#cologne postwar architecture

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

merheimer straße // köln nippes

designing with geometric shapes can be so simple. as is so often the case, elegance lies in simplicity

gestalten mit geometrischen formen kann so einfach sein. eleganz liegt wie so oft in der schlichtheit.

#photography#architecture#germany#architecture photography#design#urban#nachkriegsmoderne#post war architecture#nachkriegsarchitektur#cologne#nippes#köln nippes#facade design#nachkriegsmoderne köln#nachkriegsmoderne deutschland#nachkriegsmoderne rheinland#nachkriegsarchitektur deutschland#nachkriegsarchitektur köln#nachkriegsarchitektur rheinland#german post war modern#cologne post war modern#rhineland post war modern#german post war architecture#cologne postwar architecture#rhineland postwar architecture

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

For a quarter of a century Willy Kreuer (1910-84) taught as professor at the Technical University of Berlin and in this capacity had a lasting impact on a number of students: after graduating quite a number of alumni since the 1970s met on a regular basis in so-called „Kreuertreffen“ to reminisce about Kreuer, his teaching and the excursions he organized. On the occasion of his 100th birthday in 2010 these former students put together a very interesting publication that to this day remains the sole comprehensive survey of the architect’s life and work: “Willy Kreuer 1910-1984”, both monograph and personal recollection that combines a work catalogue with students’ anecdotes, a biography and insights into the personality of the architect. Although Kreuer's work is deeply intertwined with Berlin he actually was a Rhinelander: born in Cologne he also took his first steps as a young architect in the city, namely in the well-known offices of Dominikus Böhm and Martin Elsaesser. In 1937 Kreuer moved to Berlin and a year later became an associate of Werner March, architect of the Berlin Olympic Stadium and a favorite of the Nazi nomenklatura. After war service and the end of WWII he worked as chief architect in the office of Eckhart Muthesius until in 1949 he became assistant at the Chair of Urban Planning and Housing Development at TH Berlin, a position that qualified him for the professorship he assumed in 1952.

In the following two decades, parallel to his professorship, Kreuer realized a number of important buildings in the Berlin, e.g. the town hall in Kreuzberg, the ADAC administration, the Technical University’s institute at Ernst Reuter Platz or the St Ansgar Church, integral parts of Berlin‘s postwar architectural history. These buildings are also covered in the book but a good deal of it also is assigned to his former students’ recollections of seminars, excursions and Kreuer's sociable personality. Unfortunately the book is grey literature and as such hasn’t received much attention because it wasn’t officially distributed through the book trade, a real shame since it is an unusually lively publication and to date the most comprehensive way to get acquainted with the work and life of an important Berlin architect!

#willy kreuer#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architecture book#monograph#book

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 Ways to Completely Sabotage Your black xs by paco rabanne for men eau de toilette spray 3 4 ounce bottle

PERFUME-- As the world's oldest fair of its kind, this city's yearly hodgepodge of modern-day and modern art has offered important (if sometimes conflicting) insights into economic as well as visual trends. This year's occasion was no exception.

Though one could hardly speak of a remarkable turnaround, there was little complete satisfaction for those prophets of doom who saw the modern market as particularly susceptible. In the 43rd installment that closed on Sunday, Art Cologne explained that the first order of business was to create a sleeker, leaner profile after years in which the fair had actually ended up being so puffed up that lots of gallerists and collectors honored it more in the breach than the observance. Last year such leading lights as London's Annely Juda Fine Art, Düsseldorf's Galerie Hans Mayer and Cologne's own Galerie Michael Werner simply remained at home, while participation dropped by more than 5,000 visitors. The pace-setting trio returned this http://edition.cnn.com/search/?text=Cologne year, proudly occupying the very first row and setting the remarkable expert requirements for which they have actually so long been understood. Attendance remained fixed, and there is clearly much work to be done if Perfume is to rearrange itself effectively within the extended family of fairs it has generated over the last 4 years.

There is, of course, an intrinsic dispute of interests between a fair's organizers and its participants. Still, it was in the interests of neither partner that the mother of all art fairs had begun to go to fat. In current years, a bunch of remedies-- unique events and exhibits, rewards and marketing gags-- were designed to invigorate the ailing dowager, however they showed of little obtain.

The outcome was a leaner and more focused discussion that inhabited 2 floors of a single exhibition hall. Gone were the champagne bars and luxurious carpets, the over-styled stands and designer sofas. The brand-new slogan was everywhere obvious: Back to Essentials!

It was, above all, the stricter filtering of applicants that restored a few of Art Perfume's authority. For some participants, the outcomes were tangible and instant. The resourceful Galerie Löhrl (Mönchengladbach) offered 20 deal with opening night, and more than doubled that overall in the 5 days that followed. Berlin's Galerie Fahnemann needed to rehang three times to fulfill need for works there, including a canvas by Imi Knoebel that brought EUR150,000, or $195,000. For Tom Wesselmann's "Red Ending," the Perfume gallerist Klaus Benden discovered a purchaser unfazed by the EUR450,000 cost. A lot of his coworkers, however, rarely covered their costs.

The organizers and participants benefit high appreciation for their efforts, the worldwide dimension of the fair was modest at best. Of 180 participants, 120 came from Germany, and 51 of those from the surrounding Rhineland capitals of Düsseldorf and Perfume. In regards to gallery representation, all but one of the leading 10 artists were Germans, and all were male. They represent the postwar generation that discovered its distinct voice in the 1960s and '70s, consisting of Georg Baselitz, Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke. With nail-reliefs on view at 9 various galleries, Günther Uecker was the undeniable champ. What this informs us is something that can be observed in different degrees throughout the marketplace: Functions by recognized skills with long track records and strong museum presence are holding their own. Fears of disposing in the modern field were not verified, though the average margins enabled bargaining increased by at least 10 percent.

Frequently these were works on paper or smaller canvases like those of Zsombor Barakonyi at Budapest's NextArt Galéria, a Cologne newcomer, or the classy paintings of Heinrich Salzmann-- lovingly painted details extrapolated from larger images-- at Munich's Galerie Rieder. Frequently, certainly, the formats showed the fair as a whole: more focused, more reflective, more fine-tuned. In this encouraging atmosphere, galleries and artists and specific works became noticeable that tended to be obscured by the razzle-dazzle of the boom years.

A clear standout was the exceptional work of Kirsten Everberg at the Los Angeles gallery 1301PE, returning to Cologne after a year's lack. Using aspects from movies, art history and architecture, the artist collages seemingly "real" scenes, generally interiors, that glow like cloisonné. The luminescent interiors painted by the young Julia Rothmund-- an authentic discovery at Galerie Löhrl-- are likewise resonant with narrative.

Initially glimpse, this year's Art Perfume appeared to minor the medium of photography, which was so much in vogue at the reasonable just a decade ago-- thanks in specific to the smooth and overblown "variations on the commonplace" preferred by the so-called Düsseldorf School. In truth, photography stayed a significant medium this time round, however in more subtle idioms and smaller formats. Viewed in historic terms, there was an appealing "standoff" in between classical European photography, showed with fantastic authority at Vienna's Gallery Johannes Faber, and the American variety revealed by Laurence Miller of New York City, who was displaying in Cologne for the fist time. At Faber it was the official structure that controlled, while the American "eye" as recorded by such brand-new masters as William Eggleston and the late Helen Levitt is more private and relatively more serendipitous. None of the results were so intriguing as those achieved by Hiroyuki Masuyama and exhibited in a spectacular one-man salon created by Studio La Città Gallery of Verona. Masuyama recreated the very https://sykscents.com/brand/liz-claiborne/ first journey of J.M.W. Turner from London to Venice, pausing to photo the exact same websites that Turner painted. When 200 photographic pictures of a scene are superimposed to form a single image, the results have a painterly quality that is amazingly Turneresque.

Perfume's future depends less on such bonbons than on bring in the kind of brave collector who once made this the pre-eminent address for modern art.

The existing stress on recovering a global profile may actually obscure the new function Art Cologne may ultimately play as a regional (not provincial) contender with wide-reaching authority. It is also home to numerous of the country's leading galleries and many savvy collectors. Otherwise, one may take a cautionary lesson from the gigantic bronze sculpture that stretched before the entryway to the newest installation of Art Cologne: a fallen, broken Icarus by Stephan Balkenhol.

0 notes

Text

The Hanseatic League was a medieval and renaissance era alliance of Baltic and North Sea trading ports and merchant guilds whose footprint stretched from the east coast of England to the river city of Novgorod in Russia. Starting from a group of German cities in the 1100s and operating until its decline in the late 1600s, and run for the benefit of their merchant class, the League was instrumental in creating strong city-states that complemented the traditional land-based aristocratic and religious power of the time. They created trading networks based on law and mutual obligation, backed up by regional law courts and periodic league conferences in the port cities. The League negotiated relief from tariffs, fought pirates and attempted to monopolize certain trades.

This way, you could somewhat reliably ship a cargo of goods (a “Hanse” was a protected convoy) from Cologne to Tallinn, and get paid, when for a time Mongol invasions further south and east were live news. Lubeck’s merchants were principal originators of the League, trading from a hub between the German hinterland, Scandinavia and the Kievan Rus (itself a Federation of areas that now comprise parts of western Russia, Belarus and Ukraine).

You can still see this active society reflected in the buildings and communities in places such as Lubeck, Rostock and Stralsund, which were important Baltic sea ports at the time. It still figures in German culture, from the name of their airline to the local football clubs, and an “H” put before the town letter on car number plates.

Lubeck

Lubeck has a large and well-defined medieval city area, which is an island that the Trave River flows round. It is very walkable and has a neat port area on its northwest side along An der Untertrave with a few historical ships, including a lightship, for your nautical fix. The city’s renaissance-era ceremonial gate, the Holstentor, with its chubby ceremonial towers that appear to lean in to each other, is suitably impressive. You can “almost” not see post-renaissance buildings as you walk towards it.

The Holstentor

Heading into the central Markt, south of the 13th-century Marienkirche, you find many well-preserved (or restored – Lubeck was bombed in WW2) medieval features, including the medieval city hall.

Lubeck Market Square

Hansamuseum. Lubeck’s European Hansamuseum (An der Untertrave 1) is well worth a visit to understand how trade developed in the early middle ages and developed today’s Baltic cities into prosperous commercial centers, driven by considerations separate from the Church and aristocracy. (hansemuseum.eu)

Gunter Grass House. Lubeck was home to Gunter Grass, one of Germany’s most important 20th-century writers, who was born (1928) and raised in Danzig. Danzig, now Gdansk, Poland, was part of East Prussia and mostly ethnic German at the time, and absorbed into the German state in 1939. It was the city in which the novel and film The Tin Drum was set. After wartime service and art school in Dusseldorf, Grass eventually settled in Lubeck, and the Gunter Grass House (Glockengiesserstrasse 21) is well worth a visit. Grass was politically active and attempted to articulate West Germany’s postwar identity in much of his work. Notably, he failed to reveal until 1996 that part of his forced wartime service had been in the SS, which was considered an oversight at the time.

Willy Brandt House.The garden of Gunter’s house adjoins the birthplace of Lubeck’s other famous son, the postwar politician Willy Brandt, who is best known for Ostpolitik – advancing detente between Germany and the Soviet Bloc during the 1960s and 1970s. Brandt was West Germany’s Chancellor between 1969 and 1974 but had worked his way up as Mayor of Berlin (hosting John F. Kennedy’s famous 1961 speech), Foreign Minister and other posts since the 1950s. His tenure as Chancellor was cut short by the revelation that one of his aides was an agent for the East German intelligence service, the Stasi. The Willy Brandt House (Königstrasse 21) is a good place to get an understanding of Germany’s postwar history.

Other things worth seeing as you wander round this pretty town include the Buddenbrookhaus (Mengstrasse 4), which is a museum dedicated to the author Thomas Mann, and the Holstentor Museum, which is a good way to understand Lubeck’s history and to explore the two towers.

Food & Beverage. Lubeck has a local brewery, Brauburger ze Lubeck (Alfstrasse 36), that is also worth a visit afterwards. Brewed on-site, their traditional zwickelbier is highly regarded, although they have dipped a toe into IPAs.

There are plenty of solid (some literally) food options in town. For a traditional north German effort, Alstadt-Bierhaus Lubeck (Braunstrasse 19) is worth visiting. The Kartoffelkeller (Koberg 8) is a popular cellar restaurant offering plenty of options around the potato. The Junge Die Bäckerei, a regional chain on the south side of the main square, is a good breakfast or cake/coffee stopoff, and the Kaffeehaus Lübeck (Hüxstrasse 35) is a nice out of the way place.

Rostock

In contrast to Lubeck, Rostock has a more modern feel, largely due to it’s role post-WW2 as the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) main sea port and shipbuilding center. Coming from Lubeck, which was in West Germany during the Cold War, Rostock contrasts with postwar reconstruction carried out by the GDR, which existed between 1949 and 1990. It’s a pleasant mid-sized town that doesn’t deal with overtourism and is a good base for the surrounding region.

Rostock’s city is worth a look to see Soviet-era architecture, such as its postwar Communist parade, Lange Allee, which splits the city north and south. What is left of Rostock’s rebuilt old town, to the north and east of the center, is pleasant and unassuming and you can pass through it on the way to the waterfront on the north side of town.

Rostock maintains many of the Communist-era street names, so it will be possible to find Karl-Marx Strasse and Rosa Luxemburg Strasse – although this isn’t unusual in former GDR cities.

Rostock is a good base to see two nearby attractions, the beach town of Warnemunde and the preserved East German merchant ship Typ Frieden, which has a unique exhibit of East German shipbuilding and its merchant marine. Both can be done in the same journey as they are along the same local S-Bahn rail line that runs north to the beach.

Warnemunde. Warnemunde is a rather touristy (receiving cruise ships) but fun German seaside resort which as a fishing village grew from the late 19th century, when working and middle-class Germans – especially from Berlin and other large cities – started to be able to take vacations. It’s not really worth an overnight stay unless you are a beach person. You can either go to Rostock Hauptbahnhof and take the S-Bahn local train up, or if located in central Rostock, take the No. 1 or 5 trams west to the Rostock Holbeinplatz S-Bahn station and take the train north from there.

From the train station, you can cross west over the Alte Brucke and wander up Am Strom to the beach, and grab a backfisch and a beer along the way. It’s quite pleasant and laid back. There are also some decent places for lunch away from the main crowd if you head south along Am Strom from the Alte Brucke – zur Krim was good and had a nice garden out front.

The Typ Frieden. Rostock’s Shipbuilding and Maritime Museum is located in the cavernous cargo hold of the Typ Frieden, a 1957-vintage merchant ship built in Rostock that operated as the Dresden until 1970. It has a very comprehensive museum of shipbuilding and the merchant marine of the industrially diligent GDR. Now that that the GDR has been gone for 30 years, it’s an insight into a bygone era of communist heavy industry.

The ship’s large multi-deck cargo hold contains the museum, which has mainly photographic, equipment and model exhibits. If you are interested in heavy post-war industry or how socialist shipping lines served Soviet Bloc routes to Cuba, this is the place to go.

The bridge, engine room and crew quarters are preserved in all their 1950s glory.

To reach the museum, take the train to the Rostock-Lütten Klein stop and walk east via the conference center and the park (which is a wetlands area) to the riverfront. (www.schifffahrtsmuseum-rostock.de)

Food, Beverage & Accommodation. Rostock has a good range of food options and doesn’t suffer from overtouristed clip joints. The Braugasthaus Zum alten Fritz brewpub, located on the waterfront at Warnowufer 65, has a typical German menu and fresh draught or bottled Störtebeker beer (https://www.alter-fritz.de), brewed in nearby Stralsund. The Altstädter Stuben, in the old town to the east at Altschmiedestrasse 25, is a good neighborhood restaurant. Kaminstube, at Burgwall 17, is another low-key place in the northern old town with a large outdoor veranda to get a beer from the local brewery or a meal. I stayed at the Pentahotel, Schwaansche Strasse 6, which is central and modern, with a good lounge area on the ground level and outside.

Transport Logistics. Rostock and Lubeck are easily reached from Berlin. I went via Copenhagen to Lubeck, and both bus and rail journeys (about 4 hours) connect via the Rodby-Putthaven ferry link. You can book online (ferry ticket included) through Flixbus (www.flixbus.com) or German Rail (www.diebahn.de).

The Full Hansa: Lubeck and Rostock The Hanseatic League was a medieval and renaissance era alliance of Baltic and North Sea trading ports and merchant guilds whose footprint stretched from the east coast of England to the river city of Novgorod in Russia.

0 notes

Text

The 2019 Audi A7 Sportback Goes to Lüderitz

LÜDERITZ, Namibia — The sat-nav says arrival time 12:53 a.m. The man from Audi advises us not to drive after dark because of wild animals. The photographer says let’s get on with it. My inner voice tells me to believe in the power of laser headlights and night vision, so let the impala and springbok play hide and seek if they want.

On the two-lane N7 highway between Citrusdal, South Africa, just north of Cape Town, to Vioolsdrif at the Namibian border, progress is a matter of attitude, aspiration, and ambition. In addition to being on high alert for any wildlife lurking in the bush, we’re also busy dodging underpaid and overly keen asphalt jockeys in charge of slowly disintegrating tour buses, mirrorless vans on a clock-beating mission, and grotesquely overloaded semis. But thanks to some 39 assistance systems and a switched-on driver who can’t spare a single digit to toy with the seductive, colorful touchscreens, the new 2019 Audi A7 cuts through it all with relative ease. When we hit Klawer, about a quarter of the way to Vioolsdrif, the estimated arrival time has lowered to 12:11 am. We’re making headway.

Our destination is the port of Lüderitz on the Namibian coast, founded in 1883 by settlers from Berlin, Dresden, and Cologne. The A7 Sportback 55 TFSI we’re in is fitted with every conceivable extra and then some. It even features double-glazed glass, multicolor ambient lighting, and intelligent wipers with washer jets focusing on the dirtiest spots. Back-seat magnates like The Donald would undoubtedly appreciate modern conveniences such as Twitter access and the pay TV module; owner-drivers are more likely to applaud the fully automatic parking assistance system, which takes the sting out of hungry curbs and tight entry and exit spirals.

Despite the puzzling 55 TFSI badge, the A7’s base powerplant remains Audi’s 3.0-liter turbo V-6, which now delivers 340 horsepower. It’s been thoroughly modified, feels livelier, and plays a catchier tune. The seven-speed S tronic automatic transmission is really on its toes in Sport mode. Eco efforts include a start-stop system that calls it a day below 15 mph, an efficiency program that cuts the engine between 30 and 100 mph under trailing throttle, and a green lift-off symbol in the instrument binnacle, which suggests that now is the time to take it easy.

It’s not only the 340 hp that gets things done but also the torque curve, which peaks at 369 lb-ft between 1,370 and 4,500 rpm—it is as flat as Cape Town’s famous Table Mountain. The Audi collects further brownie points for its ability to accelerate to 60 mph in an estimated 5.2 seconds, its brisk downshift action, ambitious redline that touches 7,000 rpm, and its aggressively spaced third through fifth gears.

Praise is also due to the air suspension that leans the car ever so slightly into the random gusts of crosswind.

Bureaucracy thrives at the border crossing that separates South Africa from Namibia. We’re in a hurry, but the squadron of uniformed state servants on both sides of the barbed wire evidently has all the time in the world. For no good reason at all, we waste almost an hour filling out forms, waiting for stamps, paying fees, and having the vehicle searched. As a result, our ETA has dropped back. No way are we giving in. So let’s fill up the Ara Blue-sprayed hatchback-coupe and get back after it. We’re going to need to rely on the technical improvements that set the new A7 apart from its predecessor: its piercing matrix-laser headlamps, recalibrated air suspension, and rear-wheel steering chief among them. Having fiddled with Drive Select for the past six hours, the preferred configuration locks the drivetrain in Dynamic while the algorithms looking after steering and chassis are left alone. Above 75 mph, the road-hugging sports pack lowers the ride height by another quarter inch or so.

The final leg of the night stage to Lüderitz goes down in the logbook as a real challenge and an eerie experience. What looks like London fog is actually a proper sandstorm, whipping tall, thin curtains across the road and drowning tire and engine noise in pelting spells that sound like a million needles pitting the paintwork to the primer. The curvy highway is littered with tumbleweed and occasional waves of rock-solid drift sand. It’s a baptism of fire for the A7’s rear-wheel steering, which enhances stability and maneuverability depending on how fast you’re going. Praise is also due to the air suspension, which leans the car ever so slightly into the random gusts of crosswind. Although the broad light cone cast by the matrix-laser wonderbeams could almost touch the horizon on a clear night, we’re limited to low-beams in this tempest.

Helping the cause is Audi’s latest, more fuel-efficient Quattro system—dubbed Ultra—effectively all-wheel drive on demand. Rear-wheel drive only activates to support takeoff traction, cornering grip, and handling bias. Acting progressively and imperceptibly, it engages and disconnects in milliseconds. For enhanced road holding and curb appeal, our test car was fitted with 20-inch wheels shod with 255/40 tires. In the previous A7, this setup in combination with the sport suspension would have smashed a set of false teeth to pieces. The second-generation model, however, has learned to ride more smoothly. Like every Audi, this one is still not pleased with transverse irritations, but it no longer absolutely hates potholes, manhole covers, and railroad crossings. The steel brakes deserve applause for prompt response and efficient deceleration, but it also earns a few scattered boos for elevated pedal pressure, which increases with every repeat high-speed action and is accompanied by a certain sponginess over the final 100 yards or so before the vehicle comes to a full stop.

“No, we don’t have Wi-Fi. Talk to each other!” This sign put up at Giesela’s breakfast station down by the sea is not only a mocking shot across the bow of the Facebook crowd but also confirms in writing that digitalization has not yet fully arrived in Lüderitz. Almost everything related to electricity does in fact move at a different pace in this part of Africa. Filling up the car takes around 10 minutes, the streetlights flicker at night like back in the postwar days, and paying with a credit card only works when a favorable internet wind blows.

We were constantly on guard for African wildlife hiding in the bush, and the new Audi A7’s laser headlights and night vision helped us keep a better eye out.

Architectural gems like Villa Goerke, which looks like something that was helicoptered out of Bavaria and dropped into the rugged desert, dot the landscape. Built in 1909 during the diamond rush, it is now a national historic monument. Then there’s Shark Island, an area that has become prime residential property but used to be a German labor camp where thousands died in the early 1900s. It is a lasting symbol of the numerous atrocities committed against indigenous peoples by the colonial powers.

The Germans, who had claimed large chunks of Africa in 1884’s Berlin Conference, were running the show here.

So although not all of the wounds from those dark days have fully healed, there is a special spirit that has developed among the locals, known as Buchters (Bucht is the German word for bay), who pride themselves on living life to the fullest. Many of them are trilingual, fluent in Afrikaans, German, and English.

The A7 is linguistically even more talented. It speaks more than 15 languages and understands every spoken and written word, although it needs a stable web connection to shine, which is as rare as an ice-cream vendor in this scorching part of the world. But even without car-to-infrastructure intelligence, real-time traffic information, and super-precise HERE maps, the in-dash mix of touchscreens, displays, and buttons is pure sensory overload—a potpourri of recurrent distraction and stubborn, smeary fingerprints. Make no mistake: This is a great-looking, beautifully made, and emphatically modern cockpit. But like in an Airbus A320, you almost need a co-pilot to make full use of the car’s diverse talents.

A short distance from Lüderitz is the ghost town of Kolmannskuppe, a series of buildings fighting a losing battle against sand and wind and time. Kolmannskuppe was built between 1908 and 1910 next to the country’s first diamond mine, which yielded more than 5 million carats of gemstone before World War I broke out. The Germans, who had claimed large chunks of Africa in 1884’s Berlin Conference, were running the show here and in Lüderitz. And what a show it must have been. The largely intact wood-paneled town hall houses a theater, cinema, library, bowling alley, restaurant, bar, and gymnasium.

Perhaps the biggest frivolity was the stone-walled saltwater swimming pool the size of a football stadium, which still caps the hill like an ancient helipad for the gods. A guide named William takes us through the buildings. “Goods were transported by horses, boats, and eventually by rail,” he says. “Round about that time, the diamond barons brought in the first motor cars. When a Mercedes or Rolls broke down, it was simply put away while a new one was ordered. Wealth was unreal in those days.” After a short 17-year boom, the miners moved on, and Kolmannskuppe was abandoned by 1956.

Today’s travelers on African roads don’t have the luxury of waiting months for a new car to replace the old one, let alone hours to fix more than one flat tire or a mechanical fault that grounds the vehicle in the middle of nowhere. Then there’s the worst-case scenario, getting in a crash, since the next hospital is more than likely a long drive or flight away. This creates a lingering inner conflict because on both sides of the Namibian tarmac are some of the best sand roads we’ve ever seen. Wiser men would ignore them. But with ESP turned off, it was slide time.

With exactly 13 minutes to spare, the car finally grinds to a halt at the barrier, brakes sizzling, exhaust crackling.

From one moment to the next, Quattro returns with a vengeance, pushing hard to support the struggling, spinning, scraping front wheels. It takes only a couple of corners to find the right rhythm, to make lift-off action bond with turn-in bite, to play the car with steering and throttle, throttle and steering. Drama can multiply in the even lower-grip zone between sand and gravel, where the car’s attitudes, gestures, and stances match a ballet dancer for elegance in motion.

The Lüderitz, Namibia, locals might not yet have fully embraced technology, but the 2019 Audi A7 provides plenty of it.

We leave Lüderitz midafternoon, forking off toward Rosh Pinah then heading for the border at Oranjemund. It’s a shorter yet slower route on twistier roads with older, sun-bleached surfaces. According to the guide book, the border crossing closes at 8 p.m., and there is no listed accommodation this side of South Africa, so time is once more of the essence. We fire up the afterburner, and two hours later, we know for a fact that the A7 55 TFSI tops out at more than 150 mph.

Even through increasingly tight radii, the car keeps carving with poise, prowess, and panache. There is a blind understanding between the steering angles of all four wheels, and the firm ride still shows mercy, holding the line with singing tires. With exactly 13 minutes to spare, the car finally grinds to a halt at the barrier, brakes sizzling, exhaust crackling. Gimme five, mate. And please ignore the sign on the customs building that reads, “From Feb. 1, 2018, this border is open 24/7.”

2019 Audi A7 Sportback Specifications

ON SALE Fall PRICE $70,000 (base) (est) ENGINE 3.0L DOHC 24-valve turbo V-6/340 hp @ 5,000-6,400 rpm,369 lb-ft @ 1,370-4,500 rpm TRANSMISSION 7-speed automatic LAYOUT 4-door, 5-passenger, front-engine, AWD hatchback EPA MILEAGE N/A L x W x H 195.6 x 75.1 x 56.0 in WHEELBASE 115.2 in WEIGHT 4,001 lb from Performance Junk WP Feed 4 https://ift.tt/2kgMski via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

The 2019 Audi A7 Sportback Goes to Lüderitz

LÜDERITZ, Namibia — The sat-nav says arrival time 12:53 a.m. The man from Audi advises us not to drive after dark because of wild animals. The photographer says let’s get on with it. My inner voice tells me to believe in the power of laser headlights and night vision, so let the impala and springbok play hide and seek if they want.

On the two-lane N7 highway between Citrusdal, South Africa, just north of Cape Town, to Vioolsdrif at the Namibian border, progress is a matter of attitude, aspiration, and ambition. In addition to being on high alert for any wildlife lurking in the bush, we’re also busy dodging underpaid and overly keen asphalt jockeys in charge of slowly disintegrating tour buses, mirrorless vans on a clock-beating mission, and grotesquely overloaded semis. But thanks to some 39 assistance systems and a switched-on driver who can’t spare a single digit to toy with the seductive, colorful touchscreens, the new 2019 Audi A7 cuts through it all with relative ease. When we hit Klawer, about a quarter of the way to Vioolsdrif, the estimated arrival time has lowered to 12:11 am. We’re making headway.

Our destination is the port of Lüderitz on the Namibian coast, founded in 1883 by settlers from Berlin, Dresden, and Cologne. The A7 Sportback 55 TFSI we’re in is fitted with every conceivable extra and then some. It even features double-glazed glass, multicolor ambient lighting, and intelligent wipers with washer jets focusing on the dirtiest spots. Back-seat magnates like The Donald would undoubtedly appreciate modern conveniences such as Twitter access and the pay TV module; owner-drivers are more likely to applaud the fully automatic parking assistance system, which takes the sting out of hungry curbs and tight entry and exit spirals.

Despite the puzzling 55 TFSI badge, the A7’s base powerplant remains Audi’s 3.0-liter turbo V-6, which now delivers 340 horsepower. It’s been thoroughly modified, feels livelier, and plays a catchier tune. The seven-speed S tronic automatic transmission is really on its toes in Sport mode. Eco efforts include a start-stop system that calls it a day below 15 mph, an efficiency program that cuts the engine between 30 and 100 mph under trailing throttle, and a green lift-off symbol in the instrument binnacle, which suggests that now is the time to take it easy.

It’s not only the 340 hp that gets things done but also the torque curve, which peaks at 369 lb-ft between 1,370 and 4,500 rpm—it is as flat as Cape Town’s famous Table Mountain. The Audi collects further brownie points for its ability to accelerate to 60 mph in an estimated 5.2 seconds, its brisk downshift action, ambitious redline that touches 7,000 rpm, and its aggressively spaced third through fifth gears.

Praise is also due to the air suspension that leans the car ever so slightly into the random gusts of crosswind.

Bureaucracy thrives at the border crossing that separates South Africa from Namibia. We���re in a hurry, but the squadron of uniformed state servants on both sides of the barbed wire evidently has all the time in the world. For no good reason at all, we waste almost an hour filling out forms, waiting for stamps, paying fees, and having the vehicle searched. As a result, our ETA has dropped back. No way are we giving in. So let’s fill up the Ara Blue-sprayed hatchback-coupe and get back after it. We’re going to need to rely on the technical improvements that set the new A7 apart from its predecessor: its piercing matrix-laser headlamps, recalibrated air suspension, and rear-wheel steering chief among them. Having fiddled with Drive Select for the past six hours, the preferred configuration locks the drivetrain in Dynamic while the algorithms looking after steering and chassis are left alone. Above 75 mph, the road-hugging sports pack lowers the ride height by another quarter inch or so.

The final leg of the night stage to Lüderitz goes down in the logbook as a real challenge and an eerie experience. What looks like London fog is actually a proper sandstorm, whipping tall, thin curtains across the road and drowning tire and engine noise in pelting spells that sound like a million needles pitting the paintwork to the primer. The curvy highway is littered with tumbleweed and occasional waves of rock-solid drift sand. It’s a baptism of fire for the A7’s rear-wheel steering, which enhances stability and maneuverability depending on how fast you’re going. Praise is also due to the air suspension, which leans the car ever so slightly into the random gusts of crosswind. Although the broad light cone cast by the matrix-laser wonderbeams could almost touch the horizon on a clear night, we’re limited to low-beams in this tempest.

Helping the cause is Audi’s latest, more fuel-efficient Quattro system—dubbed Ultra—effectively all-wheel drive on demand. Rear-wheel drive only activates to support takeoff traction, cornering grip, and handling bias. Acting progressively and imperceptibly, it engages and disconnects in milliseconds. For enhanced road holding and curb appeal, our test car was fitted with 20-inch wheels shod with 255/40 tires. In the previous A7, this setup in combination with the sport suspension would have smashed a set of false teeth to pieces. The second-generation model, however, has learned to ride more smoothly. Like every Audi, this one is still not pleased with transverse irritations, but it no longer absolutely hates potholes, manhole covers, and railroad crossings. The steel brakes deserve applause for prompt response and efficient deceleration, but it also earns a few scattered boos for elevated pedal pressure, which increases with every repeat high-speed action and is accompanied by a certain sponginess over the final 100 yards or so before the vehicle comes to a full stop.

“No, we don’t have Wi-Fi. Talk to each other!” This sign put up at Giesela’s breakfast station down by the sea is not only a mocking shot across the bow of the Facebook crowd but also confirms in writing that digitalization has not yet fully arrived in Lüderitz. Almost everything related to electricity does in fact move at a different pace in this part of Africa. Filling up the car takes around 10 minutes, the streetlights flicker at night like back in the postwar days, and paying with a credit card only works when a favorable internet wind blows.

We were constantly on guard for African wildlife hiding in the bush, and the new Audi A7’s laser headlights and night vision helped us keep a better eye out.

Architectural gems like Villa Goerke, which looks like something that was helicoptered out of Bavaria and dropped into the rugged desert, dot the landscape. Built in 1909 during the diamond rush, it is now a national historic monument. Then there’s Shark Island, an area that has become prime residential property but used to be a German labor camp where thousands died in the early 1900s. It is a lasting symbol of the numerous atrocities committed against indigenous peoples by the colonial powers.

The Germans, who had claimed large chunks of Africa in 1884’s Berlin Conference, were running the show here.

So although not all of the wounds from those dark days have fully healed, there is a special spirit that has developed among the locals, known as Buchters (Bucht is the German word for bay), who pride themselves on living life to the fullest. Many of them are trilingual, fluent in Afrikaans, German, and English.

The A7 is linguistically even more talented. It speaks more than 15 languages and understands every spoken and written word, although it needs a stable web connection to shine, which is as rare as an ice-cream vendor in this scorching part of the world. But even without car-to-infrastructure intelligence, real-time traffic information, and super-precise HERE maps, the in-dash mix of touchscreens, displays, and buttons is pure sensory overload—a potpourri of recurrent distraction and stubborn, smeary fingerprints. Make no mistake: This is a great-looking, beautifully made, and emphatically modern cockpit. But like in an Airbus A320, you almost need a co-pilot to make full use of the car’s diverse talents.

A short distance from Lüderitz is the ghost town of Kolmannskuppe, a series of buildings fighting a losing battle against sand and wind and time. Kolmannskuppe was built between 1908 and 1910 next to the country’s first diamond mine, which yielded more than 5 million carats of gemstone before World War I broke out. The Germans, who had claimed large chunks of Africa in 1884’s Berlin Conference, were running the show here and in Lüderitz. And what a show it must have been. The largely intact wood-paneled town hall houses a theater, cinema, library, bowling alley, restaurant, bar, and gymnasium.

Perhaps the biggest frivolity was the stone-walled saltwater swimming pool the size of a football stadium, which still caps the hill like an ancient helipad for the gods. A guide named William takes us through the buildings. “Goods were transported by horses, boats, and eventually by rail,” he says. “Round about that time, the diamond barons brought in the first motor cars. When a Mercedes or Rolls broke down, it was simply put away while a new one was ordered. Wealth was unreal in those days.” After a short 17-year boom, the miners moved on, and Kolmannskuppe was abandoned by 1956.

Today’s travelers on African roads don’t have the luxury of waiting months for a new car to replace the old one, let alone hours to fix more than one flat tire or a mechanical fault that grounds the vehicle in the middle of nowhere. Then there’s the worst-case scenario, getting in a crash, since the next hospital is more than likely a long drive or flight away. This creates a lingering inner conflict because on both sides of the Namibian tarmac are some of the best sand roads we’ve ever seen. Wiser men would ignore them. But with ESP turned off, it was slide time.

With exactly 13 minutes to spare, the car finally grinds to a halt at the barrier, brakes sizzling, exhaust crackling.

From one moment to the next, Quattro returns with a vengeance, pushing hard to support the struggling, spinning, scraping front wheels. It takes only a couple of corners to find the right rhythm, to make lift-off action bond with turn-in bite, to play the car with steering and throttle, throttle and steering. Drama can multiply in the even lower-grip zone between sand and gravel, where the car’s attitudes, gestures, and stances match a ballet dancer for elegance in motion.

The Lüderitz, Namibia, locals might not yet have fully embraced technology, but the 2019 Audi A7 provides plenty of it.

We leave Lüderitz midafternoon, forking off toward Rosh Pinah then heading for the border at Oranjemund. It’s a shorter yet slower route on twistier roads with older, sun-bleached surfaces. According to the guide book, the border crossing closes at 8 p.m., and there is no listed accommodation this side of South Africa, so time is once more of the essence. We fire up the afterburner, and two hours later, we know for a fact that the A7 55 TFSI tops out at more than 150 mph.

Even through increasingly tight radii, the car keeps carving with poise, prowess, and panache. There is a blind understanding between the steering angles of all four wheels, and the firm ride still shows mercy, holding the line with singing tires. With exactly 13 minutes to spare, the car finally grinds to a halt at the barrier, brakes sizzling, exhaust crackling. Gimme five, mate. And please ignore the sign on the customs building that reads, “From Feb. 1, 2018, this border is open 24/7.”

2019 Audi A7 Sportback Specifications

ON SALE Fall PRICE $70,000 (base) (est) ENGINE 3.0L DOHC 24-valve turbo V-6/340 hp @ 5,000-6,400 rpm,369 lb-ft @ 1,370-4,500 rpm TRANSMISSION 7-speed automatic LAYOUT 4-door, 5-passenger, front-engine, AWD hatchback EPA MILEAGE N/A L x W x H 195.6 x 75.1 x 56.0 in WHEELBASE 115.2 in WEIGHT 4,001 lb from Performance Junk Blogger Feed 4 https://ift.tt/2kgMski via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

The 2019 Audi A7 Sportback Goes to Lüderitz

LÜDERITZ, Namibia — The sat-nav says arrival time 12:53 a.m. The man from Audi advises us not to drive after dark because of wild animals. The photographer says let’s get on with it. My inner voice tells me to believe in the power of laser headlights and night vision, so let the impala and springbok play hide and seek if they want.

On the two-lane N7 highway between Citrusdal, South Africa, just north of Cape Town, to Vioolsdrif at the Namibian border, progress is a matter of attitude, aspiration, and ambition. In addition to being on high alert for any wildlife lurking in the bush, we’re also busy dodging underpaid and overly keen asphalt jockeys in charge of slowly disintegrating tour buses, mirrorless vans on a clock-beating mission, and grotesquely overloaded semis. But thanks to some 39 assistance systems and a switched-on driver who can’t spare a single digit to toy with the seductive, colorful touchscreens, the new 2019 Audi A7 cuts through it all with relative ease. When we hit Klawer, about a quarter of the way to Vioolsdrif, the estimated arrival time has lowered to 12:11 am. We’re making headway.

Our destination is the port of Lüderitz on the Namibian coast, founded in 1883 by settlers from Berlin, Dresden, and Cologne. The A7 Sportback 55 TFSI we’re in is fitted with every conceivable extra and then some. It even features double-glazed glass, multicolor ambient lighting, and intelligent wipers with washer jets focusing on the dirtiest spots. Back-seat magnates like The Donald would undoubtedly appreciate modern conveniences such as Twitter access and the pay TV module; owner-drivers are more likely to applaud the fully automatic parking assistance system, which takes the sting out of hungry curbs and tight entry and exit spirals.

Despite the puzzling 55 TFSI badge, the A7’s base powerplant remains Audi’s 3.0-liter turbo V-6, which now delivers 340 horsepower. It’s been thoroughly modified, feels livelier, and plays a catchier tune. The seven-speed S tronic automatic transmission is really on its toes in Sport mode. Eco efforts include a start-stop system that calls it a day below 15 mph, an efficiency program that cuts the engine between 30 and 100 mph under trailing throttle, and a green lift-off symbol in the instrument binnacle, which suggests that now is the time to take it easy.

It’s not only the 340 hp that gets things done but also the torque curve, which peaks at 369 lb-ft between 1,370 and 4,500 rpm—it is as flat as Cape Town’s famous Table Mountain. The Audi collects further brownie points for its ability to accelerate to 60 mph in an estimated 5.2 seconds, its brisk downshift action, ambitious redline that touches 7,000 rpm, and its aggressively spaced third through fifth gears.

Praise is also due to the air suspension that leans the car ever so slightly into the random gusts of crosswind.

Bureaucracy thrives at the border crossing that separates South Africa from Namibia. We���re in a hurry, but the squadron of uniformed state servants on both sides of the barbed wire evidently has all the time in the world. For no good reason at all, we waste almost an hour filling out forms, waiting for stamps, paying fees, and having the vehicle searched. As a result, our ETA has dropped back. No way are we giving in. So let’s fill up the Ara Blue-sprayed hatchback-coupe and get back after it. We’re going to need to rely on the technical improvements that set the new A7 apart from its predecessor: its piercing matrix-laser headlamps, recalibrated air suspension, and rear-wheel steering chief among them. Having fiddled with Drive Select for the past six hours, the preferred configuration locks the drivetrain in Dynamic while the algorithms looking after steering and chassis are left alone. Above 75 mph, the road-hugging sports pack lowers the ride height by another quarter inch or so.

The final leg of the night stage to Lüderitz goes down in the logbook as a real challenge and an eerie experience. What looks like London fog is actually a proper sandstorm, whipping tall, thin curtains across the road and drowning tire and engine noise in pelting spells that sound like a million needles pitting the paintwork to the primer. The curvy highway is littered with tumbleweed and occasional waves of rock-solid drift sand. It’s a baptism of fire for the A7’s rear-wheel steering, which enhances stability and maneuverability depending on how fast you’re going. Praise is also due to the air suspension, which leans the car ever so slightly into the random gusts of crosswind. Although the broad light cone cast by the matrix-laser wonderbeams could almost touch the horizon on a clear night, we’re limited to low-beams in this tempest.

Helping the cause is Audi’s latest, more fuel-efficient Quattro system—dubbed Ultra—effectively all-wheel drive on demand. Rear-wheel drive only activates to support takeoff traction, cornering grip, and handling bias. Acting progressively and imperceptibly, it engages and disconnects in milliseconds. For enhanced road holding and curb appeal, our test car was fitted with 20-inch wheels shod with 255/40 tires. In the previous A7, this setup in combination with the sport suspension would have smashed a set of false teeth to pieces. The second-generation model, however, has learned to ride more smoothly. Like every Audi, this one is still not pleased with transverse irritations, but it no longer absolutely hates potholes, manhole covers, and railroad crossings. The steel brakes deserve applause for prompt response and efficient deceleration, but it also earns a few scattered boos for elevated pedal pressure, which increases with every repeat high-speed action and is accompanied by a certain sponginess over the final 100 yards or so before the vehicle comes to a full stop.

“No, we don’t have Wi-Fi. Talk to each other!” This sign put up at Giesela’s breakfast station down by the sea is not only a mocking shot across the bow of the Facebook crowd but also confirms in writing that digitalization has not yet fully arrived in Lüderitz. Almost everything related to electricity does in fact move at a different pace in this part of Africa. Filling up the car takes around 10 minutes, the streetlights flicker at night like back in the postwar days, and paying with a credit card only works when a favorable internet wind blows.

We were constantly on guard for African wildlife hiding in the bush, and the new Audi A7’s laser headlights and night vision helped us keep a better eye out.

Architectural gems like Villa Goerke, which looks like something that was helicoptered out of Bavaria and dropped into the rugged desert, dot the landscape. Built in 1909 during the diamond rush, it is now a national historic monument. Then there’s Shark Island, an area that has become prime residential property but used to be a German labor camp where thousands died in the early 1900s. It is a lasting symbol of the numerous atrocities committed against indigenous peoples by the colonial powers.

The Germans, who had claimed large chunks of Africa in 1884’s Berlin Conference, were running the show here.

So although not all of the wounds from those dark days have fully healed, there is a special spirit that has developed among the locals, known as Buchters (Bucht is the German word for bay), who pride themselves on living life to the fullest. Many of them are trilingual, fluent in Afrikaans, German, and English.

The A7 is linguistically even more talented. It speaks more than 15 languages and understands every spoken and written word, although it needs a stable web connection to shine, which is as rare as an ice-cream vendor in this scorching part of the world. But even without car-to-infrastructure intelligence, real-time traffic information, and super-precise HERE maps, the in-dash mix of touchscreens, displays, and buttons is pure sensory overload—a potpourri of recurrent distraction and stubborn, smeary fingerprints. Make no mistake: This is a great-looking, beautifully made, and emphatically modern cockpit. But like in an Airbus A320, you almost need a co-pilot to make full use of the car’s diverse talents.

A short distance from Lüderitz is the ghost town of Kolmannskuppe, a series of buildings fighting a losing battle against sand and wind and time. Kolmannskuppe was built between 1908 and 1910 next to the country’s first diamond mine, which yielded more than 5 million carats of gemstone before World War I broke out. The Germans, who had claimed large chunks of Africa in 1884’s Berlin Conference, were running the show here and in Lüderitz. And what a show it must have been. The largely intact wood-paneled town hall houses a theater, cinema, library, bowling alley, restaurant, bar, and gymnasium.

Perhaps the biggest frivolity was the stone-walled saltwater swimming pool the size of a football stadium, which still caps the hill like an ancient helipad for the gods. A guide named William takes us through the buildings. “Goods were transported by horses, boats, and eventually by rail,” he says. “Round about that time, the diamond barons brought in the first motor cars. When a Mercedes or Rolls broke down, it was simply put away while a new one was ordered. Wealth was unreal in those days.” After a short 17-year boom, the miners moved on, and Kolmannskuppe was abandoned by 1956.

Today’s travelers on African roads don’t have the luxury of waiting months for a new car to replace the old one, let alone hours to fix more than one flat tire or a mechanical fault that grounds the vehicle in the middle of nowhere. Then there’s the worst-case scenario, getting in a crash, since the next hospital is more than likely a long drive or flight away. This creates a lingering inner conflict because on both sides of the Namibian tarmac are some of the best sand roads we’ve ever seen. Wiser men would ignore them. But with ESP turned off, it was slide time.

With exactly 13 minutes to spare, the car finally grinds to a halt at the barrier, brakes sizzling, exhaust crackling.

From one moment to the next, Quattro returns with a vengeance, pushing hard to support the struggling, spinning, scraping front wheels. It takes only a couple of corners to find the right rhythm, to make lift-off action bond with turn-in bite, to play the car with steering and throttle, throttle and steering. Drama can multiply in the even lower-grip zone between sand and gravel, where the car’s attitudes, gestures, and stances match a ballet dancer for elegance in motion.

The Lüderitz, Namibia, locals might not yet have fully embraced technology, but the 2019 Audi A7 provides plenty of it.

We leave Lüderitz midafternoon, forking off toward Rosh Pinah then heading for the border at Oranjemund. It’s a shorter yet slower route on twistier roads with older, sun-bleached surfaces. According to the guide book, the border crossing closes at 8 p.m., and there is no listed accommodation this side of South Africa, so time is once more of the essence. We fire up the afterburner, and two hours later, we know for a fact that the A7 55 TFSI tops out at more than 150 mph.

Even through increasingly tight radii, the car keeps carving with poise, prowess, and panache. There is a blind understanding between the steering angles of all four wheels, and the firm ride still shows mercy, holding the line with singing tires. With exactly 13 minutes to spare, the car finally grinds to a halt at the barrier, brakes sizzling, exhaust crackling. Gimme five, mate. And please ignore the sign on the customs building that reads, “From Feb. 1, 2018, this border is open 24/7.”

2019 Audi A7 Sportback Specifications

ON SALE Fall PRICE $70,000 (base) (est) ENGINE 3.0L DOHC 24-valve turbo V-6/340 hp @ 5,000-6,400 rpm,369 lb-ft @ 1,370-4,500 rpm TRANSMISSION 7-speed automatic LAYOUT 4-door, 5-passenger, front-engine, AWD hatchback EPA MILEAGE N/A L x W x H 195.6 x 75.1 x 56.0 in WHEELBASE 115.2 in WEIGHT 4,001 lb from Performance Junk Blogger 6 https://ift.tt/2kgMski via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

CONF: Architecture, Representation, Reproduction (London, 15-16 Jun 17)

The Courtauld Institute of Art, Somerset House, Strand, London, June 15 – 16, 2017

Fantasy in Reality: Architecture, Representation, Reproduction

Thursday 15 June 2017 9:30 am – 6:00 pm with registration from 09.00

Friday 16 June 2017 10:00 am – 5:45 pm with registration from 09.30

Kenneth Clark Lecture Theatre, The Courtauld Institute of Art, Somerset House, Strand, London, WC2R 0RN

Organised by Dr Marie Collier: The Courtauld Institute of Art

From the capriccios of Piranesi and Canaletto to Vladimir Tatlin¹s Monument to the Third International, Archigram¹s drawings in the 1970s, and contemporary video game architecture, architectural fantasies have been produced and reproduced for centuries. On the one hand, architectural fantasies stir the imagination, represent future possibilities, and utopian dreams, on the other, they reflect and reproduce political ideologies, societal aspirations and anxieties. Though by definition, fantasy relates to that outside reality, or beyond possibility, the examples listed above engage directly with reality and they exist as realised projects in the form of architectural representations on paper, as models, as reproductions or as digital files.

This symposium aims to consider the intersection of fantasy and reality by examining a broad range of architectural production from the Renaissance to the present day across different cultures and media. It includes papers that explore the blurred lines, or tensions, between fantasy and reality in architecture and its representation. Architectural fantasies created in drawings, paintings, computer renders, photographs and films, and three dimensional examples in built projects, exhibition pavilions, doll houses, interiors and garden features will be considered as vital forms of architectural production that both reflect and produce reality.

How does the production of architectural fantasies relate to reality and attempt to shape it? How do representations of architecture construct or perpetuate fantasies of the built environment? How have architects, city planners and/or politicians and rulers used architecture to reinforce fantastical notions of reality? What is the role of the mass media in the production and dissemination of architectural fantasies in popular culture?

In what ways do representations of built or soon to be built projects contribute to the construction of fantasy? The conference seeks to address these questions and more.

PROGRAMME

DAY 1 Thursday 15 June 09.00 09.30 REGISTRATION

09.30 09.45 Welcome

09.4511.00 Session 1: Tensions Between Fantasy and Reality Chair: TBC

Amy Butt (Architect and Independent Researcher): Science Fiction Aesthetics: Tensions Between Reality and the Radical

Andrea Canclini (Department of Architecture and Design, Politecnico di Torino): The real construction of a dream, from Celebration to New Urbanism. Determinism in the reproduction of a community in the ethical shapes of urban fantasies

Catherine Bonier (Assistant Professor, Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism, Carleton University): Visionary Digitalia, Filthy Games and Pernicious Beauty

11.00 11.30 TEA /COFFEE BREAK (provided for all, in Seminar room 1)

11.30 12.45 Session 2: Built Architectural Fantasies Chair: TBC

Ashley Paine (ATCH Research Centre, School of Architecture, University of Queensland): Period Rooms and the Fantasy of Architectural Display

Charlotte Ashby (Associate Lecturer, Department of History of Art, Birkbeck, University of London): Fantasy Environments: The Illusion of Nature and Alternative Realities at the Fin-de-siecle

Petra Eckard (Assistant Professor, Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies, Graz University of Technology): A Concrete Fantasy: Edward James¹ Las Pozas

12.45 13.45 LUNCH BREAK (provided for speakers and chairs only)

13.45 15.00 Session 3: Constructing Architectural Fantasies in Mass Media Chair: TBC

Marie Collier (Sackler Research Forum Postdoctoral Fellow, The Courtauld Institute of Art): The New Moscow in Print: Constructing a Fantasy of Socialist Architecture in Soviet Periodicals

Eleanor Rees (PhD Candidate, School of Slavonic Studies, University College London): ŒSpectacles of Socialism¹: The use of the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition in Stalinist Cinema

Reto Geiser (Gus Wortham Assistant Professor, Rice University School of Architecture): From Science Fiction to Science Fact: Chesley Bonestell and the Role of Visual Representation in the Exploration of the Final Frontier

15.00 15.30 TEA /COFFEE BREAK (provided for all, in Seminar room 1)

15.30 16.45 Session 4: Postmodernism and Fantasy Architecture Chair: TBC

Rahma Khazam (Independent Researcher): Postmodernism in Venice: The 1980 Architecture Biennale

Christina Gray (PhD Candidate, Department of Architecture and Urban Design, UCLA): Fantasy in Retail

Kasper Laegring (PhD Candidate, Royal Danish Academy, School of Architecture): Yes is More and the Return of the Postmodernist Imagination

16.45 17.00 REFRESHMENT BREAK

17.00 18.15 Session 5: Imagined Antiquities Chair: TBC

Berthold Hub (Scientific Assistant, Max-Planck Kunsthistorisches Institut Florenz): Filarete¹s ŒFantasie¹: Between Utopia and Reality

Thordoris Koutsogiannis (Chief Curator, Hellenic Parliament Art Collection, Athens): Imaginary Athenian Architecture and the Modern Visual Culture all¹antica

Marco Folin (Associate Professor, University of Genoa) and Monica Preti (Head of Academic Programmes, Auditorium du Musee du Louvre): Maarten van Heemskerck¹s Wonders of the World: Architectural Fantasies in the Northern Renaissance

18.15 RECEPTION

DAY 2 Friday 16 June 09.30 10.00 REGISTRATION

10.00 10.15 Welcome

10.15 11.30 Session 6: Artists as Architects, Architects as Artists Chair: TBC

Anne Schloen (Freelance Curator, Cologne): (im)possible? Artists as Architects Nicholas Bueno de Mesquita (PhD Candidate, The Courtauld Institute of Art): Two and Half Dimension. Russia and Germany and the Formulation of New Architectural Languages 1922-24

Niccola Shearman (PhD Candidate, The Courtauld Institute of Art): Out of the Woods: Lyonel Feininger and the Printed Face of ŒGlasarchitektur¹

11.30 11.45 REFRESHMENT BREAK

11.45 13.00 Session 7: Fantasy Architecture and Models Chair: TBC

Katherine Wheeler (Assistant Professor, University of Miami School of Architecture): A Mini Marchine for Architectural Fantasy

Matthew Wells (PhD Candidate, The Royal College of Art and Victoria & Albert Museum): Use Validity, and Truth: Models between Fantasy and Reality in British Nineteenth-Century Architectural Practice

David Marshall (Associate Professor, School of Culture and Communication, The University of Melbourne): The Chinoiserie Fabrique as Quintessential Fantasy Architecture

13.00 14.00 LUNCH BREAK (provided for speakers and chairs only)

14.00 15.15 Session 8: Promoting Ideology through Architectural Fantasy Chair: TBC

Nicole Rudolph (Associate Professor, Departments of History and Languages, Literature and Cultures, Adelphi University): Fantastic Models and their Discontents: How Spectacular Architecture Shaped Domestic Space Expectations in Postwar France

Steven Rugere (Associate Professor, College of Architecture and Environmental Design Kent State University): Transported without Moving: Two Models of Immersive Fantasy at the 1964 World¹s Fair

Miruna Stroe (Lecturer, Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism): Architectural Representation in Cold War era animation films

15.15 15.45 TEA /COFFEE BREAK (provided for all, in Seminar room 1)

15.45 17.00 Session 9: Architecture, Image, and Fantasy Chair: TBC

Lutz Robers (Lecturer, Jade University Oldenburg): Architecture as/without Image

Edward Denison (Lecturer in Architecture, The Bartlett School of Architecture): Fascist Fantasies: Italian Dreams and African Nightmares

Massimo Mucci (PhD Candidate, University IUAV Venice): Buildable Architecture versus Unbuildable City?: The Case of Lebbeus Woods¹ Drawings

17.00 17.45 Discussion and Concluding Remarks

17.45 END

0 notes

Text

With his sense of scale, respect for existing contexts and an overall sensitivity architect Walter von Lom (*1938) stood out among his contemporaries: its the 1970s and bold architectural statements are still en vogue when the young architect with his first work caused quite a stir in the architectural community. In the inner city of Cologne von Lom filled a gap between two buildings with a very clever apartment building that on the basement level also accommodated his own office, a building that established his reputation as an expert for infill developments. During that very same period Lom also won the competition for the renovation of the historic Marktplatz in Lemgo and received the commission for an addition to the Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum in Kommern as well as the extension and renovation of the St. Marien church in Herten, again projects in which Lom brilliantly worked in existing contexts. In the consecutive four decades until his retirement in 2012 the architect continued to deal with such projects but also added a broad range of typologies to his portfolio, among them single-family and retirment homes, administrative buildings, libraries and museums.

With „Walter von Lom. Einpassung und Eigensinn. Bauten und Entwürfe 1972-2012“, recently published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, Andreas Denk and David Kasparek for the first time provide a complete account of the architect’s oeuvre, comprehensively illustrated and contextualized by means of interviews with the architect and the authors’ texts. By discussing projects, their genesis and their conception in direct exchange with the architect the book receives a very vivid note that makes it exceptionally insightful and diverting: project descriptions, anecdotes and contemporary context alternate with lucidly arranged illustrations and plans and add up to a more than worthy homage to an important protagonist of German postwar modern. Highly recommended!

#walter von lom#architecture book#nachkriegsmoderne#nachkriegsarchitektur#architecture#germany#monograph#book

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

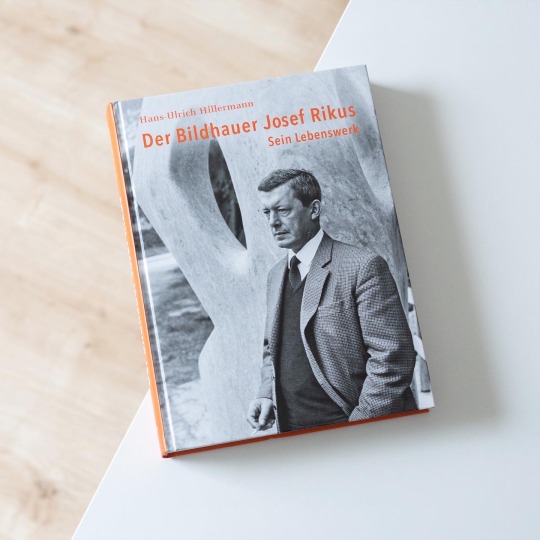

One of the greatest gems of Brutalism in Germany surely is the church Johannes XXIII. in Cologne, a fascinating building oscillating between sculpture and architecture. Although its construction also involved architect Heinz Buchmann it first and foremost is the work of sculptor Heinz Rikus (1923-89) whose sculptures and relief grace(d) the public realm in postwar Germany and the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia in particular.

Rikus, who was born in the city of Paderborn and spent the major part of his life here, already as a schoolboy showed great talent for sculpting and was consecutively promoted by his parents and teachers. After a traumatic war service and severe wounding he used the postwar years for a comprehensive artistic education: after a brief interlude with Eugen Senge-Platten Rikus went to Munich to study with sculptor Karl Knappe. In 1953 he returned to his hometown and quite immediately benefited from both the booming economy and building activity: first memorials were being planned, church facades called for artistic decoration and public authorities revived art in architecture, ideal conditions for a young artist. Although Rikus up until the late 1950s followed in the vein of his mentor Karl Knappe and remained on the relief level in the 1960s he came into his own in three-dimensional sculptures characterized by an increasing degree of abstraction. Especially his works for schools and public spaces ultimately became non-representational constructivist constructions in which Rikus sought to mediate between surrounding architecture and spectator. This notwithstanding Rikus also maintained a figurative strand, strongly influenced by his deep religiousness.

The artist’s centenary provided the ideal background for the small but informative retrospective “Du wirst staunen!” at the Diocesan and Municipal Museum’s in Paderborn which until this Sunday trace Rikus’ religious and public works on the basis of his design models and photographs by his very talented wife. Alongside the exhibitions Hans-Ulrich Hillermann also published the present in-depth work catalogue, highly readable and the first complete account of Josef Rikus’ extensive oeuvre.

#josef rikus#sculptor#art book#art history#nachkriegsmoderne#monograph#art in the public realm#public art

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The former Rotaprint area in Berlin’s wedding district is a rare example of a successful non-commercial development of an entire former industrial property. With its raw-concrete corner tower it also has become an icon of Berlin Brutalism but its architect(s) are a lot lesser-known: Klaus Kirsten (1929-99) and Fritz Nather (*1927), two of Berlin’s most original postwar architects. Their unconventional oeuvre beyond the Rotaprint factory includes a number of single-family homes, commercial and industrial buildings as well as holiday resorts in Italy and Ireland. Both were students of Hans Scharoun but instead of following in his vein of organic architecture they developed a more idiosyncratic idiom that Kirsten infused with his love for Italian architecture.

Their own houses also are the only projects they worked on separately and showcase their respective architectural personalities: while Klaus Kirsten’s house is characterized by a Ponti-esque serenity, Heinz Nather’s house stretches the boundaries of livable openness.

In 2016 Daniela Brahm and Les Schliesser, the initiators of the ExRotaprint project mentioned previously, edited the first comprehensive overview of the architects’ output: „Kirsten & Nather - Wohn- und Fabrikationsgebäude zweier West-Berliner Architekten“, published by Hatje Cantz, is a treasure trove of vintage and contemporary photographs, plans and sections and many anecdotes by Fritz Nather. Along typographies different authors elaborate on Kirsten & Nather’s major projects ranging from their remarkable single-family homes to the different housing units at Neue Stadt in Cologne and of course the Rotaprint area. Interspersed are vintage articles from „Bauwelt“ and „Film und Frau“ that round out this highly readable, storyful reverence to a remarkable architect duo.

#klaus kirsten#heinz nather#monograph#german architecture#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architecture book#book#hatje cantz

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

With about 1.8 million members the Archdiocese of Cologne is the largest in Germany, responsible for 527 individual parishes and countless churches between Cologne, Münster, Essen and Wuppertal. After the End of the Second World War hundreds of chapels and churches lay in ruins, either completely destroyed or severely damaged: actually one third of a total of some 1,100 objects required a completely new construction or a reconstruction amounting to a new construction. Accordingly the first two decades after the end of the war were characterized by an unprecedented amount of building activities to replace destroyed churches or to plan and build new churches for new boroughs.

Some fourty years after publishing its last inventory of newly constructed churches the Cologne Archdiocese with the present two volumes continued a long-standing tradition and accounted for the churches built between 1955 and 1995 in book form: „Neue Kirche im Erzbistum Köln 1955-1995“, edited by Karl Josef Bollenbeck and published by the diocese itself, on some 1,000 pages provides a detailed account of four decades of church architecture in the archdiocese of Cologne. Beyond an outline of the changing paradigms in church architecture by Willy Weyres the volumes above all provide detailed information about each church built under the aegis of the diocese: first a catalogue presents each building in sections, plans and information regarding building costs and client, then a second catalogue shows the churches in contemporary photographs. Based on this comprehensive documentation one can not only discover some lesser-known gems of postwar church architecture but also visually follow the gradual change from mostly longitudinal layouts towards more centralized and pluriform designs.

The present two volumes are real treasure troves, handy in size and studded with insightful information.

#church architecture#religious architecture#architecture book#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#book#architecture#germany

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

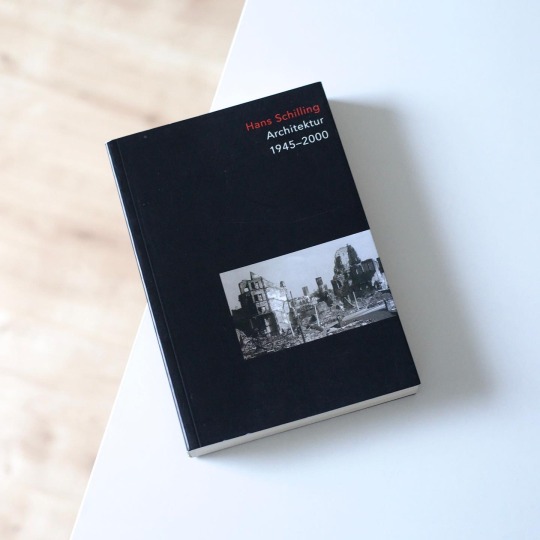

With some 200 individual church designs Hans Schilling (1921-2009) was one of the most productive church architects in postwar Germany. Born and raised in Cologne Schilling spent most of his life in the cathedral city and contributed a number of high profile buildings to the architectural face of it: the church Neu St. Alban, the Maternushaus and the Neumarktpassage are only three examples of Schilling’s extensive architectural work that went well beyond religious architecture. The beginning of his career is closely related to another crucial figure of Cologne’s architecture, namely Karl Band whose office Schilling entered as a draftsman apprentice at the age of 16. After WWII and before going independent in 1955 Schilling soon became Band’s office supervisor and was closely involved in the reconstruction of the Gürzenich alongside his principal and Rudolf Schwarz. With both architects Schilling later shared a decided objectivity and sensibility to context that lended his buildings a great naturalness within the grown context of an old city structure.

In 2001 Schilling published a very personal retrospective of his oeuvre that he explicitly dedicated to his children and grandchildren: simply titled „Hans Schilling. Architektur 1945-2000“ it collects a large number of projects, chronologically structured along typologies and briefly annotated with statements by the architect. Prominently featured are of course his many churches: in this context the previously mentioned Neu St. Alban takes on a key role as it served as model for later churches, a kind of architectural matrix that actually enabled Schilling to design the massive number of churches he ultimately realized. Each typological chapter is introduced by a reflective essay in which the architects reflects on his architectural developments, ideas and difficulties. In this way the book takes on the character of a legacy, honest but also proud of what has been achieved.

#hans schilling#monograph#architecture#germany#nachkriegsmoderne#nachkriegsarchitektur#architecture book#book

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Looking at Paul Schneider-Esleben’s architecture is like looking at the history of postwar architecture in Germany en miniature: PSE, as he was known among colleagues and employees, very attentively followed the developments in architecture and integrated them in his architecture without ever solely using them as superficial effects. At the same time he was a very versatile architect who approached buildings from a holistic perspective that gave several of his buildings the character of a total work of art: furniture and fixtures were designed by PSE himself and even the art on the walls or in front of the building was carefully selected by the architect. The said versatility and attention to detail of Schneider-Esleben’s oeuvre can still be best explored in the present massive monograph he designed together with Heinrich Klotz: „Paul Schneider von Esleben - Entwürfe und Bauten“, published by Hatje Cantz in 1996, a career-spanning overview of the architect’s diverse output. The works and projects covered range from early 1950s houses to early 1990s office buildings, some 40 years of largely remarkable architecture. Between these poles one can follow PSE‘s development along the changing currents of architecture from the delicate transparency of the immediate postwar years over the sculptural brutalism of the 1960s up until his interpretation of postmodernism. What emerges is a very impressive portfolio of large and small projects that includes landmarks of postwar architecture in Germany like the Mannesmann high-rise and Rochus Church in Düsseldorf, the Cologne Bonn Airport or the Sparkasse high-rise in Wuppertal. Each projects is documented in photos, drawings and plans and thus makes a comprehensive analysis easy.

Beyond Schneider-Esleben’s architectural oeuvre the monograph also features several pieces of jewelry he designed for his wife and a selection of the watercolors he painted on his many travels, a little bonus that rounds out the overview of a very creative designer’s life work.

#paul schneider-esleben#monograph#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#architecture book#book#german architecture#hatje cantz

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fritz Schaller (1904-2002) was one of Germany’s most interesting postwar church architects who created spaces of fascinating purity. Emanuel Gebauer’s dissertation „Fritz Schaller: Der Architekt und sein Beitrag zum Sakralbau im 20. Jahrhundert“, published in 2000 by J.P. Bachem Verlag, is an in-depth study of Schaller’s church architecture that goes way beyond the architect’s postwar work: the author also highlights Schaller’s involvement with the Thing movement during the Third Reich, a movement in which actors and amateurs created dramatic plays in dedicated Thing theaters that were often planned by Schaller. Later the movement was forbidden by the Nazi authorities and Schiller found employment at the Heinkel works. After the war Schaller on request of Rudolf Schwarz got involved with the reconstruction of Cologne, a decisive for the success of his Cologne office. At this point Gebauer starts his very detailed analysis of Schaller’s churches and closely recounts the changing circumstances that shaped their designs: from a late 1940s purity to the complexity of the 1960s and 1970s the author, who conducted hours and hours of interviews with the architect, elaborates Schaller’s deep contemplation of each aspect of a church, especially with regards to the different liturgical zones. Accordingly the post-conciliar designs play with the newly found freedom which resulted in complex, multifocal church architectures. A significant project that Gebauer pays particular attention to is Schaller’s transformation of the area surrounding Cologne Cathedral, an extensive project covering both architecture and urbanism that in the meantime has largely been reversed.