#kuchlug

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

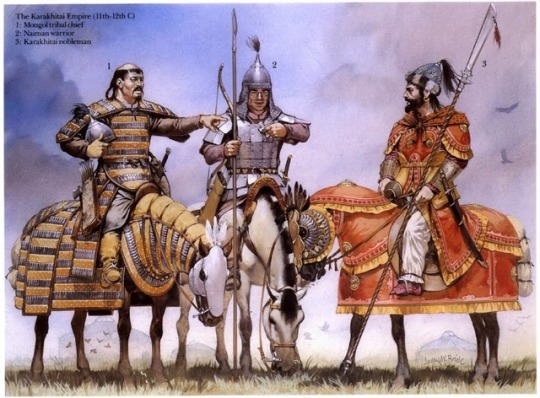

THE BATTLE OF QUYLI, 1218/1219, a part of the western expansion of the Mongol Empire. The little known battle of Quyli, somewhere along the Irtysh River, was the first confrontation between Mongolian and Khwarezmian forces, occurring after a wide sweep of Chinggis Khan's enemies. In 1211, Chinggis Khan had begun his invasion of the mighty Jurchen Jin Empire of Northern China, succeeding in taking its central capital and most of their territory north of the Yellow River. By 1216 he had returned to Mongolia to rest his forces, and deal with threats that had emerged in his absence. To the north, various forest tribes had revolted against Mongol rule, while to the west Qodu, the son of Chinggis' old enemy Toqto'a Beki of the Merkit (who had kidnapped his wife Borte in the 1180s) had organized an alliance between surviving Merkits and Kipchak tribes around the Aral Sea. As well, since 1211 Kuchlug of the Naiman, son of a defeated Khan who had fought Chinggis, had taken control of the Qara-Khitai Empire, controlling much of modern Kazakhstan and Xinjiang. Jochi, eldest son of Chinggis Khan, and Subutai were ordered west by the Great Khan to destroy the Merkit-Kipchak alliance . This brought them possibly as far west as the Volga River before they had succeeded in their mission, and by 1218 they were ready to return to Mongolia. En route however, they ran into an army led by the most powerful monarch of the Islamic world: Shah Muhammad II of the Khwarezmian Empire. It is unclear why the Khwarezm-shah had traveled so far north: the sources give reasons such as a confrontation between the Shah and his father, a Kipchak Khan named Qadir, chasing the Merkits or Mongols, or Kuchlug. Jochi and Subutai, outnumbered perhaps 3:1 (60,000 to 20,000), were understandably not interested with opening hostilities with a new foe, and requested free passage. The Shah was an ambitious, vain and foolhardy man, and pride may have gotten the best of him. He believed himself a "second Alexander," a keen military mind, was proud and likely did not trust the Mongols to not raid his territory on their route. He prepared his troops for battle, and for the first time Mongolian and Khwarezmian forces fought. Both sides fought with cavalry heavy armies (horse archers, light and heavy cavalry) with the Khwarezmian forces mainly made up of Turkic tribesmen. The Shah's forces were larger, experienced but not as disciplined as Mongolian troops. The right wings of both forces pushed back the opposing left: Jochi, commanding the Mongol left, was injured but saved by timely maneuvers of loyal Khitans. Battle continued until nightfall, when darkness forced them apart. The Mongols employed a favoured stratagem, lighting many fires to appear to be setting up camp, and departed. By morning the Mongols were long gone, Shah Muhammad looking forlornly over a body strewn battlefield. The repercussions of this confrontation were serious: Shah Muhammad is said to have developed a phobia of facing the Mongols in open battle after seeing their ferocity first hand, which led to a mostly defensive strategy with Khwarezmian forces staying in cities during the following Mongol invasion, which allowed the numerically inferior Mongols to isolate and destroy the Khwarezmian cities, one by one. Christopher Atwood suggests that Chinggis Khan likely learned of the battle at Quyli around similar time that news reached him of a further treachery by the Khwarezmians. The governor of Otrar, the Shah's uncle Inalchuq, massacred an merchant caravan sent by Chinggis to act as envoys. A follow up diplomatic mission to the Shah saw the lead envoy decapitated and the two Mongol grandees sent back to Chinggis with shaved heads and burnt off beards. The insult was clear: war was to come between the Khwarezmian and Mongol Empires. To learn more about these campaigns, check out my latest video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1FJTnCCBcsE

#mongol empire#genghis khan#chinggis khan#mongol invasion#khwarezmian empire#Shah Muhammad II of Khwarezmia#youtube#education#jackmeister#kuchlug#jebe#jochi#subutai#qara-khitai#history#medieval#military history#middle ages#iran#kazakhstan#battle#war#quyli#irtysh#kipchak#cuman#turk#turkic#mongol#mongolia

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE MONGOLS UNDER GENGHIS KHAN WAR AGAINST THE TURCO-MONGOL REALM OF KARA KHITAY, 1216–1218 CE:

The following is an excerpt from my post, “GENGHIS KHAN, THE STALLION WHO MOUNTS THE WORLD”.

The Turkish and Mongolian religion of Tengrism was a combination of ancestor worship, shamanism, animism (the belief that natural objects, natural phenomena, and the universe itself possess souls) and totemism (belief in kinship with or a mystical relationship between a group or an individual and a totem (a natural object or an animate being, as an animal or bird, assumed as the emblem of a clan, family, or group).

For the most part it was polytheistic (“many gods”) as they believed in many spirits and deities but some followers were monotheistic (“single god”) since they held Tengri, or ‘Munkh Khukh Tengri’ (“Eternal Blue Sky”), as their supreme god. Mongolians refer to Mongolia as ‘Munkh Khukh Tengriin Oron’, “Land of Eternal Blue Sky”. Although Tengrism was common place among the Turks and Mongols, they didn’t expect others to follow their religion. Only their supreme god Tengri could truly judge whether a man was righteous enough or not, despite one’s religion.

“We believe that there is only one God, by whom we live and by whom we die, and for whom we have an upright heart. But as God gives us the different fingers of the hand, so he gives to men diverse ways to approach Him.” – Mongke Khan (Fourth Khan, 1251–1259) during a religious debate in court. According to William of Rubruck (May 31, 1254).

“…Your saying ‘May [the Ilkhan] receive silam (baptism)’ is legitimate. We say: 'We the descendants of Genghis Khan, keeping our own proper Mongol identity, whether some receive silam or some don’t, that is only for Mongke Tengri (Eternal Heaven) to know (decide).’ People who have received silam and who, like you, have a truly honest heart and are pure, do not act against the religion and orders of the Eternal Tengri and of Misiqa (Messiah or Christ).

Regarding the other peoples, those who, forgetting the Eternal Tengri and disobeying him, are lying and stealing, are there not many of them? Now, you say that we have not received silam, you are offended and harbor thoughts of discontent. [But] if one prays to Eternal Tengri and carries righteous thoughts, it is as much as if he had received silam.” – From a letter sent from Arghun Khan of the Mongol Ilkhanate (1284–1291 CE) to Pope Nicholas IV (written May 14th, 1290).

Many steppe factions had already taken on other religions like Islam, Nestorianism (Christianity), Buddhism, and Manicheism. Their subjects were free to practice their religion, culture and laws but the Mongolian ‘Great Yasa’ (code of laws) came first. As Genghis Khan sought to unite his nation, he made it clear that people would be judged by their loyalty, diligence and skill rather than their lineage, ethnicity, culture and religion.

^ Osprey – ‘Men-at-Arms’ series, issue 295 – Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590–1260 AD by CJ Peers and Michael Perry (Illustrator). Plate H: A Liao Council of War. H1: Khitan ordo cavalryman – “The famous Wen Ch’i scroll depicts a party of these ‘barbarians’ in the act of looting a Chinese house. It is thought that the scroll is based on an original of the Sung period, and that the models for figures were Khitan warriors. This man has removed his helmet, showing the soft cap worn underneath. He carries a mace as prescribed in the Liao Shih and illustrated in tomb paintings. Also carried were bows, spears and halberds. Jurchen, and even Mongol heavy cavalry, would have looked very similar. This source shows coats in various shades of brown, and trousers as brown or blue. The Jurchen favored bright colours such as red, yellow and white, and made much use of animal skins and furs. They arranged their hair in a pigtail and, like the later Manchus, imposed this style on their Chinese subjects as a sign of submission. Guards at the Kin (Jinn) court are said to have worn red or blue cuirasses, probably of lacquered leather.” H2: General – “This man is wearing a spectacular suit of gilded armour as depicted in the Wen Ch’i scroll, is obviously as high-ranking officer. On the scroll there are unarmoured figures shown in attendance, carrying pieces of his armour. They may therefore represent the ‘orderlies’ or ‘foragers’ who fought as lightly equipped cavalry in the Liao armies.” H3: Mongolian auxiliary.

Back in 1125 CE the Khitan (Sinicized Mongolians) Liao dynasty of northern China was overthrown and taken over by the Jurchens (Tungusic peoples who established the Jinn dynasty). From then on the Khitans lived primarily in what is now Manchuria (northern China, bordering modern Mongolia) but a portion of the Khitan under Yelu Dashi of the Liao dynasty fled westward over the Tien mountains into Central Asia where they were joined and augmented by neighboring Turkish tribes. The khanate they established became known as Kara Khitay (“Black-Cathay”) and encompassed modern Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, southern Kazakhstan and western China (Xinjiang).

Before warring with the Western Xia, Genghis Khan defeated the Naimans which were under the leadership of a man named Taibuqa who was their Tayang Khan. After Taibuqa Tayang Khan was killed, his son Kuchlug fled to Central Asia in 1208 CE where he met the Gur-Khan (Chief of Khans) of the Kara Khitan Khanate who welcomed him as they often did to Turkish and Mongol refugees. Kuchlug became the Gur-Khan’s adviser and in time married a daughter of his; his goals, however, were set much higher. The Shah of the Khwarezmian Empire (Turco-Persian) was already at war with the Gur-Khan of Kara Khitay so in 1211 CE Kuchlug allied himself with the shah, agreeing to split the khanate between the two of them. Eventually the Gur-Khan of Kara Khitay was captured, Kuchlug usurped the throne and the western portion of his new empire was given to the shah as promised.

^ Kara Khitay khanate c.1200 CE.

Now many steppe factions such as the Naimans, Kerayits, Merkits and the Mongols practiced Tengrism with mixtures of Tibetan Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity (Church of the East) and/or Manicheism (Persian religion dating back to the third century CE, dualistic belief in a war between good and evil. Christian and Gnostic influence). Kuchlug practiced Nestorian Christianity but was converted to Buddhism at the behest of his wife (the former Gur-Khan’s daughter). Kuchlug began to fear, and rightfully so, the shah and his rapidly expanding Islamic realm of Khwarezmia.

If the shah were ever to turn against Kuchlug, would Kuchlug‘s subjects (the majority of which were Muslim) side with the Kara Khitay or with the Islamic shah of Khwarezmia who claimed to be the ’Shadow of God on Earth’, Iskander (Alexander the Great), and the ‘Chosen Prince of Allah’. Kuchlug became Islamophobic and began a forced conversion policy in which his subjects had to either convert (to Buddhism or Nestorian Christianity) or begin donning Khitan garb. Kuchlug also banned public worship and calls to prayer.

“After Kuchlug had conquered Kashghar and Khotan and had abandoned the law of Christianity for the habit of idolatry, he charged the inhabitants of these parts to forsake their pure Hanafite faith for unclean heathendom, and to turn from the rays of the light of Guidance to the wilderness of infidelity and darkness, and from allegiance to a merciful King to subservience to an accursed Devil. And as this door would not give way, he kicked it with his foot; and by force they were compelled to don the garb and headdress of Error: the sound of worship and the iqamat was abolished and prayers and takbirs were hushed.” – Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini (1226–1283 CE), Persian historian and governor of Baghdad.

When Kuchlug left his capital of Balasagun, it rebelled and shut the gates to him. Kuchlug Gur-Khan then besieged it and, once captured, he razed the city. Due to his religious policies the city of Kashgar rebelled in 1213 CE, in response Kuchlug burned their harvest which led to severe starvation within the city. There was also an imam in the city of Khotan which criticized and embarrassed Kuchlug so he had the imam crucified to the door of said imam’s madrasa (Islamic educational institution).

“they crucified him (the imam) upon the door of his school which he had built in Khotan” – Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini (1226–1283 CE), Persian historian and governor of Baghdad.

^ Where Kuchlug’s capital of Balasagun once stood there are now only ruins, most popular are the remains of a 82 ft. tall (originally 148 ft. tall) minaret known as the Burana Tower which stands like an eerie echo of the past.

As a continuous flow of anti-Genghis nomads traveled to the Kara Khitay Khanate, the possibility of the Great Khan turning his gaze at the threat posed by his old foe’s growing power was inevitable. While Genghis was occupied campaigning against the Jinn dynasty of northern China, he had no interest in the Kara Khitay Khanate until Kuchlug made the great mistake of besieging the city of Almaliq, which were vassals of the Mongols. In response to the pleas of the cities of Balasagun, Kashgar, and Almaliq, Genghis decided to focus his attention towards this distant foe.

Genghis Khan sent Jebe, a general renowned for his skill in rapid and deep infiltrative operations, to invade the realm of Kara Khitay, execute Kuchlug, abstain from harming any one not allied with Kuchlug and spread the word that under Mongol rule all subjects would be allowed freedom of worship. Throughout Kara Khitay the settlements which were predominantly populated by Muslims massacred any pro-Kuchlug forces, voluntarily opening their gates to Jebe and sided with the Mongols. Kuchlug was caught, beheaded, had his head placed on a pole and then paraded.

Genghis’ promotion of meritocracy allowed him to easily place trust in his generals since he knew they were skilled and experience enough to act independently. The fact that Genghis could have his forces so spread apart and still function cohesively shows how effective the Mongols were in warfare. From 1217-18 the Mongols were fighting a war on many fronts: Muqali was in China warring with the Jinn, Jebe ventured across Central Asia in pursuit of Kuchlug to the borders of Badakhshan near the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) while Subotai and Jochi were hunting down the rival Merkits (Mongols) north of the Jaxartes River (modern, Syr Darya).

^ The Aral Sea with the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) running into it from the south while the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) River runs into it from its east.

Now that the Mongols held dominion over much of northern and northwestern China they were drowning in more goods than they’d ever need. The Mongols were at war with the Jinn and had no interest in going westward, but they were drawn there by fate it seems. This same fate would lead them into the Middle East and the very borders of Europe. Being that they were now the new overlords of the Central Asian khanate of Kara Khitay, the Mongols had access to the silk road’s routes from China to the rich lands of the Middle East. Here in Central Asia they faced a new threat posed by their neighbor, the ambitious and militant Turco-Persian empire of Khwarezmia. Future hostilities between the two would led to the deaths of millions, the destruction of some of the greatest centers of learning, culture and commerce.

Head over to my post, “GENGHIS KHAN, THE STALLION WHO MOUNTS THE WORLD”, to read more about how Genghis Khan was pressured into campaigning out of China toward Central Asia (Kara Khitai Khanate), to Greater Iran (Khwarezmian Empire), to the frontier of Eastern Europe (Medieval Russia and Ukraine) and back to China. I also cover Mongol shamanism and their tolerance of foreign religions, the famed ‘Yam’ pony express, their tactical use of captives and their massive deportation policy.

To read up on the early history of the Mongols, check out my post ‘THE MONGOLS AND THE RISE OF GENGHIS KHAN’. In this post I speak about the Mongolian transition from seemingly insignificant tribal confederacies into an empire that was four times the size of Alexander’s and twice the size of the Roman’s. I cover their military tactics, some of their battle formations, armaments, their rapid adaptation of foreign technologies, and their secretive order of bodyguards known as the Keshik. During Genghis Khan’s early reign the Mongols warred against themselves and their fellow steppe neighbors as well as Northern China’s Western Xia dynasty (Tanguts: Tibeto-Burmese) and eastern Jinn dynasty (Tungusic Jurchens who were Sinicized).

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khan...Genghis Khan

1218: I am Genghis Khan, ruler of the Mongols and conqueror of the world. I am having my words transcribed so that those who come after me may remember all that has happened to the Mongols, a history of them and of me. As I speak, we are at war with my enemy Kuchlug. He is a Naiman and the only one who currently poses a threat to the new found peace of the United Mongolian tribes. He must die. All for now.

0 notes

Text

"Why did the Mongols invade most of the Old World?"

A write up I did on Reddit for a question: "what caused the Mongols to invade most of the Old World?"

It was almost accidental. At no point when he began uniting the Mongol tribes did Chinggis Khan (the more accurate rendition of Genghis Khan) seek out world domination. Rather, it sort of kept happening.

What people don't realize is that Chinggis Khan didn't succeed in uniting the Mongols until he was about 50, declaring the Mongol Empire in 1206 (he was born in 1162 as Temujin, and it wasn't until 1206 when he began being called Chinggis). That was many decades of slow warfare and his own losses and defeats before he succeeded in doing so. Initially he was probably concerned only in securing his own position and safety, perhaps at best hoping for leadership of his own tribe. Events went differently, and a 'concerned citizens' alliance of steppe notables unhappy with Temujin's rise (such as appointing his generals and chief lieutenants from common folk based on their ability, rather than old bloodlines) turned the conflict into a massive civil war for control of Mongolia. By this time this was complete, Temujin had restructure Mongolian society, breaking the power of tribal Khans and old tribal ties, placing himself, the Great Khan, at the head, with discipline and utter loyalty the byword, harnessing the great military potential of the steppe horse archer.

By 1206 then he had a fierce military force, a great spear: but had almost run out of enemies in Mongolia itself. All dressed up and nowhere to go, you might say. What Chinggis Khan understood was that he needed a common enemy, or old internal intrigues would rise back up to the surface and tear his new union apart. The spear needed to be thrown, lest it fall apart. The obvious answer lay to the south, the kingdoms of northern China, the Tangut Xi Xia in modern Gansu/Ningxia, and the Jurchen Jin Dynasty controlling from Manchuria to the Huai River, capital at Zhongdu (modern Beijing). Whether Chinggis at this stage was intending to conquer them, or attack and raid is hard to say. Personally, his actions to me suggest the latter, but some argue for the former. There certainly were pretexts to attack both. The Tangut had allowed certain enemies of Chinggis to flee through their territory or seek shelter, and the Jin had long been enemies of the Mongols, breaking up an earlier Mongol union (commonly called the Khamag Mongol confederation) in the early 12th century. While there certainly was this pretext, it should also be noted that a quite dry period in late 12th century Mongolia, and continuous warfare, had depleted the herds the Mongols relied on to survive as well as cost them in other goods. The raids, especially against the Xi Xia, may have just been out of need to replenish these stocks. Part of this too may have been encouraged by both states entering into a period of instability and poor emperors: as good an opportunity as any for the Mongols to attack. If they had aspirations beyond this, I don't think we can say, and it seems highly unlikely to me. Chinggis Khan's intentions here seem very localized.

In 1209 the Mongols invaded the Tangut Kingdom, making off with a great quantity of goods and forcing the Tangut King to submit to them (which entailed him sending a massive amount of tribute and slaves). Not long after his return from the Xi Xia, the Jin Emperor demanded the submission of Chinggis Khan (Temujin had undertaken a formal vassalization to the Jin in the past, and the Jin may have been surprised by his sudden unification of the steppes and understandably worried, but were distracted by war with the Chinese Song Dynasty to the south), who insulted the envoys and used this as his official declaration of war, invading the Jin Empire in 1211.

I think what turned Chinggis' mind to more permanent conquest than he initially intended was the success the Mongols had. While sieges were difficult, but aided by Jin defectors providing them siege weapons and knowledge, Chinggis Khan's army absolutely devastated in almost every field encounter. Though the Jin had mighty horsemen and huge numbers, they were unable to gain local superiority of forces and suffered from defections after defections. Within a few years, there were more Chinese fighting for the Mongols against the Jin that there were Mongols there!

By 1215, Zhongdu had fallen (with some difficulty), and forced the Jin Emperor to supply tribute and Chinggis withdrew back to Mongolia, but when the Emperor soon broke this agreement by fleeing to Kaifeng, war resumed. Was Chinggis intending a conquest of all of China now? Well, still it is not quite clear whether his intentions were to force the Jin to submit, fully conquer them or take all of China. I personally have seen no evidence he desired all of China yet, and the Jin were still a major obstacle. I think his intentions did not go much beyond forcing the Jin to be his vassal.

While in Mongolia in 1216, Chinggis sent some forces to bring rebellious tribes in Siberia and the steppe west of Mongolia to heel, as well as hunt down a son of a defeated enemy, Kuchlug, who had usurped power in the Qara-Khitai empire (parts of western Xinjiang/Kazakhstan). This was a major concern as Chinggis feared Kuchlug could use this as a staging ground to invade Mongolia, and when Kuchlug attacked and killed a Mongol vassal at Almaliq, sent his general Jebe to bring Kuchlug to heel. Chinggis had actually overestimated how secure Kuchlug's rule was though, as it turns out Kuchlug was greatly hated. Kuchlug's empire dissolved and submitted to Jebe as he passed through, and Kuchlug was finally hunted down in Badakhshan. In a flash, the Mongol Empire had greatly and unexpectedly expanded to the west: intended to finally capture a dangerous enemy, they had ended up incorporating a huge swath of new territory, making them neighbours with the also expansionist Khwarezmian Empire, which ruled from Transoxania through Persia.

Chinggis' initial contacts with Khwarezm were though, entirely trade focused. He sent envoys and merchants to establish trade links with the Khwarezm-Shah, Muhammad: together, their two empires could have secured a significant amount of the trade in and out of China, providing a safe route between both states. I want to really emphasis this: Chinggis Khan's first contacts with a state not immediately adjacent to Mongolia or encountered in Northern China were to encourage trade, wholly economic. Nothing suggests at this initial stage Chinggis intended to conquer or attack Khwarezm.

Of course, we know things didn't go quite so smoothly: I have a video providing overview here: https://youtu.be/0ct-dz_ad4k. Basically, a large trade caravan sent by Chinggis was betrayed and murdered by the governor of the frontier city of Otrar (the Khwarezm-shah's uncle). But even after this, do you know what Chinggis Khan did? He sent a group of envoys to find out why this had occurred, and give the Khwarezm-shah a chance to make recompense. Even after such a heinous assault, Chinggis Khan did not want to uproot his armies and move west, and still gave the Shah a chance to encourage trade. When the Shah insulted and killed these envoys, that was what finally brought Chinggis Khan to, perhaps reluctantly, invade the Khwarezmian Empire.

It seems Chinggis Khan greatly overestimated the Khwarezmians. On paper, they had immense military potential, and Chinggis Khan being unfamiliar with the Qara-Khitai realm he had now incorporated, may have been unaware had difficult it would have been for the Khwarezmians to mount an offensive towards Mongol territory. There had also been a brief engagement between Mongol (under Chinggis' son Jochi and the famed Subutai) and Khwarezmian forces in similar time to this, while the Mongols had been pursuing fleeing Merkit seeking shelter among the Qipchaq. What had not been apparent was how politically fragile the Khwarezmian Empire was, how most of its territory was only newly acquired, the ethnic tensions (Turkic garrisons and commanders vs Persianized populations) which hampered cooperation and how the over-confident Khwarezm-Shah Muhammad was simply not up to the task at hand. When Chinggis Khan's armies entered the Khwarezmian Empire at the end of 1219 (leaving a holding force in China under the commander Mukhali to keep up pressure there), the Khwarezm-Shah fled, leaving each city to fend for itself. Totally unexpectedly, but from late 1219 to the end of 1221, the Khwarezmian Empire utterly dissolved under a ferocious Mongol onslaught. Notable resistance came from a few individuals, like the Shah's son, the brave Jalal al-Din Mingburnu, but it must have been an absolute shock to the Mongols how total their victory was. It is here it seems the belief in Mongol world domination must have truly emerged. Basically, to paraphrase historian David Morgan, the Mongols came to believe they were destined to conquer the world when they realized that they were in fact, doing so. For how else could you have explained such a dramatic victory?

The Khwarezmian campaign laid the foundations for further Mongol campaigns in the west: during that campaign, Jebe and Subutai went on a phenomenal campaign through the Caucasus and into southern Russia, defeating a Rus'-Qipchaq force at the Kalka River in May 1223, bringing to the Mongols knowledge of the western steppe and to Subutai, a personal interest to return there. Continued campaigns to conquer and consolidate the remnants of the Khwarezmian realm brought the Mongols deeper into Persia and Iraq. In China, the brief respite allowed the Jin dynasty to hold on until 1234, which brought the Mongols into contact with the Southern Song Dynasty and their own eventual wars there.

The vast scale of the Mongol conquests was not something intended from the outset, but a staggered development, and as more and more of Asia came under their banner, the Mongols would become much more proactive in the spread of their rule.

Sources:

Allsen, Thomas T. “Mongolian Princes and Their Merchant Partners, 1200-1260.” Asia Major 2 no.2 (1989): 83-126.

Atwood, Christopher. “Jochi and the Early Campaigns.” in How Mongolia Matters: War, Law, and Society, edited by Morris Rossabi. Brill's Inner Asian Library, (2017) 35-56.

Barthold, W. Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion. Translated by H.A.R. Gibb. London: Oxford University Press, 1928. https://archive.org/details/Barthold1928Turkestan/page/n341

Biran, Michal. The Empire of Qara-Khitai in Eurasian History: between China and the Islamic World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Buell, Paul D. “Early Mongol Expansion in Western Siberia and Turkestan (1207-1219): a Reconstruction.” Central Asiatic Journal 36 no. ½ (1992): 1-32.

Golden, Peter B. “Inner Asia c. 1200,” in The Cambridge History of Inner Asia: The Chinggisid Age, edited by Nicola Di Cosmo, Allen J. Frank and Peter B. Golden, 9-25. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Jackson, Peter. The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

May, Timothy. The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires Series. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Sinor, Denis. “The Mongols in the West.” Journal of Asian History, 33 no. 1 (1999): 1-44.

Timokhin, Dmitry. “The Conquest of Khwarezm by Mongol Troops (1219-1221).” in The Golden Horde in World History, 75-86. Tartaria Magna Series. Kazan: Sh. Marjani Institute of History of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences, 2017.

Timokhin, Dmitry, and Vladimir Tishin. “Khwarezm, the Eastern Kipchaks and Volga Bulgaria in the Late 12-early 13th Centuries,” in The Golden Horde in World History, 25-40. Tartaria Magna Series. Kazan: Sh. Marjani Institute of History of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences, 2017

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Part three on the Qara-Khitai, this time detailing the reign of Kuchlug and Mongol conquest

#history#jackmeister#mongol empire#chinggis khan#genghis khan#youtube#medieval#mongolia#qara khitai#khitan#tarim basin#kashgar#khotan#taklamakan#uighur#jin dynasty#jebe#kuchlug#khwarezm#khwarezmian#military history

0 notes

Text

This Persian image shows a famous scene from Chinggis Khan's campaign against the Khwarezmian Empire. After taking the wealthy city of Bukhara, Chinggis Khan himself entered the city (one of the few times he ever entered a city). He asked if the great mosque was the Shah's palace, and after being told it was a palace of God, Chinggis had the shelves containing Qurans knocked over to be used as troughs for the horses.

Later, mounting a pulpit at the musalla, he ordered a gathering of the city's notables and here gave his famous speech.

"O peoples, know that you have commited great sins, and that the great ones among you have commited these sins. If you ask me what proof I have for these words, I say it is because I am the punishment of God. Had you not commited great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you."

Now, this story comes to us from 'Ata-Malik Juvaini, a man who worked for the Mongols some 20 odd years after this. Juvaini had a flair for the dramatic, flowery prose, and depicts throughout his work the Mongols as God's divine wrath. This, the veracity of this quote has been questioned (as we always should when a medieval source hands is a direct quote). I've been thinking on this, however.

Chinggis Khan made good use of propaganda in the conquests- against the Jin, he presented himself as restoring the Liao empire and liberating the Khitans from Jurchen rule to bring this important ethnicity to his side. In the Tarim Basin, his generals gave the order that all who submitted to the Mongols could worship who they pleased, destroying support for the fleeing Kuchlug. In Khwarezm, fake letters were sent to leading persons to sow discord, while numbers of the Mongol army and their penchant for utter destruction of resistance were spread extensively.

Chinggis Khan had long known Muslims in his retinue, and may have been aware of their penchant for determinism- that is, giving all misfortune as being product of God's will and displeasure. The seizure of Bukhara was early on in the campaign (spring 1220): thus, I suggest that Chinggis may have purposely spread the notion that he and the Mongols were a divine punishment sent by God himself upon the Muslim world. This would discourage dissent and resistance: for who could dare stand against God's wrath?

#history#mongol empire#chinggis khan#genghis khan#medieval#bukhara#islam#islamic history#wrath of god#uzbekistan#persia#juvaini#nomad#steppe nomads#eurasian history#mongol warrior#mongols

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yelu Dashi (r. 1134-1143) was the founder of the Qara-Khitai Khanate, and his grandson Yelu Zhilugu (r. 1177-1211) was the final ruler (Gur-khan) of that Khanate. The Qara-Khitai was a fascinating, but little known empire. The Khitan Liao Dynasty (907-1125) was quickly overrun by the Jurchen Jin (1115-1234) in the early 12th century, and Yelu Dashi, a Khitan noble related to the imperial family, fled China, crossing Mongolia and eventually making his way to central Asia, where he established the Qara Khitai. The Qara Khitai went on to control an area from Transoxania to the Tarim Basin, mighty empire combing Chinese-Khitan ruling customs over a largely Muslim population. After Dashi's death in 1143 the empire declined, and the long rule of his grandson Zhilugu marked the final years of the dynasty. Vassals broke away, financial crisis gripped the empire, religious factionalism began to tear it apart and his former vassals, the Khwarezm-Shahs, challenged and fought with him. The appearance of a Naiman prince, Kuchlug, fleeing the wrath of Chinggis Khan in Mongolia and welcomed into the Qara-Khitai, tipped the balance against Zhilugu. Even though he married a daughter of Zhilugu and was given titles and power, he betrayed his step father, raiding the imperial treasury and conspiring with the Khwarezm-Shah, Muhammad bin Tekish. In late 1211, Kuchlug captured Zhilugu while he was on a hunting trip, and kept the former Gur-Khan captive while claiming power for himself. In the end, Kuchlug's ascension brought Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Empire to Central Asia, now bordering the Khwarezmian Empire... To learn more about the Qara Khitai, check out my latest videos: Part One, the Rise: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k22BPOpihhQ Part Two, the Decline: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wj5MzSmo8-I

#qara khitai#khitans#liao#china#history#medieval#mongol empire#uzbekistan#bukhara#samarkand#balasagun#tekish#muhammad#shah muhammad#khwarezmian empire#khwarezm#qarakhanid#jin#central asia#jackmeister#youtube#chinggis khan#genghis khan#yelu dashi#dashi#zhilugu#kuchlug#nomads#khans#sultans

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kashgar Harvest Raid

Kashgar, and other major centres of the Tarim Basin, had long been vassals of the Qara-Khitai, but around 1211 began to revolt. In that year, Kuchlug, a Naiman prince who fled Chinggis Khan's conquest of Mongolia, had usurped power in Qara-Khitai, capturing the Gurkhan. Kuchlug's reign was characterized by mistreatment of his Muslim subjects (the largest and wealthiest demographic of his new empire), increasing taxation both in amount and frequency with which he collected it, a stark contrast to the lighter rule of the Gurkhans and quickly brought the displeasure of the populace. What exactly set off matters in the Tarim Basin is hard to say, as our sources confuse the timelines between them, but a combination of factors likely contributed to the violence. The Khan of Kashgar, imprisoned by the Gurkhans but released by Kuchlug, was murdered on his return to Kashgar, an affront Kuchlug could not ignore. An imam in Khotan, speaking out against Kuchlug's policies, was nailed to the doors of his own madrassa on Kuchlug's order, while a little north in the Qulja (Yining) region, a Qarluq Turk named Bozar seized power in Almaliq, declaring himself a vassal of Chinggis Khan (at that time just beginning his campaign in China against the Jurchen Jin). Further, Juvaini informs us that Kuchlug, a recent convert to Buddhism from Nestorian Christianity, tried to force his Muslim subjects to convert to Buddhism, Christianity or at least adopt the dress of the Khitans. Coupled with the general antagonism to Kuchlug's taxation policies and the general breakdown in Qara-Khitai authority due to Kuchlug's usurption and confrontation with his western neighbour, the Khwarezm Shah Muhammad, in addition to former vassals of the Qara-Khitai like the Qarluqs and Uighurs joining the Mongols, it is easy to see that this was a volatile climate. Kuchlug forces attacked Kashgar and the other revolting regions in the harvest season, destroying the crops every year for 3-4 years. The result was the revolt dying down due to starvation: Kuchlug then consolidated his victory by billeting his forces in the homes of the local populace. While for now the region was quieted, in 1216 Chinggis Khan, back in Mongolia, was able to turn his attention to matters closer to home, one of which was Kuchlug. Chinggis Khan's great general Jebe Noyan would invade the Qara-Khitai with 20,000, and he would take advantage of the latent hate for Kuchlug in the Tarim Basin. To learn more about the end of the Qara-Khitai and reign of Kuchlug, check out my video on this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RU_OQZS9TBE

#kashgar#harvest#raid#attack#medieval#history#asia#asian history#islam#islamic history#muslim#muslim history#uighur#uyghur#mongol empire#youtube#mongolia#genghis khan#chinggis khan#jebe#kuchlug#naiman#turk#qarluq#almaliq#tarim#tarim basin#taklamakan#khotan#yining

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Genghis Khan - Khan of All Mongols - Extra History - #4

some details left out in the telling:

Temujin and Ong Khan had actually campaigned against the Naiman around 1199: the Naiman Khan had died and split his realm between his two sons, Tayang and Buiruk who began scheming against each other. Temujin and Ong Khan attacked Tayang, but an army from Buiruk then approached them. According to the Secret History of the Mongols, Jamuhka was present alongside Temujin and Ong Khan (the Secret History of the Mongols sometimes does whatever it wants with the chronology, so we don't know if Jamuhka was actually there or not) and convinced Ong Khan to abandon Temujin in the night. The Naiman army then followed Ong Khan, defeated him and began raiding Kereit territory, and it was up to Temujin to defeat the Naiams and reinstate Ong Khan's control over his own territory.

After Ong Khan had betrayed Temujin, he allied with Jamuhka and they attacked Temujin. At the battle known as Qalqaljit Sands Temujin was defeated and someways, his followers dispersing and with a small band arrived at a Lake Baljuna. Here he made a vow with his followers to lead them to eventual victory, and they all drank from the waters of Baljuna. This became known as the Baljuna Covenant, which was quite famous to the Mongols but interestingly does not appear in the Secret History of the Mongols.

It appears than Temujin's brother Khasar had betrayed him to join Ong Khan and Jamuhka (he wasn't so keen on the upending of steppe traditions possibly), but had had doubts about it and returned to Temujjin, leaving his family behind. To ensure his brother's loyalty, he forced Khasar to kill an envoy of Ong Khan, preventing him from rejoining the Kereit Khan.

It should be noted that there were many other figures involved in the anti-Temujin coalition alongside Jamuhka and Ong Khan, which became problematic as they had different goals in mind, and lacked unity. Temujin used this to his advantage, as he knew this new alliance could not last long. He sent messages to a number of the leaders, reminding some like Ong Khan of past loyalties and issuing threats to others. This helped to disrupt an already shaky coalition, and by the end of the summer there were assassination attempts and betrayals, others deciding that they wanted to take the Kereit throne from the aging Ong Khan for themselves. Thus, by the time Temujin had regained his strength and forces and was ready to counterattack, Ong Khan had been isolated and was vulnerable.

After Ong Khan's defeat the conspirators coalesced around Tayang Khan of the Naiman as noted in the video. However they suffered from disunity. Tayang Khan wanted to draw the Mongol further into Naiman territory in a sort of extended feigned retreat. He was unable to get his brother Buiruk to supply forces for this defence though, and his own wife/step-mother Gurbesu, his son Kuchlug and his leading generals all accused him of cowardice and wanted to attack Temujin head on, which Tayang agreed to reluctantly. According to the Secret History of the Mongols, Jamuhka then spends the early part of the battle frightening Tayang Khan with stories of the invincibility of Temujin's forces (I think he describes Khasar as being able to eat a man whole at one point) and then retreats with his men and leaves Tayang to die. Temujin of course wins and the remaining steppe resistance is slowly destroyed over the following years.

While the Secret History of the Mongols says Temujin gave Jamuhka an bloodless death and says his spirit will look over Temujin's children and descendants, in the history of Rashid al-Din Temujin has Jamuhka slowly cut into pieces and screaming obscenities at him. Take your pick!

#chinggis khan#genghis khan#temujin#mongolia#history#secret history of the mongols#jamuhka#naiman#merkit#ong khan#tayang khan#toghrul#extra credits#youtube#educational#asia#asian history

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Perhaps the most daring of all Chinggis Khan's generals, Jebe's career with Chinggis began in 1201 after the battle of Koyiten, when Chinggis was still called Temujin and Jebe Zurgadai. During the battle he had fought with Temujin's enemy Jamuhka, and shot and killed Temujin's horse with an arrow. After the battle, Zurgadai either turned himself in, or was captured, and told Temujin that he was the one who and shot his horse. Admiring his bravery, Temujin took Zurgadai into his service and gave him a new name, Jebe, meaning 'arrow.' From then on Jebe became one of Chinggis' most loyal generals, taking on far flung missions and spreading the law of the Khan with his sword. Jebe was one of the most highly skilled cavalry commanders in history, as demonstrated repeatedly during the campaign against the Jin in China, taking heavily fortified cities and passes such as Tung-ching and Juyongguan with numerically inferior, but highly skilled, detachments, luring his foes into false retreats and falling upon them when they entered his trap. When the Mongols went west, it was Jebe who chased Kuchlug out of the former Kara-Khitai Khanate, and when the Mongols attacked the Khwarezmian Empire, it is no surprise that Jebe led the vanguard. With Subutai, Jebe would chase the Khwarezmian Shah Muhammad II to his death in the Caspian Sea, and then in a famous 'expedition' marched through Northwestern Iran, the Caucasus and the southern Russian steppe in 1223. It was here though, the Jebe's recklessness seems to have gotten the better of him: the Kipchak tribes fled the Mongols to join with some Russian princes, and together they marched on the Mongols. Jebe went on reconnaissance with a small party, but the Kipchak saw them and fell upon him. Poor Jebe was captured and executed, and it was up to Subutai to avenge him at the battle of the Kalka River. Jebe's fate was for a long time a mystery, but historian Stephen Pow, in his article "The Last Campaign and Death of Jebe Noyan," has shown that it is almost certain that Jebe died before the Kalka River: confusion came as Russian chroniclers were translated the turkic version of Jebe's name, Yama Beg, as Gyama/Hyema Beg, causing us to miss this information. Mongolian sources, out of respect or shame, gave us no detail on Jebe's final fate. For more on Jebe's campaigns, see my latest video on the Mongol invasion of the Jin Empire in 1211: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5RDRG3yGoqc

#chinggis khan#genghis khan#dschingis khan#mongol empire#history#medieval#asia#noyan#jebe#jackmeister#historical#jin empire#jin dynasty#china#chinese history#russian history#kalka river#subutai#iranian history#history on tumblr#history on youtube#youtube#historical artwork#my art#my drawing#horse#cavalry#horseman#warrior#mongol horde

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

All I want to do is trade

1217: While at war with Kuchlug, my army came in contact with the soldiers of Sultan Muhammad of Khwarazm. He is one of the most powerful leaders of our part of the world. He rules the West while I rule the East. I have no ill intentions against the Sultan for there is no reason for it. I simply wish to trade. It would be advantageous for both empires to acquire the goods and services of the other. I will simply offer him peace. Perhaps it will grant me my own piece of mind in this tumultuous time.

0 notes