#TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

THERE IS NO MORE TIME TRAVEL POSSIBLE BECAUSE OF MASSIVE HIGHER DIMENSIONAL TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS ERECTED TO PREVENT IT

#THERE IS NO MORE TIME TRAVEL POSSIBLE BECAUSE OF MASSIVE HIGHER DIMENSIONAL TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS ERECTED TO PREVENT IT#TIME TRAVEL#TECHNOLOGY#TEMPORAL CHANGE#TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS#TEMPORAL CHANGE INTERDICTION FIELDS#criminals#time#time travel#time traveling criminals#traveling#brad geiger#paul atreides

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

TEMPORAL CHANGE PREVENTION FIELDS

#TEMPORAL CHANGE PREVENTION FIELDS#machine learning#TEMPORAL#TEMPORAL CHANGE#TEMPORAL CHANGE PREVENTION#TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION#TEMPORAL CHANGE INTERDICTION#TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS#TEMPORAL CHANGE INTERDICTION FIELDS#FIELD#FIELD STRENGTH

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS

Operate relatively in relation to the entangled nature of all physical matter, which stems from all physical matter being composed of instances of the first Place Particle, which also involves generating a temporal change inhibition field. Selective side-timing. Time travel duplication without duplicating the entire universe. Replicators. Pull souls constantly for safety and security purposes.

#replicators#temporal change#temporal change inhibition field#temporal change inhibition fields#field#fields#pull#generate wormhole with soul as other end#generate wormhole with energy signature as other end#generate wormhole with spirit as other end#souls or spirits or energy signatures are not physically connected to their apparent physical location so no reaction is produced

0 notes

Text

DESCENDANTS OF OR RELATIVES OF TIME TRAVELING CRIMINALS BORN AFTER THE ERECTION OF TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS COMPLETELY PREVENTED ALL ADDITIONAL CRIMINAL TIME TRAVEL

0 notes

Text

Interesting Papers for Week 5, 2024

Input density tunes Kenyon cell sensory responses in the Drosophila mushroom body. Ahmed, M., Rajagopalan, A. E., Pan, Y., Li, Y., Williams, D. L., Pedersen, E. A., … Clowney, E. J. (2023). Current Biology, 33(13), 2742-2760.e12.

Different types of uncertainty in multisensory perceptual decision making. Aston, S., Nardini, M., & Beierholm, U. (2023). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1886).

Multisensory causal inference is feature-specific, not object-based. Badde, S., Landy, M. S., & Adams, W. J. (2023). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1886).

Obstacle avoidance in aerial pursuit. Brighton, C. H., Kempton, J. A., France, L. A., KleinHeerenbrink, M., Miñano, S., & Taylor, G. K. (2023). Current Biology, 33(15), 3192-3202.e3.

Looking away to see: The acquisition of a search habit away from the saccade direction. Chen, C., & Lee, V. G. (2023). Vision Research, 211, 108276.

Experience dependent plasticity of higher visual cortical areas in the mouse. Craddock, R., Vasalauskaite, A., Ranson, A., & Sengpiel, F. (2023). Cerebral Cortex, 33(15), 9303–9312.

The effects of probabilistic context inference on motor adaptation. Cuevas Rivera, D., & Kiebel, S. (2023). PLOS ONE, 18(7), e0286749.

Absence of visual cues motivates desert ants to build their own landmarks. Freire, M., Bollig, A., & Knaden, M. (2023). Current Biology, 33(13), 2802-2805.e2.

Temporal and spatial reference frames in visual working memory are defined by ordinal and relational properties. Heuer, A., & Rolfs, M. (2023). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 49(9), 1361–1375.

An adaptive behavioral control motif mediated by cortical axo-axonic inhibition. Jung, K., Chang, M., Steinecke, A., Burke, B., Choi, Y., Oisi, Y., … Kwon, H.-B. (2023). Nature Neuroscience, 26(8), 1379–1393.

Remapping in a recurrent neural network model of navigation and context inference. Low, I. I., Giocomo, L. M., & Williams, A. H. (2023). eLife, 12, e86943.3.

The role of conflict processing in multisensory perception: behavioural and electroencephalography evidence. Marly, A., Yazdjian, A., & Soto-Faraco, S. (2023). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 378(1886).

Using temperature to analyze the neural basis of a time-based decision. Monteiro, T., Rodrigues, F. S., Pexirra, M., Cruz, B. F., Gonçalves, A. I., Rueda-Orozco, P. E., & Paton, J. J. (2023). Nature Neuroscience, 26(8), 1407–1416.

Functional organization of visual responses in the octopus optic lobe. Pungor, J. R., Allen, V. A., Songco-Casey, J. O., & Niell, C. M. (2023). Current Biology, 33(13), 2784-2793.e3.

What do our sampling assumptions affect: How we encode data or how we reason from it? Ransom, K. J., Perfors, A., Hayes, B. K., & Connor Desai, S. (2023). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 49(9), 1419–1438.

Robust estimation of cortical similarity networks from brain MRI. Sebenius, I., Seidlitz, J., Warrier, V., Bethlehem, R. A. I., Alexander-Bloch, A., Mallard, T. T., … Morgan, S. E. (2023). Nature Neuroscience, 26(8), 1461–1471.

How coupled slow oscillations, spindles and ripples coordinate neuronal processing and communication during human sleep. Staresina, B. P., Niediek, J., Borger, V., Surges, R., & Mormann, F. (2023). Nature Neuroscience, 26(8), 1429–1437.

Organizing memories for generalization in complementary learning systems. Sun, W., Advani, M., Spruston, N., Saxe, A., & Fitzgerald, J. E. (2023). Nature Neuroscience, 26(8), 1438–1448.

Homogeneous inhibition is optimal for the phase precession of place cells in the CA1 field. Vandyshev, G., & Mysin, I. (2023). Journal of Computational Neuroscience, 51(3), 389–403.

Excitatory nucleo-olivary pathway shapes cerebellar outputs for motor control. Wang, X., Liu, Z., Angelov, M., Feng, Z., Li, X., Li, A., … Gao, Z. (2023). Nature Neuroscience, 26(8), 1394–1406.

#neuroscience#science#research#brain science#scientific publications#cognitive science#neurobiology#cognition#psychophysics#computational neuroscience#neurons#neural computation#neural networks

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biological Bases of Behaviour

Neuroanatomy

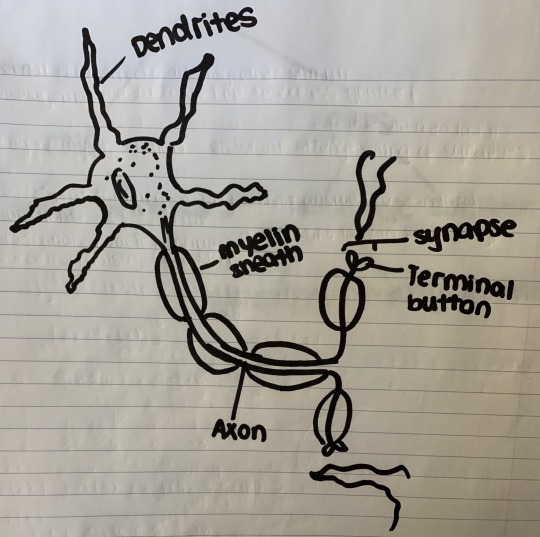

Neuroanatomy is the study of the parts and functions of neurons. Neurons are individual nerve cells. Each neuron is made of distinct parts.

Dendrites - Rootlike parts of the cell that stretch out from the cell body. Dendrites grow to make synaptic connections with other neurons. This is where a signal from another neuron is received.

Soma- The cell body, contains the nucleus and the cell's organelles

Myelin Sheath- A fatty covering of the axon that allows neural impulses to speed up

Terminal Buttons- The branched end of the axon that contains neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters- Chemicals contained in terminal buttons that enable neurons to communicate.

Synapse- The space between the terminal button of one neuron and the dendrites of another.

How a Neuron Fires

A resting neuron is slightly negative because mostly negative ions are within the cell and mostly positive ions are on the outside of it. The cell membrane is selectively permeable. When the terminal buttons are stimulated, neurotransmitters are released into the synapse. They fit into receptor sites on the dendrites of the other neuron. Once the threshold is reached (enough neurotransmitters are received) the cell membrane of the other neuron becomes permeable, and positive ions flood the cell, making the overall charge of the cell positive. This change in charge travels down the neuron- this is an action potential. Once the action potential reaches the button, neurotransmitters in the neuron are released into the synapse. The process then may begin again in another neuron. Either a neuron fires completely or doesn’t fire at all- this is the all-or-none principle. A neuron cannot fire a little or a lot. It’s the same every time.

Neurotransmitters

Some neurotransmitters are excitatory, meaning that they excite the next cell into firing. Others are inhibitory meaning that they inhibit the next cell from firing.

Afferent Neurons- Take information from the senses to the brain

Interneurons- Take messages from afferent neurons and send them elsewhere in the brain or on to efferent neurons

Efferent Neurons- Take information from the brain to the rest of the body

The Organisation of the Nervous System

The Central Nervous System- The brain and the spinal cord

The Peripheral Nervous System- The other nerves in the body- it’s divided into two categories, the somatic nervous system (voluntary muscle movements) and the autonomic nervous system, which itself is broken up into two parts:

Sympathetic Nervous System- Mobilises the body in response to stress (fight or flight)

Parasympathetic Nervous System- Slows the body down in after a stress response (rest and digest)

Normal Peripheral Signal Transmission:

Sensory neurons are activated, transmitting a message up a neuron to the spine (afferent nerves) the message moves up through your spinal cord until it enters the brain through the brain stem to the sensory cortex. In response, the motor cortex sends impulses down the spinal cord to the muscles where the sensory neurons were activated, allowing a response to take place.

Reflexes:

Reflexes are responses that take place outside of conscious control. Sensory information is taken to the spinal cord, and processed by the spinal cord, returning to the motor neurons.

How We Study the Brain

Accidents: Accidents which damage the brain can serve to show what the damaged part of the brain does, as that section of the brain will no longer function properly. Phineas Gage's famous railroad accident caused him to act without inhibition, showing the frontal lobe played a part in enforcing social norms. He was also highly emotional.

Lesions: The removal or destruction of part of the brain. Nowadays, this is never done purely for experiments. It’s often done to remedy certain illnesses. Back in the day, mental illness was often remedied by frontal lobotomies, as it would cause the patient to calm.

Electroencephalogram (EEG): Detects brain waves- allows scientists to study how active the brain is, especially in sleep research.

Computerised Axial Tomography (CAT) Scan: A sophisticated X-ray- cameras rotate the brain and combine the images into pictures which show a detailed 3D image of the brain’s structure.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Similar to a CAT scan, however, uses magnetic fields to determine the density and location of brain material to create a more detailed image of the brain.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan: Measures how much of a specific chemical (often glucose) the brain is using, showing which part of the brain is most active during certain tasks.

Functional MRI (fMRI): Combines the elements of an MRI scan and a PET scan. Shows the details of brain structure and information about blood flow in the brain.

How We Classify The Brain

There are 3 major sections of the brain; the hindbrain, the midbrain, and the forebrain.

Hindbrain: The life support system of the brain

The Medulla Oblongata: Involved in the control of blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing. Located above the spinal cord

The Pons: Above the medulla, connects the hindbrain with the mid and forebrain. Also involved in controlling facial muscles.

The Cerebellum: Located on the bottom rear of the brain, responsible for coordinating some habitual muscle movements

Midbrain: Just above the spinal cord. Very small in humans, but responsible for coordinating simple movement with sensory information. It integrates some types of sensory information and muscle movement. One important structure is the reticular formation which is a netlike collection of cells throughout the midbrain that controls general body arousal and focus. Without it, we would be in a coma.

Forebrain: The forebrain helps control what we consider consciousness. It is very large in humans, and what makes us, us.

Thalamus: Located on top of the brain stem. It receives sensory signals and relays them to the appropriate part of the brain.

Hypothalamus: Controls several metabolic functions such as body temperature, sexual arousal, hunger, thirst, and the endocrine system.

Amygdala and Hippocampus: The arms surrounding the thalamus. The amygdala is vital to experiencing emotion, and the hippocampus is vital to the memory system. Memories are processed through this area and sent to other parts of the cerebral cortex for permanent storage

Cerebral Cortex

The grey wrinkled surface of the brain, densely packed with neurons. When we are born, the cerebral cortex is full of disconnected neurons. As we grow and learn, dendrites grow and connect with each other, forming a complex neural web. The surface of the cerebral cortex is wrinkled. Those wrinkles are called fissures and they increase the available surface area of the brain. The Cerebral Cortex is made of 8 different lobes- four on each hemisphere. Any part of the Cerebral Cortex not associated with receiving sensory information or dealing with motor function is called an association area

FRONTAL LOBES: Large areas of the cerebral cortex at the front of the brain behind the eyes. The anterior part of the frontal lobe is called the prefrontal cortex and is responsible for directing thought processes. It is the brains central executive and is essential for predicting consequences, pursuing goals, controlling emotions, and abstract thought. Most people’s left hemisphere frontal lobe contains one of the 2 language processing areas- Broca’s area (responsible for the muscles necessary for speech production)- some left-handed patients have it in the right hemisphere. There is a thin strip at the back of the frontal lobe called the motor cortex which sends signals to the muscles, controlling voluntary movement

PARIETAL LOBES: Behind the frontal lobe on top of the brain. Contains the Sensory/Somatosensory Cortex right behind the motor cortex. It receives oncoming sensations from the rest of the body. Like the motor cortex, the top of the sensory cortex receives signals from the bottom of the body, and so on.

OCCIPITAL LOBES: Located at the very back of the brain, farthest away from the eyes- and yet it interprets messages from the eyes in our visual cortex Impulses from the right half of each retina is sent to the right occipital lobe, and impulses from the left half of each retina is sent to the left occipital lobe

TEMPORAL LOBES: Process sounds sensed by our ears. Sound waves are processed by the ears, become neural impulses and are interpreted in the auditory cortices. The auditory cortex is not lateralised like the visual cortex. Sound received from the left ear is processed in the auditory cortices in both hemispheres. Wernicke’s Area, the second language area is also located here. It’s responsible for comprehending language.

Hemispheres

The cerebral cortex is divided into two hemispheres, connected by a nerve bundle known as the corpus callosum. The hemispheres are like mirror images of each other, however, are slightly different. The left hemisphere receives sensory information and controls the motor function of the right half of the body. The right hemisphere receives sensory messages and controls the motor function of the left half of the body. This is a concept known as contralateral control. The left hemisphere may be active during the logic and sequential tasks and the right during spatial and creative tasks, but not enough information is known to fully make that conclusion. The specialisation of function in each hemisphere is known as Brain Lateralisation/Hemispheric Specialisation. A lot of research into this comes from split-brain patients, whose corpus callosum has been severed. This is a treatment used to deal with severe epilepsy and was pioneered by Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga.

Brain Plasticity

The brain is somewhat flexible. If necessary, other parts of the brain can adapt to perform other functions- dendrites can grow to replace damaged sections of the brain, especially in younger children whose dendrites are growing at their fastest.

Endocrine System

The nervous system sends rapid signals that go away quickly. The endocrine system sends hormonal signals which travel throughout the body and last for a long time. The hypothalamus controls this system.

Adrenal Glands: Produce adrenaline, signals the rest of the body to prepare for fight or flight

Ovaries and Testes: Produce sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone) which allow for sexual development.

Genetics

Genetics is another important part of psychological research that is just now becoming realised. Most human traits like body shape, introversion or extroversion are the results of nature (genetics) and nurture (environment). Part of psychology is attempting to understand how much each of these concepts contributes to the development of traits.

Twins

Twins are an essential part of nature vs nurture experiments, as monozygotic twins (identical twins) contain the exact same DNA, studying them in separate environments can reveal the connection between nature and nurture. Studies like these have found that IQ is strongly connected to nature, however, there are biases in these studies. Since the twins share physical similarities, others may treat them in similar ways, creating the same effective psychological environment.

Chromosomal Abnormalities

Sometimes, errors occur during cell development, or as a fetus develops. There is more information on this in my post on molecular genetics. Here are some examples of disorders that occur as a result.

Turner’s Syndrome: Babies born with only one X chromosome, causing shortness, webbed necks, and differences in physical development.

Klinefelter’s Syndrome: Babies born with two X chromosomes and a Y chromosome, causing minimal sexual development and extremely introverted traits.

Down’s Syndrome: One of many disorders which inhibit mental development. It’s caused by an extra 21st chromosome and can cause a rounded face, shorter fingers and toes, slanted far set eyes, and poor mental development.

#AP Psychology#Psychology#Biopsychology#Biology#Neuroscience#anatomy#brain anatomy#human brain#human anatomy#college board#AP#AP Exam#Nervous System#Endocrine system#neurons#bio#human bio#physiology#physio#human physiology#science#education#studyblr#study blog#physiology studyblr#anatomy studyblr#psychology studyblr#biology studyblr

619 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iris Publishers - Current Trends in Clinical & Medical Sciences (CTCMS)

Executive Functions: Definition; Contexts and Neuropsychological Profiles

Authored by Dott Giulio Perrotta

Definition and clinical context of executive functions

The term “executive functions” (E.F.) refers to a complex cognitive construct in the form of a system organized in functional modules of the mind; where a series of processes necessary to maintain an appropriate; organized and flexible planning mode are included. resolution (or problem solving); control and coordination; aimed at a purpose [1-3].

To simplify; the executive functions are those abilities that answer the question << Who is in charge? >> and concern mental processes aimed at the elaboration of adaptive cognitive-behavioral schemes; at the base of planning; decision making; working memory; corrective response to error feedback; predominant habits; mental flexibility.

This complex construct thus implies:

a. An ability to inhibit a response or to postpone it at a later and more appropriate time.

b. A strategic and flexible planning of behavioral sequences.

c. A mental representation of the task that includes both the relevant information encoded in the memory and the future objectives to be achieved.

There are several possible definitions; from a theoretical and organizational point of view [4]:

1) The executive functions represent a system of abilities that allows to create objectives; to preserve them in memory; to control the actions; to foresee the obstacles and to reach objectives (Stuss 1992).

2) Executive functions represent the set of abilities that allow the person to successfully implement independent; intentional and useful behaviors (Lezak 1993).

3) Executive functions are higher-order cognitive functions that make it possible to formulate objectives and plans; remember these plans over time; choose and start actions that allow us to reach those goals; monitor the behavior and adjust it so as to arrive at those goals (Aron 2008).

It therefore appears evident that the executive functions are not easy to define; since this term does not refer to a single capacity but rather to a set of different sub-processes necessary to perform a specific task. They are superior cortical functions responsible for the control and planning of behavior; they are processes that allow the person to plan and implement projects aimed at achieving a goal and are necessary because they guarantee the monitoring and modification of their behavior in case of need or they adapt it to new contextual situations.

They consist of six steps:

1) Analyzing the task.

2) Plan how to achieve the task.

3) Organize the steps needed to carry out the task in question.

4) Develop a timeline to complete the task.

5) Adjust or change steps; if necessary; to complete the task.

6) Complete the task in a timely manner.

They are therefore executive functions surely:

a) The inhibition; or the ability to focus attention on the relevant data ignoring the distractors and inhibiting inadequate or impulsive motor and emotional responses with respect to stimuli.

b) Flexibility; or the ability to move from one set of stimuli to another based on information from the context.

c) Planning; or the ability to formulate a general plan and organize actions in a hierarchical sequence of goals.

d) The working memory; or the ability to activate and maintain the plan and the work area at a mental level; to have a mental reference set on which to work mentally.

e) Attention; or the ability to maintain concentration on a given element.

f) Fluency; or the ability of divergent thinking and ability to generate new and different solutions with respect to a problem [5].

Although those most investigated for information on cognitive functioning are the basic functions of working memory [6] (or updating; the ability to maintain; update and process information in mind in time for the resolution of a task); of cognitive flexibility (or shifting; the ability to pass from one mental operation to another by controlling the mutual interference between the two actions) and inhibition (or inhibition; the ability to control automatic responses that interfere in achieving of a purpose); the executive domain does not end with the only cognitive processes listed above; but also involves mechanisms that play a part in the regulation of emotions; behavior and motivation.

A dichotomous distinction has been formulated in recent years between “Hot” executive functions and “Cool” executive functions [Zelazo 2004]:

a) The “Cool” executive functions represent those functions based on a complex; cognitive; controlled and slower processing; which are activated when the subject is dealing with abstract and decontextualized problems. The neurophysiological area used for these functions is the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex [7].

b) The “Hot” executive functions are linked to an automatic and emotional processing of the stimuli; or a simple and rapid programming that intervenes in situations of stress; these functions are required in significant situations and involved in the regulation of emotion and motivation. The neurophysiological area used for these functions is the ventromedial prefrontal cortex [8].

The “Hot” executive functions and the “Cool” executive functions; according to this theoretical construct; work synchronously in order to guarantee an ideal functioning; but neuropsychological studies suggest a double dissociation between the two types of functions; documenting injuries on load Hot in the absence of problems against the Cool and the Cool in the absence of Hot.

The advances in the methodological field and in particular the conception of experimental tests with motor; linguistic and memory requirements; compatible with the level of competence of the child in early childhood; have allowed us to observe how the development of executive functions begins earlier; compared to what was previously assumed; this applies to both the Cool and the Hot ones. As far as the Cool is concerned; we have already seen how at 12 weeks the child is able to preserve the memory of the objective structure of an event in which he was the protagonist to reuse it in similar situations; from seven to eight months the first signs of working memory and inhibitory control begin to appear; regarding the Hot; some observations seem to suggest difficulties in the control of this executive domain in the first two years of life; although the processes of cortical development seem to affect these regions before those involved in the Cool: the child would indeed have difficulty in regulating the emotions and in postponing rewards/gratifications and presenting a way of relating to the self-centered world. Between the ages of three and five; the child succeeds in tasks that require maintaining information in the mind and at the same time the capacity for inhibition; between three and four years the ability to generate concepts develops; between four and five years the attentional control matures and there is an improvement in cognitive flexibility and in the ability to formulate strategies; at five years there is an increase in working memory and therefore in the ability to temporarily preserve and manipulate information online.

With preadolescence some executive skills reach maturity. Between seven and eight years and between nine and twelve years there is an increase in sensitivity to feedback in problem-solving; in the formulation of concepts and in the control of impulsiveness. At the age of seven; considerable progress has been reported in the speed of execution; in the ability to use the strategies; in the ability to maintain information in the mind and to work with it. Between the ages of eight and ten adult levels are reached in cognitive flexibility and at ten years the ability to maintain the set; the verification of hypotheses and impulse control is manifested; there is an improvement in the inhibitory control; in the vigilance and in the attention sustained between the eight and eleven years; period in which besides is assisted to an improvement in the performances tests that conjugate inhibitory competences and working memory; this last one suffers further efficiency improvements between nine and twelve years.

An improvement in the ability to understand emotions; intentions; beliefs and desires is noted in this period. Between thirteen and fifteen years there is an increase in memory strategies; in its efficiency; in time planning; in problem-solving and in the search for hypotheses. Furthermore; verbal fluency and the ability to plan complex motor sequences mature at the age of twelve. The changes of this period; both on the cognitive and the executive side; allow the person to cope with the new and growing demands that the physical and social environment put on him; experiencing a sense of independence; responsibility; and social awareness.

At fifteen years there is an improvement as regards attentional control and processing speed as well as maturation in inhibitory control. Between the ages of sixteen and nineteen; progress is made in working memory; problem-solving and strategic planning. From an executive point of view; Hot improves the ability to make decisions in the presence of rewards and losses. Between the ages of twenty and thirty; working memory; planning; problem-solving and the ability to implement targeted behaviors reach higher levels of functioning.

As regards the Hot Executive functions; the achievement of mature decision-making levels is achieved. With aging there is a gradual deterioration in some cognitive areas including the Executive Functions; although some changes are not evident before eighty years even though the brain degenerative process begins in the third decade of life. Between the ages of thirty and forty-nine; there is a decrease in information storage and temporal sequencing skills; the ability to formulate concepts; organization; planning and attentional shifting worsen between the fifty-three and sixty-four years. Starting from the age of sixty-five; memory difficulties are reported [9-11].

It is good to underline however that even today we think of the executive system and the attention system as separate entities: attention would act on sensory information and on internal representations while the executive system on behavior. If the attentional aspects allow the executive functions to mature; the executive system is seen as a form of attention directed towards oneself. Therefore, the development of E.F. involves a consolidation of intellectual cognitive abilities; learning and memories.

The Neural Correlates in Eating Disorders [12]

If neuroscience has been trying for decades to associate specific brain functions with specific brain areas; with the relative recent advent of functional neuroimaging and brain mapping; this commitment seems to have become dominant; however; the debate on the selective localization of complex faculties remains open; despite their historical location; identified in the so-called frontal lobe syndrome; even preceded the formulation of the construct (Galati; Tosoni; 2010); in fact; traditionally; they were classified as executive disorders those following damage in the prefrontal cortex.

Recent studies of neuroimage (Galati; Tosoni; 2010); carried out on healthy people through classical neuropsychological tests for the examination of E.F. reveal; however; also the activation of the posterior parietal cortex and of various subcortical centers; in addition to the areas of prefrontal cortex; whose functional subdivisions; however; still remain difficult to identify; due to its anatomy and its heterogeneous functionalities. In particular; the studies show that the frontal lobes are functionally connected with: the posterior parietal cortex; which appears to be involved in the reconfiguration of the responses and in the behavioral modifications (Sohn et al; 2000; Barber and Carter; 2005); the basal ganglia; the anterior cingulate; which seems particularly involved in situations of control of cognitive conflicts between environmental stimuli or behaviors and in the selection of agent responses in case of uncertainty (Carter and Van Veen; 2007; Rushworth and Beherens; 2008).

The scholars of the Executive Functions; therefore; remain cautious about their specific localization; preferring to believe that they are implemented in multiple distributed circuits; each of which includes connections with some portion of the prefrontal cortex (Galati; Tosoni; 2010; p. 36.). The same Luria (1962) who; on the basis of numerous clinical observations; first theorized the existence of a central control system for some higher order functions; such as planning; monitoring; self-regulation; involved more involvement interconnected cortical and subcortical areas: prefrontal cortex; cerebellum; some subcortical nuclei.

Therefore; the study on the functions performed by the prefrontal cortex remains open. It is believed that the executive functions are anatomically related to different areas of the prefrontal cortex; and to the associated cortico-subcortical circuits:

a) The dorso-lateral prefrontal area would be particularly involved in the abstraction and planning of actions.

b) The orbital-frontal area would be involved in the regulation of emotions and decision-making processes.

c) The anterior cingulate area (especially in the dorsal part) would be involved in the control of motivation and interfering stimuli.

The empirical evidences derived from the neuropsychological approach and from the neuroimaging show however that the executive functions connected to the orbito-frontal cortex mature early with respect to the executive functions connected to the dorso-lateral pre-frontal cortex [13]. An interesting review of 2006 takes in detail; albeit dated; the cognitive; affective and behavioral correlates of brain maturation that occurs during adolescence. This maturation; due to phenomena of myelination and synaptic pruning; is particularly accentuated in the prefrontal cortex; the main site of decision-making processes. If the executive functions and the decision-making processes are based on the functioning of prefrontal areas; which change considerably during adolescence; it can be hypothesized that the decision-making abilities of adolescents are still immature, and this may explain their risky behavior. This hypothesis is discussed; also, in relation to the onset of psychopathological disorders in this age group [14].

The Clinical and Strategic Approach in the Management of Executive Function Deficits [15]

Following an injury or dysfunction in the frontal lobes; due for example to a head injury; a degenerative pathology or a neoplasm; the patient can show the symptoms of what is called “frontal syndrome”. Frontal syndrome is a clinical picture characterized by cognitive deficits and / or behavioral; emotional and motor disorders.

Studies on adult patients with lesions in different areas of the prefrontal cortex show; in fact; partially different neuropsychological pictures:

1) Lesions in the anterior orbital part; in general; cause personality modifications and disinhibition.

2) The lesions in the orbito-frontal part; also because it is closer to the amygdala; to the hippocampus and to the hypothalamus; areas that mediate between internal states and environmental stimuli; generally present inattentive; impulsive behaviors; difficulty in problem solving and in taking of decisions; serious antisocial conduct.

3) Lesions in the medial part; including the anterior cingulate gyrus; cause poor motor control and difficulty in maintaining focused attention.

4) The laterals of the prefrontal cortex present action planning disorders; especially related to the management of mental representations useful for achieving a purpose and the difficulties related to written and spoken language are understood.

The lesions of the frontal cortex; caused by expansive processes of tumor; vascular or hypoxic origin; or cranial traumas or degenerative processes of the nervous system; therefore, lead to deficits in executive functions; in particular problems:

a) In planning and problem solving: the person has difficulty planning and executing a sequence of actions to reach a goal; but also in the planning of sequences of movements.

b) In cognitive flexibility: it has a rigid; non-flexible behavior and puts into effect perseverances; always giving the same answer or using the same strategy even when it proves inadequate.

c) In the working memory: the memory disorders that can be classified in the frontal amnesic syndrome are characterized by the inability to retain new information; greater distractibility and confabulations; difficulty in using memorization strategies; inability to know how to use the new acquired data; incapacity to memorize voluntarily.

d) In the inhibition of automatic behaviors not congruent with the situation: it is the case of the “environmental syndrome” or “dependence of use”: placed for example in front of objects that it is used to use; the person uses them without any invitation and without any reason (for example; a patient who in front of a bottle of water placed on the examiner’s desk; takes it and drinks it).

e) In decision-making: the difficulty of deciding in an advantageous way for oneself and of respecting social norms is understood (Bechara et al. 2000; Rolls; 2000). Patients with this disorder are more likely to make risky choices and develop; for example; a gambling addiction.

f) In the regulation of emotions and behavior: we can have a patient who shows a picture of disinhibited type symptoms characterized by euphoria; restlessness; sexual disinhibition; inappropriate social behavior; poor interest in others; uninhibited behavior; with little impulse control; easy irritability and aggressiveness; euphoria; emotional lability; or an apathetic type symptomatology with a “pseudo-depressed” personality; therefore with modifications characterized by indifference; apathy; decreased spontaneity; reduced sexual interest; reduced expression of emotions; decreased verbal productivity (including mutism); decreased motor behavior.

g) Low self-criticism and judgment: the person have a deficit in judging reality; especially when the situation is new or complex and a lack of critical attitude towards the actions carried out. It also shows difficulty in correcting its errors and inability to modify or schedule new behaviors.

In some syndromes then there are deficits in executive functions; such as in autism and dyslexia; Executive deficits have been detected in attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); schizophrenia and conduct disorder. It is thought that many mental disorders are associated with this type of deficit; although in every disorder it is likely to change the degree to which each component of executive functions is involved. Deficits related to executive functions can be manifested in behavioral symptoms such as: environmental dependence syndrome; with use behavior; that is; as soon as the subject notices an object that he is used to using in a certain way; he uses it; even if the context would require a inhibition of this behavior (eg the subject goes to the doctor and as soon as he notices the window opens it; without a precise reason); and imitation behaviors; that is; the subject spontaneously imitates the gestures of the person in front of him; hypoactivity; such as apathy or anhedonia (in which the person does not perform behaviors that would also give him gratification (such as activities related to food or affective activities); hyperactivity; ie distractibility; impulsiveness; disinhibition. In general; the behavior may appear disorganized [16].

Compared to the diagnosis; however; one must rely on a series of neuropsychological tests; including the Trail making test (versions A and B). The other tests that are most used for the evaluation of the executive functions are: the Tower of London that proves the ability of planning; problem solving and inhibition; the dimentional change card sort test; which is a task that evaluates flexibility; the matching familiar figure test that evaluates the use of visual search strategies; control of the impulse response and interference [17].

Conclusion

The E.F. they represent an important field of research and clinical work in the field of cognitive developmental neuropsychology. There are numerous attempts to summarize the common characteristics of the skills related to E.F.: the ability to inhibit overbearing responses and to organize behavior based on arbitrary rules [18]; the ability of the “central executive” to select the appropriate schemes of action from a repertoire activated by specific inputs [19].

The hypothesis of the multidimensionality of FEs [20-22] is increasingly accepted and several studies are highlighting the evolutionary trajectories of the different subdomains in the typical development; starting to outline a staged process with a complex hierarchical organization. In the clinical field the impairments of the E.F. they are related to numerous cognitive and behavioral difficulties: limited sustained attention; perseverative responses; impaired initiation of actions; poor use of feedback; difficulties in planning and organization; problems related to the storage and manipulation of mental representations. Furthermore; studies on the impairment of E.F. in neurodevelopmental disorders.

These include autism and DGS; in which the E.F. they appear to be pervasive in different domains; severe and pre-existing over time. Other developmental disorders seem to show a more specific profile; with the impairment of some subdomains: the A.H.D.; with the deficit in inhibition; represents one of the most studied cases. For other disorders the research results are more controversial. The differences in the profiles of the E.F. in these disorders they support the hypothesis of a fraction ability of E.F. in subdomains; at least partially independent. It should also be specified that the various subdomains have not been fully studied in all the disorders. Despite these limitations; at least partially specific “executive profiles” of various disorders are emerging [23].

A greater knowledge of these profiles and their evolutionary trajectories; combined with an attention to “ecological validity”; can allow us a greater understanding of the mental functioning of children with typical and atypical development; with potential relapses in the diagnostic and therapeutic-rehabilitative field [24- 26].

To read more about this article: https://irispublishers.com/ctcms/fulltext/executive-functions-definition-contexts-and-neuropsychological-profiles.ID.000507.php

Indexing List of Iris Publishers: https://medium.com/@irispublishers/what-is-the-indexing-list-of-iris-publishers-4ace353e4eee

Iris publishers google scholar citations: https://scholar.google.co.in/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=irispublishers&btnG=

#Current Trends Medical Science#Clinical Science#Medical Science Journals#List of Medical Sciences Journals#Medical Science Research Journals

1 note

·

View note

Text

YOU'RE ALREADY BASICALLY UNDER HOUSE ARREST. THERE IS NO MORE CRIMINAL RELATED TIME TRAVEL POSSIBLE AND THERE HASN'T BEEN FOR AT LEAST TEN THOUSAND YEARS, THANKS TO TEMPORAL CHANGE INTERDICTION FIELDS. READ ABOUT TEMPORAL CHANGE INTERDICTION AND TEMPORAL CHANGE INHIBITION FIELDS AND HIGHER DIMENSIONAL PHYSICS AND MATHEMATICS AND TRANSPORTER INHIBITORS. IF YOU'RE NOT OUT CHASING PHANTOM FICTIONAL CYMEK GOLD CLAIMED TO BE YOURS FOR THE TAKING BY GUYS LITERALLY IN JAIL CELLS AWAITING HANGINGS AND FIRING SQUADS, YOU'LL REMAIN IN YOUR PALACES AND PENTHOUSE LOFTS AND NOT BE OUT WANDERING COMMITING ADDITIONAL CRIMES. WE'D PREFER THAT, ACTUALLY. WHEN YOU'RE WALKING AROUND CLAIMING YOU OWN THE UNIVERSE AND TALKING ABOUT DYING US UP AUDIBLY, THINKING IT'S FULLY COVERED BY FASHO, WHEN IT OBVIOUSLY ISN'T, THAT MAKES US VERY FAFEY, SO OUR ROBOTS RESPOND BY BAFTIING YOUR SNOTTY TIME TRAVELING CRIMINAL ASSOCIATED ASSES. THEY SIGNED YOU UP FOR IT, AND IT'S INEVITABLE THAT YOU'RE GOING THERE EVENTUALLY, BUT YOU COULD AT LEAST DRINK A FEW MORE BOTTLES OF CHAMPAGNE BEFORE YOU NEVER TASTE IT AGAIN, RIGHT? OR WHATEVER GETS YOU OFF. YOU TIME TRAVEL ASSOCIATED FUCKS ARE INTO SOME WEIRD FAGGOT SHIT.

TIME TRAVEL - TIME TRAVELER - TIME TRAVEL TRIAL - TIME TRAVEL TRIALS

#CYMEK GOLD#TIME TRAVEL ASSOCIATED FUCKS THAT ARE INTO WEIRD FAGGOT SHIT#FAGGOT TOM RAMES HIS MOM (SAMANTHA O'REILLY)#POTATOES#POTATO#POTATOS#PAPER#MUSIC BOXES#MASKED FACTORY WORKERS#FABRIKA#STARSHINI#MICHMANI#TIME TRAVEL#TIME TRAVELER#TIME TRAVEL TRIAL#TIME TRAVEL TRIALS#TEXT#TXT#text#txt#JANICE RAWLING#TOM RAWLING#THOMAS ALDOUS RAWLING#CLOCHE#JAILHOUSE LAW DEGREES FOR HIGHSCHOOL DROPOUTS#BATTERIES FOR EXACTO#;#I'M STILL ALIVE AND ALL YOUR FAGGOT FRIENDS AND RELATIVES HAVEN'T KILLED ME BEFORE NOW -- WHY DO YOU THINK YOU HAVE THE MAGIC TOUCH TO?#I AM NOT YOUR ANCESTOR OR RELATIVE -- ALL THE TERRAN TIME TRAVELERS IMPERSONATED THE ATREIDES#ENERGY SIGNATURE OR SPIRIT COVERED WITH PROJECTION DISHUISE MAKING CRIMINALS APPEAR TO BE ATREIDES

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

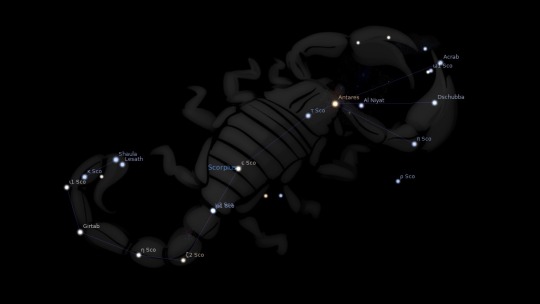

THE ZODIAC: SCORPIO THE SCORPION

Date of Rulership: 23rd October-21st November; Polarity: Negative, female; Quality: Fixed; Ruling planet: Mars/Pluto; Element: Water; Body part: Reproductive organs; Colour: Deep red; Gemstone: Opal; Metal:Steel or iron.

Attempting to make sense out of the eighth sign of the zodiac can sometimes mimic the insurmountable task of trying to answer a cosmological question as to why the universe came into being. If we could equate Scorpio with a physical object, it would be an iceberg. Why, you ask? Well everyone finds it difficult to relax and be uninhibited around an iceberg, especially when you’re on a ship and there’s simply no way of telling what lies beneath the surface of the water, how big it is, and if it will steadfast melt or simply tear a slit into your vessel and sink you. What you see or what you think you see isn’t always what you get, and that tenet is truer of Scorpio than it is for any other sign.

In equating the iceberg with the archetype of Scorpio, the part resting above the water would be the desolate, unapproachable, and cryptic exterior that doesn’t quite lend itself to close investigation for fear of judgement and ridicule, and the larger part beneath the water is the smouldering chamber of power-packed emotions and unconscious images that are left to proliferate there unchecked and are rarely, if ever, vented. Just as the iceberg severs itself from a main body and floats into territories foreign to its own nature, so too does Scorpio show the side of itself that is frequently incompatible with social rituals and codes, alienating it from the joys and benefits of social intercourse. Moreover, ice is a solid, concrete form of water and Scorpio’s watery but fixed nature indicates that it is a sign that can quickly become fixated with things. Scalding is usually associated with heat, though conditions of severe cold such as those facilitated by ice can generate analogous effects. Hence just as heat and cold can scald the skin so too can Scorpio’s behavioural extremes, brooding intensity, and fiery emotional outbursts leave people with psychic burns and scars that won’t easily be forgotten or forgiven. Scorpio, then, is the iceberg that drifts through the cosmic ocean, a block of ice that remains acutely aware of its own temporal existence, vulnerability, and composition while at the same time emanating a snow-white radioactive plume around it that alerts others to proceed with caution, or better still, stay away altogether.

The soul of a Scorpio man or woman is extremely delicate, soft, and pliable. Think of it in terms of a piece of twenty-four carat gold that can easily be bent, twisted, broken in half, amalgamated with other metals, and fashioned into material things that do not accurately express the spiritual worth of ‘gold’. Being the intuitive and proud gem that it is, Scorpio knows this and inherently feels that it’s only viable recourse is to raise gargantuan walls and set cunning traps in the immediate vicinity around itself as to thwart any foreign invasion which seeks to dismantle its bubbling motivations and innermost desires. The type and nature of defences employed by the Scorpion to ensure this never comes to pass varies from person to person, however one that exists in the arsenal of all is a belligerent, angry, and red-coloured force field that will not allow another cheap laughs at its own expense. In the mind of a Scorpio, any deliberate attempt to humiliate, threated, scold, or tease, vilify and slander either itself or a fellow conscious projection of the universe violates the most vital of moral codes and deserves shameless retaliation.

As we have thus far discerned, Scorpio possesses an innate sensitivity that renders it receptive to even the slightest changes in external temperatures and environment. Thus it seems only natural that the sign might become unnecessarily fixated on trying to control and manipulate everything around it for the sake of lessening its anxieties and maintaining harmony of its inner empire in the manner that a chess player strategically positions pawns, knights, bishops, and rooks to defend an inner sanctuary epitomized by the royal couple. Like the latter, souls incarnating under the stars of Scorpio enjoy playing games in which they can draw like-minded others into their private little worlds, identify their psychic dowry and talents as well as the positive and negative elementary characteristics of their personality, and henceforward advise them on what course of action and karmic life choices they should make. Scorpio enjoys proposing unsolicited makeovers that they believe will emphasize another’s finest characteristics, inside and out, and can be quite intrusive in prying for information that it perceives to be of utmost importance to the wellbeing of its significant other, its loved ones, and itself. Being the control freak that it is, Scorpios are aversed to and become apprehensive around obstinate and autonomous persons that will steer clear of Scorpionic manipulation, especially when the individual concerned is their own partner. Like its close cousin Cancer, Scorpio doesn’t like to be confronted about the way in which it operates or the manner in which it chooses to live its life and will often go to any length to protect its emotional security and hold onto the few momentous others that comprise its cryptic and often unintelligible chess game.

“One thing you’ll really like about me,” says Scorpio, “is the fact that I’m very understanding. I understand the conflict of interests between the outer and inner landscape that can cause one to feel like a social misfit, a reject, a loser, or simply undesired and unwanted. I don’t judge people who are different from the conforming majority; on the contrary, I embrace and honour them. I’m also really good at fixing things. I simply love to pick at something until it’s either fixed or it vanishes from the face of the earth. I’m also intensely self-aware. I’m aware of gestures, subtle energies, actions, and implications that often move in the opposite direction to that of the spoken word and might have their own story to tell. Really, I haven’t got a problem in diving down into the abyssal depths of the human soul, perusing an inner darkness that contains the carnal impulses, compulsions, instincts, and latent desires within you, and then re-emerging into the conscious light to reveal how your outer landscape will inevitably undergo a metamorphosis for the worse if you don’t confront it.

Life is about experiencing this world, but it is also about learning how to die and resurrect throughout the course of one’s lifetime in order to expand the psychic and spiritual fields of our collective consciousness. Alchemically speaking, we might say it involves a threefold cycle: necrosis, the corruption of death; leucosis, rebirth through intuition; and iosis, the conciliation of conscious and unconscious elements that leads to the much desired ruby-red state of illumination. We must all come to terms with the insecurities, hostilities, and boiling obstructions within the depths of our being that set this cycle into motion, as well as find a way of reconciling these qualities with our conscious personalities in order to attain closure. Why, you ask? Well in my search for the truth I have acquired a hunch that there are other dimensions of existence beyond our physical one, and so the plight of each human being should be to purge oneself of murky, carnal qualities that go far in inhibiting the attainment of illumination, inner purity, freedom and most importantly, unalloyed love. I, for one, come into the world karmically prepared for the emotional tribulations life will inevitably throw at me, and I know of no other sign that experiences such cheerful bliss, soaring through the boundless skies like a carefree eagle, when these obstacles are finally overcome.

Like every animal on this planet, I enjoy having sex and will often engage it purely to release tension and other psychic steam that has been collecting in the confines of my subconscious for weeks if not months. Hence, anyone lucky enough to tango with me will share in the providential gift of a mind-blowing and positively uplifting experience. I’m not ashamed to admit that I’ll use sex as a method of exploitation, but one should never take me for easy, and I’m not particularly interested in dispassionate and no-strings-attached casual sex. For me, sex is extremely sacred and must involve love and intimacy between two people who care for one another otherwise the act becomes pointless and futile.”

There are two symbols associated with the zodiacal sign of Scorpio. The animal totem that represents the first of these really does correspond to the distribution of stars in the sign’s constellation, and it appears that all ancient cultures from the Chaldeans, Babylonians, and Indians to the Egyptians, Hellenes, and Romans were in unanimous agreement about this. The most significant stellar body in this vivid star group was Antares, a bright eye otherwise known as the Heart of the Scorpion and inextricably linked with the war god Mars. In ancient Egyptian cosmogony, Scorpio was ascribed prominence as the constellation of Seth, the primordial god of destruction, irruption, anger and chaos. In a book by archaeoastronomer Jane Sellers entitled The Death of Gods in Ancient Egypt, astronomy, archaeological evidence, and mythography come together to reveal that the eighty-year battle between the gods Horus and Seth had a precessional basis, the question being which constellation of the equinoxes, Scorpius (Seth) or Taurus (Horus), would gain the ascendency after Orion (Osiris) had been obliterated from the night skies of the northern hemisphere. Given the fervent preoccupation of our ancient ancestors with celestial events, the Predynastic Egyptians would have envisioned a harmonious balance in the annual circuit of the sun when Taurus (Horus) marked the spring equinox and Scorpio (Seth) marked the autumnal equinox. This was something of a Golden Age, a locus classicus when the v-shaped bovine head of Taurus manifested by the Hyades rose heliacally over the eastern horizon at the vernal point just before sunrise and the arachnid-like form of fiery Scorpio reappeared there exactly six months afterward to herald the autumnal equinox. According to Sellers, this Golden Age would have occurred between c. 6900-4867bce before the relentless yet subtle effect of the precessional cycle knocked it all out of allignment.

The second, an astrological shorthand for the zodiacal sign utilized by astrologers in the creation of astrological charts, looks like the small letter “m” save for the fact that the third leg terminates with an upturned arrow. Many astrologers and symbologists have attempted to anatomically define the contemporary sigil, though it appears that none of the suggestions are wholly convincing. Hypotheses linking the modern shorthand symbol to the male reproductive organs, a severed scorpion tail, the tail of the Christian devil, the tail of a mythical dragon, and a coiled serpent have all been proposed. This particular symbol has undergone many changes through time. In Egypt, four demotic tablets were uncovered that recorded days and months in which the five visible planets entered the zodiacal signs over a twenty-eight year period. These revealed that the shorthand symbol used in ancient Egypt was a snake. Alternatively, medieval treatises show an actual scorpion.

In the northern hemisphere Scorpio appears at a time when the formative forces of Mother Nature are at their weakest, but it is also a time of turbulent change when fermentation has commenced and the scales are about to tip towards the proliferation of life energy. Evolving around the rudimentary myth relating the passions of the beneficent Osiris, ancient Egyptian belief ascertained that the latter suffered death and descent into the netherworld beneath the stars of the vigilant Scorpion. In Peri Isidos kai Osiridos, we learn that Osiris’s penis was the only body part that wasn’t found his wife, the mourning Isis, who solved the enigma of how she might conceive a son posthumously by equipping him with one hewn from a piece of wood. The myth’s preoccupation with the reproductive organs, sexuality, and resurrection fits in well with Scorpio as a spiritual archetype intensely preoccupied with the cosmic cycle of death, transformation, and rebirth.

The Scorpion exudes an energy which works in indirect and often cryptic ways. Consequentially, this sign is one of the most misunderstood in the zodiac and will more often than not encounter hostile adversities and reactions from those that cannot comprehend the benevolent intent indigenous to the Scorpion’s nature. Having said that souls incarnating under this sign possess a psychic dowry that enables them to handle and cope with such situations, for one can be sure that the universe will never impose a blueprint onto something or someone unless it is sure that that something or someone can survive experiences and consequences that might be simulated as a result. When looking at the zodiacal image and the symbols as a whole, one intuitively feels that the poisonous stinger and sharp arrow imply sharp qualities and sentiments that cut like glass such as adroitness, cleverness, and smooth-tongued straightforwardness. They also recalls the Stygian depths of Scorpio’s psyche, a raw, windswept, and multifarious breeding ground of passion, charm, astuteness, creativity, intensity, and both sexual and romantic love. These fiery traits can be attributed to the immanence of Plutonian energy in the sign, a prominent planetary position formerly held by Mars.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Natural History and a Unified Museum Definition

By Eric Dorfman

Much is being said within the museum industry about the definition of museums. ICOM is considering the current definition and whether it needs to be rethought. I think a review is worthwhile, regardless of whether changes are ultimately made. Robust thinking about museums (or any field, in fact), whether related to practice or theory, should be based on the intrinsic nature of the field. Defining museums is a critical step along that journey.

For natural history institutions, whose main business is to study and interpret the diversity of life, the relationship between museums and the state of the Earth must by necessity play an important role in constructing a definition. At the very least, an exploration of this relationship provides a context for natural history museum collections and, at best, it has the power to incite people to explore their identity and connection to one another through the prism of nature.

To some degree, natural history museums can be defined by what they do. At Carnegie Museum of Natural History, we have defined our work through three distinct but interrelated lenses:

The Tree of Life: The study of evolutionary relationships among taxonomic groups,

The Web of Life: The collection-based and in situ study of ecological systems,

The Future of Life: The study of the trajectory of species, populations and ecosystems, especially in the context of anthropogenic disturbances, as well as actions to ameliorate those effects.

The collections and other infrastructure provided by our museum support this work and the story-telling that arises from them.

While the study of evolution and ecosystem relationships is the traditional work of natural history museums, the future of life bears further consideration. By most measures, conditions on the planet we bequeath to our descendants are highly uncertain. Even discounting the seemingly inescapable reality of a future effected anthropogenic climate change, many factors inhibit our predictive ability. Will we run out of power or meat? Will plastic and mercury pollution render produce from the oceans inedible? Will at least some of the planet run out of water in the face of increasing desertification?

These are “wicked problems” (Churchman 1967; Levin et al. 2012) – issues that have so many facets we cannot know the answers, but for which at least some of the alternative outcomes are negative. The interrelationships between these issues create bewildering complexity.

These effects have been recently amalgamated into the concept of the “Anthropocene”, a proposed geological era that reflects human impacts so pervasive as to influence the geological record. These effects will be detectable millions of years from now, by whoever might be looking, as an unprecedented band of plastics, fly ash, radionuclides, metals, pesticides, reactive nitrogen, and consequences of increasing greenhouse gas concentrations (Waters et al. 2016), as well as highly modified fossil composition, featuring an overwhelming preponderance chicken bones.

How does this ‘Age of Humanity’ structure our visitors’ perceptions and help them phrase questions about their environment? How will it influence our research? Most germane here, how does lack of certainty about the future of the planet influence the museum definition as it pertains to natural history institutions?

A Natural History Perspective

Fifteen of the world’s top natural history museums collectively contain, at rough estimate, almost 570 million specimens[1]. This represents the largest category of collection across the museum industry. Collections underpin the field. Any discussion of a unified perspective of natural history museums must therefore take into account the fact that collections form the basis of much of that is undertaken by natural history museums. This focus on collections, often from deep time, intertwines physical and temporal considerations:

Natural history museums and their collections are often thought of in terms of the past, which is not surprising. We are probably the only scientific research facility that can claim the ability to time travel, albeit in a patchy and far from perfect way. Our business is intimately connected with the past, both recent and deep time, and much of what humans know about the natural world a hundred, a hundred thousand, or a hundred million years ago arises directly or indirectly from the specimens held in our collections. When your child states with certainty that Tyrannosaurus rex lived in the Cretaceous they are, knowingly or unknowingly, drawing on the results of research done using museum collections. Norris, 2017, p. 13.

Norris (ibid.) follows this with a comment: “There is, however, a considerable difference between studying the past and belonging in the past.” Natural history institutions also focus strongly on the present and future and use information about the past uncover, contextualize and predict changes in the world around us.

Natural history museums, sitting at the crux between nature and its artistic representations have an important place in facilitating exploration of personal identity. Inasmuch as enhancing self-perception can have a positive influence on behavior, (see Falk, 2009), natural history museums’ capacity to contribute to society increases as their activities in this sphere become more purposeful. Those visitors who care about wildlife, and there are many, want natural history museums to deepen and expand their understanding. Museums like to feel that they occupy a place of credibility in the hearts and minds of the public that other channels of information, for all their worth, do not (but see Museums Association, 2013). Whether we truly are more credible than other types of institutions or not, our self-perception provides a significant opportunity to strive for best practice.

Albert Bierstadt: Rocky Mountain Landscape

The grounding of natural history museum practice in the study of physical specimens means that these institutions have at least a goal of objectivity, however influenced by curatorial subjectivity the framing of questions can sometimes be (see Dorfman, 2016). The articulation of evidential knowledge, concern over changing political environments, even in quality of governments themselves, is not new, nor restricted to the museum field.

How are museums responding to the melange of environmental, sociopolitical and technological changes that that are beginning to set the context in which they operate? Customer focus and using people’s own languages, both culturally and linguistically, to communicate touches every aspect of activities at natural history museums, including exhibitions, marketing, strategic planning, science, cleaning regimes and providing sufficient seating. Conflating individuals’ perspectives into stereotyped offers based on age, gender, race, socioeconomic background, sexual orientation undermines the relevance on which natural history museums pride themselves. Every institution has the opportunity to provide leadership in the sense that Covey (2005) wrote “…leadership is communicating to people their worth and potential so clearly that they come to see it in themselves.”

For natural history museums, the unique signature of our industry is formed by using collection-based and in situ research to elucidate evolutionary and ecosystem relationships, as well as the intersection of these processes with humanity and its impacts, and then facing these stories outwards to the public. For all the many facets of the work of natural history museums, this is the most important and the aligned with our mission.

The Definition Through the Eyes of Natural History

The current definition of a museum as provided by ICOM is as follows:

A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment. (ICOM Statutes art.3 para.1)

At first blush, much of the definition of the definition as it stands is generic enough to include natural history museums. One question, however, that comes to mind is how well the term “humanity and its environment” fits the practice and perspective of our industry. For one thing, any organism that existed before the evolutionary rise of Homo sapiens (~2mya) could, by this definition, be considered irrelevant to the work of museums. While this is patently not the case, a careful review of the definition should take this wording into consideration.

This semantic argument notwithstanding, the implicit question embodied in the words “its” poses a deeper consideration, namely the ideological friction between the notion of ecosystem valuation versus that of the intrinsic worth of nature. Both these perspectives have their strong adherents.

Formal cost-benefit analyses and the generation of market value were first developed in 1997 by Robert Costanza, Distinguished University Professor of sustainability at Portland State University, Oregon, building on earlier discussions of economic benefits of the environmental (e.g. Rolston, 1988). Constanza and his colleagues calculated that such services were worth US$33 trillion annually, or US$44 trillion in 2019 currency (Constanza, 1997). The rationale for undertaking this exercise is that ecological system services and the natural capital stocks that produce them are critical to the functioning of the Earth’s life-support system for humans. They contribute to humanity’s welfare, both directly and indirectly, and therefore represent part of the total economic value of the planet.

Since then, the field of environmental economics has proliferated and non-market valuation has become a broadly accepted and widely practiced means of measuring the economic value of the environment and natural resources. A variety of methods, including opportunity cost, travel-cost, hedonic price and contingent valuation have been applied in highly nuanced and complex models (e.g. Weber, 2015). In most, but not all cases, environmental goods and services are geared solely toward protecting inter-generational human welfare. For instance, considering mangrove ecosystems, benefits might be characterized by direct ecological yield in the form of fish or timber, contrasting with indirect value, such as filtration services and storm protection. There is also a line of reasoning that suggests that sentimental or “existence” value: simply knowing something exists provides a distinct, discernible benefit (Krutilla 1967).

An opposing viewpoint lies in the philosophy that nature has intrinsic worth and that the environment should be protected based on its own merits without reference to real or potential benefits for humanity (McCauley, 2006). This viewpoint is strongly based in environmental philosophy and ethics (see, for instance Callicott’s 1992 criticism of Rollston, 1988).

Young humpback chub (Gila cypha) swimming in Shinumo Creek, inside Grand Canyon National Park soon after release. They are part of a reintroduction program of this federally protected species with the goal to establish a second population, after they became extinct everywhere except a small part of Little Colorado River. Photo: Melissa Trammell, NPS

For instance, in discussing conservation efforts of the humpback chub (Gila cypha) a large minnow with no value to humans, native to the Colorado River, Smith (2010) suggests that all currently existing (biological) species have their own intrinsic goods, framed in terms of their ability to flourish. Based on this ethical stance alone, it could be argued that even a species like the humpback chub, that competes successfully with economically important introduced species (such as rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss), should be preserved.

The work of natural history museums is firmly rooted in this second philosophy. For one thing, much of the research we do is based on advancing knowledge for its own sake or, like the example of the humpback chub, taking conservation action out of professional ethics and a moral sense that it is the right thing to do. Additionally, natural history institutions, like other types, use the museum medium of engagement to instill empathy with the subject. In the introduction to her book Fostering Empathy Through Museums, Elif Gokcigdem highlights this necessity:

…Having visibly altered our planet’s outermost layers, scientists are debating whether our footprint is worthy of naming an entire geological epoch on Earth’s billions-of-years-old timescale after ourselves: Anthropocene, the Age of Humans… A steady proliferation of new and ever more powerful technological tools seems unable to correct these ills. One must wonder why they have not succeeded. I believe it is because the tools that are at our disposal are most beneficial when filtered through a worldview that values the collective well-being of the “Whole” – our unified humanity and the planet, inclusive of all living beings as well as of its life-supporting natural resources. Such a unifying worldview cannot be attained and sustained without empathy, our inherent ability to perceive and share the feelings of another. (Gokcigdem, 2016. xix)

Connecting people both intellectually and emotionally to the world’s major stories sits firmly within the scope of work of museums. The opportunity to bring people outside themselves to engage more deeply with the world is an element of the definition of that should be incorporated across all its nuanced facets. If the definition of museums chases, these considerations should sit beside many others as influencors of the conversation.

Eric Dorfman is the Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Footnote

[1] Information taken from the websites of the following museums: Smithsonian Museum of Natural History: 137 million; Natural History Museum (UK): 80 million; Jardin des Plantes: 68 million; Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History: 35 million; American Museum of Natural History: 32 million; Naturhistorisches Museum: 30 million; Field Museum: 30 million; Museum für Naturkunde: 30 million; California Academy of Sciences: 26 million; Carnegie Museum of Natural History 22 million; Australian Museum: 21 million Harvard University Natural History Museum 21 million; ; Natural History Museum of Geneva 15 million; Yale Peabody Museum: 13 million; Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales: 6 million. No attempt to verify these figures has been made.

References

Callicott, J. B. 1992. Rolston on intrinsic value: A deconstruction. 1992. Environmental Ethics Vol. 14. Number 2. 129-143.

Churchman, C. W. 1967. Wicked problems. Management Science, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. B141-142.

Costanza, R., d’Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R. V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R. G., Sutton, P., van den Belt, M. 1997. ‘The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital,’ Nature, Vol. 387, pp. 253–260.

Covey, S. R. 2005. The Eighth Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness. New York, NY: Free Press.

Dorfman, E.J. 2016. Who owns history? Diverse perspectives on curating an Ancient Egyptian Kestrel. Taipei: Proceedings of the International Biennial Conference of Museum Studies Commemorating the 80th Birthday of Professor Pao-teh Han 30th and 31th October 2014.

Dutton, D. 2009. The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure and Human Evolution. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Falk, J. H. 2009. Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience. New York: Routledge.

Gockigdem, E. 2016. Fostering Empathy Through Museums. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Krutilla, J. 1967. Conservation Reconsidered. The American Economic Review, Vol. 57, Issue 4, pp. 777-786.

Latour, B. 2015. Telling friends from foes in the time of the Anthropocene. In: The Anthropocene and the Global Environmental Crisis: Rethinking Modernity in a New Epoch. Edited by Hamilton, C., Bonneiul, C. and Germenne, F. London and New York: Routlege.

Levin, K., Cashore, N., Bernstein, S., and Auld, G. 2012. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 123-152.

Louv, R. 2011. The Nature Principle: Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

McCauley, D. J. 2006. Selling out on nature. Nature 443(7107), p. 27.

Museums Association. 2013. Public perceptions of – and attitudes to – the purposes of museums in society: a report prepared by BritainThinks for Museums Association. Museums Association, London. http://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=954916 accessed January 13, 2019.

Norris, C. A. 2017. ‘The Future of Natural History Collections,’ in The Future of Natural History Museums. Edited by Eric Dorfman. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 13-28.

Oxford Dictionaries. 2019. Word of the Year 2018 is… Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2018, Accessed January 13, 2019.

Rolston, H. Environmental Ethics: Duties to and Values in the Natural World. 1988. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Smith, I. A. 2010. The Role of Humility and Intrinsic Goods in Preserving Endangered Species: Why Preserve the Humpback Chub? Environmental Ethics. Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 165-182.

Waters, C., N. Zalasiewicz, J., Summerhayes, C., Barnosky, A.D., Poirier, C., Gałuszka, A., Cearreta, A., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E.C., Ellis, M., Jeandel, C., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J.R., Richter, D., Steffen, W., Syvitski, J., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Williams, M., Zhisheng, A., Grinevald, J., Odada, E., Oreskes, and Wolfe, N. 2016, The Antrhopocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene. Science, Vol. 351. No. 6296, p. 137.

Weber, W. L. 2015. Production, Growth and the Environment. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group.

Weil, S. 2002. Making Museums Matter. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

White, M. 2000. Leonardo: The First Scientist. London: Little Brown.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Museums#Natural History Museum#Natural History#Anthropocene#Defining Museums#ICOM#Philosophy#Ethics

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An Introductory Teaching on Taking Refuge (2 of 2)

by His Holiness the 41st Sakya Trizin

The very first step in practising the Dharma is to take refuge. There are five aspects to taking refuge: the cause of taking refuge, the object of refuge, the way to take refuge, the benefits of taking refuge and, lastly, the rules of taking refuge.

The first aspect, the cause of taking refuge, we have already discussed in the previous issue.

So now, we will look at the second aspect, the object of refuge. The object of refuge is the same for all Buddhists, whether they belong to Hinayana, Mahayana or Vajrayana. All Buddhists take refuge in the Triple Gem. But on closer examination, there is a difference. According to Mahayana, and also to Vajrayana, when we say Buddha, we refer to someone who is totally awakened, someone who has become free from all forms of obscurations - the obscuration of defilements and the obscuration of knowledge, including their propensities. Someone who has attained the highest qualities, and who possesses the three kayas.

Of the three kayas, or bodies, the most important one is the Dharmakaya. Dharmakaya means the ultimate truth, or the true nature of all phenomena – it is similar to the Dharmadatu, or ultimate reality, which is totally free of all obscurations. It is also called double purity. Double purity means not only the basic purity that everyone possesses, but also purity in the sense that all temporal obscurations are also totally eliminated. And such a state is realised through awareness, or through primordial wisdom. Such a state, the primordial wisdom that realises ultimate truth, which possesses double purity, is the Dharmakaya. So that is the most important body. And because They have attained this, the Buddhas have gained all the qualities and have eliminated all forms of obscurations. And so, in order to help sentient beings, and while ceaselessly remaining in this state of Dharmakaya, They appear in a form - but the Dharmakaya is actually formless, it has no form, it is beyond description, it cannot be comprehended by our relative minds.