#Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

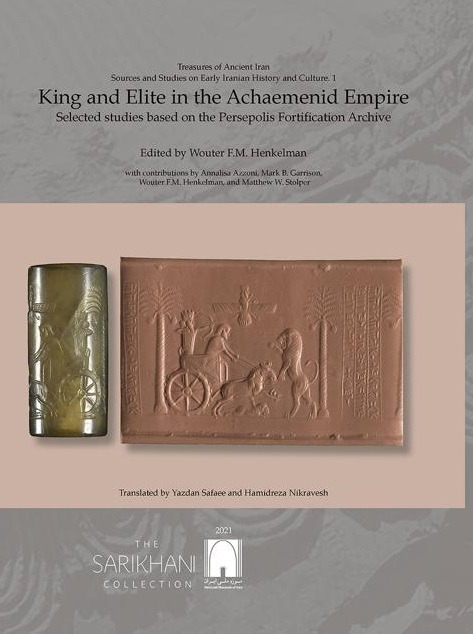

An Iranian volume with studies of Westen scholars on the ancient Persian Empire based on the Persepolis “Fortification Tablets”

“According to the National Museum of Iran, the book ” King and élite in the Achaemenid empire Selected studies based on the Persepolis Fortification Archive” has been published in Tehran. Jebrael Nokandeh, director of the National Museum, said: ” As the first volume of the series Treasuries of Ancient Iran: Sources and Studies on Early Iranian History and Culture, this volume is a translation of ten articles published in English on various occasions. He added what brings all these articles together is their common theme of the King’s network of relations with the dominant ethno-class, a group of individuals who formed the main body of power structure during the Achaemenid period. He emphasized it is also noteworthy that the focus of all these articles is on the analysis of information that the Persepolis Fortification Archive, one of the most important sources of Achaemenid history, provides. According to Ms. Ghafouri, head of the publishing department, the publication of this book is an attempt to transfer the results of international studies to Persian speakers, given the return of a significant portion of Persepolis tablets from Chicago to the National Museum of Iran. The book consists of 10 chapters in 4 thematic sections and is published in full color in 512 pages and 500 copies. The editor of the volume is Wouter F.M. Henkelman with contributions by Annalisa Azzoni, Mark B. Garrison, Wouter F.M. Henkelman, and Matthew W. Stolper. The chapters were translated by Yazdan Safaee and Hamidreza Nikravesh

The chapters are as follows: The King and the royal court Garrison, M.B. 1996, “A Persepolis Fortification Seal on the Tablet MDP 11 308 (Louvre Sb 13078)”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 55, 15–۳۵٫ Henkelman, W.F.M. 2010, “Consumed before the King.” The Table of Darius, that of Irdabama and Irtaštuna, and that of his Satrap, Karkiš”, in: B. Jacobs & R. Rollinger (eds.), Der Achämenidenhof (Classica et Orientalia 2), Wiesbaden: 667-775. Azzoni, A., 2017, “The empire as visible in the Aramaic documents from Persepolis”, in: B. Jacobs, W.F.M. Henkelman & M.W. Stolper (eds.), Verwaltung im Perserreich – Imperiale Muster und Strukturen / Administration in the Achaemenid Empire – Tracing the Imperial Signature, Wiesbaden: 455- 468. Religion and royal ideology Henkelman, W.F.M. 2011, Parnakka’s Feast: šip in Pārsa and Elam, in: J. Álvarez-Mon & M.B. Garrison (eds.), Elam and Persia, Winona Lake: 89-166. Glimpses of the Achaemenid élite Garrison, M.B. 1991, Seals and the Elite at Persepolis: Some Observations on Early Achaemenid Persian Art, Ars Orientalis 21, p. 1–۲۹٫ Henkelman, W.F.M. 2011, Of Tapyroi and tablets, states and tribes: the historical geography of pastoralism in the Achaemenid heartland in Greek and Elamite sources, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 54.2: 1-16. Garrison, M.B. 2011, Notes on a Boar Hunt, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 54; 17–۲۰٫ Garrison M.B & W.F.M. Henkelman. 2020., The seal of prince Aršāma: From Persepolis to Oxford, in: C. Tuplin and J.Ma, eds., Aršāma and his world: vol. 2: bullae and seals, Oxford: 46–۱۶۶٫ The King is dead Henkelman, W.F.M. 2003, An Elamite Memorial: the šumar of Cambyses and Hystaspes, in: W. Henkelman & A. Kuhrt (eds.), A Persian Perspective: Essays in Memory of Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg (Achaemenid History 13), Leiden: 101-172. Stolper, M.W. From the Persepolis Fortification Archive Project, 4: ‘His Own Death’ in Bisotun and Persepolis, ARTA 2015.002 [28 pp.].”

Source: https://irannationalmuseum.ir/en/a-new-book-on-persepolis-fortress-archive/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another review of the same book of Thomas Harrison on the ancient Greek Classics as source for the Persian Empire and the “New Achaemenid historians”

“Thomas Harrison, Writing Ancient Persia

The International Journal of Asian Studies, 2012

Takuji Abe

Writing Ancient Persia .

By Thomas Harrison. London: Bristol Classical Press, 2011. Pp. 190.

ISBN 10: 071563917X; 13: 9780715639177.

Reviewed by Takuji Abe, Kyoto Prefectural University

E-mail [email protected]

doi:10.1017/S1479591412000095

“Herodotus was the authority for Persian history,” Arnaldo Momigliano retrospectively mentioned, looking back at his youth. “It was a dogma that if you wanted to study Persian history you had to know Greek.” He went on to say, “Persian history is still in the hands of Herodotus.”1

Today, however, Herodotus is no longer the authority figure he was when Momigliano delivered his lecture in 1961/62. The study of Persian history, especially its association with Greek literature, was involved in a serious dispute in the 1980s, the age of post-colonialism. The Achaemenid History Workshop, which was organized in 1981, actively questioned the validity of Greek sources for Persian studies. Its initiator, Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, published her ideas to that effect in the early volumes of the proceedings of the workshop’s conferences. The traditional picture of Persian history was, according to Sancisi-Weerdenburg, a one-sided or “Hellenocentric” image, due to its exceeding dependency on Greek historiography; it was full of clichés such as decadence, harem-life, luxury and intrigues. She urged us to “dehellenise and decolonialise” this “Europe-centered perception,” by laundering prejudiced Greek texts.2 Is this method, which is extremely sceptical and distrustful of Greek sources, nevertheless really useful for understanding Persian history? In his book, Thomas Harrison intends to critically examine this new approach, which has come into being over the last thirty years.

This essay consists of a preface (pp. 11 – 18) and six main chapters, of which the final one is the conclusion. The first chapter, “Against the Grain” (pp. 19 – 37), discusses the view of modern historians on Greek literature, the “grain”. Historians sometimes complain about Greek writers’ transmission of distorted information pertaining to the Persian Empire, and their ignorance of what modern historians are really interested in. Yet Harrison considers these statements of criticism as unreasonable; according to him, some Greek writers must have had better knowledge of the Persian Empire than modern historians give them credit for, and we would be well served by a closer reading of their sources. In front of the “grain” in the barren field of information, not to “harvest” that which does exist would be unprofitable for the further understanding of Persian history, he contends.

Due to the scarcity of sources left for us, modern Persian historians have to fill in gaps by their acts of imagination. This means that a number of negative judgements of the Persian Empire can be easily converted into positive ones, not necessarily by the introduction of new evidence but by the “slightestrhetorical redirection”. For instance, Xerxes’ withdrawal from Greece after the sea battle of Salamis used to be characterized as a reckless “flight” before, but nowadays, some scholars describe it as a“strategic decision” from the perspective of the Persian Empire. The second chapter, “The Persian Version” (pp. 38 – 56), points out that this shifting of scholarly viewpoints and judgements shows the new emergence of “Iranocentrism”, which takes the place of the “Hellenocentrism” that came before it.

“Family Fortune”, the third chapter (pp. 57 – 72), is focused on the behaviours of kings and queens in Greek literature. Greek writers, like all other writers, have a strong interest in those things which seem strange and therefore curious to them. They recorded events which may at first sight appear to be cruel executions and absurd activities on the part of kings, as well as apparent political interference and intrigues orchestrated by queens at the court, with the support of eunuchs. Modern Persian historians, who are usually sceptical of these kinds of Greek accounts, try to distill and rationalize them in a Near Eastern context, or go even further by dismissing them as fiction altogether. Harrison, in contrast, reminds us that Greek writers did not invent their accounts in the absence of any foundation; we need to distance ourselves from any extreme vision, by looking at Greek sources through a “dispassionate lens”. The discussion of this chapter is based on the author’s belief in Greek writers and their superior knowledge, which is a main subject of this essay.

Previous scholars sometimes dealt with the Persian Kings as Oriental despots, but this image has now been altered into one of a tolerant and benign ruler; Cambyses and Xerxes in particular experienced a significant change in scholarly assessment. As Harrison mentioned already in the second chapter, the image of the Persian Empire is infected and coloured by what modern scholars want it to portray. In the fourth chapter, “Live and Let Live” (pp. 73 – 90), he points to the multiple aspects of the Persian Kings – they sometimes rule their subjects fiercely, and at other times treat them gen-erously; which aspect takes precedence is contingent on the viewpoints of modern historians.

The fifth chapter, “Terra Incognita ” (pp. 91 – 108), which stands slightly apart from the preceding chapters, explores the reports and writings of nineteenth-century British travellers and historians.The scholars of the Achaemenid History Workshops severely criticized their intellectual predecessors, and thus emphasized their originality in the field. Directly contradicting this notion, Harrison successfully found forerunners of the Achaemenid History Workshops in descriptions more than a century old. Some of the writers in this period already held views from the perspectiveof the Persian Empire and identified with them, although they could not be completely free from their British imperial context. In Harrison’s opinion, the approach of the Achaemenid History Workshops was not as novel as they claimed.

In the final chapter, “Concluding Hostilities” (pp. 109 – 27), Harrison reviews the discussion so far, and comments on the influence of Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) on the study of Persian history. Said attributed the first example of Orientalism to Aeschylus’ Persae, which preceded Herodotus’ Histories by some forty years, thus showing that Greek writers were responsible for its inception. Harrison asserts that after Said, Greek sources on Persia were mechanically characterized as biased, and as a result, students of Persian history were required to avoid excavating this rich mine of information. Here, Harrison repeats the topic of his book that Greek writers understood Persia more properly than modern scholars presume, and therefore we should pursue a more detailed investigation of Greek accounts and a more sympathetic engagement with them in their original contexts.

This book can be said, in a word, to propose a “post-post-colonial” theory for the study of Persian history. This refers to how we can break away from the dominant pejorative view on Greek sources, not “from the dominant Hellenocentric view”.3 The next step to take is of course how each of us can draw a new picture of Persian history, by exploiting Greek sources in all respects as Harrison suggests.

Lastly, I would like to make a small addition by stating that, although Said’s Orientalism had a great influence on the distrust of Greek sources and restraint from using them, their limitations were already recognized before Said. For instance, Chester Starr states in his article in Iranica Antiqua, published two years before Orientalism , “In ancient history we are accustomed to look at events from thevantage point of Rome or Athens . . . Our histories are so deeply impressed by a Hellenic stamp that even careful scholars are not aware of the distortions which they introduce.”4 In her Dutch article in1979, Sancisi-Weerdenburg also questioned whether it was possible to reconstruct Persian history from Greek sources, without referring to Orientalism (I suspect that she had not yet been introduced to it).5 The new approach to Persian history was never derived from outside the discipline, but emerged spontaneously from within. This might have been the result of the intensive investigation and exploitation of Greek sources at that moment in time, which is what Harrison suggests is something we should now continue with.

1 Arnaldo Momigliano, “Persian Historiography, Greek Historiography and Jewish Historiography,” in ArnaldoMomigliano, The Classical Foundations of Modern Historiography , Sather Classical Lectures Vol. 45, pp. 5 – 28 (at5 – 6). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

2 Especially, Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, “The Fifth Oriental Monarch and Hellenocentrism: Cyropaedia VIIIviii and Its Influence,” in Achaemenid History Vol. 2, pp. 117 – 31, at 131 (Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor hetNabije Oosten, 1987).

3 Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, “Introduction,” in Achaemenid History Vol. 1, pp. xi – xiv, at xiii (Leiden:Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 1987).

4 Chester G. Starr. “Greeks and Persians in the Fourth Century B.C.: A Study in Cultural Contacts before Alexander: Part 1.” Iranica Antiqua 11 (1976), pp. 39 – 99 (at 41).

5 Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg. “Meden en Perzen: op het breukvlak tussen Archeologie en Geschiedenis.” Lampas 12 (1979), pp. 208 – 222.

Source: https://www.academia.edu/29513969/Thomas_Harrison_Writing_Ancient_Persia

Takuji Abe is Associate Professor, Department of Historical Studies, Faculty of Letters, Kyoto Prefectural University

#persian empire#achaemenids#ancient greek classics#herodotus#thomas harrison#new achaemenid historians#takuji abe

0 notes

Text

Herodotus and the Persian Empire

“The latest issue of Phoenix, the journal of the society Ex Oriente Lux, has been just published. Here is R.J. (Bert) van der Spek‘s summary of this special issue, ‘Herodotus en het Perzische Rijk’, Phoenix 63.2 (2017):

Focus is on Near Eastern information that puts Herodotus in a more balanced perspective. Wouter Henkelman presents Egyptological (and other) information on the famous story of Cambyses and the Apis (III 27-9; 33; 64). He shows how early researchers of the Apis burials were deceived by taking Herodotus’ story at face value. It is better not to, rather to consider Herodotus’ agenda of defamation of Cambyses, which Henkelman defines as ‘character assassination’. He places the story in an Egyptian tradition of defamation of foreigners, of ‘Chaosbeschreibung’. Olaf Kaper discusses the excavations in the Dakhlah oasis, which was once a settlement of revolting king Petubastis IV. The mysterious story of an army sent by Cambyses to the Ammonians, that disappeared in the desert (III 25), might well simply reflect an annihilation by that army by Petubastis, followed by a damnatio memoriae by the Persians. CAROLINE WAERZEGGERS discusses the modern prejudices on Xerxes, exemplified by the film ‘300’. Western knowledge and interpretation of Xerxes is based on Herodotus, who has a very biased picture of Xerxes. Herodotus suggests to have visited Babylon, but who is not very reliable. He does not know anything about an important revolt in the second year of Xerxes’ reign, i.e. about the year of birth of Herodotus. Karel van der Toorn discusses ‘the long arm of Artaxerxes II’ by recognizing the Jewish community in Elephantine in Egypt, which caused tensions. In the fifth century, the time of Herodotus, this setting apart of the Jewish community was not yet so much clear, so that for Herodotus the Jews (in Elephantine and in Palestine” simply counted as “Syrians” (all spoke Aramaic).”

Source: https://www.biblioiranica.info/herodotus-and-the-persian-empire/

Some comments on this summary of the issue of Phoenix having as subject Herodotus and the Persian Empire:

1/ Herodotus’ information about Cambyses killing the Apis bull is very probably not true, but Herodotus did not have some particular agenda against Cambyses. I think that we should accept that Herodotus (who visited Egypt about 80 years after Cambyses’death) has recorded unfavorable Egyptian views on the Persian king who conquered Egypt, moreover views which must be placed, as the summary says, “in an Egyptian tradition of defamation of foreigners, of ‘Chaosbeschreibung”.

2/ I find interesting the proposed version of events that the disappearance of a Perian army in the desert reported by Herodotus was not the result of the a sand storm, but of an attack of the forces of an Egyptian leader resisting the Persians, followed by a damnatio memoriae by the latter.

3/ We should not confuse Herodotus and “300″ , because this movie has its own logic and agendas and takes considerable liberties from Herodotus’ text and more generally the historical reality.

Now, the truth is that Herodotus and the Greeks were totally justified to have negative views on Xerxes, who tried to subjugate Greece and destroyed important Greek shrines and monuments. However, Herodotus manages to treat Xerxes and more generally the Persians with a degree of objectivity which must be seen as admirable in the context of his era. As one of the founders of the “New Achaemenid historiography”, the late Dutch scholar Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, had put it:

Herodotus, on whose information we are mostly dependent for Xerxes’ reign, was hardly a contemporary of the Great King. He collected his information in the period after the Persian wars and probably after the death of Xerxes as well. It should be stressed that there is every reason to agree with Momiliagno’s judgment… of Herodotus as a historian with far more “intellectual generosity” than any of his fellow-Greeks. Complete impartiality is beyond any historian, but Herodotus at least made a very serious attempt to give the Persians a fair deal. He was, however, a historian and had to tell his story: he collected, organised and arranged his material. If one realises the conditions under which he accomplished this task, one cannot but admire the impressive results.

(in Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg “The Personality of Xerxes, King of Kings”, Brill Companion to Herodotus)

This does not mean of course that Herodotus’ Xerxes is the “definitive” Xerxes or that we should see him exclusively through the eyes of the Greeks. As Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg continues:

This is not the right place to discuss the elements of Xerxes’ characterisation in Herodotus’ text. Very often the emphasis has been put on the Persian king’s hybristic behaviour. There are, however, several factors in his portraiture by Herodotus which add up to a tragic Xerxes, a man unable to escape fate. A further analysis of the text and a close scrutiny of the relevant passages may result in a better understanding of Herodotus’ insight into the interralation between the destined course of events and human interference in history. Here it is only necessary to note that the Xerxes of the Histories is as much a product of Herodotus’ sources as of the author’s construction of his narrative. If we are discussing the psychology of Xerxes in Herodotus’ account, we are in fact dealing with Herodotus’ historical understanding and with his techniques for writing up the results of his investigations. There are at least several layers between the personality of Xerxes, as king of Persia and commander of his armies during the Greek expedition. The uppermost of these layers is Herodotus’ careful and convincing representation, which makes us feel as if we are encountering a real life personality. But we should be warned that what we read is “neither fact nor fiction but “transfigured tradition”’

However, the truth is that we don’t find either the “true” Xerxes in the surviving (very fragmentary) Persian record, which is an expression of the Achaemenid royal ideology, not an objective record of facts or an objective characterization of the leading figures in the Persian history.

To conclude, a better understanding of the historical Xerxes passes necessarily from the combination and combined interpretation of all available sources, Greek, Persian, and Babylonian, and Herodotus remains a main source on this subject.

4/ Herodotus does not claim unambiguously that he has visited Babylon and personally I believe that, given the political and other circumstances of his era, a journey by him to Babylon was rather improbable (Babylon was too deep in the Persian Empire and there was not there in Herodotus’ time a Greek community of some importance on which he could rely for hospitality and support). If he did travel to Babylon despite these obstacles, he must have stayed there for a short period of time and serious contacts with Babylonian intellectual milieus must be excluded. I believe that most probably Herodotus’ sources on Babylon must have been Greeks having worked for the Persians and/or Persians or Medes in contact with the Greeks.

Btw there is a typo in the summary: the Artaxerxes Macrocheir/ Longemanus (”the one with a long arm”, because one of his arms was longer than the other) who recognized the Jewish community in Elephantine and to whom the article of Karel van der Toom refers was Artaxerxes I, not Artaxerxes II.

0 notes

Text

Herodotus, the Persian Empire, and Imperialism

“Herodotus is not commonly relied upon as a source for Persian imperialism, or for Persian ideology more broadly. In the distinction of Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg, one of the leading figures in the revival, or indeed creation, of Achaemenid studies, “the inscriptions provide information on the royal ideology, the Histories give insight into the Greek vision of an eastern monarch‟.2 Any reconstruction of Persian political thought, or of Persian foreign policy, should be reconstructed from limited Persian material rather than through reliance on Greek sources.3 Greek historians and historiographers have, for the most part, concurred.”One of the most obvious characteristics‟, according to Oswyn Murray, of Herodotus‟ accounts of eastern societies is that they show no signs of influence from the known literary or historical genres preserved in writing, such as royal inscriptions‟.4

Of course, the picture is, in practice, more shaded. Certain passages of the Histories, notably the accounts of Darius’ accession, the description of the royal road to Susa, or the catalogue of Xerxes’ army, have been extensively discussed for their relationship to (extant or putative) Persian sources.5 At the same time, there has been an increasing trend in scholarship, on Herodotus and on other Greek accounts, towards identifying reflections of non-Greek ideology, restoring the agency of non-Greek peoples and envisaging such texts as defying ethnic classification (as Greek or Persian, say) just as artefacts may.6 Achaemenid historians also inevitably employ Greek sources to fill out the canvas of Persian history. But the use of Greek sources for Persian history is a notably guarded exercise, which condemns Greek historians to providing a limited kind of circumstantial evidence. In the oft-repeated phrase of Pierre Briant, “in reading the classical authors, we must distinguish the Greek interpretative coating from the Achaemenid nugget of information.‟7 Once the historian has peeled back the shell from the kernel (or cleansed or decoded the Greek logos in other analogies of Briant‟s)8 the anecdotes of Greek sources can be deployed to create a kind of collage of court protocol: of the limitations faced by noblemen in accessing the Great King or the constraints operating on the King‟s wives in punishing their rivals. Greek sources can also reinforce our picture of some aspects of Persian ideology, in relation, for example, to the culture of gift-giving within the Persian court.9 WhereGreek writers may shed light on Persia, in short, it is frequently seen as inadvertent, or in spite of their own agendas in writing: a matter of authentic Persian material somehow attaching to a hostile organism rather than of a writer‟s acuity or interest.10

How we have found ourselves in this scholarly landscape, the complex causes and character of the recent Achaemenid historiography, are topics for another place.11 This paper has a more restricted compass: to argue that Herodotus Histories reveal a closer engagement with Persian royal ideology (as reflected in the royal inscriptions) than has been recognised.12 It will focus on one central passage and one central theme: the so-called Council Scene (at the beginning of Book 7) in which Xerxes and his court debate the wisdom of the expedition against Greece; and the motives ascribed to the Persians for the invasion of Greece.

Certain points should be made clear at the outset. The debate is amongst the most elaborate set-piece passages of the Histories, in which the positions of the three leading Persians (Xerxes, his general Mardonius and the King‟s uncle Artabanus) are subtly differentiated and placed in dialogue with one another, as well as with numerous earlier passages of the Histories. The scene, wrote Immerwahr in his Form and Thought, “gives a complete description of the causes of the Persian Wars, and from this point of view it is a summary of the whole work‟.13 In seeking to locate the various strands of the debate in an authentic Persian ideological context we cannot ignore the manifold ways in which the detailed elements of that originating context have been redeployed to create a reflection, not only on Persian imperialism, but on imperialism itself.14 No matter then the extent of the influence of Persian material, Herodotus will also have been influenced by other factors is in his characterisation of (Persian) imperialism: the model of Athenian power in his own day, contemporary democratic ideology or by sophistic thought.15″

“In conclusion it is worth reiterating both what claims are, and are not, being made. It is important, first, to emphasise the element of art in Herodotus‟ development of the themes drawn from Persian royal ideology. When we recount Greek representations of Persian monarchs (or of other aspects of the non-Greek world), we are keen as scholars to insist that we are dealing with a Greek view, and – when dealing with the works of authors such as Herodotus and Xenophon, not any Greek view, but the “highly nuanced and idiosyncratic view of a particular Greek author‟.134 This firm distancing of representation and reality is, of course, for a number of reasons: to avoid seeming either to reduce an author to being a mere cipher for his sources, or to commit the naïve blunder of supposing that Greek sources provide a clear window on the world of the Persian court. And yet, though representation and reality may be distinct, they are necessarily related. How likely is it that a work such as Herodotus” Histories might be the vehicle for so many detailed traditions of Persian history (no matter how distorted) and yet bear no imprint of royal ideology? In the fine phrase of Jonas Grethlein, historians such as Herodotus “had to assert themselves in the vast field of memory‟, a field which inevitably included the native traditions of those people he represents.135 An appreciation of the complex ways in which the historian draws on Persian material actually brings out his historical art into yet more powerful relief.

Finally, it is worth reiterating that the thesis that the Persian Council Scene, and the Histories more broadly, reveal a widespread appreciation of the themes of Persian royal inscriptions is not predicated on any particular model by which Herodotus accessed such knowledge. The presence of Greeks in the service of the Persian King at Persepolis opens up at least a hypothetical route by which a detailed knowledge of the Persian court environment might have reached Herodotus’ orbit.136 No matter, however, the precise mechanism by which such material reached Herodotus’ pages, it is clear both that the quantity of the material on Persia contained in the Histories betokens an intense broader interest in the Persian court environment,137 and that any such material will have gone through an extensive cultural and literary filter before the monolingual138 historian recorded it in his Histories.

The more indirect Herodotus access to the evidence of royal ideology that permeated from the Persian court, the more strongly another conclusion emerges. A central theme in recent Achaemenid historiography has been to identify evidence of the impact of Persian imperialism, not least in the material culture of Persia’s subject peoples.139 Though Herodotus’ perspective on Persian imperial ideology is hardly one of joyous assent to Persian power, his detailed knowledge is at least very good evidence of its reach.140″

The opening paragraphs and the conclusion of Thomas Harrison’s Herodotus on the character of Persian imperialism, in A. Fitzpatrick-McKinley (ed.) Assessing Biblical and Classical Sources for the Reconstruction of Persian Influence, History and Culture (Harrassowitz, 2014)

https://www.academia.edu/9633063/Herodotus_on_the_character_of_Persian_imperialism_in_A_Fitzpatrick_McKinley_ed_Assessing_Biblical_and_Classical_Sources_for_the_Reconstruction_of_Persian_Influence_History_and_Culture_Harrassowitz_2014_

0 notes

Text

Herodotus and the World

“The ancient historian Herodotus, the Father of History, is also considered a great anthropologist. In his account of the Persian invasions of Greece in the fifth century BCE, he searches for the forces that transformed Persians from an underprivileged nation into the rulers of the largest empire of antiquity. In his Histories , he explores the non-Hellenic peoples that were either conquered by the Persians or managed to resist or elude their aggression, such as the Lydians, Egyptians, Libyans, Scythians, and Thracians, and describes the lands they inhabit, their resources, customs, religious rituals, and cultural predisposition.”

Munson, Rosaria Vignolo, ed. Herodotus: Volume 2 Herodotus and the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Table of Contents

Introduction Rosaria V. Munson Physis and Historie 1. The Boundaries of Earth, James S. Romm 2. Herodotus and Analogy, Aldo Corcella 3. Herodotus and Historia, Catherine Darbo-Peschanski The Homeric wanderer 4. Odysseus and the Historians, John Marincola Women in Herodotus 5. Exit Atossa: Images of Women in Greek Historiography about Persia, Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Addendun by Amelie Kuhrt 6. Women and Culture in Herodotus Histories, Carolyn Dewald World religions and the divine 7. Herodotus and Religion, John Gould 8. Herodotus on the Names of Gods: Polytheism as a Historical Problem, Walter Burkert Herodotus barbaroi 9. Women's Customs among the Savages in Herodotus, Michele Rosellini and Suzanne Said 10. Imaginary Scythians: Space and Nomadism, Franccois Hartog 11. Herodotus the Tourist, James Redfield 12. Herodotus and an Egyptian Mirage, Ian S. Moyer 13. Who Are Herodotus' Persians?, Rosaria V. Munson Us and them 14. Ethnicity, Genealogy, and Hellenism in Herodotus, Rosalind Thomas 15. East is East and West is West - Or Are They? National Stereotypes in Herodotus, Christopher Pelling

Source: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/herodotus-volume-2-9780199587599?cc=us&lang=en&

0 notes

Text

Herodotus on Xerxes (II)

“This is not the right place to discuss the elements of Xerxes’ characterisation in Herodotus’ text. Very often the emphasis has been put on the Persian king’s hybristic behaviour. There are, however, several factors in his portraiture by Herodotus which add up to a tragic Xerxes, a man unable to escape fate. A further analysis of the text and a close scrutiny of the relevant passages may result in a better understanding of Herodotus’ insight into the interralation between the destined course of events and human interference in history. Here it is only necessary to note that the Xerxes of the Histories is as much a product of Herodotus’ sources as of the author’s construction of his narrative. If we are discussing the psychology of Xerxes in Herodotus’ account, we are in fact dealing with Herodotus’ historical understanding and with his techniques for writing up the results of his investigations. There are at least several layers between the personality of Xerxes, as king of Persia and commander of his armies during the Greek expedition. The uppermost of these layers is Herodotus’ careful and convincing representation, which makes us feel as if we are encountering a real life personality. But we should be warned that what we read is “neither fact nor fiction but “transfigured tradition”’ (Lateiner 1987; 103) [Note of the author: Lateiner adds that “interpretation and reconstruction structure the amorphous data of every historical investigation”(Ibid.)].”

Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg “The Personality of Xerxes, King of Kings”, in Brill’s Companion to Herodotus, pp 578-590 [588]

0 notes

Text

Herodotus on Xerxes (I)

“Herodotus, on whose information we are mostly dependent for Xerxes’ reign, was hardly a contemporary of the Great King. He collected his information in the period after the Persian wars and probably after the death of Xerxes as well. It should be stressed that there is every reason to agree with Momiliagno’s judgment... of Herodotus as a historian with far more “intellectual generosity” than any of his fellow-Greeks. Complete impartiality is beyond any historian, but Herodotus at least made a very serious attempt to give the Persians a fair deal. He was, however, a historian and had to tell his story: he collected, organised and arranged his material. If one realises the conditions under which he accomplished this task, one cannot but admire the impressive results.”

Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg “The Personality of Xerxes, King of Kings”, in Brill’s Companion to Herodotus, pp 578-590 [583]

Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg (1944-2000) was a distinguished Dutch historian specialized in classical Greek and Achaemenid Persian history.

0 notes