#Narratology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

no one cares but a character dying is not the same as a character haunting the narrative. dying is a plot point, while haunting must be structural redefinition of the entire piece's form. it's why haunting of hill house begins and ends with the same line. it's why cassandra tells the audience of the oresteia exactly what is going to happen. they are defined by their endings- something that not all deaths lead to

#the foxhole court#lake mungo#the oresteia#jet atla#haunting the narrative#literary theory#haunting of hill house#like id argue that seth from tfc and jet are key examples of characters who die but like. dont necessarily matter to the STRUCTURE#the overall story does not differ whether they live or not#n mary hatford impacts the story through grief but it doesnt change the actual structural form of the narrative#doesnt mean they arent impactful deaths; just that haunting is different#the latter of which caused this thought#narratology

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Workshop Week 4:

A Narrative Imperative

My dearest Tumblrinas—

Sadly we’ve come to our final week of workshop, but I’ve saved the best for last. Rather, I’ve saved my favorite for last. This week’s prompt is one I’ve taught in every class, from developmental composition to advanced creative writing courses. In the hundreds of fills I’ve read over the years, I haven’t found one that has been poorly written or uninteresting. This prompt tends to bring out the fire in everyone, and I’m jazzed to see what you do with it.

Last week we talked about setting as a function of narration. This week we’re talking about narration as a function of…nothing.

The reason I say narration is the function of nothing is because you can strip a piece of writing of every craft element—conflict, character, imagery, etc.—and you’ll still have narration. Even emails have narrators. A narrator is simply the acknowledgement of a mind behind the writing, the vehicle of comprehension.

Click through for this week's workshop and prompt:

Point of View

So many people know what a point of view is that we often see it as the acronym POV. It’s so commonplace that it’s almost difficult to pin down, but the definition we’ll use for the purpose of this workshop is the relationship of the narrator to the events of the story.

In contemporary writing, the narrator is generally limited to a single character who exists in the narrative. This is called a homodiegetic narrator. A heterodiegetic narrator is one that is not a character in the story. For example, fairy tales often have a heterodiegetic narrator, a disembodied voice that’s telling you the story as if speaking it aloud.

It’s only in the past century or so that we’ve seen a shift into the limited homodiegetic narrator as a kind of default technique. In fact there are some writers (and writing teachers, sadly) who are so dedicated to this style of narration that they consider any work that deviates from it “bad writing.”

When we talk about limited narrators, we’re talking about narratorial access. In the mind of a single character in the story, we don’t have access to the minds of the other characters. Access is what creates an unreliable narrator—a character whose perspective of the external events of the story is in some way distorted, either in the literal facts of the events themselves, or in the interpretation to those events. An unreliable narrator is one who might lie in order to persuade us their actions are justified, or perhaps they struggle to perceive reality clearly.

Access also refers to how close we are to the narrator. How much access does the reader have to the true thoughts and emotions of the character we’re following? Back in Week 1, we talked about “show, don’t tell,” and if you abide by that rule to an extreme, you get a narrator who offers us little to no access to their perspective. Conversely, we can be so close to a narrator that we only have access to their thoughts and we lose sight of the external events of the story completely. (More on that in the Point of Method section.)

It’s possible that we could have access to multiple perspectives of the story, either by alternating limited perspectives or creating omniscience. The difficulty of omniscience, which is sometimes derogatorily called head-hopping, is that you’re tasked with infinite access. In Week 3, we talked about decision fatigue. Omniscience requires deciding constantly what information is given when and by whom and why. It’s exhausting. I don’t want to deter you from omniscience if that’s what you’re interested in writing, but I do think it’s more difficult than limited narration. When people refer to “head-hopping,” they’re usually saying the shifting access of the narrator is hard to follow or illogical. Your work, of course, is allowed to be hard to follow and illogical. No one is obligated to clarity. But if clarity is one of your goals as a writer, know that omniscience is often more obfuscating than illuminating.

Point of Telling

Put simply, a narrative is a sequence of cause and effect. Thing A happens, and because of it, thing B happens. Because thing B happened, thing C then happens. The sequence doesn’t have to occur in order or chronologically. However, all narratives possess an order and a chronology. In other words, all narratives exist in time and space.

We talked about space last week. So let’s talk about time.

Unlike point of view, the point of telling is the relationship of the narrator to the timeline of the story. Here’s where things get confusing, because English has tenses, but in prose, past tense doesn’t always denote the actual past. You can write a story in past tense that doesn’t have an implied present. You can also write a story in present tense and give the narrator access to the future of the story via some kind of narrative magic or prophecy. So when we talk about point of telling, grammatical tense is irrelevant.

Currently the default of contemporary writing is to have a narrator who is experiencing the events of the story as they’re happening, which means they have access to their past but not their future, and their development unfolds accordingly. A narrator who has no access to their future is one who is limited to the biases of the present.

However, you can also have a reflective narrator—one whose point of telling is the present and they’re reflecting on the past. Backstories and flashbacks can be reflective. Frame stories can also be reflective. What’s unique about the reflective narrator is that they have access to all the events of the story, and are unfolding them in a specific sequence, rendering them from the position of growth they’ve achieved from living those events. You can do cool foreshadowing stuff with a reflective narrator, like, “What I didn’t yet know was…” or “I would go on to believe that…”

To me, point of telling becomes clearest when you have a child narrator. A child telling the present would possess a childlike narrative voice, but an adult character reflecting on childhood would have an adult narrative voice. The events of the story are the same, but the point on the timeline from which those events are told can vary, and therefore so can the voice.

Point of Method

Point of view is ubiquitous; I can’t remember where I first heard of point of telling; but point of method is a term Percy Lubbock defines in his book The Craft of Fiction. The point of method is the relationship of the narrator to the rendering of the story. Lubbock separates point of method by pictorial and dramatic, arguably the beginning of the adage “show, don’t tell” that we talked about in Week 1. A pictorial method is one that renders or “shows” a story; a dramatic one is one that “tells” a story. But The Craft of Fiction was first published a century ago and narration has changed a lot since then, so I’m going to offer some other ways of defining point of method.

Although it’s a false binary, I like to think of point of method as “in scene” or “in summary.” Screenplays are beholden to scenes—film is a visual medium and so it’s limited to what literally can be shown. In its simplest form, a scene is a discrete section of a story where a character interacts with their environment in some way. A scene is often portrayed in direct discourse, which means free and clear access to the actual dialogue the characters are speaking. In other words, we can trust the words in quotes to be what is really said—not an interpretation, summation, or distortion of what is said.

Many writers I work with develop a block when they pigeonhole themselves into scenic writing. Fanfiction is largely written in direct discourse and relies on sequences of scenes, I suspect because a lot of fics are based on canonical texts of visual mediums. When I point out that fanfiction is prose and can therefore access the interior thoughts and perspectives of a narrator, I think it can be pretty freeing for some writers. In prose, scenes are optional.

On the opposite side of the scenic spectrum is summative writing. Writing in summary is kind of a zooming out of the narration, where events are rendered in a single paragraph or sentence. Summary can evoke indirect discourse, or interaction between characters conveyed within the narration. For example, “‘I’m sorry I rang the doorbell,’ she said” is direct discourse. “She said she was sorry she rang the doorbell” is indirect discourse.

It’s important to remember that all narration is a negotiation of the internal and the external, or what I call interiority and exteriority. Interiority encompasses all thoughts, feelings, and interpretations of a narrator. Exteriority includes everything outside the narrator. “She heard the doorbell ring” is an interior sentence. “Someone rang the doorbell” is an exterior one.

Scenic writing is not inherently superior to summative writing. Direct discourse is not inherently superior to indirect discourse. Exteriority is not inherently superior to interiority. They’re all just spectrums, and you get to define where your narrator lands on each of them.

This was a lot of vocab to throw at you. I’d like to offer a brief caveat that many of these terms are narratological, intended for criticism and interpretation of existing work, but I’m appropriating them as craft terms. To me, craft is the process of writing, and creating a lexicon of craft terms (ideally) helps us as writers to make more intentional decisions in our work and approach it with more confidence.

Prompt time!

Although I’ve just told you about narration in relation to a sequence of events, we’re going to strip our writing of a formal narrative in order to focus solely on narration.

First, I’d like you to read/listen to Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl.” (It’s short, about 700 words.) You can find it here, or you can watch Jamaica Kincaid read it on YouTube.

youtube

What I love about this piece is that it’s not technically a narrative, it’s a lyric essay with not one but two narrators. There’s the voice giving the orders, the series of imperative sentences, and there’s the italicized voice questioning the orders. So even though we’re not given a discrete scene or bodies moving and interacting in space and time, we still have two characters: a mother, presumably, and her daughter. The mother is teaching the daughter the “rules” of womanhood, which are contradictory and overwhelming.

In lacking a narrative, this piece allows us to separate it from our understanding of writing grounded in time and space. In essence, it’s the opposite of last week’s prompt. It also questions our understanding of sentences in English requiring subjects, because all imperative sentences have an implied subject: you. This prompt is an experiment in how voice and style develops narration.

Next, I want you to write a piece in the imperative style of “Girl.” Here are some ways you can approach it:

If you want to write fiction, write a piece about the rules your character lives by. Consider how they feel about those rules—do they follow them or defy them? Consider also who is giving the rules and why. Is there someone who has power over them? Or perhaps they’re rules they tell themselves, that they’ve developed over time.

If you want to write nonfiction, write your own version of “Girl” using the rules you’ve been taught regarding some aspect of your life. Like “Girl,” you could focus on the rules of gender and culture, or perhaps you could take a more literal spin on it—the expectations of a job or a sport.

If you want to write something experimental (even though this is already experimental), write a version of “Girl” from the italicized voice’s perspective, perhaps a series of questions rather than commands.

A second voice within the piece is optional. And because this prompt is already lyrical, I don’t think I need to list a separate approach for poetry.

Bonus prompt

If you’ve filled any of the prompts these past four weeks, I would love to know what your biggest takeaways have been. What new insights have you gained about your own writing? Have any of your perspectives or goals changed as a writer? Feel free to sit on this one for a while; I know that it takes a long time for me to reflect on the things I’ve learned. So I welcome you to send me an ask or tag me in a post at any point in the future. My favorite thing is when writers update me on their progress and growth.

In parting, I want to share my lowkey writing-related newsletter, in which I write about craft and process as well as offer a roundup of all the writing advice asks I answer on my Tumblr. I also provide updates on the Fanauthor Workshop (currently accepting applications!) and OFIC Magazine. If you’re pleased with any of your prompt fills from our workshop, you’re welcome to submit them (or any other original work) to OFIC. Submissions for Issue #8 open September 1st.

Lastly, if you’re interested in one-on-one guidance and feedback on your writing, I’m a full-time writing coach. I help writers at all levels reach their goals, whether that’s completing a novel, querying agents, or applying to creative writing graduate programs. Here are some testimonials from current clients.

A huge thanks to @books for hosting these workshops! I hope they’ve been as fun for you as they have for me. I’ve had a great time reading your prompt fills, and I wish you the best of luck in your writing journey.

Questions? Ask ‘em here before EOD Tuesday so @bettsfic can answer them on Wednesday. And remember to tag your work #tumblr writing workshop with betts if you want her to read your work and possibly feature it on Friday!

And, for those just joining us: @bettsfic has been running a writing workshop on @books this month. These prompts will stay up for you to fill at your leisure. Want to know more? Start here.

#tumblr writing workshop with betts#week 4: a narrative imperative#writers' room#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writing advice#narratology#writing prompt#writing ideas#writing exercise#long post#long text post#Youtube

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pilgrimage and the Lands of Lothric: The Medieval Narrative in Dark Souls III

Here is the essay that got me started on my route of video game studies and digital media. I was taking a class with a medievalist professor that was talking about the ways that medieval themes and thoughts are still prevalent in the world today. She is a huge soulsborne fan so when I pitched this idea she was super into it, with this essay going on to become my grad school application essay. I hope you enjoy it!

Pilgrimage and the Lands of Lothric: The Medieval Narrative in Dark Souls III

I. Introduction

Dark Souls III is, although frequently lauded, a very opaque narrative. Little of the narrative is told to the player at any point during the thirty to forty hours of grindingly difficult roleplaying game action and adventure. What little bits of story are present, however, are delivered from sought out sources, such as non-player characters (NPCs), items descriptions, and flavor text throughout the game world, as well as inferences from the dilapidated kingdom of Lothric that the player gets to explore on their quest to “link the fire” on behalf of one of the few more friendly characters that they come across during their time in the game. In this paper I am going to summarize the general overview of the story of Dark Souls III and show that it is a modern analogue to the pilgrimage practices of the Middle Ages. In doing so, this paper strives to shed some light into the abyss that is the in-game lore plotted so masterfully by FromSoftware, the studio behind the Souls series.

II. Background

Opening up with a cinematic, Dark Souls III lays out the four bosses that the player must fight, explaining that, “In venturing north, the pilgrims discover the truth of the old words. / ‘The fire fades, and the lords go without thrones,’” [1] as part of the sixteen lines that accompany the showcase of the world and bosses before the game actually starts (Dark Souls III). From here, the game does not volunteer much other information, aside from brief sections of dialogue when interacting with the NPCs that are necessary for game progression.

As to set a baseline to draw from, then, here is a manual explanation of the main events of the game and its world: Dark Souls III cast the player as “the unkindled one,” an undead being who is awoken in response to the fading of the light of the world in order to restore, “link,” the flame and continue the current in-world epoch, the Age of Fire (Dark Souls III). Along the way, the player is tested in several environments that are central to the narrative, as FromSoftware relies heavily on the environment to form the majority of its storytelling, each of which is usually completed with the defeat of one of the games many bosses. Four of these such bosses, which the player must seek out, are called the Lords of Cinder, each of which has abandoned their duty to continue the light of the world, and therefore must be fought and their cinders brought back to rekindle the first flame. Once that is finished, the player is given a few choices based on their actions in the game in a kind of moral choice ultimately; do you link the fire, continuing the age limping along, extinguish the fire and let the next age of humanity begin, or do you usurp the fire and become a god yourself?

The world of Lothric itself begins in a sort of high citadel, The High Wall of Lothric, before the player descends into the dilapidated lands of the Undead Settlement, Road of Sacrifices, and Farron Keep and its swamp, all of which have a sort of overgrown, crumbling aesthetic of a tightly packed and mountain-locked countryside. From there, however, the player wanders through the ruined underground of the Catacombs of Carthus, a winding tunnel that eventually leads to the societies of old and the mythic city of Irithyll of the Boreal Valley and Anor Londo, where the old gods once lived. Lastly, the player descends into the depths again in search of the Profaned Capital, before returning to Lothric Castle to face off against the rulers of the land themselves, the twin princes Lothric and Lorian. The entire movement of the game is based on looping back to places that are familiar and making shortcuts between places that are safe to get quickly through dangerous areas that would otherwise be tedious and difficult to pass through separately. This whole journey is punctuated by bonfires, checkpoints where the player gets the chance to rest and level up and do all the other things that are central to gameplay mechanics. One of the most vital being the recovery of what the game calls “Estus Flasks” but are essentially healing items that hopefully keep the player from getting killed and having to reset to the last bonfire they visited (Dark Souls III).

More specifically, the world of Lothric is intentionally meant to be oppressive as the player makes their way through the course of the game. The landscape is made up of harsh cliffsides and thin pathways, ravines that lead down to bottomless pits, and overgrown roots that make almost every surface feel unstable. When there is architecture in the world, it takes on either a sort of ramshackle and dangerously leaning appearance in the case of the spaces like The Undead Settlement, where it is clear that the place may have once been a kind of pleasant village but was patched and repaired over and over again into barely standing structures. Otherwise, the architecture is grand, heavy, and old medieval styled. These are usually the places that have some additional historical importance to the game world, such as Lothric Castle, the home of the twin princes who rule the kingdom. Though even these structures are falling apart, tied to the themes of the game, and most of the locations that the player visits have long past their prime when they are visited. For example, the Cathedral of the Deep, an area once home to a legendary Lord of Cinder, is now nearly empty, with tattered cloth all over the floor and walls, as well as the central chambers all having been filled with a sort of black sludge (Dark Souls III). The pathways through these places are, in many cases, actual roads that have been left to the sands of time and have not been kept up, not dissimilar to the old Roman roads that were left behind after the collapse of the empire.

On another note, though also necessary for the background of this paper, is the term “narrative” in reference to videogames has been a subject of some debate, due to the non-linear nature that many games take in their storytelling (Ryan-Thon, 173). Dark Souls III, however, sticks to a relatively linear structure in its plot and keeps the important information in sequence. Therefore, in this instance “narrative” will serve as a good term to examine the story being experienced by the player and make it easily relatable in the context of literary pilgrimage narratives. In his chapter on game abstraction in Storyworlds across Media: Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology, Jesper Juul also suggests an alternative phrase, “fictional world” (Ryan-Thon, 173), following in the footsteps of a similar phrase used by Jan-Noël, “Storyworld” (Thon 289). While both of these are good alternatives, they will be employed here more specifically to refer to the world of Lothric that Dark Souls III is set in, as the world space itself is a core part of what makes the game a game and allows it to communicate its message.

Finally, in terms of background, there is the more formal games language that is used to describe Dark Souls III on a kind of meta level. The game is considered to be a roleplaying game (RPG) due to its elements of levelling up and encouragement of the player to approach problems in-game with a variety of different strategies. The setting invokes the traditional hallmarks of the medieval fantasy genre as well, as the player encounters knights, dragons, giants, castles, kings, and princes. With this established, invoking the Middle Ages as pretext for the storyworld (Eco, 68), a baseline understanding of the game and its tone has been established.

III. Foreground

Religious pilgrimage is almost synonymous with the Middle Ages and was an important part of the travel culture at the time. Roads themselves were recognized as being extremely valuable and were supported often by those who could afford it, especially those main thoroughfares that would take merchants, pilgrims, and general travelers across medieval European landscapes (Allen, 27). Pilgrims in particular made a core part of the necessity of roads as the quest they undertook was both holy (Osterrieth, 146) and economically beneficial for pilgrimage sites (Osterrieth, 153-4; Salonia, 3). What makes a pilgrimage distinct from other travel through the medieval landscape, however, is that they often focused on the relics and holy places of Christianity (Salonia, 3). Matteo Salonia suggests, in his article, “[The] reverence and physical journeys towards relics and saints were less theologically controversial than reverence and pilgrimages towards holy sites because of the new place assigned to the human body within Christian cosmology,” a sentiment that is mirrored in the bodily nature of the travel that would take place to visit such a relic (Salonia, 5). This is tied into a sort of Medieval Christian interest in the body, specifically the body as a means to channel spiritual energy into miracles and shows of faith (Salonia, 5). This differed from the Platonic view that had dominated before the Christian tradition, which placed the body as adversarial to the mental and spiritual pursuits of an individual (Salonia, 6).

Anne Osterrieth, in her article on pilgrimage as a personal quest, comments on the body-centric nature of the pilgrim’s movement, saying, “The pilgrim also drew pride from his capacity to undertake his task. He was becoming a seasoned traveler and derived pleasure from this new competence” (Osterrieth, 152). In popular media, which depicts pilgrims in a much more dower light, this attribution and celebration of prowess seems almost antithetical. However, Osterrieth emphasizes the pilgrim’s journey as one of death and rebirth, from the person they were who needed divinity into the person who has come in contact with divinity and is ready to advise the next on their journey (Osterrieth, 152). This shows that the person on a pilgrimage was, of course, seeking out a relic or holy place to venerate and receive blessings from, but also that along the way there is an unintended but necessary physical growth as they become a competent traveler and learn to deal with the challenges of long road travel.

This travel was far from unguided otherwise, as people consulted other travelers, maps, or guides to get them to their shrines of destination (Allen, 28). In the minds of the pilgrims, explored by Valerie Allen, the road was not always present, “we might call this [instrumental] representation of the road as means to end the default understanding of roads, in which they function as connectors between settled communities” (Allen, 33). Allen is looking at the pilgrimage narrative in the Book of Margery Kempe, which describes the travels of 15th century titular businesswoman, Margery Kempe (Allen, 27). This narrative, however, is where Allan draws the almost complete disregard of the road from, as it seems that Kempe herself did not find that part of the experience worth keeping track of in the same detail as the rest of her visits and exploits (Allan, 29).

Ritual, here, becomes a big part of the discussion of pilgrimage, which is itself inseparable from conceptions of rituals. “Ritual as a type of functional or structural mechanism to reintegrate the thoughtaction dichotomy, which may appear in the guise of a distinction between belief and behavior or any number of other homologous pairs,” is a definition of ritual put forward by Catherine M. Bell, in her work, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice (20). She goes on to summarize that ritual is always tied to opposing forces in a culture or system of practice (Bell, 23). This provides a kind of structure that creates something of a cultural habit, something that fascinated scholar Pierre Bourdieu, is part of a kind of societal generative principal (Bourdieu, 78). Bourdieu takes this idea into a kind of forgetting of history and being left with only practice (Bourdieu, 79), which in some ways can be seen in some of the later ideas of pilgrimage to non-religious places or referring to the colonial settlers in America as “Pilgrims.” These tie into the discussion of pilgrimage as it establishes that pilgrimage as a ritual is always opposed to something else. In the case of historical pilgrimage this tension is between the safety of the village and staying in one place and the fulfillment of the journey at the end of a long and dangerous road.

IV. The Ground

Pilgrimage and Dark Souls III already share one thing in common, though debate has ensued about what role this takes in the narrative sphere (Bierger, 11), and that is the central necessity of space. It is space and travel that characterize a Pilgrim wandering medieval England, as well as the player character in Dark Souls III, embarking on their journey into the world of Lothric to link the fire. While the literal space is different, as there is the space that it takes to physically walk from place to place, there is a kind of abstracted sense of space that is present in Dark Souls III that is necessary for the nature of the story world (Ryan-Thon, 183). In this space between destination and starting point is where the pilgrim acquires their expertise and endures the hardships that will form them into the person worthy of accepting the blessings at the relic when they arrive (Osterrieth, 152). While in the game, the path works on a very similar level, having the player face challenges and gain experience to level-up their character so that they have the necessary competence when they come to face a boss like the first Lord of Cinder, the Abyss Watchers. Both the pilgrim and the player come across these various challenges, twists in the road, wild animals, other people threatening them, they also come across various moral encounters as well, such as to give aid or do favors for those they meet. In the reality of the past, this was much more literal, while in Lothric these moral actions take the form of side quests more often than not. In one example of a moral action that can be taken in the game early on in the Undead Settlement area, the player finds a woman, named Irina of Carim, trapped with a knight nearby. The player is told by the knight, “taken an interest in her, have you? Well, she's a lost cause. Couldn't even become a Fire Keeper. After I brought her all this way and got her all ready. She's beyond repair, I tell you" (Dark Souls III). To actually save her, if the player wants to, the process is pretty involved and includes gathering a whole other trail of items to get the door to Irina open. Alternatively, there is no real punishment for the player avoiding this action, much like in real life, and all further interactions and possible benefits of the NPCs are lost.

The main idea linking these two actions is the concept of The Quest, which is incredibly broad. But more specifically, the quest for contact with divinity, during which the central actor develops their own abilities in order to be ready to receive the divinity when the time comes. While this is plainly evident in the nature of the pilgrimage, in Dark Souls III the same concept applies. This is due, in-part, to the transmedial principal of minimal departure that was developed by Marie-Laure Ryan and adapted by Thon. The principal is “at work during narrative meaning-making that allows the recipients to ‘project upon these worlds everything [they] know about reality, [making] only the adjustments dictated by the text’ (Possible Worlds 51). It is worth stressing, though, that recipients do not ‘fill in the gaps’ from the actual world itself but from their actual world knowledge” according to Thon as he cites the original principal by Marie-Laure Ryan (Thon, 292). This principal allows for the game world of Dark Souls use the quest form much more naturalistically, allowing the player to take on the grand quest of their own pilgrimage through the Lands of Lothric in a mentally analogous process.

There is a pilgrimage here is part of the very core of the gameplay of Dark Souls III, as well as the narrative proper. Throughout the game, the player is told that it is their job to gather the necessary relics in order to link the flame, a process that proves an arduous journey and a game experience that FromSoftware has come to be known for. On the level of environment alone, there is a similarity here to the kind of landscape that a pilgrim might move through in medieval Europe, with its crumbling, ancient, ruins and overgrown roads. The oppressive and dark game atmosphere with the bonfires as checkpoints give a sense that would be not too dissimilar to that of a real-world pilgrim, going on an arduous journey only to find rest at a campfire by the side of the road. It is significant as well, that, in the very last segment of the game, the place that the player finally arrives at is a religious site, the city of Irithyll, where the most prominent buildings are those of churches. In this game area the player visits three, one called The Church of Yorshka, one that is unnamed but is home to the boss Pontiff Sulyvahn, and finally the grand cathedral of Anor Londo, where the gods once made their homes and is now home to Aldritch, a kind of heretical saint (Dark Souls III). It is after this point that the player must return to the starting citadel of Lothric to continue their journey.

It is also at this point of the game, as the player has made their way all around the kingdom of Lothric and even to places from the first couple of games in the Souls series, that this quest has been done before by others in the storyworld as well as by scores of other players before them. Combining this with the lack of direct story throughout the game, makes the player an agent in the meaning-making activity that the game has you go through, creating a kind of “intentionless action” (Bourdieu, 79). That is to say, with how little the game tells the player before their pilgrimage begins, the player is left to follow the game path and explore the story for themselves without fully clear intentions for what it is the in-game character is actually participating in. This is, in action, the kind of ritual repetition that leads to the unconscious repetition of the history of the players actions in the Bourdieusian sense (Bourdieu, 78).

Where the pilgrimage metaphor really comes full circle, however, is in the difficulty. It’s ironic to compare a medieval pilgrimage’s difficulty a videogame, but in its own space the Souls series stand as monoliths of difficulty. This difficulty, which is formed from a balance of timing-based combat and harsh punishments for failure, creates a kind of demand for focus. Whether the player wants to or not, the nature of the game demands that they pay full attention or risk losing hard-earned progress. This leads to, a kind of phenomenon where the player becomes more focused on the skill-based challenges and tunes out (or abstracts) for themselves the more complex elements of the game during the challenge (Ryan-Thon, 185-6). In a way not dissimilar from what Allen noticed with the Pilgrimage of Margery Kempe, where the repetitive action of travel was not as memorable as the destinations, the challenges and skill building (leveling up) being secondary to the large experiences of destinations (boss fights). Both walking for days and grinding through difficult game areas build patience in those who partake in each activity as well, becoming something of a meditative activity (Unknown, “Dark Souls is More than Just a Game”).

The moral component, while hard to measure, is an example of some micro-moral game morality throughout most of the game, much like in real life (Ryan et al, 57). However, much like the pilgrim’s ultimate quest being tied to the much more cosmically important goal of the afterlife of their soul, so is the ultimate morality of the quest in Dark Souls III, a large macro-moral choice to determine the fate of the storyworld (Ryan et al. 57). However, this is the area where Dark Souls III, much like other remakes and updated retellings of the stories of the past, adds in its own twist. The three endings of the game, usurping, letting die, or carrying on the flame, constitute a moral ending that does not present itself in the traditional stories of pilgrimage. Instead, the game asks its player at the very end of the game what they believe the best course of action is for the storyworld, one that has been limping along since the very first game in the series. This macro-moral decision is almost jarringly major in comparison to what minor interactions that the player has had up until that point and brings a sense of ultimate closure no matter what ending is taken. The game of course has additional content and gameplay to enjoy after the credits roll, but the narrative itself concludes finally in one of three ways. Each option, however, recolors the actions that the player took to get to that point, either as a would be king of humanity, a savior sacrificing themselves to keep the world going for another cycle, or as a savior in another sense, finally letting the limp and broken world fade into darkness.

V. Conclusion

From the content on the story itself, a lone character looking to keep the fire of the world burning and trekking across the land of Lothric, to the player’s experience of the game play, Dark Souls III sets itself in the same style of narrative as that of the experience of pilgrims. Both game and historic action culminating in a building of skills and triumph over adversity that many others may not be willing to undertake. Even with little motivation in a bleak and harsh world that appears stacked against almost every move that the player and their character work towards. While Dark Souls III may only be channeling this kind of mentality for the benefit of the player’s experience, it casts its spell regardless and has left a lasting impression on both individuals as well as the games industry as a whole (resulting in the Soulsborne game genre). However, more than just affecting the entertainment industry as a whole, Dark Souls III gives a mediated experience of one of the time-honored traditions that was once a massive undertaking across Christendom, calling up the past as it seeks to tell its own story about a medieval-like fantasy world, and also the unidyllic descent into ruin that every age face, both in the world of the game and outside of it. From a narratological perspective, it gives an interesting challenge to where the border between game world and narrative actually divides two different experiences. While from a medieval perspective, it gives a unique look into the kind of crumbling and uncertain side of what history used to be through player experience. And all of that is without delving into the rich optional or expanded content that was added after the original release of the game.

Bibliography

Allen, Valerie. “As the Crow Flies: Roads and Pilgrimage.” Essays in Medieval Studies 25 (2008): 27–37.

Bell, Catherine M. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bieger, Laura. “Some Thoughts on the Spatial Forms and Practices of Storytelling.” De Gruyter 64 (2016): 11-26.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Eco, Umberto. "Dreaming of the Middle Ages." Faith in Fakes: Travels in Hyperreality. Transl. William Weaver. 1973. London. (1998) 61-72.

Miyazaki, Hidetaka. Dark Souls 3. Bandai Namco (2016).

Osterrieth, Anne. “Medieval Pilgrimage: Society and Individual Quest.” Social Compass 36 (1989): 145-157.

Ryan, Malcolm et al, “Measuring Morality in Videogames Research.” Ethics and Information Technology 22 (2020): 55-68.

Ryan, Marie-Laure, and Thon, Jan-Noël, eds. Storyworlds across Media: Toward a Media-Conscious Narratology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

Salonia, Matteo. “The Body in Medieval Spirituality: A Rationale for Pilgrimage and the Veneration of Relics.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 14 (2018): 1-10.

Thon, Jan-Noël, “Transmedial Narratology Revisited: On the Intersubjective Construction of Storyworlds and the Problem of Representational Correspondence in Films, Comics, and Video Games” Narrative 25 (2017): 286-320. Unknown, “Dark Souls is More than Just a Game” GameFAQs (August 30th, 2014) https://gamefaqs.gamespot.com/boards/606312-dark-souls/69969309

[1] Quotes from in-game dialogue are sourced from https://darksouls3.wiki.fextralife.com, a website that has transcribed the text of Dark Souls III’s dialogue and other in-game text in its entirety.

#Medieval#medievalism#pilgrimage#essay#my essays#class essay#dark souls#dark souls 3#soulsborne#undergrad research#narratology#world building#video games#medieval literature

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brother's Grimm Where THE GOATs!

Okay, folks, I just need to share this bit of hyperfixation right now.

As you know, I love mythological research and narratology. I grew up in Germany, so not only did I grow up knowing the Fairytales that those two men have written down, but I also grew up with a ton of schools in my surroundings being named "Brother's Grimm School". Because yeah, they are pretty darn big in Germany.

But until two weeks ago I did not realize how darn important those two were for German literature, mythological research and narratology.

Sure, I was well aware that the two of them did not invent the fairytales, but just collected oral tradition and formalized it, writing it down. And if course - as someone who knows about the importance of oral tradition and how much got lost because it was not written down - I also understood how important this was. Because a lot of those stories would have well gotten lost if it had not been for those two.

Something I did not realize however was, how much of the research methods within German literature research, mythological research and narratology has come from those two. Like, those two nerds did basically singlehandedly lay the groundwork for three different areas of research!

I only realized this now, as I stumbled across one of the "papers" (it was not quite as formalized back then) those two had written. And I was like: "Wait. Those two did actually a lot of research?" And so I started to look into it. And yes, darn.

Also, they did not only collected German oral tradition, but also Slavic oral tradition, and attempted to find people who knew Norse oral tradition still, because they realized that the Edda as written down were not reliable source, because it got colored so heavily by the Christian monks writing it down.

Like, holy shit. I really never realized how important they were for those areas of research. And all we remember them for is fairytales?!

#brothers grimm#fairytales#narratology#german literature#german studies#mythology and folklore#german mythology#norse mythology#slavic mythology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ahhh yes yes#fave#Shelley Jackson#patchwork girl#Frankenstein#hypertext#90s#electronic literature#feminism#hysterical narrative#fragmented#narratology

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The English word "personification" did not exist prior to the late seventeenth century. It derives from the French verb personnifier which Boileau coined in his Eleventh Reflection on Longinus (Haworth 43). Boileau used the neologism to exonerate Racine from the charge that the playwright was unappropriately lurid in Theramene's recapitulation of Hyppolyte's death scene at the close of Phedre (v.vi). Boileau's defense was built on the fact that Racine was conveying a moment of sublime sentiment, and, more importantly, that the playwright did not "speak the words himself," using instead Theramene as a verbal mask or representative (Haworth 44). Boileau's inkhorn term conveyed no more than the earliest Hellenic conception of the trope as a means for any dramatic presentation of a speech. The new term proved so potent, apparently, that little more than a century later, another French thinker - Pierre Fontanier - saw the need taxonomically to separate la personnification from la prosopopee. Boileau's successful neolatin coinage, however, carried a new conceptual charge alien to the conservative connotations of the word "prosopopeia." According to Foucault and a number of other contemporary thinkers, the concept of the "person" is an invention of the late seventeenth century (Sexuality 17—47; Rorty 17—69; Zimbardo 1—14; Elliott 3—32; Ginsberg ch. 1). A human person was, for thinkers as varied as Montaigne, Descartes, John Locke, or Theophilus Gale, a rational being constituted by an entirely interior psychology, by a discrete, unique, and private consciousness that functioned as its own mechanism of self-definition and regulation. Boileau's engagement of the French word personne, or rather, of the Latin word persona, latched onto a concurrently evolving sense of what a human being was thought to be. As this book has shown, the figurally invented personages that result from personification are anything but realistic or modern "characters." The latter are fictive and simulational human beings, who, according to Rose Zimbardo, are native to literature only after the late seventeenth century and who possess an "internal arena" of soul and psyche (2). Indeed, Zimbardo holds that no fictional character, prior to the time of the English Restoration, was conceived of as an accurate simulacrum of psychological interiority. Such characters were mere ideational effigies. The seventeenth-century conceptual shift concerning personality and mind punctured old expectations of what literary character could be. The term "personification," by dint of its new connotational force, was therefore at odds with the older conception of "prosopopeia." Although both words etymologically mean "to make a face or mask," "prosopopeia" retained that sense of sheer literary game or artifice. "Personification," on the other hand, could have promoted a deep conceptual confusion about its status and value. Literature and drama became more and more taken up with the mimesis of actual human personality — a conceptual property promised but not delivered by the term "personification." This knot of lexical and conceptual confusion may be concomitant upon the trope's imminent historical decay as a serious and powerful means of poetic invention.

-James J. Paxson, The Poetics of Personification pages 171-172.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I’ve been like neck-deep in Elden Ring lore since it came out and I’m fascinated by something.

I got bored a couple of years ago and started writing a lore doc for the Dark Souls trilogy. Really diving into it—I’m still picking at the DS3 section (kinda ran out of steam and never finished that part; really I wanna redo that whole section) and it’s already like 200 pages. And it’s not that it wasn’t kind of challenging to organize, but there’s a linearity to those games—a logical skeleton of progression on which to hang all the esoteric muscle tissue of explanation, y’know?

But in trying to think about how to do the same thing for Elden Ring, I keep having trouble. Like do you organize it by region and who you encounter there? Do you talk about the history and the major players (Marika/Radagon, Godfrey, the demigods) and THEN go through the current story of the game by region, exploring the members of each faction and their individual stories? Do you go through the six endings and explain the storylines involved in each one? A secret fourth thing I haven’t thought of?

Regardless of how you do it, any such document would have to be insanely cross-referential to make any sense. Take Ranni’s questline. It’s so woven through so many other different parts of the story, you have to explain so many other things (the Nocturnal cities, Radan’s whole deal, the Night of the Black Knives, which means also Godwyn, Marika/Radagon, the Numen, etc), when do you talk about that? How do you put all that together in a coherent way? And you can’t like, set up all that stuff first, cos you run into the same problem in reverse—you need to understand Ranni to understand a lot of those things. And all of it is like that. It’s hard to isolate and explain any one bit of it.

The game is rich with narrative, positively fucking bursting with it: distinct characters with individual psychological motivations, complex enmeshment of distinct cause and effect that reflects those characterizations—this is a very story heavy game. But beyond even that typical FromSoft obscurity where the actual plot is hidden in what would normally be lore, this one does something with storytelling structure. There IS that cause-and-effect chronology to it, but that’s not how the presentation is arranged—the best way I can currently explain it is that it’s taking advantage of the open-world format in creating a story that’s discovered in space, not time (I’m working on refining that language). Something that 1) would be really difficult to achieve in any other medium, and 2) makes it very difficult to translate into something like a written summary that is, by the nature of language, linear.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 Game Design and Game-Making Bogs, Books, and Pods

As a game maker and designer, I understand the importance of staying up-to-date with the latest trends and techniques in game design and development. To help my fellow designers and developers, I have compiled three lists: the top 10 game design and game-making blogs, the top 10 YouTube channels, and the top 10 game design podcasts. Top 10 Game Design and Game-Making Blogs: Gamasutra:…

View On WordPress

#creative writing#dramaturgy#game dev#game development#game making#game studies#game writing#games#Ludology#Narratology#storytelling#top ten#video game#video game blog#video game book#video games#Writing#game design#gamers#fantasy games#story time

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

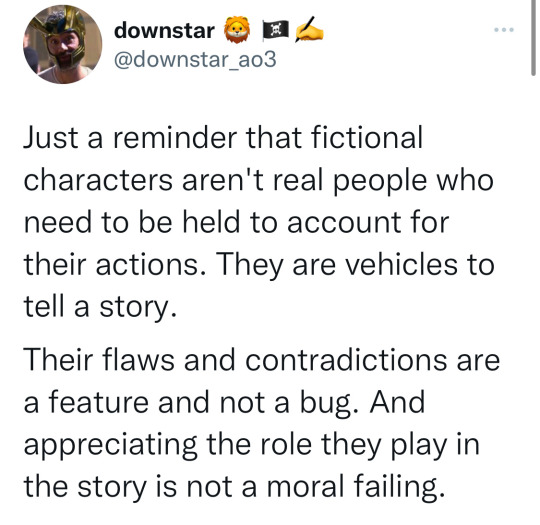

It's astonishing how easily people forget this!

Sure, I like to get upset with characters, judge their choices, criticise them and agonise over their actions - that's how I stay connected to the narrative. But ultimately it's about telling the best story. Not about punishing Aziraphale for leaving Crowley, or punishing Crowley for not going after Aziraphale.

199K notes

·

View notes

Text

Obsessed with this bit of The Poetics of Personification describing "Bugsy Malone" as some sort of narrative hyperstructure.

0 notes

Text

Alternative story continuation of "Star Wars"

With recent criticism of the route *Star Wars* has taken, I thought that I'd share a critique I did some time ago in the narratology channel on Philosophy and Politics Discord server. My argument was that the western soft power saw a decline with how they chose to continue the story of *Star Wars*. This is part of it where I try to construct an alternative story in place of the *The Force Awakens*.

I think that the new TV series they have chosen to make are a result of how the Skywalker trilogy didn't expand on the lore. With the general poor planning of the 3 movie arc, they really left the IP in a poor state. So the reason they are making prequels now could be that they saw it as a safer way to take a break from trying to expand on the lore that should be done in the landmark movies.

Everything unresolved could have been a gateway to expanding the lore. In my mind, there were three significant ones:

1. The nature of the Force.

Well, this could be anything. I consider the Force to be sufficiently separated from real-life science, making it difficult to work in a sufficient amount of exposition into a family movie to make the concept relatable. I would have skipped explaining it in the first movie and approached it with a more relatable concept: balance.

2. What does balance mean?

Luke was the one to bring balance to the Force, a concept that even kids can grasp. In the context of the Jedi and the Sith, the dynamics have not been made very clear.

At the end of the trilogy, the good guys win. Is the balance cyclical? Do the power dynamics shift, or is it confrontational? Do they balance each other out simultaneously? The latter would have meant an equally triumphant moment for the Sith as well. Or is it a hybrid of the two, which would also be interesting to dissect?

The expansion of this theme would have allowed for an exploration of the Force by gradually deconstructing the power dynamic until reaching the core nature of the Force.

3. Force ghosts indicate life after death.

Force ghosts function as a form of deus ex machina, and the existence of afterlife undermines the stakes of the story. It presents an opportunity for very hedonistic characters, which would be funny, but besides that, it decreases our connection to the story and its applicability to real life.

Taking the expansion of mythos as a starting point for an alternative story, I will try to construct few storybeats.

The general theme of the movie could be finality. Itself being rooted in duality, it presents wonderfully rich grounds for deconstruction. End and the beginning of the new. Also fitting for a reboot.

1. Conveying how Luke started to ponder on the afterlife.

Ideally this could have started at the end of episode 6. He sees all the force ghosts at the party. As we fade to black, he might have just gone back and asked them how is their presense possible. Depending on how much we want the theme of finality to weigh on Luke, he could be answered with different levels of clarity.

The answer he gets or don't get at all, depending on how much we would want it to bother Luke, is that it is either not his time to know/the balance comes with a price/they don't know themselves/ or they literally disappear without an explanation.

However it is conveyed, the outline of the story could be as follows:

After the fall of the Empire, Luke set on a mission to enforce that the small remnants of the Empire won't regroup. On his encounters, he learns about Anakin's wish to defeat death and how it was his downfall. He starts to grow weary of death after the uncertainty of his mentors leaving without an explanation and the fact that death has had such an impact on his life through Anakin and Padme.

He might develop a fear of sending his padawans to missions . Maybe previously puts some of them in serious danger or loses completely. Fear leads to suffering and so on.

While I wouldn't like him to get anywhere close to having a brush with the dark side himself, his doubts could be done without undermining his previous development.

2. Looking for the meaning of balance.

The fairytale interpretation of Star Wars has also some ground in the story having a prophecy. In the movies at least the backround of it is unresolved.

If anybody wants to read one thorough interpetation of balance in the force, can do it here. Maybe anybody has better ones.

Post by Daniel. 16 upvotes.

https://movies.stackexchange.com/questions/46728/what-does-the-prophecy-exactly-say-in-the-star-wars-saga

I would consider this explanation pretty suitable for the approach to expand on it. The Force is a force of nature. It just is. It doesn't have a duality to it but more like a flow. At least to the best of our understanding. Balance is not a state for the force users but to the Force itself.

These are all very suitable themes for family movies. How to convey them for everybody to stay engaged is another question. This reasoning here may not insert any confidence that some blockbuster trilogy with wide appeal could be built around these themes. But then again, the same could be considered for the original movies.

Lots of semantically ambiguous approaches would leave the door open for further expansion. However drawn out it could become. You could even include social themes in the semantical ambiguity. Not necessarily, but you could.

We could have used more focus on creating some common ground and a literary example with language about the ambiguity of life for a start. A little more unification and continuous deconstructing of dualities would have sufficed. We could have developed pop cultural references to implement the language needed for nuance. Or a source for jokes and silly impersonations to deflate situations that have run into awkward stand-offs. Leaving the door open to return to said discussions when the time is right.

The deconstructing of dualities leads us also to the possible ambiguity of finality and the emotional climax of the alternative trilogy.

Most likely the series should have a villain with a red lightsaber. This is one of the trickiest tasks to weave into the story. I can't crack this nut myself at the moment, but I'm sure it could be done.

Maybe Luke's own doubts and mistakes with his padawans and the unfortunate circumstances of their missions lead to the fall of one of his students. Could have been a better telling of the Ben storyline. Maybe they encounter a mistreated force sensitive person that becomes the Star Wars version of obscurious from the Fantastic Beasts. Someone with not bad intentions but antagonistic from bad circumstances, human flaws and manipulation. Maybe somehow Palpatine returns. I'm kidding. He shouldn't.

Whatever the conclusion between the protagonists and antagonists, the main focus should be on finality. Either Luke gets some closure on his fear of death and finality by the small lore drops from occasional encounters with force ghosts or him becoming one at the end himself and ensuring his padawans that: "Everything is going to be ok in the end. If it's not ok, it's not the end."

This phrase doesn't have a good pop cultural vessel anyway.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Big brain your textual analysis in English class. The characters do not just run amuck in the story. The author uses them for a purpose to convey meaning to the responder.

#hsc#English#English lit#English literature#textual analysis#big brain#meme#texts#narratives#narratology#australia#nsw#English teachers#englishliterature#essay#extension english 2#advanced english

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sidestepping such criticism is likely one reason (among many) why novels like Frankenstein and Dracula were written in epistolary form, where events primarily are described in first-person, but from multiple characters to paint a complete picture of events that no single character could have witnessed in their entirety.

"Why does this 19th Century novel have such a boring protagonist" well, for a lot of reasons, really, but one of the big one is that you're possibly getting the protagonist and the narrator mixed up.

A lot of 19th Century literary critics had this weird hate-boner for omniscient narrators – stories would straight up get criticised as "unrealistic" on the grounds that it was unlikely anyone could have witnessed their events in the manner described, like some sort of proto-CinemaSins bullshit – so authors who didn't want to write their stories from the first-person perspective of one of the participating characters would often go to great lengths to contrive for there to be a Dude present to witness and narrate the story's events.

It's important to understand that the Dude is the viewpoint character, but not the protagonist. His function is to witness stuff, and he only directly participates in the narrative to the extent that's necessary to explain to the satisfaction of persnickety critics why he's present and how he got there. Giving him a personality would defeat the purpose!

(Though lowbrow fiction was unlikely to encounter such criticisms, the device of the elaborately justified diegetic narrator was often present there as well, and was sometimes parodied to great effect – for example, by having the story narrated by a very unlikely party, such as a sapient insect, or by a party whose continued presence is justified in increasingly comical ways.)

#literature#history#literary history#tropes#narratology#protagonists#narrators#19th century#Frankenstein#Dracula#profanity#there I said something

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Current State of Games for Learning: Engaging Education Through Play

In recent years, the intersection of gaming and education has sparked a fascinating conversation around how play can enhance learning outcomes. Games for learning, or “serious games,” are not just entertainment anymore—they are becoming powerful tools in classrooms, corporate training, and even personal development. As the demand for engaging, personalized, and adaptive learning grows, game-based…

#education#edugaming#game based learning#game design#game designer#game development#game studies#game writing#games for change#games for learning#Immersion#instructional design#interactive fiction#learning#learning design#narrative#narrative design#Narratology#phd#storyteller#storytelling#video games#visual storytelling

0 notes

Text

Thinking of the narrative structure of Herbert’s Love III, and how it ontologically replicates what is so moving about the devotional poem.

The speaker sits down and eats “Love,” and Herbert lets us to do the same through his writing. Weil’s reading of the poem in Waiting for God is spot on. Herbert is the vehicle of her self-described possession.

Forever my favourite poem, and the ultimate poem about love and ‘the power of literature.’

0 notes

Text

In looking into game studies as a whole, The idea of the Value of Augmented Reality Games as a point of research cannot be ignored.

they're entire stories told via making the viewers complete puzzles. a story made of games, rather than tabletop's games made of stories!

this article is meant to look into how such a concept could be used in the real world for real problems.

1 note

·

View note