#German Postwar Modernism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

St. Christophorus

Preungesheim/Frankfurt

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

St. Thomas in Hörnum, Sylt.

Build (1969-1970) by Martin Bernhard Christiansen.

#Architecture#St. Thomas#Hörnum#Sylt#Martin Bernhard Christiansen#German Postwar Architecture#German Postwar Modernism

0 notes

Text

merheimer straße // köln nippes

designing with geometric shapes can be so simple. as is so often the case, elegance lies in simplicity

gestalten mit geometrischen formen kann so einfach sein. eleganz liegt wie so oft in der schlichtheit.

#photography#architecture#germany#architecture photography#design#urban#nachkriegsmoderne#post war architecture#nachkriegsarchitektur#cologne#nippes#köln nippes#facade design#nachkriegsmoderne köln#nachkriegsmoderne deutschland#nachkriegsmoderne rheinland#nachkriegsarchitektur deutschland#nachkriegsarchitektur köln#nachkriegsarchitektur rheinland#german post war modern#cologne post war modern#rhineland post war modern#german post war architecture#cologne postwar architecture#rhineland postwar architecture

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

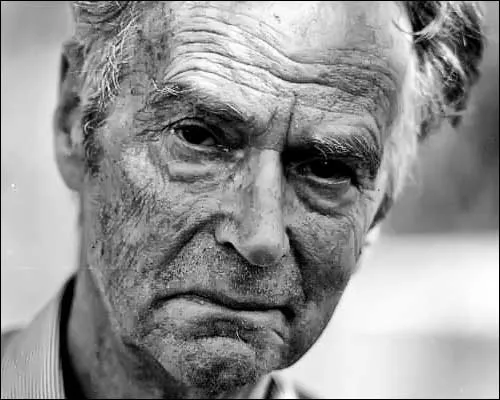

It is usually assumed that abstract and non-objective art aren’t capable of representing concrete historical events in the same way as figurative art. In contrast to this common belief numerous abstract artists in Germany and internationally after the Second World War have referred to historical events they experienced themselves or have occupied themselves with. Examples are Gerhard Richter, Günter Uecker, K.O. Götz or K.R.H. Sonderborg in Germany or Michael Morgner and Dieter Tucholke in the former GDR. These indeed very different artists and their strategies of representation and relation to contemporary history are the primary examples discussed by art historian Anne-Kathrin Hinz's in her dissertation „Zeugnis Zweifel Zeichen - Zeitgeschichte in der Abstrakten Malerei in Deutschland nach 1945“ which was recently published by Deutscher Kunstverlag. In her very detailed discussion of artistic positions and their individual use of abstraction as testimony, doubt or sign, Hinz opens up new perspectives on postwar abstract art in Germany and its complex relationship with contemporary history.

One of the succinct examples is K.O. Götz's series „Jonction I-III“, carried out between 1990 and 1991, with which the artist reacted to the epochal event of the German reunification. By means of their abstract-expressive pictorial language they convey a dynamic sense of immediacy that Götz further underscored in his deliberations about the series: Götz closely followed the events surrounding the official reunification of the two Germanys on TV and even signed the first canvas of the Jonction series with the date of October 3rd 1990. In so doing Götz underscored his eye witnessing of the events as well as the authenticity of the work. Combined with the expressive immediacy of his pictorial language the works become individual testimonies of personally experienced events and thus authentic representations of a historic event.

Götz’s example underscores Hinz’s argument for the representational potential of abstraction as well as it demonstrates that, just like its figurative counterparts, it offers an individual take on contemporary history and thus reality. A great read!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sept. 1 elections in the two eastern German states of Saxony and Thuringia have hit Germany like a cyclone, delivering the strongest-ever turnout for an extreme right-wing party in the postwar era. In Saxony, the hard-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) captured 31 percent, landing it narrowly behind the Christian Democrats (CDU), and in Thuringia, where the AfD is led by a twice-court-fined ideologue and outspoken neo-fascist named Björn Höcke, the party took 33 percent of the vote, the highest of any party, and thus also the mandate to form a government. The new populist party Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW)—a rightist offshoot of the Left Party that boasts anti-immigration planks and pro-Russian sympathies—landed in third place in both states.

Although it is unlikely that another party will partner up with the AfD in governance—they all say they refuse to do so—the results raise resounding questions for modern Germany. How can such an extreme hard-right party perform so well in postwar Germany, a country that, in both its eastern and western postwar incarnations, made preventing the return of a racist, authoritarian leadership its very raison d’être? Why is this phenomenon so pronounced and radical in the country’s east, the territory of former communist East Germany, almost 35 years after the Berlin Wall fell?

Germans are now asking: How could everything go so wrong? Several recently published books by German authors offer a reckoning—and some answers.

Proponents of eastern Germany, including literature scholar Dirk Oschmann and historian Katja Hoyer, authors of recent bestsellers blasting the overbearing West and those taking the West’s side—most of the mainstream media, including the leading weekly news magazine Der Spiegel—are practiced at lobbing rhetorical grenades at one another. On their own, these one-sided arguments miss the mark. But taken together, and combined with new material, they explain how the Germanies’ journey wound up such a wreck.

The cleft between eastern and western Germany—defined by the East’s extreme-right vote and preponderance of street violence, as well as the inability of the republic’s mainstream parties (with the exception of the CDU) to attract eastern members and votes—can be traced to the events following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Today’s hard-right sympathies in the East are largely, though not exclusively, spiteful backlash against the one-sided terms of West Germany’s annexation of the East, the West’s demeaning treatment of the easterners, the indignity that the economic transition inflicted on many eastern Germans, and the legacy of a suffocating, repressive dictatorship on its former subjects and their successor generations.

Detlev Claussen, an emeritus sociologist from Frankfurt, hit the nail on the head: “The AfD is the East’s revenge on the West, which is blamed for all the upheavals after 1990,” he wrote in an email to Foreign Policy. “The party’s personnel are right-wing extremists, the electorate only partly so, although it too appears indifferent to the accusation of Nazism.” Claussen pointed out that populists’ top issues were migration and the Ukraine war, two topics that are not relevant to regional governance. Rather, another topic is almost always predominant behind them, one regularly laced into the rhetoric of both the AfD and BSW: the unfair, demeaning terms of unification and the terms of the transformation since then. “The essence of the far-right vote is resentment against the West,” Claussen wrote.

The AfD vote in the East is complex: The five eastern states aren’t a seething bastion of foaming-at-the-mouth neo-Nazis—although neo-Nazis are among them. German studies show that about 8 percent of Germans—on both sides of the country—firmly subscribe to hard-right, racist ideological worldviews with a large additional segment in a gray zone that might well sometimes—but not always—support the likes of a right-wing dictatorship, street violence against politicos, racist laws, and antisemitism, too.

The numbers aren’t that much different than in other European countries, though they are in Germany currently higher than at any time since the Nazi era, particularly among young people, and also higher in eastern Germany than western Germany. About half of AfD supporters in the East—roughly 15 percent of the voting population—are rightists hardcore enough to actually lionize—rather than just accept—Höcke, who employs thinly veiled neo-Nazi language, soft-pedals Germany’s World War II crimes, and wants to “remigrate” non-native Germans living in Germany to their origin countries.

This radical segment is extremely alarming and constitutes a menace for people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, Muslims, and leftist groupings, among others. They are the types who either perpetrate or condone far-right hate crimes, which have been on the rise for several years. Germany’s security services counted 25,660 such incidents in 2023. That’s an average of 70 a day Germany-wide and 22 percent more than in 2022. In May, a candidate for the Social Democrats was attacked and badly injured in Dresden, capital of Saxony, when pasting up EU election campaign posters. Experts say that this kind of violence hasn’t been so vicious since the 1990s, tagged today as “the baseball-bat years,” when pogrom-like attacks were carried out in the eastern states against migrants and others.

The 1990s is a good place to start to understand right-wing extremism in the East. The easterners had emerged from beneath the heavy hand of Soviet communism and were pleased to be rid of it, as well as welcoming to political and economic systems—liberal democracy and market capitalism—that they knew very little about. They were also unaware of how thoroughly the decades of authoritarian, militaristic education and indoctrination had penetrated their psyches and habits. East German communism was ethnically homogeneous and nothing if not narrow-minded; the very few non-Germans living in East Germany, such as African or Asian guest workers, reported regular abuse. When the wall fell, West German rightists—a generation before Höcke, who himself was born and raised in northwestern Germany—poured into the East to tap this raw energy and organize. When the easterners were confronted with refugee hostels in their communities in the 1990s, they often reacted with anger—and baseball bats.

One explanation of the racist violence and voting patterns today in the East lies in the 1949 to 1990 German Democratic Republic, and the values passed on from generation to generation. The young people today voting AfD and belonging to neo-Nazi street gangs are the children and grandchildren—or come from the same communities—of the bat swingers of the 1990s.

Today’s AfD hotspots are much the same as the sites of the 1990s’ violence. Over the years, one study after another has shown higher levels of racism and intolerance in the East, which the years of transformation have not diluted as the West’s implanted democracy teachers—university deans, politicos, foundation heads, CEOs, school principals, police chiefs—had intended and expected.

But the AfD phenomenon is more layered, since this explanation alone, broadly speaking, pertains to only about half of the constituency and very little of the BSW. It doesn’t explain how over three decades this ugly radicalism could fester and then suddenly explode again into the open. The East’s takeover by the West may have been sanctioned by the easterners in the democratic elections held in 1990—they voted for the CDU and Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who turbocharged the unification process, completing it in just 11 months after the fall of the Berlin Wall—but the pain and sacrifice of the economic transition ran deep and left scars that still smart today, even though eastern per-capita GDP has climbed over the years, today being about 80 percent of its western counterpart, with unemployment at just under 7 percent.

The disappointment and hurt of the easterners should not be underestimated. Kohl had promised them “flourishing landscapes,” but what they received was rampant unemployment: Three million people who had jobs lost them—and were thrown onto welfare rolls, which into the early 2000s equaled half of the East’s GDP. In the low-income labor market, the news was worse: Over 50 percent found themselves jobless. Those who could, including many young people, fled to the West, like the engineer who held the lease on my apartment in Berlin on Friedrichstrasse: He landed a job with BASF in Ludwigshafen in western Germany and never returned. The easterners were incensed at the deals that the Treuhandanstalt—the government agency that sold off East Germany’s enterprises—made for a song. The overnight introduction of the Deutsche mark in 1990 and the Treuhand’s fire sale ensured that western German firms and western German owners would sop up all of the eastern German business—and use the region for a supply of cheap, dispensable labor (which explains the lower per-capita GDP today).

The ostensibly burning topics of migration and the Ukraine war are largely red herrings, concluded sociologist Steffen Mau, author of a widely read new book on the East-West divide, entitled Ungleich Vereint: Warum der Osten Anders Bleibt (Unequally United: Why the East Remains Different). The eastern states have by far the smallest fraction of foreign nationals among the federal states, and those communities with the lowest numbers in the East tended to vote disproportionately higher for the AfD (which also scored well in depopulated rural areas, places with fewer women, fewer medical services, and higher unemployment). They are not threatened by the Ukraine war and have nothing to gain from admiring Russian President Vladimir Putin. The EU, which the AfD lambasts for milking Germany dry, has contributed immensely to the eastern states’ development since unification, to the tune of $53 billion (€48 billion). The German state shelled out nearly $2 trillion (€1.75 trillion).

Mau, in his nicely balanced study, concluded: “The economic transformation of the 1990s, which was associated with major restructurings and brought with it not only freedom but also economic declassification and insecurity, has made people [in the East] less willing to undergo further changes. Having already had to fundamentally change their lives and abandon biographical fixtures, larger sections of the population now strongly resist further impositions, be it growing diversity or socio-ecological transformation.”

None of this, of course, explains why such broad swaths of the population cast their ballot either for a party that tracks closely with neo-Nazis or another that looks to Russia for inspiration and not Brussels. This, though, is the hardest, most in-your-face way to strike back at the system that delivered them such disrespect and injury—and then blamed their backwardness for the mess.

“German democracy possesses its legitimation through its radical break with National Socialism,” Claussen wrote. “The election results in Saxony and Thuringia throw this foundation into question.” It’s a swipe that Germany’s mainstream elites aren’t going to shake off quickly.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The racist dimensions of international politics were manifest and explicitly challenged during the many months of intensive meetings at the Versailles Peace Conference of 1919 – at which was established the scaffolding of postwar colonial and imperial arrangements, including the British Mandate over Palestine.

White powers often described the struggle for 'world domination' as a 'race war' in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. British imperialists distinguished between white and nonwhite (or 'coloured') peoples and assumed the former should rule and the latter should be ruled, defining 'Syrians' and Afghans, for example, as 'nonwhites.' ... Irrespective of anti-Semitism and the historically situated and to some degree malleable nature of whiteness as a social construct, Zionist settler-colonialism was understood by its advocates and their British and US allies to be a white socioeconomic project. Racism in Mandate Palestine expressed itself through civilizational discourse, extraction from the native population, the biopolitics of colonial categorizations and counting, and the systematic maldistribution of life, death, and wellbeing by investment priorities. Such maldistribution by priority is underplayed as a systemically racist dimension of settler-colonialism and colonialism in Palestine. ... The 'blueprint' for the Allied postwar geopolitical order, the League of Nations and its Mandate system, was authored by racist war hero Jan Smuts, an Afrikaner from South Africa, at the behest of the British government. Published in December 1918 as The League of Nations: A Practical Suggestion, the document became a worldwide bestseller. Its stated purpose was to establish 'a means to prevent future wars.' Smuts’s use of the terms 'self-determination' and 'no annexation,' drawing on Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points released in January 1918, offered thin ideological cover for European and US imperialist aims to control postwar geopolitics and resources. The 'peoples left behind' by the dissolution of the Russian, Austrian, Ottoman, and German empires, Smuts rationalized, were 'largely incapable or deficient in the power of self-government.' ... Smuts argued ... that the peoples of Palestine and Armenia were too 'heterogeneous' to be consulted regarding any future arrangement. ... By the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference certainly, British colonial politicians recognized, to borrow Helen Tilley's words, that egregiously racist policies threatened the stability of the colonial order by making 'governing far more difficult.' At the same time, policies of social equality or parity threatened to 'undermine' the (extractive and violent) logic of colonial relationships – the colonizer must be above the colonized. When such hierarchy was shaken, the 'prospects of [the colonized person’s] future usefulness [to the colonial state] is destroyed.' This helps explain why criticism of racial prejudice by some colonial elites 'was insufficient to undermine the social hierarchies of colonial states.'"

Frances S. Hasso, Buried in the Red Dirt: Race, Reproduction, and Death in Modern Palestine (2021)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

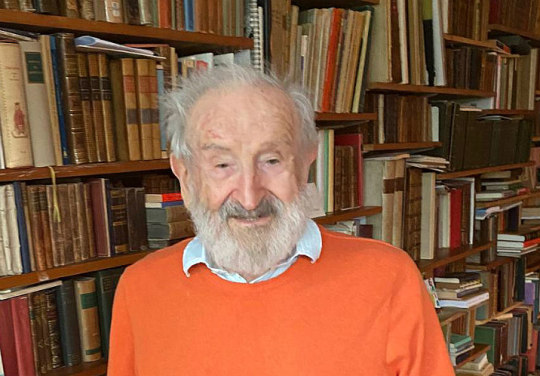

Joseph Rykwert

Architectural writer who believed that buildings not be considered in isolation but as part of the fabric of a city

Joseph Rykwert, who has died aged 98, was a historian and critic of architecture of exceptional intellect, cultural breadth and distinctive outlook. His books and his teaching changed the understanding of his discipline and helped to move the design and planning of cities and buildings away from the functionalist mindset that dominated postwar building. In 2014 he was awarded Britain’s leading honour for architecture, the Royal Gold Medal, one of a very few times that it has been given to a writer rather than a practitioner.

Rykwert’s first book, The Idea of a Town (1963), by exploring the rituals that underlay the founding of ancient cities, sought to restore the importance of such things as memory, feeling, intuition and instinct in the making of the places where human beings live. It was an important part of a wider reaction to technocratic approaches that were causing widespread destruction in cities across the world. It is now commonplace for developers and planners to talk about “placemaking”, by which they mean the ways in which architecture and landscape work together to make social urban spaces, a concept that owes much to Rykwert’s belief that buildings should not be considered in isolation but as part of the fabric of a city.

His other books included On Adam’s House in Paradise (1972), on architects’ enduring fascination with the idea of a primitive hut at one with nature, and The First Moderns (1980) – his favourite – which revealed the roots of 20th-century ideas of modernity in thinkers and architects 200 years earlier.

In all his work Rykwert moved readily between architecture, philosophy, art and other disciplines, aided by his wide erudition and an impressive library that he started building as a student. He was motivated by his certainty that the design of buildings is always part of a wider culture, and by his passion for the places that make a city flourish, whether a remembered street in pre-war Poland or a forum in ancient Etruria. He was, as the writer Susan Sontag put it, an “ingeniously speculative historian and critic of architecture – of that is, the forms (in the most concrete sense) of civilisation.”

The many architects whom he inspired and influenced include the Stirling prize winners Sir David Chipperfield and Witherford Watson Mann, Eric Parry, Patrick Lynch, and Sir James Stirling (the giant of British architecture after whom the prize was named).

Rykwert’s demeanour was gentle and civilised – “the sort of great-uncle I would have liked to have”, as one former student, the artist Richard Wentworth, now puts it, who “always imparted a general sense of mischief”. This character was all the more remarkable for the traumas of his childhood, in which he and his family had to flee for their lives from the advancing German armies. Many of his relatives died in the Holocaust.

Joseph was born in Warsaw, the son of Elizabeth (nee Melup), and Szymon Rykwert. His father, a railways engineer, was ruined after the great crash of 1929, but worked his way back to prosperity. In September 1939, when the Wehrmacht invaded Poland, the Rykwerts escaped via Lithuania, Latvia and Sweden to Britain. Joseph went to Charterhouse, a “plunge” in his words “into the wholly alien world” of an English boarding school. His father died of a stroke early in Joseph’s time there, leaving his mother “skimping” to pay his fees. He went to the Bartlett School of Architecture, which was evacuated to Cambridge in wartime, then the Architectural Association in London.

He started to write, studiously, taking two years to complete his first book review for the Burlington Magazine. He wanted to work for “the London architect I most admired”, Ernö Goldfinger, but was put off by the measly pay on offer – 30 shillings a week – and went instead to the pioneer British modernists Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, who paid five times as much. Rykwert later decided to refuse a job offer in the Paris studio of the most famous architect of the 20th century, Le Corbusier, who paid nothing. Eventually, although his built works included a fur-lined nightclub and a house in Chelsea, Rykwert’s writing and teaching would take over from designing buildings.

In both London and Paris, which he visited as a young man, the postwar years were for him a time of “exhilaration and easy familiarity” in which “people of great intellectual and professional distinction ... seemed prepared to accept an obscure and impoverished youth as a partner in dialogue.” From the age of 18 he exchanged ideas with the future Nobel prizewinner Elias Canetti. Later he became friends with Italo Calvino, whose 1972 novel Invisible Cities owed something to Rykwert’s urban thinking, and the painters Prunella Clough and Michael Ayrton. Iris Murdoch, Umberto Eco and Saul Steinberg were also acquaintances. In 1968 he would befriend the great modernist designer Eileen Gray, then living in obscurity at the age of 90, and rediscover her work in an article for the Italian magazine Domus.

He started to teach, including at Ulm School of Design, in Germany, then considered to be the heir of the Bauhaus as (in Rykwert’s words) “the forge of all that was new in design”, although he found its “systematic rationality” uncongenial. He was librarian and tutor at the Royal College of Art in London from 1961 to 1967 and from 1967 to 1980 professor of art at the new University of Essex.

His postgraduate seminars for the university, held in various locations including the Royal Academy in London with the historian and theorist Dalibor Veselý, were groundbreaking for the way they combined architecture with philosophy and anthropology.

After Essex, Rykwert held posts and professorships at the University of Cambridge and, from 1988 to 1998, at the University of Pennsylvania, and visiting appointments in numerous universities in several countries. In his retirement he continued to welcome lively and creative minds to his book-lined London flat. He was appointed CBE in 2014.

His first marriage, to Jane Morton, ended in divorce. In 1972 he married Anne Engel, his editor on The First Moderns, with whom he enjoyed a successful partnership until her death in 2015. He is survived by Sebastian, his son with Jane, and by Anne’s daughter from a previous marriage, Marina, and by two step-granddaughters.

🔔 Joseph Rykwert, architectural historian and critic, born 5 April 1926; died 18 October 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

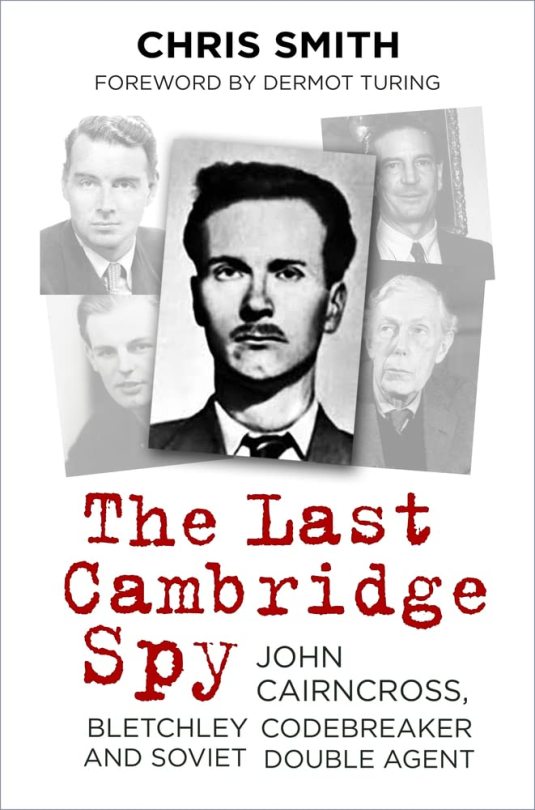

John Cairncross WWII intelligence officer and Soviet spy was born on 27th July 1913 in Lesmahagow, Lanarkshire.

Cairncross was highly educated, attending Glasgow University and obtaining degrees in French and German at the Sorbonne in France before entering Cambridge University on scholarship to study modern languages.

Was introduced to Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess and soon became a Communist working with the Cambridge Spy Ring. Monitored by Soviet agent Samuel Cahan, he received a short course in espionage tactics before taking the Home Office and Foreign Office exams, receiving the highest scores on both.

Was assigned to the Foreign Office in 1936 where he worked briefly with Donald Maclean. Served as Served briefly as the personal secretary to Lord Maurice Hankey who oversaw Intelligence services in Britain. Moved on to the Bletchley Code and Cipher School. In the course of his job he passed intercepted messages and other classified information to his Soviet handler. He often delivered cases full of intercepted German messages int he back seat of his car which he drove to the Soviet embassy.

During World War II, worked for MI6 in its London headquarters. Smuggled plans for postwar Yugoslavia to the Soviets. After World War II, continued to pass information to Soviet agents, including Kim Philby, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess.

In 1951, sensitive documents in Cairncross’ handwriting were found in Burgess apartment after Burgess and Maclean fled to Russia. He was thus fired from his position in the British Treasury department, although he denied being a spy. He turned to scholarly activities and humanitarian efforts for the United Nations.

In 1964, Sir Anthony Blunt confessed to being a Soviet spy and in return for leniency identified Cairncross as another Soviet agent. When confronted with the evidence, Cairncross admitted to his espionage, explaining that he had not spied for several years, saying that he spied only during World War II, when Russia was a British ally.

Soviet defectors later disputed Cairncross statements about his limited involvement in espionage. They claimed that he had turned over countless reams of information.

Fearful of negative publicity and scandal, the British government hushed up his activities, declining to prosecute him for espionage or to expose him to the public. Cairncross, in fact, remained for a time in his job as with the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization.

Cairncross was exposed in 1981 by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. He continued his life in exile until 1995 when he moved to Britain and married American opera singer Gayle Brinkerhoff. Later that year he died after suffering a stroke.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the translator's introduction:

What sparked the interview was Germany’s suppression of views that are critical of Israel’s conduct of the ongoing war in Gaza. Artists, journalists, and scholars who did not follow the official line were silenced, threatened, attacked, and even fired. This shocked Xiang Biao, who greatly values intellectual independence and the role of universities and research institutions in protecting that independence. He subsequently began to pay close attention to the student demonstrations protesting Israel’s prosecution of the war, and especially to the aggressively offensive posture of the German government and German universities, although he came to see them as merely an extreme example of a worldwide posture. In the interview with Wu Qi, Xiang attempts to tease out the logic of the demonstrations and the universities’ reactions to the demonstration.

His argument, in a nutshell, is that the backlash against the demonstrations is a product of a larger failure of the postwar liberal global order. However one views the current war, the Palestinian problem has been festering for decades, and the global liberal order has, broadly speaking, sought to solve the problem by supporting Israel as the sole genuine democracy in the region. The point of the student demonstrations is to shine a light on the manifest injustice this “solution” has produced. Governments and universities have shut down the protests so vigorously essentially because their only answer to the Palestinian problem is more of the same and “let’s not talk about it or I’m sending in the police.”

An excerpt from early on in the interview (the whole thing is so good I want to excerpt all of it):

In Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hanna Arendt emphasized that the Holocaust was not just a crime against the Jews, but against all of humanity, and should be understood in this larger existential sense as an example of the “banality of evil” and not reduced to the sins of one race against another. The vast majority of those killed in the Holocaust were Jews, but many Communists, [Roma and Sinti], and homosexuals were killed as well. Members of the Frankfurt School argued that one of the causes of the Holocaust was modernity, in the sense that it applied rationality to the systematic murder of people; indeed, Frankfurt School thinkers were surprised by the extent of antisemitism they discovered while in exile in the United States, where of course no such massacre occurred.

The Holocaust was thus not a necessary consequence of antisemitism. Antisemitism has been a fact of life in Europe since the Middle Ages, a manifestation of racism, but Jews and Christians in Germany have also coexisted for a long time, and the massacre of Jews was not the result of a sudden intensification of the conflict between the two groups, but rather a problem of modernity, including the problems of racial categorizing and the rigidity that that can accompany rationalism, dehumanization, etc.

It goes without saying that we need to seriously reflect on both the murder of Jews and antisemitism, but one does not necessarily lead to the other. After the Cold War, however, the two seemed to become increasingly linked together in Germans’ minds, and the Holocaust became solely a crime against the Jews. In this way, the liberal order has come to manifest itself in Germany as a moral rebuke to the German people and a profound sense of guilt regarding the Jewish people, and not a thorough reflection on the rationality of modernity.

#xiang biao#reading recommendation#the guy who runs the website translates stuff from chinese to english from all sides of the political spectrum.#it is super useful to gain an understanding of what kind of discussions are going on in chinese academic/intellectual life.#but this one has really good insights on all sorts of things not related to china or a chinese discussion

4 notes

·

View notes

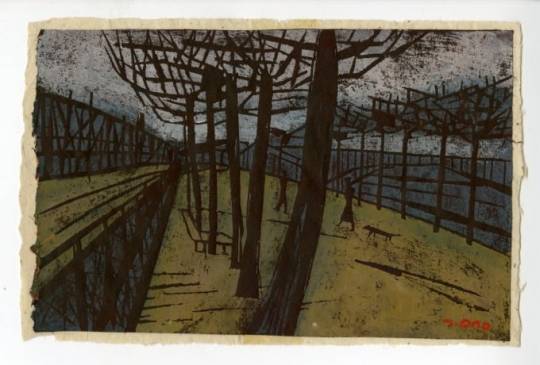

Text

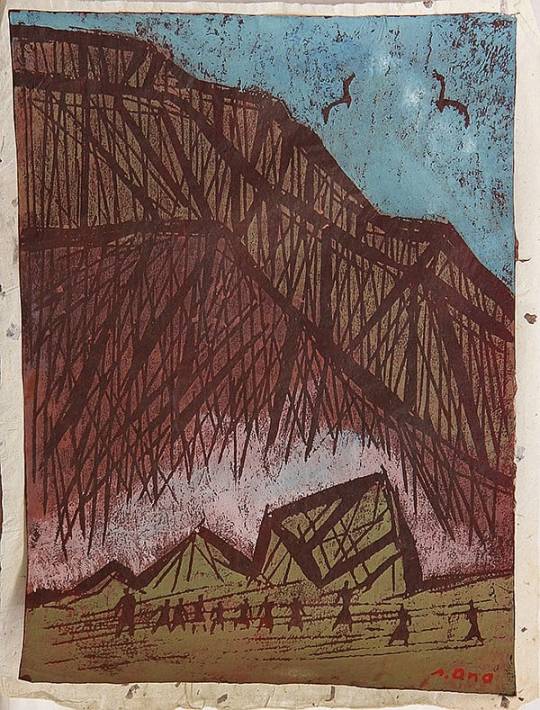

Ono Tadashige is a leading representative of Japanese postwar printmaking. His art style was strongly influenced by the movement of social-critical prints that was wide-spread in the 1920s and 1930s in Germany, Russia, China and also in Japan as the 'proletarian and farmers art movement'.

Ono Tadashige was born on January 19, 1909, in Tokyo, Japan. He had studied art at the Hongo Art Institute from 1924 until 1927. In 1941 Ono Tadashige graduated from the department of Japanese and Chinese languages of Hosei University Higher Normal School. At a young age he became an active member of the sosaku hanga and the proletarian art movement.

After the end of the Pacific War the artist's International career began. His prints were accepted for several of the International Print Biennials - 1957 in Tokyo and 1961 in Moscow. Ono Tadashige became a visiting professor at a couple of Japanese universities - Tokyo University of Fine Arts, Aichi University of Fine Arts, Hiroshima University, and Utsunomiya University.

The artist published several books on modern Japanese hanga and one book on Chinese prints.

Ono died October 17, 1990.

Prints - Style and Technique

The early prints made by the artist, meaning before world war II, were deeply rooted in the social-critical movement of German expressionism and the art trend dominating in Russia and among critical, intellectual circles in China (Luxun).

At the same time, there was a similar art movement in Japan, led and nurtured by Kanae Yamamoto (1882-1946), who is considered the founding father of the sosaku hanga movement. When Kanae Yamamoto tried to return from Europe to Japan in 1916, while world war I was raging, he stopped in Moscow for several weeks, and experienced the beginning of the Russian revolution. Back in Japan, Kanae Yamamoto pursued utopian socialist ideas by founding such projects like "Japan Children's Free Painting Society" or the "Farmers' Art Movement".

This was the background which had formed the character and art style of Ono Tadashige. After the end of the Pacific War, Ono Tadashige's enthusiasm for the ideas of proletarian revolution had lessened, but the way he saw his environment had not changed much.

His favorite subjects were town views of the industrialized areas - factories with tall chimneys, canals with tug-boats. The artist does not show a beautified Japan, but the Japan of industrialized cities.

Ono Tadashige's technique and style is congruent with his subjects. The colors used, are somber with much use of dark brown and black. And while a printmaker usually starts to print the light colors and then adds or overprints the dark colors, Ono Tadashige did it the other way round.

He began the printing process by darkening the paper with black ink. The light and white colors added on top of the black background gave them a kind of opaque effect, which is so typical for the art prints of Ono Tadashige.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

cant decide if Ludwig would have like a cozy lidl grandma home bc he’s so attached to the old things and he thinks it’s cozy ^_^ or if he would rock da Postwar Modern German interior design ……. Much 2 think about … …. Actually. Like this: Ludwig has a cozy little house on the countryside where he resides and then a modern apartment in Berlin with shit like this

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know that the German nature painter Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), who was an insect fanatic, laid the foundations of modern zoology with fantastic illustrations of more than 200 insect species?

Have you heard of the English paper collagist Mary Delany (1700–1788), postwar Japanese photographer Ishiuchi Miyako (b. 1947), and Venezuelan Minimalist Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt, 1912–1994)?

After reading Katy Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men, several educators may aspire to redesign their art history surveys and syllabi — and perhaps trade some Picassos or Pollocks for Merians and Gegos.

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ian Ellison: What is it about Rainer Maria Rilke? The influence of the Bohemian Austrian poet on modern culture reads like a who’s who of the great and the good. W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Edith Sitwell claimed to be directly inspired by him. The first English translations of his work, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, became classics in their own right.

He has been set to music (both classical and rock) and proven himself a Hollywood touchstone, most recently providing the concluding epigraph of Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit. Oprah Winfrey has quoted him on television and Lady Gaga has lines from his Letters to a Young Poet (1929) tattooed on her arm.

Maybe he has had such an impact because he is first and foremost a poet of the heart. He expresses those emotions we seldom desire—melancholy, longing, and loneliness above all—with such artistry and feeling that it can seem almost joyful. At the more esoteric end of things, he is regularly co-opted by New Age self-help gurus who take the closing line of his “Archaic Torso of Apollo”—“You must change your life”—as their mantra. Faced with the immensity of his work and its afterlives, you might feel like you know enough about Rilke, but the man himself has for a long time remained something of an enigma. Yet this may well be about to change.

It is rare for a poet to make headlines almost a hundred years after their death, especially for good reasons. But in early December 2022, Rilke was suddenly front-page news across Germany. In what was widely described as the purchase of the century by the German media, the Deutsches Literaturarchiv (DLA) announced it had acquired a collection of Rilke’s manuscripts comprising some 10,000 handwritten pages. These included draft poems and notes for their composition, as well as 2,500 letters written by the poet himself and a further 6,300 addressed to him. One of the most significant literary estates in postwar history, its cultural value is priceless, and it will soon be made available to the general public. A major exhibition at the Literaturmuseum der Moderne (the DLA’s next-door neighbor in Marbach) is planned for 2025 to mark the 150th anniversary of Rilke’s birth, and plans are afoot to digitize the entire collection. After being cataloged, the collection will be made available online without restriction, opening up this treasure trove to academic researchers across the globe, as well as general readers.

[Unboxing Rilke’s Nachlass :: April 6, 2023 • By Ian Ellison]

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

EMMA WARREN So, how did the band start? STEPHEN MALLINDER We started literally taking that Eno ethic, we just used to buy tape recorders. We used to make tape loops, we got shitloads of tape recorders. We used to lug them into this attic, which was the pain in the arse, because some of the tape recorders we used to get back then... It’s interesting electronic music, at that moment in time. EMMA WARREN So, we’re talking 1978? STEPHEN MALLINDER No, 1974 then. This is about ’73, ’74, when we first started. And if you wanted a tape recorder, you used to go to these trade magazines, called Exchange & Mart in England, and basically they were old government machines. Ex-World War II, military stuff and you buy them for like about £5 and they weighed about two tons. They were fucking massive things, you know? EMMA WARREN What did these things look like? STEPHEN MALLINDER They were like big lumps of metal, you know? They were like enormous kind of industrial tape machines. We used to get all things like that because that’s where electronic music really came from. People now look at it in terms of Robert Moog and Léon Theremin, etc, but a lot of electronic music and stuff we were doing, actually, it came really from Second World War technology. It came from the whole notion that war obviously does do crap things, but they do certain things and accelerate certain aspects of technology. So, we were picking the things that really were probably used in a war. We got these, you know, really 20- or 30-year-old machines, lugged them up to the attic and made tape loops and things like that. EMMA WARREN That’s an interesting idea, isn’t it? War as a motor of modern music. STEPHEN MALLINDER Yeah, completely. Well, it is, you know what I mean? EMMA WARREN Plus, war invented the Internet. STEPHEN MALLINDER Yeah, I mean, that’s right. Kraftwerk resulted from a German culture from the postwar period. So, you got to remember electronic music is quite affected culturally by those things and we were as well, you know?

- Stephen Mallinder interviewed by Emma Warren for Red Bull Music Academy

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Although it had its origins in the 1920s and 1930s, the large-scale production of prefabricated housing really took flight after the Second World War. Especially in the Socialist parts of the postwar world the „Plattenbau“ helped remedy the housing shortage but also resulted in often monotonous development areas. Behind the Plattenbau often stood a utopian vision of progress and a new communal life that was diametrically opposed to what the areas turned out to be.

Drawn to the Plattenbau by the contrast between vision and reality photographer Christoph Montebelli set out to document four Plattenbau housing estates on four continents, namely in Berlin, Hong Kong, Havana and Zanzibar. On site Montebelli not only focused on the architecture but also on the inhabitants and the surroundings of each of the estates. What emerges are very lively portraits of architectural visions that despite many similarities significantly differ as Montebelli explains in the brief texts prefacing each photo series: to Zanzibar the Plattenbau came as a diplomatic trade-off between the GDR and President Karume who in exchange for the diplomatic recognition of the East German state received technical assistance in the construction of modern apartment blocks. Although they weren’t made from prefabricated concrete elements but from brick they are referred to in the imported German term and furnished with GDR imports. And as Montebelli’s photographs show they over time have been absorbed by the locals and represent anchor points in their bustling surroundings.

The Berlin Plattenbau estate on the other hand has fared quite differently: while the GDR still existed the housing blocks were occupied by a multifaceted mix of people ranging from workers to teachers, engineers and professors. All of them valued the modern accommodations of the Plattenbau that provided so much more comfort than old buildings and consequently were in high demand. After the fall of the Berlin Wall the situation changed drastically, the social mix dissolved, the „Platte“ fell into disrepair and was partially dismantled. Today the dismantled apartments are badly needed.

In his book „Plattenbau Promenades“, recently published by Kerber, Christoph Montebelli underscores the perseverance of the Plattenbau who easily outlive(d) the visions of their commissioning governments but remain lively cues of the past, emphatically documented in powerful photographs.

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think the current national literatures model in universities will be supplanted by comparative literature, cultural studies, or something else altogether? In other words, what is the future of literary studies in universities?

There is no future for literary studies in universities, but yes, you're right, and this has been happening for a while. Last time I checked, which was about 10 years ago, job searches in English were reserved for Americanists with multicultural specializations (i.e., America as globe) or for specialists in "global Anglophone literature," the replacement sub-field for what used to be modern Brit lit.

(In fairness, there were also ads for early modernists and Shakespeareans, but that material can be understood as pre-national as much as foundationally national, depending on your preferred Shakespeare play: close thy Henry IV and open thy Tempest.)

Nationalism as the political signature of modernity appears to be have been a vanishing mediator between pre- and post-industrial imperial epochs. The most famous comparatist of his generation, Edward Said, understood this, I believe. At times, he candidly allowed that his "Palestinian nationalism" was in fact a metaphor for a new internationalism, hence his urgently felt need to lay low Zionism, representing in his view the last gasp of 19th-century nationalism, and this in unexpected defense of how he himself grasped "Jewish intellection" as permanently diasporic consciousness. (I explained this controversial premise here.) Said's training in the similarly utopian if Euro-centric discipline of postwar comparatism, and his consequent reverence for Auerbach, probably inspired these global commitments more than Marxism or "postmodernism" did—consider also George Steiner—despite Said's more famous uses of Gramsci or Foucault. Auerbach ends Mimesis with that uneasy if progressive prophecy that Proust, Joyce, and Woolf portend the universalization of a common consciousness.

What do I think of this personally? I am skeptical of all political utopias—national, imperial, and "global." Much of modern literature was forged in the same crucible as the nation-state and needs to be understood in that context, despite the many satisfying ironies involved, such as German literary nationalists inspiring English and American literary nationalists in their nationalism, and therefore rendering their nationalism paradoxically internationalist. I have insisted, though, that literature, or rather art in general, needs to keep its options open about its social and institutional bases and shouldn't be too nostalgically attached to institutions that no longer serve its purposes, whether the nation-state or the university itself. Those are my opinions as a writer and as a one-time inhabitant of the English department. As a citizen, I have a certain obdurate immigrant's-child loyalty to American civic patriotism, but, because America is not an ethnic or a religious state, because it is a potentially universal polity—again, America as globe—this shouldn't be confused with nationalism.

#academe#english literature#comparative literature#edward said#erich auerbach#literary studies#literary theory

5 notes

·

View notes