#German verb. adjective in German

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Day 12 _ Adjectives in German Language

First as always let’s learn the vocabulary and verbs with imaging technique with the INGOAMPT APP : Check this INGOAMPT WITH 1000 FLASHCARDS iOS app in Apple Store

0 notes

Text

Managed to translate the simplest german phrase ever and I'm sooooo proud of myself

#literally pronoun adjective noun verb and uh victim i guess#so so simple but i was so bad at german I'm still taking this as a victory

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

discovered ‘is’ was a verb yesterday when doing german

#it was using ‘weil’ and i didn’t realise is was a verb#‘weil’ is ‘because’ but it messes up the word order unlike ‘denn’ (which is also because)#so instead of ‘denn es ist schwer’ (conjunction pronoun verb adjective) (because it is difficult)#it can be ‘weil es schwer ist’ (conjunction pronoun adjective verb) (because it difficult is)#german language#zad talks

0 notes

Text

DIE DOPPELTE VERNEINUNG: How to double-negate a sentence in German

It is true that negation is an act of refusal, rejection or denial but what is more true is that when it is done twice in one sentence, it becomes an approval or a yes. Find out how! Content in this post1. The meaning of doppelte Verneinung2. Doppelte Verneinung with adjectives3. Doppelte Verneinung with adverbs4. Doppelte Verneinung with prepositions5. Doppelte Verneinung with nouns6. Doppelte…

View On WordPress

#Bejahung#Bejahung von zwei Verneinungen#doppelte Verneinung#doppelte Verneinung with nicht#german Double negation#negation in German#negative German adjectives#negative German adverbs#negative German nouns#negative German prepositions#negative German pronouns#Negative German verbs#Verneinung mit Nomen

0 notes

Text

So an interesting thing about Latin is that the word for "sword" is "gladius" and the word for "scabbard" is "vagina".

But here's the weird thing: in classical times, "gladius" was used as a slang word for "penis", but "vagina" was not used as a slang word for "vagina"!

The weird thing is that their term for the "vagina" was "vulva". Now... I'm not being lazy here and meaning the internal and external genitals as "vagina": when they said "vulva", they only meant the internal genitals. They even called the womb "vulva".

Anyways. For the external genitals, what we now would say "vulva" for, they'd use... "cunnus", probably? That's a vulgar word, I'm not even sure what you'd use if you weren't trying to be derogatory.

Although it's amusing to find out that "cunnus" isn't related to "cunt" or "cunny" at all. "cunt" comes from Proto-Germanic (where it meant the same, just not vulgar), and "cunny" goes back to a different Proto-Germanic word that meant "to know".

Anyway the worst Latin-dervived term for female genitalia is "pudendum/pudenda", because it was directly taken from medieval (I believe?) Latin where it meant the same, but if you know latin you can also translate it to which it means: "that whereof one ought to feel shame". Yeah, it's off the verb "pudeō/pudēro": "to shame". Fucking yikes.

And along those lines, reportedly a roman slang term for the female genitalia was "culpa", which means a fault or defect. Yikes again.

The final bit of weirdness is that "genitalia" is also a Latin word: but it doesn't mean the genitals, not specifically. It's instead a neutral plural for an adjective that means "related to birth or production".

So yeah. It's weird that English has so many Latin roots and then a fuck ton of weird false-friends in this area. I've heard that some of this is because of medieval renaming to move away from more sexualized terms (that's actually how we got the term "penis", which is a latin word meaning "tail"), but I can't completely verify that.

All this is on top of the consistent thing where English has that fun thing where we often have two words for something, and the one with Germanic roots will be vulgar, and the one with Latin roots will be formal. Fucking is vulgar, copulation is formal. Rude germanic barbarians shit, refined roman citizens defecate. the germanic peasants raise a cow , but when the anglo-saxon upperclass see it on their plate, it's beef.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Types of Adjectives

Adjectives - words that modify nouns and pronouns.

There are 13 categories of adjectives that describe the different ways adjectives can be used in the English language.

Descriptive Adjectives

Describe the characteristics, traits, or qualities of a noun or pronoun.

In English, they often are placed directly before the noun they are describing.

For example: Excited children ate delicious treats in the colorful cafeteria.

EXAMPLES of descriptive adjectives: beautiful, witty, wicked, confusing, rich, new, strange, rocky, circular, helpful, competent, smelly, stable, grumpy, devoted, smart, muscular, graceful, scary, safe, wooden, sleepy, tardy, hungry, strange, hopeful, proud, new, dainty, royal, arrogant, round, efficient, youthful, cumbersome, fickle, mild, expensive, small, rude, generous, courageous, zany, thin, round, oval, dark, hot, modern, petite, weary

Compound Adjectives

Formed from multiple words, which are usually connected by hyphens.

For example: We all enjoyed some ice-cold sodas.

EXAMPLES of compound adjectives: old-fashioned, run-of-the-mill, middle-of-the-road, heavy-duty, happy-go-lucky, see-through, easy-going, big-time, long-term

Comparative Adjectives

Used to compare two different people or things to each other.

Most comparative adjectives in English end in "-er".

In other instances, they are denoted with "more".

For example: My brother is stronger than yours.

EXAMPLES of comparative adjectives: better, bigger, older, angrier, prettier, smarter, kinder, more determined, more interesting

Superlative Adjectives

Used to compare more than two people or things by indicating which one is the most supreme or extreme.

Most superlative adjectives in English end in "-est".

In other instances, they are denoted with "most" or "least".

For example: I thought she was the most creative artist on the planet.

EXAMPLES of superlative adjectives: best, biggest, oldest, prettiest, happiest, most striking

Proper Adjectives

Formed from proper nouns.

For example: At the grocery store, we bought Mexican tortillas, German sausage, and French cheese.

There are some proper adjectives that are based on people and places that may not be capitalized if they are used as more general words, such as herculean.

EXAMPLES of proper adjectives: Viennese, Russian, Orwellian, Shakespearean, spartan, draconian, titanic

Participial Adjectives

Based on participles, which are words that usually end in "-ed" or "-ing" and derive from verbs.

For example: The frightened students ran away from the terrifying clown.

EXAMPLES of participial adjectives: burnt, depressed, surprised, misunderstood, annoying, shocking, time-consuming

Distributive Adjectives

Used to refer to members of a group individually.

For example: Both of the team captains took the time to congratulate every member of the team.

EXAMPLES of distributive adjectives: each, either, neither, any

Limiting Adjectives

Restrict a noun or pronoun rather than describe any of its characteristics or qualities.

For example: The building had twelve floors, hundreds of windows, and several unique features.

EXAMPLES of limiting adjectives: a/an, some, few, dozen, eight, thousands

Possessive Adjectives

Used to express possession or ownership.

For example: Everyone brought their own dish and my mom made her famous punch for our potluck.

EXAMPLES of possessive adjectives: your, our, its, his

Interrogative Adjectives

There are only 3 interrogative adjectives in English.

They are used to ask questions.

For example: What is the fastest way to get this done?

The 3 interrogative adjectives are: what, which, whose

Demonstrative Adjectives

Used to express relative positions in space and time.

For example: I think that color looks great on you, but this one matches those shoes better.

The 4 most commonly used demonstrative adjectives in English are: this, that, these, those

Adjectives can be in different categories depending on how they are used in a sentence:

Attributive Adjectives

Many descriptive adjectives are commonly used as attributive adjectives.

Usually directly next to the noun and pronoun that they modify.

These sentences all use attributive adjectives:

The sleepy dogs dozed on the doorstep.

A tardy student ran in as the bell rang.

We fed the hungry cat.

The strange figures appeared in the mist.

Her hopeful eyes gazed at me.

Predicate Adjectives

Some of the same descriptive adjectives that were used as attributive adjectives above can also be used as predicate adjectives.

Appear in the predicate of a sentence as a subject complement rather than directly next to the nouns or pronouns that they modify.

Predicate adjectives follow linking verbs in sentences and clauses.

These sentences all use predicate adjectives:

They are asleep.

I arrived late to work.

She felt hungry.

The figures seemed strange.

The children looked hopeful.

Source ⚜ More: Writing Notes & References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#adjective#writeblr#grammar#studyblr#langblr#linguistics#dark academia#vocabulary#light academia#writing prompt#literature#poetry#writers on tumblr#poets on tumblr#writing reference#spilled ink#creative writing#fiction#novel#words#writing resources

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

The plural -s ending forming a noun out of an adjective is a fun little corner case in English morphology. "Politics" is explicitly patterned after Aristotle's τά πολῑτῐκᾱ́, "affairs of the state." "Mathematics" is from Latin mathematica, which is singular. "Physics" is attested as "physic" in older English, which conforms with its singular declension in Greek φυσική. I'm assuming this affix develops out of the truncation of a noun phrase, or the use of adjectives as substantives? Like, "Which candy do you like? I like red ones, I like the reds," type constructions. But it's fun that in the development of the -ics ending there's an English construction that's used in a way frequently parallel to the Greek derived -ology, or the older Germanic -craft. Seems especially suitable for big, complex fields like mathematics that have lots of subfields. Like, there's more than one mathematic! That makes a lot of sense to me. Though I guess American verbal agreement patterns still prefer a singular verb here, in contrast to the Commonwealth usage.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scary scary German syntax... right?

The following sentence exhibits a typical mistake German-learners make: Heute ich gehe in ein Museum.

It's not conjugation ("ich gehe" is correct!), it's not declension ("ein Museum" is correct too!). The issue is "heute ich gehe". Correct would be: Heute gehe ich in ein Museum (or: Ich gehe heute in ein Museum.)

What's the rule here?

It's unfortunately not simply "there can only be one word before the verb"

German word order is so difficult be cause it is so variable. All following sentences are correct and synoymous (though emphasis shifts):

Der Opa schenkt seiner Enkelin zum Geburtstag ein Buch über Autos.

Seiner Enkelin schenkt der Opa zum Geburtstag ein Buch über Autos.

Ein Buch über Autos schenkt der Opa seiner Enkelin zum Geburtstag.

Zum Geburtstag schenkt der Opa seiner Enkelin ein Buch über Autos. All mean: The grandfather gifts his niece a book about cars for her birthday.

What do they all have in common, syntax-wise? There's only one phrase in front of the finite verb. What does this mean? A phrase is a completed (!) unit that can consist of one or more words (depending on the word class (-> noun, verb, …)) Typical word classes that can be a phrase with just one word are:

Proper nouns, plural nouns, personal pronouns, relative pronous (Lukas kocht. Busse fahren. Ich schreibe. Der Mann, der kocht, …)

Adverbs (Heute, Morgen, Bald, Dort, Darum, …) Most other word classes need additional words to form a full phrase:

adjectives need a noun and article: der blaue Ball, der freundliche Nachbar

nouns need a determiner (= article): der Mann, eine Frau, das Nachbarskind

prepositions need… stuff (often a noun phrase): auf der Mauer, in dem Glas, bei der Statue

…

A finite verb is the verb that has been changed (=conjugated) according to person, time, … All verbs that are NOT infinitive or participles are finite. ich sagte -> "sagte" is the finite verb ich bin gegangen -> "bin" is the finite verb The infinitive and the participle are called "infinite verbs" and are always pushed towards the end (but not always the very end!) of the sentence: Ich bin schon früher nach Hause gegangen als meine Freunde.

So: Before the verb (that is not the participle or infinitive) there can only be one phrase.

Since "heute" is an adverb (-> forms a full phrase on its own) and "ich" is a personal pronoun (-> forms a full phrase on its own), they can't both be in front of the verb "gehe" You have to push one of them behind the verb: Heute gehe ich in ein Museum Ich gehe heute in ein Museum.

Both of these are main clauses (Ger.: Hauptsätze), which in German exhibit "V-2 Stellung", meaning the finite verb is in the second position (after one phrase).

What happens if we push all phrases behind the finite verb?

Gehe ich heute in ein Museum? (Watch out: Gehe heute ich in ein Museum would be ungrammatical! The subject has to come in the second position)

It's a question now!

In German, question sentences (that do not start with a question word like "Was?", "Wo?", …) start with the finite verb (called "V-1 Stellung").

Questions, main clauses,… what's missing?

Dependent clauses!

The third type of sentence exhibits "V-letzt Stellung" or "V-End Stellung", meaning the finite verb is at the very end of the sentence. Ich bin gestern in ein Museum gegangen, … main clause -> V-2 Stellung … weil es dort eine interessante Ausstellung gab. dependent clause -> V-letzt Stellung If you want to practice this....

... determine if the following German sentences are correct. If not, what would be the right way to say it?

Der Zug war sehr voll.

Gestern ich war in der Schule.

Die Lehrerin mich nicht hat korrigiert.

Gehst du heute zur Arbeit?

Das Buch ich finde nicht sehr interessant.

To practice this further, translate the following sentences into German and focus on the order of words:

The boy gave the ball back to me.

I called my girlfriend because I missed her.

The girl saw her brother at the train station.

The horse, which was standing on the field, was white and black.

#it's definitely not easy#but you can totally learn it!#maybe you'll notice it from now on#don't worry if you still get it wrong though#that's completely normal#and you'll still be understood#being understood is the main goal of learning a language!#german#learning german#langblr#german langblr#deutsch lernen#deutsch#language learning#german language#german learning#language#german grammar

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waste, vast, devastate, gastar, wüst, woestijn

The English words (to) waste, vast, and to devastate are all etymologically related. They come from the Latin adjective vāstus (desolate) and the verb (dē)vāstāre (to lay waste). More distantly, they're related to Spanish gastar (to spend), German wüst (desolate; chaotic), and Dutch woestijn (desert). The infographic shows how.

Latin vāstāre should have produced forms with a /v/ in Romance. The fact that they start with /g/ instead points to Germanic influences. When a Germanic word starting with /w/ was borrowed into Romance, this became /gw/ in most languages, which later became /g/ in some of them. Compare *want (glove) > Spanish guante, Italian guanto, French gant, and *Willjahelm > Guillermo, Guglielmo, Guillaume.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#dutch#german#spanish#catalan#portuguese#low saxon#brabantian#limburgish#italian#frisian#romanian#lingblr#proto-germanic

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some funny German words that are kind of hard to translate that are also not from the lexicon of obscure sorrows:

- Eigenart, Die. (Noun) Lit: the own-kind, meaning: Quirk

Usage example: "Ach, das ist dem seine Eigenart." (Oh, that's his quirk)

- Verschlimmbessern. (Verb) Lit: Worse-improving, meaning: trying to make something better, but making it worse in the process

Usage example: "Verschlimmbessern kann der gut." (He's great at making things worse while trying to make them better.)

- Sturmfrei. (Adjective) Lit: Storm free, meaning: having the house to yourself because your parents are away

Usage example: "Ich hab das ganze Wochenende sturmfrei." (I have the house to myself the whole weekend)

- Ohrwurm, Der. (Noun) Lit: Ear Worm, meaning: a song you can't get out of your head

Usage example: "Das Lied ist seit drei Tagen mein Ohrwurm." (That song has been playing on repeat in my head for three days)

- Schnapsidee, Die. (Noun) Lit: alcohol idea, meaning: An idea so stupid it could only have come from someone drunk.

Usage example: "Du weißt schon, dass das 'ne Schnapsidee ist?" (You do know that this is a stupid idea?)

- Treppenwitz, Der. (Noun) Lit: Staircase joke, meaning: coming up with a perfect reply for a joke or argument too late for it to be any use

Usage example: "Ich hätte in der Prüfung viel besser sein können, wenn mir die besten Ideen nicht erst als Treppenwitze gekommen wären." (I could have been much better in the exam if I hadn't thought of my best ideas afterwards while on the stairs.)

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok but what if like. Plasma or some other secondary element that doesn't get much narrative focus has, like, a tree/chutespeak-style dialect, but instead of being like simple combinations of adjective-noun or two synonyms or whatever, it's like a comically exaggerated version of how German works, where they just slap like eight different nouns, adjectives and verbs together to make unwieldy compound words.

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, do you know any strategies for learning the gender of German words? I'm Italian and I know Latin and Greek, so I'm not foreign to the concept of gendered words, I just find that German words give very little help to guess if they are feminine, masculine or neutral.

Thanks a lot and have a good time being a TA

Hallo! We just tell our students to memorise the genders but there are actually some general patterns! This isn't foolproof though because there are always exceptions in German:

Masculine: male people/jobs, days/months/seasons and most times of day (except for night), cars and trains, nouns derived from verbs without ending, a lot of nouns ending in –ant, –ling, –ner, –or, –m, –en, –er, –ismus, -ast, -ich, -ig,

Feminine: female people/jobs, numbers, ships and motorcycles, a lot of nouns derived from verbs ending in -t, lots of nouns ending in –heit, –keit, –ik, –schaft, –ur, –ität, –ung, –e, –ei, –enz, –ie, –ion, –anz, –in

Neuter: diminutives in -chen and -lein, colours, a lot of nouns starting in ge-, nouns derived from infinitives and adjectives, letters of the alphabet, a lot of English loan words, most fractions, a lot of nouns ending in –ment, –nis, –o, –um, –tum, -icht, -ma, -sal

Again: for every rule in German there's usually more exceptions. Mark Twain wrote an entire essay about this. We even have words where no one can agree on the correct article (like Nutella) or where several are correct.

Compound words take the article of the last noun eg die Armbanduhr because it's die Uhr even though it's der Arm and das Band.

The good news is that even if you get it wrong people will generally understand you.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word changes...

All of the following is IMO, so YMMV. :->

*****

Anyone noticed how "weaponry" is used nowadays in places where "weapons" would work just fine (and is often more correct)?

Yes, they ARE interchangeable, sort-of, but it's clunky and sounds to me either slightly journo-pompous or like a failure to remember the right word so plugging the most similar one into its place.

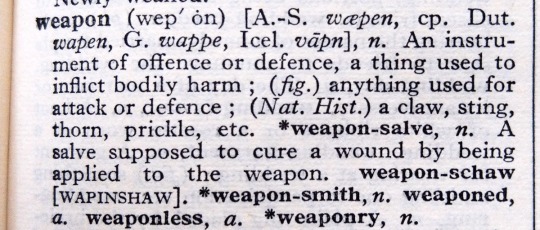

ETA: I checked one of my dictionaries, and while "weapons" is more modern, "weaponry" is an obsolete word which has come back into favour. I wonder why...?

*****

"Decimate" turns up all the time, usually when the correct word is "devastate".

Merriam-Webster says: "It's totally fine to use 'decimate' as a synonym for 'devastate'. This is why."

Beg to differ.

As the M-W article points out, "decimate" originally meant a Roman military punishment applied to one man in ten of a guilty unit. (Initially execution, but this had a rotten effect on unit morale, so it was reduced in severity to fatigues, extra drill or restricted rations.)

That's now considered a far too specific meaning and only linguistic pedants dig their heels in. Quite right too, and I speak here as a (bit of a) linguistic pedant...

However, it remains a useful word for more generalised incomplete destruction of living things - saying a regiment, flock, herd or population was "decimated" implies there are some survivors without quibbling over how many tenths. If totally wiped out, however, that's when words like "destroyed" or "obliterated" are more appropriate.

On the other hand something inanimate like a factory, city or region would be "devastated" - and in addition, saying someone is emotionally devastated is understandable, but saying they're emotionally decimated is peculiar.

Two words, several meanings.

It's like cutlery: a spork can replace knife, fork and spoon, but individual utensils give a lot more precision and variation of use.

*****

There are also a couple of real howlers, not just transposed words but actual errors.

One I've heard several times is using "siege" (a noun, or thing) instead of "besiege" (a verb, or action).

For reference, there's a term called noun-verbing, and the practice is quite old: "table the motion / pencil you in / butter him up / he tasks me", but all are either when there isn't already a verb-form of the word, or as a more picturesque way of saying something.

(Interesting side-note about "table the motion": in US English, it means "to postpone discussion" while in UK, CA and I think AU English, it means the complete opposite, "to begin discussion". Why there's this difference, I have no idea, but it's worth remembering as a Brit-fix when writing, also in a real-life business context.)

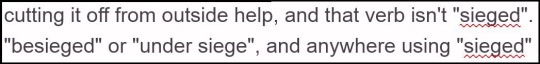

There IS an existing verb for the action of surrounding a castle and cutting it off from outside help, and that verb isn't "sieged". It's "besieged" or "under siege". Anywhere using "sieged" as a verb is wrong. The Firefox spellchecker in Tumblr Edit Mode is telling me it's wrong right now.

Merriam-Webster, I'm looking at you again.

*****

There's also "coronate" used as a verb. "The King was coronated at Westminster Abbey". Nope. He was CROWNED.

Coronate is an adjective (meaning crown-shaped) and was coined in in the 1600s by a botanist, as a word to describe the shape of certain plants.

The current Royal-associated usage seems to be a bastard back-formation from "coronation", because the act of putting on a crown is the verb "to crown".

This is almost identical in German, French, Italian and Spanish, with noun and verb the same. The only difference is that their verbs have, what a surprise, verb-endings (-en, -er, -re and -ar) on the noun while English does not.

Because English doesn't like to make things that easy...

"Coronated" might be people trying to sound archaic, or those who've bought into the dopey "said-is-dead" school, who perform any linguistic contortion to avoid common words, and who've been taught that repetition in a sentence - "crowned with a crown" - is BAD.

Is "coronated at a coronation" in some way better?

Guess what's got uncritical examples...

If that's M-W scholarship, I'll stick to the OED and my old but utterly reliable New Elizabethan Dictionary, thanks very much.

*****

Language is funny: sometimes funny ha-ha, sometimes funny annoying, but often just funny peculiar, because English etc. etc...

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

FIRST OFF! I DO NOT HAVE A DEGREE IN LINGUISTICS. I AM PLANNING ON TAKING IT AGAIN NEXT YEAR AND MAKING MY THESIS ON IT! SO BE AWARE I MIGHT NOT BE SUPER ACCURATE AND GET INFORMATION FROM PEOPLE WHO HAVE STUDIED THE FIELD FOR A LONG TIME.

imagine, a party. And these parties. The languages way of making a sentence would all have different dancing styles. Pronouns being breakdance, nouns being popping, adjectives being ballet, verbs being swing. And all the little fixes are salsa.

Analytical - most commonly found in Chinese, Vietnamese, afrikaans, and English (to a minor degree). If these languages were to dance. All of the words would stand on its own doing its little thing. In Chinese, when you are saying “I would like an apple juice” it’s 我想喝一个苹果汁 wǒ xiǎng hē yī gè píngguǒ zhī. (Note. This is a rough translation from the internet I do not speak Chinese, if you speak the language feel free to correct me) Every word is isolated and doing their own little style

fusional - most commonly found in most indo European languages. Especially in romance and germanic. If these languages were to dance. The popping (nouns) crew would be most likely together. Plus the suffixes would join to make a sort of popping salsa fusion. In Swedish, the sentence “the girls are drinking orange juice” is “flickorna dricker apelsinjuice”. A noun can easily add on another noun and a verb can add a suffix. Plus these languages are also know to conjugate a lot more. Spanish is great example of this too. Where Spanish have 3 different ways to tell about the past.

agglutinative languages - most commonly found in Turkic (Turkish and Kazakh) and Uralic languages (Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian) and Korean is also an agglutinative language. If these languages were dancing, it would be a conga line, In Finnish, the phrase “on my table” is pöydälläni. They can add more words to change the meaning (I am not good at understanding agglutinative languages, if you speak one please feel free to chime in)

Polysynthetic - most commonly found in Inuit languages like Greenlandic. These languages are doing acro dance. I found this example from the learn Greenlandic blog! The sentence “they are going to our church” is Oqaluffitsinnukarpoq. The blog goes more into detail about this

And that’s it of my linguistics info dumping!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

last night I dreamt I was in a fantasy world but like modern day and I attended a class on orcish where they summarized orcish sentence structure; and it was like this

[context marker] [adjective] [noun] [verb] [adverb]

The context marker was a unique particle that usually determined 1) how formal the conversation was and 2) how much you respected the interlocutor. It would also mark the sphere of life the sentence was used in: family, friends, servitude, combat, etc. The example the native teacher* gave was honorable v. dishonorable- it would change the whole meaning because you’d basically start every sentence saying wether you respected one, two, or all the people around.

As for verbs, it turned out orcish didn’t have verb tenses. Whether an action was performed in the past, present, or future, and punctually or continuously, had to be deduced through a specific category of adverb called “time adverbs”. There also was no distinction between pronouns: like in toki pona, there was only one first person pronoun for both plural and singular, one second person pronoun, and one third person pronoun. No possessives, either. So instead of saying “I went to the beach yesterday” you had to say “I go to the beach yesterday once”, and “my beach ball is round” would turn into “beach ball *of I* is round”.

After explaining this, the teacher commented that this was the reason orcs with a superficial knowledge of human languages, particularly Germanic languages, struggled speaking English and sounded “broken” even if they had a good grip on the vocabulary.

*I never once saw the teacher (dream logic) but I was 100% sure he was an orc. I also remember he encouraged us to translate sentences on a whiteboard and would kindly correct tilde usage.

#doc talks#let me tell you as a Spaniard I was SO RELIEVED but also so vexed at the no verb tenses thing…#I know that’s something a lot of natural languages have but it still threw me in for a loop#if you’re wondering what sort of vocabulary orcish had: it was similar to welsh sorta?#lots of consonants and strange sounding vowels. but very clearly *not* made for a human mouth

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

so, if english is notoriously one of the hardest languages to learn, then, hypothetically, does speaking english as a first language make it more difficult to learn other languages later on? or should it ideally make learning other languages easier? i'm thinking of romantic and germanic languages specifically.

like, comparatively, would a native french speaker have an easier time learning german than a native english speaker would learning french? again i'm thinking hypothetically but if there's actual studies on this then that would be cool.

i ask because when i look at sentence structure and syntax of these other languages i find they hinder my comprehension because their direct translations make no sense in english (stuff like verb before subject when asking a question, or noun before adjective) and i'm wondering if my understanding of english syntax could be why i'm struggling

-

19 notes

·

View notes