#Haitian revolution

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This is how Haitians won their freedom: no pleading, no marching, no begging, no signing petitions, no holding up signs, no chanting, no sit-ins—just decisive action! 🇭🇹

PSA: Dismissing or minimizing the Haitian Revolution because of Haiti’s current struggles is a cowardly and shortsighted view. True liberation has never come without sacrifice, and freedom is never comfortable. The brave men and women who fought for Haiti’s independence knew the price of defying colonial powers, yet they chose dignity over submission. Haiti’s current struggles are not the result of its revolution but of relentless foreign interference, economic sabotage, and imperialist retaliation meant to punish the first free Black nation. To suggest they should have remained in chains to avoid hardship is the mindset of the weak.

The Haitian Revolution was not just for Haiti—it was a beacon for the entire African world. It shattered the illusion of white supremacy, proving that enslaved Africans could rise, fight, and win. It ignited a butterfly effect, inspiring Black resistance movements, abolitionist struggles, and anti-colonial uprisings across the globe. Haiti stood as a symbol of Pan-African defiance, and the same forces that sought to destroy it then continue to undermine Black progress today. If you measure success by comfort rather than liberation, you are still mentally enslaved.

#black people#black#black history#black tumblr#blacktumblr#pan africanism#black conscious#africa#black power#black empowering#haitian revolution#Haitians#haiti#black first#b1

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tennis star, Naomi Osaka is a real one for this epic moment. Naomi, who is Haitian & Japanese, calls for Reparations for Haiti from France. If Naomi wasn't already one of my favorite tennis players and one of my favorite people, she'd sure be my favorite now! 👍🏽✊🏽🙏🏽🖤 This is not an act of "Wokeism" THIS is pure pride!

#naomi osaka#haiti#1804#free haiti#reparations#haitian revolution#france#black kings#black queens#kings and queens#black gods#gods#black men#african women#africa#african#black women#black girls#black queen#afro latinas#black history#black beauty#politics#afro latinos#black teachers#black entrepreneurship#black inventors#black fashion#black love#black tumblr

527 notes

·

View notes

Text

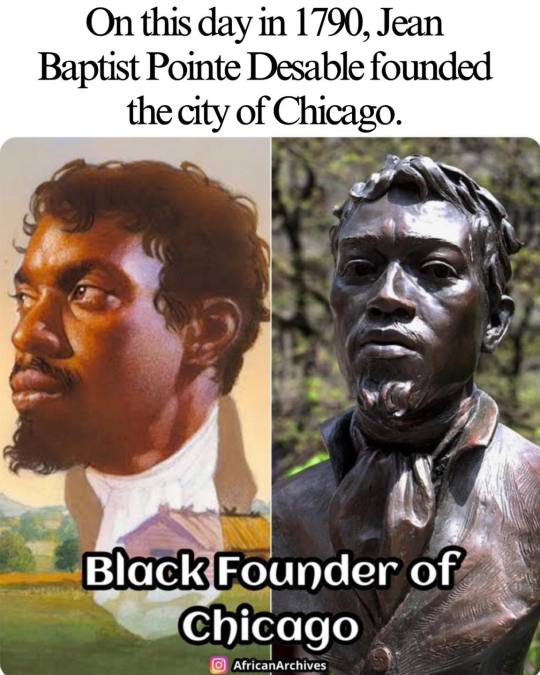

Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable was born in Saint-Domingue, Haiti (French colony) during the Haitian Revolution. At some point he settled in the part of North America that is now known as the city of Chicago and was described in historical documents as "a handsome negro" He married a Native American woman, Kitiwaha, and they had two children. In 1779, during the American Revolutionary War, he was arrested by the British on suspicion of being an American Patriot sympathizer. In the early 1780s he worked for the British lieutenant-governor of Michilimackinac on an estate at what is now the city of St. Clair, Michigan north of Detroit. In the late 1700's, Jean-Baptiste was the first person to establish an extensive and prosperous trading settlement in what would become the city of Chicago. Historic documents confirm that his property was right at the mouth of the Chicago River. Many people, however, believe that John Kinzie (a white trader) and his family were the first to settle in the area that is now known as Chicago, and it is true that the Kinzie family were Chicago's first "permanent" European settlers. But the truth is that the Kinzie family purchased their property from a French trader who had purchased it from Jean-Baptiste. He died in August 1818, and because he was a Black man, many people tried to white wash the story of Chicago's founding. But in 1912, after the Great Migration, a plaque commemorating Jean-Baptiste appeared in downtown Chicago on the site of his former home. Later in 1913, a white historian named Dr. Milo Milton Quaife also recognized Jean-Baptiste as the founder of Chicago. And as the years went by, more and more Black notables such as Carter G. Woodson and Langston Hughes began to include Jean-Baptiste in their writings as "the brownskin pioneer who founded the Windy City." In 2009, a bronze bust of Jean-Baptiste was designed and placed in Pioneer Square in Chicago along the Magnificent Mile. There is also a popular museum in Chicago named after him called the DuSable Museum of African American History.

x

#Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable#Haitian Revolution#Chicago history#founder of Chicago#black history#Native American wife#Kitiwaha#American Revolutionary War#British arrest#Michilimackinac#St. Clair Michigan#trading settlement#Chicago River#John Kinzie#European settlers#Great Migration#Carter G. Woodson#Langston Hughes#Windy City#bronze bust#Pioneer Square#Magnificent Mile#DuSable Museum#African American history

607 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incorruptible Interlude pt 3

From left to right we have:

Cecile Fatiman, a Vodou priestess who helped in sparking the Haitian Revolution.

Jean-Jacques-Regis de Cambaceres, a gay politician who was active during the Revolution.

Sophie de Condorcet, a writer and translator who hosted The Cercle Social, which aimed to promote women's rights.

Just a few examples of the wonderful progress that was made from 'this equality nonsense'. The revolution created a dizzying amount of progress in an incredibly short amount of time.

#can you spot the maxime and camille in this page?#incorruptiblecomic#frev#french revolution#bertrand barere#webcomic#comic#webtoon#history comic#historical fiction#haitian revolution#Cecile Fatiman#Jean-Jacques-Regis de Cambaceres#Sophie de Condorcet

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Women of the French Revolution (and even the Napoleonic Era) and Their Absence of Activism or Involvement in Films

Warning: I am currently dealing with a significant personal issue that I’ve already discussed in this post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765252498913165313/the-scars-of-a-toxic-past-are-starting-to-surface?source=share. I need to refocus on myself, get some rest, and think about what I need to do. I won’t be around on Tumblr or social media for a few days (at most, it could last a week or two, though I don’t really think it will).

But don’t worry about me—I’m not leaving Tumblr anytime soon. I just wanted to let you know so you don’t worry if you don’t see me and have seen this post.

I just wanted to finish this post, which I’d already started three-quarters of the way through.

One aspect that frustrates me in film portrayals (a significant majority, around 95%) is the way women of the Revolution or even the Napoleonic era are depicted. Generally, they are shown as either "too gentle" (if you know what I mean), merely supporting their husbands or partners in a purely romantic way. Just look at Lucile Desmoulins—she is depicted as a devoted lover in most films but passive and with little to say about politics.

Yet there’s so much to discuss regarding women during this revolutionary period. Why don’t we see mention of women's clubs in films? There were over 50 in France between 1789 and 1793. Why not mention Etta Palm d’Alders, one of the founders of the Société Patriotique et de Bienfaisance des Amies de la Vérité, who fought for the right to divorce and for girls' education? Or the cahier from the women of Les Halles, requesting that wine not be taxed in Paris?

Only once have I seen Louise Reine Audu mentioned in a film (the excellent Un peuple et son Roi), a Parisian market woman who played a leading role in the Revolution. She led the "dames des halles" and on October 5, 1789, led a procession from Paris to Versailles in this famous historical event. She was imprisoned in September 1790, amnestied a year later through the intervention of Paris mayor Pétion, and later participated in the storming of the Tuileries on August 10, 1792. Théroigne de Méricourt appears occasionally as a feminist, but her mission is often distorted. She was not a Girondin, as some claim, but a proponent of reconciliation between the Montagnards and the Girondins, believing women had a key role in this process (though she did align with Brissot on the war question). She was a hands-on revolutionary, supporting the founding of societies with Charles Gilbert-Romme and demanding the right to bear arms in her Amazon attire.

Why is there no mention in films of Pauline Léon and Claire Lacombe, two well-known women of the era? Pauline Léon was more than just a fervent supporter of Théophile Leclerc, a prominent ultra-revolutionary of the "Enragés." She was the eldest daughter of chocolatier parents, her father a philosopher whom she described as very brilliant. She was highly active in popular societies. Her mother and a neighbor joined her in protesting the king’s flight and at the Champ-de-Mars protest in July 1791, where she reportedly defended a friend against a National Guard soldier. Along with other women (and 300 signatures, including her mother’s), she petitioned for women’s rights. She participated in the August 10 uprising, attacked Dumouriez in a session of the Société fraternelle des patriotes des deux sexes, demanded the King’s execution, and called for nobles to be banned from the army at the Jacobin Club, in the name of revolutionary women. She joined her husband Leclerc in Aisne where he was stationed (see @anotherhumaninthisworld’s excellent post on Pauline Léon). Claire Lacombe was just as prominent at the time and shared her political views. She was one of those women, like Théroigne de Méricourt, who advocated taking up arms to fight the tyrant. She participated in the storming of the Tuileries in 1792 and received a civic crown, like Louise Reine Audu and Théroigne de Méricourt. She was active at the Jacobin Club before becoming secretary, then president of the Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires (Society of Revolutionary Republican Women). Contrary to popular belief, there’s no evidence she co-founded this society (confirmed by historian Godineau). Lacombe demanded the trial of Marie Antoinette, stricter measures against suspects, prosecution of Girondins by the Revolutionary Tribunal, and the application of the Constitution. She also advocated for greater social rights, as expressed in the Enragés petition, which would later be adopted by the Exagérés, who were less suspicious of delegated power and saw a role beyond the revolutionary sections.

Olympe de Gouges did not call for women to bear arms; in her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, addressed to the Queen after the royal family’s attempted escape, she demanded gender equality. She famously said, "A woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum," and denounced the monarchy when Louis XVI's betrayal became undeniable, although she sought clemency for him and remained a royalist. She could be both a patriot and a moderate (in the conservative sense; moderation then didn’t necessarily imply clemency but rather conservative views on certain matters).

Why Are Figures Like Manon Roland Hardly Mentioned in These Films?

In most films, Manon Roland is barely mentioned, or perhaps given a brief appearance, despite being a staunch republican from the start who worked toward the fall of the King and was more than just a supporter of her husband, Roland. She hosted a salon where political ideas were exchanged and was among those who contributed to the monarchy's downfall. Of course, she was one of those courageous women who, while brave, did not advocate for women’s rights. It’s essential to note that just because some women fought in the Revolution or displayed remarkable courage doesn’t mean they necessarily advocated for greater rights for women (even Olympe de Gouges, as I mentioned earlier, had her limits on gender equality, as she did not demand the right for women to bear arms).

Speaking of feminism, films could also spotlight Sophie de Grouchy, the wife and influence behind Condorcet, one of the few deputies (along with Charles Gilbert-Romme, Guyomar, Charlier, and others) who openly supported political and civic rights for women. Without her, many of Condorcet’s posthumous works wouldn’t have seen the light of day; she even encouraged him to write Esquilles and received several pages to publish, which she did. Like many women, she hosted a salon for political discussion, making her a true political thinker.

Then there’s Rosalie Jullien, a highly cultured woman and wife of Marc-Antoine Jullien, whose sons were fervent revolutionaries. She played an essential role during the Revolution, actively involving herself in public affairs, attending National Assembly sessions, staying informed of political debates and intrigues, and even sending her maid Marion to gather information on the streets. Rosalie’s courage is evident in her steadfastness, as she claimed she would "stay at her post" despite the upheaval, loyal to her patriotic and revolutionary ideals. Her letters offer invaluable insights into the Revolution. She often discussed public affairs with prominent revolutionaries like the Robespierre siblings and influential figures like Barère.

Lucile Desmoulins is another figure. She was not just the devoted lover often depicted in films; she was a fervent supporter of the French Revolution. From a young age, her journal reveals her anti-monarchist sentiments (no wonder she and Camille Desmoulins, who shared her ideals, were such a united couple). She favored the King’s execution without delay and wholeheartedly supported Camille in his publication, Le Vieux Cordelier. When Guillaume Brune urged Camille to tone down his criticism of the Year II government, Lucile famously responded, “Let him be, Brune. He must save his country; let him fulfill his mission.” She also corresponded with Fréron on the political situation, proving herself an indispensable ally to Camille. Lucile left a journal, providing historical evidence that counters the infantilization of revolutionary women. Sadly, we lack personal journals from figures like Éléonore Duplay, Sophie Momoro, or Claire Lacombe, which has allowed detractors to argue (incorrectly) that these women were entirely under others' influence.

Additionally, there were women who supported Marat, like his sister Albertine Marat and his "wife"Simone Evrard, without whom he might not have been as effective. They were politically active throughout their lives, regularly attending political clubs and sharing their political views. Simone Evrard, who inspired much admiration, was deeply committed to Marat’s work. Marat had promised her marriage, and she was warmly received by his family. She cared for Marat, hiding him in the cellar to protect him from La Fayette’s soldiers. At age 28, Simone played a vital role in Marat’s life, both as a partner and a moral supporter. At this time, Marat, who was 20 years her senior, faced increasing political isolation; his radical views and staunch opposition to the newly established constitutional monarchy had distanced him from many revolutionaries.

Despite the circumstances, Simone actively supported Marat, managing his publications. With an inheritance from her late half-sister Philiberte, Simone financed Marat’s newspaper in 1792, setting up a press in the Cordeliers cloister to ensure the continued publication of Marat’s revolutionary pamphlets. Although Marat also sought public funds, such as from minister Jean-Marie Roland, it was mainly Simone’s resources that sustained L’Ami du Peuple. Simone and Marat also planned to publish political works, including Chains of Slavery and a collection of Marat’s writings. After Marat’s assassination in July 1793, Simone continued these projects, becoming the guardian of his political legacy. Thanks to her support, Marat maintained his influence, continuing his revolutionary struggle and exposing the “political machination” he opposed.

Simone’s home on Rue des Cordeliers also served as an annex for Marat’s printing press. This setup combined their personal life with professional activities, incorporating security measures to protect Marat. Simone, her sister Catherine, and their doorkeeper, Marie-Barbe Aubain, collaborated in these efforts, overseeing the workspace and its protection.

On July 13, 1793, Jean-Paul Marat was assassinated by Charlotte Corday. Simone Evrard was present and immediately attempted to help Marat and make sure that Charlotte Corday was arrested . She provided precise details about the circumstances of the assassination, contributing significantly to the judicial file that would lead to Corday’s condemnation.

After Marat’s death, Simone was widely recognized as his companion by various revolutionaries and orators who praised her dignity, and she was introduced to the National Convention by Robespierre on August 8, 1793 when she make a speech against Theophile Leclerc,Jacques Roux, Carra, Ducos,Dulaure, Pétion... Together with Albertine Marat (who also left written speeches from this period), Simone took on the work of preserving and publishing Marat’s political writings. Her commitment to this cause led to new arrests after Robespierre's fall, exposing the continued hostility of factions opposed to Marat’s supporters, even after his death.

Moreover, Jean-Paul Marat benefited from the support of several women of the Revolution, and he would not have been as effective without them.

The Duplay sisters were much more politically active than films usually portray. Most films misleadingly present them as mere groupies (considering that their father is often incorrectly shown as a simple “yes-man” in these same, often misogynistic, films, it's no surprise the treatment of women is worse).

Élisabeth Le Bas, accompanied her husband Philippe Le Bas on a mission to Alsace, attended political sessions, and bravely resisted prison guards who urged her to marry Thermidorians, expressing her anger with great resolve. She kept her husband’s name, preserving the revolutionary legacy through her testimonies and memoirs. Similarly, Éléonore Duplay, Robespierre’s possible fiancée, voluntarily confined herself to care for her sister, suffered an arrest warrant, and endured multiple prison transfers. Despite this, they remained politically active, staying close to figures in the Babouvist movement, including Buonarroti, with whom Él��onore appeared especially close, based on references in his letters.

Henriette Le Bas, Philippe Le Bas's sister, also deserves more recognition. She remained loyal to Élisabeth and her family through difficult times, even accompanying Philippe, Saint-Just, and Élisabeth on a mission to Alsace. She was briefly engaged to Saint-Just before the engagement was quickly broken off, later marrying Claude Cattan. Together with Éléonore, she preserved Élisabeth’s belongings after her arrest. Despite her family’s misfortunes—including the detention of her father—Henriette herself was surprisingly not arrested. Could this be another coincidence when it came to the wives and sisters of revolutionaries, or perhaps I missed part of her story?

Charlotte Robespierre, too, merits more focus. She held her own political convictions, sometimes clashing with those of her brothers (perhaps often, considering her political circle was at odds with their stances). She lived independently, never marrying, and even accompanied her brother Augustin on a mission for the Convention. Tragically, she was never able to reconcile with her brothers during their lifetimes. For a long time, I believed that Charlotte’s actions—renouncing her brothers to the Thermidorians after her arrest, trying to leverage contacts to escape her predicament, accepting a pension from Bonaparte, and later a stipend under Louis XVIII—were all a matter of survival, given how difficult life was for a single woman then. I saw no shame in that (and I still don’t). The only aspect I faulted her for was embellishing reality in her memoirs, which contain some disputable claims. But I recently came across a post by @saintejustitude on Charlotte Robespierre, and honestly, it’s one of the best (and most well-informed) portrayals of her.

As for the the hébertists womens , films could cover Sophie Momoro more thoroughly, as she played the role of the Goddess of Reason in her husband’s de-Christianization campaigns, managed his workshop and printing presses in his absence accompanying Momoro on a mission on Vendée. Momoro expressed his wife's political opinion on the situation in a letter. She also drafted an appeal for assistance to the Convention in her husband’s characteristic style.

Marie Françoise Goupil, Hébert’s wife, is likewise only shown as a victim (which, of course, she was—a victim of a sham trial and an unjust execution, like Lucile Desmoulins). However, there was more to her story. Here’s an excerpt from a letter she wrote to her husband’s sister in the summer of 1792 that reveals her strong political convictions:

« You are very worried about the dangers of the fatherland. They are imminent, we cannot hide them: we are betrayed by the court, by the leaders of the armies, by a large part of the members of the assembly; many people despair; but I am far from doing so, the people are the only ones who made the revolution. It alone will support her because it alone is worthy of it. There are still incorruptible members in the assembly, who will not fear to tell it that its salvation is in their hands, then the people, so great, will still be so in their just revenge, the longer they delay in striking the more it learns to know its enemies and their number, the more, according to me, its blows will only strike with certainty and only fall on the guilty, do not be worried about the fate of my worthy husband. He and I would be sorry if the people were enslaved to survive the liberty of their fatherland, I would be inconsolable if the child I am carrying only saw the light of day with the eyes of a slave, then I would prefer to see it perish with me ».

There is also Marie Angélique Lequesne, who played a notable role while married to Ronsin (and would go on to have an important role during the Napoleonic era, which we’ll revisit later). Here’s an excerpt from Memoirs, 1760-1820 by Jean-Balthazar de Bonardi du Ménil (to be approached with caution): “Marie-Angélique Lequesne was caught up in the measures taken against the Hébertists and imprisoned on the 1st of Germinal at the Maison d'Arrêt des Anglaises, frequently engaging with ultra-revolutionary circles both before and after Ronsin’s death, even dressing as an Amazon to congratulate the Directory on a victory.” According to Généanet (to be taken with even more caution), she may have served as a canteen worker during the campaign of 1792.

On the Babouvist side, we can mention Marie Anne Babeuf, one of Gracchus Babeuf’s closest collaborators. Marie Anne was among her husband's staunchest political supporters. She printed his newspaper for a long time, and her activism led to her two-day arrest in February 1795. When her husband was arrested while she was pregnant, she made every effort possible to secure his release and never gave up on him. She walked from Paris to Vendôme to attend his trial, witnessing the proceeding that would sentence him to death. A few months after Gracchus Babeuf’s execution, she gave birth to their last son, Caius. Félix Lepeletier became a protector of the family (and apparently, Turreau also helped, supposedly adopting Camille Babeuf—one of his very few positive acts). Marie Anne supported her children through various small jobs, including as a market vendor, while never giving up her activism and remaining as combative as ever. (There’s more to her story during the Napoleonic era as well).

We must not forget the role of active women in the insurrections of Year III, against the Assembly, which had taken a more conservative turn by then. Here’s historian Mathilde Larrère’s description of their actions: “In April and May 1795, it was these women who took to the streets, beating drums across the city, mocking law enforcement, entering shops, cafes, and homes to call for revolt. In retaliation, the Assembly decreed that women were no longer allowed to attend Assembly sessions and expelled the knitters by force. Days later, a decree banned them from attending any assemblies and from gathering in groups of more than five in the streets.”

There were also women who fought as soldiers during the French Revolution, such as Marie-Thérèse Figueur, known as “Madame Sans-Gêne.” The Fernig sisters, aged 22 and 17, threw themselves into battle against Austrian soldiers, earning a reputation for their combat prowess and later becoming aides-de-camp to Dumouriez. Other fighting women included the gunners Pélagie Dulière and Catherine Pochetat.

In the overseas departments, there was Flore Bois Gaillard, a former slave who became a leader of the “Brigands” revolt on the island of Saint Lucia during the French Revolution. This group, composed of former slaves, French revolutionaries, soldiers, and English deserters, was determined to fight against English regiments using guerrilla tactics. The group won a notable victory, the Battle of Rabot in 1795, with the assistance of Governor Victor Hugues and, according to some accounts, with support from Louis Delgrès and Pelage.

On the island of Saint-Domingue, which would later become Haiti, Cécile Fatiman became one of the notable figures at the start of the Haitian Revolution, especially during the Bois-Caiman revolt on August 14, 1791.

In short, the list of influential women is long. We could also talk about figures like Félicité Brissot, Sylvie Audouin (from the Hébertist side), Marguerite David (from the Enragés side), and more. Figures like Theresia Cabarrus, who wielded influence during the Directory (especially when Tallien was still in power), or the activities of Germaine de Staël (since it’s essential to mention all influential women of the Revolution, regardless of political alignment) are also noteworthy.

Napoleonic Era

Films could have focused more on women during this era. Instead, we always see the Bonaparte sisters (with Caroline cast as an exaggerated villain, almost like a cartoon character), or Hortense Beauharnais, who’s shown solely as a victim of Louis Bonaparte and portrayed as naïve. There is so much more to say about this time, even if it was more oppressive for women.

Germaine de Staël is barely mentioned, which is unfortunate, and Marie Anne Babeuf is even more overlooked, despite her being questioned by the Napoleonic police in 1801 and raided in 1808. She also suffered the loss of two more children: Camille Babeuf, who died by suicide in 1814, and Caius, reportedly killed by a stray bullet during the 1814 invasion of Vendôme. No mention is made of Simone Evrard and Albertine Marat, who were arrested and interrogated in 1801.

An important but lesser-known event in popular culture was the deportation and imprisonment of the Jacobins, as highlighted by Lenôtre. Here’s an excerpt: “This petition reached Paris in autumn 1804 and was filed away in the ministry's records. It didn’t reach the public, who had other amusements besides the old stories of the Nivôse deportees. It was, after all, the time when the Republic, now an Empire, was preparing to receive the Pope from Rome to crown the triumphant Caesar. Yet there were people in Paris who thought constantly about the Mahé exiles—their wives, most left without support, living in extreme poverty; mothers were the hardest hit. Even if one doesn’t sympathize with the exiles themselves, one can feel pity for these unfortunate women... They implored people in their neighborhoods and local suppliers to testify on behalf of their husbands, who were wise, upstanding, good fathers, and good spouses. In most cases, these requests came too late... After an agonizing wait, the only response they received was, ‘Nothing to be done; he is gone.’” (Les Derniers Terroristes by Gérard Lenôtre). Many women were mobilized to help the Jacobins. One police report references a woman named Madame Dufour, “wife of the deportee Dufour, residing on Rue Papillon, known for her bold statements; she’s a veritable fury, constantly visiting friends and associates, loudly proclaiming the Jacobins’ imminent success. This woman once played a role in the Babeuf conspiracy; most of their meetings were held at her home…” (Unfortunately for her, her husband had already passed away.)

On the Napoleonic “allies” side, Marie Angélique, the widow of Ronsin who later married Turreau, should be more highlighted. Turreau treated her so poorly that it even outraged Washington’s political class. She was described as intelligent, modest, generous, and curious, and according to future First Lady Dolley Madison, she charmed Washington’s political circles. She played an essential role in Dolley Madison’s political formation, contributing to her reputation as an active, politically involved First Lady. Marie Angélique eventually divorced Turreau, though he refused to fund her return to France; American friends apparently helped her.

Films could also portray Marie-Jacqueline Sophie Dupont, wife of Lazare Carnot, a devoted and loving partner who even composed music for his poems. Additionally, her ties with Joséphine de Beauharnais could be explored. They were close friends, which is evident in a heartbreaking letter Lazare Carnot wrote to Joséphine on February 6, 1813, to inform her of Sophie’s death: “Until her last moment, she held onto the gratitude Your Majesty had honored her with; in her memory, I must remind Your Majesty of the care and kindness that characterize you and are so dear to every sensitive soul.”

In films, however, when Joséphine de Beauharnais’s circle is shown, Theresia Cabarrus (who appears much more in Joséphine ou la comédie des ambitions) and the Countess of Rémusat are mentioned, but Sophie Carnot is omitted, which is a pity. Sophie Carnot knew how to uphold social etiquette well, making her an ideal figure to be integrated into such stories (after all, she was the daughter of a former royal secretary).

Among women soldiers, we had Marie-Thérèse Figueur as well as figures like Maria Schellink, who also deserves greater representation. Speaking of fighters, films could further explore the stories of women who took up arms against the illegal reinstatement of slavery. In Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, many women gave their lives, including Sanité Bélair, lieutenant of Toussaint Louverture, considered the soul of the conspiracy along with her husband, Charles Bélair (Toussaint’s nephew) and a fighter against Leclerc. Captured, sentenced to death, and executed with her husband, she showed great courage at her execution. Thomas Madiou's Histoire d’Haiti describes the final moments of the Bélair couple: “When Charles Bélair was placed in front of the squad to be shot, he calmly listened to his wife exhorting him to die bravely... (...)Sanité refused to have her eyes covered and resisted the executioner’s efforts to make her bend down. The officer in charge of the squad had to order her to be shot standing.”

Dessalines, known for leading Haiti to victory against Bonaparte, had at least three influential women in his life. He had as his mentor, role modele and fighting instructor the former slave Victoria Montou, known as Aunt Toya, whom he considered a second mother. They met while they were working as slaves. They met while both were enslaved. The second was his future wife, Marie Claire Bonheur, a sort of war nurse, as described in this post, who proved instrumental in the siege of Jacmel by persuading Dessalines to open the roads so that aid, like food and medicine, could reach the city. When independence was declared, Dessalines became emperor, and Marie Claire Bonheur, empress. When Jean-Jacques Dessalines ordered the elimination of white inhabitants in Haiti, Marie Claire Bonheur opposed him, some say even kneeling before him to save the French. Alongside others, she saved those later called the “orphans of Cap,” two girls named Hortense and Augustine Javier.

Dessalines had a legitimized illegitimate daughter, Catherine Flon, who, according to legend, sewed the country’s flag on May 18, 1803. Thus, three essential women in his life contributed greatly to his cause.

In Guadeloupe, Rosalie, also known as Solitude, fought while pregnant against the re-establishment of slavery and sacrificed her life for it, as she was hanged after giving birth. Marthe Rose Toto also rose up and was hanged a few months after Louis Delgrès’s death (if they were truly a couple, it would have added a tragic touch to their story, like that of Camille and Lucile Desmoulins, which I have discussed here).

To conclude, my aim in this post is not to elevate these revolutionary, fighting, or Napoleonic-allied women above their male counterparts but simply to give them equal recognition, which, sadly, is still far from the case (though, fortunately, this is not true here on Tumblr).

I want to thank @aedesluminis for providing such valuable information about Sophie Carnot—without her, I wouldn't have known any of this. And I also want to thank all of you, as your various posts have been really helpful in guiding my research, especially @anotherhumaninthisworld, @frevandrest, @sieclesetcieux, @saintjustitude, @enlitment ,@pleasecallmealsip ,@usergreenpixel , @orpheusmori ,@lamarseillasie etc. I apologize if I forgot anyone—I’m sure I have, and I'm sorry; I'm a bit exhausted. ^^

#frev#french revolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#women in history#haitian revolution#slavery#guadeloupe#frustration

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

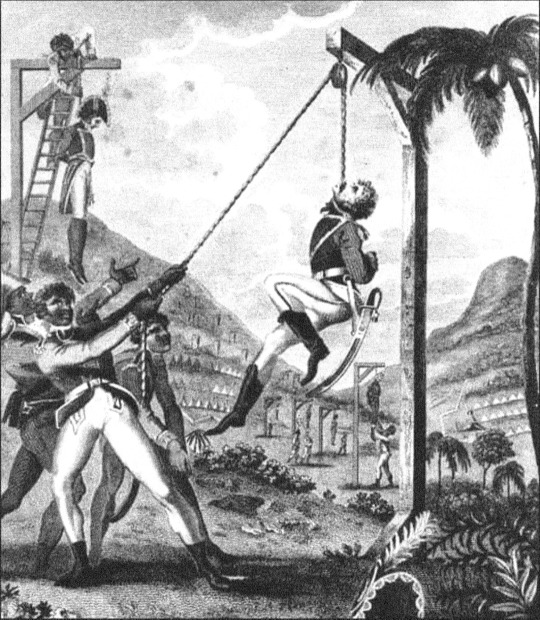

Vengeance de l'Armée Noire pour les cruautes exercees sur elle par les Francais / Revenge of the Black Army for the cruelties exercised on them by the french from An Historic Account of the Black Empire of Haiti (engraved by Inigo Barlow)

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Revolution of Saint Domingue after 1793

Alright @xshingie asked me about what happened on Saint Domingue after the events of 1793, because of the violence that eventually happened there. Which is quite convenient, as my French History tome just reached the "Revolution in the Colonies".

Castlevania Nocturne does a bit into the original slave uprising, which we mainly see from Annette's POV. This is your friendly reminder: If you saw the violence inflicted on some of the white plantation owners and thought "How horrible!" then you are a shitty person. Because the violence inflicted on those slaves before had been a lot worse. Slavery is the worst kind of violence. Always.

However, Nocturne obviously does not go that far into the details of it. Specifically it does not fully go into the difference between Free Men of Color, and the Black Slaves, and how only recently those Free Men were also considered citizen. It does not go into how a lot of Free Men also owned slaves. And most notably it also does not go into the mistake of the French Revolution to send a commander to Saint Domingue, who was an abolitionist, to stop the revolution in the colony. He obviously arrived there and was like: "Hey, rebels. Would you stop rebelling, if we gave you freedom and full rights of citizens?" And they were like: "Duh, that is what we are rebelling for." And he wrote back to France: "Welp, my hands are tied. It turns out I need to given them freedom."

And indeed, this succeeded. France declared the end of slavery, and while a lot of whites fled from the colonies to what was the freshly founded USA, where slavery was still legal. However, not all whites fled.

Of course, there was another problem, though: While some of the now freed people just started their own little farms where they cultivated food for themselves, which worked fine in feeding the people for now, some people understood how much worth the colonial products were to France and how much they were needed to support the revolution.

So, while the people were freed, many of them were ultimately forced again to work on the sugar and tabacco plantations - even though now they were being paid. They still were not given a choice about their work, which created a rather bad atmosphere. Because those people did not want to work those same sugar fields, obviously.

And of course the white French, who remained on the Island were not happy with those changed results. And there were several counter revolutionary attempts, but for a couple of days they went nowhere. Yes, people died because of it, but it still did not change anything.

And among the people on Saint Domingue - especially the Blacks - there rose the idea of being an independent republic.

Then came Napoleon.

I really cannot overemphasize how much Napoleon is responsible for everything in Europe and the former colonies today - especially the former French colonies.

In 1792 Toussaint Louverture, a self-freed slave took over the leadership role in Saint Domingue, and he had those ideas of making the country independent. And then Napoleon came into power in France, and Napoleon very much hated that idea.

Mind you, Napoleon was originally a revolutionary soldier. But basically Napoleon was: "You know what the problem was with absolute power? The wrong person in power. Thankfully I am the right person!"

I will not go too much into details when it comes to military movements and tactics. Let's just say: Napoleon send people over to Saint Domingue to regain the island. Spain and England also tried to get the island. And the free Blacks decided to use scortch earth tactics. Meaning: When they had to retreat, they would burn everything down that they left, so that the other armies had nothing to gain. (Something the Soviets later would also use a lot.)

During the conflicts that happened during the next one and a half years (mainly between 1801 and 1802) there were happening a lot of smaller "massacres", as the free Blacks trying to gain the island for themselves, were afraid that the whites would turn against them and cooperate with Napoleon's troops. So again and again there were white people killed, all while the idea of an indepedent nation started to emerge - icnluding the name of Haiti being brought up.

Eventually Toussaint however got captured through a French trick, and died shortly after in France. This lead to the Napoleonic forces to take Haiti.

However, this win was not long lived. Because remember the English and the Spanish? Yeah, they were here to get that Island. And there was further fighting - and in the end? The Haitians managed to win the island for themselves, but with people on all sides trying to push them down.

You have to understand this one thing: The Haitians, all of them Black, ruling themselves, was setting what the white colonialists would call "a dangerous precedent". Other slaves could get ideas, right? And oh boy, the white people did not want that. So they had to punish the Haitians for their win.

They forced Haiti to pay for their own freedom (I will talk about that more tomorrow), and tried to put all sorts of tariffs and what not onto exports from the island. And this... well, eventually lead to a massive pushback.

Now, there were a couple of times that white colonialist forces clashed with Black Haitians. And since the Revolution had started more than 200 000 Black people had been killed, compared to around 20 000 White French colonists. In fact, most people who died for France (about 70 000) where free colored people.

And, well... At some point the decision was made to expulse the white people from the island, and kill those who refused to leave. And mind you, a lot of people were reluctant about it. In fact, a lot of Blacks helped white people to flee the Island. But yeah, eventually about 5000 additional people were massacred. But mind you, this brought the number of those killed during the entire attempt for freedom of Haiti to about 270 000 non-whites vs. 25 000 white people (well, and then there were some white English, but those would have died either way, pretty much).

And yes, there is some chances: If Richter Belmont was still on St. Domingue by 1804, there is a chance that he might have been killed as well.

So... Let's tomorrow talk about the French Colonial Tax.

#castlevania#castlevania nocturne#castlevania netflix#history#historical context#french revolution#haitian revolution#haiti#saint domingue#war#revolutionary war

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

This ending scene in Wakanda Forever, Shuri finds out that T’Challa & Nakia had a son.

Nakia was in hiding in Haiti.

They named their son Toussaint.

Today is the anniversary of the real life Toussaint Louverture leading the Haitian slave revolt that defeated Napoleon and the French, earning their liberation and freedom.

The way Ryan Coogler wrote this and so many other gems and easter eggs within the Black Panther films is absolutely incredible.

Unfortunately, The United States of America and France have PUNISHED Haiti for revolting against slavery.

For 122 years, Haiti was forced to pay BILLIONS to France in REPARATIONS to SLAVEHOLDERS AND THEIR DESCENDANTS.

America helped force Haiti to do so.

The Eiffel Tower in Paris was paid for by Haiti…

Haiti gained its independence but was unable to invest in its own infrastructure as a new nation because of the crippling debt.

Many people are ignorant or play ignorant as to how events that happened over 100 years ago could have direct implications on how things are today.

The world is changing. Colonizers who have ruined the earth and treated people of color with evil and as less than human are continuing to be exposed.

This is why they want to control which parts of history are taught in schools.

Happy Independence Day Haiti. ✊🏿 🇭🇹🇭🇹🇭🇹

Toussaint Louverture (born c. 1743, Bréda, near Cap-Français, Saint-Domingue [Haiti]—died April 7, 1803, Fort-de-Joux, France) was the leader of the Haitian independence movement during the French Revolution (1787–99). He emancipated the enslaved people and negotiated for the French colony on Hispaniola, Saint- Domingue (later Haiti), to be governed, briefly, by formerly enslaved people as a French protectorate.

#ToussaintLouverture#ActivelyBlack#haiti#haitian revolution#black history#black panther#black films#black cinema#black people#blacklivesmatter#black lives matter#africa#france#colonization#slavery#enslaved#chadwick boseman#black panther wakanda forever#black excellence

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

231 Years Ago, the French National Convention Abolished Slavery

On February 4, 1794, the French National Convention made a radical decision: it abolished slavery in all its colonies. Enslaved people, who had been legally classified as biens meubles (property under French law), were now recognized as French citizens.

The decree formalized changes that were already underway in Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), where enslaved people had launched a massive uprising against their masters in August 1791. By 1793, French commissioners Léger-Félicité Sonthonax and Étienne Polverel had already abolished slavery on the island. Historians widely agree that the Convention’s bold move influenced Toussaint Louverture’s decision to switch alliances during the ongoing colonial war, abandoning the Spanish to fight alongside the French. (Read more)

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think one of the things I appreciated the most about Nocturne was the protagonism on the Haitian Revolution.

This was a revolution that didn't just change Haiti, it changed the world. This was the revolution that would make the first black state. The first slaveless state. That would make every slave nation tremble with fear, from Europe To America to Asia to Oceania to Africa. It was what was never meant to happen, but did.

It's the nation that would defeat Napoleon and the British marine. Nobody could take down Haiti. You know why Napoleon went to colonize Europe? Haiti. That's why. He couldn't take down Haiti. Couldn't make it french territory again. So, he turned towards Europe.

We are talking about an undefeated nation.

AND! AND! A largely Vodu nation!

I was SO happy to see Vodu be portrayed as the wonderful religion it is, sacred and divinely intertwined with the Haitian revolution. The revolution was noted to start with Vodu chants and ritual.

White people refused to understand the link between the two worlds that could bring ancestors to meet their descendants. They created zombies as a horror trope. They made vodu dolls as a horror gimmick. They took a sacred religion and reduced it and vilanized it.

And I'm so happy to see it being positively portrayed in such a famous media. Vodu practicioners have already made media of the like. But I was positively surprised with what Nocturne had to present to us.

Of course, the knowledge that the french revolution was incomplete, that it was NOT FOR EVERYONE, is then again, something I really appreciate as a history student and a person. The french revolution killed mostly peasent and established the bourgeoisie, but did it end the Noir Code? No. Did it establish women's and black people's suffrage? No. Did it make a agrarian reform? No. Was it for the people? It had it's importance. But it was, at the very least, not for all the people.

And let's not forget that the french revolution's main intellectual current would birth biological racism, an unscientific current that claimed evidence of "different sized skulls" for example to prove humans possessed different races based on phenotypes.

Last, but certainly not least: it is absurd to see people claim that "all indigenous people have been killed". Acknowledging multi-ethnic indigenous genocide HAS to go along with the respect that there STILL are indigenous people and they continue their fight for their lives and land.

You know who the show demonstrates as such? Olrox.

While I don't appreciate the show claiming "all of his people were slaughtered" as that is historically inaccurate, I was most happy to see an Aztec vampire present and very alive, connected to his culture, protagonizing the show. The Nahua are still very much alive and kicking and I appreciated that the show took that into account.

And Annette! Sweet Annette being one of the leads makes me most joyful. I can't stand idiots that claim her presence.on France was """historically innacurate""", check again, dumbasses, free black people were all over France (especially the children of black Caribbean elites, for example, from Haiti back then known as Saint-Domingue, which did not possess universities and would sent their children to study in Europe.)

Anyway. To see her star as one of the leads made me so incredibly happy. She's a wonderful character and I appreciate how they let Annette be unapologetic and direct, especially during a moment between revolutions were she was very aware the french revolution didn't mean shit to her people.

But she was so lovely and to see her afro-caribean religion present AND source of her power made me emotional more than a few times.

Castlevania Nocturne really did hit this nail on the head.

Anyways. To make sure I give people answers to "but where's the evidence to x thing you said?" Here are my sources:

THYLEFORS, Markel; “Our Government is in Bwa Kayiman:”A Vodou Ceremony in 1791 and its Contemporary Significations, 2009

DUBOIS, Laurent; Avengers of the New World : the story of the Haitian Revolution, 2004

BUCK-MORSS, Susan; Hegel, Haiti and universal history, 2009

#Castlevania nocturne#Haitian revolution#French revolution#castlevania annette#richter belmont#castlevania netflix#maria renard#tera renard#castlevania edouard#olrox#castlevania olrox#castlevania spoilers#I'm just a history student who really likes Haitian history#and who's sick and tired to see people glorify the french revolution#like if you wanted a revolution that was truly liberating and radical and you know REVOLUTIONARY#the Haitian Revolution is RIGHT THERE#like HELLOOOOOO#and i'm so sick of seeing Vodu religion demonized#it's a beautiful religion and it shouldn't matter what you think of it#it deserves to be respected#we all have a responsibility in anti-racism and anti-religious oppression#so work

439 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slavery in the Caribbean, North America, and South America: A Garveyite Analysis of Exploitation, Resistance, and the African Struggle for Liberation

“A People Without Knowledge of Their Past is Like a Tree Without Roots.” — Marcus Garvey

Slavery was not just an economic system; it was a war against African civilization, identity, and autonomy. The transatlantic slave trade was the largest forced migration in human history, robbing Africa of its people while enriching European and American empires.

However, wherever there was oppression, there was resistance. From the Maroons in Jamaica to the Quilombos of Brazil, from the Haitian Revolution to the rebellions across the U.S., Africans refused to submit.

This analysis examines how slavery functioned differently in the Caribbean, North America, and South America, the unique forms of brutality in each region, and, most importantly, how our ancestors fought for freedom.

1. The Scale of Enslavement: Where Did Most Africans Go?

One of the biggest misconceptions about slavery is that most Africans were taken to North America. The truth is:

Brazil (South America): Imported 5 million Africans – nearly 40% of the entire transatlantic slave trade.

The Caribbean: Imported 4.5 million Africans – about 35%.

North America (U.S. & Canada): Imported 500,000 Africans – less than 5%.

Yet, by the mid-19th century, the U.S. had the largest enslaved Black population. This is because:

In the U.S., slavery was designed to sustain itself through birth. Enslaved people were forced to reproduce, creating generations of captivity.

In the Caribbean and South America, enslaved people were worked to death. Instead of creating a self-reproducing enslaved population, Europeans simply replaced the dead with new Africans.

What does this tell us?

In North America, enslaved people lived longer—but only because they were seen as long-term investments, not because conditions were humane.

In Brazil and the Caribbean, the system was about extraction—Africans were disposable labor.

2. The Reality of Life Under Enslavement

The Caribbean: Sugar Plantations & Death Camps

The most brutal plantation economy.

Sugar production required constant back-breaking labor, exposure to fire, blades, and boiling water.

Average life expectancy was 5-10 years after arrival.

Torture was routine. Enslaved people who resisted were burned, dismembered, or thrown into boiling sugar vats.

Horrific mortality rates were over 50% of enslaved people in Barbados, and Jamaica died within three years of arrival.

Example: In the 18th century, Jamaica imported 1 million Africans, but the Black population never exceeded 350,000 because of high death rates.

Brazil: The Deadliest Place for an Enslaved African

Brazil received 10 times more Africans than the U.S.

Mortality was extreme—the average enslaved person in Brazil lived only 7 years after arrival.

Enslaved Africans were sent to gold and diamond mines as well as plantations.

Work conditions were so dangerous that enslaved people rarely survived long enough to have children.

Example: By 1888, when Brazil finally abolished slavery, only 1.5 million Africans remained—out of the 5 million who had been imported.

North America: Slavery Designed to Last Forever

Unlike in Brazil and the Caribbean, U.S. enslavers encouraged reproduction—enslaved women were forced to have children who would also be enslaved.

Enslaved people were concentrated in the U.S. South, working primarily in cotton, tobacco, and rice plantations.

Punishments were brutal—whippings, forced starvation, mutilation, and being sold away from family.

Enslaved people were forced to build the wealth of the U.S., generating profits that funded the industrial revolution.

Example: By 1860, the U.S. enslaved population had grown to 4 million people, despite importing fewer Africans.

3. African Resistance: How Enslaved People Fought Back

No matter where they were enslaved, Africans resisted. Some fought directly in revolts, while others resisted through escape, sabotage, and cultural survival.

The Caribbean: The Epicentre of Slave Revolts

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804): The only successful slave revolt that resulted in an independent Black nation. Led by Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and other African warriors.

Jamaican Maroons: Escaped Africans in Jamaica created independent communities and waged war against the British.

The Baptist War (1831): A massive revolt in Jamaica, led by Samuel Sharpe, that helped bring about the end of slavery in the British Empire.

Brazil: The Land of Quilombos and Islamic Uprisings

Quilombo dos Palmares (1605-1695): A powerful free Black kingdom led by Zumbi dos Palmares, who resisted Portuguese rule for decades.

The Malê Revolt (1835): An uprising led by African Muslim enslaved people in Bahia, one of the largest slave revolts in South American history.

North America: Rebellions and the Underground Railroad

Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831): A violent uprising in Virginia, where enslaved people killed white enslavers before being brutally repressed.

The Underground Railroad: A vast network of Black and white abolitionists who helped enslaved people escape to freedom.

Everyday acts of resistance: Breaking tools, slowing work, poisoning enslavers, and secretly preserving African traditions.

Fact: In the U.S., most enslaved rebellions were brutally crushed, but resistance continued in other forms.

4. After Slavery: How Each Region Treated Freed Black People

North America: Racial Segregation & Systemic Oppression

The U.S. replaced slavery with Jim Crow laws, segregation, and mass incarceration.

Black Codes restricted Black freedom—freed people could be arrested for being unemployed and forced back into labour.

The wealth gap between Black and white Americans remains a direct result of slavery.

Brazil: Slavery Ends, But Black People Remain at the Bottom

Brazil was the last country to abolish slavery (1888).

Freed Black people were excluded from land ownership and kept in extreme poverty.

Anti-Blackness remains deeply embedded—Afro-Brazilians face police violence and economic discrimination today.

The Caribbean: Black Majority, But Still Under White Rule

Jamaica, Haiti, Barbados, and other islands had Black majorities, but white elites still controlled the economy.

Many former enslaved people were forced into low-wage plantation labour.

Haiti was economically punished for its independence, forced to pay "reparations" to France for freeing itself.

5. Garvey’s Vision: Rebuilding Africa & Black Empowerment

Marcus Garvey understood that slavery didn’t end in 1865 or 1888—it evolved. The systems of oppression created during slavery still impact Black people globally.

The wealth stolen from Africa must be returned to Black hands.

Black people must control their own economies, land, and governments.

The future of African people is in unity.

"Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad!" — Marcus Garvey

Final Thoughts: Learning From the Past, Fighting for the Future

Slavery was meant to destroy us, but it failed. Our ancestors fought back, preserved our culture, and laid the foundation for Black liberation.

We must continue that fight—through economic empowerment, education, and Pan-African unity.

#black history#black people#blacktumblr#black tumblr#black#pan africanism#black conscious#africa#black power#black empowering#slavery#resistance#blog#african diaspora#black diaspora#african history#transatlantic slave trade#haitian revolution#garveyism#marcus garvey#black american history#afro Brazilian history#afro Caribbean history#decolonization#TruthInHistory

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture (ca. 1800)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mini Portraits of Three Revolutionary Women from Overseas Territories

French womens revolutionaries from mainland France are largely forgotten in France. But those from the Overseas Territories and Haiti are even more overlooked.

Victoria Montou aka Aunt Toya (presumed portrait)

(? – 1805)

A former slave working for the colonist Henri Duclos, she would be considered a second mother by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the future Lieutenant General under Toussaint Louverture, who briefly allied with General Leclerc as a strategic move before fighting against him again and becoming Emperor of Haiti. It is believed that she taught Dessalines about African culture and some combat skills while they were enslaved. Duclos saw their association as dangerous and decided to get rid of them by selling them to different slave owners, ensuring their separation.

On her new estate, where she was exploited again , Dr. Jean-Baptiste Mirambeau, who would later become the Emperor’s physician, noted, "Her commands are identical to those of a general." This observation would prove accurate as events unfolded. Toya led a group of slaves she was affiliated with, and together they took up arms, fighting against a regiment. According to Mirambeau, "This small group of rebels, under Toya's command, was quickly surrounded and captured by the regiment. During the struggle, Toya fled, pursued by two soldiers; a hand-to-hand combat ensued, and Toya severely wounded one of them. The other, with the help of additional soldiers who arrived in time, captured Toya."

Upon the proclamation of independence in January 1804 and Dessalines’ coronation as Emperor, he made Victoria Montou an imperial duchess. However, she fell gravely ill in 1805. Jean-Jacques Dessalines tried to heal her, saying, "This woman is my aunt; treat her as you would have treated me. She endured, alongside me, all the hardships and emotions while we were condemned to work the fields together." She died on June 12, 1805. She was given a grand funeral; her funeral procession was carried by eight brigadiers of the imperial guard and led by Empress Marie-Claire Bonheur.

Marthe Rose-Toto (1762? – December 2, 1802)

Marthe Rose-Toto was born around 1762 on the island of Saint Lucia, which became free following the abolition of slavery in Guadeloupe in 1794. According to some sources, she became a close companion of Louis Delgrès, an officer and fervent republican revolutionary, so much so that he was called a "Sans Culotte" by Jean-Baptiste Raymond de Lacrosse ( I've already discussed Louis Delgrès here: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/751677840407330816/on-this-day-die-louis-delgres-freedom-fighter?source=share) . However, in 1802, Bonaparte sought to reinstate slavery and sent General Richepance. Louis Delgrès and many others took up arms. It is noteworthy that women were as present as men in this struggle to maintain their freedom and dignity. When all was lost, Louis Delgrès and 300 volunteers chose to commit suicide by explosives, shouting the revolutionary cry "Live free or die," after ensuring the evacuation of the estate for those who were not willing. The repression was brutal.

According to historian Auguste Lacour, during the evacuation, Marthe Rose-Toto broke her leg and was brought to the tribunal on a stretcher. She was accused of inciting Louis Delgrès' resistance and inciting the murder of white prisoners. It should be noted that these accusations were generally false, intended to legitimize death sentences. She was hanged, and according to Lacour, her last words were, "Men, after killing their king, left their country to come to ours to bring trouble and confusion: may God judge them!" In any case, Marthe Rose-Toto is considered one of the most important women in the fight against the reinstatement of slavery, alongside Rosalie, also known as Solitude. Their struggles and sacrifices should not be forgotten, and they were not in vain, as slavery was once again abolished in 1848.

Flore Bois Gaillard

Flore Bois Gaillard was a former slave and also a leader. She was reportedly one of the leaders of the "Brigands" revolt on the island of Saint Lucia during the French Revolution. Little is known about her as a former slave, only that she lived in the colony of Saint Lucia. Local historian Thomas Ferguson says of Flore Bois Gaillard, "A woman named Flore Bois Gaillard—a name that evokes intrepidity—was among the main leaders of the revolutionary party," and that during the French Revolution, she was "a central figure in this turbulent group that would be defeated by the military strategies of Colonel Drummond in 1797."

The group that included Flore Bois Gaillard consisted of former slaves, French revolutionaries, soldiers, and English deserters. They were determined to fight against the English regiments, notably through guerrilla strategies. This group won a notable battle, the Battle of Rabot in 1795, with the help of Governor Victor Hugues and, according to some, also with the help of Louis Delgrès and Pelage. However, this group was ultimately defeated by the British, who retook the island in 1797. At this point, Flore Bois Gaillard’s trace is lost. Writer Édouard Glissant imagines in his book that she was executed by the British after the island was retaken in 1797. Nevertheless, she remains a symbol in this struggle and a national heroine. The example of Flore Bois Gaillard is also interesting because it clearly shows us once again that the French Revolution was also taking place in the overseas departments and that slaves or former slaves played a crucial role there in order to make her revolution triumph and were in all the battles.

#frev#french revolution#slavery#haiti#haitian revolution#guadeloupe#women of revolution#napoleonic era

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just remember ladies that Erzulie Dantor is always watching over us!

🇭🇹🧕🏾🗡

#history#erzulie dantor#haitian vodou#goddess#lwa#haitian history#black madonna#waterfalls#vodou#lgbt#womens history#lgbtq#black femininity#haitian revolution#divine feminine#black history#love#lesbian#women empowerment#slavery#haiti#lgbt history#1700s#precolonial africa#afro caribbean#nickys facts

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Edouard is my favorite character so far

Okay, I gotta talk about this boy. Because gods, I love him so much.

While Castlevania has once again done it (meaning: I basically like all the important characters, with the exception of Erzsebet), Edouard is really my favorite. And I am gonna explain to you why.

First, of course, my inner bard is very happy about this boy singing all the time. I already talked about the importance of music and, fuck yeah, I am very much here for it.

But no, the reason why I love this boy so much is, that he so clearly goes against the grain to do what is right.

He is a free Black. For those who have not read my earlier blog about the Haitian Revolution: In Haiti they had three classes of people. Whites, Free Blacks and slaves. Free Blacks were often the kids (or grandkids) of the white owning class, and often were ery wealthy. Both things we see in Edouard.

But here is the thing: Most free Blacks were against the Revolution, where against abolition. Because their riches also depended on the slaves doing free work.

And here we have Edouard, who most certainly also profits in one way or another from slavery being a thing. And he not only helps slaves escape, but he also helps to organize and finance the revolution. He even is there in the fight, even though he is a fucking opera singer. He is no fighter. And still he is there. And when Annette gets send to Europe though Cecil's vision, he is just there by her side, even though he does not need to. Even though he has what appears to be a lover waiting for him.

And when he gets turned into a night creature he is just such a pure soul, that he does not loose himself. In fact, he finds out that he can bring some of the other creatures back. And when Annette in the end tries to free him, he stays, for the other night creatures.

Because he is just such a good man.

Gods, I love him.

#castlevania#castlevania netflix#castlevania nocturne#castlevania edouard#edouard#haitian revolution

367 notes

·

View notes