#Larisa Karr

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A taste of history: Soup joumou brouhaha highlights fandom, significance of dish

Soup joumou dish by Chef Alain Lemaire. The signature dish consumed on January First, Haitian Independence Day, offers a taste of both Haitian cuisine and history. Photo: via @cheflemaire

By Larisa Karr

Dixie Sandborn, a Michigan professor, knew nothing about Haitian culture until she began raising the two children she adopted from Haiti. Soon enough, she became very familiar with Haiti and a culinary hallmark: soup joumou.

Now, the soup joumou recipe she’s been practicing for six years makes an appearance at every local potluck the family attends and, of course, on January First, Haiti’s Independence Day.

The soup dish has gained increasing popularity in recent years, particularly as a result of social media. Earlier this month, a Bon Appétit recipe that did not incorporate many of the original ingredients stirred up much controversy and revived spirited discussions online and offline about the significance of the soup.

“When I take the soup to an international dinner, I follow it exactly, because I want it to be authentic,” said Sandborn, who resides in East Lansing. “I decided to write about it because I had a connection to it through my kids and it has a lot of history.”

A taste of history

The dish dates back to 1804, when Haiti declared independence from French colonists, who forbade them from eating soup. It incorporates an array of hearty ingredients, including cabbage, potatoes, meat, Haitian epis, and the squash called “joumou,” Creole for pumpkin. Experts said the soup was originally conceived not just for its enjoyable flavor, but also for health.

As the soup continues to gain a fan base outside the Haitian community, many Haitian-Americans are creating everything from books to hoodies to tell the story of the soup. And with the New Year approaching, people both in the diaspora and in Haiti are planning to hold events to share the soup with their community.

Bayinnah Bello, a professor of history at the State University of Haiti whose courses include “Women and Society” and “First Peoples Civilization” explains why soup joumou holds such significance to Haitians.

“When Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines created the empire of Haiti with her husband, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, her worry was what people could eat to survive, no matter what happened after independence,” Bello said. “She came up with the soup to make medicine and to treat tuberculosis, along with other illnesses.”

Through her organization, Fondasyon Félicité, Bello plans to make the soup with volunteers from all over Haiti this year and distribute the dish to more than 10,000 people.

Preparing the soup is an extensive process. First, the meat must be marinated overnight and then placed in a stockpot with water until it evaporates. As the meat is cooking, the vegetables, including the pumpkin, are washed and cooked over heat for an hour in a separate pot. Spices, as well as pasta, are then added, then the soup must simmer some more. Finally, the meat can be combined into the soup and it is ready to eat.

Chefs emphasize that while there is a standard recipe for soup joumou, ingredients do vary based on family tradition.

“I love the potatoes, carrots, and cabbage,” said Lamise Oyugi, a health administrator and YouTube influencer who has uploaded a soup joumou recipe on her channel. “Everyone makes it differently, and ultimately it’s the way your parents taught you.”

Photo from Food Fidelity.

A teachable moment

Nonetheless, many felt the Bon Appétit recipe was too different to pass as Soup Joumou. Chef Marcus Samuelsson incorporated ingredients that are not found in the soup, including candied, spiced nuts.

The outcry about Samuelsson’s take on the recipe prompted Bon Appétit to issue an apology and change the name of his recipe from “Soup Joumou” when first published to “Pumpkin Soup With Spiced Nuts.”

Still, tempers boiled over in many circles. Some people wrote that Samuelsson’s recipe minimized and downplayed the significance of the soup in Haitian culture.

“I know how proud Haitians are of our soup joumou because it’s one of the things that binds us,” said Gina Athena Ulysse, professor of Feminist Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who wrote Liberate Soup Joumou! Why Haitians Care on Medium in response.

“None of them took a Haitian voice and perspective into consideration and that’s why I specifically wrote what I did,” Ulysse said.

While the Bon Appétit controversy might have ignited the widespread dialogue in the mainstream, experts say it is only part of an ongoing conversation about the role and significance of soup joumou in Haitian culture.

“To consume, to participate and to make soup joumou is to recall the past, enact a present form of resistance, and also to foretell the future,” said Myron M. Beasley, an associate professor of American Studies at Bates College.

“It’s the notion that this food item that was forbidden became the emblem of victory,” Beasley said.

Soup joumou fandom

Although it has been a few weeks since the initial cultural appropriation outcry, scores of people continue to take to social media to educate non-Haitians about the soup dish and its place in history. And with Haiti’s 217th Day of Independence coming up, people seem receptive to learning more than ever.

“I post it online to make sure everybody is familiar with it, as well as telling my coworkers about it,” said Billy Delatour, a DJ and clothing designer based in Roselle, N.J. “Most of my friends love it because it’s different and it’s not your typical chicken noodle soup.”

Soup joumou merch is even available now, as Haitian-Americans use this opportunity to tell the story of the soup and its cultural importance.

Emmanuel Pierre-Louis, a Queens-based DJ who eats soup joumou with his family, has produced hoodies.

“I feel that it’s important to have it on clothing because if someone has never heard of the name or seen it, they will ask what it is,” Pierre-Louis said. “This will be an opportunity for me to teach them the meaning and significance behind it.”

Carline Smothers has received a positive reception for her book, “Mmmmm! Soup Joumou!” Courtesy photo.

The brouhaha also cements the need for more books, which are being written to share the story of the soup for future generations of Haitian-Americans and non-Haitians.

“I was in a room with my children, getting ready to read them a bedtime story, and I realized that I did not have any books that represented who they are,” said Carline Smothers, who has written a book about soup joumou that she sells through her clothing business, Zoe Beautee. “People are now making it a family tradition by taking pictures of my book with the soup and that’s been very rewarding for me.”

#Soup Joumou#cuisine#Haitian cuisine#food#Haitian history#Haiti#Haitian Independence Day#Larisa Karr#The Haitian Times#soup

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via A Tarnished Legacy: Looking back on the effects of the 2016 Rio Olympics)

#Brazil#Olympics#Rio 2016#Rio de Janeiro#analysis#Recount Magazine#Larisa Karr#Olympic Games#reflection

0 notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

Haitian dish “diri djondjon” gains popularity with non-Haitians

Diri ak Djon Djon, known in English as black rice, is an inevitable culinary fixture at Haitian holiday celebrations. Photo from Caribbean National Weekly.

By Larisa Karr

When Minna LaFortune was a young girl in Jamaica, her parents warned her about the small black mushrooms that grew wild around the island, saying the vegetable came from a netherworld of sorts. Years later, after she moved to New York, LaFortune learned otherwise.

“I was at a Haitian party when I was introduced to “diri ak djon djon” and noticed everyone was eating this,” said LaFortune, using the Creole phrase for rice with mushrooms. “I realized that if everyone was eating it, they were proving it to be edible.”

Diri djondjon, the shortened name for the dish in Creole also called “black rice” by English speakers, is a uniquely Haitian dish that is becoming more and more popular with non-Haitians as the culture spreads. Some experts believe the dish originated in northern Haiti and predates Haiti’s independence revolution from French rule. It spread throughout Haiti and, when the diaspora emigrated, became a staple on Haitian tables and holiday celebrations across the globe.

Now, the dish is turning up more and more in non-Haitian kitchens, restaurants and popular cooking shows worldwide. Diri djondjon also makes regular appearances on both Haitian and non-Haitian YouTube channels, personal Instagram accounts and various food blogs.

LaFortune is among those non-Haitians who has written about diri djondjon since having that first taste at the New York City Haitian party.

“Even though I’m not Haitian, I can tell you it’s divine,” said LaFortune, who resides in East Flatbush. “They add cashews, shrimp and lima beans to the rice and this makes it delicious.”

Creole cuisine creativity

Anthony Buccini, a food history specialist who has written an academic paper about diri djondjon, said its creation goes back to slavery on the island of Hispaniola. The slaves often foraged for food and explored the woods of the tropical land. That’s how they came upon the wild-growing vegetable.

The rice also has connections to cuisine from Africa, which the colonizers attempted to erase, Buccini said. Still, the slaves merged these ingredients to create the dish.

“Diri ak djon djon is a beautiful dish that is a symbol of a development of a new Creole cuisine,” said Buccini, who is Italian-American. “It was something they came up with from what they could find in the environment. They remembered the flavors of what they liked to eat, and once they had the chance to control their own diets, the African spirit [of] the cuisine came out.”

For those who grew up with djondjon, memories of the dish passing down through family remain significant.

“When my dad taught me how to make diri ak djondjon, he wasn’t teaching me how to make rice the way I would find in a cookbook,” said Michelange Quay, an independent Haitian-American filmmaker based in Paris. “The sharing of recipes like diri ak djondjon are actually revolutionary tools.”

Preparing authentic diri djondjon involves soaking the mushrooms overnight until the water turns black. That liquid is then used to cook the rice, giving it its distinct color and flavor, along with other Haitian spices. Original iterations called for dried shrimp, known as tri-tri, but various regional add-ins and preferences exist.

Across the diaspora, cashews and lima beans have become increasingly popular add-ins. So have using black Maggi seasoning tablets instead of soaking the mushroom overnight. Or, even sacrilegiously to some, using black rice from a bag.

“For djondjon to get passed [down] from generation to generation, it’s going to be adapted over time,” said Mireille Roc, a Brooklyn-based freelance chef who creates recipes for brands and cookbooks. “I’m sure the way I make it was not the way it was made 100 years ago.”

Roc, who has published her own diri djondjon recipes, said she prefers the original version, but the Maggi tablets are a cheaper and convenient alternative to the rare mushroom.

Covert cooking strategies

Djondjon is banned in the U.S., which Buccini, Roc, and LaFortune believe is because of the FDA’s particularly strong hesitation to allow produce from other countries.

As a result, preparing the dish is usually reserved for special occasions such as holiday celebrations and parties. With the exposure to larger groups in such settings, more non-Haitians have gotten to enjoy the dish.

“A majority of my non-Haitian friends want to know if we can make it and where I think is the best place they can get it,” said Jeanie Seide, an owner of a virtual office management company in Atlanta. “They always ask about diri ak djon djon.”

To keep a stash or supply the mushroom, some people resort to covert strategies.

“Some people are lucky and they know people who can actually sneak djondjon into their suitcase [from Haiti] and bring it here,” said Thecy Faustin, a resident of Irvington, N.J. “You have to package it really well so the smell will not get out of the suitcase.”

However it’s packaged or travels, one thing is clear: diri djondjon has crossover appeal.

#rice#black rice#Djon Djon#Diri ak Djon Djon#Haitian cuisine#Haitian#mushroom#Larisa Karr#food#The Haitian Times

1 note

·

View note

Text

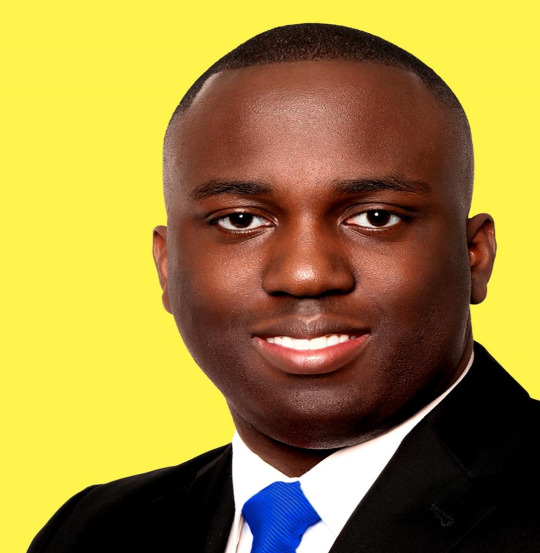

Charnette Frederic, Irvington Council Member, Builds Bridges Through Education

Charnette Frederic, 2nd Vice President of the Township of Irvington, New Jersey. Courtesy photo.

By Larisa Karr

Growing up in the quaint village of Cazale, Haiti, Charnette Frederic’s parents always put education first for their family. Later, when she gave birth to her son in Irvington, New Jersey, she sought to put his education needs first too.

Little did Frederic know that would lead to her entering politics and then becoming the first Haitian-American woman elected to office in New Jersey. As a council member and second vice president in Irvington, Frederic now spends much of her time educating Haitian-Americans in Irvington about resources available. She also teaches city officials about the needs and power of her vibrant community.

“My biggest accomplishment as the only Haitian-American on the council has been to encourage people to work together for the betterment of our community,” said Frederic, 42. “You have immigrants coming in that I constantly try to support, especially with the language issue.”

Recently, Frederic’s efforts to drive voter turnout, reduce insurance burdens on taxi drivers and create an environmentally sustainable city have cemented her reputation as a bridge-builder. Particularly, between the immigrant community made up of mostly Haitian-Americans and city officials.

“She’s a dominant star in bringing people together,” said Irvington Mayor Tony Vauss. “She calls me on behalf of her constituents and she’s constantly connecting them with people in the administration through the different departments they need to be in contact with.”

Lessons in determination

Frederic began developing knowledge of immigrants’ needs when she immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 17 from Cazale. Her mountain village, about 45 miles north of Port-au-Prince, is known for its Polish settlers.

Growing up, Frederic’s family instilled a love of education at a young age, she said. Her parents, Marie Charite Orelien and Joseph Orelien, sent her to strict schools in Port-au-Prince where failing a class meant expulsion. That level of rigor taught Frederic the importance of determination, a trait she would carry with her when she moved to Irvington in 1999.

In the working-class township, Haitians make up about 14.1% of Irvington’s 54,233 residents. From that established enclave, Frederic faced new challenges — chiefly, completing her education.

“My dad did not like the Irvington school system and he made me apply to the community college, despite having limited English,” Frederic said. “Because I had excelled in math and science in Haiti, I received strong grades in both of these fields.”

And despite the language barrier, Frederic became a math tutor by her second semester at Essex County College. She earned an associate’s degree in biology and two years later, Frederic graduated from Rutgers University with a bachelor’s in biology and chemistry.

Later, Frederic earned a master’s in health care administration from Seton Hall University, where she is now pursuing a doctorate in biochemistry. She began to use her scientific background to actively pursue making Irvington an environmentally-friendly city.

While working toward her advanced degrees, Frederic also married Joseph Betissan Frederic and gave birth to her only son Ben. She also learned to navigate life as an immigrant, including becoming fluent in English and accessing various systems, offices and information.

It was after attending the Center for Women and Politics at Rutgers University that Frederic learned more about local government and its impact on citizens’ day-to-day lives, especially those of immigrant backgrounds. She decided to run for a board of education seat, in 2009 and 2010. Frederic was unsuccessful then, but did not rule out another run in the future.

“A friend on the council”

In 2012, an opportunity opened on the city council, and Frederic successfully ran.

“I wanted to be the voice to help out other Haitians whose first stop was Irvington,” Frederic said. “I was able to change certain laws to give Haitian-Americans more opportunities and remind them that they have a friend on the council.”

Recently, when drivers with the Irvington Taxi Committee complained about insurance prices, Frederic helped amend an ordinance to lower their insurance rates. In the lead-up to the November elections, even though she was not on the ballot, Frederic encouraged the community to be civically engaged. She took to Haitian radio to instruct residents in Creole how to properly complete voting ballots.

“It’s so amazing when you can speak to someone in Creole and be able to use it to help others,” Frederic said. “It’s really important that we provide that kind of support by letting them know that it’s OK to feel welcome and it’s OK to speak Creole. [Being] able to connect with people is priceless.”

Through her eponymous nonprofit civic organization, Frederic also organizes a Haitian Independence Day celebration, brings Haitian-American artists to Irvington for Haitian Flag Day, and otherwise highlights the talent and creativity of Haitian-Americans.

“Anytime I’m holding an event, like a clothing drive, she is always there to support financially and brings other council members to our events,” said James Louis, who works with the Haitian-American Civic Association. “This is not just for me and the organization, but this is the testimony from everybody I’ve talked to within the community.”

Besides lifting up Haitian-Americans, Frederic has also focused on making Irvington part of the Sustainable Jersey program. In 2014, the city became bronze certified, a designation awarded to cities that implement sustainability measures, and she was named a Sustainability Hero.

Her current focus is on educating residents about the impact of lead paint on children and how to remediate such structures and promoting health and wellness in the township.

Balancing city council, her full-time job and a family can be overwhelming and she sometimes feels like giving up, Frederic said. But, remembering the residents in need renews her determination.

This article was originally published in The Haitian Times.

#Charnette Frederic#NJ#New Jersey#Irvington#politics#Haitian-American politicians#Haitian-Americans#Larisa Karr#The Haitian Times

1 note

·

View note

Text

Biden Win Met With Mix Of Relief, Coolness And Optimism For Haiti

President-elect Joe Biden speaks Wednesday, Nov. 4, 2020, in Wilmington, Delaware. (AP photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Democrat Joseph R. Biden’s victory won’t change much in Haiti, mired as the country is in economic inequality and political unrest, some observers say. Others, mostly policy experts, insist the new United States administration will have significant influence as Haiti moves forward — with an early, key test being how well Haiti carries out its own elections in 2021.

“There were [Democrats] in the past who were very close to Haiti, but that did not change the country’s situation,” said Phares Jerome, 41, a journalist based in Port-au-Prince. “It’s up to Haitians to fight for changes in the country’s situation, not an American president, whether he is a Democrat or a Republican.”

All agree that for better or worse, the decisions of the world’s preeminent superpower will certainly affect Haiti. Through both its rhetoric and actions, policy experts say, the incoming Biden administration’s responses to increased concern for human rights and changes in immigration policy could certainly distinguish itself from that of President Donald Trump.

The Biden transition team has not yet returned requests from comment. However, during the campaign, Biden’s campaign team released a list of priorities that included effective oversight of U.S. government funds to Haiti and working with the Haitian government to hold prompt elections. Protections for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) holders in the U.S. and a stop to deportations also made the list.

And, with Karine Jean-Pierre set to serve as chief of staff to Vice President-elect Kamala Harris, community members have said the U.S. will likely pay closer attention to Haiti.

Jean-Pierre told The Haitian Times in an Oct. 14 interview that Biden’s commitment to the Haitian community “is rooted in a fundamental belief in the unlimited potential of our community and ensuring that the Haitian people are treated with [the] respect and dignity that they deserve.”

Haitian voices on Biden’s victory

Haitian President Jovenel Mo��se joined most of the world’s leaders to congratulate Biden on his victory. Moïse said via Twitter, “The USA is an important ally for Haiti, and I look forward to continued cooperation with this friend.”

Other leaders also said they were breathing a sigh of relief because, unlike Trump’s personality-driven leadership, Biden has respect for institutions and the rule of law.

Haitian president Jovenel Moise addresses the nation.

Among regular Haitians, the view is that Haiti will not be any greater of a priority for the new administration than it has been for the current. That reality, they say, underscores why Haitians must rely on themselves to make the country better.

“I don’t think when Biden comes to power in January, he’s going to focus on Haiti’s issues first,” Jerome said. “The United States has many issues waiting for him.”

Port-au-Prince resident Peterson Cledanor, 24, said opportunities for change will depend on the relationship Biden’s administration forms with Haiti’s ruling party.

“Since Biden is a Democrat, there are some small things that might change, it will depend on how PHTK will negotiate with Joe Biden’s team,” Cledanor said.

Haiti’s PHTK is the political party that brought Moïse to power. It has been likened to Trump’s Republican party for some of its populist messaging and brash leadership style. The Haitian president, along with other Caribbean leaders, also made a trip to Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home that some saw as obsequious.

D’jerby Raphael, 25, criticized Haiti’s leadership for its subservience to the current president, particularly considering Trump’s disparaging remarks about Haiti.

“None of them rejected what Trump said or tried to put him in his place,” said Raphael, a Port-au-Prince resident and medical student.

Haiti elections as an early test

Affronts aside, all eyes are on the PHTK to see how it will run Haiti under Biden. After Haiti failed to hold parliamentary elections in 2019, Moïse has governed mostly through presidential decree.

François Pierre-Louis, a political science professor at Queens College in New York, said Moïse’s attacks on the judicial branch and propensity to rule by decree are similar to Trump’s governing style.

“The Haitian president is governing like how Trump wanted to govern in the States,” Pierre-Louis said.

Recently, the question of when to hold legislative elections has provided the backdrop to U.S.-Haiti relations. In October, the U.S. State Department encouraged Haiti to hold legislative elections no later than January 2021. Foreign governments have raised doubts about whether political and security conditions in Haiti can support legitimate elections. One issue further complicating matters is disagreement over whether Moïse’s term should end in 2021 or 2022.

If Haiti does hold fair legislative and presidential elections, Pierre-Louis said the PHTK party would not stand a chance, given its minimal popular support. Reducing the potential for violence by politically connected gangs is a key element in ensuring a fair process.

However, Haiti’s most powerful gangs often have the tacit support of corrupt police, Pierre-Louis said. Police who, under the Trump administration, saw U.S. financial support increase from $2.8 million to $12.4 million.

Election workers oversee ballot boxes during Haiti's 2015 elections.

“The way to cut down the violence is to stop these people from importing weapons to Haiti,” said Pierre-Louis, noting that Biden’s team can use its influence to restrict the flow of arms.

The Biden administration’s level of investment in fair elections will largely depend on how the administration balances its other domestic and foreign policy priorities, said Brian Concannon, executive director of the foreign policy advocacy group Project Blueprint. If the Obama administration, in which Biden served as vice president, is any indication, Concannon said he sees little reason for optimism when it comes to fair elections.

The flawed 2010 elections excluded major political parties and undermined confidence in the democratic process. Observers worry about similar consequences from a flawed 2021 election.

Concannon said he expects human rights groups to continue addressing police corruption.

“The Biden administration is going to listen to human rights groups in ways that the Trump administration has not,” Concannon said.

Uneven diplomacy under Trump to redress

The Trump administration and the Moïse government forged close ties.

During Moïse’s Mar-a-Lago visit, Trump agreed to explore U.S. investment opportunities in Haiti. Two months later, the U.S. government inked a $19.5 million deal for a hotel in Cap-Haitien, and officials touted the agreement as a job creator.

In other areas, Trump’s administration pulled back on diplomacy. In 2017, it removed the State Department office that helped oversee earthquake reconstruction. It also reduced support for the Caracol Industrial Park community development project meant to create housing and jobs after the 2010 earthquake.

“Once Trump came in, that wasn’t a priority,” Pierre-Louis said. “Hopefully diplomacy will come back with Biden, and the issues will be looked at more professionally.”

Pleasing the Haitian-American voter base

Stateside, the immigration policies Biden has outlined will affect Haiti. Keeping TPS intact for nearly 60,000 Haitians, a campaign promise to counter Trump’s efforts to end the program, will allow residents to continue supporting families in Haiti with their incomes.

Biden must also address the Haitian Family Reunification Program created under Obama that Trump ended.

“One easy fix is to reinstate this program and the Biden folks have already promised that they’re going to do this,” said Steven Forester, immigration policy coordinator at the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti.

Another measure the Trump administration instated is Title 42 expulsions, which enables authorities to deport people who have not gone through asylum or immigration processing.

With the advent of COVID-19, observers have feared that deportation of people who carry the coronavirus could be devastating for Haiti.

All these issues serve as a strong incentive for Biden’s administration to address, given the growing political power of the Haitian diaspora, if nothing else. This influence can be seen in the higher number of Haitian-American elected officials and Biden giving senior-level posts to Jean-Pierre and the Florida Senior Campaign Advisor Karen Andre, Pierre-Louis said.

“We have a lot of elected officials, we have Haitians becoming U.S. citizens in a lot of places,” Pierre-Louis said. “They can make a difference in who gets elected.”

This article, which was co-written with Sam Bojarski and Onz Chery, was originally published in The Haitian Times.

#Haiti#United States#foreign policy#US election#Haitian elections#Joe Biden#Jovenel Moise#2020#Sam Bojarski#Onz Chery#Larisa Karr#The Haitian Times

0 notes

Text

Results Roundup for Haitian-Americans in 2020 State and Local Races

Scores of Haitian-American candidates were on ballots across the country to represent their communities, mostly in Florida and New York. Here are the results of their elections.

FLORIDA

State Legislature Races

Dotie Joseph, Florida House District 108 (WON)

Joseph ran unopposed for her 108th District in Miami-Dade County.

This is her second term in the Florida House of Representatives, where she serves on the Energy & Utilities, Higher Education Appropriations, Collective Bargaining, and Local Administration Subcommittees.

Marie Woodson, Florida House District 101 (WON)

Woodson ran against Republican Vincent Parlatore for the 101st District in Southeast Broward County. She won by 74.1% (51,160) compared to Parlatore’s 25.9% (17,912).

This will be Woodson’s first term in the Florida House of Representatives. Prior to running for office, the Port-de-Paix, Haiti native worked as a public administrator for Miami-Dade County for over 30 years, retiring in 2018.

Nancy St. Clair, Florida House District 92 (LOST)

St. Clair, who ran nonpartisan, lost to Democrat Patricia Hawkins-Williams for the 92nd House District representing Northeast Broward County. Hawkins-Williams received 81.2% of the vote (49,439) , while St. Clair garnered 18.8% (11,474).

St. Clair is currently in law school at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale.

Local Races

Gepsie Metellus, Miami-Dade County Commission (LOST)

Metellus ran non-partisan for County Commissioner in Miami-Dade’s District 3, losing to Keon Hardemon, who ran non-partisan as well. Metellus received 33.2% of the vote (21,732), compared to Hardemon’s 66.8% (43,674 votes).

She is the co-founder and executive director of Sant La Neighborhood Center, a social service organization serving Haitian immigrants in South Florida.

Linda Julien, Miami Gardens Council (WON)

Julien ran non-partisan for Seat 5 on the Miami Gardens City Council. She received 33.6% of the vote (250), compared to incumbent Andre Williams, who received 24.19% (180 votes).

She is the Economic Development Manager for the City of North Miami.

Nadia Assad, Lauderhill Commissioner (LOST)

Assad finished last in the race for the Seat 3 Commissioner in the city of Lauderhill. She received 27.7% of the vote (7,792), compared to Ray Martin’s 38.5% (10,824 votes) and Kelly Davis’ 33.9% (9,534 votes).

She works as an administration assistant for the City of Fort Lauderdale.

Nancy Metayer, Coral Springs Commissioner (WON)

Metayer ran non-partisan for District 3 of the Coral Springs City Commission, beating five other candidates to win 32% of the vote (19,149).

A Coral Springs resident for over 20 years, she works as a statewide coalition manager for NEO Philanthropy, a nonprofit organization focusing on social justice movements.

Daniela Jean (WON), Ketley Joachim (LOST) and Raphael Dube (LOST), North Miami Beach Commissioner

Jean, an author and risk management specialist for the City of North Miami, won 34% of the vote (4,968) for Seat 3 of the North Miami City Commission.

Joachim, a community advocate residing in North Miami Beach, won 14% (2,068). Dube, a mortgage loan originator, finished with 12% of the vote(1,836).

NEW YORK

Congressional Race

Constantin Jean-Pierre, 9th Congressional District (LOST)

Republican Jean-Pierre lost to Yvette Clarke, who has served in the position since 2013. Jean-Pierre received 17.6% (36,847 votes) to Clarke’s 81.5% (170,898 votes). Overall, 209,962 votes were cast in the Brooklyn district.

He has worked for the New York City Department of Correction, as well as coaching youth sports.

State Legislature Race

Kimberly Jean-Pierre, New York State Assembly District 11 (WON)

Jean-Pierre, a Democrat, successfully won a 4th term representing New York State’s Assembly District 11 in Suffolk County. She received 55% of the vote (22,094). Her Republican challenger, Eugene Murray, received 45% (18,107).

Jean-Pierre chairs the Subcommittee on Banking in Underserved Communities.

Michaelle C. Solages, New York State Assembly District 22 (WON)

Solages, a Democrat, will be entering her fifth term as Assembly Member representing District 22 in Nassau County. She received 65.8% of the vote (33,747). Her Republican challenger Nicholas Zacchea received 34.2% (17,546) of ballots cast in the race.

In the Assembly, Solages chairs the Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus.

Clyde Vanel, New York State Assembly District 33 (WON)

Vanel, who ran unopposed, will be serving his third term in the state assembly representing District 33 in southeast Queens. He received 97.67% of ballots cast.

Vanel currently chairs the Subcommittee on Internet and New Technology in the Assembly.

Rodneyse Bichotte, New York State Assembly District 42 (WON)

Bichotte, who has been serving in the New York State Assembly since 2015, ran unopposed for District 42 in Central Brooklyn. She received 97.25% of ballots cast.

She chairs the Subcommittee on the Oversight of Minority and Women-Owned Businesses (MWBE) in the State Assembly.

Mathylde Frontus, New York State Assembly District 46 (LOST)

Frontus, the Democratic incumbent, lost to Republican Mark Szuszkiewicz for Assembly District 46 in south Brooklyn. She received 45.7% of the vote (15,030), compared to Szuszkiewicz’s 54.3% (17,852).

Prior to serving in the Assembly, Frontus was the executive director of Urban Neighborhood Services, a social service organization in Coney Island providing services for youth.

Phara Souffrant Forrest, New York State Assembly District 57 (WON)

Forrest beat incumbent Walter T. Mosley for District 57, which covers the areas of Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, and Prospect Heights in Brooklyn. She won 74.4% of the vote (31,857), compared to Mosley’s 25.6% (10,973 votes).

She is a nurse, tenant activist and a member of the Democratic Socialists of America.

This roundup was originally published in The Haitian Times.

#2020 Elections#Florida Haitians#Haitian-Americans In Politics#Haitian-American Candidates#New York Haitians#The Haitian Times#Larisa Karr#list#US elections

0 notes

Text

New Jersey Haitians plan for possibly hectic Nov. 3

Kareen Delice-Kircher (right) stands with County Clerk Christine Hanlon (center) and other community members at a 2016 voter registration drive in Monmouth County, NJ. Photo courtesy of Kareen Delice-Kircher.

While early voting lines stretch around blocks in New York City this week, across the river in New Jersey, some residents can only wish they had the option of voting early in person too. Instead, New Jerseyans can either vote by mail or appear in person on Election Day.

The absence of early voting has left many Haitian-Americans wondering about congestion at the polls, the heightened risk of contracting COVID-19, and how senior citizens will manage long waits.

“I’m really concerned for the elderly and people with disabilities who won’t be able to stand in line for too long because of different pains they may have,” said Arianni Pierre, a graduate student at Rutgers University. “I have two elderly parents and I can’t see them standing in line for 30 minutes, let alone [for] four hours.”

About 40,850 Haitian-Americans live in New Jersey, according to the U.S. Census, with most living in or near East Orange, Irvington and Paterson.

Since in-person early voting is not available, many community members pushed for voting by mail instead, where the voters mail their completed ballots back to officials. Haitian radio stations, social media forums and church leaders heavily encouraged Haitian-Americans to vote by mail. Local community members created videos in English and Creole to explain how vote-by-mail works.

Pierre, an East Orange resident, said she was hoping to vote by mail, but has yet to receive her ballot. On Election Day, Pierre will instead go to the poll site with her brothers, who will stand in line with her on behalf of their parents. When their turn arrives, the brothers will call their parents to come vote with them.

Woody Philippe, executive director of Jefferson Park Ministries, a social services organization in Elizabeth, said he and his family have voted by mail already. However, knowing there is a need, he plans to drive voters who need rides to the polls on Election Day.

Because the state successfully urged people to vote by mail in the primary and fewer people are out due to COVID-19, congestion at the polls may not be an issue, Philippe said. Having police and poll workers available to make sure people follow social distancing should also help.

People who need help with voting can also get in-person and over-the-phone assistance on Election Day, Philippe said.

Haitian-Americans in Monmouth County have been receiving information on voting issues through 88.1 FM, Good News Radio. Ebenezer Church of God of Prophecy in Neptune City will be providing transportation to voting sites on Nov. 3.

Still, others worry that there will be those flouting the rules and congestion will be an issue.

“Some people are comfortable with masks and other people are not comfortable with masks,” said Rodney Jean, a fashion designer in East Windsor. “It’s very divided and nobody wants to listen to anyone.”

Jean plans to take the day off from work to vote in person. He said having the option to vote early in person would be better than New Jersey’s current system.

For Pierre, of East Orange, the concern is how the state will safeguard people from COVID-19 and how those measures might affect wait time. She wonders whether they will turn off and sanitize the booths after each person votes. Her East Orange polling location, the lobby of a small church, only has two voting machines, so a 30-second task can turn into two minutes.

Kareen Delice-Kircher, CEO of a technology consulting firm, plans to drop off her ballot at the County Clerk’s office. She is among those who prefer not to mail back their ballots.

“If Haitian people had the option to vote early, this would give us more confidence in the process because you’d know you [voted] in-person,” said Delice-Kircher, a Howell resident. “You know for sure with your own two eyes that you did it.”

While the extra planning does not seem to have dampened enthusiasm, the overwhelming sense is that the state really should have made early in-person voting an option.

“With COVID-19, you have a lot of graduate students and professionals who are home,” Phillippe said. “They’re going to resonate better with early voting. They’re going to act early because they’re feeling the pain of what’s going on, and they want a change.”

This article was originally published in The Haitian Times.

#New Jersey#Garden State#voting#vote-by-mail#elections#US politics#Election 2020#Haitian-Americans#Larisa Karr#The Haitian Times

0 notes

Text

Haitians in smaller states highly engaged in elections, despite lack of data

Bianca Shinn-Desras walks door-to-door in Stamford, CT educating her community on the importance of voting. Photo courtesy of Bianca Shinn-Desras.

By Larisa Karr

As Nov. 3 fast approaches, Connecticut resident Bianca Shinn-Desras is doing everything she can to galvanize the state’s Haitian-American community. Taking a boots-on-the-ground approach, Shinn-Desras and other volunteers are knocking on doors in the state’s small Haitian enclaves to provide information on how to vote, combating misinformation on Facebook and WhatsApp and working with pastors to deliver useful updates to their congregations.

“Connecticut is one of 10 states in the U.S. that has a large Haitian population,” said Shinn-Desras, who lives in Stamford. “It’s often neglected because it’s not Florida or New York, but it is in that corridor — between New York, Massachusetts and the Northeast — and that’s powerful.”

At an estimated 20,000, Haitian-Americans in the Constitution State are small in number compared to New York and Florida. Still, as with other states where they are not as visible a voting bloc as New York and Florida, Connecticut’s dynamic Haitian-American residents are intensely involved in turning out the vote in their communities.

Without accurate, easily accessible data to support their participation, however, numerous advocates and academics have said, the community will miss out on resources it is due. Census data, they say, is only a starting point and doesn’t reflect the actual, larger figures. Nor do local institutions.

The lack of data has left many, like Shinn-Desras, who is an associate data strategist for a non-profit, calling for a deeper level of detail about voters.

“This is inequity in data collection,” said Shinn-Desras, 39. “You have a population that you’re not gaining information about, not providing open data, and it’s a problematic practice.”

Feeling invisible

Statistics from election boards in nine states with large Haitian populations, as well as official numbers by the U.S. Census Bureau, do not reflect the visible political participation of Haitian-American communities across the country. The majority of local and statewide election boards only record voter statistics by race, not by ancestry or ethnicity.

In politically active Connecticut, the state only provides a voter’s gender.

The absence of data on Haitian-American voters feels as though Connecticut is treating them like a forgotten population, Shinn-Desras said. Were these statistics to become available, she would use them in promoting political discourse and engagement throughout her community.

Shinn-Desras visits homes in the small Haitian enclaves of Connecticut’s third-largest city. Photo courtesy of Bianca Shinn-Desras.

“In the future, we definitely have to be able to capture the data because, while we are Black Americans, our ethnicity is still very important,” Shinn-Desras said. “We need to be able to capture that and I think by not having that, we’re losing momentum.”

Others say different generations participate in politics in their own way, making the need for data a necessity to guide effective voter outreach toward each group. The methods used across generations, for one, could be adjusted with the appropriate data to support outreach.

“There is the question of transnational identity, where many Haitian immigrants continue to remain focused on Haiti and not on the realities in America,” said Georges Fouron, a professor at SUNY Stony Brook who has written about Haitian political participation in the United States. “This is not the case with the second and third generation. I’m not basing my hope on the immigrants themselves, but instead on the children and grandchildren.”

Increased visibility and participation

Despite feeling overlooked, many Haitian-Americans actively work to influence voter turnout by mobilizing the community here and even by working through loved ones in Haiti.

In South Carolina, with an estimated 1,106 Haitians, Patrick Gue is currently in the process of helping to form an association, tentatively known as the American Haitian Organization, to start combining political participation efforts by individual Haitians.

“Our Haitian community has to continue to call each other in our state and in our country to motivate us to vote,” said Gue, a Greenville County pastor. “We are even calling people in Haiti to reach out to their friends and family who are U.S. citizens to encourage them to vote.”

In Georgia, which has a Haitian-American community of 30,763, Haitian-Americans were intensely focused on completing the Census as one way to build cohesion across the state.

“We’re engaging with voters by ensuring that we can count them,” said Saurel Quettan of the Georgia Haitian-American Chamber of Commerce.

With people living in the exurbs, the lengthy commutes make uniting the community a challenge, Quettan said. Nonetheless, the Atlanta resident said, he is optimistic about the growing level of Haitian-American political engagement.

An increasing number of Haitian-Americans are beginning to run for office as commissioners and mayors in small cities he said. And recently, community members walked to a polling site to encourage participation in the elections.

Such increased visibility is part of the solution to be recognized as a significant voting bloc.

“We need to [focus] on ourselves here and encourage each other to vote, so we can continue to participate in the political arena,” said Gue, a Cap-Haïtien native. “If we are organized and start to do things in the community, politicians will see that and come to us.”

This article was originally published in The Haitian Times.

#us politics#politics#voting#2020 election#Haitian-Americans#Connecticut#south carolina#Georgia#United States#The Haitian Times#Larisa Karr

0 notes

Text

Older Haitian-Americans Eager To Vote Lean On Family, Poll Workers For Help

A Creole flyer created by the Brooklyn Voters Alliance encourages people to vote in the upcoming election.

By Larisa Karr

Bienne Domand, a retired certified nursing assistant in Stamford, Connecticut, has not missed voting in a presidential election since she became a U.S. citizen in 2003. But while the 62-year-old grandmother of eight is always sure of her choice for president, she often leaves the rest of the ballot blank.

“When I don’t understand the ballot information or get confused, I go to the poll workers and say, ‘Can you point to the Democrat, the Blue one?’” Domand said. “I just want to know who they are and that’s all I need to know.”

Older Haitians, from the baby-boomer generation in their 60s and above, are among the most attuned to U.S. politics. For many, who fled Duvalier-era bloody elections that caused them not to discuss politics openly for fear of reprisal or death, being able to discuss and participate in U.S. elections is a civic duty they fill faithfully.

However, older Haitian-Americans struggle with several unique barriers when it comes to casting their ballots. Language translation is consistently viewed as the biggest obstacle hindering these senior citizens from fully participating. Other issues include information inundation, the layout of the ballot and, this year in particular, adjustments made to the voting process due to COVID-19.

As a result, with Nov. 3 rapidly approaching, Haitian-Americans are more attuned to the needs of senior community members whose votes are so crucial. Translating ballots into Creole is not enough, community members say. They also need support with the logistics of the process and to have clear explanations of items beyond the presidential nominees, such as the state and local races and legislative amendments.

Even in Florida, which has extensive language translation assistance, there are smaller logistics of voting that activists say older Haitian-Americans need to know.

“Miami-Dade County has workers providing language assistance at the polls, but it’s tricky because they will only know that you need language assistance if you check a box when you register,” said Léonie Hermantin, Director of Communications at Sant La Neighborhood Center. “Even though it’s in Creole, people who have literacy and language issues overlook that little box in the corner, which is barely visible.”

Help with language and logistics

Many are taking steps to provide direct and simple translations to help older voters successfully cast their ballots.

“We’re giving election information to the elderly Haitian community in plain Creole and we’re really keeping it as simple as possible,” said Stanley Neron, a community advocate in Elizabeth, New Jersey. “You don’t want to utilize the original linguistics of the ballot because it will get too complicated and you will lose them.”

Stanley Neron works with churches in Elizabeth, NJ to help older Haitian-Americans learn how to vote. Photo courtesy of Stanley Neron.

Neron and others are working extensively with the faith-based community in Elizabeth by creating videos in Creole and sharing it with pastors of different churches. The videos contain information on how to place and seal the ballots into envelopes, where to put names and addresses, and the importance of returning ballots earlier than the day of the election.

“With this election, we definitely have more people registered to vote than four years ago but they have no understanding of what the ballot means,” said Sheenaider Guillaume, a Linden, New Jersey resident. “What we’ve especially come across is that they don’t understand there’s a backside to the ballot and they don’t understand who to vote for outside of the presidential election.”

If older voters do not fully understand the process or properly complete ballots, their lack of participation could negatively affect Haitian-Americans as a bloc.

Jan Combopiano, senior policy director at the Brooklyn Voters Alliance, said this is why organizations such as the New York City Board of Elections must do more to improve language access. She said the state needs to implement legislation and allocate more money to provide voting resources in languages besides English.

“We want people to make informed choices when they vote and language should not be a barrier to people voting,” Combopiano said. “Any time anyone gets dissuaded because there’s no one to help them, this might mean they’re not going to vote in the future and they could be sending a message to the rest of the people in their family that voting is not important.”

In battleground Florida, Haitian-American politicians and advocates are proactively working to ensure the older population gets the help they need before the election.

Dotie Joseph, a Florida House of Representatives member whose 108th District is heavily Haitian, has been explaining on Haitian radio what the ballot amendments are and answering questions about them from Haitian-Americans in Creole.

“The ballot amendments and voter education are necessary across the board and it’s even more pronounced in any immigrant community, especially when there’s a language barrier,” Joseph said. “In addition to this language barrier, a lot of these folks are just intimidated by the whole voting process and they need somebody there to assist them.”

Help from family and friends

Some Haitian-Americans see their older family members struggling with a mountain of election-related mail and have become concerned about information overload on their behalf.

“My parents receive so many requests for mail-in ballots and are being flooded with information,” said Lana Joseph, an Atlanta-based attorney.

Joseph’s 74-year-old mom speaks only Creole, while her dad, who is 78, speaks English but needs assistance with complex topics. When Joseph recently visited them in Stone Mountain, Georgia, she explained to them that the mail they had received was not a ballot, but a form to request a ballot. After they successfully received their ballots, she sat down with them and had a conversation about the candidates and the issues so they could fully understand.

Joseph said that if older Haitian-Americans do not have family members who can assist them with understanding how to vote, they might not even try to seek help.

And with COVID-19 curtailing opportunities to socialize, some older Haitian-Americans may put the election on the backburner.

“We are not able to see them face-to-face anymore at events and if they have family members who are not at home helping them, it is even more frustrating than before,” said Joseph, 41. “They cry out for help, but we might not be able to get to them because they’re in their home.”

For Domand, the Connecticut septuagenarian, the best way to ensure she is able to cast her ballot is by voting in-person. This year, she said she plans to have her son go to the poll with her because she wants her vote to count.

“There’s anxiety around this election because they’re hoping that their votes count, that people are not stealing the ballots or discrediting the ballots,” said Domand. “I can’t wait to go in person and vote Democrat.”

This article was originally published in The Haitian Times.

#2020#Elections 2020#US politics#politics#voting#elderly voters#Haitian-Americans#Connecticut#Florida#New York#New Jersey#Georgia#The Haitian Times#Larisa Karr

0 notes

Text

Academics, strategists track down Haitian-American voting data to turn Florida Blue

Democratic presidential candidate former Vice President Joe Biden spoke at the Little Haiti Cultural Complex in Miami on Oct. 5, 2020. Photo: Andrew Harnik/Associated Press

By Larisa Karr

When Democratic Party presidential nominee Joe Biden visited Little Haiti two weeks ago, he said Haitian-Americans could turn the state Blue. It appears his party has the data to prove it.

Data that has informed much of the get-out-the-vote efforts undertaken by Democratic party workers, volunteers and community advocates to reach Haitian-Americans — in person and virtually. Having the details, proponents of the approach said, better informs efforts to engage the community and, more importantly, shows the growing clout of Haitian-Americans in Florida.

“In official statistics, it’s important to delineate what separates Haitians from other groups they are categorized with, like Jamaicans and Black Americans,” said Santra Denis, president and founder of the South Florida-based organization Avanse Ansanm. “People typically think about the Black community as very monolithic and for Haitian-Americans, there’s a cultural need in terms of how you relate to us, what resonates with us, and what will pull us into this political cycle.”

Official voting statistics do not specify American citizens with Haitian parents or naturalized Haitian-Americans born in other countries. However, academics surfaced the data by cross-referencing official voting data with the population’s ethnicity and background. Democratic strategists then took it further by adding their analysis, based on knowledge of the community, to come up with recommendations to turn Florida Blue.

With the final weeks of the campaign in full swing, the current approach observed is largely based on a report by Herlande Rosemond, voter protection deputy director for the Florida Democratic Party.

In the report, titled “Florida’s Haitian American Community,” Rosemond said the state’s 300,563 electors of Haitian ancestry are significant and need to be better utilized. She drew a contrast with the Venezuelan population, a group that receives much attention, whose population is less than half the number of Haitian-Americans in the Sunshine State.

“Just possibly, the road to the White House might run through Little Haiti,” the report states.

Rosemond did not return messages seeking comment for this story. However, many of the actions taken by the Biden-Harris campaign follow the report’s recommendations, including a Haitian radio ad blitz, commercials in Creole, and the visit to Little Haiti.

“The road to the White House certainly runs through Florida and our campaign is working tirelessly to mobilize and turn out the Haitian-American community for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, especially as Floridians are early voting,” said Karen Andre, senior adviser to Biden’s Florida campaign. “We plan to continue our work to win their support in everything, from our organizing efforts to our paid media program, through Election Day.”

Wall mural in Little Haiti in Miami, Florida, United States. Photo by Marc Averette.

Linking voter data to country of origin

The voter data behind the strategy is based on the work of such academics at the University of Florida — Daniel Smith, chair of the Department of Political Science, and Sharon Austin, a political science professor and director of the African American Studies Program.

Smith has coded about 14 million lines of data that show a person’s national origin in order to locate their birthplace and the precincts in which they voted. The extensive, months-long task entailed working with a team of students to merge voter precinct data with individual voter files from the state, Smith said.

Also, with Haiti spelled a multitude of different ways in the data and some people listing their country’s hometown as a place of origin, Smith’s team took educated guesses about the country of origin.

“It takes a lot of heft to do an analysis of voter participation by country of origin,” Smith said. “The state could presumably do all this, but they don’t. They will make it publicly available to show the voter breakdown by party, but other than that, they aren’t providing any information.”

Among the findings in his research is that Haitian political participation in Florida is strong and higher than the statewide average, said Smith. Haitian voter turnout in the 2018 general election was 73 percent, compared to the state’s 64 percent overall. The 2016 levels were similar.

Austin, whose work centers on the Black vote, said the data-driven approach that she and Smith have pursued has made people realize the power of Florida’s Haitian-American voters.

“These numbers allow you to understand that Haitians vote at higher levels, that there is a large Haitian population in Florida, that there are a number of Haitians who have ran for office and won office, and that as a political group, they really have arrived,” Austin said.

One reason Haitian voter turnout has been so high is the community’s strong sense of cultural identity and this identity is vital to tap into for expanding political representation in official statistics, he said. Smith also emphasized robust field campaigning and door-to-door canvassing as instrumental to maintaining strong enthusiasm for political participation.

Now that the first generation of Haitian immigrants has laid the bedrock, the community should continue to strengthen its political progress moving forward, community advocates say.

“The generation before us spent a lot of time making sure the foundation was where it needed to be so that we can have a strong and vibrant community,” said Denis, of Fort Lauderdale.

Top to Bottom: Karen Andre, senior advisor to Democrat Joe Biden’s Florida campaign; Karine Jean-Pierre, chief of staff to Democratic vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris; and Santra Denis of Avanse Ansanm advocacy group in Florida.

Direct, culturally appropriate outreach

Rosemond’s report also outlines ways the Democratic Party could address shortcomings.

“It is necessary to include the Haitian community as important members of the overall Florida Democratic Party,” Rosemond wrote. “What this means is to address the language and cultural idiosyncrasies of this population, recognizing and utilizing members of that community in the ‘get out to vote’ movement.

Biden’s campaign has been doing just that.

In contrast to Trump’s campaign, his team has placed a strong emphasis on reaching out to Florida’s Haitian-American population. In addition to Andre, Karine Jean-Pierre was named as Kamala Harris’ chief of staff.

The Biden-Harris campaign has launched a six-figure media blitz airing television and radio ads in Haitian Creole. Both Andre and Jean-Pierre have asked for the community’s support, all English, French and Creole, in media interviews, virtual events and community forums.

This week, both Joe Biden and Kamala Harris traveled to Florida with the intent of drumming up support among Caribbean voters.

Rosemond also recommended having a strong field organization that is culturally appropriate, similar to the boots-on-the-ground approach championed by Denis and Smith, for the Biden-Harris team to turn Florida Blue.

She said the party should reach out to Haitian-Americans in Creole, citing Florida Representative Dotie Joseph’s prior use of language as among the most important factors playing into Haitian-American political participation. Joseph’s 108th House District has electors who speak Spanish, Haitian Creole and English. She has conducted events in each language to reach specific electorates.

Waiting for results

Smith said Biden is taking the right steps to energize Haitian-American voters for two reasons.

“I fully expect stronger support for Biden because of Trump’s disrespect for Haiti, which he has made very clear and obvious,” he said. “I also think that Biden has been able to distance himself from Hillary Clinton, who brought a lot of concern to the Haitian-American community.”

Another significant component is direct engagement outreach, including knocking on doors and passing out literature, and connecting with Haitian-American millennials in particular.

For National Voter Registration Day on Sept. 22, nonprofit organization Avanse Ansanm partnered with one of the busiest Haitian bakeries in Broward County. Denis, its leader, paid for people’s orders in exchange for her to check their voter status on the spot.

With such activity underway, Denis is optimistic that more politicians like Joseph will be involved in Florida’s political landscape, which could eventually pave the way for greater representation in elected positions.

Consequently, with greater representation, Haitian-American politicians will continue to advocate for and generate political enthusiasm within their own community.

“We’re going to start to see a lot more Haitian elected officials as state and city commissioners, superintendents, and as members of Congress,” Denis said. “We’re involved in every aspect of life and we should have political representation as well.”

#Election 2020#Florida#Haitian-Americans#voting#Democratic Party#Joe Biden#Kamala Harris#US politics#politics#Larisa Karr#The Haitian Times

0 notes

Text

Trump, missing-in-action with Haitians, still draws handful of supporters

President Donald Trump last campaigned in Little Haiti as a candidate in September 2016, when he pledged to be the “greatest champion” of Haitian-Americans voters.

Now — with a slew of opinion polls showing Trump trailing in most states, after calling Haiti a “s–thole” and issuing controversial immigration orders, and with his COVID-19 diagnosis grounding his travel plans — it appears doubtful Trump will make any substantial overtures to Haitian-American voters.

Still, a handful of Haitian-Americans say they will support the president. Calling on religion and family values as their key reasons to vote, these conservative movement supporters also bring up the Democrats taking Black voters for granted, esoteric footage from decades ago, and debunked fringe theories to explain their presidential pick.

For Sendra Dorcé, who runs a “Haitians for Trump” Facebook page, her main reason for supporting Trump is what she calls the Democrats’ failed strategy to help rebuild Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

“If you care about Haiti, think about the earthquake in 2010 and ask if Biden can tell us where those $10 billion are,” Dorcé said. “How do you vote for a party that hijacked $10 billion from Haiti when the Haitian people barely have a place to live and food to eat?”

In an opinion letter submitted to The Haitian Times, Haitian For Trump chair Madgie Nicolas said Democrats are simply pandering to minorities.

“Biden is the walking embodiment of the betrayal, manipulation, misused and abused, empty promises of the Democratic party toward communities of color,” said Nicolas, who also works with Black Voices for Trump. “Our skin color is all he sees and then he will drop us after the election just like Democrats always do.”

The Trump campaign did not return messages seeking comment for this article.

Trump’s record on Haitians, Haitian-Americans

As a candidate, Trump did not appeal much to Haitian-Americans to begin with because they tend to vote Demoractic.

As the president, Trump downright alienated the community after he called Haiti a “s–hole country.” He was discussing U.S. immigration policy in January 2018 when he made the remark, adding that he wanted the U.S. to accept more people from countries like Norway.

In August 2019, the Trump administration ended the Haitian Family Reunification Program, which allowed Haitians to join family members in the U.S. waiting for a green card.

In 2020, between February and June, roughly 350 flights traveled to Latin America and the Caribbean to deport people, the research firm CEPR found. Haitian deportees were among those on the flights, and many among them tested positive for COVID-19 upon disembarking in Port-au-Prince.

Dieufort Fleurissaint, a pastor with Haitian-Americans United in Boston, is among those left reeling by Trump’s actions.

“He betrayed us when he implemented so many adverse measures, to the detriment of our families here with the massive deportation that we have seen since the beginning of the year, despite COVID-19,” Fleurissant said. “Haitians had hoped that he would not only keep TPS in place, but provide a path for TPS holders to eventually receive permanent residency.”

A tale of two campaigns

With the election heating up, Haitian-American support for Trump lies mainly with two groups active on social media: Haitians for Trump and Black Voices for Trump.

Dorcé, an advisory firm owner, highlighted the Trump campaign’s efforts in Haitian churches as a key part of recent outreach to the Haitian-American community.

“Lara Trump was just in Miami and they had a gathering with pastors from Haiti, New York, and Miami,” said Dorcé, referring to Trump’s daughter-in-law and adviser. “That’s how they’re trying to reach the community, because they know that Haitians are very religious and it’s through the church medium that they can access the most Haitian voters.”

On the Democrat side, Biden’s campaign launched a voter engagement campaign and six-figure media blitz targeting Haitian-Americans, particularly those in battleground Florida. They rolled out Ayisyen Pou Biden, Creole for “Haitians for Biden,” and organized appearances featuring the two most senior Haitian-Americans on his campaign.

On Monday, Biden visited Little Haiti in Miami. He promised to give Haitians an “event shot” and urged them to vote Democratic because their numbers can swing the election his way.

Ahead of Biden’s visit, the campaign released a list of top priorities to address U.S. foreign policy toward Haiti, immigration and other domestic issues important to Haitian-Americans.

“The policies are also rooted in ensuring that Haitians are treated with dignity and have a fair shot at the American dream,” said Karen Andre, senior advisor to Biden’s Florida Campaign. “They are part of the fabric of America, and it’s our job to hear them and make sure that their priorities are reflected in our policies.”

This article, co-written with Sam Bojarski, was originally published in The Haitian Times.

#Donald Trump#Election 2020#US politics#politics#Haitian-Americans#Joe Biden#Republican Party#Democratic Party#Larisa Karr#Sam Bojarski#The Haitian Times

0 notes

Text

Election 2020: Roundup of Haitian-American candidates

Photo by Diliff, design by Leonardo March.

Ahead of Nov. 3, an unprecedented number of voters will cast ballots weeks earlier due to the the Coronavirus pandemic. As they choose a president, many voters in the two states with the largest Haitian-American populations ‒ Florida and New York ‒ will also see Haitian-American candidates on their ballots.

With more than 425,000 Haitian-Americans in Florida and 200,000 in New York, according to the Census Bureau and community organizations, civic engagement is on full display. In addition to voting, at least 17 candidates from Haitian-American communities are seeking to represent constituents at the municipal, state, and federal levels.

Here is a roundup of notable Haitian-American candidates who may appear on your ballot, depending on where you live. The list is in order of office ranking.

Note: This roundup will be updated periodically ahead of the Nov. 3 election. To include a Haitian-American candidate in your city, county or state, email [email protected].

FLORIDA

Dotie Joseph, Florida House District 108

Joseph, a Democrat, is running to represent Florida House District 108 (Miami-Dade County) in the Nov. 3 election. She does not have a Republican challenger.

Joseph is running for her second term in the Florida House, where she serves on the Energy & Utilities, Higher Education Appropriations, Collective Bargaining and Local Administration subcommittees.

About 125,000 Haitians live in Miami-Dade County, according to data gathered by the Sant La Haitian Neighborhood Center.

Marie Woodson, Florida House District 101

Woodson, a Democrat, is running to represent Florida House District 101 (southeast Broward County). She faces Republican challenger Vincent Parlatore.

Woodson is seeking her first term in office after winning the Democratic primary in August. She spent more than three decades as a public administrator for Miami-Dade County before retiring in 2018. Read her profile here.

About 111,000 Haitians live in Broward County, the Sant La center has reported.

Nancy St. Clair, Florida House District 92

St. Clair is running as an independent candidate to represent Florida House District 92 (northeast Broward County). She faces incumbent Rep. Patricia Hawkins-Williams, a Democrat. St. Clair works in the legal industry and is pursuing a law degree at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale.

Gepsie Metellus, Miami-Dade County Commission

Metellus is running to represent District 3 on the Miami-Dade County Commission in a non-partisan race. She earned enough votes in the August primary to force a runoff election with current Commissioner Keon Hardemon in November.

Metellus is co-founder and executive director of the Sant La Haitian Neighborhood Center, a social services organization that serves Haitian immigrants in South Florida.

District 3 encompasses multiple Miami neighborhoods, including Little Haiti. Read more about Metellus and her candidacy here.

Linda Julien, Miami Gardens Council

Julien is running for Miami Gardens City Council, Seat 5, a non-partisan position. After garnering the second-most votes in the August primary, she faces incumbent Councilmember Andre Williams in a Nov. 3 runoff election.

A native of Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood, Julien currently serves as economic development manager for the City of North Miami.

Per 2010 Census Bureau estimates, more than 9,100 Haitians live in Miami Gardens.

Nadia Assad, Lauderhill Commissioner

Assad seeks a position as a commissioner for the City of Lauderhill, Seat 3. She will run in a nonpartisan race against two other candidates, Kelly Davis and Ray Martin.

A community advocate, Assad works as an administration assistant for the City of Fort Lauderdale.

Lauderhill has about 8,600 Haitian residents, according to the Census Bureau’s 2010 figures.

Nancy Metayer, Coral Springs Commissioner

Metayer is a candidate for Coral Springs City Commission District 3, a non-partisan position. She will face five opponents on Nov. 3: Randal Cutter, Noor Fawzy, Andy Kasten, Jose Morera and Abel Pena.

Metayer has resided in Coral Springs for more than 20 years and works as a statewide coalition manager for NEO Philanthropy, a nonprofit dedicated to building social justice movements.

Coral Springs contains nearly 5,000 Haitian residents per 2010 Census Bureau estimates.

Ketley Joachim, Henry Raphael Dube and Daniela Jean, North Miami Beach Commissioner

Ketley Joachim, Henry Raphael Dube and Daniela Jean are all running in a non-partisan race for City of North Miami Beach Commissioner, Seat 3. They face each other as well as opponents Ruth Abeckjerr, Margaret Love and Dianne Weis Raulson on Nov. 3.

More than 9,800 Haitians live in North Miami Beach, according to the Census Bureau. Joachim, a native of Cap-Haitien, Haiti, has resided in North Miami Beach since 1995, where she has earned a reputation as a community advocate.

Dube currently works as a mortgage loan originator for Florida Preferred Mortgage, according to his social media pages.

Jean is a published author who also works as a risk management specialist for the neighboring City of North Miami.

NEW YORK

Constantin Jean-Pierre, 9th Congressional District

Jean-Pierre, a Republican, is running to represent New York’s 9th Congressional District (Brooklyn) in the Nov. 3 election. He faces incumbent Rep. Yvette Clarke, a Democrat, who has represented the district since 2013.

Jean-Pierre has worked for the New York City Department of Correction and coaches youth sports in the community.

More than 90,000 Haitian-Americans reside in Brooklyn.

Kimberly Jean-Pierre, Assembly District 11

Jean-Pierre, a Democrat, is running to represent District 11 (Suffolk County) in the state assembly. She faces Republican opponent Eugene Murray on Nov. 3. Jean-Pierre is serving in her third term as an assembly member.

In the assembly, she chairs the Subcommittee on Banking in Underserved Communities. Long Island, which includes Suffolk and Nassau counties, is home to more than 19,700 Haitians.

Michaelle Solages, Assembly District 22

Solages, a Democrat, is running to represent District 22 (Nassau County) in the state assembly. She faces Republican opponent Nicholas Zacchea in the November election.

Solages is in her fourth term as an assembly member and chairs the Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus.

Clyde Vanel, Assembly District 33

Vanel, a Democrat, is running to represent District 33 (southeast Queens) in the state assembly. He is running unopposed in the Nov. 3 election and is in his second term as an assembly member.

Vanel chairs the assembly’s Subcommittee on Internet and New Technology.

Census Bureau data from 2010 shows that more than 40,000 Haitians live in Queens.

Rodneyse Bichotte, Assembly District 42

Bichotte, a Democrat, is running to represent District 42 (central Brooklyn) in the state assembly. She will run unopposed in the Nov. 3 election. District 42 spans the neighborhoods of Flatbush and East Flatbush.

Bichotte has served in the state legislature since 2015 and chairs the assembly’s subcommittee on the Oversight of Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprises (MWBE).

Mathylde Frontus, Assembly District 46

Frontus, a Democrat, is running to represent District 46 (south Brooklyn) in the state assembly. She faces Republican challenger Mark Szuskiewicz on Nov. 3.

Frontus is running for her second term in the state assembly. She is a member of the committees on Aging, Children and Families, Mental Health, Economic Development, Tourism and Transportation.

Phara Souffrant Forrest, Assembly District 57

Forrest, a Democrat, is running to represent District 57 (Brooklyn ‒ Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights) in the state assembly. She defeated incumbent Assembly Member Walter T. Mosley in the Democratic primary. Mosley will appear on the November ballot under the Working Families Party ticket.

Forrest is a nurse, tenant activist and member of the Democratic Socialists of America organization.

This list was compiled with Sam Bojarski for The Haitian Times.

#Haitian-Americans#Haitians#US#US politics#2020 Election#New York#Florida#Larisa Karr#Sam Bojarski#The Haitian Times#Dotie Joseph#Marie Woodson#Nancy St. Clair#Gepsie Metellus#Linda Julien#Nadia Assad#Nancy Metayer#Ketley Joachim#Henry Raphael Dube#Daniela Jean#Constantin Jean-Pierre#Kimberly Jean-Pierre#Michaelle Solages#Clyde Vanel#Rodneyse Bichotte#Mathylde Frontus#Phara Souffrant Forrest

0 notes

Text

Democrats double down on vote-by-mail push in Florida’s Haitian communities

Image from a Miami-Dade county instructional video explaining in Haitian Creole how to vote by mail. Credit: Miami-Dade TV YouTube.

Election campaigners and voting rights advocates hoping to reach Haitian-Americans across Florida said they are focused on getting people to vote by mail due to COVID-19 and educating them about the voting process in the lead-up to the elections.

Much of their focus is on Haitian enclaves like Little Haiti and North Miami, which make up a significant portion of the 107,654 total registered voters in their county’s commission district. In those neighborhoods, community organizations like FANM are sending out canvassers to remind residents about ballot deadlines, answer questions about the process and assuage fears about voting. And they are doing so in Haitian Creole to engage the electorate.

“If we continue to educate voters and encourage them to vote by mail, I think that people will come out, especially given what’s at stake nationally,” said Marleine Bastien, FANM’s executive director. “We’ve realized that a lot of people in our community do not know how to vote. We take voter engagement very seriously, especially now.”

Miami-Dade County is also providing official instructions in Creole for Haitian voters who wish to vote by mail.

Other groups are following much the same script, largely due to the strategy that Democrats are implementing across the state. Karen Andre, senior advisor to Biden’s Florida statewide campaign, said voting by mail is the only way to assure the safest, most reliable count of votes.

“Voters should make their voting plans by requesting their ballots now and mailing them back or by placing them in an official dropbox at an early voting precinct as soon as possible,” said Andre. “Voters can even track their ballots with their local Supervisor of Elections to ensure they were counted.”