#Popasna

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

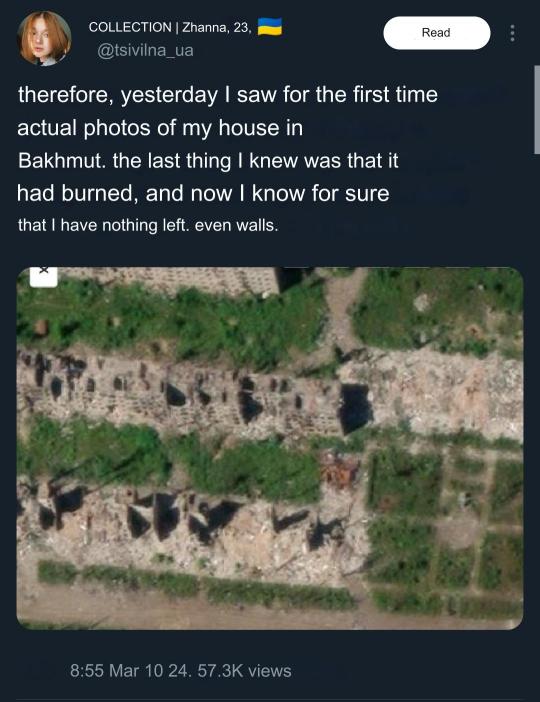

Don't forget about Ukraine

The world, don't forget that in Ukraine it's even more cities like Mariupol have been mercilessly wiped off by Russia. Extremely horrific war crimes keep registering. Death toll can't be calculated now. We urgently need your support. Please keep spreading our voices and donate to our army and combat medics (savelife.in.ua, prytulafoundation.org, Serhii Sternenko, hospitallers.life, ptahy.vidchui.org and u24.gov.ua).

#Bahmut#Avdiivka#Volnovaha#Mariinka#Lyman#Severodonetsk#Rubizhne#Popasna#Izium#ukraine#Mariupol#stand with ukraine#arm ukraine#russia#russia is a terrorist state#oscar#oscars#20 days in mariupol

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

My next post in support of Ukraine is:

Next site, is the city of Popasna in Luhansk Oblast. I'm focusing on a once living, thriving Ukrainian city that is sadly and utterly destroyed, like so many Ukrainian cities now. It had an estimated population of 20,600 people in 2018, before the full-scale invasion. It has been occupied by muscovy since May 2022. It was founded in 1870 as a stop on a new railway. It was occupied by the Nazis during WWII, who had a prison set up in the city. In May 2022, Ukrainian forces had to withdraw from the city to better fortified areas, and it was claimed that "everything was destroyed there." It's reported that due to the extent of the destruction of the city that the occupation "authorities" have abolished its status as a separate city and have incorporated it into the administration of another nearby occupied city, Pervomaisk. The reason I chose a completely destroyed city for this evening's post is because I feel that this level of destruction could, and should, have been avoided completely. Several countries just helped Israel by shooting down the exact same kind of drones that have been targeting Ukraine for two years. That Ukraine's so-called partners could have been doing that for Ukraine but chose not to out of some fear of escalation is absolutely despicable. Thousands upon thousands of Ukrainians have been killed. Millions have been uprooted. Ukraine's so-called partners should be deeply ashamed that they have allowed this genocide to be perpetrated against Ukraine. Especially my own country & government. I'm not going to get into the current hold-up on aid, though. For this post, I'm more concerned with the fact that Ukraine's so-called partners could have prevented so much death and destruction if Ukraine had just been given what they asked for in the first place and also closed Ukraine's skies. Ukraine is losing it best and brightest people, and that is because Ukraine's so-called partners are allowing it. Some of Ukraine's partners are amazing, though. Some of Ukraine's partners are doing all they can. And I appreciate those countries more than I can say. But my own country, the US, has truly let Ukraine down.

#CloseUkrainesSkiesNow

#СлаваУкраїні 🇺🇦

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

In theory, taking entire bakhmut back and then pushing toward popasna puts very big pressure on Russia.

Pinch off northern luhansk and that’d cut off almost the main reason why russian took eastern Donbas for the north south rails.

The land bridge will be cut off by year end not because I’m optimistic for ukraine but because russia is ready to just let their forces there fight till they all die because the timing is futile and will coincide with the additional fighter jets for ukraine.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The day after the plane crash that apparently killed both Yevgeny Prigozhin and his right-hand man Dmitry Utkin (who gave his nom-de-guerre “Wagner” to the entire Wagner Group), local residents and leaderless mercenaries gathered by the former PMC Wagner Center in St. Petersburg. The flowers, candles, and other offerings they brought heaped up into a sprawling memorial to a man who had gained immense notoriety, both in Russia and abroad, for his private military company’s role in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Ekaterina Barkalova, a reporter writing for the independent Russian outlet Bumaga, visited the memorial and spoke to the people who came to honor Prigozhin. With the publication’s permission, Meduza is publishing an abridged translation of her reportage on why many Russians admired Prigozhin, despite his criminal biography and Wagner Group’s reputation for grotesque violence and colossal losses of mercenaries’ lives.

A burial mound in the midst of St. Petersburg

At noon, the time when mourners were asked to gather at the former PMC Wagner Center, around 50 people stand in front of the office building. A mound of loose soil left behind by city landscapers must have reminded someone of a burial site: within a short time, it’s covered with red carnations and begins to really look like a fresh grave.

Mothers with children, teens, and men in military uniforms marked with “Z” patches all show up carrying flowers and Wagner banners. Crossing themselves before the memorial, they step away to make room for others. “Teaching the kids respect,” says a woman holding a pair of red-headed twin boys by the hands.

A uniformed man in a balaclava has fallen to his knees before the mound. His whole body shakes as he bursts into tears. He turns out to be a currently enlisted mercenary. Another Wagner fighter says he is going to stay on with the private military company. “We’re a brotherhood,” he says, and “you can’t trade your family for another.” “We’re all of the same blood. We’re bound by the blood we shed in Bakhmut, Slovyansk, and Popasna. Life is hard here,” he says, gesturing at the civilian life around him, “but easy at the front.”

Over there, you know who’s who, both your enemies and your friends. Here, you can’t sort it out. It’s like a disease. People who try to quit manage for a couple of weeks. But there’s that pull to go back.

A police car passes by the memorial a few times. The operatives inside are watching the mourners, but the car doesn’t stop. A group of people, likely associated with Wagner Group, are attending the memorial, keeping order.

In the afternoon, a courier arrives with an enormous wreath. He adds it to the growing mound of offerings without telling anyone who had paid for it. Shortly afterwards, a young man named Dmitry brings a sledgehammer to the memorial site. This reminds the crowd of the brutal executions practiced by Wagner mercenaries.

“Prigozhin liked sledgehammers,” Dmitry says, explaining that he got this particular tool from his friends, some of them former Wagner mercenaries.

“He didn’t like sledgehammers,” objects a woman from the crowd. “It was just a symbol,” she says.

Dmitry bows to the public. A state television crew asks him to lay the sledgehammer again, for a TV segment. He lays it on the flowers again. And again.

A man and his son are arranging votive candles into cross shapes. “When it gets dark, the cross will be visible from up there,” the man says, heaving a sigh as he gestures towards the heavens.

When the memorial is already heaped high with flowers, flags, chevrons, and the sledgehammer, a young woman comes with a drawing and adds it to the mound. It’s a drawing of a cute capybara with Wagner insignia. Next to the capybara, a handwritten message is scrawled: “We’ll always remember you. Should we still believe in a better future, Pops?” The artist dries her eyes with a tissue. One of her friends, she says, also served in Wagner Group.

The former PMC Wagner building’s new occupants are watching the crowd from a distance. They work for Megastroy, a company that moved into the former PMC Wagner Center after Prigozhin’s mutiny fizzled out on June 24. “We’ve read the news,” one of them says. “We think it’s a staged death. Prigozhin must be in Hawaii now, drinking cocktails.”

The night before, the building’s 13th floor was lit, the lights forming the shape of a cross. Employees working in the building now don’t think it was intentional.

Who mourns Prigozhin and why

Many of those who came to say farewell to Prigozhin have a personal connection to Wagner Group. Some writers who worked for his “troll farm” from last November to June joined the crowd briefly but declined to talk to journalists. Some visitors sympathize with the PMC because they know someone who serves there or died as a Wagner mercenary.

At a distance, a group of men in military camouflage look like current Wagner fighters.

A pair of teenage boys

We came to honor the memory of a great Russian man and patriot who fought for our Fatherland. We’d like to join the PMC ourselves, but we’re not 18 yet.

A Wagner fighter

I took the news really hard. The commander’s death — I don’t know if he’s really dead, they haven’t confirmed that yet, have they? We’re waiting to hear this isn’t true. We absolutely don’t want this to be true. It’s a heartache, it’s like your next-of-kin. What are we gonna without him?

The mercenary says he met Prigozhin in person: he used to visit the troops. The speaker joined the PMC long before 2022. He has a hard time believing that Prigozhin and Utkin could be dead. “They always had some moves in reserve,” he says. Besides, the paramilitary group wouldn’t let something like this just slide. Though partly under the Defense Ministry’s control, it’s a force unto itself in Africa, he argues. “Those who did it will be caught and punished very harshly.”

“Do you realize who those pilots were?” he says about the crew of Prigozhin’s executive jet. “They were the best pilots in the world — pilots who could fly without a plane!”

Prigozhin had plenty of enemies, because he always told the truth. He said everything just how it was, without embellishment or hypocrisy. Not how they do it today on TV and everywhere else — it’s all liars the world over. He was our fighting spirit. He had our back.

He doesn’t believe that Ukraine could have been interested in the crash. “There’s plenty of villains here too,” he says about Russia, “people who will do anything for $100 — sell whatever, break whatever, damage the infrastructure.” Wagnerites, on the other hand, “had ironclad discipline” and “never had any problems with civilians,” he is certain.

An entrepreneur who arranged candles into cross shapes

How could you not worship a hero? There are very few of them left in our country. Since the day he founded Wagner Group, he was a man of his word. He said he’d capture Bakhmut no matter the cost, and he did it. God only knows what he had to do when no one gave him [the ammunition] he needed, but he did everything he said he would.

“It’s a pity to lose such a huge presence — and he was a huge presence for about two years,” the speaker goes on. “Time will tell what comes next. Our people act first and think later. I’m more than certain this was no accident,” he says about the crash and those who presumably arranged it. He doesn’t think this is the end of Wagner Group, though. “Our guys went horizontal in droves when [the authorities] needed it. And they will be needed again,” he adds, referring to combat operations. “Africa is nothing,” he shrugs.

A man who says he was connected to Prigozhin ‘by way of the special operation’

These dead are Russia’s most remarkable people who had a vivid, clear position and broadcast it everywhere. This is why there’re people here with flowers, and why they’re crying. They know that the people who were really doing something for our country — who had real victories, and whom everybody loved — they have been taken away. This is why we’re here to show our support for the rest.

“We don’t really care what happens to his assets,” the speaker adds. “Everybody knows what will happen to those assets. But it would be interesting to see what becomes of Wagner Group itself.” He hopes that the PMC won’t fall apart but “keeps serving the country.”

A woman who brought a single flower

“I think of him as a hero,” says a woman with a flower, adding that the mutiny didn’t change her attitude. She thinks that the crash was a “provocation,” and that both Ukraine and the Russian opposition are responsible. The destabilizing “fifth column” is everywhere, she thinks, and trouble in the country is just beginning.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On May 20th, PMC Wagner forced Ukrainian troops out of their last remaining position within the city limits of Bakhmut, consequentially bringing about the nominal end of the largest battle of the 21st century (so far). Bakhmut has been the most substantial locus of military operations in Ukraine for most of the past nine months. Combat there took on a frustrating tempo, with progress often measured in single city blocks. This was a battle that was extremely violent and bloody, but at times agonizingly slow and seemingly indecisive. After countless updates in which nothing of note seemed to have happen, many people were surely beginning to roll their eyes at the very mention of Bakhmut. Consequentially, the abrupt capture of the city by Wagner in May (rather predictably, the final 25% of the city fell very quickly relative to the rest) seemed a bit surreal. To many it likely seemed that Bakhmut would never end - and then, suddenly, it did.

Bakhmut, like most high-intensity urban battles, exemplifies the apocalyptic potential of modern combat. Intense bombardment reduced large portions of the city to rubble, lending the impression that Wagner and the AFU were not so much fighting over the city as its carcass.

The slow pace and extreme destruction has made this battle a rather difficult one to parse out. It all seems so senseless - even within the unique paradigm of war-making. In the absence of an obvious operational logic, observers on both sides have been eager to construct theories of how the battle was actually a brilliant example of four-dimensional chess. In particular, you can easily find arguments from both pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian commentators claiming that Bakhmut was used as a trap to draw in the other side’s manpower and material for destruction, while buying time to accumulate fighting power.

Pro-Ukrainian sources are adamant that a huge amount of Russian combat power was destroyed in Bakhmut, while the AFU received western armor and training to build out a mechanized package to go back on the offensive. Pro-Russian writers similarly seem convinced that the AFU burned a huge amount of manpower, while the Russian army preserved its strength by letting Wagner do most of the fighting.

Clearly, they cannot both be correct.

In this article, I would like to take a holistic survey of the Battle of Bakhmut and adjudicate the evidence. Which army was really destroyed in this “strategically insignificant” city? Which army was being profligately wasteful of its manpower? And most importantly - why did this middling city become the site of the largest battle of the century? Homicide was committed, but nobody can agree on who murdered whom. So, let us conduct an autopsy.

The Road to the Death Pit

The Battle of Bakhmut lasted for so long that it can be easy to forget how the front ended up there, and how Bakhmut fits into the operations in the summer of 2022. Russian operations in the summer were focused on the reduction of the Ukrainian salient around Lysychansk and Severodonetsk, and came to a climactic head when Russian forces broke open the heavy defended Ukrainian stronghold of Popasna, encircled a pocket of Ukrainian forces around Zolote, and approached the Bakhmut-Lysychansk highway. The actual fall of the Lysychansk-Severodonetsk urban agglomeration came relatively quickly, with Russian forces threatening to encircle the entire bag and forcing a Ukrainian withdrawal.

Just for reference, here is what the frontline in the central Donbas looked like on May 1, 2022, courtesy of MilitaryLand:

In this context, Bakhmut already threatened to become a major battleground. It lay at a literal crossroad directly in the center of the Ukrainian salient. As Ukrainian positions in Lysychansk, Popasna, and Svitlodarsk were broken open, the axes of Russian advance converged on Bakhmut.

Ukrainian forces greatly needed to stabilize the front, and establish a stable blocking position, and there was really nowhere else to do this except at Bakhmut. Between Lysychansk and Bakhmut there are no sufficiently robust urban areas to anchor the defense, and there was absolutely no question of failing to adequately defend Bakhmut, for a few reasons that we can enumerate:

Bakhmut is in the central position in this sector of front, and its loss would both threaten Siversk with envelopment and allow Russian forces to bypass the well fortified and strongly held defenses at Toretsk.

The Russian strategic objective at Slavyansk-Kramatorsk cannot be successfully defended if the Russian army controls both the heights to the east (in the Bakhmut area) and Izyum.

Bakhmut itself, meanwhile, was a defensible urban area with dominating heights in its rear, multiple routes of supply, good linkages to other sectors of front, and a peripheral belt of smaller urban areas protecting its flanks.

This set up a rather obvious operational decision for Ukrainian forces. The choice was, all things considered, to either commit reserves to stabilize the front at Bakhmut (a strong and operational vital defensive anchor) or risk letting Russia bypass and sweep away an entire belt of defenses in places like Siversk and Toretsk. Asked to choose between a reasonably good option and an extremely bad option, there was no great controversy in the deciding.

Falling back from the loss of their eastern defensive belt, Ukraine needed to stabilize the front somewhere, and the only suitable place was Bakhmut - so this is where Ukrainian reserves were sent in force, and the AFU chose to fight. Operational logic, indifferent to those things that normally recommend cities to us as “important”, decreed that the Styx should flow through Bakhmut.

Russia came to meet this challenge - bringing as their spearhead a mercenary group, staffed by convicts, wielding shovels, run by a bald caterer. What could go wrong?

Operational Progression

Because the general impression of Bakhmut is characterized by urban combat, it can be easy to forget that most of the battle took place outside the city itself, in the exurbs and fields around the urban center. The approach to Bakhmut is cluttered with a ring of smaller villages (places like Klynove, Pokrovs’ke, and Zaitseve) from which the AFU was able to fight a tenacious defense with the support of artillery in the city itself.

While Russian forces nominally reached the approach to Bakhmut late in June (even before Lysychansk was captured) and the city came under the extremes of shelling range, they did not immediately begin a concerted push to reach it. On August 1, the first assaults on the outer belt of villages began, and the Russian Ministry of Defense stated in its briefings that “battles for Bakhmut” had begun. This date is the most logical starting date for historiographical purposes, so we may firmly say that the Battle of Bakhmut was fought from August 1, 2022 to May 20, 2023 - a total of 293 days.

The first two months of the battle saw the Russian capture of most of the settlements east of the T0513 highway south of the city and the T1302 highway to the north, stripping Bakhmut and Soledar of most of their eastern buffer zones and pushing the line of contact right up to the edge of the urban areas proper.

At this point, the frontlines largely froze up for the remainder of the year, before Wagner set the stage for further advances with the capture of the small village of Yakovlivka, to the north of Soledar. This success can be construed as the first domino in a chain of events which led to Ukrainian defeat in Bakhmut.

Soledar itself serves a unique and critical role in the operational geography of Bakhmut. Laid out in a relatively long and thin strip, Soledar and its suburbs form a continuous urban shield stretching from the T0513 highway (which runs north to Siversk) all the way to the T0504 road (running east to Popasna). This makes Soledar a natural satellite stronghold which defends Bakhmut across nearly ninety degrees of approach. Soledar is also liberally gifted with industrial build, including the salt mine for which it is named, which makes it a relatively friendly place to wage a static defense, full of deep places and strong walls.

Wagner’s capture of Yakovlivka on December 16, however, marked the first sign that the defense of Soledar was in trouble. Yakovlikva sits on an elevated position to the northeast of Soledar, and its capture gave Wagner a powerful position atop Soledar’s flank. The Ukrainians recognized this, and Soledar was powerfully reinforced in response to the loss of Yakovlivka and the anticipated oncoming assault. The capture of Bakhmutske on December 27 (a suburb of Soledar directly on its southern approach) set the stage for a successful assault.

The attack on Soledar ended up being relatively fast and extremely violent, characterized by intense levels of Russian artillery support. The assault began almost immediately after the loss of Bakhmutske on December 27th, and by January 10th Ukraine’s cohesive defense had been shattered. Ukrainian leadership, of course, denied losing the town and wove a story about glorious counterattacks, but even the Institute for the Study of War (a propaganda arm of the US State Department) later admitted that Russia had captured Soledar by January 11th.

The loss of Soledar, in combination with the early January capture of Klischiivka to the south, put Wagner in a position to begin a partial envelopment of Bakhmut.

It was at this point that the discussion shifted towards a potential Russian encirclement of Bakhmut. To be sure, the Russian wings did expand rapidly around the city, placing it in a firebag, but there was never a concerted effort to take the city into a proper encirclement. The Russian advance subsided on the approach to Ivanivske in the south, and over the vital M03 highway in the north.

A genuine encirclement was probably never in the cards, mainly because of the complication of Chasiv Yar - a strongly held rear area stronghold. To fully encircle Bakhmut, Russian forces would have been forced to choose between two difficult options: either blockade the road from Chasiv Yar to Bakhmut, or flare the envelopment wide enough to take Chasiv Yar into the pocket as well. Either option would have greatly complicated the operation, and so Bakhmut was never genuinely encircled.

What the Russians did succeed in doing, however, was establish dominant position on the flanks which accrued three significant advantages. First, they were able to direct fire on Bakhmut’s remaining supply lines. Secondly, they were able to pummel Bakhmut itself with intense artillery fire from a variety of axes. Third - and perhaps most importantly - they were able to assault the Bakhmut urban center itself from three different directions. This, in the end, greatly hastened the fall of the city. By April, it was clear that the focus had shifted from expanding the envelopment on the flanks to assaulting Bakhmut itself, and it was reported that Russian regular units had taken custody of the flanks so that Wagner could clear the city.

Fighting throughout April and early May at last shifted to the struggle in the urban center. AFU units in the city ultimately proved incapable of stopping Wagner’s advance, largely due to tight Russian fires coordination and the cramped confines of the Ukrainian defense - with Wagner advancing into the city from three axes, the firing grids for Russian artillery became very narrow, and the AFU’s static defense - while bravely contested - was slowly ground down.

By early May, it was clear that the city would fall soon, with the AFU desperately holding on to the western edge of the city. Attention soon shifted, however, to a Ukrainian counterattack on the flanks.

This became a rather classic instance of events on the ground being outrun by the narrative. There had been rumors of an impending Ukrainian counterattack circulating for quite some time, advanced by both Ukrainian and Russian sources. Ukrainian channels were predicated on the idea that General Oleksandr Syrskyi (commander of AFU ground forces) had hatched a scheme to draw the Russians into Bakhmut before launching a counterattack on the wings. This idea was seemingly corroborated frantic warnings from Wagner head Yevgeny Prigozhin that the Ukrainians had massed enormous forces in the rear areas behind Bakhmut which would be unleashed to counter-encircle the city.

In any case, the spring months came and went without any astonishing AFU counterattack, and all manner of material shortages and weather delays were blamed. Then, on May 15, all hell seemed to be breaking loose. The AFU finally attacked, and Prigozhin screeched that the situation on the flanks was approaching the worst case scenario.

In fact, what happened was rather anticlimactic. The AFU did bring a hefty grouping of units to play, including several of their best and most veteran formations. These included units from:

The 56th Brigade

The 57th Mechanized Brigade

The 67th Mechanized Brigade

The 92nd Mechanized Brigade

The 3rd Assault Brigade (Azov)

The 80th Air Assault Brigade

The 5th Assault Brigade

This sizeable strike package attacked a handful of mediocre Russian Motor Rifle brigades, achieved a bit of initial success, and culminated with heavy losses. Despite Prigozhin’s assertion that the Russian regulars abandoned their posts and left the Russian wings undefended, we later learned that these forces - including mobilized motor rifle units - doggedly defended their positions and only withdrew under orders from above. These withdrawals (distances of a few hundred meters at most) brought the Russian defensive line to strongly held positions along a series of canals and reservoirs, which the AFU was unable to push through.

Now, this is not to say that Russia did not suffer losses defending against a tenacious Ukrainian attack. The 4th Motor Rifle Brigade, which was largely responsible for the successful defense outside Klishchiivka, was badly chewed up, its commander was killed, and it had to be promptly rotated out. However, the offensive potential of the Ukrainian assault package was exhausted, and there have been no follow on attempts in the past two weeks.

In the end, the vaunted Syrskyi plan looked rather lame. The counterattack did successfully unblock a few key roads out of Bakhmut, but it did nothing to prevent Wagner from finalizing the capture of the city, it burned through the combat power of several premier brigades, and on May 20th the last Ukrainian positions in the city were liquidated.

So. This was a strange battle. An agonizingly slow creep around the flanks of the city, a materializing threat of encirclement, and a sudden concentration of Wagner’s combat energy in the city itself - all taking place under threats of an enormous counteroffensive by the AFU, which turned out to be ineffective and ephemeral.

It’s not obvious, then, how this battle suited the operational logic of either army, nor that anyone would come away fully satisfied. Ukraine obviously lost the battle in nominal terms, but the Russian advance seemed so slow and Bakhmut so strategically random (at least superficially) that Wagner’s success can be portrayed as a pyrrhic victory. To fully adjudicate the Battle of Bakhmut, we need to contemplate relative losses and expenditure of combat power.

The Butcher’s Bill

Estimating combat losses in Ukraine is a difficult task, largely because “official” casualty estimates are often patently absurd. This leaves us with a need to fumble for reasonable figures using proxies and ancillary information. One such important source of knowledge is deployments data - we can get a general sense of the burn rate by the scale and frequency of unit allocation. In this particular case, however, we find that unit deployments are somewhat difficult to work with. Let’s parse through this.

First and foremost, we need to grapple with the incontrovertible fact that a huge share of the Ukrainian military was deployed at Bakhmut at one point or another. The Telegram Channel Grey Zone compiled a list of all the Ukrainian units that were positively identified (usually by social media posts or AFU updates) as being deployed in Bakhmut throughout the nine month battle (that is, they were not there all at once):

This is an absolutely enormous commitment (37 brigades, 2 regiments, and 18 separate battalions (plus irregular formations like the Georgian Legion) which indicates obviously severe losses (for what it’s worth, the pro-Ukrainian MilitaryLand Deployment Map admits a similarly titanic Ukrainian deployment in Bakhmut). However, this does not really get us close to accurately assessing losses, largely because Ukraine’s Order of Battle (ORBAT) is a bit confused. Ukraine frequently parcels out units below the brigade level (for example, their artillery brigades never deploy as such) and they have a bad habit of unit cannibalization.

Doing some extremely rough back of the envelop math, minimal scratching off of just the 37 brigades could easily have pushed Ukraine past 25,000 casualties, but there are all manner of shaky assumptions here. First, this assumes that Ukraine withdraws its brigades when they reach combat ineffective loss levels (15% would be a placeholder number here), which isn’t necessarily true - there is precedent for the AFU leaving troops in place to die, especially from lower quality units like Territorial Defense. In fact, an Australian volunteer (interview linked later on) claimed that the 24th mechanized brigade suffered 80% casualties in Bakhmut, so it’s possible that a great many of these brigades were chewed up beyond task ineffectiveness levels (that is, they were not correctly rotated out) but were instead destroyed entirely. A recent article in the New Yorker, for example, interviewed survivors of a battalion that was almost entirely wiped out. In another instance, a retired Marine Colonel said that units at the frontline routinely suffer 70% casualties.

We can say a few things for certain. First, that Ukraine had an extremely high burn rate which forced it to commit nearly a third of its total ORBAT. Secondly, we know that at least some of these formations were left at the front until they were destroyed. Finally, we can definitively say that pro-Ukrainian accounts are incorrect (or maybe lying) when they say that the defense at Bakhmut was conducted to buy time for Ukraine to build up strength in the rear. We know this first and foremost because Bakhmut insatiably sucked in additional units, and secondly because this burn included a large number of Ukraine’s premier and veteran forces, including fully a dozen assault, airborne, and armored brigades.

There’s another problem with the ORBAT approach to casualties, however, and this concerns Wagner. You see, one of our objectives here is to try to get a sense of the comparative rates of loss, and ORBAT simply isn’t a good way to do this in the particular case of Bakhmut. This is because the battle was mostly fought from the Russian side by the Wagner Group, which is a huge formation with an opaque internal structure.

Whereas on the Ukrainian side we can enumerate a long list of formations that fought at Bakhmut, on the Russian side we just put the 50,000 strong Wagner Group. Wagner of course has internal sub-formations and rotations, but these are not visible to those of us on the outside, and so we cannot get a sense of Wagner’s internal ORBAT or force commitment. We understand generally that Wagner has a structure of assault detachments (probably a battalion equivalent), platoons, and squads, but we do not have a sense of where these units are deployed in real time or how quickly they are rotated or burned through. Sadly, when Prigozhin went in front of cameras he brought maps without unit dispositions on them, leaving ORBAT nerds squinting in vain trying to extract useful information. So, lacking good insight into Wagner’s deployments, we are unable to make an adequate comparison to the bloated Ukrainian ORBAT in Bakhmut.

There are other ways that we can get at the casualties, however. The Russian dissident (that is, anti-Putin) organization Mediazona tracks Russian losses by tabulating obituaries, death announcements on social media, and official announcements. For the entire period of the Battle of Bakhmut (August 1 - May 20), they counted 6,184 total deaths among PMC personnel, inmates, and airborne forces (these three categories accounting for most of the Russian force in Bakhmut).

Meanwhile, Prigozhin claimed that Wagner had suffered 20,000 KIA in Bakhmut while inflicting 50,000 KIA on the Ukrainians. Concerning the first number - the context of this claim was an interview in which he was lambasting the Russian Ministry of Defense (as is his habit), and he has an incentive to overstate Wagner’s losses (since he is trying to play up Wagner’s sacrifice for the Russian people).

So, here is where we are at with Wagner losses. We have a “floor”, or absolute minimum of a little over 6,000 KIA (these being positively identified by name) with a significant upward margin of error , and something like a ceiling of 20,000. The number that I have been working with is approximately 17,000 total Wagner KIA in the Bakhmut operation (with a min-max range of 14,000 and 20,000, respectively).

However, something we need to consider is the composition of these forces. Among the positively identified KIA, convicts outnumber professional PMC operators by about 2.6 to 1 (that is, Wagner’s dead would be about 73% convicts). According to the Pentagon, however (taken with a large grain of salt), nearly 90% of Wagner’s losses are convicts. Taking a conservative 75/25 split and rounding the numbers to make them pretty, my estimate is that Wagner lost about 13,000 convicts and 4,000 professional operators. Adding in VDV losses and motorized rifle units fighting on the flanks, and total Russian KIA in Bakhmut are likely on the order of 20-22,000.

So, what about Ukrainian losses? The major outstanding question remains: who is on the right end of the loss ratios?

Ukrainian commentators consistently ask us to believe that Russian losses were far worse due to their use of “human wave” attacks. There are several reasons why this can be dismissed.

First, we have to acknowledge that after nine months of combat we have not yet seen a single video showing one of these purported human waves (that is, Wagner convicts attacking in a massed formation). Keeping in mind that Ukraine loves to share footage of embarrassing Russian mistakes, that they have no qualms about sharing gory war porn, and that this is a war being fought with thousands of eyes in the sky in the form of reconnaissance drones, it must strike us as curious that not one of these alleged human wave attacks has yet been caught on camera. When videos are shared purporting to show human waves, they invariably show small groups of 6-8 infantry (we call this a squad, not a human wave).

However, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. That being said, the “human wave” narrative has been contradicted on multiple occasions. Just for starters, General Syrskyi himself contradicted the human wave narrative and said that Wagner’s methodology is to push small assault groups forward under intense artillery cover. Witnesses from the front concur. An Australian Army Veteran volunteering in Ukraine gave a very interesting interview in which he downplayed Wagner casualties and instead emphasized that “Ukraine is taking way too many casualties” - he later adds that the 24th brigade suffered 80% casualties in Bakhmut. He also notes that Wagner favors infiltration groups and small units - the veritable opposite of massed human waves.

I found this article from the Wall Street Journal to be nicely emblematic of the human wave issue. It contains the obligatory claim of human wave tactics - “The enemy pays no attention to huge losses of its personnel and continues the active assault. The approaches to our positions are simply littered with the bodies of the adversary’s dead soldiers.” This description, however, comes from the bureaucratic apparatus at the Ministry of Defense. What about people on the ground? A Ukrainian officer at the front says: “So far, the exchange rate of trading our lives for theirs favors the Russians. If this goes on like this, we could run out.”

Ultimately, it’s difficult to believe that the kill ratio favors Ukraine for the simple reason that the Russians have enjoyed a tremendous advantage in firepower. Ukrainian soldiers speak freely about Russia’s enormous superiority in artillery, and at one point it was suggested that the AFU was outgunned by ten to one. The New Yorker’s interview subjects claimed that their battalion’s mortar section had a ration of a mere five shells per day!

The enormous Russian advantage in artillery and standoff weaponry suggests the a-priori assumption that the AFU would be taking horrific casualties, and indeed that’s what we hear from myriad sources at the front. Then, of course, there was the shocking February claim by a former US Marine in Bakhmut that the life expectancy at the front line was a mere four hours.

All of this is really ancillary to the larger point. The enormous inventory of AFU units that were churned through Bakhmut included something on the order of 160,000 total personnel. Taking loss rates of between 25 and 30% (roughly on par with Wagner’s burn rate), it’s clear that Ukraine’s losses were extreme. I believe total irretrievable losses for Ukraine in Bakhmut were approximately 45,000, with some +/- 7,000 margin of error.

So, my current working estimates for losses in the Battle of Bakhmut are some 45,000 for Ukraine, 17,0000 for Wagner, and 5,000 for other Russian forces.

But perhaps even this misses the point.

Ukraine was losing its army, Russia was losing its prison population.

Adjudicating the Battle of Bakhmut is relatively easy when one looks at what units were brought to the table. Bakhmut burned through an enormous portion of the AFU’s inventory, including many of its veteran assault brigades, while virtually none of Russia’s conventional forces were damaged (with the notable exception of the Motor Rifle brigades that defeated the Ukrainian counterattack). Even the Pentagon has admitted that the vast majority of Russian casualties in Ukraine were convicts.

Now, this is all rather cynical - nobody can deny it. But from the unsentimental calculus of strategic logic, Russia churned through its single most disposable military asset, leaving its regular ORBAT not only completely intact, but actually larger than it was last year.

Meanwhile, Ukraine was left with virtually no indigenous offensive power - the only way it can conduct offensive operations is with a mechanized package built from scratch by NATO. For all Ukraine’s bluster, the force commitment at Bakhmut left it unable to undertake any proactive operations all through the winter and spring, its multi-brigade counterattack at Bakhmut lamely fizzled out, and it left its supporters grasping at straws about an immanent counteroffensive to encircle Wagner by a reserve army that doesn’t exist. It was even reduced to sending small flying columns into Belgorod Oblast to launch terror raids, only to have them blown up - discovering that the Russian border is in fact crawling with forces of the very much intact Russian army.

———

I think that ultimately, neither army anticipated that Bakhmut would become the focal point of such high intensity combat, but the arrival of Ukrainian reserves in force created a unique situation. Russia was beginning a process of major force generation (with mobilization beginning in September), and the gridlocked, slow moving, Verdun-like environs of Bakhmut offered a good place for Wagner to bear the combat load while much of the regular Russian forces underwent expansion and refitting.

Ukraine, meanwhile, fell into the sunk cost fallacy and began to believe its own propaganda about “Fortress Bakhmut”, and allowed brigade after brigade to be sucked in, turning the city and its environs into a killing zone.

Now that Bakhmut is lost (or as Zelensky put it, exists “only in our hearts”), Ukraine faces an operational impasse. Bakhmut was after all a very good place to fight a static defense. If the AFU could not hold it, or even produce a favorable loss exchange, can a strategy of holding static fortified belts really be deemed viable? Meanwhile, the failure of the Syrskyi plan and the defeat of a multi-brigade counterattack by Russian motor rifle brigades casts serious doubt on Ukraine’s ability to advance on strongly held Russian positions.

Ultimately, both Ukraine and Russia traded for time in Bakhmut, but whereas Russia put up a PMC which primarily lost convicts, Ukraine bought time by chewing up a significant amount of its combat power. They bought time - but time to do what? Can Ukraine do anything that will be worth the lives it spent in Bakhmut, or was it all just blood for the blood god?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

⚡️ In the north of Mali, Tuareg rebels defeated a convoy of Russian mercenaries from the Wagner PMC.

Russian telegram channels report that at least over 50 Wagnerians were killed. Among those killed were the author of the Russian propaganda channel GreyZone with 500,000 subscribers, codenamed “Bilyi,” and the commander of Russian mercenaries in Mali, Anton Elizarov, codenamed “Lotus.” Elizarov took part in the invasion of Ukraine and led the assaults near Popasna, Severodonetsk, Lysychansk, Vuhlehirsk thermal power plant, and Soledar.

@liveukraine_media

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yulia Kanzeba: volunteering is a very big responsibility

Yulia Kanzeba: volunteering is a very big responsibility Yulia Kanzeba, is from Popasna, the Luhansk region. Since 15, the girl has known what war is like. It came to her home in 2014. After the full- Source : uacrisis.org/en/yuliya…

0 notes

Text

Unbreakable Ukrainians

15 yo girl drove through mine covered road to get several wounded adults out of Popasna. On the way to Bahmut they were hit by russia artillery and the teenager was wounded, but she didn't stop

#ukraine#war in ukraine#ukraine under attack#unbreakable#unbreakable ukrainians#popasna#russian agression#pray for ukraine#pray for ukrainians#stop war#stop russian agression#ukrainians

58 notes

·

View notes

Link

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily Wrap Up August 7, 2022

Under the cut:

Amnesty regrets 'distress' caused by report rebuking Ukraine

Ukraine said on Sunday that renewed Russian shelling had damaged three radiation sensors and hurt a worker at the Zaporizhzhia power plant

Four more ships carrying almost 170,000 tonnes of corn and other foodstuffs sailed from Ukrainian Black Sea ports on Sunday under a deal to unblock the country's exports after Russia's invasion

Footage appears to show fresh atrocity against Ukrainian PoW

“Amnesty International apologised on Sunday for "distress and anger" caused by a report accusing Ukraine of endangering civilians which infuriated President Volodymyr Zelenskiy and triggered the resignation of its Kyiv office head.

The rights group published the report on Thursday saying the presence of Ukrainian troops in residential areas heightened risks to civilians during Russia's invasion.

"Amnesty International deeply regrets the distress and anger that our press release on the Ukrainian military's fighting tactics has caused," it said in an email to Reuters.

"Amnesty International’s priority in this and in any conflict is ensuring that civilians are protected. Indeed, this was our sole objective when releasing this latest piece of research. While we fully stand by our findings, we regret the pain caused."

Zelenskiy accused the group of trying to shift responsibility from Russian aggression, while Amnesty's Ukraine head Oksana Pokalchuk quit saying the report was a propaganda gift for Moscow. read more

Ukrainian officials say they try to evacuate civilians from front-line areas. Russia, which denies targeting civilians, has not commented on the rights report.

In its email on Sunday, Amnesty said it had found Ukrainian forces next to civilian residences in 19 towns and villages it visited, exposing them to risk of incoming Russian fire.

"This does not mean that Amnesty International holds Ukrainian forces responsible for violations committed by Russian forces, nor that the Ukrainian military is not taking adequate precautions elsewhere in the country," it said.

"We must be very clear: Nothing we documented Ukrainian forces doing in any way justifies Russian violations."”-via Reuters

~

“Ukraine said on Sunday that renewed Russian shelling had damaged three radiation sensors and hurt a worker at the Zaporizhzhia power plant, in the second hit in consecutive days on Europe's largest nuclear facility.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy called Saturday night's shelling "Russian nuclear terror" that warranted more international sanctions, this time on Moscow's nuclear sector.

"There is no such nation in the world that could feel safe when a terrorist state fires at a nuclear plant," Zelenskiy said in a televised address on Sunday.

However, the Russian-installed authority of the area said it was Ukraine that hit the site with a multiple rocket launcher, damaging administrative buildings and an area near a storage facility.

Reuters could not verify either side's version.

Events at the Zaporizhzhia site - where Kyiv had previously alleged that Russia hit a power line on Friday - have alarmed the world.

"(It) underlines the very real risk of a nuclear disaster," International Atomic Energy Agency head Rafael Mariano Grossi warned on Saturday.”-via Reuters

~

“Four more ships carrying almost 170,000 tonnes of corn and other foodstuffs sailed from Ukrainian Black Sea ports on Sunday under a deal to unblock the country's exports after Russia's invasion, Ukrainian and Turkish officials said.

The United Nations and Turkey brokered the agreement last month after warnings that the halt in grain shipments caused by the conflict could lead to severe food shortages and even outbreaks of famine in parts of the world.”-via Reuters

~

“Horrific video and photos have emerged that appear to show the head of a Ukrainian prisoner of war stuck on a pole outside a house in the eastern Ukrainian city of Popasna, which was captured by Russian forces in May and is close to the current frontline in the Donbas.

The Ukrainian governor of Luhansk province, Serhiy Haidai, posted the gruesome photo on his Telegram channel. It has since been widely shared on social media. Ukrainians have accused Russian troops of barbaric medieval behaviour and likened the image to Lord of the Rings.

“They really are orcs. Twenty-first century, occupied Popasna, human skull on the fence,” Haidai wrote. “There is nothing human about the Russians. We are at war with non-humans.”

The Guardian has not confirmed the authenticity of the photo. Geolocation tools suggest it is genuine and was taken in late July, not far from the centre of Popasna. A sign on a wall says “21 Nahirna Street”.

The video shows the headless and handless body of a man dressed in military uniform. A head is stuck on a wooden pole. Two hands have been placed on metal spikes on a fence either side of the head, in what looks like a front garden.

The Ukrainian army retreated from Popasna in early May. The president of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, claimed his troops had seized control of the town. In July Russian forces captured the entirety of Luhansk province.

On Saturday they were attempting to storm the city of Bakhmut, 18 miles (30km) west of Popasna, in neighbouring Donetsk oblast. Fierce fighting was continuing, Ukrainian officials confirmed, with the Russians edging towards the city’s western outskirts.

The photo is the latest apparent atrocity committed by Moscow’s soldiers since Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February. Last week footage emerged of a Chechen fighter allegedly castrating a bound Ukrainian prisoner, who was then shot dead.”-via The Guardian

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 87 🇷🇺 #Russia's Invasion of 🇺🇦 #Ukraine #Zelensky warns only talks can end war as Russia cuts #Finland gas. #UK wants #Moldova armed ‘to #NATO standards’ to reduce Russian invasion threat. Russia's offensive near #Popasna threatens #Sievierodonetsk in #Luhansk Oblast of #Donbas. -aje.io/pwu8jq -https://www.trtworld.com/europe -https://www.bbc.com/news/world-60525350 -https://www.cnn.com/europe/live-news/russia-ukraine-war-news-05-21-22/index.html -https://apnews.com/hub/russia-ukraine -https://abcn.ws/3ulqqBJ -https://cnb.cx/3Glic13 -https://twitter.com/i/events/1483255084750282753 -https://www.newsweek.com/topic/russia-ukraine-war -https://www.theguardian.com/international -https://euromaidanpress.com/2022/05/19/russo-ukrainian-war-day-85-guerrillas-blow-up-russian-armored-train-in-occupied-melitopol/ https://www.instagram.com/p/Cd1AHKQBqOA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Streetart by #SethGlobepainter @ #Popasna, Ukraine, for #BackToCchool Curated by #SkyArtFoundation @skyartfoundation @seth_globepainter #arte #art #graffiti #murals #mural #murales #murali #arteurbana #urbanart #muralism #muralismo #cultureisfreedom #artisfreedom #curiositykilledtheblogger #artblogging #photooftheday #artaddict #artistsoninstagram #artcurator #artwatchers #artcollectors #artdealer #artlover #contemporaryart #artecontemporanea https://www.instagram.com/p/B289vPiH-ug/?igshid=13hfw606q2fbj

#streetart#sethglobepainter#popasna#backtocchool#skyartfoundation#arte#art#graffiti#murals#mural#murales#murali#arteurbana#urbanart#muralism#muralismo#cultureisfreedom#artisfreedom#curiositykilledtheblogger#artblogging#photooftheday#artaddict#artistsoninstagram#artcurator#artwatchers#artcollectors#artdealer#artlover#contemporaryart#artecontemporanea

1 note

·

View note

Text

#popasna#ukraine#russian army#russian nazism#russian barbarism#russian war#russian imperialism#help for ukraine#russia ukraine war#putin's war#criminal war#war#criminal putin#putin#fuck putin#russian occupation#stop invasion#stop russia#stop putin#stop war#isolation from russia

1 note

·

View note

Text

Russian forces, led by the Wagner mercenary group, have been waging an offensive to gain control of Bakhmut for more than seven months now. As of March 21, Wagner Group claims to have captured 70 percent of the city, and it increasingly appears likely to gain control of the rest. Ukraine’s military command has nevertheless chosen to keep defending the city, even at the expense of reserve forces. This may have delayed Wagner’s progress, but it hasn’t been enough to stop it. Meanwhile, Russia’s regular army, which is trying simultaneously to press forward in multiple areas against Ukraine’s more modest forces, has had little success in recent months. What is it that makes Wagner Group Russia’s most successful fighting force at this stage of the war? And how might the Ukrainian military respond more effectively? Meduza explains.

How Wagner Group waged war in Ukraine over the last year

For the first few weeks of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, the private military company controlled by Putin-associate Evgeny Prigozhin (known as Wagner Group) was not involved. It wasn’t until April 2022 that Wagner units were deployed in Popasna, a Ukrainian-held city in the Luhansk region that had been on the contact line between Ukrainian troops and Russian proxy forces since 2015 and was thus well-equipped to defend itself.

At that point, Russia’s military command, which had by then suffered defeats in the Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Mykolaiv regions, launched offensives in multiple directions at once in the Donbas. Most of these assaults failed, but Wagner mercenaries managed to dislodge the Ukrainian military from Popasna (and Russian troops managed to take the city of Lyman).

The advance ended there

It’s been clear since the battle for Popasna that Wagner Group’s tactics are well-suited for this war’s conditions. One video from that period shows an assault group of mercenaries overtaking the positions of a larger Ukrainian unit with help form a reconnaissance drone. The clip stands in stark contrast to the images of urban combat that emerged from Mariupol and Rubizhne around the same time.

In October, Wagner Group had grown so large that it was assigned a significant portion of the front that stretched from northern Horlivka to Soledar (regular Russian troops are also stationed there and have played a supporting role since the fall). By November, when the Ukrainian military liberated Kherson and tried to advance on Svatove in the northern part of the Luhansk region, it became clear that Wagner Group was preparing an operation to capture Soledar and Bakhmut, despite Russian troops’ difficulties elsewhere along the front.

The Ukrainian military started redirecting its troops to the area around Bakhmut (including units that were freed up by the liberation of Kherson) and later even dismantled a group of forces deployed around Svatove to strengthen its defenses further in the center of the Donbas. To this day, however, these forces have been unable to halt Wagner Group’s slow advance. At the same time, none of the other offensives Russian forces have launched throughout the winter have yielded any significant results.

The key to Wagner Group’s effectiveness (and costliness)

In its scale and the size of the area it covers, Wagner Group is roughly comparable to the Russian military’s four groups of forces in Ukraine that are formed on the basis of the country’s Western, Central, Eastern, and Southern military districts. The mercenaries have their own artillery and even some level of aviation power.

Available details about the group’s structure and methods are limited. Most of the information we have comes from stories the mercenaries themselves have told to the “war correspondents” who work for entities owned by Wagner Group founder Evgeny Prigozhin. These stories are few in number and often vague.

Additionally, there is Ukrainian drone footage of Wagner fighters, reports from Ukrainian soldiers, and information from journalists who have interviewed soldiers and studied documents captured by Ukrainian troops. Independently confirming the authenticity of these reports is difficult, but, overall, they don’t contradict the documentary evidence from the Russian side, the drone footage, and what we know about the course of combat operations.

How Wagner Group differs from Russia’s regular forces

Wagner Group’s command shows a level of flexibility that the Russian Armed Forces lack. In the battle for Bakhmut, the group has repeatedly altered the directions of its major assaults. While it seemed in November that the mercenaries intended to attack and surround Bakhmut from the south, in early December, they suddenly replaced forces from the self-declared “Donetsk People’s Republic” around Soledar and captured several important suburbs (Yakovlivka and Bakhmutske). After that, the group once again shifted its focus to the south of Bakhmut, gaining control of part of the suburbs of Opytne before focusing its forces back on Soledar, which ultimately led to the town’s capture. This was followed by an attack further south, where Wagner forces captured Klishchiivka, a village that had been vital to Ukraine’s defense of Bakhmut. These frequent shifts in the direction of impact took a clear toll on Ukraine’s reserve forces. This approach differs fundamentally, for example, from the offensive on Vuhledar, where Russia’s command (from the Eastern Military District) has repeatedly been launching attacks along the same routes for months.

Wagner Group seems to be significantly more capable of concentrating its forces and resources on a target and appears to have successfully established cohesion between its assault units and support forces, including artillery and aviation forces.

Still, the mercenaries do have their weaknesses. Unlike the Russian Armed Forces, Wagner Group doesn’t even attempt to use mechanized units to launch quick strikes deep behind enemy defense lines. Instead, its units carry out their attacks on foot, only using armored vehicles (judging from videos and reports from Ukrainian soldiers) for transportation to the rear and to launch strikes from long distances. After capturing a Ukrainian position, Wagner Group typically embeds its forces there, tries to secure its flanks, and prepares its next attacks. The end result is methodical but slow progress. This allows the Ukrainian Armed Forces to send reinforcements to wherever the mercenaries are carrying out an attack. From July 2022 to mid-March, Wagner units didn’t progress in any direction more than 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) from Popasna (where they entered the war).

Wagner Group’s methods also demand enormous resources. In addition to suffering heavy losses in manpower, the group rapidly burns through ammunition; Prigozhin recently reported that he needs 10,000 metric tons of it per month. It’s not clear exactly what kind of ammunition he means, but if he’s referring only to shells and missiles for multiple rocket launchers (with the average weight of one of these munitions at 50 kilograms or 110 pounds), that means Wagner Group uses more than 6,500 rounds per day. That’s more than Ukraine’s Armed Forces use across the entire battlefield during the same period (according to Ukraine’s military command).

Different tactics

Wagner Group’s forces are organized into assault detachments that are themselves made up of assault groups. Ukrainian soldiers and journalists have reported that a Wagner assault group can contain between seven and fifty fighters.

Assault groups try to approach Ukrainian positions unnoticed (by moving at night, taking cover on the ground, etc.). Practically every group is accompanied by a reconnaissance drone (whereas the Russian Armed Forces are experiencing a drone shortage), which studies Ukraine’s positions in detail. Group commanders and their deputies reportedly receive detailed plans on electronic maps, which show the routes each mercenary should take. According to intelligence data, the resources necessary for each battle are also calculated in advance (including the number of stormtroopers that will give the group a numerical advantage and the amount of ammunition necessary to suppress Ukraine’s firing points).

Most Wagner units have reinforcements in the form of artillery that “process” Ukrainian positions after they’re attacked. Suppression fire from these reinforcements makes it possible for storm groups to get close to the targeted positions. After that, a “fire group” carries out strikes on identified Ukrainian firing points from mortars, automatic grenade launchers, and/or hand grenade launchers.

Afterward, the mercenaries begin storming the trenches or buildings where Ukrainian troops are posted. These attacks are guided by commanders who are observing the events remotely with the help of drones, using protected means of communication.

Wagner storm groups demonstrate more resilience than the Russian military; if an attack fails, they can mount it again. Wagner Group artillery gunners attempt to prevent Ukrainian reserve forces from approaching the battlefield.

Wagner mercenaries rarely use armored vehicles in close combat, but they use aviation more liberally than the Russian Aerospace Forces (Russian army aircraft try not to fly in areas reachable by Ukraine’s air defenses, whereas Wagner Group planes actively fly directly over the battlefield). At the same time, the mercenary group has both significantly less air power and a higher casualty rate.

Judging from videos, Wagner Group’s artillery is widely dispersed across the battlefield, allowing it to avoid extensive damage. This also facilitates effective management and communication. In the regular Russian army (at least in the war’s early stages), artillery was stationed close together and suffered heavy losses.

The downside of these tactics is significant: Wagner Group’s assault units consistently suffer heavy personnel losses. At the same time, according to Ukrainian soldiers and journalists, the highest losses are among the mercenaries (especially the recruited convicts) who storm Ukrainian trenches directly. Wagner Group’s command, incidentally, isn’t shy about spending what it views as a “cheap resource” while retaining its well-trained and experienced specialists.

This approach is largely in line with the standard assault tactics that were developed during the First World War. The main difference between Wagner Group and the Russian army, judging by various available descriptions of their activity, is that Wagner tends to gain the advantage over Ukraine by gathering and using intelligence and making quick decisions — in other words, the same practices that give the Ukrainian military an advantage over the Russian Armed Forces.

Can the Ukrainian military withstand these tactics?

According to Ukrainian military personnel who have studied Wagner Group’s tactics, the Ukrainian military’s problem is that many of its defense forces are static: soldiers are constantly sitting in the trenches or the buildings where they’ve been commanded to stay. Often, they don’t have enough intelligence resources (such as drones) for constant assessments of possible approaches by Russian mercenaries.

Finally, part of the problem comes from the Ukrainian military command’s own decision-making. For most of the battle for Bakhmut, Russia’s mercenaries had a numerical advantage. In those conditions, Kyiv had two least-bad options:

Transfer significant reserves to the part of the front that was under threat, equalize the balance of forces, and try to regain the initiative

Retreat and transfer its forces that were defending Bakhmut to more defensible positions

So far, however, Kyiv hasn’t chosen either option. The troops it has transferred to Bakhmut, meanwhile, haven’t been enough. Most likely, Ukraine’s military will be forced to decide sooner or later, but in worse conditions than if it had done so, for example, a month ago.

Why the Russian army doesn’t try to fight like Wagner Group

It’s possible that Russian commanders want to emulate Wagner Group. Ukrainian sources have published what they claim are stolen instructions for creating assault groups in the regular Russian army. These groups differ from Wagner Group assault groups in that they’re theoretically reinforced with armored vehicles. According to the documents, the groups make up larger assault battalions.

These kinds of storm detachments are already used in many units of the Russian Armed Forces and have even reportedly been “successfully applied” against Ukraine’s static defenses in weak spots. But recreating Wagner Group’s success will be difficult for the Russian army. The units containing the storm detachments are far from uniform: many of them suffer from chronic shortages of reconnaissance assets and protected communications systems, and their commanders are not inclined to show flexibility.

Additionally, in terms of political salience, the war would be much harder to square with Russia’s general public if draftees were to start dying at the same rate as Wagner fighters in recent months. The Russian authorities will likely do their best to avoid this situation.

Burning out

Despite its achievements on the battlefield, the future of Wagner Group itself is uncertain. In all likelihood, Evgeny Prigozhin has run afoul of the Russian Defense Ministry, which he has regularly accused of refusing to provide his mercenaries with the weapons they need since February 2023. In his account, this failure on the ministry’s part impeded the capture of Bakhmut and led to additional losses among Wagner fighters. The Defense Ministry has denied the accusations, saying supply requests from “volunteer units in 2022 were fulfilled by 140 percent.”

At the same time, according to Prigozhin, he’s no longer allowed to recruit prisoners, and Wagner Group’s forces are likely to shrink, as a result. The mercenary company now plans to replace convicts with “free” volunteers, but this resource has largely been exhausted over the last year.

Despite all the ink spilled in recent months about the fighting between Prigozhin and Russia’s military command, it’s still hard to gauge the conflict’s seriousness or what it means for Wagner Group’s role in the war going forward.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Also “Ukraine war: Refugee from Popasna spots looted possessions on Russian tank” by Robert Greenall (BBC).

Alina Koreniuk says the box in the photo contains a new boiler she planned to install before the war started.

Apart from the boiler, other items on the tank include a tablecloth from the family's summer house, new Disney bedsheets for her children and a red blanket, she says.

0 notes

Text

Una normale giornata di guerra

Una normale giornata di guerra

E’ giunto finalmente il comunicato ufficiale: “Grazie a misure senza precedenti adottate dalla dirigenza della Federazione Russa, con la partecipazione attiva dei rappresentanti delle Nazioni Unite e del Comitato Internazionale della Croce Rossa, l’operazione umanitaria per evacuare i civili dallo stabilimento di Azovstal è ora completata”. Così i corridoi umanitari sono stati chiusi e nei…

View On WordPress

0 notes