#Mobile Suit Gundam Iron-Blooded Orphans Season 2

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I care them

#I don’t think any image describes the vibes of this throuple better than this one#I wasn’t expecting to ship these three so much going into this but here we are#season 2 better have the balls to make them canon or so help me#mobile suit gundam#iron-blooded orphans#mikazuki augus#kudelia aina bernstein#Atra Mixta#me rambles

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

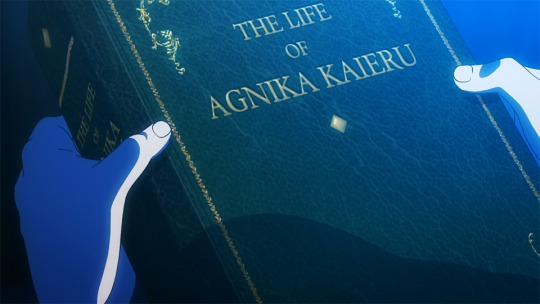

IBO reference notes on . . . the lie of Agnika Kaieru

This is a post about McGillis Fareed.

Originally presented as an antagonist ala the Gundam franchise's 'Char clone' archetype (named after Char Aznable, an expy of the Red Baron by way of the Last of the Romanovs), McGillis turns out to be one of Iron-Blooded Orphans' key protagonists, his initial appearances reframed by an eventual alliance with Martian mercenary group Tekkadan, home to the more obvious lead characters. In large part, it is his story we watch unfold, as he attempts to secure control over Gjallarhorn, the repressive extra-national military in which he serves.

And it's hard to discuss that story without reference to Agnika Kaieru, the man credited with founding Gjallarhorn to counter AI-controlled 'mobile armours' three hundred years earlier. The apocalyptic conflict between humanity and the armours known as the Calamity War is the source of the current social order, not to mention the titular Gundam mecha. Agnika is responsible for leading Gjallarhorn to victory, an achievement for which McGillis idolises him. He is also a non-character, haunting events solely through McGillis' commentary, at once vitally important and entirely absent.

I thought it would be interesting to examine how that works. I ended up writing 7000 words about it. Spoilers for everything and content warnings for mentions of child sexual abuse.

The character who wasn't there

If we take McGillis at his word, his personal philosophy was defined by reading a biography of Gjallarhorn's founder at a young age. More specifically, at a young age, while being sexually abused by his adoptive father, Iznario Fareed, who had extricated him from working at a brothel, a situation he was previously forced into after being abducted while homeless on the streets. The Life of Agnika Kaieru was a light in this darkness, offering a path out of a situation that, though seemingly improved from his original impoverishment, continued to be highly coercive and harmful. McGillis was made heir to a powerful family, yet had to sneak out of his patron's bed in the middle of the night, naked, with visible bruises across his body. He was desperately in need of hope.

The abuse appears to have been baked into this plot-beat from the start, with hints to it provided at multiple points during Season 1. Iznario being accompanied by a blonde boy and blonde young man (echoing the excesses of Carta Issue, a character who surrounds herself with McGillis lookalikes owing to an unrequited crush), McGillis' reluctance to spend the night at the Fareed estate, and the questions of legitimacy surrounding his inheritance all take on darker significance when the truth is revealed in Season 2. We may safely assume he was always planned to be reacting to this form of exploitation.

I suspect Agnika was a later creation. Comparing the outline of the Calamity War provided at the very start of the show to the ways it later becomes relevant suggests a considerable amount of fleshing-out in the interim. There are few outright contradictions, or at least, few we cannot explained by assuming in-fiction ignorance. Nevertheless, the importance of Agnika as a historical figure, the myths surrounding his mobile suit, and the very existence of the mobile armours each enter without previous set-up. This is inelegant, in the manner of much of IBO's exposition: workmanlike additions to propel the plot along, extending exactly as far as required and no more. But we cannot discount their importance to the final result and since McGillis aspires, in a very real sense, to become his hero, it is instructive to consider what the show tells us about Agnika.

Immediately we run into the fact we know nothing at all about him as a person. The only 'canonical' description of his personality was provided by the series' director, who compared him to 'the hero in a shonen manga': a charismatic character who always saves his friends. Apart from reinforcing my belief any spin-off set during the Calamity War would be more typical fare than Iron-Blooded Orphans turned out to be, this tells us little. Within the story as it plays out, Agnika is blank space. Being three hundred years dead, it does not actually matter what he was like – itself a statement about how people can be forgotten even when their names reverberate through history. Indeed, the thematic parallel to the fates of a large chunk of the cast is a potent one. Time has rendered Agnika a cipher, subject to the judgement of distant strangers, his exact morals and intentions long-since stripped away.

What remains are his legacy and beliefs. That we must speak of these separately is telling. The Seven Stars, descendants of Agnika's fellow Gundam pilots and Gjallarhorn's present-day leadership, show little deference to the man who commanded their ancestors. There are no statues memorialising him and though Gundam Bael has its attendant ghost stories, of Agnika's spirit living on inside and how it will only awake for his true inheritor, it is shuttered away, a monument nobody ever goes to see. One gets the strong impression McGillis is the only person to pay him more than lips service in centuries.

Consequently, McGillis' personal interpretation of Agnika's philosophy is the only window we get on his beliefs, and the most thorough explanation of that interpretation is given to his eleven-year-old child-bride, Almiria Bauduin.

Fairy tales told by a pied piper

From what we see on screen, McGillis is never overtly abusive towards Almiria, to whom he becomes engaged as part of a political scheme. He is pushed into the arrangement by Iznario and in the side-story covering its commencement, he goes out of his way to provide Almiria with the choice he lacks – something that spurs Almiria to form a genuine attachment to him. However, the engagement also serves his personal ambitions extremely well and he unquestionably manipulates her over the course of it (hard to think of another term to describe comforting her on the loss of her brother Gaelio, for which McGillis is himself responsible). We could and probably should label his apparent concern for her emotional wellbeing and indulgence of her desire to be seen as a grown-up as an attempt at grooming her, not in the sexual sense, but to make her a more amenable chess-piece. On the other hand, McGillis prevents Almiria from killing herself when the truth comes out, at the cost of an injury that severely disadvantages him in battle shortly thereafter – a notable action when her political utility has just evaporated. On the other other hand, this incident prompts him to describe her, quite disdainfully, as 'troublesome'.

What I'm saying is, the question of whether McGillis sees Almiria as a tool or somebody he truly cares for is thorny, as it is for virtually every single character with whom he has a meaningful relationship. Nevertheless, I think we are meant to believe he is being honest when he talks to Almiria about The Life of Agnika Kaieru. What he says fits his actions elsewhere and there are no on-screen indications he isn't being truthful – at least from his perspective – when he credits Agnika's principles with 'saving him'.

McGillis states Agnika wanted a world where “humans could live as humans”; that is, where humans of all backgrounds could compete fairly to achieve their dreams. To a child of low-birth, abused behind closed doors, this is an enticing prospect. McGillis goes on to entice Almiria in turn with the promise of 'loving whomever you wish' and of neither of them being mocked for the age imbalance between them. He concludes the scene by saying it is time to “pry open the door to that world with my own two hands.”

A few episodes later, in an internal monologue, he refers to Agnika as the “greatest symbol of power the world had ever seen. Authority, vigour, might, capability, vitality, influence, as well as brute force.” Inspired by this man's life story, he is determined to usurp rule over Gjallarhorn and finally address the want of power that had defined his own life since birth.

Like everything to do with Agnika, what this tells us about his principles is somewhat vague. Quite literally the child-friendly version (sort of; McGillis openly tells Almiria he contemplated suicide prior to reading the book and is likely a poor judge of age-appropriateness). Still, the philosophy described combines individualism with egalitarianism. The stated goal is a level playing field, free of artificial advantages like wealth or social status, where everyone can pursue their dreams as far as they are each able. This is implied to be a natural state for humanity, such that achieving it would be a form of reclamation. Further, the kinds of power McGillis lists are personal – physical strength, intelligence, charisma – and he works obsessively to cultivate them. We don't get confirmation that self-improvement is another of Agnika's ideals, but it would fit from what is presented.

If you are anything like me, your brain will have turned to all sorts of weird capitalism fans and their buzzwords for justifying frantic competition between people at every level of society. Phrases like 'personal responsibility', 'rugged individualism', and 'rational self-interest', possibly with a side-helping of – gods help us – libertarianism. You may also be asking, if this is what Gjallarhorn's founder espoused, how did it end up enforcing disparities between different populations, oppressing workers and maintaining social hierarchies, at large and within its own walls?

To which I might reply, have you looked at what all those weird capitalism fans get up to, recently? This is an unsatisfying answer, though, and to properly examine how Agnika's legacy intersects with the dreaded c-word, we need to take a couple of side-steps, starting with why it should be a natural connection to make within the context of this show.

A digression into narratives about capitalism

Iron-Blooded Orphans is one of the few entries in the franchise to directly engage with capitalism as a major source of global problems. That probably sounds a little strange if you're aware of the the reputation Gundam has as a whole, so let me explain.

[Also, let me remind everyone the definition of capitalism is “an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit.” (Wikipedia; emphasis mine). It's worth being exact.]

When the concept of space colonies is introduced in 1979's Mobile Suit Gundam, they are framed as a response to global overpopulation and the consequent ecological decline of the Earth (pause to appreciate the massive fuck-off dog-whistle; we'll come back to that in a second). The war the show depicts is presented as a matter of sovereignty, whereby those offloaded into orbit rise up against rule by an indifferent terrestrial government. The colonies themselves are cities built within artificially landscaped environments inside O'Neil cylinders. They do not appear to serve any commercial purpose in and of themselves; when we see labour happening in space, it is in service to the colonies, rather than something they are for (the Zeon miners in sequel series ZZ; there is also the fuel-collecting Jupiter Fleet but they are a very odd entity and not fleshed out).

Contrast this to IBO where Mars' utility as a source of 'half-metal' is of paramount importance to its political and economic position, and the space colonies are explicitly shown to be factory complexes, company towns, resorts, and prisons. The middle arc of Season 1 is focused on a workers' revolt against the corporation running a particular group of colonies, the Dorts, while the impetus behind spin-off game Urdr Hunt is the lead character's desire to transform his home's fortunes by making it a popular tourist destination. There are also mentions of 'resource satellites' and glimpses of what appear to be colonies built to mine asteroids. And true, it isn't stated whether all the colonies originate as extractive operations and production centres. But those purposes are depicted the reason they are maintained to the present day, removing such dirty businesses far above the 'precious', 'unsullied' Earth (cue 'The Lightship', played with maximum irony).

[Side-note: the Dort Company runs its colonies as a 'public enterprise on behalf of the African Union', implying state ownership. However there are multiple references to 'rich factory owners from Earth', suggesting private control. Best I can figure, the colonies are state-owned while the production facilities inside them belong to private companies? Since everyone appears to work for Dort (every worker we see wears the same green jacket), I'm not certain how that functions. Perhaps the workforce is leased to private factories via the Company? That would be fittingly grim.]

Now to be clear, I am not claiming Gundam as a whole doesn't tackle problems caused or exacerbated by capitalism. The introduction of Anaheim Electronics into the original Gundam timeline marks clear interest in exploring the influence of corporate entities on warfare. We may also – from the outside – interrogate overpopulation concerns as deflecting blame from capital's destructive activities, going hand-in-hand with racism over migration, and obfuscating who exactly gets sent to 'colonise the unknown' (spoilers: it's the poor and vulnerable). I'm unconvinced the original run from Mobile Suit Gundam to Char's Counterattack is intended as commentary in this manner; equally, I don't think it's hard to get there (as Gundam Unicorn somewhat demonstrates).

What I'm trying to articulate is a distinction between 'being about a problem' and 'naming capitalism as the cause'. Most Gundam series tend to depict capital as part of an amorphous blob of 'Earth-sphere corruption' or 'greedy elites'. Even Anaheim acts as a third party in the Earth/space conflict, taking advantage of the war rather than shaping the fault-lines along which it occurs. Additionally, actual money very rarely tends to be a factor in the plot. Groups like Celestial Being from Gundam 00 appear to possess near-infinite budget; Gundam Wing's itinerant teenage terrorists have only erratic and arbitrary issues obtaining supplies (where are you getting the damn ammo, Trowa?!); and even in The Witch From Mercury, where you'd really expect expenditure to matter, it… doesn't. G-Witch toys with access to funds and the requirement to be profitable early on, but overall is more a courtly drama in business drag, unconcerned with why corporations work the way they do. Issues such as the exploitation of vulnerable populations for the sake of driving down costs are gestured to without becoming strictly plot-relevant.

Meanwhile over in IBO, the poverty of the Martian characters is an ever-present threat and come the denouement, whether they have any money left is of paramount importance. The show tells us bullets have a price-tag, using this to drive actions inside a world run for the sake of profit. It is mentioned that productivity in the African Union's colonies is expected to drop following the Dort labourers wining better working conditions, a boon to the competing economic blocs that leads to one of them sheltering Tekkadan in gratitude for helping bring this change about. The reason co-main character Orga Itsuka does not survive episode 48 is because arms-dealer Nobliss Gordon thinks it will be financially advantageous to have him killed. That fellow businessman McMurdo Barriston extends limited aid to Tekkadan after publicly cutting them loose for the sake of the Teiwaz conglomerate's reputation and revenue is highly relevant to his characterisation. And Teiwaz itself is run like a mafia, a riff on yakuza practices that erases the line between big business and organised crime – a hell of claim to make in a story where another of the leads' entire goal is uplifting Mars by playing the economic system.

Now, in my reading the major theme running through Iron-Blooded Orphans is exploitation. An acute depiction of how capitalist societies operate – the amorality of the profit motive, the colonial underpinnings, the sheer, monstrous cost – is a subset of this. I don't feel it's any surprise that an attempt to realistically depict child soldiers and other exploited groups should lead to a detailed rendering of the gears in which the world is currently caught. Equally, I don't think it fair to reduce IBO to being about capitalism, full-stop. Patriarchy, slavery and repressive class structures all have older roots and there is an argument to be made that where it touches those things, the show cares less about them as artefacts of modern economic arrangements than as evils in their own right.

It still manages to say stuff about the functioning of capitalism with more bluntness than most pieces of fiction I've encountered and, speaking as an Englishman, the thing that strikes me most is the decision to make the lynchpin of its world an aristocratically-led military force.

A further digression into aristocratic fables

Aristocracy means 'government by a hereditary elite'. It is sustained via wealth passed down through generations of a small group of families and was one of the key mechanisms by which the feudal system operated, prior to the slow capitalist revolution of the 16th to 18th Centuries. It is often treated as obsolete, having been superseded by more modern forms of 'being rich'. Certainly it seems quaint in these days of tech billionaires and oligarchs to talk of descendents of feudal lords who prize family trees traced back to William the Conqueror.

What you have to understand about the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (official name used with illustrative intent) is that this country never properly rid itself of its aristocracy. We are a monarchy. Our parliament includes a House of Lords. And while these are both vestiges of earlier systems, they are neither of them ceremonial. The Lords and the Crown possess actual power that can affect decisions made by the House of Commons, our democratically-elected governing body. The Lords (who are not elected and include those appointed for life alongside ninety-two hereditary positions [this was a compromise]) can review and send back certain types of bills passed in the Commons, delaying their introduction into law. Meanwhile the Crown technically still holds an absolute veto at the end of the legislative process, which only by convention do they not use (royal assent is required for any bill to become law; apparently the last time it was withheld was 1708, but the threat remains and the Crown continues to interfere in proposals affecting their interests).

As you might expect, there have been murmurings for years about replacing the Lords with elected officials and we all like to pretend the King just exists for show. Regardless, these institutions – hundreds of years old and holdovers from a completely different social and economic order – persist because the aristocracy remains a useful tool of the modern British state. The Royal Family can be said to be its advertising wing, not in the sense of attracting tourism but of going around shoring up foreign relations, to help keep Britain the fifth richest country in the world. These diplomatic efforts are a key reason why they are worth the maintenance costs (and the noxious scandals). However it goes deeper than that.

Kings and queens don't make sense without the idea of hereditary superiority, and even with its overt political power reduced by changing times, the British aristocracy continues to shape our upper classes. We have an entire parallel school system preparing the children of the wealthy for life running the country. Our public schools (fee-paying schools open to all who can afford them; we call the free ones 'state schools') have been educating the sons of the 'best families' for centuries. They were the source of the officers and administrators who maintained the British Empire and they continue to be where a massive proportion of our diplomats, politicians, journalists, civil servants, and military leadership receive their education.

This system, funnelling kids through schools like Eaton and Harrow to Oxford and Cambridge Universities, is a factory for class solidarity. It allows students to network and, just as importantly, instils in them the signifiers of being 'the proper kind of person'. Ways of speaking. Ways of dressing. An awareness of who they should defer to and who they can look down on, so that they can be recognised by other alumni as 'correct'. Trustworthy. Reliable.

Above all, it reinforces the notion they have both a right and a responsibility to lead.

Because that's the heart of the lie nobility tells: 'there is something about us that means we must rule over them.' If Britain no longer entirely subscribes to this quality being inborn, it can at least be taught to those of the right stock, bringing them a little closer to the true aristocracy. They can elevate themselves above the plebs, as diligent servants of the Crown, who remains the untouchable pinnacle of quality. [Translation note: 'the Crown' refers to both the reigning monarch and the state. They are functionally the same thing. That's what being a monarchy means.]

Thus, the Empire was able to send its younger, weirder sons out to plunder far-off lands, and produced many an honourable sort to lead thousands against machine guns in Europe, and, in a post-imperial age, Britain can still present an impeccably polite face to the world, to negotiate better deals. Diminished as it is, the aristocracy's shambling husk continues on, manufacturing not the capitalists per se (although the successors to the original land-lords are hardly above enriching themselves and plenty of our lifetime peers are people who've run successful businesses), but the supporting apparatus for capitalist operations. The grease on the wheels and a permanent roadblock along the road to meaningful social change.

You literally cannot have equality if there's a guy at the top who gets a stupid hat and ungodly amounts of influence just for who his parents were.

The wrong story, at the right time

It isn't hard to imagine about how it happened.

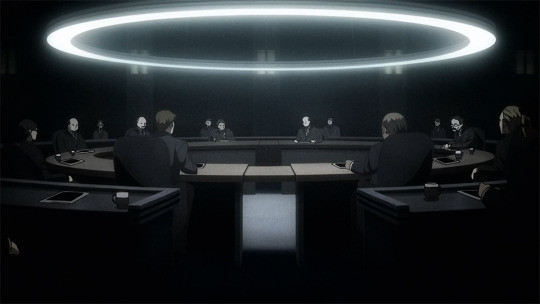

Gjallarhorn is the only significant military force left standing after a quarter of a solar-system-spanning human race has been exterminated. Faced with the task of reconstructing civilisation, it splits the world into four blocs for easier administration, abolishing the old national borders. At those blocs' request, it then applies the same reorganisation to Mars and Jupiter, the better to funnel resources towards restoring the Earth. Throughout, it maintains the position of a neutral arbiter; Gjallarhorn was formed to stop the War; now it must ensure there will never be another.

To this end, the tools that allowed it to triumph – the Alaya-Vijnana augmentation technology and the Gundam frames that meant flesh and blood could out-compete tireless machinery – are buried. Victory is instead attributed to the resilience of pure, unadulterated humanity. The pilots slew the monsters not thanks to their equipment but their innate ability. The greatest among them are heralded as champions and natural leaders.

It is a small step to decreeing that their children will inherit their positions. Innate qualities can be passed down and heirs, raised in the image of their parents. Maybe this is an extension of those traditions from which sprang duellists bearing red flags. Maybe it is merely a result of the new-born legends. What matters is, Gjallarhorn endures, guided by its seven stars.

Over the following centuries, the system embeds. The ethos of human purity takes hold, measured by distance from the homeworld. Unfortunates born to space or on distant, dusty worlds posses utility for digging up half-metal or labouring in orbital factories but have no place inside Earth's atmosphere. They would make the place untidy, now the scars of the War are scrubbed away. Those who seek to upset this situation are dissuaded. Those subjected to augmentation, dismissed as subhuman. The peace is kept.

Sadly, new generations of the ennobled families lack the moral fibre of their forebears, accepting bribes, pushing the boundaries of Gjallarhorn's neutrality. There are rules and those tasked with enforcing the rules and yet still the rot spreads. These younger generations lack the moral fibre of their vaunted forebears. A sad decline.

Or perhaps that is bullshit and they are exactly the same: people come into power, who will justify anything for the sake of never giving it up and ensuring that all things flow towards the centre.

Gjallarhorn is the armed wing of the Earth super-state, operating for the benefit of the whole despite competition between the individual blocs. That is to say, it is the army of a capitalist state writ large, in the usual manner of sci-fi magnifying things across time and space. Broadly, a state's purpose under capitalism is to facilitate the smooth running of private enterprise by maintaining infrastructure, providing a workforce, and destroying anything that gets in the way of expansion. Tradition, upper-class solidarity and ideological frameworks all help hold the arrangement together. It is useful, after all, to train people to believe they're supporting a grand cause when they are in fact facilitating exploitation and theft for the benefit of someone else.

And it is here we must turn our attention back to The Life of Agnika Kaieru. Above, I glibly compared the things McGillis says Agnika stood for to capitalistic propaganda. What I mean is that it reads as the ideology surrounding free-market capitalism, where companies are released from all restraint and allowed to compete irrespective of consequence. This is often said to fuel innovation and create a healthy market that will – somehow – benefit everyone, despite observably driving owners to increase profits at the expense of large numbers of people, including their customers.

In that context, claiming you want to ensure everyone competes 'fairly' is disingenuous, since it entails the removal of both limitations and safety nets. No artificial advantages and reliance solely on personal strengths means those who are old, disabled, or otherwise lacking Agnika's stated virtues will automatically be left behind. This is not hypothetical; I see it around me everyday, as a result of policies predicated on exactly this basis, just as we see it represented in IBO by a wide-scale absence of social support and characters too vulnerable to survive a free-for-all (Atra, Builth, the Turbines, in flashback). But the ideological statement elides such problems.

Given the title of the biography, I assume it dates from after Agnika died. Any impression derived from it must therefore be suspected of being what Gjallarhorn required him to have believed. Historically, both aristocracy and capitalism alike have benefited from this kind of distortion, so it would be no great surprise if the book turned out to be more PR than honest report. While Agnika's principles are incompatible with the hereditary advantages enjoyed by the Seven Stars, there are ways to read them as being aligned with the wider social and economic arrangements. As such, it is entirely plausible the way he is remembered was designed to support those arrangements.

The right story, at the wrong time

The rhetoric of McGillis' attempted coup centres Gjallarhorn's failure to adhere to its original values, citing unwarranted attacks against civilians and inference in Earth politics. The Seven Stars must be replaced with sincere believers to correct a drift away from what Agnika intended. McGillis outright proclaims his 'revolutionaries' have the truth of Gjallarhorn on their side.

Even if this is a calculated stance designed to rile younger officers into being the army he requires, McGillis' internal monologues reveal a commitment to the ideal of the individual seizing their dreams through sheer personal strength. He seeks not only to prove this is possible, but also to inspire those who cower because “they don't know how to use their fangs” into following his example. From what we see, he has taken Agnika's words – as they were relayed to him – as gospel.

Is his interpretation correct? And if it is, was it what Agnika believed, or simply what it was useful for him to say? McGillis is manipulative, spinning tales to make others do what he wants. Was his idol the same, pre-empting biographical distortions by espousing a finely-tuned message that would reassure the masses while he built a system geared toward curtailing the power of all but a few?

Trick question. There's no answer in the text. As I said, Agnika isn't a character; what he really intended is irrelevant and therefore not present. Yet a distinction must be drawn between what is said publicly and what is said behind the scenes. This is a layering IBO captures via Rustal Elion, McGillis' rival for control of Gjallarhorn, who out-manoeuvres and defeats him. Rustal is a pragmatist unencumbered by quasi-mystic belief in Agnika or some 'true purpose' to Gjallarhorn. He does whatever it takes to best McGillis, casually breaking centuries-old weaponry restrictions and even provoking a fresh war to undermine his opponent's plans – all while presenting as a bastion of lawful rule. Privately, he admits to being 'shady', willing to deal with whomsoever furthers his goals (e.g. Nobliss Gordon, who starts violent uprisings to spur sales of his merchandise). It is this capacity for realpolitik that means Rustal comes out on top.

The narrative does gesture at motivations beyond self-interest. When Rustal reforms Gjallarhorn in the wake of the Seven Stars decimation at McGillis' hand, he abolishes the aristocratic council (of which he is also a member) and replaces it with a more democratic form of governance. That he is immediately elected to the role of supreme commander gives us some reason to doubt his sincerity. Offsetting this, he is also shown to be working towards the abolishment of slavery in his society.

Regardless of his exact degree of progressiveness, however, Rustal appears entirely uninterested in changing what Gjallarhorn is for. See, institutions and social structures have specific purposes, which need not be the ones they claim, via statements or appearances. A capitalist business may claim to exist to provide a product or service, but its actual purpose is the generation of profit. The police may claim to be an institution of citizen protection, but their purpose is the enforcement of the law, which can be detrimental to some or all of those selfsame citizens.

Gjallarhorn's purpose is to control the colonial holdings of the Earth and maintain the current division of the world. They administrate the extraction of resources, quash attempts at social change, and crush resistance to exploitative business practices. Moreover, Rustal is certainly well-aware this is what his job entails. It is his fleet that carries out a calculated massacre of the Dort workers' unions when they push for better conditions and he personally orders an orbital strike on defeated child-soldiers as an exercise in image management. His reforms thus smack more than a little of an army or a weapons manufacturer improving its hiring policies: sure, they now employ women and members of minority groups; they still exist to kill people.

For these kinds of entities, purpose is all-important. You can dress them up however you want, so long as their function continues to be carried out. I bet, when I described my country's persisting aristocratic elements, you immediately went, “that sounds like [mechanics of regional upper class and attendant justifications for social division].” Yes. Precisely. We don't have feudal system holdovers at the centre of our society because they're the most efficient or only means of fulfilling those roles. They're simply the ones that make the most sense at this point in our history. A different environment would necessitate a different form, but the function would remain.

[I am glossing over the mutability of function here – the power of the king has reduced greatly via political and economic shifts, so he's no longer performing quite the same role as his ancestors – but hopefully you get what I mean.]

Rustal's reforms are an illustration of purpose superseding form. At the end of the show, the narration informs us trust in Gjallarhorn has been restored, indicating an end to meaningful opposition to what we have seen it do. Similarly, when Rustal states that the organisation's history matters more than its mythology, he is saying it has largely been operating correctly and should continue to do so in the future. The public claims can be altered, the set-dressing reworked. The function remains.

Poor delusions

Like the British state and its equivalents, Gjallarhorn is draped in heroic, mythological imagery. From uniforms to equipment naming conventions, it presents as grand and noble, even possessing heraldry, as if originating in a gathering of brave knights. We, the audience, know that this is a veneer plastered atop the material reality. Scenes of its foundation are comparatively mundane: sober men wearing drab suits, shaping the future with the stroke of a pen. The dress-up played since is pure embellishment.

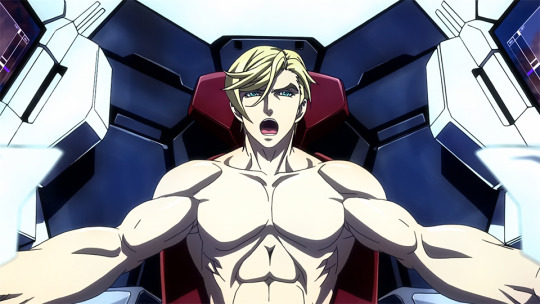

McGillis, however, takes the imagery seriously.

His plan hinges on 'awakening' Gundam Bael and being 'accepted' as its new pilot, fulfilling an old rule/tradition whereby whoever possesses this particular mobile suit is the undisputed leader of Gjallarhorn. By taking a disgraced Iznario's place among the Seven Stars, augmenting himself with an Alaya-Vijnana system, and capturing the facility containing Bael, McGillis intends to anoint himself the new Agnika. At a stroke, he believes he will gain the loyalty of all Gjallarhorn forces on Earth and thus the military strength necessary to defeat Rustal's Moon-based Arianrhod Fleet.

For reasons I'll detail another time, I don't think his strategy is necessarily ridiculous. But it doesn't work. The other Seven Stars do not automatically bow down to Bael's new pilot, instead adopting a neutral position awaiting the outcome of the impending battle, and there is no mass uprising among the ranks below them. Since Rustal otherwise commands an overwhelming number of troops, this turns the conclusion into a foregone one. The few who do join McGillis' cause are annihilated and he is forced to retreat, eventually dying in a one-man attack on the Arianrhod flagship.

It must be stressed that McGillis isn't stupid. He is a canny political operator who correctly identifies the biggest obstacles to success, and while his analysis of Gjallarhorn's corruption is deployed principally as a rhetorical tool, he's not wrong. The leadership are complicit in a lot of extremely shady activity, including experimentation with Alaya-Vijnana technology, contravening the taboo against augmentation their ancestors propagated. They do act against their publicly-stated values, to the detriment of ordinary people and in the interests of those who benefit from a hideously exploitative system.

His mistake is to treat this as a bug, rather than the feature we might more correctly diagnose it to be. Within The Life of Agnika Kaieru, McGillis believes he has discovered the hidden truth about Gjallarhorn. He imagines by setting Agnika aside, the Seven Stars obfuscated mechanisms to curtail their authority and an ethos more welcoming to people like him. (There is a lot we could discuss about the ways McGillis is immunised against some forms of bigotry by his station, despite his illegitimate status, and how he exploits more disadvantaged soldiers like Ein Dalton and Isurugi Camice for his own ends. It's just, that'd be another two thousand words and I really need to wrap this up.)

Yet if we follow Rustal's advice and heed history, the timeline shown in Season 1 has Gjallarhorn dolling out sections of Mars to the blocs a mere three years after the Calamity War ended. Among the many things we don't know about Agnika is if he survived the War, but whether he did or not, his organisation pretty instantly became a tool of social division and exploitation. The most we may allow is that its original purpose was truly noble. Its actions once the apocalypse had been averted speak for themselves.

This has been long walk, I suppose, for the fairly succinct summary of McGillis as a character who rejects private truth in favour of embracing a public, propagandising lie. I am compelled by the idea even so. Capitalism is far from the only system to have claimed universal virtue while benefitting merely a select few, but it has gone uniquely hard on the idea 'you can make it too'. Given IBO's uncluttered depictions of a world run for profit (with the complicity of ostensibly non-capitalistic institutions), taking a cynical read on Agnika's supposed ideology is trivial. Human triumphalism and Gjallarhorn conceptualised as the arbiter of fair competition dovetail into the show's unjust present in a manner too neat to discount. More than anything else, the choice McGillis makes is a common one in real life.

Sometimes, that's a positive thing, pushing people to insist on making promises come true to the detriment of the swindler proffering them. Others, it is a source of profound disorientation, leading in very dark directions as blame for the dissonance is attributed to anything but the root cause.

[This seems is as good a juncture as any to remark that McGillis is not a proponent of anything we can easily label fascistic. He focuses on individual freedom irrespective of national identity; he is attacking people genuinely perpetuating his world's ills; and he definitely doesn't bother courting a disaffected public by playing to middle-class anxieties. He doesn't need to. His plan is to enact a coup from high up inside a military hierarchy, while promising to lessen the force exerted against society. Though there are links to be traced between his ideology and fascist rhetoric, it isn't the avenue his circumstances compel him to go down.]

[I am 100% certain he would've gone in that direction if they had, but that's a counterfactual, not what the show actually presents.]

How McGillis got to where he did is another of IBO's many examples of adaptations to extremis that look utterly bonkers when seen at a remove. An outsider, thrust into the realm of a vicious upper class, he accurately declared the whole thing a nest of lies and hypocrisy. He could never buy the pretences it sold, to others and to itself. His very existence was damning disproof. Then, at his lowest ebb, he found a story about what it should be and that – that he bought, hook, line and sinker.

Already primed to consider power the be-all and end-all of life, he took Agnika's story as a guide to gaining the upper-hand, going so far as to tell Rustal (then a young adult) that the only thing he now desired was Bael. Though it seems he lapsed into a wait-and-see approach between prepubescence and his mid-twenties, witnessing children from Mars fighting using Gundams makes him believe destiny is taking a hand in events and the time has come to act. He betrays Carta and Gaelio, his two closest friends, both heirs to other Seven Star families, for the sake of clearing his path forwards. These were the first people to treat him like a normal child and he admits with his dying breath that he reciprocated their affection. This was part of why he killed/attempted to kill them: in their company, he started losing the will to pursue his dream, put off guard by finally having something positive in his life. So he chose to violently reject them, unable to give up on what he'd started.

That could easily be McGillis' epitaph. He is characterised by an overwhelming commitment to seeing through his power-grab, even if it means fighting an entire fleet to go personally kill Rustal. This is very far from a sane response and we might say likewise about everything he does prior. From his gleeful divinations at the sight of ancient relics, to his rapturous exultation on activating a machine he knows just required the appropriate brain/computer interface, the personality lurking beneath his habitually polite mask is little short of unhinged.

Which is of a piece with a group of teenage orphans clinging tight to the idea a good life lies just beyond the next battle, having internalised that proving their strength is the only way to survive. McGillis has to think taking on Agnika's mantle will bring him what he wishes, because otherwise his actions have been for nought, nothing can be changed, and the misery he endured is inescapable. It's the same self-reinforcing spiral, turned up to eleven.

(Re)imagining the world

In the final outcome, Iron-Blooded Orphans refutes McGillis' individualism, albeit not without caveat. Destabilising the Seven Stars creates space for incremental change and self-interestedly assisting independence activists lays the groundwork for Mars' eventual freedom from Earth. McGillis does create a “storm in this stagnant world,” with lasting consequences regardless of how swiftly it subsides. Nonetheless, his death is a futile one compared to the other causalities during the finale, who all manage to make their last acts count for something. Where Tekkadan share a mutually-supporting community – they are a 'pack of wolves' – he stands alone and saves nothing of what mattered to him.

As I said above, I don't want to treat IBO as a story solely and absolutely about capitalism. In a similar vein, I'm not trying to position an interpretation of Agnika as a vector for capitalist propaganda as the intended one. There are multiple moving parts here, spinning out from that serious consideration of child-soldiers as more than just a trope in fiction aimed at teenagers. My read on those parts is contextualised by my cultural background (I do now want to look into how Japan's own aristocracy mutated with their forced induction into global capitalism).

At the same time, McGillis indisputably misapprehends how a structure within a capitalist environment works because he wants to believe a version of what says about itself. And The Life of Agnika Kaieru is an artefact of that environment. Even without knowing more about its authorship, publication or veracity, and setting aside what McGillis brings to the table (his desire for power was set years before he'd heard of Agnika), the fact he finds it in Iznario's library speaks volumes. Biographies are not neutral objects. As alluded to above, the act of public remembrance shapes culture and hence society. I think it both reasonable and interesting to look at McGillis' arc with the assumption the book is ultimately commensurate with everything he was reacting against.

What would have happened had McGillis won is another moot question when the narrative hinges specifically on his failure. But a land of competition, overseen by the supreme authority of Gjallarhorn, where the only moral law derives from the dreams of the strong?

Perhaps the most damning thing to be said of McGillis' principles – of Agnika's principles – is that they would produce a world functionally identical to the one we started with.

———

Postscript:

For the sake of absolute clarity, I do not believe whether a story is about capitalism or not has any bearing on its quality. My discussion of the other Gundam shows is intended purely to highlight what I see as a fundamental difference between what they are doing and what IBO is. I don't think it is a problem that G-Witch is a personal/courtly drama, or that Wing is focused on fighting in a more philosophical than material sense, or that the franchise has overall tended towards addressing conflict per se, without any serious interrogation from an economic angle.

Stories can only fail at what they attempt, not at what they don't.

I nevertheless stand by what I said. A piece of fiction concerned merely with some generalised notion of 'human greed' is not about capitalism in any meaningful sense, and I fear that's where most Gundam shows land, one way or another, when they touch on corporate interests.

[Index of other writing]

#gundam iron blooded orphans#gundam ibo#g tekketsu#tekketsu no orphans#gundam#mcgillis fareed#agnika kaieru#gjallarhorn#capitalism#reference#notes

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edit: Please note that as of 08 Oct. 2024, Season 1 is no longer available (Season 2 is still available to watch however).

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five underappreciated anime that I would recommend!

1. Canaan (2009)

This is, from what I understand, an adaptation of a side-story chapter for the visual novel series 428: Shibuya Scramble, guest-written by Nasu Kinoko and guest-illustrated by Takeuchi Takashi. That is to say, the Type-Moon guys — the creators of Tsukihime, Kara no Kyoukai, and the now-legendary Fate/Stay Night. However, Canaan doesn’t take place in the Type-Moon shared universe(s), since it’s for another company’s property.

That being said, the anime adaptation is quite comprehensible on its own terms, likely due to the adaptation being written by the prolific and highly skilled screenwriter Okada Mari (Hanasaku Iroha, O Maidens In Your Savage Season, Mobile Suit Gundam: Iron-Blooded Orphans, Maquia). Her writing imbues the narrative with enough emotional intensity to make up for the occasionally-convoluted nature of the plot, and the backstories of the characters are hinted at just enough so that the viewer can understand their relevance, without taking up too much precious screen time. It can be a little hard to follow at points, but I ended up understanding it decently well anyway.

The production values are very high indeed, due to the anime being produced by P.A. Works, and directed by Andoh Masahiro (Sword of the Stranger, Hanasaku Iroha, O Maidens In Your Savage Season). The action animation is consistently stunning, the characters are beautifully expressive, and the overall look of the show is fantastic.

And the voice acting is an absolute treat, with the lead role of Canaan herself taken by Sawashiro Miyuki, the antagonist role of Alphard taken by Sakamoto Maaya, and Nanjou Yoshino in the role of Oosawa Maria, the POV character for a lot of the story. The supporting voice cast is packed with talent too — Hamada Kenji, Tanaka Rie, Nakata Jouji, Tomatsu Haruka, Hirata Hiroaki, Noto Mamiko, and even Ootsuka Akio in a minor role!

The premise is sort of a science fiction type of thing, but set in the (quasi-)contemporary location of 2000s China, where outside of the sci-fi conceit, the setting is largely realistic. The tone and mood is mostly that of an action thriller, with some nail-biting suspense here and there, but there are some beautifully soft and tender moments as well — often involving Canaan and Maria. Yes, folks, this has yuri in it, although it’s (strongly) subtextual.

Anyway, I would recommend this to people who love Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, Kara no Kyoukai, Fate/Zero, and probably also Cowboy Bebop.

2. Tetsuwan Birdy OVAs (1996)

This is distinct from the later adaptation of the original Tetsuwan Birdy (Birdy the Mighty) manga, called Tetsuwan Birdy Decode, which came out in the late 2000s — this one came out in 1996 and was produced by Studio Madhouse in their prime.

The main characters are Senkawa Tsutomu (voiced by Iwanaga Tetsuya), a hapless teenager who gets accidentally killed(!) by an alien spaceship on his way to school one day, and Birdy Cephon Altirra (voiced by Mitsuishi Kotono), a human-looking alien and an intergalactic government agent who saves Tsutomu by merging her body with his. Effectively, they become two people in one body, which can shift between the forms of Birdy and Tsutomu…. except Birdy still needs to deal with all the rogue aliens who threaten the safety of the galaxy, while Tsutomu needs to study for his high school entrance exams. From what I’ve been told, the premise is fairly reminiscent of Ultraman and other classic tokusatsu series.

It’s four tight episodes of classic ‘90s OVA goodness, with a fun and slightly silly sci-fi concept that is nonetheless wrung for some surprisingly effective drama at times. The main thrust of it, though, is action comedy — and it definitely delivers on that front. The fight scenes are superbly animated, including some early-career work from now-legendary animator Suzuki Norimitsu, and the character designs by Takahashi Kumiko (Witch Hunter Robin, Snow White with the Red Hair, Cardcaptor Sakura) are amazingly expressive. Birdy’s striking asymmetrical design is a particular favourite of mine. The direction by Kawajiri Yoshiaki (Cyber City Oedo 808, Ninja Scroll, Vampire Hunter D) is solid, and the writing is quite serviceable despite the brevity and premise.

Overall, I wouldn’t say it’s much of an intellectual watch, but if you just want a fun action-comedy ride with an extremely charismatic female protagonist and stunning animation quality, Tetsuwan Birdy is likely to be your jam. I’d recommend it to people who enjoy classic tokusatsu series, the original ‘90s Sailor Moon anime, and the less-depressing parts of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

3. Noir (2001)

This anime series is perhaps not as underappreciated as the others on this list, but I do still feel that not enough people have seen it. It was made by the studio Bee Train, and it’s the first entry in their so-called “Girls with Guns” trilogy (which isn’t actually a coherent trilogy, since they’re three different stories). The series was made right at the end of the cel-anime era, before the transition to digital colouring and compositing, so the masters were shot on film, but it was also made at the beginning of the slow transition to widescreen TV broadcasts, so it’s one of the very rare cel anime that’s in 16:9. This allows for a beautifully detailed look that, IMO, serves to offset the occasionally-limited animation and the frequent re-use of footage.

The premise is basically “secret assassins in France are caught up in weird intrigue and conspiracies”; as such, there’s a lot of very fun gunplay and kickass fight scenes, but also a lot of suspense and mystery. The writing is a little bit slipshod at times, but it ends up holding together, and the characters and (especially) the fantastically moody vibe make the show worth watching.

The characters are imbued with a lot of life and colour, both by their extremely attractive designs and by their voice actors’ wonderful performances. Mireille Bouquet, a young Corsican assassin and one of the two protagonists, is voiced by Mitsuishi Kotono; Yuumura Kirika, the other main protagonist who is a Japanese schoolgirl who has seemingly lost all her memories (but not her exceptional assassin skills), is voiced by Kuwashima Houko; and the mysterious Chloe, who shows up partway through the show, is voiced by Hisakawa Aya. There are definite yuri vibes between Mireille and Kirika, but as with Canaan, it’s all subtextual.

The main draw of the show, though, is its phenomenal soundtrack, courtesy of Kajiura Yuki (.hack//Sign, Kara no Kyoukai, Fate/Zero, Sword Art Online, Demon Slayer) in her very first anime scoring gig. It’s at times propulsive, at times dark and moody, at times beautifully serene, at times melancholy and nostalgic — and it’s utterly memorable.

I would recommend Noir to anyone who likes Canaan, Witch Hunter Robin, Ghost in the Shell, or anyone who just wishes that James Bond were a woman.

4. Flip Flappers (2016)

This anime was produced at Studio 3Hz and directed by Oshiyama Kiyotaka, in a dazzling yet underappreciated directorial debut that was presaged by his impressive animation work on Dennou Coil, Space Dandy, A Letter to Momo, The Secret World of Arietty, and The Wind Rises. Owing to this extremely solid animation background, Oshiyama was able to recruit a lot of prime animation talent for Flip Flappers, and it definitely shows in the stunning sakuga of the wild action sequences that pepper the show’s narrative.

While the fantastic animation is a key draw of this show, the sheer creativity in the worldbuilding, conceptual, and visual design spheres also contribute to its inimitably psychedelic look and feel. The landscapes of the worlds contained in Pure Illusion — the dream-realm that the protagonists enter each episode at the behest of a mysterious scientific organisation — and of the “real” world are whimsical, storybook-like, and slightly “off” in a slightly unsettling but compelling way.

The dreamlike atmosphere pervades the narrative as well — very little about the mechanics of the world is specified out loud, relying heavily on symbolism and visual storytelling to do the heavy lifting for the audience’s understanding. This might be a turn-off for audiences who prefer to have things spelled out for them clearly, but the point of this story is not always to make perfect logical sense, but rather to work on an emotional and metaphorical level. And work, it certainly does.

The episodic structure involving the various worlds of Pure Illusion explores the concept of the Umwelt (the individual sensory “world” of a person or organism), as well as some Jungian concepts and archetypes, in order to express the strange and sometimes-scary developmental stage of adolescence. The characters of Cocona (voiced by Takahashi Minami) and Papika (voiced by Ichimichi Mao) undergo a metaphorical and literal puberty, a coming-of-age similar in some ways to that experienced by the protagonist of FLCL, but with significantly more yuri. In fact, this show has the most outright yuri of any of the anime on this list. But that isn’t very strange for what is essentially a psychedelic magical-girl show: lots of magical-girl anime seem to include homoerotic vibes in some form or another, from Sailor Moon to Nanoha to Madoka.

There are some minor flaws in the storytelling towards the end, IMO, but overall it’s a wonderfully impactful emotional journey to watch Flip Flappers. Plus, the OP and ED are both extraordinarily catchy tunes that I’ve found myself humming on many an occasion.

I’d recommend this anime to anyone who loves weird magical-girl stuff, weird yuri, and/or amazing action animation.

5. Claymore (2007)

An adaptation of the manga by Yagi Norihiro, this anime is considered by many to simply be “basic”, or at least simply “inferior to the manga”. Now. I haven’t read the original Claymore manga (yet! I plan to eventually), but I found this anime to be compelling nonetheless. And if it really is the case that the manga is better, then I definitely look forward to diving in.

Having been produced by Studio Madhouse in the mid-2000s, it’s unsurprising that the vast majority of this anime was outsourced to Korean animation studio DR Movie, a longtime powerhouse subcontractor for both Japanese and American animation alike. That said, the direction of Tanaka Hiroyuki (director of a portion of Hellsing Ultimate and frequent close collaborator of Attack on Titan director Araki Tetsurou) remains sharp, compensating for the sometimes-limited animation with good storyboarding and a strong sense of mood and atmosphere.

Another aspect of Claymore which helps make up for the occasional visual shortcomings is the soundtrack by Takumi Masanori. The compositions are a mix of harder rock and electronic elements with a strong orchestral backbone, as befits a dark-fantasy setting and mood — the faster pieces are edgy and propulsive, very appropriate for the bloody action scenes, and the calmer pieces have a melancholic beauty to them that sticks in one’s memory. I wish the soundtrack were on Spotify, but alas, it is not.

The other sonic element that helps this anime out immensely is its absolutely STACKED voice cast. The main character, Clare, is voiced by Kuwashima Houko, in a fantastic yet understated performance. The other main character, Raki, is voiced by the less-well-known Takagi Motoki, but nearly all the other roles — including many bit parts — are filled with industry legends. Teresa is voiced by Park Romi, Miria is voiced by Inoue Kikuko, Irene is voiced by Takayama Minami, Rubel is voiced by Hirata Hiroaki, Priscilla is voiced by Hisakawa Aya, Ophelia is voiced by Shinohara Emi, and Jean (whom I cannot help but ship with Clare: there’s so much homoerotic tension there!) is voiced by none other than Mitsuishi Kotono. Yes, they got three of the original Sailor Senshi VAs — and I don’t know why that’s funny to me, but it is. And all of the voice actors deliver killer performances.

The premise of the show, before I completely forget to explain it, is that of a dark fantasy world where demons called youma ravage human settlements, with only the titular Claymores to protect humanity. They are a guild of platinum-haired and silver-eyed warrior women who possess superhuman fighting abilities, due to the fact that they’ve been fused with youma essence, and wield the massive broadswords that give them their name. Basically, (s)he who fights monsters must become (partly) a monster to do so.

I’ve heard the vibe of Claymore compared to manga like Berserk, and I don’t know how true that is (not having read the latter for myself), but there’s certainly a lot of bleakness and monstrosity in this fantasy tale. However, the Claymore manga was published in none other than Weekly Shounen Jump, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that the story remains resolutely forward-looking, the protagonists’ arcs focussing on the power of grit, determination, true friendship and loyalty, and protection of the weak and downtrodden. It’s never cynical or sarcastic — always straightforward and sincere despite the frequent darkness of the story.

The writing is consistently solid, even through the controversial anime-original ending (the manga continues long past the point where the anime cut things off), so I’m not sure who to point to for that: Yagi Norihiro for writing the original material, or Kobayashi Yuuko (JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, Attack on Titan s1-3, Kakegurui, Casshern Sins) for adapting it cleanly for the screen? Either way, it made me want to read the manga to experience more of these compelling characters and their travails.

I would recommend this anime to those who enjoy Kill La Kill or RWBY, or just to those who enjoy powerful women hacking at monsters with massive weapons and making lots of blood spray out.

#anime recommendation#anime recs#flip flappers#tetsuwan birdy#birdy the mighty#claymore#noir#noir 2001#canaan#long post#personal#anime

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

youtube

youtube

#anime poll#spyair#bleach#haikyuu!!#haikyuu#gintama#kidou senshi gundam#iron blooded orphans#mobile suit gundam#samurai flamenco

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, I saw a twitter user post about how Witch From Mercury focuses on the implications of the hero gundam unlike past gundam shows and I am obligated to defend my babygirl Iron-Blooded Orphans because this is slanderous.

I also want to preface that I have yet to watch much of any UC series (I’m planning to grind through the Chamuro divorce saga after I graduate with a friend), but I have watched IBO, 00, 08th MS team, and Unicorn among some other movies and series. I have an unpopularly negative opinion of 00 so I don’t feel equipped to analyze any of the implications/themes of the show, but I loved Trailblazer so I’ll probably come back around to it eventually.

ANYWAYS, I fucking love IBO. Not as much as WFM, but it’s absolutely my second favorite series from what I’ve watched so far. Yeah, it’s one of the darker series and it doesn’t have any of the trademark Gundam characteristics about space empathy and the evolution of humanity, but it makes for a wildly interesting mafia/pirate/found family story that targets a BUNCH of my weaknesses. However, it fucking NAILS the overarching theming of the universe and how the Gundams are portrayed and perceived in a very unique way.

The Post Disaster timeline is clearly one of the most unique timelines as it’s literally a post apocalyptic setting after Mobile Armors tried to blow the Solar System up. UC kind of plays with something similar with Operation British/the Colony Drop, but it’s clear that even though half of humanity on Earth died, it’s still a relatively put-together setting. In PD, Mars is completely saturated with war orphans and impoverished people with almost no one wanting to fix the world outside of a naïve teenage hedge fund girl who was literally nicknamed the Princess of Revolution for wanting to play out a fairytale with her as the hero. Even though she succeeds in her objective of gaining Martian economic dependence, at the GREAT cost of Tekkadan mind you, season 2 reveals that despite this, nothing has changed. She succeeded in claiming Martian half-metal for Mars, but it simply enriches a different external entity (Teiwaz in this case) while the poor and homeless continue to suffer. It’s an acute summation of this world where naivety and “hope” will often lead to either net neutral or negative outcomes (insert images of Shino, Mika, Orga, Akihiro, the Dort protesters, and all of the people who died because Kudelia wanted to change the world and Orga wanted to take the shortest path to an easy life for everyone). Regardless of how pure your intentions are, the PD universe will always clap back and fuck either you or the people you’re trying to help over (even Naze and the Turbines suffered this fate).

MOVING on, I bring this up simply to demonstrate how fucked up the setting is and to illustrate why PD Gundams, literally forgotten demons that saved the world from the apocalypse, fit very well in this setting. Barbatos is a perfect encapsulation of this setting. When piloted by the World’s most autistic, driven teenager, it’s capable of unimaginable power, even by the standards of Gundam timelines with drastically higher power scales. This leads to some of the coolest fights ever animated by Sunrise (cradling Barbatos vs Hashmal in my arms like my child) and people turning off their analytical brain to go “ooh big robot” which is a valid way to consume the show. However, the ramifications and effects Barbatos has on the universe is earth-shatteringly important. The extraordinary power Barbatos demonstrates when he and Mika defeat Hashmal awakens something in McGillis that Bael finds worthy, thus leading to Bael;s reemergence which would uproot the entire power structure of Gjallarhorn, the main military power of the system. it also instills a fear in Julietta and Gjallarhorn that these demons are still around and capable of taking squads of Mobile Suits on their own and pushes Iok into bringing the Dansleif (A LITERAL WARCRIME WEAPON) into the field and Causing The Latter Half Of Season 2 to go wrong (oversimplification but I just think it’s funny).

What I’m trying to explain is that the protagonist Gundam of IBO is a potent manifestation of what’s wrong with the PD timeline. To survive, Mika has to sacrifice body parts to let Barbatos off its leash and destroy insurmountable opponents that would be undefeatable without every Dainsleif Gjallarhorn has. It sucks that most people will watch IBO and see really cool mech fights and the Kudelia-Atra-Mika polycule and simply chalk the series up as a mecha shonen because I feel that label does a MASSIVE disservice to the show (I won’t get into it now, but as a poly bisexual, the Mika polycule could have been amazing if any of the writers had met a woman once before this show). Aerial is completely bait for me (they finally made the Gundam A Character) and I love her for how unique and utterly intriguing she is for a Gundam, but Barbatos and even Unicorn and most of the Gundams in 00 are a joy to pick apart and analyze in the context of their respective universes. Just because Aerial has eleven space oomfies in there doesn’t automatically make her any more of an amalgamation and representation of Ad Stella than Barbatos does of Post Disaster or Unicorn of the Late-UC period.

Anyways, watch WFM and IBO.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm thinking about IBO again and I feel like the fact that I knew the ending going into it improved my experience.

Part of the point of the show is that it's a capital-T-Tragedy. Typically the audience engages with a tragedy is by interacting with the foreshadowing and picking out peoples' fatal flaws as it builds.

I'm pretty sure this is why some famous examples like Shakespeare's start by outlining the plot (R&J's Two Households etc. opening to reference a massively famous one.)

In IBO's case, being a tragedy that doesn't do this, an audience going into it without knowing what to expect would need to have enough genre-savviness to pick up on the nature of the show early on to interact with it this way. For better or worse, IBO doesn't hold the audiences hand in the opening the way some stories do.

In particular I think there are three details that were really key to my experience. Two that have to do with what happens in the story itself, and one that has to do with the framing.

I can explain the latter, I think, without revealing anything about the plot, so I'll do so.

Mobile Suit Gundam: Iron Blooded Orphans is better when framed as a four-season show with 13-12 episode seasons than a two-season show with 25 episode seasons, and the viewer should delineate the show based on when the opening and ending credits change.

Short explanation (ha.) is that IBO has two seasons, and they weren't sure they were going to get the second one, which leads to it being somewhat less polished. While season 1 can be taken as a ''whole'' in itself because that's how it was written and the characters are pursing the same goal throughout, season 2 tries to do more than one thing in a way that benefits from mentally cutting it into two to let it shift gears.

Season 1 also conveniently has a nice turning point right in the middle that divides the setup/shit starting to get real that isn't harmed by mentally dropping a border in where the credits change. So taking the whole thing as four instead of two makes it feel better-crafted.

I'll put the other two details under a cut, so that if anyone miraculously sees this before watching it they can make an informed decision as to whether to take my suggestion or not.

The other two details you should know about IBO's ending going into it Sound the alarm Hit the deck here they come:

Being a tragedy, both main characters, Mikazuki and Orga, die before the end of the show.

Kudelia and Atra both raise a child fathered by Mikazuki; this is tied to the theme presented by the ending and communicates something about the setting and the characters.

There you go that's it you're ready go watch the show.

Honestly if anyone manages to watch the thing blind with only the details I gave I'd like to hear an opinion on how they think it affected their experience because I think I'm onto something here.

#Gundam IBO#Gundam IBO spoilers#I'll note that this opinion is taken from having seen IBO *in isolation*#I know there's a video game with side stories but I know nothing about it#so this is a very Death of the Author work stands on its own take#Second I feel like it's important to admit that I had to try to start IBO twice#the Turbines bugged the *hell* out of me the first time until I saw more of what the narrative was doing#so I kind of understand if the superficial anime-fantasy tropeyness of the group is enough of a turn-off to quit the show#because god knows I fucking did the first time

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

and just like that I caught up to Mobile Suit Gundam: The Witch from Mercury.

I don't watch a lot of Gundam but much like Iron-Blooded Orphans, this shit has me in tears each time. Especially when that outro starts playing over the season 2 episodes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyle McCarley will be a Guest at FanimeCon 2023

It has been announced that Kyle McCarley from Mob Psycho 100 will be a guest at FanimeCon 2023.

FanimeCon 2023 is only a few months away and already the guest lists is starting to grow. It has been confirmed that Kyle McCarley will be among the guests. Kyle McCarley is a voice actor best known for his role as Shigeo “Mob” Kageyama on Mob Psycho 100 (Seasons 1 to 2). His other notable roles include Mikazuki Augus in Mobile Suit Gundam: Iron-Blooded Orphans and YoRHa No.9 Type S (aka 9S)…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's fun looking back on that original post now--two months later and having now completed both Iron-Blooded Orphans and The Witch from Mercury. I wanna say, "I didn't know what I was getting myself into," but that'd be a lie. I was expecting to watch a pair of space operas revolving around giant robots fighting with stories that would probably get me emotional. Both shows are generally well regarded so I expected them to be good going in. Suffice it to say they both still managed to exceed my expectations.

I firmly believe that these shows should be watched together. If you watch IBO, move on to WFM--if you watch WFM, go back to IBO. WFM very much feels written with IBO in mind (the similarities between the GUND Format and Alaya Vijnana System being the most obvious example of IBO's influence) and I feel that having the immediate context of one going into the other enhances your experience. WFM is IBO's little sister through and through and watching IBO before it made me appreciate the show (especially its ending) more than I would have otherwise.

If you wanna know which one's my favorite, it's Iron-Blooded Orphans. Largely because I love a good tragedy, but also because it felt more complete than its successor. It's kinda obvious in WFM season 2 that they wanted more episodes than they got and had to cram a lot near the end. I could especially feel this in the last 4-5 episodes. Was it bad? Hell no! But there were a lot of plot threads awkwardly left hanging and some others that were under-cooked or felt contrived (the Space Assembly League are painfully under-cooked). I feel like WFM needed at least one more season to reach its full potential, but what we got was still damn good and had me crying waaaaayyy more than I usually do watching television.

In summary uhhhhh...

Mobile Suit Gundam is really good and words cannot describe what these two kids mean to me.

I'm still letting G-Witch settle in my mind before I move on to the next Gundam show and while I know I should go back to the original and start my UC journey; y'know, to enrich my experience through the AUs and mecha anime as a whole...

There's still one other Gundam show I got unfinished business with...

#I've purchased 7 gunpla in the last 2 months I'm here to stay#mobile suit gundam#iron-blooded orphans#gundam ibo#the witch from mercury#g witch#mobile fighter g gundam#g gundam#gifs#mikazuki augus#suletta mercury#domon kasshu#meta#me rambles

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

IBO reference notes on . . . spacesuits

For reasons that may or may not be related to fanfic, I decided to do a quick survey of the difference spacesuits -- or 'normal suits', in Gundam parlance -- that appear throughout Iron-Blooded Orphans. There's not really much to conclude from this, but it snagged me a set of reference screenshots that I think worth collating for your viewing pleasure.

The most commonly used normal suit first appears during the battle between Tekkadan and the Turbines, where Atra helps Kudelia out with putting one on, in a scene that provides some gratuitous shots of the girls changing. It's not especially tasteless, in the grand scheme of things, but it's one of those genre trappings that didn't really need to be there. Still, it provides a good demonstration of how the suits fit together, where the zippers and fastenings are, and so on. Plus the hilarious visual of the helmets being repurposed as potato buckets.

This normal suit is clearly a standard type, that turns up in multiple civilian and non-official military settings. Most immediately, we see that the Turbines use it, the orange swapped for a fetching maroon.

Generally speaking, the colour-blocking is the only thing to change between uses. Here are a couple more shots showing the Tekkadan and Turbines versions, including a close-up on the boots.

Beyond these two types, the most usual variant is a black and grey version that appears in various scenarios, including in the flashbacks to Akihiro's family, the Dort colonies, and the archaeologists in Urdr Hunt.

Curiously, Katya also wears this towards the end of Urdr Hunt -- where she must have been given it by Gjallarhorn. So can we take the black, grey and white to be a sort of universal default?

Other colour variants are worn by young!Amida and by Range (under his poncho) in Urdr Hunt, and by the various groups of mercenaries and space-pirates in Season 2.

Speaking of pirates, the ones who attacked Akihiro's family have added a jetpack for easy manoeuvring in zero-g. It's notable that this isn't something we see more generally: Mikazuki has to rely on a hand-held thruster in the Dorts. This, however, harkens back more to the original Gundam series in terms of moving around in space.

Moving on to the second major 'civilian' normal suit, the human debris all wear a slightly simpler, slightly more badly-fitted white version striped in red. We first see this with the Brewers and later with human debris used by the JPT Trust (not shown because it's mainly seen in fairly bloody scenes).

A palette-swap of this is used by 598 and his crew in Urdr Hunt, which I bring up as an excuse to post the bisexual-energy screenshot.

Due to image limits, I won't cover Tekkadan's pilot suit in this post. If you've seen the show, you'll have seen a lot of that, and of Gjallarhorn's equivalent. What I find interesting about the human debris normal suit is that it is clearly more closely related to the general-purpose version than what Shino is wearing here, which is a specialised for an Alaya-Vijnana-user in a military setting.

This of course makes sense given that everything about the human debris is meant to invoke cheapness. Rather than a custom-made battle suit, they just get a standard one-size-fits-nobody get-up with an A-V adaptor stuck on the back. It's a nice visual touch, that also helps emphasise the sense of human debris as little kids forced into situations they shouldn't be in. That being said, the *helmet* is distinctly made for a mobile suit pilot, being something close to what Gjallarhorn soldiers wear.

Tekkadan does use another distinct normal suit variant, with added armour, that shows up for the battle with the Brewers and never again. Or, well, I am not actually sure if this is meant to be a normal suit or more akin to the combat armour we see Gjallarhorn infantry wearing, or if that is a distinction without a difference. Since they are both deployed in space-based operations, we can probably assume they're at least potentially interchangeable with normal suits.

These do notably lack the backpack of the standard normal suit. which I take to be where the life-support gubbins goes. However that goes for the pilot suit as well (it only has the A-V adaptor block; I assume everything else is distributed at the waist and collar) and we see it functioning fine for spacewalks. So I'm grouping this in here as well.

As I said up the top of the post, there's not a whole lot to take away from this, beyond the different ways the same asset is reused throughout the series. It's a neat enough design, although the pilot suits are far more striking. I do like the pirates' jetpack; wish we'd seen more of that (that's actually what I was looking up when I started collecting these).

Overall, I quite like the commonality of design, the sense that someone somewhere is just mass producing these things as a standard piece of kit. That's kind of what you'd need, in a space-faring society, to make these widely available to as many people as possible, just as a matter of basic practicality. Then you'd have different groups that could afford it customising to fit their organisations.

Huh. That must mean the human debris normal suits are also mass produced, if there's a standard-issue version of those.

There we go again with another demonstration of the base-level exploitative awfulness built into this setting.

[Index of other writing]

#gundam iron blooded orphans#gundam ibo#g tekketsu#tekketsu no orphans#reference#notes#normal suits#spacesuits#design

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

For anyone confused by this video (spoilers for Mobile Suit Gundam: Iron-Blooded Orphans):

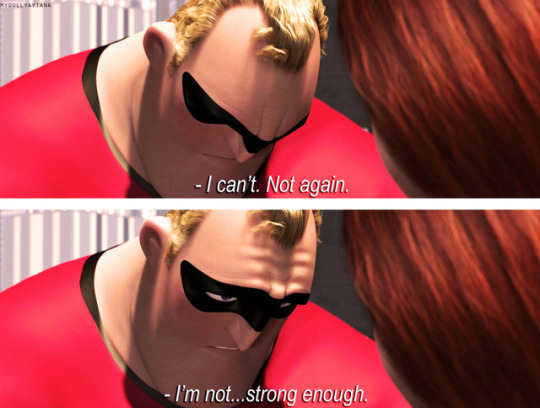

The main TV Gundam anime that preceded The Witch from Mercury was Iron-Blooded Orphans, released 7 years before, and is notable, among other things, for a bleak Season 2 with an unusually high amount of major character deaths (for Gundam anyway), which was off-putting for some fans.

In particular, the death of Orga Itsuka (the man threatening Miorine in the video above), which was intended as emotional and tragic, was instead seen by many Japanese fans as melodramatic and over-the-top, which resulted in a Gundam fandom phenomenon known as 'Orga-posting', which involves creating videos where Orga is spliced in and gets killed in absurd contexts (another example of Orga-posting I've seen involved him being gunned down by Ryou Yamada from Bocchi the Rock!, for instance).

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

To give a more full recommendation: