#Artaxerxes III

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

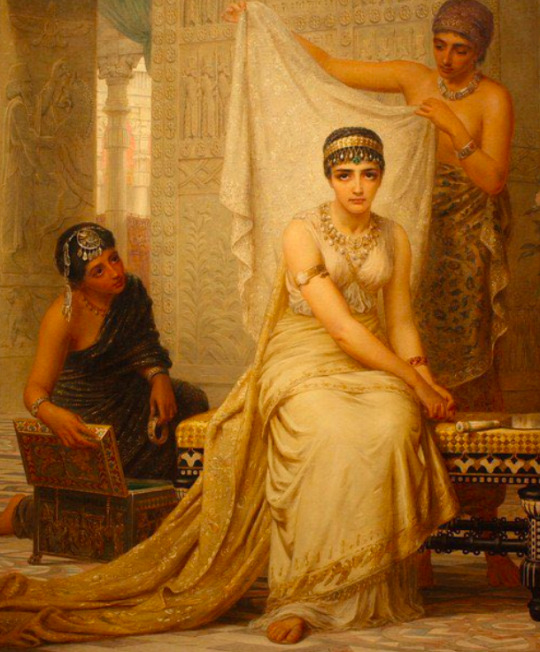

Rock relief of Artaxerxes III in Persepolis (aka Ochus) + The Dressing by L. Fitton + The Anabasis of Alexander by Arrian

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

PERS KRAL MEZARLARI

III. Artaxerxes'in mezarı İran'ın Fars Eyaleti, Naqsh-e-Rostam arkeolojik alanı ve nekropolünde yer almaktadır.

III. Artaxerxes (Ochus), M.Ö. 358 ile 338 yılları arasında Ahameniş İmparatoruydu. II. Artaxerxes'in oğlu ve halefiydi ve annesi Stateira'ydı.

Artaxerxes'in Mezarı, Persepolis platformunun arkasında, babasının mezarının yanında dağa oyulmuş. Altı tamamlanmış Ahameniş kraliyet mezarı vardır. Bunlardan dördü Naqš-e Rustam'da ve ikisi Persepolis'te keşfedildi.

Naqš-e Rustam'daki dört mezar Büyük Darius I, Xerxes, Artaxerxes I Makrocheir ve Darius II Nothus'a aittir. Daha genç görünen Persepolis Mezarları sonraki iki krala, Artaxerxes II Mnemon'a (M.Ö. 404-358) ve Artaxerxes III Ochus'a (M.Ö. 358-338) ait olmalıdır.

Mezar çoğu kez III. Artaxerxes'e atfedilir, ancak aslında kral II. Artaxerxes Mnemon'a ait olabilir. Eğer lahit gerçekten üçüncü Artaxerxes'e aitse mezar odası aynı zamanda Artaxerxes IV Asses ve Darius III Codomannus'un son dinlenme yeri olarak da hizmet vermiş olabilir, çünkü onlara hiçbir zaman uygun bir cenaze töreni yapılmamıştır.

Adet olduğu üzere, mezarın üst kısmındaki rölyef, kralın ebedi, kutsal ateşe ve yüce tanrı Ahuramazda'ya kurban sunuşunu göstermektedir. Hükümdar, tabi ulusları temsil eden kişilerin taşıdığı bir platformun üzerinde duruyor. Bu, Nakş-ı Rüstem'deki Büyük Darius'un mezarının üst kademesinin bir kopyasıdır, ancak yazıtın da kopyalandığı Artaxerxes II Mnemon Mezarı'nı süsleyen kopyadan daha az doğrudur. Alt kısımda mezarın girişi bulunmaktadır, bir lahit ve Artaxerxes II Mnemon'un mezarındakilere benzeyen bazı küçük figürler vardır.

Bu mezarın pilasterlerinin başlıkları özellikle iyi korunmuştur, çatıyı taşıyan boğaları göstermektedir. Persepolis'in saraylarında ve kabul salonlarında da aynı tasarım uygulandı. İnsanların kralla birlikte platform taşıdığı üst katta "taşıma" motifinin tekrarlanması dikkat çekicidir.

Yörede Elamlılardan Ahameniş'e ve antik İran'ın Sasani hanedanlarına kadar uzanan kayaya oyulmuş kabartmaların yanı sıra Nakş-ı Rostam aynı zamanda İran'ın Ahameniş Krallarının yerden yüksekte yeterli sayıda evde kaya yüzeylerine oyulmuş dört mezarı da yer alıyor.

0 notes

Text

Persepolis. Tomb of the Great King of Persia Artaxerxes III Ochus (359 or 358-338 BCE), an energetic but ruthless ruler who quelled many revolts of satraps and vassals, reconquered Egypt, and managed to restore temporarily the Achaemenid power. According to the ancient Greek sources he died poisoned by his vizier, the eunuch Bagoas.

233 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alexander the Great & the Burning of Persepolis

In the year 330 BCE Alexander the Great (l. 356-323 BCE) conquered the Achaemenid Persian Empire following his victory over the Persian Emperor Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE) at the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BCE. After Darius III's defeat, Alexander marched to the Persian capital city of Persepolis and, after looting its treasures, burned the great palace and surrounding city to the ground, destroying hundreds of years' worth of religious writings and art along with the magnificent palaces and audience halls which had made Persepolis the jewel of the empire.

The City

Persepolis was known to the Persians as Parsa ('The City of the Persians'), and the name 'Persepolis' meant the same in Greek. Construction on the palace and city was initiated between 518-515 BCE by Darius I the Great (r. 522-486 BCE) who made it the capital of the Persian Empire (replacing the old capital, Pasargadae) and began to house there the greatest treasures, literary works, and works of art from across the Achaemenid Empire. The palace was greatly enhanced (as was the rest of the city) by Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE, son of Darius, and would be expanded upon by Xerxes I's successors, especially his son Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424 BCE), although later Persian kings would add their own embellishments.

Darius I had purposefully chosen the location of his city in a remote area, far removed from the old capital, probably in an effort to dramatically differentiate his reign from the past monarchs. Persepolis was planned as a grand celebration of Darius I's rule and the buildings and palaces, from Darius' first palace and reception hall to the later, and grander, works of his successors, were architectural masterpieces of opulence designed to inspire awe and wonder.

In the area now known as the Marv Dasht Plain (northwest of modern-day Shiraz, Iran) Darius had a grand platform-terrace constructed which was 1,345,488 square feet (125,000 square meters) big and 66 feet (20 meters) tall and on which he built his council hall, palace, and reception hall, the Apadana, featuring a 200-foot-long (60 meters) hypostyle hall with 72 columns 62 feet (19 meters) high. The columns supported a cedar roof which was further supported by cedar beams. These columns were topped by sculptures of various animals symbolizing the king's authority and power. The Apadana was designed to humble any guest and impress upon visitors the power and majesty of the Persian Empire.

Darius I died before the city was completed and Xerxes I continued his vision, building his own opulent palace on the terrace as well as the Gate of All Nations, flanked by two monumental statues of lamassu (bull-men), which led into his grand reception hall stretching 82 feet (25 meters) long, with four large columns 60 feet high (18.5 meters) supporting a cedar roof with brightly decorated walls and reliefs on the doorways. The city is described by the ancient historian Diodorus Siculus (l. 1st century BCE) as the richest in the world and other historians describe it in the same terms.

Continue reading...

81 notes

·

View notes

Note

How many love interest did Alexander have in all of his life? I just recently found out he had an affair with a prostitute named Camaspe and apparently she was the one who was the first to have a physical relationship with him although not for long.

Love your work! 💕

Alexander’s Reported Lovers

Just an FYI … Kampaspe (Campaspe in Latin, also Pancaste) is a character in the second volume of Dancing with the Lion (Rise), as I wanted a second female voice and also a slave’s perspective. Even better that she was born to privilege, then lost it. She was reportedly a Thessalian hetaira from Larissa, which was handy as the Argeads had a long history of ties to the city of Larissa. I wrote about her before in a post from the blog tour the publisher had me do when the books first came out. You can read it HERE.

That said, she’s probably a Roman-era invention, mentioned only by late sources (Lucian, Aelian, and Pliny) all with one (repeated) story: Alexander as Super-patron. Reputedly, he gave her to his favored painter Apelles when, commissioned to do a nude, Apelles fell in love with her. Alexander kept the painting, Apelles got the girl. You bet I’ll have some fun with that. Kampaspe will remain a major character throughout the series…but not as Alexander’s mistress.

When trying to figure out how many sexual partners Alexander had, we must ask which were invented—or denied. Remember: ancient history wasn’t like modern (academic) history. It was essentially creative non-fiction. It inserted speeches, dialogue, even people and events to liven things up and/or to make a moral point. Or it obscured people and events, if that worked better.

Modern readers of ancient sources must always ask WHO wrote this, WHEN was it written, and what POINT did the author intend? Also, especially with anecdotes, look at the wider context. People are especially prone to take anecdotes at face value and treat them as isolated little tales. Yet CONTEXT IS KING.

A lot of our information about Alexander’s love life comes from Plutarch, either in his Life of Alexander or his collection of essays now called the Moralia. Another source is Curtius’s History of Alexander. And finally, Athenaeus’s Diepnosophistai or The Supper Party (really, The Learned Banqueters). All wrote during the Roman empire and had tropes and messages to get across.

Of the WOMEN associated with Alexander, I’m going to divide them into the historical and the probably fictional, or at least their relationship with Alexander was fictional.

Of the certain, we can count one mistress, three wives, and one probable secret/erased liaison.

Barsine is his first attested mistress for whom we have ample references across multiple sources. Supposedly, she bore Alexander a son (Herakles). Herakles certainly existed, but whether he was Alexander’s is less clear to me. As the half-Persian, half-Greek daughter of a significant satrap, she had no little influence. Monica D’Agostini has a great article on Alexander’s women, btw, in a forthcoming collection I edited for Colloquia Antiqua, called Macedon and Its Influences, and spends some time on Barsine. So look for that, probably in 2025, as we JUST (Friday) submitted the last of the proof corrections and index. Whoo! Anyway, Monica examines all Alexander’s (historical) women in—you guessed it!—their proper context.

Alexander also married three times: Roxane, daughter of the warlord Oxyartes of Sogdiana, in early 327. He married again in mid-324 in Susa, both Statiera (the younger), daughter of Darius, and Parysatis, youngest daughter of the king before Darius, Artaxerxes III Ochus. Yes, both at once, making ties to the older and the newer Achaemenid royal lines.

Out of all these, he had only one living son, Alexander IV (by Roxane)—although he got his women pregnant four times. If we can trust a late source (Metz Epitome), and I think we can for this, Roxane had a miscarriage while in India. Also, Statiera the younger was reputedly pregnant when Roxane, with Perdikkas’s help, killed her just a few days (or hours!) after Alexander died.

That’s 3 …who had baby #4?

Statiera the Elder, Darius’s wife. Netflix’s proposal of a liaison between them was not spun out of thin air. Plutarch—the same guy who tells us ATG never even looked at her—also tells us she died in childbirth just a week or three before the battle of Gaugamela, Oct. 1, 331. Keep in mind, Alexander had captured her right after Issos, Nov. 5, 333. Um … that kid wasn’t Darius’s. And if you think ANYbody would have been allowed to have an affair with such a high-ranking captive as the Great-King’s chief wife, I have some swampland in Florida to sell you. More on it HERE.

Now, for the probably fictional….

Kampaspe, I explained above.

Kallixena was supposedly hired by Philip and Olympias (jointly!) to initiate Alexander into sex, because he didn’t seem interested in women. (Yes, this little titbit is also in Rise.) Athenaeus reports the story as a digression on Alexander’s drinking, and how too much wine led to his lack of sexual interest. But within the anecdote, the reported reason for his parents’ hiring Kallixena was because mommy and daddy feared Alexander was “womanish” (gunnis).

Thaïs was linked to him by Athenaeus, almost certainly based on her supposed participation in the burning of Persepolis…which didn’t happen (or not as related; archaeology tosses cold water on it). Thaïs was Ptolemy’s mistress, and the mother of some of his children.

Athenaeus also mentions a couple unnamed interests, but all illustrate the same point: Alexander is too noble to steal somebody else’s love. Two are back-to-back: the flute-girl of a certain Theodoros, Proteas’ brother, and the lyre player of Antipatrides. The last is a boy, the eromenos of a certain Kalchis, a story related apart from the women, but with the same point.

Even more clearly fictional are his supposed encounters with the Amazon Queen Thalestris and Queen Kleophis of the Massaga (in Pakistan). Reportedly, as Onisikritos was reading from his history of Alexander at the court of King Lysimachos (who’d been a close friend, remember), Lysimachos burst out laughing when Onisikritos got to the Amazon story, and asked, “Where was I when this happened?”

Now, when it comes to his MEN/BOYS, the ice is thinner as no names are definitively given except Bagoas (in a couple sources, chiefly Curtius and Athenaeus). We also have a few generic references to pretty boys, as with Kalchis’s boyfriend mentioned above, and some slave boys offered by a certain Philoxenos, who he turns down, a story told by both Plutarch and Athenaeus.

Curtius alone suggests two more, but at least one is meant to show Alexander’s descent into Oriental Corruption(tm), so it’s possible Curtius made them up. At the very least, he used them for his own narrative purposes. Sabine Müller has a great article on this, albeit in German. Still, if you can read German: “Alexander, Dareios und Hephaistion. Fallhöhen bei Curtius Rufus.” In H. Wulfram, ed., Der Römische Alexanderhistoriker Curtius Rufus: Erzähltechnik, Rhetorik, Figurenpsychologie und Rezeption. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2016, 13-48.

Romans had a certain dis-ease with “Greek Love,” especially when it involved two freeborn men. Fucking slaves was fine; they’re just slaves. Citizen men with citizen boys…that’s trickier.

Curtius labels two youths “favorites,” a phrasing that implies a sexual affair. One is mentioned early in the campaign (Egypt) when Alexander is still “good”; the other after Alexander begins his slide into Persian Debauchery. These are Hektor, Parmenion’s son (good), and Euxinippos, described as being as pretty as Hephaistion, but not as “manly” (bad). Curtius employs Bagoas similarly, even claims he influenced imperial policy for his own dastardly goals. Gasp!

Yes, of course I’m being sarcastic, but readers need to understand the motifs that Curtius is employing, and what they really mean. Not what 21st century people assume they mean, or romantically want them to mean. (See my "Did Bagoas Exist?" post.)

What about Hephaistion? I’ve discussed him elsewhere in an article, but I’ll just remind folks that it’s nowhere made explicit until late sources, in large part because, by the time we meet Alexander and Hephaistion in the histories, they were adults, and any affair between them would be assumed to have occurred in the past, when they were youths. (See my “It’s Complicated” and a reply to them maybe being “DudeBros.”)

This is why we hear about Alexander’s interest in youths, not adult men. It would be WEIRD to the ancient mind (= Very Very Bad) if he liked adult men. In fact, by comparing Hephaistion to Euxinippos, Curtius slyly insinuates that maybe he and Alexander were still…you know (wink, wink). That’s meant to be a slam against Alexander (and Hephaistion)! Therefore, we cannot take it, in itself, as proof of anything. Alexander’s emotional attachment to Hephaistion, however, is not doubted by any ancient source.

So, all those people are attached to Alexander in our sources, but over half may not be real, or at least, may not have had a sexual relationship with him. There may be (probably are) some that simply didn’t make it into the surviving sources.

Yet I’ve mentioned before that we just don’t find sexual misconduct as one of Alexander’s named faults. Even Curtius and Justin must dig for it/make up shit, such as claiming Alexander actually used Darius’s whole harem of concubines or held a drunken revel through Karia after escaping the Gedrosian Desert. (Blue Dionysos and drag queens on the Seine at the Paris Olympics got nothing on his Dionysian komos!)

Drink, anger, hubris…he sure as hell ticked all those boxes. But not sex. In fact, a number of sources imply he just wasn’t that randy, despite his “choleric” temperament. Some of the authors credit too much drink (bad), others, his supreme self-control (good). He’s more often an example of sexual continence—as in the stories from Athenaeus related above. He also didn’t rape his captives, etc., etc.

Make of that what you like, but I find it intriguing.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Lovers of Alexander the Great#Alexander's Lovers#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Bagoas#Barsine#Kampaspe#Kallixena#Statiera#Parysatis#Roxane#Thais#sexuality of Alexander the Great#Alexander the Great and sex#Alexander the Great and women#Alexander the Great and men#Classics#ancient Greek sexuality#ancient Greece#ancient Macedonia#Alexander x Hephaistion#Alexander x Hephaestion#tagamamnon

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

As promised @bright-honey

Quick timeline for you.

6000 BCE: First fortified settlement at Ugarit 4000 BCE: Founding of the city of Sidon 4000 BCE - 3000 BCE: Trade contact between Babylos and Egypt 2900 BCE - 2300 BCE: First settlement of Baalbek 2750 BCE: The City of Tyre is founded 1458 BCE: Kadesh and Megiddo lead a Canaanite alliance against the Egyptian invasion by Thutmose III 1274 BCE: Battle of Kadesh between Pharaoh Ramesses II and King Muwatalli II of the Hittites 1250 BCE - 1200 BCE: Hebrew Tribes settle in Canaan 1200 BCE: Sea Peoples invade the Levant (they are important) 1115 BCE - 1076 BCE: Reign of Tiglath-Pileser I of Assyria who conquers Phoenicia and revitalizes the empire 1080 BCE: Rise of the Kingdom of Israel 1000 BCE: Height of Tyre's power 965 BCE - 931 BCE: Solomon is King of Israel 950 BCE: Solomon builds the first Temple of Jerusalem 722 BCE: Israel is conquered by Assyria 351 BCE: Artaxerxes III sacks Sidon 332 BCE: Alexander the Great sacks Baalbek and renames it to Heliopolis 332 BCE: Conquest of the Levant by Alexander the Great who destroys Tyre Jan 332 BCE - Jul 332 BCE: Alexander the Great besieges and conquers Tyre 64 BCE: Tyre becomes a Roman colony 37 BCE - 4 BCE: Reign of Herod the Great over Judea 30 BCE: Egypt becomes a province of the Roman Empire 30 BCE - 476 CE: Egypt remains a province of the Roman Empire 6 BCE - c. 30 CE: Life of Christ 637 CE: Muslim invasion of the Levant. The Byzantines are driven out. 115 CE- 117 CE: Rome occupies Mesopotamia 117 CE - 138 CE: Reign of Roman Emperor Hadrian

We can stop there because that is where the name Palestine comes from. I've omitted a LOT of history here. These are just some main points. Now for some visual aids.

Take these as you will. While archeology evidence has been found to support the Bible, I'm not aware of maps being found but people tend to forget it isn't a document of fiction, real people made it. That being said there is a LOT of evidence of Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are very interesting and I highly recommend reading up on them. It has been theorized and is probably true that it wasn't a singular people but different people coming from the sea as different words were used to describe each set that attacked, 8 different versions have been counted so far.

Of the 8, one that has been seen in recorded archeological history was dubbed Peleset or Pulasati. Historians generally identify them with the Philistines - note these are not the same people as Phoenicians according to historians and other experts.

In fact, the first appearance of the term Palestine but in the 5th century BCE and it was by a Greek historian referring to of a district of Syria called Palaistine between Phoenicia and Egypt. This term was used later by other Greek writers and later on by Roman writers. Though, the region was clearly 'Syria' not Palestine. In fact, let's look at a map or two.

So where did Palestine come from? Remember Roman Emperor Hadrian? Yeah, that asshole. Rome had conquered a large chunk of the known world.

The Jews didn't let themselves be conquered sitting down. The Bar Kochba Revolt was actually at the start going well for the Jews but sadly, the Romans took a scorched earth approach to them and it ended with the destruction of the second Temple, as well as renaming the area known as Judea to Palestina to effectively erase all Jewish connections to the land, going so far as naming it after the historical enemies of the Jews.

This is ALL PUBLIC HISTORY.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Highlights of the week.

Left the house.

Exercised.

Did several medical quests.

Made sweets at home.

Exchanged gifts.

Looked through Araia's version of Berenice (the one that had Farinelli as Demetrio).

Finished reading Salieri's Catilina. Loved it.

Finished reading and listening to Arne's Artaxerxes. Love the style, love the localisation (turning the generic prison into the London Tower and making it all reminiscent of Richard III).

Translated Act 2 Scenes 8-9 of La morte di Cesare. The arias in verse, even.

Started watching Alessandro nell'Indie.

Duolingo added stories to the Italian to French course.

Started reading Marco Bruto, a tragedy by Antonio Conti. It is one of the sources of, or has a common source with, La morte di Cesare.

Read cool fanfiction.

Read some of the second Philippic.

#[h]#mostly it is my sleep schedule giving me problems this week. but i am trying to make it better.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letter from Akhvamazda to Bagavant - Bactria

3 Sivan, year 11 (or 12) of Artaxerxes III, corresponding to 21 June 348 (or 10 June 347) BC

ink on leather written in Official Aramaic

The Khalil Collection

#Documents from Ancient Bactria#artifacts#artifact#historical#history#aramaic#ancient#ancient languages

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

÷

·

𒀭𒀀𒉣𒈾 ANUNNAKI ·

·

šakkanakki Bābili · King of Babylon ·

·

· ·

Sumu-abum

Sumu-la-El Sabium

Apil-Sin

Sin-Muballit Hammurabi

Samsu-iluna

Abi-Eshuh Ammi-Ditana

Ammi-Saduqa Samsu-Ditana

Dynasty I · Amorite · 1894–1595 BC

. .

.

Ilum-ma-ili Itti-ili-nibi

Damqi-ilishu

Ishkibal Shushushi

Gulkishar

DIŠ-U-EN Peshgaldaramesh

Ayadaragalama

Akurduana Melamkurkurra

Ea-gamil

Dynasty II · 1st Sealand · 1725–1475 BC

·

· ·

· ·

Gandash

Agum I Kashtiliash I

Abi-Rattash Kashtiliash II

Urzigurumash

Agum II Harba-Shipak

Shipta'ulzi

Burnaburiash I Ulamburiash

Kashtiliash III

Agum III

Kadashman-Sah

Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I

Kurigalzu I

Kadashman-Enlil I Burnaburiash II

Kara-hardash

Nazi-Bugash Kurigalzu II

Nazi-Maruttash

Kadashman-Turgu Kadashman-Enlil II

Kudur-Enlil

Shagarakti-Shuriash Kashtiliash IV

Enlil-nadin-shumi

Kadashman-Harbe II Adad-shuma-iddina

Adad-shuma-usur

Meli-Shipak

Marduk-apla-iddina I

Zababa-shuma-iddin

Enlil-nadin-ahi

Dynasty III · Kassite · 1729–1155 BC

. .

.

·

· ·

Marduk-kabit-ahheshu

Itti-Marduk-balatu Ninurta-nadin-shumi

Nebuchadnezzar I

Enlil-nadin-apli Marduk-nadin-ahhe

Marduk-shapik-zeri Adad-apla-iddina

Marduk-ahhe-eriba Marduk-zer-X

Nabu-shum-libur

Dynasty IV · 2nd Isin · 1153–1022 BC

· ·

· ·

·

Simbar-shipak

Ea-mukin-zeri Kashshu-nadin-ahi

.

Dynasty V · 2nd Sealand · 1021–1001 BC

· ·

· ·

Eulmash-shakin-shumi Ninurta-kudurri-usur I

Shirikti-shuqamuna

Dynasty VI · Bazi · 1000–981 BC

·

· ·

·

Mar-biti-apla-usur

Dynasty VII · Elamite · 980–975 BC

·

· ·

·

· ·

Nabu-mukin-apli Ninurta-kudurri-usur II

Mar-biti-ahhe-iddina Shamash-mudammiq

Nabu-shuma-ukin I Nabu-apla-iddina

Marduk-zakir-shumi I Marduk-balassu-iqbi

Baba-aha-iddina

.

.

.

at least 4 years

Babylonian interregnum

Ninurta-apla-X Marduk-bel-zeri

Marduk-apla-usur Eriba-Marduk

Nabu-shuma-ishkun Nabonassar

Nabu-nadin-zeri Nabu-shuma-ukin II

Dynasty VIII · E · 974–732 BC

· ·

·

·

·

Nabu-mukin-zeri Tiglath-Pileser III

Shalmaneser V Marduk-apla-iddina II

Sargon II Sennacherib

Marduk-zakir-shumi II Marduk-apla-iddina II

Bel-ibni Aššur-nādin-šumi

Nergal-ushezib Mushezib-Marduk

Sennacherib aka Sîn-ahhe-erība

Esarhaddon aka Aššur-aḫa-iddina

Ashurbanipal

Šamaš-šuma-ukin

Aššur-bāni-apli Sîn-šumu-līšir

Sîn-šar-iškun

Dynasty IX · Assyrian · 732–626 BC

. .

.

.

Nabopolassar

Nabû-apla-uṣur

Nebuchadnezzar II Nabû-kudurri-uṣur

Amēl-Marduk

Neriglissar

Nergal-šar-uṣur

Lâbâši-Marduk

Nabonidus

Nabû-naʾid

Dynasty X · Chaldean · 626–539 BC

. ·

. ·

. ·

. ·

. ·

. ·

Cyrus II the Great · Kuraš · 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 Kūruš ·

Cambyses II · Kambuzīa ·

Bardiya · Barzia ·

Nebuchadnezzar III · Nabû-kudurri-uṣur ·

·

Darius I the Great · Dariamuš · 1st reign

·

Nebuchadnezzar IV · Nabû-kudurri-uṣur

Darius I the Great · Dariamuš · 2nd reign

·

Xerxes I the Great · Aḫšiaršu · 1st reign

·

Shamash-eriba · Šamaš-eriba

Bel-shimanni · Bêl-šimânni

·

Xerxes I the Great · Aḫšiaršu · 2nd reign

·

Artaxerxes I · Artakšatsu

Xerxes II

Sogdianus

Darius II

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes III

Artaxerxes IV

Nidin-Bel

Darius III

Babylon under foreign rule · 539 BC – AD 224

Dynasty XI · Achaemenid · 539–331 BC

·. ·

·. ·

·. ·

·. ·

·. ·

·.

Alexander III the Great · Aliksandar

Philip III Arrhidaeus · Pilipsu

Antigonus I Monophthalmus · Antigunusu

Alexander IV · Aliksandar

Dynasty XII · Argead · 331–305 BC

·.

·.

·.

·.

·.

Seleucus I Nicator · Siluku

Antiochus I Soter · Antiʾukusu

Seleucus · Siluku

Antiochus II Theos · Antiʾukusu

Seleucus II Callinicus · Siluku

Seleucus III Ceraunus ·

Antiochus III the Great · Antiʾukusu

Antiochus ·

Seleucus IV Philopator · Siluku

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ·

Antiochus

Antiochus V Eupator

Demetrius I Soter

Timarchus

Demetrius I Soter

Alexander Balas

Demetrius II Nicator

Dynasty XIII · Seleucid · 305–141 BC

· ·.

. · ·

. · ·

. · ·

· ·.

· ·.

Mithridates I

Phraates II

Rinnu

Antiochus VII Sidetes

Phraates II

Ubulna

Hyspaosines

Artabanus I

Mithridates II

Gotarzes I

Asi'abatar

Orodes I

Ispubarza

Sinatruces

Phraates III

Piriustana

Teleuniqe

Orodes II

Phraates IV

Phraates V

Orodes III

Vonones I

Artabanus II

Vardanes I

Gotarzes II

Vonones II

Vologases I

Pacorus II

Artabanus III

Osroes I

Vologases III

Parthamaspates

Vologases IV

Vologases V

Vologases VI

Artabanus IV

Dynasty XIV · Arsacid · 141 BC – AD 224

· 9 centuries of Persian Empires · until AD 650

Trajan in AD 116

mid-7th-century Muslim Empire

·.

·.

·.

1921 Iraqi State

·.

·.

1978 · 14th of February · Saddam Hussein

·.

·.

2009 · May · the provincial government of Babil

·.

·.

·.

·.

. ·

·.

·.

·.

·.

so many kings

and just one queen

semiramis

·· ·

· SEMIRAMIS ·

··

.

.

.

.

···· Βαβυλών ··· ΒΑΒΥΛΩΝ ····

Babylonia

Gate of the Gods

بابل Babil 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 · 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 · 𐡁𐡁𐡋 · ܒܒܠ · בָּבֶל

Iraq · 55 miles south of Baghdad

near the lower Euphrates river

.

.

.

.

.

#king#of#babylon#semiramis#assur#uruk#mar-biti-apla-usur#marduk-apla-usur#mesopotamia#annunaki#anunnaki

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

They achieved the impossible!

TEHRAN – It took 45 years for a Sassanid-era (224–651) petroglyph to be deciphered, ILNA reported on Saturday.

Forty-five years after its discovery in Naqsh-e Rostam, a royal rock-hewn necropolis in southern Fars province, the Sassanid petroglyph has been translated, Iranian archaeologist Abolhassan Atabaki said.

Raising goats in pastures is the subject of the petroglyph, he mentioned.

The petroglyph also mentions a nearby hydro structure that the residents of the region used for drinking and cattle water, he noted.

This rock drawing is one of the most important and largest petroglyphs discovered by the archaeologists during their previous survey of the area, he explained.

The petroglyph has been homogenized by rainwater because it was exposed to the open air, causing a large number of limestone sediments to slowly form a layer of the upper surface, resulting in the destruction of stone inscriptions, and the loss of parts of the letters, he added.

One of the wonders of the ancient world, Naqsh-e Rostam, is home to spectacular massive rock-hewn tombs and bas-relief carvings. Moreover, it embraces four tombs where Persian Achaemenid kings are laid to rest, believed to be those of Darius II, Artaxerxes I, Darius I, and Xerxes I (from left to right facing the cliff), although some historians are still debating this.

The Achaemenid necropolis is situated near Persepolis, itself a bustling UNESCO World Heritage site near the southern city of Shiraz. Naqsh-e Rostam, meaning “Picture of Rostam” is named after a mythical Iranian hero who is most celebrated in Shahnameh and Persian mythology. Back in time, natives of the region had erroneously supposed that the carvings below the tombs represent depictions of the mythical hero.

There are stunning bas-relief carvings above the tomb chambers that are similar to those at Persepolis, with the kings standing on thrones supported by figures representing the subject nations below. There are also two similar graves situated on the premises of Persepolis probably belonging to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III.

Beneath the funerary chambers are dotted with seven Sassanian eras (224–651) bas-reliefs cut into the cliff depict vivid scenes of imperial conquests and royal ceremonies; signboards below each relief give a detailed description in English.

At the foot of Naqsh-e Rostam, in the direction of the cliff face, stands a square building known as Ka’beh-ye Zardusht, meaning Kaaba of Zoroaster. The building, which is roughly 12 meters high and seven meters square, probably was constructed in the first half of the 6th century BC, although it bears a variety of inscriptions from later periods. Though the Ka’beh-ye Zardusht is of great linguistic interest, its original purpose is not clear. It may have been a tomb for Achaemenian royalty or some sort of altar, perhaps to the goddess Anahiti, also called Anahita believed to be associated with royalty, war, and fertility.

In many ways, Iran under Sassanian rule witnessed tremendous achievements in Persian civilization. Experts say that the art and architecture of the nation experienced a general renaissance during Sassanid rule. In that era, crafts such as metalwork and gem engraving grew highly sophisticated, as scholarship was encouraged by the state; many works from both the East and West were translated into Pahlavi, the official language of the Sassanians.

Of all the material remains of the era, only coins constitute a continuous chronological sequence throughout the whole period of the dynasty. Such Sassanian coins have the name of the king for whom they were struck inscribed in Pahlavi, which permits scholars to date them quite closely.

The legendary wealth of the Sassanian court is fully confirmed by the existence of more than one hundred examples of bowls or plates of precious metal known at present. One of the finest examples is the silver plate with partial gilding in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The dynasty was destroyed by Arab invaders during a span from 637 to 651.

The ancient region, known as Pars (Fars), or Persis, was the heart of the Achaemenid Empire founded by Cyrus the Great and had its capital in Pasargadae. Darius I the Great moved the capital to nearby Persepolis in the late 6th or early 5th century BC. Alexander the Great defeated the Achaemenian army at Arbela in 331 and burned Persepolis apparently as revenge against the Persians because it seems the Persian King Xerxes had burnt the Greek City of Athens around 150 years earlier.

Persis became part of the Seleucid kingdom in 312 after Alexander’s death. The Parthian empire (247 BC– 224 CE) of the Arsacids (corresponding roughly to the modern Khorasan in Iran) replaced the Seleucids' rule in Persis during 170–138 BC. The Sasanid Empire (224 CE–651) had its capital at Istkhr. Not until the 18th century, under the Zand dynasty (1750–79) of southern Iran, did Fars again become the heart of an empire.

Source:https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/483667/Sassanid-petroglyph-deciphered-after-45-years

#Iran#arcaelogy#Iranian archaeologists#Naqsh-e Rostam#Sassanid petroglyph#Zoroaster persia#UNESCO World Heritage#UNESCO#fars province#Iran Tehran#Achaemenid necropolis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artaxerxes III: The Ruthless Reclaimer of the Achaemenid Empire

Rise to Power The royal court of Persia was a labyrinth of intrigue, ambition, and lethal rivalries. Artaxerxes III was born as Ochus, the youngest son of Artaxerxes II and Queen Stateira. His father’s reign, spanning over four decades, was marred by internal strife, including rebellions led by his own sons. The multiplicity of heirs, each born to different wives and concubines, created an…

0 notes

Photo

A Sculpture Gallery in Rome at the Time of Agrippa by Lawrence Alma-Tadema + Memnon of Rhodes by Dalton Thomas Rix + Coinage of Memnon of Rhodes, Mysia. Mid 4th century BC

Memnon's career in Persian service had a strange start. In fact, the Persians needed his brother Mentor to defend the Troad (the northwest of modern Turkey), and gave him land in that region. Not much later, Mentor was made Persian supreme commander in the West and married Barsine, the daughter of the satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia, Artabazus, who married a sister of the Rhodians.

Memnon joined his brother and shared in his adventures. For example, when Artabazus rebelled against king Artaxerxes III Ochus in 353 or 352, they assisted him. The revolt was not successful, and Artabazus and Memnon were forced to flee to Pella, the capital of Macedonia. Here, they met king Philip, the young crown prince and the philosopher Aristotle of Stagira. ... The Persians dug themselves in on the banks of the river Granicus, the modern Biga Çay. If Alexander moved to the south, where he wanted to liberate Greek towns like Ephesus and Miletus, they could attack his rear; if he moved to the east to drive them out, their position was strong enough to withstand the attack of a larger army. However, the Persians were defeated (June 334).

Darius, however, understood that Memnon had been right about his strategy. He ordered the Persian navy to move to the Aegean sea; it had to come from Egypt, Phoenicia, and Cyprus, and it arrived three days too late to prevent the capture of Miletus. However, Memnon, now appointed supreme commander, managed to keep the Persian naval base Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum) for a long time and was able to evacuate the town without unacceptable losses. In fact, Halicarnassus was the last Persian victory: after the siege, Alexander needed reinforcements, and it gave the Persians the opportunity to regroup.

—Memnon of Rhodes at Livius.org

Memnon, one of King Darius’s generals against Alexander, when a mercenary soldier excessively and impudently reviled Alexander, struck him with his spear, adding, I pay you to fight against Alexander, not to reproach him.

—Plutarch, Morals vol. 1

#Memnon of Rhodes#Dalton Thomas Rix#Lawrence Alma-Tadema#King Philip II of Macedon#Darius III#Aristotle#Laocoön#Alexander the Great#Plato

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

What if Cyrus III? Choose Your Own Alt History Live

This is audio from the live event with Sariel and Umberto from So You Think You Can Rule Persia last year. I wrote a wildly over complicated Choose Your Own Adventure script about alternate histories if Cyrus the Younger defeated Artaxerxes II.Download So You Think You Can Rule Persia Patreon | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram What if Cyrus III? Choose Your Own Alt History Live

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

HANDLING OF CONFLICTS AND THE SACRIFICES TO MAKE

[Leadership style of Nehemiah 5]

"ABOUT this time some of the MEN AND THEIR WIVES RAISED A CRY OF PROTEST AGAINST THEIR FELLOW JEWS."

Nehemiah 5:1 (NLT)

• The Apostles in the early church were able to quell the similar problem when it started, likewise Nehemiah in his leadership assignment.

- Note: in most cases, the purpose of such confusion in your camp is to distract you and the people, that the work at hand might be truncated or stopped.

- This strategy of stirring disagreements and confusions in you camp is one of the major instruments of distraction which the devil usually use scattering a ministry work.

- If such a problem is not properly handled and managed, it could break the spirit of unity and oneness, team spirit, with which the people had been working.

- The problem should be handled with prayer and wisdom:

(a) Ask God for wisdom on how to do it (James 1:5).

(b) Do not be partial or take side with any faction, let there be Justice, fair treatment of the aggrieved party (Nehemiah 5:9-13).

(c) Do things According to the principles of the Word of God—the Bible (Acts 6:2-4).

(d) Whatever step you wanted to take, pray on it and submit to the leadership of the Holy Spirit (Romans 8:24; 1 Thessalonians 5:17).

(e) If there is any correction to be made, to straighten things, right the wrong, and settle the problem or dispute; let that starts from you:

"I MYSELF, AS WELL AS MY BROTHERS AND MY WORKERS, have been lending the people money and grain, BUT NOW LET US STOP THIS BUSINESS OF CHARGING INTEREST" (Nehemiah 5:10 NLT).

- If any change would happen in an organization, the change has to start from the leadership.

- Nehemiah himself was guilty of what the people were complaining of, he did acknowledge it and decided to change. HE said the change would start from him and those who are in the leadership.

THIS is the leadership pattern taught by Jesus Christ and such is the one God expected in the church (Mark 10:42-45).

(f) Make sure the aggrieved party received fair justice and then follow the matter up till you have completely resolved it. Do not sweep it under the carpet, doing that could make it a time bomb (Nehemiah 5:13).

• About Leadership

(i) At the onset of your Ministry or assignment, if you are the one who pioneered the work, you need to Sacrifice your comfort and some of the benefits you ought to get—for the growth of the work.

(ii) Ministry would take everything from you, when you started, and later give the things you had sacrificed and things you may be desiring.

YOU Sacrifice whatever you had as a seed to take off in the Ministry work.

(iii) Ministry work would cost you something that is precious and important to you, which the pain would be felt by you.

NOTE: If the ministry or assignment you wanted to start, the vision you are pursuing, would not cost you anything tangible or precious; it means, it does not worth pursuing.

- Ministry may cost you; your Business, career, position of authority, attainments in life and royalty—a royal status (Philippians 3:18).

• About the self

WHEN God instructed me to pioneer a church, I had no money, I was a bachelor, yet to marry then, and the only valuable thing I had was a shop which I let out to someone. I told God, If He provided a place to start the church, I would sell the shop. God did answer the prayer and I sold the shop, used the money to buy chairs, pulpit, and other basic things needed to commence the work.

WHEN the work started, I did not collect any salary from the church money. I asked them to be giving me transport fare only, that I would trust God for my feedings, house rent, and other utility Bills, because I was on full time.

- In Nehemiah's account, he said:

14 FOR the entire twelve years that I was governor of Judah—from the twentieth year to the thirty-second year of the reign of King Artaxerxes—NEITHER I NOR MY OFFICIALS DREW ON OUR OFFICIAL FOOD ALLOWANCE.

15 THE FORMER GOVERNORS, in contrast, HAD LAID HEAVY BURDENS ON THE PEOPLE, demanding a daily ration of food and wine, besides forty pieces of silver. EVEN THEIR ASSISTANTS TOOK ADVANTAGE OF THE PEOPLE. But BECAUSE I FEARED GOD, I DID NOT ACT THAT WAY. 16 I also devoted myself to working on the wall AND REFUSED TO ACQUIRE ANY LAND. And I required all my servants to spend time working on the wall. 17 I ASKED FOR NOTHING, even though I regularly fed Jewish officials at my table, besides all the visitors from other lands! 18 The provisions I paid for each day included one ox, six choice sheep or goats, and a large number of poultry. And every ten days we needed a large supply of all kinds of wine. YET I REFUSED TO CLAIM THE GOVERNOR'S FOOD ALLOWANCE BECAUSE THE PEOPLE ALREADY CARRIED A HEAVY BURDEN. 19 Remember, my God, all that I have done for these people, and bless me for it" (Nehemiah 5:14-19 NLT).

• At the onset of the Ministry work

- You may need to sacrifice your COMFORT and defer your gratifications—satisfactions and wishes.

- The reason being that, the work, the Ministry, is still Young and the income is meagre, the burden of your personal expenses should not be put on the little income.

- Give precedence to the Ministry needs before your personal needs. If your personal need and the Ministry need clashed, give consideration and precedence to the Ministry need first.

• About the self

When I newly married, we had accommodation problem. My wife [who was pregnant then] and I did put up with another family, a minister of God. We were trusting God to raise the money needed for the accommodation. Coincidentally, we had some money in the church purse which we wanted to use for a mini project. Somehow, the pastor we were staying with got to know about it. He said what am I doing, I should go ahead and use the money to rent a house for my family. I said the money belongs to the church, it is God's money, and not my personal money.

I did not take to his counsel although he has been in the ministry several years ahead of me. In fact, he was one of the people I received counsel from when I wanted to start the ministry work.

- The truth is, God will test your motives and faithfulness. What happened to me was a test, God eventually provided the accommodation needed for my family.

• Admonishments

- Know your size in the Ministry. Someone said: "life is in phases and men are in sizes."

YOU must know your level, there is a time for one pair of shoes, a time for only one suit or no suit, a time to live in one room apartment, and a time to live in a flat. THERE is a time for everything under the sun (Ecclesiastes 3:1).

EAT your size, do not eat more than what you can afford.

PUT or enroll your children in the school you can afford.

LIVE in a house you can afford. Live a size per time.

- Some have eaten their future in ministry, because they do not know their sizes. They wanted to arrive overnight. They could not control their appetites. They have wrong appetites.

- You must know your size, your level, and the phase you are.

- If you bite more than what you can chew, you may be choked in the process.

REMEMBER, it gets better in the Ministry work, but it may be rough at the onset—the beginning. Especially if you are pioneering a new work—new ministry.

• You will not fail in Jesus' name.

Peace!

TO BE CONTINUED

#christianity#gospel#christian living#christian blog#jesus#the bible#devotion#faith#my writing#prayer

0 notes

Photo

Achaemenid Kings List & Commentary

The Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) was the first great Persian political entity in Western and Central Asia which stretched, at its peak, from Asia Minor to the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia through Egypt. It was founded by Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) whose vision of a vast, all-inclusive Persian Empire was, more or less, maintained by his successors.

The Persians arrived in the region of modern-day Iran as part of a migratory group of Aryans (meaning “noble” or “free” and referencing a class of people, not a race). The Aryans – made up of many tribes such as the Alans, Bactrians, Medes, Parthians, and Persians, as well as others – settled in the area which became known as Ariana (Iran) – “the land of the Aryans”. The tribe which eventually became known as the Persians settled at Persis (modern-day Fars) which gave them their name.

Artaxerxes V (r. 330-329 BCE) was the short-lived throne name of Bessus, satrap of Bactria, who assassinated Darius III and proclaimed himself king. Alexander the Great found the dead or dying Darius III (the original accounts vary on this) in a cart where Bessus had left him and gave him a proper burial with all honors. Afterwards, Alexander had Bessus executed and took for himself the honor of the title Shahanshah, the king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire.

Conclusion

Although the Achaemenid Empire was no longer what it had been under Darius I, it was still intact when Alexander conquered it. He attempted a synthesis of Greek and Persian cultures by marrying his soldiers to Persian women, elevating Persian officers to high rank in his army, and comporting himself as a Persian king. His efforts were not appreciated by the Greek/Macedonian army and, after his death in 323 BCE, his vision was abandoned. Since he had named no clear successor at the time of his death, his generals went to war with each other to claim supremacy.

These wars (known as the Wars of Diadochi, 322-275 BCE), resulted, in part, in the rise of the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) under Alexander's general Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE). The Seleucid Empire occupied approximately the same regions as the Achaemenid and, though it rose to a position of strength, gradually lost territory, first to the Parthians and then later to Rome. The Seleucids were succeeded by the Parthian Empire (247 BCE- 224 CE) which fell to the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). The Sassanians revived the best aspects of the Achaemenid Empire and would become the greatest expression of Persian culture in the ancient world.

The Sassanian Empire preserved the culture of the Achaemenids and, even after its fall to the invading Muslim Arabs, this culture would endure and spread throughout the ancient world. Many aspects of life in the modern day, from the seemingly mundane of birthday parties, desserts, and teatime to the more sublime of monotheism, mathematics, and aspects of art and architecture, were developed by the Sassanians drawing on the model of the Achaemenid Empire.

Continue reading...

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

Politically, it always made sense that Alexander married the daughters of Darius III and Artaxerxes III. It even seems like a common move. But didn't the Greeks hold themselves to a higher standard than marrying a foreigner? Even if they didn't consider the Persians outright barbarians, they were foreigners and a conquered enemy. It seems also stranger that the marriage to Roxanna happened since she seems to be far from the ideal bride

What I am trying to ask is, didn't the Greeks expect Alexander to marry a Greek woman with a proper Greek wedding? I can grasp what Alexander had in mind with the Suda weddings, but it seems very strange that this “ethnic” “Greek” element is not present

ALEXANDER & MARRIAGE

(and what was Greek “ethnicity”)

First, let me link to 2 other posts that deal with Alexander and marriage, but don’t address the ethnic element except obliquely.

Argead Inheritance and Alexander’s (lack of) heirs

Why did it take so long for Alexander to father an heir?

A couple interpretive levels present here:

Greek ethnicity and marriage pre- and post-Persian wars

Macedonian expectations for (polygamous) royal marriage

Roman attitudes, especially Late Republic (Antony and Cleopatra in particular)

I want to note that Macedonians were regarded by Greeks—and regarded themselves—as a separate people. Today in Greece, The Macedonian Question is a hot-button issue that reflects MODERN politics and nationalism. We can now say (finally have enough epigraphical evidence) that the ancient Macedonians appear to have spoken a form of northern Doric Greek, distinct from Thessalian and Epirote forms, so by modern definitions, we’d consider them Greek.

But our ancient sources often speak of the Greeks and Macedonians as if they were different, if related, peoples. Certainly, while they shared many similarities, Macedonians were distinct, and didn’t especially want to BE Greeks. I tried to reflect that ancient attitude in Dancing with the Lion.

Furthermore, the tendency to glomp all of ancient Greece together reflects Early Modern ideas of nationhood. THERE WAS NO ANCIENT NATION CALLED GREECE. That’s one of the first things I teach in my “Intro to Greek History” class. 😊 “Greece” (Hellas)* was simply a landmass. In fact, the ancient Greeks don’t appear to have referred to themselves as “Greek”—an ethnicity—until the Persian invasion.** Ethnicities were “Athenian,” “Spartan,” “Corinthian,” “Theban,” etc. Independent city-states with their own laws, coinage, magistracies, etc. In addition, they recognized larger dialect groupings: Ionic-Attic, Doric, Aeolic, then subdivisions within that. These larger dialect groupings also shared social customs and dress, as well as distinct religious cult. So, for instance, you won’t find many/any temples to Hephaistus in Doric areas, and the peplos became associated with Doric women while Ionic-Attic wore the chiton. Even the later Roman province was called Achaia and didn’t include a lot of areas they’d have considered “Greek” (Hellene).

It took being invaded by a true “Other” (Persia) before they started to define themselves as Hellenes versus Barbaroi (not-Greeks)—yet they didn’t always agree on the “edges.” It’s not until late that we find Thessaly included at the Olympic games. Epiros was sorta-Greek, as they could claim Achilles, but both Epiros and Thessaly had semi-monarchic political systems not in line with accepted Greek norms (the polis). Macedon was even further afield, being a full-on monarchy. The Macedonian royal family claimed to be Greeks ruling over a non-Greek but cousin people; the (fictional) eponymous founder, Makedon, was a nephew of the equally fictional forefather of the Greeks: Hellen. The “Greekness” of the royal family was also a fiction, invented by Alexander I—in the wake of the Greco-Persians Wars, note.

Now, again, by modern criteria, we’d probably consider the Macedonians blended but largely Greek. Yet it’s important to recognize the difference between now and then—something I get frustrated over in modern arguments. (Which can be quite strident.)

Anyway, it’s during/after the Greco-Persian Wars that barbaros came to acquire a more negative connotation. In the Archaic Age, it was a neutral term. Barbaros simply meant “non-Greek speaker” or “the bar-bar people” (“those whose language sounds like bar-bar-bar-bar to us”). It’s not complimentary, but it’s also not as negative as it came to imply later.

Furthermore, in the Archaic Age, plenty of Greek men, including Athenians, married non-Greek women—often to cement business ties, especially in Asia Minor, Thrace, and Italy. In many city-states, these children were citizens if their father was. It’s only in a few city-states that both parents had to be citizens, such as Sparta and, later, Athens. These developments are either very late Archaic or Classical, in order to restrict citizen privileges.

IOW, even in Greece proper, marrying a Greek woman wasn’t important except in a few places, specifically to limit citizenship for economic reasons. Notions of ethnic purity as we understand it weren’t a thing. Yes, even in Sparta. Full Spartans excluded other Lakonians, who spoke the exact same language and kept the exact same religious cult. In short, all Spartiátēs were Lakedaimonians (the city-state) and Lakonians (ethnicity), but not all Lakonians and Lakedaimonians were Spartiátēs. E.g. Spartiátēs were the aristocratic class. (The alt-right really needs to figure that out … except, yeah, they don’t want to as it would mess with their biases.)

When Herodotos included “blood” in his famous definition of Greekness (to speak the Greek language, worship the Greek gods, keep Greek customs, have Greek blood—and to live in a polis), “blood” meant from DADDY. This relates a bit to ancient views that a mother was just a field to be plowed for male seed. Ergo, children inherited from their fathers. (This belief was not universal, especially later, but it informed early Greek thought, and thus, inheritance laws.)

NOW … Macedonia.

Macedonian kings practiced royal polygamy for political reasons. That means Alexander wasn’t the first to marry non-Macedonians. In fact, of Philip’s 7 wives, only Kleopatra (the last) is *distinguished* as a Macedonian. Even Phila is called Elimeian (Upper Macedonian) by Statyrus. Olympias was Epirote (Greek), Philina and Nikesepolis were Thessalian (Greek), Audata was Illyrian (non-Greek), and Meda was Getai Thracian (non-Greek).

Was there objection to Philip’s marrying the latter two? Our evidence doesn’t say. In the case of Audata, he may not have had a choice; marrying her was probably part of the peace deal with Bardyllis shortly after Philip came to the throne. Later, Meda was just “wife #6” so it’s unlikely anyone cared. Hooplah over Kleopatra as a “pure” Macedonian at their wedding was meant to diss Olympias, and thus, Alexander; it wasn’t a serious objection to Macedonian kings marrying non-Macedonian/Greek women. Especially as Epirote Olympias was Greek.

Things get even MORE complicated when we look at Alexander’s weddings. How much of the supposed objection to them is Macedonian, and how much from later Greek and Roman authors’ horror over “Orientals” generally? I’d submit Curtius’s bitching about Roxana is very ROMAN. Plutarch turns it all into a love affair, but has his own reasons for that. It’s really hard to know what to make of complaints. Was his taking of Persian brides itself offensive, or just as part of his overall adoption of Persian dress and customs? I’m sure there was no collective “Macedonian attitude” so much as various camps into which this or that solder fell—from strict Traditionalists like Kleitos through to Hephaistion, who is portrayed as supporting ATG’s Persianizing.

Last, I’ll also submit another reason we find anxiety about “foreign” wives in our Alexander histories: Octavian whipping up Roman nationalist fear of Cleopatra (VII) and Antony’s marriage to her. Cleopatra became a stand-in for the Wicked Wild Oriental East and corruption of Good Roman Virtues. She’s that “Egyptian woman” (yes, even though she was technically Greco-Macedonian). Caesar may have entertained an affair with her and nursed Alexander comparisons, but between Caesar and Octavian/Antony (in fact partly because of Caesar), Alexander imitatio had fallen out of favor and would stay so for a while in the early Republic.

Curtius would have been writing (we think; dating him is tricky) under the late Julio-Claudians. So yeah, them furrun’ wimmen gotta be watched out for! Marrying Roxane was part of Alexander’s seduction by the East after the death of Darius. That Roxane was not a princess (like Statiera) made it even worse. She was a TRUE barbarian.

Add to that, polygamy wasn’t understood by either Greek or Roman writers. Plutarch tries to explain Philip’s later marriage to Kleopatra as divorcing Olympias first (as does Justin) because Romans (and Greeks) used divorce. Polygamy was, to their minds, an eastern vice. So Alexander taking (unequivocably) three wives was oriental, proof of his corruption.

Hope this helps to contextualize what we’re looking at here, and the problems involved reading the sources.

If some Macedonians objected to Alexander marrying Roxane (and they probably did), it would have been because she wasn’t high-born enough for a (first) wife, and/or she was TOO foreign. But as that marriage got them out of Baktria/Sogdiana, it looked just like things Philip had done.

Later objections involved whether Roxane’s child should be accepted as heir over Arrhidaios. That’s a different kettle of fish. It’s clear that status of the mother was important in Macedonian inheritance squabbles even before Alexander. While some Macedonians preferred the mentally unfit Arrhidaios over the child of any “captive,” others did not. They wanted a son of Alexander.

So who he married mattered rather less than who was put forward to inherit the diadema.

---------------------------

* “Greek” is from the Latin Graecae, a specific Greek tribes, just like the Romans are a specific Latin tribe. The Romans just applied it to everybody on the peninsula. The Greeks called themselves “sons of Hellen”: Hellenes. The official name of the country even today is Hellas, not Greece. Hellen isn’t to be confused with the (feminine) Helen, btw. Hellen was a son of Deukalion, Helen the wife of Menelaus, and later mistress of Paris.

** For an excellent, if rather…er, thick discussion, with lots (and I mean LOTS) of ancient evidence, see Jonathan Hall’s Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity, which addresses the question of when the ancient Greeks became “Greeks.”

#asks#Alexander the Great#Greekness#ancient Greek ethnicity#Roxane#Barsine#ancient Macedonian ethnicity#Alexander's marriages#Philip's marriages#Macedonian polygamy#Alexander imatatio#Classics#Jonathan Hall#tagamemnon

20 notes

·

View notes