#Jean-Pierre Vernant

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

You deliriously dance the bacchanal of Hades.

— Jean-Pierre Vernant, The Medusa Reader, transl by Thomas Curley & Froma I. Zeitlin, (2013)

#French#Jean-Pierre Vernant#The Medusa Reader#Thomas Curley#Froma I. Zeitlin#(2013)#Medusa#Hades#Essence

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

✦ A L T A L U N A & C U C U F A T E ✦ Research

"When Oppian describes the cunning of the fishing frog squatting in the mud, motionless and invisible, he compares it to the fox: ‘The scheming fox (agkulómetis kerdō) devises a similar trick; as soon as it spots a flock of wild birds it lies down on its side, stretches out its agile limbs, closes its eyelids and shuts its mouth. To see it you would think that it was enjoying a deep sleep or even that it was really dead, so well does it hold its breath as it lies stretched out there, all the while turning over treacherous plots (aióla bouleúousa) in its mind. No sooner do the birds notice it than they swoop down on it in a flock and, as if in mockery, tear at its coat with their claws, but as soon as they are within reach of its teeth the fox reveals its cunning (dólos) and seizes them unexpectedly. The fox is a trap; when the right moment comes the dead creature becomes more alive than the living. [….] If the metis of the fox is immediately detectable in its skill at playing dead, it is dazzlingly apparent in this sudden reversal. In effect, the fox holds the secret of reversal which is the last word in craftiness." - Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society by Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant, pp. 35-36

#writeblr#writeblr community#writers of tumblr#writers on tumblr#writing community#writer community#writblr community#WIP: THE SORCERER'S APPRENTICE#OC: CUCUFATE#Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society#Marcel Detienne#Jean-Pierre Vernant#greek mythology#goddess metis#fox#fox mythology

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

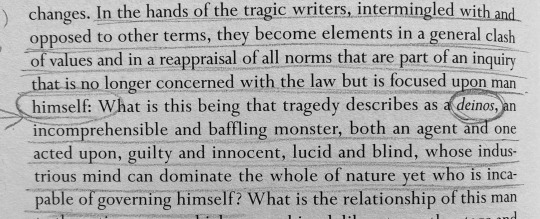

What is this being that tragedy describes as a deinos, an incomprehensible and baffling monster, both an agent and one acted upon, guilty and innocent, lucid and blind, whose industrious mind can dominate the whole of nature yet who is incapable of governing himself?

Jean-Pierre Vernant, Myth and Tragedy in Ancient Greece, trans. Janet Lloyd

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Pierre Vernant: VASELJENA, BOGOVI, LJUDI [GRADAC – ALEF 52]

Naslov knjige Žan-Pjera Vernana Vaseljena, bogovi, ljudi govori da su mitovi sveobuhvatnost života. U njima je sačuvana tajna stvaranja, odnos bogova prema stvaranju, ali i čovekov položaj na ovom i na onom svetu. Put grčkih mitova vodi od pričâ dadilja (kako je to rekao Platon) do tragedija na antičkim pozornicama. Ali, taj se put nastavio do Šekspira, Rasina i Korneja, da bismo ih ponovo sreli…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Jacques Le Goff, Jean-Pierre Vernant – Tarih Üzerine Diyalog (2024)

Fransız tarih ekolünün iki dev ismi arasında tarih üzerine ufuk açıcı bir söyleşi. ‘Tarih Üzerine Diyalog’, Fransa’da Fernand Braudel ve Marc Bloch’un kurduğu “Annales” okulunun yetiştirdiği, Fransa tarihinin iki önemli ismi olan Jacques Le Goff ile Jean-Pierre Vernant’ın 2004 yılında Emmanuel Laurentin eşliğinde France Culture radyosu için yaptığı söyleşilerden oluşuyor. Ortaçağ uzmanı Le Goff…

View On WordPress

#2024#Emmanuel Laurentin#Emmanuel Laurentin ile Söyleşiler#Jacques Le Goff#Jean-Pierre Vernant#Tarih Üzerine Diyalog#Yapı Kredi Yayınları#Yunus Çetin

0 notes

Text

Reblogging for the Jean-Pierre Vernant shout-out. He is one of the great experts and minds of France when it comes to Greek mythology, and his books are absolute must-reads.

And also for the cute little pigsies.

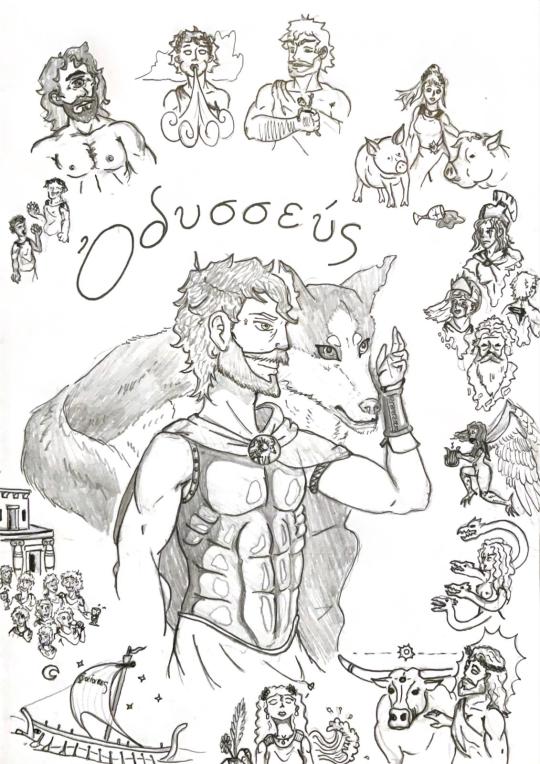

I'm going to start my third year of classics at Uni and last week I read for the first time the whole Homer's Odyssey and an analysis by Jean-Pierre Vernant "The Universe, the Gods, and Men". I was so hyped and amazed by this story -that I already knew but never read- that I picked up my pen again and I drew this.

I also listened to Epic the musical for the first time while drawing this and I was speechless!

So here's my interpretation of Odysseus and his dog Argos, surrounded by tokens of everything he went through :)

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

For archaic thought, the dialectic of presence and absence, same and other, is played out in the otherworldly dimension that the eidōlon, by being a double, contains, in the miracle of something invisible that can be glimpsed for just an instant.

- from "The Birth of Images," Jean-Pierre Vernant; transl. Froma Zeitlin

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Origines de la pensée grecque- The Origins of Greek Thought

Jean-Pierre Vernant - Les Origines de la Pensée Grecque, Presses Universitaires de France (PUF) 1962, republished several times since then.

" L'ambition [de cet essai] n'était pas de clore le débat par une étude exhaustive mais de le relancer... j'ai tenté de retracer les grandes lignes d'une évolution qui, de la royauté mycénienne à la cité démocratique, et marqué le déclin du mythe et l'avènement de savoirs rationnels. " En quoi consiste le miracle grec ? Quelles sont les innovations ayant marqué ce que nous appelons la pensée grecque et pourquoi se sont-elles produites dans ce monde grec ? Le mérite de Jean-Pierre Vernant est de réaliser une synthèse personnelle et accessible sur un sujet controversé où s'affrontent de nombreux hellénistes. Publié en 1962 dans la collection Mythes et religions, dirigée par Georges Dumézil, l'auteur a lui-même, à l'occasion d'une réédition parue vingt-cinq ans plus tard, réactualisé dans une longue préface certaines de ses interprétations (from the edition of 2013).

Jean-Pierre Vernant's concise, brilliant essay on the origins of Greek thought relates the cultural achievement of the ancient Greeks to their physical and social environment and shows that what they believed in was inseparable from the way they lived. The emergence of rational thought, Vernant claims, is closely linked to the advent of the open-air politics that characterized life in the Greek polis. Vernant points out that when the focus of Mycenaean society gave way to the agora, the change had profound social and cultural implications. "Social experience could become the object of pragmatic thought for the Greeks," he writes, "because in the city-state it lent itself to public debate. The decline of myth dates from the day the first sages brought human order under discussion and sought to define it.... Thus evolved a strictly political thought, separate from religion, with its own vocabulary, concepts, principles, and theoretical aims."

Jean-Pierre Vernant The Origins of Greek Thought, Cornell University Press, 1984

Jean-Pierre Vernant (1914-2007), known with the pseudonym Colonel Berthier as commander of units of the French resistance during WWII, was a French historian and anthropologist specialized in ancient Greece.

#jean pierre vernant#ancient greece#les origines de la pensée grecque#the origines of greek thought#classics

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

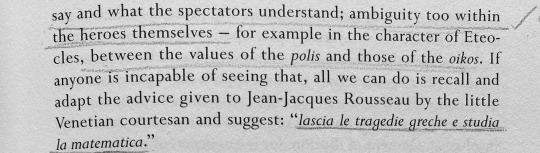

need to print these out for a greater agenda

#tagamemnon#book: myth and tragedy in ancient greece#by jean-pierre vernant and pierre vidal-naquet#insane how i thrifted this for 20bucks#in my attempt to avoid continuing my reads by arendt

1 note

·

View note

Text

🦉Athena Masterpost: Domains🦉

🐍 Masterpost Link 🐍

Last updated: Date of Publishing

Athena, Goddess of…

Metis

As a concept, metis could be translated and understood as meaning “practical wisdom”, “cunning”, “prudence”, “craftiness’ or “skill,” but it is often simply translated into “wisdom.” To many, this word conjures up the image of an old sage, a scholar surrounded by books and full of knowledge. But this was not how metis was conceptualized in ancient Greek culture.

Metis is “a complex but very coherent body of mental attributes and intellectual behaviour which combine flair, wisdom, forethought, subtlety of mind, deception, resourcefulness, vigilance, opportunism, various skills, and experience acquired over the years." It is an intelligence which is often associated with trickery and deception, adaptability, improvisation, shifting movement, shape-changing, quick thinking and seizing the opportunities at the right moment (kairos). Metis is more focused on getting practical results and success within an activity, not theoretical knowledge, and could be applied to many areas of life: "It may involve multiple skills useful in life, the mastery of the artisan in his craft, magic tricks, the use of philtres and herbs, the cunning strategems of war, frauds, deceits, resourcefulness of every kind."

Metis is also not limited to humans, but also applied to animals, such as foxes, fish and octopuses - animals with ‘cunning tricks’ (dolos) and deceptions that allow them to catch their prey or evade their predators. "The world of duplicity is also a world of vigilance: both the fishing frog squatting in the mud and the octopus plastered to its rock are on the alert; they keep a look out, are on the watch for the moment to act. Every animal with metis is a living eye which never closes or even blinks."

This was the kind of cunning we would associate today with the trickster archetype, not the book-loving sage. Athena was not the only deity to have metis (for example, Zeus is another major one) but this concept is a core part of who she is and influences her other associations and her connections with other deities.

Sources:

“Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society” - Marcel Detienne, Jean-Pierre Vernant

“Athena” - Susan Deacy

🐍Excerpts from “Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society”

Skill: Related to metis in that it’s very practical, with some intuitive sense but also dependent on experience and practice. This can be applied to many areas of life, though in Athena’s case it was often in relation to war, crafts, sailing and invention.

Crafts: Mainly associated with weaving, Athena was also worshiped in the festival of bronze smiths and artisans, Khalkeia. This aspect is very closely related to skill - as the word for both is ‘tekhne’ (τέχνη). This word is also one related to metis and associated words.

Invention: Athena is known as an inventor, with particular inventions being the bridle, plough and aulos. This aspect is also related to metis, craft and skill.

War: Although typically associated with the skills of war, and strategy, Athena was also associated with war in the same way that Ares was - she was ‘dreadful’ Athene “concerned with works of war, the sack of cities and the shouting and the battle.” (Homeric Hymn 11 to Athena)

🐍On the comparison of Athena and Ares

🐍Iliad - Athena dons the Aegis

Civilization, Politics & Justice: Athena in cult was often paired with Zeus, and these two presided over a number of civic institutions, for example the boule (a council that ran the daily affairs of the city) was watched over by Athena Boulaia and Zeus Boulaios. Athena was closely tied to the Athenian state and in myth was also heavily involved in the first criminal trial - that of Orestes.

Hero Mentorship: Athena was often involved in guiding, aiding and mentoring heroes such as Diomedes, Odysseus, Telemakhus, Herakles, Bellerophon and Perseus.

🐍Athena and Herakles Wedding Imagery

Education and Knowledge [SPG]: Athena’s modern associations with education and intelligence come from how she was adapted in post classical times as an allegorical symbol for church-approved virtues of wisdom and justice. The Renaissance furthered this connection, as she became a symbol of the arts, education, science, human excellence, and liberty.

Information Technology [UPG]: My personal UPG, based in part on Athena's associations with invention, civilization and knowledge, and in part on my own understanding of her character and my relationship and practice with her.

#Athena Masterpost#athena#Athena deity#Athena goddess#athena devotion#athena worship#helpol#hellenic polytheism#hellenic pagan#paganblr#hellenic polytheist

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is this sinister power of enragement that finds its rhythm in the flute, “the music of madness”? The tragic poet supplies the answer: “It is the Gorgon, daughter of Night, and her vipers with their hundred clamorous [iachemasin] heads; it is Lyssa of the petrifying gaze.”

— Jean-Pierre Vernant, The Medusa Reader, transl by Thomas Curley & Froma I. Zeitlin, (2013)

#French#Jean-Pierre Vernant#The Medusa Reader#Thomas Curley#Froma I. Zeitlin#(2013)#Euripides#Dionysos#Hades#Maenads#Satyrs#Silenoi#Phobos#♥

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek monster myths (1)

Various mini-articles loosely translated from the French « Dictionary of Feminine Myths », under the direction of Pierre Brunel. (You could also translate the title as “Dictionary of Female Myths” – the idea being all the myths centered around women)

Article 1: Gorgô

[Note: this mini-article is distinct from the mini-article about “Gorgons”]

The appearance of Gorgô, at the end of the eleventh chant of the Odyssey, is meant to cause fright – not just to Odysseus himself who is just done with invoking the dead, but also to the audience hearing this rhapsody (the Phaeacians listening to Odysseus’ tale), and to the very listener of the Homeric poem. Gorgô forms the dominant peak of this “evocation of the dead” (nekuia), she is the “chlôron déos”, the “green fear”. Odysseus’ mother, Anticleia, just disappeared back again nto the Hades – the hero wishes to summon other shades, such as those of Theseus and of his former companion Pirithous, “but before them, here is that with hellish cries the uncountable tribes of the dead gathered”. And Odysseus adds: “I felt myself becoming green with fear at the thought that, from the depths of the Hades, the noble Persephone might sent us the head of Gorgô, this terrible monster…” (633-635). It is barely an apparition, it is the possibility of an appearance, but it is enough to terrorize the living.

Jean-Pierre Vernant, in his work “La Mort dans les yeux” (Death in the eyes), establishes the link which ties together Gorgô and Medusa. Because Gorgô is more than a singular unification of the three Gorgons: she is a superlative form of Medusa, she is what happens when her petrifying gaze survives beyond death. By studying the depictions of Gorgô in ancient statues, Vernant establishes two fundamental traits: the faciality, and the monstrosity. He explains that “interferences” take place “between the human and the bestial, associated and mixed in diverse ways”. Maybe Gorgô is, as Vernant suggests, “the dark face, the sinister reverse of the Great Goddess, of which Artemis will most notably be the heir”. But Gorgô is also placed in the function of watchful guardian of the world of the dead, a world forbidden to the living. The mask of Gorgô expresses the radical alterity of Death and the dead.

Article 2: The Graeae

Daughters of Keto and Phorkys (they are thus also called “The Phorcydes”), sisters of the Gorgons, these divinities of shadows, which were born as elderly women and doomed to share one eye and one tooth for all three, appear exclusively in the tale of Perseus and Medusa.

The most ancient mention of the Graeae comes from Hesiod’s Theogony, which only counts two of them and names them Pemphredo and Enyo (Enyo was also the name of a goddess of war within Homer’s Iliad). The third of the sisters appears within a fragment of the Athenian logographer Pherecyde: Deino (“The Dreadful”), later called Persis by Hyginus (in his “Preface to fables”). Other authors, like Ovid, prefer to stick with two Graeae. Hesiod makes a quite flattering portrait of them: he makes them elegant goddesses with a “beautiful face”, even though they were “white-haired (understand “having white hair due to old age”) since birth”. And while their very name means “old women”, the Antique iconography actually follows the Hesiodic model: the depictions of the sisters as disfigured by the effects of time are quite rare… At most the artists will just put a few wrinkles. These mysterious hybrids between youth and old age, virginal seduction and sinister ugliness, finds an echo within a few lines from Aeschylus “Prometheus bound”: “Three ancient maidens, with swan bodies, that share a single eye and a single tooth, and who never receive a look from the shinng sun or the crescent of the night.” Aeschylus had an entire tragedy written about them (Phorcydes) which was unfortunately lost – but Aristotle wrote about it in his “Poetics” and implies that the play insisted on their monstrous aspect, placing them within the legendary area known as “the gorgonian fields of Kisthene”, and closely associating them with their sisters, of which they form a reversed image. Indeed, the Gorgons have a very powerful eyesight which no mortal being can face, while the Graeae have an extreme form of blindness. This trinity of women, old by nature, can also be understood as the antithesis of the three Charites, the Graces which embodied eternal youth.

The Graeae seems to have only a role within the myth of Perseus. And, outside of a few details, this legend does not change much from Pherecyde to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, passing by Lycophron, Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca, and Hyginus’ Astronomy. In all those versions the Graeae are the jealous keeper of the secret path that leads to the Gorgons, and Perseus must steal their eye in order to obtain the knowledge needed to reach Medusa. However, Pherecyde did change an element: according to him the Graeae do not protect the path leading to the Gorgons, but rather the path leading to the nymphs that hold the magical items Perseus needs to fight Medusa.

Due to their limited presence in Greek mythology, the Graeae have quite a poor cultural posterity. In the 19th century Goethe will remember them: in his “Second Faust”, Mephistopheles appears under the guise of “Phorkyas”, a monster with only one eye and one tooth. In the world of paintings, Edward Burne-Jones, who created a true “Perseus cycle”, had a strong interest for them: he worked for a very long time on a painting of the Graeae. Their face is barely visible, but the cloth that wraps itself around their body is menacing ; they are within an arid desert, under a dark sky heavy with clouds – they perform a sinister dance, in a mockery of the Graces. Perseus comes to steal their eyes, and the grey color that invades all the nuances of the picture symbolizes the unique presence of those strange crones, both disquieting and pitiable.

Article 3: Echidna

Echidna, “the viper”, is according to Hesiod the daughter of Phorkys and Keto, themselves born of Pontos, the Sea, and Gaia, the Earth. Echidna’s sisters are female monsters like her: the Graeae, and the Gorgons. Hesiod describes her as having half of the body of a “fair-cheeked nymph”, while the rest of her body is the one of an enormous, big, cruel, spotted and terrible snake which “lies within the secret depths of the divine earth”. Echidna as such belongs to this large mythological family of snake-women, of which the most famous case in France is the fairy Mélusine. But unlike Mélusine, Echidna can never leave the snake-half of her body, and thus a better French heir would be Marcel Aymé’s depiction of the vouivre with her cohort of vipers.

Theodore de Banville, when he imagines Hesiod scolding him for sanitizing Classical mythology, makes of Echidna the symbol of the archaic mythology: he tells him that he is “making a toy out of the history of the gods” by depicting Love as “a sweet child, free of carnivorous appetites, ignored by the Furies and by bloody Echidna”.

Echidna precisely appears as a being led by an amorous desire within Herodotus’ tales, that he claims to have collected among the Greeks of Pontus Euxinus: as Herakles was sleeping, Echidna steals his horses away. She only agrees to give them back if he sleeps with her. When Herakles leaves her, she tells him that she will bear three sons from their union. He advises them to only keep with her one that would be able to bend a bow just like him, and to force the others to leave. She does that, and this favorite son is supposed to be the one that created the Scythian people. This meeting between Herakles and Echidna might be derived from the famous encounters between Herakles and three of Echidna’s other children: the Nemean Lion, the Hydra of Lerna, and Cerberus.

In Aeschylus, Orestes compares his mother, Clytemnestra, to “a horrible viper”. Sophocles has Creon call Ismene, which he believes to have helped Antigone, “a viper that slid in my house against my will to drink my blood”. These examples show a link between the Ancient metaphorical speech, and the mythological allusions. Indeed, only the context can allow us to determine if these authors meant “viper” as a common name, or as a proper name: as “Viper”, “Echidna”. But it confirms the idea that, in Ancient Greece, Echidna is a monster born of an archaic fear of the women, and embodying their supposed perfidy.

#greek mythology#graeae#gorgon#gorgo#medusa#echidna#greek monsters#female monsters#ancient greek monsters#greek myths

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

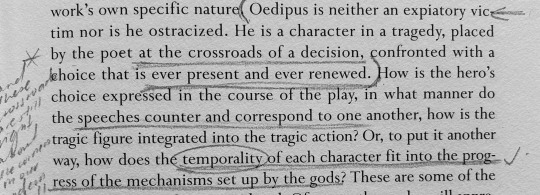

The sudden rise of the tragic genre at the end of the sixth century, at the very moment when law is beginning to elaborate the concept of responsibility by differentiating, albeit still in a clumsy and hesitant manner, the “intentional” from the “excusable” crime, marks, an important turning point in the history of the inner man. Within the framework of the city, man begins to try himself out as an agent who is more or less autonomous in relation to the religious powers that dominate the universe, more or less master of his own actions and more or less in control of his political and personal destiny. This still hesitant and uncertain experimentation in what was to become, in the psychological history of the Western world, the category of the will is portrayed in tragedy as an anxious questioning concerning the relationship of man to his actions: To what extent is man really the source of his actions?

Jean-Pierre Vernant, Myth and Tragedy in Ancient Greece, trans. Janet Lloyd

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

✦ A L T A L U N A & V A L E R I A N O ✦ Research

INTRODUCTION: "Corresponding to the human metis in Homer and the animal metis in Oppian [the fox & the octopus], in Hesiod we find the goddess Metis, the daughter of Tethys and Oceanus […] She is the first wife of Zeus, the wife he takes to bed as soon as the war against the Titans is brought to an end and as soon as he is proclaimed king of the gods, and thus this marriage crowns his victory and consecrates his sovereignty as monarch. There would, in effect, be no sovereignty without Metis. Without the help of the goddess, without the assistance of the weapons of cunning which she controls through her magic knowledge, supreme power could neither be won nor exercised nor maintained." - Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society by Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant

HOW SHE HELPED ZEUS WIN THE THRONE (Part 1): "When Zeus was grown, he engaged Okeanos' (Oceanus') daughter Metis as a colleague. She gave Kronos (Cronus) a drug, by which he was forced to vomit forth first the stone and then the children he had swallowed." - Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1. 6 (trans. Aldrich)

HOW SHE HELPED ZEUS WIN THE THRONE (Part 2): "Metis […] is the ‘foreseeing’ one who, knowing everything in advance, possesses that type of knowledge essential to anyone engaged in a battle whose outcome is still uncertain. Metis ‘knows more things than any god or mortal man." - Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society by Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant [Note: She is the foreseeing one because, by her cleverness, she is always three steps ahead, so to speak. She is not 'all-seeing' in the sense that she has a psychic ability to 'see' the future].

ZEUS TURNS ON METIS AND SUBSUMES HER GIFTS (Part 1): "Zeus, as king of the gods, took as his first wife Metis, and she knew more than all the gods or mortal people. But when she was about to be delivered of the goddess, gray-eyed Athene (Athena), then Zeus, deceiving her perception by treachery and by slippery speeches, put her away inside his own belly. This was by the advices of Gaia (Gaea, the Earth) and starry Ouranos (Uranus, the Sky), for so they counselled, in order that no other everlasting god, beside Zeus, should ever be given kingly position. For it had been arranged that, from her, children surpassing in wisdom should be born, first the gray-eyed girl, the Tritogeneia Athene . . . but then a son to be king over gods and mortals was to be born to her and his heart would be overmastering; but before this, Zeus put her away inside his own belly so that this goddess should think for him, for good and for evil." - Hesiod, Theogony 886 ff (Trans. Evelyn-White)

ZEUS TURNS ON METIS AND SUBSUMES HER GIFTS (Part 2): "Metis, inside Zeus’ belly, will make known to him everything that will bring him good or evil fortune.” - Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society by Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant

HOW SUBSUMED METIS HELPS ZEUS MAINTAIN POWER: “Forewarned of the danger that awaits him [the birth of a son that would supplant him on the throne], as his father was, he goes straight to the root of the evil […] Appropriating the wiles of Aphrodite, he treacherously seduces his wife with caressing words (haimulioisi logoisi), and having beguiled her wits by cunning (dolly phrase expatesas), he engulfs her within himself […] So this time Zeus was able to make the weapons which made the goddess invincible rebound against her, namely cunning, deceit and surprise attack. His victory eradicates forever from the course of time the possibility of any cunning trick which could threaten his power, by taking him by surprise. The sovereign Zeus is no longer, like Kronos or any other god, simply a deity who possesses metis [cunning]. He is metieta, the Cunning One, the standard gauge and the measure of cunning, the god himself becomes entirely metis." - Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society by Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant

CONCLUSION OR WHY ZEUS NEEDS METIS SO BADLY: In every confrontation or competitive situation - whether the adversary be a man, an animal or a natural force- success can be won by two means, either thanks to a superiority in ‘power’ in the particular sphere in which the contest is taking place, with the stronger gaining the victory; or by the use of methods of a different order whose effect is, precisely, to reverse the natural outcome of the encounter and to allow victory to fall to the party whose defeat had appeared inevitable. Thus, success obtained through mētis can be seen in two different ways. Depending on the circumstances, it can arouse opposite reactions. In some cases, it will be considered the result of cheating since the rules of the game have been disregarded. In others, the more surprise it provokes, the greater the admiration it will arouse, the weaker party having, against every expectation, found within itself resources capable of putting the stronger at his mercy. […] It [Mētis] is, in a sense, the absolute weapon, the only one that has the power to ensure victory and domination over others, whatever the circumstances, whatever the conditions of the conflict. - Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society by Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant

#greek mythology#Zeus#Metis#Cunning#research#writeblr#writeblr community#greek gods#greek myths#theogony#mythology#myth#no more sainted monsters#sainted monsters#sacred monsters

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wozu Kontrafakturen?

1.

Um anfangen zu können. Immer dann, wenn irgendetwas anfängt, dann fängt auch Recht an. Anzufangen ist eine juristische Technik und eine juridische Technik, dazu gibt es ganze Bibliotheken zur Geschichte des Anfangens, wie zum Beispiel Karl-Heinz Ladeurs Der Anfang des westlichen Rechts, Fritz Schulz' Prinzipien des römischen Rechts, Jean-Pierre Vernants Die Entstehung des griechischen Denkens oder Cornelia Vismanns Aufsatz zur Macht des Anfangs, in dem es so schön heißt, alle gelungenen Gründungen kämen zweimal vor. Sie bezieht das auf römische Institutionen und weist darauf hin, dass sie einmal wie privat, wie niedrig, klein und wie schwach angefangen haben - und einmal wie staalich, wie hoch, groß und stark. Das heißt nicht, dass erst mit dem Staat der Anfang gelingt, denn von Anfang an ist der Anfang der ganze Anfang und das Gelungene ein mimetischer Zug, dessen Stationen Halbwertzeiten haben.

2.

Das, was an unserem Tun einen Anfang markieren kann ist eine feine und scharfe Linie, in der Antike nachlebt, zum Beispiel das pomerium. Die normative Kraft des Kontrafaktischen liegt durchaus in Formen, also in etwas, aber sie ist ein Zug, ein Regerlein. Die kommt kräftig und schwach vor. Besser wäre es darum, man würde vom normativen Zug des Kontrafaktischen sprechen.

Vom Scheiden ist ein Schmuggel, mit dem ich nachgeholt habe, was in Regel und Fiktion schief ging. Damals tauchte die Formulierung von der normativen Kraft des Kontrafaktischen selbst als Kontrafaktur, als Referenz zu Georg Jellinek auf. Bazon Brock verwendete die Methode, der verkehrt jede Formulierung, um ihre Spannung zu begreifen und zu verstehen, was jemand vermeiden wil.

Regel und Fiktion ist hmpf, fängt an, aber nicht als Buch. Am besten gefällt mir in dem Text eine kleine Liste mit 4 Stufen zur Geschichte und Kosmologie der Fiktion - und das Foto eines Fähnleins Genüsse Steinhauer. Man kann sagen, dass das Verfahren leicht umstritten war, aber mal wieder Glück gehabt. Ging durch. Right now it's only a notion, but I think I can get the money to make it into a concept, and later turn it into an idea. Die Kontrafaktur ist dann aber doch noch, 15 Jahre später, ein Buch geworden, mit dem ich was anfangen kann. Das Cover ist Carl Schmitt in Stützstrumpfarbe, darüber war ich auch besonders glücklich, obwohl ich dem Verlag erst die Farbe Rosa vorgeschlagen hatte. Das wollten sie nicht. Erst dachte ich, die würden sich nicht trauen, jetzt traue ich ihnen einfach und benenne die Farbe beim Namen. Vorbild war unter anderem Schmitts Ex captavitate salus, da hat der Verlag die gleiche stumpfe Pappe und das weiße Zopfornament verwendet. Ist der Inhalt des Buches Dezisionismus? Ja, aber umgekehrt würde ich sagen.

2.

Die Kontrafaktur hat einen doppelten Sinn: Sie ist die Fabrik, aus der heraus Texte und Bilder enstehen, als seien sie vorher nicht in der Welt gewesen. Der zweite Sinn meint die einzelne Produktion, wie etwa das Buch vom Scheiden. Bei der Anfertigung kommen Gelegenheiten und Gegebenheiten zusammen, etwas davon hält man wie in der Hand, der Rest kommt von alleine. Das Kontrafaktische kann des Fiktive oder das Artifizielle, das Künstliche oder Kunstvolle eines juristischen Textes genannt werden, andere Bezeichnungen sind auch möglich. Für einen Umgang mit dem Kontrafaktischen empfiehlt es sich, darauf zu achten, was ein Text kreuzt und was er austauscht. Kontrafakturen sind widerständig und insistierend, auch dem Autor, man hat den Einsatz nicht souverän in der Hand. Die Kontrafaktur zieht sich kapillar durch den ganzen Text, würde man sie Grundnorm nennen, wäre sie eine Tafel, auf der der gesamte Texte steht, und die damit nicht nur am Anfang des Textes vorkommt, sondern den ganzen Text durchzieht.

Das Buch ist schon alt. Inzwischen würde ich, wenn ich etwas zu Kulturtechnikforschung sagen möchte, die Bild- und Rechtswissenschaft ist, vom Scheiden, Schichten und Mustern sprechen. Die Techniken des Scheidens sind zum Beispiel allen logischen Operationen der Unterscheidung assoziiert, allen Verfahren und Stragien, etwas zu entscheiden zu bescheiden, oder zu verabschieden, etwas zu bescheiden, zu definieren, zu präzisieren oder etwas als Montage zu präsentieren. Juristen könnten mit dem Vokabalur fremdeln, o.k. so, so soll es sein, insoweit handelt es sich bei der Antrittsvorlesug von 2015 um eine formalistische Arbeit. Weil ich mich aber auch mit Geschichte und Stratifikaton befasse, müsste ich einen zweiten Band zum Schichten schreiben. Und weil ich mich mit Bildern, dabei unter anderem der magischen Rationalität, vaguen und voguem Assoziatione bei Warburg befasse, müsste es einen dritten Band zum Mustern geben. Ich würde bei Censoren anfangen, den Haruspizen, und bei Armin Nassehi aufhören.

3.

Man kann sich die Kontrafaktur als eine Linie und einen Zug vorstellen, als Tragendes und Trachtendes eines juristischen oder juridischen Objektes (zum Beispiel einer Norm, eines Textes oder eines Bildes). Die Kontrafaktur stellt das Objekt her und stellt es dar. Die Kontrafaktur lässt Texte nicht nur so schreiben, als seien sie bisher nicht geschrieben gewesen. Sie lässt Texte auch so schreiben, als sei alles in dem Text schon so in der Welt gewesen und würde nun nicht verrückt. Schreiben, als ob man abschriebe und abschreiben, als ob man schreibe: Diese Kreuzung und der Austausch ist der kontrafaktische Zug juristischer und juridischer Objekte. Das vergleiche ich mit Vismanns Texten zum Canceln. Ich vergleich das auch mit Ino Augsbergs Arbeiten zum Versäumen, mit Pottages Arbeiten zur Involution, zur Einfaltung - und sicher auch, Bingo!, mit Warburgs Gestellschieberei. Machen tun es alle, die genannten explizieren es aber deutlicher.

Die Kontrafaktur lässt sogar einen Text so schreiben, als käme nicht drin vor, was der Autor vermeiden will. So kommen zum Beispiel alle Arbeiten von Cornelia Vismann in den Medien des Rechts von Thomas Vesting vor, es sind aber Linien eingezogen, die den Text so stellen, als käme sie nicht drin vor. Wäre das Buch von Vismann später, die von Vesting früher erschienen, müsste man an beiden Büchern nichts ändern, die Kontrafaktur arbeitet auch so - und liesse den Text von Vismann so lesen, als dringe sie in Denkräume vor, wo Vestings Denken nicht vorkäme. Anders herum ist es auch so.

Die Kontrafakturen haben eine logische Geschichte, wissenschaftshistorisch sind sie zum Teil der Logik und Dialektik und der Paradoxie geworden. Sie haben aber überall Geschichte, nicht nur in der Logik. Sie kommen auch diagonal/durchgehend kantig, eckig, zügig oder schwillend vor, durchgehend winkelig und winkelnd. In der Graphik und der Choreopgraphie haben sie ein lange Geschichte, des pomerium ist ein Teil dieser Geschichte.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

access to higher education is so limited in america so I'm gonna make a google drive full of the resources I'm given at my university I still have access to. For what I no longer have access to, I'll just post a list of books, articles, poems, ect from the course. Granted it's gonna be a lot of political theory and history but like its some cool stuff.

starting off,

A Brief History of Fascist Lies by Federico Finchelstein (my actual professor. this book is fantastic)

Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin Burrows

No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920 by T.J. Jackson Lears

City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920 by Timothy Gilfoyle (literally so fascinating)

Myth and Thought among the Greeks by Jean-Pierre Vernant

Mortals and immortals by Vernant

Moon, Sun and Witches: Gender Ideologies and Class in Inca and Colonial Peru by Irene Silverblatt

Gilded City: Scandal and Sensation in Turn-of-the-Century New York by M.H. Dunlop

Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City by Carla Peterson

#education#history#politics#political theory#history of new york#books#seriously read the first book! its so good!

11 notes

·

View notes