#Revolutionary France game

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Arno's Darkest Hour: Expelled From the Brotherhood?

#Assassin's Creed Unity#AC Unity Bottom of the Barrel#Assassin’s Creed Unity walkthrough#Assassin’s Creed Unity story#Élise and Arno#AC Unity Louis XVI#AC Unity Versailles#Revolutionary France game#Assassin Brotherhood expulsion#Dame Z Gaming#Youtube

0 notes

Text

I'm losing my fucking mind.

In the last years, my university has been tagged multiple times with racist and neo-nazi symbols. The local of our union against racism and pro lgbtq+ was destroyed multiple times. Nothing was done, but a bit of paint to cover it up. No investigation. No punishment. And when I vocalised my discomfort, I was told it was nothing, just "immature young people trying to get attention".

Last year, the prefect of Paris authorized a Neo-Nazis' protest. Neo-Nazis walked in Paris, freely, as if it's not illegal to express racism or nazi rhetoric in this country. People weren't happy, so the prefete said it would not happen again.

Well, for the 21st of April, multiple protests against racism were organized all around France, and, they were not authorized by the authorities. The same prefect that let, a year ago, Neo-Nazis in the street of Paris, refused to let a protest against racism walk those same streets. He said "It's antisemitic. They support Palestine, they are antisemitic.". Yeah, take us for idiots, the protest against racism is going to be too antisemitic but not the Neo-Nazis you let walk around (and we know he would do it again).

And now, we have Sciences Po, one of the most reputable universities in our country, joining the movement the USAmerican students have started. The Sorbonne, another reputable university, followed. The French gov and media cried about it, called them "terrorists", "uneducated", "revolutionaries" (this one is crazy and really shows the fascism behind it all. We are in France, being revolutionary is NOT a bad thing in our culture. Wtf would you use "revolutionary" negatively in France, unless you are an oppressor?!!!) Students who are calling for the end of Genocide and just sitting on the ground! The cops were sent and dragged them out. For information, the cops CANNOT intervene in an university in France without the authorization of the president of this university. Not even the gov can make the cops enter an university, it's illegal. When students protest inside an university, people don't like seeing the cops being send after them. Two reasons: 1- students have often protest and help for the quality of life of everyone in French history, 2- WWII's trauma, Nazis stormed French universities because they were hiding Jews and resistants. Like, they are straight up acting like the Nazis, again. And the city of Paris wants to cut the budget they give to those two universities to punish them for not keeping their students in line. So, freedom of speech? GONE.

Students are protesting against a massacre, and they are calling them antisemitic. People standing against racism is antisemitic. But not the people branding Neo-Nazi symbols and chanting Neo-Nazi slogans. They don't move if you are branding a swastika, which is illegal, but will if you are branding Palestine's flag, which is not (yet). They let a political party founded with a SS go around and act nice, but the ones asking for the end of a massacre are the Nazis. Make sense.

So, I'm fucking pissed. I'm fucking pissed because I was told to "calm down" when I couldn't stand the antisemitism paint on my university, when I couldn't stand being friendly with the students that did or support that (because I did meet one). I was told to ignore antisemitism and I refused, and now, they call me antisemitic for standing with Palestinians?! How dare they when they tried to gaslight me so I would ignore the antisemitism in front of me?!

They don't care about jewish people! It's not about jewish people or the jewish faith, it's about white supremacy!

The people have already planned to protest during the Olympic Games, because the French gov is going full fascism lately (everyday, we wake up to more bs), and I hope with all my heart that we ruin the event at least (which would harm them financially), and at best, we get rid of the government and this 5th republic.

#free palestine#france#Palestine#france in the last year: time to speedrun fascism#it's crazy here they are losing their mind I'm losing my mind#what do you mean children are going to go to class from 8a.m. to 6p.m. 5 days a week??? wtf are they working more than adults#and the swimmers at the Olympic Games are all going to fall ill because the Seine's water are awful and not safe at all#also they want to control who can enter Paris and even the people living there could be refused to enter if they are “dangerous”#being dangerous = not agreeing with everything the gov does btw#and they deported homeless people out of Paris DEPORTED no they didn’t give them homes they just forced them into bus and kicked them out#yeah I'm being full on revolutionary again but it seems to be the last option with them

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#steelrising#nacon#spiders#playstation 5#automaton#paris france#revolutionary france#french revolution#king louie XVI#marie antoinette#soulsborne#gif edit#dailygaming#dailyvideogames#gaming edit

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know someone who calls herself a feminist, puts her pronouns in her work email signature, donates money to women’s empowerment funds, and thinks we should deport more refugees. I also know someone who calls people ‘pussies’ when he plays video games, who doesn’t know what a pronoun is, and, for his defence of low-wage women workers in a highly-exploited industry, is a better, more strident defender of the rights of working-class women than almost anyone else I know. Of these two people, I know who is on my team, and who I want on my team, yet the standard liberal feminist calculation would have me chose the woman who loves a little deportation over the man who is occasionally uncouth, solely because the woman knows to keep her language civil, and the man doesn’t. Liberal feminists get incredibly caught up in the politics of language, because language is all they have. They don’t have a revolutionary programme for overthrowing patriarchy, so they’re forced to tinker around the edges of it, quibbling over word choice and jargon instead of building the coalitions necessary for destroying patriarchy.

— We Should Not All Be Feminists by Frances Wright

41K notes

·

View notes

Text

been very slowly watching the movie the last duel in between work shifts for the last fays and i respect that unlike other period dramas that try to make people attractive and dressed in a way that appeals to modern viewers this one is just gives all the men absolutely terrible haircuts and covers them in dirt. other thoughts include: i greatly enjoy when movies are split into chapters and also told from the perspective of unreliable narrators so this is up my alley, jodie comer is ethereal and i'm obsessed with marguerite's hairstyle with the hoops of braids around her ears, ben affleck is honestly giving an extremely good performance as a medieval airhead, the lack of commitment to accent is STUNNING (there has been MAYBE one character who had a french accent?? but she only had one line of dialogue so it was hard to tell) and this movie is mostly very grim and heavy but i find a measure of entertainment in watching the king of france's expressions whenever he turns up and how obvious it is he just really wants to watch two guys fight to the death.

#the reason i am watching this is bc my sister was reading a book with unreliable narrators#and was like wow i love unreliable narrators which caused me to go hmmm any good movies about that out there???#at the rate i am watching this movie i expect i will be done in like. a week#oh and also it made me realize i was made to watch the imitation game too many times in high school#bc i immediately knew the king of france was both young alan turing and also that revolutionary in andor#pie says stuff#the last duel#movies

1 note

·

View note

Text

So I want to talk about the Olympic games opening ceremony.

Apparently it's been watched by 1 billion people around the world, so this spectacle promoting queer relationships, women and revolutionary ideals must show quite a progressive picture of France. The fact that so many fascists are crying over it must make it good, right? Right?

We saw statues of important women in the ceremony, like Simone Veil, Louise Michèle and others. I'd like to remind people that today, many of these women would be on the file compiling terrorists and potential terrorists. You know, like so many people who happen to be leftist activists and learned they would not be able to work for the Olympic games or attend them when they tried. For past acts of activism that date years and never resulted in convictions most of the time.

All around the ceremony, LVMH, that luxury brand, was everywhere. Bernard Arnault (currently richest man on earth) surely grabbed the spot for these games. What a great ad for his brand.

The ceremony, which was presented as a "street ceremony for the people" actually only included a few privileged people able to spend 2,000€. The city was empty. The city is empty.

They locked up kilometres and kilometres of the city, where only few can go. Paris is barricaded. Some hospitals have become inaccessible.

They sacked so many homeless people so that the tourists wouldn't see them. Who knows where they are now. They sacked students from their homes too, before even the end of exams. And when the police came and took their rooms, they complained about the housing conditions. Well that's how our students live all year, but that's not a problem then.

And then I could talk about the surveillance conditions, Macron's friendship with the worst world leaders, that they tried (and failed) to make the Seine swimmable by spending billions on it meanwhile people in the colonies over-sea regions still don't have drinkable water. I could speak about the work conditions, that most of the work was made with undocumented workers and so. Much. More.

But that would be a very long post.

So after seeing this opening ceremony and all the great, progressive messages it carried, what you need to remember is this.

France is a police state.

France is a classist country.

France almost elected the far-right to power less than a month ago, and the far-right is still more powerful than ever.

France is a queerphobic country. And a very, very transphobic country.

France is a racist country, where Arabs get murdered while barely making regional news.

France is nothing like what we showed.

That was propaganda at its finest.

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let me talk Church and the Revolution

Okay, let me post this preemptively. Because I already know that soon enough those people looking for reasons to hate on Castlevania Nocturne because it is not like the games will also come to cry a river about "they depict the church as evil!!!!"

So, let me quickly talk about the role of the church in the French Revolution. Because there is something you gotta understand about the Church during the French revolution: That there was not THE Church.

Basically within the Catholic church in France there was a fracture over the entire revolution happening. A lot of the higher ranked clergy men stood on the side of the nobles and royals, while a lot of the lower ranked clergymen stood with the revolutionaries. The reason behind that mostly was money.

See, before the revolution the church was allowed to collect taxes themselves, while also being tax exempt. So they did not have to pay taxes on all the stuff they sold and made to the nobility. Which was why the bishops and general higher ups within the church could have the lavish lifestyle of nobility themselves, often of course ignoring their vows.

Meanwhile a lot of lower clergy (and especially certain groups of monks - especially the franciscans) were like: "We are all equal in the eyes of god. Rich folks do not get into heaven. Equality is what god wanted from us" and supported the revolution because of it.

But of course there was also the thing that the show mentioned: Given the show is set in summer it seems (probably just before the Reign of Terror) it would have been not even a year before that a lot of clergy got slaughtered. Why did they get slaughtered?

Well, short explanation: Royalists and also some of the bishops provoked the war with Prussia in an attempt to overthrow the revolutionary forces with the help of the Prussian military. This of course failed and the revolutionaries were out for blood. So nobles fled into the churches for sanctuary. And in retaliation a lot of clergy died for haboring the nobles in question.

And, yeah. There is of course the other aspect: The church at the time for a lot of historcal and religious reasons very much supported slavery. Meanwhile this is already a point where the revolution at large had decided that slavery should be done away with. And that leads to what we see in the show here: Clergy going on about the revolution being against "the natural order".

(Being frank: I LOVE that they brought this into the show. Which is almost like a whole other thing I could write about. The entire idea of the revolution and the "natural order" and how it is all linked to colonialism.)

Another interesting part here is the order the abbot and Mizrak are from. On the Castlevania discord server I already went into a whole thing trying to figure that out, but my last idea was right: They are from the Knights Hospitaller. The order of St. John.

This order arose during the crusades and as the name Knights Hospitaller suggests: Yeah, they mostly created hospitals (though historically those were not only to cure the sick, but also to be a home - "hospitality" - for those on the road). They were based in Jerusalem for a while, but ended up moving to Malta, which was of course for a long while ruled by France. They referenced here that the Abbot came to France from Malta, which is the reason.

But yeah, they actually were about helping people for the most part. But they also made money from it. And when the revolution came, they seized all the assets from the order, which made the order join into the ranks of clergy who stood against the revolution by 1792.

#castlevania#castlevania netflix#castlevania nocturne#french revolution#european history#christianity#knights hospitaller#france#malta

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

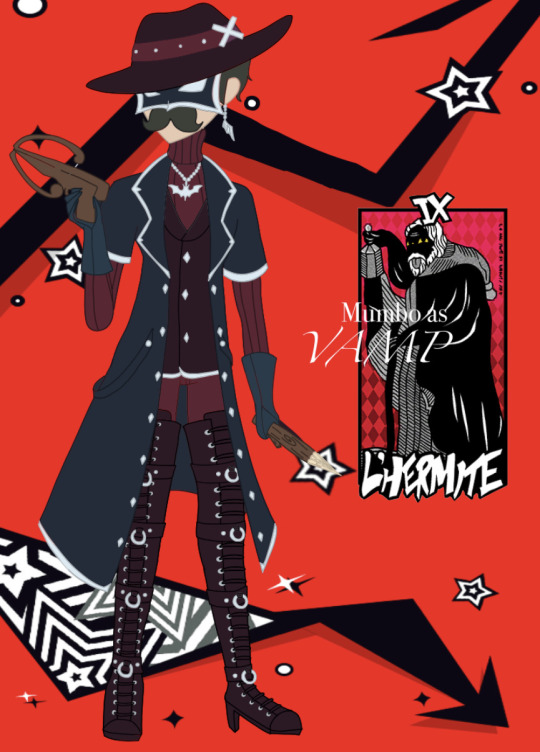

Persona 5 AU anyone? No? Just me? That’s fine.

Anyways, welcome to an AU that’s been bouncing around my head for nearly a year now! It was inspired by @/chrisrin’s take on the MCYT x Persona series as well as @/scruffyturtle’s ACAU! Go check ‘em out!

Team B.E.S.T.

The Scottage + Gem

Fairy Fort

Magical Mountain + Cub

More Information is under the cut!

Grian - “Ace” - The Sun Arcana - Lafayette/Eris

Grian is a college student working for a degree in architecture. He lives with in roommate Mumbo and does journalling and photography as a hobby. For some odd reason however, he can’t seem to remember anything about his past beyond simply going to college, doing a part time job, and spending time with his cousin and friends. This is because Grian isn’t really human. In this AU, the Watchers take the role of Yaldaboath, and created Grian to begin the mental shutdown cases to scare people into looking for someone to look towards. In this case, The Watcher Cult (Called the Pupils) for the Watchers to take control. During his creation, false memories were implanted in certain people in the Pupils for Grian to more seamlessly appear. But unbeknownst to them, the Velvet Room interfered and erased Grian’s memories of his purpose.

Anyways, onto the personas, Grian’s persona is Lafayette, a key figure in the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolution. In both wars, he was known to lead his armies in decisive battles of the war to secure their victory. Even today, he’s celebrated as a hero in both France and in the US. This fits in with canon Grian’s habit of rebelling against any governmental entity that’s in the Hermitcraft server (although he is currently the government) l

His Ultimate persona is Eris, the Greek goddess of chaos and strife. She was the instigator of the Trojan war, where she threw at apple at Aphrodite, Hera, and Athena. She stated that it was for the “fairest goddess” and one thing led to another, and several kingdoms are now at war with each other. Wow, starting a war for shits and giggles? That sounds like Grian!

Jimmy - “Sheriff” - The Fool Arcana - Black Bart/Baldr

Grian’s cousin and charmingly unlucky, Jimmy is often the target of teasing. He’s the one to egg Grian on to actually go to class instead of just doing the online assignments. He’s personally seeking a degree in education, and is a stickler for the rules he agrees with. Unbeknownst to him, he was a victim of the Pupils and one of the people that had false memories implanted in him. He’s extremely excited about being a phantom thief, but his joyous excitement will be tested through the story.

His Persona is Black Bart, an American Outlaw who is known for the poetic messages he left behind after two of his stagecoach robberies. He is considered a gentleman bandit with a flair for style and sophistication. He brandished a shotgun, but was noted to never fire it during his robberies. He was famed to the point there is an annual parade in Redwood Valley, California where there is a Black Bart Parade where he is played and portrayed as a stereotypical Old West Villain.

Anyways, Baldr is Jimmy’s Ultimate Persona. Baldr is a Norse god, and was well loved by everyone in the Aesir. He had a prophetic dream where everything is destroyed and gets terrified. His mother then makes everything in existence to personally promise her they won’t hurt him, rendering him near indestructible. But there was one thing that didn’t promise his mother; mistletoe. Loki kills Baldr when the other gods made a game where they throw countless weapons at the newly indestructible Baldr where he throws a spear made of mistletoe at him. He was the metaphorical “canary in the mine” due to his death being the first domino that trigger Ragnarok. Baldr only returns from the dead after Ragnarok throughly destroys everything.

Impulse - “Rook” - The Hierophant Arcana - Wayland/Hephaestus

Impulse owns a small prop weapons company where he forges and creates prop weapons in his own garage. He is coined the “dad” of the group, but would let a stupid scheme play out if he thinks it’s going to be funny. Unknown to anyone but his close friends (Skizz, Gem, and Pearl), but Impulse has a criminal record. He once worked under the one of the biggest mafia families in the country, and he was caught by the police after his teammates from the mafia abandoned him and used him to distract the cops. Ever since then, Impulse has been secretly trying to locate his former teammates to enact revenge on them.

Wayland is Impulse’s persona. Wayland was a blacksmith who was enslaved under a king. He had revenge on the king by killing both his sons and built wings to escape the king. Afterwards, he supplied weapons to several other people in myths and stories such as Charlemagne and his paladin as well as Beowulf as their weapons maker. Impulse is an advocate for burying the hatchet after using the hatchet to brutally destroy those who wronged him.

Impulse’s Ultimate Persona is Hephaestus, the Greek god of the forge and blacksmiths. After being thrown off Mount Olympus, he swore revenge on Hera. He enacted said revenge by trapping her on top of a golden throne that made her unable to get up. Not only in this story, but also in tales such as Aphrodite’s affair, he is noted to be very vengeful and will not yield unless his demands are reached.

Martyn - “Knave” - The Judgement Arcana - Atlantis/Judas

Martyn is a stagehand in the local theatre known for his friendly and amiable demeanour. However, under that cheery demeanour is a burning desire for revenge. Martyn’s parents were devout worshippers of the Watchers and worked under the Pupils. He was subjected to several grievances due to his parents volunteering him for the Pupil’s experiments and abuses. Ever since he’s escaped, he has focused on destroying the cult. He’s been working as a grey hat hacker to clients with varying levels of morality to get money and further his research on the cult.

Martyn is the navigator of the team with his persona Atlantis. Atlantis was a city that was sunk beneath the sea for being too greedy. It was noted to possess technology that surpassed the technology of times and even to this day, it’s still being searched for. The people were of divine descent, and lost their humility as they became more human after each generation.

Martyn’s ultimate persona is Judas. Judas was one of the original disciples for the Big J, and sold out him out for 30 pieces of silver. Martyn’s story in this AU revolves around his grudge against the Pupils and the Watchers, so his persona is someone who betrayed a religious figurehead.

Mumbo - “Vamp” - The Hermit Arcana - Galileo/Thoth

Mumbo is Grian’s roommate and a self proclaimed “spoon”. He is working towards a degree in Computer Science and is often found tinkering with old technology in his room, often to the point him and Grian step on loose screws and pieces of plastic on a weekly basis. Much like Jimmy, he had false memories of Grian implanted in him, which would come into conflict when the origins of Grian is revealed. This was because the main reason he joined the Phantom Thieves was out of concern for Grian. According to him, the day he turned 18 is when his signature moustache just grew spontaneously.

Mumbo’s persona is Galileo, the father of modern science and the scientific method. His studies were considered blasphemous against the church and he was sentenced to house arrest. Even though he was imprisoned, he still had faith in his discoveries and continued his studies within the confines of his house,

His Ultimate Persona is Thoth, the Egyptian God of the moon, wisdom, knowledge, writing, hieroglyphs, and judgement. He’s associated with Hermes and due to the connection, created the epithet Trismegestus. He is someone who solves his issues with diplomacy and reason instead of pure power and strength.

#PERSONA x MCYT AU#Hermitcraft#Hermitcraft au#Grian#martyn inthelittlewood#inthelittlewood#Mumbo jumbo#impulsesv#jimmy solidarity#solidaritygaming#life series#third life#last life#double life#limited life#secret life

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

MEANT TO BE

a Joseph Descamps Fanfiction

DISCLAIMER: I made some small changes to the plot, so as not to make everything too chaotic. I hope you like it!

CHAPTER ONE: Game of Superiority

Chapter 2 — Long time, no see

Summary: It's Ophelia's first day at school. Having just moved to Saint-Jean-d'Angély, in France, she will not only have to face linguistic difficulties and the presence of boys in her new class due to the addition of mixed classes, but she will also meet an old acquaintance of hers. And it won't be that pleasant.

Word Count: 6,146 words.

Warnings: Pichon being bullied, Joseph being Joseph as usual, some bully scenes, slightly angst.

📍Voltaire High, Saint-Jean-D’Angély, France. September 9th, 1963

It was 7:24 in the morning, and Ophelia was already ready to face her first day of school. A mix of excitement and nervousness churned in her stomach, sparked by a tangle of reasons bouncing around in her mind. First of all, she was in France, a land still foreign to her, heading to an unfamiliar building filled with new faces and stories completely unknown to her. That alone would have been enough to make her uneasy, but there was another detail that made her even more hesitant: the school was unlike any she had attended in England. It wouldn’t be all girls; instead, she would be in a mixed class, sharing lessons with both boys and girls.

At fifteen years old, such a situation felt more than unusual—almost revolutionary. Mixed classes? How strange, even slightly uncomfortable concept, she thought. Her mother, Catherine, with her usual reassuring yet firm tone as the teacher she was, had repeated several times that it was time to embrace this modernity.

Nonetheless her father, ever protective, had unsuccessfully tried to enroll her in a private girls' school, but the enrollment at the Voltaire high had already been completed, and neither parent wanted their daughter traveling to another city every morning.

With a sigh, Ophelia looked at herself in the mirror, scrutinizing her reflection as if seeking confirmation that she was truly ready. She had styled her hair into two neat, broad braids—a simple choice that revealed her meticulousness. She had chosen a skirt paired with a modest blouse, aiming to appear polished without drawing too much attention. In England, she had been used to wearing school uniforms—identical for everyone, with their neutral colors and striped blazers and skirts. It was a routine she had always found comforting, a way to avoid thinking about what to wear each day.

In France, however, the system was different. Here, there were no uniforms, and this freedom of choice made her feel slightly uneasy. She feared standing out, feeling too English, too different. Yet at the same time, she was determined to do her best, to face the day as an adventure—a chance to discover who she really was, far from the certainties of home.

Before leaving the house, Ophelia made a quick detour to her brother’s bedroom. Oliver was still sound asleep, curled up under the covers, his face relaxed in that typical childhood slumber. His school wouldn’t start for another week, so for him summer wasn’t over yet. Ophelia leaned down to place a gentle kiss on his forehead, a small tradition that had become second nature between them. She couldn’t help but smile at the sight of her brother, so peaceful and unaware of the turmoil bubbling inside her. Then, with a sigh, she returned to her room to grab the bag she had carefully prepared the night before and headed for the door.

She already knew the way to the school, thanks to Miss Couret—a new face but an unexpectedly pleasant surprise. Shortly after moving to Saint-Jean-d’Angély, Ophelia and her mother had discovered, much to their astonishment, that this woman had been one of Catherine’s old schoolmates. The connection had immediately rekindled, with stories of youth and anecdotes lighting up Catherine’s face with nostalgic smiles.

Miss Couret, who now was a new teacher at Voltaire, had enthusiastically offered to show Ophelia the route to school, accompanying her with a genuine warmth the girl had appreciated. For Catherine, this coincidence was a true blessing. Knowing her daughter would have a familiar face in a completely new environment had been deeply reassuring. She often reminded Ophelia how lucky she was to have a trusted friend like Couret looking out for her at school.

Ophelia, however, wasn’t entirely convinced that this would be enough to put her at ease. Yet, despite her doubts, she forced herself to maintain a steady stride and hold her chin high. This day, for better or worse, would only be the beginning.

She arrived at the gates of Voltaire High School when the clock struck 7:40. The morning air was fresh and crisp, still tinged with the dampness of the night, while the first rays of sunlight brushed against the building’s walls. The gates, just opened, creaked faintly in the wind. Ophelia paused for a moment, her heart pounding, and observed the scene before her. A stream of students poured inside, but there was one detail she couldn’t ignore: everywhere she looked, there were only boys.

Boys, boys, and more boys. It was like finding herself in the middle of a soccer match, with her as the sole outsider. There wasn’t even a hint of another girl—except for herself, of course. The realization of being so out of place stung like a sharp jab, as if every gaze pierced through her. The buzz of conversations almost magically died down as she walked by, leaving behind an oppressive silence that weighed on her shoulders. Everyone stared at her, their eyes filled with curiosity, surprise, or perhaps judgment. To them, she must have seemed like an alien who had landed from another planet.

With a sigh and a surge of determination, she lowered her gaze and pressed on, trying to ignore the sea of eyes fixed on her. But as she moved through the clusters of boys, she noticed someone different—a girl, at last, standing out among all those male faces. She had blonde hair tied into two braids, but not like hers; they were intricately twisted and more stylish. Her outfit gave her a composed air and perhaps a hint of sternness. Ophelia didn’t think twice. She quickened her pace to reach her, trying not to appear too eager, and stopped in front of the bulletin board, pretending to look for her name.

"I can’t tell you how happy I am to see you here!" She said with a smile, putting on her best French accent. The blonde girl turned to her, surprised. Her frown softened, and her face lit up with an equally relieved smile.

"I could say the same thing!" she replied, keeping her smile intact. Just as Ophelia began to feel a small sense of relief, a third figure approached them.

"There are less than twenty of us, right?" The newcomer had a confident air about her and short hair styled so elegantly that Ophelia couldn’t help but envy it. Her mother would never allow her to cut her hair like that, and the idea gave her a pang of frustration.

"I thought I was the only one!" exclaimed the blonde girl, now visibly more at ease.

"I waited for you to go in." the short-haired girl said, stepping forward with her hands clasped behind her back. "My name is Simone."

"Michèle," replied the blonde. Both turned to Ophelia, waiting for her to introduce herself. She hesitated for a moment but then mustered her courage.

"My name is Ophelia." she said, smiling timidly as she tried to pronounce her name clearly.

"Ophelia?" Simone repeated, intrigued. "What a beautiful name!"

"You’re not French, are you?" Michèle asked.

Ophelia shook her head and straightened her posture. "British. I’m here for a year. My dad got… a job offer, so we all moved here."

"Cool!" Michèle exclaimed, her eyes sparkling. She seemed genuinely excited. Perhaps, Ophelia thought, she could find a friend in her. But the thought was quickly followed by a bittersweet smile, a reflection of the homesickness she already felt for her life in England.

"I’m from Algeria." Simone said, breaking the silence.

Ophelia’s face lit up. Another outsider like me, she thought, feeling a sudden kinship. Maybe we could support each other if things got tough.

"Everyone seems to be staring at us…" Simone whispered, glancing furtively around.

"They are." Michèle confirmed with a wry smile.

"Do you think they’ll ever find the courage to talk to us?" Ophelia asked, her eyes scanning the crowd around them.

"Someone’s coming!" Simone announced, suddenly lowering her voice and turning towards the noticeboard. "Act casual."

The three girls exchanged a knowing look and turned in unison as if nothing had happened. Footsteps grew closer until a surprisingly gentle male voice broke the silence.

"Oh no…" the boy muttered, his tone filled with dismay. His words caught the attention of Ophelia and Michèle, who turned to look at him. Standing before them was a boy with kind features, soft eyes, and an almost shy smile. He was nothing like the groups of boys who had been observing the trio from afar, as if analyzing a curious spectacle.

"Is something wrong?" Michèle asked, curious and slightly concerned.

"My homeroom teacher is Bluebeard." he replied, shaking his head with a resigned expression as he looked at the group of girls.

The faint murmur of conversations around them suddenly ceased, as if someone had turned down the volume in the courtyard. Everyone seemed to direct their attention to a single point. Ophelia followed their gazes with a sense of apprehension, turning along with Michèle, Simone, and the boy beside them.

That’s when they saw her: an elegant figure stood out among the crowd, drawing every gaze like a magnet.

She was a blonde girl whose blue dress, simple yet impeccable, enhanced the color of her eyes and the shine of her hair, neatly tied back with a matching headband. Her proud yet reserved demeanor made her seem almost untouchable, as if she had stepped out of an old painting.

"Do you know her?" Michèle whispered to the boy, leaning slightly towards his ear. But he didn’t answer, merely shaking his head. His gaze was fixed on her, completely captivated, just like the rest of the courtyard.

Ophelia watched the scene unfold with a mix of curiosity and admiration. She tried to come up with a compliment in her mind, wrestling with her still-uncertain French. But just as she was about to speak, the bell interrupted her thoughts. The start of lessons forced them all to gather and head toward the school building.

Once gathered just outside the building, the students listened attentively to the solemn words of the Headmaster, Mr. Bellanger. His speech, though formal, carried a reassuring tone—a way to welcome the new students, and especially the girls, into the school community. Then, with efficient organization, the students were divided into their respective classes.

Ophelia felt a mix of relief and joy when she discovered she would be sharing a class with Michèle and Simone. However, her enthusiasm dimmed slightly upon reaching the classroom. All the seats next to her new friends were already taken, forcing her to sit alone at the back of the middle row. I hate sitting in the back, she thought, casting a disheartened glance at the desk before her. Nonetheless, it was the only seat available from which she could clearly see the blackboard.

As she settled in, she noticed a certain buzz of excitement among her classmates. Moments later, the girl in the blue dress entered the room. Her elegant figure once again drew everyone’s attention, but she seemed utterly indifferent to the murmurings. Ophelia followed her with her eyes, observing every movement with growing curiosity.

To her great surprise and relief, the girl walked directly toward the seat next to hers and sat down without a word. I’m not alone, Ophelia thought, mentally repeating those words like a mantra.

“Good morning!” Ophelia greeted her cheerfully, attempting to break the ice in a discreet tone.

The girl, busy neatly arranging her notebooks and books on the desk, did not lift her gaze. Her face remained neutral, devoid of any expression that might suggest an openness to conversation. After a moment of silence, she simply replied, “Hello.”

Her tone was flat and distant, yet Ophelia did not lose hope. She still felt grateful not to be entirely isolated. Every friendship starts somewhere, she told herself, hoping that “hello” could be the first step for something new.

The lesson began, and Ophelia tried hard to focus. Miss Giraud reminded her of her old teacher, Miss Campbell, back at her English school—a thought that brought a wistful smile to her lips. But despite this fleeting resemblance, there was no way to spark a conversation with her desk mate. The girl next to her, completely absorbed in the lesson, seemed as inaccessible as an island surrounded by an invisible barrier.

Ophelia, on the other hand, couldn’t help but feel out of place. Back in England, she had always been one of the best in her French class, but in this room, amidst heavy accents and a rapid pace, she could barely grasp half the words. Every sentence uttered by the teachers seemed to wash over her, leaving her increasingly confused.

The chaotic atmosphere created by the boys in her class didn’t help at all. They seemed constantly distracted, ready to break the silence with silly jokes or pointless remarks. None of them gave the impression of being there to learn. This behavior felt alien, almost absurd, only adding to the sense of inadequacy already weighing on her.

An intense feeling of being watched suddenly distracted her. She felt a strange warmth, as if a persistent gaze were burning her skin. Following that primal instinct, she turned to her left, interrupting her train of thought.

A boy was staring at her. His arms were crossed, and his expression was stern yet veiled with an unspoken curiosity. The glasses resting lightly on his nose framed a tired gaze, but one illuminated by an unusual light, almost investigative. Ophelia felt a chill of discomfort mixed with curiosity. She had the impression she had seen him before but couldn’t recall where.

Maybe at the butcher’s? Or in the bookstore? She wondered, trying to make sense of her muddled memories. Yes, that must be it, she convinced herself, though deep down, she remained uncertain.

The same question lingered in the mind of the boy who responded to the roll call as Joseph Descamps, sitting at the parallel desk not far from hers. His attention never wavered from this new and unexpected figure. There was something about her that unsettled and intrigued him at the same time. It wasn’t just the fact that she was a foreigner, nor her unusual name, Ophelia Montgomery, which sounded completely alien to him.

He scrutinized the girl’s face, her wavy brown hair cascading softly over her shoulders, framing a delicate and almost ethereal visage. He felt as though she had stepped out of a story he knew, and it tormented him. Where have I seen her before? He asked himself repeatedly, unable to find an answer.

Even her name was new to him, of course. A British foreigner, arriving in France for reasons unknown to him, for now. The thought amused him, bringing to mind the vacation he had spent that summer in England. What were the odds that he would now find himself with a classmate from there?

“British,” Jean Dupin, his best friend and inseparable desk mate, murmured, lowering his voice. “They’ve followed you here.”

Joseph let out a muffled laugh, shaking his head slightly. “The charm of a French, what can I say.” he replied with a grin, playing along with his friend.

While the exchanges between the two continued, thoughts of Ophelia continued to haunt him. Despite his efforts to distract himself, every time his eyes wandered, they inevitably returned to her, as if she were the only mystery in that room worth solving.

Ophelia, meanwhile, made a conscious decision: to deliberately ignore the matter of the boy who kept staring at her. She could still feel his intense gaze fixed on her, but she refused to let it distract her. She was determined to make the most of her lessons, striving to follow the content with interest. Over time, she managed to find a certain focus, and, surprisingly, after two and a half hours of study, she was able to grasp almost every word spoken by the teacher.

The voice of the girl sitting next to her, however, distracted her from her thoughts. It was a soft sound that caught her by surprise.

"Are you having trouble with the language?" asked the girl beside her, whose name was Annick Sabiani.

Ophelia hesitated for a moment before nodding. "A little." she admitted honestly, not trying to hide her vulnerability.

Annick, who had been distant until then, turned to look at her. For the first time, a smile appeared on her face.

"I can lend you my notes, if you want." The blonde girl offered with an unexpected kindness.

Ophelia’s face lit up, surprised and relieved by the offer. "You’d save my life, yes." she replied quickly, showing all her gratitude.

That reaction seemed to amuse Annick, who smiled again. Then, with a slightly conspiratorial air, she added: "As long as you can help me with English." Her voice was determined, as if sealing an important deal. Ophelia smiled even more, finding the idea quite amusing.

"Of course, I can." She said, extending her hand toward her in a sign of understanding.

Annick looked at her for a moment, hesitant, but eventually shook her hand. That simple but sincere exchange of gestures and words gave Ophelia new hope. Perhaps, she thought, finding a balance in this new world wouldn’t be so impossible.

In Latin class, the difficulties reappeared relentlessly. Professor Douillard spoke at such a speed that his French, mixed with Latin constructions, became incomprehensible to Ophelia. However, it was in this subject that she felt most comfortable; Latin had always been one of her strengths.

Beside her, Annick Sabiani continued to raise her hand energetically, almost climbing onto the desk in an attempt to get the professor's attention. Yet, Douillard seemed stubbornly intent on ignoring her, indeed, systematically ignoring all the girls in the classroom. No matter how accurate or relevant an answer was, if it came from a girl, it was as if it had never been spoken.

On the board, the phrase read: "Romani ovantes ac graturantes Horatium accipiunt et domum deducunt." Now, the professor waited for someone in the class to volunteer to translate it. A low murmur spread across the room, but no one dared to raise their hand, except for Annick, who didn’t give up on her gesture, determined as ever.

"No one knows it?" The professor urged, with a hint of irritation in his voice.

Finally, a hand was raised halfway across the desks. It was Joseph Descamps.

Ophelia, surprised, turned to look at him again, observing him closely. The profile of the boy struck her like a déjà vu, almost as if his face was hiding something crucial, an enigma yet to be solved.

"Yes, sir." Professor Douillard handed him the floor.

"I think she raised her hand." he said with an ironic smile, while his classmates burst into muffled laughter.

Forced by the situation, Professor Douillard finally turned to Annick, who was still holding up her arm like a banner of resistance. He adjusted the collar of his shirt with an irritated air, then conceded.

"The Romans welcome Horatio with joy and congratulations and escort him to his house." Annick said, standing up with impeccable composure. Ophelia nodded silently, recognizing the correctness of the translation.

Douillard, taken aback, seemed to choke for a moment before correcting her with a synonym: "The Romans cheer Horatio."

Annick didn’t flinch and remained still, ready to face the test. The professor, perhaps annoyed by her confidence, decided to challenge her further.

"Miss, can you conjugate the verb ovare?"

Ophelia, fascinated by her classmate’s determination, found herself silently conjugating the verb alongside her, immersed in the tension of the moment. It was only then that she noticed a movement beside her: Joseph was scribbling something on a piece of paper and discreetly passing it to the boy sitting behind her.

The scene didn’t escape the keen eye of Douillard.

"Give it to me." He ordered, addressing the recipient of the note.

The boy, confused and reluctant, stood up and handed the note to the teacher. A single glance at its content was enough to provoke his indignation. "Do you think this is funny?" he asked in a cutting tone, trying to identify the culprit.

"It’s not mine." the boy stammered, keeping his eyes down.

"Not yours, right? And who is the author of this masterpiece?" Douillard pressed, scanning the faces of the class.

Ophelia turned to Joseph, who was watching the scene with insolent calm, as if it were a movie, completely immune to the rising tension. He was absentmindedly playing with his pen, with no intention of confessing.

"Your name?" the professor continued, fixing his gaze on the curly-haired boy, who was now visibly uncomfortable.

"I didn’t do anything." he answered in a mortified voice.

"I didn’t do anything," Douillard repeated with sarcasm, his tone growing sharper. "Of course, that's what all guilty people say. So, what’s your name?"

"Laubrac," the boy replied after a moment of hesitation. "My name is Laubrac."

A sudden look of understanding crossed the professor’s face. "You are the boy from foster care?" he asked, pointing at him with contempt.

The class erupted in a series of malicious giggles. Douillard sneered.

"An orphan who wants to graduate? How amusing." Laubrac visibly fidgeted, hurt by the public humiliation. He began nervously twisting the cuffs of his shirt.

"Didn’t anyone teach you discipline in the care system?" the professor continued, striking with a chilling cruelty. "I don’t want bastards in my class, so get out of here."

A tense silence fell over the room, suddenly broken by a female voice: "But he didn’t do anything!"

Ophelia spun around quickly to see Michèle standing up, fists clenched, and cheeks flushed with indignation. The girl’s courage struck Ophelia deeply. No one, she thought, would have dared to intervene in her place.

"Weren’t you taught to raise your hand in the girls' school, Miss Magnan?" Douillard retorted, his voice venomous. "Do you think you have a pass just because you’re the dean's niece?"

Michèle lowered her gaze, visibly embarrassed, as the murmurs from the students turned into suppressed laughter.

"Well, go accompany your new friend to your uncle," Douillard concluded with a dismissive tone. "You’ll stay an hour too."

With hesitant steps, Michèle followed Laubrac out of the room, leaving behind a trail of looks and comments. Ophelia, in silence, reflected on how enlightening that scene had been: not all her classmates were passive spectators, and Michèle’s courage inspired a deep respect in her.

Ophelia turned one last time toward Descamps, looking at him with a mixture of disapproval and disbelief. He was laughing with his friends, as if the scene that had just unfolded was a performance put on for his personal amusement. She pressed her lips into a thin line, shaking her head slightly. It was clear that this boy embodied everything she found unbearable: arrogance, superficiality, and that blatant indifference to the world around him. She mentally noted the names of the classmates to avoid, and Joseph Descamps had rightfully earned the top spot on the list.

This thought resurfaced with force later, during the lunch break, when he dared to approach her in the cafeteria. It was clear he was trying to get her attention with his usual arrogant attitude. He almost seemed to want to escort her, following her with a certain ostentation as she walked toward the girls' table.

Ophelia, completely indifferent to his presence, kept her pace steady, the sound of her heels rhythmically echoing on the floor. She held her books tightly against her chest, as if they were a shield against the world around her. Every movement radiated composure and determination, a clear message that she had no intention of being bothered by him. His smug smile, that relaxed and almost theatrical way of accompanying her to the table, made her feel like she was part of a game he had already decided to win. She found him unbearable, a perfect example of the superficiality she despised with every fiber of her being.

"You're British, right?" he asked, deliberately emphasizing his French accent. There was a hint of irony in his tone, a clear attempt to make her uncomfortable or get her to talk. His face wore that familiar smug grin, a twist of the lips that seemed to say I know something you don't. But he was just pretending.

Ophelia kept her gaze fixed ahead, her steps steady and rhythmic, echoing in the controlled silence of the cafeteria. She pressed her books against her chest, almost as though they were a shield. She had no intention of engaging in a frivolous exchange with him.

"Yes." She replied, curt and definitive. She didn't say more; the word was there, suspended like a door shut firmly.

Joseph slowed his pace, now walking beside her with an irritating nonchalance.

"London, I suppose? Or am I wrong?" He guessed, pretending to recognize it from her accent, not mentioning that it had been the only city he visited that summer.

The girl turned slightly, giving him an irritated look. Then, she went back to looking straight ahead.

"You're not wrong." Her voice was calm, but there was a sharp edge to the words, like a thin blade.

Joseph tilted his head, the smile more pronounced, as if he were enjoying every moment of the conversation.

"Interesting. I was in London this summer. A cultural trip, let's say. I was trying to perfect my English. What do you think?" he asked, changing tone and exaggeratedly flaunting his pronunciation.

Ophelia couldn't help but chuckle, though imperceptibly. Her expression, however, remained composed.

"I think London wasn't as lucky to have you there." The response, subtle and well-aimed, hit the mark.

Joseph raised an eyebrow, clearly amused. "Touché. But I believe the city will suffer from my absence. I'm pretty sure your fellow countrymen found me... fascinating."

Ophelia suddenly stopped, turning to look at him with an expression that oscillated between surprise and disbelief.

"Fascinating? Really?" she asked, unable to tell if he was being ironic or not.

"You know, I find it strange that London didn’t feel the need to erect a statue in your honor. It must have been an oversight."

He laughed, the sound low and relaxed. "Well, maybe there's still time. You can suggest it next time you're home."

"I’ll do my best." She retorted, resuming her walk and tightening her grip on the books with a bit more energy. The tension between them was palpable, but beneath the facade of barbs and arrogant smiles, there was something undefined that seemed to suggest this wasn't the first time their paths had crossed.

When they reached the table, Joseph stopped, theatrically gesturing for her to go first.

"After you, Miss England." Ophelia shot him a sharp look and ignored him. She then sat down without another word, determined to ignore him for the rest of lunch. But something inside her told her that Joseph Descamps would not disappear so easily from her life.

And indeed, while she listened attentively to Simone’s stories about Algeria, Ophelia heard a small thud. She diverted her gaze from her interlocutor and noticed, with displeasure, Henry Pichon's hand— the boy with kind eyes who had introduced himself with a shy smile at the entrance of the school—completely submerged in Annick's plate. The embarrassment on the boy's face was immediately amplified by the loud laughter of Joseph Descamps and his group of friends, whose raucous voices echoed through the cafeteria, drawing the attention of other students into an irreverent chorus.

Descamps had pushed him, on purpose.

"Sorry, Annick..." Henry stammered, the redness invading his cheeks seemed ready to devour him. He lowered his head, avoiding the mocking gazes surrounding him. "Do you want my plate?" he asked, his tone mortified, revealing how much he wished he could disappear at that moment.

"That idiot should be the one to give it to her." Michèle's sharp comment broke the echo of laughter, plunging the room into a heavy silence. All eyes turned to her, who seemed unfazed by the attention. She nodded toward Descamps, her eyes blazing with indignation.

Joseph, on the other hand, received the provocation with a cold smile. His dark, calculating eyes scanned her from head to toe, as if evaluating his next move. Then, with the composure of someone accustomed to dominating the situation, he straightened up in his chair, allowing an expression of irritating superiority to settle on his face.

"Does the dean's niece have a problem?" he asked with a sneering tone, his voice dripping with an almost theatrical arrogance. The general attention remained focused on him, as though he were the undisputed star of the scene.

"What did you say to your uncle?" he insisted, pretending to be curious. Then, with an obviously intentional exaggeration, he modulated his voice into a high-pitched falsetto to mog her.

"Laubrac is innocent, Descamps is the bad one!" The irony of his words triggered another round of laughter, but the final blow came with his next line: "The niece and the bastard, a new love story."

Ophelia watched the scene with disgust. The dynamics of social power were all too clear: Joseph Descamps held authority based on toxic charisma and the humiliation of others, and the crowd around him happily followed him like a flock of sheep.

Michèle, however, wasn’t intimidated. She raised her head with determination, her gaze fixed on Joseph, a clear sign of defiance.

"Why don't you tell us what you wrote on that note?" she asked, her tone dripping with bravado.

Joseph, with the nonchalance of someone who enjoys teasing others, shrugged. "Nothing," he replied, feigning innocence. "It was a drawing. Let me show you."

With theatrical flair, he grabbed some sauce and poured it over his mashed potatoes, drawing a stylized image of a busty breast. He raised the plate with a pleased look, showing his "masterpiece" to the other onlookers.

"It’s a portrait." he announced, with a triumphant grin that widened as the crowd burst into self-satisfied laughter.

Ophelia was overwhelmed by a wave of nausea. There’s a limit to everything, she thought, rolling her eyes with a gesture as natural as it was eloquent. Her expression of disgust didn’t escape Joseph, who noticed it and intensified his smile. The silent challenge exchanged between them lasted an instant but felt eternal.

"Does this remind you of anyone?" Simone, sitting next to Michèle, couldn’t hold back any longer. With unexpected speed, she grabbed a sausage from her plate, raised it with theatrical flair, and snapped it in half with a force that left everyone speechless. Her eyes, locked on Joseph, seemed to promise she’d do the same to him.

The cafeteria froze, enveloped in an eerie silence. For the first time, Joseph didn’t respond.

Ophelia watched with a mix of admiration and disbelief. Maybe not everyone here is a sheep, she reflected, allowing a small smile to slip onto her lips.

Meanwhile, Joseph, with an unreadable expression on his face, shifted his gaze back to Michèle. This time, however, there was something different in his eyes: pure calculation. He was already scheming against her.

And sure enough, he made plans with his friends for revenge against Bellanger’s niece the following day.

On the first day of school, the students were allowed to leave after lunch, an unusual concession from the headmaster, who watched with satisfaction from the window of his office as the students slowly streamed out. The excitement over that small freedom was palpable, and Ophelia blended into the crowd, until she spotted an unexpected scene.

Waiting for her by the family car were her mother and little brother Oliver. The surprise filled her heart with joy, and with a radiant smile, she hurried toward them. Oliver, like a rocket, ran toward his sister, arms wide and a crystal-clear laugh filling her ears.

"Sis!" he exclaimed, hugging her with all the strength of his nine years. Ophelia bent down without hesitation, ignoring the scrapes on her knees from the gravel in the courtyard.

"Olly!" she exclaimed sweetly, stroking his chubby face. "What are you doing here? Weren’t you supposed to be at home with Mom?"

Oliver laughed, as though guarding a little secret. "We came to pick you up from school, can’t you see?" he replied with a serious tone that made her laugh out loud.

However, the magic of the moment was shattered by a voice behind her, a voice she never expected to hear so soon.

"I can’t believe it." Those words, spoken with a tone straddling amusement and disbelief, sank into her ears like an annoying buzz. Ophelia turned, her heart skipping a beat.

Joseph Descamps was there, now standing in front of her, with that cocky grin that seemed like a trademark. His eyes betrayed a flash of amusement, and perhaps something deeper.

"So it was you…" he murmured, staring at her with intensity. Then his gaze moved to Oliver, who was looking at the newcomer with confused curiosity.

"Hey, kid," Joseph bent down toward the little one, ruffling his hair. "How’s the bump?"

Ophelia froze. It took her a few seconds to piece the puzzle together, but when she did, reality hit her like a lightning bolt. It was him. The boy from the park. The one who had hurt her brother and mocked him for no reason.

"You." She said with a cold voice, her gaze turning into an icy blade.

"Well, good morning! Welcome back among us!" Joseph replied, theatrically, with exaggerated surprise. He seemed to fully enjoy the effect he was having on her, like a cat toying with a mouse.

"The world is so small, huh?" he added, tilting his head slightly, the grin widening.

Meanwhile, Oliver was watching the scene with a questioning expression. He didn’t understand a word of the French they were exchanging, but Joseph’s attitude was enough to make him realize he wasn’t exactly a friend. And he remembered him, oh yes, of course he did.

"I can’t believe it." Ophelia muttered, taking a step back. Her protective instinct kicked in immediately, and she pulled Oliver close, wrapping a hand around his arm.

Joseph didn’t flinch. In fact, he seemed to enjoy it even more.

"How’s it going, champ? Still playing soccer with the big kids?" he asked, feigning friendliness.

"Enough." Ophelia cut him off, her voice firm, solemn, almost imperious. Her patience had run out. She wasn’t going to let that guy keep playing with them as if they were pawns in a cruel game.

Joseph theatrically recoiled, pretending to be taken aback.

"What a temper!" he exclaimed, laughing under his breath and casually fixing his hair. "You know, I was just trying to be friendly. After all, you’re my new classmate, and I’m always so friendly with my lovely classmates, i just can't help it."

Ophelia didn’t even bother to respond. She knew perfectly well that every word would be bait for more provocations. He had made it clear many times that day that he wasn’t at all what he had just claimed, and she wasn’t going to discuss it right then, especially not in front of her brother.

"He doesn’t speak French." she replied coldly.

Joseph tilted his head, half-interested. "Oh, I see. What a shame." But then he lowered himself again to Oliver’s height and, with a surprisingly genuine smile, said to him in broken English, "You’re in great shape, kid."

Oliver, though skeptical, gave a small smile, not really knowing how to interpret the comment. Joseph stood up again, ruffling his hair once more.

"See you tomorrow, Miss England," he said, adjusting his jacket. His grin back on his lips.

"See you, Champion." He waved to Oliver before turning and walking out of the schoolyard, which was now almost completely empty.

Ophelia stood there, watching him walk away, a whirlwind of emotions battling in her chest: anger, confusion, but also a strange curiosity she couldn’t suppress. Joseph Descamps was irritating, arrogant, and cruel, but there was something about him, something she couldn’t yet decipher. And that bothered her more than any insult.

Author's Nothes:

I'm so happy about how this chapter turned on.

I postponed the incident to the next day of school because i think it would have been so full of events otherwise. I hope you don't mind!

What do you think about the relationship between Joseph and Ophelia so far? we have just laid the foundations, you will be so surprised by the next chapters.

I love them ngl.

Thank you for reading this, leave a comment, a like or repost if you'd like! Thank you, thank you, thank you.

vondarte ©

#joseph descamps#joseph descamps x reader#joseph descamps fanfiction#mixte1963#mixte 1963#enemies to lovers#slow burn#fanfiction#fanfic#london#france#angst#friendship#vondarte stories

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, here are some random panels I’m personally looking forward to at the online Les mis convention Barricadescon starting tomorrow!! (note that this off the top of my head, and they’re in no particular order, and that I am excited for all of em.)

(Also note that it’s the last day to register, which you can do on their site here. You can also see the full program of all the panels/their descriptions here.)

1. I’ll say any of the Guests of Honor (Jean Baptiste Hugo, the descendant of Hugo will be talking about his project photographing his ancestor’s house; Christina Soontornvat, author of the award-winning Les Mis retelling “A Wish in the Dark;” and Luciano Muriel, playwright of a 2018 play about Grantaire.)

2. @psalm22-6 ‘s panel “Early Transformative Works,” which is about the earliest Les Mis retellings, parodies, and “fanfics” from the 1800s/early 20th century. They’ve shared deeply cursed sneak peeks with me. Apparently in 1863 a man wrote a “proper Christian” retelling of Les Mis where Javert is reimagined as a proper Christian woman following poor criminals around giving them charity while they keep rejecting her kindness. Powerful. Javert as Mary Sue. (Note that I may be explaining poorly because I haven’t seen the panel yet.

3. History podcaster David Montgomery’s panel “The Yellow Passport: Surveillance and Control in 19th Century France,” which dives into the role of the police and strategies of government surveillance at the time Les Mis is set!

4. My own panel “Why Is There a Roller Coaster in Les Mis,” which I shared the first five minutes of here. There’s an actual scene in Les Mis where Fantine rides a roller coaster so I made a full defunctland video on how that roller coaster got to Paris in 1817, the fascinating historical context behind early roller coasters, and why it became defunct.

5. @thecandlesticksfromlesmis ‘s panel “Beat for Beat,” analyzing the script of Les Mis 2012 and contrasting it with the book and musical. Discussion of 2012 is almost overwhelmingly always about its music or cinematography, and I’m fascinated to hear someone finally analyzing the screenplay/ structural changes.

6. Morbidly curious for “Lee’s Miserables,” the academic panel discussing the paradoxical popularity of a censored version Les Mis in the Confederate South (with all the references to the evils of slavery carefully removed of course)

7. “Barricades as a Tactic,” a panel discussing how barricades actually functioned as a tool of warfare historically and the echoes of them in the modern day.

8. All the little social meetups, including the Preliminary Gaieties drinking game!

9. I’m biased because I’m also helping present this one, but the @lesmisletters panel (on the Dracula-daily inspired Les Mis readalong happening now.)

10. “The Fallibility of History in Les Miserables,” by @syrupsyche. It’s a panel analyzing the way Hugo often treats Les mis as a story that he learned about through research/gossip, rather than a fictional narrative— analyzing where Hugo does that in the text and what it means thematically.

11. The Unknown Light Examined, by Madeleine— a panel analyzing the chapter where the Bishop confronts the elderly revolutionary, and is forced to re examine his political beliefs! An iconic chapter, and the abstract is very compelling.

But also a lot more, check out the exhaustive list here XD. And also register at this link!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

tag people you want to get to know better

was tagged by @aztarion teeheehee thankies jez mwah💖💖💖

tagging: mmmh. @kazooyah @kazamajun @shiroboom @solidsnakecake @gothpirates @zenyamin @purgetrooperfox @ntaras but no rush or pressure tho it's just for fun

last song: Devil's Child - Judas Priest

currently watching: I finally picked up revolutionary girl utena up again 🥹 (im so sorry it took so long drake)

three ships: kazjun, subscorp and uuuuuuh jarthur (not even really a ship let alone romantic, its more like. an experience now)

favorite color: lmao

currently consuming: sour cream and onion pringles

first ship: PROBABLY vegebul back in middle school

place of birth: brittany

current location: south france✌️

relationship status: I dont really care

last movie: Slay The Princess which is totally a movie and not a game I cannot play right now

currently working on: like four different aus I need to put into words now. playing laughing having fun👍 also getting the crystal heart in my new hollow knight save

#usually i have trouble doing tag memes but this one didnt seemed so hard#so thanks again!#tagging later

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

“How much evil we must do in order to do good,” the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr wrote in 1946. “This, I think, is a very succinct statement of the human situation.” Niebuhr was writing after one global war had forced the victors to do great evil to prevent the incalculably greater evil of a world ruled by its most aggressive regimes. He was witnessing the onset of another global conflict in which the United States would periodically transgress its own values in order to defend them. But the fundamental question Niebuhr raised—how liberal states can reconcile worthy ends with the unsavory means needed to attain them—is timeless. It is among the most vexing dilemmas facing the United States today.

U.S. President Joe Biden took office pledging to wage a fateful contest between democracy and autocracy. After Russia invaded Ukraine, he summoned like-minded nations to a struggle “between liberty and repression, between a rules-based order and one governed by brute force.” Biden’s team has indeed made big moves in its contest with China and Russia, strengthening solidarity among advanced democracies that want to protect freedom by keeping powerful tyrannies in check. But even before the war between Hamas and Israel presented its own thicket of problems, an administration that has emphasized the ideological nature of great-power rivalry was finding itself ensnared by a morally ambiguous world.

In Asia, Biden has bent over backward to woo a backsliding India, a communist Vietnam, and other not so liberal states. In Europe, wartime exigencies have muted concerns about creeping authoritarianism on NATO’s eastern and southern fronts. In the Middle East, Biden has concluded that Arab dictators are not pariahs but vital partners. Defending a threatened order involves reviving the free-world community. It also, apparently, entails buttressing an arc of imperfect democracies and outright autocracies across much of the globe.

Biden’s conflicted strategy reflects the realities of contemporary coalition building: when it comes to countering China and Russia, democratic alliances go only so far. Biden’s approach also reflects a deeper, more enduring tension. American interests are inextricably tied to American values: the United States typically enters into great-power competition because it fears mighty autocracies will otherwise make the world unsafe for democracy. But an age of conflict invariably becomes, to some degree, an age of amorality because the only way to protect a world fit for freedom is to court impure partners and engage in impure acts.

Expect more of this. If the stakes of today’s rivalries are as high as Biden claims, Washington will engage in some breathtakingly cynical behavior to keep its foes contained. Yet an ethos of pure expediency is fraught with dangers, from domestic disillusion to the loss of the moral asymmetry that has long amplified U.S. influence in global affairs. Strategy, for a liberal superpower, is the art of balancing power without subverting democratic purpose. The United States is about to rediscover just how hard that can be.

A DIRTY GAME

Biden has consistently been right about one thing: clashes between great powers are clashes of ideas and interests alike. In the seventeenth century, the Thirty Years’ War was fueled by doctrinal differences no less than by the struggle for European primacy. In the late eighteenth century, the politics of revolutionary France upheaved the geopolitics of the entire continent. World War II was a collision of rival political traditions—democracy and totalitarianism—as well as rival alliances. “This was no accidental war,” German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop declared in 1940, “but a question of the determination of one system to destroy the other.” When great powers fight, they do so not just over land and glory. They fight over which ideas, which values, will chart humanity’s course.

In this sense, U.S. competition with China and Russia is the latest round in a long struggle over whether the world will be shaped by liberal democracies or their autocratic enemies. In World War I, World War II, and the Cold War, autocracies in Eurasia sought global primacy by achieving preeminence within that central landmass. Three times, the United States intervened, not just to ensure its security but also to preserve a balance of power that permitted the survival and expansion of liberalism—to “make the world safe for democracy,” in U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s words. President Franklin Roosevelt made a similar point in 1939, saying, “There comes a time in the affairs of men when they must prepare to defend, not their homes alone, but the tenets of faith and humanity on which their churches, their governments, and their very civilization are founded.” Yet as Roosevelt understood, balancing power is a dirty game.

Western democracies prevailed in World War II only by helping an awful tyrant, Joseph Stalin, crush an even more awful foe, Adolf Hitler. They used tactics, such as fire-bombing and atomic-bombing enemy cities, that would have been abhorrent in less desperate times. The United States then waged the Cold War out of conviction, as President Harry Truman declared, that it was a conflict “between alternative ways of life”; the closest U.S. allies were fellow democracies that made up the Western world. Yet holding the line in a high-stakes struggle also involved some deeply questionable, even undemocratic, acts.

In a Third World convulsed by instability, the United States employed right-wing tyrants as proxies; it suppressed communist influence through coups, covert and overt interventions, and counterinsurgencies with staggering death tolls. To deter aggression along a global perimeter, the Pentagon relied on the threat of using nuclear weapons so destructive that their actual employment could serve no constructive end. To close the ring around the Soviet Union, Washington eventually partnered with another homicidal communist, the Chinese leader Mao Zedong. And to ease the politics of containment, U.S. officials sometimes exaggerated the Soviet threat or simply deceived the American people about policies carried out in their name.

Strategy involves setting priorities, and U.S. officials believed that lesser evils were needed to avoid greater ones, such as communism running riot in vital regions or democracies failing to find their strength and purpose before it was too late. The eventual payoff from the U.S. victory in the Cold War—a world safer from autocratic predation, and safer for human freedom, than ever before—suggests that they were, on balance, correct. Along the way, the fact that Washington was pursuing such a worthy objective, against such an unworthy opponent, provided a certain comfort with the conflict’s ethical ambiguities. As NSC-68, the influential strategy document Truman approved in 1950, put it (quoting Alexander Hamilton), “The means to be employed must be proportioned to the extent of the mischief.” When the West was facing a totalitarian enemy determined to remake humanity in its image, some pretty ugly means could, apparently, be justified.

That comfort wasn’t infinite, however, and the Cold War saw fierce fights over whether the United States was getting its priorities right. In the 1950s, hawks took Washington to task for not doing enough to roll back communism in Eastern Europe, with the Republican Party platform of 1952 deriding containment as “negative, futile, and immoral.” In the 1960s and 1970s, an avalanche of amorality—a bloody and misbegotten war in Vietnam, support for a coterie of nasty dictators, revelations of CIA assassination plots—convinced many liberal critics that the United States was betraying the values it claimed to defend. Meanwhile, the pursuit of détente with the Soviet Union, a strategy that deemphasized ideological confrontation in search of diplomatic stability, led some conservatives to allege that Washington was abandoning the moral high ground. Throughout the 1970s and after, these debates whipsawed U.S. policy. Even in this most Manichean of contests, relating strategy to morality was a continual challenge.

In fact, Cold War misdeeds gave rise to a complex of legal and administrative constraints—from prohibitions on political assassination to requirements to notify congressional committees about covert action—that mostly remain in place today. Since the Cold War, these restrictions have been complemented by curbs on aid to coup makers who topple elected governments and to military units that engage in gross violations of human rights. Americans clearly regretted some measures they had used to win the Cold War. The question is whether they can do without them as global rivalry heats up again.

IDEAS MATTER

Threats from autocratic enemies heighten ideological impulses in U.S. policy by underscoring the clash of ideas that often drives global tensions. Since taking office, Biden has defined the threat from U.S. rivals, particularly China, in starkly ideological terms.

The world has reached an “inflection point,” Biden has repeatedly declared. In March 2021, he suggested that future historians would be studying “the issue of who succeeded: autocracy or democracy.” At root, Biden has argued, U.S.-Chinese competition is a test of which model can better meet the demands of the modern era. And if China becomes the world’s preeminent power, U.S. officials fear, it will entrench autocracy in friendly countries while coercing democratic governments in hostile ones. Just witness how Beijing has used economic leverage to punish criticism of its policies by democratic societies from Australia to Norway. In making the system safe for illiberalism, a dominant China would make it unsafe for liberalism in places near and far.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reinforced Biden’s thesis. It offered a case study in autocratic aggression and atrocity and a warning that a world led by illiberal states would be lethally violent, not least for vulnerable democracies nearby. Coming weeks after Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin had sealed a “no limits” strategic partnership, the Ukraine invasion also raised the specter of a coordinated autocratic assault on the liberal international order. Ukraine, Biden explained, was the central front in a “larger fight for . . . essential democratic principles.” So the United States would rally the free world against “democracy’s mortal foes.”

The shock of the Ukraine war, combined with the steadying hand of U.S. leadership, produced an expanded transatlantic union of democracies. Sweden and Finland sought membership in NATO; the West supported Ukraine and inflicted heavy costs on Russia. The Biden administration also sought to confine China by weaving a web of democratic ties around the country. It has upgraded bilateral alliances with the likes of Japan and Australia. It has improved the Quad (the security and diplomatic dialogue with Australia, India, and Japan) and established AUKUS (a military partnership with Australia and the United Kingdom). And it has repurposed existing multilateral bodies, such as the G-7, to meet the peril from Beijing. There are even whispers of a “three plus one” coalition—Australia, Japan, the United States, plus Taiwan—that would cooperate to defend that frontline democracy from Chinese assault.

These ties transcend regional boundaries. Ukraine is getting aid from Asian democracies, such as South Korea, that understand that their security will suffer if the liberal order is fractured. Democracies from multiple continents have come together to confront China’s economic coercion, counter its military buildup, and constrict its access to high-end semiconductors. The principal problem for the United States is a loose alliance of revisionist powers pushing outward from the core of Eurasia. Biden’s answer is a cohering global coalition of democracies, pushing back from around the margins.

Today, those advanced democracies are more unified than at any time in decades. In this respect, Biden has aligned the essential goal of U.S. strategy, defending an imperiled liberal order, with the methods and partners used to pursue it. Yet across Eurasia’s three key regions, the messier realities of rivalry are raising Niebuhr’s question anew.

CONTROVERSIAL FRIENDS

Consider the situation in Europe. NATO is mostly an alliance of democracies. But holding that pact together during the Ukraine war has required Biden to downplay the illiberal tendencies of a Polish government that—until its electoral defeat in October—was systematically eroding checks and balances. Securing its northern flank, by welcoming Finland and Sweden, has involved diplomatic horse-trading with Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who, in addition to frequently undercutting U.S. interests, has been steering his country toward autocratic rule.