#Japanese Language

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

帰

音読み おんよみ キ

訓読み くんよみ かえ(る)、かえ(す)、おく(る)、とつ(ぐ)

英語 えいご homecoming, arrive at, lead to, result in

君は9時前に帰らなければならない。 きみ は くじ まえ に かえらなければならない。 You must come home before nine o'clock.

#日本語#japanese#japanese language#japanese langblr#langblr#studyblr#漢字#常用漢字2年生#kanji#joyo kanji year 2#joyo kanji#tokidokitokyo#tdtstudy

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

神 (kami) “god”/“divine spirit”

Often translated as “god”, a Japanese kami is closer to the concept of a spirit.

They are (mostly) not considered to be omniscient nor omnipotent, but rather they influence the human world within a certain capacity.

They are believed to be manifestations of musubi, the interconnecting energy of the universe.

It is often said that in Japan there are 8 million kami. Some of the more well known are Amaterasu-o-mi-kami the sun goddess, Inari the rice god/dess (their gender depends on their aspect), and Ebisu the god of wealth and commerce.

In the Ghibli movie “Spirited Away”, the main character Chihiro finds herself working in a bathhouse for some of these kami.

(Fact for language geeks: The original Japanese title of the Ghibli movie “Spirited Away” uses the word 神隠し kamikakushi - literally “hidden by kami”.)

Whether or not most people actually believe in kami is unclear, but it seems that many people believe in luck and unseen forces. Certainly the shrines are crowded at New Years time, and also at the start of the new financial year when many business people queue to pray to Ebisu.

#japanese language#japan#japanese culture#japanese#書道#japanese calligraphy#calligraphy#japanese art#kanji#japanese langblr

31 notes

·

View notes

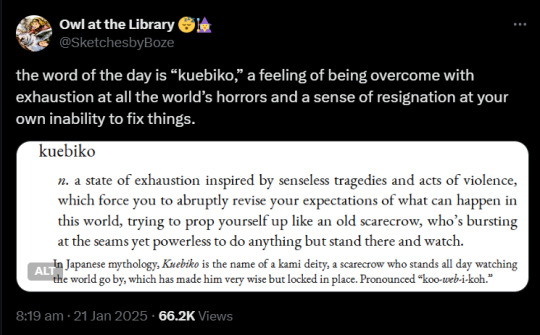

Text

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

🐞 Saturday, April 26th. Today is the 116th day of 2025. May you have a Saturday full of compassion🖐😊

🌸:❀.。o °・:こんにちは 世界 ..。o °・❀:🌸. ・・・ Konnichiwa sekai ・・・ 💙Hello World🩵

Merhaba Dünya🐞 Buongiorno Mondo🌷 Bonjour tout le monde☘️

.。o °・❀:🌸..。o °・❀:🌸..。o °・❀:🌸.

4月26日、土曜日。 今日は2025年の116日目。 思いやりに満ちた土曜日でありますように。

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

here are a few podcasts I listen to weekly for practice!

Japanese with Teppei and Noriko

short, concise episodes covering various topics! easy to follow along!

Let's Learn Japanese from Small Talk

longer more detailed episodes with very casual Japanese! they explain some of the vocab they use while speaking (especially slang) and have a vocab list at the end that they go over with a link to read along!

Japanese with Kanako

great for shadowing practice with a few listening exercises mixed in. perfect if you are using the genki series!

what are some podcasts you like to listen to? 教えてください!😊

943 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let me try this

So let the wheel decide your Japanese first-person pronoun

Note: descriptions may be inaccurate.

#attempts at socializing#polls#spin the wheel#random wheel#Japanese pronouns#linguistic#Japanese#Japanese language#I got [insert your name here]#I don’t like my legal name so I don’t like it

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

LSD Dream Emulator Playstation 1998

#gaming#video games#retro gaming#nostalgia#aesthetic#90s#1990s#low poly#lsd dream emulator#lsdem#ps1#psx#psone#playstation#sony#surreal#eerie#ominous#creepy#liminal#liminalcore#dreamcore#oddcore#liminal spaces#japanese#japanese language#kanji

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know that the english word “star” and the japanese word 星(ほし)don’t actually mean the same thing?

Language does not simply name pre-existing categories; categories do not exist in 'the world'

— Daniel Chandler, Semiotics for Beginners

I read this quote a few years ago, but I don’t think I truly understood it until one day, when I was looking at the wikipedia article for “star” and I thought to check the Japanese article, see if I could get some Japanese reading practice in. I was surprised to find that the article was not titled 「星」, but 「恒星」, a word I’d never seen before. I’d always learnt that 星 was the direct translation for “star” (I knew the japanese also contained meanings the english didn’t, like “dot” or “bullseye”, but I thought these were just auxiliary definitions in addition to the direct translation of “star” as in "a celestial body made of hydrogen and helium plasma").

To try and clear things up for myself, I searched japanese wikipedia for 星. It was a disambiguation page, with the main links pointing to the articles for 天体 (astronomical object) and スター(記号)(star symbol). There was no article just called 「星」.

It’s an easy difference to miss, because in everyday conversation, 星 and star are equivalent. They both describe the shining lights in the night sky. They both describe this symbol: ★. They even both describe those enormous celestial objects made of plasma.

But they are different - different enough to not share a wikipedia article. 星 is used to describe any kind of celestial body, especially if it appears shiny and bright in the night sky. “Star” can be used this way too (like Venus being called the “morning star”), but it’s generally considered inaccurate to use the word like this, whereas there is no such inaccuracy with 星. You can say “oh that’s not actually a star, it’s a planet”, but you CAN’T say 「実はそれは星ではなく惑星だよ」 (TL: that’s not actually a hoshi, it’s a planet). A planet IS a 星.

星 is a very common word, essentially equivalent to “star”, but its meaning is closer to “celestial body”. I haven’t looked into the etymology/history but it’s almost like both english and japanese started out with a simple, common word for the lights in the sky - star/星 , but as we found out more about what these lights actually were, english doubled down on using the common word for the specific scientific concept, while japanese kept the common word generic and instead came up with a new word for the more specific concept. If this is actually what happened, I’d guess that kanji probably had something to do with it - 星 as a component kanji exists inside the word for planet, 惑星, and in the word for comet, 彗星, and in the scientific word for “star”, 恒星, so it makes sense that it would indicate a more general concept when used standalone.

This discovery helped me understand that quote - categories don’t exist in the world, we are the ones who create them. I thought that the concept of “star” was something that would be consistent across all languages, but it’s not, because the concept of “star” is not pre-existing. Each language had to decide how to name each of those similar star-like concepts (the ★ symbol, hot balls of gas, twinkling lights in the sky, planets, comets, etc), and obviously not every language is going to group those concepts under the same words with the same nuance.

Knowing this, one might be tempted to say that 恒星(こうせい) is the direct translation for “star”. But this isn’t true either. In most of the contexts that the word “star” is used in english, the equivalent japanese will be simply 星. Despite the meanings not lining up exactly, 星 will still be the best translation for “star” most of the time. This is the art of translation - knowing when the particulars are less important than the vibe or feel of a word. For any word, there will never be an exact perfect translation with all the same nuances and meanings. Translation is about finding the best solution to an unsolvable problem. That's why I love it.

#translation#japanese#japanese language#learning japanese#language#langblr#language learning#semiotics#linguistics#japanese vocab#jimmy blogthong#official blog post

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

#japanese#learning japanese#langblog#japan#langblr#japanese vocab#anime#manga#tumblr language#japanese vocabulary#shinto#japanese shrine#shrine#kanji practice#kanji#hiragana#japanese fashion#japan travel#japanese language#japan girl#shrine maiden#kyoto#tokyo#nihongo#jjk#inuyasha

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuebiko (久延毘古) is the Shinto kami of folk wisdom, knowledge and agriculture, and is represented in Japanese mythology as a scarecrow who cannot walk but has comprehensive awareness.

[x]

768 notes

·

View notes

Text

火火火火火火火火火火火火火火火火

火炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎火

火炎焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱炎火

火炎焱燚燚燚燚燚燚燚燚燚燚焱炎火

火炎焱燚 this 燚焱炎火

火炎焱燚 is 燚焱炎火

火炎焱燚 fine 🐶 燚焱炎火

火炎焱燚燚燚燚燚燚燚燚燚燚焱炎火

火炎焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱焱炎火

火炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎炎火

火火火火火火火火火火火火火火火火

#meme#japanese language#Japanese#kanji#漢字#visual poetry#text#japanese text#this is fine#ascii art#chinese characters

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

In Japanese language, describing a third person’s emotion is different from describing a first person’s emotion: in English, the sentences "I am happy" and "He is happy" are grammatically structured in the same way. However, in Japanese, this direct equivalence is not possible: you can say "私は嬉しいです" (Watashi wa ureshii desu), but you can't simply say "彼は嬉しいです" (Kare wa ureshii desu).

This is due to cultural and linguistic nuances that emphasize the acknowledgment of another's internal state as somewhat inaccessible. In fact, Japanese typically employs expressions that convey a level of inference or indirectness, such as:

Using observational phrases: one might say 「彼は嬉しそうです」 (Kare wa ureshisō desu), which translates to "He seems happy" or "He/she looks happy." This phrasing respects the notion that one can only observe outward signs of emotion, not definitively know another's internal state.

Adding "ようだ" or "みたい": these suffixes add a sense of speculation. For example, 「彼は嬉しいようだ」 (Kare wa ureshii yō da) or 「彼は嬉しいみたいです」 (Kare wa ureshii mitai desu), both meaning "He appears to be happy."

Using conditional clauses: Another approach is to use conditional forms, like 「彼が嬉しければ」 (Kare ga ureshikereba), meaning "If he is happy," which implicitly acknowledges the uncertainty of truly knowing his feelings.

One characteristic of Japanese syntax is its extreme sensitivity to epistemological considerations based on the ego/nonego distinction or the distinction of I/the other. Our knowledge about the mental state of another person must necessarily come from our interpretation of external evidence, and this is well reflected in the Japanese language.

Source material: http://human.kanagawa-u.ac.jp/gakkai/publ/pdf/no157/15712.pdf

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

sunday study sesh— wishin for fall 🍂

#studyblr#study blog#langblr#langblog#japanese langblr#japanese language#japanese#studyinspo#study motivation#study aesthetic

592 notes

·

View notes

Text

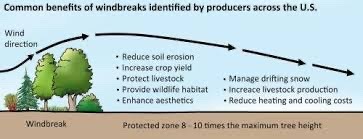

I will forever appreciate a theme in my fictional stories, & that’s exactly what Wind Breaker (by Nii Satoru) has, so, I present:

Wind Breaker characters have a theme to their names.. a thread:

Bōfūrin / 防風鈴

so, even though our protag group’s name is written and visually represented as “wind chime”, Bōfūrin’s name is where this group’s theme of trees/plants start:

防風鈴 (“prevent/protect” “wind chime”) has the same reading as 防風林, a type of forest planted strategically to prevent wind erosion of soil — much like Fūrin’s mission of protecting and serving their town

all of Bōfūrin’s named members (and close associations) so far have some element of tree/plant/wood in their last name (if you look at the kanji of their last names, you’d see a lot of wood radicals/木字旁):

桜 遥 • Sakura Haruka: 桜 / cherry tree

(fun fact: his name 遥 / haruka means "far"; also it's commonly a feminine given name)

蘇枋 隼飛 • Suō Hayato: 枋 / sandalwood (?) or tree used as timber, general term for wooden beams in houses

(fun fact: his last name 苏枋 is the Chinese name of a traditional reddish brown color, named after a pigment made from 苏木!)

楡井 秋彦 • Nirei Akihiko: 楡 / Siberian elm

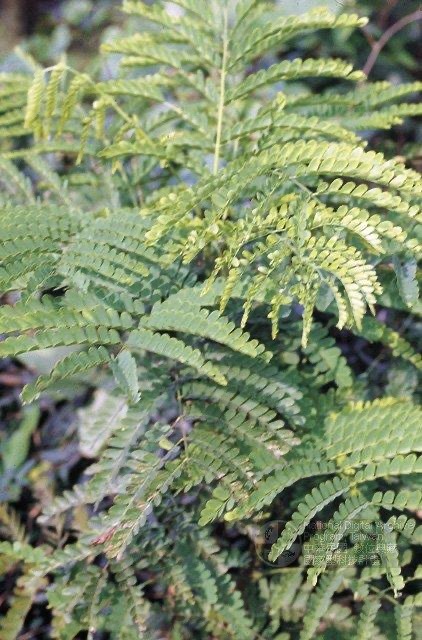

杉下 京太郎 • Sugishita Kyōtarō: 杉 / Japanese cedar (cryptomeria japonica)

柊 登馬 • Hiiragi Tōma: 柊 / holly osmanthus (osmanthus heterophyllus)

(fun fact: his name 登馬 means "to mount a horse"; no, not that kind of mount, the regular horseback riding kind)

梅宮 一 • Umemiya Hajime: 梅 / plum tree

(fun fact: his name 一 is just "one")

This association also extends to Kotoha, who is very closely associated with Bōfūrin:

橘 琴叶 • Tachibana Kotoha: 橘 / orange tree

now, Bōfūrin members yet to be featured in the show: (spoilers below the break)

(if you want to go to later parts: part 2 - shishitoren & part 3 - noroshi!)

梶 蓮 • Kaji Ren: 梶 / paper mulberry (broussonetia papyrifera)

(fun fact: his name 蓮 / Ren means "lotus")

椿野 佑 • Tsubakino Tasuku: 椿 / Japanese camellia

(fun fact: their name 佑 means "to help/protect" or "to bless"!)

桐生 三輝 • Kiryū Mitsuki: 桐 / empress tree (paulownia tomentosa)

柘浦 大河 • Tsugeura Taiga: 柘 / mandarin melon berry (maclura tricuspidata)

There's also 桃�� 匠 (Momose Takumi, "peach tree") & 水木 聡久 (Mizuki Saku, "wood"), the two other Heavenly Kings

I hope I have rly driven the point home here,, /lh

#wind breaker#wind breaker nii satoru#wind breaker anime#wind breaker manga#bofurin#sakura haruka#suo hayato#nirei akihiko#sugishita kyotaro#haruka sakura#hayato suo#kyotaro sugishita#hiiragi toma#toma hiiragi#umemiya hajime#hajime umemiya#kotoha tachibana#tachibana kotoha#kaji ren#ren kaji#tsubakino tasuku#tasuku tsubakino#kiryu mitsuki#mitsuki kiryu#tsugeura taiga#taiga tsugeura#language stuff#japanese language#wind breaker deepdive#yovo yaps

862 notes

·

View notes

Text

[vocabulary] サシで? 🥺 *pangs of jealousy*

Here’s a neat little phrase I stumbled across recently.

I was telling a Japanese friend that I'm going out for a meal with another friend, and he dropped this on me:

サシで?

I had no idea what it meant, so I asked. Turns out, サシ comes from 差し向かい, which means “face to face.” So when someone asks 「サシで?」, they’re basically saying, “Just the two of you?”

It is used with the で particle, like in:

サシで飲む to have a private drink

or

サシで話す to talk one-on-one

From サシで飲む also comes the noun サシ飲み (a private drink), which seems to be pretty common.

It can also be written in kanji as 「差し」.

Now you can ditch your 二人きり and use サシ instead to impress your Japanese friends ;)

316 notes

·

View notes