#former jurchen empire

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pop culture Chinggis Khaan: "I am the Wrath of Heaven, and my destiny is to conquer the entire world, so I will invade China and Persia at the same time!"

Actual Chinggis Khaan: "Ugh, that asshole massacred my trade caravan, so now I have to schlep all the way to Khurasan to go slap his nephew. Muqali, Alaqai, keep up the pressure against the Jin while I'm out in the west. Xuanzong has got to realise he's outclassed and accept becoming our vassal one of these days, right? Right?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Biography: Scorpion

Birthname: Xiejie Liubo (蝎揭留波) Goes by: Scorpion, Scorpion King, Xiezi, Duxie Ethnicity: Half-Han, Half-Nanman Age: 19 Known Family Members: Former Ghost Valley’s Master (father, deceased, killed by Wen Kexing) Unnamed Princess, Khatun (mother, deceased, died from illnesses after the death of her clan by Han people)

Note

Since Scorpion barely showed up in the novel, the portrayal on this blog would be exclusively from Shan He Ling / Word of Honor. Although I might throw in elements from Lord Seventh and the novel from time to time.

Background

Xiejie Liubo is the son of the Old Ghost Valley’s Master and a Khatun, a Jurchen princess. It started with a chance meeting between the two — until the death of her khanate, to her death, the Khatun still did not know that she was lied to, that the man whose son she carried not was a emperor or even a prince. At least, he wasn’t recognized by the then ruling Helian Empire as royalty.

While he was born and spent most of his life in the Northeast, Scorpion’s mother died when he was very young, but he matured at a young age. By the age of 4, he could talk to scorpions and by age 8 he has already become well-versed in the art of Sorcery and has become a well-known Shaman among his tribe. Upon the death of his mother from being bedridden with illnesses, she told him to seek for his father, who was a prince, in the western capital Chang’an. Scorpion, however, never found his true biological father, but he eventually discarded the idea of looking for his biological father after he was saved by Zhao Jing and adopted by him at age 11, henceforth dedicating his entire life and purpose to help Zhao Jing achieve his goals.

The Scorpions (蝎子) in his assassin organization were all people he had brought to the west from what remained of his mother’s khanate. They, just as him, were well-versed in the art of dark sorcery and knew their way around poisons and venoms well. The Scorpions all calls him King of Scorpions (蝎王), recognizing him as his mother’s successor and heir.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Wall of China. More images on my blog, link below. My blog has descriptions attached to the images also.

"The Great Wall of China (traditional Chinese: 萬里長城; simplified Chinese: 万里长城; pinyin: Wànlǐ Chángchéng, literally "ten thousand li wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic groups from the Eurasian Steppe. Several walls were built from as early as the 7th century BC, with selective stretches later joined by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China. Little of the Qin wall remains. Later on, many successive dynasties built and maintained multiple stretches of border walls. The best-known sections of the wall were built by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Apart from defense, other purposes of the Great Wall have included border controls, allowing the imposition of duties on goods transported along the Silk Road, regulation or encouragement of trade and the control of immigration and emigration.

The Chinese were already familiar with the techniques of wall-building by the time of the Spring and Autumn period between the 8th and 5th centuries BC. During this time and the subsequent Warring States period, the states of Qin, Wei, Zhao, Qi, Han, Yan, and Zhongshan all constructed extensive fortifications to defend their own borders. Built to withstand the attack of small arms such as swords and spears, these walls were made mostly of stone or by stamping earth and gravel between board frames.

King Zheng of Qin conquered the last of his opponents and unified China as the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty ("Qin Shi Huang") in 221 BC. Intending to impose centralized rule and prevent the resurgence of feudal lords, he ordered the destruction of the sections of the walls that divided his empire among the former states. To position the empire against the Xiongnu people from the north, however, he ordered the building of new walls to connect the remaining fortifications along the empire's northern frontier. "Build and move on" was a central guiding principle in constructing the wall, implying that the Chinese were not erecting a permanently fixed border.

Transporting the large quantity of materials required for construction was difficult, so builders always tried to use local resources. Stones from the mountains were used over mountain ranges, while rammed earth was used for construction in the plains. There are no surviving historical records indicating the exact length and course of the Qin walls. Most of the ancient walls have eroded away over the centuries, and very few sections remain today. The human cost of the construction is unknown, but it has been estimated by some authors that hundreds of thousands of workers died building the Qin wall. Later, the Han, the Northern dynasties and the Sui all repaired, rebuilt, or expanded sections of the Great Wall at great cost to defend themselves against northern invaders. The Tang and Song dynasties did not undertake any significant effort in the region. Dynasties founded by non-Han ethnic groups also built their border walls: the Xianbei-ruled Northern Wei, the Khitan-ruled Liao, Jurchen-led Jin and the Tangut-established Western Xia, who ruled vast territories over Northern China throughout centuries, all constructed defensive walls but those were located much to the north of the other Great Walls as we know it, within China's autonomous region of Inner Mongolia and in modern-day Mongolia itself."

-taken from wikipedia

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Why did the Mongols invade most of the Old World?"

A write up I did on Reddit for a question: "what caused the Mongols to invade most of the Old World?"

It was almost accidental. At no point when he began uniting the Mongol tribes did Chinggis Khan (the more accurate rendition of Genghis Khan) seek out world domination. Rather, it sort of kept happening.

What people don't realize is that Chinggis Khan didn't succeed in uniting the Mongols until he was about 50, declaring the Mongol Empire in 1206 (he was born in 1162 as Temujin, and it wasn't until 1206 when he began being called Chinggis). That was many decades of slow warfare and his own losses and defeats before he succeeded in doing so. Initially he was probably concerned only in securing his own position and safety, perhaps at best hoping for leadership of his own tribe. Events went differently, and a 'concerned citizens' alliance of steppe notables unhappy with Temujin's rise (such as appointing his generals and chief lieutenants from common folk based on their ability, rather than old bloodlines) turned the conflict into a massive civil war for control of Mongolia. By this time this was complete, Temujin had restructure Mongolian society, breaking the power of tribal Khans and old tribal ties, placing himself, the Great Khan, at the head, with discipline and utter loyalty the byword, harnessing the great military potential of the steppe horse archer.

By 1206 then he had a fierce military force, a great spear: but had almost run out of enemies in Mongolia itself. All dressed up and nowhere to go, you might say. What Chinggis Khan understood was that he needed a common enemy, or old internal intrigues would rise back up to the surface and tear his new union apart. The spear needed to be thrown, lest it fall apart. The obvious answer lay to the south, the kingdoms of northern China, the Tangut Xi Xia in modern Gansu/Ningxia, and the Jurchen Jin Dynasty controlling from Manchuria to the Huai River, capital at Zhongdu (modern Beijing). Whether Chinggis at this stage was intending to conquer them, or attack and raid is hard to say. Personally, his actions to me suggest the latter, but some argue for the former. There certainly were pretexts to attack both. The Tangut had allowed certain enemies of Chinggis to flee through their territory or seek shelter, and the Jin had long been enemies of the Mongols, breaking up an earlier Mongol union (commonly called the Khamag Mongol confederation) in the early 12th century. While there certainly was this pretext, it should also be noted that a quite dry period in late 12th century Mongolia, and continuous warfare, had depleted the herds the Mongols relied on to survive as well as cost them in other goods. The raids, especially against the Xi Xia, may have just been out of need to replenish these stocks. Part of this too may have been encouraged by both states entering into a period of instability and poor emperors: as good an opportunity as any for the Mongols to attack. If they had aspirations beyond this, I don't think we can say, and it seems highly unlikely to me. Chinggis Khan's intentions here seem very localized.

In 1209 the Mongols invaded the Tangut Kingdom, making off with a great quantity of goods and forcing the Tangut King to submit to them (which entailed him sending a massive amount of tribute and slaves). Not long after his return from the Xi Xia, the Jin Emperor demanded the submission of Chinggis Khan (Temujin had undertaken a formal vassalization to the Jin in the past, and the Jin may have been surprised by his sudden unification of the steppes and understandably worried, but were distracted by war with the Chinese Song Dynasty to the south), who insulted the envoys and used this as his official declaration of war, invading the Jin Empire in 1211.

I think what turned Chinggis' mind to more permanent conquest than he initially intended was the success the Mongols had. While sieges were difficult, but aided by Jin defectors providing them siege weapons and knowledge, Chinggis Khan's army absolutely devastated in almost every field encounter. Though the Jin had mighty horsemen and huge numbers, they were unable to gain local superiority of forces and suffered from defections after defections. Within a few years, there were more Chinese fighting for the Mongols against the Jin that there were Mongols there!

By 1215, Zhongdu had fallen (with some difficulty), and forced the Jin Emperor to supply tribute and Chinggis withdrew back to Mongolia, but when the Emperor soon broke this agreement by fleeing to Kaifeng, war resumed. Was Chinggis intending a conquest of all of China now? Well, still it is not quite clear whether his intentions were to force the Jin to submit, fully conquer them or take all of China. I personally have seen no evidence he desired all of China yet, and the Jin were still a major obstacle. I think his intentions did not go much beyond forcing the Jin to be his vassal.

While in Mongolia in 1216, Chinggis sent some forces to bring rebellious tribes in Siberia and the steppe west of Mongolia to heel, as well as hunt down a son of a defeated enemy, Kuchlug, who had usurped power in the Qara-Khitai empire (parts of western Xinjiang/Kazakhstan). This was a major concern as Chinggis feared Kuchlug could use this as a staging ground to invade Mongolia, and when Kuchlug attacked and killed a Mongol vassal at Almaliq, sent his general Jebe to bring Kuchlug to heel. Chinggis had actually overestimated how secure Kuchlug's rule was though, as it turns out Kuchlug was greatly hated. Kuchlug's empire dissolved and submitted to Jebe as he passed through, and Kuchlug was finally hunted down in Badakhshan. In a flash, the Mongol Empire had greatly and unexpectedly expanded to the west: intended to finally capture a dangerous enemy, they had ended up incorporating a huge swath of new territory, making them neighbours with the also expansionist Khwarezmian Empire, which ruled from Transoxania through Persia.

Chinggis' initial contacts with Khwarezm were though, entirely trade focused. He sent envoys and merchants to establish trade links with the Khwarezm-Shah, Muhammad: together, their two empires could have secured a significant amount of the trade in and out of China, providing a safe route between both states. I want to really emphasis this: Chinggis Khan's first contacts with a state not immediately adjacent to Mongolia or encountered in Northern China were to encourage trade, wholly economic. Nothing suggests at this initial stage Chinggis intended to conquer or attack Khwarezm.

Of course, we know things didn't go quite so smoothly: I have a video providing overview here: https://youtu.be/0ct-dz_ad4k. Basically, a large trade caravan sent by Chinggis was betrayed and murdered by the governor of the frontier city of Otrar (the Khwarezm-shah's uncle). But even after this, do you know what Chinggis Khan did? He sent a group of envoys to find out why this had occurred, and give the Khwarezm-shah a chance to make recompense. Even after such a heinous assault, Chinggis Khan did not want to uproot his armies and move west, and still gave the Shah a chance to encourage trade. When the Shah insulted and killed these envoys, that was what finally brought Chinggis Khan to, perhaps reluctantly, invade the Khwarezmian Empire.

It seems Chinggis Khan greatly overestimated the Khwarezmians. On paper, they had immense military potential, and Chinggis Khan being unfamiliar with the Qara-Khitai realm he had now incorporated, may have been unaware had difficult it would have been for the Khwarezmians to mount an offensive towards Mongol territory. There had also been a brief engagement between Mongol (under Chinggis' son Jochi and the famed Subutai) and Khwarezmian forces in similar time to this, while the Mongols had been pursuing fleeing Merkit seeking shelter among the Qipchaq. What had not been apparent was how politically fragile the Khwarezmian Empire was, how most of its territory was only newly acquired, the ethnic tensions (Turkic garrisons and commanders vs Persianized populations) which hampered cooperation and how the over-confident Khwarezm-Shah Muhammad was simply not up to the task at hand. When Chinggis Khan's armies entered the Khwarezmian Empire at the end of 1219 (leaving a holding force in China under the commander Mukhali to keep up pressure there), the Khwarezm-Shah fled, leaving each city to fend for itself. Totally unexpectedly, but from late 1219 to the end of 1221, the Khwarezmian Empire utterly dissolved under a ferocious Mongol onslaught. Notable resistance came from a few individuals, like the Shah's son, the brave Jalal al-Din Mingburnu, but it must have been an absolute shock to the Mongols how total their victory was. It is here it seems the belief in Mongol world domination must have truly emerged. Basically, to paraphrase historian David Morgan, the Mongols came to believe they were destined to conquer the world when they realized that they were in fact, doing so. For how else could you have explained such a dramatic victory?

The Khwarezmian campaign laid the foundations for further Mongol campaigns in the west: during that campaign, Jebe and Subutai went on a phenomenal campaign through the Caucasus and into southern Russia, defeating a Rus'-Qipchaq force at the Kalka River in May 1223, bringing to the Mongols knowledge of the western steppe and to Subutai, a personal interest to return there. Continued campaigns to conquer and consolidate the remnants of the Khwarezmian realm brought the Mongols deeper into Persia and Iraq. In China, the brief respite allowed the Jin dynasty to hold on until 1234, which brought the Mongols into contact with the Southern Song Dynasty and their own eventual wars there.

The vast scale of the Mongol conquests was not something intended from the outset, but a staggered development, and as more and more of Asia came under their banner, the Mongols would become much more proactive in the spread of their rule.

Sources:

Allsen, Thomas T. “Mongolian Princes and Their Merchant Partners, 1200-1260.” Asia Major 2 no.2 (1989): 83-126.

Atwood, Christopher. “Jochi and the Early Campaigns.” in How Mongolia Matters: War, Law, and Society, edited by Morris Rossabi. Brill's Inner Asian Library, (2017) 35-56.

Barthold, W. Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion. Translated by H.A.R. Gibb. London: Oxford University Press, 1928. https://archive.org/details/Barthold1928Turkestan/page/n341

Biran, Michal. The Empire of Qara-Khitai in Eurasian History: between China and the Islamic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Buell, Paul D. “Early Mongol Expansion in Western Siberia and Turkestan (1207-1219): a Reconstruction.” Central Asiatic Journal 36 no. ½ (1992): 1-32.

Golden, Peter B. “Inner Asia c. 1200,” in The Cambridge History of Inner Asia: The Chinggisid Age, edited by Nicola Di Cosmo, Allen J. Frank and Peter B. Golden, 9-25. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Jackson, Peter. The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

May, Timothy. The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires Series. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Sinor, Denis. “The Mongols in the West.” Journal of Asian History, 33 no. 1 (1999): 1-44.

Timokhin, Dmitry. “The Conquest of Khwarezm by Mongol Troops (1219-1221).” in The Golden Horde in World History, 75-86. Tartaria Magna Series. Kazan: Sh. Marjani Institute of History of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences, 2017.

Timokhin, Dmitry, and Vladimir Tishin. “Khwarezm, the Eastern Kipchaks and Volga Bulgaria in the Late 12-early 13th Centuries,” in The Golden Horde in World History, 25-40. Tartaria Magna Series. Kazan: Sh. Marjani Institute of History of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences, 2017

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

40 Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About 안전한놀이터주소 #2954

Most games feature 'power-ups' which give individual players an advantage on winning the game when using such power-ups. In the 22 October 1966 episode ("Odds on Evil") of the Mission: Impossible series, the IMF team uses a wearable computer (à la Thorpe and Shannon, above) to predict the outcome of each spin of the roulette wheel at a fictional casino in a European principality. This second picture on the right is of the Spanish suits. For example, the "clubs" of the Spanish suit are usually more "natural" than Italian "clubs". The Spanish "cups" are designed differently from the Italian "cups". However, both the Italian and the Spanish suit symbols are similar enough to have playing card scholars give them the collective name - the Latin Suits. Within Spain, there are many regional differences which are reflected in the decks of cards for sale - regional differences indicate which suit symbols and pictures are used on a deck, i.e. - Adaluza, Aragonesa, Bartolome, Basche, Catalunya, Espagnole, Galicia. Since the Spainish empire included Mexico and Latin America, Spanish suited cards can be found in use in these countries today. The United States introduced the joker into the deck. It was devised for the game of euchre, which spread from Europe to America beginning shortly after the American Revolutionary War.

However, more frequently tips are given by placing a bet for the dealer. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/?search=메이저놀이터추천 Any automated card shuffling device or automated dealing shoe shall be removed from a gaming table before any other method of shuffling or dealing may be utilized at that table. Players wishing to bet on the 'outside' will select bets on larger positional groupings of pockets, the pocket color, or whether the winning number is odd or even. The payout odds for each type of bet are based on its probability. Most often, this is done either by telling a dealer to place a specific bet "for the boys" -- bets on 11 or the field are among frequent choices -- or by placing a bet on one of the "hard ways" and telling the dealer it goes both ways.

If you’d like to practice some of these Caribbean Stud Poker strategies or want to get a feel for the game before actually risking any money, there are many places online where you can do it for free. In fact, the word "Kanjifah" appears in Arabic on the king of swords and is still used in parts of the Middle East to describe modern playing cards. Influence from further east can explain why the Mamluks, most of whom were Central Asian Turkic Kipchaks, called their cups tuman which means myriad in Turkic, Mongolian and Jurchen languages.Wilkinson postulated that the cups may have been derived from inverting the Chinese and Jurchen ideogram for myriad (万). Hand craftsmanship and high taxation made each deck of playing cards an investment. As such, cards became a feast for the eye. If hop bets are not on the craps layout, they still may be bet on by players but they become the responsibility of the boxman to book the bet.

He is sitting on a block of stone on which are carved hieyroglyphics and is surrounded by instruments or products of the Arts. The former Dairy Factory (now an Auto workshop) on Route de Merviller (1930) Even though a slot may have a modest house advantage from management’s perspective, such as 4 percent, it can and often does win all of George’s Tuesday night bankroll in short order. 스포츠중계 If the casino allows put betting a player may increase a Come bet after a point has been established and bet larger odds behind if desired. Put betting also allows a player to bet on a Come and take odds immediately on a point number without a Come bet point being established.

Caribbean Stud Poker is a five card stud poker game played on a blackjack type table with a standard 52 card deck. Three may also be referred to as "ace caught a deuce", or even less often "acey deucey". They netted £1.3m in two nights.[15] They were arrested and kept on police bail for nine months, but eventually released and allowed to keep their winnings as they had not interfered with the casino equipment.Not all casinos are used for gaming. The Catalina Casino, on Santa Catalina Island, California, has never been used for traditional games of chance, which were already outlawed in California by the time it was built.[4] The Copenhagen Casino was a Danish theatre which also held public meetings during the 1848 Revolution, which made Denmark a constitutional monarchy.

This is usually done one of three ways: by placing an ordinary bet and simply declaring it for the dealers, as a "two-way", or "on top". A "Two-Way" is a bet for both parties: for example, a player may toss in two chips and say "Two Way Hard Eight", which will be understood to mean one chip for the player and one chip for the dealers. The probability of getting heads in a toss of a coin is 1/2; the odds are 1 to 1, called even. Care must be used in interpreting the phrase on average, which applies most accurately to a large number of cases and is not useful in individual instances. If a hand consists of two tiles that do not form a pair, its value is determined by adding up the total number of pips on the tiles and dropping the tens digit (if any). Examples:Gaming machines are by far the most popular type of casino activity.

Single rolls bets can be lower than the table minimum, but the maximum bet allowed is also lower than the table maximum. The maximum allowed single roll bet is based on the maximum allowed win from a single roll. Sometimes players may request to hop a whole number. Casinos that reduce paytables generally have to increase promotions to compensate and attract customers.The machines also dispensed tokens meant to be exchanged for drinks and cigars before pumping out actual coins in 1888.

France boasts many of the most famous European casinos, including those at Cannes, Nice, Divonne-les-Bains, and Deauville. Since 1962 there are more than a hundred books written explaining how card counting works. Essentially, when you split in blackjack it increases your number of opportunities to win.Where commission is charged only on wins, the commission is often deducted from the winning payoff—a winning $25 buy bet on the 10 would pay $49, for instance. The house edges stated in the table assume the commission is charged on all bets.

0 notes

Photo

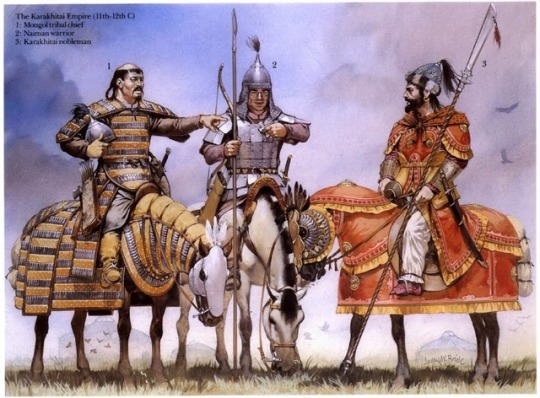

THE MONGOLS UNDER GENGHIS KHAN WAR AGAINST THE TURCO-MONGOL REALM OF KARA KHITAY, 1216–1218 CE:

The following is an excerpt from my post, “GENGHIS KHAN, THE STALLION WHO MOUNTS THE WORLD”.

The Turkish and Mongolian religion of Tengrism was a combination of ancestor worship, shamanism, animism (the belief that natural objects, natural phenomena, and the universe itself possess souls) and totemism (belief in kinship with or a mystical relationship between a group or an individual and a totem (a natural object or an animate being, as an animal or bird, assumed as the emblem of a clan, family, or group).

For the most part it was polytheistic (“many gods”) as they believed in many spirits and deities but some followers were monotheistic (“single god”) since they held Tengri, or ‘Munkh Khukh Tengri’ (“Eternal Blue Sky”), as their supreme god. Mongolians refer to Mongolia as ‘Munkh Khukh Tengriin Oron’, “Land of Eternal Blue Sky”. Although Tengrism was common place among the Turks and Mongols, they didn’t expect others to follow their religion. Only their supreme god Tengri could truly judge whether a man was righteous enough or not, despite one’s religion.

“We believe that there is only one God, by whom we live and by whom we die, and for whom we have an upright heart. But as God gives us the different fingers of the hand, so he gives to men diverse ways to approach Him.” – Mongke Khan (Fourth Khan, 1251–1259) during a religious debate in court. According to William of Rubruck (May 31, 1254).

“…Your saying ‘May [the Ilkhan] receive silam (baptism)’ is legitimate. We say: 'We the descendants of Genghis Khan, keeping our own proper Mongol identity, whether some receive silam or some don’t, that is only for Mongke Tengri (Eternal Heaven) to know (decide).’ People who have received silam and who, like you, have a truly honest heart and are pure, do not act against the religion and orders of the Eternal Tengri and of Misiqa (Messiah or Christ).

Regarding the other peoples, those who, forgetting the Eternal Tengri and disobeying him, are lying and stealing, are there not many of them? Now, you say that we have not received silam, you are offended and harbor thoughts of discontent. [But] if one prays to Eternal Tengri and carries righteous thoughts, it is as much as if he had received silam.” – From a letter sent from Arghun Khan of the Mongol Ilkhanate (1284–1291 CE) to Pope Nicholas IV (written May 14th, 1290).

Many steppe factions had already taken on other religions like Islam, Nestorianism (Christianity), Buddhism, and Manicheism. Their subjects were free to practice their religion, culture and laws but the Mongolian ‘Great Yasa’ (code of laws) came first. As Genghis Khan sought to unite his nation, he made it clear that people would be judged by their loyalty, diligence and skill rather than their lineage, ethnicity, culture and religion.

^ Osprey – ‘Men-at-Arms’ series, issue 295 – Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590–1260 AD by CJ Peers and Michael Perry (Illustrator). Plate H: A Liao Council of War. H1: Khitan ordo cavalryman – “The famous Wen Ch’i scroll depicts a party of these ‘barbarians’ in the act of looting a Chinese house. It is thought that the scroll is based on an original of the Sung period, and that the models for figures were Khitan warriors. This man has removed his helmet, showing the soft cap worn underneath. He carries a mace as prescribed in the Liao Shih and illustrated in tomb paintings. Also carried were bows, spears and halberds. Jurchen, and even Mongol heavy cavalry, would have looked very similar. This source shows coats in various shades of brown, and trousers as brown or blue. The Jurchen favored bright colours such as red, yellow and white, and made much use of animal skins and furs. They arranged their hair in a pigtail and, like the later Manchus, imposed this style on their Chinese subjects as a sign of submission. Guards at the Kin (Jinn) court are said to have worn red or blue cuirasses, probably of lacquered leather.” H2: General – “This man is wearing a spectacular suit of gilded armour as depicted in the Wen Ch’i scroll, is obviously as high-ranking officer. On the scroll there are unarmoured figures shown in attendance, carrying pieces of his armour. They may therefore represent the ‘orderlies’ or ‘foragers’ who fought as lightly equipped cavalry in the Liao armies.” H3: Mongolian auxiliary.

Back in 1125 CE the Khitan (Sinicized Mongolians) Liao dynasty of northern China was overthrown and taken over by the Jurchens (Tungusic peoples who established the Jinn dynasty). From then on the Khitans lived primarily in what is now Manchuria (northern China, bordering modern Mongolia) but a portion of the Khitan under Yelu Dashi of the Liao dynasty fled westward over the Tien mountains into Central Asia where they were joined and augmented by neighboring Turkish tribes. The khanate they established became known as Kara Khitay (“Black-Cathay”) and encompassed modern Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, southern Kazakhstan and western China (Xinjiang).

Before warring with the Western Xia, Genghis Khan defeated the Naimans which were under the leadership of a man named Taibuqa who was their Tayang Khan. After Taibuqa Tayang Khan was killed, his son Kuchlug fled to Central Asia in 1208 CE where he met the Gur-Khan (Chief of Khans) of the Kara Khitan Khanate who welcomed him as they often did to Turkish and Mongol refugees. Kuchlug became the Gur-Khan’s adviser and in time married a daughter of his; his goals, however, were set much higher. The Shah of the Khwarezmian Empire (Turco-Persian) was already at war with the Gur-Khan of Kara Khitay so in 1211 CE Kuchlug allied himself with the shah, agreeing to split the khanate between the two of them. Eventually the Gur-Khan of Kara Khitay was captured, Kuchlug usurped the throne and the western portion of his new empire was given to the shah as promised.

^ Kara Khitay khanate c.1200 CE.

Now many steppe factions such as the Naimans, Kerayits, Merkits and the Mongols practiced Tengrism with mixtures of Tibetan Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity (Church of the East) and/or Manicheism (Persian religion dating back to the third century CE, dualistic belief in a war between good and evil. Christian and Gnostic influence). Kuchlug practiced Nestorian Christianity but was converted to Buddhism at the behest of his wife (the former Gur-Khan’s daughter). Kuchlug began to fear, and rightfully so, the shah and his rapidly expanding Islamic realm of Khwarezmia.

If the shah were ever to turn against Kuchlug, would Kuchlug‘s subjects (the majority of which were Muslim) side with the Kara Khitay or with the Islamic shah of Khwarezmia who claimed to be the ’Shadow of God on Earth’, Iskander (Alexander the Great), and the ‘Chosen Prince of Allah’. Kuchlug became Islamophobic and began a forced conversion policy in which his subjects had to either convert (to Buddhism or Nestorian Christianity) or begin donning Khitan garb. Kuchlug also banned public worship and calls to prayer.

“After Kuchlug had conquered Kashghar and Khotan and had abandoned the law of Christianity for the habit of idolatry, he charged the inhabitants of these parts to forsake their pure Hanafite faith for unclean heathendom, and to turn from the rays of the light of Guidance to the wilderness of infidelity and darkness, and from allegiance to a merciful King to subservience to an accursed Devil. And as this door would not give way, he kicked it with his foot; and by force they were compelled to don the garb and headdress of Error: the sound of worship and the iqamat was abolished and prayers and takbirs were hushed.” – Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini (1226–1283 CE), Persian historian and governor of Baghdad.

When Kuchlug left his capital of Balasagun, it rebelled and shut the gates to him. Kuchlug Gur-Khan then besieged it and, once captured, he razed the city. Due to his religious policies the city of Kashgar rebelled in 1213 CE, in response Kuchlug burned their harvest which led to severe starvation within the city. There was also an imam in the city of Khotan which criticized and embarrassed Kuchlug so he had the imam crucified to the door of said imam’s madrasa (Islamic educational institution).

“they crucified him (the imam) upon the door of his school which he had built in Khotan” – Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini (1226–1283 CE), Persian historian and governor of Baghdad.

^ Where Kuchlug’s capital of Balasagun once stood there are now only ruins, most popular are the remains of a 82 ft. tall (originally 148 ft. tall) minaret known as the Burana Tower which stands like an eerie echo of the past.

As a continuous flow of anti-Genghis nomads traveled to the Kara Khitay Khanate, the possibility of the Great Khan turning his gaze at the threat posed by his old foe’s growing power was inevitable. While Genghis was occupied campaigning against the Jinn dynasty of northern China, he had no interest in the Kara Khitay Khanate until Kuchlug made the great mistake of besieging the city of Almaliq, which were vassals of the Mongols. In response to the pleas of the cities of Balasagun, Kashgar, and Almaliq, Genghis decided to focus his attention towards this distant foe.

Genghis Khan sent Jebe, a general renowned for his skill in rapid and deep infiltrative operations, to invade the realm of Kara Khitay, execute Kuchlug, abstain from harming any one not allied with Kuchlug and spread the word that under Mongol rule all subjects would be allowed freedom of worship. Throughout Kara Khitay the settlements which were predominantly populated by Muslims massacred any pro-Kuchlug forces, voluntarily opening their gates to Jebe and sided with the Mongols. Kuchlug was caught, beheaded, had his head placed on a pole and then paraded.

Genghis’ promotion of meritocracy allowed him to easily place trust in his generals since he knew they were skilled and experience enough to act independently. The fact that Genghis could have his forces so spread apart and still function cohesively shows how effective the Mongols were in warfare. From 1217-18 the Mongols were fighting a war on many fronts: Muqali was in China warring with the Jinn, Jebe ventured across Central Asia in pursuit of Kuchlug to the borders of Badakhshan near the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) while Subotai and Jochi were hunting down the rival Merkits (Mongols) north of the Jaxartes River (modern, Syr Darya).

^ The Aral Sea with the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) running into it from the south while the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) River runs into it from its east.

Now that the Mongols held dominion over much of northern and northwestern China they were drowning in more goods than they’d ever need. The Mongols were at war with the Jinn and had no interest in going westward, but they were drawn there by fate it seems. This same fate would lead them into the Middle East and the very borders of Europe. Being that they were now the new overlords of the Central Asian khanate of Kara Khitay, the Mongols had access to the silk road’s routes from China to the rich lands of the Middle East. Here in Central Asia they faced a new threat posed by their neighbor, the ambitious and militant Turco-Persian empire of Khwarezmia. Future hostilities between the two would led to the deaths of millions, the destruction of some of the greatest centers of learning, culture and commerce.

Head over to my post, “GENGHIS KHAN, THE STALLION WHO MOUNTS THE WORLD”, to read more about how Genghis Khan was pressured into campaigning out of China toward Central Asia (Kara Khitai Khanate), to Greater Iran (Khwarezmian Empire), to the frontier of Eastern Europe (Medieval Russia and Ukraine) and back to China. I also cover Mongol shamanism and their tolerance of foreign religions, the famed ‘Yam’ pony express, their tactical use of captives and their massive deportation policy.

To read up on the early history of the Mongols, check out my post ‘THE MONGOLS AND THE RISE OF GENGHIS KHAN’. In this post I speak about the Mongolian transition from seemingly insignificant tribal confederacies into an empire that was four times the size of Alexander’s and twice the size of the Roman’s. I cover their military tactics, some of their battle formations, armaments, their rapid adaptation of foreign technologies, and their secretive order of bodyguards known as the Keshik. During Genghis Khan’s early reign the Mongols warred against themselves and their fellow steppe neighbors as well as Northern China’s Western Xia dynasty (Tanguts: Tibeto-Burmese) and eastern Jinn dynasty (Tungusic Jurchens who were Sinicized).

73 notes

·

View notes

Link

Blending fine-grained case studies with overarching theory, this book seeks both to integrate Southeast Asia into world history and to rethink much of Eurasia's premodern past. It argues that Southeast Asia, Europe, Japan, China, and South Asia all embodied idiosyncratic versions of a Eurasian-wide pattern whereby local isolates cohered to form ever larger, more stable, more complex political and cultural systems. With accelerating force, climatic, commercial, and military stimuli joined to produce patterns of linear-cum-cyclic construction that became remarkably synchronized even between regions that had no contact with one another. Yet this study also distinguishes between two zones of integration, one where indigenous groups remained in control and a second where agency gravitated to external conquest elites. Here, then, is a fundamentally original view of Eurasia during a 1,000-year period that speaks to both historians of individual regions and those interested in global trends.

Victor Lieberman. "Volume 2. Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands." Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830. Cambridge University Press, 2009. 976 pages.

The typical Southeast Asian realm remained what I term a “solar polity”: a system of quasi-sovereign satellites in orbit around a central sun whose gravitational pull, in lieu of fixed borders, ebbed with distance. Insofar as each planet had its own moons, which in turn had their dependencies, each satellite replicated in miniature the organization of the solar system as a whole. Moreover, the most distant tributaries might owe allegiance to more than one overlord, while in the rugged interior scattered hill peoples (including refugees from the valleys) often sought to escape entirely the attention of lowland rulers. Although these patterns persisted throughout the period under review, over time the gravitational pull of each sun increased markedly. That is to say, hill people became more sensitive to the cultural and political influence of lowland centers; distant, once independent states were reduced to tributary status; tributaries were converted to intermediate provinces; intermediate and local dynasts with independent military forces. As soon as the capital seemed vulnerable, provincial heads typically sought either to seize the capital and place themselves at the head of the imperial system or to break away from the system entirely. In fact, the sustained independence that many former provincial centers enjoyed during postcharter disorders arguably rendered their sovereign pretensions more credible than during the charter era itself. In both Burma and Siam the late-16thcentury collapse was precipitated by the joining of ambitious provincial leaders with foreign invaders to attack the capital.

Largely in response to these disasters, in the late 1500s and early 1600s the reconstituted empires of Burma and Siam undertook administrative experiments designed, as it were, to strengthen the gravitational pull of the capital. As negotiated with local power holders, who were among the first to recognize the need for more effective central coordination, and as elaborated by the mid-17th century, these reforms rendered the king more ceremonially remote; replaced august viceroys in the provinces with more docile nonprincely governors; insisted that the crown, rather than governors, appoint subgubernatorial officials at major provincial towns; markedly increased the capital’s military superiority over provincial centers; and strengthened patronage links between capital officials and quasi-hereditary local headmen. In close cooperation with the latter, sometimes termed the “gentry,” royal officials extended censuses and cadastres into the provinces, multiplied written communications, and used the resultant information to systematize taxes and to enlarge the ranks of hereditary or quasi-hereditary servicemen (ahmu-dans in Burma, phrai luang in Siam) obliged to provide the crown with specialized military or civilian labor.31 In the interest of military mobilization and fiscal extraction, service reform in turn required more elaborate efforts at social regulation, extending in Burma to an insistence on endogamy among ahmu-dan service units. Burma and Siam also eroded the autonomy of tributaries and retained, in some cases tightened, postcharter curbs on Buddhist monastic landholding and ordination.

[...]

At first sight, administrative trends in Vietnam appear less linear than in Burma or Siam. In the late 1400s the Neo-Confucian revolution introduced a full-blooded Chinese-style bureaucracy, complete with civil service exams, elaborate written communications, novel maps and military itineraries, three layers of appointed officials, and increasingly effective curbs on Buddhist landholding. From the late 1500s, however, oligarchic pressures, military exigency, and non-Chinese cultural influences combined periodically to erode Sinic practices in favor of more patrimonial, more characteristically Southeast Asian forms. This was true in the north for long periods and more especially on the southern frontier. Yet even in the latter zone, as the influence of Chinese ´emigr´es and local literati increased, Neo-Confucian techniques gradually acquired normative prestige. In the early 1800s, after unifying the entire Vietnamese-speaking world, the southern-based Nguyen regime again openly embraced Chinese-style provincial administration in an ambitious effort, by no means unsuccessful, to integrate its fissiparous, elongated domain. In this sense, albeit by looking more directly to China than to north Vietnamese precedents, the Nguyen resumed and intensified Sinicizing trends apparent in the 15th and 17th centuries.

[...]

One could also argue that by facilitating long-distance interactions with diverse peoples, nomadism promoted effective strategies for controlling the logistical and cultural challenges typical of large-scale empires. By contrast, Song (and to a lesser extent Ming) cultural and physical distance from the steppe left them less able than their Sui and Tang, not to mention Mongol and Manchu, counterparts to forge extensive tribal alliances in general, and to acquire desperately needed cavalry mounts in particular.Without steppe allies or reliable purchase of frontier horses (China proper could never compete with the steppe as an environment for breeding and raising horses), Chinese dynasties were obliged to surrender strategic control of the steppe frontier. We shall find that a similar dependence on imported horses disadvantaged agrarian India.

Yet as in Southwest and South Asia, cavalry would have been inadequate to ensure Inner Asian dominance were it not combined with systematic borrowing from agrarian cultures. In explaining the success of the most durable Inner Asian empires, Thomas Barfield was surely justified in emphasizing the combinative role of mixed ecological and cultural zones, what he termed “Manchurian” states, on the interface between Inner Asia and China proper. Here, beyond the reach of Chinese armies, frontier polities like that of the Qing could experiment with elements from both worlds, wedding Inner Asian cavalry and tribal organization to Chinese economy, military techniques, administration, and ideology.217 Now, as Nicola Di Cosmo has shown, in part Inner Asian state formation reflected internal rhythms – he posits a recurrent progression from economic crisis to charismatic leadership to centralized organizations to a search for revenues to sustain those organizations – that did not depend directly on developments in sedentary societies. We find powerful Inner Asian confederations during periods of Chinese political cohesion as well as fragmentation, of economic expansion as well as contraction.218 But over the long run Inner Asian resources and cultural repertoires also benefited substantially from a secular expansion of trade and population along the Chinese/Inner Asian frontier. During China’s first commercial revolution, c. 800/900– 1270, for example, the growth of Chinese settlement and trade provided Tanguts, Khitans, Jurchens, and Mongols with invaluable revenues, administrative and financial expertise.219 Shortly after the start of the second commercial revolution, Iwai Shikegi argues that Manchu power fed on the booming exchange of Inner Asian horses, livestock, furs, and ginseng for Chinese textiles, farm implements, grain, and silver. Because New World silver entering at the coast flowed disproportionately to the northern frontier to pay Ming garrisons, commerce was actually far livelier in this sector than in much of the Chinese interior. Early Manchu commercial monopolies not only provided income, but allowed Manchu leaders to bring within their political orbit a mixed population of Jurchens (amalgamated to form “Manchus” in 1635), Koreans, Mongols, and Chinese. In somewhat similar fashion, I suggested, Tai entry into Southeast Asian lowlands in the 12th and 13th centuries owed much to growing commercial and cultural exchange across charter-era frontiers, while in South Asia between c. 1000 and 1300 and again between 1550 and 1700 we shall find that economic expansion drew together arid-zone warriors and arable-zone cultivators both within the subcontinent and along the interface between India and Inner Asia.220

#southeast asia#anthropology#history#research#east asia#central asia#mongolia#south asia#india#vietnam#myanmar#thailand#china

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Wall of China

Location–China. Type–Fortification, Cultural. Size–21,196 km (13,171 mi). Region–Asia-Pacific.

The Great Wall of China is a series of fortifications made of stone, brick, tamped earth, wood, and other materials, generally built along an east-to-west line across the historical northern borders of China to protect the Chinese states and empires against the raids and invasions of the various nomadic groups of the Eurasian Steppe. Several walls were being built as early as the 7th century BC; these, later joined together and made bigger and stronger, are now collectively referred to as the Great Wall. Especially famous is the wall built 220–206 BC by Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China. Little of that wall remains. Since then, the Great Wall has been rebuilt, maintained, and enhanced; the majority of the existing wall is from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

Chinese Literal Meanings–“The Long Wall“, “The 10,000 mile long wall“

Other purposes of the Great Wall have included border controls, allowing the imposition of duties on goods transported along the Silk Road, regulation or encouragement of trade and the control of immigration and emigration. Furthermore, the defensive characteristics of the Great Wall were enhanced by the construction of watch towers, troop barracks, garrison stations, signaling capabilities through the means of smoke or fire, and the fact that the path of the Great Wall also served as a transportation corridor.

The Great Wall stretches from Dandong in the east to Lop Lake in the west, along an arc that roughly delineates the southern edge of Inner Mongolia. A comprehensive archaeological survey, using advanced technologies, has concluded that the Ming walls measure 8,850 km (5,500 mi). This is made up of 6,259 km (3,889 mi) sections of actual wall, 359 km (223 mi) of trenches and 2,232 km (1,387 mi) of natural defensive barriers such as hills and rivers. Another archaeological survey found that the entire wall with all of its branches measure out to be 21,196 km (13,171 mi).

Names

The collection of fortifications now known as “The Great Wall of China” has historically had a number of different names in both Chinese and English.

In Chinese histories, the term “Long Wall(s)” (長城, changcheng) appears in Sima Qian‘s Records of the Grand Historian, where it referred to both the separate great walls built between and north of the Warring States and to the more unified construction of the First Emperor. The Chinese character 城 is a phono-semantic compound of the “place” or “earth” radical 土 and 成, whose Old Chinese pronunciation has been reconstructed as *deŋ. It originally referred to the rampart which surrounded traditional Chinese cities and was used by extension for these walls around their respective states; today, however, it is much more often simply the Chinese word for “city”.

The longer Chinese name “Ten-Thousand-Mile Long Wall” (萬里長城, Wanli Changcheng) came from Sima Qian’s description of it in the Records, though he did not name the walls as such. The ad 493 Book of Song quotes the frontier general Tan Daoji referring to “the long wall of 10,000 miles”, closer to the modern name, but the name rarely features in pre-modern times otherwise. The traditional Chinese mile (里, lǐ) was an often irregular distance that was intended to show the length of a standard village and varied with terrain but was usually standardized at distances around a third of an English mile (540 m). Since China’s metrication in 1930, it has been exactly equivalent to 500 metres or 1,600 feet, which would make the wall’s name describe a distance of 5,000 km (3,100 mi). However, this use of “ten-thousand” (wàn) is figurative in a similar manner to the Greek and English myriad and simply means “innumerable” or “immeasurable”.

Because of the wall’s association with the First Emperor’s supposed tyranny, the Chinese dynasties after Qin usually avoided referring to their own additions to the wall by the name “Long Wall”. Instead, various terms were used in medieval records, including “frontier(s)” (塞, sāi), “rampart(s)” (垣, yuán), “barrier(s)” (障, zhàng), “the outer fortresses” (外堡, wàibǎo), and “the border wall(s)” (t 邊牆, s 边墙, biānqiáng). Poetic and informal names for the wall included “the Purple Frontier” (紫塞, Zǐsāi) and “the Earth Dragon” (t 土龍, s 土龙, Tǔlóng). Only during the Qing period did “Long Wall” become the catch-all term to refer to the many border walls regardless of their location or dynastic origin, equivalent to the English “Great Wall”.

The current English name evolved from accounts of “the Chinese wall” from early modern European travelers. By the 19th century, “The Great Wall of China” had become standard in English, French, and German, although other European languages continued to refer to it as “the Chinese wall”.

History

Early Walls

The Chinese were already familiar with the techniques of wall-building by the time of the Spring and Autumn period between the 8th and 5th centuries BC. During this time and the subsequent Warring States period, the states of Qin, Wei, Zhao, Qi, Yan, and Zhongshan all constructed extensive fortifications to defend their own borders. Built to withstand the attack of small arms such as swords and spears, these walls were made mostly by stamping earth and gravel between board frames.

#gallery-0-11 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-11 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-11 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-11 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

The Great Wall of the Han

The Great Wall of the Qin

King Zheng of Qin conquered the last of his opponents and unified China as the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty (“Qin Shi Huang”) in 221 BC. Intending to impose centralized rule and prevent the resurgence of feudal lords, he ordered the destruction of the sections of the walls that divided his empire among the former states. To position the empire against the Xiongnu people from the north, however, he ordered the building of new walls to connect the remaining fortifications along the empire’s northern frontier. Transporting the large quantity of materials required for construction was difficult, so builders always tried to use local resources. Stones from the mountains were used over mountain ranges, while rammed earth was used for construction in the plains. There are no surviving historical records indicating the exact length and course of the Qin walls. Most of the ancient walls have eroded away over the centuries, and very few sections remain today. The human cost of the construction is unknown, but it has been estimated by some authors that hundreds of thousands, if not up to a million, workers died building the Qin wall. Later, the Han, the Sui, and the Northern dynasties all repaired, rebuilt, or expanded sections of the Great Wall at great cost to defend themselves against northern invaders. The Tang and Song dynasties did not undertake any significant effort in the region. The Liao, Jin, and Yuan dynasties, who ruled Northern China throughout most of the 10th–13th centuries, constructed defensive walls in the 12th century but those were located much to the north of the Great Wall as we know it, within China’s province of Inner Mongolia and in Mongolia itself.

Ming era

The Great Wall concept was revived again under the Ming in the 14th century, and following the Ming army’s defeat by the Oirats in the Battle of Tumu. The Ming had failed to gain a clear upper hand over the Mongolian tribes after successive battles, and the long-drawn conflict was taking a toll on the empire. The Ming adopted a new strategy to keep the nomadic tribes out by constructing walls along the northern border of China. Acknowledging the Mongol control established in the Ordos Desert, the wall followed the desert’s southern edge instead of incorporating the bend of the Yellow River.

The extent of the Ming Empire and it’s walls.

Unlike the earlier fortifications, the Ming construction was stronger and more elaborate due to the use of bricks and stone instead of rammed earth. Up to 25,000 watchtowers are estimated to have been constructed on the wall. As Mongol raids continued periodically over the years, the Ming devoted considerable resources to repair and reinforce the walls. Sections near the Ming capital of Beijing were especially strong. Qi Jiguang between 1567 and 1570 also repaired and reinforced the wall, faced sections of the ram-earth wall with bricks and constructed 1,200 watchtowers from Shanhaiguan Pass to Changping to warn of approaching Mongol raiders. During the 1440s–1460s, the Ming also built a so-called “Liaodong Wall”. Similar in function to the Great Wall (whose extension, in a sense, it was), but more basic in construction, the Liaodong Wall enclosed the agricultural heartland of the Liaodong province, protecting it against potential incursions by Jurched-Mongol Oriyanghan from the northwest and the Jianzhou Jurchens from the north. While stones and tiles were used in some parts of the Liaodong Wall, most of it was in fact simply an earth dike with moats on both sides.

Towards the end of the Ming, the Great Wall helped defend the empire against the Manchu invasions that began around 1600. Even after the loss of all of Liaodong, the Ming army held the heavily fortified Shanhai Pass, preventing the Manchus from conquering the Chinese heartland. The Manchus were finally able to cross the Great Wall in 1644, after Beijing had already fallen to Li Zicheng‘s rebels. Before this time, the Manchus had crossed the Great Wall multiple times to raid, but this time it was for conquest. The gates at Shanhai Pass were opened on May 25 by the commanding Ming general, Wu Sangui, who formed an alliance with the Manchus, hoping to use the Manchus to expel the rebels from Beijing. The Manchus quickly seized Beijing, and eventually defeated both the rebel-founded Shun dynasty and the remaining Ming resistance, establishing the Qing dynasty rule over all of China.

Under Qing rule, China’s borders extended beyond the walls and Mongolia was annexed into the empire, so constructions on the Great Wall were discontinued. On the other hand, the so-called Willow Palisade, following a line similar to that of the Ming Liaodong Wall, was constructed by the Qing rulers in Manchuria. Its purpose, however, was not defense but rather migration control.

Foreign Account of the Wall

None of the Europeans who visited Yuan China or Mongolia, such as Marco Polo, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, William of Rubruck, Giovanni de’ Marignolli and Odoric of Pordenone, mentioned the Great Wall.

Part of the Great Wall of China, (April, 1853).

The North African traveler Ibn Battuta, who also visited China during the Yuan dynasty ca. 1346, had heard about China’s Great Wall, possibly before he had arrived in China. He wrote that the wall is “sixty days’ travel” from Zeitun (modern Quanzhou) in his travelogue Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling. He associated it with the legend of the wall mentioned in the Qur’an, which Dhul-Qarnayn (commonly associated with Alexander the Great) was said to have erected to protect people near the land of the rising sun from the savages of Gog and Magog. However, Ibn Battuta could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen it, suggesting that although there were remnants of the wall at that time, they weren’t significant.

The Great wall in 1907.

Soon after Europeans reached Ming China by ship in the early 16th century, accounts of the Great Wall started to circulate in Europe, even though no European was to see it for another century. Possibly one of the earliest European descriptions of the wall and of its significance for the defense of the country against the “Tartars” (i.e. Mongols), may be the one contained in João de Barros‘s 1563 Asia. Other early accounts in Western sources include those of Gaspar da Cruz, Bento de Goes, Matteo Ricci, and Bishop Juan González de Mendoza. In 1559, in his work “A Treatise of China and the Adjoyning Regions,” Gaspar da Cruz offers an early discussion of the Great Wall. Perhaps the first recorded instance of a European actually entering China via the Great Wall came in 1605, when the Portuguese Jesuit brother Bento de Góis reached the northwestern Jiayu Pass from India. Early European accounts were mostly modest and empirical, closely mirroring contemporary Chinese understanding of the Wall, although later they slid into hyperbole, including the erroneous but ubiquitous claim that the Ming Walls were the same ones that were built by the First Emperor in the 3rd century BC.

When China opened its borders to foreign merchants and visitors after its defeat in the First and Second Opium Wars, the Great Wall became a main attraction for tourists. The travelogues of the later 19th century further enhanced the reputation and the mythology of the Great Wall, such that in the 20th century, a persistent misconception exists about the Great Wall of China being visible from the Moon or even Mars.

Course

Although a formal definition of what constitutes a “Great Wall” has not been agreed upon, making the full course of the Great Wall difficult to describe in its entirety, the course of the main Great Wall line following Ming constructions can be charted.

The Jiayu Pass, located in Gansu province, is the western terminus of the Ming Great Wall. Although Han fortifications such as Yumen Pass and the Yang Pass exist further west, the extant walls leading to those passes are difficult to trace. From Jiayu Pass the wall travels discontinuously down the Hexi Corridor and into the deserts of Ningxia, where it enters the western edge of the Yellow River loop at Yinchuan. Here the first major walls erected during the Ming dynasty cuts through the Ordos Desert to the eastern edge of the Yellow River loop. There at Piantou Pass (t 偏頭關, s 偏头关, Piāntóuguān) in Xinzhou, Shanxi province, the Great Wall splits in two with the “Outer Great Wall” (t 外長城, s 外长城, Wài Chǎngchéng) extending along the Inner Mongolia border with Shanxi into Hebei province, and the “inner Great Wall” (t 內長城, s 內长城, Nèi Chǎngchéng) running southeast from Piantou Pass for some 400 km (250 mi), passing through important passes like the Pingxing Pass and Yanmen Pass before joining the Outer Great Wall at Sihaiye (四海冶, Sìhǎiyě), in Beijing’s Yanqing County.

The main sections of the Great Wall of China that are still standing today.

The sections of the Great Wall around Beijing municipality are especially famous: they were frequently renovated and are regularly visited by tourists today. The Badaling Great Wall near Zhangjiakou is the most famous stretch of the Wall, for this is the first section to be opened to the public in the People’s Republic of China, as well as the showpiece stretch for foreign dignitaries. South of Badaling is the Juyong Pass; when used by the Chinese to protect their land, this section of the wall had many guards to defend China’s capital Beijing. Made of stone and bricks from the hills, this portion of the Great Wall is 7.8 m (25 ft 7 in) high and 5 m (16 ft 5 in) wide.

One of the most striking sections of the Ming Great Wall is where it climbs extremely steep slopes in Jinshanling. There it runs 11 km (7 mi) long, ranges from 5 to 8 m (16 ft 5 in to 26 ft 3 in) in height, and 6 m (19 ft 8 in) across the bottom, narrowing up to 5 m (16 ft 5 in) across the top. Wangjinglou (t 望京樓, s 望京楼, Wàngjīng Lóu) is one of Jinshanling’s 67 watchtowers, 980 m (3,220 ft) above sea level. Southeast of Jinshanling is the Mutianyu Great Wall which winds along lofty, cragged mountains from the southeast to the northwest for 2.25 km (1.40 mi). It is connected with Juyongguan Pass to the west and Gubeikou to the east. This section was one of the first to be renovated following the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.

An area of the sections of the Great Wall at Jinshanling.

At the edge of the Bohai Gulf is Shanhai Pass, considered the traditional end of the Great Wall and the “First Pass Under Heaven“. The part of the wall inside Shanhai Pass that meets the sea is named the “Old Dragon Head”. 3 km (2 mi) north of Shanhai Pass is Jiaoshan Great Wall (焦山長城), the site of the first mountain of the Great Wall. 15 km (9 mi) northeast from Shanhaiguan is Jiumenkou (t 九門口, s 九门口, Jiǔménkǒu), which is the only portion of the wall that was built as a bridge. Beyond Jiumenkou, an offshoot known as the Liaodong Wall continues through Liaoning province and terminates at the Hushan Great Wall, in the city of Dandong near the North Korean border.

In 2009, 180 km of previously unknown sections of the wall concealed by hills, trenches and rivers were discovered with the help of infrared range finders and GPS devices. In March and April 2015 nine sections with a total length of more than 10 km (6 mi), believed to be part of the Great Wall, were discovered along the border of Ningxia autonomous region and Gansu province.

Characteristics

The Great Wall near Mutianyu, Beijing.

Before the use of bricks, the Great Wall was mainly built from rammed earth, stones, and wood. During the Ming, however, bricks were heavily used in many areas of the wall, as were materials such as tiles, lime, and stone. The size and weight of the bricks made them easier to work with than earth and stone, so construction quickened. Additionally, bricks could bear more weight and endure better than rammed earth. Stone can hold under its own weight better than brick, but is more difficult to use. Consequently, stones cut in rectangular shapes were used for the foundation, inner and outer brims, and gateways of the wall. Battlements line the uppermost portion of the vast majority of the wall, with defensive gaps a little over 30 cm (12 in) tall, and about 23 cm (9.1 in) wide. From the parapets, guards could survey the surrounding land. Communication between the army units along the length of the Great Wall, including the ability to call reinforcements and warn garrisons of enemy movements, was of high importance. Signal towers were built upon hill tops or other high points along the wall for their visibility. Wooden gates could be used as a trap against those going through. Barracks, stables, and armories were built near the wall’s inner surface.

Condition

A more rural portion of the Great Wall that stretches throughout the mountains, here seen in slight disrepair.

While some portions north of Beijing and near tourist centers have been preserved and even extensively renovated, in many locations the Wall is in disrepair. Those parts might serve as a village playground or a source of stones to rebuild houses and roads. Sections of the Wall are also prone to graffiti and vandalism, while inscribed bricks were pilfered and sold on the market for up to 50 renminbi. Parts have been destroyed because the Wall is in the way of construction. A 2012 report by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage states that 22% of the Ming Great Wall has disappeared, while 1,961 km (1,219 mi) of wall have vanished. More than 60 km (37 mi) of the wall in Gansu province may disappear in the next 20 years, due to erosion from sandstorms. In places, the height of the wall has been reduced from more than 5 m (16 ft 5 in) to less than 2 m (6 ft 7 in). Various square lookout towers that characterize the most famous images of the wall have disappeared. Many western sections of the wall are constructed from mud, rather than brick and stone, and thus are more susceptible to erosion. In 2014 a portion of the wall near the border of Liaoning and Hebei province was repaired with concrete. The work has been much criticized.

Visibility from Space

From the Moon

One of the earliest known references to the myth that the Great Wall can be seen from the moon appears in a letter written in 1754 by the English antiquary William Stukeley. Stukeley wrote that, “This mighty wall of four score miles [130 km] in length is only exceeded by the Chinese Wall, which makes a considerable figure upon the terrestrial globe, and may be discerned at the Moon.” The claim was also mentioned by Henry Norman in 1895 where he states “besides its age it enjoys the reputation of being the only work of human hands on the globe visible from the Moon.” The issue of “canals” on Mars was prominent in the late 19th century and may have led to the belief that long, thin objects were visible from space. The claim that the Great Wall is visible from the moon also appears in 1932’s Ripley’s Believe It or Not! strip and in Richard Halliburton‘s 1938 book Second Book of Marvels.

The claim the Great Wall is visible from the moon has been debunked many times, but is still ingrained in popular culture. The wall is a maximum 9.1 m (29 ft 10 in) wide, and is about the same color as the soil surrounding it. Based on the optics of resolving power (distance versus the width of the iris: a few millimeters for the human eye, meters for large telescopes) only an object of reasonable contrast to its surroundings which is 110 km (70 mi) or more in diameter (1 arc-minute) would be visible to the unaided eye from the Moon, whose average distance from Earth is 384,393 km (238,851 mi). The apparent width of the Great Wall from the Moon is the same as that of a human hair viewed from 3 km (2 mi) away. To see the wall from the Moon would require spatial resolution 17,000 times better than normal (20/20) vision. Unsurprisingly, no lunar astronaut has ever claimed to have seen the Great Wall from the Moon.

From low Earth Orbit

A more controversial question is whether the Wall is visible from low Earth orbit (an altitude of as little as 160 km (100 mi)). NASA claims that it is barely visible, and only under nearly perfect conditions; it is no more conspicuous than many other man-made objects. Other authors have argued that due to limitations of the optics of the eye and the spacing of photoreceptors on the retina, it is impossible to see the wall with the naked eye, even from low orbit, and would require visual acuity of 20/3 (7.7 times better than normal).

Image={*A satellite image of a section of the Great Wall in northern Shanxi, running diagonally from lower left to upper right and not to be confused with the more prominent river running from upper left to lower right. The region pictured is 12 km × 12 km (7 mi × 7 mi).*}

Astronaut William Pogue thought he had seen it from Skylab but discovered he was actually looking at the Grand Canal of China near Beijing. He spotted the Great Wall with binoculars, but said that “it wasn’t visible to the unaided eye.” U.S. Senator Jake Garn claimed to be able to see the Great Wall with the naked eye from a space shuttle orbit in the early 1980s, but his claim has been disputed by several U.S. astronauts. Veteran U.S. astronaut Gene Cernan has stated: “At Earth orbit of 100 to 200 miles [160 to 320 km] high, the Great Wall of China is, indeed, visible to the naked eye.” Ed Lu, Expedition 7 Science Officer aboard the International Space Station, adds that, “it’s less visible than a lot of other objects. And you have to know where to look.”

In 2001, Neil Armstrong stated about the view from Apollo 11: “I do not believe that, at least with my eyes, there would be any man-made object that I could see. I have not yet found somebody who has told me they’ve seen the Wall of China from Earth orbit. … I’ve asked various people, particularly Shuttle guys, that have been many orbits around China in the daytime, and the ones I’ve talked to didn’t see it.”

In October 2003, Chinese astronaut Yang Liwei stated that he had not been able to see the Great Wall of China. In response, the European Space Agency (ESA) issued a press release reporting that from an orbit between 160 and 320 km (100 and 200 mi), the Great Wall is visible to the naked eye. In an attempt to further clarify things, the ESA published a picture of a part of the “Great Wall” photographed from low orbit. However, in a press release a week later, they acknowledged that the “Great Wall” in the picture was actually a river.

Leroy Chiao, a Chinese-American astronaut, took a photograph from the International Space Station that shows the wall. It was so indistinct that the photographer was not certain he had actually captured it. Based on the photograph, the China Daily later reported that the Great Wall can be seen from ‘space’ with the naked eye, under favorable viewing conditions, if one knows exactly where to look. However, the resolution of a camera can be much higher than the human visual system, and the optics much better, rendering photographic evidence irrelevant to the issue of whether it is visible to the naked eye.

Gallery

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Don’t b selfish by not sharing the knowledge you just gained… 😊

If u liked this… Leave a Like… ^_^

G+ Facebook Youtube

Thänk Yoυ

The Great Wall of China – Seven Wonders of the Medieval Ages..! Great Wall of China The Great Wall of China is a series of fortifications made of stone, brick, …

0 notes

Photo

Yelu Dashi (r. 1134-1143) was the founder of the Qara-Khitai Khanate, and his grandson Yelu Zhilugu (r. 1177-1211) was the final ruler (Gur-khan) of that Khanate. The Qara-Khitai was a fascinating, but little known empire. The Khitan Liao Dynasty (907-1125) was quickly overrun by the Jurchen Jin (1115-1234) in the early 12th century, and Yelu Dashi, a Khitan noble related to the imperial family, fled China, crossing Mongolia and eventually making his way to central Asia, where he established the Qara Khitai. The Qara Khitai went on to control an area from Transoxania to the Tarim Basin, mighty empire combing Chinese-Khitan ruling customs over a largely Muslim population. After Dashi's death in 1143 the empire declined, and the long rule of his grandson Zhilugu marked the final years of the dynasty. Vassals broke away, financial crisis gripped the empire, religious factionalism began to tear it apart and his former vassals, the Khwarezm-Shahs, challenged and fought with him. The appearance of a Naiman prince, Kuchlug, fleeing the wrath of Chinggis Khan in Mongolia and welcomed into the Qara-Khitai, tipped the balance against Zhilugu. Even though he married a daughter of Zhilugu and was given titles and power, he betrayed his step father, raiding the imperial treasury and conspiring with the Khwarezm-Shah, Muhammad bin Tekish. In late 1211, Kuchlug captured Zhilugu while he was on a hunting trip, and kept the former Gur-Khan captive while claiming power for himself. In the end, Kuchlug's ascension brought Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Empire to Central Asia, now bordering the Khwarezmian Empire... To learn more about the Qara Khitai, check out my latest videos: Part One, the Rise: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k22BPOpihhQ Part Two, the Decline: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wj5MzSmo8-I

#qara khitai#khitans#liao#china#history#medieval#mongol empire#uzbekistan#bukhara#samarkand#balasagun#tekish#muhammad#shah muhammad#khwarezmian empire#khwarezm#qarakhanid#jin#central asia#jackmeister#youtube#chinggis khan#genghis khan#yelu dashi#dashi#zhilugu#kuchlug#nomads#khans#sultans

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kashgar Harvest Raid

Kashgar, and other major centres of the Tarim Basin, had long been vassals of the Qara-Khitai, but around 1211 began to revolt. In that year, Kuchlug, a Naiman prince who fled Chinggis Khan's conquest of Mongolia, had usurped power in Qara-Khitai, capturing the Gurkhan. Kuchlug's reign was characterized by mistreatment of his Muslim subjects (the largest and wealthiest demographic of his new empire), increasing taxation both in amount and frequency with which he collected it, a stark contrast to the lighter rule of the Gurkhans and quickly brought the displeasure of the populace. What exactly set off matters in the Tarim Basin is hard to say, as our sources confuse the timelines between them, but a combination of factors likely contributed to the violence. The Khan of Kashgar, imprisoned by the Gurkhans but released by Kuchlug, was murdered on his return to Kashgar, an affront Kuchlug could not ignore. An imam in Khotan, speaking out against Kuchlug's policies, was nailed to the doors of his own madrassa on Kuchlug's order, while a little north in the Qulja (Yining) region, a Qarluq Turk named Bozar seized power in Almaliq, declaring himself a vassal of Chinggis Khan (at that time just beginning his campaign in China against the Jurchen Jin). Further, Juvaini informs us that Kuchlug, a recent convert to Buddhism from Nestorian Christianity, tried to force his Muslim subjects to convert to Buddhism, Christianity or at least adopt the dress of the Khitans. Coupled with the general antagonism to Kuchlug's taxation policies and the general breakdown in Qara-Khitai authority due to Kuchlug's usurption and confrontation with his western neighbour, the Khwarezm Shah Muhammad, in addition to former vassals of the Qara-Khitai like the Qarluqs and Uighurs joining the Mongols, it is easy to see that this was a volatile climate. Kuchlug forces attacked Kashgar and the other revolting regions in the harvest season, destroying the crops every year for 3-4 years. The result was the revolt dying down due to starvation: Kuchlug then consolidated his victory by billeting his forces in the homes of the local populace. While for now the region was quieted, in 1216 Chinggis Khan, back in Mongolia, was able to turn his attention to matters closer to home, one of which was Kuchlug. Chinggis Khan's great general Jebe Noyan would invade the Qara-Khitai with 20,000, and he would take advantage of the latent hate for Kuchlug in the Tarim Basin. To learn more about the end of the Qara-Khitai and reign of Kuchlug, check out my video on this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RU_OQZS9TBE

#kashgar#harvest#raid#attack#medieval#history#asia#asian history#islam#islamic history#muslim#muslim history#uighur#uyghur#mongol empire#youtube#mongolia#genghis khan#chinggis khan#jebe#kuchlug#naiman#turk#qarluq#almaliq#tarim#tarim basin#taklamakan#khotan#yining

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Toluid Civil War: 1260-1264

The Toluid Civil War started after the death of the Great Khan Mongke in August 1259. The Mongol Empire never developed anything but the vaguest of succession systems: in theory, anyone who was a descendant of Chinggis Khan could have been elected Great Khan if they could gather the support of the tribes, although this was limited to his four sons with Borte, seems to have excluded the descendents of Jochi and became dependent on taking the position through force. After Mongke’s death, the two candidates who put their names forward were his younger brothers Kublai and Ariq Boke.

It appears both brothers began efforts to consolidate their positions as soon as they learned of Mongke’s death. Kublai had been campaigning against the Song Dynasty in China, and to not waste his effort there, and likely to not look like he abandoned the campaign to grab power, continued to campaign for another two months before moving north. Ariq on the other hand immediately began building support, getting some of Mongke’s widows and children to support him, as well as their powerful cousin Berke, Khan of the Golden Horde, and a grandson of Chagatai, Alghu, a major power in the Chagatai Khanate. Even by this point, Kublai was noted for his affinity to Chinese culture, having spent considerable time there and had already built a Chinese style city in modern Inner Mongolia, K’ai-ping (renamed to Shangdu in 1263, better known in English as Xanadu). Ariq on the other hand, was a staunch traditionalist, and saw no use for the Chinese except as subjects of the Mongols. As Kublai was seen as too soft and sedentary (it seems he was already rather heavy set, an alcoholic and suffering from gout) it was easy for Ariq to garner support on the grounds of maintaining the legacy of Chinggis.