#Magna Graecia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A lion attacks a stag. Reverse of a silver didrachm issued by the polis of Elea in southern Italy between 420 and 380 BCE. The obverse, not shown, bears the head of Athena. Now in the Staatliche Münzsammlung, Munich, Germany. Photo credit: ArchaiOptix/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Magna Graecia#Classical Greece#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Classical Greek art#coins#ancient coins#Greek coins#Ancient Greek coins#didrachm#numismatics#ancient numismatics#Staatliche Münzsammlung#animal violence tw

801 notes

·

View notes

Text

hades and persephone enthroned | c. 600 - 550 BCE | lokroí epizephúrioi, magna graecia (modern-day locri, italy)

in the museo archeologico nazionale di napoli collection

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Villa Exomandria, Monastiria, Antiparos, Greece,

Courtesy: Aristidis Dallas Architecture

#art#design#architecture#minimalism#luxury#interior#interiors#luxury house#luxury home#summer#summer house#greece#villa#exomandria#monastiria#antiparos#island#island house#magna graecia#aristidis dallas

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calabrian Greeks: Pocket of Hellenism in Southern Italy has Survived Millennia

There exists today a tiny enclave of Calabrian Greeks, Greek-speaking people in the Aspromonte Mountain region of Calabria that seem to have survived millennia…perhaps since the Ancient Greeks began colonizing Southern Italy in the 8th and 7th Centuries BC.

Italian as we know it today was not always spoken throughout Italy. The Italian language did not become the staple language until well into the end of the 19th Century during the process of Italian unification, or the Risorgimento.

Until then, the Italian peninsula was made up of Italo-Romance dialects and smaller minority languages that were differentiated by region and historical influences.

Once unification was complete, the Tuscan dialect was ushered into power as the official language of the Italian nation. This became the beginning of the modern end of the Greek language in Calabria, or what it is known today as Greko.

There exists today a tiny enclave of Greek-speaking people in the Aspromonte Mountain region of Calabria that seem to have survived millennia…perhaps since the Ancient Greeks began colonizing Southern Italy in the 8th and 7th Centuries BC.

Their language is called Greko. They survived empires, invasions, ecclesial schisms, dictators, nationalistic-inspired assimilation, and much more. Greko is a variety of the Greek language that has been separated from the rest of the Hellenic world for many centuries.

To help bring more perspective, Greek was the dominant language and ethnic element all throughout what we know today as Calabria, Basilicata, Puglia, and Eastern Sicily until the 14th Century.

Since then, the spread of Italo-Romance languages, along with geographical isolation from other Greek-speaking regions in Italy, caused the language to evolve on its own in Calabria. This resulted in a separate and unique variety of Greek that is different from what is spoken today in Puglia.

History of Calabrian Greeks

There are many theories or schools of thought regarding the origin of the Greko community in Calabria. Are they descendants of the Ancient Greeks who colonized Southern Italy? Are they remnants of the Byzantine presence in Southern Italy? Did their ancestors come in the 15th to 16th centuries from the Greek communities in the Aegean fleeing Ottoman invasion?

The best answers to all of those questions are yes, yes, and yes. This means that history has shown a continuous Greek presence in Calabria since antiquity. Even though different empires, governments, and invasions occurred in the region, the Greek language and identity seemed to have never ceased. Once the glorious days of Magna Graecia were over, there is evidence that shows that Greek continued to be spoken in Southern Italy during the Roman Empire.

Once the Roman Empire split into East (Byzantine) and West, Calabria saw Byzantine rule begin in the 5th Century. This lasted well into the 11th Century and reinforced the Greek language and identity in the region, as well as an affinity to Eastern Christianity.

What’s even more fascinating is that Calabria was apparently a Byzantine monastic hub of sorts. There were over 1,500 Byzantine monasteries in Calabria and people today still remember and adore those saints. Even though Byzantine rule ended in Calabria in the 11th Century, the Greek language continued to be spoken while gradually declining in the region with the spread of Latin and a process of Catholicization.

Follow us on Instagram, @calabria_mediterranea

#calabria#italy#italia#south italy#southern italy#greek#greek language#greek langblr#griko#mediterranean#greeks#magna graecia#minority languages#langblr#bova#gallicianò#bovesia#byzantine#byzantine empire#italian#history

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

A GREEK BRONZE GRIFFIN-CRESTED CHALCIDIAN HELMET MAGNA GRAECIA, HELLENISTIC PERIOD, CIRCA 300-200 B.C.

#A GREEK BRONZE GRIFFIN-CRESTED CHALCIDIAN HELMET#MAGNA GRAECIA#HELLENISTIC PERIOD#CIRCA 300-200 B.C.#bronze#bronze helmet#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#ancient greece#greek history

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sword of Damocles by Richard Westall

#damocles#sword#art#richard westall#neoclassicism#neoclassical#dionysius i#dionysius#king#courtier#power#peril#fear#allusion#sicily#syracuse#magna graecia#ancient greece#ancient greek#cicero#maidens#swords#horsehair#court#dionysius i of syracuse#mediterranean#classical antiquity#timaeus of tauromenium#europe#european

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

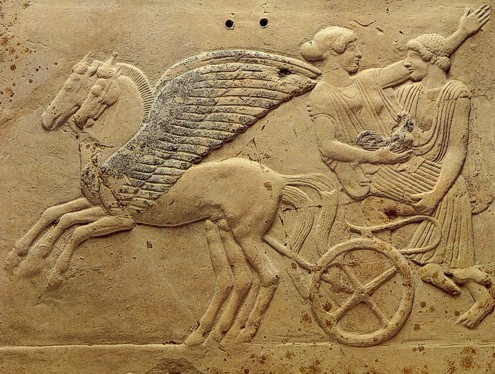

Ancient clothing

Magna Graecia

British Museum

London, July 2022

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

my favorite place ❤❤❤

#and imo one of the most beautiful places on earth#archaeological park of paestum#paestum#temple of hera#temple of athena#magna graecia#archaeology

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ricardo Bofill - Taller de Arquitectura, Les Arcades du Lac, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France, 1982 ph. Laurent Kronental VS Federico Cortese, Ruderi d'un mondo che fu | Vestiges of a world that once was, 1891

#Federico Cortese#ruin#ruins#paestum#magna graecia#Ricardo Bofill#taller de Arquitectura#les arcades du lac#france#Laurent Kronental#paint#painting#vestiges

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ruins of the Temple of Apollo, 6th century BCE.

Syracuse, Sicily

Feb. 2024

#syracuse#siracusa#italy#italia#architettura#sicily#sicilia#ancient greek#ancient architecture#Magna Graecia#travel#original photography#photographers on tumblr#photography#lensblr#architecture#urbanexploration#urban exploration#temple#ruins#wanderingjana

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

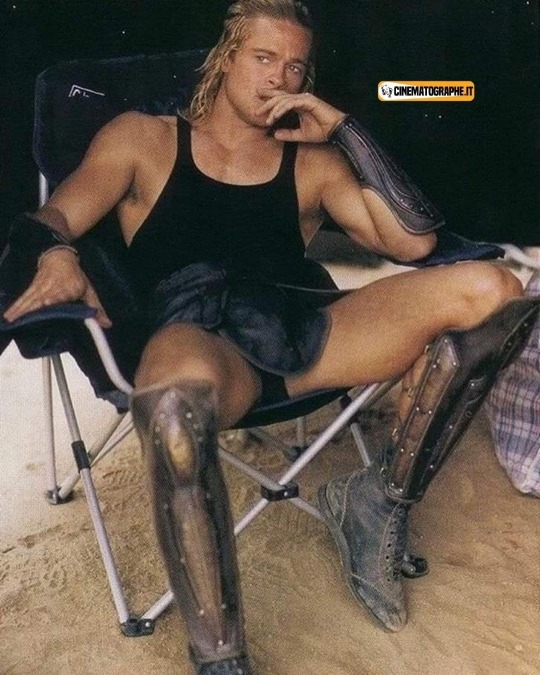

Brad Pitt in Troy (2004)

#helen of troy#hector of troy#actorslife#actors icons#brad pitt#angelina jolie#film#historical#history#historical film#grecia#magna graecia#mitologia grega#greco#greece#histoire#film photography#filmedit#90s actors#beautiful actors

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coin minted from electrum (a naturally occurring gold-silver alloy) by the Sicilian polis of Syracuse between ca. 310 and 305 BCE, when it was under the sway of the expansionist tyrant Agathocles. On the obverse, the head of Apollo, shown with his characteristic long hair; on the reverse, the Delphic tripod, atop which the Pythia sat when delivering oracles. Photo credit: CGB Numismatique Paris.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Magna Graecia#Sicily#Ancient Sicily#Hellenistic period#ancient history#Greek religion#Ancient Greek religion#Hellenic polytheism#Apollo#God Apollo#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Hellenistic art#Sicilian art#coins#ancient coins#electrum#Greek coins#Ancient Greek coins#numismatics#ancient numismatics

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

bronze water jug decorated with the head of a gorgon | c. early 5th century BCE | lokroí epizephúrioi, magna graecia (modern-day locri, italy)

in the museo archeologico nazionale di napoli collection

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Between 520 and 500 BC, the artisans of Magna Graecia left us a unique masterpiece: the Antefix of Hera.

This extraordinary find, used to decorate the roofs of temples, is much more than an architectural element. It represents a journey through time, between fashion, art and ancient symbols.

The female figure depicted wears a tight blouse, an unusual garment for the time, decorated with geometric patterns with squares and black swastikas.

The swastika, today linked to a dramatic story, actually has much older origins and a completely different meaning.

Derived from the Sanskrit "svastika", it was a symbol of well-being, luck and prosperity, used in many cultures of the ancient world.

This masterpiece not only testifies to the artistic refinement of Greek artisans, but invites us to reflect on the evolution of symbols over time.

What remains of their original meanings?

How do they change, adapting to different cultural and historical contexts?

The Antefix of Hera is a window onto the past, an example of how ancient art can still speak to modern man today, revealing not only aesthetics, but also cultural and symbolic complexity.

#symbolism#wisdom#greece#greek#antefix#symbolic#ancient history#ancient greece#svastika#sanskrit#art#magna graecia#greeks do it better#true history

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Locri, Calabria, Italy

Locri Epizefiri (Greek Λοκροί Ἐπιζεφύριοι; from the plural of Λοκρός, Lokros, "a Locrian" and ἐπί epi, "on", Ζέφυρος (Zephyros), West Wind, thus "The Western Locrians") was founded about 680 BC on the Italian shore of the Ionian Sea, near modern Capo Zefirio, in Southern Italy's Calabria, by the Locrians, apparently by Opuntii (East Locrians) from the city of Opus, but including Ozolae (West Locrians) and Lacedaemonians.

Due to fierce winds at an original settlement, the settlers moved to the present site. After a century, a defensive wall was built. Outside the city there are several necropoleis, some of which are very large.

Locris was the site of two great sanctuaries, that of Persephone and of Aphrodite. Perhaps uniquely, Persephone was worshiped as protector of marriage and childbirth, a role usually assumed by Hera, and Diodorus Siculus knew the temple there as the most illustrious in Italy.

In the early centuries Locris was allied with Sparta, and later with Syracuse. It founded two colonies of its own, Hipponion and Medma.

During the 5th century BC, votive pinakes in terracotta were often dedicated as offerings to the goddess, made in series and painted with bright colors, animated by scenes connected to the myth of Persephone. Many of these pinakes are now on display in the National Museum of Magna Græcia in Reggio Calabria. Locrian pinakes represent one of the most significant categories of objects from Magna Graecia, both as documents of religious practice and as works of art. In the iconography of votive plaques at Locri, her abduction and marriage to Hades served as an emblem of the marital state, children at Locri were dedicated to Persephone, and maidens about to be wed brought their peplos to be blessed.

During the Pyrrhic Wars (280-275 BC) fought between Pyrrhus of Epirus and Rome, Locris accepted a Roman garrison and fought against the Epirote king. However, the city changed sides numerous times during the war. Bronze tablets from the treasury of its Olympeum, a temple to Zeus, record payments to a 'king', generally thought to be Pyrrhus. Despite this, Pyrrhus plundered the temple of Persephone at Locris before his return to Epirus, an event which would live on in the memory of the Greeks of Italy. At the end of the war, perhaps to allay fears about its loyalty, Locris minted coins depicting a seated Rome being crowned by 'Pistis', a goddess personifying good faith and loyalty, and returned to the Roman fold.

The city was abandoned in the 5th century AD. The town was finally destroyed by the Saracens in 915. The survivors fled inland about 10 kilometres (6 mi) to the town Gerace on the slopes of the Aspromonte.

Today, the modern town of Locri boasts a National Museum and an Archaeological Park, etirely dedicated to the ancient Greek city. The museum preserves the most important findings of the time, such as vases, pinakes, tools used in everyday life, architectural remains from the various excavation area.

Follow us on Instagram, @calabria_mediterranea

#locri#calabria#italy#italia#south italy#southern italy#mediterranean#mediterranean sea#magna graecia#magna grecia#archaeology#archeology#ancient#art#ancient art#history#ancient history#greek#greek art#ancient greece#landscape#italian#italian landscape#landscapes#europe#persephone#olive trees#olive tree#nature#nature photography

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

A GREEK BRONZE APULO-CORINTHIAN HELMET MAGNA GRAECIA, LATE ARCHAIC TO EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD, CIRCA 525-475 B.C.

The Apulo-Corinthian helmet type, also called Pseudo-Corinthian, was worn cap-like on top of the head, rather than enclosing the head in the manner of the earlier Corinthian predecessor. The cheek-pieces of this new variant no longer serve their original purpose, as they now angle forward to function as a visor. The form of the nose-guard, eye-openings and gap between the cheek-pieces are now purely decorative. This example features embossed brows above the eye-openings. At the back is a flaring neck-guard, and at the sides, perforations to secure a chin strap. The helmet is surmounted by a tall, forked plume-holder above a twisted stem. The surface is lavishly engraved with addorsed horses above the neck-guard, a boar on the proper-left cheek-guard and a floral motif on either side above the perforations.

#A GREEK BRONZE APULO-CORINTHIAN HELMET#MAGNA GRAECIA#LATE ARCHAIC TO EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD#CIRCA 525-475 B.C.#bronze#bronze helmet#greek helmet#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history

33 notes

·

View notes