#Kenzaburō Ōe

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It is the second job of literature to create myth. But its first job is to destroy it.

Kenzaburō Ōe, Japanese novelist and Nobel laureate in literature at a symposium of Nobel Laureates, quoted by Mary Ruefle in Madness, Rack, and Honey

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Juzo Itami

- A Quiet Life

1995

#Juzo Itami#Jûzô Itami#A Quiet Life#静かな生活#伊丹十三#Japanese Film#1995#Kenzaburo Oe#Kenzaburō Ōe#渡部篤郎#Atsuro Watabe#Hinako Saeki#佐伯日菜子#大江健三郎

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Han Kangs Prosa ist intensiv und poetisch

Die südkoreanische Schriftstellerin Han Kang wird mit dem Literatur-Nobelpreis ausgezeichnet, weil sie in ihrem Werk »die Zerbrechlichkeit des menschlichen Lebens aufzeigt«. Damit geht der Preis zum ersten Mal überhaupt nach Südkorea.

Die südkoreanische Schriftstellerin Han Kang wird mit dem Literatur-Nobelpreis ausgezeichnet, weil sie in ihrem Werk »die Zerbrechlichkeit des menschlichen Lebens aufzeigt«. Damit geht der Preis zum ersten Mal überhaupt nach Südkorea. Die Autorin des Weltbestsellers »Die Vegetarierin« ist die achtzehnte Frau, die den Preis erhält. Continue reading Han Kangs Prosa ist intensiv und poetisch

#Annie Ernaux#Bora Chung#featured#Han Kang#International Booker Prize#Jon Fosse#Katzuhiro Ishiguro#Kenzaburō Ōe#Ki-Hyang Lee#Kyong-Hae Flügel#Literaturnobelpreis#Louise Glück#Mo Yan#Olga Tokarczuk#Preis der Leipziger Buchmesse#Swetlana Alexijewitsch#Yasunari Kawabata

0 notes

Text

Death cuts abruptly the warp of understanding. There are things which the survivors are never told. And the survivors have a steadily deepening suspicion that it is precisely because of the things incapable of communication that the deceased has chosen death. The factors that remain ill defined may sometimes lead a survivor to the very site of the disaster, but even then the only thing clear to anyone concerned is that he has been brought up against something incomprehensible.

The Silent Cry by Kenzaburō Ōe

0 notes

Text

Osobiste doświadczenie Kenzaburō Ōe

Osobiste doświadczenie Kenzaburō Ōe

„Osobiste doświadczenie” Kenzaburō Ōe, to powieść która ma na czytelniku wywrzeć niezatarte wrażenie. To nie jest książka, o której można zapomnieć i której nie da się przeczytać w jeden wieczór. Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#aborcja#II Wojna Chińsko-Japońska#II Wojna Światowa#japonia#Kenzaburō Ōe#Książka#kultura#literacki nobel#literatura#literatura japońska#noblista#okrucieństwo#Osobiste doświadczenie#Osobiste doświadczenie Kenzaburō Ōe#pogarda#przepuklina mózgowa#recenzja#rodzicielstwo#śmierć dziecka#wojna#zabójstwo#個人的な体験

0 notes

Note

Any book recs? 👉 👈

🛏️ 🐱🛌 🐱 (← us at the sleepover)

US AT THE SLEEPOVER!!!! THATS US!!!!

but I’ve been thinking a lot about my favorite Japanese translations lately, so I’ll drop three of those! I should seek more out actually

1. Black Rain by Ibuse Masuji

This is extremely heavy, following a family from post-nuclear Hiroshima (I wanna say in 1945? 46? Quite immediately post bomb).

I remember being really intrigued by the way that it explored the social stigma around those with radiation sickness after the fallout. So much of history focuses on the fear, the chaos, but what happens to those who bear the marks of a loathed history and carry it forward? Especially in a society so rooted in conformity and communal acceptance?

Reflecting on it now, it’s interesting to think about — now living in a “””””post Covid””””” world, there’s something like embarrassment about catching it now. So late? When “everyone’s already had it”? How shameful, in a bizarre way, to have illness that reminds everyone of a time we want to move on from. It’s obviously not the same, but it’s such a wildly different societal context now than when I first read it, you know?

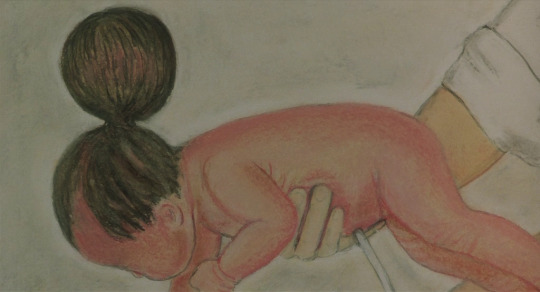

2. A Personal Matter by Ōe Kenzaburō

Another heavy, and frankly crude, story of a young father struggling to come to grips with his newborn son’s significant disability. Do not mistake this for disability representation; it’s honest and filled with self-loathing, blame towards the world for something random.

What stood out to me about this was how awful it was. The descriptions of people were simple and cutting, lacking any sort of tact or softness. As someone so afraid of writing anything even remotely “gross” — a subconscious fear of it ruining a readers immersion, somehow — I find it inspiring and brave.

I read this before getting back into writing, but I would love to revisit it again on a technical level.

3. Tokyo Ueno Station by Yū Miri

I devoured this ghost story (not in the scary way) in a single sitting. It’s a beautifully crafted commentary on the sort of… arbitrary nature of class disparity, with the main character — a recently deceased laborer— sharing multiple life milestones with the imperial family; he was born in the same year as the emperor, lived in the park that (iirc) the imperial family is set to visit before the upcoming Olympics. They’ve cosmically crossed paths and yet ended up nowhere near one another, and the author begs you to ask why.

It’s a reflective story on how the world around him continues to push on and ignore the issues that lead to his life being plagued with misfortune and misery. Excellent all around.

((saturday sleepoverrrrrr))

#I fucking love Japanese lit someone pls recommend me more thank youuuuuuuu#love u moss!!!!#ask me :)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Days of The Jackal: how Andrew Wylie turned serious literature into big business

Andrew Wylie is agent to an extraordinary number of the planet’s biggest authors. His knack for making highbrow writers very rich helped to define a literary era – but is his reign now coming to an end?

Andrew Wylie, the world’s most renowned – and for a long time its most reviled – literary agent, is 76 years old. Over the past four decades, he has reshaped the business of publishing in profound and, some say, insalubrious ways. He has been a champion of highbrow books and unabashed commerce, making many great writers famous and many famous writers rich. In the process, he has helped to define the global literary canon. His critics argue that he has also hastened the demise of the literary culture he claims to defend. Wylie is largely untroubled by such criticisms. What preoccupies him, instead, are the deals to be made in China.

Wylie’s fervour for China began in 2008, when a bidding war broke out among Chinese publishers for the collected works of Jorge Luis Borges. Wylie, who represents the Argentine master’s estate, received a telephone call from a colleague informing him that the price had climbed above $100,000, a hitherto inconceivable sum for a foreign literary work in China. Not content to just sit back and watch the price tick up, Wylie decided he would try to dictate the value of other foreign works in the Chinese market. “I thought, ‘We need to roll out the tanks,’” Wylie gleefully recounted in his New York offices earlier this year. “We need a Tiananmen Square!”

Literary agents are the matchmakers and middlemen of the book industry, pairing writers with publishers and negotiating the contracts for books, from which they take an industry-standard 15%. In this capacity, Wylie and his firm, The Wylie Agency, operate on behalf of an astonishing number of the world’s most revered writers, as well as the estates of many late authors who, like Borges, Chinua Achebe and Italo Calvino, have become required reading almost everywhere. The agency’s list of more than 1,300 clients includes Saul Bellow, Joseph Brodsky, Albert Camus, Bob Dylan, Louise Glück, Yasunari Kawabata, Czesław Miłosz, VS Naipaul, Kenzaburō Ōe, Orhan Pamuk, José Saramago and Mo Yan – and those are just the ones who have won the Nobel prize. It also includes the Royal Shakespeare Company and contemporary luminaries such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Karl Ove Knausgård, Rachel Cusk, Deborah Levy and Sally Rooney. “When we walk into the room, Borges walks in, and Calvino walks in, and Shakespeare walks in, and it’s intimidating,” Wylie said.

When the Borges auction took off in 2008, Wylie began plotting. “How do we establish authority in China?” he asked himself. Authority is one of Wylie’s watchwords; it signifies the degree to which his agency can set the terms of book deals for the maximum benefit of its clients. To establish such authority, it is critical, in Wylie’s view, to represent authors who command a position of cultural eminence in any given market – Camus in France, Saramago in Portugal and Brazil, Roberto Bolaño in Latin America. “I always look for a calling card,” Wylie said. “If you want to deal in Russia, for example, you want – dot dot dot – Nabokov.”

Who better to help him take over China, Wylie thought, than Henry Kissinger? In the 1970s, as US national security adviser and secretary of state under President Nixon, Kissinger had presided over a historic rapprochement between the US and China. Since then, he had been an important interlocutor between China and the west. Kissinger was not a Wylie client, but that was an easy problem to solve. When Wylie Googled Kissinger’s name in 2008, he was confronted with books attacking his humanitarian record. “Kissinger was depicted as a war criminal who enjoyed killing babies – basically a monster,” Wylie said. “So I went to him and said: ‘Henry, this is not good legacy management.’” Wylie told Kissinger to fire his agent. Then, he added, “You need to get all three volumes of your memoirs back in print, and write a new book, a strong book.” Kissinger quickly became a client of The Wylie Agency.

The new book would be called On China. Wylie’s plan was to sell it to the Chinese market first, an unprecedented tactic for a book by a famous American author. In 2009, a Chinese publisher bought the rights to it for more than $1m, Wylie claimed (although he later said he was not able to confirm this figure). Authority duly established, his agency has gone on to achieve seven-figure deals in China for the works of authors as various as Milan Kundera and Philip K Dick. “That is how you take Tiananmen Square,” Wylie crowed, recalling his success. “You put Henry in the first tank, and you fill it with gas!”

The Kissinger operation was vintage Wylie: tempting an author away from a competitor and then leveraging that client’s reputation to mutually beneficial ends. “He’s playing a multiyear game in which he is constantly trying to consolidate the board,” Scott Moyers, the publisher of Penguin Press and a former director of the Wylie Agency. In the 1980s and 90s, so the legend goes, Wylie used his commercial cunning to disrupt the chummy norms that reigned in the publishing industry, replacing them with what one tabloid newspaper referred to as a “greed storm”. When he met Wylie in the late 1980s, the author Hanif Kureishi later wrote, he was reminded of “the bullying, loud-mouthed suburban wide-boys I’d grown up with, selling socks and watches from suitcases on a pub floor”. Since the mid-90s, Wylie has been known as The Jackal, and many other agents and small publishers still see him as a predator who seizes literary talents nurtured by others. His agency’s approach is “very adversarial”, Valerie Merians, the cofounder of the independent publisher Melville House, said. The head of rights at a London literary agency put it more bluntly: “He uses Colonel Kurtz methods.”

But there is more to Wylie’s success and his character than mere rapacity. Better than anyone else, Wylie and his agency have figured out how to globalise and monetise literary prestige. “I took him on after my six previous agents did not provide, out of idleness, what I required,” Borges’s widow, María Kodama, once said of Wylie. The works of Borges and other classics can be found throughout Latin America and Spain, in part because Wylie makes sure that publishers “commit to keeping them alive everywhere,” Cristóbal Pera, a veteran Spanish-language publisher and a former director at The Wylie Agency, said. At the same time, Wylie’s international representation of authors like Philip Roth and John Updike has succeeded in “establishing American literature as world literature”, the Temple University scholar Laura McGrath has written.

Wylie’s literary tastes and international reach helped to create what was for several decades the dominant vision of literary celebrity. In the era in which writers such as Roth and Martin Amis had an almost equal place in the tabloids and in the New York Review of Books, when they were famous in Milan as well as Manhattan, and might plausibly afford to keep apartments in both, when they were public intellectuals living semi-public lives, Wylie was the most audacious broker of literary talent in the world, a man who seemed equally intimate with high culture and high finance.

Today, that era of priapic literary celebrity has faded, and some believe that Wylie’s stock has gone down with it. “I think the Wylie moment has passed,” Andrew Franklin, the former managing director and co-founder of Profile Books, said. “When he dies, his agency will fall apart.” A crop of younger agents and large talent agencies have attempted to adapt many of Wylie’s business strategies to a new reality, in which literary culture is highly fragmented and clients are less likely to be novelists or historians than “multichannel artists” with books, podcasts and Netflix deals.

Wylie thinks that’s bunk. Even if the era of high literary fame is dead, he believes great literature continues to represent the best long-term investment. “Shakespeare is more interesting and more valuable than Microsoft and Walt Disney combined,” repeating an argument he has been making in the media for more than 20 years. All the Bard of Avon lacked was a good trademark lawyer, a long-term estate management plan and, of course, the right agent.

If Wylie is the world’s most mythologised literary agent, it is partly because the caricature of him as a plunderer of literary talent and pillager of other agencies has been so irresistible to the media, and at times to Wylie himself. “I think Andrew quite likes the whole Jackal thing, because it makes him seem like a kind of hard man,” Salman Rushdie, one of Wylie’s longest-standing clients and closest friends. Wylie is an ardent burnisher of his own legend, which is not to say that he traffics in falsehoods. He has led a remarkable life, and even when recounting facts that are grubby or mundane, he instinctively elevates them into something more fabulous. A dealmaker, after all, trades primarily in reputation.

Wylie’s success is founded, in part, on his gift for proximity to the great and the good. As a young man, he once spent a week in the Pocono mountains interviewing Muhammad Ali for a magazine, and singing him Homeric verses in the original Greek. He visited Ezra Pound in Venice and sang him Homer, too. In New York, he spent a lot of time at Studio 54 and the Factory studying the way Andy Warhol fashioned his public persona. He says Lou Reed introduced him to amphetamines in the 1970s and that he gave the band Television its name. The photographer and film-maker Larry Clark was best man at his second wedding. At the height of the fatwa against Rushdie, when Wylie wasn’t meeting with David Rockefeller to strategize a lobbying campaign to lift the supreme leader’s death warrant, or trying to self-publish a paperback edition of The Satanic Verses, he was sitting on the floor of a New York hotel room with mattresses covering the windows for security, meditating with Rushdie and Allen Ginsberg. At Wylie’s homes in New York and the Hamptons in the 90s, party guests might include Rushdie, Amis, Ian McEwan, Christopher Hitchens and Susan Sontag, or Rushdie, Sontag, Norman Mailer, Paul Auster, Siri Hustvedt, Peter Carey, Annie Leibovitz and Don DeLillo. (There was once a minor crisis when Wylie forgot to invite Edward Said.) Wylie was one of the first people to whom Al Gore showed the PowerPoint presentation that later became An Inconvenient Truth.

In his younger days, Wylie cultivated his reputation through decadence and outrageousness. At a publishing party in the 80s, Tatler reported that he invited a young novelist to “piss with me on New York”, and then proceeded to urinate out the window on to commuters at Grand Central station. (When asked to confirm or deny this, he said, “pass”.) During a hard-drinking evening with Kureishi around the same time, he spat on a copy of Saul Bellow’s More Die of Heartbreak, called it “utter drivel”, then stubbed his filter less cigarette out on it. (Wylie denies this happened, but Kureishi wrote about it in his diary at the time and later confirmed the story to his biographer Ruvani Ranasinha.) Bellow became a Wylie client in 1996, Kureishi in 2016.

The centre of the Wylie myth, however, has long been his ferocious pursuit of business. The author Charles Duhigg, a Wylie client, has proudly said that, in negotiations with publishers, his agent is “a man that can squeeze blood from a rock”. Wylie takes pleasure in conflict, and can be joyfully bellicose. Of a former client turned adversary, of which there have been a few, he will merrily remark, “I will refrain from saying ‘Fuck you’ to Tibor, because he’s already fucked.” He is as bald, cigar-puffing and self-assured as a Churchill. At The Wylie Agency, which he launched in 1980, “the keynote is aggression”, one of his former employees mentioned. That is not just the view of his detractors; Rushdie has described Wylie with affection as an “aggressive, bullet-headed American”.

The Wylie Agency hunts for undervalued literary talent the way a private equity firm might trawl for underperforming companies that it can turn into major profit centres after firing the current management. When he started out in the early 80s, Wylie saw more clearly than anyone else that literary reputations are commercial assets, and that if you control those assets, you ought to wring as much value from them as possible. Never mind if you have to use tactics that others consider unethical or underhanded. Scott Moyers summed it up this way: “When he came into publishing he said, ‘Fuck this. Who gains by this? What am I legally allowed to do? Let’s start with that as a basis, and then I’m gonna get to work.’”

Wylie’s New York offices are on the 22nd floor of a building in Midtown Manhattan. In the small reception area hangs an enormous framed picture of the first-edition cover of The Information, Martin Amis’s eighth novel, published in 1995. This is the book that caused Wylie to become widely known as The Jackal, after he ravished Amis away from the agent Pat Kavanagh, the godmother of Amis’s first child, with a pledge to sell the novel for £500,000. Like Wylie himself, the giant poster is calculated to seem at once high-minded, tongue-in-cheek and larger than life. It is Wylie revelling in his own myth.

“I think everyone got everything right,” he said slyly, when asked if journalists had, over the years, misunderstood him. It was a quintessential Wylie move: never to seem out of control of his own persona, always on guard against the impression that someone has perceived something about him that he has not intended. But it became clear he most assiduously fosters the impression that he values great literature. That is, he appreciates it for its own sake, and he also fights to ensure it is assigned what he believes is its proper price.

Wylie was eager to present his viewpoint as being at odds with the rest of the publishing industry, which he portrayed as offering up the fast food of the mind. The attitude of most publishers and agents, he said, is roughly: “Fuck ’em, we’ll feed them McDonald’s. It may kill them, but they’ll buy it.” Bestsellers are the greasy burgers of this metaphor. If you read the bestseller list, Wylie went on, “You will end up fat and stupid and nationalistic.” The sentiment is genuine, but it leaves out the fact, as Wylie’s critics delight in pointing out, that he has represented such questionable literary lights as his landscape architect and Madonna.

It was time for lunch. Wylie’s favourite spot is the chain restaurant Joe and the Juice, and he relished his own description of the cardboard bread and desiccated tomatoes in its turkey sandwich. “You feel right next door to extreme poverty when you eat at Joe and the Juice, which is a comfortable place to be,” he said. First, though, he wanted to smoke, so he strolled through Midtown as he puffed away on one of the Cuban cigars he buys from a shop on St James’s Street in London’s Piccadilly. By habit or design, his walk brought him to the sleek glass exterior of the Penguin Random House headquarters, where he stood for a moment in front of a digital display advertising a novel called Loathe to Love You, the latest instalment of a bestselling series of romances about Silicon Valley types. Wylie was exuberantly disgusted. “I mean, that speaks for itself,” he exclaimed.

he continued walking. Colleen Hoover, a Simon & Schuster romance author who had five novels on the New York Times bestseller list that week, was at that moment the greasiest of all the greasy burgers in his mind. “Put down your Colleen Hoover and begin to live!” he exhorted the culture at large. “Throw away the Big Mac and eat some string beans!” (Stridency and snobbery are a favourite pairing in his humour.) He soon arrived at Joe and the Juice, but the wait for a sandwich was more than a quarter of an hour, so he moved on to a local diner. For lunch, Wylie ordered a cheeseburger, rare.

Wylie often claims that he does not have a personality of his own, and is constantly in search of one. “I have this sort of hollow core,” he likes to say. That seems dissembling, perhaps self-protective, but more than one observer has noted that Wylie perennially reinvents himself in ways that reflect the spirit of the age: there was the investment banker of books in the 80s, the force for literary globalisation in the 90s, a supporter of American exceptionalism in the 00s and the critic of what he sees as the twin crises of national and literary decline today. (“I support, broadly speaking, the endeavour of the United States, which is very troubled at the moment,” he said at one point.) He is a man of multiple incarnations, from which a coherence nonetheless blooms.

Wylie grew up in a moneyed and highly literate Boston family; when Rushdie visited his agent’s childhood home in 1993, he found the initials AW still carved into an oak bookcase in the library wing. But Wylie spent a good portion of his teens and 20s in rebellion against his parents’ social world. He was kicked out of St Paul’s, the ultra-elite New England boarding school where his father went, for peddling booze to fellow students. Soon after, at age 17 or 18, he punched a policeman in the face. Given a choice between reform school and a psychiatric hospital, he chose the latter. He spent about nine months at the Payne Whitney clinic on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, not far from where he now lives, pacing the courtyard and memorising Finnegans Wake. “Everyone I admired had been crazy,” he said, including Ezra Pound and Robert Lowell. “I’m not, but I can fool everyone that I am.” André Bishop, who was close to Wylie at St Paul’s and later at Harvard, used to visit Wylie in hospital on the weekends. “I don’t know if I would call him crazy – I think he was disturbed,” Bishop said. “But it was real. I don’t think he was putting on an act.” (Bishop is now the head of Lincoln Center Theater in New York and one of Wylie’s clients.)

Not long after Wylie was discharged from psychiatric hospital, he arrived at Harvard, also his father’s alma mater. “Nervous, a bit wild, gentle and intelligent,” is how the modernist poet Basil Bunting described him at 19 years old, in 1967. At Harvard and in the first few years after graduation, poetry was the centre of his life. “I’ve been having a look at the verse Eliot wrote at Harvard, and find that yours is more accomplished, despite the echoes,” Bunting wrote to him. In 1969, Wylie married his college girlfriend, Christina, and the following year, she gave birth to their son, Nikolas. The couple wrote poetry, and Wylie spent his days working in a Maoist bookshop near Harvard Square.

In 1971, Wylie left his young wife and child “with the car and the bank account” and moved to New York City. (He and Christina were “moderately unhappy people” and they divorced in about 1974; he remarried in 1980, and has two more children.) In New York, he drove a taxi and wore his beard and thinning hair biblically dishevelled, as if he were wandering Mount Sinai instead of Lower Manhattan. He rented a storefront in Greenwich Village from which he attempted to sell his college library, including editions of Heraclitus in multiple European languages. Bob Dylan and John Cage were occasional customers, but “business was not brisk”, Wylie has said. Bunting wrote with condolences: “It is equally difficult to read the books that sell or sell the books you can read.”

Wylie, his family money ultimately backstopping his risks, was undeterred. He cofounded a small press and published the first book of poetry by a young musician named Patti Smith. He began a freelance gig doing celebrity interviews of figures like Warhol and Salvador Dalí for various books and magazines. He brooded, some of his acquaintances thought, on a certain kind of fame. The punk pioneer Richard Hell, who moved in similar circles, later wrote that “Andrew’s main model was Andy Warhol, because of Warhol’s combination of artistic talent with overriding worldly ambition”.

Then, sometime in the mid 1970s, Wylie began a three-year, amphetamine-fuelled “hiatus” from life, during which he slept about six hours a week, he said. “If you grow up with money, you either spend it over the course of your life, and you’re done, or you get rid of it and start from scratch,” Wylie said. He said he injected most of his inheritance into his arm. Eventually, “a lot of people I was doing business with were apprehended and sent away, so the supply of drugs went to zero,” he added. When he recovered from a terrible period of withdrawal, he decided it was time to get on with the business of living.

The story that Wylie likes to relate of how he became a literary agent usually runs like this. It was 1979. He was off amphetamines and needed a job. Following in the footsteps of his late father, a director at the publishing house Houghton Mifflin, he applied for publishing roles. When he was asked in an interview what he was reading, he said Thucydides, and the interviewer told him he should read the bestsellers instead. “So I looked at the bestseller list and I thought, ‘Well, if that’s what you have to do to be in this business, then really and truly, fuck it, I’ll be a banker,’” he said in a speech in 2014. But banking appealed to him about as much as the bestseller list did. Then a friend at a publishing house suggested he look into becoming an agent.

As an agent, Wylie could attempt to thread the needle between commerce and quality. Books are a high-risk, low-margin business; Wylie has compared its profits unfavourably to those of shoe-shining. But the best literary works can remain in print for a long time, generating small but steady streams of income. Wylie began by renting a desk in the hallway of another agency, where he learned “how not to do things”. In his telling, it was just Harvard men getting drunk with Harvard men, selling unread manuscripts by Harvard men to fellow Harvard men. Wylie saw an opportunity: by treating books with the utmost seriousness, and by treating business as business, he could carve out a profitable niche for himself. In 1980, Wylie borrowed $10,000 from his mother, and The Wylie Agency was born. “We would corner the market on quality, and we would drive up the price,” Wylie later said of his business philosophy, to the sociologist JB Thompson.

The best writers needed serious wooing, Wylie understood, so he became an unparalleled practitioner of the grand gesture. He would call a writer and ask to meet next time he was in town. Then he would get the next flight to town, where he would recite to the writer swathes of their own prose, or verses of Homer. Wylie flew to Washington DC to win over the radical American journalist IF Stone. He flew to France to sign the deposed Iranian president Abolhassan Banisadr, whose book on Iran he miserably failed to sell. He flew to London to woo Rushdie, who demurred, so he flew to Karachi to sign Benazir Bhutto, who didn’t. Then he flew back to London for another go at Rushdie, who, impressed by the Bhutto manoeuvre, became receptive to Wylie’s advances. Surprise next-day arrival, the deployment of one client to attract another and the chanting of dactylic hexameters became canonical elements of the Wylie mating ritual.

Charm offensive complete, Wylie would talk money. “The most important thing … is to get paid,” Wylie told Stone, his first client, according to the biographer DD Guttenplan, who is also a client of The Wylie Agency. The bigger the advance, the better, Wylie went on: the more a publisher spends on buying a book, the more they will spend on selling it. Thompson later dubbed this “Wylie’s iron law”. The 80s were a good time for getting paid. Thanks to a historic rise in the number of readers after the baby boom, an explosion in book sales and the conglomeration of booksellers and publishing houses, publishers had more money, enabling agents like Wylie to demand higher and higher advances for their clients. Once one literary writer got a six-figure book deal, others expected to get six figures, too.

Within a few years of opening his agency, Wylie had an exquisitely curated list of a dozen or so writers. He devoted “seasons” to learning about one or two fields, from politics to art and theatre, and then courted the most significant names in each. He signed up Ginsberg and William Burroughs, David Mamet and Julian Schnabel. He also added the New Yorker writers and fiction editors Veronica Geng and William Maxwell, important nodes in the discovery network of new talent. In the mid-80s, he partnered with an agency in the UK and started systematically pursuing writers whom he deemed to be “underrepresented” by other agents. By the time he convinced Bruce Chatwin, Ben Okri, Caryl Phillips and Rushdie to leave their agent in 1988, Wylie was quickly becoming one of the most important conduits of money and influence in literary culture. As Ginsberg told Vanity Fair, Wylie was “assuming the normal powers of his family station after a long, experimental education which had ranged from high-class to the gutter”.

Every April, Wylie flies to London for the London Book Fair. For three days, he and his colleagues meet foreign publishers, pitching them books, negotiating deals and gathering intelligence on the state of their businesses. The Wylie Agency has offices in a Georgian townhouse on London’s Bedford Square, but Wylie often takes his meetings in the courtyard of the American Bar at the Stafford hotel, off St James’s Street, where cigar-smoking is encouraged. He was there on a Sunday morning before the fair. It was the start of a 12-day trip that would also take him to the south of France to meet the Camus family and to Lisbon to meet the Saramagos. Then he would fly back to New York, where he was looking forward to celebrating Kissinger’s 100th birthday. In London he would mostly be doing “just the tedious usual shit”, he said – pitching books to publishers and negotiating deals.

That Wylie is an agent who can demand six or seven figures and be taken seriously comes, in part, from close study and good information. “We are intensely systems-driven,” he said. “If the computer tells you that Saramago’s licence in Hungary is expiring in three months, then you look at the entire Hungarian market.” Teams of two or three Wylie agents regularly fly around the world to visit publishing houses, speak with editors and take photographs of their buildings. They generate a report on each house that is shared throughout the agency. “It was badly heated, staff seemed depressed but the publisher herself was quite vibrant,” Wylie said, as if he were reading one of the dossiers. Wylie also takes advice about certain markets, like Russia, from members of the prestigious Council on Foreign Relations, of which he is also a member.

If that all sounds a bit like intelligence-gathering, it is. “I’m very interested in the work the CIA does and how they do it,” Wylie said. “I think there’s a lot to learn from the agency about the way things work politically, and the way strategic calculations are made.” He has had a number of clients who are working or have worked at the CIA, including the former director Michael Hayden and the current director, Bill Burns. “We have access to projects that come out of the CIA as a first port of call,” Wylie said. He added that it was out of a CIA operation that he represented King Abdullah II of Jordan’s 2011 book, The Last Best Chance. When asked whether he could say more, he thought for a moment, then replied, “I probably can’t.”

Today, The Wylie Agency makes about half of its money in North America, and the other half from the rest of the world. “Part of our practice is to always be looking at how international publishing markets are shifting,” Wylie said. Romania and Croatia were up and coming, he added, as was the Arabic-language market. Korea was “very dynamic”. China, of course, was key.

Other people in the publishing industry, particularly smaller agents and publishers, think that Wylie’s highly efficient operation has harmed the culture and spirit of the book world, turning the genteel pursuit of publishing into a race to the bottom line. Andrew Franklin, the former Profile Books director, said that Wylie had built a factory that simply churns out deals. “It’s like a really efficient law firm,” Franklin said. (His colleague, Rebecca Gray, who has since taken over as managing director of Profile, remarked, “I think that’s the rudest thing that a publisher can say.”) A number of people in the industry suggested that the more talent Wylie has moved from small, independent presses to conglomerate imprints with large balance sheets, the more he has eroded the broader ecosystem of literary publishing. Wylie replied that this sounded like “the logic of resentment coming from small publishers who were no longer allowed the luxury of underpaying and underpublishing writers of consequence”.

Yet the issue is not just about money. Beyond handling the business side of things, agents are often a writer’s first reader, most attentive editor, therapist and dear friend; some people in the industry see the relationship as an almost sacred bond. A few months before the agent Deborah Rogers died in 2014, Kazuo Ishiguro remarked that “she taught me to be a writer”. Like Kureishi and McEwan, Ishiguro had remained her devoted client even while Wylie was seducing other clients away from her.

But most writers need to get paid, too. Kureishi, for one, long had qualms about the advances his books were reaping. When he joined The Wylie Agency two years after Rogers’ death, he was suddenly able to access a “different level of money and efficiency”, he told his biographer. Likewise, Barbara Epler, the president of the small but influential publishing house New Directions, mentioned a conversation she had in 1998 with the German writer WG Sebald when he left her for another imprint. “He said, ‘Barbara, you know you’ll always be my publisher. But the new novel – Wylie is getting me a half a million dollars for it!’”

Alongside the critique that Wylie has coarsened the industry, a number of people suggested that he has a tendency to aggrandise his accomplishments. Several publishers who work in China said that the Chinese may flatter Wylie that he’s a big deal, but that other agencies, like Andrew Nurnberg Associates, are much more influential there. Wylie made an important contribution to the career of a well-known American historian by suggesting the historian write for the New Yorker; the historian said that writing for the magazine had been a lifelong dream, and Wylie had nothing to do with it.

“There is Trump, Boris – and then there is Andrew Wylie,” Caroline Michel, the CEO of Peters Fraser and Dunlop, a rival agency, said, when she was asked about Wylie, who had recently taken over one of her firm’s clients, the estate of the Belgian writer Georges Simenon. Wylie claimed that, among other things, Peters Fraser and Dunlop had missed major commercial opportunities in the US and China. Michel rejected that account. When her agency acquired the Simenon estate 10 years ago, she said, fewer than a dozen of his 400 books were in print in English. Within seven years, she continued, they had all of the 100 or so Maigret books in print in English, and three years later her agency sold its portion of the rights for 10 times what it had acquired them for.

“What we did with those books from nothing could be considered one of the great reinventions” of a literary estate, Michel said. “But Andrew can blow smoke up his own ass if he wants to.”

Simenon is in many ways a classic Wylie target: the estate of an internationally popular author with a highly exploitable backlist who nevertheless has the requisite literary value. (“With Ian Fleming, it’s all surface,” Wylie said. “Simenon has the psychology.”) But it is only the most recent of Wylie’s campaigns of avid expansion. In 1997, the renowned agent Harriet Wasserman could already gripe that Wylie had annexed “more literary territory than Alexander the Great”. She also said she would rather clean the men’s toilet bowl in a New York subway station with her tongue than meet him: he had recently enticed Saul Bellow away from her. “There were a lot of agents who were tough, and there were some who were literate,” said Andrew Solomon, who became a Wylie client in 1998, when he was 24 years old. “But you tended to have to choose.”

Wylie was always thinking globally. In the 2000s and 2010s, he made two serious attempts to enter the Spanish language market directly by opening up an office in Madrid and buying a renowned agency in Barcelona (both failed). He attempted to sign up many of the most important American historians (a success) and to sell their books abroad (a failure). He attempted to force the major publishing houses to give authors a greater share of royalties for digital rights by setting up his own ebook company (also, in most respects, a failure). He began recruiting African writers who won the continent’s prestigious Caine prize (seven successes to date). He went after the estates of JG Ballard, Raymond Carver, Vladimir Nabokov, John Updike and Evelyn Waugh (success, success, success, success, success).

The pace of Wylie and his business in these years was not what many people expected of the publishing industry. “You were working on what sometimes felt like the floor of Wall Street,” said a former employee who worked at The Wylie Agency in the mid-00s. “An intellectual sweatshop for kids fresh out of the Ivy League,” is how another former employee described it. The workday was 10 hours long, and Wylie had an intense control over the minutiae of what was happening in the office. “You had to account for your whereabouts for anything longer than – excuse my crassness – taking a shit,” someone who worked in the New York office said. Wylie was generous and interesting, they claimed, but he didn’t stop some of his senior employees from being borderline abusive. A female employee from the mid-00s said that when a bunch of the assistants in the office saw The Devil Wears Prada, it struck a chord.

Despite that, “You felt you were in the midst of something important,” the person who worked in the New York office said. Staff might encounter Philip Roth wandering through the hallways; Al Gore or Lou Reed might be on the other end of the telephone. At Christmas parties, champagne flowed and Wylie would greedily dig the last of the caviar out of the tin with his finger. Hermès neckties were given to the gentlemen and cashmere scarves to the ladies. Even at other companies’ publishing parties, people were gossiping about The Wylie Agency: a now-legendary story went around New York that one evening Roth phoned the office. “Hello, The Wylie Agency, this is Andrew speaking,” an assistant at the other end of the line said. The excited caller, mistaking the assistant for the other Andrew, claimed – dubiously, to judge by recent reporting – that he had just gone to bed with the female lead in the movie being made of his novel The Human Stain, Nicole Kidman. The assistant, embarrassed, offered to put him through to Mr Wylie.

The Wylie Agency is still immensely influential, but the glamour of those previous decades is gone. For a long time, Wylie was known for his expensive neckties and Savile Row tailoring; Martin Amis proudly explained to his sons in the late 90s that his agent was called The Jackal “because of his claws and his jaws and the tail-slit in the back of his pinstripe suit”. But spending time with Wylie over several days in New York and London, he always wore blue jeans and a woollen shirt-jacket. Day after day, the uniform never changed; it suggested that his old suits were props in which he took no intrinsic interest, and that if he no longer had need of them, they could be cast away.

The week of the London Book Fair provided an inside view of the messy business and meagre economics of buying and selling highbrow books today. In a convention centre in west London, hundreds of agents were meeting with publishers from around the world. There were desks laid out in long rows, like an examination hall, but meetings were spilling over on to the floors, with several taking place against the wall by the entrance to the bathrooms. “Isn’t this horrible,” Wylie remarked. “It’s like a prison camp. Every time I come here I wonder what I’ve done to deserve this. I thought I was a good boy.” At another moment, he compared the convention centre to an elementary school in Lagos. “I’m going to get in trouble for saying that,” he said, despite the fact he had said it on the record many times before. “My Nigerian friends are going to find it condescending.” But he seemed to understand that its inappropriateness was the very thing that would get it repeated, and hopefully heard by the organisers of the book fair. It was tactical vulgarity. “Indiscretion is a weapon,” he mentioned once.

As he and his deputy, Sarah Chalfant, met publishers from around the world, Wylie often came across as more avuncular than avaricious, though he could be petulant at times. Wylie and Chalfant’s conversations with publishers ranged from the state of politics and the publishing industry to deeply personal stories about family travails. There were also, as always, writers’ egos to consider. At one point they discussed with an editor whether they should tell a famous English-language writer that no one could understand her when she spoke the language of her adopted country. They decided not to. (A writer’s “self-perception needs to be honoured”, Wylie had mentioned in another context.)

Much of The Wylie Agency’s business at the book fair concerned moving authors from one publishing house to another, or pitching authors to publishers in countries where they weren’t yet published, or reassuring publishers that major authors were, indeed, hard at work on their next no doubt excellent and very profitable books. Everybody wanted to know if Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Sally Rooney were writing again. It was relayed to favoured publishers that Rushdie was quietly at work on a book about the recent attempt on his life. “It’s critical for authors to be placed strategically in every country in the world, with a plot line that makes sense,” Wylie said. Having a good book with a bad publisher is “like trying to sell Hermès ties at Target”.

There were also plenty of negotiations, over the mostly paltry sums that even relatively good books were commanding in international markets. At breakfast one morning, a Brazilian editor offered $5,000 for the latest book by a major financial journalist, but Wylie pretended to mishear him. “You said $8,000, right?” The gambit worked, but Wylie was enjoying himself too much to stop. “We should sit further apart,” he said to the editor, sliding his chair back an inch or two. “Because over here it sounds like $12,000.” When work by the Israeli writer Etgar Keret came up for negotiation, Wylie jubilantly declared, “$12,000 – that’s the breakfast price!”

During other conversations, in the place of Wylie’s famed forcefulness was sometimes a vaguely flirtatious insouciance, though it wasn’t always clear who it was intended for. At one meeting, Wylie introduced an editor from one of Europe’s most esteemed publishing houses as “disadvantaged but interesting” and said she had been raised by Gypsies in a small town in some provincial country. She clarified that she had been born in a major European capital.

Later in their conversation, the editor worried about what to do with the latest novel by an award-winning British writer. “The modest offer you are waiting to make will be accepted, maybe with a small improvement,” Wylie told her. He suggested €6,000.

“It’s not going to work, since he only sold 900 copies of his last book,” the editor replied.

“This is the weakest argument I’ve ever heard in my life,” Wylie teased. “The flaws are transparent and resonant.” He pointed out that a publisher’s greatest profitability comes before an author earns back their advance, then he suggested €5,000.

“More like €4,000,” the editor said.

“Forty-five hundred? Done.” Wylie announced, pleased but not triumphant.

As meagre as that amount was, if the agency could make 20 such deals around the world for a writer, and earn a similar amount just in North America, a writer might, after the 15% agency fee and another 30% or so in taxes, afford to pay rent on a two-bedroom Manhattan apartment for a couple of years. How they would eat, or pay rent after two years if it took them longer than that to write their next book, was another question.

One morning before heading to the London Book Fair, Wylie and Chalfant had breakfast with Luiz Schwarcz, the co-founder of the Brazilian publishing house Companhia das Letras. Wylie first met Schwarcz in 1986, when he had just moved into the building where he still has his New York offices. For all Wylie’s talk about being able to drive a hard bargain because he’s not friends with publishers, it was evident Schwarcz and he were close. “I saw the beginning of the agency with no place to sit,” Schwarcz remembered. “You were ordering the furniture.”

Back then, Schwarcz had just started his own publishing business, and Wylie said to him: “One day, I will represent Borges and you will publish him.” They had achieved their vision, but it now seemed as if the literary world Wylie had once dominated was passing away. It was true that many publishers had so far survived the onslaught from Amazon, and had even thrived during the pandemic, yet it often felt to Wylie like the space for writers he admired was shrinking. “Penguin Random House, in the wake of its failed attempt to acquire Simon & Schuster, is drifting into an accounting operation,” he complained to Schwarcz at one point. “Everything is now guided by the numbers. They’ve moved away from the fact that they are publishing writers. They’re publishing a spreadsheet, and it’s dangerous.”

“There’s been a total neglect of the backlist,” Chalfant added.

“It’s more than neglect,” Wylie went on. “It’s ignorance. The problem is none of them read anything.”

That alleged ignorance was arguably a threat not only to literature, but to the long-term existence of The Wylie Agency itself. In order for his high-minded dynasty to succeed, he needs publishers with deep pockets and high minds to succeed with him. “Andrew understands that his brand of publishing and his vision for his authors will die if the publishers who espouse the same view die,” a former employee who still works in the publishing industry said.

Wylie has said in the past, with self-parodying grandiosity, that he believes he is immortal and will run the agency for several years after his death. In reality, in the mid-00s, he seriously considered merging his business with CAA, the Los Angeles-based sports and talent agency, but felt it didn’t sufficiently understand his vision. Now, he said, he wants to do something comparable to the French publishing house Éditions Gallimard, “which has lasted and thrived and grown for three generations”. He has chosen Chalfant as his successor; she already oversees the agency’s London office and is effectively the firm’s CEO. Many other agents have also been at the firm now for a decade or two, and some of them have very close relationships with the agency’s major living writers, as Chalfant does with Adichie and Cusk, Jin Auh does with Ling Ma, and Tracy Bohan does with Sally Rooney. “The operation is no longer just about me, or me and Sarah, as it was for a long time,” Wylie said.

Wylie still handles about 40 deals a year, but over the past decade, he has found himself performing with greater frequency a more morbid role: announcing the deaths of clients. In 2013, it was Chinua Achebe and Lou Reed. In 2018, Philip Roth. In 2022, it was almost Salman Rushdie, after he was stabbed 10 times during an attack at a lecture. In 2023, it was Martin Amis. Today, about 10% of Wylie’s clients are estates of dead writers. Many of the publishing titans he came up with, and against, are also gone, including Roger Straus, Sonny Mehta, Jason Epstein and Robert Gottlieb. Literary epochs are ending all around him.

“I’ve spent so much time trying to persuade the publishing industry to invest in literature that’s actually interesting,” he said at one point, with an uncommonly earnest weariness. “I don’t know if that’s just tilting at windmills, or whether by some magic it might have some effect.” When Wylie was constructing his agency, he used to think often of The Palace at 4am, a delicate, scaffolding-like sculpture by the Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti. The spindly artwork, a favourite of Wylie’s client and mentor William Maxwell, appears magnificent and perpetually at risk of collapse. “The image that came to mind was being in a dense wood, in fog, and approaching a clearing, and the light dawning a little bit, and The Palace at 4 am becomes visible, and that’s what I’m building,” he said.

By contrast to the fragile palace he had once dreamed of building, Wylie compared his rivals, the big agencies, to “a football stadium at noon”: there was nothing subtle or ennobling about them. Nevertheless, they were the avatars of our new literary era. These agencies’ clients were, in Wylie’s eyes, a slurry of cosy Scandinavian cookbook writers, “as-told-to” biographers and bland comedians with streaming television shows. Perhaps these were now the calling cards that counted in the publishing world, but Wylie felt that Borges, Camus and Shakespeare, and maybe even Kissinger, were still the authors that really mattered. How, without such cultural weight behind them, would other agencies and new literary lights achieve the global eminence that even near-contemporaries like Roth and Amis once had? “How,” Wylie asked, “are they going to establish their authority?”

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

We can remember several occasions, in the past, when the chances of living or dying were balanced. (...) Every time you find yourself at a crossroads between life and death, two universes open up before you: one loses all relationship with you because you die, the other maintains it because you survive in it.

— Kenzaburō Ōe, A Personal Matter

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leo Tolstoy. Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Marcel Proust. Walt Whitman. Alan Wilson Watts. Czeslaw Milosz. Nadine Gordimer. Elias Canetti. Banana Yoshimoto. Kenzaburō Ōe. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Alexandre Dumas.

#literature#quotes#poetry#writeblr#star signs#zodiac signs#writing prompt#leo tolstoy#mary elizabeth braddon#marcel proust#walt whitman#alan wilson watts#czeslaw milosz#nadine gordimer#elias canetti#banana yoshimoto#kenzaburo oe#aleksandr solzhenitsyn#alexandre dumas

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiya, thanks for indulging me in my little hyper fixation!

(╹◡╹)♡

I have more questions if you’re interested in sharing!

Is there any connection between the real Port if Yokohama and the irl authors? Did Asagiri choose Yokohama for a specific reason or something like that?

Do the authors in a specific organisation get chosen for their irl relationships or was it randomized?

How do the literary texts have connections with manifestation of the ability in universe? (Some are obvious others not so much eg. For the Tainted Sorrow = gravity???????)

Sorry for the long ask. I hope you have a nice day! :D

I've hesitated to answer this ask because I wanted to be thorough and give each question due consideration. Further, the latter two questions rely a lot on my individual interpretation and I can't offer very much objectivity. But, I think I might be overthinking it, so below, please find attempts at answering each in turn.

The Port of Yokohama

The characters in Bungo Stray Dogs are named after and inspired by authors from modern Japanese literature. The "modern" era of Japan is generally (albeit not necessarily appropriately) measured as beginning during the Meiji Restoration, during which Japan restored centralized Imperial rule, ended a centuries-long seclusion by opening its borders to the West, and rapidly industrialized. For reference, Britain's Industrial Revolution spanned eighty years, from 1760 to 1840. By contrast, Japan industrialized within, roughly, forty years.

Japan reluctantly opened to the West under duress; Commodore Perry arrived in Japan with a squadron of armed warships, a white flag, and a letter with a list of demands from US President Fillmore. A year later, Japan signed the disadvantageous and exploitive Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States (日米修好通商条約, Nichibei Shūkō Tsūshō Jōyaku), which opened the ports of Kanagawa and four other Japanese cities to trade and granted extraterritoriality to foreigners, among other trading stipulations.

However, Kanagawa was very close to a strategic highway that linked Edo to Kyoto and Osaka, and the then-government of Japan did not relish granting foreigners so much access to Japan's interior. So, instead, the sleepy fishing village of Yokohama was outfitted with all the facilities and accoutrements of a bustling port town (including state-sponsored brothels), and the Port of Yokohama opened to foreign trade on June 2, 1859.

Thus, Yokohama is representative of Japan's opening to the West, including Western literature. Short stories and novels as the mediums we know them were Western imports to Japan, and Western literature shaped, inspired, and became subject to cross-cultural examination by Japanese authors.

This included Russian literature: Kameyama Ikuo, a Japanese scholar of Russian literature, described Fyodor Dostovesky's enduring popularity in Japan as follows:

In Japan, there were two Dostoevsky booms during the Meiji period [1868-1912], and The Brothers Karamazov being translated into Japanese for the first time in 1917 triggered a third. After that, critics like Kobayashi Hideo led fourth and fifth waves of popularity before and after World War II, and then Ōe Kenzaburō led the sixth wave around 1968, right when the student protests were at their height. Today we might say we’re in the middle of a seventh, with Murakami Haruki writing about how he was influenced by The Brothers Karamazov.

I've oversimplified Yokohama's role in Japan's modern engagement with the West substantially for the sake of brevity, but in short, yes, Kafka Asagiri chose the Port of Yokohama for a reason. Yokohama was, for a time, Japan's most influential, culturally relevant international metropolis, before becoming eclipsed by Tokyo in more recent history.

The Organizations

There aren't bright-line rules to explain why each character is in each organization, although it isn't randomized either.

Attempts to delineate between the organizations based on the irl!authors' philosophies, legacies, literary genres, degrees of acceptance or rejection of Western influence, etc., are inaccurate oversimplifications at best. (At worst, they're orientalist and, in some cases, conflate fascist ideology with literary aesthetics -- or literary aesthetics with violence; I've seen both, oddly enough.)

That said, the namesakes' irl relationships and literary impacts are sources of inspiration for the relationships in bsd, including between and among the various organizations. For example, Jouno, Tetchou, and Fukuchi were all among Japan's first Western-style newspaper editors. Kouyou and Mori were in the same literary circles and collaborated on influential publications; such as the magazine in which they penned anonymous reviews of works by emerging authors that made or broke careers, and which established modern literary criticism in Japan. Akutagawa is such an enduring and intimidating titan in Japanese literature; the sharpness of his prose and his ability to gut me like a fish suit bsd!Akutagawa's theatric and violent role within the Port Mafia.

But, Mori Ogai and Yosano Akiko were dear friends, Chuuya Nakahara idolized Kenji Miyazaki, and modern Japanese authors weren't mafiosos, private detectives, military police, or surreptitious intelligence officers. I'd warn against (i) cramming bsd's characters into oversimplified archetypes or literary devices and (ii) overinflating the importance of or reading any certainty into the patterns and reflections of the irl!authors. bsd makes dynamic and creative use of its source material to tell a story that's very much its own.

The source material absolutely adds depth, commentary, and intention to Kafka Asagiri's storytelling, but only if read within the context and framework of the story being told.

For an example of why strict dichotomies and oversimplified metanalysis don't work for comparing the various organizations, I wrote a post explaining why it's inaccurate to compare the Port Mafia and the Agency using an East vs. West framework here.

The Abilities

Yes, the literary texts inspire how the corresponding abilities manifest in-universe. At least, I think so, based on my own interpretations. For example, I see the green light across the bay from The Great Gatsby in the Great Fitzgerald and a throughline between Fyodor's bloody ability and the symbolic eucharist in Crime and Punishment.

I speculate about Fyodor's ability manifesting as imagery from Crime and Punishment here.

I mention the potential relationship between irl!Akutagawa's literary voice and bsd!Akutagawa's ability here.

I also share some thoughts on Dazai and the manifestation of No Longer Human based on narration from No Longer Human here.

For the Tainted Sorrow, in particular, is a poem about grief, which characterized much of Chuuya Nakahara's brief life. I've always experienced grief in intense fluctuations of weight -- sometimes heavy and immobilizing, sometimes untethering and billowing, often compulsive and consuming. It has an immense gravity.

I've always thought that bsd!Chuuya's manipulation of gravity emblemized his intense and layered relationship with grief -- for irl!Chuuya, his brother, his parents' brutal expectations, his lover, his friends, his son; for bsd!Chuuya, the Sheep, the Flags, the yet-named seven taken by Shibusawa's fog. But where irl!Chuuya was seemingly crushed by the gravity of what he lost, bsd!Chuuya defiantly persists with a rougish levity, his grief galvanizing his ferocious love for others and his desire to live for and in service of their memories.

To roughly quote bsd!Chuuya's character song, "I will manipulate even the weight of this cut-short life."

But, that's only my interpretation; take it with a grain of salt. Or with the weight of several pounds of salt. The extent to which it compels you is yours to decide.

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bsd meta#bsd analysis#i have no idea if any of this is useful to anyone given its subjectivity and cursory overview of really complex topics#i have more thorough breakdowns of things like my crime and punishment analysis and the influence of the West on modern japanese literature#but each of these answers could be a dissertation length analysis and unfortunately I do not have the bandwidth to go totally wild on them

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenzaburō Ōe's Mishima roast novella The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away captures the spirit of fascism in such a pertinent manner. Dying guy wasting away in the hospital daydreaming of the glory days of empire and imagining the emperor coming to save him. Many such!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juzo Itami

- A Quiet Life

1995

#Juzo Itami#Jûzô Itami#A Quiet Life#静かな生活#伊丹十三#Japanese Film#1995#Kenzaburo Oe#Kenzaburō Ōe#島本美知子#大江健三郎

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just finished A Personal Matter by Kenzaburō Ōe and JFC that was dark. Anyway, now I can’t help but think about the fact the people who complain about MHA’s character writing being problematic would fucking hate a lot of seminal Japanese literature. Nobody give them a copy of this book or No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai.

#rambling#mha#I need a separate rating system for this book was objectively well written but a horrible experience although I think that was the point#on Goodreads

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

—Kenzaburō Ōe, tr. David L. Swain

#thinking about things that alter our lives and ourselves on such a deeply fundamental level...#idk i just love the way this is phrased#¶#quotes#gendzl reads#Hiroshima Notes by Kenzaburo Oe

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Nikolai, have you read any books recently with your darling shibe?

"Maddie, my friend! It seems you are here to ask me another question hm? Well... The thing is... We haven't read any books together, just only Nikolai all by himself while Malishka is busy studying her notes for her 3rd assessment next week as she would also make her speech for her Oral Communications performance task..." Sighs

"She has a lot of things to do and she makes me and the others worry for her... Nikolai doesn't want her to end up sick, that is why me, Gavi, and that horny bastard mafia boss are here for her. But let's answer question now shall we? Now where did she put those books..." Quickly lefts the room and went to look for it. Afterwards, he went back here with several books on his hands

"Rodnaya has a lot of books in her room but this is what I remembered when she told me she plans on reading these books Nikolai bought. First is Confessions by Kanae Minato which Shin wanted to read it but she handed it to her best friend since she promised her to bring it way back on the first day of school. Next is the Silent Cry by uh... How do you say this?"

"Kenzaburō Ōe"

"да, that one. I guess Takeo taught you well how to say these Japanese words or even phrases and others. Anyway, Shin and I will be planning to continue reading Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky and also that one book that looks like a bible..."

"You mean Haruki Murakami's The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles and Kafka on the Shore?"

"... You always like buying big books for your big brain huh?"

"I just wanna learn how to write, Nik. Those books together with After Dark was something that sparks my interest until I have the motivation to write my own little fics here."

"Aww, of course you do my little writer and artist. You are already making this Russian man proud of you of what you have achieved. It always brings tears to my eyes." Gives Shin some headpats

Blushes a little "You guys really do love giving me headpats..."

#asks#asks answered#moot's ask/s answered#the writer and artist#I am trying my best to give some time on reading but school doesn't let me :'>#I am going to read those Japanese literature I have on my shelf because I miss reading those since 2020-2021

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zerwać pąki, zabić dzieci

Zerwać pąki, zabić dzieci

“Zerwać pąki, zabić dzieci” to przejmująca opowieść o grupce chłopców z poprawczaka, którzy zmagają się z wojenną rzeczywistością. Brzmi banalnie, ale podane jest w doskonale okrutnej, dosadnej formie, która nie stara się niwelować uczucia wściekłości czytelnika. Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#burakimini#burakumin#chiny#człowieczeństwo#dzieci#Golding\#II Wojna Chińsko-Japońska#II Wojna Światowa#jakuza#japonia#Kenzaburō Ōe#klasy społeczne#Książka#kultura#literacki nobel#literatura japońska#ludzie#noblista#prostytucja#przemyślenia#recenzja#uchodźcy#wieśniacy#więźniowie#William Golding#wioska#wojna#wykluczenie społeczne#Władca Much#yakuza

0 notes