#I have a few other feminist theory books to read

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

2023 Pinterest 50 Book Reading Challenge

21. A Book that Scares You

Second Sex by Simone De Beauvior

It's around 700 pages of theory translated from another language. I have read longer books, read theory before, and read translations before (I enjoy doing so) but the combination of the length, subject and the fact it's translated might make this hard for me to get through.

#it doesn't exactly scare me- more like it is very long (700 pages) and translated as well as being theory reading too#I feel like as a feminist there are a list of books I still have to read and form opinions on- this being one of them#I have a few other feminist theory books to read#also pretty sure she's controversial though I might be confusing her for someone else...???#simone de beauvoir#second sex#feminist theory#french literature#translated books#It's a combination of things that might be difficult on their own so that's why the text is a little intimidating#I feel like I should have read it already too :/#books#bookblr#20th century literature#I feel like a bad feminist not having opinions on these pretty well known texts#bell hooks is probably my favorite feminist that I've read so far#I like the Brontes and Virginia Woolf too of course#reading challenge#tbr#2023 tbr#we'll see when I get to this

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

the latter person also wrote a huge thinkpiece article about how "transemasculation" is better theory than transandrophobia because they think that addressing that society largely does not treat trans men as men is trans men doing a disservice to themselves by "misgendering themselves" and also that transmasc theory needs to address that trans men are privileged over cis women (???) and all transmasc oppression is rooted in the exact same type of misogyny as calling a cis man a homophobic slur for painting his nails and it was. distressingly stupid

And that, anon, is why I dislike her! I had no idea she ever talked about Hinduism at all so her acting like a trans woman talking about a trans(radical)feminist book and tagging the author's name was Operation Freakout was so out of left field. Like, settle down Paulette, just because you gave trans radical feminism a name doesn't mean I hate you nearly as much as apricot-aligator.*

Such an amazing case of projection. I truly can't emphasize how unhinged it is that she had that screenshot of me mentioning Ekadashi months ago. I never talk about Hinduism on here except that and I think one other time, plus a few anons responding to those. It was untagged, too! She had to have seen it at the time and been seething about it ever since. Her complex with the religion she was raised with is depressing but not my problem and if she tries to make it my problem I'm just going to laugh at her.

*although I do also just think it's fun to keep saying "apricot-aligator" **

**btw apricot if you read this and you wanna get on my case about me being obsessed with you feel free to let me know when you've gone a day without bitching about the evils of trans men

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

dick mullen, hard-boiled detectives, and cultural occupation

hi all. im back with more disco elysium meta. knowing me, this'll be long, so bear with me--

i'm really interested in thinking about the dick mullen series's role in revacholian culture, particularly by reflecting and creating a patriarchal and destructive police culture. taking it one step farther, i'm interested in their potential role in vesper's occupation

before we begin, i want to clarify that i'm taking the approach that art and culture influence each other constantly (art isn't just reflecting culture/history, it's also creating it). it's an idea that comes out of the school of new historicism if you want to look more into it! anyway, my argument is guided by the assumption that the world of disco elysium operates this way

with that out of the way, let's talk detectives! I want to zero in on this passage:

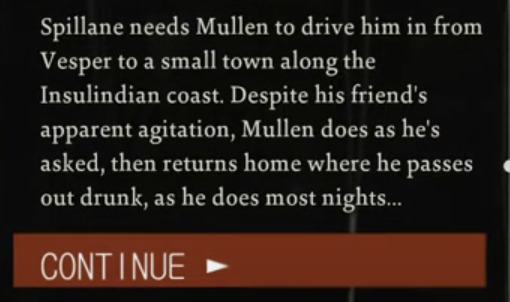

[Image ID: White text on a black background from the game Disco Elysium reading "Spillane needs Mullen to drive him in from Vesper to a small town along the Insulindian coast. Despite his friend's apparent agitation, Mullen does as he's asked, then returns home where he passes out drunk, as he does most nights..." Below the text is a red bar with the word "continue" on it, and an arrow pointing right. End image ID]

Right off the bat, there are two really interesting explicit references: Philip Marlowe and Mike Hammer.

First, the opening of this novel is borrowed from Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye, where detective Philip Marlowe's old friend (/homoerotic, depending on whose work you read) shows up out of the blue and asks to be covertly taken across the border from Los Angeles to Tijuana. The next day, the friend's wife is found dead, and Marlowe is arrested as an accesory to murder. He spends the rest of the book proving his (and his friend's) innocence. You're probably seeing a few parallels to Mullen already.

A few other things to know about Marlowe and the series he stars in--some of these might ring a bell:

Marlowe is depressed, at-times suicidal, and a likely alcoholic, though the books are deeply concerned with normative masculinity and try to minimize these

Adapted into a 1973 movie where Marlowe is recast as a "man out of time," (AKA sopping wet disco detective) awkwardly split between the 50s and the 70s

Generally tout conservative USAmerican values circa ~1940-1955, especially pushing white, cishet male individualism, fear of marginalized identity, and promoting the idea that government punishment and surveillance are the best, most desirable solutions to social issues

You're probably already seeing some interesting parallels (or places Disco Elysium adapts/interrogates some of these ideas). Hang onto the conservatism and government stuff--we'll get back into it.

(Quick caveat that basically ALL detective fiction pushes the bolded ideas above to some extent or another, but that Chandler's stuff gets especially highlighted in literature because he wrote a very famous essay about American detective fiction and the essay and his body of work were very popular and influential)

The next reference is a general one to Mickey Spillane, author of the Mike Hammer series. This is a pretty interesting pull, because

they're a bit niche!

2. they have some of the most explicitly sexualized violence against women in the entire hard-boiled detective genre (Mitzi Brunsdale has some great work on this). a few scholars i've read discuss them as outliers, but most consider them "the quiet part out loud" of a genre largely about controlling and punishing women

(if you're curious, this is a really interesting reading of some of them guided by queer/feminist theory and a focus on the post-WWII era).

I'll admit Hammer's a little bit more outside of my research niche than Marlowe, but I've read enough to know he's also very much in the "individualist straight white guy who represents the government has to fix uppity women" school of fifties detective fiction

Both of these references affirm and contextualize what we can tell about Dick Mullen from reading the book: he's the white macho-individualist picture of repressed trauma and masculine anxiety, while also constituting the popular fictional idea of policing

keeping that in mind, i want to return to the beginning of The Long Goodbye/Dick Mullen and the Case of the Stolen Identity, where Mexico and Insulinde both occupy an imperialist fantasy role as "lawless" places Americans/Vespertines can flee in order to avoid consequence for their actions. It's not a one-to-one cultural comparison (very little in this world is), but it gives us a little context for why it's weird and interesting to me that the Mullen books are so popular in Revachol

considering all of this, i think it's interesting to consider that the police culture of the RCM (intensely sexist, homophobic, racist/xenophobic, and generally supportive of an occupying government) might have been partially created, or at least reinforced through the popular notions of fictional policing produced and popularized within an occupying nation. given the RCM's roots as the ICM, i think there might have been a potential incentive to mass publish and produce these books in an occupied, formerly-communist region to normalize and entrench ideas of individualism, patriarchy, and government surveillance, especially among the only revacholians with any government power or representation

that being said, I think it's a little limiting to act like people will not naturally turn against a failed rebellion, especially given the ensuing mass destruction. despite being an ostensibly individualist and capitalist genre, hard-boiled detective fiction was born and popularized out of the Great Depression. its work to romanticize a return sociopolitical "normalcy" and to speak to the experience of the working class are what kept it popular in moments of social and economic upheaval in the US, even if, ultimately, it puts the pill of pro-capitalist/individualist sentiment in the cheese of working class appeal and bitter suspicion towards government bigwigs. granted, interpellation by the art of one's own culture has a different connotation from interpellation into the desired culture of an occupier, though i think it's important not to romanticize revachol as a place with 0 conservative sentiment before its occupation by the moralintern

i think there are a few possible and interesting arguments here--that there was an incentive for vespertine governments and businesses to promote vespertine individualism to help quell rebel sentiment within the RCM and revachol in general, that people naturally turned to the comfort and "normalcy" of conservative fictions in periods of turmoil despite their ideas being actively harmful (in neo-marxist theory, this is called interpellation, which, for the record, is all over the game), maybe some of column A, some of column B

regardless, i think it's interesting to view the dick mullen books as something which have created culture, rather than just reflecting it. it's definitely a lens that helps to explain part of the radical cultural shift between the idealized heyday of the ICM and the RCM (though i think the cracks in that shift are equally interesting and worth exploring another time)

(if you can't access any of the articles, please shoot me a dm! i'm happy to share wherever i can. i believe i have some pdf scans of pages from the linked books, but those are unfortunately limited)

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

People say Eloise is a self centered white feminist who enjoys the privileges that come with being a Bridgerton and although that's true, she is also a sheltered teenage girl who needs to learn about the world.

Her feelings of marriage are valid and while she needs to learn that desiring motherhood and marriage doesn't make a woman lesser, it's part of growing up and learning true feminism. She's a baby feminist but viewers don't want her to grow. How many teenage girls in today's day and age are all-knowing about feminism theory? Her friendship with Theo taught her about the working class and that connection to the outside world could have been a great learning experience for Eloise. Yes she has the privilege of being a Bridgerton but that safety net is exactly why she should be allowed to advocate for things the way she wanted Whistledown to(not a critique of the character but rather the writing and the fandom)

Penelope did some selfish things as Whistledown, abusing her power (cause it wasn't just about being gossip girl for the bag) and rather than acknowledge that we're expected to sweep it under the rug. I LOVE flawed characters because the writing acknowledges their wrong doings and yet certain characters get away with murder.

Eg s1 Blair was awful to Serena and while she had her reasons for doing so, revenge and her own self worth and abandonment issues, the show acknowledged this and we wanted good things for Blair. Serena slept with her best friend's boyfriend and covered up a mans overdose but we still root for her because she is a good person and is trying to grow.

If Penelope doesn't acknowledge her wrongdoings how can she grow as a character.

"Okay publishing a burn book is wrong but I love writing and I'm good at it, maybe I should become Jane Austin or something."

(throwing in how Edwina was raked over the coals for being angry with Kate and while the half sister comment was uncalled for, she wasnt given the same grace Penelope has been given)

I'm sorry for how long and all over the place this is.

No, I get it. The issue is that some characters are given grace while others are crucified. Some characters have their circumstances considered when examining their behavior while others don't. I hate it that some characters get novellas dedicated to defending their bad behavior while others should've just known better.

And that's totally the way I see Eloise Bridgerton. She's a baby feminist! She is in her just watched Ironed Jawed Angels and has maybe read a few zines era of feminism. When I was 17, I remember saying in class that I didn't think it was possible to be a SAHM and be happy and now my opinions have radically shifted because I'm not a kid anymore. Now, if you'd ask me I'd say it's a vulnerable position to be in economically because your security is tied up in your marriage working out and or your husband never dying, but it's your choice ultimately. What a difference a fully developed brain and college professors who require you to read bell hooks and Audre Lorde can make.

But seriously, the sad irony of Eloise being raked over the coals for "doing nothing" is that she was trying to become more informed and it blew up in her face. Spending time with Theo and other members of the working class was really good for her. Sadly, Penelope should've known better than most that she was genuinely trying to expand her worldview, but Eloise is the only person getting the bad friend allegations.

And yeah, as much as I love Kate and Anthony, people were way too hard on Edwina in season two. No one wanted to hurt her, but who in her position would toss confetti?

Plus, I'm really glad someone else is seeing the endless Gossip Girl comparisons that can be made here!

P.S. If you're interested one of my favorite Kanthony fics ends in Anthony and Kate encouraging Eloise to become a fiction/social commentary writer.

#asked and answered#eloise bridgerton#anti penelope featherington#theo sharpe#edwina sharma#bridgerton

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

can you tell me what your thesis is about if you're willing to share??

Hi!!! Yes, of course! I need to go over and over the description of this thing in order to turn in a precise and compelling project for the board (attempt #3 at finishing this cursed degree, here we go! *sobs*).

My area of interest has always been Medieval Philosophy, Metaphysics, Ethics, Virtue Ethics and Aristotelian Ethics-Politics. My very first attempt was writing something on Metaphysics (transcendentals) then Ethics Metaphysics (the role of intellectual intuition in moral reasoning in Aristotelian Ethics, Book VI of the Nicomachean Ethics)... Neither worked mainly because a problem when talking metaphysics is... well, there's few words to use and little to say and I have always been a very succinct academic writer (yeah, I know, but it is true).

When I reached acceptance about that XD I moved on to trying something about Aristotelian Ethics-politics. Alasdair MacIntyre is a key author in that area, and he's a favorite of mine because in agreement or disagreement he's thought provoking, he has a sense of humor, and he's a hater of the fun kind. I know it isn't proper to call or pick academic authors because they are fun, but hey, he is. He is a curmudgeonly old man (present tense: he's 95), who kind of manages to disagree with everyone because he hates being put in boxes, but he's also always been very willing and open to listen to other voices and change his opinions on things.

For example, the refinement and reformulation of many ideas between his After Virtue (1981) and his Dependent Rational Animals (1999) came (declaredly) through a reading of certain feminist theory, which brought to the foreground to him how little academic Ethics had focused until that point on disability and caretaking.

He's also always been a versatile author in the sense of breaching the barriers between disciplines for the purposes of philosophical inquiry -After Virtue has a great deal to say about Sociology, and Dependent Rational Animals talks a lot about dolphins XD.

I decided I wanted to write something about this guy, but I got stuck because if you are writing on an author specifically, alone, how do you manage to write something that isn't like, textbook regurgitation? Theoretically I know it is possible, but it was very paralyzing to me all the same.

Enter Elizabeth Gaskell with a steel chair.

I love Gaskell dearly for many different reasons. I love the way in which she writes nuanced, believable, textured characters. I love the treatment of grief in her work, I love the compassion she has for her characters, I love how she makes interesting, central, and natural relationships between parents and children. I love that she's versatile too, and that she saw writing as a vocation, and how she manages to talk about so many different things in a novel without making it come across as didactic or preachy. But one very special thing that has called my attention is her specific interest in communities, and community building through friendship.

Very often her "proposals" of "solutions" to social problems, specifically in her industrial novels, have been dismissed as the utopian sugary pap of learning to share and be nice of someone completely out of touch with reality, but I think those readings are fundamentally missing the framework that makes her ideas make sense and be solid.

As an aside, I feel like that ungenerous reading is kinda rich when Hard Times and its "imagination to power!" concept or Shirley and its marriage solution keep getting praise to this day. You know. It comes across as a bit double standard-y, if you ask me.

But back to topic, guess who did consider friendship, understood as the ties that unite virtuous people in the pursuit of the good for themselves and their fellow men, the very foundation of society, and mankind as essentially social, and therefore for ethics and politics to be a continuum? That's right, my boy Aristotle!

And to that, between other things, when talking about the Aristotelian tradition of Ethics Politics, MacIntyre adds teleological narrative as the element that frames and anchors virtue ethics in this scheme. What is more, he dedicates A CHUNK of chapter 16 of After Virtue to Jane Austen, and why he thinks she's "the last key representative" of this tradition (which has sprung a non negligible amount of scholarship on Austen and virtue ethics).

And I'm persuaded that Gaskell is a significant successor to Austen in this way too, and that the certain sympathy people often perceive between them comes from this aspect (because, in all honestly, it's clearly not about tone or style).

So that's the aim/core of my thesis: to present/analyze/contextualize Gaskell's work within the framework of the Aristotelian Ethics-Politics tradition as understood by MacIntyre.

Of course because I am, in Nelly Dean's description of Edgar Linton, a venturesome fool, this is clearly very ambitious, and I am making it worse for myself by doing things like harvesting circa 350 titles for a thesis that won't require more than 50 and that cannot be more than 80 pages long. The clown shoes can be heard from the other side of the world no this has nothing to do with the fact that I don't think I'll ever get a masters or a PhD where I might be able to develop this concept beyond a very summary overview of N&S and maybe Cranford and My Lady Ludlow if I'm lucky.

And that's how I should have sent something to my advisor three weeks ago (I haven't yet) and how I'm half agony half hope about the whole thing, because I'm scared and anxious and full on rowing through Nutella executive function wise. Maybe I should get a rubber duck.

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alright, I just saw the post about the correct way of using "pick me" and how it relates to Abigail and I'm not going to lie. I have a few thoughts I'd like to share. I'll do my best to keep it as respectful as possible and I do genuinely apologize if I sound too harsh.

First of all, I do think that coming with the whole "Actually, you're all misusing the term. I'll tell you how to use it because yes I am a feminist and I read about this" is quite condescending. I completely agree that Abigail is not a pick me, that her hobbies and interests are genuine, but the tone... It did throw me off.

Now out of the books with the theory and into the life with the experience, it is a common thing to find girls and women who are into "masculine" hobbies to gain attention from men. To be "superior to other women" because she's "one of the boys" and will hang out with mostly boys. And will remark that, and will make sure everyone knows she's different and she's cool and guuyss she's NOT like the other girls!!!!!!!!! /lh

To see this in Abigail is not a stretch because we do see these traits in her character, but it's a flawed vision. It's lacking of basic literacy because it's missing a very important part to be a pick me: Wanting to be picked.

She's very self sufficient and independent. I'm on my first run on the game itself and Abigail is one of the hardest characters for me to gain hearts because everything I give her she turns to me and asks what she's supposed to do with it and I'm here staring at my screen in disbelief and wishing I could reach into the screen and ask her what ELSE is she supposed to do with the grapes I gave her??

Sorry sorry I got sidetracked. Well I've seen a few scenes with her but I have never seen her act like she wants the male attention, despite having so many "masculine" hobbies and I have never seen any of the men she hangs out with mention anything for that. She's literally just vibing and we respect that.

I think that's more of a point we could use to argue that Abigail isn't a pick me. Instead of taking out the books and the correct terms, which are not going to be fitting all of the situations since I can name pick mes that aren't aligned with right-wing ideals because this is a much broader issue nowadays, we can take the very, VERY basics of a "pick me" and work with it: Wanting to be picked. Which is completely backwards to Abigail's character.

And as a little last thing, Alex is much more of a pick me than Abigail because bro is constantly whining that there aren't enough girls around. Why are you so concerned huh? Do you want one of them to....... Pick you.......? /j (My bad for the long post by the way)

.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queering kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers" (A)

As I promised before, I will share with you some of the articles contained in the queer-reading study-book "Queering the Grimms". Due to the length of the articles and Tumblr's limitations, I will have to fragment them. Let's begin with an article from the Faux Feminities segment, called Queering Kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers", written by Jeana Jorgensen. (Illustrations provided by me)

The fairy tales in the Kinder- und Hausmärchen, or Children’s and Household Tales, compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are among the world’s most popular, yet they have also provoked discussion and debate regarding their authenticity, violent imagery, and restrictive gender roles. In this chapter I interpret the three versions published by the Grimm brothers of ATU 451, “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” focusing on constructions of family, femininity, and identity. I utilize the folkloristic methodology of allomotific analysis, integrating feminist and queer theories of kinship and gender roles. I follow Pauline Greenhill by taking a queer view of fairy tale texts from the Grimms’ collection, for her use of queer implies both “its older meaning as a type of destabilizing redirection, and its more recent sense as a reference to sexualities beyond the heterosexual.” This is appropriate for her reading of “Fitcher’s Bird” (ATU 311, “Rescue by the Sister”) as a story that “subverts patriarchy, heterosexuality, femininity, and masculinity alike” (2008, 147). I will similarly demonstrate that “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” only superficially conforms to the Grimms’ patriarchal, nationalizing agenda, for the tale rather subversively critiques the nuclear family and heterosexual marriage by revealing ambiguity and ambivalence. The tale also queers biology, illuminating transbiological connections between species and a critique of reproductive futurism. Thus, through the use of fantasy, this tale and fairy tales in general can question the status quo, addressing concepts such as self, other, and home.

The first volume of the first edition of the Grimm brothers’ collection ap[1]peared in 1812, to be followed by six revisions during the brothers’ lifetimes (leading to a total of seven editions of the so-called large edition of their collection, while the so-called small edition was published in ten editions). The Grimm brothers published three versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” in the 1812 edition of their collection, but the tales in that volume underwent some changes over time, as did most of the tales. This was partially in an effort to increase sales, and Wilhelm’s editorial changes in particular “tended to make the tales more proper and prudent for bourgeois audiences” (Zipes 2002b, xxxi). “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is one of the few tale types that the Grimms published multiply, each time giving titular focus to the brothers, as the versions are titled “The Twelve Brothers” (KHM 9), “The Seven Ravens” (KHM 25), and “The Six Swans” (KHM 49). However, both Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther, in their respective 1961 and 2004 revisions of the international tale type index, call the tale type “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” Indeed, Thompson discusses this tale in The Folktale under the category of faithfulness, par[1]ticularly faithful sisters, noting, “In spite of the minor variations . . . the tale-type is well-defined in all its major incidents” (1946, 110). Thompson also describes how the tale is found “in folktale collections from all parts of Europe” and forms the basis of three of the tales in the Grimm brothers’ collection (111).

In his Interpretation of Fairy Tales, Bengt Holbek classifies ATU 451 as a “feminine” tale, since its two main characters who wed at the end of the tale are a low-born young female and a high-born young male (the sister, though originally of noble birth in many versions, is cast out and essentially impoverished by the tale’s circumstances). Holbek notes that the role of a low-born young male in feminine tales is often filled by brothers: “The relationship between sister and brothers is characterized by love and help[1]fulness, even if fear and rivalry may also be an aspect in some tales (in AT 451, the girl is afraid of the twelve ravens; she sews shirts to disenchant them, however, and they save her from being burnt at the stake at the last moment)” (1987, 417). While Holbek conflates tale versions in this description, he is essentially correct about ATU 451; the siblings are devoted to one another, despite fearsome consequences.

The discrepancy between those titles that focus on the brothers and those that focus on the sister deserves further attention. Perhaps the Grimm brothers (and their informants?) were drawn to the more spectacular imagery of enchanted brothers. In Hans Christian Andersen’s well-known version of ATU 451, “The Wild Swans,” he too focuses on the brothers in the title. However, some scholars, including Thompson and myself, are more intrigued by the sister’s actions in the tale. Bethany Joy Bear, for instance, in her analysis of traditional and modern versions of ATU 451, concentrates on the agency of the silent sister-saviors, noting that the three versions in the Grimms’ collection “illustrate various ways of empowering the hero[1]ine. In ‘The Seven Ravens’ she saves her brothers through an active and courageous quest, while in ‘The Twelve Brothers’ and ‘The Six Swans’ her success requires redemptive silence” (2009, 45).

The three tales differ by more than just how the sister saves her brothers, though. In “The Twelve Brothers,” a king and queen with twelve boys are about to have another child; the king swears to kill the boys if the newborn is a girl so that she can inherit the kingdom. The queen warns the boys and they run away, and the girl later seeks them. She inadvertently picks flowers that turn her brothers into ravens, and in order to disenchant them she must remain silent; she may not speak or laugh for seven years. During this time, she marries a king, but his mother slanders her, and when the seven years have elapsed, she is about to be burned at the stake. At that moment, her brothers are disenchanted and returned to human form. They redeem their sister, who lives happily with her husband and her brothers.

In “The Seven Ravens,” a father exclaims that his seven negligent sons should turn into ravens for failing to bring water to baptize their newborn sister. It is unclear whether the sister remains unbaptized, thus contributing to her more liminal status. When the sister grows up, she seeks her brothers, shunning the sun and moon but gaining help from the stars, who give her a bone to unlock the glass mountain where her brothers reside. Because she loses the bone, the girl cuts off her small finger, using it to gain access to the mountain. She disenchants her brothers by simply appearing, and they all return home to live together.

In “The Six Swans,” a king is coerced into marrying a witch’s daughter, who finds where the king has stashed his children to keep them safe. The sorceress enchants the boys, turning them into swans, and the girl seeks them. She must not speak or laugh for six years and she must sew shirts from asters for them. She marries a king, but the king’s mother steals each of the three children born to the couple, smearing the wife’s mouth with blood to implicate her as a cannibal. She finishes sewing the shirts just as she’s about to be burned at the stake; then her brothers are disenchanted and come to live with the royal couple and their returned children. However, the sleeve of one shirt remained unfinished, so the littlest brother is stuck with a wing instead of an arm.

The main episodes of the tale type follow Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp’s structural sequence for fairy-tale plots: the tale begins with a villainy, the banishing and enchantment of the brothers, sometimes resulting from an interdiction that has been violated. The sister must perform a task in addition to going on a quest, and the tale ends with the formation of a new family through marriage. As Alan Dundes observes, “If Propp’s formula is valid, then the major task in fairy tales is to replace one’s original family through marriage” (1993, 124; see also Lüthi 1982). This observation holds true for heteronormative structures (such as the nuclear family), which exist in order to replicate themselves. In many fairy tales, the original nuclear family is discarded due to circumstance or choice. However, the sister in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” has not abandoned or been removed from her old family, unlike Cinderella, who ditches her nasty stepmother and stepsisters, or Rapunzel, who is taken from her birth parents, and so on. Although, admittedly, “The Seven Ravens” does not end in marriage, I do not plan to disqualify it from analysis simply because it doesn’t fit the dominant model, as Bengt Holbek does when comparing Danish versions of “King Wivern” (ATU 433B, “King Lindorm”).1 The fact that one of the tales does not end in marriage actually supports my interpretation of the tales as transgressive, a point to which I will return later.

Dundes’s (2007) notion of allomotif helps make sense of the kinship dynamics in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” In order to decipher the symbolic code of folktales, Dundes proposes that any motif that could fill the same slot in a particular tale’s plot should be designated an allomotif. Further, if motif A and motif B fulfill the same purpose in moving along the tale’s plot, then they are considered mutually substitutable, thus equivalent symbolically. What this assertion means for my analysis is that all the methods by which the brothers are enchanted and subsequently disenchanted can be treated as meaningful in relation to one another. One of the advantages of comparing allomotifs rather than motifs is that we can be assured that we are analyzing not random details but significant plot components. So in “The Six Swans” and “The Seven Ravens,” we see the parental curse causing both the banishment and the enchantment of the brothers, whereas in “The Twelve Brothers,” the brothers are banished and enchanted in separate moves. Even though the brothers’ exile and enchantment happen in a different sequence in the different texts, we must view their causes as functionally parallel. Thus the ire of a father concerned for his newborn daughter, the jealous rage of a stepmother, the homicidal desire of a father to give his daughter everything, and the innocent flower gathering of a sister can all be seen as threatening to the brothers. All of these actions lead to the dispersal and enchantment of the brothers, though not all are malicious, for the sister in “The Twelve Brothers” accidentally turns her brothers into ravens by picking flowers that consequently enchant them.

I interpret this equivalence as a metaphorical statement—threats to a family’s cohesion come in all forms, from well-intentioned actions to openly malevolent curses. The father’s misdirected love for his sole daughter in two versions (“The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens”) translates to danger to his sons. This danger is allomotifically paralleled by how the sister, without even knowing it, causes her brothers to become enchanted, either by picking flowers in “The Twelve Brothers” or through the mere incident of her birth in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens.” The fact that a father would prioritize his sole daughter over numerous sons is strange and reminiscent of tales in which a father explicitly expresses romantic de[1]sire for his daughter, as in “Allerleirauh” (ATU 510B), discussed in chapter 4 by Margaret Yocom. Even in “The Six Swans,” where a stepmother with magical powers enchants the sons, the father is implicated; he did not love his children well enough to protect them from his new spouse, and once the boys had been changed into swans and fled, the father tries to take his daughter with him back to his castle (where the stepmother would likely be waiting to dispose of the daughter as well), not knowing that by asserting control over her, he would be endangering her. The father’s implied ownership of the daughter in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” and the linking of inheritance with danger emphasize the conflicts that threaten the nuclear family. Both material and emotional resources are in limited supply in these tales, with disastrous consequences for the nuclear family, which fragments, as it does in all fairy tales (see Propp 1968).

Holbek reaches a similar conclusion in his allomotific analysis of ATU 451, though he focuses on Danish versions collected by Evald Tang Kristensen in the late nineteenth century. Holbek notes that the heroine is the actual “cause of her brothers’ expulsion in all cases, either—innocently—through being born or—inadvertently—through some act of hers” (1987, 550). The true indication of the heroine’s role in condemning her brothers is her role in saving them, despite the fact that other characters may superficially be blamed: “The heroine’s guilt is nevertheless to be deduced from the fact that only an act of hers can save her brothers.” However, Holbek reads the tale as revolving around the theme of sibling rivalry, which is more relevant to the cultural context in which Danish versions of ATU 451 were set, since the initial family situation in the tale was not always said to be royal or noble, and Holbek views the tales as reflecting the actual concerns and conditions of their peasant tellers (550; see also 406–9).2 Holbek also discusses the lack of resources that might lead to sibling rivalry, identifying physical scarcity and emotional love as two factors that could inspire tension between siblings.

The initial situation in the Grimms’ versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is also a comment on the arbitrary power that parents have over their children, the ability to withhold love or resources or both. The helplessness of children before the strong feelings of their parents is cor[1]roborated in another Grimms’ tale, “The Lazy One and the Industrious One” (Zipes 2002b, 638).3 In this tale, which Jack Zipes translated among the “omitted tales” that did not make it into any of the published editions of the KHM, a father curses his sons for insulting him, causing them to turn into ravens until a beautiful maiden kisses them. Essentially, the fam[1]ily is a site of danger, yet it is a structure that will be replicated in the tale’s conclusion . . . almost.

But first, the sister seeks her brothers and disenchants them. The symbolic equation links, in each of the three tales, the sister’s silence (neither speaking nor laughing) for six years while sewing six shirts from asters, her seven years of silence (neither speaking nor laughing), and her cutting off her finger and using it to gain entry to the glass palace where she disenchants her brothers merely by being present. The theme unifying these allomotifs is sacrifice. The sister’s loss of her finger, equivalent to the loss of her voice, is a symbolic disempowerment. One loss is a physical mutilation, which might not impair the heroine terribly much; the choice not to use her voice is arguably more drastic, since her inability to speak for herself nearly causes her death in the tales.4 Both losses could be seen as equivalent to castration.5 However, losing her ability to speak and her ability to manipulate the world around her while at the same time displaying domestic competence in sewing equates powerlessness with feminine pursuits. Bear notes that versions by both the Grimms and Hans Christian Andersen envision “a distinctly feminine savior whose work is symbolized by her spindle, an ancient emblem of women’s work” (2009, 46). Ruth Bottigheimer (1986) points out in her essay “Silenced Women in Grimms’ Tales” that the heroines in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Six Swans” are forced to accept conditions of muteness that disempower them, which is part of a larger silencing that occurs in the tales; women both are explicitly forbidden to speak, and they have fewer declarative and interrogative speech acts attributed to them within the whole body of the Grimms’ texts.

Ironically, in performing subservient femininity, the sister fails to perform adequately as wife or mother, since the children she bears in one version (“The Six Swans”) are stolen from her. When the sister is married to the king, she gives birth to three children in succession, but each time, the king’s mother takes away the infant and smears the queen’s mouth with blood while she sleeps (Zipes 2002b, 170). Finally, the heroine is sentenced to death by a court but is unable to protest her innocence since she must not speak in order to disenchant her brothers. In being a faithful sister, the heroine cannot be a good mother and is condemned to die for it. This aspect of the tale could represent a deeply coded feminist voice.6 A tale collected and published by men might contain an implicitly coded feminist message, since the critique of patriarchal institutions such as the family would have to be buried so deeply as to not even be recognizable as a message in order to avoid detection and censorship (Radner and Lanser 1993, 6–9). The sis[1]ter in “The Six Swans” cannot perform all of the feminine duties required of her, and because she ostensibly allows her children to die, she could be accused of infanticide. Similarly, in the contemporary legend “The Inept Mother,” collected and analyzed by Janet Langlois, an overwhelmed mother’s incompetence indirectly kills one or all of her children.7 Langlois reads this legend as a coded expression of women’s frustrations at being isolated at home with too many responsibilities, a coded demand for more support than is usually given to mothers in patriarchal institutions. Essentially, the story is “complex thinking about the thinkable—protecting the child who must leave you—and about the unthinkable—being a woman not defined in relation to motherhood” (Langlois 1993, 93). The heroine in “The Six Swans” also occupies an ambiguous position, navigating different expectations of femininity, forced to choose between giving care and nurturance to some and withholding it from others.

Here, I find it productive to draw a parallel to Antigone, the daughter of Oedipus. Antigone defies the orders of her uncle Creon in order to bury her brother Polyneices and faces a death sentence as a result. Antigone’s fidelity to her blood family costs her not only her life but also her future as a productive and reproductive member of society. As Judith Butler (2000) clarifies in Antigone’s Claim: Kinship between Life and Death, Antigone transgresses both gender and kinship norms in her actions and her speech acts. Her love for her brother borders on the incestuous and exposes the incest taboo at the heart of kinship structure. Antigone’s perverse death drive for the sake of her brother, Butler asserts, is all the more monstrous because it establishes aberration at the heart of the norm (in this case the incest taboo). I see a similar logic operating in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” because according to allomotific equivalences, the heroine is condemned to die only in one version (“The Six Swans”) because she allegedly ate her children. In the other version that contains the marriage episode (“The Twelve Brothers”), the king’s mother slanders her, calling the maiden “godless,” and accuses her of wicked things until the king agrees to sentence her to death (Zipes 2002b, 35). As allomotific analysis reveals, in the three versions, the heroine is punished for being excessively devoted to her brothers, which is functionally the same as cannibalism and as being generally wicked (the accusation of the king’s mother in two of the versions).

In a sense, the heroine’s disproportionate devotion to her brothers kills her chance at marriage and kills her children, which from a queer stance is a comment on the performativity of sexuality and gender. According to Butler, gender performativity demonstrates “that what we take to be an internal essence of gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylization of the body” ([1990] 1999, xv). This illusion, that gender and sexuality are a “being” rather than a “doing,” is constantly at risk of exposure. When sexuality is exposed as constructed rather than natural, thus threatening the whole social-sexual system of identity formation, the threat must be eliminated.

One aspect of this system particularly threatened in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is reproductive futurism, one form of compulsory teleological heterosexuality, “the epitome of heteronormativity’s desire to reach self-fulfillment by endlessly recycling itself through the figure of the Child” (Giffney 2008, 56; see also Edelman 2004). Reproductive futurism mandates that politics and identities be placed in service of the future and future children, utilizing the rhetoric of an idealized childhood. In his book on reproductive futurism, Lee Edelman links queerness and the death drive, stating, “The death drive names what the queer, in the order of the social, is called forth to figure: the negativity opposed to every form of social viability” (2004, 9). According to this logic, to prioritize anything other than one’s reproductive future is to refuse social viability and heteronormativity—this is what the heroine in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” does. Her excessive emotional ties to her brothers disfigure her future, aligning her with the queer, the unlivable, and hence the ungrievable. Refusing the linear narrative of reproductive futurism registers as “unthinkable, irresponsible, inhumane” (4), words that could very well be used to describe a mother who is thought to be eating her babies and who cannot or will not speak to defend herself.

The heroine’s marriage to the king in two versions of the tale can also be examined from a queer perspective. Like the tale “Fitcher’s Bird,” which queers marriage by “showing male-female [marital] relationships as clearly fraught with danger and evil from their onset,” the Grimms’ two versions of ATU 451 that feature marriage call into question its sanctity and safety (Greenhill 2008, 150, emphasis in original). Marriage, though the ultimate goal of many fairy tales, does not provide the heroine with a supportive or nurturing environment. Bear comments that in versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” wherein a king discovers and marries the heroine, “the king’s discovery brings the sister into a community that both facilitates and threatens her work. The sister’s discovery brings her into a home, foreshadowing the hoped-for happy ending, but it is a false home, determined by the king’s desire rather than by the sister’s creation of a stable and complete community” (2009, 50)

#queering the grimm#queering the grimms#queer fairytales#the maiden who seeks her brothers#the twelve brothers#the six swans#the seven ravens#grimm fairytales#fairytale analysis#fairytale type

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi - asking in good faith here, but I am also relatively new to active anti-racism (im white, grew up in all white areas, and didn't encounter anti racist perspectives until college). In the last few years I've done a LOT of reading about anti-black racism, black feminist theory, womanism, etc, and I'm beginning to understand why the bastardization and appropriation of aave is so harmful. I don't want to put my friends of color on the spot about this or make them feel pressured to answer a certain way, though, and I DO want an answer that's grounded in theory and thoughtfulness about these things (two traits my circle of 18-20 year olds sometimes lacks, understandably). I know that that might put a lot of pressure on you as well but please know that while I do respect your opinion, I know you're just one Black person with one opinion - and of course if an irl Black friend ever came to me and told me to stop I would.

My question is, if I am making sure to attribute it correctly as AAVE, being careful to make sure I'm using it appropriately, and of course listening in case I hear I've misused it - is it still harmful for me as a white person to use aave? Is it possible to use aave non-harmfully as a white person, among Black friends? Or would it be better for me to do my best to remove those words and phrases and grammatical structures from the way I speak entirely?

A lot of these things, I pick up FROM my friends, and they haven't, idk, made faces or suggested I should stop or anything like that. But of course it's hard to sort out what I pick up from my friends, what I pick up from Black literature (im a terrible parrot from my books unfortunately 😬), and what comes from the intern*t lol. So there's obviously the potential to misuse or disrespect aave, especially if I ever stop being thoughtful about what I say and where I first hear it. And while I have tried to read up on the appropriation of AAVE and develop my own opinion, this really does seem like one of those things where as a white person my opinion is always going to be a little out of touch - and I REALLY don't want to hurt and alienate my friends and accidentally advance racism in my community because I felt qualified to comment on this.

I don't know. I grew up in a very white enclave in a very white area of a very white state, and I AM trying to catch up and think critically about what I do say and think, but honestly, I am very new to these things. So if this is a dumb question or I am inadvertently ignorant/inappropriate, I'm really sorry about that and please know that I AM trying to do better. (And I will never say no to specific resource recommendations. I've read everything you usually read in an intro to Africana studies course lol but there is so much out there!!)

Thanks, either way. I appreciate you taking the time to read this extremely long winded ask lol. And I appreciate the way you blog about these things and how you make it clear where and from what you develop your opinions - that's super helpful!!!

-bee

Well as you said I am one person and I do not know you or talk to you really so I can't really say yes or no on your specific case. But also I would challenge you to ask yourself why you felt you needed the permission of a black stranger rather than actually sit down and talk to your friends about it.

I have said in other posts that it is less about needing to be black to speak AAVE and more about respect. I am all for cultural sharing and appreciation and I do not think that culture requires specifically only blood ties. I'm a mixed race person, after all, and one who has a quite large mixed race extended and found family. I think that blood is not the only thing that defines us.

But I also think that one must go into these sorts of conversations with respect. My white (passing) mother can understand my black family speaking AAVE, despite the fact that there was a single black kid in her neighborhood and school system when she grew up. This is because she treated my dad and his family with respect, and so they are comfortable speaking this way in front of her, and she is comfortable asking for clarification if she needs it, which is quite rare nowadays considering she's been married to my dad for 35 years and in a relationship with him for 42 and has thus had a lot of practice.

But she also doesn't use AAVE herself. To her, it would be disrespectful. She did not grow up in it. It is not her culture. It is shared with her due to proximity to said culture with her husband and father of her children. But for her, she chooses to continue to use the Pennsylvania Dutch-influenced dialect she grew up in, which is a very white Appalachian specific-to-Pennsylvania dialect and culture. I myself switch back and forth between the two, depending on who I'm talking to. Sometimes in the same conversation, if I'm talking to my mom vs my dad in the same room.

I don't think any of my black family would be offended if she did use AAVE, though again with her personality and the way she has approached this over the last several decades I think they'd be surprised if she suddenly did it like tomorrow or something. But she herself does not think it would be respectful of the culture, the dialect, or of her husband and inlaws for it to come out of her mouth. And I am sort of inclined to agree. Outside of a few slang words that have become so distant from their roots that it is difficult to say they are *purely* AAVE anymore, similar with many historically-Yiddish slang words, I do not personally think she could hold a conversation in AAVE and do it respectfully enough to not be offensive. It's just not really hers to do that with.

On the other hand, when I worked in a mostly-black store in an area that was significantly more black-populated, where I rarely had to code switch and mostly used AAVE all the timewith clients and customers, there were nonblack people who also used and understood AAVE. I had no problem with this, even with the white people doing it, because that was just how everyone in that area spoke. And, mot for nothing, but I found those white people to be as a general rule significantly less racist in their treatment of me and of other people of color, and racial mixing was significantly more common. Again, it's about respect. Even if it's not really a concious thing.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

I fell out of love with Sarah J Maas books a while back, but watching her descent into madness and watching the fanbase build, then turn toxic, has been the most interesting thing to me. I guess you could say I grew as a reader alongside her as a writer, but keep in mind, I’m old now.

She started out as one of us, an online poster. I’m about to show my age here but she wrote Queen of glass, which would later become throne of glass series, on fictionpress in the mid 2000s. She definitely would have been a watpad girlie. I remember her responding and engaging with those of us who followed her and really taking feedback to heart. She was so excited when her book, eventually, got picked up and was especially keen on it being available on the kindle store. She would release novellas for kindle exclusives and was so proud it. I remember her so exited to write for DC comics at one point. She even made a little YouTube video with cat ears on asking us to read it. (she fumbled that so hard btw)

When the first few TOG books first came out remember there being no fanbase, no fan art, no online discussions on theories. Ghost town. As someone who had followed since the beginning it was just nice to see someone get flowers for their hard work. She still engaged with her followers, she loved specific fan artists and spreading their work on socials, and eventually started having her favourite fan artists make art for the physical copies of her books. Still a woman of the people. Still taking notes.

THEN ACOTAR, and something shifted in the wind. It’s odd to see a woman so keen on the YA genre just decide one day…. Nah I’m good. I think that’s the appeal. She was writing YA for the people who were beginning to age out of YA at the time. Since then the books exploded, and in my opinion, dropped in quality with every release. I can’t say when it was but at one point she just… removed her self. Stopped getting involved in discussions and engaging with people. Which professionally, smart move. Creatively though, keep in mind this woman THRIVED on online feedback at one point.

Ironically Sarah has since built her self a new reputation in the last 12 years of publishing. With hit after hit She’s a gatekeeper and a hater, who is mean to new and upcoming authors, won’t play well others, and won’t take an editors advice to save her life. I hear editors flat out refuse to work with her now which is so ironic.

I was once so happy to see her get popular, but now it’s just embarrassing to be associated with her new fans. Fans who bully an actress and fat shame her while gushing about their “kind of” feminist “icon” love interest… it’s not the group I want to be associated with anymore.

Anyway thanks for coming to the ted talk of a former SJM fan.

Love your work! Keep being you!

i admit, i'm not very dialed in to SJM as a sort of... institution. in my experience, this attitude toward editing is very common, especially in people who found success in the past. i don't edit on anywhere near this scale, but it's just so. who do you think helped you put the good in it. obviously this is your baby but i want your baby to blossom into a beautiful adult someday. please listen to me. please.

more power to her for success and clearly it's working for her. i'm throwing stones from the sewer up at mount olympus. i don't begrudge anyone liking her books. they're just not for me.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/cyber-corp/772774979166240768/a-good-friend-of-mine-said-to-me-the-other-day?source=share

In reblogs to this post you recommended that person to read Bell Hooks, any books in particular that you'd recommend? As a starting point ofc. She seems to have quite a few.

I'm a little weird about men admittedly, and I'm trying to get better in that sense, at the very least because if you hate half the population it kind of eats you from the inside. I'd never say something like the thing from the post to a person, but still. Your recommendation caught my attention.

Thanks for reading this and, if you respond, for your response too!

Post linked above

When it comes to bell hooks and men, The Will to Change is the one I'd start with. The way she writes about masculinity is very refreshing in terms of a lot of other feminist theory, and I don't think it's a particularly challenging book academically speaking. It does push you to open your mind more and think about feminism more holistically, but it's not a book where you're constantly looking up terms and definitions.

There's also her short story Be Boy Buzz that is about what it means to be a boy and how we should celebrate the being of a boy. It's a quick read and also a very fun read. It's more specifically about being a black boy, but you can extrapolate outside of it.

We Real Cool, which would be my next recommendation, is specifically about black men and masculinity. It's a collection of ten essays and they are about being a black man in a culture that is white. I would say it's required reading when it comes to unpacking racism and white supremacy.

Though they are much more about feminism in general than specifically feminism and men, I would also recommend Feminism Is For Everybody and Feminist Theory: From Margin To Center. Both books cover the kind of topics that a lot of mainstream feminist theory often glosses over or ignores, e.g. race and class. They cover men and masculinity, but aren't about that only.

You might also find something worthwhile in Communion: The Female Search For Love about this topic; it's also got stuff about lesbianism and loving one's self. I don't remember if it's officially a series, but it's the third book in hooks' series talking about love.

There's also Uncut Funk, which is written by bell hooks and Stuart Hall, and is very much about the discourse between them. It's an interesting read and you might find some interesting things in there.

It's not related to hooks' writing on masculinity at all, but I just have to recommend Ain't I a Woman; it's such an important piece of feminist writing.

Also by the way, bell hooks specifically chose her pen name to be in all lowercase; a lot of feminist women in the 60s and 70s were doing it too.

Honestly, hats off to you anon for being able to recognise that about yourself and making direct steps as to improve yourself. It's difficult to admit flaws of your own and even more difficult to make action to try and remedy them in some way.

It's especially difficult to recognise that in our current political climate when there are a lot of men publicly showing off the uglier sides of humanity.

Anyway, I hope this was helpful for you anon and good luck on your reading :]

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! so glad to see you posting again I like a lot of what you have to say about Snape. I noticed you say a few times tho that your visual headcanon for Snape isn't conventionally attractive and I just wondered if you had any reference of what he looks like in your mind? An actor or other famous person? just someone like that?

I'm just curious how you imagine Snape because I admit I just see Alan Rickman as Snape in my head since I started with the movies as a kid and didn't read the books a few until years later. It always interests me so much when people say they read the books before the movies or read the books with the movies coming out and saw Snape as someone else.

Its ok if you can't think of anyone just thought I'd ask. thx!

Hello!

*waves enthusiastically like an idiot with zero chill*

I get so giddy when someone sends me an ask like this so I hope no one thinks I don't enjoy questions about Snape or my headcanons. As anyone who knows me knows, I think a lot and especially about those things I love so I always have lots of thoughts rolling around in my head I can be positively overeager to share with anyone interested.

So to answer your question, I don't have a specific person pinned down that is 100% like how I picture Snape in my mind but some close candidates would be a young Adrien Brody (which I think is common enough among Snape fans as a choice, right there with Adam Driver these days), obviously the man that JKR based Snape around, John Nettleship, someone like Adarsh Jaikarran as a potential Hogwarts-era and early 20s Snape (even if he is more good-looking than I usually lean, in some pictures he just channels Snape vibes for me quite a bit) and a very young Julian Richings if you've ever seen photos of him in his younger years (I have two here for you so you can see my point a bit, here and here).

Ironically, Julian Richings in the later years of his acting career would probably have been my first choice for a Voldemort fan cast back in the day when any Harry Potter reboot was purely in the realm of the hypothetical (I mean, c'mon, look at this and tell me you can't see it too) but as JKR is an unapologetic anti-feminist/TERF I provide no monetary support to any of her projects including any licensed games, the watching of future reboots or purchasing of future tie-in books in the HP universe, officially licensed HP merchandise, or even by giving traffic to what was formerly Pottermore, etc.

All I bring to the fandom now is my fan theories and love for Snape, which she not only does not benefit from but never seemed entirely at peace with given how the character got away from her and took off. I can't think of a better way to spite someone so utterly spiteful herself than to take the character she was most shocked by people loving in any capacity and celebrate him in every incarnation (gay, bi, trans, ace, autistic, poc, etc.) with my queer, gender-nonconforming little heart while she gets zero money off me for it.

Anyway I hope the visual guide gives you a little more insight into my mind. I've never seen Snape as "ugly" (even when I joke my Snape is "ugly" and I like him that way) but my mental picture of him is of a man whose looks might fall into that unconventionally attractive sphere or what some people call homely. Occasionally I veer off that a bit, as with Adarsh Jaikarran, oh, oh! And also Lee Soo Hyuk, Song Jae-Rim and Kento Yamazaki (ever since I saw him in the live-action Bloody Monday manga series adaptation)!

But yes, my favorite Snape and the Snape I love isn't usually model attractive but also not quite the gargoyle Harry describes (that kid had some ridiculously high standards of beauty tbh, about the only characters he didn't have mentally critical notes on their appearance was the unnamed Veela, Fleur, and Narcissa Malfoy so yeah he totally thought "Draco's mom has got it going on..." Lol!) but somewhere in that "unconventional" categorization of attractive which I feel really suits a man who so often defies easy categorization in general.

(Excuse all the edits. After I gave a few examples more started hitting me and I was like ohhhhh I should have shared them, why didn't I think to share them? So I may come back and make more edits throughout the day, no promises I won't! Lol)

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

17 for the book ask?

Oh! I feel like i was surprised by how good a lot of books were this year - I'm not sure I often have expectations of books or sometimes when I'm really overexcited for a book, it's a letdown to read it, but I'm going to flag some favourites from this year where I didn't know the author at all before:

Joseph Pontus, On the Line: Notes from a Factory - complete impulse read from the library; a set of poems by a French social worker who finds himself working a factory job packing seafood because he's living with his girlfriend in Brittany, and there's no other work there. There's one poem just about his hatred of pressing tofu. But it was so good - fascinating and crushing and transcendent about the boredom and pain and unfairness of manual work. It really made me think how few books get published, particularly since the 1970s, about the experience of blue-collar work; how much it's still invisible. And what good poetry it was.

Swing Time, Zadie Smith. I'm a British book nerd who never had read a Zadie Smith book before 2024 somehow and this was again, an impulse read from the library which I loved - not so much for the exact details of the plot but for Smith's authorial voice, for the flow of ideas and observations, for how witty it was.

Nowhere in Africa, Stefanie Zweig. One of feuilljska's books I read while down with Covid, a memoir of fleeing as a Jewish refugee family to Kenya - the family decide to go back to Germany in 1946, and I have the author's sequel memoir about *that* on my shelf. It's such an immersive child's-eye view, full of romance and adventure as well as the wrenching trauma and dislocation the family suffers, and the complex and touching relationship between the refugee farmers and the Kenyans they interact with; history always gets more complex than you think.

Night Theatre, Vikram Paralkar. Thank you library! I wrote this book up already but it was *so* good and I had no idea what to expect when I picked it up.

Namesake, N.S. Nuseibeh. Another library pick - this one the memoir of an author named after a famous Muslim warrior woman, exploring the idea of what her relationship to her namesake means and the idea of being a warrior woman as a modern British-Palestinian woman who goes to her friend's seders and reads feminist theory. It was such a thoughtful, deep, wideranging book and really touched me - I think I've given quite a reductive summary.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

i’m curious if you’re comfortable answering what places have you branched out to besides the atlantic as you’ve moved further left???

so this is hard to answer, because you can't just go to one source. i didn't just replace the atlantic with a single other publication, i just outgrew it.

anyway, i read A LOT. i've always been interested in issues of gender, inequality, prejudice, even before i knew what they were called. so beyond resources, i encourage you to read a lot, read from many different sources, and read critically. it is up to you to distill the truth from fiction, opinion from fact. also, you must think critically. you have to take the information and apply it, let it challenge you, let it stack up in your brain until you have convictions that you can actually justify.

🚨 also, disclaimer: i do not endorse EVERYTHING these publications or sites have printed. i don't co-sign every opinion these activists hold. i am sorry if i am ignorant to some crime against humanity within! i'm certain all the resources here are considered "problematic" or biased in some way, or to someone. some publications serve corporate interests, some have problematic business practices, some writers have problematic histories, and some of the info will challenge your worldview in a way that might seem harmful and cause you to deem them problematic. 🚨

mainstream news is still essential to stay aware of what's going on in the world (al jazeera, npr, cnn, to name a few) -- but these are some of the corporate interests i was talking about. they're biased, heavily, but sadly can't think of a news site that covers world news that isn't somehow beholden to their corporate overlords.

magazines, such as: mother jones, the nation, tempest, jacobin, dissent, inverse (for science) -- some of these are socialist publications. some, like mother jones, do excellent investigative reporting. you must know the difference between that and editorial - they are all valuable, but they aren't interchangeable. you will find a lot of editorials/opinions here, and you should assume any of them are owned by a bigger company and might be subject to their interests.

a selection of books i've loved at various times in my life: "aint i a woman? Black women and feminism" and "feminist theory" by bell hooks; "revolution and evolution" by grace lee boggs; "so you want to talk about race?" by ijeoma oluo; "bad feminist" by roxane gay; "unpacking the invisible knapsack" by peggy mcintosh; the publications of jackson katz, who researches what we now call toxic masculinity.

i also follow a lot of activists/thinkers, such as:

ericka hart - sexuality and Black history educator

tarana burke - founder of the metoo movement, Black feminist activist

laura danger - discusses domestic labor and gender inequality in relationships, and how global inequality creates it

megan jayne crabbe - writer and body positivity activist

ijeoma oluo - activist and author of "so you want to talk about race?"

abolition notes - not an activist, but a resource for educational material

following magazines and activists is probably the "easiest" solution, because you can expose yourself over time. read articles as they interest you, don't look away when activists say something that initially seems too extreme. idk! hope this helps!!

#recs#turning off rbs for now because i don't know if i want this to escape containment#socio#politics

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Found a saved copy of this ask from a few years back, before my original tumblr got nuked for no reason. Still stand by it:

______________________________________

Anonymous asked: Do you believe all feminists are hateful? I use the word but I just want equality, and that includes standing up for trans people, male rape victims, etc

-----------------------

No, I believe the great majority of people who identify as feminist are otherwise rational, concerned, well-meaning people who have been hoodwinked and peer-pressured into supporting a hateful, bigoted and appallingly destructive ideology by having it sold to them as a force for good through a relentless campaign of hysteria-inducing propaganda and brute force attempts to corner the market on the word ‘equality’.

On the other hand, I think the great majority of radical feminists are either profoundly damaged or sociopathic individuals seeking to project their own internal uglinesses onto the rest of the the world, people we would all avoid like the plague if they did not have this ‘we just want to help the poor defenceless women, you don’t hate women, do you?’ mask to hide behind. And the problem is, all feminist theory (’The Patriarchy’, ‘rape culture’, ‘the pay gap’, etc) originates only with radical feminists - yes, becoming more diluted as it reaches the mainstream, but still exclusively rooted in the same unhinged, irrational, ideology.

Radical feminism is not fringe feminism but core feminism: the ‘why can’t we all just get along’ feminists don’t write the books on feminist theory taught to young, impressionable minds in gender studies classes around the world, or teach those classes, or draw up the petitions to lobby for anti-male legislation, or organize feminist action groups, etc. The feminists who make a life of it (and a living off it) are all RadFems, and the proclamations pretty much every single one of them make about ‘MEN’ would sound like the most unmistakably horrific genocidal hate speech to everyone overhearing them if they were only talking about any other group of people on planet earth. If you don’t believe me, just try mentally inserting the word ‘black’ or ‘gay’ in front of the word ‘men’ the next time you read any feminist text or listen to one of them rant.

If you want equal rights and treatment for all people, there are other words you can use to describe yourself rather than ‘feminist’ - such as ‘egalitarian’ - which are far less loaded with hateful bigotry and accompanying crazed ideological assumptions about the world. You don’t need 60 years of hysterical conspiracy theories to say you don’t want women or men to be discriminated against, all you need to do is say what you think.

So my recommendation for you would simply be to express what you think and believe on your own and in your own way, without being forced to adopt the ideological framework and scaffolding of a hateful political movement with its many accompanying agendas.

Distrust the hive mind. Be yourself.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Really specific ask: anyone know of fiction books written by scholars in different fields (meaning different from fiction/lit)? My last few favorite books have been written by authors who have expertise in other fields and bring that expertise to their fiction - Carl Sagan brings his science and math knowledge to Contact, Mark Z. Danielewski brings his film knowledge to House of Leaves, Rachel Yoder brings her knowledge of qualitative research methods and feminist theory to Nightbitch... Etc. idk they just bring something so unique to fiction I wanna read a lot more like em. Please help me.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

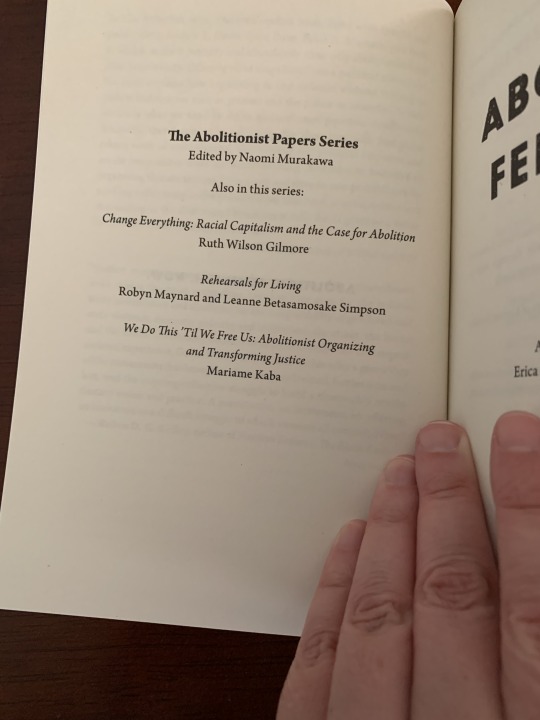

Hey so that reminds me. I have this book — Abolition. Feminism. Now. By Angela Y Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R Meiners, and Beth E Richie, copyright 2022 so very recent — that I have yet to crack open and could use some gentle encouragement to actually read.

And here you are, presumably on tumblr to be entertained, edified, and/or have your brain put through a blender for a few minutes. So let’s have a poll.

[Image descriptions:

Book cover (title and authors as above, abstract background in orange, reddish, and violet tones.)

Back cover. Purple background. Orange and white text reads: “An urgent, vital contribution to the indivisible projects of abolition and feminism, from leading scholar-activists Angela Y David, Gina Dent, Erica R Meiners, and Beth E Richie. As a politic and a practice, abolition increasingly shapes our political moment — halting the construction of new jails and propelling movements to divest from policing. Yet erased from this landscape are not only the central histories of feminist — usually queer, anti capitalist, grassroots, and women of color-led — organizing that continue to cultivate abolition but also a recognition of the stark reality: abolition is our best response to endemic forms of state and interpersonal gender and sexual violence. Amplifying the analysis and the theories of change generated from vibrant community-based organizing, Abolition. Feminism. Now. traces necessary historical genealogies, key internationalist leanings, and everyday practices to grow our collective and flourishing present and futures.

Table of contents. Includes: preface, introduction, part 1 abolition. Part 2 feminism. Part 3 now. Epilogue. Appendices: intimate partner violence and state violence power and control wheel. Incite!-critical resistance statement on gender violence and the prison industrial complex. Reformist reforms vs abolitionist steps to end imprisonment. Further resources. Notes. Image permissions. Index.

list of other books in the abolitionist papers series, edited by Naomi Murakawa, namely: Change Everything: Radical Capitalism and the Case for Abolition by Ruth Wilson Gilmore; Rehearsals for Living by Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson; and We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transformative Justice by Mariame Kaba

Replicated image in the book of a pamphlet cover created by Jeff George and distributed by Survived and Punished (an organization that advocated for incarcerated survivors of abuse.) There is a large line drawing of a scale out of balance with a man in a business suit, large stacks of money, and sky scrapers on the heavy end and a small group of protesters holding a sign saying “free all survivors” on the other end. Large handwritten text says “no good prosecutors now or ever” and smaller stencil-like text says “how the Manhattan district attorney hoards money, perpetuated abuse of survivors, and gags their advocates.”

End image descriptions.]

#It would be so much less effort to just read say 10 or 15 pages of this thing and yet#It’s not a large book it’s under 250 pages#I literally had not cracked open the book before starting the post so I didn’t realize there aren’t ‘chapters’#So much as three main parts

13 notes

·

View notes