#Cecile Fatiman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Incorruptible Interlude pt 3

From left to right we have:

Cecile Fatiman, a Vodou priestess who helped in sparking the Haitian Revolution.

Jean-Jacques-Regis de Cambaceres, a gay politician who was active during the Revolution.

Sophie de Condorcet, a writer and translator who hosted The Cercle Social, which aimed to promote women's rights.

Just a few examples of the wonderful progress that was made from 'this equality nonsense'. The revolution created a dizzying amount of progress in an incredibly short amount of time.

#can you spot the maxime and camille in this page?#incorruptiblecomic#frev#french revolution#bertrand barere#webcomic#comic#webtoon#history comic#historical fiction#haitian revolution#Cecile Fatiman#Jean-Jacques-Regis de Cambaceres#Sophie de Condorcet

141 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A manbo (also written as mambo) is a priestess (as opposed to a oungan, a male priest) in the Haitian Vodou religion. Haitian Vodou's conceptions of priesthood stem from the religious traditions of enslaved people from Dahomey, in what is today Benin. For instance, the term manbo derives from the Fon word nanbo ("mother of magic"). Like their West African counterparts, Haitian manbos are female leaders in Vodou temples who perform healing work and guide others during complex rituals.

This form of female leadership is prevalent in urban centers such as Port-au-Prince (the capital of Haiti). Typically, there is no hierarchy among manbos and oungans. These priestesses and priests serve as the heads of autonomous religious groups and exert their authority over the devotees or spiritual servants in their hounfo (temples).

Manbos and oungans are called into power via spirit possession or the revelations in a dream. They become qualified after completing several initiation rituals and technical training exercises where they learn the Vodou spirits by their names, attributes, and symbols.

The first step in initiation is lave tèt (head washing), which is aimed at the spirits housed in an individual's head. The second step is known as kouche (to lie down), which is when the initiate enters a period of seclusion. Typically, the final step is the possession of the ason (sacred rattle), which enables the manbos or oungans to begin their work. One of the main goals of Vodou initiation ceremonies is to strengthen the manbo's konesans (knowledge), which determines priestly power.

The specific skills and knowledge gained by manbos enable them to mediate between the physical and spiritual realms. They use this information to call upon the spirits through song, dance, prayer, offerings, and/or the drawing of vèvès (spiritual symbols). During these rituals, manbos may either be possessed by a loa (also spelled lwa, Vodou spirits) themselves, or may oversee the possession of other devotees. Spirit possession plays an important role in Vodou because it establishes a connection between human beings and the Vodou deities or spirits. Although loas can "mount" whomever they choose, those outside the Vodou priesthood do not have the skills to communicate directly with the spirits or gods. This is because the human body is merely flesh, which the spirits can borrow to reveal themselves via possession. manbos, however, can speak to and hear from the Vodou spirits. As a result, they can interpret the advice or warnings sent by a spirit to specific individuals or communities.

Cécile Fatiman is a Haitian manbo famously known for sacrificing a black pig in the August 1791 Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman—an act that is said to have ignited the Haitian Revolution. There are also notable manbos within the United States. Marie Laveau (1801-1888), for example, gained fame in New Orleans, Louisiana, for her personal charm and Louisiana Voodoo practices.

Renowned as Louisiana's "voodoo queen", Laveau's legacy is kept alive in American popular culture (e.g., the television series America Horror Story: Coven).ne Mama Lola is another prominent manbo and Vodou spiritual leader in the United States. She rose to fame after the publication of Karen McCarthy Brown's ethnographic account Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Mama Lola's success provided her with a platform to challenge Western misconceptions of Haitian Vodou and make television appearances

#kemetic dreams#vodun#cecile fatiman#manbo#bois caiman#manbos#haitian#marie laveau#new orleans#new orleans voodoo#mama lola#vodou#lwa#oungan#nando#fan#west african#west african vodun#mother of magic#joey bada$$#brooklyn

290 notes

·

View notes

Note

So is Richter gonna meet Cecile in S3?

Sure, why not. Let's turn Annette into Aang and let her incarnate every spirit or something :P I'm sure she'll have... interesting things to say about her pupil hooking up with a French/Romanian/American man of noble descent :P

#anyway i was very ashamed to learn recently that cecile fatiman was a real historical figure#i learned something new#and i guess then the show doesn't discriminate when it comes to adapting real people lol

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

LADY LOVE [1][2][3]

Notes

Lola, Mama & Brown, Karen McCarthy. "The Altar Room: A Dialogue." In Cosentino, Donald. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. United States, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995. p. 229. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/sacredartsofhait0000unse/mode/1up?

Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. United States, University of California Press, 2001. pp. 225-246.

Context: “Haitians have a talent for capturing history in terse images. Seven Stabs of the Knife was the name of the compound in Port-au-Prince where Philomise lived at the time Alourdes was born. It was named after an infamous event that occurred there not long before Philo moved in. A fight began in the compound with words between a man and his female partner. Their anger escalated, and the man rushed into the house for a knife. In front of their neighbors, he killed the woman by stabbing her seven times. People probably did not have to think too long or too hard to realize that this event belonged in the domain of Ezili Je Wouj (Ezili of the Red Eyes), another name for Danto.” Source: Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. United States, University of California Press, 2001. pp. 232-233.

Mocombe, Paul C. "Gede and Homosexuality." Philosophy 13.7 (2023): 278-283. https://doi.org/10.17265/2159-5313/2023.07.002

Mocombe, Paul C. “Practical Reason in Haitian Idealism: Anti-Dialectics, Reciprocal Justice, and Afeminism Epistemology.” Race, Gender & Class, vol. 25, no. 1–2, 2018, pp. 31–47. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26649532. Accessed 4 Dec. 2024.

”According to Seviteurs, manbo Fatiman was mounted by the Petwo lwa, Manbo Erzulie Danthor (the lunar Goddess of the Haitian nation who the Africans summoned through the sacrifice), who meted out the punishment for the whites, and laid out the hierarchy of the leadership of the revolution”. Source: Mocombe, Paul C. “Practical Reason in Haitian Idealism: Anti-Dialectics, Reciprocal Justice, and Afeminism Epistemology.” Race, Gender & Class, vol. 25, no. 1–2, 2018, pp. 31–47. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26649532. Accessed 4 Dec. 2024.

There are multiple accounts of Bwa Kayiman. A Petro aspect of Ezili is invariably identified with Manbo Cecile Fatiman, but the particular manifestation varies by account. In a different account, it is Ezili Kawuolo who is said to have mounted Manbo Fatiman. From Beauvoir-Dominique’s interview with Gustave Augustin and initiates of the Temple Nago of Cap Haitien, year 1900: “Our Lady of the Assumption, imposed by the French crown as national patron, symbol of Virgin purity and celestial quality, for future Haitians, turned into Ezili Kawoulo, an ancient and severe Vodoun divinity who unleashes thunder and lightening. It was she who, on August 14th, 1791, would “mount” an elderly woman at the Bois Caiman ceremony, sacrificing a pig and drinking blood for the sake of Revolution. According to legend, Kawoulo refused to dismount before the following day; such is the significance of the Assumption on August 15th and its celebrations in Haiti.” Source: Beauvoir-Dominique, Rachel. “Underground Realms of Being: Vodoun Magic.” In Cosentino, Donald. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. United States, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995. p. 162. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/sacredartsofhait0000unse/page/162/mode/2up

Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. United States, University of California Press, 2001. p. 229.

Especially feared is Ezili Je Wouj, described as the “fierce, ultra-Petwo manifestation of Ezili Dantò”. Source: Cosentino, Donald. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. United States, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995. p. 430. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/sacredartsofhait0000unse/page/430/mode/1up

Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. United States, University of California Press, 2001. p. 231-232.

The organization KOURAJ used the term “La Communauté M” to describe the LGBTI community of Haiti, as Western terms are not commonly used outside of the educated elite. The words used in Kreyòl are masisi, miks, madivin, makomè, & monkonpè. Masisi is an insult, akin to “fag”, but has been reclaimed by some, as there is no better alternative in Kreyòl. While masisi is roughly translated as “gay”, it actually means “acting as the female partner in a homosexual relationship”. For this reason, it is not uncommon for those in the diaspora to adopt trans feminine or non-binary identities. Miks roughly means “bisexual”, and makomè roughly means “trans woman”. The president of KOURAJ was murdered in 2019, but is succeeded by organizations including ACIFVH Kaytransayiti, OTRAH, and CNRCTH. In a similar fashion, madivin is another insult that is akin to “dyke”. While madivin refers to women who are attracted to other women, it is not always used in the same way that “lesbian” is used in the West; many gason trans describe themselves as madivin. Monkonpè is the transmasculine counterpart to makomè that was recently reclaimed by activists: “An Ayiti, yon mo ki endike yon moun ki se yon femel (yon moun ki fet ak seks fanm), men ki idantifye kòm yon gason sosyete a idantifye kòm Monkopé (Mo monkonpè a dirèkteman soti nan mo franse- ke kreyòl ta ka tradwi kòm “tonton”). Mo a gen yon istwa diskriminan, sepandan, nan dènye tan sa yo aktivis ak kèk manm nan kominote a kòmanse itilize ak yon konotasyon pozitif.” –Dominique St. Vil. The term gason trans (or gason transjan) is also used to describe someone who identifies as a man but is born of the female sex (AFAB), generally attracted to women. As described in the report, lesbian/bisexual/queer women and trans masculine people (“LBQTM”) struggled with these identity labels, as most Haitians do not separate sexual orientation (oryantasyon seksyèl) from gender identity (idantite seksyèl), and neither Western terms nor monkonpè were commonly used. See: FACSDIS, OTRAH, St. Vil, D., Theron, L., Carrillo, K., and Joseph, E. (2020) ‘From Fringes to Focus - “A deep dive into the lived-realities of Lesbian, Bisexual and Queer women and Trans Masculine Persons in 8 Caribbean Countries”. Amster- dam: COC Netherlands. https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/AA00083427/00006 Retrieved from: https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/AA/00/08/34/27/00006/Haiti_Report_Caribbean_CREOLE_25_01.pdf

Quoting Charlot Jeudy, the former President of KOURAJ: “After we were in 2010, with the massive earthquake that struck the country and brought destruction on all of us. And we saw a large number of Western evangelicals, especially from the United States, arrive under the pretext of preaching the gospel and the return of Christ. This soon became preaching homophobia and hate towards our community M, blaming the earthquake that had struck the country on sex between men, between women. Don’t forget that 65% of the country was illiterate and didn’t have any deep understanding behind the cause of seismic movements.…Many other friends found themselves in the camps for 2 or 3 months after the earthquakes and in them our Republic became more of a theocracy run by the religious. Everyone was preaching and the preachers were foremost attacking gays and transsexuals…Those in the camps were being heavily persecuted and forced to leave to find shelter elsewhere due to what was coming from these preachers (saying they were sinners, etc.).” SOURCE: A Cases Rebelles’ conversation with Charlot Jeudy, President, Executive Committee of Kouraj (Haiti), Retrieved from: https://www.q-zine.org/non-fiction/kouraj/

International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) and SEROVie. "The impact of the earthquake, and relief and recovery programs on Haitian LGBT people." (2011). Retrieved from: https://iglhrc.org/sites/default/files/505-1.pdf

“Transgender sex workers are often harassed, arrested and raped by police officers as well as the clients they service.” Source: Theron, L. Over-policed, Under-protected: Experiences of Trans and Gender Diverse Communities in the Caribbean. OutRight Action International and UCTrans. 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/cfi-subm/2308/subm-un-hrc-realisation-cso-caribbean-ngo-coalition-annex-3.pdf

“In March 2010, Jean M. was threatened and physically attacked for supposedly flirting with a man sitting across from him on a taptap (local bus). When he found a nearby policeman, rather than explaining that he was being harassed as a result of his sexuality, he told the policeman that he had been a victim of theft because, he said, “I knew that [the police] would only help me if I told them that I had been robbed. If the police knew I was gay, they would have attacked me instead of the man who beat me.” Source: International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) and SEROVie. "The impact of the earthquake, and relief and recovery programs on Haitian LGBT people." (2011). Retrieved from: https://iglhrc.org/sites/default/files/505-1.pdf

FACSDIS, OTRAH, St. Vil, D., Theron, L., Carrillo, K., and Joseph, E. (2020) ‘From Fringes to Focus - “A deep dive into the lived-realities of Lesbian, Bisexual and Queer women and Trans Masculine Persons in 8 Caribbean Countries”. Amster- dam: COC Netherlands. https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/AA00083427/00006 Retrieved from: https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/AA/00/08/34/27/00006/Haiti_Report_Caribbean_CREOLE_25_01.pdf

Theron, L. Over-policed, Under-protected: Experiences of Trans and Gender Diverse Communities in the Caribbean. OutRight Action International and UCTrans. 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/cfi-subm/2308/subm-un-hrc-realisation-cso-caribbean-ngo-coalition-annex-3.pdf

“In 1984, I was seated at Maggie’s kitchen table, reading her copy of the New York Post and lamenting the rhetoric of John Cardinal O’Connor on abortion. “He doesn’t have to use the word murder all the time,” I said. “‘It is murder!” shouted Alourdes and Maggie with one voice…the Vodou spirit Ezili Danto is understood to oppose abortion, as Alourdes’s and Philo’s dreams indicated. “It really make her mad!” Alourdes once said. “She don’t like abortion because she really love children. But, you know, human being do everything. That’s life! Right? Abortion something human created. Right?”...Vodou morality is not a morality of rule or law but a contextual one. It is tailored not only to the situation but also to the specific person or group involved...Abortion “is murder,” but it is also the only choice to make in some situations…” Source: Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. United States, University of California Press, 2001. p. 231-232.

Anne Lescot & Laurence Magloire's documentary (2002) Des hommes et dieux interviews several self-identified masisi, who repeatedly point to Ezili Dantò as their lwa of protection. The corrective rape of madivin, gason trans, and monkonpè is also the domain of Ezili Dantò. Lescot & Magloire’s documentary can be viewed here: [Kanopy] [Vimeo]

In the series “FROM FRINGES TO FOCUS”, the Haitian report stands out for several reasons. Although it contains the fewest number of respondents, the quality of data is higher, no doubt due to the efforts of Dominique St. Vil. Additionally, it is the only report where the majority of respondents identified themselves as trans masculine (gason trans/monkonpè/lòt) as opposed to cisgender (fanm). Furthermore, it is the only country where the majority of religious respondents identified Vodou as their religion; in all other countries, most religious respondents were Christian. This is owed to the fact that respondents were collected by reaching out to Vodou temples. The fact that this many trans masculine Haitians could be found in Vodou temples confirms the tolerant nature of this religion. The comment that Vodou is more tolerant because of its West African roots is also interesting. As far as I know, West African Vodun has traditionally been intolerant of homosexuality and transsexuality, although certain forms of cross-gender behavior and lesbian activity have been tolerated: “Up until the present, the MWHS has parroted the "official stance" (as detailed in the following chapter) of the elders in the Vodoun religion, the majority who are against initiating GLBs [gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals]...Typically, if one were to inquire of an African if homosexuality ever existed in African culture, the usual response would be "no, never!" Many Africans even blame the existence of homosexuality on the Europeans and the Arab invaders, whom today dominate the adult male and child homosexual prostitution markets that exist along any African tourist strip. However, upon closer examination, moral and political sentiments aside, historically both responses would be generally correct. At present, there is no evidence that there ever existed a "culture" of homosexuality in African society. In the Mami Wata Vodoun tradition, there is not even a vocabulary to describe homosexuality or any other form of sexuality for that matter…” Naturally, these comments also apply to transgender identity. This is not to suggest West African Vodun is entirely intolerant of homosexuality, as Mama Zogbé describes a stance that is not entirely negative nor entirely inclusive: “The decision of how one empresses any aspect of their lives including their sexuality if they are seeking guidance from Afá,/Mami/Vodoun is based upon one's individual destiny, and whatever else is prescribed by Afá, or Mami or the Vodoun.” She also describes Haitian Vodou as: “perhaps (outside of Brasil) the most tolerant of homosexuality.” The fact that Haitian Vodou, and other traditions in the New World, became more tolerant of homosexuality and transgenderism than their West African roots is something to be remarked upon. As far as I can tell, it speaks to the manner in which Haitian Vodou prioritizes the needs of the Haitian people over rigid doctrine. For Mama Zogbé’s full commentary on this matter, see: Zogbé, Mama. Mami Wata: Africa's Ancient God/dess Unveiled Vol. II. Mami Wata Healers Society of North America Inc., Martinez, GA. 2007. pp.575-591. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/mamiwataafricasa0002mama/page/575/mode/2up

From a different source, I heard that the child on her wrist is called Ti Gougoune.

Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. United States, University of California Press, 2001. pp. 228-229

From Marilyn Houlberg’s interview with Georges René: "...You have two spirit girls who love you. Each of them has a husband. There is Freda with her husband Sen Jak, and Dantò with Ogou Fer…" Source: René, Georges & Houlberg, Marilyn. "My Double Mystic Marriages to Two Goddesses of Love." In Cosentino, Donald. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. United States, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995. p. 290. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/sacredartsofhait0000unse/page/290/mode/2up;

Mirabeau, Daniel & Hebblethwaite, Benjamin. (2013). “Repertoire of Haitian Vodou Songs.” Vodou songs of Mirebalais. Retrieved from: https://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/AA/00/01/93/89/00001/Vaudou_songs_Mirebalais_2013.pdf

This is exemplified by Zora Neale Hurston’s description: “A tragic case of a Guedé mount happened near Pont Beudet. A woman known to be a Lesbian was “mounted” one afternoon. The spirit announced through her mouth, “Tell my horse I have told this woman repeatedly to stop making love to women. It is a vile thing and I object to it. Tell my horse that this woman promised me twice that she would never do such a thing again, but each time she has broken her word to me as soon as she could find a woman suitable for her purpose. But she has made love to women for the last time. She has lied to Guedé for the last time. Tell my horse to tell that woman I am going to kill her today. She will not lie again.” The woman pranced and galloped like a horse to a great mango tree, climbed it far up among the top limbs and dived off and broke her neck.” Interestingly, she also described some association between Erzulie Freda and women with queer tendencies: “Women do not “give her food” unless they tend toward the hermaphrodite or are elderly women who are widows or have already abandoned the hope of mating.” Source: Hurston, Zora Neale. Tell my horse. United Kingdom, HarperCollins, 1990. Originally published in 1938. Retrieved from: https://bookreadfree.com/book/24210

In New Orleans, Ezili Dantò is identified with Our Lady of Prompt Succor by the followers of Sallie Ann Glassman. A staple of New Orleans tourism, Glassman has a number of critics in the Haitian community, who do not consider her to be a good representative of Haitian Vodou. The majority of her followers are white Americans who have no connection to Haiti or Western Africa, but a minority actually does. As such, I am uncertain whether people of Haitian and African blood generally agree with this identification, or not.

In an interview conducted by Marilyn Houlberg, Georges René also described Ezili Dantò as a “lesbian” (really, bisexual): “She loves men, yeah, but she's a lesbian...She's marrying me, but she sleeps with women.” Source: René, Georges & Houlberg, Marilyn. "My Double Mystic Marriages to Two Goddesses of Love."In Cosentino, Donald. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. United States, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995. p. 299. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/sacredartsofhait0000unse/page/298/mode/2up?

“Danto’s days are Tuesdays and/or Saturdays. She is dressed in blue, red, and multicolored fabrics, and likes to be sprayed with Florida Water. She drinks Barbancourt rum, and prefers to eat fried pork (griyo). If she smokes, it is unfiltered Camels or strong Haitian cigarettes.” Source: Cosentino, Donald. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. United States, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995. p. 300. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/sacredartsofhait0000unse/page/300/mode/2up?

“The following song reveals her culinary preferences: “Fried pork, plantain, that’s what Dantò eats.”Her followers offer her jewelry, dresses, scarves, perfume, cigarettes, and rum.” Source: Hebblethwaite, Benjamin, and Bartley, Joanne. Vodou Songs in Haitian Creole and English. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 2012. p. 235

0 notes

Text

Yay! I'm so glad you finally got your copyrighted video back! Another woefully underrated video. I had a lot of criticisms about Nocturne writing-wise, but at the same time, even though I think the original Castlevania show is better-written, something about the characters/themes/messages resonated with more deeply that I found myself far more attached to. I really liked how you brought up the parallels between the societal reason why these monsters were created -- they are, after all a reflection of humanity. I really liked how Nocturne attempted to setup vampires in the context of allegorical themes of class oppression, the enduring scar that colonialism leaves on its people, and slavery. It really set up more meaningful commentary on society. Correct me if I'm wrong, but there is also an thematic element of vampires being vehicles for suppression/indulgence of sexuality -- there's a reason why vampire attacks are setup as sexual attacks (i.e., biting in the neck, the sensation being described as erotic, their hypnotic powers). These are themes common in Bram Stoker's Dracula. I think that could also tie into Nocturne as well, since there was commentary on the Abbott not being exempt from celibacy.

I also appreciated the additional historical insight you brought into your analysis and I agree that understanding more of the history elevates the viewing experience. I found myself researching more about Haitian Vodou and realized there were so many subtle blink-and-you'll-miss-it-moments in Annette's flashback and displays of powers that aren't even explained to you (i.e., all the veve symbols, Papa Legba, Edouard acknowleding his privilege as part of the gens de couleur, the vodou ceremonial rituals that Cecile Fatiman who was a IRL revolutionist that were actually gathering points to organize revolutions) -- all these things I'm mentioning I didn't know anything about and it wasn't until I read further I could appreciate more of the story. I don't know much about the French revolution besides the very basics (the class issues, ideals of democracy, etc), so I will definitely be doing more research there! :)

I agreed on a lot of your points and takes on the characters. I also thought Erzabeth Bathory, while a really bad villain character wise (good god, her character was really cringe for me), I can see what they're trying to do thematically. Drolta was super enjoyable and dynamic to watch on screen. I know people were upset that Richter wasn't the front-and-center of the show, but I think what works really well for the Belmont formula is that oftentimes the Belmont is the straight-man main character, that enables the supporting characters to come to life. Trevor Belmont is also an example where he is kind of boring by himself, but the show's characters really only came alive with the entertaining interactions of the titular trio.

My favorite character is Annette! :D I love the drive, dimension of her character. I know everybody loves Olrox, but I am just so in love with Annette, with her flaws and everything. I really like the parallel arcs between Richter and Annette (can you tell I'm a shipper, heh).

On a off-topic note, your voice is very soothing and calm to listen to :D

youtube

I was finally able to get the video put back up! Please, give it a look and tell me what you think!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cecile Fatiman

#haiti#french creole#haitian revolution#lady creole#madame iris#voodou#voodooqueen#vodun#voodoo#voudou#cecil fatiman

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Giving thanks to all the ancestors who fought for freedom and liberation!! May your memory and contribution never be forgotten. The Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) was a revolt from enslaved Africans in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which culminated in the elimination of slavery there and the founding of the Republic of Haiti. Jean-Jacques Dessalines (20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a lieutenant to Toussaint Louverture who led the revolution, after Louverture was captured the Haitian revolution continued under Dessalines who defeated the French becoming the first ruler of a independent Haiti under the 1801 constitution. He is considered the founder of Haiti. The Haitian Revolution was the only revolt of enslaved Africans, which led to the founding of a state. Furthermore, it is generally considered the most successful slave rebellion ever to have occurred and as a defining moment in the histories of both Europe and the Americas. The rebellion began in August 1791 in a secret Vodou ceremony led by Dutty Boukman and Cecile Fatiman. It ended in November 1803 with the French defeat at the battle of Vertières. Haiti became an independent country on January 1, 1804. https://www.instagram.com/p/B6yUHVoHHjq/?igshid=u9ojgwn9whxw

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day 5 years ago I was called to Ferguson by my ancestors to do the work. On this days 5 years ago I understood from my bones what spiritual activism is and how we have always used this for our liberation. On this day 5 years ago I was operating on spirit. On this day 5 years ago someone took a picture of me while I was healing, helping and protecting the people while hexing the police. On this day 5 years ago something died so my most fierce self could be born. On this day 5 years ago I choose to fight back as healer, as a Priestess, as a Conjurer. On this day 5 years ago I set myself on a course that changed my life. On this day 5 years ago the Spirits of Harriet Tubman and Cecile Fatiman guided my every step and my every movement. This moment changed my life. For this I am grateful. #Ferguson #LadySpeech https://www.instagram.com/p/B5dKZvGAgUP/?igshid=x16x388602ly

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

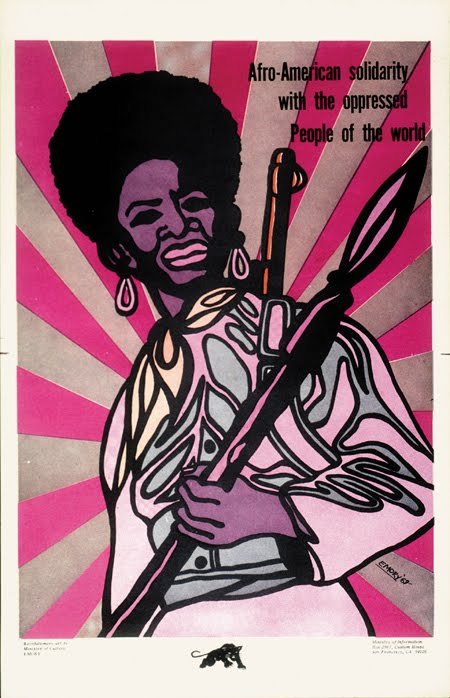

Black August 💜

377 notes

·

View notes

Text

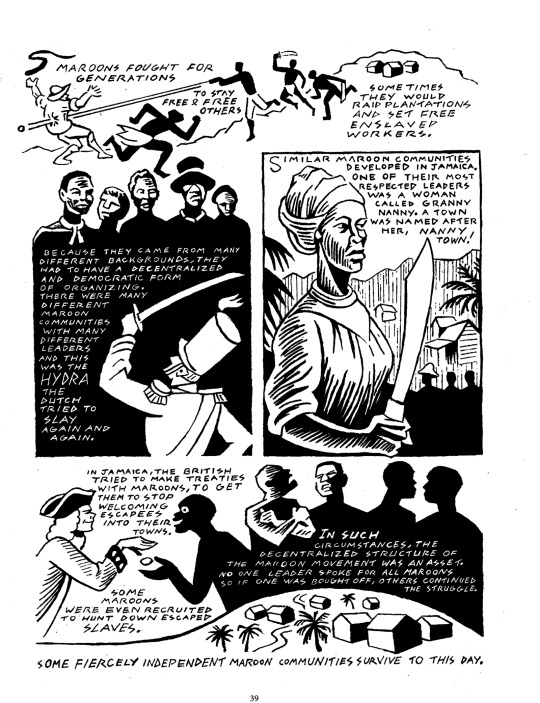

Maroon Comix: Origins and Destinies

Maroon Comix: Origins and Destinies

Conceived, compiled and coordinated by Quincy Saul, illustrated by Songe Riddle, Mac McGill, Seth Tobocman, Hannah Allen, Emmy Kepler and Mikaela Gonzalez, with selections primarily from the writings of Russell Maroon Shoatz. ISBN: 978-1-62963-571-2; $15.95 from PM Press, PO Box 23912, Oakland CA 94623, www.pmpress.org. wwww.ecosocialisthorizons.com; [email protected]

Reviewed by Michael Novick, Anti-Racist Action LA

This fascinating book, based primarily on the writings of political prisoner Russell Maroon Shoats (#AF-3855, SCI Dallas, 1000 Follies Rd. Drawer K, Dallas PA 18612-0286), examines the history of slavery and liberation, particularly the form of resistance known as "maroons" -- escapees from slavery, or territories liberated from slavery by rebellion, such as Haiti -- in the US, the Caribbean and South America by applying the techniques of graphic novels to sometimes dense political tracts and analysis, increasing their appeal, accessibility and imbuing them with the spirit of a new Black arts movement as well as the cultural creativity and many-sidedness of the maroons themselves.

Sections include a short "Initiation" to the concept of the maroons, and pieces on "Slavery and Liberation", Modern Maroons, and most challenging perhaps, Shoats's manifesto "The Dragon or the Hydra?" counterposing centralized and hierarchical liberation movements or struggles, --the dragon -- too often sold out by their own leadership, with the more decentralized, horizontal and variegated "maroon" struggles -- the hydra, which grows many new heads when decapitated.

This is of course an issue in contention not only in the Black liberation movement, and among former Black Panthers and Black Liberation Army members like Shoats or their latter-day successors, but in many movements and contexts. Consider the contrast between the recent essentially anti-electoral presidential campaign of the Zapatista-influenced Marichuy and the more more traditional, and finally successful, of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who will take office as president of Mexico in December with a strong legislative and gubernatorial cadre of MORENA partisans who ran with him.

As the piece acknowledges, it may be faulty to identify all virtue with the autonomous communities of the Maroons. "In Jamaica, the British tried to make treaties with the maroons, to get them to stop welcoming escapees into their towns. Some maroons were even recruited to hunt down escaped slaves." While Shoats see the decentralized structure of the maroons as an asset, so that "if one [leader] was bought off, others continued the struggle," it seems clear that autonomy or decentralization in itself is not a safeguard against cooptation, nor do maroon zones or liberated areas necessarily threaten the entire edifice of empire and slavery.

A stronger element of the same piece, however, is definition of a "mosaic" -- a Movement of Oppressed Sectors Acting In Concert. Each group (women, New Afrikan and Pan-Afrikan peoples, Puerto Ricans, anarchists, Chicanos and Mexicans, Asians, LGBTQ people, etc) "retains its integrity, has its own culture and autonomy, but we are united because we share one economy, one ecology, and one planet. we must work together for our survival and our freedom." This segues naturally into two final sections, "Modern Maroons" and an extensive bibliography of suggested additional readings of more traditional texts about maroons historically and currently and analyses of the system and of approaches to overturning and replacing it. The book has some of the appeal of "Addicted to War," but is much more variegated in artistic styles and types of content, including a series of biographies and full page portraits of a large number of exemplars of the maroon spirit the book promotes, such as Haitians Ezili Dantor, Cecile Fatiman and Dutty Boukman, Queen Mother Moore, and the Black Liberation Army. Those introduced to the material thereby will find a wealth additional reading and study, as mentioned, in Saul's bibliographic "Maroon Library," (with thanks expressed to Matt Meyer and Richard Price).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lupine Publishers | Antidialectics: Vodou and The Haitian Revolution in Opposition to The African American Civil Rights Movement

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Anthropological and Archaeological Sciences

Introduction

The dialectical integration of black Americans into the Protestant Ethic and the spirit of capitalism of the West via slavery, the African American civil rights movement, and globalization marks the end of black American history as a distinct African worldview manifesting itself onto the world. A black/African practical consciousness as represented in Haitian Vodou and Kreyol, for example, manifesting itself in praxis and the annals of history via the nation-state of Ayiti/ Haiti is slowly being supplanted by a universal Protestant Ethic and the spirit of capitalism phenotypically dressed in multiethnic, multiracial, and multisexual skins speaking for the world. This latter worldview has not only erased a distinct African practical consciousness among black Americans, but via the African- Americanization of the black diaspora in globalization through the hip-hop culture of the black American underclass, on the one hand, and the prosperity gospel of the black American church and bourgeoisie on the other is seeking to do the same among blacks globally in the diaspora while simultaneously destroying all life on earth [1]. This work focuses on how and why the purposiverationality, antidialectics, of the originating moments of the Haitian Revolution and Vodou diametrically opposes that of the African American Civil Rights movement. The author concludes that the intent of the originating moments of the Haitian Revolution at Bwa Kayiman (Bois Caiman) was not for equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition with whites by reproducing their norms and structure, as in the case of the African American civil rights movement under the purposive-rationality of liberal bourgeois black Protestant men, but for the reconstitution of a new world order or structuring structure (libertarian communism) “enframed” by an African linguistic and spiritual community, Vodou and kreyol, respectively, grounded in, and “enframing,” liberty and fraternity among blacks or death. In fact, the author posits that it is the infusion of the former worldview, liberal bourgeois Protestantism via the Protestant Ethic and the spirit of capitalism, on the island by the mulatto elites and petit-bourgeois free persons of color, Affranchis, looking to Canada, France, and America for equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition that not only threatens Haiti and its practical consciousnesses, Vodou and Kreyol, contemporarily, but all life and civilizations on earth because of its dialectical economic growth and accumulative logic within the finite space and resources of the earth.

Background of the problem

Traditional interpretations of the Haitian Revolution and the black American Civil Rights movement of the 1960s attempt to understand the two sociohistorical phenomena within the dialectical logic of Hegel’s master/slave dialectic [2-4]. Concluding that both events represent a dialectical struggle by the enslaved Africans, who have internalized the rules of their masters, for equality of opportunity, recognition, and distribution within and using the metaphysical discourse of their former white masters to convict them of not identifying with their norms, rules, and values as recursively organized and reproduced by blacks. This traditional liberal bourgeois interpretation of the Haitian revolution attempts to understand its denouement through the sociopolitical effects of the French Revolution when the National Constituent Assembly (Assemblée Nationale Constituante) of France passed la Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen or the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen in August of 1789. The understanding from this perspective is that the slaves, many of whom could not read or write French, understood the principles, philosophical and political principles of the Age of Enlightenment, set forth in the declaration and therefore yearned to be like their white masters, i.e., freemen seeking liberty, equality, and fraternity, the rallying cry of the French Revolution [4-16].

Although, historically this understanding holds true for the mulattoes and free petit-bourgeois blacks or Affranchis who used the language of the declaration to push forth their efforts to gain liberty, equality, fraternity with their white counterparts as slaveholders and masters as brilliantly highlighted by Laurent Du Bois [3]. This position, I posit here, is not an accurate representation for the Africans who met at Bois Caïman, the originating moments of the Haitian Revolution. The Affranchis, embodied in the person of Toussaint Louverture, for example, like their black American middle class counterparts, dialectically pushed for liberty, equality, and fraternity with their white counterparts at the expense of the Vodou discourse and Kreyol language of the pep, the majority of the enslaved Africans who were not only discriminated against by whites but by the mulattoes and free blacks as well who sought to reproduce the French language, culture, religion, and laws of their former slavemasters on the island [5]. Toussaint believed that the technical and governing skills of the Blancs (whites) and Affranchis would be sorely needed to rebuild the country, along the lines of white civilization, after the revolution and the end of white rule on the island. In fact, Toussaint was not seeking to make Haiti an independent country; but sought to have the island remain a French plantation colony, like Martinique and Guadeloupe, without slavery [3]. Although Dessalines’s nationalistic position, which was similar to Toussaint’s, would become dominant after the capture of Toussaint in 1802, his (Dessalines’s) assassination by a plot between the mulatto, Alexandre Pétion, and Henri Christophe, would see to it that the Affranchis’s purposive-rationality would come to historically represent the ideals of the Haitian quest for independence. This purposive-rationality of the Affranchis, to adopt the ontological and epistemological positions of whites by recursively organizing and reproducing their language and ways of being-in-the-world is, however, a Western liberal dialectical understanding of the events and their desire to be like their white counterparts, which stands against the anti-dialectical purposive rationality, which emerged out of the African/Haitian Epistemology, Vilokan/Haitian Idealism, of Boukman Dutty, Cecile Fatiman, the rest of the maroon Africans who congregated for the Petwo Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman/ Bwa Kayiman. The difference between what the Africans at Bois Caïman wanted and the aspirations of the mulattoes or Affranchis can be summed up through a parallel or complimentary analysis of the dialectical master/slave relationship of the black American experience with their white masters in America [17-31].

Using a structurationist approach to practical consciousness constitution, what Paul C Mocombe [6] calls phenomenological structuralism, this work compares and contrasts the purposive rationality of the black American civil rights movement with that of the originating moments of the ceremony of Bois Caiman. In keeping with the tenets of phenomenological structuralism, the emphasis is on the ideals of structures that social actors internalize and recursively organize and reproduce as their praxis in the material world. In this case, the argument is that two distinct forms of system and social integration would characterize black American and Haitian life, which made their approaches to slavery and colonialism totally distinct: dialectical on the one hand; and antidialectical on the other [31-48].

Theory and Method

Beginning in the sixteenth century, Africans were introduced into the emerging global Protestant capitalist world social structure as slaves. Given their economic material conditions, their African practical consciousnesses, i.e., bodies, languages, ideologies, etc., were dialectically represented by European whites as primitive forms of being-in-the-world to that of the dominant white Protestant bourgeois social order with the ever-declining significance of Catholicism following the Protestant Reformation [7]. From this sociohistorical perspective, under the “contradictory principles of marginality and integration” [7] the majority of African consciousness in America especially was reshaped as a “racial classin- itself” (blacks), a “caste in class,” forced to embody the structural terms (bourgeois ideals in the guise of the protestant ethic) of the dominant global (capitalist) social relations of production, over all other “alternative” African adaptive responses to its then organizational form, slavery [48-64].

This embodiment or internalization of bourgeois ideals, in the guise of the Protestant Ethic, by the majority of Africans in America amidst their poor material conditions created by the social relations of Protestant capitalist organization, in keeping with traditional readings of the black American struggle for freedom, eventually made the struggle to obtain equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition with their white Protestant bourgeois counterparts amidst racial and class discrimination their goal. This goal, brilliantly captured by W.E.B. Du Bois in his work The Souls of Black Folk, progressively crept into their African based spiritualism, which dialectically subsequently became synthesized with the Protestant Ethic of the global capitalist Protestant social structure leading to the ever-increasing materialization of black American faiths and practical consciousness along the lines of their former white slave masters. Hence, the subsequent aim of the majority of black Americans, as embodied in the black American civil rights movement, became a movement for equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition led by liberal black Protestant bourgeois male preachers (hybrid simulacrum of their white colonizers) like Martin Luther King Jr. against alternative responses to enslavement by convicting the society of not identifying with their norms and values, which black Americans embodied and recursively organized and reproduced in their practices [8].

Conversely, the Haitian Revolution as initiated on August 14th, 1791 at Bois Caïman by Boukman Dutty and Mambo Cecile Fatiman was led by various representatives of African nations seeking to recursively reorganize and reproduce their African practicalconsciousness/ thesis, the Vodou Ethic and the spirit of communism, which emerges out of their African ontology and epistemology, Vilokan/Haitian Idealism, in the world against the bourgeois liberalism of whites and the mulatto or Affranchis class of Haiti, who would subsequently, with the assassination of the houngan, Vodou priest, Jean-Jacques Dessalines in 1806, undermine that attempt for a more liberal purposive-rationale, similar to that of the black American civil-rights movement, that would reintroduce wage-slavery and peonage on the island [64-70].

Haitians celebrate Bois Caïman as the beginning of the Haitian Revolution in August of 1791. At Bois Caïman/Bwa Kay Iman (near Boukman’s house), the Jamaican-born houngan, Vodou priest, Boukman Dutty, initiated the Haitian Revolution on August 14, 1791 when he presided over a Petwo Vodou ceremony in Kreyol in the area, which is located in the mountainous Northern corridors of the island. Accompanied by a woman, the mambo Vodou priestess Cecile Fatiman, taken by the spirits of the lwa/loas, Ezili Danto/ Erzulie Danthor, they cut the throat of a black pig and had all the participants in attendance drink the blood. According to Haitian traditions, Boukman and the participants, via Boukman’s prayer, swore two things to the lwa Ezili Danto, the Goddess of the Haitian nation, present in Fatiman if she would grant them success in their quest for liberty against the French. First, they would never allow for inequality on the island; second, they would serve bondye/ Gran-Met (their good god) and its 401 manifestations, lwaes of Vodou and not the white man’s god “which inspires him with crime:”

Bon Dje ki fè la tè. Ki fè soley ki klere nou enro. Bon Dje ki soulve lanmè. Ki fè gronde loray. Bon Dje nou ki gen zorey pou tande. Ou ki kache nan niaj. Kap gade nou kote ou ye la. Ou we tout sa blan fè nou sibi. Dje blan yo mande krim. Bon Dje ki nan nou an vle byen fè. Bon Dje nou an ki si bon, ki si jis, li ordone vanjans. Se li kap kondui branou pou nou ranpote la viktwa. Se li kap ba nou asistans. Nou tout fet pou nou jete potre dje Blan yo ki swaf dlo lan zye. Koute vwa la libète k ap chante lan kè nou.

The god who created the sun which gives us light, who rouses the waves and rules the storm, though hidden in the clouds, he watches us. He sees all that the white man does. The god of the white man inspires him with crime, but our god calls upon us to do good works. Our god who is good to us orders us to revenge our wrongs. He will direct our arms and aid us. Throw away the symbol of the god of the whites who has so often caused us to weep, and listen to the voice of liberty, which speaks in the hearts of us all [71-75].

That night the slaves revolted first at Gallifet Plantation, then across the Northern Plains. Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines would join the rebellion after Boukman was captured and beheaded by the French. And as the proverbial saying goes, the rest is history. Under Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who crowned himself emperor for life, Haiti became the first free black nation-state in the world in 1804, the only successful slave rebellion in recorded history, the first democratic nation, and the second republic after the United States of America in the Western Hemisphere [75-79].

The centering of Vodou and Kreyol are the divergent paths against slavery and liberal bourgeois Protestantism that sets the originating moments of the Haitian Revolution apart, as a distinct phenomenon, from the desires and purposive-rationale of an elite liberal hybrid group, the mulatto elite and black petit-bourgeois class or Affranchis in Haiti and liberal black Protestant bourgeois male preachers of America, seeking to serve as the bearers of ideological and linguistic domination for the black masses in both countries by recursively (re) organizing and reproducing the agential moments of their former colonizers within the logical constraints of Hegel’s master/slave dialectic. To only highlight the latter, liberal bourgeois Protestant initiative, over the former, originating moments of the Haitian revolution, under the purview of a Hegelian master/slave universal dialectic, as so many theorists, including the work, Black Jacobins, of CLR James, and Susan Buck- Morss’s [4], Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History, is to deny the existence of the African practical-consciousness, Haitian Idealism as expressed through the Vodou Ethic and the spirit of communism, that has been seeking to institute its practical consciousness in the world since the beginning of the slave trade in favor of the liberal bourgeois Protestantism of whites and the mulatto and black petitbourgeois elites who have yet to be able to stamp out, as was done to the black American, the African linguistic system, Kreyol, and practical-consciousness, Vodou, of the Haitian masses, by which Haiti’s provinces have been constituted [79-90].

Discussion

As in the case of CLR James’s work, Black Jacobins, Susan Buck Morss [4] in her work, Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History attempts to understand the originating moments of the Haitian Revolution metaphorically through Hegel’s master/slave dialectic. Suggesting, in fact, that it is the case of Haiti that Hegel utilized to constitute the metaphor:

Given the facility with which this dialectic of lordship and bondage lends itself to such a reading, one wonders why the topic Hegel and Haiti has for so long been ignored. Not only have Hegel scholars failed to answer this question; they have failed, for the past two hundred years, even to ask it (2009, p. 56).

My position here is that James’s and Morss’s conclusions do not hold true for the Africans who met at Bois Caïman, and only holds true for the case of the Affranchis of Haiti-who usurped, following their assassination of Dessalines, the originating moments of the Revolution from the Africans who met at Bois Caïman-and the black Americans who, in choosing to rebel against their former masters, were not risking death to avoid subjugation, but in rebelling were choosing life in order to be like the master and subjugate.

In Hegel’s master/slave dialectic as Morss explains,

Hegel understands the position of the master in both political and economic terms. In the System der Sittlichkeit (1803): “The master is in possession of an overabundance of physical necessities generally, and the other [the slave] in the lack thereof.” At first consideration the master’s situation is “independent, and its essential nature is to be for itself”; whereas “the other,” the slave’s position, “is dependent, and its essence is life or existence for another.” The slave is characterized by the lack of recognition he receives. He is viewed as “a thing”; “thinghood” is the essence of slave consciousness-as it was the essence of his legal status under the Code Noir. But as the dialectic develops, the apparent dominance of the master reverses itself with his awareness that he is in fact totally dependent on the slave. One has only to collectivize the figure of the master in order to see the descriptive pertinence of Hegel’s analysis: the slaveholding class is indeed totally dependent on the institution of slavery for the “overabundance” that constitutes its wealth. This class is thus incapable of being the agent of historical progress without annihilating its own existence. But then the slaves (again, collectivizing the figure) achieve selfconsciousness by demonstrating that they are not things, not objects, but subjects who transform material nature. Hegel’s text becomes obscure and falls silent at this point of realization. But given the historical events that provided the context for The Phenomenology of Mind, the inference is clear. Those who once acquiesced to slavery demonstrate their humanity when they are willing to risk death rather than remain subjugated. The law (the Code Noir!) that acknowledges them merely as “a thing” can no longer be considered binding, although before, according to Hegel, it was the slave himself who was responsible for his lack of freedom by initially choosing life over liberty, mere self-preservation. In The Phenomenology of mind, Hegel insists that freedom cannot be granted to slaves from above. The self-liberation of the slave is required through a “trial by death”: “And it is solely by risking life that freedom is obtained…The individual, who has not staked his life, may, no doubt, be recognized as a Person [the agenda of the abolitionists!]; but he has not attained the truth of his recognition as an independent self-consciousness.” The goal of this liberation, out of slavery, cannot be subjugation of the master in turn, which would be merely to repeat the master’s “existential impasse,” but, rather, elimination of the institution of slavery altogether (53-56).

The Africans at Bois Caïman, given that they were already recursively reproducing their African practical consciousness in the maroon community of Bois Caïman away from the master/slave dialectic of whites neither cared for the master, nor his structuring metaphysics, but instead wanted to be free to exercise their African practical consciousness, which would be precarious, given the possibility of their re-enslavement if captured, by whites and the Affranchis, who also practiced slavery, remained on the island. In essence, the events at Bois Caïman represented an attempt by the Africans to exercise their already determining independent African self-consciousness against the whites and Affranchis’s dependent self-consciousness which sought to repeat the masters’ “existential impasse.” The liberal Affranchis and the black Americans, in other words, who would lead the civil rights movement, wanted, given that their very practical consciousness was determined by their relations to, and yearning to be like, their masters, rebelled in order to themselves be “free” masters and not an “independent self-consciousness.” In essence, the Affranchis, like their black American counterparts, merely rebelled in order to be like their masters, and sought neither to subjugate the master nor eliminate “the institution of slavery altogether,” since their consciousness as slaves was from the onset revealed to them only through the eyes of the master. Hence, the only other consciousness they had, outside of their slave consciousness, “thinghood,” was that of the master, whose position they desired, and that of the African masses whose practical consciousness they abhorred. But Boukman, Fatiman, and the other maroon Africans of Bois Caïman had their abhorred African Consciousness, which to revert to. The Affranchis, like their black American counterparts did not. Be that as it may, whereas the former sought to institute a new historical/universal, Absolute, order onto the material resource framework of Haiti by invoking the aid of their lwaes/loas to assist them in rooting out the whites and their gods, the latter, like their black American counterparts, wanted to maintain the status quo, the master/slave relationship by which their practical consciousness was constituted, in a national position of their own [91-116].

In other words, black Americans subjectified/objectified in the “Protestant Ethic and the spirit of capitalism” of American society were completely subjectified and subjugated on account of race and class position [8,9]. They were subjectified objects, i.e., slaves, things, whose initial practical consciousness prior to their enslavement was used dialectically by the master, by presenting the practical consciousness of the slave as backwards and damned within the metaphysics of the master’s practical consciousness, against the slave to objectify them as a thing. W.E.B Du Bois, for example, relying on the racial and national ideology of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century theoretically, en framed by Hegel’s master/slave dialectic, conceived of the ambivalence that arose in him as a self-conscious thing, as a result of the “class racism” (Étienne Balibar’s term) of American society, as a double consciousness: “two souls,” “two thoughts,” in the Negro whose aim is to merge these two thoughts into one distinct way of being, i.e., to be whole again [117-125].

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, -a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, -an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, -this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face. This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a coworker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powers and his latent genius [3].

This double-consciousness resulting from his thingness in relation to the master’s consciousness, Du Bois alludes to, in this famous passage of his work The Souls of Black Folk, is not a metaphor for the racial duality of black American life in America [8,9]. Instead, it speaks to Du Bois’s, as a black liberal bourgeois Protestant man, ambivalence about the society because it prevents him from exercising, not his initial African practical consciousness which is “looked on in amused contempt and pity,” but his true (master) American consciousness because of the society’s antiliberal and discriminatory practices, which made him a thing, i.e., slave. Although over time his “thinghood” forced Du Bois to adopt “pan-African communism” against his early beliefs in liberal bourgeois Protestantism, i.e., his desire to be like the masters, whites. Du Bois, in this passage, like the many black Americans who would share his class position and liberal bourgeois Protestant worldview, does not want an independent self-consciousness that is not the masters since the only other consciousness he is familiar with is that of the slaves, but simply wants to be like the collective dependent masters, whites, “without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.” His later pan-African communist message simply turns this desire, the attempt to be a master, into a desire to constitute the master/slave dialectic in a national position of his own. But contrary to this later “pan-African communist” message against assimilation for a nationalist position of his own, however, to make themselves whole the majority of black Americans of the civil rights movement, especially, did not yearn for or establish (by averting their gaze away from the eye of power or their white masters) a new independent object formation or totality, based on the initial “message” of their people prior to their encounter with the master, which spoke against racial and class stratification and would have produced heterogeneity into the American capitalist bourgeois world-system; instead, since there was no other “message” but that of the society which turned and represented the “original” African message of their people into inarticulate, animalistic backward gibberish, they (blacks) turned their gaze back upon the eye of power (through protest and success in their endeavors) for recognition as “speaking subjects” of the society seeking not to subjugate the master in a national position of their own but for equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition with their white counterparts. Power hesitantly responded by allowing some of them (the hybrid modern “other” liberal bourgeois Protestant) to partake in the order of things, which gave rise to the black American identity, the liberal black bourgeoisie or hybrids, which delimits the desired agential moments of the social structure for all blacks [8-13].

Thus black American protest as a structurally differentiated “class-in-itself” (subjectified/objectified thing) led by this liberal black bourgeoisie within the American protestant bourgeois master/slave order did not reconstitute American society, but integrated the black subjects, whose ideals and practices (acquired in ideological apparatuses, i.e., schools, law, churches (black and white)), as speaking subjects, were that of the larger society, i.e., the protestant ethic, into its exploitative and oppressive order-an order which promotes a debilitating performance principle actualized through calculating rationality, which may result in economic gain for its own sake for a few predestined individuals. The black American, like the early Du Bois of the Souls prior to his conversion to pan-African communism, in a word, became like their masters within the master/slave dialectic, which constituted their historical experiences.

The same can be said for the Affranchis of Haiti, who sought for equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition with their blanc counterparts at the expense of the agential initiatives of the Bois Caïman African participants. The Affranchis, like Toussaint, for example, who owned African slaves, rebelled not to eliminate slavery or subjugate the master, but to be a master, like their liberal black American counterparts, through their dialectical claim for equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition. Their slave status only revealed to them the “other” consciousness in the dialectic, i.e., the master consciousness. Therefore, their desire was not to be slaves, who had no other consciousness to look to but that of the newly arrived Africans and the maroon Africans, but masters who enslaved the other slaves, i.e., the newly arrived Africans and the marooned Africans, who were not like themselves. This desire of Toussaint, for example, to be like the master, however, was not the aim of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Boukman, Cecile Fatiman, and the other participants at Bois Caïman. The former, Affranchis, like their black American counterpart, wanted equality of opportunity and recognition from, and with, their former white masters by recursively organizing and reproducing their (the slave masters) liberal agential moments; the latter, Boukman, Fatiman, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and the Africans of Bois Caïman did not, but instead sought to anti-dialectically reify and practice their traditional African ways of life against the purposive-rationality of their former white masters. The slaves at Bois Caïman were already an independent self-consciousness in their maroon communities. They did not share in the “existential impasse” of their masters. The originating Vodou and Kreyol moments of the Revolution was an attempt to get rid of the whites and Affranchis, who desired to be whites, in order that they may recursively organize and reproduce their practical consciousness, not to be like their white masters as Toussaint and the rest of the Affranchis desired. That the Affranchis would come to direct the Revolution after the death of Dessalines October, 17th, 1806, would give rise to their purposive-rationality, their desire for equality of opportunity, distribution, and recognition within the global capitalist social structure, at the expense of the agential moments of Boukman, Fatiman, and the other participants of Bois Caïman who sought to anti-dialectically manifest their selfconsciousness onto the stage of history by evoking the aid of their own Gods to fight against the Gods and metaphysics of the whites and Affranchis who had adopted the purposive-rationality of their white masters [126-133].

Conclusion

Essentially, the Frankfurt school’s “Negative Dialectics” represents the means by which the Du Bois of The Souls, the majority of liberal bourgeois black Americans, and the Affranchis of Haiti confronted their historical situation. The difference between the “negative dialectics” of Du Bois of The Souls, the majority of liberal bourgeois black Americans, the Affranchis, and the discourse or purposive rationality of the enslaved Africans of Bois Caïman is subtle, but the consequences are enormously obvious. For the Frankfurt school, “[t]o proceed dialectically means to think in contradictions, for the sake of the contradiction once experienced in the thing, and against that contradiction. A contradiction in reality, it is a contradiction against reality” (Adorno, 1973 [1966]: 145). This is the ongoing dialectic they call “Negative Dialectics:”

Totality is to be opposed by convicting it of nonidentity with itself-of the nonidentity it denies, according to its own concept. Negative dialectics is thus tied to the supreme categories of identitarian philosophy as its point of departure. Thus, too, it remains false according to identitarian logic: it remains the thing against which it is conceived. It must correct itself in its critical course-a course affecting concepts which in negative dialectics are formally treated as if they came “first” for it, too (Adorno, 1973 [1966]: 147).

This position, as Adorno points out, is problematic in that the identitarian class convicting the totality of which it is apart remains the thing against which it is conceived. As in the case of black Americans and the Affranchis, their “negative dialectics,” their awareness of the contradictions of the heteronomous racial capitalist order did not foster a reconstitution of that order but a request that the order rid itself of a particular contradiction and allow their participation in the order, devoid of that particular contradiction, which prevented them from identifying with the Hegelian totality, i.e., that all men are created equal except the enslaved black American or the mulatto. The end result of this particular protest was in the reconfiguration of society (or the totality) in which those who exercised its reified consciousness, irrespective of skin-color, could partake in its order. In essence, the contradiction, as interpreted by the black Americans, and just the same the Affranchis, was not in the “pure” identity of the heteronomous order, which is reified as reality and existence as such, but in the praxis (as though praxis and structure are distinct) of the individuals, i.e., institutional regulators or power elites, who only allowed the participation of blacks within the order of things because they were “speaking subjects” (i.e., hybrids, who recursively organized and reproduced the agential moments of the social structure) as opposed to “silent natives” (i.e., the enslaved Africans of Bois Caïman). And herein rests the problem with attempting to reestablish an order simply based on what appears to be the contradictory practices of a reified consciousness. For in essence the totality is not “opposed by convicting it of nonidentity with itself-of the nonidentity it denies, according to its own concept,” but on the contrary, the particular is opposed by the constitutive subjects for not exercising its total identity. In the case of liberal black bourgeois America, the totality, American racial capitalist society, was opposed through a particularity, i.e., racism, which stood against their bourgeois identification with the whole. In such a case, the whole remains superior to its particularity, and it functions as such. The same holds true for the Affranchis of Haiti, but not for Boukman, the other participants of Bois Caïman, and Dessalines who went beyond the master/slave dialectic.

In order to go beyond this “mechanical” dichotomy, i.e., whole/part, subject/object, master/slave, universal/particular, society/individual, etc., by which society or more specifically the object formation of modernity up till this point in the human archaeological record has been constituted, so that society can be reconstituted wherein “Being” (Dasein, Martin Heidegger’s term) is nonsubjective and nonobjective, “organic” in the Habermasian sense, it is necessary, as Adorno points out, that the totality (which is not a “thing in itself”) be opposed, not however, as he sees it, “by convicting it of nonidentity with itself” as in the case of black America and the Affranchis or mulattoes, but by identifying it as a nonidentity identity that does not have the “natural right” to dictate identity in an absurd world with no inherent meaning or purpose except those which are constructed, via their bodies, language, ideology, and ideological apparatuses, by social actors operating within a reified sacred metaphysic. This is not what happened in black America or with the Affranchis or mulattoes of Haiti, but I am suggesting that this is what took place with the participants of Bois Caïman within the eighteenth century Enlightenment discourse of the whites and Affranchis.

The liberal black American and the Affranchis by identifying with the totality, which Adorno rightly argues is a result of the “universal rule of forms,” the idea that “a consciousness that feels impotent, that has lost confidence in its ability to change the institutions and their mental images, will reverse the conflict into identification with the aggressor” (Adorno, 1973 [1966], pg. 94), reconciled their double consciousness, i.e., the ambivalence that arises as a result of the conflict between subjectivity and forms (objectivity), by becoming “hybrid” Americans or mulattoes desiring to exercise the “pure” identity of the American and French totality and reject the contempt to which they were and are subject. The contradiction of slavery in the face of equality-the totality not identifying with itself-was seen as a manifestation of individual practices, since subjectively they were part of the totality, and not an absurd way of life inherent in the logic of the totality. Hence, their protest was against the practices of the totality, not the totality itself, since that would mean denouncing the consciousness that made them whole. On the contrary, Boukman, the participants at Bois Caïman, and Dessalines decentered or “convicted” the totality of French modernity not for not identifying with itself, but as an adverse “sacred-profaned” cultural possibility against their own “God-ordained” possibility (alternative object formation), Haitian/ Vilokan Idealism, which they were attempting to exercise in the world. This was the pact the participants of Bois Caïman made with their loas/lwa, Ezili Danto, when they swore to neither allow inequality on the island, nor worship the god’s of the whites “who has so often caused us to weep.” In fact, according to Haitian folklore, the lwa, Ezili Danto, who embodied Faitman, or Mambo Fatiman, descended from the heavens and joined the participants of Bois Caïman when they initially set-off to burn the plantations in 1791, but her tongue was subsequently removed by the other participants so that she would not reveal their secrets should she be captured by the whites. Haiti has never been able to live out this pact the participants of Bois Caïman made to Ezili Danto, given the liberal bourgeois Affranchis’s, backed by their former colonizers, America and France, claims to positions of economic and political power positions, which have resulted in the passage of modern rules and laws grounded in the Protestant Ethic and the spirit of capitalism that have caused the majority of the people to weep in dire poverty as wage-laborers in an American dominated Protestant postindustrial capitalist world-system wherein the African masses are constantly being forced via ideological apparatuses such as Protestant missionary churches, industrial parks, tourism, and athletics, for examples, to adopt the liberal bourgeois Protestant ethos of the Affranchis and the black Americans against the Vodou ideology and its ideological apparatuses.

For more Archaeological Sciences Journals please click on below linkhttps://lupinepublishers.com/anthropological-and-archaeological-sciences/index.php

For more Lupine Publishers Please click on below link https://lupinepublishers.com/

#journal of archaeological sciences#Journal of anthropological research#Journal of Anthropological and Archaeological Sciences#Lupine Publishers#Lupine Publishers Group#JAAS

0 notes

Photo

Dutty Boukman was a Jamaican, self-educated slave. He is known for his inspirational speech which lead to the Haiti Revolution. He was a member of the Assassin Brotherhood in Saint-Domingue. England saw Boukman as a threat for teaching other slaves to read, so the sold him to the French(Haiti). Around August 14, 1791, Boukman presides over a ceremony at Bois Caiman with Cecile Fatiman. He prophesied Jean Francois, Biassou and Jeannot would lead a revolt which would free the slaves in Saint-Domingue. Boukman told the audience to take revenge on the French oppressors and cast away their image of God. One week later, 1800 plantations were destroyed and 1000 slave owners killed. https://www.instagram.com/p/B8rqNbtgKAS/?igshid=td8d2x76bpti

0 notes

Photo

🇭🇹🎤📚 ��� #TheBlackRevolutionaryBookTour @thorobredbooks x @meccaakagrimo • 📆 Sunday: January 27th @7pm @kasachampet @cityofmiramar 720 Pines Blvd Pembroke Pines, FL 33024 Join Us as we welcome the author of several publications, “Haiti: The First Black Republic and Makandal: The Black Messiah” - Frantz Derenoncourt, Jr. @thorobredbooks • 📚 Frantz will be presenting his newest release BOUKMAN and CECILE FATIMAN: BLACK REVOLUTION telling the story of the Bwa Kayiman ceremony and initial slave revolts of The Haitian Revolution #AyisyenRevolution • 🎤 #MeccaGrimo will be performing Spoken Word Poetry from his Long Awaited #AyitiWasBornInMe project #HaitiWasBornInMe • 🇭🇹📚 #BookSigning #Poetry #PoeticLakay #PoeticLakayPoets #ThoroBredBooks #BookTour #LittleHaiti #TiAyiti #LakaySeLakay #EritajAyisyen (at Kasa Champet Restaurant & Lounge) https://www.instagram.com/p/BtJsO80FF_b/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=hexs0xdwg8th

#theblackrevolutionarybooktour#ayisyenrevolution#meccagrimo#ayitiwasborninme#haitiwasborninme#booksigning#poetry#poeticlakay#poeticlakaypoets#thorobredbooks#booktour#littlehaiti#tiayiti#lakayselakay#eritajayisyen

0 notes

Text

LADY LOVE [1][2][3]

Real World Inspiration, Potential Flaws / Alternative Concepts, Trivia

As a warning, this section includes discussion of domestic violence, including murder. It also includes discussion of homophobic and transphobic violence in Haiti, including murders and corrective rape.

REAL WORLD INSPIRATION

Pictured: Erzulie Dantor, by Andre Pierre

Lady Love was inspired by the Haitian lwa Ezili Dantò.

“La Reine des Reines”–Ezili Dantò–is the Divine Mother and Queen of the Petro rite, who some refer to as the Patron of Haiti itself.

Mama Lola described Ezili Dantò in the following terms[1]:

“Let me talk about lwa Dantò…Lwa Dantò is an Ezili, a black woman. She has two scars on her face… When I see her in my sleep, she is always a beautiful black woman. She is a lwa who is very tough too. Li tre tough [She is very tough]. A spirit who is hard. But she is a good lwa…she is!”

As rivals, Ezili Freda and Ezili Dantò emblematize the social conditions of the Haitian woman. Where Ezili Freda is the light-skinned beauty who embodies what the poor dream of having, Ezili Dantò is the dark-skinned beauty who captures the poor womans’ realities, taking her everyday hardships and making them sacred[2]. The struggles of menial labor, violence from abusive men, and the trials of motherhood are all burdens she shoulders with these women.

A song sung for Ezili Dantò connects her to the bloody death of a woman killed in an act of domestic violence[3]:

Di ye!

Set kou’d kouto, set kou'd ponya.

Prete’m terinn-nan, m'al vomi san ye.

Set kou’d kouto, set kou’d ponya.

Prete’m terinn-nan, m'al vomi san ye. [repeat]

Men san màke pou li.

Set kou’d kouto, set kou'd ponya.

Prete’m terinn-nan, m’al vomt san ye.

Mwen di ye, m’pral vomi san, se vre.

Set kou'd kouto, set kou’d ponya.

Prete’m terinn-nan, m’al vomi san ye. [repeat]

San m’ape koule, Danto, m'pral vomi san ye.

San m’ape koule, Ezili, m’pral vomi san ye.

San mwen ape koule, Je Wouj, ou pral vomi san ye.

Say hey!

Seven stabs of the knife, seven stabs of the sword.

Hand me that basin, I’m going to vomit blood.

Seven stabs of the knife, seven stabs of the sword.

Hand me that basin, I’m going to vomit blood. [repeat]

But the blood is marked for him.

Seven stabs of the knife, seven stabs of the sword.

Hand me that basin, I’m going to vomit blood.

I say hey! I’m going to vomit blood, it’s true.

Seven stabs of the knife, seven stabs of the sword.

Hand me that basin, I’m going to vomit blood. [repeat]

My blood is flowing, Danto, I’m going to vomit blood.

My blood is flowing, Ezili, I’m going to vomit blood.

My blood is flowing, Red-Eyes, you’re going to vomit blood.

It is these very women who she empowers and protects. Paul C. Mocombe describes EziliDantò as “the protector lwa of women, children, homosexuals, and lesbians”[4]. According to Mocombe, she symbolizes the concepts of “maternal love”, “mistrust”, “androgyny”, and “lesbianism” in Vodou belief[5].

Pictured: Petwo Ceremony Commemorating Bwa Kayiman, 1950, by Castera Bazile

Special attention is given to the worship of Ezili Dantò, due to her role in the Haitian Revolution. In a popular account of Bwa Kayiman, it is said that Manbo Cecile Fatiman was “mounted” (possessed) by Ezili Dantò, who had been summoned by the sacrifice of the black pig[6][7]. In doing so, the Haitian people were empowered by the lwa to revolt against their enslavers.

Pictured: Slave Uprising, by Ulrick Jean-Pierre

From Karen McCarthy Brown’s interview with Maggie, the daughter of Mama Lola[8]: