#Macedonian Court

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Whenever we think of royal families our minds tend to go to the concept of the European noble House. The House of Habsburg, the House of Windsor, the House of Stuart etc. I understand that we should look at the Ancient Greek, Macedonian & Hellenistic royal families in a different way becuase of the different family & power dynamics - could you please help us understand the difference?

Ancient Court Societies vs. Modern

Probably the biggest difference is greater organization of hierarchy. Modern royal houses have had a lot of time to evolve.

Norbert Elias’s The Court Society has become the foundational study on court systems, although it’s western-focused by intent. Nonetheless, it’s a useful introduction to how courts function with inner courts, outer courts, etc.

The biggest things to keep in mind are:

The degree of formality between court members. How “deep” and structured is the hierarchy? (Smaller courts typically have far less formality than larger ones.)

How formalized are matters of succession and marriage ties? Particularly the presence (or absence) of royal polygamy can affect that.

Court societies inevitably progress from less formal and hierarchical to more of both. We can sometimes talk about earlier court societies as chieftain-level societies versus more organized royal, or even imperial societies.

Part of the struggle first Philip, then Alexander faced was transforming a chieftain-level court system into something that would work on a (much, for Alexander) larger scale. Unsurprisingly, there was push-back against, essentially, “bureaucracy.” Nobody likes it, but the larger an area controlled, the more necessary it becomes.

Traditional Macedonian courts were fairly informal, the king being primo inter pares (first among equals). No titles were used when addressing him—he was called by his name—and the only thing expected of the speaker was to take off his hat. “King” (basileus) was used when speaking OF him. We don’t see “King ___” employed in Macedonia (at least in inscriptions) until Kassandros, who needed it to buck up his claim.

None of that means the average person could wander into the palace and start chatting up the king. He was protected by his Bodyguards (Somatophylakes), who also apparently managed access to him. Yet he was expected to sit in judgement as an appellate court, where anybody could appeal a case before him. How often this occurred no doubt depended. Philip was gone a lot, and Alexander was permanently out of Macedonia two years into his reign. Presumably his regent fulfilled the role in his absence. (As I depicted near the beginning of book 2, Rise, when Alexandros is hearing cases.) Anyway, that’s one place the “average person” could get the ear of the king. Also, it seems that he was more approachable by soldiers in battle circumstances. We’re told Alexander got right in with his men to do work during sieges. It was to encourage them, but he was standing next to them so they could see and talk to him, if they wanted to. He seems to have known many of his veterans by name.

Another factor in Macedonia was lack of formal hierarchy among nobility. They had a nobility—the Hetairoi (King’s Companions)—but theoretically all Hetairoi were equal in status. In practice, they absolutely weren’t. The king also had an inner circle referred to as “Friends” (Philoi), who acted as chief advisors. The problem with both terms is their use as common nouns as well as special titles. When is a friend a Friend?

Also, at least some of this was hereditary. Yes, making (or removing) Hetairoi was in the power of the king. But it was much easier to do the former than the latter, and even strong kings didn’t do the former early in their careers, never mind the latter. For many, becoming Hetairos was a rubber-stamp. They were Hetairoi because their fathers had been. We’re also not sure if the title was extended only to the eldest male in a household, or more than one could hold it at once, but for most, it was a birthright.

So, when Alexander took the throne, he was stuck with his father’s Somatophylakes (Bodyguard) and inner circle of advisors. He absolutely could not toss them out on their ear to install his own men. He had to proceed sloooowly. Which is why we don’t see Hephaistion as a Somatophylax even by the Philotas Affair, five years into ATG’s reign. He was clearly an advisor (Philos), but didn’t become Bodyguard until sometime later. Same thing with Ptolemy, who apparently got Demetrios’s slot—the Bodyguard (almost surely one of Philip’s) behind the actual conspiracy of Dimnos, not the made up one of Philotas. When he was executed, Alexander promoted Ptolemy to his slot. Note that Ptolemy was made Somatophylax before Hephaistion. Politics, family status, and probably age trumped personal affection.

If Hetairoi couldn’t be kings themselves (unless they were also Argeads), they were king makers, and kings had to take their influence into account. Especially new kings.

As a chieftain level society, Macedonia operated on “rule by clan” with the king being the senior male Argead. His brothers, sons, nephews, and male cousins might all have important roles, as did the women, although theirs were primarily religious and the running of the royal household. Yet royal women could do limited politicking in the way of donations (eurgetisms) to create goodwill, promote the family, or make alliances—as well as (of course) the alliance created by their marriage itself. Most of these roles were informal and ad hoc, rather than titular, if also expected of them. For instance, the king’s wives were just that: king’s wives. The title queen (basileia) wasn’t used until the Hellenistic courts of the Diadochi.

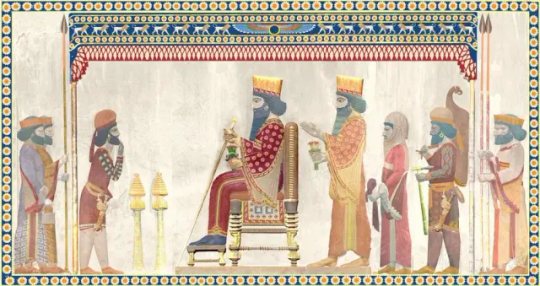

Ancient near eastern courts were more stratified, with more distinct roles. In fact, it seems that Macedon, from Alexander I onward, borrowed offices from the Achaemenid Persian court, including the Bodyguard and the Royal Pages (King’s Boys). So as early as the late Archaic Age, Macedonia looked east for how to formalize a court. Certainly Philip did it well before Alexander. The notion that Alexander’s Persianizing was somehow new is bull malarky.

Anyway, in the ANE, kings tended to fit one of two traditions: shepherd king or heroic king. The Sumerian kings and Hammurabi (Old Babylon) were both examples of the shepherd-king model. Heroic kings began with the Akkadian, Sargon the Great, then the neo-Assyrian kings, especially the Sargonids. Cyrus cast himself as a heroic king, but we see a shift back to shepherd kings with Darius the Great. Another aspect of ANE kingship were three chief expectations: win wars, build big shit, and administer justice.

Due to a much longer tradition of kingship extending from the Early Bronze Age, as you may imagine, these court systems developed much more in the way of formalized structures and offices. If these changed from king to king, at least by Bronze-Age Babylon (Hammurabi), then Neo-Assyria, access to the king was severely curtailed. At least the Persian kings got out and moved around on a sort of “King’s Progress,” but that was to check up on satraps. The average citizen saw them only at a distance. In contrast the Sargonids of neo-Assyria emerged from their palace complexes almost exclusively when going to war.

The Medes and Persians, like the Hittites before them, fit themselves into ANE traditions after they arrived in the area. Less is known about pre-ANE Hittites, but if they kept some unique religious traditions, when it came to How to Run an Empire, they used Akkadian and Egyptian precursors. Similarly, the Medes and Persians who came from the steppes, also adopted ANE patterns while retaining some traditions—again particularly religious (Zoroastrianism). We know a wee bit more about them prior; they (like Macedon) seem to have had chieftain-level monarchy with rule by clan, plus tribal princes, before conquering the whole area.

I hope that helps in understanding ancient eastern Mediterranean and near eastern notions of a court. We know less about the Odrysian Thracian and Illyrian kings to Macedonia’s north, but I suspect they were similar to early Macedon. Just tooling around Thrace, it was very clear to me that we’re looking at a shared regional culture between that area and Macedonia. Similar vibes attended my visit to Aiani (ancient Elimeia) and Dodonna (Epiros). I didn’t get up into Illyria, but what I do know of the archaeology suggests the same. ALL these cultures, despite the ethnic and linguistic differences, influenced each other. Yes, ancient Macedonia was at least “Greek-ish,” but we can’t and shouldn’t dismiss the impact on them from their northern neighbors.

Last, let’s consider the role of royal polygamy. Well back into the Bronze Age, ANE kings might marry several wives and also kept concubines for political purposes. That’s why we call it royal polygamy, not just polygamy. Royal polygamy might exist in a society that otherwise limits the number of wives anyone not the king can have.

Macedonian kings also practiced it, and Thracian and Illyrian, but on a more limited scale. Greeks and Romans, then Christians, depicted any polygamy as a “barbaric Oriental” (= morally corrupt) practice that supported their general view of Asia as soft and indulgent. (Sex itself wasn’t a vice, but too much sex was: uncontrolled desire.)

In later Europe, kings might have mistresses, but it wasn’t “official,” and they certainly didn’t have multiple wives. Christianity frowned on that. Even before, Roman emperors didn’t employ royal polygamy, although they did use serial monogamy—a long-standing practice back into the Roman Republic. Yet that required divorce. When the Christian church made marriage both a sacrament and a vow (not a contract, as it had been pretty much everywhere else), they made divorce impossible without either a wife’s death or religious shell games like annulment. Until Henry VIII, European kings were largely stuck with just one marriage.

Ancient courts didn’t have that problem. And from a political point of view, monogamy is a problem. It reduces the number of political ties available. Having royal polygamy offers more fluidity in possible heirs, and increases, sometimes exponentially, avenues for political alliance.

That said, the downside can be messy inheritance. Two of the more infamous inheritance disputes (other than Alexander’s) involved Esarhaddon, youngest son of Sennacherib, and Cyrus the Younger vs. Artaxerxes II. The latter dispute resulted in civil war (thank you, Xenophon, for telling us about it). As for Esarhaddon, he was so in danger from his older brothers, his mother kept him out of the capital until claimants were dead. There are others, but these two leapt to mind. There are also Egyptian examples, but I’m far less knowledgeable about those dynasties. And, as we see later in Europe, disputed successions can occur without polygamy!

Anyway, when it comes to selection of the heir, two things that matter in polygamous courts: status of the mother, and (for the ANE) whether she was queen. Not all wives were also queens. In the case of Esarhaddon, his mother Naqiʾa was of lower status and not a queen, so when his father named him heir, his older brothers (and their court allies) blew a gasket. Both Assyrians and later Achaemenid Persian kings could marry as many women as they wanted, plus take concubines…but the heir was expected to be from his Chief Wife, or Queen. Of “pure” blood. Cyrus the Younger’s argument against his older brother rested on a similar status technicality: he’d been born after his father became king, while Artaxerxes II was born before. We’d say Cyrus was “born to the purple.” But it was just an excuse; he was the ambitious one, and their mother favored him. If Macedonia didn’t have queens, the status of the mother mattered to being selected as heir there as well.

So these are some of the chief differences between ancient Mediterranean and near eastern courts, compared to later European.

#asks#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedon#ancient Persia#ancient Assyria#ancient Babylon#court societies#ancient court societies#Macedonian court#Philip II#kingship in the ancient near east#kingship in Macedon#Classics#tagamemnon

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amazingly -and oh so not surprising-the way people conduct their selves and talk about Cleopatra's physical appearance still piss me off.

#cleopatra#yea she was greek Macedonian and nit nubian but you know what?#there was a movie abt egyptian Gods played by Gerlad Butler I think you dont have to be so picky about this smh#history#herstory#ancients#cricket chirps#I want tp watch her play mental chess with Ceasar and her court and hang out with her kids and waych her study 9 languages ect

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ive been reading the Persian Boy and I'm not suprised by the orientalism but I am disappointed

#Cipher talk#Tbc I don't mean the depiction of slavery#It's very specifically the depiction of Greek culture- I've gotten to the scene where Baogas has spears thrown at him by the 'squires'- as#Subtly 'better' than Persian culture#There's a scrap of deniability bc it's from Baogas's POV so he thinks the Greeks and Macedonians are completely weird and immodest#But what really gets me is how it portrays Alexander as outraged by the treatment of Greeks held in slavery and how it's all 'oh in Greece#They Never cut a boy' and there's no mention that Athenian 'democracy' had a large class of slaves as of yet#But even as we're told by the narrator how improper and immodest the Greeks and Macedonians are I can feel the author winking and nudging#Like 'oh look at how the Persian court is weighed down by ceremony its barely a real army they're decadent (in the way a conservative says#That about a culture) and look at how Baogas holds rivers as sacred and doesn't swim in them (you know the same water he gets sick from)#And the hypocrisy that he was groomed as a 'courtesan' as a literal child but is embarrassed by nudity'#Yeah Mary I can see the feelings of cultural superiority. I still remember that Athens was misogynistic as fuck and had plenty of issues

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Derveni Krater, a masterpiece of ancient metalwork. Found in Derveni, near Thessaloniki, in 1965. The funerary inscription on the krater writes it's dedicated to Astiouneios, son of Anaxagoras, from Larissa, an aristocrat. Some believe that this elaborate artefact was made in Athens while others suppose that it could be created in the Macedonian court, the date of its creation isn't clear as well, generally categorised as Hellenistic. What is most important though is the krater's vivid, playful and sensual decoration with satyrs, maenads and the pair of Dionysus and Ariadne. Usually, when someone died unmarried and the family had the means, such a depiction of a happy mated afterlife was preferred so to comfort the relatives for their loss. The relationship depicted between Dionysus and Ariadne seems more than sensual, the transparency of her clothing, along with his nakedness and their stances are more than revealing of their common passion.

Now at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece. The Derveni Krater may seem gold but it's actually made of bronze.

#mythology#art#symbolism#ancient greece#greek gods#ancient art#dionysus#ariadne#greek museums#antiquity#derveni krater#masterpiece#hieros gamos#satyrs#maenads#sensuality#ancient greek religion

630 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persians

❝commission: another one shot that explores y/n's life as a captive (and pregnant!) Queen in Babylon. I'd ideally like it to include some sort of interaction with one or more of the Persians (ie Bessus, Darius, Bagoas) but I'm fine with you taking creative liberties so long as we get to see what's y/n's been up to before Alexander gets to Babylon. — requested by 💻 anon.

❝ 📜 — lady l: It's been a while since I wrote something like this but I'm happy with the result! I hope you like it and forgive me for any mistakes. Another story for the TLQ universe! ❤️

❝tw: slight threat.

❝word count: 2,921.

Life in Babylon was not what you had expected when you were taken captive, but surprisingly, it was kind to you. Although technically you were a prisoner, the reality was far from what one would imagine for someone in that role. There were no shackles, only silken veils. There was no scarcity, only abundance. What should have been a prison had become a kind of gilded exile, where you enjoyed comforts that had previously seemed unattainable.

Your freedom had its limits, of course. You could wander through the bustling markets and lush gardens of Babylon, but always under the watchful eye of the guards that Darius had assigned to follow your every step. They were not hostile, just firm, as if they were more protectors than jailers. This was a direct order from the Persian king himself, and no one dared to defy it. After all, disobeying Darius was a risk that few were willing to take.

It was impossible to ignore the speculation that such kindness generated. Perhaps it was a political gesture, a reflection of the warmth Alexander had shown the Persian king's family after his conquests. Or perhaps Darius was trying to ensure his own safety in the event that Babylon fell to Macedonian rule. But in the end, these were not your concerns. What mattered was that you were treated as someone of great importance, and that in itself was a relief amid the uncertainty.

The luxuries that now filled your life were unimaginable in the days when you traveled with the Macedonians. Here, resources seemed endless. Fine clothes, rare perfumes, and exotic dishes were part of your routine. You were attended to by devoted servants and received a treatment that only extended to the highest members of the court. There was no doubt about it: you were revered as a queen.

And Queen you were, even on the enemy side. This title was not just a formality; it carried with it a weight that not even the Persians dared to ignore. The respect shown to you went beyond any political or military rivalry. You were someone whose position transcended borders and conflicts, and this ensured that, at least for the time being, your stay in Babylon would be comfortable, almost pleasant.

You sat on the balcony of your room, savoring fresh fruit that had been served on an ornate silver plate. The warm breeze carried the distant scent of dry earth, but the now cloudy sky suggested that the long-awaited rain was about to fall. It was rare for it to rain during the scorching months of the Babylonian summer, and many in the city considered it a bad omen.

For you, however, the rain was a welcome relief. Ever since you were a child, you had loved the sound of the drops hitting the ground, the coolness it brought to the air, the unique scent that emanated from the wet earth. It was a comfort that seemed almost familiar to you, a distant memory of simpler times.

As you admired the heavy clouds dancing in the sky, a soft voice broke the silence.

"Would Your Majesty like anything else?"

You turned quickly, an instinctive reflex that betrayed your constant tension. However, the stiffness in your shoulders disappeared when your eyes met the face of Bagoas, the Persian eunuch who was your servant — or slave, as the court preferred to call him.

Bagoas was a gift from Darius, given to you shortly after your arrival in Babylon. While many saw him as mere property, you couldn’t accept that idea. To you, he was more than an object or an obligation; he was a human being with his own pains and stories.

Yet the reality of his situation was inescapable. Freeing him was a desire that burned in your heart, but for now, it remained beyond your reach. There was no way to give him the freedom he deserved. You didn’t have the resources or the power to do so now.

Even so, you treated him with all the dignity you could offer. You tried to ease the burden of his condition whenever possible. It was a small gesture, perhaps insignificant to some, but to you, it was important.

As Bagoas stood before you, politely waiting for your response, you made a mental note: when this was all over, when Alexander captured Babylon — and you believed he would — you would free Bagoas. More than that, you would reward him for his service by ensuring that he had a dignified and comfortable life.

It was a dream, perhaps a little naive, but it was something you held on to firmly. Because, in the midst of all the uncertainty and chaos, believing that you could do something good for someone else was what gave you the strength to carry on.

"No, thank you, Bagoas. I’m fine." You replied with a slight smile, trying to convey reassurance.

The eunuch simply bowed his head in a respectful gesture and began to leave, but you called out to him before he could take the first step.

"Bagoas, wait."

He stopped immediately, his deep brown eyes meeting yours. There was something about the intensity of his gaze that always made you slightly uncomfortable, as if he saw more than you cared to reveal. You adjusted yourself on the cot, crossing your legs in an effort to appear more at ease.

"Are you hungry?" You asked, pointing to the fruit platter beside you. The plate was piled high with fresh, sweet delicacies, a true luxury in times like these, accompanied by a glass of wine that remained untouched. "I’m not very hungry, and it would be a waste to leave this out."

There was a good reason why the wine remained untouched. You were pregnant. Although at that time wine was often considered safer than water, you didn’t want to take any chances. It was a simple precaution, but one that you insisted on maintaining. It might still be early in the pregnancy, but you were already attached to the life growing inside you.

Bagoas tilted his head slightly, which seemed to be a gesture of surprise, before murmuring with his usual softness:

"That’s very kind, but I’m not hungry."

You pursed your lips, studying him carefully. He was too thin, almost skeletal. You imagined that this was due to both his condition as a slave and his "profession" as a dancer. He needed to maintain a slim physique, but this seemed excessive, almost unhealthy. Something in you revolted at this.

"I would like some company." You insisted, your voice coming out a little firmer than intended. Maybe even harsh, but you didn’t mean to intimidate him. You took a deep breath and softened your tone, "Please."

Bagoas hesitated for a moment, his expression remaining neutral, but you saw the tension in his shoulders relax slightly. He took a step forward, obeying your request. It wasn’t often that someone in your position insisted that he stay, and the gesture didn’t go unnoticed by him.

As he approached, you pushed the tray aside, indicating for him to sit. You weren’t sure exactly why you felt the need to keep him close at that moment. Maybe it was the heavy silence that surrounded you, or the need for a human gesture in a place where everything seemed cold and calculated. Whatever the reason, you knew you didn’t want to be alone.

Although Bagoas' company was silent, you felt comfortable around the eunuch. And from the slight smile on his stoic, handsome face, you knew he felt the same, even if he didn’t show it.

The little gestures really do count.

It was a rare occasion to be summoned for an audience with Darius. The Persian king generally preferred to keep you away from the intrigues of the court and the politics that were raging around him, especially now, considering your condition. You knew that this distancing was motivated more by political expediency than personal kindness, but it was a relief nonetheless. The last thing you needed was more stress amidst the chaos that already dominated your life.

Sighing deeply, you smoothed the red tunic you wore, trying to calm your nervousness before entering the room. The fabric slid softly under your fingers, but it did nothing to dispel the feeling of unease growing in your chest. As you crossed the threshold, your eyes immediately fell on Darius, sitting in the center of the opulent room. He smiled warmly, as he always did when he saw you, a polite gesture that you were unsure if it was genuine or strategic.

Beside him, however, stood Bessus, whose presence was like a thorn in your flesh. Just seeing him made your stomach turn. Every few interactions you’d had with him had been unpleasant enough to last a lifetime. His dark eyes glittered piercingly as he watched you, his expression colder than Darius’s, almost as if he were sizing you up.

Darius, however, maintained his serene and welcoming posture, pointing to a chair next to Bessus, "Welcome. Please, have a seat."

You hesitated for a brief moment, but knew that refusing was not an option. You walked to the indicated place with controlled steps, each movement calculated to mask the discomfort you felt. The air seemed thicker there, charged with unspoken tension, and as you took your seat, you couldn’t help but wonder what the reason for this unusual meeting was — and if Bessus was part of the reason you had been summoned.

Darius cleared his throat before standing, moving with the calm and elegance expected of a king. He took a jug of wine from a nearby sideboard and began filling the cups on the table: first Bessus’s, then yours, and lastly his own. You smiled politely and thanked him in a low tone, even though you knew you wouldn’t touch the drink.

"Why don’t we get straight to the point?" Bessus said abruptly, breaking the silence. His eyes, cold and calculating, turned to Darius, who sighed at his relatives' impatience.

With a resigned look, Darius sat back down, adjusting himself in his chair and straightening his back in a regal posture. He picked up his wine glass, taking a sip before speaking, "What my relative means," He began, his tone gentler than Bessus’s, "is that we would like to hear your opinion on Alexander’s next moves."

You froze for a brief moment, feeling the weight of Darius’s words. This was it. Of course it was. Your heart began to beat faster as your mind processed the situation.

Undeterred by the storm that was brewing inside you, you placed one hand on the table and the other instinctively on your belly. Your gaze fell on the surface of the table as you tried to gather your thoughts. What could you possibly say?

Normally, you would have a clear idea of Alexander’s next steps. Before all this, before you were thrown into this time, you knew his story from books, studying his military campaigns, his strategies, and even the consequences of his decisions. But now... Everything was wrong.

The events unfolding before you did not match what you knew. History had changed, and that left you completely disoriented. And even if you knew what Alexander would do, you could not, would not betray him. You couldn't, even if you wanted to.

Betrayal, after all, was something you could not bear. Not like Perdiccas did. And more than that, you knew that a Persian victory could be catastrophic. The Hellenistic Age had to happen, whether you wanted it or not. It was a crucial moment in the development of Western civilization, a turning point that could not be avoided.

Taking a deep breath, you looked up, trying to appear calm and thoughtful.

"It’s hard to predict Alexander’s moves." You began, choosing your words carefully, "He’s an unpredictable man, and his strategic mind is... Unique. Every step he takes seems calculated, but at the same time, he’s capable of surprises that no one expects."

You stopped, looking at the two men in front of you.

"However, I believe that underestimating him would be a fatal mistake. He’s ambitious, yes, but he’s also much more than that. He fights with a determination that comes from something greater than just power or conquest."

You sighed and frowned slightly, "I don’t know what he’ll do next. Alexander hasn’t shared his plans with me, so I’m of no use to you in this matter."

Darius tilted his head slightly, considering your words. Bessus, on the other hand, just narrowed his eyes, clearly dissatisfied with the lack of concrete information. You stood firm, knowing that even surrounded by suspicion, you had protected not only Alexander, but the course of history.

Darius sighed deeply and turned calmly to Bessus.

"Satisfied? I told you this would be useless." His tone was slightly irritated.

Bessus took a sip of his wine before setting the cup down with deliberate slowness. He arched an eyebrow, a thin smile forming on his lips.

"Really? But then, why don’t I believe a word our guest is saying?"

His words struck you like a sharp blade. Your heart raced, the discomfort in your chest growing rapidly. There was something in the way he spoke, so full of venom, that it made your skin crawl. He was testing you, teasing you, trying to draw out something from you that he suspected was hidden.

You kept your eyes locked on his, feeling the anger rise inside you, hot and pulsing. It was rare that you allowed yourself to feel something so intense, but Bessus seemed to have a talent for bringing out the worst in you. His gaze hardened, his voice coming out firm, almost defiant.

"I'm not lying."

The room seemed to grow quieter, as if even the air had stopped to listen. Bessus leaned forward slightly, his dark eyes taking in every detail of your face. For a moment, it seemed like he was going to say something else, but Darius intervened, his deep voice cutting through the tension.

"Bessus, that’s enough." The authority in his tone left no room for argument. He turned to you, offering you an almost placating smile. "Forgive my relative. He has a tendency to be... Too direct."

You only nodded slightly, though anger still burned inside you. You wanted to say more, but you knew that any extra words could be used against you. Bessus remained silent, but the suspicious glint in his eyes told you that he was still not convinced.

The tension in the room was palpable, but you knew that you had come away from this confrontation without compromising yourself. For now.

Darius frowned slightly, clearly bothered by Bessus’s stance. He placed his wine glass on the table with a deliberate gesture and stood up.

"Bessus, you are no longer needed." Darius spoke, his voice low but full of authority. He looked at his relative with a mixture of patience and warning. "Why don’t you give us a moment?"

Bessus looked like he wanted to protest, but Darius’s steady gaze made it clear there was no room for objection. He snorted discreetly, pushing his chair back with a loud thud and standing up.

"As you wish, Your Majesty." Bessus replied, his tone dry and barely concealing his displeasure. He gave you one last look, his eyes still full of suspicion, before leaving the room.

When the door closed behind him, Darius sighed heavily, as if he had just dealt with an especially stubborn child. He sat back down, relaxing his posture a little, and looked at you with a friendlier expression.

"Forgive Bessus," Darius said with a slight shake of his head. "He is an intense man. And, unfortunately, a bit suspicious by nature."

You nodded, trying to remain calm. You could still feel the adrenaline coursing through your veins, but the absence of Bessus made the atmosphere considerably lighter.

Darius studied you for a moment before continuing, his tone now more relaxed:

"I wanted to take this opportunity to thank you for your... Patience. I know your situation here is not exactly what you would have chosen, but I hope you know that we are doing our best to make you comfortable."

His words seemed genuine, and for a moment you felt less like a prisoner and more like a guest — though you still knew full well that it was a precarious position.

"Thank you, Your Majesty." You responded softly, trying to hide the confusion you felt.

He smiled, a gesture that seemed almost fatherly.

"You are very perceptive, you know? I see it in the way you choose your words. A rare but appreciated talent in a Queen."

You blinked, surprised by the unexpected compliment. You didn’t know if he was trying to manipulate you or if he truly admired your ability to navigate the delicate political dance of that court.

Darius raised his cup again, though not to toast, but to sip the wine calmly.

"Now, please tell me," He began, his tone almost casual, "is there anything we can do to make your stay more pleasant?"

The friendly gesture took you by surprise, but the question seemed sincere. It was hard not to wonder what the true intention behind his kindness was.

But maybe... Maybe Darius really was just kind and cared enough about you.

#tlq#the lost queen#imagine#oneshot#yandere history#yandere historical characters#x reader#commission#alexander the great x reader#yandere alexander the great#yandere alexander the great x reader#darius iii of persia#bessus#💻 anon#bagoas

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basil Lekapenos - a powerful eunuch and ruler of Byzantine empire. He was an illegitimate son of the Byzantine emperor Romanos I Lekapenos who served as the parakoimomenos and chief minister of the Byzantine Empire for most of the period 947–985, under emperors Constantine VII, Nikephoros II Phokas, John I Tzimiskes, and Basil II. His mother was a slave woman of "Scythian" (possibly implying Slavic/Bulgarians) origin. From his father's side, he had Macedonian and Armenian roots. Basil was a close friend of emperor John Tzimiskes. Basil himself took part in the great campaign against the Rus' in Bulgaria in 971, having been entrusted with the reserve forces, the baggage train and the supply arrangements, while Tzimiskes himself with his elite troops marched ahead. His enormous wealth enabled Basil to become, according to the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, "one of the most lavish Byzantine art patrons". "Psellos characterized him as the most remarkable person in the Roman empire, outstanding in intellect, bodily stature, and regal in appearance." As an artifice shaped by human hands, Basil Lekapenos became skilled in rhetoric, diplomacy, warfare; he possessed avid desire for wealth and power, subtle taste, and an eye for exquisite shapes. This eunuch's adorned body could be equated to the beautiful Limburg container. It is this brilliant form in which power resides. The eunuch is the angelic guard and protector; the face and body of the empire, in brief—the container of the empire. Relic and reliquary work in tandem, a pair suspended between presence and absence, between inaccessible energy—the emperor—and sensual experience of an iconized container—the eunuch."

— Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 51: Spring 2007. By Francesco Pellizzi

The history of Byzantium is dotted with examples of what some historians condemn as over-powerful eunuch courtiers, who attempted to dominate their rulers. From Chrysaphios in the fifth century, Euphratas under Justinian, to Staurakios and Aetios, Samonas in the ninth, Basil Lekapenos in the tenth, and John the orphanotrophos (in charge of the large Imperial Orphanage in Constantinople) in the eleventh, the list is extensive. Basil Lekapenos, an illegitimate son of Romanos I, known as ‘Nothos’ (‘the Bastard’), made a particularly successful career. After being castrated as a child to destroy any imperial ambitions he might have developed, he was appointed parakoimomenos by Constantine VII. He held on to great power through the rule of Nikephoros II and John I, and practically governed the empire during the first decade of Basil II’s reign (976–85). With his great wealth, he commissioned magnificent art objects such as the Limburg reliquary. He also wrote a treatise on naval battles and had it copied in a splendid manuscript of military Taktika.

In this respect, Basil Lekapenos was typical of several high-ranking eunuchs who became art patrons, diplomats, generals, administrators, teachers, writers, theologians and churchmen (plate 10). In many cases these officials were detached from their court duties to undertake particular missions, diplomatic or military, such as Andreas, who negotiated with the Arabs in the seventh century, or Theoktistos, who commanded the navy in the ninth century. In Byzantium, as in the caliphate, eunuchs regularly found employment as military generals and diplomats. Their high status is confirmed in the Book on the Interpretation of Dreams, written by a Christian Greek author, Achmet, who drew on Byzantine and Arabic sources as well as on his own dreams. In common with many authors, he equates beautiful eunuchs with angels. Both of course were considered sexless beings, since angels have no sex and eunuchs were supposed to have lost theirs.

As well as these high-ranking eunuch officials, others made careers far away from the Great Palace and imperial patronage. They appear incidentally in hagiographical sources, and sometimes feature on a list of wedding gifts, as in the story of Digenes Akrites, the frontier hero. When Digenes Akrites finally married the girl (she is never named), her eldest uncle presented them with ten boys:

Sexless and handsome with lovely long hair, Clothed in a Persian dress of silken cloth With fine and golden sleeves about their necks. — Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire by Judith Herrin.

About eunuchs' appearance in Byzantium. As he [Andrew] sat on the ground in front of the gateway there came a young eunuch who was the chamberlain of one of the nobles. His face was like a rose, the skin of his body white as snow, he was well shaped, fair-haired, possessing an unusual softness, and smelling of musk from afar. [Another variant: beautiful young eunuch, with blond hair (epixanthos), a face like a rose and a body white like snow] -- Life of St Andrew the Fool.

Basil had a luxurious palace with 3000 servants, and he also built the most beautiful church of St. Basil, full of gold and decorations. It is said that when his nephew Basil Porphyrogenitus destroyed this church, Basil the eunuch fell from a stroke and was paralyzed, and later he died in the monastery.

Psellos records that In 985, the emperor Basil Porphyrogenitus assumed personal rule and banished Basil Lekapenos who soon after died "his limbs…paralysed and he a living corpse".

***

"In the course of Byzantium’s long history, a few individuals effectively ruled the empire without occupying the imperial throne. One of the most interesting of these figures was Basil the Nothos, or Basil the Parakoimomenos, who was the main power beside or behind the throne for most of the period from 945 to 985.

This he did until 985, when Basil II, no longer a teenager, could no longer bear his own exclusion from power. The vindictiveness with which he not only removed the Parakoimomenos from office, but also sought to destroy the latter’s political legacy, is a measure of how complete the elder Basil’s political control had been. It was a political control that both amassed and expended great wealth, both facilitating and relying on an extensive network of social and cultural patronage. The greatest beneficiary of this patronage, the monastery that Basil founded in the name of his patron saint, has disappeared almost without trace, but his sponsorship has been seen, or surmised, in numerous cultural artefacts of the later tenth century, and interest in his role as the last patron of the “Macedonian Renaissance” shows no signs of abating.

At the centre of the Parakoimomenos’ quasi-imperial power and patronage was his oikos, which was no doubt appropriate to his status. Indeed, his house and household are mentioned no less than four times in literature of the period. According to Leo the Deacon, Basil was able to mobilise and arm over three thousand “household members” (οἰκογενεῖς) in support of Nikephoros Phokas in 963. The same author later records that he had witnessed a bright star descending on the house of the proedros Basil; this portended Basil’s death shortly afterwards and the looting of his property

There is an additional reason for seeking the house of Basil the Parakoimomenos in the area of the Embolos of Domninos. This is because it was somewhere to the west of the Embolos that Basil established his monastery of St Basil, which was famously stripped of its wealth and its ornaments by Basil II."

-The House of Basil the Parakoimomenos, by Paul Magdalino

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

"During the reign of her husband the primary function of an Augusta was the orchestration of ceremonial at the imperial court, a highly stylised and intricate affair given the ceremonial nature of imperial life, which was based primarily around the Great Palace, a huge complex extending from the hippodrome to the sea walls, with its own gardens, sporting grounds, barracks, audience halls and private apartments; the Great Palace was the official residence of the emperor until 1204, though under Alexios Komnenos the imperial family usually occupied the Blachernai Palace in the north-west of the city, while there were other residential palaces in and outside of the capital. Empresses’ public life remained largely separate from that of their husbands, especially prior to the eleventh century, and involved a parallel court revolving around ceremonies involving the wives of court officials. For this reason an empress at court was considered to be essential: Michael II was encouraged to marry by his magnates because an emperor needed a wife and their wives an empress.

The patriarch Nicholas permitted the third marriage of Leo VI because of the need for an empress in the palace: ‘since there must be a Lady in the Palace to manage ceremonies affecting the wives of your nobles, there is condonation of the third marriage…’ While the empress primarily presided over her own ceremonial sphere, with her own duties and functions, she could be also present at court banquets, audiences and the reception of envoys, as well as taking part in processions and in services in St Sophia and elsewhere in the city; one of her main duties was the reception of the wives of foreign rulers and heads of state. Nor were empresses restricted to the capital: both Martina and Irene Doukaina accompanied their husbands on campaign.

The empress was also in charge of the gynaikonitis, the women’s quarters in the palace, where she had her own staff, primarily though not entirely composed of eunuchs, under the supervision of her own chamberlain; when empresses like Irene, Theodora wife of Theophilos, and Zoe Karbounopsina came to power they often relied on this staff of eunuchs as their chief ministers and even their generals. Theodora the Macedonian was unusual in not appointing a eunuch as her chief minister, perhaps because her age made such gender considerations unnecessary. The ladies of the court were the wives of patricians and other dignitaries: a few ladies, the zostai, were especially appointed and held rank in their own right. The zoste patrikia was at the head of these ladies (she was usually a relative of the empress),and dined with the imperial family."

Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium AD 527-1204, Lynda Garland

#history#women in history#women's history#byzantine empresses#byzantine empire#byzantine history#eastern roman empire#queens#historyedit#historyblr#medieval history#irene of athens

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Perdiccas

Perdiccas (d. 321 BCE) was one of Alexander the Great's commanders, and after his death, custodian of the treasury, regent over Philip III and Alexander IV, and commander of the royal army. When Alexander the Great crossed the Hellespont and threw his spear onto the shore of Asia Minor, he and his loyal army began a ten-year journey that would take them to the far reaches of Asia, amassing an empire unlike any that had existed before it. However, the young king's sudden death in 323 BCE left a vast kingdom leaderless and in disarray; there was neither an immediate heir nor appointed successor. Perdiccas stepped to the forefront to offer a solution. With the king's signet ring in his hand, he attempted to keep the empire intact. Unfortunately, others loyal to the king maintained a different opinion. In the end, the various commanders took possession of their small piece of the territorial pie, leaving Perdiccas with only a slim chance of rebuilding what had already been lost.

Early Career

Perdiccas stepped to the forefront to offer a solution. With the king's signet ring in his hand, he attempted to keep the empire intact.

Much of what history knows about Perdiccas is not flattering, clouded by the hostile account in Ptolemy's history of Alexander and his conquest of Persia. Ptolemy I and Perdiccas had been constantly at odds with one another since Babylon, a conflict that would eventually lead to Perdiccas' death. However, other than Ptolemy's history, most dependable versions maintain that he was about the same age as Alexander (possibly a little older) and was the son of Orontes, a Macedonian noble from the House of Orestes, a royal family that had once ruled a small independent kingdom in the Macedonian highlands but whose power had been stripped by Philip II, Alexander's father.

Initially, Perdiccas was a page in the imperial court at Pella, but in 336 BCE he became a member of Philip II's elite infantry, a shield-bearer or hypaspist. Later in the same year, serving as a king's bodyguard, Perdiccas was one of many who pursued Pausanias, Philip's murderer. The reason for the murder: Pausanias believed the king had betrayed him and sought revenge. When the assassin's boot caught on a vine as he hopped onto his horse, he was immediately slain by his pursuers. History still debates whether or not Olympias, Alexander's mother, had anything to do with the death of his husband. Many still believe she encouraged Pausanias to kill Philip to ensure Alexander's ascension to the throne. One of these was Plutarch who wrote in his The Life of Alexander the Great,

… when he found he could get no reparation for his disgrace at Philip's hands, watched his opportunity and murdered him. The guilt of which fact was laid for the most part upon Olympias, who was said to have encouraged and exasperated the enraged youth to revenge… (11)

Continue reading...

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Homosexuality in History: Kings and Their Lovers

Hadrian and Antinous Hadrian and Antinous are famous historical figures who epitomize one of the most well-known homosexual relationships in history. Hadrian, the Roman Emperor from 117 to 138 AD, developed a close friendship with Antinous, a young man from Egypt. This relationship was characterized by deep affection and is often viewed as romantic. There are indications of an erotic component, evident in Hadrian's inconsolable reaction to Antinous's tragic death. Hadrian erected monuments and temples in honor of Antinous, underscoring their special bond.

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion The ancient world was a time when homosexuality was not as taboo in many cultures as it is today. Alexander the Great and Hephaestion are a prominent example of this. Alexander, the Macedonian king from 336 to 323 BC, and Hephaestion were best friends and closest confidants. Their relationship was so close that rumors of a romantic or even erotic connection circulated. After Hephaestion's death, Alexander held a public funeral, indicating their deep emotional bond.

Edward II and Piers Gaveston During the Middle Ages, homosexuality was not as accepted in many cultures as it is today. The relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston was marked by rumors and hostilities, demonstrating that homosexuality was not always accepted in the past. Their relationship is believed to have been of a romantic nature, leading to political turmoil and controversies. Gaveston was even appointed Earl of Cornwall by Edward, highlighting their special connection.

Matthias Corvinus and Bálint Balassi In the Renaissance, there was a revival of Greco-Roman culture, leading to increased tolerance of homosexuality. Matthias Corvinus ruled at a time when homosexuality was no longer illegal in Hungary. The relationship between Matthias Corvinus and Bálint Balassi is another example of homosexuality being accepted during this period. Matthias Corvinus had a public relationship with Bálint Balassi, a poet and soldier. Their relationship may have been of a romantic nature, as Balassi was appointed as the court poet, and it had cultural influence.

These relationships between the mentioned kings and their lovers are remarkable examples of the long history of homosexuality in the world. In many cultures of antiquity and the Middle Ages, homosexuality was not as strongly stigmatized, demonstrating that homosexuality was not always rejected in the past.

Text supported by Bard and Chat-GPT 3.5 These images were generated with StableDiffusion v1.5. Faces and background overworked with composing and inpainting.

#gayart#digitalart#medievalart#queer#lgbt#history#gayhistory#KingsLovers#manlovesman#powerandpassion#gaylove

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in “Sal, what the fuck are you talking about?”: the middle Byzantine period.

The period from the mid-ninth century to the late 11th was defined by a resurgence in the empire’s fortunes, as the Abbasid Caliphate weakened and the bloody stalemate on the eastern border yielded to conquest, plunder, and expansion into regions that the empire hadn’t controlled for centuries. Domestic politics responded predictably to this influx of land, wealth, and prestige: the generals who led these conquests became immensely rich, respected, and in some cases powerful enough to make themselves emperor. Byzantium had never had a true hereditary aristocracy—when you died, your titles generally died with you—but these guys came pretty close, as a few dozen intermarried clans came to dominate both military and civilian politics for generations.

Making military leadership into a family business generally went well, as future commanders could begin learning the trade from a young age, instructed by the most experienced leaders in the empire. The downside was that their egos grew along with their conquests, and when they felt they weren’t being treated with the honor due to such a distinguished family, they had all the resources they needed to launch a rebellion against the throne. This happened again, and again, and again, and again; it’s no coincidence that this was the period when surnames became common among the wealthy.

In the palace, this era was defined by the so-called Macedonian Dynasty, a string of emperors and usurpers founded by Basil, a peasant from—you guessed it—the military district of Macedonia. Basil took the throne by becoming the emperor’s confidant and most trusted servant, before quite literally stabbing him in the back.

The next two centuries saw an alternating series of Basil’s descendants and usurpers take the throne, with coups and rebellions too numerous to list here. Basil’s heirs had a tendency to die while their sons were still minors (or to leave no sons at all), leaving a mad scramble for a new man to marry or kill his way into the imperial family. This was also the heyday of the court eunuch, as aristocrats looked for servants who would serve their family without trying to displace them in favor of their own sons; of course, plenty of eunuch did displace emperors in favor of their own friends and family, or else overshadowed them so completely as to become the functional ruler themselves.

Culturally, this period was quintessentially Byzantine. Emperors were very concerned with soft power, so they poured money into anything that would make them seem like the holy sovereign they considered themselves to be—histories, encyclopedias, churches, monasteries, public games, bejeweled reliquaries, and the like. Foreign ambassadors were feted with gold and silk in front of a throne that could rise from the floor until the emperor was looking down at the from the heavens. My favorite piece of writing from this era is the Book of Ceremonies, which spends hundreds of pages detailing the protocol for every imaginable public event, from the order of seating at imperial feasts to the proper weight of cargo loaded onto an army packhorse; it shows how the emperors tried to synthesize the importance of orderly, standardized, professional administration with the need to appear wise, just, and all-powerful to their subjects. It also shows how unbelievably wealthy the government was—very few states, at any point in history, had the time and resources and literal tons of gold to spend on court ceremonies that intricate and impressive!

I’ll spare you the list of emperors, their personalities, and the various schemes and subordinates that put them on the throne; that’s a whole separate post. Suffice to say that I think this is one of the most interesting eras of history, and I encourage everyone to learn more about it.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Cool Jewish Women from Modern Day! Part 1

Raquel Montoya-Lewis, an American attorney and jurist on the Washington Supreme Court. Born to a father descended from the Pueblo of Laguna, she is a member of the Pueblo of Isleta. Her mother, born in Australia, is Jewish. She was also a professor at Fairhaven College, and was a judge for indigenous courts including the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe and the Nooksack Indian Tribe. She is the second Native American person to sit on a state supreme court, and the first enrolled tribal member!

Dana International, an Israeli pop singer. Born in Tel Aviv to a family of Yemenite descent, she identified as female from a very young age, and was inspired by Ofra Haza to become a singer. Dana was chosen to represent Israel in Eurovision 1998 with the song "Diva," and won the contest with 172 points. She represented Israel again in 2011.

Liora Itzhak, an Israeli singer from the Bene Israel Indian community. She moved to India at the age of 16, returning to Israel eight years later. While in India, she sang with Kumar Sanu and Udit Narayan, and performed in the Bollywood film Dil Ka Doctor. Her music has gained recognition in both Israel and India. During the Indian Prime Minister's visit to Israel in 2017, she sang the national anthems of Israel and India.

Carol Man, a Hong Kong artist born into a traditional Chinese family. She converted to Judaism, and often combines Jewish and Chinese elements into her work, which includes a step-by-step guide to Chinese-Hebrew calligraphy. Featured in the Jewish Renaissance magazine and the Jewish Art magazine, she often gives workshops on her style of art.

Qian Julie Wang, a Chinese American writer and civil rights lawyer. Her father was a professor of English and critic of the government, which led to her family having to flee China. She graduated from Swarthmore College with a BA in English Lit, and earned her JD from Yale Law. She converted to Judaism, and founded a Jews of Color group at Manhattan Central Synagogue.

Sarah Avraham, an Indian born Israeli Muay Thai kickboxer. She was born in Mumbai to a formerly Hindu father and a Christian mother. Her family was close friends with Gavriel and Rivka Holtzberg, who were killed in the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks. A year after the attack, her family converted to Judaism and moved to Israel. She volunteers as a firefighter, and is considering studying medicine. In 2012, she won the Israeli national women's Thai boxing championship in her weight class; in 2014, she won the Women's World Thai-Boxing Championship in Bangkok in her weight class.

Leza Lowitz, an American writer born in San Francisco who has written, edited, and co-translated over twenty books. She is an internationally renown yoga and mindfulness teacher. She has often written on the topic of expatriate women. She is married to a writer and translator, and has one son. Her work is archived in the Chicago U library's special collection of poetry from Japan.

Ellie Goldstein, a British model born in Ilford, Essez. She has been modeling since she was fifteen, and has worked on campaigns for Nike, Vodafone, and Superdrug. She is the first model with a disability (Down syndrome) to represent Gucci and model their beauty products.

Ashager Araro, an Ethiopian-Israeli activist. Born while her parents were traveling during Operation Solomon. She studied government, diplomacy, and strategy at the IDC Herzliya. She is a feminist who has spoken out about racism and police brutality. In early 2020, she opened a cultural center in Tel Aviv dedicated to Ethiopian Israel culture called Battae.

Sarah Aroeste, an American singer, composer, and author of Northern Macedonian descent. Her music often referred to as "feminist Ladino rock." Born in Princeton, her family emigrated to America from Monastir/Bitola during the Balkan Wars. In the late 1990s, she noted the lack of a revival for Sephardic music despite the revival of klezmer, and started her own Ladino rock band in 2001. One of her albums is named after Gracia Mendes Nasi. In 2015, she represented the US in the International Sephardic Music Festival in Cordoba. She has written several books, including children's books, with Sephardic themes. (Fun fact, I met her at the Greek Jewish Festival in New York!)

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

where would i be able to read your monograph? especially about the ‘you are nothing without me’ incident

The Protracted Reality of Writing Academic Shit 😂

First, and assuming the asker means my Hephaistion-Krateros book, the quick answer is: It’s still in process, not even close to being in print. In the meantime, a number of my articles are available on academia-edu.

Now, to explain why the book is “still in process,” let me explain the monograph writing progression. IME, the average person uninvolved in academia is often surprised by the sheer complexity and time involved. (After all, why would you know if you don't need to?)

Below, I talk only about academic monographs, although I’ve also edited academic collections, and of course, have published a number of articles. I started to tackle fiction publishing too, but that quickly devolved into a long-ass post (even for me), so I’m sticking only to the topic the asker requested. It's long enough! Maybe I’ll do fiction later, assuming anybody wants to read that. (If so, put it in an ask.)

To write an academic book in the humanities typically takes years. There are several stages just to produce the initial manuscript, never mind getting it into print. I’ll outline the general process below, using my current project to illustrate the steps. One thing I’ve found consistently among both students and non-academics is utter surprise at just how extensive research/writing is. New grad students often think writing a thesis/dissertation is akin to writing a really long term paper. Oh, no. You will write it, submit it, get critique and feedback, go research some more and revise it, get critique and feedback, go and research yet more and revise it again … rinse and repeat. How long? Until it’s cooked. There’s not a set timeframe. It will always take longer than you expect. Always. I’ve been teaching grad students almost 25 years. I have yet to have any require less time than they first assumed.

Writing a monograph (including the thesis/dissertation, which is a type of monograph) is one of the toughest forms of academic writing. Papers/articles are much easier, and not just because they’re shorter, although that’s some of it. They also generally have a simpler point. They’re proving ONE thing, like a string.

A monograph presents a coherent, complex argument like a rope woven from several strings (the chapters). It’s not an edited collection by multiple authors in a single volume (or two), or even a collection of various essays by a single author. Collections may have a general topic, like, say, Macedonian Legacies (the collection we did for Gene Borza), or the one I’m editing now, Macedon and It’s Influences. Just trying to figure out a decent order for the varied papers can prove a challenge in these. If some of the papers actually do bear on each other … bonus! But the papers aren’t necessarily expected to come together at the end in any cogent way. A monograph’s concluding chapter should, however, bring together the chapters into a solid conclusion, like the arch’s capstone, holding it all together.

Yet the researcher may not know the answer to that until done with much of the research. After reading everything, and considering it, she may wind up in a different place from where she started. Like any good, responsible research, the researcher must be prepared to follow the data and facts, not cram them into a preconceived notion. I’ve changed some of my ideas and goals for my current monograph, as I no longer think I can do the project I originally intended because the nature of the sources get in the way too much. But I have a more interesting project as a result.

The first phase is research: pretty much for any academic field, period. How this progresses, and how quickly, varies with the individual, field, and topic. Furthermore, some of us are planners (that’s me), others are pantsers (e.g., they dive in and figure it out as they go: by the seat of the pants). But we all start with a question or observation, then go out to track down information about it. In history, sometimes we just read the primary sources/archival material and see what we find. Something strikes us, so we go on to read more, which produces either refined questions or entirely new ones.

Right now, I’m finishing up the initial stages of the research. Then I’ll start work on the chapters, which, yes, I’ve outlined as a result of my initial research. But those chapters may (and probably will) morph as I write them. It’s during the writing phase that the other, “attendant” research comes into play: chasing down all the references in other secondary sources for smaller points. Rabbit-hole time.

My initial research tends to be more measured. I read a while, stop to think—sometimes do stuff like write replies to asks on Tumblr while my brain churns. 😉 Then I go back and read some more. But the writing phase is where I can lose all track of time while running down just-one-more-citation-then-I’ll-stop. The last time I looked at a clock it was 3pm and now it’s 9pm, I’m weak with hunger, I really have to pee because I’m drinking too much tea, and the cats are mad because I’ve not fed them in hours. 😆 It’s two really different types of research for me.

Anyway, for the initial (pre-writing) stage, there are really two substages. The first is what I think of as archival work: e.g., getting down and dirty with the original (primary) sources, including digging into the Greek and Latin to see what it actually says, and if there’s something noteworthy in the phrasing. At this point, I may not really know what I’m looking for, except in the broadest sense. For my current project, I collected every single mention of Hephaistion and Krateros in the original sources. For all five ATG bios, I read them front to back, tagging all sorts of things, plus large chunks of important other books (e.g., the first part of book 18 of Diodoros, the extant fragments of Arrian’s After Alexander, plus a couple bios, esp. Plutarch’s Eumenes, etc.) in order to get a FLOW, not just collect things piecemeal. There are some passages that may not name Hephaistion or Krateros specifically, but they would include them. Piecemeal will always be incomplete, like trying to see a clear image in a broken mirror (a mistake I made with my dissertation, in fact, but I was young).

Then I assembled all that collected data on huge sheets, arranged by author for each man, so I can cross-reference and compare. I also did a deep-dive across 4 days, grabbing everything in Brill’s New Jacoby (BNJ), so I can also tag the original (lost) author cited in our surviving sources, where we know who it is. Not actually that many, but it’s useful and can prove significant. I want to see where the same information, or anecdote, crosses sources, and how it changes.

All of that (except adding the BNJ entry #s to my big sheets) is now done. The next step is figuring out what it all means. For that—and where I am right now—involves historiographic reading/rereading of secondary sources on the ancient authors. What is Curtius’s methodology? Arrian’s? Plutarch’s? What are the themes of each? What is the story they’re telling? They’re not just cut-and-pasters from the original (now lost) histories; they have agendas. What are they? How do Hephaistion and Krateros fit into those agendas? How do the sources use them? This is, to me, the really interesting piece.

It's also why this book will not be just a cleaned-up version of my dissertation, but a completely new look at Hephaistion, and now Krateros too. I haven’t even consulted my old dissertation chapters. I started over from scratch. Sure, I remember my main conclusions, and as I write, I’m sure I’ll go back to check things, but the same as I’d check anybody else’s.

I’d hoped to start writing by May, but I’m not quite there yet, in part because, between the Netflix series plus helping to write/edit a grant that I didn’t expect to have to do, I lost virtually all of February. Now, about half of April has been eaten by home repair/yard stuff plus small family crises. That’s just the nature of a sabbatical, especially if you don’t have a spousal unit or SO to take care of everything for you while you just write. 😒

Now I hope to start writing by mid/late May. But as this 9th International ATG Symposium is looming in early September, plus I go back to teaching in the fall, I’ll have to knock off by the end of July, if not sooner. Ergo, not a long writing time. I can do some more during winter break, but I probably won’t have a draft done until next summer. If I’m lucky. It is just not possible, at least for me, to write while teaching! As I do plan to present at least one (startling!) piece of my research as the ATG conference, I have a concrete deadline for a subchapter bit. Ha.

So, what happens after a draft is done? Well, if one is smart, one finds a reader or three. One just to read it for sense, but (if possible) another specialist to start poking holes in the arguments, noting secondary sources one forgot, and to offer general pushback in order to refine it all. This assumes your friends/colleagues actually have time to look at it, as they, also, are teaching and writing their own stuff. (I’ll go after my retired colleagues.) At the same time, one may also begin seeking an academic publisher.

It’s important to match the project to what the publisher is already publishing. It can also help, but isn’t necessary, to have an in: somebody known to/trusted by the editor of one’s broad field (ancient history, in my case) who can vouch for the scholarship. Submitting means writing up a summary of the work, perhaps including letters from colleagues/readers, etc., etc. I’m not even close to this stage yet, so I’m primarily going by the experiences of friends. At this point, it starts to dovetail a bit with fiction publishing. You’re on the hunt and do some of the same homework.

Once a publishing house requests the manuscript, they’ll farm it out to 2-3 readers to evaluate. This is the “refereed” part, as the readers will be specialists in the field. The publisher, who can’t be a specialist in everything, may ask for a list of names for these potential readers.

As with academic papers/book chapters, the book will come back from these readers with a vote on publishability, plus suggestions for improvement. The basic choices range from, “Go back to the drawing board; this has major issues and here they are” (e.g., not ready yet for publication). To, “It’s got good bones but here are improvements on chpts X and X, oh, and go read ___ works you forgot,” (e.g., revise and resubmit). To, “this is pretty solid as-is but could use a few more things” (e.g., revise but ready for a contract). You will NEVER get a “Publish it right now.” 🤣 It’s hard to say how much time this revising phase will take, as it depends entirely on the level of revisions requested. This is why it’s often wise to find a reader or three in advance, to make this phase less lengthy. Yes, books do sometimes get turned down entirely, with no “revise-and-resubmit,” but more often it’s one of the three above. And yes, sometimes an author may be unwilling to make the requested changes, so finds a different publisher, with different readers, hoping for a more positive outcome. Sometimes, with the revising stage, there’s a non-binding contract involved, but this seems to be useful mostly for younger scholars who need some sort of proof for their RPT (Reappointment, Promotion and Tenure) committees.

Once a publisher gets a manuscript they believe is worthy, the author receives a (real) contract and is provided with in-house editors to fix grammar, sense, etc.: copy- and line-editing. What would (in fiction) be called “developmental editing” is what the refereed part entailed. This is the simple part. Getting TO the contract stage is the tough part.

The publishing house will then schedule the book with a publication date and discuss things like page-proofs, cover art, permissions, formatting, etc., including indexing, which most publishers either don’t do, or charge a high fee for. It’s almost always cheaper to hire an indexer separately. I’ve already got mine lined up for the Hephaistion-Krateros book. But that can’t be done until it’s typeset and through page-proofs as one needs, yeah, the page numbers. Ha. From contract to the book hitting shelves can take a full year, or more.

So, with the exception of those folks who are just writing machines, the average monograph is c. 5+ years, at least in the humanities. This assumes the luck to get a sabbatical, not trying to do it all crammed into summers or breaks.

So yes, I’m still a couple years from this book seeing print. And that assumes there’s not a lengthy revise-and-resubmit process because my readers don’t like my conclusions.

#asks#Hephaistion#Krateros#monograph on Hephaistion and Krateros#Hephaestion#Alexander the Great#writing an academic monograph#academic publishing#Macedonian Court

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Alexander I of Macedon may have promoted his own image as a royal schemer. Many of his descendants fit his Odyssean prototype. These qualities enabled survival for some, like Perdiccas II, while others, most notably Philip II, were employed these same traits with much greater success. Was there a female version of this prototype? This question is unanswerable about any royal woman before Eurydice, but […] she could indeed be understood as somewhat Penelopean.

The circumstances of Eurydice and Penelope were hardly identical. Eurydice was an actual widow, whereas Penelope feared that she had been widowed; Alexander II actually became king, though only on the threshold of maturity, whereas Telemachus, though of roughly the same age, had not yet become king; Eurydice’s sexual fidelity was brought into question, as we have seen, whereas Penelope’s was not, ultimately, jeopardized. Eurydice and Penelope are, however, similar enough to be illuminating. Penelope moves between the world of women and the male court; she dares to confront her male enemies publicly (16.409– 434) but is impressed when her son tells her to return to her quarters, thus asserting his male adulthood (1.356–364). Her dealings with her son are complicated exactly because Telemachus is not quite a man yet no longer a boy and Penelope had promised Odysseus that she would not remarry until her son had reached some sort of adulthood (18.269– 270). Penelope does and does not want to remarry (e.g., 19.524–534) and her sexuality is often the focus of the narrative (18.158–168), yet her faithfulness to her husband and to her son’s future helped to preserve Telemachus’ inheritance and Odysseus’ household, despite the serious depredations of the suitors. She improvised her way, often by trickery and with some ambiguity, through a prolonged period of instability. Thinking about Penelope helps us to understand Eurydice’s role in the events of her day: she was both a public and a private figure, powerful and yet passive, manipulative and manipulated, her reputation called into question and yet ultimately celebrated."

— Elizabeth D. Carney, Eurydice and the Birth of Macedonian Power

#this is so fascinating to me#eurydike#eurydice#historicwomendaily#macedonian history#greek history#ancient greece#ancient history#my post#women in history

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

.⋆◞❖°・.masterlists◡̈♡._

*:・゚✧.for you, 𝐼 ★•¸— ̶c̶o̶u̶l̶d̶ pretend like ❝.╭.+I w͟a͟s͟ h𝑎ppy°⊹when I was⋆◟̆๑𝓼𝓪𝓭; for you❝.:*。I could p͟r͟e͟t͟e͟n͟d͟˘.+*✦like I ɯαs▾₊˚𝓈𝓉𝓇𝑜𝓃𝑔 wh𝑒𝑛 I。*☆𝙝𝙪𝙧𝙩; ℐ wish・゚。❥love was ᴘᴇʀғᴇᴄᴛ❀⊰。as love ̶i̶t̶s͟e͟l͟f͟╮ⵓ❞¸I ɯısh all あ.♡my 𝔀𝓮𝓪𝓴𝓷𝓮𝓼𝓼𝓮𝓼 could ❞.ᔘ❀be 𝖍𝖎𝖉𝖉𝖊𝖓; I୭.° grew a 𝑓𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑟+*.♡:th𝑎t can't be ↬,。˚𝘽𝙇𝙊𝙊𝙈𝙀𝘿 in a↷.dream•that c͟a͟n͟'͟t͟ come ★*̣̥⁄⁄𝓽𝓻𝓾𝓮৴☽❰❪+

↳¸•.↑✿cited song: fake love by BTS.

➷°.[✩] BTS ╭⟡;💜

➷°.[✩] BLACKPINK╭⟡;🖤

➷°.[✩] ITZY ╭⟡;🧡

➷°.[✩] Stray Kids ╭⟡;💙

く く く EXO: Yandere Baekhyun (Romantic), Yandere Suho (Romantic). く く く TWICE: Imagine as Classmates.

➷°.[✩] Greek Mythology ╭⟡;⚡

➷°.[✩] Egyptian Mythology ╭⟡;𓂀

➷°.[✩] Historical Characters ╭⟡;📜

く く く The Lost Queen | Yandere!Alexander the Great ❝You woke up near a military camp without remembering how and why you got there, you didn't understand why they were dressed like ancient Greeks, all you knew was that you weren't safe and you needed to get out of that place as soon as possible. Too bad for you that you found yourself attracting unwanted attention from the Macedonian King and he won't let you go so easily.❞ The Lost Queen Series Masterlist

➷°.[✩] The Vampire Diaries // The Originals╭⟡;🧛

➷°.[✩] House of the Dragon╭⟡;🐉

➷°.[✩] Game of Thrones╭⟡;❄️

➷°.[✩] The Sandman╭⟡;⌛

➷°.[✩] Outlander╭⟡;🗿

➷°.[✩] Wednesday╭⟡;🎻

➷°.[✩] Brooklyn Nine-Nine╭⟡;👮♂️

➷°.[✩] Bridgerton╭⟡;🐝

➷°.[✩] Shadow and Bone╭⟡;☠️

➷°.[✩] Outer Banks╭⟡;💰

➷°.[✩] K-Dramas╭⟡;❤️

➷°.[✩] Reign╭⟡;👑

➷°.[✩] The Tudors╭⟡;🗡️

➷°.[✩] Hannibal╭⟡;🍽

く く く The Bloody Viscount | Yandere!Anthony Bridgerton ❝You had fallen in love with Viscount Bridgerton and he had fallen in love with you. The marriage seemed perfect, but then why did Anthony Bridgerton always come home late and bloodstained?❞ Prologue; Chapter 1; Chapter 2;

➷°.[✩] Percy Jackson╭⟡;🌊

➷°.[✩] Harry Potter╭⟡;🔮

➷°.[✩] A Court of Thorns and Roses╭⟡;🌹

➷°.[✩] A Song of Ice and Fire╭⟡🔥

➷°.[✩] Attack on Titan╭⟡⚔️

➷°.[✩] Naruto╭⟡🍥

➷°.[✩] One Piece╭⟡👒

➷°.[✩] Death Note╭⟡📓

➷°.[✩] Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug and Cat Noir╭⟡🐞

➷°.[✩] How To Train Your Dragon╭⟡🐲

➷°.[✩] Marvel╭⟡۞

➷°.[✩] DC Comics╭⟡🦸♂

➷°.[✩] Love Letters╭⟡💕

➷°.[✩] Love Letters II╭⟡💕

➷°.[✩] Kinktober 2023╭⟡🎃

#masterlists#masterlist#yandere au#yandere masterlist#yandere greek mythology#yandere historical characters#yandere bts#yandere percy jackson#yandere harry potter#yandere house of the dragon#yandere game of thrones#yandere a song of ice and fire#yandere blackpink#yandere the vampire diaries#yandere the originals#yandere love letters#yandere hotd#yandere anime

561 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have been trying to understand Greek history starting from ancient times , your awesome drawings have greatly helped me find motivation! (I love them all oml they are so cool, you are so talented!! The attention to details of clothes and all! So cool!)

This is my question: is there any part of Greek History or a particular city state that you prefere? Why?

Thank you so much!!

I'm really glad people are learning history through my posts, as passing around knowledge is my key motivator.

Regarding your question, I do prefer Ancient history over any other period (2000-322bc, Hellenistic period is like the black sheep of ancient history), with a particular liking to Macedon (who's a kingdom rather than a city-state).

Probably due to the things I was told while growing up - yes, I'm Macedonian - but also THE DRAMA and the randomness; the back and forth between Philip and Demosthenes, the Macedonian court as in itself, that one myth about Alexander having big ears and having to hide them with his hair-

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arsinoë II lived a dramatic and adventurous life, full of extreme highs and lows. In its course, she played a part in the courts of four kings, married three times (twice to a sibling or half sibling), saw two of her sons murdered, fled two kingdoms because her life was in danger, yet ended her days in great wealth and security and ultimately was deified. Born in Egypt (as the daughter of Ptolemy I Soter and Berenike), she departed as a teenage bride for marriage to Lysimachus, ruler of Thrace, parts of Asia Minor, and Macedonia. After her husband died in battle, she tried to protect the claims of her three sons to rule in Macedonia against the attempts of others to seize the kingdom. In support of this effort, she married one of these rivals (her half brother Ptolemy Ceraunus), only to have this marriage alliance end in a bloodbath that compelled her to return to Egypt, where her brother Ptolemy II had succeeded their father as king. Once back, Arsinoë married her brother (the first full brother-sister marriage of a dynasty that would make such marriages an institution). She died in Egypt, having spent her last years playing a prominent role in the kingdom. Throughout much of her life, Arsinoë controlled great wealth and exercised political influence, but domestic stability characterized only her last few years.