#National Gallery in London

Video

undefined

tumblr

Just Stop Oil Protesters Throw Soup on Van Gogh's Sunflowers Painting

Just Stop Oil activists have thrown Heinz tomato soup over Vincent Van Gogh's masterpiece 'Sunflowers' at the National Gallery in London.

The protestors, wearing Just Stop Oil T-shirts, threw two tins of Heinz Tomato soup over the 1888 work - estimated to be worth £76 million - shortly after 11am today before kneeling down in front of the painting and appearing to glue their hands to the wall beneath it

Visitors were then shortly escorted out by security, who then shut the doors to room 43 of the gallery where the painting hangs.

After throwing soup on the painting - which has a glass cover - protestor Phoebe Plummer, 21, yelled: 'What is worth more, art or life? Is it worth more than food? More than justice? Are you more concerned about the protection of a painting, or the protection of our planet and people?

'The cost of living crisis is part of the cost of oil crisis.'

The National Gallery has confirmed that the painting was unharmed apart from 'minor damage' to the frame.

The Met Police said that both Just Stop Oil protesters have been arrested for criminal damage and aggravated trespass, and officers were working to 'de-bond' them.

Art historian Ruth Millington said: 'I think that attacking one of the world's most loved paintings, which I would call priceless, will not gain these protestors public support. That is what which they need in order to effect real change.

'What has happened today provides a perfect example of why the painting is protected by glass, luckily.'

Activist Anna Holland, 20, from Newcastle said: 'UK families will be forced to choose between heating or eating this winter, as fossil fuel companies reap record profits.

'But the cost of oil and gas isn't limited to our bills. Somalia is now facing an apocalyptic famine, caused by drought and fuelled by the climate crisis.

'Millions are being forced to move and tens of thousands face starvation. This is the future we choose for ourselves if we push for new oil and gas.'

The demonstrators were surrounded by a group of photographers and journalists when they attacked the painting, before the press were asked to leave by National Gallery Staff.

Police were called shortly afterwards to un-glue the climate activists from the wall of the National Gallery and arrested two people for criminal damage.

A National Gallery spokesman said: 'At just after 11am this morning two people entered Room 43 of the National Gallery. The pair appeared to glue themselves to the wall adjacent to Van Gogh's 'Sunflowers' (1888). They also threw a red substance - what appears to be tomato soup - over the painting.

'The room was cleared of visitors and police were called. Officers are now on the scene. There is some minor damage to the frame but the painting is unharmed.

'Two people have been arrested.'

In a tweet from the Metropolitan Police Events account, the force said: 'Officers were rapidly on scene at the National Gallery this morning after two Just Stop Oil protesters threw a substance over a painting and then glued themselves to a wall.

'Both have been arrested for criminal damage & aggravated trespass. Officers are now de-bonding them.'

#Just Stop Oil Protesters Throw Soup on Van Gogh's Sunflowers Painting#Vincent Van Gough#Just Stop Oil activists#National Gallery in London#art#artist#art work#art world#art news

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

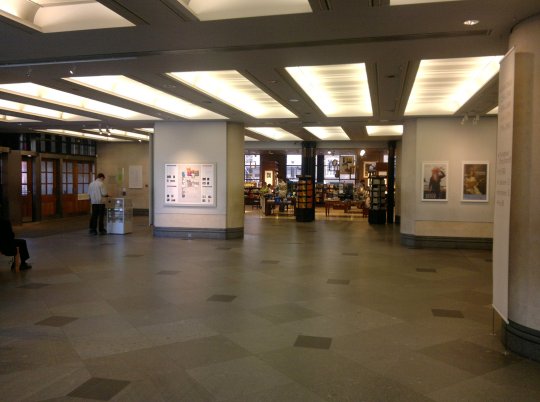

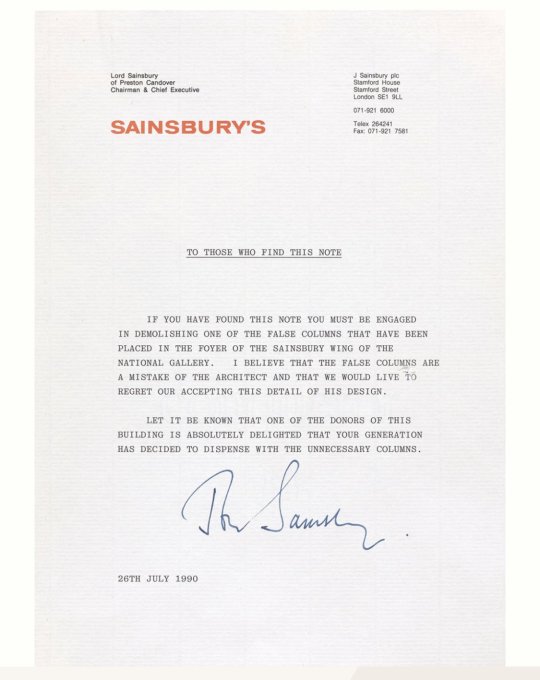

Meanwhile, in London...

Via @oldenoughtosay over at the Ex Bird Place:

"The National Gallery in London is renovating its Sainsbury Wing and they’ve just found a secret letter from one of the original donors, sunk into a concrete column, saying that he hates the columns and is glad they’re being demolished. 10/10 unhinged rich man behaviour, no notes"

Here are the columns...

And here's the letter.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Judith, (detail), (ca.1678) by Eglon Hendrik van der Neer (1634–1703), oil on oak, 32 × 24.6 cm, The National Gallery, London

#judith#judith and holofernes#eglon hendrik van de neer#painting#detail#historiated painting#art#fine art#national gallery#london#oil on oak#woman with sword#portrait#my upload

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Water-Lily Pond (1899)

🎨 Claude Monet

🏛️ The National Gallery

📍 London, United Kingdom

For Monet, gardens offered a refuge from the modern urban and industrial world, although he and his fellow garden enthusiasts benefited from modern advances in botanical science that were creating new hybrid flowers in a wide choice of shapes and colours that could be produced on an almost industrial scale. He made modest gardens in the homes he rented in Argenteuil and Vetheuil in the 1870s, but from 1883, when he moved to a rented house in Giverny, about 50 miles to the west of Paris, he had more scope to indulge his passion for plants. He became a dedicated gardener with an extensive botanical knowledge, and sought the opinions of leading horticulturalists. As Monet’s career flourished his increasing wealth enabled him to fund what became a grand horticultural enterprise: by the 1890s he was employing as many as eight gardeners.

Monet began by refashioning the garden in front of the house, the so-called ‘Clos Normand’, replacing the existing kitchen garden and orchard with densely planted colourful flower beds that were filled with blooms throughout the seasons. He was able to buy the house in 1890, and three years later he purchased an adjacent plot of land next to the river Epte beyond the railway line at the edge of his property. The plot had a small pond with arrowhead and wild water lilies, which he wanted to turn into a water garden with a larger lily pond ‘both for the pleasure of the eye and for the purpose of having subjects to paint’.

The idea may have occurred to him after he had seen the water garden at the 1899 Exposition Universelle in Paris created by the grower Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac, who bred the first colourful hardy waterlilies. Monet began by requesting permission from the Prefect of the Eure to dig irrigation channels from the Ru – a branch of the Epte – to feed his pond, but the Giverny villagers objected, fearing it would contaminate the water and that the foreign plants would poison their cattle. Monet was furious, but three months later permission came through and he began to enlarge the existing pond, replacing the wild water lilies with Latour-Marliac hybrids available in yellows, pinks, whites and violets.

The pond was enlarged on further occasions – in 1901 and 1904 – tripling the size of the water garden. Together with the flower garden on the other side of the railway track it became the principal preoccupation of the last 26 years of Monet’s life. While the Clos Normand garden was laid out along fairly traditional lines, harking back to the formal French gardens of seventeenth-century Europe, with a central alleyway and geometrically arranged beds, the water garden was more Eastern in inspiration. Its less regimented, more natural design and more muted colours created a quieter, meditative atmosphere. Monet erected a Japanese bridge over the western end of the pond that took its inspiration from the bridges in ukiyo-e Japanese prints. He was a keen collector of these prints and he owned a copy of Hiroshige’s Wisteria at Kameido Tenjin Shrine (1856), one of the many prints that features a curved bridge. In a more general sense, the water garden reflected Monet’s admiration for the Japanese appreciation of nature.

Monet had to wait for his water garden to mature before he could begin to paint it in earnest. As he later recalled: ‘It took me some time to understand my water-lilies. It takes more than a day to get under your skin. And then all at once, I had the revelation – how wonderful my pond was – and reached for my palette. I’ve hardly had any other subject since that moment.’ In total, Monet painted 250 canvases of his water garden. Around 200 of these represent water lilies floating on the surface of the water, while the remainder also show the Japanese bridge, the weeping willow trees and wisteria and the irises, agapanthus and day lilies on its banks. In all these pictures Monet was painting a subject that was already ‘pictorial’ – a landscape that had been carefully composed according to his personal aesthetic. The National Gallery has three further paintings of the water garden :Water-lilies, setting sun; Irises; and Water-lilies.

Monet painted three views of the Japanese bridge in 1895, not long after it had been constructed, but then took a break from the subject, only returning to it in 1899. By now the pool was overhung by vegetation and surrounded by plants, but to judge from contemporary photographs it was never as enclosed as Monet painted it, and he exaggerated the feeling of claustrophobia. In December 1900 he exhibited 12 paintings at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in Paris, all of which showed more or less symmetrical views of the Japanese bridge.

In this painting, as in the others in the series, we are looking down onto the surface of the water, where the lily pads float into the distance, meeting the dense foliage on the far bank. Weeping willows are reflected in the pond and clumps of iris border its banks. The perspective seems to shift so that it is hard to find a single focal point; it is as though we are looking up at the bridge but down on the waterlilies. The picture, like the water itself, seems to oscillate between surface and depth. The mainly vertical reflections provide a counterpoint to the horizontal clumps of the lily pads. Different colours, applied with thick brushstrokes, are placed next to each other. This way of painting has more in common with Monet’s early Impressionist works than his more recent paintings of mornings on the Seine, where he had used softer, more blended strokes to convey hazy atmospheric effects.

The Japanese bridge series marked a turning point in Monet’s art. From now on his subjects were painted from an increasingly confined viewpoint, conveying the sense of an enclosed world. In later paintings of the pond, he would dispense with the banks and bridge altogether to focus solely on the water, the reflections and the water lilies. The culmination of Monet’s water lily paintings were the Grandes Dėcorations, 22 enormous canvases each over two metres high and totalling more than 90 metres in length, which he completed months before his death and donated to the French state. These are now on permanent display in two oval rooms in the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris.

#The Water-Lily Pond#1899#Claude Monet#The National Gallery#London#United Kingdom#oil painting#painting#oil on canvas#Modern art#Impressionism#french#art#artwork#art history

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

A nymph by a stream, 1869–70, National Gallery, London - by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841 - 1919), French

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Narcissus, variously attributed to Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio or a follower (Gian Giacomo Caprotti?), ca. 1490

#art#art history#Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio#Gian Giacomo Caprotti#classical mythology#mythological painting#Narcissus#imaginary portrait#Renaissance#Renaissance art#Italian Renaissance#Quattrocento#Italian art#15th century art#oil on canvas#National Gallery#National Gallery London

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, Queen-consort of the United Kingdom (c. 1831) by William Beechey. National Portrait Gallery.

#adelaide of saxe-meiningen#william beechey#national portrait gallery#london#british royal family#oil on canvas#oil painting#painting#genre painting#art#artwork#female portrait#female portrayal#portraiture#women in art#nobility#german royalty#german royals#deutsche geschichte#saxe-meiningen#thüringen#thuringia#princess#queen#19th century art#19th century fashion#19th century#1831#1830s#1830s fashion

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

A museum is a place where one should lose one's head.

-- Renzo Piano

(London)

#museum#national gallery#lost#renzo piano#travel photography#london#uk#england#quote#art#gallery#lose yourself

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge attends the Portrait Gala 2017 at the National Portrait Gallery on March 28, 2017 in London, England.

#kate middleton#catherine duchess of cambridge#national portrait gallery#2017#temperley london#green lace#royal fashion#british royal family#royal style#british royal fandom#royal family#british royalty

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo | An Allegory with Venus and Time | NG6387

#mine#Giovanni Battista Tiepolo#art#art gallery#fine art#art history#artwork#painting#18th century#18th century art#london#national gallery london

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favourite photo of John at the Eyes of the Storm exhibition:

And my favourite quote:

»This shot of John with his guitar: that's how we worked and that's how I knew him. Looking back at it, they're so special for me because they're like family snapshots.«

#it was so lovely#eyes of the storm#paul mccartney#john lennon#the beatles#london#national portrait gallery

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510)

Portrait of a Young Man, 1480-5

Tempera and oil on wood, 37.5 × 28.3 cm

#sandro botticelli#botticelli#fine art#art#artwork#paintings#artists on tumblr#painting#artist#national gallery london#renaissance#renaissance art#italian renaissance#tempera painting#oil on panel#portrait painting#portraits#portrait#art history#art on tumblr#art of the day#florence#antique painting#old master painting#Firenze#italian painter#italian artist#italian art

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833), (detail), by Paul Delaroche (French, 1797-1856), oil on canvas, 246 cm × 297 cm, The National Gallery, London

#the execution of lady jane grey#paul delaroche#my upload#19th century#painting#painting detail#detail#oil on canvas#national gallery london#national gallery#london#lady jane grey#nine days’ queen#tableau vivant#historical painting#art#fine art

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)

🎨 Jan van Eyck

🏛️ The National Gallery

📍 London, United Kingdom

This must be one of the most famous and intriguing paintings in the world. A richly dressed man and woman stand in a private room. They are probably Giovanni di Nicolao di Arnolfini, an Italian merchant working in Bruges, and his wife.

Although the room is totally plausible – as if Jan van Eyck had simply removed a wall – close examination reveals inconsistencies: there’s not enough space for the chandelier, and no sign of a fireplace. Moreover, every object has been carefully chosen to proclaim the couple’s wealth and social status without risking criticism for aping the aristocracy.

The man’s hand is raised, apparently in greeting. On the back wall, a large convex mirror reflects two men coming into the room, one of whom also raises his arm. Immediately above it is Van Eyck’s signature. Could the man in mirror be van Eyck himself, with his servant, coming on a visit?

#The Arnolfini Portrait#Jan van Eyck#1434#The National Gallery#London#United Kingdom#Northern Renaissance#Renaissance#Arnolfini#art#artwork#art history#painting#oil painting#oil on panel#portrait#oil on oak panel#flemish

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vincent Van Gogh | Two Crabs | 1889 | London National Gallery

"After his release from hospital in Arles in January 1889, Van Gogh embarked on a series of still lifes, including crab studies. This painting may show the same crab upright and on its back. Parallel strokes sculpt the creature's form on an exuberant sea-like surface."

#Vincent Van Gogh#two crabs#london#national gallery#uk#dutch#the netherlands#green#post impressionism#neo impressionism#crabs

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Road to Emmaus, Altobello Melone, ca. 1516-17

#art#art history#Altobello Melone#religious art#Biblical art#Christian art#Christianity#Catholicism#New Testament#Gospels#Road to Emmaus#Renaissance#Renaissance art#Italian Renaissance#Mannerism#Mannerist art#Italian Mannerism#Cinquecento#Italian art#16th century art#oil on panel#National Gallery#National Gallery London

91 notes

·

View notes