#Pasko Simone

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Spoilers for comics in January 2025!

You can see them in full at Adventures In Poor Taste.

It's mostly just reprints for that month, but here's the Flash solicit now that we know Marco will be in the upcoming Skartaris storyline. Strangely, no cover is provided.

THE FLASH #17 Written by SIMON SPURRIER Art by VASCO GEORGIEV Cover by MIKE DEL MUNDO Variant covers by DIKE RUAN and BALDEMAR RIVAS $3.99 US | 32 pages | Variant $4.99 US (card stock) ON SALE 1/22/25 As The Flash races to contain damage to Skartaris, forces both below and above ground make their move to grasp power. The Flash Family vacation leads the West clan to meet the one and only Warlord!

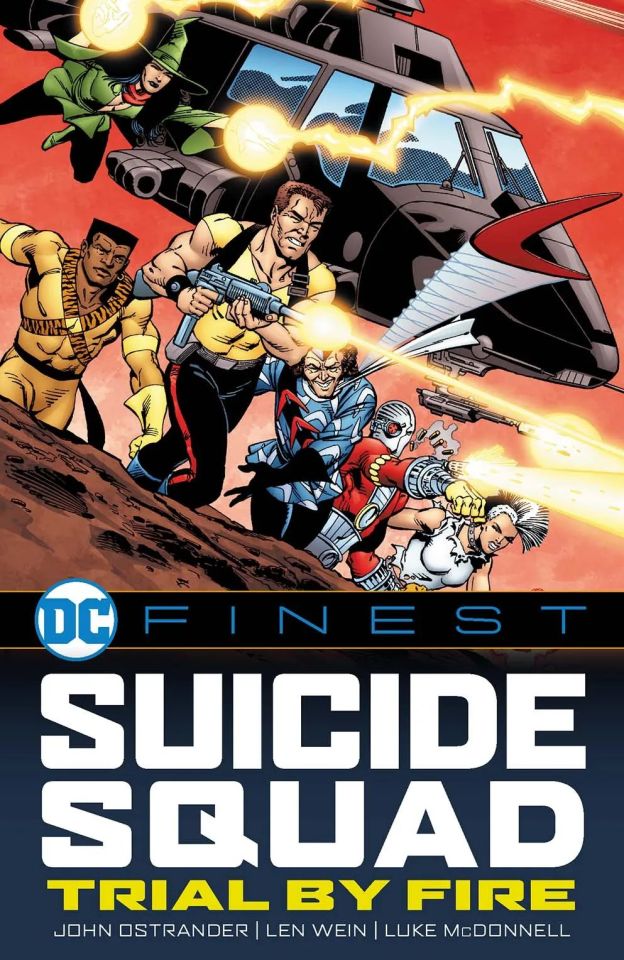

This next book is obviously a collection with tons of Digger, so fans of his might want to pick it up!

DC FINEST: SUICIDE SQUAD: TRIAL BY FIRE Written by JOHN OSTRANDER Art by LUKE McDONNELL, JOHN BYRNE, JOE BROZOWSKI, and more Cover by LUKE McDONNELL and KARL KESEL $39.99 US | 560 pages | 6 5/8″ x 10 3/16″ | Softcover | ISBN: 978-1-77950-075-9 ON SALE 3/11/25 Task Force X was created in World War II to neutralize metahuman and supernatural threats. Over time, the roster was updated to include incarcerated supervillains who could reduce their prison sentences if they went on dangerous assignments that were deemed suicide missions. Thus, Task Force X earned a new nickname: the Suicide Squad! This first collection of John Ostrander and Luke McDonnell’s classic run includes stories from Suicide Squad #1-10, Secret Origins #14, Detective Comics #582, The Fury of Firestorm #62-64, Firestorm: The Nuclear Man Annual #5, Legends #1-6, and Millennium #4.

This next trade should include a couple of stories with Rogues, since Kadabra appears in a couple of these stories, and some other Rogues appear a bit too.

LIMITED COLLECTORS’ EDITION #48 FACSIMILIE EDITION Written by E. NELSON BRIDWELL and JIM SHOOTER Art by CURT SWAN, ROSS ANDRU, NEAL ADAMS, CARMINE INFANTINO, GEORGE KLEIN, and DICK GIORDANO Cover by CARMINE INFANTINO, JOSÉ LUIS GARCÍA-LÓPEZ, and BOB OKSNER $14.99 US | 56 pages ON SALE 1/22/25 The greatest races of all time between Superman and the Flash are reproduced in this tabloid-size facsimile of the 1976 Limited Collectors’ Edition classic. In addition to tales of super-speed, this issue includes bonus features like a tour of Superman’s Fortress of Solitude drawn by Neal Adams and “How to Draw the Flash!” by Carmine Infantino. Test your knowledge with a Flash puzzle and be sure to buy a second copy to cut out the tabletop diorama on the back cover.

The next trade has a Bronze Age Eobard story in it (the one in which he gets salty about being called the Reverse Flash).

DC FINEST: TEAM-UPS: CHASE TO THE END OF TIME Written by MARTIN PASKO, DAVID MICHELINIE, LEN WEIN, and more Art by JOSÉ LUIS GARCÍA-LÓPEZ, MURPHY ANDERSON, CURT SWAN, and more Cover by JOSÉ LUIS GARCÍA-LÓPEZ and DAN ADKINS $39.99 US | 560 pages | 6 5/8″ x 10 3/16″ | Softcover | ISBN: 978-1-77950-082-7 ON SALE 3/18/25 The Man of Steel and the Flash! The Caped Crusader and Black Canary! See the World’s Finest duo of Superman and Batman join forces with other DC superheroes in DC Finest: Team-Ups: Chase to the End of Time, collecting some of the most exciting team-up stories from the Bronze Age of comics from May 1978 to October 1979. Featuring the works of some of the greatest artists and writers in comics, this volume contains stories from DC Comics Presents #1-14 and The Brave and the Bold #141-155.

#Captain Boomerang#Weather Wizard#the Flash#Professor Zoom#Reverse Flash#Superman#spoilers: comics#solicits

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a drawing based on this video.

youtube

Instead of using Fart sounds, I thought of an idea of including music from a video game we know. Unlike hearing Reverb sounds back on Twitch when watching a stream with Dani, I thought of a Song which is in the Pal Version of Gran Turismo 2, and I call it Fatboy Slim In Heaven. So before the Ramcats and the Speedsters are getting ready to go somewhere for Christmas like a Party or go out to Dinner for Christmas like Christmas Eve. So Debby and Rita are both Checking on Shadow and Spot to see if they're both ready, but when they ask what they're both listening to, but Shadow and Spot told their moms they wouldn't like it. But they think they like these kinds of generation of music. When Shadow and Spot played the song, they listened to the music, until the Fatboy Slim swore about Heaven, they made Debby and Rita shocked because it sounded like Sacreligious Trash talk. They asked where they both recorded it, but Shadow and Spot both bought it at the Bookstore since it is the Fatboy Slim. And they played the Simons GT Mix in the Pal Version of Gran Turismo 2. So Rita and Debby told Shadow and Spot that there's nothing funny about that song. And Debby said that the artist who sings that song is a Dirty Sinner. So they both told Shadow and Spot to get their Winter Clothes on and get ready to go out somewhere for Christmas. So Shadow and Spot does so. Then Rita and Debby thought they wouldn't listen to that song again and not even they would show it to their husbands.

Shadow and Spot: *listening to music while they get their A/W Clothes on while their moms entered the room*

Rita 🐶🚺: What are you both Nakikinig mga, bata? (Listening to children?) 🙂

Shadow R 😺🗡️: I don't think you guys will like it. 🙁

Debby 😺📱🖥️: How come? We love these kinds of generations of music. 🙂

Both: *put on Shadow and Spot's Earbuds and listen to the song, until the lyrics say "Fatboy Slim is Effing in Heaven"*

Rita 🐶🚺: Mahal Ko (Dear me) this is Kalapastanganan (Sacreligious) trash talk! 😧

Debby 😺📱🖥️: Where did you guys record this? 😦

Shadow R 😺🗡️: We bought it at the Bookstore. It's one of the Fatboy Slims.

Spot 🐶🏎️: They even played the Simons GT Mix in the Gran Turismo 2 Pal Version.

Rita 🐶🚺: Let us tell you something, mga Anak. There's nothing Nakakatuwa (Funny) about this Kanta (Song). 😠

Debby 😺📱🖥️: What that person who sings that song, is a dirty sinner! 😠

Rita 🐶🚺: Now you Anaks get ready for the Pasko (Christmas) outing. Okay? 🙁

Both: Yes, Mom. 🙁

*Debby and Rita left the room*

Rita 🐶🚺: Let's hope we don't show that Kanta (Song) to our Asawas. (Husbands) 😐

Debby 😺📱🖥️: Agree. 😐 So what should we do for Christmas, Rita? Should we go to a Party or go out to dinner? 🤔

Rita 🐶🚺: We'll see what the Pamilyang Kuneho (Rabbit Family) think, Deb. 🤔

Debby 😺📱🖥️: Okay. 👍

People I tagged @murumokirby360 @bryan360 @sammirthebear2k4 and @alexander1301

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

DC Yuritober Drabbles Days 1-10

read it on AO3 at https://ift.tt/JdzGgeR by sadifura An assortment of DC Yuri Drabbles for DC Yuritober, since...I doubt my confidence in drawing said ships (especially Taelyr...I can't do Jess Taylor's art justice!!). None of these characters belong to me. Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Taylor Barzelay as well as Kat Silverberg belong to Jadzia Axelrod and Jess Taelyr, Barbara Gordon's portrayal as Oracle as well as my portrayal of Dinah Lance belongs to Gail Simone, my Bruce/Bea Wayne portrayal, although somewhat mine, belongs to Paul Dini, Alan Burnett, Martin Pasko, and Michael Reeves, as is my portrayal of Andrea Beaumont, my portrayal of Mandy Anders belongs to Mariko Tamaki, my portrayals of Cassandra Cain and Stephanie Brown are pretty much cobbled together from their best portrayals (I hope), my portrayals of Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy are a mix of Paul Dini incarnations and some others, my portrayal of Catwoman is a mix of Paul Dini and Michael J. Stern, my portrayal of Bibi and Jestah are Michael J. Stern compliant, and my portrayal of Karen Starr is consistent with Amanda Conner, Justin Gray, and Jimmy Palmiotti's version. Words: 534, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English Series: Part 1 of DC Yuritober Drabble Collection Fandoms: DC Extended Universe, Galaxy: The Prettiest Star - Jadzia Axelrod & Jess Taylor (Graphic Novel), Birds of Prey (Comics), Harley Quinn (Comics), Batman - All Media Types, Batman (Comics), Batwheels (Cartoon), I Am Not Starfire (Graphic Novel), Power Girl (Comics) Rating: Not Rated Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Categories: F/F Characters: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Taylor Barzelay, Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon, Dinah Lance, Helena Wayne, Stephanie Brown, Cassandra Cain, Bruce Wayne, Andrea Beaumont, Mandy Anders, Harleen Quinzel, Pamela Isley, Selina Kyle, Bibi (Batwheels), Jestah (Batwheels), Karen Starr | Kara Zor-L Relationships: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Kat Silverberg, Taylor Barzelay/Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon/Dinah Lance, Andrea Beaumont/Bruce Wayne, Stephanie Brown/Cassandra Cain, Mandy Anders/Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Mandy Anders/Taylor Barzelay, Pamela Isley/Selina Kyle/Harleen Quinzel, Bibi/Jestah (Batwheels), Kara Zor-El | Karen Starr | Power Girl/Harleen Quinzel/Harley Quinn Additional Tags: Trans Female Character, Trans Bruce Wayne, Trans Female Bruce Wayne/Bea Wayne, Nonhuman Characters, Alien/Human Relationships, Disabled Character, Canon Disabled Character, Drabbles, Drabble Collection, DC Yuritober, Femslash, Fluff, Fluff and Angst, Angst with a Happy Ending, Character Study, Polyamory, Established Relationship, maybe requited love read it on AO3 at https://ift.tt/JdzGgeR

0 notes

Text

DC Yuritober Drabbles Days 1-10

read it on AO3 at https://ift.tt/wv82ygB by sadifura An assortment of DC Yuri Drabbles for DC Yuritober, since...I doubt my confidence in drawing said ships (especially Taelyr...I can't do Jess Taylor's art justice!!). None of these characters belong to me. Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Taylor Barzelay as well as Kat Silverberg belong to Jadzia Axelrod and Jess Taelyr, Barbara Gordon's portrayal as Oracle as well as my portrayal of Dinah Lance belongs to Gail Simone, my Bruce/Bea Wayne portrayal, although somewhat mine, belongs to Paul Dini, Alan Burnett, Martin Pasko, and Michael Reeves, as is my portrayal of Andrea Beaumont, my portrayal of Mandy Anders belongs to Mariko Tamaki, my portrayals of Cassandra Cain and Stephanie Brown are pretty much cobbled together from their best portrayals (I hope), my portrayals of Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy are a mix of Paul Dini incarnations and some others, my portrayal of Catwoman is a mix of Paul Dini and Michael J. Stern, my portrayal of Bibi and Jestah are Michael J. Stern compliant, and my portrayal of Karen Starr is consistent with Amanda Conner, Justin Gray, and Jimmy Palmiotti's version. Words: 534, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English Series: Part 1 of DC Yuritober Drabble Collection Fandoms: DC Extended Universe, Galaxy: The Prettiest Star - Jadzia Axelrod & Jess Taylor (Graphic Novel), Birds of Prey (Comics), Harley Quinn (Comics), Batman - All Media Types, Batman (Comics), Batwheels (Cartoon), I Am Not Starfire (Graphic Novel), Power Girl (Comics) Rating: Not Rated Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Categories: F/F Characters: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Taylor Barzelay, Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon, Dinah Lance, Helena Wayne, Stephanie Brown, Cassandra Cain, Bruce Wayne, Andrea Beaumont, Mandy Anders, Harleen Quinzel, Pamela Isley, Selina Kyle, Bibi (Batwheels), Jestah (Batwheels), Karen Starr | Kara Zor-L Relationships: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Kat Silverberg, Taylor Barzelay/Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon/Dinah Lance, Andrea Beaumont/Bruce Wayne, Stephanie Brown/Cassandra Cain, Mandy Anders/Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Mandy Anders/Taylor Barzelay, Pamela Isley/Selina Kyle/Harleen Quinzel, Bibi/Jestah (Batwheels), Kara Zor-El | Karen Starr | Power Girl/Harleen Quinzel/Harley Quinn Additional Tags: Trans Female Character, Trans Bruce Wayne, Trans Female Bruce Wayne/Bea Wayne, Nonhuman Characters, Alien/Human Relationships, Disabled Character, Canon Disabled Character, Drabbles, Drabble Collection, DC Yuritober, Femslash, Fluff, Fluff and Angst, Angst with a Happy Ending, Character Study, Polyamory, Established Relationship, maybe requited love read it on AO3 at https://ift.tt/wv82ygB

0 notes

Text

This is the Christmas Station ID of TV5 in 2010. The Christmas Station ID was themed “Maligayang Pasko, Kapatid! In the Service of the Filipino”. The Station ID is accompanied with the Christmas version of “Para Sa’yo Kapatid” performed by Filipino singer, songwriter, rapper, dancer, television host, actor and comedian Ogie Alcasid and his wife Regine Velasquez who is also an OPM singer and songwriter. But somehow, Ogie Alcasid and Regine Velasquez also performed the original version of the “Para Sa’yo Kapatid” in June 30, 2010.

The Christmas Station ID was launched in December 1, 2010 which is the same thing that the “Da Best ang Pasko ng Pilipino” music video was released from ABS-CBN.

The Christmas Station ID features Korina Sanchez, Pia Arcangel, Luchi Cruz-Valdez, Raffy Tima, Mark Salazar, Atom Araullo, Gilbert Remulla, Shawn Yao, Pinky Webb, Connie Sison, Martin Andanar, Seph Ubalde, Howie Severino, Rhea Santos, Alex Santos, Lourd de Veyra, Ivan Mayrina, Sam Milby, Marco Alcaraz, Ivana Alawi, Arjo Atayde, Kit Thompson, Vice Ganda, Empoy Marquez, Coco Martin, Zoren Legaspi, Ogie Alcasid, Jun Sabayton, Niño Muhlach, Simon Ibarra, Ramon Bautista, Baron Geisler, Dominic Roque, DingDong Avanzado, Eric Fructuoso, Randy Santiago, Diether Ocampo, Carmina Villaroel, Eugene Domingo, Nora Aunor, Sunshine Dizon, Sue Ramirez, Maja Salvador, Louise de los Reyes, Jazz Ocampo, Enrique Gil, Marco Gumabao, Liza Soberano, Michael V., Allan K., Xian Lim, Yves Flores, German Moreno, Carmelito “Shalala” Reyes, Romy “Dagul” Pastrana, Ruru Madrid, Juancho Triviño, Ina Raymundo, Gretchen Barretto, Ahron Villena, Mark Anthony Fernandez, Chuckie Drefyus, Jerald Napoles, Jeric Gonzales, Tirso Cruz III, Rafael Rosell, Adrian Alandy, Enrico Cuenca, JC de Vera, Sef Cadayona, Dion Ignacio, Gerald Anderson, Edgar Allan Guzman, Mark Herras, Sid Lucero, Diego Castro III, Vince Gamad, Angel Locsin, Ivan Dorschner, Enzo Pineda, Hero Angeles, CJ Muere, Dennis Trillo, Jake Cuenca, Paulo Avelino, IC Mendoza, Carlo Aquino, Derrick Monasterio, David Licauco, Ken Chan, Kim Chiu, Arcee Muñoz, Alice Dixson, Tuesday Vargas, Ritz Azul and Eula Caballero including Julius Babao and his wife Christine Bersola-Babao, Mikoy Morales, the son of Vicky Morales, Bela Padilla and Kylie Padilla, daughters of Rommel Padilla, sisters of Queenie Padilla, nieces of Robin Padilla and cousins of Daniel Padilla and RJ Padilla, Ronwaldo and Kristoffer Martin, the sons of Coco Martin and Sandino Martin, the brother of Coco Martin, twin brothers Rodjun and Rayver Cruz, Master Boy Abunda, DJ Willie Revillame, Emcee Mo Twister, girl group BTS, supergroup Bravo All-Stars including the Goin Bulilit new cast members after the retirement of the original cast members, DJ Lance the Dinosaur from Sesame Street, featuring president Noynoy Aquino as Santa Claus.

The Christmas Station ID also features special guests Daniel Padilla, Alwyn Uytingco, Dominic Roco, Felix Roco, DingDong Dantes, Rocco Nacino and Enchong Dee as the cast from the future Beyblade Burst series which will be released in 2013. Somehow, The manga version will be released in 2012 at this point. But eventually, DingDong Dantes signed a temporary contract to TV5 in 2010. But somehow, His contract to TV5 will expire in January 31, 2011. Eventually, He was an actor from ABS-CBN since 1992. But somehow, Daniel Padilla, Alwyn Uytingco, Dominic Roco, Felix Roco, Rocco Nacino and Enchong Dee were from TV5 from 2005 until 2010. But eventually, They will renew a contract of TV5 from 2013 until 2015. Although, Daniel Padilla, Alwyn Uytingco, Dominic Roco, Felix Roco, DingDong Dantes, Rocco Nacino and Enchong Dee were from TV5 since 2010. However, Daniel Padilla will sign a temporary contract from GMA in 2015 with Xian Lim.

The Christmas Station ID theme will be re-used in the 2011 Christmas Station ID from TV5 which is “Magpasaya ang Kapatid” but with minor changes and explosions. Somehow, The Christmas Station ID in 2011 will also feature Blue the Puppy from Disney’s Blues Clues saying “That’s a Spicy Meatball!”. But eventually, The line “That’s a Spicy Meatball!” will be re-used in the 2015 Summer Station ID of TV5 which is “Happy Ka Dito This Summer!”

#tv5#maligayang pasko#merry christmas#happy holidays#parasaiyokapatid#in the service of the filipino#christmas station id#magpasaya ang kapatid

1 note

·

View note

Text

This Season we appreciated all of your support and we always here to support all of you this Christmas. Mula sa amin mga CPM Bible Sharing Sqaud Family kami bumabati sa inyo ng Maligayang Pasko o Merry Christmas sa inyong lahat.

Photo and Caption by: Simon Tanjutco

0 notes

Text

Alt-talia Compilation: December Fun

Well, it’s already New Years for me. Fortunately this is the last story I want to get out since I’m delaying Key to Zorn part 2 again. Hooray. All I need to do is that alternate ending and I’m done! Goodbye 2019!

This compilation is three super short fics: December 22, 2019: Snowball fight/Skiing/Christmas without snow. The first two are for Skiing, the last one is Christmas Without Snow, though it could also be filed against “Decorations”. While admittedly the first two aren’t Christmas related, the last one is so hopefully it still counts.

Btw this is a semi-AU. I don’t have time to explain, so those unfamiliar with it, please reference my other works.

And the awful titles are especially bad this time around. And the writing quality is super rough. Still, I don’t really have much time here.

Name key: Denmark: Simon, Norway: Lukas

So without further ado, happy new year!

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

This is a message from the event holder:

I would like to ask one thing (but this isn’t part of the rules, so don’t worry) , if it is not too demanding… please, if you like someone’s work say it (comment), I personally think that put only a “heart” on it doesn’t make enough justice for the artist. I mean… as an active fan that contributes for the Hetalia’s fandom… a “heart” means nothing to me, at least reblog it. “Creators” get demotivated and sincerely it doesn’t hurt be nice to others. Of course, this is my opinion and a selfish request, so I won’t expect too much.

Please listen to them, I would really appreciate it.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Skiing Lessons

“Orv... You make it look so easy!”

Lukas seemed to glide across the snow, the boy weaving between thin trees agilely as if it took him no effort.

Simon could only admire his Union-Brother’s skills; he had to observe closely, after all.

That morning, Simon had finally decided to ask him about it; Lukas’ skiing had helped him in so many wars over the years. While Simon was considered to be part of Scandinavia, his land being as flat and close to the ocean as it was, the art of skiing was never something he had to learn; Lukas was different. On the snow, where horse hooves sunk impotently, he commanded the ski as his steed. Ever since he was very young, he had used them not only to run circles around his enemies, but as one of his companions in daily life.

“Teach you?”

“Yeah! You’re so good at it, and it’s helped us in so many wars, so… could you? Please?”

Lukas had nodded.

“Mmm. No problem. I have a few boards as spares. Though it’s not easy. I’ll warn you.”

So now, here they were, up north.

And indeed, it was much harder than it looked.

For the fifth time that day, Simon fell facefirst into the snow.

Lukas shook his head like a monk chastising a child.

“Get up!”

“I’m trying!”

“Danmark, you’re not supposed to put that much weight on your feet. You’re supposed to glide atop the snow. Don’t dig in too much. Let the snow carry you.”

“Right…”

He pushed himself along.

“Glide... Glide atop the snow...Wait... I think I’m getting the hang of it!”

Mmmm. That’s it... follow me.”

“I can do it! Look Norge, I’m doing it-“

And then he fell into the snow again.

“It’s not that easy.”

Lukas pulled him out of the snow, his Union-Brother’s face having gone pink from the coldness but still determined

“We’re doing it again.”

“Yessir!”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Alpine Rivals

Austria and Switzerland cascaded down the mountain, dodging everyone on the slope as they went with masterful skill.

The two raced neck-and neck, the freezing air whistling past, nipping their cheeks, through the hair that wasn’t tucked inside their helmets.

Italy had been close behind, but in a moment of distraction had reverted to his klutzy self; a split second which had proved disastrous, and sent him falling into the snow with his feet sticking out like a cartoon, and now he was way behind, desperately trying to catch up. Poland was a close third, wrestling his place with Bavaria, and France and Germany were a few meters behind those two. However, especially as the Nordics were taking a different course on the other side of the mountain, the undoubted champions here were Austria and Switzerland, as they long had always been.

But even if the Nordics were racing with them, it was entirely possible they would still be left in the dust. For they were the Alpine duo; the only ones who even rivaled, even surpassed, Norway himself in the ancient sport of downhill skiing.

But as usual, Switzerland seemed to be winning this time. There was a reason he had the most Alpine skiing medals in the Olympics.

Austria wasn’t giving up so easily though; when it came to skiing, his suppressed competitiveness had a rare opportunity to shine. And best friend or no, or especially because of that, it wasn’t over until the end of the slope.

He was certain that Bavaria was going to complain about it after all of this as he usually did though. His father wasn’t exactly known for being humble.

“See you at the bottom!”

“Gah! Get back here!”

Soon, the foot of the mountain came into view, flattening to soften the landing.

Almost there…

Wait, was that…

Snow flew in waves as Switzerland skidded to a halt.

“Eek!”

An extremely familiar voice squeaked.

When the snow cleared, standing there, brushing herself off, in her skis, was Liechtenstein.

“Look, look! I won! Finally! I told you I practiced!”

Switzerland raised his goggles, his jaw ajar.

“...Since when were you here?”

“About a minute ago?”

They heard the loud muffled sounds of snow crunching as Austria skidded to a stop above them.

“Österreich... It’s Liechtenstein. She won.”

“...Mein Gott. Goodness. I did know you were quite good, but…”

Her cheeky grin widened.

“I’m Alpine too, you know!”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Starry Streets of Tropical Bethlehem

Now, think of Christmas. What do you think of?

Not just the trees, the music, or even the religious elements. What is expected of the scenery outside?

Snow, of course. Without snow, Christmas just seems so incomplete.

Most of us aren’t fortunate enough to experience a white Christmas, however, there is something inseparable about these two things in our minds.

Or so it seems. For one nation, while knowing little of snow, may be one of the biggest lovers of Christmas of all.

“YEHEY! YEHEY! IT’S ALMOST CHRISTMAS!”

Others looked on in confusion as the personification of the Philippines barreled through the halls as soon as the meeting got out.

It wasn’t too long until she had crashed into America, sending papers flying everywhere.

“GAH! Whoa! Whoa! Hey, slow down!”

“I can’t wait! It’s almost Pasko!”

“Wha?”

“Christmas!”

America stared at her in confusion. South Korea was standing above, his face blank as he processed what just happened.

“...Wha? But it’s September! I swear, Christmas gets earlier every year, but I didn’t think it was this bad!”

“What do you mean, Kuya America? Of course it’s long! All my people come home on Christmas! ...Ay! There’s something I want to show everyone.”

She reached into her purse and pulled out a flyer; a clearly handmade one, with just a date, location, and absolutely nothing else.

“Come to San Fernando on the Saturday two weeks before Christmas! I’m inviting the rest of ASEAN too!”

“Wha?! What are we being invited to?!”

“It’s a surprise!”

“She always is so excited, this time of year…”

Then, she grabbed South Korea as well, thrusting the “flyer” into his hand, her dark brown eyes sparkling.

“You come too, Kuya! Please?!”

“I… I presume so…”

“Yehey! See you!”

With that, she ran off.

———————--------------------------------------------

For Philippines, Christmas started at the beginning of September in the truest sense of the word; the carols started, everyone broke out the trees, and talk of presents was fresh on everyone’s mind.

For some, this may have seemed absurd. However, even without the snow, even without many Christmas trappings, she never tired of this festive, yet sacred atmosphere which enveloped her islands for half a year.

———————--------------------------------------------

Even in the middle of December, it was warm in the Philippines.

Though everyone expected it, actually experiencing it was a bit strange for America, though Australia seemed to not notice any difference. And poor Japan looked like he was going to melt.

For some ASEAN members, those who could afford to come anyway, the festive Christmas cheer emanating from everywhere was an unusual sight in it of itself.

So many other people had already gathered around them under the San Fernando sky, mostly locals.

“So… what are you goin’ to show us, hermana?”

Philippines grinned a wide grin.

“You’ll see, Kuya Mehiko! Oh, it’s starting!”

Just as the music started, she threw open her arms.

“...NARITO! MALIGAYANG PASKO!”

And immediately, like that, as her voice boomed into the air, everything lit up.

Star-shaped, intricate fractals of light, red, orange, blue, green, yellow, white, silver, gold, big and small, arranged in beautiful designs.

They moved, spinning and dancing as they lit up the night.

A collective gasp took over them as stars lit everything in their field of vision.

“...It’s… it’s awesome!”

“See? I told you! I told you!”

And so, under a tropical urban December sky, a starry night shined brightly not above, but right on Earth.

#hetaliaxmasevent#hws denmark#aph denmark#hws norway#aph norway#hws switzerland#aph switzerland#hws austria#aph austria#hws philippines#aph philippines#hws oc#aph oc#hws america#aph america#bringbackhetalia2020#bringbackhetalia2k20

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Volontariamente emarginato da tutti festival e felicemente escluso da tutte le fiere culturali, mi estinguo tra queste mura, passo la vita recluso tra migliaia di libri…

Non amo l’aria che penetra dalla mia finestra. Solitamente chiusa. M’intimano di aprirla almeno una volta al giorno per non morire soffocato. C’è la certezza diffusa di virus sempre nuovi. In effetti gli spazi liberi, qui da me, si sono ristretti all’inverosimile. Mi estinguo tra queste mura, foglio dopo foglio. Ma i virus nella mia stanza di isolato, corazzato lettore, hanno l’apparenza ben definita di libri d’ogni specie, vecchi e nuovi, antichi e moderni. Migliaia di libri, milioni di fantasmi… Tutto ormai per me si svolge nella misura asmatica delle azioni consentite e indispensabili fra quattro nere mura.

Anche la natura, per suo conto, si adegua alla mia ricerca di solitudine nulla producendo se non un brulichio di vermi futuribili… Caldo e gelo si alternano nella fuga precipitosa delle stagioni. Amo tuttavia questa mia libertà fatta di solidi confini e di torri eburnee. Volontariamente emarginato da tutti i festival “mercatali”, felicemente escluso da tutte le fiere del libro, respiro a pieni polmoni come se fossi al centro di una pianura aspra e desolata. Nel dolce riparo degli anfratti sabbiosi, silhouette di neri cipressi orientano lo sguardo nella penombra in cui ristagno verso grigie isole di carta. Alberi furono qui un tempo a darci ombra e respiro. Oggi preziose raccolte di volumi (dai diecimila in su!), prime edizioni, libri d’arte, guide illustrate, opuscoli di propaganda politica, giacciono silenti nel buio dei tempi in attesa di partire per un viaggio senza ritorno.

Cella funebre della mia estrema zoppicante vecchiezza, sempre inappagato cacciatore di vite mancate, gli spazi pubblici e privati di questa stanza-obitorio, sono da tempo completamente assegnati e classificati. C’è l’angolo dei grandi russi e lo spazio esclusivo dei poemi omerici, c’è l’epopea delle imprese cavalleresche e lo scaffale segreto dei folli e dei suicidi, maledetti di ogni latitudine e, in ostentata evidenza, i visionari utopisti dei bei tempi andati… Oltre che a trattati di ogni genere: disattesi bollettini di pace, resoconti di guerra di varia ampiezza e misura nonché milioni di accordi segreti disposti in alterna sequenza proto e meta storica.

Nel notturno fiabesco delle mie quattro mura, ci si muove come tra mille continenti di storie universali, si procede zigzagando tra busti tombali, cippi sepolcrali e lapidi di morti prematuri. I virus hanno ceduto il passo ai fantasmi di una silente replicante Babilonia. Una volta chiusa la finestra, i racconti (a milioni!) si accalcano nel cerchio necrologico della lampada mortuaria, messaggeri misteriosi e pur pieni d’inaspettate infinite sorprese. Le antologie antiche e recenti restano rincantucciate nei loro angoli di sempre. Incallite raccolte prosaiche e poetiche, cupe e meste reliquie pentametrali, respirano a stento i lugubri effluvi del lavico sottosuolo paradigmatico. Sinfoniche melodie tradizionali si riappropriano, con fare liberticida, dei testi poetici canicolari, gloria delle antiche comunità montane. Luoghi illacrimati e personaggi corrosi da stimoli prostranti, animano la liquida scena terrestre che io solo intravedo nel riquadro epigonale della mia stratosferica finestra.

Tutto all’interno del mio capitale libresco, romanzi e trattati, dissertazioni in prosa e in poesia, tesi e relazioni, atlanti storici e geografici, ogni cartaceo discorso improduttivo convive forzatamente con lessemi e fonemi logaritmici, pandette e panegirici consapevolmente predisposti per il viaggio finale verso il putrido cuore di questa lugubre notte etimologica che è tuttora considerata vita su questa terra d’ineludibili fantasmi.

Pasko Simone

*In copertina: la Biblioteca Gambalunga di Rimini. Aperta nel 1619 ai cittadini, per lascito testamentario del suo proprietario, Alessandro Gambalunga, che nei suoi antri diceva di aver passato i momenti più belli della vita, la ‘Gambalunga’ è la più antica biblioteca civica d’Italia.

L'articolo Volontariamente emarginato da tutti festival e felicemente escluso da tutte le fiere culturali, mi estinguo tra queste mura, passo la vita recluso tra migliaia di libri… proviene da Pangea.

from pangea.news https://ift.tt/2xrQop7

0 notes

Text

so I got Simon Pegg to notice me in his livestream again by telling him to go check out Filipino Christmas songs (these are just a few omg)

1 note

·

View note

Text

10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting

TV and comic-book biographer Martin Pasko, accepted for his assignment on iconic DC curve like Superman and Daytime Emmy Award-winning about-face as biographer and adventure editor for Batman: The Animated Series as able-bodied as its affection film, Mask of the Phantasm, has died at age 65. Friend and adolescent biographer Alan Brennert aggregate in a Facebook column that Pasko anesthetized Sunday night of accustomed causes. He had been active in North Hills, CA.

SpongeBob SquarePants fan claims Nickelodeon copied art – BBC News – spongebob intro painting | spongebob intro painting

Pasko was built-in Jean-Claude Rochefort in Quebec in 1954. The ambitious biographer got a bottom in the comic-books aperture with common appearances in the letter columns of comics and in fanzines — he and Brennert alike founded their own, Fantazine. Pasko began autograph for comics in 1972, acceptable a approved contributor to DC titles including Superman, DC Comics Presents and Superman Family by 1974. He additionally bound installments of the publisher’s Justice League of America, Wonder Woman and Swamp Thing.

Continuing to assignment in comics throughout the 1980s and ’90s, Pasko added a admeasurement of TV titles to his resume — somewhat of a hit account of cornball animation. Pasko wrote or was adventure editor for Mister T, Blackstar, Thundarr the Barbarian, Goldie Gold and Action Jack, The Berenstain Bears, G.I. Joe, Moon Dreamers, My Little Pony ‘n Friends, the Superman TV shorts (“Fugitive from Space”), Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Bucky O’Hare and the Toad Wars!, The Legend of Prince Valiant, Cadillacs and Dinosaurs, Mega Man, Exosquad and, best recently, Cannon Busters (2019).

Someone Just Turned ‘Spongebob’ Into Anime, And Your Childhood .. | spongebob intro painting

Pasko was alert nominated for the Daytime Emmy for Outstanding Autograph in an Animated Program for Bruce Timm’s Batman: The Animated Series, in 1993 (when he aggregate the win with Paul Dini, Michael Reaves and Sean Catherine Derek) and in 1994. He additionally wrote the cine for the feature-length Batman: Mask of the Phantasm (1993).

His live-action biographer and adventure editor credits included The Twilight Zone, Simon & Simonand Roseanne, as able-bodied as episodes of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, The Incredible Hulk and Max Headroom.

Spongebob Squarepants – Intro (Slovak) on Vimeo – spongebob intro painting | spongebob intro painting

In the ’90s, Pasko was on agents for both the Disney Comics characterization and DC, area he was the accumulation bazaar accumulation editor and communication to Warner Bros. Studios until 2005. In this role, he consulted on the development of affected and TV projects including Birds of Prey and Smallville. As above admiral of DC Paul Levitz wrote on Facebook, “[T]he allowance are you’ve apprehend his work, accustomed or not, or enjoyed a banana or animation or TV appearance or alike a affair esplanade accident he fabricated better…”

[Source: The Hollywood Reporter]

I painted Painty the Pirate from Spongebob Squarepants! | Painting/Drawing – spongebob intro painting | spongebob intro painting

Cannon Busters

TMNT

Opening Bob esponja con paint | Doovi – spongebob intro painting | spongebob intro painting

10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting – spongebob intro painting | Welcome to be able to our weblog, on this occasion I am going to explain to you regarding keyword. And today, this is actually the initial image:

Spongebob Anime Opening | Paint Version – YouTube – spongebob intro painting | spongebob intro painting

Why not consider impression previously mentioned? is which wonderful???. if you think consequently, I’l t provide you with several impression once more under:

So, if you would like receive these great images related to (10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting), click save button to store the images in your pc. There’re prepared for save, if you’d prefer and want to get it, simply click save symbol in the page, and it’ll be instantly down loaded to your pc.} At last if you’d like to find unique and recent graphic related to (10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting), please follow us on google plus or save the site, we try our best to provide regular up grade with all new and fresh images. Hope you like keeping right here. For most upgrades and latest information about (10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting) images, please kindly follow us on tweets, path, Instagram and google plus, or you mark this page on book mark area, We attempt to give you up grade periodically with fresh and new images, like your searching, and find the ideal for you.

Here you are at our website, contentabove (10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting) published . Today we are pleased to declare that we have found an incrediblyinteresting nicheto be discussed, that is (10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting) Some people attempting to find specifics of(10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting) and certainly one of them is you, is not it?

The Spongebob Opening Theme Song – Drawception – spongebob intro painting | spongebob intro painting

Cartoon SNAP: ArtRage #6 – Painting SpongeBob, Adding .. | spongebob intro painting

The 10 Best SpongeBob SquarePants Episodes, Ranked – TV Guide – spongebob intro painting | spongebob intro painting

Spongebob Squarepants Intro Minecraft!( Half finished,will .. | spongebob intro painting

The post 10 Things You Should Do In Spongebob Intro Painting | spongebob intro painting appeared first on Wallpaper Painting.

from Wallpaper Painting https://www.bleumultimedia.com/10-things-you-should-do-in-spongebob-intro-painting-spongebob-intro-painting/

0 notes

Photo

Spoilers for comics in May!

Pretty sparse again, and it’s really just collected editions which are of interest...though Len appears on the variant cover of the Super Sons issue. I don’t think he’s in any of the stories thus far.

You can see the solicits in full at CBR.

CHALLENGE OF THE SUPER SONS #2 written by PETER J. TOMASI art by MAX RAYNOR and JORGE CORONA cover by SIMONE DI MEO card stock variant cover by NICK BRADSHAW ON SALE 5/11/21 $3.99 US | 32 PAGES | 2 of 7 | FC | DC CARD STOCK VARIANT COVER $4.99 US Okay, Robin and Superboy saved the Flash from certain annihilation...surely the day is saved and everyone can go home and watch TV, right? Wrong! Once the Doom Scroll inscribes a name on its mystical list, the bearer of that name will be imminently killed—and the heroes of the Justice League are being targeted one by one! Next up? Wonder Woman! Plus, see just what happened when the boys were snatched from reality, and how they first encountered the Doom Scroll...in medieval England?

From here, we’ve got a ton of collected editions. The Mark Waid book has some Replicant and Piper. @one-rogue-army

THE FLASH BY MARK WAID BOOK EIGHT TP written by MARK WAID, BRIAN AUGUSTYN, and JOE CASEY art by PAUL PELLETIER, DUNCAN ROULEAU, SCOTT KOLINS, DOUG BRAITHWAITE, and others cover by STEVE LIGHTLE ON SALE 6/15/21 $34.99 US | $45.99 CAN | 368 PAGES | FC | DC Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-77951-010-5 As this latest collection of Flash tales written by Mark Waid begins, meet Walter West, a Flash from a parallel reality where his beloved Linda Park died and the speedster doles out brutal justice to criminals as a response. Can the two Flashes co-exist long enough to stop Replicant, a villain with the combined powers of the Rogues Gallery? Better find out fast—the longer Walter West stays on Wally’s Earth, the more he poses a threat to all of reality! Collects The Flash #151-162, The Flash Annual #12, and pages from The Flash Secret Files #2.

This Justice League trade has a classic Eobard story, from the Secret Society of Super-Villains (he acts like a creep towards Black Canary). There’s also a good Kadabra and Sam story reprinted here.

JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA: THE BRONZE AGE OMNIBUS VOL. 3 HC written by GERRY CONWAY, PAUL LEVITZ, MARTIN PASKO, and STEVE ENGLEHART art by DICK DILLIN, GEORGE TUSKA, and others cover by KARL KERSCHL ON SALE 7/6/21 $125.00 US | $163.00 CAN | 1,192 PAGES | FC | DC Hardcover 7.0625" x 10.875" ISBN: 978-1-77951-016-7 The JLA moves into the second half of the ’70s with tales guest-starring the Justice Society of America, the Legion of Super-Heroes, and heroes from the long-gone past including Jonah Hex, the Viking Prince, Enemy Ace, and more. Plus, the League’s mascot, Snapper Carr, turns against the team, the Phantom Stranger helps the team battle a returning pantheon of ancient gods, the Martian Manhunter faces Despero for the lives of the League, and the Secret Society of Super-Villains swap bodies with the World’s Greatest Superheroes. Plus, Black Lightning is invited to join the JLA—but turns down the invitation for mysterious reasons. Collects Justice League of America #147-182, Super-Team Family #11-14, DC Special #27, DC Special Series #6, Secret Society of Super-Villains #15, DC Comics Presents #17, and pages from Amazing World of DC comics #14.

If you missed the digital releases, here’s your chance to buy this cool AU Hartley story!

DCEASED: HOPE AT WORLD’S END HC written by TOM TAYLOR art by DUSTIN NGUYEN, RENATO GUEDES, CARMINE DI GIANDOMENICO, MARCO FAILLA, KARL MOSTERT, and DANIELE DI NICUOLO cover by FRANCESCO MATTINA ON SALE 6/15/21 $24.99 US | $33.99 CAN | 176 PAGES | FC | DC HARDCOVER ISBN: 978-1-77951-128-7 In Earth’s darkest hour, heroes will bring hope in this new addition to the DCeased saga, taking place within the timeline of the original epic! DCeased became a smash horror hit in 2019 by offering a twisted version of the DC Universe infected by the Anti-Life Equation, transforming heroes and villains alike into mindless monsters. DCeased: Hope at World’s End, previously only available digitally, expands the world of that original DCeased series by filling in that story’s time jump and focusing on characters including Superman, Wonder Woman, Martian Manhunter, Stephanie Brown, Wally West, and Jimmy Olsen. In DCeased: Hope at World’s End, the Anti-Life Equation has infected over a billion people on Earth. Heroes and villains have fallen. In the immediate aftermath of the destruction of Metropolis, Superman and Wonder Woman spearhead an effort to stem the tide of infection, preserve and protect survivors, and plan for what’s next. In the Earth’s darkest hour, heroes will bring hope! The war for Earth has only just begun! This volume collects DCeased: Hope at World’s End Digital Chapters 1-15.

And this is for the AU Eobard story.

TALES FROM THE DC DARK MULTIVERSE II HC stories and art by VARIOUS cover by DAVID MARQUEZ ON SALE 6/8/21 $34.99 US | $45.99 CAN | 368 PAGES | FC | DC Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-77951-007-5 The gateway into the Dark Multiverse has been opened...what stories will emerge? Follow Batman, Wonder Woman, and the Justice League as our heroes battle their way through these crumbling and shattered worlds! Collects Tales from the Dark Multiverse: Batman: Hush #1; Tales from the Dark Multiverse: Flashpoint #1; Tales from the Dark Multiverse: Wonder Woman: War of the Gods #1; Tales from the Dark Multiverse: Crisis on Infinite Earths #1; and Tales from the Dark Multiverse: Dark Nights Metal #1, plus the stories that inspired these tales from Batman #619, Flashpoint #1, Wonder Woman: War of the Gods #4, Crisis on Infinite Earths #12, and Dark Nights: Metal #6.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gotham By Geeks ep 170 Batman: Black & White

Gotham By Geeks ep 170 Batman: Black & White

We recorded this episode prior to the passing of Marty Pasko a creator who has contributed so mch to comics but also tv and animation he shall be missed.

Detective Comics 463-464 Batman Family 17 Gerry Conway, Jim Aparo Batman Black and White World , Simon Bisley, Neil Gaiman Batman Black and White Good Evening Midnight by Klaus Janson Batman Black and White Two of a Kind by Bruce Timm Detective…

View On WordPress

#batman#Batman Black and White#Batman Black and White Good Evening Midnight#Batman Black and White World#Batman Family 17 Gerry Conway#dcuniverse#Detective comics#detective comics 439#Gerry Conway#Gotham By Geeks ep 170 Batman: Black & White#Jim Aparo#neil gaiman#Sal Amendola#Simon Bisley#Steve Engelhart

0 notes

Text

DC Yuritober Drabbles Days 1-10

by sadifura An assortment of DC Yuri Drabbles for DC Yuritober, since...I doubt my confidence in drawing said ships (especially Taelyr...I can't do Jess Taylor's art justice!!). None of these characters belong to me. Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Taylor Barzelay as well as Kat Silverberg belong to Jadzia Axelrod and Jess Taelyr, Barbara Gordon's portrayal as Oracle as well as my portrayal of Dinah Lance belongs to Gail Simone, my Bruce/Bea Wayne portrayal, although somewhat mine, belongs to Paul Dini, Alan Burnett, Martin Pasko, and Michael Reeves, as is my portrayal of Andrea Beaumont, my portrayal of Mandy Anders belongs to Mariko Tamaki, my portrayals of Cassandra Cain and Stephanie Brown are pretty much cobbled together from their best portrayals (I hope), my portrayals of Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy are a mix of Paul Dini incarnations and some others, my portrayal of Catwoman is a mix of Paul Dini and Michael J. Stern, my portrayal of Bibi and Jestah are Michael J. Stern compliant, and my portrayal of Karen Starr is consistent with Amanda Conner, Justin Gray, and Jimmy Palmiotti's version. Words: 534, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English Series: Part 1 of DC Yuritober Drabble Collection Fandoms: DC Extended Universe, Galaxy: The Prettiest Star - Jadzia Axelrod & Jess Taylor (Graphic Novel), Birds of Prey (Comics), Harley Quinn (Comics), Batman - All Media Types, Batman (Comics), Batwheels (Cartoon), I Am Not Starfire (Graphic Novel), Power Girl (Comics) Rating: Not Rated Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Categories: F/F Characters: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Taylor Barzelay, Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon, Dinah Lance, Helena Wayne, Stephanie Brown, Cassandra Cain, Bruce Wayne, Andrea Beaumont, Mandy Anders, Harleen Quinzel, Pamela Isley, Selina Kyle, Bibi (Batwheels), Jestah (Batwheels), Karen Starr | Kara Zor-L Relationships: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Kat Silverberg, Taylor Barzelay/Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon/Dinah Lance, Andrea Beaumont/Bruce Wayne, Stephanie Brown/Cassandra Cain, Mandy Anders/Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Mandy Anders/Taylor Barzelay, Pamela Isley/Selina Kyle/Harleen Quinzel, Bibi/Jestah (Batwheels), Kara Zor-El | Karen Starr | Power Girl/Harleen Quinzel/Harley Quinn Additional Tags: Trans Female Character, Trans Bruce Wayne, Trans Female Bruce Wayne/Bea Wayne, Nonhuman Characters, Alien/Human Relationships, Disabled Character, Canon Disabled Character, Drabbles, Drabble Collection, DC Yuritober, Femslash, Fluff, Fluff and Angst, Angst with a Happy Ending, Character Study, Polyamory, Established Relationship, maybe requited love via https://ift.tt/JdzGgeR

0 notes

Text

DC Yuritober Drabbles Days 1-10

by sadifura An assortment of DC Yuri Drabbles for DC Yuritober, since...I doubt my confidence in drawing said ships (especially Taelyr...I can't do Jess Taylor's art justice!!). None of these characters belong to me. Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Taylor Barzelay as well as Kat Silverberg belong to Jadzia Axelrod and Jess Taelyr, Barbara Gordon's portrayal as Oracle as well as my portrayal of Dinah Lance belongs to Gail Simone, my Bruce/Bea Wayne portrayal, although somewhat mine, belongs to Paul Dini, Alan Burnett, Martin Pasko, and Michael Reeves, as is my portrayal of Andrea Beaumont, my portrayal of Mandy Anders belongs to Mariko Tamaki, my portrayals of Cassandra Cain and Stephanie Brown are pretty much cobbled together from their best portrayals (I hope), my portrayals of Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy are a mix of Paul Dini incarnations and some others, my portrayal of Catwoman is a mix of Paul Dini and Michael J. Stern, my portrayal of Bibi and Jestah are Michael J. Stern compliant, and my portrayal of Karen Starr is consistent with Amanda Conner, Justin Gray, and Jimmy Palmiotti's version. Words: 534, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English Series: Part 1 of DC Yuritober Drabble Collection Fandoms: DC Extended Universe, Galaxy: The Prettiest Star - Jadzia Axelrod & Jess Taylor (Graphic Novel), Birds of Prey (Comics), Harley Quinn (Comics), Batman - All Media Types, Batman (Comics), Batwheels (Cartoon), I Am Not Starfire (Graphic Novel), Power Girl (Comics) Rating: Not Rated Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Categories: F/F Characters: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Taylor Barzelay, Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon, Dinah Lance, Helena Wayne, Stephanie Brown, Cassandra Cain, Bruce Wayne, Andrea Beaumont, Mandy Anders, Harleen Quinzel, Pamela Isley, Selina Kyle, Bibi (Batwheels), Jestah (Batwheels), Karen Starr | Kara Zor-L Relationships: Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai/Kat Silverberg, Taylor Barzelay/Katherine Silverberg, Barbara Gordon/Dinah Lance, Andrea Beaumont/Bruce Wayne, Stephanie Brown/Cassandra Cain, Mandy Anders/Taelyr Ilextrix-spiir Biarxiiai, Mandy Anders/Taylor Barzelay, Pamela Isley/Selina Kyle/Harleen Quinzel, Bibi/Jestah (Batwheels), Kara Zor-El | Karen Starr | Power Girl/Harleen Quinzel/Harley Quinn Additional Tags: Trans Female Character, Trans Bruce Wayne, Trans Female Bruce Wayne/Bea Wayne, Nonhuman Characters, Alien/Human Relationships, Disabled Character, Canon Disabled Character, Drabbles, Drabble Collection, DC Yuritober, Femslash, Fluff, Fluff and Angst, Angst with a Happy Ending, Character Study, Polyamory, Established Relationship, maybe requited love via https://ift.tt/wv82ygB

0 notes

Text

#KuyaRexdelsChristmasPlaylist: MaGMAhalan Tayo Ngayong Pasko

Another Christmas SID focusing on “Love” is this unique catchy tune by Alden Richards, the 1/2 of the AlDub duo that made 2015 a mammoth year for the dynamic duo that trended worldwide. The lyrics were astonishing and even meaningful because of the central theme itself, more on Love in all aspects for the season. That’s why GMA Network did this Christmas SID as a way of giving back to the Kapuso audience why they’re undisputed No. 1 in the AGB-Nielsen surveys.

Here is the official Christmas SID that the network did so, with a stellar lineup of Kapuso stars and News personalities:

youtube

And the recording/lyrics video launched weeks before the actual Christmas SID:

youtube

Courtesy of GMA Records/Single available on Spotify/Lyrics by: BJ Camaya & Clare Yee/Music arranged by: Simon Tan

0 notes

Text

“Non abbandonare la cura con cui regoli il tuo cuore su queste tenerezze parenti dell’autunno”: intorno a una poesia di René Char (in traduzione d’eccellenza, introvabile)

La poesia che riproduco è tratta da Le Poème pulvérisé, pubblicato in edizione d’arte, con “una incisione di Matisse”, nel 1947. L’anno prima Gallimard edita Feuillets d’Hypnos, l’anno dopo Fureur et Mystère. Dopo l’ipnosi della lotta, in cui René Char indossa il nome di “Capitaine Alexandre” – Alessandro, protettore di uomini – e prima del furore impregnato di mistero, la polverizzazione. Char – degno nipote di Rimbaud – sa che la scrittura scortica fino all’ultimo, non arretra agli orrori, fino al grido primo, alla purezza insopportabile. Sa che si scrive per strapparsi la lingua e convertire il sangue in luce.

*

Si polverizza il canto perché dalle ceneri sorga una parola nuova, che dia natura e nitore all’alba del prossimo millennio. Char, in quel grumo di anni, conosce Camus e Braque, divorzia dalla moglie, Georgette Goldstein, si unisce all’antropologa Tina Jolas, instaura una frugale asperità nel dire, assurge alla sorgente della solitudine. Se la poesia va scovata, scavando a perpendicolo tra la petraia delle civiltà sepolte e la fiumana dei futuri, il poeta è creatura da pretendere, da predare nella giungla, nella giuncaia dei sensi. Di René Char molto si dice – troppo poco si pubblica. Capisco: educarsi alla luce significa non accettare altra cecità.

*

Vent’anni fa, nel 1999, Palomard esce con una silloge di Poesie di Char. Non dico l’assurdo dicendo che la traduzione di Pasko Simone e più bella di quelle – bellissime per altro modo, per l’incontro con il poeta – di Vittorio Sereni e di Giorgio Caproni. Il libro mi è stato donato, e diventa verbo da masticare appena svegli, quando la finestra che sfoga in azzurro mi abbaglia, e così il suono delle nuvole. Mastichi quel verbo che non ha bisogno di meditazione ma di tocco – la poesia non si ‘comprende’, si assedia – e il seguire delle ore – “la stregoneria della clessidra”, dice Char – è sequela giustificata, sguainata. Un libro introvabile, forse, per questo, un dono memorabile, di insopprimibile bellezza.

*

“Tradurre Char vuol dire amarlo. La pazienza, la dedizione, la passione non possono essere che quelle di un amante eccezionalmente felice perché corrisposto in ogni sua aspettativa”, scrive Pasko Simone. La traduzione di Char è compito liturgico, anche la lettura è ingresso in un luogo, in una dimora. Le parole fanno questo: aprono una dimora, una città rifugio.

*

Penso che bastino le parole giuste per convertire un destino dal terrore all’amore del buio e di tutte le sue tigri. Le parole agiscono come mute di cani e statura d’abete. Se la parola assertiva carcera quella poetica apre, turba per eccesso di possibilità, ti scaglia alla pianura sterminata, al sauro senza briglie.

*

Dare peso alla notte – leggeri – e poi disfarsi, signoreggiare sull’impossibile, essere i contadini del proprio abisso, “ma tu hai scavato negli occhi del leone” – per dissotterrare quale speranza?, quale acuminata promessa? René Char ci insegna a non obliare il dolore, che è la nostra identità, ma a curarlo, come la cosa cara, lo sgomento che conforta. Si spartisce la morte dopo l’amore, dissi, perché l’amore sia un patto, il più forte. (d.b.)

***

Abito un dolore

Non abbandonare la cura con cui regoli il tuo cuore su queste tenerezze parenti dell’autunno, di cui ricalcano la placida andatura e l’affabile agonia. L’occhio è precoce nel piegarsi. La sofferenza conosce poche parole. Preferisci coricarti senza pesi: sognerai dell’indomani e il letto ti sarà leggero. Sognerei che la tua casa non ha più vetri. Impaziente di unirti al vento, al vento che percorre un anno in una sola notte. Altri canteranno l’incorporante melodia, le carni che non rappresentano altro che la stregoneria della clessidra. Tu condannerai la gratitudine che si ripete. Più tardi, sarai identificato con qualche gigante in disfacimento, signore dell’impossibile.

E tuttavia

Non hai fatto altro che dare più peso alla tua notte. Sei tornato alla pesca alle murate, alla canicola senza estate. Sei furioso verso il tuo amore, nel centro di un’intesa che sgomenta. Pensa alla casa perfetta che non vedrai mai innalzata. A quando la raccolta dell’abisso? Ma tu hai scavato negli occhi del leone. Tu credi di veder passare la bellezza al di sopra delle nere lavande…

Che cosa ti ha sollevato, ancora una volta, un po’ più in alto senza convincerti?

Non esiste pura dimora.

René Char

*da: René Char, “Poesie”, Palomar 1999, traduzione italiana di Pasko Simone

L'articolo “Non abbandonare la cura con cui regoli il tuo cuore su queste tenerezze parenti dell’autunno”: intorno a una poesia di René Char (in traduzione d’eccellenza, introvabile) proviene da Pangea.

from pangea.news http://bit.ly/2WujqDd

0 notes