#History of Steampunk

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Old Pencil Sharpener in Action

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Origin and History of Steampunk: Its Influence on TV, Films, Music, and Modern Culture

Steampunk, a subgenre of science fiction, is distinguished by its retro-futuristic aesthetic that merges the Victorian era’s design and technological innovations with speculative technological advances. The movement, however, extends beyond just a literary genre—it has evolved into an all-encompassing artistic and cultural phenomenon. This essay delves into the origins of steampunk, its…

#20#20000 Leagues Under the Sea (1916)#Aesthetic#Airships#Alternate History#Amazon#Around the World In 80 Days (1956)#£3#Brass and Copper#Catherine Tate#Clockwork Technology#David Tennant#DIY Culture#Doctor Who#Doctor Who 60th Anniversary Specials | Doctor Who#Fantasy Technology#Films#Fullmetal Alchemist Trailer#Gears and Cogs#H G Wells#History#History of Steampunk#Industrial Revolution#Infernal Devices (1987)#innovation#Invention#Its Influence on TV#Jules Verne#Mechanical Inventions#Modern Culture

0 notes

Text

#silvergifting#tyelpe#celebrimbor#mairon#annatar#i'm so sad about them#like guys if somehow mairon managed to deal with his pride and stayed in eregion#then it would change the whole middle-earth history for the better#and both of this idiots would have a happy life with engineering stuff and avoiding questions#imagine steampunk eregion with railways and airships#technical progress goes weeee#elves and mairon together make ar-pharazon reconsider his middle-earth expancion#hobbits live happily ever after without any suspicious rings#and also sunglasses#they need sunglasses#mairon why are you a stupid idiot why you ruined all of that?#also i am not sorry

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bioshock: Why Individualism is a shitty philosophy to build society on

Bioshock 2: Why Collectivism is a shitty philosophy to build society on

Bioshock Infinite: Why American Exceptionalism is a shitty philosophy to build society on.

#bioshock#bioshock 2#bioshock infinite#bioshock burial at sea#columbia#bioshock columbia#bioshock rapture#rapture#exceptionalism#american exceptionalism#anti capitalism#dystopia#biopunk#steampunk#alternate history#alternate universe#videogame#video game#anna dewitt#booker dewitt#American dystopia#American satire

691 notes

·

View notes

Text

#moodboard#aesthetic#icons#pinterest#indie#history#pirates#fantasy aesthetic#fantasy#gold coins#steampunk#piratas do caribe#caraibes#pirates of the caribbean#fantasycore#outfit inspo#book inspiration#inspo#inspiration

392 notes

·

View notes

Text

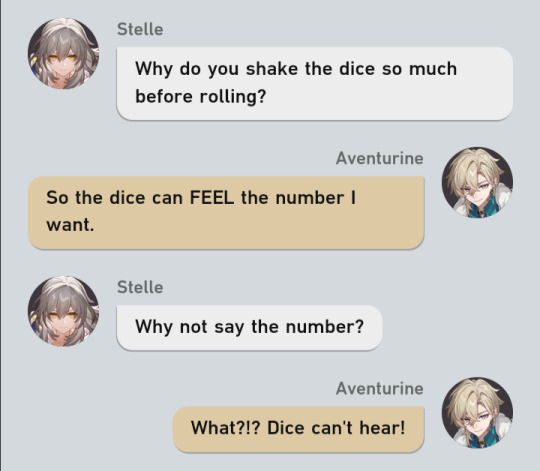

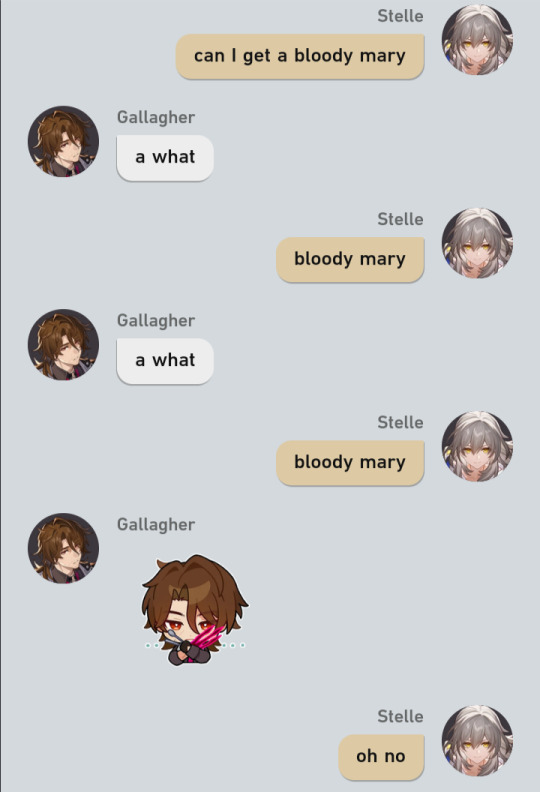

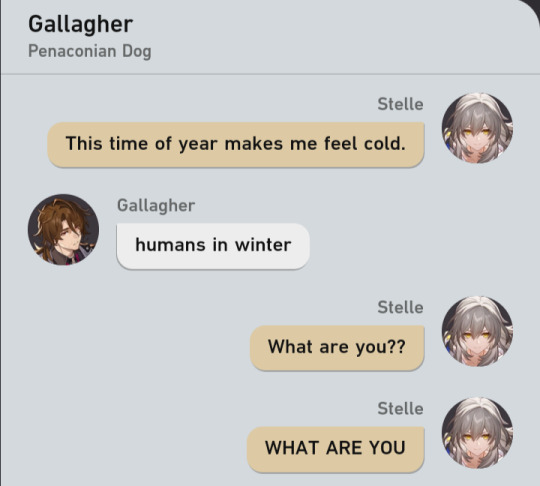

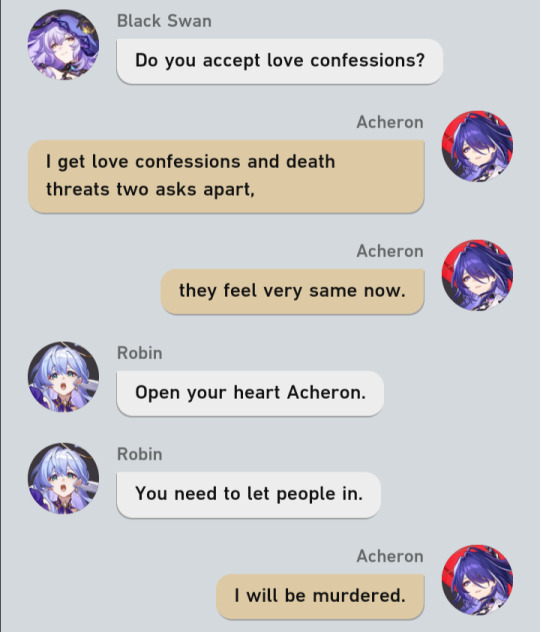

Penacony.

more from the post looooop:

#okay did this one in order of plot references from start of penacony to latest info#turns out i have too many of these for one post so i cut it down to mostly plot relevance.#im scared what is gonna happen next. plz firefly don't dieeeee#also i am guessing that our next full on new location is gonna be an ipc onw#because we are getting suddenly a LOT of ipc lore and 3 whole ass members are playable#and while it was in the illusion ending im gonna guess that if sunday lives then he's gonna go on that trial still#but that secret robin mission makes me scared#my other guesses are going to be one of the 3 locations we were asked on#i really want lushaka but its likely edo star if that's how we're going about this#but I'd really like to see glamoth (i know im ranting about it again) or sigonia bc those places have really interesting history#of course i want places like punklorde but like a lead into those aren't set yet.#i also wonder about that steampunk planet penacony was originally going to be.#sooo much to thiinnkkk#honkai star rail#honkai star rail memes#hsr sparkle#hsr black swan#hsr trailblazer#hsr stelle#hsr sampo#hsr acheron#hsr aventurine#hsr topaz#hsr dr ratio#hsr gallagher#hsr robin#hsr acheswan#hsr boothill#hsr jade#hsr firefly

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

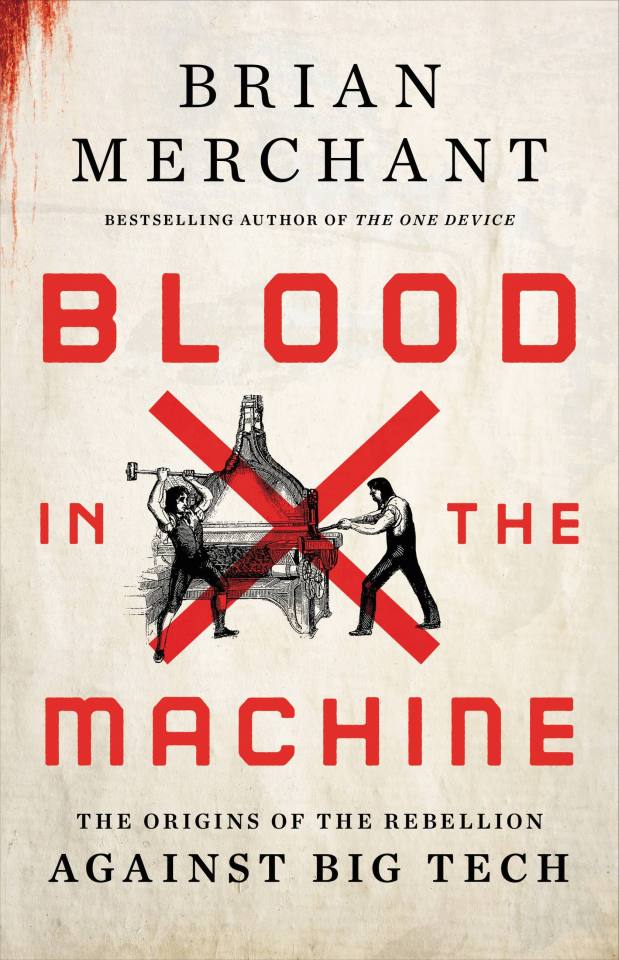

Brian Merchant’s “Blood In the Machine”

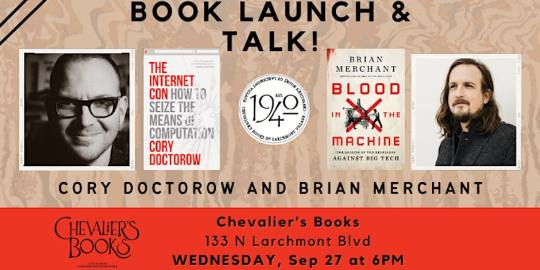

Tomorrow (September 27), I'll be at Chevalier's Books in Los Angeles with Brian Merchant for a joint launch for my new book The Internet Con and his new book, Blood in the Machine. On October 2, I'll be in Boise to host an event with VE Schwab.

In Blood In the Machine, Brian Merchant delivers the definitive history of the Luddites, and the clearest analysis of the automator's playbook, where "entrepreneurs'" lawless extraction from workers is called "innovation" and "inevitable":

https://www.littlebrown.com/titles/brian-merchant/blood-in-the-machine/9780316487740/

History is written by the winners, and so you probably think of the Luddites as brainless, terrified, thick-fingered vandals who smashed machines and burned factories because they didn't understand them. Today, "Luddite" is a slur that means "technophobe" – but that's neither fair, nor accurate.

Luddism has been steadily creeping into pro-labor technological criticism, as workers and technology critics reclaim the term and its history, which is a rich and powerful tale of greed versus solidarity, slavery versus freedom.

The true tale of the Luddites starts with workers demanding that the laws be upheld. When factory owners began to buy automation systems for textile production, they did so in violation of laws that required collaboration with existing craft guilds – laws designed to ensure that automation was phased in gradually, with accommodations for displaced workers. These laws also protected the public, with the guilds evaluating the quality of cloth produced on the machine, acting as a proxy for buyers who might otherwise be tricked into buying inferior goods.

Factory owners flouted these laws. Though the machines made cloth that was less durable and of inferior weave, they sold it to consumers as though it were as good as the guild-made textiles. Factory owners made quiet deals with orphanages to send them very young children who were enslaved to work in their factories, where they were routinely maimed and killed by the new machines. Children who balked at the long hours or attempted escape were viciously beaten (the memoir of one former child slave became a bestseller and inspired Oliver Twist).

The craft guilds begged Parliament to act. They sent delegations, wrote petitions, even got Members of Parliament to draft legislation ordering enforcement of existing laws. Instead, Parliament passed laws criminalizing labor organizing.

The stakes were high. Economic malaise and war had driven up the price of life's essentials. Workers displaced by illegal machines faced starvation – as did their children. Communities were shattered. Workers who had apprenticed for years found themselves graduating into a market that had no jobs for them.

This is the context in which the Luddite uprisings began. Secret cells of workers, working with discipline and tight organization, warned factory owners to uphold the law. They sent letters and posted handbills in which they styled themselves as the army of "King Ludd" or "General Ludd" – Ned Ludd being a mythical figure who had fought back against an abusive boss.

When factory owners ignored these warnings, the Luddites smashed their machines, breaking into factories or intercepting machines en route from the blacksmith shops where they'd been created. They won key victories, with many factory owners backing off from automation plans, but the owners were deep-pocketed and determined.

The ruling Tories had no sympathy for the workers and no interest in upholding the law or punishing the factory owners for violating it. Instead, they dispatched troops to the factory towns, escalating the use of force until England's industrial centers were occupied by literal armies of soldiers. Soldiers who balked at turning their guns on Luddites were publicly flogged to death.

I got very interested in the Luddites in late 2021, when it became clear that everything I thought I knew about the Luddites was wrong. The Luddites weren't anti-technology – rather, they were doing the same thing a science fiction writer does: asking not just what a new technology does, but also who it does it for and who it does it to:

https://locusmag.com/2022/01/cory-doctorow-science-fiction-is-a-luddite-literature/

Unsurprisingly, ever since I started publishing on this subject, I've run into people who have no sympathy for the Luddite cause and who slide into my replies to replicate the 19th Century automation debate. One such person accused the Luddites of using "state violence" to suppress progress.

You couldn't ask for a more perfect example of how the history of the Luddites has been forgotten and replaced with a deliberately misleading account. The "state violence" of the Luddite uprising was entirely on one side. Parliament, under the lackadaisical leadership of "Mad King George," imposed the death penalty on the Luddites. It wasn't just machine-breaking that became a capital crime – "oath taking" (swearing loyalty to the Luddites) also carried the death penalties.

As the Luddites fought on against increasingly well-armed factory owners (one owner bought a cannon to use on workers who threatened his machines), they were subjected to spectacular acts of true state violence. Occupying soldiers rounded up Luddites and suspected Luddites and staged public mass executions, hanging them by the dozen, creating scores widows and fatherless children.

The sf writer Steven Brust says that the test to tell whether someone is on the right or the left is simple: ask whether property rights are more important than human rights. If the person says "property rights are human rights," they are on the right.

The state response to the Luddites crisply illustrates this distinction. The Luddites wanted an orderly and lawful transition to automation, one that brought workers along and created shared prosperity and quality goods. The craft guilds took pride in their products, and saw themselves as guardians of their industry. They were accustomed to enjoying a high degree of bargaining power and autonomy, working from small craft workshops in their homes, which allowed them to set their own work pace, eat with their families, and enjoy modest amounts of leisure.

The factory owners' cause wasn't just increased production – it was increased power. They wanted a workforce that would dance to their tune, work longer hours for less pay. They wanted unilateral control over which products they made and what corners they cut in making those products. They wanted to enrich themselves, even if that meant that thousands starved and their factory floors ran red with the blood of dismembered children.

The Luddites destroyed machines. The factory owners killed Luddites, shooting them at the factory gates, or rounding them up for mass executions. Parliament deputized owners to act as extensions of law enforcement, allowing them to drag suspected Luddites to their own private cells for questioning.

The Luddites viewed property rights as just one instrument for achieving human rights – freedom from hunger and cold – and when property rights conflicted with human rights, they didn't hesitate to smash the machines. For them, human rights trumped property rights.

Their bosses – and their bosses' modern defenders – saw the demands to uphold the laws on automation as demands to bring "state violence" to bear on the wholly private matter of how a rich man should organize his business. On the other hand, literal killing – both on the factory floor and at the gallows – was not "state violence" but rather, a defense of the most important of all the human rights: the rights of property owners.

19th century textile factories were the original Big Tech, and the rhetoric of the factory owners echoes down the ages. When tech barons like Peter Thiel say that "freedom is incompatible with democracy," he means that letting people who work for a living vote will eventually lead to limitations on people who own things for a living, like him.

Then, as now, resistance to Big Tech enjoyed widespread support. The Luddites couldn't have organized in their thousands if their neighbors didn't have their backs. Shelley and Byron wrote widely reproduced paeans to worker uprisings (Byron also defended the Luddites in the House of Lords). The Brontes wrote Luddite novels. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein was a Luddite novel, in which the monster was a sensitive, intelligent creature who merely demanded a say in the technology that created him.

The erasure of the true history of the Luddites was a deliberate act. Despite the popular and elite support the Luddites enjoyed, the owners and their allies in Parliament were able to crush the uprising, using mass murder and imprisonment to force workers to accept immiseration.

The entire supply chain of the textile revolution was soaked in blood. Merchant devotes multiple chapters to the lives of African slaves in America who produced the cotton that the machines in England wove into cloth. Then – as now – automation served to obscure the violence latent in production of finished goods.

But, as Merchant writes, the Luddites didn't lose outright. Historians who study the uprisings record that the places where the Luddites fought most fiercely were the places where automation came most slowly and workers enjoyed the longest shared prosperity.

The motto of Magpie Killjoy's seminal Steampunk Magazine was: "Love the machine, hate the factory." The workers of the Luddite uprising were skilled technologists themselves.

They performed highly technical tasks to produce extremely high-quality goods. They served in craft workshops and controlled their own time.

The factory increased production, but at the cost of autonomy. Factories and their progeny, like assembly lines, made it possible to make more goods (even goods that eventually rose the quality of the craft goods they replaced), but at the cost of human autonomy. Taylorism and other efficiency cults ended up scripting the motions of workers down to the fingertips, and workers were and are subject to increasing surveillance and discipline from their bosses if they deviate. Take too many pee breaks at the Amazon warehouse and you will be marked down for "time off-task."

Steampunk is a dream of craft production at factory scale: in steampunk fantasies, the worker is a solitary genius who can produce high-tech finished goods in their own laboratory. Steampunk has no "dark, satanic mills," no blood in the factory. It's no coincidence that steampunk gained popularity at the same time as the maker movement, in which individual workers use form digital communities. Makers networked together to provide advice and support in craft projects that turn out the kind of technologically sophisticated goods that we associate with vast, heavily-capitalized assembly lines.

But workers are losing autonomy, not gaining it. The steampunk dream is of a world where we get the benefits of factory production with the life of a craft producer. The gig economy has delivered its opposite: craft workers – Uber drivers, casualized doctors and dog-walkers – who are as surveilled and controlled as factory workers.

Gig workers are dispatched by apps, their faces closely studied by cameras for unauthorized eye-movements, their pay changed from moment to moment by an algorithm that docks them for any infraction. They are "reverse centaurs": workers fused to machines where the machine provides the intelligence and the human does its bidding:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/17/reverse-centaur/#reverse-centaur

Craft workers in home workshops are told that they're their own bosses, but in reality they are constantly monitored by bossware that watches out of their computers' cameras and listens through its mic. They have to pay for the privilege of working for their bosses, and pay to quit. If their children make so much as a peep, they can lose their jobs. They don't work from home – they live at work:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/22/paperback-writer/#toothless

Merchant is a master storyteller and a dedicated researcher. The story he weaves in Blood In the Machine is as gripping as any Propublica deep-dive into the miserable working conditions of today's gig economy. Drawing on primary sources and scholarship, Blood is a kind of Nomadland for Luddites.

Today, Merchant is the technology critic for the LA Times. The final chapters of Blood brings the Luddites into the present day, finding parallels in the labor organizing of the Amazon warehouse workers led by Chris Smalls. The liberal reformers who offered patronizing support to the Luddites – but didn't imagine that they could be masters of their own destiny – are echoed in the rhetoric of Andrew Yang.

And of course, the factory owners' rhetoric is easily transposed to the modern tech baron. Then, as now, we're told that all automation is "progress," that regulatory evasion (Uber's unlicensed taxis, Airbnb's unlicensed hotel rooms, Ring's unregulated surveillance, Tesla's unregulated autopilot) is "innovation." Most of all, we're told that every one of these innovations must exist, that there is no way to stop it, because technology is an autonomous force that is independent of human agency. "There is no alternative" – the rallying cry of Margaret Thatcher – has become our inevitablist catechism.

Squeezing the workers' wages conditions and weakening workers' bargaining power isn't "innovation." It's an old, old story, as old as the factory owners who replaced skilled workers with terrified orphans, sending out for more when a child fell into a machine. Then, as now, this was called "job creation."

Then, as now, there was no way to progress as a worker: no matter how skilled and diligent an Uber driver is, they can't buy their medallion and truly become their own boss, getting a say in their working conditions. They certainly can't hope to rise from a blue-collar job on the streets to a white-collar job in the Uber offices.

Then, as now, a worker was hired by the day, not by the year, and might find themselves with no work the next day, depending on the whim of a factory owner or an algorithm.

As Merchant writes: robots aren't coming for your job; bosses are. The dream of a "dark factory," a "fully automated" Tesla production line, is the dream of a boss who doesn't have to answer to workers, who can press a button and manifest their will, without negotiating with mere workers. The point isn't just to reduce the wage-bill for a finished good – it's to reduce the "friction" of having to care about others and take their needs into account.

Luddites are not – and have never been – anti-technology. Rather, they are pro-human, and see production as a means to an end: broadly shared prosperity. The automation project says it's about replacing humans with machines, but over and over again – in machine learning, in "contactless" delivery, in on-demand workforces – the goal is to turn humans into machines.

There is blood in the machine, Merchant tells us, whether its humans being torn apart by a machine, or humans being transformed into machines.

Brian and I are having a joint book-launch tomorrow night (Sept 27) at Chevalier's Books in Los Angeles for my new book The Internet Con and his new book, Blood in the Machine:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/the-internet-con-by-cory-doctorow-blood-in-the-machine-by-brian-merchant-tickets-696349940417

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/09/26/enochs-hammer/#thats-fronkonsteen

#pluralistic#books#reviews#brian merchant#luddism#automation#history#gift guide#steampunk#makers#tina#inevitablism#reverse centaurs#amazon#arise

548 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ping Jinchuan: A 19th century Sci-fi Shenmo Novel

Like all popular novels, when something sets a trend, many imitators follow suit, until the formula becomes its own genre of sorts.

FSYY is one such genre setter. Specifically, the "Battle of Arts" (斗法) formula, where immortals and deities are added into a historical event——usually a war, but it can also be something like Admiral Zheng He's voyage——and proceed to use said setting as an excuse to battle it out using spells, magical treasures, and formations.

It's such an enduring formula, late Qing novels were still following it. And because it's the 19th century, western technology and ideas were entering China and making their way into popular culture.

My first exposure to the results comes from Legends of the Eight Immortal Attaining the Dao (八仙得道传), where the narrator occasionally interrupts the story and goes: "Electricity-based technology is totally the work of Mother Lightning, guys!"

Why am I telling you all these random facts? Because Ping Jinchuan ("Quelling the Golden Stream") is that, but turned up to eleven.

Technically, FSYY is set in Shang dynasty China. Technically, Ping Jinchuan is an obscure 1899 novel about the quelling of rebellions in Qinghai and Tibet during the 18th century by the historical general Nian Gengyao.

However, considering that FSYY has 11th century BCE gunpowder weapons, and...the entirety of Ping Jinchuan, I really doubt the claim of the latter novel's author that the story is based on the eye witness accounts of his ancestor, who worked as an advisor under Nian Gengyao.

But if you insist, here's a rough summary of the historical background: the first war Nian fought in Tibet happened during the reign of Kangxi, because the Dzungar Khanate invaded Tibet.

The second rebellion Nian quelled in Qinghai, during the reign of Yongzheng, was started by Lobzang Tendzin. He fought against the Dzungar Khanate with the help of Qing army, but rebelled together with local chiefdoms and Mongol leaders when he was not granted the rulership of Tibet afterwards.

(Confusingly enough, during the reign of Qianlong, there were also 2 other rebellions by the chieftains of "Greater and Lesser Jinchuan" in northwestern Sichuan, which might be where the novel's name came from.)

Naturally, the novel proceeds to tell a "Battle of Arts" story, about Tibetan Buddhist monks, Muslims, Daoist sages, and the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church duking it out with typical Shenmo novel treasures...and 19th century magitek.

There is potential for some serious analysis about Qing military expansion, violence on the frontiers, how foreign religions and people are perceived through the framework of popular fiction, etc. But honestly, after seeing the above summary, are you really here for *that*?

I'm not, because I don't know nearly enough about the historical context, and the entire premise is ridiculous enough to defy any attempt at taking it seriously——unless the attempts are ironic.

Case In Point

The novel starts off pretty tame: Lobzang Tendzin, "King of Jinchuan", wanted to send his own Dalai Lama candidate to Tibet after the previous Dalai's death, as part of a power ploy to make himself the de facto ruler of Tibet.

He allied himself with Galdan, the Dzungar ruler, to force the Tibetans to accept his candidate at gunpoint——literally.

Their firearms and cannons got stopped by a Lama named Ding Chan, who used his meditation power to summon divine warriors and fend off the first wave of attack.

However, his meditation was broken by the plight of Jinchuan soldiers disguised as female refugees, and later, Galdan assassinated him in his sleep with a firing squad during a treaty talk organized by the Qing.

Emperor Yongzheng was not happy and sent Nian Gengyao and Yue Zhongqi to quell the rebellion. Also, Nian is actually the Heavenly Dog Star incarnate, who learned martial arts, classics, war strategy, and all sorts of neat stuff in his youth from a poor Buddhist monk.

Later, said monk and Yue's master sent a bunch of their disciples to Nian and Yue as reinforcement, before the battle began.

Then, in Chapter 4, Nan Guotai was introduced as the fictional son of the historical Belgian missionary, Ferdinand Verbiest. Nicknamed "Little Lu Ban", he was well-versed in the arts of western machinery and firearms, and the first sign of the story going completely off the rails.

The first "Battle of the Arts" round was pretty standard——Five Phase Formation, magical breaths, treasures. But Nan was ordered to make 15 "mechanical carts" that could produce flames, in conjunction with a field of landmines, to assist in the breaking of the Five Phase Formation.

Despite the similarity, they aren't tanks, but more like...trapped cargo trailers/RVs. Basically, they had "doors and windows" with built-in mechanisms that only allowed entry into the carts and could not be opened from the inside, and once the enemies were trapped, the carts became giant incinerators.

After losing the first round, the King of Jinchuan put up a recruitment poster for "talented followers of the Three Religions"...except the Three Religions weren't Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism, but Islam, Buddhism, and Daoism, since the story is set in Qinghai, where there was a notable population of Hui people (Chinese Muslims).

After seeing the poster, Galdan's wife decided to seek help from her own master, the Patriarch of the Snowy Mountains. He is a Muslim sage with 12 powerful disciples...who all wielded typical Daoist treasures.

They all got overshadowed by the next round of Steampunk Shenmo Battle, though, when an unrelated Daoist showed up with his trump card: "Strong Water", a.k.a. magical hydrochloric acid.

The magical HCI was then put into giant glass syringes and fired at Nian's troops, resulting in significant casualties. To bypass the HCI syringe cannons, Nan unrevealed his latest invention: the Skysoar Orb, a.k.a. hot air balloon.

The Qing troops then mounted firearms and cannons onto the air balloon, flew it above Galdan's camp to a height where the HCI syringes couldn't reach, and started shooting. However, they were all mortals, and got decimated when the enemy immortals flew up to take control of the balloons, forcing an emergency landing via needles.

After that, the hot air balloon was manned entirely by immortals, until Galdan covered his camp in a mesh of barbed wires, blocking the aerial fire but also making it impossible for him to use his own HCI syringes.

Then a little 13 years old immortal, Gengsheng the Acolyte, joined the Qing army, who's the reincarnation of the Lama executed by Galdan's firing squad. Abandoned at birth and adopted by a Daoist master, he was able to fly on clouds since he was 8-9 years old, which he used to travel to Europe.

While he was there, a Swedish sage gifted him a powerful treasure——the Electricity Whip, which can be used to electrocute people to death...but also magically heal injuries with its currents.

I have trouble visualizing the thing. Is it a literal whip of lightning arcs (since it's described as being able to turn into a white beam), a taser, an electric cattle prod, a plasma whip, or the unholy lovechild of all the above plus a tesla coil?

Hilariously, the Electricity Whip treasure of the Nikola Tesla Sect (/sarcasm) stopped working when exposed to "dirty stuff" such as a woman's magical handkerchief. Classic folk magic style.

After a bunch of boring fighting sequences, 6 of the 12 disciples of the Patriarch decided to get the big formations out, which were broken by buckets of pig blood.

…Yeah, that's pretty much the extent of the author's understanding of Hui customs and Islam. (sigh) The surviving disciples went to get the Patriarch for help, who casted an AOE spell of poisonous smoke, water and fire to block the Qing troops' path...

Annnnnd Nan to the rescue again! With the help of Nian Gengyao's monk master, he built the Earth Travel Cart: a magitek subway train shaped like a pangolin, able to carry a hundred people and move a hundred Li per hour. It didn't need rails, you just dug a hole in the ground, put the train in, and it started tunneling through the earth on its own.

The entire army used 500 of these magical subway trains to bypass the Patriarch's AOE spell coverage, forcing them to retreat to their home base, Tianshan (Heavenly Mountain). Which is a real mountain range in central Asia and Xinjiang province, and going there from Qinghai is plausible. Kinda.

I'm still skeptical about the novel's claim that the path through Tianshan is the only path leading into Jinchuan proper, but whatever.

The Patriarch put his most powerful formation on said mountain pass——the Ice Freeze Formation, which will insta-freeze immortals, mortals, and flying birds alike when they step in range.

Then comes the craziest part of the entire novel. Honestly, everything after this chapter is pretty boring and formulaic, which makes it the perfect note for this article to end on.

Nan suddenly revealed that the current Roman Pope is the grandson of Matteo Ricci, who's the mentor of Nan's dad, and took his hot air balloon to Rome to get reinforcement. To no one's surprise, the Pope's treasure is a cross.

The Pope agreed and took his 12 disciples——supposedly because it's the same as the number of apostles——to the snowy mountain.

He gave a cross and a white candle to each of his disciples; they walked straight into the Ice Formation and broke it by holding the two holy objects up in the air, while loudly chanting (a highly localized translation of) "Hail Mary!"

After making his grand entrance, the Pope neutralized the Patriarch's spell attacks and turned his last disciples' army of soldiers back into their true forms——a bunch of farm animals.

He then told the disciples that as the Roman Pope, he had authority over "Russia, England, France, Netherlands" and all the European nations, and he'd leave the Patriarch to mind his own business if he surrendered and stopped interfering in the war.

Three of the four examples he gave aren't even Catholic, but maybe the Protestant Reformation just never happened in this novel's 18th century world because Pope Magic.

The Patriarch accepted the cease-fire treaty, went back to teach his religion to the population of northwestern China, and that's pretty much it. His last female disciple (Galdan's wife) got her troops' firearms neutralized by the Pope's cross, taken prisoner, and executed by Nian.

After revealing that the Qing immortals' power also came from the Grace of Our Lord and Savior, and that was why westerners couldn't use spells (but could make electricity-based treasures?), the Pope flew back to Rome on Nan's air balloon, exiting the novel once and for all.

Which is a pity, because in the second half of the novel, one of the defeated foes escaped to (Ottoman?) Turkey to beg their king for reinforcement, and the Russian Tsar agreed to help the Jinchuan troops to make his French wife happy. I want my Papal 13 vs. Russian Orthodox Bishops Shenmo battle, dammit!

Food for thought: if the Pope was Matteo Ricci's grandson, and Matteo Ricci was also a mentor of Ferdinand Verbiest, Nan's dad (historically, Ricci died 13 years before Verbiest was even born)...

...Is this a timeline where the Jesuits won the Rites Controversy, Ricci cultivated himself into the first Catholic immortal, and ushered in the age of Syncretic Daoist-Catholic Steampunk?

#chinese folklore#chinese literature#steampunk#chinese novels#catholic church#daoism#buddhism#chinese history#islam#matteo ricci#jesuits#qing dynasty#investiture of the gods#fengshen yanyi#how do you even tag this novel#the sheer unhinged fun of it all

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History of Cyberpunk

Or why every other SciFi Genre is called [something]punk

You know what? Let's do this. Because I have seen the discussion on whether or not Solarpunk is "punk" over the last few days and... people really gotta learn their history.

The first time a genre took the "punk" name was Cyberpunk. And for context we gotta talk a bit about the history of the Cyberpunk genre.

While some books that we in hindsight call "Cyberpunk" were released as early as the 1960s, the start of Cyberpunk as a genre got its start in the late 70s and early 80s.

The term was invented by Bruce Bethke, who published a short story in 1983 with the name "Cyberpunk". His idea was to juxtapose the term "punk" for both the mentality and the punk protagonists in his short story with the term cyber, short for the cybernetics they were wearing. And while the cybernetics have become a main stay in the genre, the punk attitudes are not always carried through...

Well, the title Bethke invented stuck, though. When 1984 Neuromancer was published, one of the most influencial works in the early days of the genre, he called it "a Cyberpunk novel" in the marketing. And from there... Well, the genre was suddenly named like that.

The 80s were definitely the decade that had the most influence on the genre, given that a lot of the big novels and graphic novels of the genre were released here.

A big influence was, no doubt, that 1982 the Blade Runner movie had released and had inspired quite a few writers and artists. (And yes, this makes Blade Runner a movie that released not only before the term Cyberpunk was coined, but also before the genre had a chance to define itself.)

Given that the genre was defined in the 80s, there are a lot of 80s anxiety kept within it about the rise of the Japanese economy, that are these days rarely questioned within the western Cyberpunk movement.

When the genre was coined and developed, Japan was the fastest growing economy in the world, being so influencial that they got to buy out several things in America. Something that kinda jerked white people in the US a lot. This is, why Cyberpunk originally depicted not only a capitalist hellscape - but specifically a capitalist hellscape were everything was bought out by Japanese companies, with many of those early antagonists being Japanese companies. And yeah... there was a lot of both anti-japanese racism, but also cultural appropriation of Japanese things in early Cyberpunk, at time surviving to this day. (But that is a story for another day.)

The general sense that Western Cyberpunk had, was always the idea of: We have a capitalist hellscape where the world is slowly dying and people are exploited with no end, while we have those kinda punky protagonists, who stand outside of the society and try to work against it. This being where the punk comes from.

Now, I could talk for length about how a lot of that punky attitude has been lost in more modern Cyberpunk media, but that, too, is a story for another day.

So, let me just talk about what happened then.

The term Cyberpunk really is darn catchy, right? So just when that name took hold, writer K.W. Jeter retroactively called his 1979 novel Morlock Night "steampunk". And guess what: This stuck, too. Though while the 80s Cyberpunk still stuck to the punk attitude, a lot of Steampunk did not. While for certain there is quite a bit of Steampunk that has kinda punky characters go against the quasi Victorian society of steampunk books (something most common in the air pirate novels I have read), a lot of other stories are more focused on a general sense of adventure.

But never the less... The genre names stuck and gave a nice baseline for naming other genre. We got Dieselpunk, Atompunk, Nanopunk, Arcanepunk, Dustpunk, Silkpunk and of course also Solarpunk and Lunarpunk.

And for the most part... The "punk" names mostly communicate: "It is SciFi with this kinda aesthetic/twist going on". Which is just how it turned out.

Funnily enough Solarpunk is for once a genre that brings back the punk, as it tends to include a lot of the ideals aspired to by the Punk counter culture of the 1970s: Anarchism, anti-capitalism, anti-consumerism, anti-classism, anti-racism, anti-colonialism and so on. Though other than with Cyberpunk and the real world punk movement, Solarpunk for the most part imagines a place, where those things are culture instead of counter culture.

I personally find it kinda sad, how for the most part Cyberpunk kinda lost a lot of the counter-cultural, revolutionary mindset. And how fucking defeatist the genre often is.

But again, it is a story for another day. Just as the story of Japanese Cyberpunk is.

#cyberpunk#solarpunk#steampunk#cyberpunk history#western cyberpunk#science fiction#scifi#william gibson#neuromancer#genre history#punk

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Nemo, Freedom Fighter

There's a lot of historical and cultural significance in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea which is not widely known by modern audiences. Here some some facts I find very interesting:

-> In Verne’s original character notes, he was going to be a POLISH noble whose family was killed by Russians.

Verne’s publisher argued with him about that for a long time because of his large Russian fanbase. Verne reluctantly gave in, but eventually changed Nemo’s backstory to that of an Indian Prince whose family was killed by the British.

With that in mind, that makes the Soviet miniseries more interesting: A Polish revolutionary is actually mentioned by Captain Nemo in the second episode. Vladislav Dvorzhetsky, the actor portraying Nemo, was actually half-Polish himself!

-> Captain Nemo was written as a foil to Confederate Navy Captain Raphael Semmes.

Captain Raphael Semmes had portraits of General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate President Jefferson Davis on the cabin wall of the CSS Alabama, while Captain Nemo has portraits of Abraham Lincoln and the radical abolitionist John Brown in the cabin walls of the Nautilus.

Semmes was a supporter of slavery while Captain Nemo was an abolitionist.

Raphael Semmes stated that India should never be free from British rule, while Captain Nemo was an Indian who fought to be free from British rule.

A list of more comparisons between Jules Verne's "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea" and Raphael Semmes' "Memoirs of Service Afloat During the War Between the States" can be found on Wikipedia.

Thus, in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Jules Verne was trying to point fingers at the cruelty of the British towards India, the Russians towards the Polish, AND Americans towards people of color.

There are many fascinating rabbit trails to explore in regards to Jules Verne's literary masterpiece. Here are some sources:

#jules verne#20000 leagues under the sea#captain nemo#classic literature#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#tkluts#steampunk#french literature#history#literary history#Капитан Немо#Vladislav Dvorzhetsky#20kleaguesunderthefeed#20kluts#20k leagues#civil war#civil rights#european history

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victorian ingenuity: a mahogany "reading station" crafted by Charles Hindley & Co. circa 1890. It features a double wing-back seat with an arm divider, each seat equipped with an adjustable reading stand, various compartments, drawers, and bookshelves.

Photos courtesy of Butchoff Antiques

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

An underrated type of relationship: being in cahoots with someone.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

STEELRISING — The Angel of Death

#steelrising#underrated game#a bit clunky but fun and quite interesting for history and steampunk nerds#steelrising edit#soulslike#gamingedit#videogameedit#gamingnetwork#dailygaming#mine#*gifs#*steelrisingedit

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clock made in the year 1576, known as "Barcelona great clock" (gran rellotge de Barcelona) or "clock of the Flemish" (rellotge dels flamencs).

This is the clock that marked the official time in Barcelona (Catalonia) from the top of its cathedral's bell tower between the years 1577 and 1864. It was made by Flemish clockmakers, and it's probably the biggest clock of its kind in the world.

Barcelona's cathedral got its first large mechanical clock in the year 1396. It was substituted 4 times before the clock on this post, which was the 5th. In 1864, this clock was taken down and a 6th one was installed, which is still in use nowadays.

Source: Museu d'Història de Barcelona.

#barcelona#catalunya#història#clock#clockwork#catalonia#historical#history#1500s#16th century#europe#early modern#steampunk#artifact

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday doodle 8/11/24

Pitched this idea last week and got some positive responses so here’s one part of my new project. You know where it’s a collection of sketches and letters set in a steampunk alternate history world where some guy is traveling through Deseret, drawing cool stuff he sees and trying to convince his friend back home that he’s not going to get murdered by the Mormons.

Letter transcript:

My Dear Friend Victor,

As my previous letter was sent from a rather dubious, yet reliable location, I anticipate that this letter shall outpace it and reach you first. As such, I shall briefly recount its contents.

First you must know that I am well and relatively unscathed. When I arrived in St George I believed all my rough traveling behind me and it would be airships all the way to Salt Lake. Hardly thirty minutes in the sky a band of Confederate Holdouts revealed themselves and took control of the ship, intending to sail it back to one of their secret enclaves in the South to aid in their misguided “war effort”. Fortunately they were foiled by a Deseret Federal Marshal (Lt. Whitterby of the Danite division) who subdued the rebels and orchestrated an emergency landing in the town of Kanab, a good distance east of St George. As I said, the exact details are in my other letter which I sent from the Kenab post office. The postmaster there seemed old as Methusala, leading to my doubt on the speediness of that letter’s delivery. This letter I shall send from the St George post office which is of a more modern fashion.

But I must tell you of the mechanical wonder I encountered in Kanab! After the ordeal the band of Johnny Rebs were locked securely in the Kanab town hall (the town is too small for a proper jailhouse). The other passengers and I were given a little rest and refreshment in the same building (the town is also too small for a hotel). I took this time to write my previous (or possibly forthcoming) letter and send it off. After a while we heard the sound of twin airships approaching. These were the Thunderbird and the Tiancum, which Lt. Whitterby called for. One to return us to St George and the other to take away the villains. He asked us to remain where we were, that we might witness the official arrest and then sign documents witnessing that the correct persons were taken into custody (I swear these Mormons are obsessed with everything being witnessed!)

When the Deseret Marshals marched in they were accompanied by the most peculiar automatons. I was able to make sketches, which I have included. There were four of these contraptions, one for each of the Confederates. They each bore the stern face sculpted from copper or brass, I could not tell. I was told that they bore the face of that wiley old General O.P. Rockwell, who gave our General Sherman and all those Union boys such a rough time in the siege of Echo Canyon.

Each Rockwell was directed by its operator to stand directly behind the hijackers and hold the criminals' hands behind their backs, like a pair of handcuffs. Just as I was wondering why entire automatons were called for what a mere pair of handcuffs could do, one of the scoundrels broke free and made a break for it, rushing as though he would leap out of the window to freedom! But then the Rockwell machine did a strange thing. One of its hands dropped, as if it was on a hinge and a small device extended from the open wrist. With a pop, it shot a tiny harpoon attached with a thin wire at the man. I wondered at this, as the harpoon and wire were both far too small to catch a fish, let alone a desperate criminal. But when the harpoon struck him there came a sound like a deep angry buzzing and the man became stiff as a board and toppled over as if dead!

The foiled escapee was looked over and determined to still be alive, (though with quite a lot less fight in him) and was bound in the same manner as the rest. In asking Lt Whitterby what had just transpired, he told me that the machines “Rockwell Automatons” where based on a design currently being used in both London and Chicago ment to assist local law enforcement in apprehending and holding dangerous criminals. When I brought up how easily the man had been felled, the Lieutenant told me that that particular innovation was of pure Deseret origin. In the Chicago models a simple gun is concealed in the wrist, and the London model is given a club. Both were determined to be far too brutal for the liking of the Deseret Marshals, so an alternative device was created. This deceive, I was told, delivers a small electrical charge to the target, not powerful enough to kill, but just enough to temporarily confuse the nervous system and render the target harmless.

But look! I have been writing and sketching aboard the Thunderbird so long that we have been returned to St George so that I might continue my journey to Salt Lake! I must finish this letter and mail it while I can. As always I shall write to you whenever I am able.

Your friend,

Jacob K. Steinsworth

P.S. Please thank your wife, Isabel for her insistence that I carry a pocket Bible on this trip. It proved quite useful during the ordeal with those Confederate hijackers. Again, the full details are in the other letter.

#my art#my writing#sunday doodle#tumblrstake#lds#mormon#lds church#just mormon things#ldschurch#mormon church#mormon steampunk#steampunk#alternate history#deseret alphabet#Deseret#deseret punk

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey there @victoriocity fans! HIGH VAULTAGE was released yesterday, and there are a limited number of EXCLUSIVE signed special editions available from Goldsboro Books.

Only 2000 have been printed, these are collectable first editions from a specialist independent bookseller, and they are GORGEOUS. Goldsboro also ship internationally, so anyone can get their mitts on this!

#High Vaultage#Chris and Jen Sugden#Victoriocity#Special Edition Books#Steampunk#Teslapunk#Alternate History

48 notes

·

View notes