside Llewyn Davis, 2013, in turn after Dave Van Ronk's rendition in Folksinger, 1962 lyrics & music: traditional American/unclear origin, folk song with various titles (I've Been All Around This World, The Gambler, My Father Was a Gambler, The New Railroad), first recorded by Justis Begley, 1937

5. Chapel Hill - Seven Curses

Cover of a Bob Dylan song, telling us the dark tale of a judge who's about to send a man to the gallows for stealing a horse, promises his daughter he'll show clemency if she agrees to sleep with him, and then reneges on his promise.

The next morning she had awoken to know that the judge had never spoken she saw that hanging branch a-bending she saw her father's body broken These be seven curses for a judge so cruel

2013, from One For The Birds lyrics inspired by Judy Collins's "Anathea" (1963), in turn inspired by the traditional Hungarian ballad "Feher Anna", who curses the judge "thirteen years may be lie bleeding" lyrics & music: Bob Dylan, recorded 1963, released 1991 in The Bootleg Series

6. Ewan MacColl - Go Down Ye Murderers

A song about Timothy Evans, a man accused of murdering his wife and child, which he denied until his last breath. They convicted him and hanged him in 1950. He was 25 years old. Three years later the real murderer, his neighbour John Christie, confessed, and the case played a major role in abolishing capital punishment in the UK.

The rope was fixed around his neck, and the washer behind his ear And the prison bell was tolling but Tim Evans did not hear Sayin' go down, you murderer, go down

They sent Tim Evans to the drop for a crime he didn't do It was Christy was the murderer, and the judge and jury too Sayin' go down, you murderers, go down

1956, from Bad Lads and Hard Cases: British Ballads Of Crime And Criminals lyrics & music: Ewan MacColl

7. Jennifer Lawrence - The Hanging Tree

One of the stranger things that can happen at the hanging tree is camaraderie. "On the gallows tree, all men are brothers", to quote A Feast for Crows, and when the state murders, then in defiance, an execution ballad can become a protest song. Many have in real life, this one is fiction, from The Hunger Games. Wisely, the director asked the composer for a simple tune, nothing elaborate, something that could be "sung by one person or by a thousand people".

Are you, are you coming to the tree? Wear a necklace of rope side by side with me Strange things have happened here, no stranger would it be If we met at midnight in the hanging tree

2014, from The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 OST lyrics: Suzanne Collins music: James Newton Howard

8. Let's Play Dead - Heaven and Hell

A fairly traditional execution ballad written recently for the series Harlots. Margaret Wells sings it to herself for consolation and courage, as she sits alone in a cell, waiting to get dragged to the gallows.

I'm no more a sinner than any man here I'm no less a saint than the priest at god's ear But now I am snared, they will punish me well With a ladder to heaven and a rope down to hell

2018, from the single Heaven and Hell, for Harlots Season 2 Episode 7 lyrics & music: Let's Play Dead

9. Odetta - Gallows Pole

Probably the most well-known execution ballad of the 20th century, thanks to several iconic renditions. This one remains my favourite.

Hangman, hangman, slack your rope, slack it for a while I think I see my father coming, riding many a mile Papa did you bring me silver, did you bring me gold? Or did you come to see me hanging by the gallows pole?

1960, from At Carnegie Hall lyrics & music: traditional (Child 95 / Roud 144), known under many other titles ("Hangman", "The Maid freed From the Gallows", "The Prickle-Holly Bush"); this version is directly influenced by Lead Belly's "Gallis Pole" (1930s), and they both informed Led Zeppelin's 1970 version

10. Johnny Cash - 25 Minutes to Go

Peak gallows humour, uproariously funny and defiant, and somehow still conveying the terror of a man who's about to die and emphatically doesn't want to. Performed live at Folsom Prison.

Then the sheriff said boy I'm gonna watch you die, 19 minutes to go So I laughed in his face and I spit in his eye, 18 minutes to go Now here comes the preacher for to save my soul, 13 minutes to go And he's talking about burning but I'm so cold, 12 minutes to go

1968, from At Folsom Prison lyrics & music: Shel Silverstein, from his 1962 album Inside Folk Songs

11. Johnny Cash - Sam Hall

A classic execution ballad with many versions (see here for its complicated history), some of which are stoic and dignified, and others humorous. But this one brims with rage. Sam Hall will not be repenting on the gallows, and he'll see you all in hell.

My name it is Sam Hall and I hate you one and all And I hate you one and all, damn your eyes

2002, from American IV: The Man Comes Around lyrics & music: : traditional, 18th century broadside ballad, Roud 369

12. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds - Up Jumped the Devil

A song about a man doomed from the start to play the villain’s part, and the origin of this blog’s #swinging from the gallows tree tag.

Who's that hanging from the gallow tree? His eyes are hollow but he looks like me Who's that swinging from the gallow tree? Up jumped the Devil and he took my soul from me

1999, from Tender Prey lyrics: Nick Cave music: Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds

13. NOT ON SPOTIFY: Dead Rat Orchestra - The Black Procession

This ballad imagines a sinister procession of 20 criminals (black tradesmen brought up in hell!), each with their own specialty (it's mostly thieves of some sort), on the way to the gallows. The last and worst of them is the thief-catcher, and if one of them is innocent, they'll all go free. But of course none of them are. It's written in thieves' cant (lyrics and more context here), and the chorus means: "Look well, listen well, see where they are dragged, up to the gallows where they are hanged."

Toure you well; hark you well, see where they are rubb’d, Up to the nubbing cheat where they are nubb’d.

2015, from Tyburnia: A Radical History Of 600 Years Of Public Execution lyrics: from The Triumph of Wit by J. Shirley, 1688 music: Robin Alderton, Daniel Merrill & Nathaniel Robin Mann

14. John Harle & Marc Almond - The Tyburn Tree

And where does the Black Procession lead? To Tyburn, of course. The dark gothic side of Marc Almond.

The Tyburn Tree, I weep for thee, blood in the roots 'Tis not a tree with bark and leaves of spring awakening 'Tis not a tree with blossom and fruit, 'tis not a tree No boughs to bend beneath the unruly breath of winter No memories of woods warmed by spring's sweet touch 'Tis not a tree — take a ride to Tyburn and dance the last jig

2014, from The Tyburn Tree (Dark London) lyrics: Marc Almond music: John Harle

15. CocoRosie - Gallows

Speaking of dark and gothic.

They took him to the gallows, he fought them all the way though And when they asked us how we knew his name We died just before him, our eyes are in the flowers Our hands are in the branches, our voices in the breezes And our screaming is in his screaming

2010, from Grey Oceans lyrics & music: Sierra Rose Casady & Bianca Leilani Casady

16. The Tiger Lillies - Hang Tomorrow

In their Two Penny Opera, the pioneers of dark cabaret reimagine Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, and take all the suaveness out of Mack the Knife. Here they also take all the fight out of him. What's even left? A pathetic empty husk, a bastard (let's not forget that Brecht's MacHeath is no rogue with a heart of gold, he's a horrible man) who can't even be intriguing. How disturbingly pedestrian.

So here I am in jail again, oh god it stinks of piss I've been in here since I was young, so I can reminisce It's looking rather grim this time, it's looking rather bad But if I swing tomorrow in some ways I'll be glad

2001, from Two Penny Opera lyrics & music: Martyn Jacques

17. Tom Hollander - Ballad In Which MacHeath Begs All Mens' Forgiveness

In The Threepenny Opera, Mack the Knife stands on the scaffold and asks for pity. No point being judgmental now, that he's about to die. He morbidly describes how his dead body will end up, and then he lashes out at everyone, cops and criminals (same difference), while still begging them all for forgiveness. Very VERY sarcastically. The ballad's concept is borrowed from François Villon (see below), and this translation is unusually bold (honorific, see here and here for other translations and context).

You crooked cops with your Mercedes, your mobile phones, your trendy jackets, your cuts from drugs and dice and ladies, your Scotland Yard protection rackets.

Let heaven smash your fucking faces, slash you and let the blood run free and break you in a thousand places. I've pardoned you. You pardon me.

1994, from The Threepenny Opera - Donmar Warehouse Original Cast lyrics: Bertolt Brecht 1928, loosely inspired by François Villon's "Ballad of the Hanged" c. 1489, translated by Jeremy Sams 1994 music: Kurt Weill 1928

18. Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock - Ballade des pendus

And here's the OG Ballad of the Hanged, written in the 15th century by the OG poète maudit, François Villon (translation here). It paints an indelible picture of strung up corpses swaying in the wind, decaying, pecked by birds, ravaged by the elements and time. And crucially, it's in the first person. The hanged speak, begging their fellow-humans for pity, and god for forgiveness.

Frères humains, qui après nous vivez, N'ayez les cœurs contre nous endurcis, Car, si pitié de nous pauvres avez, Dieu en aura plus tôt de vous mercis. Vous nous voyez ci attachés, cinq, six: Quant à la chair, que trop avons nourrie, Elle est piéça dévorée et pourrie, Et nous, les os, devenons cendre et poudre. De notre mal personne ne s'en rie; Mais priez Dieu que tous nous veuille absoudre!

recorded 1979, released 1999 in the Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock reissue lyrics: François Villon, c. 1489 music: Saga de Ragnar Lodbrock

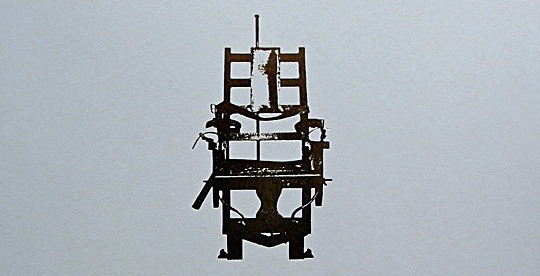

19. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds - The Mercy Seat

Honorary inclusion, a song not about hanging: the mercy seat is the electric chair. But the lyrics are a punch and this is a torrent of a song, a whirlwind, a masterpiece, a 7-minute cynic snarl. So it couldn't possibly get left out of this compilation.

And the mercy seat is awaiting, and I think my head is burning And in a way I'm yearning to be done with all this measuring of proof An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth (a life for a life and a truth for a truth) And anyway I told the truth, and I'm not afraid to die (and I'm afraid I told a lie)

1999, from Tender Prey lyrics & music: Nick Cave

20. Graveyard Train - Ballad For Beelzebub

And after? Welcome to Hell, ladies and gents, and bards. (Bards are rogues, too.) The Graveyard Train play a kind of Southern Gothic (but very southern, they're Australian), and here they entertain the thought of a band that ends up in hell and has to keep playing, without end, for an audience that can't hear. What a bleak prospect.

Well the air on the stage is burning our lungs And we're all going deaf from the beating drums And you can't see a thing for all the blood and the sweat in our eyes

Well we played till we died, and now we're all dead But the Man says we got to get up there again And you can't come down till the brimstone turns to ice

2008, from The Serpent And The Crow lyrics & music: Graveyard Train

21. Samuel Kim feat. Colm R. McGuinness - Hoist the Colours

Yo ho, all together Hoist the colours high Heave ho, thieves and beggars

But we won't end in hell. The only acceptable ending to this compilation is the triumphant version (wait for it) of its beginning: a pirate's end. Traditionally the gibbet, yes, but also the ghost ship that still sails, the ripple that still travels, and the story that still gets told.

Did I stutter the first time?

NEVER SHALL WE DIE

#long post#swinging from the gallows tree#mixtape#trs#prison ballads#pirate#bard#The Threepenny Opera

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

HOMILY for Christ the King (EF)

Col 1:12-20; John 18:33-37

Today is the fiftieth anniversary of the canonisation in 1970 of the forty martyrs of England and Wales by Pope St Paul VI, in St Peter’s Basilica. Today, we recall the heroic sacrifice and brave witness to the truth of forty of our countrymen, from the Prior of the London Charterhouse, St John Houghton, executed at Tyburn in 1535, to the Welsh Jesuit St David Lewis, executed in 1679. Over the course almost 150 years, hundreds of faithful Catholics from every walk of life in English society were executed by the State, martyred for their refusal to allow the State to interfere with the fundamental rights of the Church.

For as Pope Pius XI said in 1925 when he instituted today’s annual feast of Christ the King: “[The Church] has a natural and inalienable right to perfect freedom and immunity from the power of the state; and that in fulfilling the task committed to her by God of teaching, ruling, and guiding to eternal bliss those who belong to the kingdom of Christ, she cannot be subject to any external power.” (Quas primas, 31) The Church and her bishops may, of course, prudently choose to co-operate with the State, but only if this does not hinder the mission and raison d’être of the Church, which is to lead souls to Christ through the preaching of the Gospel in its fullness, and through the faithful administration of the Sacraments of salvation.

For, beautiful and valuable and precious though our life and our friendships in this present lifetime are, today’s feast, and the deaths of the martyrs remind us of an often forgotten truth in our secularised world. We live, ultimately, not for this life and its joys and pleasures, but rather, all of this present life, whether it be long or short, is a preparation for the life of the world to come; this life on earth is that short time given to us in God’s providence during which we learn to forsake sin and, by the grace of Christ, we hope to increase in charity, so that we can become true citizens of God’s heavenly Kingdom. So, on the wall of his cell in the Tower of London St Philip Howard scratched these words: “Quanto plus afflictionis pro Christo in hoc saeculo, tanto plus gloriae in futuro”; ‘The more suffering for Christ in this life, the more glory in heaven’. Fittingly then, in 2020, on this feast day of Christ the King, do we recall the witness of these faithful servants of Jesus Christ who would deny their worldly earthly kings rather to forsake Christ the true and universal King. Hence St Thomas More famously said that he died “the king’s good servant, but God’s first.”

The Church, therefore, must always point beyond this world, and call humanity to serve God’s kingdom, to repent of sin and prideful error, and so to be saved by Christ the King. Thus, commenting on today’s Gospel, Pope Pius XI said: “Before the Roman magistrate [Christ] declared that his kingdom was not of this world. The gospels present this kingdom as one which men prepare to enter by penance, and cannot actually enter except by faith and by baptism, which, though an external rite, signifies and produces an interior regeneration. This kingdom is opposed to none other than to that of Satan and to the power of darkness. It demands of its subjects a spirit of detachment from riches and earthly things, and a spirit of gentleness. They must hunger and thirst after justice, and more than this, they must deny themselves and carry the cross.” (Quas primas, 15)

The forty martyrs who we especially remember today exemplify the ultimate self-denial and carrying of the Cross that is demanded of us Christians. This group of English and Welsh Martyrs, just a small representation of the hundreds executed during the so-called Reformation, is composed of 13 diocesan priests (or secular clergy), 3 Benedictines, 3 Carthusians, 1 Brigittine, 2 Franciscans, 1 Augustinian, 10 Jesuits and 7 members of the laity, including 3 mothers. And all of them sacrificed everything for the sake of the Holy Mass and the Sacraments; for the unity of Christ’s Church in communion with the Pope; for the sake of the sacred Priesthood through whom we receive the Sacraments; and for the sake of Christ’s teaching on the sanctity of marriage and family life. Therefore, in our times and in our country, we honour these holy men and women, and we show ourselves to be their friends, if we love what they love. So, let us love the Mass and the one holy Catholic and apostolic Church; love the Holy Father and pray for him; love your clergy, pray for them and uphold them with care and help; love your husband, your wife, and as a family bear witness to the love and joy of the Gospel. For as Pope Francis says: “The triune God is a communion of love, and the family is its living reflection.” (Amoris lætitia, 11) The Christian family, therefore, bears witness as a vestige of the Holy Trinity; the presence of the loving God at work among us, extending the reign of Christ one household at a time. Therefore, enthrone Christ in your homes, in your families, and in your own hearts.

What does this entail? Pope Pius XI said, Jesus Christ “must reign in our minds, which should assent with perfect submission and firm belief to revealed truths and to the doctrines of Christ. He must reign in our wills, which should obey the laws and precepts of God. He must reign in our hearts, which should spurn natural desires and love God above all things, and cleave to him alone. He must reign in our bodies and in our members, which should serve as instruments for the interior sanctification of our souls”. The forty martyrs, again, demonstrate the consequence of being given over to the reign of Christ: we would be willing to die for the truths of the Gospel; willing to give up sin and to behave and act in ways that please God; willing to work and suffer in order to uphold the Kingdom of God in our world, while labouring to defeat the lies and falsehoods of the Enemy. However, it is most noteworthy in the accounts of their lives and their final words that the forty martyrs of England and Wales did all this without rancour or bitterness or anger or hatred. Instead, they spoke with humour, serenity, and humility, always acting with charity. For this is the genuine sign that Christ is their King. Let it be so for each of us too, especially in these difficult and polarised times. Hence Pope Pius XI said: “in a spirit of holy joy [let us] give ample testimony of [our] obedience and subjection to Christ.” For, as Pope Francis says, “we all have to let the joy of faith slowly revive as a quiet yet firm trust, even amid the greatest distress.” (Evangelii gaudium, 6) It is a joy that flows from a childlike confidence and trust in God’s love, in the victory of the Risen Lord Jesus; a joy that springs from a firm faith in divine Providence.

This is the joy of the martyr, of the subjects of Christ the King, for they know that, at the end, all of creation, all human history, all time and creatures shall fall “under the dominion of Christ. [And] in him is the salvation of the individual, in him is the salvation of society.” (Quas primas, 18) Hence Pope Pius XI, reflecting on the set-backs and seeming defeats that the Church has endured, and on the crises caused by persecutions and martyrdoms, gave witness to his trust in God’s Providence and his Kingship. He said: “the admirable wisdom of the Providence of God, who, ever bringing good out of evil, has from time to time suffered the faith and piety of men to grow weak, and allowed Catholic truth to be attacked by false doctrines, but always with the result that truth has afterwards shone out with greater splendour, and that men's faith, aroused from its lethargy, has shown itself more vigorous than before.” (Quas primas, 22)