#Iranology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

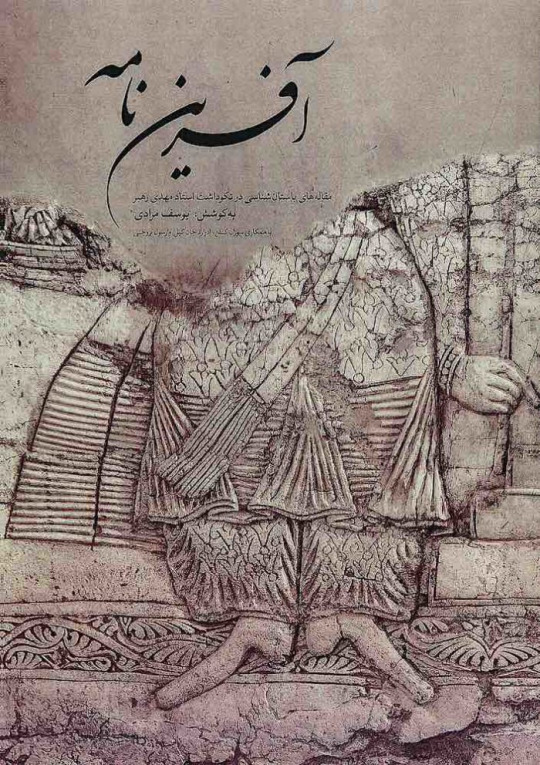

Afarin Nameh: Essays on the archaeology of Iran in Honour of Mehdi Rahbar; Āfrīnʹnāmah

آفریننامه: مقالههای باستانشناسی در نکوداشت استاد مهدی رهبر

Editors: Yousef Moradi, with the assistance of Susan Cantan, Edward J. Keall and Rasoul Boroujeni

Publisher: The Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism (RICHT), Tehran, 2019

Table of contents of English section

Antigoni Zournatzi: “Travels in the East with Herodotus and the Persians: Herodotus (4.36.2-45) on the Geography of Asia” Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis: “From Mithradat I (c. 171-138 BCE) to Mithradat II (c. 122/1-91 BCE): the Formation of Arsacid Parthian Iconography” D.T. Potts and R.P. Adams: “The Elymaean bratus: A Contribution to the Phytohistory of Arsacid Iran” Vito Messina and Jafar Mehr Kian: “Anthrosol Detection in the Plain of Izeh” Rémy Boucharlat: “Some Remarks on the Monumental Parthian Tombs of Gelālak and Susa” Edward J. Keall: “Power Fluctuations in Parthian Government: Some Case Examples” Bruno Genito: “Hellenistic Impact on the Iranian and Central Asian Cultures: The Historical Contribution and the Archaeological Evidence.” Pierfrancesco Callieri: “A Fountain of Sasanian Age from Ardashir Khwarrah” Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi: “The Gravity of New City Formations: Change in Settlement Patterns Caused by the Foundation of Gondishapur and Eyvan-e Karkheh” St John Simpson: “The Land behind Rishahr: Sasanian Funerary Practices on the Bushehr Peninsula” Barbara Kaim: “Playing in the Temple: A Board Game Found at Mele Hairam, Turkmenistan” Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Jebrael Nokandeh and Davit Naskidashvili: “The Great Walls of the Gorgan Plain Explored via Drone Photography” Jens Kröger: “The Berlin Bottle with Water Birds and Palmette Trees” Carlo G. Cereti: “Once more on the Bandiān Inscriptions” Gabriele Puschnigg: “East and West: Some Remarks on Intersections in the Ceramic Repertoires of Central Asia and Western Iran” Matteo Compareti: ““Persian Textiles” in the Biography of He Chou: Iranian Exotica in Sui-Tang China” Ritvik Balvally, Virag Sontakke, Shantanu Vaidya and Shrikant Ganvir: “Sasanian Contacts with the Vakatakas’ Realm with Special Reference to Nagardhan” Antonio Panaino: “The Ritual Drama of the High Priest Kirdēr” Touraj Daryaee: “Khusrow Parwēz and Alexander the Great: An Episode of imitatio Alexandri by a Sasanian King” Maria Vittoria Fontana: “Do You Not Consider How Allāh … Made the Sun a Burning Lamp?” Jonathan Kemp and John Hughes: “Analysis of Two Mortar Samples from the Ruined Site of a Sasanian Palace and Il-Khānid Caravanserai, Bisotun, Iran”

I found on the net the following abstract of the contribution of Antigoni Zournatzi to this volume, having as subject the Persian sources of Herodotus concerning the geography of Asia, although unfortunately for the moment I don't have access to the paper itself and more generally to this very interesting volume:

This paper considers a description of Asia in the work of Herodotus—a description that quite evidently further had implications for the manner in which this Greek historian perceived the shape and order of magnitude of the territories of Europe and Asia, as well as the overall form of the ‘inhabited’ world (oikoumenē). It supports the idea of a close affinity of Herodotus’ views in this instance with ancient Persian ways of looking at the world. Indications that Herodotus’ picture of Asia—and hence, his views about the form of the ‘inhabited’ world that are based upon this picture—must emanate from official Persian definitions of their realm derive, on the one hand, from the general coincidence of Herodotus’ Asia with Persian territorial realities, and on the other hand, from significant convergences that can be traced between Herodotus’ representation of the Asiatic continent and the Persians’ own perceptions and representations of their imperial domain.

Mehdi Rahbar is leading Iranian archaeologist.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

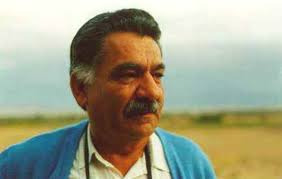

From Ferdowsi to the Seljuk Turks, Nizam al Mulk, Nizami Ganjavi, Jalal ad-Din Rumi & Haji Bektash

By Prof. Muhammet Şemsettin Gözübüyükoğlu (Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis)

Pre-publication of chapter XXIII of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”; chapter XXIII constitutes the Part Nine (Fallacies about the Golden Era of the Islamic Civilization). The book is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters.

----------------------------------------------------

Read and download the chapter here:

#Ferdowsi#Seljuk Turks#Seljuk#Seljuq#Nizam al Mulk#Nizami Ganjavi#Jalal ad-Din Rumi#Haji Bektash#Gözübüyükoğlu#Shamsaddin Megalommatis#Megalommatis#Orientalism#Iranology#Turkology#Iranian Studies#Anatolia#History of Islamic Anatolia#Islamic Iran#Islamic Studies#Islamology#Tus#Khorasan#Shahnameh#Messianism#Eschatology#Soteriology#Muhammad ibn al-Askari#Twelfth Imam#Islam#Sunni

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Iranology - Talesh 3 | ایرانشناسی، تالش 3

1 note

·

View note

Photo

annemarie schimmel (d. 7 Nisan 1922 - ö. 26 Ocak 2003), iranolog, oryantalist ve islam-tasavvuf araştırmacısı.

islamın mistik boyutları, tasavvuf tarihini anadolu'dan, kuzey afrika'ya, arap yarımadasından, iran ve uzakdoğu'ya kadar geniş bir coğrafya içinde ele alıyor. tasavvufla ilgili derli toplu bilgi sahibi olmak isteyenler için ‘’bilimsel’’ bi kaynak. ufak tefek eleştirdiğim, ‘’ımm nası yani’‘ dediğim noktalar var ama en önemlisi ‘‘la ilahe illlallah’‘ı ‘’allah’tan başka tanrı yoktur’’ olarak çevrilmiş olması oldu.-yani bi kişi tanrı gibi.- ( ilah/tanrı yok, sadece allah ) yaklaşık yüz sayfalık kaynakçası olan kitap beş yüz otuz sayfa. yalın bi dili var, çok hoş.

bu kitaptan çok çok daha fazla beğendiğim islam metafizinde tanrı ve insan’ı okumanızı da tavsiye ederim, mevzular arabi eksenli ama yine de o kitaptan öğrendiklerim çok daha ufuk açıcı olmuştu. bu kitaptan sonra okunsa çok daha yerinde olur gibi.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

First Selection List of PG Diploma in Iranology is out. Session 2019-20. Result Link: www.jmicoe.in ~Link in the Bio ~Date: 10-07-2019. ~Message us for any queries ~ WhatsApp us at: 9891526930 ©Blog.jmientrance.com #Jamia #Result #JMI #JMIEntrance #jamiamilliaislamia #centraluniversity #jamiamilliaislamiauniversity #notice #instagram #india #newdelhi (at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bzv28vLn1o8/?igshid=6o5fni8jf2jx

#jamia#result#jmi#jmientrance#jamiamilliaislamia#centraluniversity#jamiamilliaislamiauniversity#notice#instagram#india#newdelhi

0 notes

Text

Zazaca Edebiyata Kısa Bir Bakış

Zazaca Edebiyata Kısa Bir Bakış

Seyîdxan Kurij E-mail: Filit@gmx. de

Giriş

Öncelikle Zazaca`yı Kürtçe` den ayrı düşünmediğimi, Kürtçenin içinde bir lehçe olarak gördüğümü belirteyim. Çoğu zaman bilerek veya bilmeyerek Kürtçe denince özellikle Kuzey Kürdistan’da ve Türkiye’de hemen akla Kurmanca lehçesi geliyor. Oysa bu anlayış ve bu bakış açısı doğru değildir. Kuzey Kürdistan’da gerek Kürt aydınları arasında…

View On WordPress

#“Tîrêj dergisi#Başka Edebiyat#Kürt Edebiyatı#Kürt kadın yazarlar#Kürtçe yazılık eserler#Modern zazaca edebiyatı#Neyya Nükhet Eren Yaratıcı Yazarlık Atölyesi#Neyya yaratıcı yazarlık#Peter Lerch#Seyîdxan Kurij#zazaca#zazaca edebiyat#zazaca metin#İranolog Oscar Mann

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some thoughts on the debate about the Persian Empire, the ancient Greek Classical authors, and the “New Achaemenid historians”

The debate between the “New Achaemenid historians” and their critics is very interesting, as it has not only scholarly, but also ideological implications. So, here are my thoughts about it:

1/ I agree that one should not see today the Persian Empire exclusively through the eyes of the ancient Greeks and that the civilization of ancient Iran deserves fully to be studied for its own importance and merits, not just as some kind of historical opposite of the Greek civilization (this is I think particularly true not only concerning the political and social history of ancient Iran, but also and perhaps above all concerning the very interesting intellectual developments linked with the formation, expansion, and consolidation of the great Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism). On the other hand, there is a wealth of information on the Achaemenid Empire in the Classical Greek sources and it would be a serious loss if these sources were simply discarded from the historiography of ancient Persia for essentially ideological reasons. Moreover, the Iranian record is so fragmentary and selective that, without the Greek sources, we would have had practically no knowledge not only about the Persian Wars and other wars of the Achaemenids in the West of their empire, but also about very important events of the domestic history of Persia, like the serious crises after the deaths of Artaxerxes I and of Darius II. We should not forget also that, in the cases in which events of the Persian history described by the Greek sources are also described by extant non-Greek sources, despite some differences the non-Greek sources tend to confirm what the Greek sources say, as it happens for example with the events from the last year of Cambyses to the consolidation of the power of Darius in Herodotus and in the Behistun inscription, or with the murder of Xerxes in the Greek and Babylonian sources. This confirmation, although partial, corroborates more generally the reliability of the Greek sources on ancient Persia.

2/ Of course the Greek sources are not totally unbiased toward the Persian Empire. But the Iranian sources are not unbiased either, as they are dominated by Achaemenid royal ideology and propaganda. The same is true with other non-Greek sources, mainly Egyptian and Babylonian, which mostly express the attitudes of the local elites toward the Persian rule, attitudes either of eagerness to collaborate with the Persian masters or, on the contrary, of covered criticism toward them.

To return to the Greek biases, obviously most Greek authors see the Persian Empire from outside (with the exception of Ctesias, who lived for some years in the Persian court, and partially of Xenophon, who was for a brief period of time mercenary in the army of the wannabe usurper of the Persian throne Cyrus the Younger). Therefore, they don’t have experience of the inner functioning of the Empire and of the Persian heartland. Moreover, the cultural differences between Greeks and Persians were the cause of not few confusions and misunderstandings in the “translation” of information from the one culture to the other. But of course the most important cause of negative biases toward Persia in the Greek sources is the antagonism between Persians and Greeks, an antagonism caused by the expansionism of the Persian Empire and its efforts first to subjugate and, after the failure of this attempt, to divide and control the Greek city-states. From this point of view, the Greek attitudes toward the Persian Empire have, despite their biases, their value, as they express the outlook on the Achaemenid Empire of a people who managed to resist the Achaemenid expansionism. Or perhaps should we reject more generally as prejudiced and valueless what peoples who managed to resist powerful empires have said and preserved about these empires? But I think that it would be absurd and historically dangerous to adopt such a position.

Moreover, there is not just prejudice in what the Greek sourses say about the Persian Empire and the Persians as people. The ancient Greeks of the Classical era were a people who appreciated knowledge, but also a people having the intelligence to understand that it is better to know your enemy or adversary. That’s why there is often in the Greek classical sources a serious attempt to convey genuine information, to clarify things, and to understand the Persians and their empire. The seriousness of such endeavors varies of course in each author, and for instance Herodotus’ engagement with the Persians as historian of the rise of the Persian Empire and of the Persian Wars is much more serious than that of Isocrates, orator and propagandist of Panhellenism and of a Greek campaign of conquest of Asia. Of course, even in Herodotus unreliability of intermediaries and cultural differences cause in several cases distortions in the transmission of information from Persian sources. But even in these cases most often a kernel of truth is preserved and there is the possibility of reconstruction of a better image, through combination and comparison of what Herodotus says with what results from other, non-Greek sources.

3/ The ideological underpinning of the efforts of the “New Achaemenid historians” is a negative view on the ancient Greeks as forefathers of the racism and colonialism of the modern era, the purported need of de-hellenization and decolonization of the historiography of ancient Persia, and the supposed collective guilt of the field of Classics for the propagation of racist and imperialist ideas in history.

But, first of all, all these notions about the roots of modern colonialism and racism in ancient Greece are for many reasons unfounded. The Greeks were the people of the Antiquity the most intellectually engaged with the foreigners, going beyond the caricature and vilification which so often characterized the picture of the foreigner in other civilizations like Egypt and Babylonia, and, even if one can find proto-racist aspects in some Greek sources, such attitudes are far from being found only among the Greeks (expression of racist mentalities toward foreigners is for instance so frequent in the official Pharaonic record). Moreover, the engagement of the Greeks with the non-Greeks was something far more complex than just the expression of a superiority complex and of snubbish rejection, as the most superficial reading of Herodotus can show. On the other hand, Western colonialism and racism of the modern era have their roots in the interests and mentalities of Western European nations and it would be ridiculous to admit that slavers and colonizers have chosen their path of action because they were assiduous readers of the Greek classics (it is another question that intellectual proponents of racism, colonialism, and modern slavery have tried to appropriate the Greek heritage for their own reasons). Anyway, I find unscholarly the rejection of the ancient Greek classics as historical source on the ground of purely ideological and unfounded reasons, of the type that the Greeks would be the inventors of racism and colonialism...

To return to our more specific subject, the purpose of some to “decolonize” the historiography of ancient Persia through the rejection of the ancient Greek sources is a bizarre inversion of the historical reality. I say this because obviously the Greeks of the classical era (before Alexander) did not try to colonize Persia and most Greek classical sources reflect either the fight of the Greek city-states to maintain their freedom face to the Persian imperial expansion, or its historical aftermath. It would be thus ridiculous to read the Greek accounts of the Persian Wars as colonial history (with the Greek as colonizers and the Persians as colonized!). On the contrary, the story of this fight of the Greeks to preserve their independance and freedom face to the most powerful empire the world had known till then and its ambition for further expansion and domination is a great one and has inspired and will continue to inspire people fighting for freedom and dignity around the world. I don’t think that we have the right to misinterpret and distort this story, transforming it into some kind of archetypal myth of the modern Western colonialism and racism, as some do today. And of course what I say has nothing to do with stereotypical distinctions between “West” and “East”: tyranny in its different forms was a Western phenomenon too, and history proves that Eastern peoples can be excellent fighters for freedom. But we should not lose from sight the real stakes of the Persian Wars and of their historiography.

Moreover, despite clichés and exaggerations, Ι believe that the ancient Greeks got some important things right in their views on the Persian Empire. I say this because, if the Greek reports about the Persian “decadence” may be exaggerated and the Persian Empire remained very powerful despite its defeat in the Persian Wars, historical experience shows that in the courts of in theory all-powerful monarchs you find more often than not arrogance, corruption, sycophancy, dishonesty, and intrigues, a reality which corroborates to an important degree the reliability of much of the Greek accounts about the Persian court. More essentially, although the Greek claims that the Persians were “slaves” of their kings were exaggerated (and very probably meant as literary devices), it is true that the political structure of the Persian Empire was characterized by overconcentration of huge power in the hands of one person (the Great King), whereas the Greeks valued rule of law, freedom of the citizens, and distribution of power among several bodies, and in the more advanced cases of city-states, ideas of political equality among the citizens and of popular government. To put it a bit differently, the Persians have resolved the problem of political authority through recourse to the regime of monarchy, moreover a monarchy which with the expansion of the Persian Empire and the accumulation of power and wealth in the hands of the Great King took more despotic characteristics, whereas the Greeks have experimented with a broad range of political regimes, that one could qualify as constitutional/republican and in some cases democratic. Now, despite the important flaws and limitations of these experiments (above all the existence of slavery- but all the important ancient civilizations knew slavery and similar situations of dependence and oppression), I believe that the Greek political experience expressed something more advanced and far more promising for the political and intellectual progress of humanity than the Achaemenid monarchy, and I think that we should not forget this ideological aspect of the Persian Wars. This does not mean that the ancient Iranian civilizations were not very important and it does not make accurate stereotypical views about some eternal and essentialist opposition of a republican/democratic “West” to a despotic “East”. But I think that what I have written desribes well the ideological dimension and historical importance of the Greco-Persian hostilities of the 5th century BCE.

4/ I don’t want to be totally dismissive of the school of “New Achaemenid historiography”, I sympathize with efforts to study the civilization of ancient Iran for its own importance and not just as the enemy of the ancient Greeks, and I don’t reject the contributions of the same school to the better understanding of ancient Persia and Iran. But what I see is that some of the “New Achaemenid historians” not only lose from sight some critical historical, intellectual and ideological aspects of the Greek-Persian conflict, not only are totally unsympathetic toward the Greek struggle for freedom face to the Achaemenid imperial expansionism, but they tend to idealize the Persian Empire and to see the Greco-Persian conflicts through exclusively Persian (imperial) eyes. However, the Persian Empire has been founded on the violence of conquest and, although the Achaemenids had remarkable political acumen and flexibility, they could also be ruthless and cruel when such attitudes could serve their imperial agenda. Moreover, I don’t think that the presentation of rose-tinted images of benevolent imperial absolute monarchy and the idealization of imperialisms of the past are in our days intellectual attitudes political neutral and without serious dangers.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of Achaemenid Iran 1A, Course I - Achaemenid beginnings 1A

Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Tuesday, 27 December 2022

Outline

Introduction; Iranian Achaemenid historiography; Problems of historiography continuity; Iranian posterior historiography; foreign historiography; Western Orientalist historiography; early sources of Iranian History; Prehistory in the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia

1- Introduction

Welcome to the 40-hour seminar on Achaemenid Iran!

It is my intention to deliver a rather unconventional academic presentation of the topic, mostly implementing a correct and impartial conceptual approach to the earliest stage of Iranian History. Every subject, in and by itself, offers to every researcher the correct means of the pertinent approach to it; due to this fact, the personal background, viewpoints and thoughts or eventually the misperceptions and the preconceived ideas of an explorer should not be allowed to affect his judgment.

If before 200 years, the early Iranologists had the possible excuse of studying a topic on the basis of external and posterior historical sources, this was simply due to the fact that the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing had not yet been deciphered. Still, even those explorers failed to avoid a very serious mistake, namely that of taking the external and posterior historical sources at face value. We cannot afford to blindly accept a secondary historical source without first examining intentions, motives, scopes and aims of it.

As the seminar covers only the History of the Achaemenid dynasty, I don't intend to add an introductory course about the History of the Iranian Studies and the re-discovery of Iran by Western explorers of the colonial powers. However, I will provide a brief outline of the topic; this is essential because mainstream Orientalists have reached their limits and cannot provide us with a real insight, eliminating the numerous and enduring myths, fallacies, and deliberately naïve approaches to Achaemenid Iran.

In fact, most of the specialists of Ancient Iran never went beyond the limitations set by the delusional Ancient 'Greek' (in reality: Ionian and Attic) literature about the Medes and the Persians (i.e. the Iranians), because they never offered themselves the task to explain the reasons for the aberration that the Ancient Ionian and Attic authors created in their minds and wrote in their texts about Iran. This was utterly puerile and ludicrous.

And this brings us to the other major innovation that I intend to offer during this seminar, namely the proper, comprehensive contextualization of the research topic, i.e. the History of Achaemenid Iran. To give some examples in this regard, I would mention

a - the tremendous, multilayered and multifaceted impact of the Mesopotamian World, Civilization and Heritage on the formation of the Achaemenid Empire of Iran, and more specifically, the determinant role played by the Sargonid Empire of Assyria on the emergence of the first Empire on the Iranian plateau;

b - the ferocious opposition of the Mithraic Magi to the Zoroastrian Achaemenid court;

c - the involvement of the Anatolian Magi in the misperception of Iran by the Ancient Greeks; and

d- the utilization of the Ancient Greek cities by the Anti-Iranian side of the Egyptian priesthoods, princes and administrators.

To therefore introduce the proper contextualization, I will expand on the Neo-Assyrian Empire and the Sargonid times, not only to state the first mentions of the Medes and the Persians in History, but also to show the importance attributed by the Neo-Assyrian Emperors to the Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau, as well as the numerous peoples, settled or nomadic, who inhabited that region.

There is an enormous lacuna in the Orientalist disciplines; there are no interdisciplinary studies in Assyriology and Iranology. This plays a key role in the misperception of the ancient oriental civilizations and in the mistaken evaluation (or rather under-estimation) of the momentous impact that they had on the formation of the World History. There are no isolated cultures and independent civilizations as dogmatic and ignorant Western archaeologists pretend.

Only if one studies and evaluates correctly the colossal impact of the Ancient Mesopotamian world on Iran, can one truly understand the Achaemenid Empire in its real dimensions.

2- Iranian Achaemenid historiography

A. Achaemenid imperial inscriptions produced on solemn occasions

Usually multilingual texts written by the imperial scribes of the emperors Cyrus the Great, Darius I the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, Darius II, Artaxerxes II, and Artaxerxes III, as well as of the ancestral rulers Ariaramnes and Arsames.

Languages and writing systems:

- Old Achaemenid Iranian (cuneiform-alphabetic; the official imperial language)

- Babylonian (cuneiform-syllabic; to offer a testimony of historical continuity and legitimacy, following the Conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great, who presented himself as king of Babylon)

- Elamite (cuneiform-logo-syllabic; to portray the Persians in particular as the heirs of the ancient land of Anshan and Sushan that the Assyrians and the Babylonians named 'Elam' and the indigenous population called 'Haltamti' / The first Achaemenid to present himself as 'king of Anshan' is Cyrus the Great and the reference is found in his Cylinder unearthed in Babylon.)

and

- Egyptian Hieroglyphic (if the inscription or the monument was produced in Egypt, since the Achaemenids were also pharaohs of Egypt, starting with Kabujiya/Cambyses)

Imperial inscriptions are found in: Babylon (Cyrus Cylinder), Pasargad, Behistun, Hamadan, Ganj-e Nameh, Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rustam, Susa, Suez (Egypt), Gherla (Romania), Van (Turkey), and on various items

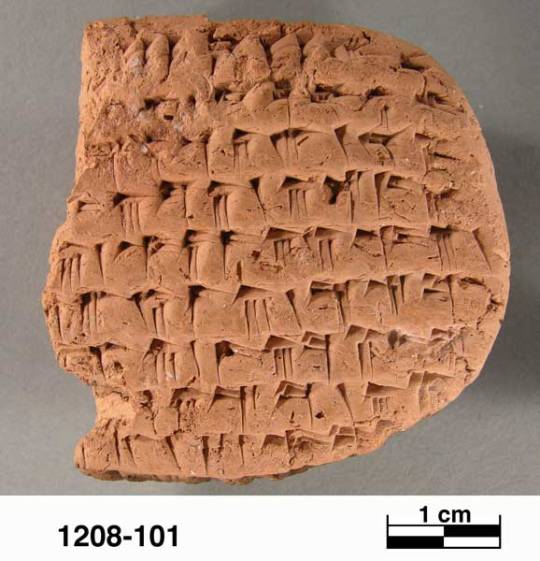

B. Persepolis Administrative Archives

This consists in an enormous documentation that has not yet been fully studied; it is not written in Old Achaemenid as one could expect but mainly in Elamite cuneiform. It consists of two groups, namely

- the Persepolis Fortification Archive, and

- the Persepolis Treasury Archive.

The Persepolis Fortification Archive was unearthed in the fortification area, i.e. the northeastern confines of the enormous platform of the Achaemenid capital Parsa (Persepolis), in the 1930s. It comprises of more than 30000 tablets (fragmentary or entire) that were written in the period 509-494 BCE (at the time of Darius I). The tablets were written in Susa and other parts of Fars and the territory of the ancient kingdom of Elam that vanished in the middle of the 7th c. (more than 130 years before these texts were written). Around 50 texts had Aramaic glosses. More than 2000 tablets have been published and translated. These texts are records of transactions, distribution of food, provisioning of workers, transportation of commodities, etc.; few tablets were written in other languages, namely Old Iranian (1), Babylonian (1), Phrygian (1) and Greek (1).

The Persepolis Treasury Archive was found in the northeastern room of the Treasury of Xerxes. It contains more than 750 tablets and fragments (in Elamite) and more than 100 have been published. They all date back in period 492-458 BCE. These tablets are either letters or memoranda dispatched by imperial officials to the head of the Treasury; they concern the payment of workmen, the issue of silver, and other administrative procedures. Only one tablet was written in Babylonian.

The entire documentation offers valuable information as regards the function of various imperial services, namely the couriers, the satraps, the imperial messengers, the imperial storehouse, etc. The archives shed light on the origin of the imperial administrators, as ca. 1900 personal names have been recorded: 10% were Elamites (who had apparently survived for long far from their country after the destruction of Susa by Assurbanipal (640 BCE), fewer were Babylonians, and the outright majority consisted of Iranians (Persians, Medes, Bactrians, Sakas, Arians, etc.).

C. Imperial Aramaic

The diffusion of the use of Aramaic started already in the Neo-Assyrian times and during the 7th c. BCE; the creation of the 'Royal Road', the systematization of the transportation, the improvement of communications, and the formation of the network of land-, sea- and desert routes that we now call 'Silk-, Spice- and Perfume- Road' during the Achaemenid times helped further expand the use of Aramaic. The linguistic assimilation of the Babylonians, the Jews and the Phoenicians with the Aramaeans only strengthened the diffusion of the Aramaic, which became the second international language ('lingua franca') in the History of the Mankind (after the Akkadian / Assyrian-Babylonian). Gradually, Aramaic became an official Achaemenid language after the Old Achaemenid Iranian.

Except the Aramaic texts attested in the Persepolis Administrative Archives, thousands of Aramaic texts of the Achaemenid times shed light onto the society, the economy, the administration, the military organization, the trade, the religions, the cults, the culture and the spirituality attested in various provinces of the Iranian Empire. At this point, only indicatively, I mention few significant groups of texts:

- the Elephantine papyri and ostraca (except Aramaic, they were written in Hieratic and Demotic Egyptian, Coptic, Alexandrian Koine, and Latin) – 5th and 4th c. BCE,

- the Hermopolis Aramaic papyri,

- the Padua Aramaic papyri, and

- the Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents from Bactria (48 texts written on leather, papyrus, stone or clay, dating from the period 353-324 BCE, and mainly from the reign of Artaxerxes III whereas the most recent dates from the reign of Alexander the Great).

Here I have to add that the widespread use of Imperial Aramaic and its use as a second official language for Achaemenid Iran brought an end to the use of the Elamite (in the middle of the 5th c.) and, after the end of the Achaemenid dynasty and the split of the state of Alexander the Great, contributed to the formation of two writing systems, namely Parthian and Pahlavi which were in use during the Arsacid and the Sassanid times. Imperial Aramaic helped establish many other writing systems, but this goes beyond the limits of the present seminar.

3- Problems of historiography continuity

There are no historical references to the Achaemenid dynasty made at the time of the Arsacids (Ashkanian: 250 BCE-224 CE) and the Sassanids 224-651 CE); this situation is due to many factors:

- the prevalence of another Iranian nation of probably Turanian origin, namely the Parthians and the Arsacid dynasty,

- the rise of the anti-Achaemenid, anti-Zoroastrian Magi who tried to impose Mithraism throughout Iran during the Arsacid times,

- the formation of an oral epic tradition and the establishment of a legendary historiography about the pre-Arsacid past during the Sassanid times, and

- the scarcity of written sources and the terrible destructions that occurred in Iran during the Late Antiquity, the Islamic era, and the Modern times (early Islamic conquests, divisions of the Abbasid times, Mongol invasions, Safavid-Ottoman wars, Western colonial looting, etc.).

This situation raised Western academic questions of Iranian identity, continuity, and historicity. But this attempt is futile. Iranian historiography of Islamic times shows that these questions were fully misplaced.

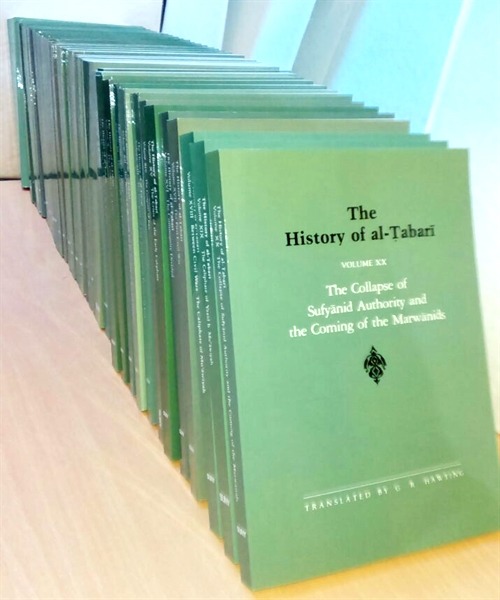

4- Iranian posterior historiography (Iranian historiography of Islamic times)

With Tabari (839-923) and his voluminous History of Prophets and Kings we realize that there were, in spite of the destructions caused because of the Islamic conquests, historical documents on which he was based to expand about the Sassanid dynasty; actually one out of the 40 volumes of the most recent translation of Tabari to English (published by the State University of New York Press from 1985 through 2007) is dedicated to the History of Sassanid Iran (vol. 5). And the previous volume (vol. 4) covers the History of Achaemenid and Arsacid Iran, Alexander the Great, Nabonid Babylonia, Assyria and Ancient Israel and Judah.

Other important Iranian historians of the Islamic times, like Abu'l-Fadl Bayhaqi (995-1077), Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247-1318) who wrote the truly first World History, Alaeddin Aṭa Malik Juvaynī (1226-1283), and Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi (ca. 1370-1454), did not expand much on pre-Islamic periods as the focus of their writing was on contemporaneous developments.

However, the aforementioned historians and all the authors, who are classified in this category, represent only one dimension of Iranian historiography of Islamic times. A totally different approach and literature have been illustrated by Ferdowsi's Shahnameh (Book of Kings). Abu 'l Qasem Ferdowsi (940-1025) was not the first to compose an epic in order to standardize in mythical terms and legendary concepts the pre-Islamic Iranian past; but he was the most successful and the most illustrious. That is why many other epic poets followed his example, notably the Azeri Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209) and the Turkic Indian Amir Khusraw (1253-1325).

Within the context of this poetical historiography, historical emperors of pre-Islamic Iran appear as legendary figures only to be then viewed as materialization of divine patterns. The origin of this transcendental historiography seems to be retraced in the Sassanid times, but all the major themes are clearly of Zoroastrian identity and can therefore be attributed to the Achaemenid world perception and world conceptualization.

It is essential at this point to state that, until the imposition of modern Western colonial academic and educational standards in Iran, Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and the corpus of Iranian legendary historiography was the backbone of the Iranian cultural, intellectual and educational identity.

It is a matter of academic debate whether an original text named Khwaday-Namag, written during the Sassanid times, and now lost, is at the very origin of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and of the Iranian legendary historiography. The 19th c. German Orientalist Theodor Nöldeke is credited with this theory that has not yet been proved.

All the same, the spiritual standards of this approach are detected in the Achaemenid times.

5- Foreign historiography

Ancient Greek (in reality, Ionian and Attic), Ancient Hebrew and Latin sources of Achaemenid History exist, but first they are external, second they appear to be posterior in their largest part, and third they often bear witness to astounding inaccuracies, fables, untrustworthy data, misplaced focus, excessive verbosity without real substance, and -above all- an enormous and irreconcilable misunderstanding of the Iranian Achaemenid reality, values, world view, mindset, and behavior.

The Ancient Hebrew sources shed light on issues that were apparently critical to the tiny and unimportant, Jewish minority of the Achaemenid Empire; however, these Biblical narratives concern facts that were absolutely insignificant to the imperial authorities of Parsa. One critical issue is concealed by modern scholars though; although all the nations of the Empire were regularly mentioned in the Achaemenid inscriptions and depicted on bas reliefs, the Jews were not. This undeniable fact irrevocably conditions the supposed 'importance' of Biblical texts like Ezra, Esther, Nehemiah, etc. All the same, these foreign historical sources are important for the Jews.

The Ionian and Attic accounts of events that were composed by the Carian renegade Herodotus, the Dorian Ctesias, and the Athenian Xenophon present an even more serious problem. They happened to be for many centuries (16th – 19th c.) the bulk of the historical documentation that Western European academics had access to as regards Achaemenid Iran. This situation produced grave biases among Western academics, because they took all these sources at face value since they had no access to original documentation. The grave trouble persisted even after the decipherment of the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing and the archaeological excavations that brought to daylight original Iranian imperial documentation.

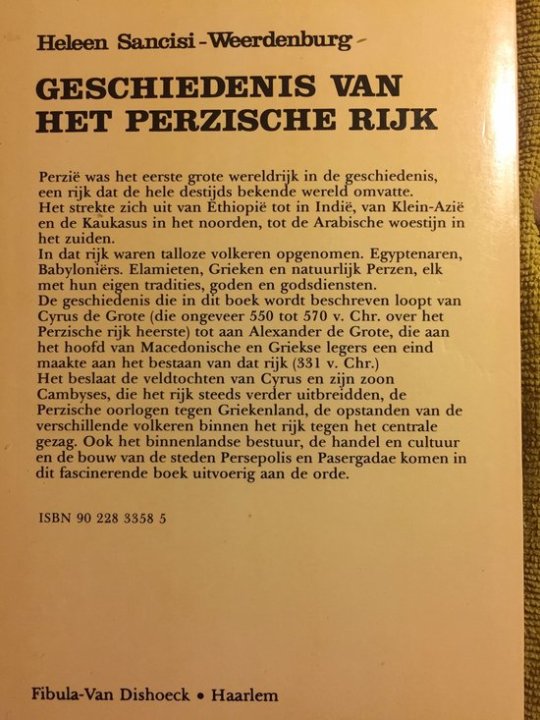

Only recently, at the end of the 20th c., leading Iranologists like Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg started criticizing the absolutely delusional History of Achaemenid Iran that modern Western scholars were producing without even understanding it by foolishly accepting Ancient Ionian myths, lies and propaganda against the Iranian Empire at face value. This grave problem had also two other parameters:

- first, there was an enormous gap of civilization and a tremendous cultural difference between the Iranian imperial world view, the spiritual valorization of the human being, and the Zoroastrian monotheism from one side and the chaotic, disorderly and profane elements of the western periphery of the Empire. The so-called Greek tribes in Western Anatolia and in the South Balkans were not only multi-divided and plunged in permanent conflict; they were also extremely verbose on common issues, they desecrated the divine world with their nonsensical myths and puerile narratives, and they defiled human spirituality with their love stories about their pseudo-gods. But, very arbitrarily and quite disastrously, the so-called Ancient Greek civilization had been erroneously taken as 'classics' by modern Europeans at a time they had no access to Ancient Oriental sources.

- second, the vertical differentiation between Imperial Iran as the blessed land of divine mission and the disunited and peripheral lands of conflict, discord and strife that were inhabited by the Greek tribes was reflected on the respective, impressively different types of historiography; to the Iranians, few words written by anonymous scribes were enough to describe the groundbreaking deeds of divinely appointed rulers. But for the Greeks, the useless rumors, the capricious hearsay, the intentional lie, the nefarious expression of their complex of inferiority, the vicious slander, and the deliberate ignominy 'had' to be recorded and written down.

The fact that Herodotus' and Xenophon's long narratives have long been taken as the basic source of information about Achaemenid Iran demonstrates how disoriented and misplaced modern Western scholarship is. But by preferring to rely mainly on the Ancient Greek lengthy and false narratives, and not on the succinct, true and chaste Old Achaemenid Iranian inscriptions, they totally misrepresent Ancient Iranian History, preposterously extrapolating later and corrupt standards to earlier and superior civilizations.

And whereas Ancient Roman authors, who wrote in Latin (Pliny the Elder, Seneca the Younger, etc.), and Jewish or Christian historians, who wrote in Alexandrine Koine, like Flavius Josephus and Eusebius of Caesarea Maritima, reproduced the style of lengthy narratives that turns History to mere gossip, the great Babylonian scholar Berossus was very reluctant to add personal comments to his original sources or to allow subjective considerations and thoughts to contaminate his text.

In any case, the vast issue of the multilayered damages caused by the untrustworthy Ancient Greek historiography to modern Western academics' perception and interpretation of Achaemenid Iran is a topic that deserves an entirely independent seminar.

--------------

To watch the video (with more than 110 pictures and maps), click the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN - Achaemenid beginnings 1Α

By Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

youtube

------------------------

To listen to the audio, clink the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN - Achaemenid beginnings 1 (a+b)

------------------------------

Download the text in PDF:

#Achaemenid dynasty#Achaemenid History#Ariaramnes#Arsacid#Arsames#Artaxerxes I#Artaxerxes II#Artaxerxes III#Assyria#Assyriology#Babylon#Babylonia#Babylonian#Berossus#Cambyses#Ctesias#cuneiform#Cyrus the Great#Darius I the Great#Darius II#Elam#Elamite#Elephantine papyri#Esther#Ezra#Ferdowsi#Ganj-e Nameh#Gherla#Hamadan#Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Iranology - Gilan Province - Ashkevar 2 | 2 گیلان، اشکور

0 notes

Link

The adjective Persian (Pârsi) has only been used by Iranians to describe the national language of Iran, which has been spoken, and especially written, by all Iranians regardless of whether it is their mother tongue. The Persian heritage is at the core of Iranian Civilization.

Civilizations are not as narrow as particular cultures in their ideological orientation. Even cultures evolve and are not defined by a single worldview in the way that a political party has a definite ideology. The inner dialectic that drives the historical evolution of Iranian Civilization is based on a tension between rival worldviews. This is comparable to the numerous worldview clashes that have shaped and reshaped Western Civilization, and is more dynamic than the creative tension between the worldviews of Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Communism and the cultural characters of the Han, the Manchurians, Mongols, and Tibetans in the history of Chinese Civilization.

Support Russia Insider -

Go Ad-Free!

The phrase “Iranian Civilization”, has long been in use by academics in the field of Iranology or Iranian Studies. That there is an entire scholarly field of Iranology attests to the world-historical importance of Iran. However, in the public sphere, and even among other academics, Iran has rarely been recognized as a distinct civilization alongside the other major civilizations of world history. Rather, Iran has for the most part been mistakenly amalgamated into the false construct of “Islamic Civilization.”

We have entered the era of a clash of civilizations rather than a conflict between nation states. Consequently, the recognition of Iran as a distinct civilization, one that far predates the advent of Islam and is now evolving beyond the Islamic religion, would be of decisive significance for the post-national outcome of a Third World War.

Iran is a civilization that includes a number of different cultures and languages that hang together around a core defined by the Persian language and imperial heritage. Besides the Persian heartland, Iranian Civilization encompasses Kurdistan (including the parts of it in the artificial states of Turkey and Iraq), the Caucasus (especially northern Azerbaijan and Ossetia), Greater Tajikistan (including northern Afghanistan and Eastern Uzbekistan), the Pashtun territories (in the failed state of Afghanistan), and Baluchistan (including the parts of it inside the artificial state of Pakistan).

As we shall see, Iranian Civilization deeply impacted Western Civilization, with which it shares common Indo-European roots. There are still a few countries in Europe that are so fundamentally defined by the legacy of the Iranian Alans, Sarmatians, or Scythians that they really belong within the scope of Iranian, rather than European or Western Civilization. These are Ukraine, Bulgaria, Croatia, and, should it ever secede from Spain, Catalonia. The belonging of these European, Caucasian, Middle Eastern, Central Asian, and South Asian ethnicities and territories to an Iranian civilizational sphere is, by analogy, comparable to how Spain, France, Britain, Germany, and Italy are all a part of Western Civilization.

An even closer analogy would be to China, which is also a civilization rather than simply a nation. China, considered as a civilization, includes many cultures and languages other than that of the dominant Han Chinese. For example, the Manchurians, Mongolians, and Tibetans. What is interesting about China, in this regard, is that its current political administration encompasses almost its entire civilizational sphere – with the one exception of Taiwan (and perhaps Singapore). In other words, as it stands, Chinese Civilization has nearly attained maximal political unity.

Support Russia Insider -

Go Ad-Free!

Western Civilization also has a high degree of political unity, albeit not at the level of China. The Western world is bound together by supranational economic and military treaties such as the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). By contrast, Iranian Civilization is currently near the minimal level of political unity that it has had throughout a history that spans at least 3,000 years.

To borrow a term from the Russian philosopher, Alexander Dugin, the Persian ethnicity and language could be described as the narod or pith of Iranian Civilization. This would be comparable to the role of the Mandarin language and the Han ethnicity in contemporary Chinese Civilization, or to the role of Latin and the Italian ethnicity in Western Civilization at the zenith of the Roman Empire when Marcus Aurelius had conquered and integrated Britain and Germany. Although I accept Samuel Huntington’s concept of a “clash of civilizations”, I reject his distinction between what he calls “Classical Civilization” and Western Civilization.

This is a distinction that he adopts from Arnold Toynbee, and perhaps also Oswald Spengler, both of whom see the origins of Western Civilization in Medieval Europe. In my view, Western Civilization begins with Classical Greece and is adopted and adapted by Pagan Rome.

The narod of a civilization can change. If Western Civilization were to prove capable of salvaging itself and reasserting its global dominance in the form of a planetary American Empire, this would no doubt involve a shift to the English language and the Anglo-Saxon ethnicity as the Western narod. The lack of a clear narod in Western Civilization at present is symptomatic of its decline and dissolution following the intra-civilizational war that prevented Greater Germany from becoming the ethno-linguistic core of the entire West. A very strong argument could be made that Germany and the German language were long destined to succeed Italy in this role, which Italy still plays to some extent through the Vatican’s patronage of Latin and the Roman Catholic faith.

The alliance of Hitler with Mussolini could have prepared for such a transition. If, for whatever reason, Latin America were to one day become the refuge of Europeans and even Anglo-Saxons fleeing Europe and North America, there would be a very good chance that the Spaniard ethnicity and the Spanish language would become the narod of Western Civilization following this transformative crisis.

Support Russia Insider -

Go Ad-Free!

In the three thousand years of Iranian Civilization, the narod of the civilization has shifted only once. For the first five hundred years of discernable Iranian history, the Median ethno-linguistic consciousness was at the core of Iran’s identity as a civilization that included other non-Median Iranian cultures, such as the Scythians. Actually, for most of this period, the Medes were embattled by the Assyrians and other more entrenched non-Iranian (i.e. non Aryan) cultures, such as the Elamites. It is only for a brief period (on the Iranian scale of history, not the American one) that the Medes established a strong kingdom that included other Iranian cultures and could consequently be considered a standard bearer of an Iranian Civilization rather than a mere culture.

This lasted for maybe a couple of hundred years before the revolt of Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC saw the Persians displace the Medes and expand the boundaries of Iranian Civilization into the borders of the first true empire in history, one that included and integrated many non-Iranian kingdoms, and encompassed almost the entire known world.

For more than a thousand years after Cyrus, and despite the severe disruption of the Alexandrian conquest and colonization of Iran, we saw a succession of the three empires of the Achaemenids, the Parthians, and the Sassanians. The Achaemenid language was Old Persian, while the Parthians and Sassanians spoke and wrote Middle Persian (Pahlavi). These languages are direct ancestors of Pârsi (or Dari), the New Persian language that, in its rudiments, arose at the time of Ferdowsi (10th century AD) and has remained remarkably stable until the present day.

For more than 2,500 years, the Persian ethnicity and language have defined the core identity of Iranian Civilization. That was not lost on all of the various Europeans who dealt with Iran as an imperial rival from the days of the classical Greeks, to the pagan Romans, to the Byzantines, the British, the French, and the Russians.

All of them, without exception, always referred to all of Iran and its entire civilizational sphere as “Persia” or the “Persian Empire.” Friedrich Nietzsche wished that the Persians would have successfully conquered the Greeks because he believed that they could have gone on to become better guardians of Europe than the Romans proved to be. Nietzsche claimed that “only the Persians have a philosophy of history.” He recognized that historical consciousness, of the Hegelian type, begins with Zarathustra’s future-oriented evolutionary concept of successive historical epochs leading up to an unprecedented end of history.

Support Russia Insider -

Go Ad-Free!

The will to ensure that the Persian Gulf does not become Arabian, that Persian is not disestablished as the official language of Iran, and, in short, that Iranian Civilization does not disappear, is based on more than just patriotic sentimentality, let alone nationalistic chauvinism. Iran is certainly a civilization among only a handful of other living civilizations on Earth, rather than a lone state with its own isolated culture, like Japan, but Iran is even more than that. As we enter the era of the clash of civilizations, Iran’s historic role as the crossroads of all of the other major civilizations cannot be overstated.

In his groundbreaking book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, the Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington argues for a new world order based on a détente of great civilizations rather than perpetual conflict amongst nation-states. In effect, Huntington envisages the end of the Bretton Woods International System put in place from 1945–1948 after the Second World War. He advocates for its replacement with a geopolitical paradigm that would be defined by the major world-historical countries. These are the countries that can each be considered the “core state” of a civilization encompassing many peripheral vassal or client states.

The core state of any given civilization can change over the course of history. For example, Italy was the core state of Western Civilization for many centuries, and as the seat of the Roman Catholic Church it still has significant cultural influence over the West – especially in Latin America.

Currently, however, the United States of America plays the role of the Western civilizational core state, with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) effectively functioning as the superstructure of an American Empire coextensive with the West, with the exception of Latin America, where the United States has been economically and diplomatically dominant at least since the declaration of the Monroe Doctrine.

Huntington identifies less than a handful of surviving world-class civilizations whose interactions would define the post-international world order: Western Civilization, Orthodox Civilization, Chinese Civilization, and Islamic Civilization. The core states of the first three are America, Russia, and China. Within the context of his model a number of major world powers lack civilizational spheres. These “lone states” notably include India and Japan. While it has a high level of culture, and deep historical ties to China, Japan is not a part of Chinese Civilization and yet it lacks a civilizational sphere of its own that would encompass other states. Had the Japanese Empire triumphed in the Second World War, Japan might have become a civilization in its own right – one dominating the Pacific.

Support Russia Insider -

Go Ad-Free!

India is an interesting case, because in addition to being a “lone state” it also fits Huntington’s definition of a “torn state.” The latter are nations that are suffering from an identity crisis on account of being torn between two or more civilizations. India has its own Hindu civilization, which once extended to many neighboring states, but which is now more or less confined to India (with the possible exception of Sri Lanka), but India is also the world’s largest Muslim country.

Despite the fact that Muslims remain, for the moment, a minority in India, the country is still home to more Muslims than Pakistan or any other Islamic nation on Earth. Given current demographic trends, and historical precedents such as the Mughal Empire, the possibility of India becoming a part of Islamic Civilization is a prospect to be taken seriously.

Of all the major civilizations delineated by Huntington, Islamic Civilization is the only one lacking a clear core state. Huntington considers this one of the reasons for the perpetual strife both within the Islamic world and between Islamic countries and states that are part of other civilizations. In effect, non-Islamic powers are confronted by a situation wherein there is no one to negotiate with who would have the legitimate authority to enforce a uniform policy within Islamic Civilization in a fashion comparable to America’s capability to speak for the West in fundamental conflicts with Russia or China. In such confrontations, European leaders may grumble about hegemonic American decision-making but when it comes down to it the United States really does make policy for the West. Germany, the strongest and most central state in Europe, is home to numerous American military bases and installations. Italy, historically the most enduring European core state of Western Civilization, also quietly remains under American military occupation.

Since the collapse of the Ottoman Caliphate in 1918, and Western colonial demarcation of totally artificial national borders across North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, the Islamic World has been without a center. From a historical standpoint Egypt, Turkey, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia rival each other as artificial nation states that in a totally incomparable pre-national and pre-modern form once had the legitimacy of being home to the Khalifa (or sovereign authority) of the Ummat (the worldwide Islamic community).

However, when viewed in terms of military and economic power, Pakistan, Malaysia, and Indonesia are more significant geopolitical players within the Islamic world. With a view to assuming leadership of an Islamic civilizational sphere, none of these countries is as well positioned as the Islamic Republic of Iran in terms of its cultural-historical heritage, industrial capability, and strategic location. Of all of the contenders within the Islamic world, Iran alone has the potential to resume its natural historical role, not just as a world power, but as a superpower responsible for securing the Islamic sphere within a new global order.

Support Russia Insider -

Go Ad-Free!

From an Iranian standpoint, the ultimate aim of this geostrategic project would be to reassert the Iranian character of the core of the Islamic world, thereby dismantling the false construct of Islamic Civilization while forwarding a Renaissance of Iranian Civilization. From a global strategic standpoint, this Greater Iran would be saving the West, India, Russia, and even China (which has an increasingly serious Muslim problem) from the prospect of a late 21st century world defined by a global Sunni Caliphate governing a human population demographically dominated by Muslims.

This is Iran’s cultural-historical responsibility. Only if Iranians themselves admit this, can other major world powers also recognize the fact that Iran’s acceptance of this titanic duty is for the good of all mankind. This could be the key to Iran’s reemergence as a global superpower. Iran has been destined to be the Leviathan among nations.

Thomas Hobbes appropriated the image of the Leviathan from the Biblical book of Job as a metaphor for a kind of sovereign authority so absolute that it would be seen as God’s viceroy on Earth. When Hobbes’ mother went into labor with him on April 5th of 1588, her birth pangs were induced by shock at the prospect of a Spaniard naval invasion of Britain, such that Hobbes would joke – with a very dark sense of humor indeed – that she “gave birth to twins, myself and fear.” Hobbes was a reader of the work of his contemporary, Rene Descartes, with whom he exchanged barbs over who had come up with which of their shared ideas first. Hobbes’ friend, Marin Mersenne, was Descartes’ publicist, and at one point he asked Hobbes to write a review of Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy; this was published, together with Descartes’ replies, in 1641. Hobbes takes Descartes’ description of the body as a mechanism and applies it to the social body of the state, with the sovereign as the ghost in the machinery of government.

Hobbes actually says very little about the Book of Job, from which he draws the symbol of the Leviathan (it is more than a mere metaphor). One thing that he does say is that, unlike the historical parts of the Bible, the book is intended less to be a chronicle of events that actually took place than a philosophical treatise on the question of “why wicked men have often prospered in this world, and good men have been afflicted.” Citing textual analysis by scholars of his time, Hobbes points out that the core “argument” of the book is all in verse, while the narrative Preface and Epilogue are in prose.

What this means to him is that an essentially philosophical text has been framed in such a way as it could be incorporated into the Bible. Hobbes also acknowledges, on stylistic grounds and in terms of its philosophical content, that Job is a relatively late book of the Bible and he even specifically claims “the Writer must have been of the same time” or “after” the writer of “The History of Queen Esther… of the time of the Captivity.” In other words, the text is a product of the period of intense Imperial Iranian influence on the formation of Judaism as we know it.

The Leviathan is a monstrous sea creature or, if it is artificial, then it is a titanic submarine machinery of terror. Hobbes’ Leviathan is the most definitive argument for Absolute Monarchy in the history of political philosophy. The core of Leviathan is a critique of the separation of powers that is the aim of every constitutionalist movement.

This would include the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906–1911, which yielded a parliament (Majles) checking the power of the crown and which attempted to establish a constitutional monarchy in Iran. Hobbes saw this kind of limitation and division of the authority of the crown as the consequence of a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of sovereign power. His defense of Absolute Monarchy is so extreme that he even denies the right of private property and advocates for the suppression of what we would today call “civil society” as a social sphere independent of the political order. Insofar as this social (rather than political) sphere includes the Church, he demands that the latter utterly submit itself to the Sovereign – or, if you prefer, that the Sovereign be seen as God’s viceroy.

Finally, Hobbes envisions a regime so all-encompassing in its power over human life that the Sovereign would decide even on the meaning of language.

Rather than being praised by monarchists for defending their beloved institution in the strongest terms possible, Hobbes was mercilessly attacked by them. It is not just because they hated the book, but because his masterpiece exposed the deficits of King Charles – a man who Hobbes saw as too fickle and indecisive to be worthy of the crown as the country slid into civil war.

An observer of contemporary Iranian politics cannot help but to notice the similarity to the situation of the monarchist movement among exiled Iranian opposition groups today. Hobbes wrote Leviathan during the English Civil War, while he and other royalists were exiled in Paris. In 1642 the tense situation between the King and Parliament erupted into open strife, eventually leading the exiled royalists to Paris. Hobbes was one of these, and by 1646 he found himself employed as the personal mathematics tutor of the sixteen-year-old Prince of Wales.

So Hobbes wrote Leviathan at a time when Britain was facing both the prospect of disintegration through Civil War and foreign conquest at the hands of the Spaniards, the main colonial sea power rivaling the nascent British Empire. As the keen reader ought to notice, this is not too dissimilar from the situation faced by the Islamic Republic of Iran today.

A nation that, on the one hand, is beginning to carve out an imperial sphere of influence (in Iran’s case, unlike in Britain’s, for the fifth or sixth time in history) is at the same time facing both the prospect of internal disintegration through civil strife and a potential invasion initiated by foreign powers. The latter are also responsible for manufacturing ethnic separatist movements and stoking dissension so as to divide the country as they conquer it. The balkanization of Iran is, today, a very real impending catastrophe. Ironically, as in the case of Hobbes’ Britain, this danger comes on the doorstep of an era of imperial power. If Iran can remain united, it could reemerge not just as a regional hegemon but as a major player on the world stage – a role that Iran has played many times in its long history.

Given the strategic significance of the Islamic world, and the demographic destiny of Islam on this planet in the 21st century, an Iran that successfully dominates the Muslim heartland could even establish itself as one of several rival superpowers within the foreseeable future.

0 notes

Text

Abadan: A Case Study in Pseudo Colonial Architecture

Parham Karimi — Master of Architecture, University of Toronto (Corresponding Author) Hamid Afshar — Master of Archeology, Tarbiat Modares University Iranology Foundation, Research Department of Art and Architecture – Fall 2017 The built environment constructed around oil fields are important on many levels. They have influenced the lifestyle of many people who have worked and lived in these…

View On WordPress

#(When Iran’s Abadan was Capital of the World 2015)#1979 Revolution#Abadan#Abadan architectural history#Abadan class-based communities#Abadan climactic issues#Abadan cosmopolitan city#Abadan cricket clubs#Abadan ethnic and social harmony#Abadan gardens#Abadan global architecture#Abadan global culture#Abadan global population#Abadan housing#Abadan identity#Abadan Island#Abadan lifestyle#Abadan poor condition#Abadan prosperous city#Abadan semi-colonial atmosphere#Abadan semi-colonial city#Abadan social relationship#Abadan Strategic position#Abadan stylish bungalows#Abadan tea parties#Abadan transformation#Abadan western style houses#Abadan: A Case Study in Pseudo Colonial Architecture#Abadan’s modern history#Abadan’s shantytowns

0 notes

Photo

⚓ Iraj Pezeshkzad… Tahran'da 1928'de doğdu. Hakimlik yaptı… Diplomatlık yaptı… 1973'te yazdığı kitapla dünya çapında üne kavuştu: “Napolyon Dayım.” Fars edebiyatının başyapıtları arasına giren kitap İngilizce, Almanca, Fransızca, Rusça gibi dillere çevrildi. Konusu toplumsal bir hiciv olan kitap, 1976'da 18 bölümlük dizi yapıldı. İran İslam Devrimi'nden sonra kitap yasaklandı. Hikaye… 1940'ların başında Tahran'da üç ailenin yaşadığı konakta geçiyor. Kendini Napolyon sanan ve sürekli entrikacı İngilizlerin kendisi aleyhine planlar yaptığını düşünen emekli bir subayı konu ediyor. Yazar Pezeshkzad eserinde, İran'da meydana gelen her olayın arkasında yabancı güçleri arayan toplumsal psikolojiyi yansıtıyor. “Napolyon Dayım” evrensel bir eser. Bu sebeple… Sadece İran'ı değil, bir bakıma son dönemde yaşadığımız Türkiye'yi de anlatıyor! Yani… Sürekli her taşın altında “yabancı güçleri” arayan bir paranoyayı… Bunlar için… Hiçbir şey göründüğü gibi değildir; salt gerçeği onlar bilir. Konuyu şuraya bağlayacağım: Son İran olayları konusunda sağda ve solda kimileri peşinen hükmü verdi: Yabancı güçlerin kışkırtması! (Kuşkusuz fitneci ülkeler, ABD-İsrail-Suudi Arabistan.) İşte… Türkiye'de politik değerlendirme yapmak bu kadar basit-kolay! En acısı ise… Her meseleyi (neoliberalizmin zehirlediği bilinçle) etnik-inanç temelli analiz etmeleri! Pozitivizm/olguculuk unutuldu. Olayın iktisadi boyutu gözardı ediliyor artık… İran'da da sokağa çıkıp haykıran muhalifler sadece “dış mihrakların piyonu” olarak görülüyor. Oysa… İşte gerçekler İran'daki toplumsal hareketleri analiz etmek için şunları bilmeliyiz: –Yüksek faiz verme vaadiyle mevduat toplayan “Saminü'l-Hucec”, “Saminü'l-Eimme” gibi finans kuruluşları son dönemde ardı ardına battı. Binlerce insan parasını kaybetti. (Kirman, Luristan gibi eyaletlerde mayıs ayında protestolar yapıldı. Hatta Tahran'da “Arman” adlı finans kuruluşunun yöneticisi öldürüldü.) -Bürokratların yolsuzluğu ve aldıkları astronomik maaşlar gündemden hiç düşmedi. –Son bütçe yasasıyla kimi sübvansiyonların kesilmesi ve iç güvenlik kuruluşları ile dini kurumların paylarının çok artırılması insanlarda hayal kırıklığı yarattı. -Ülkede resmi verilere göre yüzde 13 işsizlik ve yüzde 9 enflasyon var. -İran'da sorun ekonomik temelli. Son ayaklanma Meşhet gibi dini ideolojik sembolizmin yoğun yaşandığı bir yerde çıktı. Bu nedenle eylemciler, İslam Devrimi'nin Rehberi Hameney'i de Cumhurbaşkanı Ruhani'yi sert ifadelerle hedef aldı. -İran'da protestolar yeni değil… Örneğin, Ahmedinejat'ın 2009 yılında ikinci dönem için cumhurbaşkanı seçilmesiyle patlak veren olaylar büyük ses getirmişti. Hatırlayın: 1997-2005 yılları arasında cumhurbaşkanlığı yapan Hatemi döneminde de olaylar çıktı. Yani… İran'da ekonomik hoşnutsuzluk yeni değil… Bu eylemler İran'da büyük kırılmalara sebep olur mu? Bu kararı İran yönetimi verecek! “Ekonomik reform” sözüyle ikinci kez iktidara gelen Ruhani'nin icraatları bu sorunun yanıtını oluşturacak. Çünkü… Haklılık payı içerse de, “sorunların kaynağı ABD ambargosu” denilerek fakirlik yok edilemiyor. Keza… İran yönetiminde 1979'da devrimi yapan birinci ve ikinci nesiller hâlâ iş başında. Ama… Yaş ortalaması 29.4 olan İran'da politize olmamış gençlik ile devrim yapan kadrolar arasında düşünsel mesafe giderek açılıyor… İran'ı sağlıklı analiz etmek şart. “İranist” azlığı Tarihte belki de hiçbir ülke İran kadar radikal değişimler yaşamadı! Bu ülkenin siyasi, iktisadi, kültürel tarihini yakından bilmek gerekir… Necati Lugal (1878-1964) adını duydunuz mu? Ya öğrencisi Adnan Sadık Erzi (1923-1990) adını? Tahsin Yazıcı (1892- 1970)… Ali Nihat Tarlan (1898- 1978)… Faruk Sümer (1924- 1995)… Meliha Ülker Anbarcıoğlu (1923-2012)… Ya da Toktamış Hoca'nın babası Ahmet Ateş (1917- 1966) adını duydunuz mu? Pek sanmıyorum… Hepsi “İranist” idi: İran'ın dillerini, tarihini bilen, eserler yazan ve çeviren bilim insanıydı. Bugün Türkiye'de İran üzerinde çalışan kaç bilim insanımız var? İsmail Aka ve F. Tulga Ocak'ı biliyorum; emekli oldular. İlber Ortaylı var. Bu isimlerin İran üzerinde tebliğler sunduklarını şuradan biliyorum: Roma'da 1983 yılında “Societas Iranologica Europaea (SIE)” kuruldu. Bu üç bilim insanı SIE üyesi seçildi. Bir de Osman Gazi Özgüdenli'yi tanıyorum; Tahran'da çıkarılan 20 ciltlik “İran Ansiklopedisi” çalışmasında bulundu. Peki… Türkiye'de İran üzerine çalışma yapan enstitü-araştırma merkezi var mı? (İsrail yanlısı, İran düşmanı FETÖ nedeniyle) Düne kadar yoktu… Yakın zamanda Ankara'da “İran Araştırmaları Merkezi (İRAM)” kuruldu. İran'daki son politik gelişmeleri buradan takip ediyorum. Tavsiye ederim… Ayrıca… Çok bilgi bulacağınız Gene R. Garthwaite araştırması “İran Tarihi” kitabını mutlak öneririm. Hiçbir konuda peşin hükümlü olmayın; önce kavramaya çalışın… . Soner YALÇIN

0 notes

Text

Persian Empire, ancient Greek historiography, and the “New Achaemenid historians”

Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Source of the picture: https://sworld.co.uk/2/40723/photoalbum/favoutite-list.html

“Of the two most famous wars in ancient history, the Persian Wars and the Punic Wars, only the latter has, very recently, ended in an armistice. A newspaper clipping announced that the Mayor of Rome and the Consul of Tunisia had signed an agreement for the ending of hostilities. The Persian Wars are not over yet, and one might be tempted to see in the repeatedly uttered accusations of 'hellenocentrism' and 'iranocentrism' in scholarly liter- ature a sign of continued warfare. The echoes of Marathon and Salamis are still resounding. Not only to the extent that two, often well defined, parties can be distinguished in the field of research on early Persian history, roughly corresponding with classical historians on the one side and archaeologists on the other, but also because the Persian Wars have caused the conceptual framework that profoundly influences all perceptions of the history of the Achaemenid period to come into being. History in the sense that we under- stand it is, at least partly, a result of the great conflict between Greece and Persia. In its formation it embodies a particular way of thinking that was typical of the Greek fifth century. However great, generous and honest the first historian of Persia may have been, he nevertheless participated in a conflict, no longer perhaps overt but still lingering on. Strict neutrality, if such a thing is ever possible for a historian, was beyond even the reach of Herodotus, although he made a serious attempt. Later, in the fourth century the parties became more clearly defined but at the same time real interest in the Persians was lost and consequently they were reduced to two-dimensional figures. Persian history was now neatly divided into two periods, one of vigour and one of decay: the boundary between these usually taken as coinciding with the 'Great Persian Wars.' The empire itself was no longer seen as an evolving state with problems and successes, with developments and changes within its administrative structure and in its relations with subjects, but as a petrified entity dominated by the shadowy figure of the King of Kings.

This was the picture of Persian history at the time of Alexander, when the original model of it gradually ceased to exist. The concept was frozen and immobile and has lasted for two millennia. It has had its functions and was used, first by Alexander and his troops and for centuries afterwards by European historians. It even remained quite unaffected by the great discoveries of the 19th century: the decipherment of Old Persian cuneiform hardly influenced the principal tenets on which Persian history was based. Not even the important excavations in Iran had any substantial effect on the received image: if the monuments did not agree with Herodotus, so much the worse for the monuments. The Greeks could not have been too far wrong: they were first of all Greeks, and therefore almost infallible, and secondly, they had been contemporaries and thus had first hand knowledge.

This picture has only very recently become unsatisfactory.· As Iranian linguists and archaeologists attempted to analyze their material within its own frame of reference the Greek brand of Persian history seemed to supply very few answers to their problems and was found to be less relevant. Ethno- archaeologists and anthropologists doing research in the area have further shifted the foci of research. At the same time important developments took place within the discipline of history itself. In the last two decades historians have become more interested in what might be called structural history, i.e. not so much the study of events and chronologies but the analysis of an entire society. In this type of research non-written evidence and written traditions of a non-literary character have become more important and have served to question the traditional view of the history of the Achaemenid period, based predominantly on the use of Greek historiographical sources.

In a structural approach to early Persian history the usefulness of the Greek tradition is obviously restricted (and at times even an obstacle, see below). The Greeks were usually not interested in the structure of the empire, their outlook being rather superficial and limited. Even in the few cases where an attempt was made to glance behind the curtain, the results were still distorted as even the most unprejudiced Greek author was necessarily influenced by the cultural and literary tradition in which he was working. Hence the paradoxical situation has arisen that, in order to move away from the dominant and oppressive Greek perspective, it is more than ever necessary to pay attention to Greek historiography and analyze it in a new way.

The content of the information about Persia in Greek literature was shaped and moulded to fit Greek artistic forms. Thus any historical information contained, not only in a very specific literary genre such as tragedy, but also in historiography will have been affected by the techniques either demanded by a particular literary form or characteristic of a specific author. The methods and techniques of individual authors have received much attention by classical scholars who have been able to single out patterns, designs and narrative structures in some of the main Greek authors on Persia. This increasingly sophisticated approach to the Greek sources, however, does not seem to have influenced the overall view of the Persian empire. Frequently authors of syntheses on the Persian empire use the data of Greek historiography indiscriminately, as though it were all equally relevant and reliable, ignoring (or perhaps simply unaware of) the discussions by classical scholars of, e.g., the narrative structure or the literary form that directly affects the trustworthiness of the source in question. On the other hand, classical scholars frequently fail to indicate the relevance of their source criticism to the historiography of the Persian empire, usually because they are not well enough acquainted with the Iranian evidence to make a comparison between their own results and the Persian data. This gap, further widened by the different channels through which specialists in both fields make their results public, has been as unprofitable for Greek studies as for Iranian research. As the progress made on both sides is undoubtedly to be ascribed to specialization in each of the separate fields, Iranian and Greek, it is unlikely that the gulf separating historians and philologists from archaeologists and Iranologists will be, or indeed can be, bridged by a single scholar. It was, therefore, desirable for 'East' and 'West' to meet and discuss the results obtained so far. The Groningen Workshop of 1984 aimed at precisely this type of meeting and discussion.

The Introductory Note to the Workshop suggested the following two problems as important items for papers: 1) Studies of the mechanisms of Greek historiography and other Greek literature concerning Persia. 2) Case studies of specific examples where Iranian and Greek sources are seemingly in conflict and discussions of how to resolve such apparent contradictions.”

From the Introduction of Amélie Kuhrt and Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg to the collective volume The Greek Sources.Proceedings of the Groningen 1984 Achaemenid History Workshop, edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt, available on file:///C:/Users/USer/Downloads/AH02.pdf

This seminary of 1984 was foundational for the historiographical school of the “New Achaemenid historians”. I appreciate how the two authors treat Herodotus and his historical approach to the Persian Empire. It is true that in later Greek authors -especially those with Panhellenic and anti-Persian political agenda- the Persians are often caricatured. I agree that we should not see the ancient Persians exclusively through the Greek eyes, that we should take into account the literary and intellectual context of the Greek authors who have written about Persia, and that the Iranian record is of fundamental importance for the historical knowledge of the Persian Empire and of the Persian civilization of the Achaemenid era. On the other hand, this Iranian record not only is fragmentary, but it is also dominated by the Achaemenid royal ideology and its particular way of understanding and representing things. And of course, if one should avoid caricatural presentations of the Persian Empire, one should also avoid its idealization. That’s why I think that the best scholarly approach to the Achaemenid history and civilization is the combination without prejudice of Iranian and non-Iranian (Greek and non-Greek) sources and their combined interpretation.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The summary of an important collective work on Herodotus and the Persian Empire (text in French)

“R. Rollinger, B. Truschnegg, R. Bichler (eds.). Herodot und das persische Weltreich, Herodotus and the Persian Empire

Compte-rendu réalisé par Astrid Nunn

https://doi.org/10.4000/abstractairanica.41394

Référence(s) :

R. Rollinger, B. Truschnegg, R. Bichler (eds.). Herodot und das persische Weltreich, Herodotus and the Persian Empire. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2011, 800 p. (Classica et Orientalia, 3)

Texte intégral

PDF

Signaler ce document

1. Cet épais volume de 800 pages rassemble les communications offertes lors d’un colloque qui s’est tenu à Innsbruck (Autriche) en 2008. Le thème général “Vorderasien im Spannungsfeld klassischer und altorientalischer Überlieferungen” qui avait déjà été l’objet de deux colloques a pour Innsbruck été focalisé sur “Hérodote et l’Empire perse”. Le but de ce volume est la confrontation d’une lecture critique d’Hérodote avec les sources écrites et archéologiques des pays de l’Empire ach��ménide.