#Mongolian history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Time Travel Question 61: Middle Ages and Much Earlier

These Questions are the result of suggestions from the previous iteration.

This category may include suggestions made too late to fall into the correct grouping.

Please add new suggestions below if you have them for future consideration.

#Time Travel#Mastodons#Megafauna#Triceratops#Dinosaurs#Pre-History#Dimetrodons#Saber-toothed Cats#Smilodon#Chinggis Khan#Genghis Khan#Mongols#Temüjin#Mongolian History#13th Century#Medieval History#Middle Ages#Athens#Ancient World#Canaanites#Ancient Religions#History of Religion#West Asia#Denisovans#Homins#Paleolithic#Prehistory#The Ghana Empire#Ghana#Ghanata

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold damascened helmet, Mongolian, 15th-17th century

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

On This Day In History

May 5th, 1260: Kublai Khan become leader of the Mongol Empire.

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is summer after spring.

Batu and Borakchin khatun.

#mongol empire#mongol history#mongolia#batu khan#batu#the golden horde#mongolian history#borakchin#spring

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

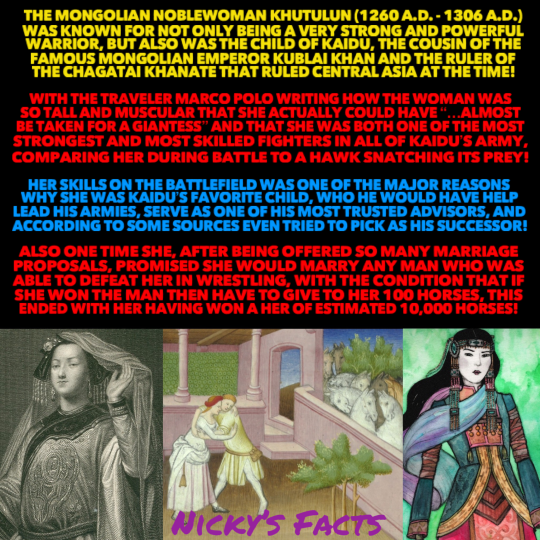

Khutulun was proving that women can be stronger then men 100 horses at a time!

🐴🇲🇳🐴

#history#khutulun#mongolia#kaidu#chagatai khanate#womens history#central asia#mongolian empire#princess#historical figures#strong women#medieval period#mongolian history#girl power#warrior woman#womens history month#kublai khan#fit girls#female empowerment#princesscore#horses#athletic women#medieval history#royalty#wrestling#khanate#military#nickys facts

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mongolian Archery/Headcanons

- In the Middle Ages, Mongolian archery held great military significance. The earliest recorded bow shot was made in 1226 as a stone inscription, by Yisüngge, Chinggis Khan's nephew, achieving a remarkable 335-fathom (about 575 yards) shot.

Stele of Yisüngge.

- Mongolian men were trained from a young age to become excellent marksmen, and archery played a crucial role in their military prowess.

- According to the Franciscan friar John of Plano Carpini, Mongols started shooting from the age of two, and they displayed excellent marksmanship skills from childhood to adulthood.

- Mongolian men dedicated much of their time to crafting their own arrows, which had diverse heads made from materials like bone or iron.

- The powerful tension of the bow caused it to spring back when unstrung, a challenge often mentioned in Mongolian epics as the heroic test of stringing a powerful bow.

Traditional Mongolian Bows and Arrows:

- Under the Qing Dynasty (1636–1912), all bannermen were required to undergo archery training. The military compound bows were typically about 1 1/4 meters (four feet) long, but longer bows up to two meters (six feet) were used for hunting.

- A grown man was required to handle a minimum pull weight of about 37 kilograms (80 pounds), while those participating in the imperial hunt needed to manage around 60 kilograms (133 pounds).

- Training included shooting from a standing position and also while galloping on horseback. Archers held the reins in their left hand or mouth while using their right hand to pull back the bow.

- The bows were constructed using a core made from goat horn or deer antler, covered with wood (larch, elm, or bamboo), and wrapped in animal tendons. The bows were powerful and required skill to string properly, making this task a distinguishing test of a hero's strength in Mongolian epics.

- The bowstrings were made of silk threads or leather wrapped in tendons, and arrows were crafted from materials like pine, birch, or willow. Arrowheads were made from deer antler, bone, or iron.

- Well-constructed compound bows and arrows were highly prized and fetched high prices. While powerful war bows were used for large game, simpler bows made of strips of fir or larch were used for small game.

Traditional Archery Techniques

- Mongolian archers used a unique technique of placing the arrow on the right, or outer, side of the bow. The arrow was held with the thumb and forefinger, and the bowstring was drawn with the thumb, protected by a heavy leather or polished stone ring.

- To release the arrow, the archer rolled the string off the ring. Skilled archers were trained not only to shoot from a standing position but also while galloping on horseback, using their right hand to draw the bow and holding the reins in the left hand or mouth.

Archery Competitions and Targets

- Archery competitions were an important aspect of Mongolian culture during religious rituals and Naadam games.

- In military competitions, the targets were made of sheepskin stretched over wooden frames or wooden balls placed on poles about 1.7 meters (5.5 feet) high. They were sometimes called "mangas" or monsters, as the Mongols found it disturbing to target human or animal figures.

- In Naadam games, archery was practiced using large, blunt ivory heads. The most common target was a pyramid or line of sur, made of leather straps rolled into a cylinder and filled with oak bark or leather, which the archers were required to knock over.

Decline and Revival of Archery

- By the late 19th century, firearms became more useful in hunting and warfare, causing a decline in archery competitions.

- Among the lamas of Khüriye (modern Ulaanbaatar), archery was replaced with shooting astragali (shagai) at a distance of 3 meters (9 feet) using horn or ivory bullets (ankle of sheep and goat) flicked by the middle finger from a wooden plank. This is because, due to their religious beliefs, they could not touch a weapon.

This is my own shagai set by the way!

- In the early 20th century, efforts were made to revive archery as a sport. In 1922, the army Naadam in Mongolia and in 1924, the Sur-Kharbaan (Archery) games in the Buryat Republic became annual events, marking the resurgence of archery as a recreational sport.

Changes in modern Archery

- In modern times, traditional Mongolian bows are still used in Mongolia, with archers using the traditional thumb technique.

- However, among Buryat and Inner Mongolian archers, European-style professional model bows and Western shooting styles have been adopted.

- The National Holiday Naadam rules now involve each man firing 40 arrows at a distance of 75 meters (246 feet), and women shooting 20 arrows at a distance of 60 meters (197 feet).

Headcanons

Mongolia obviously takes great pride in his cultural heritage and traditions. Archery is an integral part of his history and has been for centuries. It’s a skill that takes years to perfect - to become proficient one needs to develop both physical and mental control.

I think making bows would be a hobby of his! Not only does it keep him connected with his culture and history - as I previously mentioned, it's a skill. Bow-making/archery not only is a creative hobby, it's a physical and mental one too because of the patience and precision that is needed to create the bows/arrows, and of course, the archery itself is a mental and physical challenge!

The process of making his own bows can be both therapeutic and challenging at the same time. It requires a lot of patience and attention to detail while working with natural materials that may require specialised tools not commonly found today.

Nevertheless, he finds it to be an incredibly fulfilling experience to create something entirely by hand that is also functional and aesthetically pleasing. He enjoys painting/putting designs on them and he has quite a diverse set.

So really, bow making and archery for him:

Helps him stay in touch with his culture and history

A creative hobby

A hobby that requires mental fortitude/patience

A physical hobby

He's glad to have finally seen a resurgence and celebration of archery in his country after the rise of firearms kind of depleted it's use/popularity. It is now seen as a recreational sport in Mongolia and he treats it as a recreational sport too.

He takes pride watching participants demonstrate their skills during the Naadam Festival and other competitions where they strive to shoot targets from quite a distance away with incredible precision. The sound of the bowstring when an arrow releases - that twang sound- never gets old for him!

When he watches the younger generation take up archery, it does indeed remind him of his own experiences learning the skill as a child too.

I must say, he's still got a few tricks up his sleeve when it comes to horseback archery - even after all these years! At times, he still participates in local competitions just for fun (jock™)- he loves the the thrill of hitting a target while galloping alongside a horse.

It's definitely not something you can master overnight. Horseback archery requires an immense amount of control as well as skill from both the rider and the horse. Nevertheless, given his background as someone who understands strategy and has trained with bows since ancient times- participating is always an exciting prospect.

Sometimes he gets the chance to assist in judging in some archery competitions, which he always enjoys. He also enjoys reading about archery from different cultures too!

Of course with all of his responsibilities, he doesn't do this as often as he would like. However if you ask him about it, he'd probably do a bit of an info dump on you.

In essence, archery provides the perfect balance of discipline, creativity and physicality that he personally finds very fulfilling. Plus, it’s just plain fun!

#hetalia#aph mongolia#hws mongolia#Hetalia Mongolia#hetalia world stars#hetalia world series#hetalia world twinkle#historical hetalia#Aph Asia#Hws Asia#aph east asia#Hws east Asia#hetalia headcanons#Hetalia headcanon#OC Baatar Batbayar#Mongolia#Mongolian history#mongol history#Mongol Empire#Mongolian Empire#horseback archery#Archery#Mongolian Archery

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mongol Empire - John Man

Read: Feb - Mar 2024

This was an interesting read. The Mongols are such an interesting topic. The way they spread all over Eurasia is still very impressive. So I was intrigued to learn more. I should have paid more attention to the tag line however, because I was mildly disappointed when Man kept his focus on China. Truly in terms of scale the Mongolian Empire was so vast and disparate that it would be hard to cram it into one book. But I definitely thought I was getting a more overview of it all situation. Instead we got the humble beginnings, which are always relevant, and actually it's kind of wild how little we do know about said beginnings. Man's discussion on sources made it abundantly clear that there are things we just will not know, despite the Mongols importance to history.

Some surprise amount of mystery around Genghis's life and death. More than I would have thought, especially considering Kublai was Emperor of China and China had the tools, resources, and learning to have an history written. Which to be fair, one was, but it's just surprising that it's the state propaganda one. Like I'm lowkey annoyed that there's not more material written about it. Sorry, annoyed that more wasn't found/survived. I'm sure there was reams written about the new invaders, alas, most seems to be gone. Historians are really piecing it together from all the weird pieces left and making a narrative of found facts and educated guess work. Still no amount of guessing will produce the grave of Genghis, unfortunately. Gods, could you imagine someone finds it by accident? That would be so funny, but also so juicy, and I'm sure politically fraught.

Anyways back to the book, after Genghis we spend time with his heirs and especially Kublai, who founded the Yuan Dynasty. As an aside: my personal folk etymology for dynasty, is because royals often die nasty. Anyways Man takes us through Kublai's life and then, the book is wrapped up at warp speed. Only whispers of the rest of the dynasty and then a brief account of its fall. Barely a word about what happened to the more western parts. I wanted more. Which of course I can presumably find elsewhere, I'm just being silly expecting Man to do it all. In any case I learned a lot reading this and it was totally worth it and so interesting. Man definitely is not a dry history writer, so it was easy to be brought along.

Info: Corgi Books; 2014

#the mongol empire#john man#non fiction#nonfiction#history#asian history#mongolian history#chinese history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

KHUTULUN // PRINCESS OF THE MONGOLS

“She was a Mongol noblewoman and wrestler, the most famous daughter of Kaidu, a cousin of Kublai Khan. Her father was “most pleased by her abilities”, and she accompanied him on military campaigns. She was described by Marco Polo as a superb warrior, one who could ride into enemy ranks and snatch a captive as easily as a hawk snatches a chicken. She insisted that any man who wished to marry her must defeat her in wrestling. Winning horses from competitions and the wagers of would-be-suitors, it is said that she gathered a herd numbering ten thousand.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

This pic haunts me. Queen Genepil was pregnant.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mongols definitively abandoned their Western wars when one more khan died and his successor, Khubilai, immortalized by the English poet Coleridge's drug-crazed vision of his palace at Xanadu* ("That sunny dome! Those caves of ice!"), finally determined to finish off China.

*This famous name is actually a misunderstanding of the city's Chinese name, normally transliterated as Shangdu. The site of Khubilai's palace is currently under excavation.

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quotes#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#mongol empire#mongolian history#war#abandoned#khubilai#immortalized#samuel taylor coleridge#kubla khan#xanadu#shangdu#china#chinese history

1 note

·

View note

Text

But then – just as suddenly as they had abandoned China – they departed, turning their ponies around and herding their prisoners off into Inner Asia.

"Why the West Rules – For Now: The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future" - Ian Morris

#book quote#why the west rules – for now#ian morris#nonfiction#mongol empire#mongolian history#china#abandoned#departure#ponies#turn around#prisoners#inner asia

0 notes

Text

Pop culture Chinggis Khaan: "I am the Wrath of Heaven, and my destiny is to conquer the entire world, so I will invade China and Persia at the same time!"

Actual Chinggis Khaan: "Ugh, that asshole massacred my trade caravan, so now I have to schlep all the way to Khurasan to go slap his nephew. Muqali, Alaqai, keep up the pressure against the Jin while I'm out in the west. Xuanzong has got to realise he's outclassed and accept becoming our vassal one of these days, right? Right?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

"but the Mongols were being smartasses since they intended on killing them in bloodless fashion. Since it was the tradition of the Mongols that they would not spill the blood of royalty or nobility, they organized a victory feast which was to be celebrated atop a platform (“bridge”) made of wooden planks. Mstislav Romanovich the Old of Kiev and the other princes were tied up and thrown under this platform. Here they suffered a slow and painful death from suffocation due to the immense weight and pressure the platform placed on them."

I'm sorry but describing the Mongols as being smartasses made me snort LMAO.

The Mongols be like: We do a little trolling 😜

THE MONGOLS AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD AND THEIR ‘BATTLE OF THE KALKA RIVER’ AGAINST THE RUSIAN REALMS:

“We know not whence they came, nor where they hid themselves again. God knows whence he fetched them against us, for our sins.” – Novgorod Chronicle.

The following is an excerpt from my post, “GENGHIS KHAN, THE STALLION WHO MOUNTS THE WORLD”.

Mongol horde on the march

Now we turn our attention to the west, with the Khwarezmian Empire effectively conquered, what became of Shah Muhammad II of Khwarezmia? Back in 1220 CE he fled from the face of the Mongols, seeking refuge and aid in the west. Genghis Khan sent the great Mongol generals Subotai (the strategist) and Jebe (‘the arrow’) in pursuit of him. However, the Shah he died of pleurisy in 1220 CE before the Mongols reached him. While Genghis Khan and his sons were still hunting down the Shah Muhammad II’s son Sultan Jalal, Jebe and Subotai asked the Great Khan for permission to lead a reconnaissance in force to the mysterious lands to the west of the Caspian Sea.

The Mongols were skilled in leading long and deep raids into enemy territory, even when they were miles apart they kept in touch and could quickly regroup if necessary. This is proven throughout their campaigns against the Jinn dynasty (Tungusic Jurchen) of northern China, the Kara Khatai Khaganate (Turco-Mongols) of Central Asia, the Khwarezmian dynasty (Turco-Persian) of Greater Persia, and their raids under Jebe and Subotai to the Caucasus Mountains and beyond. The professional Mongol army believed in marching dividedly and leaving scouts at all their flanks, this division of manpower made it easier to cover more ground in shorter time and made it difficult for the enemy to track one individual force. The Mongols were strict about their decamping armies leaving behind no trace for the enemy to follow, punishing severely any who failed to clean up after themselves or their comrades.

“If you march in a large body of three or four hundred, with a design to attack the enemy, divide your party into three columns, each headed by a proper officer, and let those columns march in single files, the columns to the right and left keeping at twenty yards distance or more from that of the center, if the ground will admit, and let proper guards be kept in the front and rear, and suitable flanking parties at a due distance as before directed, with orders to halt on all eminences, to take a view of the surrounding ground, to prevent your being ambuscaded, and to notify the approach or retreat of the enemy, that proper dispositions may be made for attacking, defending, And if the enemy approach in your front on level ground, form a front of your three columns or main body with the advanced guard, keeping out your flanking parties, as if you were marching under the command of trusty officers, to prevent the enemy from pressing hard on either of your wings, or surrounding you, which is the usual method of the savages, if their number will admit of it, and be careful likewise to support and strengthen your rear-guard.” – The 28 Rules of Ranging by Robert Rogers, rule 6.

If the situation urged one into conflict, the other divisions could swiftly join together. The Mongol army also made great use of scouting parties which could be as much as a seventy miles ahead, behind and at their flanks. These scouts gathered intel in the form of geography, enemy positions and numbers, settlements, viable camp locations, terrain advantages and disadvantages, and sources of water. The Mongol horde obtained an almost constant flow of information. Since these scouts were light cavalrymen and were armed with long ranged weapons, they could also skirmish or lure the enemy toward a larger Mongol force.

Remount system and the ‘Yam’ pony express

“To appreciate the Mongol you must see him on horseback,—and indeed you rarely see him otherwise, for he does not put foot to ground if he can help it. The Mongol without his pony is only half a Mongol, but with his pony he is as good as two men. It is a fine sight to see him tearing over the plain, loose bridle, easy seat, much like the Western cowboy, but with less sprawl.” – Elizabeth Kendall.

Since under Genghis Khan each Mongol brought along up to six horses, they could implement the so-called ‘remount system’. With this system the Mongols could ride a horse for a set amount of time and then saddle up another and ride further without ever overextending each horse. With this system a Mongols would be able to speedily cover tremendous distances with few breaks (examples: 130 m. in two days; 180 m. in two days through deep snows) as they were also known to rest while on horseback.

All this was done on the famed Mongolian horse (aduu) which was known to be a short (4 ft. 5-8 in.) and stocky breed (600 lbs.) with tremendous stamina and endurance, capable of providing a steady ride over long distances (600 miles in nine days). This steadiness granted the archers a clean stage from which to fire off clean shots, usually in between strides. Also granting stability was the Mongol saddle which was high in the back and front, making it easier to swing your torso to a position that would allow the rider to shoot behind them i.e. the Parthian shot.

^ Osprey – ‘Warrior’ series, issue 084 – Mongol Warrior 1200-1350 by Stephen Turnbull and Wayne Reynolds (illustrator). Plate B.

When Jebe (‘the arrow’) and Subotai began their reconnaissance of the Caucasus they encountered the Christian kingdom of Georgia (1008–1490 CE) which was just about to join the Fifth Crusade (1213–1221) CE). After a skirmish, Jebe led a feigned retreat which lured the Georgians into a long and tiring chase which ended in an ambush prepared by Subotai. Jebe then mounted fresh horses (remount system) and together the two were able to effectively destroy Georgia’s aristocracy in one grand clash.

Throughout their many campaigns, Mongol divisions kept constant communication with one another by means of smoke signals, torches, whistling arrows, flags, arm signals and messengers on horseback. The Mongols were renowned for their mounted courier service (‘Yam’). The Mongols established way stations and posts about 20-30 miles from one another and assisted in allowing said couriers to cover 200-300 kilometers (c. 124–186 mi.) with aid from the remount system. Some have been said to have traveled up to as much as 2,000 kilometers (c. 1242 mi.) in a short period of time with few long breaks. These stations worked as rest stops where the couriers, dignitaries and merchants could sleep, eat, drink, and grab a fresh horse (remount). The famed Venetian merchant and traveler Marco Polo and Giovanni of Pian del Carpine who traveled as the Pope’s ambassador to the Mongols between 1245 and 1247.

“It is an army after the fashion of a peasantry, being liable to all manner of contributions (mu'an) and rendering without complaint whatever is enjoined upon it, whether qupcbur, occasional taxes (avarizat), the maintenance (ikhrajat) of travelers or the upkeep of post stations (yam) with the provision of mounts (ulagh) and food (ulufat) therefor.” – Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini (1226–1283 CE), Persian historian and governor of Baghdad.

These ‘arrow-riders’ were referred to as the “eyes and ears” of the Khan and as a seal of authority they wore paizas (large tablets) made of wood, silver or gold (according to the person’s importance and level of authority). Messages were kept orally, to help memorize them messages were formed in a rhyming format which made remembering the wording as simple as remembering song lyrics. This was not done solely by couriers or spies but also the common soldier, the latter of which were known to sing laws and military rules of conduct.

“Again, when the extent of their territories became broad and vast and important events fell out, it became essential to ascertain the activities of their enemies, and it was also necessary to transport goods from the West to the East and from the Far East to the West. Therefore throughout the length and breadth of the land they established yams and made arrangements for the upkeep and expenses of each yam, assigning thereto a fixed number of men and beasts as well as food, drink and other necessities. All this they shared out amongst the tumen, each two tumen having to supply one yam. Thus, in accordance with the census, they so distribute and exact the charge, that messengers need make no long detour in order to obtain fresh mounts while at the same time the peasantry and the army are not placed in constant inconvenience.

Moreover strict orders were issued to the messengers with regard to the sparing of the mounts, etc., to recount all of which would delay us too long. Every year the yams are inspected, and whatever is missing or lost has to be replaced by the peasantry. Since all countries and peoples have come under their domination, they have established a census after their accustomed fashion and classified everyone into tens, hundreds and thousands; and required military service and the equipment of yams together with the expenses entailed and the provision of fodder this in addition to ordinary taxes; and over and above all this they have fixed the qupchur charges also.” – Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini (1226–1283 CE), Persian historian and governor of Baghdad.

The Battle of the Kalka River, 1223 CE

“for our sins, unknown tribe came, whom no one exactly knows, who they are, nor whence they came out, nor what their language is, nor of what race they are, nor what their faith is; but they call them Tartars (Mongols)” – Novgorod Chronicle.

Jebe (‘the arrow’) and Subotai, the Mongols who pursued Shah Muhammad II and defeated the Kingdom of Georgia, now made their way across the Caucasus Mountains. The Mongol generals were able to enlist some Turkish steppe nomads while warring with the rest, one such foe were the Turkish Polovtsians (Cumans) of the Cuman-Kipchak Khanate (900–1220 CE).

”They are the Four Dogs of Temujin. They have foreheads of brass, their jaws are like scissors, their tongues like piercing awls, their heads are iron, their whipping tails swords … In the day of battle, they devour enemy flesh. Behold, they are now unleashed, and they slobber at the mouth with glee. These four dogs are Jebe, and Kublai, Jelme, and Subotai.” — The Secret History of the Mongols.

^ Polovtsian Khanate. Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 098 – Kalka River 1223 – Genghis Khan’s Mongols invade Russia by D. Niccole, V. Shpakovsky and V. Korolkov (illustrator).

These nomads were defeated so they fled towards the Slavic realms of medieval Russia and Ukraine, drowning the Rusians in gifts and warning them that: “Our land they have taken away to-day; and yours will be taken tomorrow”. The Rusians then believed that “If we, brothers, do not help these (Polovtsians), then they will certainly surrender to them (Mongols), then the strength of those (Mongols) will be greater.” The Rusian principalities joined a unified front against the Mongols and, aided by the Polovtsians, they marched toward their eastern border which was marked by the Dnieper River.

^ The Russian Armies Assemble. Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 098 – Kalka River 1223 – Genghis Khan’s Mongols invade Russia by D. Niccole, V. Shpakovsky and V. Korolkov (illustrator).

When the Mongols learned of the Rusian-Polovtsian confederacy, they sent envoys their way with a message conveying that they were only after the Polovtsians and had no ill will with the Rusians.

“Behold, we hear that you are coming against us, having listened to the Polovets men; but we have not occupied your land, nor your towns, nor your villages, nor is it against you we have come. But we have come sent by God against our serfs, and our horse-herds, the pagan Polovets men, and do you take peace with us. If they escape to you, drive them off thence, and take to yourselves their goods. For we have heard that to you also they have done much harm; and it is for that reason also we are fighting them.” – Novgorod Chronicle.

The Rusians, however, killed these envoys. The Mongols then sent a second batch of envoys informing them that since the Rusians “have listened to the Polovets men, and have killed all our envoys, and are coming against us, come then, but we have not touched you, let God judge all. (Novgorod Chronicle)” What the Rusians should’ve done was fought the Mongols by the Dnieper River where they would’ve held a tactical advantage and would’ve been near their own territories if need for flight or reinforcements arose. The only person who tried to urge holding the Dnieper River and forcing the Mongols into crossing it was a Rusian grand prince named Mstislav (III) Romanovich the Old of Kiev.

^ Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 098 – Kalka River 1223 – Genghis Khan’s Mongols invade Russia by D. Niccole, V. Shpakovsky and V. Korolkov (illustrator).

The Rusians, however, left their advantageous position by the Dnieper River to follow a trail of breadcrumbs intentionally left behind by the Mongols. For nine days the Rusian-Polovtsian confederacy pursued the Mongols before reaching the vast open plain encompassing the area around the Kalka River. This luring tactic, which was common among steppe nomads, is called the ‘Dogfight tactic’, but is known more commonly as the ‘feigned retreat’. Steppe nomads would lure the enemy into hopeless pursuits, into ambushes or towards locations which swayed the advantage in their favor. The Mongols lured the Rusian-Polovtsian confederacy like the famed Scythian king of old named Idanthyrsus who led the Persian king Darius the Great for a month deep into Scythian territory as far as the Volga River (in modern Russia) in 513 BCE.

“Even if the Tartars retreat, our men ought not to separate from each other or be split up, for the Tartars pretend to withdraw in order to divide an enemy.” – Giovanni of Pian del Carpine (c.1185–1252 CE).

“It should be known that when they come in sight of the enemy they attack at once, each one shooting three of four arrows at their adversaries; if they see that they are not going to be able to defeat them, they retire, going back to their own line. They do this as a blind to make the enemy follow them as far as the places where they have prepared ambushes. If the enemy pursues them to these ambushes, they surround and wound and kill them. Similarly if they see that they are opposed by a large army, they sometimes turn aside and, putting a day’s or two days’ journey between them, they attack and pillage another part of the country and they kill men and destroy and lay waste to land. If they perceive that they cannot even do this, then they retreat for some ten or twelve days and stay in a safe place until the army of the enemy had disbanded, whereupon they come secretly and ravage the whole land.” – Giovanni of Pian del Carpine (c.1185–1252 CE).

^ The Polovtsians (Cumans, western Kipchaks). Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 098 – Kalka River 1223 – Genghis Khan’s Mongols invade Russia by D. Niccole, V. Shpakovsky and V. Korolkov (illustrator).

“And ye shall understand that it is a great dread for to pursue the Tatars if they flee in battle … for in fleeing they shoot behind them and slay both men and horses. And when they will fight they will shock them together in a plump…” – Sir John Mandeville.

“If you are obliged to retreat, let the front of your whole party fire and fall back, till the rear hath done the same, making for the best ground you can; by this means you will oblige the enemy to pursue you, if they do it at all, in the face of a constant fire.” – The 28 Rules of Ranging by Robert Rogers. Rule 9.

“He will win who knows when to fight and when not to fight.” – The Art of War by Sun Tzu.

Polovtsian flight

Rus-Polovtsian coalition, despite being unified against a common foe, were rivalrous and constantly feuding throughout much of their history. Instead of fighting jointly, this uncoordinated and disorganized rabble of Slavic principalities and Turkish nomads were for the most part following their own individual tactical strategies. The Rusian and Polovtsian forces that rushed forward, far ahead of the remainder of their coalition, crossed the Kalka River to engage the Mongols. Those who were now on the Mongol side of the Kalka River plains were assaulted by an alternating cascade of arrows and heavy cavalry charges; echoing the disastrous Roman defeat by the Iranian Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae back in 53 BCE.

^ Osprey – ‘Warrior’ series, issue 084 – Mongol Warrior 1200-1350 by Stephen Turnbull and Wayne Reynolds (Illustrator). Plate F: Mongol Warriors in hand-to-hand combat at the battle of the Kalka River.

The surrounded and pummeled Rusians and Polovtsians broke and routed, the latter of which rushed toward the Kalka River but instead crashed into, trampled over and forced into the Kalka River the Rusians which were trailing behind them and just caught up with the initial Rus-Polovtsian vanguard.

^ To aid in understanding how the conflict went. Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 098 – Kalka River 1223 - Genghis Khan’s Mongols invade Russia by D. Niccole, V. Shpakovsky and V. Korolkov (illustrator).

“the Polovets men ran away back, having accomplished nothing, and in their flight they trampled the camp of the Russian Knyazes (princes), for they had not had time to form into order against them (Mongols); and they were all thrown into confusion, and there was a terrible and savage slaughter.” – Novgorod Chronicle.

Hilltop holdout

All but one Rusian force remained unbroken, that of Mstislav Romanovich the Old of Kiev, who had earlier suggested that they remain behind the Dnieper River. Mstislav Romanovich the Old of Kiev was trailing behind the rest of the confederates and saw that before he even reached the Kalka River that his comrades were obliterated and routed. Mstislav Romanovich the Old of Kiev quickly assembled a tabor or laager: fortifications made up of wagons drawn close together.

^ Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 098 – Kalka River 1223 – Genghis Khan’s Mongols invade Russia by D. Niccole, V. Shpakovsky and V. Korolkov (illustrator).

“Mstislav, Knyaz of Kiev, seeing this evil, never moved at all from his position; for he had taken stand on a hill above the river Kalka, and the place was stony, and there he set up a stockade of posts about him and fought with them from out of this stockade for three days.” – Novgorod Chronicle.

After being besieged for three days the Mongols promised that they would not shed their blood. Mstislav Romanovich the Old of Kiev surrendered but the Mongols were being smartasses since they intended on killing them in bloodless fashion. Since it was the tradition of the Mongols that they would not spill the blood of royalty or nobility, they organized a victory feast which was to be celebrated atop a platform (“bridge”) made of wooden planks. Mstislav Romanovich the Old of Kiev and the other princes were tied up and thrown under this platform. Here they suffered a slow and painful death from suffocation due to the immense weight and pressure the platform placed on them.

“And having taken the Knyazes they suffocated them having put them under boards, and themselves took seat on the top to have dinner. And thus they ended their lives.” – Novgorod Chronicle.

^ Osprey – ‘Campaign’ series, issue 098 – Kalka River 1223 - Genghis Khan’s Mongols invade Russia by D. Niccole, V. Shpakovsky and V. Korolkov (illustrator).

The Mongols hunted down the remnants of the Rus and the Polovtsians (Turks) back to the Dnieper River they initially crossed days ago, “the rest of the troops every tenth returned to his home”. The Mongols then crossed said river and entered into the land of the Rus who were vulnerable as they had just lost a vast army, nobles, princes and commanders. Just when it seemed like there would be a Mongol invasion, a campaign led directly against the Rus… they halted and returned to the steppes as Genghis Khan ordered them to join his son Jochi in a campaign against the Volga Bulgars (Muslim Turks).

“the Tartars turned back from the river Dnieper, and we know not whence they came, nor where they hid themselves again; God knows whence he fetched them against us for our sins.” – Novgorod Chronicle.

Head over to my post, “GENGHIS KHAN, THE STALLION WHO MOUNTS THE WORLD”, to read more about how Genghis Khan was pressured into campaigning out of China toward Central Asia (Kara Khitai Khanate), to Greater Iran (Khwarezmian Empire), to the frontier of Eastern Europe (Medieval Russia and Ukraine) and back to China. I also cover Mongol shamanism and their tolerance of foreign religions, the famed ‘Yam’ pony express, their tactical use of captives and their massive deportation policy.

To read up on the early history of the Mongols, check out my post ‘THE MONGOLS AND THE RISE OF GENGHIS KHAN’. In this post I speak about the Mongolian transition from seemingly insignificant tribal confederacies into an empire that was four times the size of Alexander’s and twice the size of the Roman’s. I cover their military tactics, some of their battle formations, armaments, their rapid adaptation of foreign technologies, and their secretive order of bodyguards known as the Keshik. During Genghis Khan’s early reign the Mongols warred against themselves and their fellow steppe neighbors as well as Northern China’s Western Xia dynasty (Tanguts: Tibeto-Burmese) and eastern Jinn dynasty (Tungusic Jurchens who were Sinicized).

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

The clouds serve him as battle banners.

The sky is his flag.

The wind sings his hymns.

Batu.

#mongol empire#mongol history#mongolia#the mongol empire#batu khan#batu#the golden horde#art#mongolian history

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

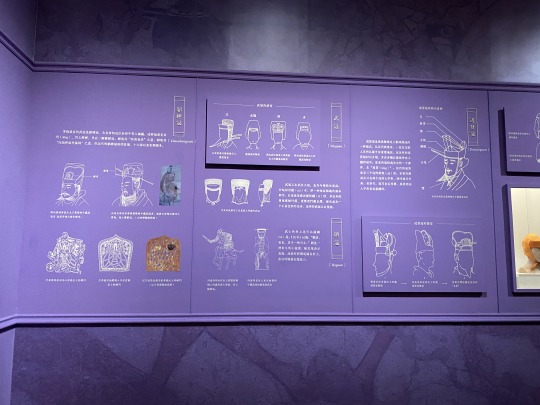

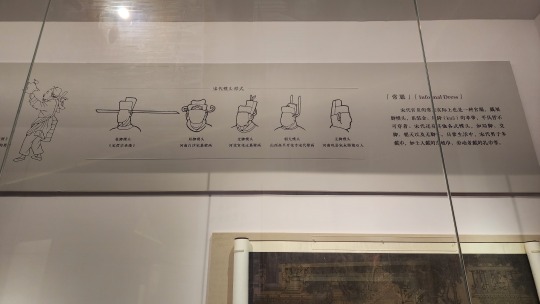

April 20, Beijing, China, National Museum of China/中国国家博物馆 (Part 3 – Chinese Historical Fashion Exhibition):

Another cool exhibition that I visited while at the museum, showcasing popular fashion from different dynasties, historical artifacts, and some other relevant artifacts that gave a glimpse into the fashion of different dynasties. What's even cooler is that you can visit this exhibition virtually! (the site is in Chinese but I highly recommend it to everyone, there's so much more to the exhibition than the pictures I post here) Note that this exhibition does not only include historical hanfu, but also historical fashion of the 少数民族 that ruled some of the dynasties. This post will be pre-Ming fashion, and next post will be Ming and Qing era fashion. The reason is because Ming and Qing dynasties are the two most recent dynasties, so there are a lot of surviving artifacts from these two dynasties, which means there are 30+ pictures total and I couldn't fit them all into a single post.

First is a recreation of Han-era (202 BC - 220 AD) hanfu. The woman on the left is wearing a one-piece robe called a qujushenyi/曲裾深衣. The man on the right is wearing the outfit characteristic of Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220 AD) civil officials, a combo of jinxianguan/进贤冠 hat and zaochaofu/皂朝服 clothing (皂 here means the color black, as in the word "青红皂白", or "blue and red, black and white"):

Left: model of a Han-era magpie tail cap/queweiguan/鹊尾冠 (you can see the influence of these Han-era men’s hats on the outfits of male characters in modern xianxia art). Right: recreation of a Han-era bian/弁 hat (the headscarf-like piece tied beneath the chin):

Line drawings of different hats worn by different types of officials based on artifacts and murals. The center and left sections are different hats of military officials (wuguan/武官 in Chinese), and the right section is different hat styles of civil officials (wenguan/文官 in Chinese).

Jumping back, this is a Warring States period (476 - 221 BC) iron daigou/带钩 inlaid with gold and jade and decorated with dragons. Daigou are basically belt buckles where the flat end is attached to one end of the belt, and the hook will hook into slits in the other end of the belt, so this is an extra fancy belt buckle:

On to Tang-era (618 - 907 AD) hanfu. From the left to right these are: the regular outfit of early Tang dynasty officials (color varies by rank, red is worn by fourth and fifth rank officials), the outfit of a female servant in early to mid Tang era, the ceremonial outfit of a Tang dynasty emperor, and the outfit of noblewomen in late Tang to Five Dynasties era (907 - 960 AD):

Song-era hanfu (front two) and Yuan-era Mongolian fashion (back two). Front left is the formal attire of Southern Song dynasty (1127 - 1279) civil officials (color varies by rank, red is worn by fourth and fifth rank officials), and front right is the regular outfit of women in Southern Song dynasty. Back left is the formal attire of Mongolian noblewomen in Yuan dynasty (1271 - 1368), and back right is the regular outfit of Mongolian men in Yuan dynasty.

Replicas of painted clay sculptures of women from Northern Song dynasty (960 - 1127), the original sculptures are in Hall of the Holy Mother/圣母殿 of Jinci Temple/晋祠 in Shanxi province:

By the way, in the case of Song dynasty, the descriptor "northern" and "southern" basically indicate time periods within Song dynasty (you can refer to the beginning of this post where I explain this in more detail).

And line drawing diagrams of different styles of futou/幞头 hats in Song dynasty based on paintings, murals, and other artifacts:

#2024 china#beijing#china#national museum of china#historical fashion#historical clothing#chinese historical fashion#hanfu#mongolian historical fashion#fashion history#chinese history#chinese culture#history#culture

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

the war hawk

because i need to write some more jagahatai. no cw for this one!

”Stand,” says the Great Khan from his throne, lounging like a true conqueror, safe in the knowledge of his victory. His gur is gigantic, larger than the cathedrals of your city home, and permits a great gathering of people — some his strange white-armoured sons, but mostly humans. They array in a circle around you, with no clear demarcation of rank, and none of the finery that the noble families of your home would display in such a gathering. You get the sense that they are all of one kin, a bond forged in the crucible of war. Perhaps if your own family had set aside its internecine struggles —

No. You cannot think like that. They didn’t. They lost. That is all there is.

You stand with the help of one of your attendants, schooling your face into careful, decorous blankness. You will not dishonour your family by weeping. Women of your family have married for politics for generations — yes, it has been centuries since any of your foremothers were offered up to a warlord in exchange for peace, but it is not your place to bemoan your fate. No: you must be thankful. You must wring gratitude from this misery, because no man found under the stars — or among them — will be charmed by a dour, shivering wretch.

“Yes, my Lord Khan,” you say. “Forgive me — I do not speak your tongue —“

“That is no matter,” he says. “I speak the language of this system well enough.”

Your maid gives you a swift, curious look, which you deliberately ignore — though you share her thoughts. The stories you both heard spoke of barbarian sheep-herders that tore books apart in anger because they could not read them.

“You honour our meagre home with your presence, my Lord,” you say, swooping into another curtsy. The clothing you wear is gorgeous, but highly impractical: a chain mail dress, ornamented with gemstones; a headdress anchored in place with hairpins that bite at your scalp. You wear the tribute, and you are the tribute. Gold, sapphires, precious metals, precious fuels — and livestock. The finest horses, cattle, sheep and poultry that your homeland has.

And you, of course. You who feel that you have more in common with the broodmares and fattened lambs in your entourage than with the crown on your head.

The Great Khan acknowledges your flattery only with the slight incline of his head. His throne is draped in so many furs you cannot see the original shape of it. It looks comfortable. To his left sits three of his sons, clad in their armour, but helmetless. To his right is an elderly man, a hood pulled over his head, so his face is shadowed. An advisor, maybe?

“Your father did not say this when he first met our envoys. We interpreted his broadcast. Sheepfuckers and misfits, he called us,” he says, idly, and your stomach drops into your feet. Instinctively, you pull your handmaids closer to you, grasping their chilly hands with yours.

“My father —“

“And in this letter he sent you with,” the Khan says, unfolding the parchment. It seems tiny in his gigantic hands. “He says that he is but — ‘a worm in the garden of my resplendence’ — he has quite the way with words, does he not? And such a change of heart! A modest man, to say he is but a worm in the garden of a sheepfucker.”

A few of his sons chortle; someone jeers. Your cheeks flame, and you lick your lips before replying.

“My father’s words were misspoken and arrogant.”

“Indeed. And he has learned the error of his ways. As long as he pays his tithes, he and his people will be treated as valued members of the Imperium — and under the protection of the Emperor of Mankind.”

The Great Khan turns back to the parchment, and makes a show of reading further.

“He has some words for you too.”

You swallow thickly. Your mother had been all careful posed dignity when she sent you away; your father had embraced you and wept. His first child; his first girl. His eldest. Sacrificing so much for the sake of her people —

“‘—though she is no great beauty, and is altogether too clever, she is swift to learn, and her mother bore eight children, four of whom were boys, so it is likely that she will likewise be fertile,’” the Khan reads, and something inside you freezes. There are no chuckles now — even if there had been, you would not have heard them over the strange high ringing in your ears. Your fingernails dig into the back of your handmaid’s hand, leaving bloody red crescents; she does not seem to notice; or if she does notice, she does not care. “And if she is not to your liking then rest assured she has sisters, who are fairer and younger and —“

“Don’t you dare!” you shout, without thinking, without considering and — oh by the gods what have you done? And then you remember that these strange men from the stars burn churches and despise worship, and so calling on the gods just makes things worse — and you freeze, heart rabbiting, eyes wide. “I mean, my lord, please — the next-oldest of my sisters is sixteen summers —“

You were born to be a politician — bred to be one — and yet all of your training has been for nothing, for in that moment you are not a diplomat but a sister, white-hot fury pulsing behind your eyes. If you had talons, you’d rip your fathers face from his skull; if you had wings, you’d pull your sisters and handmaids under their span, tuck them safe and secure and hidden. But you have neither: only a clumsy tongue, and rage that stoppers your throat, and grief great enough to drown in. And all the while the Khan watches you, impassive as a hawk; a great predator, with no concern for the mewling of women —

“Jaghatai,” says the cloaked figure to his right, pulling her hood back. “You’re scaring the girl.”

What you had assumed to be a withered old man is in fact a withered old woman, with nut-brown skin, heavy black hair, and bright eyes glittering in folds of corrugated flesh.

“I am — ah,” says the Great Khan, and then his face relaxes minutely. He smiles — though the gesture does nothing to calm you, directed as it is at the woman. “Apologies.”

“Don’t apologise to me, Khan — apologise to your poor bride! Soldiers! Really!”

She stretches like a cat, her joints clicking, and stands. Three of the astartes hasten to help her down the dais, but she waves them away.

“I can manage just fine on my own, boys,” she says, and hobbles her way down to you. She’s barely up to your shoulder, hunched over with age; her clothes are of fine quality, but thoroughly worn. “Honestly.”

“My lady Hoelun — “ one of the men says, but she points her stick at him.

“Tsubodai, I knew you when you were stumbling around after your father’s goats — when I need your help, I shall ask for it. All of you! Useless!”

Instinctively, you curtesy to her. She chuckles, and catches your chin with one gnarled hand.

“Let’s have a look. All your own teeth, no mutations,” she says, tipping your face this way and that. “Clever, that letter said, and I’ll believe that — every woman we’ve met in this system can read and write, which is a blessing, believe me. Half of my grandsons are still learning. They like their bikes and their ponies, what do they need letters for?”

She pinches your cheek.

“Smart, because you knew how to greet the Great Khan. And reckless brave, because you shouted at him. And —“ She looks down at your hands, which still clutch at your whimpering maids. Her gummy smile widens. “And decent too.”

She turns back to the Great Khan.

“You’ll marry this one, Jaghatai. I’ll make the arrangements for the ceremony in two moons time. Until then, we’ll follow tradition.”

The Great Khan does not seem at all surprised at the display. His smile has deepened, and for the first time he looks more like a man than a hunting bird.

“Very well, Mother,” he says. “If you approve — my lady, you will be granted your own household, and a gur large enough to hold them. You may bring women to attend you from your home planet if you wish — or if you prefer, I can name some from within my own family. A hundred head of horse are yours as of today; for each week until our wedding another hundred shall be added to your herd. You will learn our language and our customs, and you will sit in on my council with my mother —“

“My lord — I am no warrior,” you say, and he holds up a hand to silence you.

“No. But I am no politician. An empire can be conquered from the saddle of a horse, but not ruled from one. You will attend council with my mother and learn from her, so that when we are wed you may pick up the governance of this sector in my absence.”

“But — my father is the governor,” you say, brow furrowed, still feeling like you are stumbling to catch up. Hoelun chuckles.

“For now. But who trusts a man who puffs up his chest only to crawl in the dirt with nary an arrow fired?”

The implication of her words should horrify you. You think of your sisters, and you feel only a hesitant, fragile kindling of hope. Hoelun gives your cheek another affectionate — if slightly painful — squeeze.

“Welcome home,” she says.

#my writing#jaghatai khan/reader#this borrows from mongolian history but you know an au where everyone in the khanate wasn’t awful#hoelun was genghis khans mother so in this she is jaghatai’s#because why should roboute be the only one with a functioning maternal figure

91 notes

·

View notes